MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 36

December 13, 2017

Where did King Arthur Acquire Excalibur, the Stone or the Lake?

Ancient Origins

Excalibur is a legendary sword found in Arthurian legends, and is arguably one of the most renowned swords in history. This sword was wielded by the legendary King Arthur, and magical properties were often ascribed to it. In some versions of the story of King Arthur, Excalibur is regarded to be the same sword as the Sword in the Stone. In most versions, however, these are in fact two separate weapons. The fascination with this sword is visible in modern pop culture, as Excalibur can be found in various films, television series and video games.

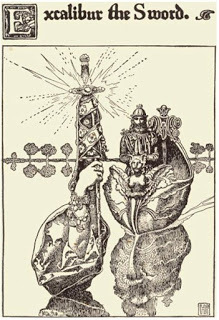

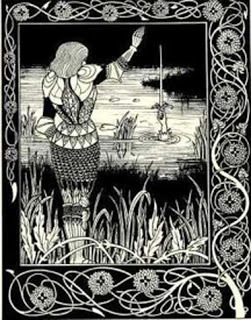

Excalibur the Sword, by Howard Pyle. (Public Domain)

Origins of Excalibur

The story of Excalibur may be traced back to Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain), which was written around 1136. In this piece of work, Excalibur is known by its Latinised name, Caliburnus or Caliburn. Excalibur is described as “an excellent sword made in the isle of Avallon”. It may be pointed out that in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s work, Excalibur does not possess any magical powers. Instead, the author focuses on Arthur’s prowess as a warrior. Thus, for instance, “…

Arthur, provoked to see the little advantage he had yet gained, and that victory still continued in suspense, drew out his Caliburn, and calling upon the name of the blessed Virgin, rushed forward with great fury into the thickest of the enemy’s ranks; … neither did he give over the fury of his assault until he had, with his Caliburn alone, killed four hundred and seventy men.”

Bronze Excalibur and King Arthur Sculpture, Tintagel Castle, Cornwall, UK (Public Domain)

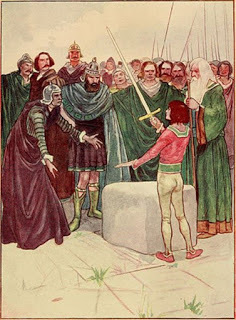

One or Two Swords of the Legends of Arthur

As was stated, it may be noted that Excalibur is sometimes equated with the Sword in the Stone, for example of this is how the story is dealt with in Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d'Arthur, first published in 1485. Other versions of the legend claim that King Arthur obtained this magical sword from another source. In most versions of the story, however, these were two separate weapons. The Sword in the Stone first appears in Robert de Boron’s Merlin, in which Arthur pulls out the sword that was set by the wizard in an anvil (which was changed by later writers into a stone).

‘Then last of all Arthur tried. He took the sword by the hilt and drew it from the stone quite easily’ An island story; a child's history of England (Public Domain)

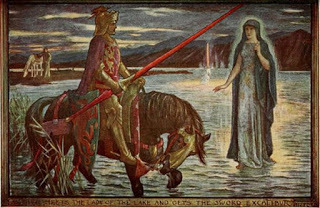

In another version, King Arthur is said to have received Excalibur from the Lady of the Lake. The sword was given to Arthur after he broke his sword during a fight with Pellinore, the king of Listenoise, famous for his hunt of the Questing Beast.

Arthur meets the Lady of the Lake and gets the sword Excalibur. Tales of romance, 1906 (Public Domain)

The Powers of Excalibur

Whilst Geoffrey of Monmouth’s early description of Excalibur is not of a magical sword, later authors decided to make it so. Excalibur’s best known magical property is the ability of its scabbard to heal wounds. This meant that whenever King Arthur had Excalibur’s scabbard with him, he could not be hurt. In the Arthurian legends, this magical scabbard was stolen by the king’s evil half-sister, Morgan le Fay, who then threw it into a lake.

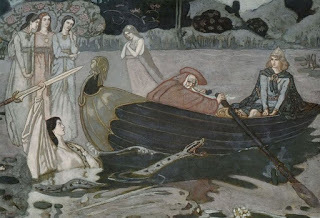

As a result of this, Arthur lost his invulnerability, and was mortally wounded when he fought against Modred (best-known as Arthur’s illegitimate son by another of his half-sisters, Morgaine) at the Battle of Camlann. Before he dies, Arthur commands one of his knights, Sir Bedivere (or Sir Griflet in some versions), to throw Excalibur back into the lake. In one version, the knight disobeyed his sovereign twice by pretending to cast the sword into the lake, as he was not willing to throw away such a precious weapon. When the knight finally throws Excalibur into the lake, a hand reaches out of the water to receive the sword, and pulls it under.

How Sir Bedivere Cast the Sword Excalibur into the Water. Aubrey Beardsley Illustration from: Sir Thomas Malory, Le Morte d'Arthur. London: Dent, 1894 (Public Domain)

Origins of Excalibur

So, where did Arthur acquire the sword Excalibur? Well, the truth is that the story of King Arthur is generally considered as just that, a story, with his actual existence doubtful, so there is no set truth. If you think oldest is best, then the first scribe of the story was Geoffrey of Monmouth in his 12th century version. He wrote of its origins only, ‘Caliburn, [Excalibur] best of swords, that was forged within the Isle of Avallon’ which removes its mystical origin and states clearly where it was made. The first to speak of its origin from a stone is Robert de Boron in his poem Merlin, later in the 12th century, and in both the Vulgate Cycle and Mallory’s version it is made clear the sword in the stone is not Excalibur as it is broken in battle and is replaced by the Excalibur from the lake.

It should be remembered that all of these writers were transcribing stories which originated in the 6th – 8th centuries and had been passed on from oral to written traditions over hundreds of years before the sword and King Arthur were brought together. Although the version by Geoffrey of Monmouth has some basis in historical record, there is also a lot which is not traceable and his account is generally considered more romance than history with the necessary dramatic embellishments.

It seems then, there is no truth readily available. If the real Excalibur did come from the stone, later stories of the magic sword breaking seem incompatible. If the sword from the stone breaking is thought true, the replacement from the lake is needed. Caliburn was forged in Avallon but how it came to Arthur’s hand is not stated. If you want to believe all the legends, the existence of two swords is a requirement.

Quest for Excalibur

As the magical sword of King Arthur, Excalibur has appeared in a number of modern films, television series and video games. Most of the time, there is a quest in which the protagonist of the film / game has to search for the magical sword. This is an indication that Excalibur still fascinates our imagination, and, like the stories of its wielder, King Arthur, will continue to do so well into the future.

Top image: The taking of Excalibur by John Duncan (Public Domain)

By Wu Mingren

Published on December 13, 2017 00:00

December 12, 2017

Wartime Christmas: 5 First World War recipes

History Extra

Christmas was a challenge for the wartime chef on the home front, with food shortages and high prices, even for basic ingredients. So how did Britain feast during the First World War? Hannah Scally, senior historian at illustratedfirstworldwar.com, presents five recipes from the wartime Christmas kitchen

Christmas is today the biggest food event of the year, and things were little different in the 1910s, when abundant courses and elaborate French cuisine were de rigeur. But wartime from 1914 made things tricky, and put a new moral emphasis on economy.

Imports were restricted by naval warfare, and food producers were fighting at the front. Shortages soon appeared, and the Ministry of Food Control was set up in 1916. Initially advocating voluntary rationing, it was forced to introduce compulsory rationing in the last year of the war.

From popular magazine The Bystander, here are some of the Christmas recipes Britain enjoyed during the First World War.

Oyster soufflé

Oysters were eaten in astounding quantities during the 19th century: supplies were bountiful, and they were known as a cheap meat alternative for the poor. They were so popular in fact, that by the end of the 19th century oyster stocks had collapsed, and native oyster beds became exhausted.

By the 20th century oysters had become an expensive delicacy, as this wartime recipe from December 1914 shows. This festive starter, a delicate ‘oyster soufflé’ calls for six oysters:

Put 4 oz. of whiting or sole through a sieve. Make a panada of 1 oz. of butter, 1 oz. of flour, and a quarter of a pint of milk. Stir into this two yolks of eggs and the fish. Beat the whites very lightly, and stir well. Add half a pint of fish stock (made from the bones), one tablespoonful of cream, and six oysters cut up, steam slowly for one and a half hours. Turn over very carefully, pour a rich white sauce round, and decorate the top with a sprinkling of red pepper.

'Panada' was a paste made of flour, breadcrumbs or another starchy ingredient, mixed with liquid.

'White sauce' was defined as a plain sauce based on melted butter, whisked with flour. Milk is slowly added over a low heat until the sauce becomes thick and creamy.

