MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 41

October 24, 2017

Ruins of Ramses II Temple Unearthed in Giza's Abusir

Ancient Origins

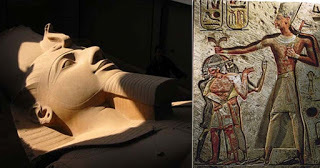

An Egyptian-Czech archaeological mission has unearthed the ruins of a King Ramses II temple during excavation works taking place in the Abusir necropolis in the governorate of Giza. Ramses II was one of the most powerful and celebrated Egyptian kings and was revered as a god in his own lifetime. The absence of evidence of his building in this important area was an anomaly which this discovery now corrects. The archaeologists also uncovered telling reliefs of solar deities.

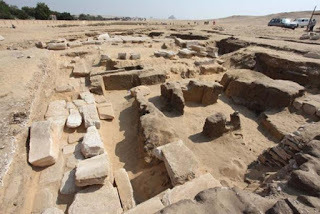

Temple Stretches an Impressive 1768 Square Meters

Deputy Head of the mission, Mohamed Megahed, told Ahram Online that the temple is positioned in an area that forms a natural transition between a terrace of the Nile and the floodplain in Abusir. He also added that the temple stretches over 1768 square meters (18700 sq. ft.) and consists of a mud brick foundation for one of its pylons, a large forecourt that leads to the hypostyle hall, parts of which are painted blue.

View of the entrance pylon of the temple (Image: Czech Institute of Egyptology)

At the rear end of the court, the team of archaeologists discovered a staircase or a ramp to a sanctuary, the back of which is divided into three parallel chambers. The ruins of this building were lying under sand and rubble, which also contain ancient remnants which are of archaeological interest.

“The remains of this building, which constitutes the very core of the complex, were covered with huge deposits of sand and chips of stone of which many bore fragments of polychrome reliefs,” Dr. Mirsolave Barta, director of the Czech mission, told Ahram Online.

View of the excavated temple looking south (Image: Czech Institute of Egyptology)

Temple is the First Evidence of King Ramses II Building in Memphis Necropolis

King Ramses II, (also spelt Ramesses or Rameses and given the title Ramses the Great) had the second longest known reign in Egypt, as the third king of the 19th dynasty of Egypt, 13th century BC). He was well known for extensive building programs but until now this had not been in evidence at the Memphis necropolis where so many other temples are found. Although the presence of Ramses is known here not least from a huge statue that was recovered from the Great Temple of Ptah in 1820 but that long missing evidence of construction has now been found.

Dr. Barta went on to explain that the different titles of King Ramses II were found inscribed on a relief fragment connected to the cult of the solar deities. Furthermore, the head of the Czech mission said that relief fragments portraying scenes of the solar gods Amun, Ra and Nekhbet were also discovered. The find thus verifies the uninterrupted worship of the sun god Ra in the region of Abusir, which began in the 5th dynasty and continued until the era of the New Kingdom. However, the most important thing about this discovery likely remains that this temple is the first evidence so far of King Ramses II’s construction in the Memphis necropolis.

Cartouche of Ramses II, (Image: Czech Institute of Egyptology)

“The discovery of the Ramses II temple provides unique evidence on building and religious activities of the king in Memphis area and at the same time shows the permanent status of the cult of sun god Re who was venerated in Abusir since the 5th Dynasty and onwards to the New Kingdom,” Barta tells Ahram Online.

The Life and Death of Ramses II

As we have previously reported at Ancient Origins, Ramses II is arguably one of the greatest pharaohs of ancient Egypt. Being the third pharaoh of the 19th Dynasty, Ramses II ascended the throne of Egypt during his late teens in 1279 BC following the death of his father – Seti I. He is known to have ruled ancient Egypt for a total of 66 years, outliving many of his sons in the process – although he is believed to have fathered more than 100 children. As a result of his long and prosperous reign, Ramses II was able to undertake numerous military campaigns against neighboring regions, as well as build monuments to the gods, and of course, to himself.

Ramses II colossal statue in the Memphis open air museum in Egypt. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Despite being the one of the most powerful men on earth during his life, Ramses II did not have much control over his physical remains after his death. While his mummified body was originally buried in the tomb KV7 in the Valley of the Kings, looting by grave robbers prompted the Egyptian priests to move his body to a safer resting place. The actions of these priests have rescued the mummy of Ramses II from the looters, only to have it fall into the hands of archaeologists.

In 1881, the mummy of Ramses II, along with those of more than fifty other rulers and nobles were discovered in a secret royal cache at Dier el-Bahri. Ramses II’s mummy was identified based on the hieroglyphics, which detailed the relocation of his mummy by the priests, on the linen covering the body of the pharaoh. About a hundred years after his mummy was discovered, archaeologists noticed the deteriorating condition of Ramses II’s mummy and decided to fly it to Paris to be treated for a fungal infection. Interestingly, the pharaoh was issued an Egyptian passport, in which his occupation was listed as ‘King (deceased)’. Today, the mummy of this great pharaoh rests in the Cairo Museum in Egypt.

Top image: Colossal Statue of Ramses II in Memphis. (CC BY-SA 2.0) Ramses II and his prisoners, Memphis relief (CC BY-SA 4.0)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on October 24, 2017 00:30

October 23, 2017

The Legend of Helen of Troy

Ancient Origins

The mythical Helen of Troy has inspired poets and artists for centuries as the woman whose beauty sparked the Trojan War. But Helen’s character is more complex than it seems. When considering the many Greek and Roman myths that surround Helen, from her childhood to her life after the Trojan War, a layered and fascinating woman emerges.

Helen is among the mythical characters fathered by Zeus. In the form of a swan, Zeus either seduced or assaulted Helen’s mother Leda. On the same night, Leda slept with her husband Tyndareus and as a result gave birth to four children, who hatched from two eggs.

“Leda and the Swan” by Cesare da Sesto, copy of lost painting by Leonardo da Vinci (1515-1520). Image source.

From one egg came the semi-divine children, Helen and Polydeuces (who is called Pollux in Latin), and from the other egg came the mortals Clytemnestra and Castor. The boys, collectively called the Dioscuri, became the divine protectors of sailors at sea, while Helen and Clytemnestra would go on to play important roles in the saga of the Trojan War.

In another, older myth, Helen’s parents were Zeus and Nemesis, the goddess of vengeance. In this version, too, Helen hatched from an egg.

Helen was destined to be the most beautiful woman in the world. Her reputation was so great that even as a young child, the hero Theseus desired her for his bride. He kidnapped her and hid her in his city of Athens, but when he was away, Helen’s brothers, the Dioscuri, rescued her and brought her home.

As an adult, Helen was courted by many suitors, out of whom she chose Menelaus, the king of Sparta. But though Menelaus was valiant and wealthy, Helen’s love for him would prove tenuous.

Around this time there was a great event among the Olympians: the marriage of the goddess Thetis to the mortal Peleus. All the gods were invited to attend except for Eris, whose name means “discord.” Furious at her exclusion, Eris comes to the party anyway and tosses an apple to the goddesses Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite on which is written “for the most beautiful.” Each goddess claims the apple is meant for her and the ensuing dispute threatens the peace of Olympus.

