MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 30

February 15, 2018

What is gaol fever and how was it caused and spread?

History Extra

Gaol fever is epidemic typhus (not typhoid), and can be prevented by vaccination...

Patients can be successfully treated with antibiotics, but it was once a major killer. The first scientifically reliable accounts of the disease come from 15th-century Europe, though it has probably been around much longer.

Symptoms include severe headache and muscle pain, fever, delirium and a characteristic rash. Several major outbreaks described as ‘plagues’ by chroniclers were, in fact, typhus.

The cause of epidemic typhus is Rickettsia prowazekii, bacteria usually transmitted by body lice. It thrives in overcrowded places where sanitation is poor and immune systems are weakened by hunger. Outbreaks were common in armies well into the 20th century, and it often killed more soldiers than combat, as in Napoleon’s 1812 retreat from Moscow. The last outbreaks of gaol fever to kill significant numbers of Europeans were in Hitler’s concentration camps.

It commonly occurred in the appalling conditions of Britain’s prisons before Victorian reformers cleaned them up, hence the name ‘gaol fever’. Being held in prison before trial could be tantamount to a sentence of death, and more died of goal fever in the 1700s than were executed. In a particularly notorious case, prisoners from Ilchester gaol brought to Taunton assizes in 1730 caused an outbreak that killed the judge, several court officials and hundreds of others.

Answered by Eugene Byrne, author and journalist.

Gaol fever is epidemic typhus (not typhoid), and can be prevented by vaccination...

Patients can be successfully treated with antibiotics, but it was once a major killer. The first scientifically reliable accounts of the disease come from 15th-century Europe, though it has probably been around much longer.

Symptoms include severe headache and muscle pain, fever, delirium and a characteristic rash. Several major outbreaks described as ‘plagues’ by chroniclers were, in fact, typhus.

The cause of epidemic typhus is Rickettsia prowazekii, bacteria usually transmitted by body lice. It thrives in overcrowded places where sanitation is poor and immune systems are weakened by hunger. Outbreaks were common in armies well into the 20th century, and it often killed more soldiers than combat, as in Napoleon’s 1812 retreat from Moscow. The last outbreaks of gaol fever to kill significant numbers of Europeans were in Hitler’s concentration camps.

It commonly occurred in the appalling conditions of Britain’s prisons before Victorian reformers cleaned them up, hence the name ‘gaol fever’. Being held in prison before trial could be tantamount to a sentence of death, and more died of goal fever in the 1700s than were executed. In a particularly notorious case, prisoners from Ilchester gaol brought to Taunton assizes in 1730 caused an outbreak that killed the judge, several court officials and hundreds of others.

Answered by Eugene Byrne, author and journalist.

Published on February 15, 2018 23:30

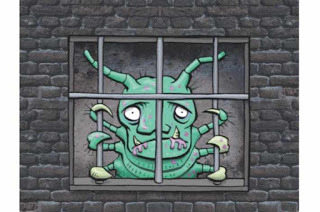

Prehistoric treasures featured on latest Royal Mail stamps

History Extra

Royal Mail has released eight stamps featuring objects and sites of British prehistory, celebrating Britain's “incredibly rich heritage of prehistoric sites and exceptional artefacts”

A number of sites and treasures of prehistoric Britain have been featured in a new set of eight stamps from Royal Mail. Sites included on the stamps are Skara Brae village, where fierce storms in 1850 stripped away sand dunes on Orkney’s west coast to reveal traces of Neolithic stone-walled houses, and Avebury stone circles, Britain’s largest prehistoric ceremonial monument.

Illustrated by London-based artist Rebecca Strickson, the stamps have been designed as overlay illustrations, detailing how people lived and worked at these sites and used the objects. Strickson said: “This period in time has long been a fascination to me, and stamp collecting was something my late father adored in his youth. That these stamps are coming out on what would have been his 68th birthday makes me really smile.”

Philip Parker explained that the collection aims to “explore some of these treasures and give us a glimpse of everyday life in prehistoric Great Britain and Northern Ireland, from the culture of ancient ritual and music making to sophisticated metalworking and the building of huge hill forts”.

For each of the stamps, Royal Mail will provide a special postmark on all mail posted in a postbox close to where the site is located or the artefact found. It will be applied for five days from 17-21 January 2017, and stamps are available from 17 January 2017, at 7,000 Post Office branches across the UK and at www.royalmail.com/ancientbritain.

Published on February 15, 2018 00:00

February 14, 2018

Book Launch - Planetary Wars: Rise of an Empire by Mary Ann Bernal now available

Caught up in a whirlwind romance, Anastasia Dennison, M.D., does not realize her husband is the terrifying dictator, Jayden Henry Shaw, who rules the galaxy with an iron fist while pretending to defend the vulnerable against the Imperial Forces of the Empire.

Denying the existence of widespread suffering, Anastasia ignores her principles as she embraces the spoils of war and takes her rightful place among the upper echelon of Terrenean society.

Will Anastasia continue to support her husband’s quest for complete domination of every world within the cosmos, or will she follow her conscience and fight the evil invading her home?

Purchase links

Amazon US

Amazon UK

Smashwords

iTunes

Published on February 14, 2018 01:00

February 13, 2018

Some Top Tips for Valentine’s Day … from Medieval Lovers

Ancient Origins

If you’d asked someone to be your Valentine before the 14th century, they’d probably have looked at you as if you were mad. And checked you weren’t holding an axe.

There were two saints by the name of Valentine who were venerated on February 14 during the Middle Ages. Both Valentines were supposedly Christian priests who fell foul of Roman officials keen on decapitation. But there’s little in the early legends of either saint to suggest a highly successful posthumous career as assistant Cupid. So I wouldn’t go to them for tips.

It was probably Geoffrey Chaucer who got the Valentine’s ball rolling. In his Parliament of Fowls, Chaucer imagined the goddess Nature pairing off all the birds for the year to come on “Seint Valentynes day”

. First up is the queenly eagle. She’s wooed at great length by noble birds-of-prey, much to the annoyance of the ducks and cuckoos and other low-ranking birds (eager to get on with getting it on):

‘Come on!’ they cried, ‘Alas, you us offend! When will your cursed pleading have an end?’