Celery a la Parmesan

This would be a side dish on modern tables, but during the First World War it formed its own course, emulating the French style of table service. Creamy baked celery with a cheesy crust was a rich platter, worthy of the Christmas occasion, and the ingredients were still relatively affordable. This recipe from December 1914 reads:

Stew some celery in milk till tender, then make a white sauce, into which grated Parmesan should be stirred, and then place the celery in the dish it is to be served in. Pour the white sauce over then a layer of grated Parmesan, then a thin layer of breadcrumbs, and over all put pieces of butter, brown in the oven, and serve very hot.

A boned Turkey

This December 1914 recipe is from a special feature in The Bystander, ‘Four methods of cooking a turkey’. Turkey was emerging as a popular Christmas dish, but it did not dominate the Christmas table as it does today. Other fowl – particularly goose – were also popular.

The following recipe is for what was a particularly elaborate dish, recommended for a special public occasion like ‘a ball supper’. While many of The Bystander’s recipes were intended to be practical guides, it seems unlikely that the magazine’s readers would have followed this recipe in large numbers. We can think of this as early food entertainment; the equivalent of watching modern cookery shows. In this case, variety and interesting ideas were just as important as practicality.

Bone a turkey and lay it with the inside uppermost, cut the meat from the thick parts, and distribute it equally all over the inside, season with salt and pepper. Make some forcemeat with veal, ham, and truffles, put a layer of this over the meat of the bird, then a layer of sliced tongue, then another layer of turkey, then forcemeat, then tongue and truffles.

Roll it up, and tie it with tape, and put it in a well-buttered cloth into a stew pan, with two carrots, two onions, a stick of celery, some parsley and peppercorns, and sufficient white stock to cover it. Let it simmer gently for three hours, strain, and let it get cold; remove the cloth, and glaze it all over; if any glaze is left, cut it into various strips and lozenge shapes and garnish the dish with it. This dish is excellent for a ball supper.

'Forcemeat' was a mixture of uncooked ground or pureéd meat, similar to paté, while 'white stock' was a clear meat stock (as opposed to brown stock). The glaze in this instance would be a sweet jelly, brushed over the meat while warm and liquid. When cooled, the jelly would be firm enough to ‘cut into various strips’.

Novel dessert dish

Chestnuts were a traditional Christmas ingredient by December 1915, being grown in abundance on home soil – particularly handy for the wartime cook. But this recipe's dependence on sugar makes it an extravagant dish all the same.

Roast three dozen large chestnuts, peel them, and put them into a stewpan; add 4 oz. of castor sugar and half a gill of water; cook slowly till the nuts absorb the sugar; then pile them up on a glass dish, squeeze over with the juice of a lemon, and dust rather thickly with castor sugar.

A 'gill' was an old unit of measure, equivalent to about 120ml.

Another inexpensive pudding

This recipe, which dates from November 1915, is a classic response to wartime shortages and economy. Unlike some of the exciting recipes above, this is a cheap, practical method for cooking Christmas pudding.

Sugar and eggs were both in increasingly short supply, and this recipe uses only one large spoon of sugar, and no eggs. Instead, the inclusion of a mashed carrot brings some essential sweetness and moisture to the recipe – just like in modern carrot cake.

Although fruit, like everything else during the war, has gone up in price, every English household must have a Christmas Pudding, but today, when eggs are so very expensive, it is necessary to be as careful as possible to try and obtain good results with fewer in the pudding. The secret of success is in the boiling, and the longer a Christmas pudding is allowed to boil the richer it will be.

Six spoonfuls of flour, ½ lb. of beef suet, ½ lb. of currants, one large spoonful of sugar, one large carrot to be boiled and mashed finely and mixed with the above ingredients, and the pudding to be boiled five hours. No milk or eggs are to be used in mixing the pudding. Serve with sweet sauce [almond or brandy sauce – popular accompaniments to Christmas pudding].

A 1915 Yuletide menu

The addition of olives with anchovies, and two extra dessert courses, promised to satisfy the most eager Christmas diner. Here is a typical 1915 festive menu:

Hors-d’oeuvres

Clear Ox-tail Soup

Oyster Souffle

Roast Turkey, Chestnut Stuffing

Boiled Ham

Plum Pudding, Mince Pies

Orange Jelly

Olives with Anchovies

Dessert

Coffee, Liqueurs

Christmas was a challenge for the wartime chef on the home front, with food shortages and high prices, even for basic ingredients. So how did Britain feast during the First World War? Hannah Scally, senior historian at illustratedfirstworldwar.com, presents five recipes from the wartime Christmas kitchen

Christmas is today the biggest food event of the year, and things were little different in the 1910s, when abundant courses and elaborate French cuisine were de rigeur. But wartime from 1914 made things tricky, and put a new moral emphasis on economy.

Imports were restricted by naval warfare, and food producers were fighting at the front. Shortages soon appeared, and the Ministry of Food Control was set up in 1916. Initially advocating voluntary rationing, it was forced to introduce compulsory rationing in the last year of the war.

From popular magazine The Bystander, here are some of the Christmas recipes Britain enjoyed during the First World War.

Oyster soufflé

Oysters were eaten in astounding quantities during the 19th century: supplies were bountiful, and they were known as a cheap meat alternative for the poor. They were so popular in fact, that by the end of the 19th century oyster stocks had collapsed, and native oyster beds became exhausted.

By the 20th century oysters had become an expensive delicacy, as this wartime recipe from December 1914 shows. This festive starter, a delicate ‘oyster soufflé’ calls for six oysters:

Put 4 oz. of whiting or sole through a sieve. Make a panada of 1 oz. of butter, 1 oz. of flour, and a quarter of a pint of milk. Stir into this two yolks of eggs and the fish. Beat the whites very lightly, and stir well. Add half a pint of fish stock (made from the bones), one tablespoonful of cream, and six oysters cut up, steam slowly for one and a half hours. Turn over very carefully, pour a rich white sauce round, and decorate the top with a sprinkling of red pepper.

'Panada' was a paste made of flour, breadcrumbs or another starchy ingredient, mixed with liquid.

'White sauce' was defined as a plain sauce based on melted butter, whisked with flour. Milk is slowly added over a low heat until the sauce becomes thick and creamy.

Celery a la Parmesan

This would be a side dish on modern tables, but during the First World War it formed its own course, emulating the French style of table service. Creamy baked celery with a cheesy crust was a rich platter, worthy of the Christmas occasion, and the ingredients were still relatively affordable. This recipe from December 1914 reads:

Stew some celery in milk till tender, then make a white sauce, into which grated Parmesan should be stirred, and then place the celery in the dish it is to be served in. Pour the white sauce over then a layer of grated Parmesan, then a thin layer of breadcrumbs, and over all put pieces of butter, brown in the oven, and serve very hot.

A boned Turkey

This December 1914 recipe is from a special feature in The Bystander, ‘Four methods of cooking a turkey’. Turkey was emerging as a popular Christmas dish, but it did not dominate the Christmas table as it does today. Other fowl – particularly goose – were also popular.

The following recipe is for what was a particularly elaborate dish, recommended for a special public occasion like ‘a ball supper’. While many of The Bystander’s recipes were intended to be practical guides, it seems unlikely that the magazine’s readers would have followed this recipe in large numbers. We can think of this as early food entertainment; the equivalent of watching modern cookery shows. In this case, variety and interesting ideas were just as important as practicality.

Bone a turkey and lay it with the inside uppermost, cut the meat from the thick parts, and distribute it equally all over the inside, season with salt and pepper. Make some forcemeat with veal, ham, and truffles, put a layer of this over the meat of the bird, then a layer of sliced tongue, then another layer of turkey, then forcemeat, then tongue and truffles.

Roll it up, and tie it with tape, and put it in a well-buttered cloth into a stew pan, with two carrots, two onions, a stick of celery, some parsley and peppercorns, and sufficient white stock to cover it. Let it simmer gently for three hours, strain, and let it get cold; remove the cloth, and glaze it all over; if any glaze is left, cut it into various strips and lozenge shapes and garnish the dish with it. This dish is excellent for a ball supper.

'Forcemeat' was a mixture of uncooked ground or pureéd meat, similar to paté, while 'white stock' was a clear meat stock (as opposed to brown stock). The glaze in this instance would be a sweet jelly, brushed over the meat while warm and liquid. When cooled, the jelly would be firm enough to ‘cut into various strips’.

Novel dessert dish

Chestnuts were a traditional Christmas ingredient by December 1915, being grown in abundance on home soil – particularly handy for the wartime cook. But this recipe's dependence on sugar makes it an extravagant dish all the same.

