Chris Abouzeid's Blog, page 32

October 1, 2013

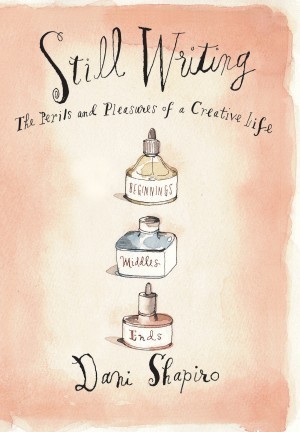

Dani Shapiro is “Still Writing”

Yesterday, noted author and writing teacher Dani Shapiro released a new book called Still Writing: The Pleasures and Perils of a Creative Life. I spoke with Shapiro (who, I am proud to say, was my workshop instructor at the 2011 Sirenland Conference) by phone from her home in Connecticut because I wanted to hear from her about why Still Writing is not, and was never intended to be, a writing manual.

Yesterday, noted author and writing teacher Dani Shapiro released a new book called Still Writing: The Pleasures and Perils of a Creative Life. I spoke with Shapiro (who, I am proud to say, was my workshop instructor at the 2011 Sirenland Conference) by phone from her home in Connecticut because I wanted to hear from her about why Still Writing is not, and was never intended to be, a writing manual.

“First of all, there are many books on craft out there,” she said. “There are tools and rules and aphorims galore, but really–you can have this whole vast toolbox of tricks, but without the bigger picture, it’s just a duffel bag of stuff.” What does Shaprio mean by “the bigger picture?” “What is really takes: Without courage, without persistence, without the ability to withstand rejection, without the ability to be alone, none of the technical stuff matters.”

Shapiro maintains a blog on her website and says she always knew she wanted to blog about…writing: “It’s where I live; it felt like a well I could keep drawing from;” but she didn’t know, when she began to publish posts, that “what I really wanted to write about was What It Takes. What does it take to sit down and do this thing? I wanted to write a book that would be, in a sense, like a friend, that would really feel like a companion holding other writers’ hands in the wilderness.”

Still Writing is divided into “Beginnings,” “Middles,” and “Ends,” a delightful conceit that not only gives structure to Shapiro’s strand of memoir that meanders through the book, but also provides a wonderful motif for the Barry Blitt-designed cover. Within those sections are pieces with names both enigmatic (“Shimmer,” “Break”) and concrete (“Smith Corona,” “Spit”). These pieces read as if Shapiro is sitting at a beautifully appointed desk on a sunny, still day, holding up various bits and bobs of her life for a combination of retrospection, introspection, and clarification, sharing what has worked for her in hopes that it might help others on their own paths.

The reason this author–who has published both memoir and fiction to acclaim–believes that writers need more companionship and fewer rules has to do with the fact that rules can only take you so far in any artistic discipline. “It’s sort of like, for a dancer, the physical instrument has to be absolutely in tune before any art can be created. But for a writer, “tuning up” can create a false sense of security, and I think that’s because some of the best books, those that are most indelible and groundbreaking, are books that wind up breaking the rules. I’m thinking of Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights–there’s absolutely no plot in that book. If you are a writer who has followed some manual that meticulously instructs you in how to ‘create’ a plot and you read that, what will you take away?”

Shapiro is convinced that craft cannot be separated out in the way it is in many “books on wriitng.” A lot of these, she notes, “are full of alwayses and nevers, and those ignore books like Hardwick’s–like Jenny Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad–like Jess Walters’ Beautiful Ruins–books that break the rules not for the sake of breaking them, but for the sake of honesty and truth and beauty.”

Who does Dani Shapiro rely on then, in her own continuing creative life? “I keep Annie Dillard near me, Virginia Woolf, too, as companions on the journey. Whenever I give a talk to a large group of women, I ask those who were awake the previous night at 3 a.m. to raise their hands. Inevitably, three quarters of the audience will do so and we all look at each other in a sort of bemused recognition. It’s very comforting, this awareness that in whatever we do, we’re not alone.”

“That’s what I want to provide for writers in this new book–a sense of awareness that there’s another way of thinking about what is often a very solitary life. Yes, it’s you and you’re scaling that mountain–but it’s also, in a way, communal. It’s my tribe.”

To Establish a Writing Routine or Not, That is the Question

Guest post by Charles Garabedian

I usually take my writing projects with me when I travel, like the time last spring when I stuffed a carry-on with my manuscript and flew to Durham, North Carolina in time for a family wedding. My home away from home over those twenty-four hours consisted of a spacious, clean, and nicely decorated hotel room with a floor-to-ceiling window overlooking manicured gardens and a crystal clear swimming pool surrounded by planters of geraniums and impatiens. The room and its views couldn’t have been more pleasant—a beautiful ambiance to stimulate ideas for scene revision and plot pacing, I thought.

Boy, was I ever wrong.

The morning after the wedding, I set up my laptop at the desk over by the window, and sat down ready to revise a scene set in 1920’s Boston. Instead of keeping focused on the work, my attention ended up wandering from the computer screen to the fly buzzing against the window, to the birds dipping into the pool, to the hum of the air conditioner, and to the groundskeeper watering the flowers and shrubs.

I finally dragged my eyes to the manuscript, poised my fingers on the keyboard, and painfully sensed the seconds elapsing to minutes before I finally struck a letter. The few sentences I punched out made no sense whatsoever, and I quickly deleted the mess. I couldn’t think of anything to blame for my lack of concentration other than the distractions around me in a place that wasn’t my usual writing environment. I didn’t have any of my creature comforts with me—my writing props—that have become an integral part of my writing routine back home.

What is my routine, you might ask? On Mondays, Wednesdays, and most weekends, I begin writing at six o’clock in the morning and finish by eight, because my mind typically becomes mush after two hours of concentrated work. I need a cup of coffee next to me, freshly brewed, to sip as I write, and also need to settle myself at a table or counter in a relatively noisy coffee shop like Starbucks or Boston Common Coffee. The process of tuning out the commotion helps me to center my thoughts, as crazy as this sounds. The routine of starting at six a.m. with a cup of coffee at a café, helps inspire and motivate me to revise chapters or to begin writing fresh drafts.

