Chris Abouzeid's Blog, page 35

August 20, 2013

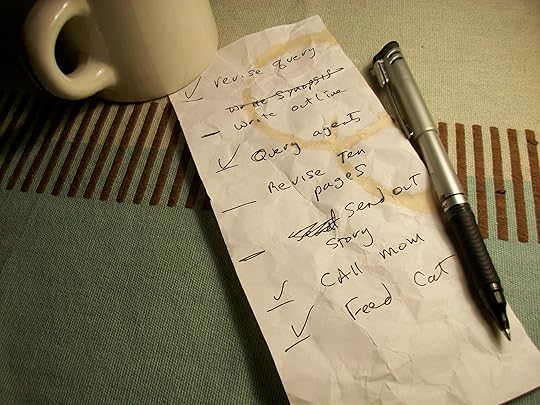

Somebody Loves You: What To Do When An Agent Says Yes

It’s another gray morning for you, the long-suffering Writer-Querier. As usual, you take a moment to steel yourself, then open your email for the daily parade of rejections.

The Flatterer: “Mr. J — Although you deftly draw us into this dark world of addiction, and I was moved by the protagonist’s struggles, I am going to pass on this one…” [DELETE]

The Economist: “I was certainly intrigued when I began reading your novel, however, in this challenging market…” [DELETE]

The All-Purpose Generic Not-That-Into-You: “I’m afraid I just don’t feel strongly enough about this….” [DELETE] [DELETE] [DELETE]

And then this one:

“Dear Jim — Stayed up all night reading your masterful Portrait of the Artist as a Lego Addict and would be thrilled to represent you – when can we talk?”

It takes a minute. Those rusty synapses (the ones that don’t travel through the rejection lobe) slowly fire. Your finger retreats shakily from the delete key. A light-headedness settles over you, followed by a touch of nausea and, finally, you smile. You close your eyes, look again. It’s still there.

NOW what? Who thought THIS was ever going to happen?

Well, it does happen. And it may happen to you. So here are a few tips for when that moment comes:

Keep a small hand towel ready. Drool and tears are bad for the keyboard.

DON’T immediately write back and say “YES, YES, YES!! Of COURSE you can represent me, because I love you!”

DO take a deep breath and write back something more like this: “I am so happy to hear that you like my book. I would love to set up a time when we can talk . . .” Finish it. Read it over. Hit SEND.

Okay, now, take a cautious step away from the trees to look at your forest.

Check your notes on this agent. Of course, you likely would not have queried him or her if there was any question of legitimacy. On the other hand, querying can get desperate. So… just check. No red flags? Good.

Check if other agents have your manuscript. If so, you should notify them that you have received an offer or representation. Another agent may be interested or may request time to finish reading.

Make sure you:

Send emails to all who have your manuscript – partial or full — notifying them that you have received an offer of representation.

Include relevant info in the subject line: “OFFER OF REPRESENTATION – Portrait of An Artist As a Lego Addict” I have never been an agent, but it’s a pretty safe bet that they get batches and batches of “Just checking-in” emails from querying writers every day. You need to let them know that yours is a time-sensitive issue.

What about agents whom you have queried but not heard back from yet – is there a reason to contact them? I think the answer is… probably not. Exception — if there is an agent whom you feel would be an extremely good fit for your book, you may want to let him or her know that you have received an offer.

Okay, now back to that brilliant, perceptive agent who has seen your worth. What information do you need from him or her before you make a decision to sign? Time to make a list of questions. Here are some I would suggest:

“What do you especially like about my book?”

“Are there books which you feel are similar to mine?”

“Do you think it would benefit from further revision before submission and, if so, what aspects need work?”

“What kind of timeline do you envision?”

“Do you have particular editors/publishing houses in mind?”

“Do you think my book has foreign sales potential and, if so, who would handle that for you?”

“What other support can your agency offer?”

“Could I take a look at your author-agency agreement?”

Even if you are fairly certain that you want to sign with this person, end the phone call with something like “I’m very happy about this. I do need some time to think about it.” Most agents understand this, and you should be concerned if an agent tries to pressure you to sign immediately.

Now you can sit back for a minute and savor this moment of success. Somebody loves you. (Or at least loves your book.)

END OF PART I – STAY TUNED FOR THE SEQUEL…

Originally appeared on Beyond the Margins March 5, 2010.

August 19, 2013

Revising Regret: The Imaginative Wealth Of What Didn’t Take Place

By Robin Black

For a long time now, I have had a hunch that there is a connection between regret and fiction writing – beyond the obvious possibility that one might regret ever having started to write fiction.

Regret is among a very few emotions that cannot exist without an accompanying narrative. I wish I had gone on that trip because . . .I then would have met the love of my life; I then wouldn’t have set the house on fire; I then would have seen Paris before I died, which would have made dying more bearable for me. All regret carries within it a particular kind of fiction, one in which the rules of causality and chance are suspended – generally, in favor of the certainty of a happy end. We who know that we do not know what any future moment might bring, convince ourselves that we can know what would have happened in the past. . . if only. Regret makes confident storytellers of us all.

