MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 34

January 2, 2018

Norwegian Vikings Cultivated Cannabis

Ancient Origins

BY THORNEWS

On a secluded Iron Age farm in Southern Norway, archaeological findings show that it was common to cultivate cannabis in the Viking Age. The question is how the Vikings used the fibers, seeds and oil from this versatile plant.

For more than fifty years, samples from archaeological excavations at Sosteli Iron Age Farm have been stored in the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, according to an article on research portal Forskning.no.

Analyses show that in the period between the years 650 and 800 AD, i.e. the beginning of the Viking Age, hemp was cultivated on the remote mountain farm.

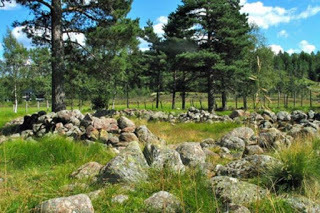

1300 years ago, hemp was cultivated on Sosteli Iron Age Farm in Vest-Agder county. (Photo: Morten Teinum / Visit Sørlandet)

This is not the first time that traces of cultivation this far back in time have been found, but Sosteli stands out.

“In the other cases, it is only made individual findings of pollen grains. Here, it is discovered very much more,” archaeologist and county conservator Frans-Arne Stylegar told forskning.no.

A Hemp field in Brittany, France. Is it from this area the Norsemen imported hemp seeds back to Scandinavia? (Photo: Barbetorte/ Wikimedia Commons)

Sosteli is located much less centrally than other places where similar findings have been made, indicating that cannabis cultivation was common throughout the Viking Age.

Textiles and Ropes

Hemp is the same plant as the cannabis plant used for hashish production. It is however uncertain whether the Vikings used cannabis as a drug.

The plant was most likely used for production of textiles and ropes.

Hemp fibre (public domain)

Previously, there have been several findings of hemp seeds in Eastern Norway, including in Hamar municipality, dating back to the 400s AD.

In the Oseberg ship burial mound, a little leather pouch full of cannabis seeds was found. It belonged to an elderly woman aged between 70 and 80.

The skeleton reveals that she had various health problems – most likely cancer that caused her death – and it is not unlikely that the seeds were used as painkillers.

Scientists do not know if the Vikings used cannabis as a drug, and there are no sources that neither confirm nor deny if they did.

Top image: A cannabis crop (public domain)

The article ‘Norwegian Vikings Cultivated Hemp’ by Thor Lanesskog was originally published on ThorNews and has been republished with permission.

Published on January 02, 2018 00:00

December 31, 2017

The Ancient Origins of New Year’s Celebrations

Ancient Origins

On the 1st January of every year, many countries around the world celebrate the beginning of a new year. But there is nothing new about New Year’s. In fact, festivals and celebrations marking the beginning of the calendar have been around for thousands of years. While some festivities were simply a chance to drink and be merry, many other New Year celebrations were linked to agricultural or astronomical events. In Egypt, for instance, the year began with the annual flooding of the Nile, which coincided with the rising of the star Sirius. The Phoenicians and Persians began their new year with the spring equinox, and the Greeks celebrated it on the winter solstice. The first day of the Chinese New Year, meanwhile, occurred with the second new moon after the winter solstice.

The Celebration of Akitu in Babylon

The earliest recorded New Year’s festivity dates back some 4,000 years to ancient Babylon, and was deeply intertwined with religion and mythology. For the Babylonians of ancient Mesopotamia, the first new moon following the vernal equinox—the day in late March with an equal amount of sunlight and darkness—heralded the start of a new year and represented the rebirth of the natural world. They marked the occasion with a massive religious festival called Akitu (derived from the Sumerian word for barley, which was cut in the spring) that involved a different ritual on each of its 11 days. During the Akitu, statues of the gods were paraded through the city streets, and rites were enacted to symbolize their victory over the forces of chaos. Through these rituals the Babylonians believed the world was symbolically cleansed and recreated by the gods in preparation for the new year and the return of spring.

In addition to the new year, Atiku celebrated the mythical victory of the Babylonian sky god Marduk over the evil sea goddess Tiamat and served an important political purpose: it was during this time that a new king was crowned or that the current ruler’s divine mandate was renewed. One fascinating aspect of the Akitu involved a kind of ritual humiliation endured by the Babylonian king. This peculiar tradition saw the king brought before a statue of the god Marduk, stripped of his royal regalia, slapped and dragged by his ears in the hope of making him cry. If royal tears were shed, it was seen as a sign that Marduk was satisfied and had symbolically extended the king’s rule.

Ancient Roman Celebration of Janus

The Roman New Year also originally corresponded with the vernal equinox. The early Roman calendar consisted of 10 months and 304 days, with each new year beginning at the vernal equinox. According to tradition, the calendar was created by Romulus, the founder of Rome, in the eighth century B.C. However, over the centuries, the calendar fell out of sync with the sun, and in 46 B.C. the emperor Julius Caesar decided to solve the problem by consulting with the most prominent astronomers and mathematicians of his time. He introduced the Julian calendar, a solar-based calendar which closely resembles the more modern Gregorian calendar that most countries around the world use today.

As part of his reform, Caesar instituted January 1 as the first day of the year, partly to honour the month’s namesake: Janus, the Roman god of change and beginnings, whose two faces allowed him to look back into the past and forward into the future. This idea became tied to the concept of transition from one year to the next.

Romans would celebrate January 1st by offering sacrifices to Janus in the hope of gaining good fortune for the New Year, decorating their homes with laurel branches and attending raucous parties. This day was seen as setting the stage for the next twelve months, and it was common for friends and neighbours to make a positive start to the year by exchanging well wishes and gifts of figs and honey with one another.

Middle Ages: January 1st Abolished

In medieval Europe, however, the celebrations accompanying the New Year were considered pagan and unchristian-like, and in 567 AD the Council of Tours abolished January 1st as the beginning of the year, replacing it with days carrying more religious significance, such as December 25th or March 25th, the Feast of the Annunciation, also called “Lady Day”.

The date of January 1st was also given Christian significance and became known as the Feast of the Circumcision, considered to be the eighth day of Christ's life counting from December 25th and following the Jewish tradition of circumcision eight days after birth on which the child is formally given his or her name. However, the date of December 25th for the birth of Jesus is debatable.

Gregorian Calendar: January 1st Restored

In 1582, after reform of the Gregorian calendar, Pope Gregory XIII re-established January 1st as New Year’s Day. Although most Catholic countries adopted the Gregorian calendar almost immediately, it was only gradually adopted among Protestant countries. The British, for example, did not adopt the reformed calendar until 1752. Until then, the British Empire, and their American colonies, still celebrated the New Year in March.

By April Holloway

On the 1st January of every year, many countries around the world celebrate the beginning of a new year. But there is nothing new about New Year’s. In fact, festivals and celebrations marking the beginning of the calendar have been around for thousands of years. While some festivities were simply a chance to drink and be merry, many other New Year celebrations were linked to agricultural or astronomical events. In Egypt, for instance, the year began with the annual flooding of the Nile, which coincided with the rising of the star Sirius. The Phoenicians and Persians began their new year with the spring equinox, and the Greeks celebrated it on the winter solstice. The first day of the Chinese New Year, meanwhile, occurred with the second new moon after the winter solstice.