Joyce Carol Oates said, “I write every day and I’d like to get writing as soon as I can, sometimes even before seven o’clock. My study’s up there, and it’s very quiet then. I look out the window at the garden and I have a cat who usually comes in with me and wants her breakfast actually.” (1)

“I am a completely horizontal author,” Truman Capote said. “I can’t think unless I’m lying down, either in bed or stretched out on a couch and with a cigarette and coffee handy. I’ve got to be puffing and sipping. As the afternoon wears on, I shift from coffee to mint tea to sherry to martinis.” (2)

Stephen King stated, “Like your bedroom, your writing room should be private, a place where you go to dream. Your schedule—in at about the same time every day, out when your thousand words are on paper or disk—exists in order to habituate yourself, to make yourself ready to dream just as you make yourself ready to sleep by going to bed at roughly the same time each night and following the same ritual as you go.” (3)

Ian McEwan talked about his twelve-foot writing table and the giant computer screen, books, and papers on top. He said, “I’ve always believed that it’s important to turn up at this desk, whether you feel like it or not, whether you have ideas or not. You’ve got to have the work ethic that makes you show up. When I’ve got a piece of work going, I like to be there about half past nine. It’s very important to close off all those avenues to the outside world like the Internet, the emails, the telephones. I switch all those things off and try and get a solid bit of work done before lunchtime. And a solid bit of work for me would be somewhere between five and eight hundred words.” (4)

And John Grisham said in a December 9, 2011 interview, “Once there’s a deadline for a book I start each morning at 7; same desk, same cup of coffee, same everything. I work for four hours. It’s quiet, private, there are no phones, faxes, Internet. On a good day I’ll do eight to 10 pages; on a slow day, five or six.” (5)

Finally, Toni Morrison stated, “I, at first, thought I didn’t have a ritual, but then I remembered that I always get up and make a cup of coffee while it is still dark—it must be dark—and then I drink the coffee and watch the light come…And I realized that for me this ritual comprises my preparation to enter a space that I can only call nonsecular . . . Writers all devise ways to approach that place where they expect to make the contact, where they become the conduit, or where they engage in this mysterious process. For me, light is the signal in the transition. It’s not being in the light, it’s being there before it arrives. It enables me, in some sense.”

Morrison went on to say, “I tell my students one of the most important things they need to know is when they are their best, creatively. They need to ask themselves, What does the ideal room look like? Is there music? Is there silence? Is there chaos outside or is there serenity outside? What do I need in order to release my imagination?” (6)

For many writers, establishing a routine is a necessary piece to the process of writing. For me, it helps to focus my attention on what needs to be written. It sets the stage. It allows that comfortable moment of privacy between me and my characters, where the familiar setting and props allow thoughts to flow more easily from my mind to the paper or computer screen. There is no right routine, in fact many writers don’t have or need a set ritual before they begin to write. Do you?

Resources

1. Video posted by Kristina Budelis in The New Yorker online, June 25, 2013.

2. The Paris Review, 1957.

3. Stephen King, On Writing, (New York: Scribner, 2000) 156-157

4. Video interview with Ian McEwan, Ian McEwan On His Writing Process, posted on Knopf Doubleday.

5. Posted on Financial Times, December 9, 2011.

6. The Paris Review, Elissa Schappell interviewer, 1993

Photo by Liz Smith

Charles Garabedian

Charles Garabedian is a fiction writer represented by agent Carolyn Jenks at the Carolyn Jenks Agency. He has been a member of the Grub Street Writers’ Center in Boston for many years. His debut novel, Ivy House, was conceived during the center’s Master novel workshop mentored by New York Times bestselling author, Jenna Blum. Charles lives in Boston and enjoys playing tennis, kayaking, and spending time with family. Since 1993, he has been a pediatrician in Concord, Massachusetts.

September 30, 2013

Writer Sexism, Name-Calling and Dismissals: Which Side Are You On, Guys?

Like a compass needle that points north, a man’s accusing finger always finds a woman. Always.—Khaled Hosseini

A few questions:

Why do some folks get in such an uproar when women simply ask for a fair shake, equal footing?

Why does anyone think women writers are exempt from institutional sexism? The Mad Men era was not long ago. The 19th amendment to the constitution, giving women the right to vote, was only ratified in 1920. Help Wanted ads were segregated by gender into the seventies.

Why are folks surprised when women don’t find screenwriter Seth Macfarlane satirical when he dismisses the breathtaking film The Accused, in which Jodie Foster plays the victim of a horrific gang rape, by noting that he got a look at a Foster’s breasts.

Rage against incidents like this is comes out time and again—so why do male writers who insult women writers continue to act surprised when there’s a backlash? Why do they then blame their words on (choose one) the interviewer, the women-without-senses-of-humor, or the cabal of angry women-commercial-writers? Does this come from the same instinctual place of those who, each time I write about domestic violence, whine and scream “women do it too!” as though, in fact, two wrongs ever did make a right?

Does it stem from the reasons listed in the comic-truth of “5 Ways Modern Men Are Trained to Hate Women?” where the author divulges:

“women took it all away .. . This is why no amount of male domination will ever be enough, why no level of control or privilege or female submission will ever satisfy us. We can put you under a burqa, we can force you out of the workplace — it won’t matter. You’re still all we think about, and that gives you power over us. And we resent you for it.”

Historically, white guys always had the better shot at topping the ‘smart writer heap.’ Writers who should know better brag (usually including—wryly—the words “I know this isn’t politically correct”) about reading only “dead white guys,” as though proving their can’t-be-beaten-out-of-them intellectual prowess. (I often wonder whether these writers would be okay if only dead people bought their books.)