It also makes us fans of bold action – retrospectively, anyway. Social scientists and psychologists tell us with certainty that people are more likely to regret what they have not done than what they have done. Since that concept of ‘doing’ and ‘not doing’ is a slippery one – when you don’t go on the trip you do stay home – I take this to mean that people tend to feel regret when they perceive that they have failed to do something more often than when they perceive that they have actively done the wrong thing. It’s the missed opportunity that feels poignant. The road not taken. The challenge to which we do not rise. The one who got away.

The imagination is awakened by the unknown in a way it can never be by the known. Despite its reputation as a waste of spirit and of time, regret teaches us many things, including that what didn’t happen can be a fiction writer’s greatest material source.

regret teaches us many things, including that what didn’t happen can be a fiction writer’s greatest material source.

Often, when I am writing a story – or, recently, my novel – I will reach a point at which the whole structure takes on a moribund, fruitless quality. The narrative, once brimming with life and promise, has died – sometimes quite suddenly. (I bring this up because I suspect that I’m not the only one whose narratives nose-dive mid-composition in this way.) There are many reasons this can happen, but I believe that one of the biggest impediments to reviving such works is a too great attachment to what has happened in our stories up to that point. As soon as words and the events they comprise are on paper, they take on an unhelpfully inevitable quality. And so, we writers look forward as if - lifelike- what’s done is truly done and ask: What can next happen to improve this situation?

But, as regret narratives demonstrate time and again, what didn’t happen in a story may actually be a far greater resource for imaginative thinking than is what did. These days whenever I hit that still and frightening place in my work, instead of pushing forward as I used to try to do, I go back, convinced that I will find a moment of decision gloriously brimming with might have beens. I look for lines like: I thought of telling him what had happened the night before, but decided against it. Or, I could have run after her and pleaded my case, but instead, went back inside. Or, She stared at the phone for a very long while, but never picked it up. In other words, I look for the points of inaction that my characters might themselves later regret, those decisions that might one day inspire in them the rich fictions of which we are all such gifted authors when we regret having chosen the more passive, the safer of two possible paths.

For characters, as for us all, there are moments that feel like forks in the road, and while of course there are fictional beings whose inaction is itself a defining, essential quality, more often – in my work, anyway – the failure of one of my characters to act is the result of my hesitation and not his or hers. As an author, there can be a certain satisfaction in early drafts to keeping things relatively simple. For some of us, the lure of completion is alone enough to guarantee that. When I write, I have something like a heat sensor that can detect possible complications, the difficult exchanges, the entanglements that might arise; and against all interests of the story, though perhaps with the illusion of a faster path to its end, it is often my first instinct to avoid such sparks and fires – until one day I sit down at the computer to a narrative that has taken on a deathly, immobile quality.

Just last week, at such a point in my novel, I went back and discovered, as I almost always do, the moment at which my central character chose inaction over a more complicated course. I changed her mind and – let’s just run with this metaphor – breathed life and energy back into the typescript corpse.

In real life, we don’t get to return to our twenties and step onto the airplane we were afraid to fly or audition for the play that excited and scared us or ask the beauty to dinner or take the job in Boston. What’s done is done – in real life – and all we can do is tell ourselves the poignant, intuitively well-crafted stories of what might have been.

But in fiction, what has been done can be undone and what hasn’t been done can be done. And maybe it will help you, next time your story seems to have died on the screen to wander back through it and try to replace a poorly placed no, with a well placed yes. And see what happens. See that something happens.

No regrets.

Originally appeared on Beyond the Margins September 6, 2012.

August 18, 2013

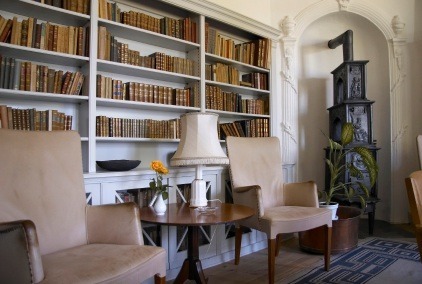

What Your Shelves Say About You

Not long ago on my Facebook page, a friend posed this question: What are your criteria for keeping a book when you have limited shelf space in the house? What makes a book a keeper?

Clearly, she struck a chord. The comments scrolled down, filling the page and bumping off the cute picture of my youngest child.

“I keep everything!” said my friend Allison. “I want a sliding ladder for my bookshelves!” A few comments later, Jenna Blum, the New York Times-bestselling author of Those Who Save Us, shared her rule of thumb for giving a book away vs. keeping it. “My criteria for donating a book is if I don’t dogear the corner of a single page, meaning, I didn’t find one sentence/ thought/ turn of phrase to admire.”

“Something you’ve read, or you want people to THINK you’ve read,” said Peter, a colleague from my magazine-staff days. A high-school friend, Catherine, agreed: “I was just talking to a friend about the concept of re-arranging/hiding the books based on who my guests might be.”

This reminded me of an old friend we’ll call John, because that was his name, who once told me he stacked his paperbacks double-deep. This way, he could rotate the Mr. Sensitive Intellectual books in front of the Clive Cusslers when he had a hot date.

Lucky ladies.