The Celebration of Akitu in Babylon

The earliest recorded New Year’s festivity dates back some 4,000 years to ancient Babylon, and was deeply intertwined with religion and mythology. For the Babylonians of ancient Mesopotamia, the first new moon following the vernal equinox—the day in late March with an equal amount of sunlight and darkness—heralded the start of a new year and represented the rebirth of the natural world. They marked the occasion with a massive religious festival called Akitu (derived from the Sumerian word for barley, which was cut in the spring) that involved a different ritual on each of its 11 days. During the Akitu, statues of the gods were paraded through the city streets, and rites were enacted to symbolize their victory over the forces of chaos. Through these rituals the Babylonians believed the world was symbolically cleansed and recreated by the gods in preparation for the new year and the return of spring.

In addition to the new year, Atiku celebrated the mythical victory of the Babylonian sky god Marduk over the evil sea goddess Tiamat and served an important political purpose: it was during this time that a new king was crowned or that the current ruler’s divine mandate was renewed. One fascinating aspect of the Akitu involved a kind of ritual humiliation endured by the Babylonian king. This peculiar tradition saw the king brought before a statue of the god Marduk, stripped of his royal regalia, slapped and dragged by his ears in the hope of making him cry. If royal tears were shed, it was seen as a sign that Marduk was satisfied and had symbolically extended the king’s rule.

Ancient Roman Celebration of Janus

The Roman New Year also originally corresponded with the vernal equinox. The early Roman calendar consisted of 10 months and 304 days, with each new year beginning at the vernal equinox. According to tradition, the calendar was created by Romulus, the founder of Rome, in the eighth century B.C. However, over the centuries, the calendar fell out of sync with the sun, and in 46 B.C. the emperor Julius Caesar decided to solve the problem by consulting with the most prominent astronomers and mathematicians of his time. He introduced the Julian calendar, a solar-based calendar which closely resembles the more modern Gregorian calendar that most countries around the world use today.

As part of his reform, Caesar instituted January 1 as the first day of the year, partly to honour the month’s namesake: Janus, the Roman god of change and beginnings, whose two faces allowed him to look back into the past and forward into the future. This idea became tied to the concept of transition from one year to the next.

Romans would celebrate January 1st by offering sacrifices to Janus in the hope of gaining good fortune for the New Year, decorating their homes with laurel branches and attending raucous parties. This day was seen as setting the stage for the next twelve months, and it was common for friends and neighbours to make a positive start to the year by exchanging well wishes and gifts of figs and honey with one another.

Middle Ages: January 1st Abolished

In medieval Europe, however, the celebrations accompanying the New Year were considered pagan and unchristian-like, and in 567 AD the Council of Tours abolished January 1st as the beginning of the year, replacing it with days carrying more religious significance, such as December 25th or March 25th, the Feast of the Annunciation, also called “Lady Day”.

The date of January 1st was also given Christian significance and became known as the Feast of the Circumcision, considered to be the eighth day of Christ's life counting from December 25th and following the Jewish tradition of circumcision eight days after birth on which the child is formally given his or her name. However, the date of December 25th for the birth of Jesus is debatable.

Gregorian Calendar: January 1st Restored

In 1582, after reform of the Gregorian calendar, Pope Gregory XIII re-established January 1st as New Year’s Day. Although most Catholic countries adopted the Gregorian calendar almost immediately, it was only gradually adopted among Protestant countries. The British, for example, did not adopt the reformed calendar until 1752. Until then, the British Empire, and their American colonies, still celebrated the New Year in March.

By April Holloway

Published on December 31, 2017 23:30

December 30, 2017

The destruction of the Great Library of Alexandria

Ancient Origins

Alexandria, one of the greatest cities of the ancient world, was founded by Alexander the Great after his conquest of Egypt in 332 BC. After the death of Alexander in Babylon in 323 BC, Egypt fell to the lot of one of his lieutenants, Ptolemy. It was under Ptolemy that the newly-founded Alexandria came to replace the ancient city of Memphis as the capital of Egypt. This marked the beginning of the rise of Alexandria. Yet, no dynasty can survive for long without the support of their subjects, and the Ptolemies were keenly aware of this. Thus, the early Ptolemaic kings sought to legitimize their rule through a variety of ways, including assuming the role of pharaoh, founding the Graeco-Roman cult of Serapis, and becoming the patrons of scholarship and learning (a good way to show off one’s wealth, by the way). It was this patronage that resulted in the creation of the great Library of Alexandria by Ptolemy. Over the centuries, the Library of Alexandria was one of the largest and most significant libraries in the ancient world. The great thinkers of the age, scientists, mathematicians, poets from all civilizations came to study and exchange ideas. As many as 700,000 scrolls filled the shelves. However, in one of the greatest tragedies of the academic world, the Library became lost to history and scholars are still not able to agree on how it was destroyed.

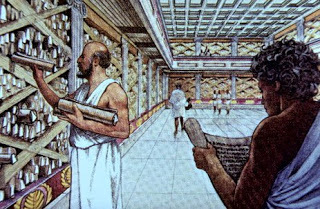

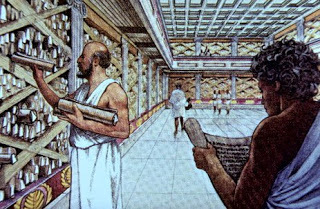

An artist’s depiction of the Library of Alexandria. Image source.

Perhaps one of the most interesting accounts of its destruction comes from the accounts of the Roman writers. According to several authors, the Library of Alexandria was accidentally destroyed by Julius Caesar during the siege of Alexandria in 48 BC. Plutarch, for instance, provides this account:

when the enemy tried to cut off his (Julius Caesar’s) fleet, he was forced to repel the danger by using fire, and this spread from the dockyards and destroyed the great library. (Plutarch, The Life of Julius Caesar, 49.6)

This account is dubious, however, as the Musaeum (or Mouseion) at Alexandria, which was right next to the library was unharmed, as it was mentioned by the geographer Strabo about 30 years after Caesar’s siege of Alexandria. Nevertheless, Strabo does not mention the Library of Alexandria itself, thereby supporting the claim that Caesar was responsible for burning it down. However, as the Library was attached to the Musaeum, and Strabo did mention the latter, it is possible that the library was still in existence during Strabo’s time. The omission of the library can perhaps be attributed either to the possibility that Strabo felt no need to mention the library, as he had already mentioned the Musaeum, or that the library was no longer the centre of scholarship that it once was (the idea of ‘budget cuts’ seems increasingly probable). In addition, it has been suggested that it was not the library, but the warehouses near the port, which stored manuscripts, that was destroyed by Caesar’s fire.

The second possible culprit would be the Christians of the 4th century AD. In 391 AD, the Emperor Theodosius issued a decree that officially outlawed pagan practices. Thus, the Serapeum or Temple of Serapis in Alexandria was destroyed. However, this was not the Library of Alexandria, or for that matter, a library of any sort. Furthermore, no ancient sources mention the destruction of any library at this time at all. Hence, there is no evidence that the Christians of the 4th century destroyed the Library of Alexandria.

The last possible perpetrator of this crime would be the Muslim Caliph, Omar. According to this story, a certain “John Grammaticus” (490–570) asks Amr, the victorious Muslim general, for the “books in the royal library." Amr writes to the Omar for instructions and Omar replies: "If those books are in agreement with the Quran, we have no need of them; and if these are opposed to the Quran, destroy them.” There are at least two problems with this story. Firstly, there is no mention of any library, only books. Secondly, this was written by a Syrian Christian writer, and may have been invented to tarnish the image of Omar.