But why on earth did Chaucer pick a date in February for his avian assembly? England’s birds aren’t exactly in full voice at this time of year, even with global warming. Perhaps he was thinking of an obscure St Valentine celebrated in Genoa in the month of May. But the Valentines fêted on February 14 were better-known, and that was the date that stuck. Of course, when it comes to matters of the heart, we can hardly expect reason to triumph.

Fiction to fact

Murky origins didn’t matter for too long, however. By the turn of the 15th century, fictional lovebirds weren’t the only ones singing their hearts out on Valentine’s day.

According to its founding charter, a society known as the “Court of Love” was set up in France in 1400 as a distraction from a particularly nasty bout of plague. This curious document stipulates that every February 14: “when the little birds resume their sweet song” (sure about that, guys?), members should meet in Paris for a splendid supper. Male guests were to bring a love song of their own composition, to be judged by an all-female panel. More effort than Tinder demands, then. But if you want to make an effort…

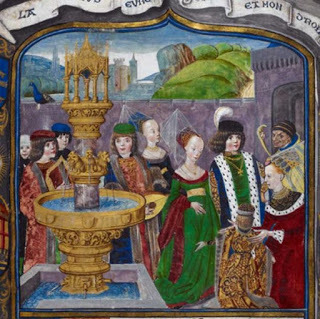

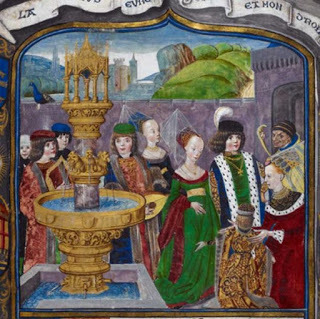

Detail of a 15th-century miniature depicting an allegorical court of love (Royal 16 F II, f. 1) British Library

There’s no evidence that the Court of Love convened as often as planned (its charter provided for monthly meetings in addition to February 14 festivities). But nor does it seem to have been pure poetic fiction. Eventually totalling 950 or so, participants represented quite a cross-section of society, from the king of France to the petite bourgeoisie. Valentine’s day romance was no longer just for the eagles.

Today’s February 14 love-fest, then, is perhaps the result of a group of medieval men and women making life imitate art. If so, their mimicry wasn’t necessarily naïve. By staging the most poetic of avian courtship rituals, Chaucer’s Parliament of Fowls prompts its audiences to ponder the differences between their “artistic” courtship and the birds’ “natural” one. Texts like this one helped medieval audiences understand their identities as the product of cultural artefacts. And in this regard they can still help us today.

Four medieval tips

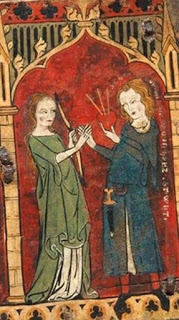

On this 14th-century coffret, a man surrenders his heart to Lady Love. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (www.metmuseum.org)

On a more practical note, medieval literature can be of assistance if you’re yet to find a gift for a special someone this Valentine’s day. Forget about flashy jewellery; here are some love tokens suitable for every budget:

Looking to reignite that spark in your relationship? In his 12th-century Art of Courtly Love Andreas Capellanus suggests buying your partner a washbasin. Who needs expensive perfume when a good wash may do the trick?

How about personalising some of your beloved’s clothes? Add fasteners only you know how to undo and you’ve got yourself an instant chastity belt. (See the 12th-century tales by Marie de France for examples of suitable garments.)

Alternatively, upcycle one of your lover’s old shirts by sewing strands of your hair into it. To judge by Alexander’s reaction in the 12th-century romance of Cligés by Chrétien de Troyes, they’ll never want to wear anything else. (Hand-wash only.)

And if the above just don’t seem heartfelt enough, you could always take a leaf out of Le Chastelain de Couci’s book, who (according to his 13th-century biography) literally gave his heart to his lover. (Beware unwanted side effects.)

Top tip: provide a little literary and historical context with the above gifts and there’s even a chance your Valentine won’t look at you as if you’re holding an axe.

The article ‘Some top tips for Valentine’s day … from Medieval lovers’ by Huw Grange was originally published on The Conversation and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

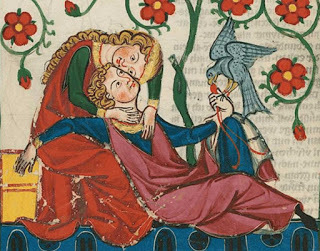

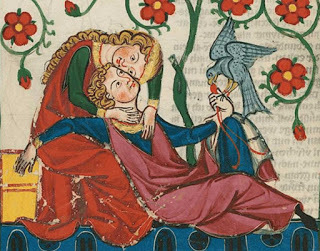

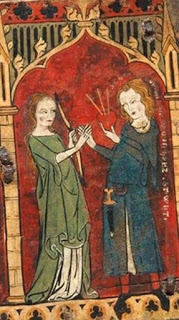

Top image: Lovebirds in the 14th-century Codex Manesse (Cod. Pal. germ. 848, f. 249v).

If you’d asked someone to be your Valentine before the 14th century, they’d probably have looked at you as if you were mad. And checked you weren’t holding an axe.

There were two saints by the name of Valentine who were venerated on February 14 during the Middle Ages. Both Valentines were supposedly Christian priests who fell foul of Roman officials keen on decapitation. But there’s little in the early legends of either saint to suggest a highly successful posthumous career as assistant Cupid. So I wouldn’t go to them for tips.

It was probably Geoffrey Chaucer who got the Valentine’s ball rolling. In his Parliament of Fowls, Chaucer imagined the goddess Nature pairing off all the birds for the year to come on “Seint Valentynes day”

. First up is the queenly eagle. She’s wooed at great length by noble birds-of-prey, much to the annoyance of the ducks and cuckoos and other low-ranking birds (eager to get on with getting it on):

‘Come on!’ they cried, ‘Alas, you us offend! When will your cursed pleading have an end?’

But why on earth did Chaucer pick a date in February for his avian assembly? England’s birds aren’t exactly in full voice at this time of year, even with global warming. Perhaps he was thinking of an obscure St Valentine celebrated in Genoa in the month of May. But the Valentines fêted on February 14 were better-known, and that was the date that stuck. Of course, when it comes to matters of the heart, we can hardly expect reason to triumph.