Roast three dozen large chestnuts, peel them, and put them into a stewpan; add 4 oz. of castor sugar and half a gill of water; cook slowly till the nuts absorb the sugar; then pile them up on a glass dish, squeeze over with the juice of a lemon, and dust rather thickly with castor sugar.

A 'gill' was an old unit of measure, equivalent to about 120ml.

Another inexpensive pudding

This recipe, which dates from November 1915, is a classic response to wartime shortages and economy. Unlike some of the exciting recipes above, this is a cheap, practical method for cooking Christmas pudding.

Sugar and eggs were both in increasingly short supply, and this recipe uses only one large spoon of sugar, and no eggs. Instead, the inclusion of a mashed carrot brings some essential sweetness and moisture to the recipe – just like in modern carrot cake.

Although fruit, like everything else during the war, has gone up in price, every English household must have a Christmas Pudding, but today, when eggs are so very expensive, it is necessary to be as careful as possible to try and obtain good results with fewer in the pudding. The secret of success is in the boiling, and the longer a Christmas pudding is allowed to boil the richer it will be.

Six spoonfuls of flour, ½ lb. of beef suet, ½ lb. of currants, one large spoonful of sugar, one large carrot to be boiled and mashed finely and mixed with the above ingredients, and the pudding to be boiled five hours. No milk or eggs are to be used in mixing the pudding. Serve with sweet sauce [almond or brandy sauce – popular accompaniments to Christmas pudding].

A 1915 Yuletide menu

The addition of olives with anchovies, and two extra dessert courses, promised to satisfy the most eager Christmas diner. Here is a typical 1915 festive menu:

Hors-d’oeuvres

Clear Ox-tail Soup

Oyster Souffle

Roast Turkey, Chestnut Stuffing

Boiled Ham

Plum Pudding, Mince Pies

Orange Jelly

Olives with Anchovies

Dessert

Coffee, Liqueurs

Published on December 12, 2017 00:00

December 11, 2017

First Hard Evidence for Julius Caesar's Invasion of Britain Discovered

Ancient Origins

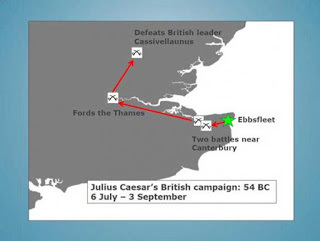

The first evidence for Julius Caesar's invasion of Britain has been discovered by archaeologists from the University of Leicester. Based on new evidence, the team suggests that the first landing of Julius Caesar's fleet in Britain took place in 54BC at Pegwell Bay on the Isle of Thanet, the north-east point of Kent.

Prospective Locations

This location matches Caesar's own account of his landing in 54 BC, with three clues about the topography of the landing site being consistent with him having landed in Pegwell Bay: its visibility from the sea, the existence of a large open bay, and the presence of higher ground nearby.

The project has involved surveys of hillforts that may have been attacked by Caesar, studies in museums of objects that may have been made or buried at the time of the invasions, such as coin hoards, and excavations in Kent.

The University of Leicester project, which is funded by the Leverhulme Trust, was prompted by the discovery of a large defensive ditch in archaeological excavations before a new road was built. The shape of the ditch at Ebbsfleet, a hamlet in Thanet, is very similar to some of the Roman defences at Alésia in France, where the decisive battle in the Gallic War took place in 52 BC.

The site, at Ebbsfleet, on the Isle of Thanet in north-east Kent overlooking Pegwell Bay, is now 900 meters (2950 ft) inland but at the time of Caesar's invasions it was closer to the coast. The ditch is 4-5 meters (13-16.5 ft)( wide and 2 meters (6.5 ft) deep and is dated by pottery and radiocarbon dates to the 1st century BC.

View of the University of Leicester excavations at Ebbsfleet in 2016 showing Pegwell Bay and the cliffs at Ramsgate (Image: University of Leicester )

Ebbsfleet’s Candidacy

The size, shape, date of the defences at Ebbsfleet and the presence of iron weapons including a Roman pilum (javelin) all suggest that the site was once a Roman base of 1st century BC date.

The archaeological team suggest the site may be up to 20 hectares in size and it is thought that the main purpose of the fort was to protect the ships of Caesar's fleet that had been drawn up on to the nearby beach.

Dr Andrew Fitzpatrick, Research Associate from the University of Leicester's School of Archaeology and Ancient History said: "The site at Ebbsfleet lies on a peninsular that projects from the south-eastern tip of the Isle of Thanet. Thanet has never been considered as a possible landing site before because it was separated from the mainland until the Middle Ages.

"However, it is not known how big the Channel that separated it from the mainland (the Wantsum Channel) was. The Wantsum Channel was clearly not a significant barrier to people of Thanet during the Iron Age and it certainly would not have been a major challenge to the engineering capabilities of the Roman army.

Lidar model of topography of Thanet showing Ebbsfleet. (Image: Courtesy of University of Leicester)

Caesar’s Account

Caesar's own account of his landing in 54 BC is consistent with the landing site identified by the team.

Dr Fitzpatrick explained: "Sailing from somewhere between Boulogne and Calais, Caesar says that at sunrise they saw Britain far away on the left hand side. As they set sail opposite the cliffs of Dover, Caesar can only be describing the white chalk cliffs around Ramsgate which were being illuminated by the rising sun.

"Caesar describes how the ships were left at anchor at an even and open shore and how they were damaged by a great storm. This description is consistent with Pegwell Bay, which today is the largest bay on the east Kent coast and is open and flat. The bay is big enough for the whole Roman army to have landed in the single day that Caesar describes. The 800 ships, even if they landed in waves, would still have needed a landing front 1-2 km wide.

Ancient Britons oppose the Roman landings. (Public Domain)

"Caesar also describes how the Britons had assembled to oppose the landing but, taken aback by the size of the fleet, they concealed themselves on the higher ground. This is consistent with the higher ground of the Isle of Thanet around Ramsgate.

"These three clues about the topography of the landing site; the presence of cliffs, the existence of a large open bay, and the presence of higher ground nearby, are consistent with the 54 BC landing having been in Pegwell Bay."

The last full study of Caesar's invasions was published over 100 years ago, in 1907.

Caesar by Clara Grosch (Public Domain)

The Outcome of the Invasion

It has long been believed that because Caesar returned to France the invasions were failures and that because the Romans did not leave a force of occupation the invasions had little or no lasting effects on the peoples of Briton. It has also been believed that because the campaigns were short they will have left few, if any, archaeological remains.

The team challenge this notion by suggesting that in Rome the invasions were seen as a great triumph. The fact that Caesar had crossed the sea and gone beyond the known world caused a sensation. At this time victory was achieved by defeating the enemy in battle, not by occupying their lands.

They also suggest that Caesar's impact in Briton had long-standing effects which were seen almost 100 years later during Claudius's invasion of Briton.

Caesar’s British Campaign 54 BC (Image: University of Leicester)

Professor Colin Haselgrove, the principal investigator for the project from the University of Leicester, explained: "It seems likely that the treaties set up by Caesar formed the basis for alliances between Rome and British royal families. This eventually resulted in the leading rulers of south-east England becoming client kings of Rome. Almost 100 years after Caesar, in AD 43 the emperor Claudius invaded Britain. The conquest of south-east England seems to have been rapid, probably because the kings in this region were already allied to Rome.

"This was the beginning of the permanent Roman occupation of Britain, which included Wales and some of Scotland, and lasted for almost 400 years, suggesting that Claudius later exploited Caesar's legacy."

The Praetorians Relief from the Arch of Claudius, once part of the Arch of Claudius erected in 51 AD to commemorate the conquest of Britain. Louvre Lens, France. (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Isle of Thanet Research

The fieldwork for the project has been carried out by volunteers organised by the Community Archaeologist of Kent County Council who worked in partnership with the University of Leicester. The project was also supported by staff from the University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS).

Principal Archaeological Officer for Kent County Council Simon Mason, who oversaw the original road excavations carried out by Oxford Wessex Archaeology, said: "Many people do not realise just how rich the archaeology of the Isle of Thanet is. Being so close to the continent, Thanet was the gateway to new ideas, people, trade and invasion from earliest times. This has resulted in a vast and unique buried archaeological landscape with many important discoveries being regularly made. The peoples of Thanet were once witness to some of the earliest and most important events in the nation's history: the Claudian invasion to start the period of Roman rule, the arrival of St Augustine's mission to bring Christianity and the arrival of the Saxons celebrated through the tradition of Hengist and Horsa. It has been fantastic to be part of a project that is helping to bring another fantastic chapter, that of Caesar, to Thanet's story."