Zeus appoints the Trojan prince Paris to judge who is most beautiful of the three. To sway his vote, each goddess offers Paris a bribe. From Hera, Paris would have royal power, while Athena offers victory in battle. Aphrodite promises him Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world as his wife, and Paris names her winner of the competition.

“The Judgment of Paris” by Peter Paul Reubens (ca. 1638).

Paris contemplates the goddesses while Hermes holds up the apple. Athena is nearest to Hermes with her characteristic weapons by her side, Aphrodite is in the middle with her son Eros hugging her leg, and Hera stands on the far right. Image source.

To claim the prize promised by Aphrodite, Paris travels to the court of Menelaus, where he is honored as guest. Defying the ancient laws of hospitality, Paris seduces Helen and flees with her in his ship.

Roman poet Ovid writes a letter from Helen to Paris, capturing her mix of hesitance and eagerness:

I wish you had come in your swift ship back then, When my virginity was sought by a thousand suitors. If I had seen you, you would have been first of the thousand, My husband will give me pardon for this judgment! (Ovid, Heroides 17.103-6)

“The Abduction of Helen” by Gavin Hamilton (1784). Image source.

Paris sails home to Troy with his new bride, an act which was considered abduction regardless of Helen’s complicity. When Menelaus discovers that Helen is gone, he and his brother Agamemnon lead troops overseas to wage war on Troy.

There is, however, another version of Helen’s journey from Mycenae put forth by the historian Herodotus, the poet Stesichorus, and the playwright Euripides in his play Helen. In this version, a storm forces Paris and Helen to land in Egypt, where the local king removes Helen from her kidnapper and sends Paris back to Troy. In Egypt, Helen is worshipped as the “Foreign Aphrodite.” Meanwhile, at Troy, a phantom image of Helen convinces the Greeks she is there. Eventually, the Greeks win the war and Menelaus arrives in Egypt to reunite with the real Helen and sail home. Herodotus argues that this version of the story is more plausible because if the Trojans had had the real Helen in their city, they would have given her back rather than let so many great soldiers die in battle over her.

Nevertheless, in the most popular version of the story, that of Homer, Helen and Paris return to Troy together. When they arrive, Paris’ first wife, the nymph Oenone, sees them together and laments that he has abandoned her. She grows bitter and even faults Helen for having been kidnapped by Theseus as a child. In heartbroken anger she says:

She who is abducted so often, must offer herself up to be abducted! (Ovid, Heroides V.132)

Paris’ slight against Oenone would prove detrimental for him in the end.

The Greeks sail to Troy and ten years of war commence.

Featured image: Helen of Troy by Evelyn De Morgan (1898, London). Image source.

Primary Sources Euripides Helen; Trojan Women; Orestes Herodotus, The Histories Homer, Iliad; Odyssey Hyginus, Fabulae Lucian, Judgment of Paris Ovid, Heroides V, XVI, XVII Stesichorus, Palinode Vergil, Aeneid By Miriam Kamil

Published on October 23, 2017 00:30

October 22, 2017

6 myths about Richard III

History Extra

Myth 1: Richard was a murderer Shakespeare’s famous play,

Richard III, summarises Richard’s alleged murder victims in the list of ghosts who prevent his sleep on the last night of his life. These comprise Edward of Westminster (putative son of King Henry VI); Henry VI himself; George, Duke of Clarence; Earl Rivers; Richard Grey and Thomas Vaughan; Lord Hastings; the ‘princes in the Tower’; the Duke of Buckingham and Queen Anne Neville.

But Clarence, Rivers, Grey, Vaughan and Buckingham were all executed (a legal process), not murdered: Clarence was executed by Edward IV (probably on the incentive of Elizabeth Woodville). Rivers, Grey and Vaughan were executed by the Earl of Northumberland, and Hastings and Buckingham were executed by Richard III because they had conspired against him. Intriguingly, similar subsequent actions by Henry VII are viewed as a sign of ‘strong kingship’!

There is no evidence that Edward of Westminster, Henry VI, the ‘princes in the Tower’ or Anne Neville were murdered by anyone. Edward of Westminster was killed at the battle of Tewkesbury, and Anne Neville almost certainly died naturally. Also, if Richard III really had been a serious killer in the interests of his own ambitions, why didn’t he kill Lord and Lady Stanley – and John Morton?

Morton had plotted with Lord Hastings in 1483, but while Hastings was executed, Morton was only imprisoned. As for the Stanleys, Lady Stanley was involved in Buckingham's rebellion. And in June 1485, when the invasion of his stepson, Henry Tudor was imminent, Lord Stanley requested leave to retire from court. His loyalty had always been somewhat doubtful. Nevertheless, Richard III simply granted Stanley's request - leading ultimately to the king's own defeat at Bosworth.

Myth 2: Richard was a usurper

The dictionary definition of ‘usurp’ is “to seize and hold (the power and rights of another, for example) by force or without legal authority”. The official website of the British Monarchy states unequivocally (but completely erroneously) that “Richard III usurped the throne from the young Edward V”.

Curiously, the monarchy website does not describe either Henry VII or Edward IV as usurpers, yet both of those kings seized power by force, in battle! On the other hand, Richard III did not seize power. He was offered the crown by the three estates of the realm (the Lords and Commons who had come to London for the opening of a prospective Parliament in 1483) on the basis of evidence presented to them by one of the bishops, to the effect that Edward IV had committed bigamy and that Edward V and his siblings were therefore bastards.

Even if that judgement was incorrect, the fact remains that it was a legal authority that invited a possibly reluctant Richard to assume the role of king. His characterisation as a ‘usurper’ is therefore simply an example of how history is rewritten by the victors (in this case, Henry VII).

Myth 3: Richard aimed to marry his niece It has frequently been claimed (on the basis of reports of a letter, the original of which does not survive), that in 1485 Richard III planned to marry his niece, Elizabeth of York, eldest daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. There is no doubt that rumours to this effect were current in 1485, and we know for certain that Richard was concerned about them. That is not surprising, since his invitation to mount the throne had been based upon the conclusion that all of Edward IV’s children were bastards.

Obviously no logical monarch would have sought to marry a bastard niece. In fact, very clear evidence survives that proves beyond question that Richard did intend to remarry in 1485. However, his chosen bride was the Portuguese princess Joana. What’s more, his diplomats in Portugal were also seeking to arrange a second marriage there – between Richard’s illegitimate niece, Elizabeth, and a minor member of the Portuguese royal family!

Myth 4: Richard slept at the Boar Inn in Leicester In August 1485, prior to the battle of Bosworth, Richard III spent one night in Leicester. About a century later, a myth began to emerge that claimed that on this visit he had slept at a Leicester inn that featured the sign of a boar. This story is still very widely believed today.

However, there is no evidence to even show that such an inn existed in 1485. We know that previously Richard had stayed at the castle on his rare visits to Leicester. The earliest written source for the story of the Boar Inn visit is John Speede [English cartographer and historian, d1629].

Curiously, Speede also produced another myth about Richard III – that his body had been dug up at the time of the Dissolution. Many people in Leicester used to believe Speede’s story about the fate of Richard’s body. However, when the BBC commissioned me to research it in 2004, I concluded that it was false, and I was proved right by the finding of the king’s remains on the Greyfriars site in 2012. The story of staying at the Boar Inn is probably also nothing more than a later invention.