Fiction to fact

Murky origins didn’t matter for too long, however. By the turn of the 15th century, fictional lovebirds weren’t the only ones singing their hearts out on Valentine’s day.

According to its founding charter, a society known as the “Court of Love” was set up in France in 1400 as a distraction from a particularly nasty bout of plague. This curious document stipulates that every February 14: “when the little birds resume their sweet song” (sure about that, guys?), members should meet in Paris for a splendid supper. Male guests were to bring a love song of their own composition, to be judged by an all-female panel. More effort than Tinder demands, then. But if you want to make an effort…

Detail of a 15th-century miniature depicting an allegorical court of love (Royal 16 F II, f. 1) British Library

There’s no evidence that the Court of Love convened as often as planned (its charter provided for monthly meetings in addition to February 14 festivities). But nor does it seem to have been pure poetic fiction. Eventually totalling 950 or so, participants represented quite a cross-section of society, from the king of France to the petite bourgeoisie. Valentine’s day romance was no longer just for the eagles.

Today’s February 14 love-fest, then, is perhaps the result of a group of medieval men and women making life imitate art. If so, their mimicry wasn’t necessarily naïve. By staging the most poetic of avian courtship rituals, Chaucer’s Parliament of Fowls prompts its audiences to ponder the differences between their “artistic” courtship and the birds’ “natural” one. Texts like this one helped medieval audiences understand their identities as the product of cultural artefacts. And in this regard they can still help us today.

Four medieval tips

On this 14th-century coffret, a man surrenders his heart to Lady Love. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (www.metmuseum.org)

On a more practical note, medieval literature can be of assistance if you’re yet to find a gift for a special someone this Valentine’s day. Forget about flashy jewellery; here are some love tokens suitable for every budget:

Looking to reignite that spark in your relationship? In his 12th-century Art of Courtly Love Andreas Capellanus suggests buying your partner a washbasin. Who needs expensive perfume when a good wash may do the trick?

How about personalising some of your beloved’s clothes? Add fasteners only you know how to undo and you’ve got yourself an instant chastity belt. (See the 12th-century tales by Marie de France for examples of suitable garments.)

Alternatively, upcycle one of your lover’s old shirts by sewing strands of your hair into it. To judge by Alexander’s reaction in the 12th-century romance of Cligés by Chrétien de Troyes, they’ll never want to wear anything else. (Hand-wash only.)

And if the above just don’t seem heartfelt enough, you could always take a leaf out of Le Chastelain de Couci’s book, who (according to his 13th-century biography) literally gave his heart to his lover. (Beware unwanted side effects.)

Top tip: provide a little literary and historical context with the above gifts and there’s even a chance your Valentine won’t look at you as if you’re holding an axe.

The article ‘Some top tips for Valentine’s day … from Medieval lovers’ by Huw Grange was originally published on The Conversation and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Top image: Lovebirds in the 14th-century Codex Manesse (Cod. Pal. germ. 848, f. 249v).

Published on February 13, 2018 23:30

February 12, 2018

Who was the last Groom of the Stool?

History Extra

In English royalty, the Groom of the Stool was originally a servant who assisted the king with bodily functions and washing. The stool in question was a ‘close stool’ – a fixed or portable commode – and help was needed with the putting on and taking off of elaborate and expensive clothing.

Under the Tudors, Grooms of the Stool were important functionaries because of this intimate access. All of Henry VIII’s grooms were knights. Sir Henry Norris, for instance, was closely aligned to Anne Boleyn’s faction and was executed at the time of her downfall; Sir Anthony Denny controlled Henry’s signature stamp and helped draw up the latter’s will.

Queens had their own intimate ladies, and the office lapsed under Mary and Elizabeth I. So the last Groom of the Stool in the strict sense was possibly Sir Michael Stanhope, who served Edward VI. He was hanged for ‘felony’ before Edward’s death, but it’s not clear if his role was then taken by anyone else.

Under the Stuarts, the office morphed into ‘Groom of the Stole’, with its implications of dressing the monarch rather than helping him visit the privy. Depending on the individual monarch, the role would also have devolved onto offices like Groom or Lord of the Bedchamber. The last person to hold the title of Groom of the Stole was James Hamilton, 2nd Duke of Abercorn (1838–1913) who served the Prince of Wales, but the job did not continue when the latter became King Edward VII.

Answered by: Eugene Byrne, author and journalist

In English royalty, the Groom of the Stool was originally a servant who assisted the king with bodily functions and washing. The stool in question was a ‘close stool’ – a fixed or portable commode – and help was needed with the putting on and taking off of elaborate and expensive clothing.

Under the Tudors, Grooms of the Stool were important functionaries because of this intimate access. All of Henry VIII’s grooms were knights. Sir Henry Norris, for instance, was closely aligned to Anne Boleyn’s faction and was executed at the time of her downfall; Sir Anthony Denny controlled Henry’s signature stamp and helped draw up the latter’s will.

Queens had their own intimate ladies, and the office lapsed under Mary and Elizabeth I. So the last Groom of the Stool in the strict sense was possibly Sir Michael Stanhope, who served Edward VI. He was hanged for ‘felony’ before Edward’s death, but it’s not clear if his role was then taken by anyone else.

Under the Stuarts, the office morphed into ‘Groom of the Stole’, with its implications of dressing the monarch rather than helping him visit the privy. Depending on the individual monarch, the role would also have devolved onto offices like Groom or Lord of the Bedchamber. The last person to hold the title of Groom of the Stole was James Hamilton, 2nd Duke of Abercorn (1838–1913) who served the Prince of Wales, but the job did not continue when the latter became King Edward VII.

Answered by: Eugene Byrne, author and journalist

Published on February 12, 2018 23:00

February 11, 2018

Q&A: When and why was the medieval law of outlawry eventually repealed?

History Extra

From Robin Hood to Sawney Bean, British history is full of stories of legendary outlaws...

Anyone declared an outlaw was denied any form of legal protection. Nobody was allowed to give them food, shelter or any kind of help, and they could be killed with impunity. Outlawry was most commonly imposed for failing to answer a court summons; with no national police force and plenty of hiding-places, outlawry was a simple, rough-and-ready, form of justice. There was also a civil equivalent, which didn’t carry the death penalty, but the defendant’s goods were usually forfeit to the plaintiff.