The findings will be explored further as part of the BBC Four's Digging For Britain, The East episode, in which the Ebbsfleet site appears, will be the second programme in the series, and will be broadcast on Wednesday 29 November 2017, and available on BBC iPlayer.

Top image: Caesar's first invasion of Britain: Caesar's boat is pulled to the shore while his soldiers fight the resisting indigenous warriors. Lithograph by W. Linnell after E. Armitage. (CC BY 4.0)

The article first published as ‘First Evidence for Julius Caesar's Invasion of Britain Discovered’ was originally published on Science Daily.

Source: University of Leicester. "First evidence for Julius Caesar's invasion of Britain discovered." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 28 November 2017. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/11....

Published on December 11, 2017 00:00

December 10, 2017

Ancient British Bake Off? Cauldrons Fit for Feasting Found at Iron Age Settlement

Ancient Origins

The wealth of evidence found suggests there were many mouths being fed at an Iron Age settlement in the UK that looks to have developed into a regional center for ceremonies and feasting.

A Unique and Unprecedented Collection of Iron Age Artifacts

A team of archaeologists from the University of Leicester has announced the discovery of a unique collection of Iron Age metal artifacts found during an excavation at Glenfield Park, Leicestershire. The nationally significant hoard includes one-off finds for the region and reveals previously unknown information about feasting rituals among prehistoric communities.

As EurekAlert reports, the researchers came across a store of valuable and delightful ancient treasures at the site, including eleven complete, or almost complete, Iron Age cauldrons, fine ring-headed dress pins, an abstruse brooch and a cast copper alloy object known as a 'horn-cap', which they speculate was part of an official staff, highlighting the uncommon nature of the metalwork collection.

Iron involuted brooch ULAS. (Image: University of Leicester)

The conglomeration is considered to be exceptional and unequalled, as never before has an archaeological mission uncovered a treasure trove that includes such a great variety of findings in England.

"Glenfield Park is an exceptional archaeological site, with a fantastic array of finds that highlight this as one of the more important discoveries of recent years,”

John Thomas, director of the excavation and Project Officer from the University of Leicester Archaeological Services commented. He added,

“It is the metalwork assemblage that really sets this settlement apart. The quantity and quality of the finds far outshines most of the other contemporary assemblages from the area, and its composition is almost unparalleled.”

Copper alloy horn-cap ULAS. (Image: University of Leicester)

Character of the Site in Constant Progress

The excavation works at Glenfield Park, Leicestershire, were launched back in the winter of 2013, and since then archaeologists have found enough evidence to believe that the area was inhabited throughout most of the Iron Age and Roman periods. The remains of the settlement consist of several roundhouses, enclosures, 4-post structures and pits that occupied the southern slopes of a low spur of slightly higher ground at the northern end of the development area.

“Early occupation of the site during the earlier middle Iron Age (5th - 4th centuries BC) was relatively modest, consisting of a small open settlement that occupied the south-facing, lower slopes of the spur. Slightly later in the middle Iron Age, indicated to be in the 4th or 3rd centuries BC by radiocarbon dating, the settlement underwent striking changes in character. Individual roundhouses were now enclosed, there was far more evidence for material culture, and rituals associated with the settlement involved apparently deliberate burial of a striking assemblage of metalwork,” Thomas stated in a University of Leicester report.

The interior of one of the Iron Age cauldrons (Image: University of Leicester)

Cauldrons Indicate that the Settlement Was Used as a Host Site for Feasting

Of course, archaeologists were flabbergasted by the many cauldrons found at the site, which, according to the experts, emphasize the important role of the settlement as a possible host site for feasting, with associated traditions of ritual deposition of significant artifacts. “The cauldron assemblage in particular makes this a nationally important discovery. They represent the most northerly discovery of such objects on mainland Britain and the only find of this type of cauldron in the East Midlands,” an impressed Thomas said.

The cauldron enclosure where found to be deliberately buried. (Image: University of Leicester)

The majority of the cauldrons seem to have been purposely positioned in a vast circular enclosure ditch that surrounded a building. They had been laid in either upright or upside down positions, before the ditch was filled in, a fact that indicates that they were buried to commemorate the termination of activities associated with this part of the site. Other cauldrons were discovered buried across the site, indicating that important events were being marked over a long period of time as the settlement developed. "Due to their large capacity it is thought that Iron Age cauldrons were reserved for special occasions and would have been important social objects, forming the centerpiece of major feasts, perhaps in association with large gatherings and events,” Thomas explains as EurekAlert reports.

The cauldrons are made from several separate parts, comprising iron rims and upper bands, hemispherical copper alloy bowls and two iron ring handles attached to the upper band.

They appear to have been a variety of sizes, with rims ranging between 36cm (14.1 inch) and 56cm (22 inch) in diameter, with the total capacity of all cauldrons being approximately 550 liters, which illustrates their potential to provide for large groups of people that may have gathered at the settlement from the wider Iron Age community of the area.

Iron bands were attached to some of the cauldrons. (Image: University of Leicester)

CT Scanning of the Cauldrons Provides Valuable Information

Soon after the important discovery took place, the extremely fragile cauldrons were lifted very carefully from the site in soil blocks for transportation in order to be examined. After an initial analysis by Dr. Andrew Gogbashian, Consultant Radiologist at Paul Strickland Scanner Centre, scientists could finally estimate the original dimensions and profiles of the cauldrons, as well as figure out how they were created. Most importantly, the scans unlocked extraordinarily rare evidence of the beautiful decoration from the period, further complimenting the immense cultural and historical significance of the site.

Color rendered image of a cauldron showing possible decoration on top right of the iron band. (Image: University of Leicester)

Archaeologists noted that with the help of modern technology, they were able to recreate digitally an example of a complete cauldron, which has raised stem and leaf motifs on the vessels iron band, similar to the handle locations, which are similar to the so-called “Vegetal Style” of Celtic art (4th century BC). Ultimately, they mentioned that more detail and information from the cauldrons will only be possible through excavation and conservation, which is being undertaken by MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology).

An optimistic Liz Barham, Senior Conservator at MOLA, told EurekAlert, "Already we have been able to uncover glimpses of the detailed histories of these cauldrons through CT scanning, including evidence of their manufacture and repair, and have identified sooty residues still clinging to the base of one of the cauldrons from the last time it was suspended over a fire. During the upcoming conservation we hope to discover much more about the entire assemblage. If we're lucky, we may even find food residues from the last time they were used - over 2000 years ago." The results of the project to date are published in the current issue of British Archaeology magazine, which will be available from 6 December.

Top image: L-R: An iron cauldron that was found at the site. (Images: University of Leicester)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on December 10, 2017 00:00

December 9, 2017

How jousting made a man of Henry VIII

History Extra

How jousting made a man of Henry VIII Research suggests Henry VIII was angry, impulsive and even rendered impotent by a brain injury suffered while jousting. Here, Emma Levitt explores Henry's love of jousting and reveals how, denied the opportunity to prove his worth on the battlefield, Henry VIII chose to display his masculinity in the tiltyard, bedecked in shining armour and with lance in hand...

“The king hath promised never to joust again except it be with as good a man as himself.” So stated an angry Henry VIII on 20 May 1516, following a tournament held in honour of his sister Margaret, Queen of Scots. Jousting was the king’s favourite sport, but the day had proved disastrous. As always, Henry was captain of the Challengers, the team comprising the jousting elite of the Tudor court: Sir Nicholas Carew; Henry Bourchier, Earl of Essex; and Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk.

The opposing team, the Answerers, consisted of a dozen other jousting enthusiasts from court. They waited in the lists (the barriers that defined the edge of the tournament ground) to answer the challenges given by Henry and his three dashing knights.

Henry was a highly skilled jouster. But what should have been a well-fought and exciting series of duels turned into a succession of bad runs and complete misses, making for a disappointing display. The king, the ultimate showman, was not impressed by the performances of certain knights in the Answerers. Henry blamed them for limiting his final score, arguing that they had failed to keep their horses close enough to the barrier for him to make contact and score points.

The king made it clear that, from then on, it was essential he should compete only against skilled jousters. That way, if he won, the victory would confirm that he was the best jouster – and, by extension, the best man – at court. But Henry hated winning too easily. Each challenge was to be a hard-won battle. It was vital to his manly reputation that competitors did not let him triumph simply because he was king.

To Henry VIII, the joust was more than just a sport – it was a vital part of his kingship. And he modelled this kingship on a particular version of chivalrous masculinity inspired by the archetypal medieval knight bedecked in shining armour, charging down the tiltyard with lance ready to strike his opponent.