Moving books around depending on who might see them? Editing what your bookshelves say about you, by the day, by the occasion? It seems so bookishly… Machiavellian.

But maybe it isn’t. After all, who among us hasn’t squirmed while a dinner guest scrutinized our shelves? Wondering if he was judging, say, those thrillers, consumed one after another that summer spent traveling after college? Or smirking at the copy of Jonathan Livingston Seagull received long ago from a soulful (cough, pretentious) boyfriend? Or curious about the commentary on faith made by the tableaux of Life of Pi, Gilead and The Tao of Pooh?

All of this got me wondering about the art and politics of bookshelf order.

Which, really, could be an entire untapped career path. There are gigs for interior decorators who will feng shui your home, and for creative orderly folk who will do your family scrapbooking and organize your closets. Why not a consultant to arrange your bookshelves and put your literary taste in its best possible light, intellectually and visually?

A Facebook friend of mine in Holland recently posted a question similar to the one that appeared on my page. How do you organize your books?

His friends were downright evangelical about their systems. Many said they shelve by genre, though a few alphabetized across the board. Some said size matters — that there‘s nothing more discordant than a shelf with a jagged skyline. Still others said they group books by color, to create an aesthetically pleasing swath of coordinating spines. I paused at that, envisioning Amsterdam living rooms with an IKEA sensibility, all cool order and stackable passion. Then imagined systems that would put Beckett beside Binchy, or a silver Sartres next to the latest Picoult of the same hue. Oh, those crazy Dutch.

But I have to admit: I do cringe a little when people look at my bookshelves. When we moved into our house three years ago — the first home we’d owned with lots of built-ins — there were negotiations. My husband has a million nonfiction hardcovers, the brainiac stuff of history buffs and policy wonks. I have a billion novels, half of them paperback.

My husband is of the school of thinking that paperbacks aren’t meant for display. Old and comfortable, sure, but not the underwear you want to be wearing when you have a car accident. Still, I’m proud of these old favorites going back to my rice-and-beans days as an editorial assistant in Manhattan, when splurging on a hardcover or going to a movie was an either-or proposition.

So. In our den, the shelves are filled with the hardcovers he somehow managed to buy during his own mac and cheese days. Kozol and Zinn, Richard Ben Cramer and David McCullough. The Kennedys, pretty much anything written by or about them. Plus a little David Sedaris, Calvin Trillin, George Carlin.

And in the family room, my raggedy paperbacks are lined up like kids in hand-me-down clothes. My system wouldn’t be approved by The New York Review of Books, but it works.

Wallace Stegner sits beside John McPhee, shelfmates for their knowledgeable geography, dry humor and brilliant storytelling. Brits Simon Winchester and Ian McEwan are neighbors. Alice Walker keeps wise company with Toni Morrison and Charlotte Perkins Gilman, next to the Latin American magic realism. There’s no particular reason Geraldine Brooks should be shelved beside Marilynne Robinson except that I have such a deep respect for both their reporting and writing styles, so in my world, they go together. Justin Cronin, Gillian Flynn and Mary Daly might be oddballs, but they have their places, too. Shakespeare and poetry are available in upper corner, ready and waiting for the day I have time for them again, or when my children do.

Anna Quindlen would doubtless have something thoughtful to say about it all — the faces we choose to show the world and those we conceal, and what it costs us. So her essay collections sit nearby.

Luckily, they are more or less the right size and color.

Originally ran on Beyond the Margins March 4, 2010.

August 15, 2013

Best If Finished By: Expiration Dates on Inspiration

Many years ago, while driving down Charles Street, in Boston, I had what I call a “speculative vision.” It had rained during the night, and the morning sun glaring off the puddles was casting weak, golden halos around everything. Two men in long woolen coats suddenly passed in front of me, and in the strange morning light, they looked like hunched, wingless birds. That’s when the vision struck: Beacon Hill transformed into a ghetto of crumbled buildings and flooded streets, miles of barbed wire holding in a population of cold, dying bird-people.

Who were these people? How could Beacon Hill become a ghetto? Who would be on the inside and who would be on the outside? Why? These were the questions I had to answer, and since I was writing not long after the Reagan era (yes, I’m that old), the story I created—“Mercy Street”—reflected many of the issues of the time: AIDS, gay rights, religious extremism, conservative activism.

Almost as soon as I finished the story, the ground started to shift under my feet. The Boston Garden, a crumpled heap in my dystopian vision, got turned into the sparkly Fleet Center (now TD Banknorth Garden—yuck). The 93 overpass, meant to sag into the water, got cut up and trucked away during the Big Dig. And the Charles Street Jail, a granite hulk in my story, is now the luxurious Liberty Hotel. The only detail that has stayed faithful to my vision is the flooding of Storrow Drive. But it’s not nearly as often or as deep as I’d like.

The Boston Garden, a crumpled heap in my dystopian vision, got turned into the sparkly Fleet Center (now TD Banknorth Garden—yuck). The 93 overpass, meant to sag into the water, got cut up and trucked away during the Big Dig. And the Charles Street Jail, a granite hulk in my story, is now the luxurious Liberty Hotel. The only detail that has stayed faithful to my vision is the flooding of Storrow Drive. But it’s not nearly as often or as deep as I’d like.

The thematic aspects of my story suffered, too. Federal funding for HIV research, better treatment and higher survival rates all made my vision of the future seem more paranoid than speculative. And the shift in the national dialogue on gay and lesbian rights, inching away from “Who cares about a disease that kills gays?” to “Should we allow same sex couples to marry?”, has had the same effect on my story as leaving the cap off a bottle of seltzer. Flat. Flavorless. Dead.

Which brings me to my question: What do you do with a story that’s past its expiration date? Can you change the details and recycle the main ingredients? Can you substitute fresh problems for old ones without turning the whole thing into an indigestible mess?

Conventional wisdom says true art is timeless, and I guess that’s mostly true. The Iliad and The Odyssey haven’t lost much of their appeal, despite the fact that no one (except maybe Rick Riordan) has sacrificed anything to a Greek god in over a thousand years. And Jane Austen doesn’t seem to be losing fans, despite the disappearance of nearly all Victorian sense and sensibility.

But what about during the writing process itself? If the shadows of totalitarianism had begun to recede before George Orwell finished 1984, would he have kept going? If the civil rights successes of the 50′s and 60′s had taken place in the 30′s instead, would Richard Wright have kept working on Native Son? Would he have believed Bigger Thomas’s fate was as inevitable as ever? Or would he have begun to doubt the mechanistic vision of racism, poverty, and injustice that drives the novel?

Okay, it’s pretty hard to second-guess the literary greats. And since they are literary greats, we know their ideas passed the “sniff test” right up to the moment of publication, and beyond. But you and I, racing to preserve what we know in a world where everything sprouts and dies faster than the vine over Jonah’s head—we’ve got our work cut out for us.

So it’s worth repeating the question: What do you do with an idea that’s gone past its expiration date? Do you toss it aside and start something new, the way you’d pour old milk down the drain and open a new carton? Or do you do what I’ve been doing for the last twenty years—open that story up now and then, see if there’s a way to turn vinegar back to wine?

Originally published on Beyond the Margins on March 3, 2010.

August 14, 2013

Your Inner Bad Guy

By Julie Wu

I have never struck a child. I would like to think I never would, no matter what. No matter if I had been born in 1920, had eight children, an absent husband, and lived in an occupied country during World War II. I would like to believe that there is a huge, unbridgeable gulf between “a child abuser” and someone like me.

And that belief is a problem, because one of the characters in my book, The Third Son, does beat her son. Repeatedly. She singles him out, even siphoning food from him to her other children until he becomes malnourished. “I don’t understand why she’s so mean,” my readers have said, reading my drafts over the years.

I have worked hard to make all my other characters well rounded, believable. In a previous draft of my book, the narrator was omniscient and all the main characters had a point of view.

omniscient and all the main characters had a point of view.

Except this mother.

She was a monster who did not deserve a point of view. There are monsters like her, I thought. Not everyone is likeable. The fact that she was modeled after a real person who hurt someone I love made me empathize with her even less.

“No one could possibly be that mean.”

Well, yes, they could. I stuck to my guns. I wasn’t going to water her down. Hitler was real. Joan Crawford was real.

Over the years I have swallowed my pride and used all kinds of criticism to improve my book. Opening needs to change? Done. Second half needs a new plot? No problem. Hardly a page of the original manuscript exists. But the mother never changed.

Until now. My tenth year of working on the book, now under contract. My editor has called me to the carpet one last time: fix the mother.

Finally, I realized I have no excuses. I must round out this character. But in order to do that, I have to bridge that gulf. I need to do something I’ve never wanted to do before—get inside the head of the abuser.

I’ve realized the mother has always been hazy in my mind: essence of mean old woman. I prefer to think of her that way, distant from myself in every way. I have to force myself to think of her as she actually is—young, intelligent, with her own thwarted dreams. She does have eight children and a husband who is rarely home. She lives in a country that is not only occupied by a foreign power but is also repressive, a culture that condones physical punishment. Her days are marked by toil and fatigue, by fear, loss, and guilt, and never knowing how she will do it all.

It’s uncomfortable to think of her this way. I know why I resisted doing so for so long. Understanding her, empathizing with her, identifying with her—it’s a slippery slope, and it makes me wonder if there really is a great gulf between me and her, between the good guys and the villains. How much is character? How much is circumstance? How much differently would I really have behaved in her shoes?

I have gotten off my high horse, because the backstory, the view from the inside—that’s the difference between a monster and the face in the mirror.

Will you believe this mother now? I think so.

And I hope she makes you as uncomfortable as she makes me.

Originally appeared on Beyond the Margins November 17, 2011.

August 13, 2013

Should You Submit to On-Line or Print Journals?

You have just written a great short story. Let’s call it “Trucking.” It is, afterall, about the guy who picked you up in his truck while you were hitch-hiking in Chile. Though the story is funny and light-hearted, it goes deep into the characters’ minds and probes socio-economic conditions. In short, what you have in your hands is a work of literary fiction.

Now, what do you do with it?

In the old days (circa 2005), you would get a copy of Writer’s Digest’s Short Story and Novel Guide. You would scan the list of literary magazines and submit your story to your top five to ten journals, maybe places like The Paris Review or Glimmer Train. If these places rejected your piece, you would go back to your list and send out your story again. This time, you would submit to journals with a smaller circulation but which were still credible, places like Alaska Quarterly Review or Nimrod. If you got accepted, you’d dance around your living room. If you got rejected, you’d shrug and move on down the list until, eventually, you found a home for your work.

This is a perfectly reasonable way to go about your business. That is, assuming you follow the submission guidelines for the various journals, submit only to journals that accept simultaneous submissions, and notify them if your work is accepted elsewhere. And, assuming that you do enough research on the journals beforehand, so that you don’t submit “Trucking” to a journal that specifically wants speculative historical fiction or poems about jazz. If you do it right, this process is thorough and systematic, and if your story is as good as you think it is, it will likely find itself a home sooner or later.

But in the past few years, the literary magazine market has expanded so incredibly with the proliferation of dozens of on-line journals. In addition, the respect for on-line journals has increased, so that to have work published on the internet as opposed to print no longer carries the stigma that it once did.

So, given the many options available to you, what do you choose? Should you even consider on-line and print to be different categories? Or do you merely seek what’s reputable, regardless of the medium? What’s most important to you—prestige, visibility or being spotted by agents? Are you trying to build your resume or your readership? Can you do one or all of these at the same time?

The following are some things to consider when looking for a home for your latest, greatest, work of writing:

Visibility. If your goal is to cultivate a readership, that is more likely to happen on-line. When your work goes live, you can send the link to many people. Conversely, if you tell people you’ve published in a journal, how many will actually go to the bookstore to seek it out? Or make the effort to order the journal and shell out the money? On-line, your work is there for the taking.

Staying Power. If “Trucking” comes out in December 2009, it will still be easily accessible in 2012. With print journals, you’d have to order a back issue, and it’s not likely anyone would find it unless they actively sought it out. This is changing, as more journals post their archives and current contents on-line, but not every journal does this now.

Being Caught in the Act. Greater visibility may not always be desirable. If you never told your parents that you went to Chile and hitch-hiked, they might learn more about you than you’d like. Issues of writing about people you know, satirizing life at your office, or revealing deep parts of yourself become more pressing when you publish on-line. For better or for worse, anyone can find your writing in a Google search. Before publishing on-line, you’ll want to make sure you’re comfortable with the material’s exposure, more so than you likely would with a print journal.

Self-Promotion. Reading on-line is a much more fluid, integrative process than print reading. In your bio, you can link to your web page, or other places where you’ve published, and a reader can quickly, easily learn more about you. Readers can also contact you, and are more likely to do so. Many writers say that getting published on-line has generated emails from enthusiastic readers, and these dialogues have been tremendously rewarding.

Where Agents Fear to Tread. For some writers, the goal of publishing in a journal is not to cultivate a large audience, but to get the attention of one specific person—a literary agent. For such a writer, it makes sense to seek publication in top tier journals (agents generally pick from the best of the best.) Though there are highly reputable on-line journals and many agents do mine these for talent, it still seems that agents mostly make their selections from print journals.

The More, the Merrier. It can all come together though. If you publish “Trucking” in Glimmer Train¸ an agent who loves your story might then Google you. If s/he discovers other work that’s on-line and likes what s/he sees, this can be beneficial for everyone.

Why not just have a blog? Yes, if someone Googles you, your blog would also show up, and an agent could see more of your work there. But just like publishing your novel through a reputable publishing house shows that someone has screened and approved of your work before publication, publishing through an on-line journal gives your piece an added stamp of approval. Anyone can have a website or a blog. But publishing credits show that you are serious and hard-working, other people value your work, and you approach your writing in a professional manner—all traits that agents regard highly.

Are you Super Duper Creative? Writing a story or a poem is pretty cool. But have you ever wanted to read your story out loud to an illustrated clip of cartoon sequences? Or have a local chorus sing your poem alongside animation? On-line journals create more opportunity for not just one, but several creative powers to co-exist. Visit Electric Literature to see how these editors are doing story-telling in truly innovative ways.

Want to see your work in Korean? Getting published on-line does create some sticky copyright issues, which may be worth consideration. Some writers are shocked to find that their work has been taken off a web page and translated into several different languages without acknowledgment. You might be flattered if this happened to you. Or you might not like it at all.

Want Students to Share Your Work in Class? On the other hand, when a professor tells her students to find a good short short story they like, nowadays students will look almost exclusively on-line. If you have a short short published on a website, it could get passed around a classroom and be discussed, or printed out and hung on some struggling writer’s bulletin board somewhere. Many on-line journals, however credible, get thousands of hits a month, which means your work has a greater potential to find curious readers and also inspire.

So, how do you determine which on-line journals are reputable? How do you find the absolute best home for your piece? The answer is the same as it’s always been: Homework. Research what’s out there. Choose a few journals–on-line and print–that publish work you admire. Read reviews of on-line and print journals at places like Newpages.com and TheReviewReview.net. Remain open-minded about the possibilties for your work and the technology that’s available to you.

And most importantly, don’t forget: Before you submit your work anywhere, take a deep breath and pat yourself on the back. You wrote something wonderful.

Originally appeared on Beyond the Margins March 17, 2010.

August 12, 2013

Resources for Writers

All writers seeking agent representation, story, poetry, and/or novel publication rely on resources from which they gather information about the publishing industry. As a writer in the all-of-the-above category (sans poetry), I generally return to the resources that have served me well regarding information about agents, publishers, literary magazines, online magazines, and contests.

As a public service to writers new at the publishing game, and to introduce seasoned vets to resources they may not be aware of, the following is my list of favorite go-to resources:

Poets and Writers – website and magazine. A good place to start. The magazine is published bimonthly, and includes articles about the business of publishing, writing advice and author interviews, plus details about grants, scholarships, contests, hot markets, and MFA programs. The March/April 2010 issue features coverage of the Vona Voices Workshop by Boston’s own Jenn De Leon, who I can say I knew when from a common Grub Street class we took a few years back. The P & W website boasts a free database of job listings, small presses, and lit mags.

Nathan Bransford. Formerly an affable agent with the Curtis Brown agency, and now an author and social-media exec, Nathan features a blog/database topics ranging from Do You Own Your Characters or Do Your Characters Own You? to Where do you go for Inspiration? He also hosts a writing advice database that answers questions writers may have about the many phases of the writing and publishing process.

Duotrope’s Digest. “A free writers’ resource listing over 2825 current Fiction and Poetry publications.” Duotrope’s database is easy to search and offers a submission tracker for registered users. Search results show a current description of each publication, which genres and themes publications are looking for, requested work lengths, available pay scale, and links to publication websites.

Query Shark. Endlessly entertaining and informative. The conceit is simple: writers submit their query letters and an established literary agent critiques them, giving reasons why they may or may not elicit requests to see more work. The strong-willed submit a revised query to find out what progress they’ve made. Learn all the rookie mistakes, and see what elements determine the Holy Grail of queries—the positive response.

Miss Snark. Almost three years dark, this anonymous agent’s blog is still available and full of timeless, snarky advice.

Guide to Literary Agents, by agent Chuck Sambuchino. A great literary agent and agency resource. For example, one ongoing column features posts about authors and what they went through to get an agent. There’s helpful information about how to find agents for a particular market; for example, Christian, romance/erotica, poetry, and nonfiction. My favorite posts concern new agents, because many are more open to taking on new or untried clients.

Writer Beware. So, you’ve finished your first novel and you’ve got an agent’s attention. Before you sign with the agent, check out this website which posts alerts and documents scams regarding shady publishers and agents. Sure, 99% of agents/publishers play nice, but there are those that want to make a stealth buck off of dreamy-eyed writers. Search here first before you sign a contract.

What resources do you use? Which websites are crucial to your publishing experience?

Originally published on Beyond the Margins on March 20, 2o1o

August 11, 2013

Down the Rabbit Hole of Research

You probably know the feeling. You might be stuck on something in your manuscript, or you might be flying through a section, when you hit a place that needs…research. What do you do?

If you’re like me and many other writers, you open up a new tab on your browser and start furiously typing in search terms. Or you head to your reference books and start flipping pages. Woe be unto you if you actually decide to leave your desk and head to the library…that’s when you know you’ve truly gone down the rabbit hole of research.

Who knows when you might return? Rabbit holes lead to rabbit warrens, complicated places that sometimes connect but often do not, leaving you at a dead end after hours spent looking at documents, images, and more. I say “spent” and not “wasted,” because all of us have anecdotes about the time when what seemed like a fruitless search yielded the one nugget of information that made a scene sing or tied up an important plot point.

However, just as often, research done at the wrong time or to the wrong degree leads too far away from the page, which is where we truly want to be. I was reminded of this when my friend and fellow writer Michele Filgate posted on Facebook about a conversation she had with the novelist Matt Bell during an event. She told him that she was working on a novel but kept getting sidetracked by research. Bell urged her to avoid research entirely until she has finished half of her manuscript. Then, and only then, he said, should she start looking at details and information to fill out the pages.

That’s sound advice — if it works for you. I, for example, find that small bouts of research help spark new scenes, as long as I control the amount of time I spend on them. Out comes the faithful kitchen timer, set for ten or twenty minutes. Even if I’m in the middle of a juicy lead on something, I go back to my manuscript. Yes, it’s sprinkled liberally with “TKs” (the journalistic shorthand for “facts to come”), I just keep going. I’ve been following this routine since I began my latest work in progress, and I’m now at 50,000 words. Works—-for me.

Other novelists (the published kind) follow routines as individual as their writing. Dawn Tripp, whose latest release is Game of Secrets, says, “I find that how I manage research is integral to how I build a story. For me, I have to have a keen, visceral sense of the world of the story I am writing into, without allowing details of that world to clutter or slow down the drive of that story as I am drafting it onto the page.”

Tripp’s solution is to “read and read and read” for a few months before she begins writing, and to take notes. “Other than that, during this period of time, I do not write at all,” she says. “That immersion research is, for me, crucial to absorb the essence of a culture, place, and time.” After that, she puts all of her research books away and does not open them again until she’s finished a complete draft.

Tripp’s solution is to “read and read and read” for a few months before she begins writing, and to take notes. “Other than that, during this period of time, I do not write at all,” she says. “That immersion research is, for me, crucial to absorb the essence of a culture, place, and time.” After that, she puts all of her research books away and does not open them again until she’s finished a complete draft.

Other novelists have a more “pick and mix” approach. Jessica Keener, author of Night Swim, says that after she’s written a first draft she does the bulk of her research, calling and emailing and meeting people who might have answers, as well as using the Intenet. “I may not use 80 percent of the material I harvest, but it feels important to have this stuff available if I need it.” However, Keener also admits that research isn’t her particular rabbit hole: “My rabbit hole is usually around plotting.”

One of the toughest things that happens to all writers is not knowing which details will be important.

“That’s why I’m always researching as I write,” says best-selling novelist Caroline Leavitt. But Leavitt makes an important observation, which is that when you know that a particular detail will be crucial but you can’t find it, even after hours of research, hire help: “I recently did this for the first time because I needed to know what they used instead of crime tape in the 1950s,” she says. “The answer? Wooden sawhorses and rope. My best research tool for those kinds of questions was, believe it not, Facebook.”

Facebook as research tool? Don’t tell Zuckerberg. Or surely a premium will be put on our querying posts.

Originally appeared on Beyond the Margins March, 2013

August 8, 2013

Earning A Reader’s Time

By Randy Susan Meyers

Most readers have more choices than time, so here’s the question: why should they spend that time with you? My advice? When you ask that question, be hard on yourself.

A few weeks ago, I led a discussion about the covenant between readers and writers with a group of (non-writer) readers and writers. I jump-started the discussion using thoughts from the above link (a post I’d written) and Salon’s controversial piece: A Reader’s Advice to Writers. (The piece elicited comments that ridiculed the idea of writing for the reader—shaking their online heads in sorrow at what they considered advice on how to dumb-down one’s writing)

No one should tell a writer what to write, but should authors listen to reader’s recommendations regarding how to make their books exciting and interesting? After all, advice streams in from MFA programs, workshop leaders, conferences, books, and magazines. What about smart and constant readers; don’t they get a vote? What would they like to tell writers? In the workshop I led in Marshfield Massachusetts, when I asked, “What do you want to tell writers,” they said the following:

1) “Please don’t fancy it up. Use the word red for red sometimes. Walk, don’t perambulate. Have your characters ‘say’ things, don’t let them ‘opine.’”

2) “Don’t introduce too many characters in the first chapter. If I can’t keep track of them, I’ll close the book.” (My addition: if character’s names start with different letters, it’s far easier for the reader to track them.)

3) “Avoid long pointless descriptions of settings—they make me feel like the writer is just trying to show off that they can do it.”

4) “What makes me keep reading is when something bursts inside me—something I can recognize in myself. I respond when I sense the writer has revealed a deep truth.”

5) “Get to the point. If the book starts with pages and pages of rambling, I put it down.”

I agree from both the reader and writer sides of my brain.

Our books must be the very best we can make them. We can’t slough it off on our agent or editor’s improvements. It’s us. We can’t make them ‘good enough or ‘I’m done, and that’s it!’

Never try to fool yourself. If it doesn’t ring right to you, it sure won’t ring for the reader.

Learn and practice good craft and then incorporate those methods. Know the rules before you break them. Read, read, and then read more. Read broadly, read in the genre you love best, read about writing, and read beyond your comfort zone. Strip down what you read. Figure out why a book worked for you, or why it didn’t.

Whatever you write do, write it honestly and well. Choosing a genre doesn’t mean choosing mediocre vs. excellent. There is terrible literary fiction out there and fantastic vampire romance. Being a snob doesn’t equal interesting. Never ‘write down’ thinking you’ll make a buck.

Passion shows and passion attracts. Whatever reader you’re courting, open up those veins. The best writing comes when you’ve accessed the hidden places. Provide your readers with pops of recognition. Worry less about saying it fancy and more about exposing the dark corners of the soul.

Originally appeared on Beyond the Margins March 23, 2010

August 7, 2013

My Father’s Silent War

By Laura Harrington

My father never talked about the war. Even when we went to a commemorative event in France where he had been stationed in 1944, just north of Paris. An event with all the pomp and circumstance of town bands, bunting, an exhibition in the local church created by school children, including models of the Martin Marauders my father had flown, a mayor’s speech and champagne reception, military brass, the American Embassy attache, and an outdoor luncheon. Even when we stood on the A-71 airfield, seemingly abandoned, still in the countryside, where his planes had taken off and landed. Even as we looked around, with the handful of other American Veterans, trying to figure out where the commissary and their tents had been, the tents they’d lived in through the coldest winter in a century, which made my father hate even the idea of camping forever after.

My father was a navigator/bombardier in WWII. With his crew, he flew dozens of missions into Germany. From my mother I learned that he enlisted in the Air Force so that he wouldn’t have to see the people he was killing, which he knew he couldn’t do. Family lore has it that he ate carrots until his skin started to turn yellow in order to pass the eye exam for the Air Force. At 26, recently married, with a stepdaughter and a new baby, he was considered the old man on his crew.

When I finally got old enough to be interested in my father’s life and asked him about the war, he would tell me stories that made him laugh. Stories about the guy who snuck his French girlfriend on base in the back of a supply truck. “He had her living with him in his tent. Cooking for him!” Until somebody higher up heard about it and sent the girl packing. Stories about the guy who was a genius at “scrounging” stuff. “He could find anything: firewood, food, liquor.” He especially liked the girlfriend story. The audacity of it. The spirit.

Not one word about flying, flak, losing crew members, friends, what he faced every time he climbed into that plexiglass bubble under the nose of the plane, crawling past the pilot and co-pilot, having discarded his sidearm because it kept getting caught on the pilot’s seat, knowing there was no way out for him if they were hit. Not a word about the killing cold they endured at 15,000 feet. When pressed he’d say that he would memorize every map for every mission, so that if they were shot down, they’d have a prayer of finding their way out. I could never bring myself to ask how many navigator/ bombardiers actually lived through crashes, as it seemed impossible to me.

Not one word about flying, flak, losing crew members, friends, what he faced every time he climbed into that plexiglass bubble under the nose of the plane, crawling past the pilot and co-pilot, having discarded his sidearm because it kept getting caught on the pilot’s seat, knowing there was no way out for him if they were hit. Not a word about the killing cold they endured at 15,000 feet. When pressed he’d say that he would memorize every map for every mission, so that if they were shot down, they’d have a prayer of finding their way out. I could never bring myself to ask how many navigator/ bombardiers actually lived through crashes, as it seemed impossible to me.

My father survived the war when so many others didn’t. The mid-range B 26 bomber, the Martin Marauder, was known as “The Widowmaker.” But he came home and suffered for years from what was then called battle fatigue, what we now know as PTSD. My siblings remember him waking from his nightmares, screaming. I wasn’t born yet, so have no memories of my own. Still, I tried on several occasions to learn more about this time in his life. He would never answer and I found it difficult to press him; it felt like an invasion of his privacy. I look at pictures from those years and can see the hollows under his eyes, his clothes hanging loosely on his shockingly thin frame. My brother remembers my mother saying, “The fellow I married didn’t come home from the war.”

In 2002 all the surviving airmen who had been stationed in Clastres received an invitation from a group of French citizens. They had organized a memorial and a celebration to commemorate those who had served in the war. Some of the organizers were ordinary citizens, some had served in the resistance, some were young men, amateur pilots, one in particular who said, “I can never forget that these men left their homes and their families and travelled across the ocean to help people they didn’t even know.”

My father was 84. I asked if he’d like to go, and if I could take him. He surprised me by saying yes. He had never belonged to the VFW or to the American Legion. It was only at this point, very late in his life that he was moved to re-visit his past. We agreed to meet my oldest brother in Paris and travel together, something we had never done before. We would visit Normandy and the landing beaches, make a circuit of the Somme River Valley, and end our trip in Clastres for the commemorative events.

I thought to myself. Now. Finally. We will talk about these things.

At the American cemetery in Normandy other visitors realized that my father might be a veteran. Several approached him eagerly, wanting to ask him about the war. His answer was always the same, as he looked out over the rows and rows of graves: “Nothing like this should ever happen again.”

In some ways, I know now, I was hopelessly naïve, wanting my father to “share his stories.” The gut-wrenching truth, something that any soldier will tell you, is that you can’t talk about it. For several reasons. First, for my father, a desire to protect me. Second, the minute you make it a story, you’ve started to lie. Third, anyone who does gas on and on about what happened, probably wasn’t there.

You’d think that would be that. My father’s privacy respected, my curiosity put to bed. Instead, it has been like any family secret, growing more and more fascinating the longer it remains out of view.

Why have I written about war so extensively, from so many points of view? Yes, I’ve been inspired by peace activists and yes, I’m fascinated by history in general and the history of war in particular. But what is the emotional hook that keeps me coming back to this fertile territory, to excavate these stories and finally, in my first novel, to write directly about a father gone to war and the effects of the war on those left at home?

My father is gone now. I have my parents’ letters from the war years, a flag, a few issues of Stars and Stripes, a linen map. As I hold these letters in my hands, potent reminders of my parents’ lives, their hopes, their fears, their voices, I try to imagine my way into the heart of their experience, and through them, into the lives of all families sacrificing a loved one to a war. For even if they come home, we now know, they will be forever changed.

This Memorial Day as I think of my father, I am grateful that he taught me such a profound respect for quiet. In the midst of excited children, waving flags, the sound of marching feet and high school bands, I will find myself thinking of my father’s silence, both its limitations and its extraordinary strength. He showed his devotion not by spilling his secrets, but by shielding me from them. In addition, he sparked a lifelong curiosity and gave me the most profound gift you can give a writer. He taught me to pay attention to all that is not said; to be alive to the mysterious silences that surround us. And he inspired me to try to give voice to that silence.

Originally appeared on Beyond the Margins May 27, 2013

Chris Abouzeid's Blog

- Chris Abouzeid's profile

- 21 followers