The Middle Ages saw plenty of famous outlaws, as well as some like Robin Hood or the Scottish cannibal Sawney Beane, who probably never existed. Some, such as 14th-century bandits like Eustace Folville or Adam the Leper, got away with it, or were pardoned. On the other hand, Richard Puddlecote was hanged and his skin nailed to the door of Westminster Abbey in 1305. But he had stolen most of the royal treasury, after all.

With the increasing integration of society and more sophisticated policing, outlawry became a formality. It was abolished in England under the Criminal Code (Indictable Offences) Act of 1879, but outlawry or ‘fugitation’ remained in force in Scotland until December 1949. The last Scottish outlaw was Charles Shaw Bland, who jumped bail in 1949 after being charged with housebreaking and assault.

This Q&A was answered by Eugene Byrne, author and journalist.

From Robin Hood to Sawney Bean, British history is full of stories of legendary outlaws...

Anyone declared an outlaw was denied any form of legal protection. Nobody was allowed to give them food, shelter or any kind of help, and they could be killed with impunity. Outlawry was most commonly imposed for failing to answer a court summons; with no national police force and plenty of hiding-places, outlawry was a simple, rough-and-ready, form of justice. There was also a civil equivalent, which didn’t carry the death penalty, but the defendant’s goods were usually forfeit to the plaintiff.

The Middle Ages saw plenty of famous outlaws, as well as some like Robin Hood or the Scottish cannibal Sawney Beane, who probably never existed. Some, such as 14th-century bandits like Eustace Folville or Adam the Leper, got away with it, or were pardoned. On the other hand, Richard Puddlecote was hanged and his skin nailed to the door of Westminster Abbey in 1305. But he had stolen most of the royal treasury, after all.

With the increasing integration of society and more sophisticated policing, outlawry became a formality. It was abolished in England under the Criminal Code (Indictable Offences) Act of 1879, but outlawry or ‘fugitation’ remained in force in Scotland until December 1949. The last Scottish outlaw was Charles Shaw Bland, who jumped bail in 1949 after being charged with housebreaking and assault.

This Q&A was answered by Eugene Byrne, author and journalist.

Published on February 11, 2018 23:00

February 10, 2018

Christian Round Churches Hide Astronomical Secrets of the Viking Seafarers

Ancient Origins

Orkney is an archipelago in the northern isles of Scotland, annexed by Norwegian explorers in 875 AD and Christianized by King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway, (960s – 1000). It was from Orkney where many of the early Viking raids into England were launched. Were Christian Viking round churches in Norway aligned with the round church in Orkney, Scotland, to support astronomical maritime navigation routes?

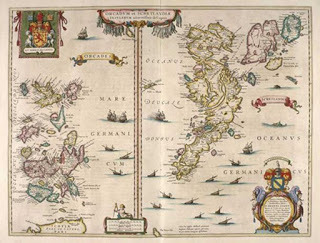

Blaeu's 1654 map of Orkney and Shetland. (Public Domain)

Haakon Paulsson, Jarl of Orkney

A Jarl is a Norse title, preceding the title of Earl. By the early 12th century the navigable channels between the islands of Orkney were controlled by Jarl Haakon Paulsson (Old Norse: Hákon Pálsson) (1103-c. 1123), whom King Magnus III of Norway had appointed regent in Orkney. Haakon was a descendant of the Norse lineage of Røgnvald (the Wise) and jointly ruled the Earldom of Orkney with his cousin Magnus Erlendsson, from 1105 - 1114, in which year Haakon had Magnus murdered. As penance for having unlawfully killed his cousin, church authorities ordered Haakon to undertake a pilgrimage to 'the burial place of Christ’, an adventure which was recorded in the Orkneyinga Saga (a historical narrative of the history of Orkney from the 9th to 12th century):

“Haakon faired south to Rome, and to Jerusalem…upon his return he became a good ruler, and kept his realm well at peace and he built Orphir Church to replicate the Templar built rotunda in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre which he had visited while he was in Jerusalem.

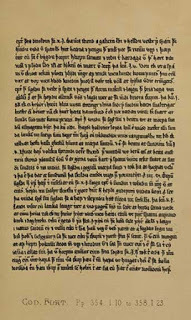

An example of a page from the Orkneyinga saga, as it appears in the 14th century Flatey Book. (Public Domain)

Was Haakon Paulsson a Templar Knight? Haakon was a wealthy warlord who had undertaken a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, in the fashion of the Templars. He even had a round church built in the style of the Templar rotunda, which he encountered in Jerusalem, upon his return to Orkney. He had visited Jerusalem at the same time as the founding Knights Templar. An interpretation panel installed at Orphir Round Church claims it is the “northernmost Knights Templar round church in the UK”. However, it is disputed whether Haakon built a “Templar church”.

Although Templars vowed to ‘defend the Church of the Holy Sepulchre’ and subsequently built many round churches reflecting its underlying design, circular church design was not limited to Templar architecture and several monastic institutions had built in the circular style. Nevertheless, so often it is written that all of Europe’s circular churches were built by the Knights Templar, but it is much closer to the truth to say that ‘they built some, possibly most’ of Europe’s medieval round churches.

King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway, (960s – 1000) who forcibly Christianized Orkney. Painting by Peter Nicolai Arbo. (Public Domain)

Furthermore, if Haakon had become a Templar Knight in Jerusalem then he would have been obliged upon joining to relinquish his “material wealth and possessions” to the Order. This transaction would certainly have included his valuable agricultural and strategically located lands at Orphir and as such it would have been listed somewhere in the inventories of Templar properties in Scotland. However, there is no mention of Orphir anywhere in the records. The northernmost Templar property recorded in Scotland was a Preceptory House (farm, temple, bank) located in Dingwall on the Black Isle, near Inverness. It must be added however, that many 12th century knights and noblemen avoided the ranks of the Knights Templar for socio-political reasons, yet they maintained strong mercantile and military relationships with the Order.

Ashley Cowie is a Scottish historian, author and documentary filmmaker presenting original perspectives on historical problems, in accessible and exciting ways. His books, articles and television shows explore lost cultures and kingdoms, ancient crafts and artifacts, symbols and architecture, myths and legends telling thought-provoking stories which together offer insights into our shared social history. www.ashleycowie.com.