Myth 5: Richard rode a white horse at Bosworth

In his famous play about the king, Shakespeare has Richard III order his attendants to ‘Saddle white Surrey [Syrie] for the field tomorrow’. On this basis it is sometimes stated as fact that Richard rode a white horse at his final battle. But prior to Shakespeare, no one had recorded this, although an earlier 16th-century chronicler, Edward Hall, had said that Richard rode a white horse when he entered Leicester a couple of days earlier.

There is no evidence to prove either point. Nor is there any proof that Richard owned a horse called ‘White Syrie’ or ‘White Surrey’. However, we do know that his stables contained grey horses (horses with a coat of white hair).

Myth 6: Richard attended his last mass at Sutton Cheney Church

It was claimed in the 1920s that early on the morning of 22 August 1485, Richard III made his way from his camp to Sutton Cheney Church in order to attend mass there. No earlier source exists for this unlikely tale, which appears to have been invented in order to provide an ecclesiastical focus for modern commemorations of Richard.

A slightly different version of this story was recently circulated to justify the fact that, prior to reburial, the king’s remains will be taken to Sutton Cheney. It was said it is believed King Richard took his final mass at St James’ church on the eve of the battle.

For a priest to celebrate mass in the evening (at a time when he would have been required to fast from the previous midnight, before taking communion) would have been very unusual! Moreover, documentary evidence shows clearly that Richard’s army at Bosworth was accompanied by his own chaplains, who would normally have celebrated mass for the king in his tent.

John Ashdown-Hill is the author of The Mythology of Richard III (Amberley Publishing, April 2015). To find out more about the author, visit www.johnashdownhill.com.

Published on October 22, 2017 00:30

October 21, 2017

Shakespeare’s best (or worst) villains

History Extra

Tamora – Titus Andronicus

Tamora, Queen of the Goths, is a cruel and brutal central player in Shakespeare’s ultimate revenge tragedy, Titus Andronicus. Her ruthless, bloody-minded scheming leads to a gore-fest worthy of Game of Thrones.

We are introduced to Tamora as a conquered queen, begging the general of Rome, Titus Andronicus, to show her captured sons mercy. When Titus refuses and instead executes her sons he unleashes a maelstrom of vengeance, as Tamora becomes fuelled by the need to wreak revenge on Titus and his family.

Tamora is patient in her quest for vengeance. She secures herself a powerful position by marrying the weak-willed emperor Saturninus, who she manipulates as a political pawn while conducting an illicit relationship with Aaron, her equally scheming lover.

Tamora’s villainy reaches a shocking peak when she orders her two surviving sons to rape and mutilate Titus’s daughter Lavinia, cruelly ignoring the innocent girl’s pleas for mercy and mocking her distress. In one of Shakespeare’s most shocking and disturbing moments, Lavinia emerges with her hands cut off and her tongue removed. In a 2014 production at London’s Globe Theatre the gore was so overwhelming that during the course of the 51-show run 100 audience members reportedly either fainted (including the reviewer from The Independent) or had to leave.

Tamora gets her comeuppance in one of Shakespeare’s most outrageously blood-soaked finales: Titus murders her two sons and serves them to her baked in a pie. After unwittingly eating the pie Tamora is stabbed to death, as the final scene descends into a bloodbath.

Angelo – Measure for Measure

At first glance Angelo appears quite unlike any of Shakespeare’s other villains: a puritanical moral crusader whose righteousness (and name) seems almost otherworldly. He appears immune to sins of the flesh, described in Act I as “a man whose blood/ is very snow-broth; one who never feels/ the wanton stings and motions of the sense.” However, we quickly come to discover that the upright Angelo is not as virtuous as he first seems.

As temporary leader of Vienna, Angelo proves harsh and unforgiving. He takes a malevolent delight in dishing out severe justice, proclaiming in one scene: “hoping you’ll find good cause to whip them all”.

One way in which Angelo asserts his authority is by cracking down on the city’s sexual immorality, sentencing the young Claudio to death for impregnating his lover. But when Claudio’s virtuous sister Isabella comes to beg for mercy for her brother, Angelo’s intense hypocrisy is revealed. Consumed by lust for Isabella he propositions her, claiming he will reprieve Claudio if she agrees – and if not, her brother’s death is guaranteed to be slow and tortuous.

Revelations from Angelo’s past highlight further his cruel nature, as the audience learns that he abandoned his fiancée when her dowry was lost in a shipwreck.

However, Angelo is not entirely incorrigible. He is willing to confess his sins and expresses guilt, stating in Act V, Scene I “I crave death more willingly than mercy”. Furthermore, none of his immoral plans come to fruition; Isabella is not seduced and Claudio is not executed. Despite his corrupt lust and serious hypocrisy, he is one of Shakespeare’s few villains to be granted forgiveness. The Duke of Vienna pardons his crimes and repeals his death sentence, on the condition that he marries the mistress he abandoned.

1603-4 engraving of a scene from Measure For Measure. (Archive photos/ Getty images)

Richard III – Richard III

Despite having little grounding in historical fact, Shakespeare’s depiction of Richard III as a Machiavellian villain who had a physical deformity, lusted after his niece and lost his “kingdom for a horse” has had real sticking power.

A malicious, deceptive and bitter usurper who seizes England’s throne by nefarious means, Shakespeare’s Richard takes delight in his own villainy. He is unabashed in his evil motives, shamelessly proclaiming in his famous “Now is the winter of our discontent” speech: “I am determined to prove a villain”. However, Richard is also an undeniably charming and complex figure who sucks in the audience with his immoral logic and dazzling wordplay.

But Richard’s sins come back to haunt him – quite literally. Shakespeare provides us a long list of Richard’s murder victims, in a roll call of ghosts that visit him on the last night of his life. Edward of Westminster; Henry VI; George, Duke of Clarence; Earl Rivers; Richard Grey; Thomas Vaughan; Lord Hastings; the princes in the Tower; the Duke of Buckingham and Queen Anne Neville are all claimed to have been murdered by the king.

Writing for History Extra, John Ashdown-Hill suggests that Shakespeare’s claims here are both unfair and untrue. He suggests that some of Richard’s alleged victims (Clarence, Rivers, Grey, Vaughan and Buckingham) were legitimately and legally executed, while “there is no evidence that Edward of Westminster, Henry VI, the princes in the Tower or Anne Neville were murdered by anyone”.

Immediately after his visitation by spirits – the evening before his downfall and death – Richard appears to be suddenly struck by doubt. Despite the glee he formerly took in his wrongdoing, he suddenly lacks conviction about his actions: “O no, alas, I rather hate myself/ For hateful deeds committed by myself/ I am a villain”.

Goneril and Regan – King Lear

Described by their own father as “unnatural hags”, Goneril and Regan are two grasping, self-interested and power-hungry daughters of King Lear. Their willingness to betray their father and their honest sister Cordelia causes the collapse of a kingdom and ultimately leads to Lear’s descent into madness.

In the play’s opening scene the elderly Lear declares his intention to step down as king and divide his realm between his three daughters. In response to this, Goneril and Regan cleverly charm their father, hoping to grasp all they can from his inheritance. Falling for their superficial flattery, Lear divides his kingdom between the two of them, disinheriting Cordelia, who claims she cannot express her love for her father in words. This proves to be a fatal mistake, as Goneril and Regan’s feigned loyalty dissolves rapidly and their willingness to betray their father quickly becomes clear.

By Act III the sisters’ ruthless political manoeuvrings have descended into outright violence. Regan and husband, the Duke of Cornwall, torture her father’s supporter Gloucester, plucking out his eyes and turning him out to wander blindly in the wild. Cornwall’s gruesome exclamation of “Out, vile jelly!” as he rips out the old man’s eyes, is one of the play’s most memorable – and horrifying – moments.

Goneril and Regan’s malevolence eventually turns inwards and rips them apart. Fuelled by jealousy at her sister’s supposed relationship with Edmund (another central villain of the play), Goneril poisons Regan and then kills herself.

Lady Macbeth – Macbeth

Lady Macbeth is undoubtedly one of Shakespeare’s most fascinating female characters. Driven towards evil by a deep ambition and a ruthless appetite for power, she uses her sexuality and powers of manipulation to exert a corrosive influence over her husband, Macbeth.

Arguably a more compelling character than her husband, Lady Macbeth is generally viewed as the driving force behind Macbeth’s lust for power. While he is plagued by uncertainty about killing those who stand in his way, his wife is altogether stronger in her immoral convictions. She persuades him to pursue the Scottish throne by violent and deceptive means, telling him to “look like th' innocent flower/ but be the serpent under't”.

Lady Macbeth encourages her husband’s wrongdoing by portraying murder as both the logical and brave course of action, telling him to “Screw your courage to the sticking place/and we’ll not fail”. After Macbeth murders King Duncan (to claim his throne) she reassures him that “what’s done, is done” and cleans up the murder scene when Macbeth is too afraid to do so. At other points in the play Lady Macbeth’s manipulation of her husband descends into outright bullying. In an intriguing reversal of gender roles she dismisses her husband’s anxiety as feminine weakness, mockingly asking “are you a man?” in response to his hesitation.

Like many of Shakespeare’s villains, Lady Macbeth is eventually consumed by her guilty conscience and driven mad by her murderous actions. Plagued by episodes of sleepwalking, she wanders through the castle, unable to rid the image of her bloodstained hands from her mind, muttering: “Out damn’d spot… who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him?” This is our last image of Lady Macbeth – in the play’s final act she becomes disappointingly absent, eventually committing suicide offstage.

Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth, in a 1906 painting by John Singer Sargent. (Print Collector/Getty Images)

Claudius – Hamlet

In the first act of Hamlet, Shakespeare tells his audience “something is rotten in the state of Denmark”. We quickly discover that this is a reference to Denmark’s usurper king – and Hamlet’s uncle – Claudius.

A crafty politician determined to maintain his grasp over his kingdom, Claudius is guilty of the ultimate sin – fratricide. He has secretly murdered his brother, the king (Hamlet’s father), pouring poison into his ear as he slept, in order to claim his throne and steal his wife.

But, like Macbeth and Richard III, Claudius too is plagued by the vengeful ghost of his victim. The spirit of the dead king appears to Hamlet, demanding to be avenged and exposing Claudius as “that incestuous, that adulterate beast/ with witchcraft of his wit, with traitorous gifts...”.

Shakespeare has crafted a particularly intriguing villain in Claudius by giving him a conscience. Unlike Iago, Tamora or Richard III, Claudius takes no pleasure in his wrongdoing. In Act III he expresses his guilt when he confesses his sins in prayer: “O, my offence is rank, it smells to heaven”.

King Claudius ultimately falls victim to his own conniving nature, as his wife, Gertrude (Hamlet’s mother, who many critics suggest Claudius genuinely loves), accidentally drinks from a poisoned chalice Claudius had intended for Hamlet. Claudius, too, meets his bitter end in classic bloody Shakespearean form: Hamlet stabs Claudius with a poisoned sword before forcing him to drink from the poisoned chalice.

Iago – Othello

Many scholars see Iago as the most inherently evil of all Shakespeare’s villains. He spends the course of the play relentlessly plotting Othello’s downfall and his malicious scheming drives the storyline towards its tragic finale.

What proves so compelling about Iago is that his motivations for such insidious and calculated scheming seem unclear – his only desire appears to be Othello’s destruction. He accomplishes this by planting the seed of jealousy in Othello’s mind. He plots to “pour pestilence into his ear” in order to turn him against his wife, Desdemona. Skillfully concealing his nefarious intentions while winning Othello’s trust, Iago constructs a web of lies to make Othello believe in Desdemona’s sexual infidelity.

The consequences of Iago’s insidious influence are devastating. Enraged by jealousy, Othello eventually murders Desdemona and then kills himself. Although Iago’s schemes are eventually revealed and he is sentenced to execution, it is too little, too late, as his plans have already reached their disastrous conclusion.

Shakespeare does provide some reasons for Iago’s actions: that Othello passed him over for a military promotion and may have slept with his wife. However, it is generally agreed that none of these explanations are really fleshed out enough to provide a convincing motive for Iago’s scheming and profound hatred of Othello. Instead, Iago seems to have an intense enjoyment of manipulation and maliciousness for its own sake, perhaps making him the most essentially evil of all Shakespeare’s villains.

Published on October 21, 2017 00:30

October 20, 2017

Icelander Sagas May Have More Truth to Them than You Think

Ancient Origins

Myths and legends – purely the creation of creative and imaginative minds, right? Not necessarily. Numerous stories, sagas, and texts from the ancient past have been proven to hold facts. For example, a 2013 study validates an intriguing idea presented in the Icelander Sagas - Vikings were probably less brutal than many people assume.

From its beginnings in Greece, the word mythos, English ‘myth’, was rooted in truth. In Greek it means ‘word’, ‘tale’, or ‘true narrative.’ The Greek word is also closely tied to myo, which means ‘to teach’, or ‘to initiate into the mysteries’. When Homer composed his works such as The Iliad he had the idea in mind that myth conveys truth.

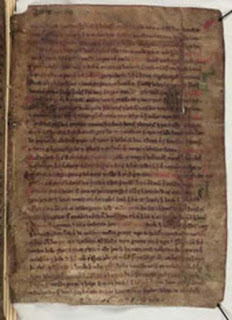

A page from a skin manuscript of Landnámabók, a primary source on the settlement of Iceland.

( Public Domain )

About 400 years later, myths had become known as fiction, superstition, and fantasy. They were considered symbolic, not factual, as the concept of truth was picked apart by science and philosophy.

Nonetheless, the original meaning of the word myth came back again as archaeology and research have proven many legendary stories from the past hold truth at their core. For example, the once legendary city of Troy has been found, and many sea monsters drawn on ancient maps have been identified as real animals, such as giant squid, walruses, and dugongs.

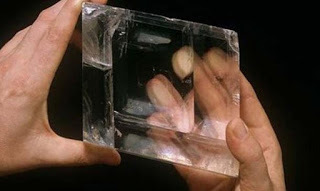

Truth in can be found in the Icelandic Sagas as well. For instance, a so-called ‘magical gem’ known as a Viking Sunstone was once used to navigate the seas. It is spoken of in the sagas and has been proven to be a real crystal made of a calcite substance. This type of stone has been found in a shipwreck. Viking artifacts discovered on an island of Denmark show the legendary city of Lejre, discussed in “myth” actually existed.