For Henry, knighthood was not just an ideal but an active ideology; to his mind, it was essential that 16th-century men still demonstrated such proficiency in arms. He longed to showcase this prowess in battle, to be acknowledged as a warrior king, like Henry V, and started making plans to go to war with France after his accession to the throne in 1509. But his ambition to have his own Agincourt was not to be realised. So, for most of his reign, the tournament was not just a training ground for warfare but also the means by which Henry and his nobles could showcase their warrior skills and chivalrous accomplishments.

Despite improvements, jousting remained a dangerous sport, which is why kings usually refrained from participating. Yet for Henry and men such as Charles Brandon it provided the perfect platform for shows of prowess – and manliness – in front of a great audience.

Charles Brandon’s jousting skills helped propel him up the social ladder. (© Bridgeman)

Keeping score

For all their testosterone-fuelled swagger, the jousters’ conduct was governed by a concise and coherent set of rules that informed a sophisticated scoring system. A ‘king of arms’ marked each contestant’s score in strokes on a scoring tablet known as a cheque. The scoreboard sported three horizontal lines showing the number of courses run. Attaints (hits) were noted on the top line, often differentiated as blows to the body or head. The middle line tallied the number of lances broken, and the bottom line recorded faults.

When Henry VIII was searching for a man “as good as himself”, he needed to look no further than Charles Brandon. The product of a modest gentry background, Brandon attained the highest social status, becoming Duke of Suffolk in 1514 and marrying Henry VIII’s sister Mary Tudor in 1515 – an almost unprecedented ascent up the social ladder.

When I studied the score cheques for Henry VIII’s reign in detail, the reason for Brandon’s meteoric rise soon became obvious: his brilliance as a jouster. Brandon was the perfect companion for Henry, whom he resembled in both looks and build, and regularly jousted alongside the king in a team of two Challengers against all the Answerers.

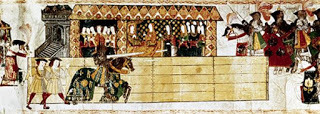

A tournament cheque from Henry VIII’s reign shows, in the left column, the points scored by the Challengers – the team comprising the king, the Duke of Suffolk (Charles Brandon), the Earl of Essex and Sir Nicholas Carew. Their opponents’ tallies are shown in the right-hand column. (© College of Arms MS Tournament Cheque 1c. Reproduced by permission of the Kings, Heralds and Pursuivants of Arms)

In the 1516 tournament Brandon was on Henry’s side, so would not have competed against the king. The cheque reveals that, unlike Henry, Brandon was on top form, losing not a single duel and achieving the highest overall score of all four Challengers. On the second day of the tournament, Brandon broke 17 lances compared with Henry’s 12.

So Henry decided that Brandon would henceforth joust directly against him, leading the Answerers. In this way, at least one of Henry’s duels promised to be a valiant martial display. When the two were matched against each other, one observer compared their fight to that between Hector and Achilles.

This new arrangement created a win-win situation for the king. Not only would Brandon joust against all Henry’s Challengers and beat them, he would then do his duty to the crown and let the king beat him. In this way, Henry would effectively triumph – but it was Brandon who would do all the hard work.

The cheques help explain how a non-noble man not born for high office could achieve high status. Charles Brandon proved time and again to Henry that he was indeed a man “as good as himself”.

Pageantry with a punch

How the Tudor joust worked

Jousting dominated the cultural environment of court during the first half of Henry VIII’s reign. Like modern sports events, tournaments attracted competitors and spectators from afar.

The joust was fought between two knights riding from opposite ends of the lists to encounter each other with lances.

The Challengers was a small team of knights who would challenge all competitors. The opposing team, known as the Answerers, comprised knights who answered the challenge. The Challengers often displayed their shields on a tree known as the ‘Tree of Chivalry’ or ‘Tree of Honour’. Each Answerer would respond, indicating the knight against whom he wished to compete, by hitting the shield of his chosen Challenger.

By the reign of Henry VIII, the joust had become a more formalised competition. A number of rules were introduced, as well as score cheques; prizes were awarded by the queen, and her ladies might add a gold crown, a gold clasp, a diamond ring or even a falcon.

Cheques showed the scores of the competing knights. Points were awarded for unhorsing a knight, breaking two spears tip to tip, striking an opponent’s helmet and breaking the most spears.

Yet there was a lot more to the joust than fighting. By the time of Henry VIII’s reign, it had become a lavish spectacle, with knights entering the lists in fanciful disguises and pageant cars before performing heroic speeches.

Emma Levitt is a PhD student at the University of Huddersfield, working on court culture in the reigns of Edward IV and Henry VIII.

Published on December 09, 2017 00:00

December 8, 2017

What Exactly is the Holy Grail – And Why Has its Meaning Eluded us for Centuries?

Ancient Origins

Leah Tether / The Conversation

Leah Tether works at the University of Bristol. She received funding for this research from Anglia Ruskin University, Ghent University, Somerville College, Oxford and the Stationers' Foundation.

Type “Holy Grail” into Google and … well, you probably don’t need me to finish that sentence. The sheer multiplicity of what any search engine throws up demonstrates that there is no clear consensus as to what the Grail is or was. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t plenty of people out there claiming to know its history, true meaning and even where to find it.

Modern authors, perhaps most (in)famously Dan Brown , offer new interpretations and, even when these are clearly and explicitly rooted in little more than imaginative fiction, they get picked up and bandied about as if a new scientific and irrefutable truth has been discovered. The Grail, though, will perhaps always eschew definition. But why?

The Damsel of the Sanct Grael’ (1874) Dante Gabriel Rossetti. ( Public Domain )

The first known mention of a Grail (“un graal”) is made in a narrative spun by a 12th century writer of French romance, Chrétien de Troyes, who might reasonably be referred to as the Dan Brown of his day – though some scholars would argue that the quality of Chrétien’s writing far exceeds anything Brown has so far produced.

Chrétien’s Grail is mystical indeed – it is a dish, big and wide enough to take a salmon, that seems capable to delivering food and sustenance. To obtain the Grail requires asking a particular question at the Grail Castle. Unfortunately, the exact question (“Whom does the Grail serve?”) is only revealed after the Grail quester, the hapless Perceval, has missed the opportunity to ask it. It seems he is not quite ready, not quite mature enough, for the Grail.

The Holy Grail depicted as a dish in which Christ’s blood is collected. ( British Library )

But if this dish is the “first” Grail, then why do we now have so many possible Grails? Indeed, it is, at turns, depicted as the chalice of the Last Supper or of the Crucifixion or both, or as a stone containing the elixir of life , or even as the bloodline of Christ . And this list is hardly exhaustive. The reason most likely has to do with the fact that Chrétien appears to have died before completing his story, leaving the crucial questions as to what the Grail is and means tantalisingly unanswered. And it did not take long for others to try to answer them for him.

Robert de Boron, a poet writing within 20 or so years of Chrétien (circa 1190-1200), seems to have been the first to have associated the Grail with the cup of the Last Supper. In Robert’s prehistory of the object, Joseph of Arimathea took the Grail to the Crucifixion and used it to catch Christ’s blood. In the years that followed (1200-1230), anonymous writers of prose romances fixated upon the Last Supper’s Holy Chalice and made the Grail the subject of a quest by various knights of King Arthur’s court. In Germany, by contrast, the knight and poet Wolfram von Eschenbach reimagined the Grail as “Lapsit exillis” – an item more commonly referred to these days as the “Philosopher’s Stone”.

The Holy Grail depicted as a ciborium. ( British Library )

None of these is anything like Chrétien’s Grail, of course, so we can fairly ask: did medieval audiences have any more of a clue about the nature of the Holy Grail than we do today?

Publishing the Grail

My recent book delves into the medieval publishing history of the French romances that contain references to the Grail legend, asking questions about the narratives’ compilation into manuscript books. Sometimes, a given text will be bound alongside other types of texts, some of which seemingly have nothing to do with the Grail whatsoever. So, what sorts of texts do we find accompanying Grail narratives in medieval books? Can this tell us anything about what medieval audiences knew or understood of the Grail?

Sangreal. ( Arthur Rackham )

The picture is varied, but a broad chronological trend is possible to spot. Some of the few earliest manuscript books we still have see Grail narratives compiled alone, but a pattern quickly appears for including them into collected volumes. In these cases, Grail narratives can be found alongside historical, religious or other narrative (or fictional) texts. A picture emerges, therefore, of a Grail just as lacking in clear definition as that of today.

Perhaps the Grail served as a useful tool that could be deployed in all manner of contexts to help communicate the required message, whatever that message may have been. We still see this today, of course, such as when we use the phrase “The Holy Grail of…” to describe the practically unobtainable, but highly desirable prize in just about any area you can think of. There is even a guitar effect-pedal named “holy grail”.