Top Image: Wasteland Viking Ship. (CCO Public Domain)

By Ashley Cowie

Published on February 10, 2018 23:00

February 9, 2018

Beer Over Wine? New Find Indicates Bronze Age Greeks Imbibed Both Beverages!

Ancient Origins

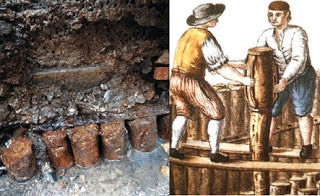

Wine wasn’t the only drink popular with ancient Greeks, according to a new report. The discovery of two Bronze Age breweries suggests that beer was a popular choice for alcohol too.

Researcher Tania Valamoti, an associate professor of archaeology at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, expressed her surprise to Live Science, stating, “It is an unexpected find for Greece, because until now all evidence pointed to wine.” However, according to Greek Reporter, beer making may have reached Greece through their contact with people living in the eastern Mediterranean – where brewing was already widespread.

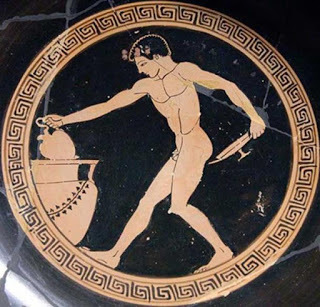

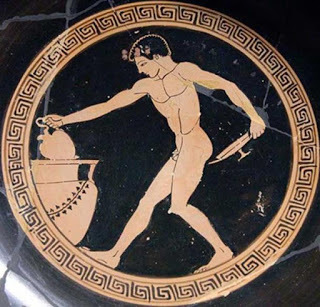

Wine boy at a Greek symposium. ( Public Domain )

Archondiko and Agrissa are the two locations were indications of buildings used for ancient beer brewing have been found. Both locations have markings of fire damage, but Valamoti said that this event helped in preservation. Approximately 100 individual sprouted cereal grains were unearthed at Archondiko as well as a two-roomed structure which may have been used to control temperatures in preparing mash and wort during the brewing process. 30 strange cups were also found near the sprouted grains, which may have been used with a straw to sip prepared beer.

About 3,500 sprouted cereal grains were found at Agrissa. These have been dated to the middle Bronze Age, unlike the Archondiko sprouted grains which are from the early Bronze Age. 45 cups, which may have been used to drink the beer, were also found near the sprouted grains at the Agrissa site.

The sprouted grains found at the sites may have been created during the malting process of beer making. The grains would then be roasted, coarsely ground and mixed with water to make wort, and finally fermented. Researchers say that the condition of the grains at Archondiko are also consistent with the effects of malting and charring.

A blend of milled malted barley for beer brewing. ( CC BY SA 3.0 )

Valamoti feels confident that the archaeological remains suggest beer brewing was taking place at the Bronze Age sites, she said, “I'm 95 percent sure that they were making some form of beer. Not the beer we know today, but some form of beer.”

However, it is worth noting that beer was not seen on the same level as wine in ancient Greece, as Valamoti also wrote in the study, as published in the journal Vegetation History and Archaeobotany:

“Textual evidence from historic periods in Greece clearly shows that beer was considered an alcoholic drink of foreign people, and barley wine a drink consumed by the Egyptians, Thracians, Phrygians and Armenians, in most cases drunk with the aid of a straw.”

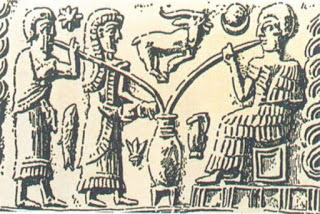

Egyptian wooden model of beer making in ancient Egypt. ( CC BY 2.5 )

Although the Bronze Age beer brewing practices in Greece are an interesting prospect, they are certainly not the oldest example of beer making in the world. Ancient Origins has reported on several examples of beer drinking from well before the Bronze Age. Many beer recipes from hundreds or thousands of years ago have even been recreated. For example, recovered Sumerian, Chinese, and French recipes have all been tried by modern palates.

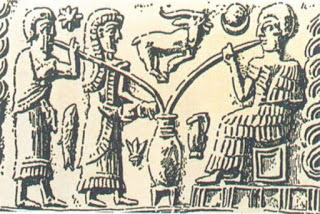

The oldest depiction of beer-drinking shows people sipping from a communal vessel through reed straws (Brauerstern)

Archaeological evidence of beer drinking has been found in civilizations throughout the ages and all over the world: an analysis of mummy hair shows ancient Peruvians enjoyed the alcoholic beverage with their seafood, Stone Age people seemed to prefer beer over bread, Medieval monks drank more beer than you can imagine, and corn beer was a popular choice in Mexico. Cheers!

Top Image: A glass of beer. Source: Public Domain

By Alicia McDermott

Wine wasn’t the only drink popular with ancient Greeks, according to a new report. The discovery of two Bronze Age breweries suggests that beer was a popular choice for alcohol too.

Researcher Tania Valamoti, an associate professor of archaeology at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, expressed her surprise to Live Science, stating, “It is an unexpected find for Greece, because until now all evidence pointed to wine.” However, according to Greek Reporter, beer making may have reached Greece through their contact with people living in the eastern Mediterranean – where brewing was already widespread.

Wine boy at a Greek symposium. ( Public Domain )

Archondiko and Agrissa are the two locations were indications of buildings used for ancient beer brewing have been found. Both locations have markings of fire damage, but Valamoti said that this event helped in preservation. Approximately 100 individual sprouted cereal grains were unearthed at Archondiko as well as a two-roomed structure which may have been used to control temperatures in preparing mash and wort during the brewing process. 30 strange cups were also found near the sprouted grains, which may have been used with a straw to sip prepared beer.

About 3,500 sprouted cereal grains were found at Agrissa. These have been dated to the middle Bronze Age, unlike the Archondiko sprouted grains which are from the early Bronze Age. 45 cups, which may have been used to drink the beer, were also found near the sprouted grains at the Agrissa site.

The sprouted grains found at the sites may have been created during the malting process of beer making. The grains would then be roasted, coarsely ground and mixed with water to make wort, and finally fermented. Researchers say that the condition of the grains at Archondiko are also consistent with the effects of malting and charring.

A blend of milled malted barley for beer brewing. ( CC BY SA 3.0 )

Valamoti feels confident that the archaeological remains suggest beer brewing was taking place at the Bronze Age sites, she said, “I'm 95 percent sure that they were making some form of beer. Not the beer we know today, but some form of beer.”

However, it is worth noting that beer was not seen on the same level as wine in ancient Greece, as Valamoti also wrote in the study, as published in the journal Vegetation History and Archaeobotany:

“Textual evidence from historic periods in Greece clearly shows that beer was considered an alcoholic drink of foreign people, and barley wine a drink consumed by the Egyptians, Thracians, Phrygians and Armenians, in most cases drunk with the aid of a straw.”

Egyptian wooden model of beer making in ancient Egypt. ( CC BY 2.5 )

Although the Bronze Age beer brewing practices in Greece are an interesting prospect, they are certainly not the oldest example of beer making in the world. Ancient Origins has reported on several examples of beer drinking from well before the Bronze Age. Many beer recipes from hundreds or thousands of years ago have even been recreated. For example, recovered Sumerian, Chinese, and French recipes have all been tried by modern palates.

The oldest depiction of beer-drinking shows people sipping from a communal vessel through reed straws (Brauerstern)

Archaeological evidence of beer drinking has been found in civilizations throughout the ages and all over the world: an analysis of mummy hair shows ancient Peruvians enjoyed the alcoholic beverage with their seafood, Stone Age people seemed to prefer beer over bread, Medieval monks drank more beer than you can imagine, and corn beer was a popular choice in Mexico. Cheers!

Top Image: A glass of beer. Source: Public Domain

By Alicia McDermott

Published on February 09, 2018 23:00

February 8, 2018

Medieval money tricks

History Extra

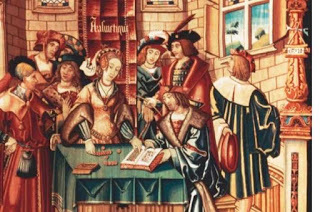

A loan transaction being recorded in a ledger, shown in a Flemish tapestry known as The Liberal Arts – Arithmetic, of around 1520. (Getty)

Financial engineering has not had a good press of late. A whole alphabet soup of complex financial practices have been blamed for the recent financial crisis. One such process, called securitisation, saw banks bundling up thousands of loans – many of which had been made to borrowers who would have trouble meeting the repayments – into large, hugely complex products and selling them on to investors.

Even now, some of the world’s largest banks are being investigated for manipulating LIBOR, a key financial standard determining the interest rates charged to millions of borrowers.

This complicated relationship between financial innovation and wider economic, political and social considerations is not new, however, and can be traced back to the Middle Ages and even beyond.

Typical ingenuity

The development of new financial instruments, such as insurance, banknotes, cheques, ATM machines and online banking can help economic growth by facilitating trade and extending access to credit (what we might term ‘good’ financial innovation). However, financial engineering throughout history has also been driven by the desire to circumvent restrictions placed on financial activities – what is euphemistically described as ‘regulatory arbitrage’ (or ‘bad’ financial innovation).

In the Middle Ages, the religious prohibition of usury – the charging of interest or ‘making money from money’ – presented the greatest obstacle to the expansion of the medieval financial sector but, with typical ingenuity, medieval merchants and bankers soon found ways around it.

There were many ways of structuring transactions in order to disguise the charging of interest. Perhaps the simplest was for the borrower to recognise that he owed a greater sum than that actually received; for instance the debtor might issue a legally binding bond for £15 when he had in fact only received £10, with the £5 difference representing interest. An example of this practice is discussed in case study 1 (see below).

Another means of disguising interest charges was for the loan agreement to include a penalty clause in case of ‘late’ repayment, where the loan was expected from the start to be repaid late. Today banks offer free current accounts, funded in part by penalty fees for being overdrawn and other infringements.

Another medieval practice with modern resonance was ‘chevisance’ or a repurchase arrangement. A borrower would sell goods to the lender at one price with the understanding that the borrower would buy them back at a higher price. A similar logic informs the shadow banking system ‘repo’ market today, in which financial institutions raise short-term funds by pledging collateral. Finally, the borrower could pay the lender a ‘donum’ or ‘voluntary’ gift on top of the principal. An example of this is given in case study 2 (see below).

The most sophisticated method of disguising interest used bills of exchange. These were foreign exchange (FX) instruments, originally developed to transfer money for trade but which also involved a credit element. The bill of exchange stated that the seller of the bill had received a sum of money in the local currency from the buyer in place A to be repaid, after a set period, in place B in another currency at a set exchange rate. The seller of a bill of exchange was effectively a borrower, and the buyer the lender.

Interest was disguised by manipulating the exchange rates at places A and B, with the interest rate being determined by the difference, or spread, between the two rates; the wider the spread, the higher the profits. However, to produce this differential or spread required the systematic adjustment of exchange rates in all major financial centres. A practical example of this is described in case study 3 (see below).

Finance and morality

But was all this financial innovation necessarily wrong? If there was no way of circumventing the usury prohibition by charging interest, then why would investors have lent to borrowers, including governments, at all? It could be argued that the bill of exchange was an example of ‘good’ financial innovation that facilitated European trade, but which was subsequently repurposed by the financial sector as a means of hiding their profits (‘bad’ financial innovation). But this is an over-simplification. Without the system of differential exchange rates, it would have been much more difficult to profit from FX transactions. There would therefore have been no incentive for the medieval bankers to engage in FX and this would have reduced the ability of merchants to borrow money or to transfer money internationally in order to fund their trading ventures.

There are two general problems with financial engineering and innovation, then and now. First, in so far as medieval financiers sought to disguise interest charges, this could create (perhaps deliberately) informational asymmetries. In the Middle Ages, merchants were presumably better able to calculate the interest rates implied by gifts or penalties or to predict future exchange rate movements than their customers, and this might have allowed them to charge higher rates. Similarly, it has been argued that modern financial institutions operate as a ‘confusopoly’ and regulators have imposed large fines on banks for the ‘mis-selling’ of products including endowment mortgages, payment protection insurance and interest-rate swaps.

Second, finance has an inescapably political dimension. Although financial engineering may have been accepted as business as usual within the financial community, the wider public could be less understanding.

For example, Londoner Richard Lyons was deeply involved in crown finance during the last years of Edward III’s reign. In one case, he arranged a loan of 20,000 marks for the king and charged 10,000 marks in interest. This was not necessarily an excessive rate for the time but Lyons was suspected of undue profiteering. He was first impeached by parliament and subsequently beheaded by a mob during the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. Today there is intense suspicion of the relationship between the Too Big to Fail banks and the government. Those who work in the financial sector should therefore consider not just how the system works, but how this may appear to others.

It seems that there is a continuous thread of conflicting attitudes towards financial practices in the Middle Ages and today. For those involved in the markets, ‘financial engineering’ helps to keep the markets running smoothly. From an external perspective, however, certain financial practices could seem at best amoral and at worst, illegal. It therefore confirms peoples’ pre-existing suspicion of finance when details about the innovations developed to hide usury in the Middle Ages, or to fix LIBOR today, come to light.

Case study 1: Discounting

When Matthew Paris, the 13th-century English chronicler, reported the death-bed words of Robert Grosseteste, the reforming bishop of Lincoln (died 1253), he included some financial advice. It should be noted that this source tells us more about Paris’s opinions than those of the bishop:

For example, I take up a one-year loan of a hundred marks [£66 13s 4d] for a hundred pounds. I am obliged to make and seal a bond, in which I acknowledge receipt of a loan of a hundred pounds, payable in one year. But if you should wish to repay the money that you received to the pope’s usurer within a month, or sooner, he will not receive anything other than the full hundred pounds, which terms are heavier than those of the Jews.

In this hypothetical example, the interest rate works out at 50 per cent per annum if the 100 marks were received at the start and £100 repaid at the end of one year. Were the £100 to be repaid within the year, however, then the effective annualised rate would be much higher. If it was repaid after one month, as above, the annualised interest rate would be 600 per cent. Conversely, if the debtor could delay payment beyond the year, then the annualised rate of interest would fall – if it was repaid after two years, without incurring any further charges, then the effective rate of interest would be reduced to 22.5 per cent per annum. By contrast, the Jews were not subject to the usury prohibition and could openly charge interest. The king regulated and protected this market, capping the rate at 2d in the pound (of 240d) per week for the length of the loan – corresponding to an annualised non-compounded interest rate of 43.3 per cent.

Case study 2: Gifts

From 1272 until c1342 the kings of England employed a succession of Italian merchant societies as ‘bankers to the crown’. The granting of periodic gifts to the Italians was the preferred means of paying interest. For example, in the three years 1328–31, Edward III borrowed around £42,000 from the Bardi of Florence and promised them gifts totalling £11,000. Later, after the relationship between Edward and the Bardi had broken down in the 1340s, an Exchequer official calculated that the Bardi had been promised over £84,000 since 1309 as gifts. He argued that these were ‘usury’ and that the king should not be bound to pay them.

This document records a gift made by Edward III’s father, Edward II, to his then bankers, the Frescobaldi of Florence:

Charged to Ingelard de Warley, keeper of the wardrobe on 10 July 1310 – £1,000 paid to Amerigo di Frescobaldi and his fellows, merchants of the society of the Frescobaldi of Florence, of the king’s gift, for certain damages that they sustained in the third year [1309–10] by reason of a certain loan of 10,000m [£6,666 13s 4d] made to the king by them as it appears by a wardrobe bill that they have returned. [Paid] in five tallies made to various recipients as appears in the great roll of the receipt for the same day. By order of the treasurer.

This case is particularly valuable because we have detailed information about the amounts and dates of advances and repayments. It is therefore possible to reconstruct the interest rate represented by this gift, which works out to be 23.67 per cent annually. From this and other similar examples,it seems that the English kings could normally borrow at between 15 per cent and 25 per cent per annum but, during times of financial pressure, they might have to pay interest rates of 40 per cent to 60 per cent and even higher. Case study

3: Exchange rate manipulation

The use of bills of exchange to extend credit rather than to actually transfer money was called ‘dry exchange’ and can best be demonstrated in practice as follows (also summed up above): In Venice on 26 September 1442, Francesco Venier & Bros sold a bill of exchange for 150 ducats to Cosimo di Medici and Co, payable in London after three months at the rate of 44½ pence sterling per ducat. Medici sent the bill of exchange to his representatives in London, where they should have received £27 16s 3d (6,675d). When they presented the bill for payment on 31 December, however, Venier’s representatives refused to pay (probably by prior agreement with Medici) and the bill was ‘rechanged’ or sent back to Venice to be settled in another three months.

But this second exchange transaction took place at the rate prevailing in London, which two FX brokers testified was 41¼ pence sterling. As a result of this spread or difference of 3¼ pence between the rates in Venice and London, Venier repaid Medici not the original 150 ducats, but just under 162 ducats. In short, Venier had borrowed 150 ducats for six months and paid 12 ducats in interest, an annualised interest rate of 15.7 per cent.

This built-in spread was not, of course, the only factor influencing exchange rate movements. The pattern of international trade resulted in seasonal flows of money from one country to another while less predictable events, such as war or political unrest, could also have a significant impact. A merchant’s profits therefore depended on his ability to predict market movements and to time his trades, just like today.

This paper is based on a new interdisciplinary research project investigating Medieval Foreign Exchange, funded by the Leverhulme Trust and based at the ICMA Centre, Henley Business School, University of Reading. The research team is: Professor Adrian Bell, chair in the history of finance and head of school; Professor Chris Brooks, chair in finance and director of research; and Dr Tony Moore, research associate.

Published on February 08, 2018 23:00

The Construction of Venice, the Floating City

Ancient Origins

Venice, Italy, is known by several names, one of which is the ‘Floating City’. This is due to the fact that the city of Venice consists of 118 small islands connected by numerous canals and bridges. Yet, the buildings in Venice were not built directly on the islands. Instead, they were built upon wooden platforms that were supported by wooden stakes driven into the ground.

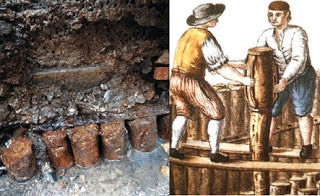

The story of Venice begins in the 5th century A.D. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, barbarians from the north were raiding Rome’s former territories. In order to escape these raids, the Venetian population on the mainland escaped to the nearby marshes, and found refuge on the sandy islands of Torcello, Iesolo and Malamocco. Although the settlements were initially temporary in nature, the Venetians gradually inhabited the islands on a permanent basis. In order to have their buildings on a solid foundation, the Venetians first drove wooden stakes into the sandy ground. Then, wooden platforms were constructed on top of these stakes. Finally, the buildings were constructed on these platforms. A 17th century book which explains in detail the construction procedure in Venice demonstrates the amount of wood required just for the stakes. According to this book, when the Santa Maria Della Salute church was built, 1,106,657 wooden stakes, each measuring 4 metres, were driven underwater. This process took two years and two months to be completed. On top of that, the wood had to be obtained from the forests of Slovenia, Croatia and Montenegro, and transported to Venice via water. Thus, one can imagine the scale of this undertaking.

The city of Venice was built on wooden foundations.

The use of wood as a supporting structure may seem as a surprise, since wood is relatively less durable than stone or metal. The secret to the longevity of Venice’s wooden foundation is the fact that they are submerged underwater. The decay of wood is caused by microorganisms, such as fungi and bacteria. As the wooden support in Venice is submerged underwater, they are not exposed to oxygen, one of the elements needed by microorganisms to survive. In addition, the constant flow of salt water around and through the wood petrifies the wood over time, turning the wood into a hardened stone-like structure.

As a city surrounded by water, Venice had a distinct advantage over her land-based neighbours. For a start, Venice was secure from enemy invasions. For instance, Pepin, the son of Charlemagne, attempted to invade Venice, but failed as he was unable to reach the islands on which the city was built. Venice eventually became a great maritime power in the Mediterranean. For instance, in 1204, Venice allied itself with the Crusaders and succeeded in capturing the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. Nevertheless, Venice started to decline in the 15th century, and was eventually captured by Napoleon in 1797 when he invaded Italy.

As of today, the lagoon that has protected Venice from countless foreign invaders is the biggest threat to its survival. To the local Venetians, the flooding of the city seems to be a normal phenomenon, as the water level rises about a dozen times a year. These floodings are known as aqua alta (high water), and are generally caused by unusually high tides due to strong winds, storm surges, and severe inland rains. However, this is happening more frequently in recent years due to the rising sea level caused by climate change, which is starting to alarm the city. Thus, a number of solutions have been proposed to rescue Venice from sinking. One of these measures is the Mo.S.E. (Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico, or Experimental Electromechanical Module) Project. This involves the construction of 79 mobile floodgates which will separate the lagoon from the Adriatic when the tide exceeds one meter above the usual high-water mark. Nevertheless, some pessimistic observers doubt that such measures will be sufficient to preserve Venice forever, and that the city will eventually sink, just like the fabled city of Atlantis.

Featured image: Beautiful Water Street Venice. Photo source: BigStockPhoto

By Ḏḥwty

Venice, Italy, is known by several names, one of which is the ‘Floating City’. This is due to the fact that the city of Venice consists of 118 small islands connected by numerous canals and bridges. Yet, the buildings in Venice were not built directly on the islands. Instead, they were built upon wooden platforms that were supported by wooden stakes driven into the ground.

The story of Venice begins in the 5th century A.D. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, barbarians from the north were raiding Rome’s former territories. In order to escape these raids, the Venetian population on the mainland escaped to the nearby marshes, and found refuge on the sandy islands of Torcello, Iesolo and Malamocco. Although the settlements were initially temporary in nature, the Venetians gradually inhabited the islands on a permanent basis. In order to have their buildings on a solid foundation, the Venetians first drove wooden stakes into the sandy ground. Then, wooden platforms were constructed on top of these stakes. Finally, the buildings were constructed on these platforms. A 17th century book which explains in detail the construction procedure in Venice demonstrates the amount of wood required just for the stakes. According to this book, when the Santa Maria Della Salute church was built, 1,106,657 wooden stakes, each measuring 4 metres, were driven underwater. This process took two years and two months to be completed. On top of that, the wood had to be obtained from the forests of Slovenia, Croatia and Montenegro, and transported to Venice via water. Thus, one can imagine the scale of this undertaking.

The city of Venice was built on wooden foundations.

The use of wood as a supporting structure may seem as a surprise, since wood is relatively less durable than stone or metal. The secret to the longevity of Venice’s wooden foundation is the fact that they are submerged underwater. The decay of wood is caused by microorganisms, such as fungi and bacteria. As the wooden support in Venice is submerged underwater, they are not exposed to oxygen, one of the elements needed by microorganisms to survive. In addition, the constant flow of salt water around and through the wood petrifies the wood over time, turning the wood into a hardened stone-like structure.

As a city surrounded by water, Venice had a distinct advantage over her land-based neighbours. For a start, Venice was secure from enemy invasions. For instance, Pepin, the son of Charlemagne, attempted to invade Venice, but failed as he was unable to reach the islands on which the city was built. Venice eventually became a great maritime power in the Mediterranean. For instance, in 1204, Venice allied itself with the Crusaders and succeeded in capturing the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. Nevertheless, Venice started to decline in the 15th century, and was eventually captured by Napoleon in 1797 when he invaded Italy.

As of today, the lagoon that has protected Venice from countless foreign invaders is the biggest threat to its survival. To the local Venetians, the flooding of the city seems to be a normal phenomenon, as the water level rises about a dozen times a year. These floodings are known as aqua alta (high water), and are generally caused by unusually high tides due to strong winds, storm surges, and severe inland rains. However, this is happening more frequently in recent years due to the rising sea level caused by climate change, which is starting to alarm the city. Thus, a number of solutions have been proposed to rescue Venice from sinking. One of these measures is the Mo.S.E. (Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico, or Experimental Electromechanical Module) Project. This involves the construction of 79 mobile floodgates which will separate the lagoon from the Adriatic when the tide exceeds one meter above the usual high-water mark. Nevertheless, some pessimistic observers doubt that such measures will be sufficient to preserve Venice forever, and that the city will eventually sink, just like the fabled city of Atlantis.

Featured image: Beautiful Water Street Venice. Photo source: BigStockPhoto

By Ḏḥwty

Published on February 08, 2018 00:00