A calcite crystal found on an Elizabethan ship believed to have helped the Vikings navigate the seas. Credit: The Natural History Museum

The Icelandic Sagas provide insight on Scandinavian and Germanic history. They discuss early Viking voyages and battles that occurred while at sea, provide information on migration to Iceland, and mention feuds that took place between Iceland’s earliest families.

Norsemen landing in Iceland. ( Public Domain )

These stories were written between 1100 and 1300 AD in the Old Norse language. Most of the tales were written on Iceland, but some refer to the lives of people who lived before 1000 AD. The majority of the stories are written in a realistic way, but some are embellished with fictional elements. Nevertheless, they all deal with human beings in a way you can understand.

Gettir is ready to fight in this illustration from a 17th-century Icelandic manuscript.

( Public Domain )

In 2013, a study published in the European Physical Journal provided a thorough analysis of the relationships discussed in the Icelandic Sagas. It showed a world of complex social networks and challenged the typical view of Vikings as savage people.

By following the interactions of over 1,500 characters that appear in 18 sagas, including five famous epic tales, the researchers from the University of Coventry found that the ‘saga society’ parallels what is found in a real social network. This supports the idea that the Icelandic Sagas were based on reality, though with some fictional distortion at times.

The saga museum contains figures like these which tell the history of early Iceland - the saga age. (Jeffery Simpson/ CC BY NC SA 2.0 )

Top Image: King Haraldr hárfagri receives the kingdom out of his father's hands. From the 14th century Icelandic manuscript Flateyjarbók. Source: Public Domain

By April Holloway

Published on October 20, 2017 00:30

October 19, 2017

Dissolving Myths: Vikings Did NOT Hide Behind Shield Walls

Ancient Origins

By ThorNews

According to Rolf Warming, an archaeologist and researcher at the University of Copenhagen, the Vikings did not use shield walls in combat. A typical Viking shield was relatively small and light, and used as an active weapon.

– There is a widespread misunderstanding among Viking enthusiasts and us archaeologists that the Vikings have been standing shield-by-shield forming a close formation in battle, Warming said to the Danish research portal videnskap.dk.

His research results are supported by archaeological finds, written texts and known Viking fighting techniques that were based on surprise, speed and weapon skills.

Warming, who is also the founder of the Society for Combat Archaeology, has studied how the Vikings fought in battle. He finds no evidence of the use of shield walls in medieval texts or through practical tests.

– The shield wall we see in the popular TV series “Vikings” or “The Last Kingdom” is very nicely made, but unfortunately not true.

Individual Warriors

Among other facts, his theory is based upon an archaeological experiment where Warming equipped with armor, helmet and copies of old Viking shields tested different combat situations against an opponent armed with a sharp sword.

The shield was severely damaged when it was used the same way as in a shield wall, but when Warming used it actively to avoid direct hits from his opponent, the damage was considerably less.

The archaeologist believes that there must have been far more disadvantages than advantages by using shield walls and that the thin and relatively light Viking shields would not have lasted very long.

In addition to the practical tests, the researcher also reviewed a number of historical sources from the Viking Age and the Middle Ages.

He did not find any descriptions of Viking shield walls.

Warming concludes that the Vikings probably fought the enemy actively using their shields, either to avoid being hit by swords or axes, or to hit the enemy with the edge.

Sixty-Four Painted Shields

In 2010, an almost complete hand-held shield was excavated at the Trelleborg Viking ring fortress dated to the reign of Harold Bluetooth of Denmark (c. 958 – 986 AD). So far, this is the only complete shield found in Denmark dating back to the Viking Age.

Fragments from the Trelleborg shield put together. (Photo: National Museum of Denmark)

With a diameter of 85 centimeters, eight millimeters thick near the center and thinning to five millimeters at the edges, the Trelleborg shield was relatively light.

It is made of seven fir planks, has a hole in the middle and a moderately decorated handle. Originally there must have been a boss, but it was never found.

If the Trelleborg shield was typical for the Viking Age, it was originally covered with animal skin to make it stronger, and it was probably painted in bright colors.

In addition to the finding at Trelleborg, there were also found complete shields in the Gokstad ship mound in Norway. The Viking ship was excavated together with a large number of grave goods including sixty-four round shields painted in blue or yellow used as a so-called shield rack to protect the crew against incoming arrows and spears.

Two of the sixty-four shields from the Gokstad ship, thirty-two on each side. Every second was painted in yellow or black and the longship must have been a magnificent sight. (Photo: Museum of Cultural History, Oslo)

The Gokstad shields are like the shield found at Trelleborg - relatively thin - and research has shown that they would easily split when struck with arrows, swords and axes.

This strengthens the theory that they were originally covered with animal skin: The skin shrinks a little when it dries out, something that increases the strength.

By using animal skin, it was also possible to use relatively thin pieces of wood and thereby keep the weight as low as possible.

However, the shields were not strong enough (or big enough) to withstand multiple hits from swords and axes in a shield wall – something that confirms Warming’s theory.

Combat Techniques

It is known that the Vikings used a wide range of combat techniques. One of these is the so-called svinfylking (”Swine Array” or “Boar’s Snout”), a version of the wedge formation used to attack and break through enemy shield walls with an ax as the primary weapon, something that was creating fear and panic.

Svinfylking – sketche

The disadvantage of the svinfylking technique is that it would not work if the attackers had to make a quick retreat.

The Norse sagas also confirm the Viking mentality: Norsemen were fearless warriors who did not hide behind shield walls while they waited for the enemy to attack.

Top image: Illustration of a Viking shield wall (unknown artist)

The article ‘Dissolving Myths: Vikings Did NOT Hide Behind Shield Walls’ by Thor Lanesskog was originally published on ThorNews and has been republished with permission.

Published on October 19, 2017 00:30

October 18, 2017

The Vestal Virgins: Rome’s Most Independent Women

Made from History

Who were the Vestal Virgins and why do we still use the term to define ‘pure’ women or those who are beyond reproach?

Priestesses of Vesta, Goddess of hearth, home and family, the College of Vestal Virgins were Rome’s only full-time priesthood. They numbered only 6 and were selected from noble Roman families at an early age, between 6 and 10 years old. They would tend the sacred fire in the Temple of Vesta and remain virgins for the duration of their tenure, which would stretch long into womanhood, lasting at least 30 years.

A statue at the House of the Vestal Virgins (Atrium Vestae), Upper Via Sacra, Rome. Credit: Carole Raddato (Wikimedia Commons)

The Vestals cared for the Temple and lived behind it in a 3-story house called the Atrium Vestiae, located at the foot of the Palatine Hill.

The Responsibilities and Risks of the College of Vestal Virgins

The Virgins occupied a special place in the official religion of Ancient Rome. Their principal task was to tend to the sacred fire of Vesta and keep it burning. It was believed that the fire protected Rome. They were also responsible for many rituals denied to male priests.

If a Vestal allowed the fire to die out, she was scourged (behind a curtain for modesty). If she violated her vow of celibacy it would be considered incest, as she was a daughter of the state.