Once the prose romances of the 13th century started to appear, though, the Grail took on a proper life of its own. Like a modern soap opera, these romances comprised vast reams of narrative threads, riddled with independent episodes and inconsistencies. They occupied entire books, often enormous and lavishly illustrated, and today these offer evidence that literature about the Grail evaded straightforward understanding and needed to be set apart – physically and figuratively. In other words, Grail literature had a distinctive quality – it was, as we might call it today, a genre in its own right.

In the absence of clear definition, it is human nature to impose meaning. This is what happens with the Grail today and, according to the evidence of medieval book compilation, it is almost certainly what happened in the Middle Ages, too. Just as modern guitarists use their “holy grail” to experiment with all kinds of sounds, so medieval writers and publishers of romance used the Grail as an adaptable and creative instrument for conveying a particular message to their audience, the nature of which could be very different from one book to the next.

Whether the audience always understood that message, of course, is another matter entirely.

Artist’s interpretation of the holy grail. ( CC BY 2.0 )

Top Image: The Achievement of the Grail. Source: Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

The article‘ What exactly is the Holy Grail – and why has its meaning eluded us for centuries? ’ by Leah Tether was originally published on The Conversation and has republished under a Creative Commons license.

Published on December 08, 2017 00:00

December 7, 2017

12 things you (probably) didn’t know about Pearl Harbor

History Extra

The deadly surprise attack on the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, launched without a declaration of war, made 7 December 1941 “a date which will live in infamy,” declared President Franklin D Roosevelt. Early that Sunday morning, hundreds of Japanese planes sank or damaged 21 warships and destroyed more than 150 planes on nearby airfields; more than 2,000 Americans lost their lives

1) Pearl Harbor was not the beginning of the Pacific War

Japanese forces landed in northern Malaya, then a British colony, a couple of hours before the Pearl Harbor attack; meanwhile a larger Japanese force was disembarking off neutral Thailand. What the Japanese called the Hawaiian Operation was a supporting attack; the main blow was the Southern Operation, directed against Malaya, the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies. And Japan had already been engaged in a full-scale war against China for four-and-a-half years.

2) Pearl Harbor was not the Japanese response to the Hull Note

On 26 November 1941, the American secretary of state Cordell Hull had presented a note to the Japanese. This was not, as is sometimes suggested, an ultimatum; rather it was a statement of what was required for normalisation of relations. According to the note this required the withdrawal of Japanese troops from China and Indochina.

By the time of the Hull Note, Japanese forces were already in motion to carry out the Southern and Hawaiian Operations. Japanese warships of the Pearl Harbor attack force began moving to a forward base in the Kurile Islands in the north of Japan on 17 November; they sailed for Pearl Harbor on the 26th.

3) The Pearl Harbor operation was an extremely difficult and risky one

It was also one of the best-planned and best-prepared operations of the Second World War. Involved was the secret passage of an entire fleet including six aircraft carriers, two battleships and three cruisers over a distance of some 3,700 miles across the North Pacific. The escorting destroyers burnt fuel oil rapidly, and refueling at sea was a new technique that could not be carried out in rough weather. If any of the Japanese ships were damaged during fighting off Hawaii it would be extremely difficult to bring them home. There were strong reasons why American military leaders thought an attack on Hawaii was impractical.

4) Senior officers in the Japanese Navy opposed a full-scale Pearl Harbor attack

The operation was inspired by Admiral Yamamoto, commander-in-chief (C-in-C) of the Combined Fleet. The most important critic was an officer senior to Yamamoto; this was Admiral Nagano, the chief of the Naval General Staff. Nagano had less confidence in air power and he was wary of risking so much of the fleet in a distant operation. He was especially reluctant to risk the entire carrier force so far from Japan at a time when Japan planned attacks thousands of miles away against Malaya and the Philippines. Yamamoto demanded the use of all six big carriers, and had to threaten resignation to get a decision in his favour.

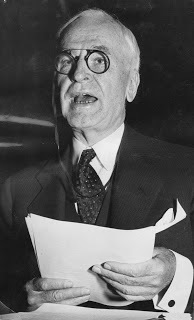

Admiral Nagano. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

5) Japanese submarines were supposed to play a major role in the Pearl Harbor attack

Some 26 Japanese ‘cruiser’ submarines were concentrated around the Hawaiian Islands, their mission to pick off any American ships that survived the main air attack. In the event they achieved nothing during the main attack, although an American carrier was damaged near Hawaii in January. Five small two-man submarines, launched from larger submarines, attempted to enter the harbour early on 7 December but failed. An American destroyer sank one of the boats off the entrance to Pearl Harbor about an hour and 15 minutes before the air attack began, and nearly cost Japan the element of surprise.

6) Neither in Washington nor in London were political and military leaders surprised by the outbreak of war with Japan

This, paradoxically, was a major reason for the failure of American and British intelligence to foresee the Pearl Harbor attack. Much information was gained from ‘intercepts’ of diplomatic correspondence about Japanese preparations. It was assumed these related to a move against Thailand, Malaya or the Dutch East Indies, rather than Hawaii or the Philippines.

The American commanders in the Pacific were sent a war warning on 24 November. President Roosevelt also provided the British with informal assurances that the United States would give support if Britain and Japan went to war. There is no evidence that either President Roosevelt or Prime Minister Churchill had advance warning of the Pearl Harbor attack.

7) The failure to patrol the approaches to Pearl Harbor was partly the result of American offensive war plans

There were a large number of US long-range aircraft in the Pacific, but they were not used to safeguard Hawaii. A force of B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bombers had been sent by the US Army to the Philippines. The 80 PBY Catalina flying boats available to the Navy were assigned to the Philippines or earmarked for offensive actions against the Japanese-held Marshall Islands.

8) The Pearl Harbor attack did not destroy the American Fleet

In the attack on ‘Battleship Row’ on 7 December, two elderly battleships, the Arizona and Oklahoma, were damaged beyond repair by bomb or torpedo hits. Of the 2,026 American sailors and marines killed in the attack, 1,606 had been aboard these two ships (only 218 army personnel were killed in the raid.) Three more battleships (the California, West Virginia and Nevada) sank upright in the shallow water of the harbour. They were salvaged, but two of them did not return to service until 1944 – partly because they underwent comprehensive modernisation.

Three more vessels (the Pennsylvania, Maryland and Tennessee) suffered only minor damage. They were in dry-dock or moored inboard on Battleship Row. In any event, none of the six survivors was fast enough to operate with carrier task forces in later wartime operations. The Pacific Fleet’s three aircraft carriers were away at sea on 7 December, and none of the heavy cruisers were damaged. Three modern carriers were available to the US Navy in the Atlantic, as well as two modern battleships and six older ones.

Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

9) Admiral Nagumo made the correct decision when he did not mount a third attack on Pearl Harbor

The Japanese plan involved two waves of attacking planes, separated by half an hour. Nagumo, commander of the task force, was criticised for not rearming his returning aircraft and sending them back to finish off damaged American ships and oil storage tanks. But Nagumo was obeying his instructions to make a swift getaway. The attack had always been a high-risk enterprise: the elite and well-trained Japanese naval air force was limited in size, and higher losses could be expected if the Americans located the task force. Nagumo did not know where the three US Navy carriers were, nor did he know how many American planes had survived the first attacks.

10) The American commanders at Pearl Harbour were not scapegoats

Admiral Kimmel, C-in-C of the Pacific Fleet, and General Short, C-in-C of US Army forces on Hawaii (including air defence forces) were dismissed a few days after the attack. Some months later, the first US government enquiry found there had been dereliction of duty on the part of these two officers, and that they had made errors of judgment. Consequently, they were retired from their respective services.

Although many writers have attempted to defend Kimmel and Short, the two officers did bear responsibility for the unreadiness of the forces under their command, especially as they had been given a ‘war warning’ [on 24 November]. On the other hand, misjudgments made by superiors of Kimmel and Short in Washington did not come in for open criticism, and Admiral Bloch, a senior admiral responsible for the naval defence of Hawaii, escaped open censure. Poor coordination between the US Army and US Navy was a systemic problem, not one caused by Kimmel and Short.

Admiral Kimmel. (Photo by FPG/Archive Photos/Getty Images) 11)

Hitler’s declaration of war on the US on 11 December was not a result of Pearl Harbor

President Roosevelt suggested openly that when they attacked Pearl Harbor the Japanese had been following German instructions. In fact, Hitler and German military did not know about the proposed Pearl Harbor strike. They were, however, aware that the Japanese were preparing actions in Southeast Asia that would probably lead to war with Britain, and possibly with the US.