Unfortunately, archaeology has not been able to contribute much to this mystery. For a start, papyri have rarely been found in Alexandria, possibly due to the climatic condition, which is unfavourable for the preservation of organic material. Secondly, the remains of the Library of Alexandria itself have not been discovered. This is due to the fact that Alexandria is still inhabited by people today and only salvage excavations are allowed to be carried out by archaeologists.

While it may be convenient to blame one man or group of people for the destruction of what many consider to be the greatest library in the ancient world, it may be over-simplifying the matter. The library may not have gone up in flames at all, but rather could have been gradually abandoned over time. If the Library was created for the display of Ptolemaic wealth, then its decline could also have been linked to an economic decline. As Ptolemaic Egypt gradually declined over the centuries, this may have also had an effect on the state of the Library of Alexandria. If the Library did survive into the first few centuries AD, its golden days would have been in the past, as Rome became the new centre of the world.

Featured image: One of the theories suggests that Library of Alexandria was burned down. ‘The Burning of the Library of Alexandria’, by Hermann Goll (1876).

By Ḏḥwty

Alexandria, one of the greatest cities of the ancient world, was founded by Alexander the Great after his conquest of Egypt in 332 BC. After the death of Alexander in Babylon in 323 BC, Egypt fell to the lot of one of his lieutenants, Ptolemy. It was under Ptolemy that the newly-founded Alexandria came to replace the ancient city of Memphis as the capital of Egypt. This marked the beginning of the rise of Alexandria. Yet, no dynasty can survive for long without the support of their subjects, and the Ptolemies were keenly aware of this. Thus, the early Ptolemaic kings sought to legitimize their rule through a variety of ways, including assuming the role of pharaoh, founding the Graeco-Roman cult of Serapis, and becoming the patrons of scholarship and learning (a good way to show off one’s wealth, by the way). It was this patronage that resulted in the creation of the great Library of Alexandria by Ptolemy. Over the centuries, the Library of Alexandria was one of the largest and most significant libraries in the ancient world. The great thinkers of the age, scientists, mathematicians, poets from all civilizations came to study and exchange ideas. As many as 700,000 scrolls filled the shelves. However, in one of the greatest tragedies of the academic world, the Library became lost to history and scholars are still not able to agree on how it was destroyed.

An artist’s depiction of the Library of Alexandria. Image source.

Perhaps one of the most interesting accounts of its destruction comes from the accounts of the Roman writers. According to several authors, the Library of Alexandria was accidentally destroyed by Julius Caesar during the siege of Alexandria in 48 BC. Plutarch, for instance, provides this account:

when the enemy tried to cut off his (Julius Caesar’s) fleet, he was forced to repel the danger by using fire, and this spread from the dockyards and destroyed the great library. (Plutarch, The Life of Julius Caesar, 49.6)

This account is dubious, however, as the Musaeum (or Mouseion) at Alexandria, which was right next to the library was unharmed, as it was mentioned by the geographer Strabo about 30 years after Caesar’s siege of Alexandria. Nevertheless, Strabo does not mention the Library of Alexandria itself, thereby supporting the claim that Caesar was responsible for burning it down. However, as the Library was attached to the Musaeum, and Strabo did mention the latter, it is possible that the library was still in existence during Strabo’s time. The omission of the library can perhaps be attributed either to the possibility that Strabo felt no need to mention the library, as he had already mentioned the Musaeum, or that the library was no longer the centre of scholarship that it once was (the idea of ‘budget cuts’ seems increasingly probable). In addition, it has been suggested that it was not the library, but the warehouses near the port, which stored manuscripts, that was destroyed by Caesar’s fire.

The second possible culprit would be the Christians of the 4th century AD. In 391 AD, the Emperor Theodosius issued a decree that officially outlawed pagan practices. Thus, the Serapeum or Temple of Serapis in Alexandria was destroyed. However, this was not the Library of Alexandria, or for that matter, a library of any sort. Furthermore, no ancient sources mention the destruction of any library at this time at all. Hence, there is no evidence that the Christians of the 4th century destroyed the Library of Alexandria.

The last possible perpetrator of this crime would be the Muslim Caliph, Omar. According to this story, a certain “John Grammaticus” (490–570) asks Amr, the victorious Muslim general, for the “books in the royal library." Amr writes to the Omar for instructions and Omar replies: "If those books are in agreement with the Quran, we have no need of them; and if these are opposed to the Quran, destroy them.” There are at least two problems with this story. Firstly, there is no mention of any library, only books. Secondly, this was written by a Syrian Christian writer, and may have been invented to tarnish the image of Omar.

Unfortunately, archaeology has not been able to contribute much to this mystery. For a start, papyri have rarely been found in Alexandria, possibly due to the climatic condition, which is unfavourable for the preservation of organic material. Secondly, the remains of the Library of Alexandria itself have not been discovered. This is due to the fact that Alexandria is still inhabited by people today and only salvage excavations are allowed to be carried out by archaeologists.

While it may be convenient to blame one man or group of people for the destruction of what many consider to be the greatest library in the ancient world, it may be over-simplifying the matter. The library may not have gone up in flames at all, but rather could have been gradually abandoned over time. If the Library was created for the display of Ptolemaic wealth, then its decline could also have been linked to an economic decline. As Ptolemaic Egypt gradually declined over the centuries, this may have also had an effect on the state of the Library of Alexandria. If the Library did survive into the first few centuries AD, its golden days would have been in the past, as Rome became the new centre of the world.

Featured image: One of the theories suggests that Library of Alexandria was burned down. ‘The Burning of the Library of Alexandria’, by Hermann Goll (1876).

By Ḏḥwty

Published on December 30, 2017 23:30

December 29, 2017

Acta Diurna: The Telegraph of Ancient Rome, Bringing You All the Latest Gladiator Combat News

Ancient Origins

Roman emperor conquers new lands !’ ‘Five new ways to use your fish paste .’ ‘When do the stars say you will marry?’ ‘ Viae militares expand our reach to foreign lands.’ These may have been some of the headlines you would read in the Roman Acta Diurna – the daily notices many call the precursor to the modern daily newspaper.

The Roman Acta Diurna (translated from the Latin to mean ‘Daily Acts’ or ‘Daily Public Records’) were the daily public notices that were posted in certain public places around the ancient city of Rome. These notices kept the ancient inhabitants of Rome up to date with current events. They contained various forms of news, ranging from the official to entertainment, and even astrological readings.

Roman Fish Market. Arch of Octavius. ( Public Domain )

The Acta Diurna was posted in public places around the city. Content of the Roman Stone, Metal, or Papyri “Newspapers” The Acta Diruna is said to have first appeared around 131/130 BC during the Roman Republic. At this point of time, the Acta Diurna , which were known also as the Acta Popidi or Acta Publica , was carved on stone or metal. As the Acta Diurna were meant to reach a public audience, they were placed at public places, such as the forum, the markets, or the thermal baths. Initially these notices reported ‘serious’ news of importance to the Roman populace, such as the results of legal proceedings, and the outcomes of trials.

‘Cicero Denounces Catiline’ (1889) by Cesare Maccari. ( Public Domain ) Representation of a sitting of the Roman Senate. Initially the notices reported ‘serious’ news of importance to the Roman populace, such as the results of legal proceedings, and the outcomes of trials.

As time went by, the range of topics reported by the Acta Diurna increased as well. The contents of the Roman notices began to include public announcements, such as military victories, and the price of grain. Apart from these, the Acta Diurna also included other pieces of noteworthy information, such as notable births, marriages, and deaths, as well as news about gladiatorial combats and other games that were being held in the city. The Acta Diurna even included a gossip column, which often contained the latest amorous adventures of Rome’s rich and famous.

By the time of the 1st century BC, the Acta Diurna was no longer carved on stone or metal. Instead, they were hand-written, most likely on sheets of papyri. They continued to be posted in public places, and after a couple of days, were taken down to be archived. Unfortunately, papyrus is not the most durable of materials, and no intact copy of the Acta Diurna is known to have survived till the present day.

Fragment from the front of a sarcophagus showing a Roman marriage ceremony. ( CC BY SA 4.0 ) Notable marriages were mentioned in the Acta Diurna too.

Scribes Copied the News for Wealthy Romans Living Outside the City

The Acta Diurna were very popular indeed. For example, the rich (presumably those living outside of Rome) would often send scribes to the city to seek out the latest edition of the Acta Diurna . These would then be copied and brought back to their patrons. Provincial governors would also send scribes to make copies of the Acta Diurna for them, so that they were kept abreast of the latest happenings in the capital. During this time, the concept of copyright was not in existence, and the scribes could copy the Acta Diurna freely.

The Acta Diurna were used also as a source of information by various ancient authors. Suetonius, the author of The Lives of the Twelve Caesars , for example, is said to have relied on the Acta Diurna for information about the dates and place of various births, deaths, and other important events. News form the Acta Diurna was also resourced by the Pliny the Elder, who wrote the encyclopaedic Natural History . In his work, Pliny recounted a story he read in the notices, which was about a faithful dog who followed his dead master’s body into the river at the funeral. Tacitus, who wrote The Annals and The Histories , saw the Acta Diurna as not worthy of reporting great historical events, but only good enough for trivial matters. Nevertheless, it is from this writer that we learn about the popularity of these notices, so much so that they were brought to the distant provinces of the empire by couriers.

Pliny the Elder. ( Public Domain )

Pliny the Elder is one of the ancient authors who turned to the Acta Diurna for information.

The publication of the Acta Diurna continued until around 330 AD. As a result of the decision by the Emperor Constantine to move the capital of his empire from Rome to Constantinople, the Acta Diurna came to an end.

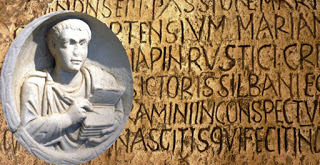

Top image: Relief from a scribe's tomb found in Flavia Solva. ( Public Domain ) Background: Latin stone inscription. ( Public Domain )

By Wu Mingren

Published on December 29, 2017 23:30

Archaeologists in Search of Beer End Up Discovering Valuable Viking Trove

Ancient Origins

A team of archaeologists searching to find beer and other brewing materials, ended up discovering something way more valuable; a trove of amazing Viking artifacts, including an out of place Celtic fitting from a book.

Surprising Discovery Shocks Archaeologists

This was supposed to be another day at work for the team of archaeologists exploring the Byneset Cemetery, adjacent to the medieval Steine Church in Trondheim, Norway. However, they ended up discovering something way more valuable than the beer brewing stones from the Viking Age they were looking for. The team of archaeologists from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology's (NTNU) University Museum discovered a trove of valuable Viking artifacts. “We started the project with slightly lower hopes for what we might find than what's recently emerged,” Museum’s director Reidar Andersen, who was present at the site when the trove was unearthed, said as Phys Org reports.

Jo Sindre Pålsson Eidshaug and Øyunn Wathne Sæther, research assistants at the NTNU University Museum, also expressed their surprise when they discovered the trove during their excavations.

Excavation site was adjacent to the Steine Church, Trondheim, Norway. (Image: Raymond Sauvage, NTNU University Museum.

Viking Trove Includes an “Imported” Irish Object Coincidentally, the director of communications for the museum, Tove Eivindsen, happened to be there at the moment of the discovery and was particularly surprised by a find that appears to be of Irish origin,

“The find is probably a gold-plated, silver fitting from a book. It appears to be Celtic in origin, and might have come from a religious book brought here during the Viking Age that disappeared several centuries ago, and that hasn't been seen by anyone since then – but for now everything is speculation,” he said as Phys Org reports.

Mr. Andersen added, “Someone very politely called this an Irish import, but that's just a nice way of saying that someone was in Ireland and picked up an interesting item."

Raymond Sauvage from NTNU's Department of Archaeology and Cultural History, and the project’s director for these excavations, agreed with Mr. Andersen, as he’s not quite sure if the foreign item ended up being part of the Viking trove in a peaceful manner, “Yes, that's right. We know that the Vikings went out on raids. They went to Ireland and brought things back. But how peacefully it all transpired, I won't venture to say," he said according to Phys Org. He also added that the discovery is really rare and you won’t find it everywhere in Scandinavia, as there are only a few areas where people had the resources to go out on such voyages.

The item which is deemed a "Viking import" from Ireland. Image: NTNU University Museum

Archaeologists, however, used the scientific term for a foreign find as this one and referred to it as an “imported object.” They explained that it doesn’t necessarily mean that it was bought or traded for, taking into consideration, of course, the well-known tactics of the Vikings.

Site Holds Great Promise for the Future

According to the archaeologists the site will probably offer more finds in the near future. The team also unearthed a belt buckle, a key and a knife blade, so they hope now to uncover even more precious artifacts in future digs. As Phys Org reports, the church dates from the 1140s and used to be connected to a large, old farm estate from the time of the Vikings, "Steine Church was built in the 1140s," Sauvage said, explaining that the archaeologists also found a link to Nidaros Cathedral.

Ultimately, Sauvage mentioned that the archaeological mission was originally planning to do a sampling of layers containing brewing stones, but the site proved to hide below way more significant and valuable items than they believed before the excavation works began. For that reason the dig was significantly expanded, and now artifacts dating as far back as 700 AD have been unearthed. The excavation works were funded by Trondheim’s municipality and lasted for five weeks during the summer of 2017, while the cemetery expansion started on 16 October.

Top image: A fitting, probably from a book. The style is typical of Celtic and Irish areas and dates from the 800s. Silver with traces of gilding. Image Credit: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum

By Theodoros Karasavvas

A team of archaeologists searching to find beer and other brewing materials, ended up discovering something way more valuable; a trove of amazing Viking artifacts, including an out of place Celtic fitting from a book.

Surprising Discovery Shocks Archaeologists

This was supposed to be another day at work for the team of archaeologists exploring the Byneset Cemetery, adjacent to the medieval Steine Church in Trondheim, Norway. However, they ended up discovering something way more valuable than the beer brewing stones from the Viking Age they were looking for. The team of archaeologists from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology's (NTNU) University Museum discovered a trove of valuable Viking artifacts. “We started the project with slightly lower hopes for what we might find than what's recently emerged,” Museum’s director Reidar Andersen, who was present at the site when the trove was unearthed, said as Phys Org reports.

Jo Sindre Pålsson Eidshaug and Øyunn Wathne Sæther, research assistants at the NTNU University Museum, also expressed their surprise when they discovered the trove during their excavations.

Excavation site was adjacent to the Steine Church, Trondheim, Norway. (Image: Raymond Sauvage, NTNU University Museum.

Viking Trove Includes an “Imported” Irish Object Coincidentally, the director of communications for the museum, Tove Eivindsen, happened to be there at the moment of the discovery and was particularly surprised by a find that appears to be of Irish origin,

“The find is probably a gold-plated, silver fitting from a book. It appears to be Celtic in origin, and might have come from a religious book brought here during the Viking Age that disappeared several centuries ago, and that hasn't been seen by anyone since then – but for now everything is speculation,” he said as Phys Org reports.

Mr. Andersen added, “Someone very politely called this an Irish import, but that's just a nice way of saying that someone was in Ireland and picked up an interesting item."

Raymond Sauvage from NTNU's Department of Archaeology and Cultural History, and the project’s director for these excavations, agreed with Mr. Andersen, as he’s not quite sure if the foreign item ended up being part of the Viking trove in a peaceful manner, “Yes, that's right. We know that the Vikings went out on raids. They went to Ireland and brought things back. But how peacefully it all transpired, I won't venture to say," he said according to Phys Org. He also added that the discovery is really rare and you won’t find it everywhere in Scandinavia, as there are only a few areas where people had the resources to go out on such voyages.

The item which is deemed a "Viking import" from Ireland. Image: NTNU University Museum

Archaeologists, however, used the scientific term for a foreign find as this one and referred to it as an “imported object.” They explained that it doesn’t necessarily mean that it was bought or traded for, taking into consideration, of course, the well-known tactics of the Vikings.

Site Holds Great Promise for the Future

According to the archaeologists the site will probably offer more finds in the near future. The team also unearthed a belt buckle, a key and a knife blade, so they hope now to uncover even more precious artifacts in future digs. As Phys Org reports, the church dates from the 1140s and used to be connected to a large, old farm estate from the time of the Vikings, "Steine Church was built in the 1140s," Sauvage said, explaining that the archaeologists also found a link to Nidaros Cathedral.

Ultimately, Sauvage mentioned that the archaeological mission was originally planning to do a sampling of layers containing brewing stones, but the site proved to hide below way more significant and valuable items than they believed before the excavation works began. For that reason the dig was significantly expanded, and now artifacts dating as far back as 700 AD have been unearthed. The excavation works were funded by Trondheim’s municipality and lasted for five weeks during the summer of 2017, while the cemetery expansion started on 16 October.

Top image: A fitting, probably from a book. The style is typical of Celtic and Irish areas and dates from the 800s. Silver with traces of gilding. Image Credit: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on December 29, 2017 00:00

December 28, 2017

Ancient Greece – fact or fiction?

History Extra

The famed Washington-based satirising internet newspaper, the Onion, launched a story in early October lifting the lid on the study of the ancient Greek world: it had, in fact, all been made up by the historians. Everything from the Iliad to ancient Greek vases to entire archaeological sites had been faked because, as the Onion puts it, no one really had any idea what happened in the 800 years before the Christian era in Europe.

I have, along with other ancient historian colleagues I'm sure, received several joking emails from academics in other disciplines revelling in the fact that we had been "busted". I was even asked by one tourist traveller in Greece last week if it was true.

No, I can categorically state we didn’t make it all up. But that’s not to say we have not been involved in the way the ancient world’s story has unfolded. Archaeologists have imposed their own views about how ancient buildings should be reconstructed, scholars of the ancient texts have argued for how they think the fragments surviving should be completed and more importantly interpreted. Ancient historians have applied modern models of thought to cast the social, economic and political realities of the ancient world in certain lights. Issues that have occupied our 19th, 20th and 21st-century worlds have become guiding questions for investigation of ancient societies.

Of course the best traditions of scholarship have always worked incredibly hard to ensure the ancient world is allowed to speak for itself, without refraction or alteration through the myriad of lenses with which it is studied and through the layers of societies and historical time that stand between us and them. That search for an ‘objective’ way of studying past human society will always be on-going and I have no doubt that we will continue to get better at it.

But we will never be able to take ourselves entirely out of the equation. Nor should we want to, because it is in that very multiplicity of approaches, views, understandings and ideas that the debate about what the ancient world was like is fired up, and it is through that debate that we gain a better understanding of our humanity and its past.

Reprinted from Neos Kosmos www.neoskosmos.com

Submitted by: Michael Scott

The famed Washington-based satirising internet newspaper, the Onion, launched a story in early October lifting the lid on the study of the ancient Greek world: it had, in fact, all been made up by the historians. Everything from the Iliad to ancient Greek vases to entire archaeological sites had been faked because, as the Onion puts it, no one really had any idea what happened in the 800 years before the Christian era in Europe.

I have, along with other ancient historian colleagues I'm sure, received several joking emails from academics in other disciplines revelling in the fact that we had been "busted". I was even asked by one tourist traveller in Greece last week if it was true.

No, I can categorically state we didn’t make it all up. But that’s not to say we have not been involved in the way the ancient world’s story has unfolded. Archaeologists have imposed their own views about how ancient buildings should be reconstructed, scholars of the ancient texts have argued for how they think the fragments surviving should be completed and more importantly interpreted. Ancient historians have applied modern models of thought to cast the social, economic and political realities of the ancient world in certain lights. Issues that have occupied our 19th, 20th and 21st-century worlds have become guiding questions for investigation of ancient societies.

Of course the best traditions of scholarship have always worked incredibly hard to ensure the ancient world is allowed to speak for itself, without refraction or alteration through the myriad of lenses with which it is studied and through the layers of societies and historical time that stand between us and them. That search for an ‘objective’ way of studying past human society will always be on-going and I have no doubt that we will continue to get better at it.

But we will never be able to take ourselves entirely out of the equation. Nor should we want to, because it is in that very multiplicity of approaches, views, understandings and ideas that the debate about what the ancient world was like is fired up, and it is through that debate that we gain a better understanding of our humanity and its past.

Reprinted from Neos Kosmos www.neoskosmos.com

Submitted by: Michael Scott

Published on December 28, 2017 00:00

December 26, 2017

Student’s Lucky Find Worth £145,000 Is Rewriting Anglo-Saxon History

Ancient Origins

A student in Norfolk probably never imagined that his discovery of a female skeleton wearing a pendant could rewrite Anglo Saxon history – but researchers say that the “exquisite” gold piece is doing just that.

According to The Telegraph , “The find of the female skeleton wearing a pendant of gold imported from Sri Lanka and coins bearing the marks of a continental king is prompting a fundamental reassessment of the seats of power in Anglo Saxon England.”

Altogether, the artifacts have become known as the treasure of the Winfarthing Woman. An analysis of the grave goods, namely two inscribed coins, suggests that the grave’s owner was buried between 650 to 675 AD and was an elite member of society, possibly even royalty.

One of the large gold pendants found on the skeleton is inlaid with hundreds of tiny garnets. That artifact alone has been valued at £145,000 (almost $190,000). A delicate gold filigree cross found in the burial suggests that the woman may have been one of the earliest Anglo Saxon converts to Christianity. Other items found in the grave included two identical Merovingian gold coins which had been made into pendants, and two gold beads. Senior Curator of the Norwich Castle Museum Dr. Tim Pestell said the craftsmanship of these objects is “equal” to the famous Staffordshire Hoard.

The Anglo-Saxon pendant found at the rich grave in Winfarthing, Norfolk. ( The British Museum )

In an amusing turn of events, the discovery was made at a site which has been overlooked by archaeologists over the years due to the poor soil. But Thomas Lucking, who found the site in 2015 decided that the location was worth an examination. “We could hear this large signal. We knew there was something large but couldn't predict it would be like that,” he said, “When it came out the atmosphere changed.”

The Guardian reports the first artifact unearthed was a bronze bowl placed at the feet of the skeleton, when the human remains were noted Lucking paused the dig to call the county archaeology unit in.

Excavating the Anglo-Saxon grave in Winfarthing, Norfolk. ( John Rainer )

Work continues at the site first identified by Lucking as it has been identified as a cemetery, possibly with a settlement located nearby as well. Mr. Lucking now works as a full-time archaeologist.

The Daily Mail notes that Mr. Lucking’s discovery in 2016 is one of the highlights from a record year for public discoveries of ancient treasures. 1,120 treasures were found that year, making the highest figure for 20 years. Two other interesting discoveries described at the launch of the Portable Antiquities Scheme and Treasure annual reports at the British Museum include two Bronze Age hoards and a Roman coin collection. One of the Bronze Age hoards consisted of 158 axes and ingots while the other consisted of 27 axes and ingots. Both were found in Driffield, East Yorkshire and date to around 950-850 BC. The Roman coins numbered more than 2,000 and were discovered inside a pottery vessel in Piddletrenthide, Dorset.

Some of the artifacts found in the Driffield hoard. ( British Museum )

Top Image: The gold pendant found in the soil. Source: John Fulcher

By Alicia McDermott

Published on December 26, 2017 23:00

A brief history of Boxing Day

History Extra

Q: So what exactly is Boxing Day?

A: Boxing Day is also known as St Stephen's Day – Stephen was the first Christian martyr, stoned to death in c34 AD.

Being a saint’s day, it has charitable associations. Charitable boxes – collections of money – would have been given out at the church door to the needy.

While the wider significance of St Stephen’s Day collapsed in Europe, it held on in Protestant England. It is an Anglo-Saxon thing. As England made more and more of a thing about Christmas, it began to concentrate its rituals onto just a few days. This was happening by the 18th century.

The English came to believe that they owned Christmas – perhaps in partnership with other ‘Teutonic/Nordic’ peoples. This was a bit of an over-exaggeration as, of course, there are plenty of southern European Christmas traditions.

The Church of England had gotten rid of so many days. The charitable efforts that, under the Catholic calendar, would have been scattered, became tied to the one day.

By the late 18th century or early 19th century, Boxing Day became a day of outdoor activity.

While Christmas Day was about being at home with your family, Boxing Day was a time to get outside, to get away from the home. People can only be cooped up for so long! There’s a need to exorcise – and exercise – all of that.

In the 18th century, Boxing Day became a day for aristocratic sports – hunting, horseracing, shooting. By the 19th century, as a result of urbanisation, it was about professional football.

As British society, particularly English society, became marked by large industrial cities, distinctive working class leisure pursuits evolved. With Boxing Day already associated with pleasurable, outdoor activities, it was soon adopted as a key date in the professional soccer calendar.

Q: When did the charitable side of Boxing Day end?

A: By the early 19th century, charitable aims became more focused around Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, but it was a very slow petering out. There was a debate about whether inmates should get beer and beef on Christmas Day, for example.

Whether they got this depended upon the attitude of local guardians.

And by this point, there were enough poor people to be thought of as an entity. Provision for the poor turned into a local government issue, as opposed to something individuals organised.

Mason/Associated Newspapers)

Q: So when did Boxing Day originate?

A: Boxing Day emerged quite quickly after the establishment of Christmas. The very early church took no notice of Christmas – it wasn’t until the turn of the first millennia that the church started to push Christmas.

It was a way to make sure converts stayed on board – the early church knew it could not stamp out all the winter festivals, so it decided to ‘Christianise’ them. So a whole series of pre-existing European mid-winter ceremonies were white-washed with Christianity.

Boxing Day came quickly after.

Christmas feast days were chipped away at – largely because of Protestantism and the development of the British economy. A more urbanised, factory-oriented economy meant that the machines and methods of production just had to be kept going.

It was completely unlike the rhythms of the rural world which had dominated, and which allowed for more punctuation marks in the course of the year – so you ended up having to peg festivities on fewer days.

Q: Historically, has Boxing Day been celebrated differently in other parts of the world?

A: England, Wales, Australia and New Zealand are distinctive in making quite a thing of Boxing Day, with outdoor events such as picnics, horse shows, rides and walks.

Q: How did Boxing Day become a bank holiday?

A: The 26th of December became additional bank holiday in 1974, but in fact it had been a de facto day off for many years. This is partly because football made such a big thing of Boxing Day that many took time off anyway, and gradually during the course of the 20th century more and more employers realised that business was generally slow during this period and so, in effect, turned a blind eye to people taking the time off, which then became a custom in its own right.

Q: Boxing Day today tends to be associated with shopping. When did this trend emerge?

A: It began in the late 1990s, when the John Major government amended Sunday trading laws.

When you open the door to trading on a Sunday, changing the spirit of when it is morally ‘right’ to shop, you open up trading on festival days.

By Mark Connelly, professor of modern British history at the University of Kent.

Q: So what exactly is Boxing Day?

A: Boxing Day is also known as St Stephen's Day – Stephen was the first Christian martyr, stoned to death in c34 AD.

Being a saint’s day, it has charitable associations. Charitable boxes – collections of money – would have been given out at the church door to the needy.

While the wider significance of St Stephen’s Day collapsed in Europe, it held on in Protestant England. It is an Anglo-Saxon thing. As England made more and more of a thing about Christmas, it began to concentrate its rituals onto just a few days. This was happening by the 18th century.

The English came to believe that they owned Christmas – perhaps in partnership with other ‘Teutonic/Nordic’ peoples. This was a bit of an over-exaggeration as, of course, there are plenty of southern European Christmas traditions.

The Church of England had gotten rid of so many days. The charitable efforts that, under the Catholic calendar, would have been scattered, became tied to the one day.

By the late 18th century or early 19th century, Boxing Day became a day of outdoor activity.

While Christmas Day was about being at home with your family, Boxing Day was a time to get outside, to get away from the home. People can only be cooped up for so long! There’s a need to exorcise – and exercise – all of that.

In the 18th century, Boxing Day became a day for aristocratic sports – hunting, horseracing, shooting. By the 19th century, as a result of urbanisation, it was about professional football.

As British society, particularly English society, became marked by large industrial cities, distinctive working class leisure pursuits evolved. With Boxing Day already associated with pleasurable, outdoor activities, it was soon adopted as a key date in the professional soccer calendar.

Q: When did the charitable side of Boxing Day end?

A: By the early 19th century, charitable aims became more focused around Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, but it was a very slow petering out. There was a debate about whether inmates should get beer and beef on Christmas Day, for example.

Whether they got this depended upon the attitude of local guardians.

And by this point, there were enough poor people to be thought of as an entity. Provision for the poor turned into a local government issue, as opposed to something individuals organised.

Mason/Associated Newspapers)

Q: So when did Boxing Day originate?

A: Boxing Day emerged quite quickly after the establishment of Christmas. The very early church took no notice of Christmas – it wasn’t until the turn of the first millennia that the church started to push Christmas.

It was a way to make sure converts stayed on board – the early church knew it could not stamp out all the winter festivals, so it decided to ‘Christianise’ them. So a whole series of pre-existing European mid-winter ceremonies were white-washed with Christianity.

Boxing Day came quickly after.

Christmas feast days were chipped away at – largely because of Protestantism and the development of the British economy. A more urbanised, factory-oriented economy meant that the machines and methods of production just had to be kept going.

It was completely unlike the rhythms of the rural world which had dominated, and which allowed for more punctuation marks in the course of the year – so you ended up having to peg festivities on fewer days.

Q: Historically, has Boxing Day been celebrated differently in other parts of the world?

A: England, Wales, Australia and New Zealand are distinctive in making quite a thing of Boxing Day, with outdoor events such as picnics, horse shows, rides and walks.

Q: How did Boxing Day become a bank holiday?

A: The 26th of December became additional bank holiday in 1974, but in fact it had been a de facto day off for many years. This is partly because football made such a big thing of Boxing Day that many took time off anyway, and gradually during the course of the 20th century more and more employers realised that business was generally slow during this period and so, in effect, turned a blind eye to people taking the time off, which then became a custom in its own right.

Q: Boxing Day today tends to be associated with shopping. When did this trend emerge?

A: It began in the late 1990s, when the John Major government amended Sunday trading laws.

When you open the door to trading on a Sunday, changing the spirit of when it is morally ‘right’ to shop, you open up trading on festival days.

By Mark Connelly, professor of modern British history at the University of Kent.

Published on December 26, 2017 00:00

December 24, 2017

Christmas celebrations: the old versus the new

History Extra

Christmas is, notoriously, a time for nostalgia and for many ‘Christmas present’ is considered never to be quite the same as ‘Christmas past’. This is partly due to our getting older, but is also because there are layers of tradition in our celebrations, some of them pre-Christian, which draw us inevitably to the ‘Old Christmas’. As Charles Dickens wrote, ‘How many old recollections and sympathies does Christmas time awaken’?

Christmas is still essentially that which was remodelled in the 19th century to suit the tastes and ideals of the time. Victorian festivities were centred on the home, the family and the indulgence of children and if, in many homes, the hearth or fireside has disappeared and computer games have replaced the railway set as presents, this is still the Christmas we attempt to recapture and regard as traditional.

The trappings of this festival reflect Victorian innovations: the cards, the tree, the crackers, the family meal with a turkey and, of course, Father Christmas or Santa Claus. Yet an older Christmas hovers behind it and its image is fixed on numerous cards and illustrations depicting a world of stagecoaches, ruddy-faced landlords, thatched cottages, manor houses and hospitable squires. The Victorians built into their new Christmas nostalgia for an ideal Christmas located forever in the 18th-century countryside.

Those very architects of the Victorian Christmas, Charles Dickens and Washington Irving looked back to an idealised Christmas of their recent past. To Dickens, Christmas epitomised not only conviviality and humanity, but an affection for the past. In Pickwick Papers he describes a merry old Christmas, a “good humoured Christmas” in which, after blind-man’s buff, “there was a great game at snap-dragon, and when fingers enough were burned with that, and all the raisons were gone, they sat down by the huge fire of blazing logs to substantial supper, and a mighty bowl of wassail”.

Dickens may well have helped create a new Christmas but at the heart of his vision was an idealised old Christmas; one he hoped to revive. This Christmas was a merry, lengthy and mainly adult affair with some relaxation of the normal rules of propriety.

Whether the occasion was generally observed has been doubted by some, as there is evidence that Christmas was in decline during the late 18th century. The puritans of the Commonwealth, who considered it a Popish survival, attempted to abolish the festival, but the Restoration saw it reinstated amidst popular acclaim. However, forms of celebration based on the open-handed hospitality of the aristocrat or squire in the big house and the often drunken and bawdy customs of the country people, were coming to seem quaint and old-fashioned to many.

Such celebrations had little appeal for the well-to-do in towns and, in the countryside, the gentry no longer automatically kept open house for their dependents, while up-and-coming farmers, distanced themselves from their workers and the mumming and licence of the ‘world-turned-upside-down’ that was the ‘Old Christmas’. Only in more backward areas was Christmas celebrated in the old style and The Times reflected in 1790 on the time of festivity having “lost much of its original mirth and hospitality”.

It was the very decay of Christmas traditions and a consciousness of their passing that appealed to romantics and antiquarians. The American writer, Washington Irving, visiting England in the early 19th century, saw the ‘Old Christmas’ as resembling “those picturesque morsels of Gothic architecture which we see crumbling in various parts of the country, partly dilapidated by the waste of ages, and partly lost in the additions and alterations of later days”. His account of the ‘Old Christmas’ presided over by the antiquarian Squire Bracebridge at Bracebridge Hall was an imaginative reconstruction of old customs and traditions, rather than a description of a contemporary Christmas.

It wasn’t, however, solely the antique and antic customs of the decaying ‘Old Christmas’ that appealed to Dickens and Irving, but the underlying social harmony that they perceived in it. The ‘New Christmas’ that Dickens helped to create was essentially a private and family affair, even if Victorian families were large, and one that centred on children. The ‘Old Christmas’, whose passing he regretted, had been more of a community festival; an expression in the idle period of the agricultural year of charity in its older sense of fellowship.

Much has been made of the contrast between Christmas at Dingley Dell in Pickwick Papers, a gregarious and merry festival lasting twelve days, and A Christmas Carol where the emphasis is upon Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, as well as the notion of the family, represented by the Cratchits. This difference can be exaggerated for, if Dickens was Victorian enough to put home and hearth at the centre of things, his main aim was to stress fellowship, empathy between different sections of society, the responsibility of employers and good cheer. Mr Fessiwig’s Ball, held by the employer for all who worked for him, looks back to the festivities in the manor or farm house in which villagers or retainers, as well as family, participated and forward to the office party. Social harmony was the vision he saw Christmas representing and, if the half-imaginary 18th-century Christmas he drew on was a rosy image of pre-industrial society, it was ever-present in his works.

The third ghost to visit Scrooge is the Ghost of Christmas Present who in fact bears a strong resemblance to some of the more jovial depictions of the spirit of the ‘Old Christmas’ – “a jolly Giant, glorious to see” who, “in a green robe, or mantle bordered with white fur”, is surrounded by a display of plenty in the shape of turkeys, geese and ‘seething bowls of punch’. This spirit, a prototype Father Christmas and a kindly if rather pagan figure, continued to hover over the Christmas that Dickens helped refashion.

The Dickensian Christmas is, therefore, a bridge between the old and the new Christmas, the Anglo-American Christmas, which we inherit. The latter is, no doubt, better suited to an urban and mobile society; it is centred upon the family and children and is essentially private and home-based amidst eerily empty streets. It is also rather tamed for, if we eat and drink enough, it lacks the boisterousness and wider conviviality of the older, more adult, Christmas.

Yet, that ‘Old Christmas’ is annually invoked today, as it was in the 19th century, by Christmas cards and festive illustrations in which jovial squires forever entertain friends by roaring fires while stout coachmen swathed in greatcoats, urge horses down snow covered lanes as they bring anticipatory guests and homesick relations to their welcoming destinations in a dream of merry England.

Professor Arthur Purdue is visiting senior lecturer in history at the Open University and co-author with JM Golby of The Making of the Modern Christmas, Batsford (1986).

Christmas is, notoriously, a time for nostalgia and for many ‘Christmas present’ is considered never to be quite the same as ‘Christmas past’. This is partly due to our getting older, but is also because there are layers of tradition in our celebrations, some of them pre-Christian, which draw us inevitably to the ‘Old Christmas’. As Charles Dickens wrote, ‘How many old recollections and sympathies does Christmas time awaken’?

Christmas is still essentially that which was remodelled in the 19th century to suit the tastes and ideals of the time. Victorian festivities were centred on the home, the family and the indulgence of children and if, in many homes, the hearth or fireside has disappeared and computer games have replaced the railway set as presents, this is still the Christmas we attempt to recapture and regard as traditional.

The trappings of this festival reflect Victorian innovations: the cards, the tree, the crackers, the family meal with a turkey and, of course, Father Christmas or Santa Claus. Yet an older Christmas hovers behind it and its image is fixed on numerous cards and illustrations depicting a world of stagecoaches, ruddy-faced landlords, thatched cottages, manor houses and hospitable squires. The Victorians built into their new Christmas nostalgia for an ideal Christmas located forever in the 18th-century countryside.

Those very architects of the Victorian Christmas, Charles Dickens and Washington Irving looked back to an idealised Christmas of their recent past. To Dickens, Christmas epitomised not only conviviality and humanity, but an affection for the past. In Pickwick Papers he describes a merry old Christmas, a “good humoured Christmas” in which, after blind-man’s buff, “there was a great game at snap-dragon, and when fingers enough were burned with that, and all the raisons were gone, they sat down by the huge fire of blazing logs to substantial supper, and a mighty bowl of wassail”.

Dickens may well have helped create a new Christmas but at the heart of his vision was an idealised old Christmas; one he hoped to revive. This Christmas was a merry, lengthy and mainly adult affair with some relaxation of the normal rules of propriety.

Whether the occasion was generally observed has been doubted by some, as there is evidence that Christmas was in decline during the late 18th century. The puritans of the Commonwealth, who considered it a Popish survival, attempted to abolish the festival, but the Restoration saw it reinstated amidst popular acclaim. However, forms of celebration based on the open-handed hospitality of the aristocrat or squire in the big house and the often drunken and bawdy customs of the country people, were coming to seem quaint and old-fashioned to many.

Such celebrations had little appeal for the well-to-do in towns and, in the countryside, the gentry no longer automatically kept open house for their dependents, while up-and-coming farmers, distanced themselves from their workers and the mumming and licence of the ‘world-turned-upside-down’ that was the ‘Old Christmas’. Only in more backward areas was Christmas celebrated in the old style and The Times reflected in 1790 on the time of festivity having “lost much of its original mirth and hospitality”.

It was the very decay of Christmas traditions and a consciousness of their passing that appealed to romantics and antiquarians. The American writer, Washington Irving, visiting England in the early 19th century, saw the ‘Old Christmas’ as resembling “those picturesque morsels of Gothic architecture which we see crumbling in various parts of the country, partly dilapidated by the waste of ages, and partly lost in the additions and alterations of later days”. His account of the ‘Old Christmas’ presided over by the antiquarian Squire Bracebridge at Bracebridge Hall was an imaginative reconstruction of old customs and traditions, rather than a description of a contemporary Christmas.

It wasn’t, however, solely the antique and antic customs of the decaying ‘Old Christmas’ that appealed to Dickens and Irving, but the underlying social harmony that they perceived in it. The ‘New Christmas’ that Dickens helped to create was essentially a private and family affair, even if Victorian families were large, and one that centred on children. The ‘Old Christmas’, whose passing he regretted, had been more of a community festival; an expression in the idle period of the agricultural year of charity in its older sense of fellowship.

Much has been made of the contrast between Christmas at Dingley Dell in Pickwick Papers, a gregarious and merry festival lasting twelve days, and A Christmas Carol where the emphasis is upon Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, as well as the notion of the family, represented by the Cratchits. This difference can be exaggerated for, if Dickens was Victorian enough to put home and hearth at the centre of things, his main aim was to stress fellowship, empathy between different sections of society, the responsibility of employers and good cheer. Mr Fessiwig’s Ball, held by the employer for all who worked for him, looks back to the festivities in the manor or farm house in which villagers or retainers, as well as family, participated and forward to the office party. Social harmony was the vision he saw Christmas representing and, if the half-imaginary 18th-century Christmas he drew on was a rosy image of pre-industrial society, it was ever-present in his works.

The third ghost to visit Scrooge is the Ghost of Christmas Present who in fact bears a strong resemblance to some of the more jovial depictions of the spirit of the ‘Old Christmas’ – “a jolly Giant, glorious to see” who, “in a green robe, or mantle bordered with white fur”, is surrounded by a display of plenty in the shape of turkeys, geese and ‘seething bowls of punch’. This spirit, a prototype Father Christmas and a kindly if rather pagan figure, continued to hover over the Christmas that Dickens helped refashion.

The Dickensian Christmas is, therefore, a bridge between the old and the new Christmas, the Anglo-American Christmas, which we inherit. The latter is, no doubt, better suited to an urban and mobile society; it is centred upon the family and children and is essentially private and home-based amidst eerily empty streets. It is also rather tamed for, if we eat and drink enough, it lacks the boisterousness and wider conviviality of the older, more adult, Christmas.

Yet, that ‘Old Christmas’ is annually invoked today, as it was in the 19th century, by Christmas cards and festive illustrations in which jovial squires forever entertain friends by roaring fires while stout coachmen swathed in greatcoats, urge horses down snow covered lanes as they bring anticipatory guests and homesick relations to their welcoming destinations in a dream of merry England.

Professor Arthur Purdue is visiting senior lecturer in history at the Open University and co-author with JM Golby of The Making of the Modern Christmas, Batsford (1986).

Published on December 24, 2017 23:30

The History of... Christmas crackers

History Extra

Who do we have to thank for the Christmas cracker?

Traditionally the credit goes to london confectioner Tom Smith. In 1847 he is said to have introduced England to the delights of the French bonbon, a sugar-almond wrapped in paper with a twist at both ends. To boost sales and keep ahead of his competitors, Smith added a ‘love motto’ before enlarging the packaging, replacing the bonbon with a gift and, in 1860, adding the exploding ‘crack’ that was to give the cracker its name. His son, Walter, later introduced the now-obligatory paper hat.

Yet it’s possible that the first person to sell crackers in Britain was in fact the Italian-born gaudente Sparagnapane, another London confectioner (and the father of noted suffragette maud Sennett). His company, which was established in 1846, a year before Smith’s, described itself as “the oldest makers of Christmas crackers in the United Kingdom”.

Were crackers always called crackers?

No. Both companies initially called their creations ‘Cosaques’, supposedly because the crack they made when pulled were reminiscent of the cracking whips of Russian Cossack horsemen.

What’s the story behind the introduction of the ‘crack’?

Tradition has it that Smith was inspired by the cracking of a log on his fire. Some accounts even claim he spent two years trying to perfect a way of making the sound. However silver fulminate ‘snaps’ had been around for decades and it’s more likely that Smith merely found a new use for an existing novelty.

And they’re not just for Christmas?

Not at all. Late 19th and early 20th-century manufacturers in particular kept a close eye on current affairs and produced crackers with a variety of themes. Votes for women, Charlie Chaplin, coronations, the wireless, even the battle of Tel el Kebir (in the Anglo-Egyptian War of 1882) were just some of the subjects to get the cracker treatment.

Were the mottoes and jokes always so awful?

Smith’s certainly didn’t think so. They were proud of the quality of the verse in their early mottoes. But by 1906 the efforts of some manufacturers were certainly bad enough for the Westminster Gazette to describe a particularly poorly written play as being “not up to the standard of cracker poetry”.

By Julian Humphrys

Published on December 24, 2017 00:00