The price for violating the vow of celibacy was death. However, since it was forbidden to spill the blood of a Vestal Virgin or to bury anyone in Rome, the offending priestess would be buried alive in a chamber outside the city along with a few days of food and water. This gave the execution the semblance of a voluntary death.

The Sacrifice of the Vestal by Alessandro Marchesini, early 1700s.

The Most Powerful Women in Rome?

Women in Rome, even those of high social rank and significant wealth, enjoyed few rights. Though Roman society was home to some very powerful individual women, they exercised their power through creative ways generally not enshrined by law, for example by influencing powerful men, through seditious conduct or by using extreme wit, intelligence and social skills.

The Vestal Virgins were the exception. They enjoyed a level of privilege, power and independence that was unique among Roman women — and arguably Roman men. These were all based on religious superstitions and the sacred position afforded them by the state.

Rights, Privileges and Powers Enjoyed by the Vestal Virgins:

Emancipatory Powers

If a condemned prisoner happened to see a Vestal Virgin en route to execution, they were immediately pardoned. A Vestal could furthermore free a slave just by touch.

A Vestal’s word was beyond reproach. Her testimony was accepted without the requirement of being under oath.

Privileges

Vestals were given seats of honour at public events, such as games or performances, at which their sacred presence was often required. They were transported to these events in covered carriages accompanied by guards, always given the right of way.

The Roman state entrusted them with important documents, such as public treaties and the wills of powerful citizens.

Rights

The priesthood could own property and make wills, only possible among emancipated women, i.e. those not subject to the power of a man. They were also the only women who could vote.

Protection

The Vestal Virgins were protected by personal escorts and the law. Physically harming one was penalised by death.

Why Do We Still Use the Term ‘Vestal Virgin’?

Peter Paul Rubens’ Mars and Rhea Silvia, c. 1616–1617

The College of the Vestal Virgins existed in the time of both the Republic and Empire, lasting around 1,000 years in total.

The image of the chaste Vestal Virgin has survived long after the fall of Rome, often used as an allegory for chastity and virtue. Famous women have been depicted as Vestals in order to give tribute to or promote an idea of purity, for example, Elizabeth I, the ‘Virgin Queen’.

Later representations of Vestals adopted an erotic tone in the vein of the ‘forbidden fruit’. This theme may in fact go back to the founding myth of Rome, in which the god Mars impregnates a Vestal Virgin, Rhea Silvia. She then gives birth to Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of the city. Roman authors also found titillation in writing stories about the supposed sexual transgressions of Vestal Virgins.

This article uses material from the book Women in Ancient Rome by Paul Chrystal from Amberley Publishing.

Graham Land

Graham is an editor and contributor at Made From History. A London-based writer originally from Washington, DC, he holds a master's degree in Cultural History from Malmö University in Sweden. Graham also contributes environmental news articles to asiancorrespondent.com and latincorrespondent.com.

Published on October 18, 2017 00:30

October 17, 2017

5 Great Female Warriors of the Ancient World

Made from History

Throughout history, most cultures have considered warfare to be the domain of men. It is only quite recently that female soldiers have participated in modern combat on a large scale. The exception is the Soviet Union, which included female battalions and pilots during the First World War and saw hundreds of thousands of women soldiers fight in World War Two.

In the major ancient civilisations, the lives of women were generally restricted to the most traditional roles, with a few notable exceptions. Yet there were some who broke with tradition and even achieved military greatness.

Here are 5 of history’s fiercest warriors who not only had to face their enemies, but also the strict gender roles of their day.

Fu Hao (d. c. 1200 BC)

The tomb of Fu Hao. Credit: Chris Gyford (Wikimedia Commons)

Lady Fu Hao was one of the 60 wives of Emperor Wu Ding of ancient China’s Shang Dynasty. She broke with tradition by serving as both a high priestess and military general. According to inscriptions on oracle bones from the time, Fu Hao led many military campaigns, commanded 13,000 soldiers and was considered the most powerful military leader of her time.

The many weapons found in her tomb support Fu Hao’s status as a great military power. She also controlled her own fiefdom on the outskirts of her husband’s empire. Her tomb was unearthed in 1976 and can be visited by the public.

Artemisia I of Caria (fl. 480 BC)

The Ancient Greek Queen of Halicarnassus, Artemisia ruled during the late 5th century BC. She was an ally to the King of Persia, Xerxes I, and fought for him during the second Persian invasion of Greece, personally commanding 5 ships at the Battle of Salamis.

Herodotus writes that she was a decisive and intelligent, albeit ruthless strategist. According to Polyaenus, Xereses praised Artemisia above all other officers in his fleet and rewarded her for her performance in battle.

Boudica (d. 60/61 AD)

Queen of the British Celtic Icini tribe, Boudica led an uprising against the forces of the Roman Empire in Britain after the Romans ignored her husband Prasutagus’ will, which left rule of his kingdom to both Rome and his daughters. Upon Prasutagus’ death, the Romans seized control, flogged Boudica and had her daughters raped.

Boudica led an army of Icini and Trinovantes, and destroyed Camulodinum (Colchester), Verulamium (St. Albans) and Londinium (London) before finally being defeated by the Romans.

Triệu Thị Trinh (ca. 222 – 248 AD)

Triệu Thị Trinh

Commonly referred to as Lady Triệu, this warrior of 3rd century Vietnam temporarily freed her homeland from Chinese rule. That is according to traditional Vietnamese sources at least, which also state that she 9 feet tall with 3-foot breasts that she tied behind her back during battle. She usually fought while riding an elephant.

Chinese historical sources make no mention of Triệu Thị Trinh, yet for the Vietnamese, Lady Triệu is the most important historical figure of her time.

Zenobia (240 – c. 275 AD)

The Queen of Syria’s Palmyrene Empire from 267 AD, Zenobia conquered Egypt from the Romans only 2 years into her reign. Her empire only lasted a short while longer, however, as the Roman Emperor Aurelian defeated her in 271, taking her back to Rome where she — depending on which account you believe — either died shortly thereafter or married a Roman governor and lived out a life of luxury as a well-known philosopher, socialite and matron.

Dubbed the ‘Warrior Queen’, Zenobia was well educated and multi-lingual. She was known to behave ‘like a man’, riding, drinking and hunting with her officers.

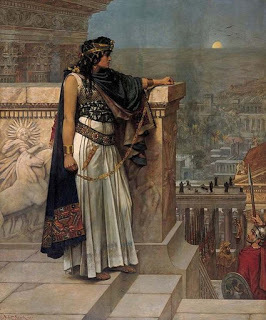

Queen Zenobia’s Last Look Upon Palmyra by Herbert Gustave Schmalz

Graham Land

Graham is an editor and contributor at Made From History. A London-based writer originally from Washington, DC, he holds a master's degree in Cultural History from Malmö University in Sweden. Graham also contributes environmental news articles to asiancorrespondent.com and latincorrespondent.com.

Published on October 17, 2017 00:30

October 16, 2017

Top 5 Dickensian recipes

History Extra

Oxtail stew. (© CICO Books 2017)

The many scenes of eating in the novels of Charles Dickens (1812-1870) are useful ingredients of Victorian social history, particularly his scenes of the young, who are hungry for food and security and are let down by the well-fed adults and, crucially, the institutions who should be caring for them.