Under the Tripartite Pact, signed with Japan and Italy in September 1940, Germany was obliged to go to war only if the USA attacked Japan, not if Japan attacked the USA. But just before the outbreak of war the Germans secretly agreed to support the Japanese if they went to war with the USA for any reason, including a Japanese attack on American territory. President Roosevelt knew about this agreement from intercepted Japanese diplomatic correspondence. As a result, when he asked Congress for a Declaration of War on 8 December Roosevelt requested action only against Japan. In view of isolationist sentiment in the United States, the White House deemed it advisable to let the Germans make the first declaration of war, which Hitler announced in the Reichstag on 11 December. After this the president turned again to Congress and received a unanimous declaration of war against Germany and Italy.

12) For Japan, Pearl Harbor was both a success and a failure

The attack did change the strategic situation. The pre-war military strategy of Britain and the US was to assemble strong forces in the west (at Singapore) and the east (at Hawaii), to deter Japan by threatening a two-front war. Pearl Harbor removed the American part of the deterrent. It made possible the rapid conquest of Malaya, the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies.

On the other hand, Admiral Yamamoto had hoped to destroy the American carrier force, and this did not happen. And by mounting a surprise attack without a declaration of war, on a Sunday morning and killing several thousand Americans, the Japanese put American public opinion totally behind the war effort.

Evan Mawdsley is professor of history at the University of Glasgow and author of December 1941: Twelve Days that Began a World War (Yale University Press, 2011).

Published on December 07, 2017 00:00

December 5, 2017

Three Roman Shipwrecks with Hoard of Treasures Discovered in Alexandria

Ancient Origins

A team of archaeologists in Egypt has recently announced the discovery of three underwater shipwrecks full of treasure and other valuable objects that date back to the Roman Era in Abu Qir Bay, Alexandria.

Three Impressive Underwater Shipwrecks Uncovered

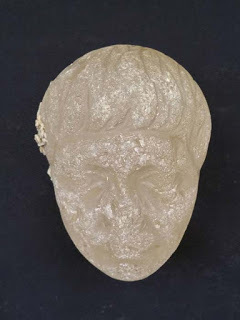

The three shipwrecks were unearthed during excavations in the Mediterranean Sea carried out by the European Institute of Underwater Archaeology and the Supreme Council of Antiquities, as Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, Mostafa al-Waziry, announced. According to Egypt Independent, Waziry added in a press statement that the archaeological mission also discovered a Roman head carved in crystal that could possibly belong to the commander of the Roman armies of “Antonio”, in addition to three gold coins dating back to the Emperor “Octavius”. The discoveries took place at the coast of the northern city of Alexandria, specifically in its Abu Qir Bay.

The carved crystal head that was found at the site of the wrecks. (Image: Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities)

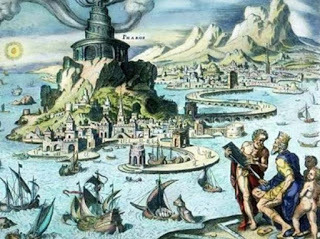

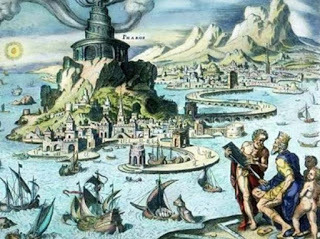

Pharos of Alexandria: Idealized representation of the Bay of Alexandria. (Public Domain )

Alexandria’s Vast Underwater Treasures

Alexandria, located on the Mediterranean coast in Egypt, has seen many changes in its 2,300 year history. Founded by Greek general Alexander the Great in 331 BC, at its height it rivalled Rome in its wealth and size, and was the seat for the Ptolemaic dynasty. However, through history not all agreed on how to regard the Hellenistic city with a royal Egyptian past. An underwater temple discovered by marine divers off the eastern coast shed light on the pharaonic nature of ancient Alexandria.

As previously reported in Ancient Origins, Ptolemaic Alexandria has been regarded, in academic circles, not as part of Egypt, but as a separate Greek polis, or city-state, by the borders of Egypt. However, in 1998, an important archaeological discovery was made in Alexandria which confirmed the pharaonic nature of Egyptian Alexandria. Under the heading “Sea gives up Cleopatra’s treasures”, the London Sunday Times reported the story on 25 October 1998: “Secrets of Cleopatra’s fabled royal palace, in which she wooed Julius Caesar, have been retrieved from beneath the waves of the Mediterranean sea, where they have lain for more than 1,600 years.” This remarkable discovery came about after the European Institute of Underwater Archaeology (IEASM) had been given permission in the 1990s to work in the east part of the Eastern Harbor, where the Ptolemaic royal quarter was situated.

After some years of mapping and searching the area, Frank Goddio, the French leader of the underwater team of archaeologists, was able to announce before the end of 1998 that he had discovered the royal palace of Cleopatra (51-30 BC), the last of the Ptolemaic rulers.

Ancient Egyptian statues found beneath the waves of Alexandria's Eastern Harbor. (Credit: The Hilti Foundation)

Goddio’s divers found marble floors on the seabed which he believes established for the first time the precise location of Cleopatra’s palace. They also found lumps of red granite and broken columns on the submerged island of Antirhodos, which provided Goddio with further evidence of the site of the royal quarters. Remains of Cleopatra’s royal palace were retrieved from beneath the waters of the Mediterranean Sea where they had disappeared for 17 centuries. The divers reported seeing columns and capitals in disorder, kilns and basins - some of which were described as the so-called ‘Baths of Cleopatra’; great blocks of dressed limestone, statues of Egyptian divinities, and even walls.

One of the Roman coins found in the shipwrecks (Image: Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities)

Fourth Shipwreck May be Unearthed Soon

Almost two decades later, Alexandria keeps delivering extremely significant archaeological treasures and will most likely continue to do so for many years to come. Dr. Osama Alnahas, Head of the Central Department of the Underwater Antiquities, stated as Egypt Independent reported, that the initial excavations indicate that a fourth shipwreck remains could be unearthed very soon. According to Dr. Alnahas the team has unearthed large wooden planks, as well as pieces of pottery vessels that most likely represent the ships’ hull and cargo.

Dr. Ayman Ashmawy, Head of the Ancient Egyptian Antiquities Sector, informed the press that the archaeological team launched its excavation works last September. Ultimately, Egypt Independent reports that underwater exploration by both projects have included a research of the soil in both the eastern port and the Abu Qir Bay, underwater excavations at the Heraklion sunken city in Abu Qir Bay which includes the discovery of a votive bark of the god Osiris, as well as the completion of the conservation and documentation works.

Top image: Sunken ships, statues and treasure have been found under water at in bay near Alexandria. (Image: Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

A team of archaeologists in Egypt has recently announced the discovery of three underwater shipwrecks full of treasure and other valuable objects that date back to the Roman Era in Abu Qir Bay, Alexandria.

Three Impressive Underwater Shipwrecks Uncovered

The three shipwrecks were unearthed during excavations in the Mediterranean Sea carried out by the European Institute of Underwater Archaeology and the Supreme Council of Antiquities, as Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, Mostafa al-Waziry, announced. According to Egypt Independent, Waziry added in a press statement that the archaeological mission also discovered a Roman head carved in crystal that could possibly belong to the commander of the Roman armies of “Antonio”, in addition to three gold coins dating back to the Emperor “Octavius”. The discoveries took place at the coast of the northern city of Alexandria, specifically in its Abu Qir Bay.

The carved crystal head that was found at the site of the wrecks. (Image: Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities)

Pharos of Alexandria: Idealized representation of the Bay of Alexandria. (Public Domain )

Alexandria’s Vast Underwater Treasures

Alexandria, located on the Mediterranean coast in Egypt, has seen many changes in its 2,300 year history. Founded by Greek general Alexander the Great in 331 BC, at its height it rivalled Rome in its wealth and size, and was the seat for the Ptolemaic dynasty. However, through history not all agreed on how to regard the Hellenistic city with a royal Egyptian past. An underwater temple discovered by marine divers off the eastern coast shed light on the pharaonic nature of ancient Alexandria.

As previously reported in Ancient Origins, Ptolemaic Alexandria has been regarded, in academic circles, not as part of Egypt, but as a separate Greek polis, or city-state, by the borders of Egypt. However, in 1998, an important archaeological discovery was made in Alexandria which confirmed the pharaonic nature of Egyptian Alexandria. Under the heading “Sea gives up Cleopatra’s treasures”, the London Sunday Times reported the story on 25 October 1998: “Secrets of Cleopatra’s fabled royal palace, in which she wooed Julius Caesar, have been retrieved from beneath the waves of the Mediterranean sea, where they have lain for more than 1,600 years.” This remarkable discovery came about after the European Institute of Underwater Archaeology (IEASM) had been given permission in the 1990s to work in the east part of the Eastern Harbor, where the Ptolemaic royal quarter was situated.