Dismissive remarks against women writers make sense in the context of men (consciously or not) guarding their places in line, those hoping to enter the realm of becoming a ‘canonical writer.” Eons of privilege afford men a better shot at early admission to the canon. Who among us wants to lose power? Better to dismiss the idea that the power differential exists, or to be intellectually snide, than give up one’s that upper rung on the literary hierarchy. Power threatened engenders hostility, or, worse, outright hatred, as seen in Michelle Dean’s list on Flavorwire’s of “7 Breathtakingly Sexist Quotes by Famous and Respected Male Authors,” which includes these words from Norman Mailer: “A little bit of rape is good for a man’s soul.”

And yes, that a male writer exploring relationships and family is likely to be considered groundbreaking and a woman’s book on the same territory is called ‘women’s fiction,’ is a part of the equation. Can we equate snide comments, a pink glittery book cover vs. a moody shot, to violence against women and the recent war against women? Maybe yes, maybe no, but we can plug it right into the canon of micro-indignities which keep women from recognizing that they are entitled to half the sky.

Each comment, each dismissal of reality (see the Vida Count if you want more facts and figures) is another slice in the death of a woman writer’s esteem by a thousand cuts. Who’s holding the knives and why?

There is The Bragger:

In an interview with award winning novelist, David Gilmour, who also teaches literature at the University of Toronto, Gilmour says:

“I can only teach stuff I love. I can’t teach stuff that I don’t, and I haven’t encountered any Canadian writers yet that I love enough to teach. I’m not interested in teaching books by women. Virginia Woolf is the only writer that interests me as a woman writer, so I do teach one of her short stories. But once again, when I was given this job I said I would only teach the people that I truly, truly love. Unfortunately, none of those happen to be Chinese, or women. Except for Virginia Woolf. And when I tried to teach Virginia Woolf, she’s too sophisticated, even for a third-year class. Usually at the beginning of the semester a hand shoots up and someone asks why there aren’t any women writers in the course. I say I don’t love women writers enough to teach them, if you want women writers go down the hall. What I teach is guys. Serious heterosexual guys. F. Scott Fitzgerald, Chekhov, Tolstoy. Real guy-guys. Henry Miller. Philip Roth.”

All this pitting of sex against sex, of quality against quality; all this claiming of superiority and imputing of inferiority, belong to the private-school stage of human existence where there are ‘sides,’ and it is necessary for one side to beat another side, and of the utmost importance to walk up to a platform and receive from the hands of the Headmaster himself a highly ornamental pot.— Virginia Woolf

Often seen? The: “Oh, yeah? Well it’s worse in other places!” fellow:

Frank Bruni wrote a thoughtful NYT piece regarding “Sexism’s Puzzling Stamina,” reflecting on, “. . . all the recent reminders of how often women are still victimized, how potently they’re still resented and how tenaciously a musty male chauvinism endures. On this front even more than the others, I somehow thought we’d be further along by now.”

Jonathan Franzen responded to Bruni (who referenced VIDA’s research on the disparity of women’s work being highlighted in the media) with a letter to the editor which included following:

“There may still be gender imbalances in the world of books, but very strong numbers of women are writing, editing, publishing and reviewing novels. The world most glaringly dominated by male sexism is one that Mr. Bruni neglects to mention: New York City theater.”

It is puzzling why a famed writer wastes time defending statistical disparity by saying “it’s worse in other fields.” Really? What is behind the odd defensiveness?

When all else fails, there is always the role of The “Name-caller”

Jeffrey Eugenides, given the chance (in the midst of a swell of coverage of his newly released novel The Marriage Plot) to reflect on gender disparity, responds to the interview question “Would “The Marriage Plot” have had a different cover if it was written by a woman? Something pink or frilly or less serious?” with:

“As a male you can never know and you’re not supposed to talk about it. But I have lots of female literary novelists who I don’t think would agree. I’m friendly with Meg Wolitzer and she was a big fan of “The Marriage Plot,” and she wrote something about this, and especially about the treatments of the covers. I wondered about that, if that might be true, if women get treated differently in the way that their covers are marketed. You know, it’s possible.

To me, it was a little bit … I didn’t really know why Jodi Picoult is complaining. She’s a huge best-seller and everyone reads her books, and she doesn’t seem starved for attention, in my mind — so I was surprised that she would be the one belly-aching. There’s plenty of extremely worthy novelists who are getting very little attention. I think they have more right to complain. And it usually has nothing to do with their gender, but just the marketplace.”

Belly-aching? Nothing to do with gender? Has he seen the numbers? Has he heard of the pink ghetto of women’s books on domestic drama vs. the treatment men get writing on the same topic? Does he know about the ‘cover flip?’

Why the denial of reality?

And one can always become a “Name it and it shall be true!” declarant

VS Naipaul, a winner of the Nobel Prize for literature, considered one of the greatest British writers of his generation said in an interview that no woman writer could be his literary equal; that Jane Austen’s “sentimental sense of the world” made her his inferior; “I read a piece of writing and within a paragraph or two I know whether it is by a woman or not. I think [it is] unequal to me.”

I’m not concerned with your liking or disliking me… All I ask is that you respect me as a human being.—Jackie Robinson

Chuck Wendig wrote an essay titled “25 THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT SEXISM & MISOGYNY IN WRITING & PUBLISHING, where he reaches out to other men with the words: “I hate to borrow a twee saying from our Masters at Homeland Security, but when you see inequality, it’s time to kick up some dust, time to throw a little sand. To borrow another twee sentiment: all evil requires is for good folks to stand by and do nothing. All sexism needs to thrive is for good people to do the same.”

Wendig recognizes that this is not a women-writer issue, literary-writer issue, commercial-writer, genre-writer or any-slice-of-writer issue: it is a writer issue. Perhaps I should paraphrase the tweet by K. Tempest Bradford, in response to a shower of sexism in the literary world of science fiction and fantasy:

“This would be a good time for the men who write science fiction who aren’t douchecanoes to step up and tell the other dudes to go to hell.”

Bradford’s call was well answered by Jason Sanford:

“We’re tired of your sexism and hate. Clean up or ship out. You’re holding back the genre we love. And it’s time for the men of SF to step up and also say this behavior is not acceptable.”

Thanks, Jason.

So, to borrow from Bradford: Can you help handle the gentlemen, guys? Your friends, daughters, girlfriends, wives, and mothers are wondering—which side are you on?

Deliver me from writers who say the way they live doesn’t matter. I’m not sure a bad person can write a good book. If art doesn’t make us better, then what on earth is it for. Alice Walker

September 26, 2013

Friday Faves

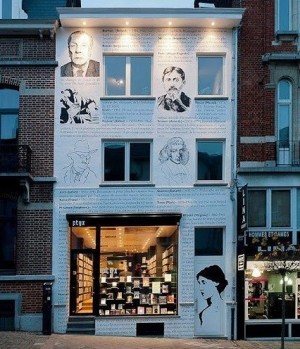

Librairie Ptyx, Brussels, Belgium

By Juliette Fay

Articles—some fascinating, some worrisome, some beautiful—culled for our wonderful Beyond the Margins readers from the vast galaxy of this week’s online verbiage.

Professor Says He Has Solved a Mystery Over a Slave’s Novel (New York Times)

“In 2002, a novel thought to be the first written by an African-American woman became a best seller, praised for its dramatic depiction of Southern life in the mid-1850s through the observant eyes of a refined and literate house servant. But one part of the story remained a tantalizing secret: the author’s identity.”

Whatever Happened to Book Editors? (Publishers Weekly)

Interesting perspective from an ex-industry-editor. Editors are being asked to do more and more, and actual editing is becoming a smaller part of their job.

Tough Guy Lit Prof: “I’m Not Interested in Teaching Books by Women” (Gawker)

Don’t miss the comment section – some pretty terrific retorts.

If you’re interested in the full article, it’s David Gilmour on Building Strong Stomachs (Random House). While it doesn’t quite compare with “I’m not interested in teaching books by women,” I also think this line is a bit of a Huh? “I know how to talk to a camera, therefore I know how to talk to a room of students. It’s the same thing.”

His apology (sort of) is here: Canadian novelist backpedals on sexism charge, is still sexist (Salon)

On a happier note: 30 Excellent Bookstore Windows From Around the World (Flavorwire)

Feast your eyes and mind!

[Image via, Flavorwire]

September 25, 2013

Letters from the Bookstore Manager

Dear Ms. Pennywise,

I am writing to thank you for your consistent patronage of Practically Perfect Bookshoppe and to touch base with you about one of your customer habits.When I review your account with us, I cannot help but be delighted with your frequent business! Why, in the past six months I see that you’ve purchased an average of 15 books a month. I also cannot help but admire your taste. For example, Forgotten Nose is one of my favorites of this year, and Nostradudas has not, in my opinion, received nearly the attention it deserves. As the book-buyer and the person in charge of staff favorites, your selections thrill me!

On a less happy note, I see that you have returned every book you’ve purchased from us within a week of its sale. This is indeed a troubling habit from our point of view. Are you perhaps not familiar with the public library? Here in Bluemuffin Hollow we have a main branch located on Privet Drive and branches on Cherry Tree Lane and Deckawoo Drive. I’m enclosing maps with the best routes marked – red for auto, green for bicycle and pink for on foot. I do think you’ll find the library to be a great resource!In the meantime, I’d also like to take this opportunity to notify you that we will no longer be able to accept returns from you here at the bookstore. Please imagine an emoticon using a colon and an open parentheses sign here. I cannot bring myself to use punctuation symbols in a pictorial fashion, but I do want you to know that this decision saddens me.

Best wishes for a happy reading experience, however you obtain your books.

Yours,

Mary Margaret Snowe

Dear Mr. Bowling,

I so much appreciate your regular attendance at our readings and discussions. As the event planner at Practically Perfect Bookshoppe, I can’t tell you how much it means to me to look out and see a full room! I’m sure you understand that we want the experience to be as enjoyable as possible for our patrons. Toward that end, we ask that guests make every effort to minimize noise. Cellphones, for example, should not be in use, as entertaining as these conversations may be at times. (I know we all got a smile out of your long discussion with your coworker about how to extract the jammed paper from your office printer!) More recently, we’ve had several complaints about the crinkle of cellophane packaging, the snap and pop of soda cans, and bodily noises such as belching that may interfere with the enjoyment of other patrons.

Sadly, those complaints are the impetus for this communication.I’m sorry to say, we will no longer be able to allow you to bring in your dinner from the fine fast food establishments nearby. In order to offset any discomfort this may cause you and others who may be hungry, we plan to offer small servings of low decibel foods such as angel food bites and quinoa sponge puffs.

Finally, I hope you will not find it untoward of me to mention that excessive eructation, borborygme and flatus can indicate conditions requiring medical attention. I’m enclosing information about the online support group “Gurgitators Anonymous,” as well as the names of several local board-certified gastroenterologists who are accepting new patients.

I do hope to see you our next event, a discussion of the book Kreme Puff – The Rise and Rise of the American Doughnut. I think you’ll especially enjoy this one!

Best,

Mary Margaret Snowe

Dear Ms. Hobson,

Magazines are such a delight, aren’t they? We at Practically Perfect Bookshoppe are proud to provide such a broad selection to our patrons. I myself admire the excellent visual quality of many of our photography magazines, the fun of celebrity tracking rags and the sheer panache of some of the art publications. I often find myself tempted to flip through a publication and read a short article or two without purchasing the magazine. (I will even confess that, on one occasion while perusing a magazine at a local newsstand, I extracted the strip sample of my favorite perfume, L’Air du Temps!) Alas, we are all so human.

However, my staff has brought to my attention a particular habit of yours, which is problematic. They report that during your daily visits to Practically Perfect Bookshoppe, you often settle into the red chair at the back of the store and peruse the magazines. They have noted that, in order to gain purchase of the often slippery pages, you tend to lick your index finger, then apply the licked finger to the page. Every page. I surveyed some of your favorite magazines and indeed noticed that nearly every page bears evidence of licking. (It disrupts the neat closure of the magazine, as I’m sure you’re aware.)

If you were to purchase these magazines, we would have no problem with the licking. Returning these to the shelf, however, means that we are offering a less than optimal item to patrons who come by later. Additionally, there are matters of hygiene, and as the person in charge of janitorial and health issues at Practically Perfect Bookshoppe, I cannot let this pass.

The ideal solution from our point of view, of course, would be for you to buy a magazine before you read it. If you cannot do so, we ask that you consider your fellow patrons and not allow your saliva to touch the pages of any unsold magazines. To help you with this challenging habit, I’ve taken the liberty of tucking a small bottle of a distasteful liquid named “THUMB LIBERATION” into the topmost corner of the magazine rack. As you may be aware, THUMB LIBERATION (and similar products such as THUCKIT) are designed to discourage thumb sucking. My thought: you can simply apply this to your index finger whenever you feel that temptation may get the best of you.

Here’s hoping we can make progress on this small roadblock!

Regards,

Mary Margaret Snowe

Mary Margaret Snowe is the manager of the independent bookstore Practically Perfect Bookshoppe, in the town of Bluemuffin Hollow. Ms. Snowe believes that an outstanding bookstore manager combines excellent customer service, love of literature, an appreciation for the bottom line, and perfect manners.

September 24, 2013

My Critique Partner, Myself

For almost a year now I’ve been communicating–sometimes daily, sometimes just weekly–with a friend and fellow writer about accountability. We both realized we weren’t finding enough hours in our days to write, and felt that regular emails detailing time spent on our works in progress would be helpful.

And they were. However, like most things worth continuing, our process has changed over the past twelve months. For a while, we stuck to emails that read, simply, “Sitting down now for two hours,” or “Got in 20 minutes before attacking my latest deadline.” But soon, we each found that we wanted to talk more about those two hours, 20 minutes, or even (on rare and happy occasions) several hours at a stretch. We instituted a weekly Skype chat so that we could commiserate bad days and celebrate good ones.

Most of you reading this–writers are like that–can guess what happened next. Yes, we started talking about our respective manuscripts. How could we not? There’s only so much you can say about effort in and of itself without adding backstory. “Today was really tough,” one of us might share. The responding “Why?” might bring out personal struggles, but just as often, it elicited craft conundrums and artistic revelations.

I recognized that it was time for us to start looking more closely at each other’s work, but I hesitated. Why? Because my critique partner has published her fiction–and I haven’t. She also teaches writing–and I don’t. I felt that it would be presumptuous of me to suggest that I might have any wisdom to share since it’s been such a relatively short time that I’ve focused on fiction.

Fortunately for my lily-livered psyche, my partner was the one to bring up critique sessions. Every week, we sent each other 12-15 page chunks of our work (she is wrestling with a memoir; I, withI a novel) and reconvened several days later for critiques and note taking. What a gift for me as a first experience with regular, focused attention on my writing, as my published partner is wise, witty, and thoughtful. While she clearly understood that this was my first draft and had lots of holes in it (big, big holes, sometimes), she never treated my work as “lesser” or unworthy of attention. She just rolled her sleeves up and dug in, giving me the respect she would any colleague.

Each week I looked forward to our calls, knowing that I’d learn more and more about my process, my strengths, and my mistakes. I felt as if I were taking a master class.

So what was the problem? Because there was one. Again, you writers may have guessed it from my title. The problem was me.

The problem was not that I worried about taking criticism, or giving it. The trouble was, I couldn’t see my own worth in the equation. I dutifully read and re-read my partner’s excerpts and made notes on them. But when the time came for me to offer up my comments each week, I felt the same way I did in my first grad-school seminar: unprepared and subordinate.

It took me a couple of months and half a dozen of these sessions to gather my courage and admit these feelings to her. She understood, but assured me that I was providing valuable feedback. It wasn’t until August, however, that my critique partner gave me a gift even greater than comments on my own work–she sent me a full chapter that she’d revised based on my notes.

The chapter, which had already been fascinating, was stronger. Tighter. At once more revelatory and more subtle. Mind you, I am not claiming that my feedback made it so, but it did encourage this woman, this writer, to delve back into her work and make it better.

Last week, the two of us decided that as we’ve reached a certain point in these works, we need to spend more time creating right now and less time critiquing. We’ll be meeting every other week for a few months, until we’ve got enough new material to speed up once more. But now I know that we’ll be on equal footing, not because of outer markers of success, but because of inner commitment. In learning how to critique someone else’s writing in a productive manner, I have learned something about how to continue creating my own.

Leaving A Literary Legacy: Who Will Watch Over Your Work?

When I met Alan, he was 62 and had been working on a novel for a little more than 20 years.

His book was ambitious. It was set during the civil rights movement and told through the voice of a church organist from Baltimore. Race, religion, urban blight. Everything came into play. He’d sent an early draft to some influential people and, at one point, won a prestigious novel-in-progress award.

But by the time he finished it, publishers were looking for more modern (and postmodern) novels. This was the era of Jonathan Safran Foer and his puckish crowd. Alan was older. He didn’t have connections; he wasn’t known. For 10 years, he shopped his 400-page manuscript around. Finally, last fall, Alan called me with the unbelievable news: His book had sold and would be published in fall of 2013.

The next call I got from him was the one where he told me he had pancreatic cancer. Six weeks later, Alan was dead.

And his book? Who knows. It’s a tough road to publish a novel, an even tougher road to market one (who among us doesn’t know that?). A friend made a deathbed promise to shepherd Alan’s novel through the process then had urgent family issues of his own and bowed out. The publisher who acquired it [for a ridiculously small advance] no longer lists Alan’s book on its “Coming Soon” page.

Like Alan, the story has disappeared.

It’s no coincidence that my husband and I drew up our wills around the time of Alan’s death. We’re at that age where the calls about illness come more frequently. Our doctors keep bugging us to get mammograms and colonoscopies. Plus, we’re motorcycle riders with failing eyesight. Mortality has become a clearer fact.

After we’d signed the traditional documents—will, power of attorney, health care directive—our lawyer asked what will happen to my literary assets and reputation when I die? Obviously, if my husband is still alive he can act on my behalf. But what if he dies before me? Who will make decisions about my work?

I shrugged. My books aren’t big enough, I told her. It doesn’t matter. The money coming from them is nominal. She was, rightly, frustrated with my response.

Never mind the possibility that my next book might become a bestseller…this was a question of reputation. Say someone plagiarized from one of my earlier works or used it in a way I’d object to. For instance, my first novel was about an autistic child whose parents treat him with marijuana and could be positioned by one of the kajillion snake oil salesmen who prey on families to help sell some false cure.

My husband, John, pointed out that my second novel, which focuses on a mathematical puzzle called the Riemann Hypothesis, could become huge if Riemann were to be solved. Highly unlikely but hey, the man loves me and he is a mathematician…Plus there’s the matter of what I will write from here on.

There’s precedent for John’s theory of posthumous fame. The list of authors whose books became international bestsellers after their deaths included John Kennedy Toole, Franz Kafka, Jane Austen, Sylvia Plath and Anne Frank. But in many of these cases, the writers died young and penniless without wills or even heirs. Who knows where the proceeds from their work have gone?

More recently, veteran Toronto writer A.S.A. Harrison died in June just weeks before her novel The Silent Wife came out and became the mystery hit of summer, capitalizing on the long tail of Gone Girl and spectacular early reviews.

Ultimately, I appointed a literary executor and sent my agent’s office a document outlining beneficiaries for the royalties I earn after death. The chance that anything I write will bring great wealth to my heirs is probably small. But I feel better knowing someone will watch over my words, insuring that the truths I told will at least be well tended and remain intact.

Also, I phoned Alan’s publisher to see what I can do to help bring his novel out in 2014.

Ann Bauer is the author of two novels, The Forever Marriage and A Wild Ride Up the Cupboards, and co-author of the culinary memoir Damn Good Food.

Her work has appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, The Sun, Redbook, Ladies Home Journal, ELLE Magazine and Salon.com.

September 23, 2013

Patience: Writers at Work

By Virginia Pye

Recently, as I’ve had the opportunity in lectures, workshops, and informal conversations to talk with writers about the work we do, I’ve been spotlighting the notion of persistence. This emphasis comes directly out of my own experience: twenty-five years ago I had my first novel represented by a top New York literary agent but only this year saw my debut novel—which happened to be my sixth written—finally published. My approach to writing has had, by necessity, an in-the-trenches feel to it. I doggedly went to my desk, day after day, year after year, producing my books and developing ever-thicker skin in response to rejection. But now, as I look back over the process, I think it may be wrong to single out persistence as the key quality needed by writers. Instead, perhaps the best emotional tone to have in regards to the writing life is one of relaxed patience.

The process of writing is uncannily like that of parenting: each book, like each phase in raising children, has particular challenges that seem fraught at the time, but eventually are gotten through. Just when you think you can’t possibly see the light at the end of the tunnel, something shifts. The solution to a seemingly insurmountable problem, whether for a child or a book presents itself, simply through the process. In writing, as in parenting, the trick is not to panic, but to wait it out—our books, like our children, have wills of their own and independent reasons for being. With continued engagement, the answers appear and the next step is ready to be taken.

Novel writing, though, resembles not only wrestling with obstinate toddlers or teens, but can be equally equated with carrying on a secret love affair: when we’re in the midst of it, nothing else matters. We’re utterly smitten with our own idea of the object of our affection. The affair is by definition secret because we’re the only one who can fully comprehend our beloved’s best qualities. But, when we’re done, and the love has passed, we can hardly recall what all the fuss was about. Each book demarcates a period in the writer’s life–a slow, extended passionate moment. Each is, in fact, a chapter. And then, when that chapter is over, it’s truly closed.

My first novel was a coming-of-age story about a girl who, coincidentally like me, grew up outside of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and who winds up inside the 1969 Harvard student take-over, her charmed life suddenly thrown into upheaval. The next novel showed a white, middle class, newly-married woman– like me in the 80s—who lives in New York City and discovers she’s HIV positive and must expand her sense of her life’s promise just when her life expectancy is shortened. My third novel was about a young wife and mother who, like me, lived in West Philadelphia. In response to a mid-life crisis, she decides to “do good” in her poor, racially-diverse neighborhood and winds up risking her safety and the safety of her children, although she eventually makes new friends and expands her sense of the world. I wrote each of these books immediately after the related chapter of my life had finished. Though they were largely not autobiographical, each was a way for me to make sense of the challenges I had faced. I have never been inside a student take over, don’t have HIV, and have never endangered my life or the lives of my children for a cause, but I invented fictional equivalents to my own experiences so I could thrash out my concerns from those times.

Not all fiction, of course, is as based—even in incidental ways—in autobiography. My debut novel, River of Dust, is set in China in 1910 and tells the story of an American missionary couple there who have their toddler child kidnapped by Mongolian bandits in the opening scene: needless to say, nothing of the sort ever happened to me. But the impetus of the story and the issues behind it do come out of my own concerns about American hubris in the world and the life-and-death realities entwined with motherhood.

Each of these books, I understand now, had to be written to move beyond their story. Each book had to be loved and coddled and then tossed aside when done—or, more honestly, when my agent at the time wasn’t able to sell it, although several of the earlier manuscripts still call out to me from desk drawers and I might just return to them someday. The market dictates the trajectory of a book in relation to readers, but the writer’s own tether to it can be entirely different. A writer can lose interest, or can continue to carry a torch for a project, regardless of whether it sells or not.

That process of falling in love with one’s own work is what matters, and then having great patience with it, just as we would with a child or a lover. The book we are working on will guide us to the next one, and then on to the next, and the next. It helps our writing process to respect the way our creative minds work over an entire lifetime. And to accept that writing is a way of understanding our lives, one chapter at a time.

Hopefully, we all have many books in us. Our job is to gently, patiently, coax them out, love them like mad when we’re working on them, wipe the spilled food from their faces, and still respect them in the morning, wrinkles, bad breath and all.

Virginia Pye’s debut novel, River of Dust, tells the story of an American missionary couple in China in 1910. It was an Indie Next Pick for May 2013 and The Washington Post called it “intricate and fascinating.” Her short stories have appeared in numerous literary magazines, including The North American Review, The Tampa Review and Failbetter. Her essays can be found at The Rumpus and The New York Times Opinionator blog. Please visit her at www.virginiapye.com

September 19, 2013

Zen and the Art of Withholding Information

Not too long ago I wrote a short story about a man whose son had died in a drunk driving accident. My hero played softball in the park, had coffee with a friend, and cooked food at a family reunion. Although he, Sam, was narrating his story in first person, never once did he allude to the fact that he’d had a teenage son who had passed away. Never did he give any indication at all that he was suffering from some incomprehensible trauma, or that he was carrying any guilt. The only reference to Sam’s loss came near the end of the story, when his other son asked him about the accident. Sam quickly got angry and said, “I don’t want to talk about it!” That was that.

Why did I think it was a good idea to write a story this way? For one thing, I must have thought I was being clever. “Oh!” my imagined reader was supposed to say at the moment of The Big Reveal. “How complex this character is! How little I understood of Sam’s past until now! How so very touching!”

Instead, the people who read this story reacted more with a confused, “Huh?” And, “Why are we only learning about his son now?” And, “Am I supposed to believe Sam is really grieving? (Because I don’t.)”

Why else did I write the story this way? Well, aside from thinking myself dashingly clever, I also suspect I was a bit of a coward. The mere thought of losing a child to drunk driving—how could I possibly let my mind entertain that? How could I even begin to articulate that experience? Though it might have seemed do-able when idly envisioning the story, in the actual practice of writing I was too terrified to inhabit Sam’s consciousness in any realistic way.

Thus, rather than go deeper into Sam’s inner life, I skirted around it. I told myself I was building up to The Big Reveal. I told myself that Sam was a stoic person who probably wouldn’t talk about his feelings. I convinced myself that he was so out of touch with his own emotions that he had blocked out all memories of his son. I did everything short of giving Sam amnesia, just to avoid having to write about this difficult issue.

Now, here’s the rub: In real life, it is true that we do not like to think about difficult parts of our past. It is true that if someone tries to talk to us about painful things, we might very well snap and say, “I don’t want to talk about it!” Certainly it’s true that people have all kinds of relationships with their emotions, ranging from in tune to out of touch, open to closed off.

Perhaps your protagonist is not the kind of person who blabbers about every feeling he’s ever had to anyone who will listen. Still, in order to convince your reader of his/her pain, in order to get your reader to empathize with him/her, you will not want to withhold key facts about your character’s life. Nor will you want to withhold major aspects of your character’s emotional experience. Take it from me–your readers will only feel cheated and confused.

Whatever your character’s level of connection to his/her own emotional life, here are some strategies I have found useful:

Have your character treasure some item/object/photograph.

Is there a certain item that can be used to cue the reader as to your character’s emotional state? Your character doesn’t need to go into a long monologue the second he sees a photograph. (That might be a little corny.) But a scene can be shaped around some treasured item. Suppose, for example, my character Sam carried a picture of his son in his wallet. Now suppose he lost his wallet. The person who finds it could see the picture and say, “Cute kid. How old is he?” When Sam snatches his wallet back, he’d say, “Thanks for returning it,” and storm off in agitation. The reader will feel Sam’s grief from this unsettling interaction around the treasured item.

Put your character in emotional-trigger situations.

Are there places that become emotional triggers for your character? If so, place your protagonist there as often as possible! In my own story, I missed a lot of opportunities to have Sam’s grief bubble to the surface. But one thing I did do right is to put him in a situation where he is driving his car in the rain late at night. He can’t help but think of his son here and everything he does and thinks is a clear signal to the reader that he is in a terrible state emotionally. He begins to scream at his friend in the passenger seat and insists that they pull over to wait out the storm. At the same time, he imagines if this was what it was like for his son when he lost control of the car. Additionally, the lights of oncoming cars glare into his eyes. Here Sam is forced to confront this painful part of his past, and he is in actual physical danger as he tries to drive through the storm. For this reason, my readers all agreed this was where the drama really got going. (Unfortunately, it was the last five pages of a thirty-five page story.)

Show your character’s unresolved relationships.

Are there people with whom your character still needs to make amends? Perhaps there was someone s/he wants an apology from. Maybe there is a person s/he feels that s/he still must apologize to, but doesn’t yet have the nerve. Or, as Anne Tyler does so beautifully in The Accidental Tourist, perhaps the unresolved relationship is the one right in front of the character’s face: the marriage that is shattered after the loss of a son. My own story would be much improved if I had thought more about Sam’s present relationships and the people with whom he must make amends.

Let your character obsess.

In fiction, nothing beats good old obsessive thoughts. While your character might not outwardly express his feelings, inwardly he might trace and retrace each moment of a particular event or experience, wondering what went wrong and what he could have done differently. You could show the disconnect between what he thinks and what he expresses by having him thinking about something but never admitting that such concerns are on his mind. Or, if you are writing in third person, you have the advantage of creating distance between the narrator and your character. Thus he might not even be fully aware of how obsessive he is actually being. If you want to see obsessive thinking executed to perfection, read Jonathan Franzen or David Foster Wallace.

Ultimately, your readers want to know exactly who your character is and what your character is going through. Intimacy with fictional characters is, afterall, one of the great scrumptious pleasures of reading novels and short stories. Most readers want to know every (relevant) thing that a character thinks, feels, and wants and why s/he thinks, feels, and wants it. As writers, it is our job to give them nothing less.

Writing Lessons: Giving Good Sex

by Kim Triedman

(Please welcome back Kim Triedman, writing with wit and wisdom about everyone’s favorite topic.)

So you’re having a little trouble?

Things don’t seem to be working quite the way they should?

You’re just not feeling it, and you don’t know what to do to make things better?

Well, relax. You’re not alone. We all have problems sometimes, and there’s nothing wrong with a little help from the experts…

Writing about sex can be daunting. We’re squeamish or we’re prudish or we’re terrified our mothers will read it. We bring not just the weight of our own social mores and emotional baggage, but also a healthy fear of failure. When these scenes go wrong, they go wrong badly, and they can bring a piece of writing down faster than a cold shower can…

Well, you know.

So for those of you out there who find you just can’t get things started, or find yourself petering out just when things are heating up, here are a few important strategies for making the most of your “sexual encounters.”

No, it’s not all about plumbing. While we all know that the thigh bone’s connected to the hip bone, writing about sex should not be a primer on what goes where. Sure your audience will need to have some sense of what’s going on in the live-action department, but for my money the best sex scenes often have little or nothing to do with mucous membranes. There is a place for anatomical detail: medical textbooks. As with film, or art, the most erotic renderings are often defined more by what is left to the viewer’s imagination than by what is included. A woman’s back, partially draped, captured in just the right light and just the right words, can be infinitely more evocative than a full-on blow-by-blow of who is doing what to whom.

Writing about sex is writing about the people having it. I’ve found that writing a scene involving sex is in most ways no different from writing a scene about grocery shopping or fly-fishing. It is, first and foremost, about your characters and how they reveal themselves through their actions. Yes, sex can be an intense and climactic event in any piece of fiction, but it is also a deeply human one – one which should give significant weight to the two (or three, or four) particular people having it. By this I mean the specific habits or inclinations or aversions that are consistent with – and extrapolations of – the characters you have already developed on the page. What is going on in her head while he turns away to take that cell phone call? Why does he always leave the light on, or off? What is it about his hands/neck/eyes that invariably throws her into (or out of) the mood? The more we recognize the people who are having sex as the characters we already know them to be, the more credible and evocative the encounter will be.

Sensual and sexual are two different things. When writing about sex, it is always a good idea to give the senses equal time. Yes, the reader will want to know what is going on in the bedroom/bathroom/boardroom, but just as important is his/her immersion in the quality of the experience. What do the buttons of her blouse feel like against the skin of his belly? Does his hair smell of smoke, or wet grass, or pomade? What does she taste when she kisses him on the mouth, and does it remind her of something/someone else? Writing with sensual detail is critical to creating the mood or tone of a sex scene – and rendering it as something consistent with the characters you’ve created. A sexual act is not passionate just because a writer asserts it is so; it’s in the specific sensual qualities of the details that a scene will really come alive.

Not all sex scenes have to be erotic…or even pleasant. For my money, there’s nothing better than a disappointing or disturbing sex scene to reveal something important about your characters. We all know that sex can be a crucible – a barometer of what’s going on globally in a relationship. When things are tense or downright hostile in a marriage, they’re bound to show up in bed. The value of focusing on what these individuals are thinking, or saying, or not saying, and of qualifying their actions with language that feeds into the tone of the scene, cannot be overstated. There’s no end to what a reader can learn about what’s going on in a relationship in one brief, conflicted sex scene. Maybe it’s just me, but some of the best sex scenes I have read have been anything but passionate: they’ve been downright devastating.

Know when to pull out. Obviously, sex acts have a beginning, middle, and end. But that doesn’t mean you have to report them in soup-to-nuts detail. Leaving some things to the imagination will encourage greater reader engagement, building anticipation by offering up partial, fleeting, titillating glimpses. It’s like hearing only half a song: for the rest of the day you can’t stop humming it to yourself, as though the lack of closure keeps it on permanent re-set. How many movies have been built on the premise of the almost-romance? Interrupting an unfolding sex scene can create a kind of frisson that adds urgency to both the relationship and the plot line. Like a striptease act, sometimes a little at a time is more than enough.

So go ahead. Write that scene. Pull out all the stops. Just remember: those are real people between the crisp white sheets of your manuscript – not inflatable sex toys. Treat them with all due respect.

Kim Triedman is both an award-winning poet and a novelist. Her debut novel, The Other Room, and two full-length poetry collections, Plum(b)and Hadestown, release in 2013. The Other Room was one of four finalists for the 2008 James Jones First Novel Fellowship, and Kim’s poetry has garnered many awards, including the 2008 Main Street Rag Chapbook Award and the 2010 Ibbetson Street Poetry Award. Her poems have been published in numerous anthologies and literary journals including Prairie Schooner, Salamander, and Poetry International. Following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, Kim co-organized and co-chaired a collaborative poetry reading at Harvard University to benefit Partners in Health and the people of Haiti. The reading was featured on NPR’s Here and Now with Robin Young and led to the publication of a Poets for Haiti anthology, which Kim developed and edited. A graduate of Brown University, Kim lives in the Boston area.

Kim Triedman is both an award-winning poet and a novelist. Her debut novel, The Other Room, and two full-length poetry collections, Plum(b)and Hadestown, release in 2013. The Other Room was one of four finalists for the 2008 James Jones First Novel Fellowship, and Kim’s poetry has garnered many awards, including the 2008 Main Street Rag Chapbook Award and the 2010 Ibbetson Street Poetry Award. Her poems have been published in numerous anthologies and literary journals including Prairie Schooner, Salamander, and Poetry International. Following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, Kim co-organized and co-chaired a collaborative poetry reading at Harvard University to benefit Partners in Health and the people of Haiti. The reading was featured on NPR’s Here and Now with Robin Young and led to the publication of a Poets for Haiti anthology, which Kim developed and edited. A graduate of Brown University, Kim lives in the Boston area.

Chris Abouzeid's Blog

- Chris Abouzeid's profile

- 21 followers