Dickens knew the agony of childhood hunger and loneliness. He loved convivial meals and we know his wife Catherine gave a lot of thought to them, because she published a little book of ‘bills of fare’ called What Shall We Have for Dinner? In their London home, she oversaw the cook sweltering over a coal-burning cast-iron range in a cramped basement kitchen, to produce an impressive variety of dishes for a dinner party. To help balance the books, family menus featured economic and filling puddings.

Dickens’ knowledge of domestic details is unusual in a Victorian man: in A Christmas Carol, he knows that Mrs Cratchit, too poor to have an oven, sends her goose to the baker’s and the washing copper doubles up as a pudding pan; in Martin Chuzzlewit he makes a joke about making a beefsteak pudding pastry with butter. This is all part of a picture he loved to paint – a rosy-cheeked young woman learning to cook for her brother or husband.

Victorian food may have a reputation for being either stodgy or unnecessarily fussy, but recreating the dishes that Dickens and his characters tuck into shows that it can be delicious, savoury and warming, light and elegant – and always best shared. Here, author Pen Vogler shares five top Dickensian recipes, updated for modern kitchens…

Charitable soup Catherine Dickens’ menu book is most indebted to the recipes of the celebrity chef Alexis Soyer. In 1847, in the midst of the Irish potato famine, he travelled to Dublin to set up a famine-relief kitchen and wrote Soyer’s Charitable Cookery, the proceeds of which he gave to charity. He later travelled to the Crimea to change the diet of soldiers, particularly those in hospital.

SERVES 6

2 onions, sliced a little olive oil, for frying

2 leeks, sliced and washed free of grit

2 sticks of celery, chopped

2 lb 3 oz/1kg shin of beef or neck of lamb, bone in, cut into pieces by your butcher, plus some stock bones

2 small turnips, chopped bouquet garni or 2 bay leaves and a few sprigs of thyme and curly parsley, tied together

8½ cups/2 litres water (or beef stock if you are using meat without bones)

6 tablespoons pearl barley

3 carrots, chopped salt and freshly ground black pepper

Preheat the oven, if using, to 325°F/165°C/Gas 3.

Sauté the onions in a little olive oil in a skillet/frying pan until they begin to soften, then add the leeks and celery and continue to soften for 5 minutes.

Tip this into a saucepan. Add a little more oil to the pan and brown the meat lightly on all sides in two batches—don’t let it sweat in the pan—then add it to the onions. Add the turnips, herbs, and either stock or cold water plus the stock bones. Season with salt and pepper, bring to a simmer and simmer on a very low heat, or cover and put it in the preheated oven, for 1½ hours.

Add the pearl barley and carrots and continue to simmer for 45 minutes, or until the pearl barley is cooked. Toward the end of the cooking time, take the stock bones and herbs out of the pan and discard.

Take the meat out of the broth, pull it off the bones and shred it, then return the meat to the pan.

Oxtail stew

In The Old Curiosity Shop, Nell, her grandfather, and their eccentric fellow travellers are revived at The Jolly Sandboys with an equally eccentric “stew of tripe… cow-heel… steak… peas, cauliflowers, new potatoes, and sparrow-grass [asparagus] all working up together in one delicious gravy.” Margaret Dods’ dish of oxtail rather than cow-heel, served with peas and root vegetables, is also good for a hungry crowd on a rainy night.

SERVES 4

1 oxtail, about 3¼ lb/1.5kg, cut into short lengths (your butcher will do this for you)

4 slices of unsmoked streaky bacon, chopped olive oil, for frying

2 onions, peeled and roughly chopped

2 garlic cloves, crushed

3 carrots, peeled and roughly chopped 1 small turnip, peeled and roughly chopped a sprig of thyme, a few stalks of parsley, and a bay leaf, tied in a bouquet or in a muslin

1 quart/1 litre organic beef stock salt and freshly ground black pepper sauce hachée or horseradish sauce

For the sauce hachée

2–3 gherkins, finely chopped

1 tablespoon flat-leaf parsley, leaves only, finely chopped salt and freshly ground black pepper Optional extra flavourings for sauce

2 scallions/spring onions, very finely chopped or ½ teaspoon grated horseradish or a little lemon zest

Rinse the oxtail pieces and then leave to soak in salted cold water for an hour or two.

Drain the oxtail, place in a pan of fresh water and bring to a rolling boil for 10–15 minutes, skimming the scum from the surface (this removes the bitterness).

If you are cooking the stew in the oven, preheat it to 300°F/150°C/Gas 2. Fry the bacon in a very little olive oil in a large flameproof pot. Add the onions and garlic and sweat until they begin to soften, then add the rest of the vegetables.

Add the drained oxtail pieces to the pot, fry them a little in the fat until they start to color, then add the herbs, the beef stock, and enough water to make sure the meat is completely covered. Bring to a simmer, check the seasoning, and add a little salt if necessary. Cover and either keep on a very low heat or put in the oven for 4 hours. Add a little water if the oxtail is becoming dry.

When the meat is falling off the bone, take the stew off the heat or remove from the oven. If the gravy is too thin, remove the meat and vegetables with a slotted spoon and boil it fast to reduce it until it is the depth of intensity you like, then add salt and pepper to taste and return the meat and vegetables.

Serve with peas, mashed carrots, and parsnips. For the sauce hachée, simply mix the ingredients and any extra flavouring you select together and serve separately, along with a bowl of horseradish sauce. Or make horseradish mash by infusing warm milk with grated horseradish root while the potatoes are cooking.

Ruth Pinch's beefsteak pudding

Beefsteak pudding. (© CICO Books 2017)

In Martin Chuzzlewit, Ruth Pinch - the sort of ingénue housekeeper that Dickens loved writing about - is worried that the beefsteak pudding she cooks for her brother Tom will “turn out a stew, or a soup, or something of that sort.” Tom enjoys watching her cook, but later teases her when they realize she should have used suet for the pastry. Eliza Acton gives Ruth the last word by devising “Ruth Pinch’s Beefsteak Pudding,” made with butter and eggs.

SERVES 4

For the pastry

3½ cups/450g self-rising flour a pinch of salt

2/3 cup/150g cold butter, cubed, plus extra for greasing

3 eggs

For the filling

1 lb 2 oz/500g stewing steak, cubed 1 onion, finely chopped

2 teaspoons freshly chopped thyme

2 teaspoons freshly chopped parsley

3 level tablespoons all-purpose/plain flour about

2/3 cup/150ml beef stock (or water plus a tablespoon of Worcestershire sauce or mushroom ketchup) salt and freshly ground black pepper

And any of Eliza Acton’s suggested additions:

a few whole oysters or 5½ oz/150g kidney, chopped (Eliza recommended “veal kidneys seasoned with fine herbs”) or

6 oz/170g “nicely prepared button mushrooms”

or a few shavings of fresh truffle

or 5–7 oz/150–200g sweetbreads, chopped

Start by making the pastry. Sieve the flour and salt into a basin; add the butter and rub it in. Beat the eggs together with a dash of cold water, then stir them into the flour mixture with a wooden spoon. Pull the mixture together with your hands, adding a little more water or flour as necessary. When you have an elastic dough, turn it onto a lightly floured board and roll out into a large disc. Cut a quarter out and put to one side.

Fold the two outer quarters over the middle quarter and put into a well-buttered 2-pint/1.2-litre basin, with the point in the bottom. Unfold the two outer quarters and push the pastry into the sides of the basin, wetting the edges so that they seal together and the whole basin is fully lined. Trim the top edge so there is ½–1 inch/1–2cm of pastry overhanging the edge of the basin.

Roll out the remaining quarter to make a circular lid.

Mix the meat with the remaining ingredients except the liquid, making sure the flour is well distributed. Turn it into the pastry-lined basin and pour the stock or liquid over. Brush the top edge of the pastry in the basin with water and put the pastry lid on top, pinching it around to seal.

Put a lid of buttered foil or a circle of parchment or greaseproof paper and a cloth on top, adding a pleat to give room for the pudding to puff up.

Place the basin in a saucepan so that the water comes halfway up the side of the pudding. Cover and steam for up to 4 hours, checking and topping up the water level every half hour or so.

Serve straight from the bowl or turn it out and cut it into segments. The butter crust makes this easier to do than the traditional suet one.

French plums

French plums. (© CICO Books 2017)

The French Plums that Scrooge sees in the greengrocer’s are “blushed in modest tartness from their highly-decorated boxes” (which, if “exceedingly ornamental,” even Mrs. Beeton concedes might be put directly on the dining table). Port and cinnamon turn too-tart plums into a Christmas delight. Candied French plums were Christmas gifts, but should not be confused with “sugar plums,” which are, in fact, sugared nuts or seeds.

Put the water or orange juice, port, sugar, cinnamon stick, and lemon rind in a pan and heat gently until the sugar has dissolved and you have a syrup.

Add the plums, cover, and stew gently for 15 minutes.

Serve with cream, Italian Cream (see page 157), or custard. Alternatively, make into a plum pie by mixing the ingredients together in a pie dish, adding a pastry lid (see pastry recipe on page 129), and baking at 400°F/200°C/Gas 6 for 30–35 minutes.

SERVES 4

3 tablespoons water or juice of

1 orange

3 tablespoons port

1 tablespoon soft brown sugar a cinnamon stick a small piece of orange or lemon rind

approx. 1 lb 2 oz/500g French plums, halved and stones removed

Almond cake for Steerforth

The feast of currant wine, biscuits, fruit, and almond cakes that Steerforth persuades David Copperfield to provide feeds David’s infatuation with the charismatic older boy. A subsequent gift from Peggotty, of cake, oranges, and cowslip wine, he lays at the feet of Steerforth for him to dispense. William Kitchiner’s light almond cake pairs well with oranges, berries, or other fruit.

SERVES 8–10

butter, for greasing

5 free-range eggs

1 cup minus

1 tablespoon/180g golden superfine/caster sugar (or granulated sugar, if you cannot find golden superfine/caster sugar) finely grated zest of 1 lemon or orange

1 teaspoon almond extract (optional)

a pinch of salt

a pinch of cream of tartar

2 cups/200g ground almonds

¼ cup/35g all-purpose/plain flour

For the frosting

1 tablespoon orange or lemon juice

¾ cup/100g confectioners’/icing sugar, sifted

To serve fresh fruit, such as raspberries or cherries, or fruit compôte, such as orange, apricot, or plum

Preheat the oven to 350°F/180°C/Gas 4.

Grease a 9-inch/23-cm bundt pan/tin or ring mold, or a plain springform pan/tin. Separate the eggs and leave the whites to come to room temperature.

Make sure there is no yolk or fat in the whites, which would prevent them from beating properly.

Beat the yolks with ½ cup/100g of the sugar until pale and fluffy, then beat in the lemon or orange zest and the almond extract, if using.

In a completely clean bowl, beat the egg whites until stiff (you should be able to turn the bowl upside down and they won’t fall out!). Add a quarter of the remaining sugar, the pinch of salt, and the cream of tartar, beat again, then fold in the rest of the sugar.

Fold the whites into the batter, a quarter at a time, followed by the almonds and flour. Scrape the mixture into the mold or pan. Bake in the preheated oven for 35–40 minutes until the cake is shrinking from the sides of the pan.

Remove from the oven and leave the cake to cool in the pan for 10 minutes, then turn it out.

To make the frosting, stir the orange or lemon juice into the sifted confectioner's/icing sugar, then drizzle over the cake. Fill the centre of the cake with fresh fruit such as raspberries or cherries.

Alternatively, keep it plain and serve it with a compôte of fruit such as oranges, apricots, or plums.

Almond cake. (© CICO Books 2017)

Compotes of fruit

Eliza Acton recommends a compôte of fruit as a more elegant dessert than the “common ‘stewed fruit’ of English cookery.” The fruit, being added to a syrup, better retains its structure and taste, and the syrup is beautifully translucent. She recommends serving the redcurrant compôtes with the substantial batter, custard, bread, or ground rice puddings Victorians loved.

The preparation is simple. Gently boil white granulated sugar and water together for 10 minutes to make a syrup, skimming any scum from the surface. Add the fruit and simmer until the fruit is lightly cooked. If the syrup is too runny, remove the fruit with a slotted spoon and arrange it in a serving dish. Reduce the syrup over a medium heat, let it cool slightly, and then pour it over. It may also be served cold, and it keeps for a day or two in the fridge. Cinnamon, cloves, vanilla beans/pods, or a little orange or lemon peel can be used as flavourings when you make the syrup.

Eliza Acton recommends the following proportions and timings:

Rhubarb, gooseberries, cherries, damsons - syrup made from ¾ cup/140g sugar with 1¼ cups/280ml water; add 1 lb/450g fruit and simmer for about 10 minutes.

Redcurrants and raspberries - syrup made from ¾ cup/140g sugar with 2/3 cup/140ml water; add 1 lb/450g fruit and simmer for 5–7 minutes.

Mrs. Beeton recommends the following proportions and timings:

Oranges - syrup made from 1½ cups/300g sugar with 21/3 cups/570ml water; add 6 oranges, skin and pith removed, cut into segments. Simmer for 5 minutes. Apples—syrup made from 1 cup plus 2 tablespoons/225g sugar to scant 1¼ cups/280ml water; peel, halve, and core the apples and simmer in the syrup with the juice and rind of a lemon for 15–25 minutes.

Dinner with Dickens: Recipes Inspired by the Life and Work of Charles Dickens by Pen Vogler (CICO Books, £16.99) is on sale now. Pen Vogler is a food historian whose other books include Dinner with Mr Darcy and Tea with Jane Austen.

Published on October 16, 2017 00:00

October 15, 2017

New Release Zane Kindle Edition by K. Meador

Age Level: 4 - 8

Children sometimes need gentle guidance in obedience and lessons in patience. When they can read about families where these lessons are incorporated seamlessly into daily life, it reinforces what they see in their own homes.

Zane aims to provide exactly that example, as Sheila remembers her own experience with disobedience when her son encounters a similar scenario.

Amazon Link

Author K-Trina Meador

I'm just a simple girl who loves simple things: * Enjoying my children * Living in the country * Driving my tractor (farming - my idea of heaven on earth) * Having fun with family and friends * Reading, writing, photography, swimming, bbq and margaritas.

I hope my stories will put a smile upon your face and joy into your hearts.

Published on October 15, 2017 01:00