After some years of mapping and searching the area, Frank Goddio, the French leader of the underwater team of archaeologists, was able to announce before the end of 1998 that he had discovered the royal palace of Cleopatra (51-30 BC), the last of the Ptolemaic rulers.

Ancient Egyptian statues found beneath the waves of Alexandria's Eastern Harbor. (Credit: The Hilti Foundation)

Goddio’s divers found marble floors on the seabed which he believes established for the first time the precise location of Cleopatra’s palace. They also found lumps of red granite and broken columns on the submerged island of Antirhodos, which provided Goddio with further evidence of the site of the royal quarters. Remains of Cleopatra’s royal palace were retrieved from beneath the waters of the Mediterranean Sea where they had disappeared for 17 centuries. The divers reported seeing columns and capitals in disorder, kilns and basins - some of which were described as the so-called ‘Baths of Cleopatra’; great blocks of dressed limestone, statues of Egyptian divinities, and even walls.

One of the Roman coins found in the shipwrecks (Image: Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities)

Fourth Shipwreck May be Unearthed Soon

Almost two decades later, Alexandria keeps delivering extremely significant archaeological treasures and will most likely continue to do so for many years to come. Dr. Osama Alnahas, Head of the Central Department of the Underwater Antiquities, stated as Egypt Independent reported, that the initial excavations indicate that a fourth shipwreck remains could be unearthed very soon. According to Dr. Alnahas the team has unearthed large wooden planks, as well as pieces of pottery vessels that most likely represent the ships’ hull and cargo.

Dr. Ayman Ashmawy, Head of the Ancient Egyptian Antiquities Sector, informed the press that the archaeological team launched its excavation works last September. Ultimately, Egypt Independent reports that underwater exploration by both projects have included a research of the soil in both the eastern port and the Abu Qir Bay, underwater excavations at the Heraklion sunken city in Abu Qir Bay which includes the discovery of a votive bark of the god Osiris, as well as the completion of the conservation and documentation works.

Top image: Sunken ships, statues and treasure have been found under water at in bay near Alexandria. (Image: Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on December 05, 2017 23:00

Viking Camp Complete with Ship Building and Weapon Workshops Unearthed in England

Ancient Origins

The craftsmanship and shipbuilding capabilities of the Vikings are often overshadowed by stereotypical images of violent invaders, plunderers, and explorers. But it is worthwhile to remind ourselves that there were everyday aspects to the lives of the Norse men and women as well. Discoveries like recent excavations in Derbyshire help us reflect on the oft-forgotten skills of Vikings away from their homeland.

A press release by the University of Bristol says that the Viking winter campsite from 873-874 has been known about in the village of Repton since 1975. However, the recent excavations by a team of University of Bristol archaeologists has exposed a larger area for the site to include sections used as workshops and for ship repairs.

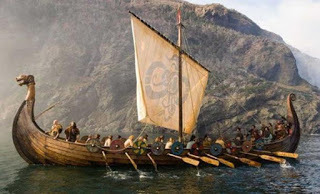

A Viking ship. ( The-Wanderling)

According to the Daily Mail, ground penetrating radar revealed pathways and gravel platforms which were probably used as the foundations for tents or temporary timber buildings. One of the paths led to a mass grave site inside a deliberately damaged Saxon building which was discovered in the 1980s. New radiocarbon dating of a sample of the almost 300 people suggests that these are the remains of warriors who died in battle around the time of the camp’s usage. The team also noted that the building which housed the dead had once been used for a workshop.

Regarding artifacts, the archaeologists found some lead game pieces at the Viking camp. Broken pieces of weapons such as arrows and battle axes suggest that metal working took place at the site and Viking ship nails provide a clear indication for repairs likely taking place there as well.

Top: Fragment of axe-head found in association with Viking camp material. Bottom: Arrowhead found in association with Viking camp material. ( Cat Jarman, University of Bristol )

Speaking on the site, Cat Jarman, a PhD student at the University of Bristol, said:

“Our dig shows there was a lot more to the Viking Camp at Repton than what we may have thought in the past. It covered a much larger area than was once presumed – at least the area of the earlier monastery – and we are now starting to understand the wide range of activities that took place in these camps.”

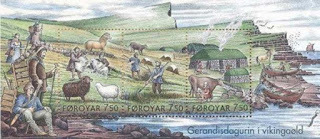

Stamps showing ‘Everyday Life in the Viking Age.’ ( Public Domain )

The existence of the Viking winter camp was documented in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. It mentions the ‘Great Army’ annexing the kingdom of the Mercian king Burghred in 873. In fact, it has been argued that part of the reason that location was chosen for the camp was due to the nearby monastery which held the bodies of Mercian kings. The closeness to the river Trent would have also played a role.

The results of the excavations will be presented on the BBC Four series ‘Digging for Britain’ on November 22.

Students excavating the winter camp. ( Cat Jarman, University of Bristol )

Vikings are certainly a hot topic these days. Dramas such as Vikings (History Channel) and The Last Kingdom (BBC) have propelled an interest in the Norsemen to a new generation. Despite their popularity, there is much that people still misunderstand about the Viking age and its people. As Mark Miller reflected in a previous Ancient Origins article , a recent survey of 2,000 people in the UK shows,

“many British people are clueless about the Vikings. In fact, 20 percent didn’t even know Vikings were from Scandinavia. And 10 percent think the Viking Age happened much later, mistakenly thinking from the 15th to 18th centuries. Another 25 percent did not know the Vikings attacked the British Isles, instead thinking they raided South America.”

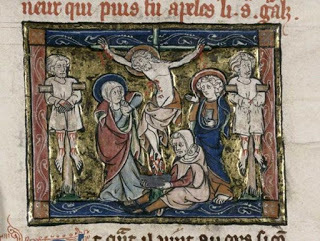

Danes invading England. From "Miscellany on the life of St. Edmund," 12th century. ( Public Domain )

A popular error regarding the appearance of a Viking is the 19th century myth of the Viking horned helmet . This stereotypical image has been traced to the 1800s, when Gustav Malmström, a Swedish artist, and Wagner’s opera costume designer Carl Emil Doepler both decided to depict Vikings in horned helmets. In contrast, depictions of warriors from the Viking age show them in iron or leather helmets, if they are even wearing the headgear at all.

A stereotypical painting by Mary McGregor from 1908 of Leif Ericson landing at Vinland ( Public Domain )

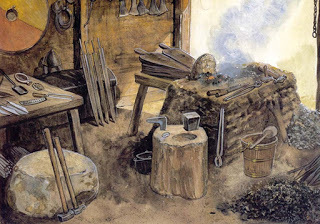

Top Image: A Viking weapon workshop. Credit: Kevin Roddy

By Alicia McDermott

Published on December 05, 2017 00:00

December 3, 2017

Medieval Treasure Unearthed at the Abbey of Cluny

Ancient Origins

In mid-September, a large treasure was unearthed during a dig at the Abbey of Cluny, in the French department of Saône-et-Loire: 2,200 silver deniers and oboles, 21 Islamic gold dinars, a signet ring, and other objects made of gold. Never before has such a large cache of silver deniers been discovered. Nor have gold coins from Arab lands, silver deniers, and a signet ring ever been found hoarded together within a single, enclosed complex.

Anne Baud, an academic at the Université Lumière Lyon 2, and Anne Flammin, a CNRS engineer - both from the Laboratoire Archéologie et Archéométrie (CNRS / Université Lumière Lyon 2 / Claude Bernard Lyon 1 University) -- led the archaeological investigation, in collaboration with a team of 9 students from the Université Lumière Lyon 2 and researchers from the Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée Jean Pouilloux (CNRS / Université Lumière Lyon 2).

Gold dinars were found. (Credit: Alexis Grattier-Université Lumière Lyon 2)

The excavation campaign, authorized by the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté Regional Department of Cultural Affairs (DRAC), began in mid-September and ended in late October. It is part of a vast research program focused on the Abbey of Cluny. Students in the Master of Archaeology and Archaeological Science program at the Université Lumière Lyon 2 have been participating in archaeological digs at the Abbey of Cluny since 2015. This experience in the field complements their academic training and gives them an insight into professional archaeology.

Cluny Abbey (or Cluni, or Clugny) is a Benedictine monastery in Cluny, Saône-et-Loire, built in Romanesque style (CC BY 2.0)

At the site, the team led by Anne Baud et Anne Flammin, including the students from the Université Lumière Lyon 2, discovered a treasure consisting of: