Chris Abouzeid's Blog, page 33

September 18, 2013

My Homemade MFA

By Randy Susan Meyers

“How did you get published? Do you have an MFA?” a reader asked last week. I struggled for the right answer—how to tell her that, no, I don’t have an MFA, but still, I credit being published on other people’s teaching.

A number of years ago (about ten to be inexact) I faced reality. If I were to be taken seriously by publishers and agents, I had to work with more intent. For a number of reasons (money, reluctance, working 50+ hours a week, and hyper-impatience with lectures) I didn’t return to school. Instead, I dove into self-study and set myself up as a virtual Miss Grundy.

On my bookshelves are over 90 books on writing (not counting those borrowed or given away.) Adding those would bring the number up by 35 or more. I read all, highlighted most, and drove the facts into my brain by writing papers (for myself) on them.

This week, as I began the process of outlining a new novel (having just given over number three to the temporary care and custody of my agent and new editor) I thumbed over a few of my favorites and realized, with gratitude, how much these authors gave me. A private MFA (minus the personal critique—for that I thank Grub Street’s Master Novel Workshop, led by the incredible Jenna Blum.)

I cannot be more grateful. Thank you all, generous writers of craft and more.

On Revision: “Cut it by 10 percent. Cut everything by 10 percent . . . Cut phoniness. There are going to be certain passages that you put in simply in the hope of impressing people. It is true of me, and it almost surely true of you. I have maybe never known a writer of whom it is not true. But literary pretension is the curse of the postmodern age. We all have our favorite ways of showing off and they rarely serve us well. When you have identified your own grandiosity, do not be kind.” The Modern Library Writer’s Workshop: A Guide to the Craft of Fiction, by Stephen Koch

“The only way to improve our ability to see structure is to look harder at it, in our own work and in others’. When you read a book you love, force your mind to see its contours. Concentrate on structure without flinching until it reveals itself. Text is a plastic art, not just a verbal one: it has a shape. To train your mind to see shapes more easily, write them (and sketch them if you like) in a notebook. As with writing down dreams, the more you write, the more you will see.” The Artful Edit: On the practice of editing yourself, by Susan Bell

On Craft:

“Significant detail, the active voice, and prose rhythm are techniques for achieving the sensuous in fiction, means of helping the reader “sink into the dream” of the story, in John Gardner’s phrase. Yet no technique is of much use if the reader’s eye is wrenched back to the surface by misspellings or grammatical errors, for once the reader has been startled out of the story’s “vivid and continuous dream,” the reader may not return.” Writing Fiction, by Janet Burroway

“What is the throughline? Throughline is a term borrowed from films. It means the main plotline of your story, the one that answers the question, ‘what happened to the protagonist?’ Many, many things may happen to her—as well as to everybody else in the book—but the primary events of the most significant action is the thoroughline. It’s what keeps your reader reading.” Beginnings, Middles and Ends, by Nancy Kress

“Imagine you’re at a play. It’s the middle of the first act: you’re really getting involved in the drama they’re acting out. Suddenly the playwright runs out on the stage and yells, ‘Do you see what’s happening here? Do you see how her coldness is behind his infidelity? Have you noticed the way his womanizing has undermined her confidence? Do you get it?’ . . . This is exactly what happens when you explain your dialogue to your readers. Self –Editing for Fiction Writers, by Renni Browne & Dave King.

“ . . . the quickest and easiest way to reject a manuscript is to look for the overuse, or misuse, of adjectives and adverbs.” The First Five Pages: A Writer’s Guide to Staying Out of the Rejection Pile, by Noah Lukeman

“Because fiction requires a mighty engine to thrust it ahead—and take the reader along for the ride—backstory if used incorrectly, can stall a story. A novel with too little backstory can be thin and is likely to be confusing. By the same token, a novel with too much backstory can lack suspense . . .. Remember this: The fantasy world of your story will loom larger in your imagination than it will on the page . . ..

Balance is the notion that every element in the story exists in its proper proportion . . . When you lavish a person, place, or object with descriptive details, readers expect them to have a corresponding importance.” Between the Lines: master the subtle elements of fiction writing, by Jessica Page Morrell

On Sustaining: “ ‘You have to remind yourself that it’s very hard work. If you drift along thinking you’ve got some sort of gift, you get yourself into some real trouble.’ “Arthur Golden

“I try to remember that a review is one person’s opinion—and a cranky person’s at that.” Elinor Lipman

‘The only reason writers survive rejection is because they love writing so much that they can’t bear the idea of giving it up’ ” M.J. Rose. The Resilient Writer, edited by Catherine Wald

“Over the years, I have calculated that feedback on any given piece of writing always falls into one of three categories, and breaks down into the following percentages: 14 percent of feedback is dead-on; 18 percent is from another planet; and 68 percent falls somewhere in-between.” Toxic Feedback, by Joni B. Cole

On Tension: “Inner censors interfere with effective revision in a number of ways. For instance, most fiction writers act like protective parents towards their characters, especially the hero and his or her friends. Writers are too nice. You not only don’t have to treat your characters nicely, in revision you should look for ways to make the obstacles bigger, the complications seemingly endless, and their suffering worse. Avoid the temptation to rescue your characters.” Manuscript Makeover: Revision Techniques No Fiction Writer Can Afford to Ignore, by Elizabeth Lyon

On Sex: “Sex is not an ATM withdrawal. Narrate from inside your characters’ bodies and minds, not from a camera set up to record the transaction.” The Joy of Writing Sex, by Elizabeth Benedict.

On Public Reading: “Few writers are truly gifted at giving readings, and most have panic attacks before doing an interview, whether for radio, print, or television. And nowadays an author who isn’t deemed ‘promotable’ can be a liability . . . It’s important to plan your readings and selections before you speak in public. Long descriptive passage usually put people to sleep, as does staring down at your book for twenty minutes and reading either too fast or in a monotone . . . provide some meaningful stories. If an audience has come out to see you, give them something they won’t find in the book.” The Forest for the Trees, by Betsy Lerner

On Humiliation: “The lowest moment in my literary career was when I found myself bidding for a middle-aged oil magnate in a mock slave auction at a dinner in Dallas. I was bidding for the sake of Bloomsbury and for the honor of England, but I think the compounds the shame.” Margret Drabble, Mortification: Writer’s Stories of their Public Shame, edited by Robin Robertson

On Environment: “In truth, I’ve found that any day’s routine interruptions and distractions don’t much hurt a work in progress and may actually help it in some ways. It is, after all, the dab of grit that seeps into an oyster’s shell that makes the pearl, not pearl-making seminars with other oysters.” On Writing, by Stephen King

(originally published in August 2011)

September 16, 2013

We Like To Watch

A comment in one of my new Amazon reviews got me thinking. I know, I know, look away from the sun. But, well.

The gist of the reader’s gripe in an otherwise positive review was that the ending cut in sooner than she would have liked. “I wanted to be in on the conversation that was about to happen,” she wrote, “but was sadly cut off.”

It has always felt to me like the right place to step away from the characters, with a hint toward where they are headed. But taste in endings is as varied and personal as taste in books. For some people, an open-ended conclusion offers freedom to entertain their own theories. For others it’s a heaping plate of shortchanged. (Remember the hoo-ha over the blackout finale of The Sopranos? And where did the cast of LOST really go in the end? Where did they ever go?) Some folks simply want to see things come in for a neat landing. Wheels down, you’re exactly where you need to be, you may now move about the cabin and move on. I get that.

The Amazon comment about wanting in on the unseen scene raises an interesting question though, and not just about endings. How much, and when, does a reader have to experience a plot turn played out in front of the eyes to feel satisfied? An author can convey information and events easily enough in other ways. But knowing something happens isn’t quite the same thing as seeing it happen in scene.

Jargon alert: “In scene,” for those who aren’t familiar with the term, refers to action that unfolds in live time, as opposed to things that happen offstage and are gleaned later or can be otherwise assumed to have happened. For example, a character is getting dressed for work, then later appears at the office. We can safely assume she turned the knob, opened the door and walked out of her house without having to see every tedious step in scene. However, if there’s a statement to be made in way she triple locks the door behind her and makes sign of the cross as she walks away, then by all means show it.

How does the writer decide what the reader needs to see? Generally speaking, readers feel more engaged witnessing a big event in its tense unfolding than having the action paraphrased after the fact, glossed over as a fait accomplit. Sure, sometimes expository writing has to happen to move chunks of storyline down the playing field. But when it comes to the big things, I wonder if a reader needs to see it in 3D detail to feel it in the gut, like seeing the body to believe the death. Say, the escape from a treacherous situation. The romantic connection of two people, finally, who’ve been prancing around one another for awhile. The murder of a principal character. Not very satisfying have these sorts of things tied up with a few descriptive sentences after the fact.

The exception is when the details of the scene are held out like a tantalizing carrot: it is hinted that this pivotal thing has happened, and you trust the author will show it to you down the road. Say you know from the beginning of the book that one character has lost a child under grueling circumstances. But it’s mentioned in a way so mysterious and unsatisfyingly brief that you just know the author’s going to come back and make good on it. An effective technique for building suspense, no? Of course there’s a fine line between vivid and gratuitous, and that line is as subjective as it gets. Love it or hate it, Sophie’s Choice wouldn’t be so unforgettable without the you-know-what.

The exception is when the details of the scene are held out like a tantalizing carrot: it is hinted that this pivotal thing has happened, and you trust the author will show it to you down the road. Say you know from the beginning of the book that one character has lost a child under grueling circumstances. But it’s mentioned in a way so mysterious and unsatisfyingly brief that you just know the author’s going to come back and make good on it. An effective technique for building suspense, no? Of course there’s a fine line between vivid and gratuitous, and that line is as subjective as it gets. Love it or hate it, Sophie’s Choice wouldn’t be so unforgettable without the you-know-what.

Sex might be another exception; in many books, the camera turns away from the characters in the heat of the moment and checks in with them again in the afterglow. Most readers accept that blush of modesty. Even if they secretly wish the bedroom door had been left open a crack.

And then theres’s this: Sometimes it isn’t possible to tell the story in scene, because you’re limited by the narrative point of view. There simply isn’t always someone privy to the event. How can one character, who wears the narrative camera on his shoulder in close third person point of view, show the love scene between his two friends if he wasn’t there?

There are ways to get around it, particularly if you can get creative with the narrator’s voice and imagination. One of the best I ever read had the narrator, a wry but modest man who came of age during the Depression, recounting the way he thinks it might have gone in the courtship of friends, married for decades. He describes the Vermont family compound they would have visited, and which he himself knows well.

“The love scenes of my friends have never been my long suit or my particular interest, and anyway, I don’t know that at that point she was sure she wanted him, though I am pretty sure she did…. So I will simply take them on the walk they would probably have taken. They go back through the wet woods to the main road…” — Crossing to Safety, Wallace Stegner

The walk they probably would have taken. And then a highly detailed imagined scene of budding romance that we accept as fact. Brilliant.

A last thought on deciding what to show in scene: There are some moments in your storyline that beg to be shown in narrative detail because they pack an emotional punch, or carry the promise of it. These can be plot points that contain pain, euphoria, the promise of vivid action, or simply the potential to deepen the reader’s connection to the characters and their fate. The trick is figuring out which scenes they are.

Sometimes there’s a sticky bit of plot you keep shying away from writing — it seems too hard, or gives you the heebie jeebies — and you manage to convince yourself, almost, that it doesn’t have to be experienced in real time by the reader.

I’m sorry to say, but chances are, that’s the piece that needs to be written. The omission most likely to make reader say, That bothered me, I wanted to see that.

September 15, 2013

The 6 Habits of Highly Tormented Writers

Healthy living has ruined literature. I’ll say it again: Healthy living has ruined literature. Why? Because with every new health trend—paleo-diets, pilates and yoga classes, vitamin injections, meditation—another writer gets healthy, and with every healthy writer literature plunges deeper into the abyss of mediocrity. Did we learn nothing in those college literature courses? Is our collective memory so short that we can’t remember what made the great writers great? Misery. Torment. Despair. Not endorphins.

Think about it. Could Kafka have written “The Metamorphosis” if he had been eating live food and training for tri-athlons every day? Would Virginia Woolf have written To the Lighthouse if she was going to zumba classes and downing super-fruit smoothies every morning? No. The fact is, great literature needs great misery.

Now, some of you out there are thinking you might write the next great novel. But I can tell you right now, you’re not going to make it—not if you continue to pursue the American ideal of health and happiness. What you need is to do is drop your inner child like a boiled, bland potato and get in touch with your inner tormented soul instead. Get back to the roots of great literature—pain. To help you in this journey, I’ve prepared this handy guide.

The 6 Habits of Highly Tormented Writers

Childhood Trauma

Every career as a tormented soul begins with a tale of childhood trauma. Maybe your father was killed by serfs. Maybe your mother embarrassed you by wearing that scarlet A wherever she went. Or maybe you just saw something nasty in the woodshed. Whatever your particular trauma, make sure you document it fully and weave it into your personal narrative at every opportunity. If you’re one of those unlucky souls without an unhappy childhood, if you grew up in a loving family with no abusive teachers or schoolyard bullies to obsess about, don’t despair. You’re a writer. Make something up.

Unhappy Marriage/Relationship

If you’re already in an unhappy marriage/relationship, good for you. You’re ahead of the game. If you haven’t had this experience yet, we recommend BadMatch.com. Based on your personal profile, they will find the exact dysfunctional relationship you are looking for: Nagging Whore of Babylon; Wicked Witch of the West’s Bitchier Sister; Handsome Domineering Bastard Who is Secretly Gay; Passive-Aggressive Lost Boy Who Wants to Be Mommied Day and Night; or the worst one—Writer With Much More Successful Career Than Yours. But pick your poison carefully. The wrong relationship may turn you into the crazed co-dependent, and your partner into the writer.

Substance Abuse

Don’t even think about trying to be a true tormented writer without indulging in substance abuse. And don’t think you can just pick any substance. It has to be the right drug for the right torment. Choose alcohol if you want to be a dark, angry bully prone to literary feuds, overwriting and impotence. Choose cocaine if you want to be a fast-moving, superficial socialite who writes exclusively about other cocaine snorters. Choose pot if your greatest dream is to write the next Jonathan Livingston Seagull. Choose crystal meth if you already have bad teeth. Remember: Recovery makes a nice human interest story, but “downward spiral into drug-fueled madness” makes better jacket copy.

Crushing Debt

In these days of credit cards and on-line ordering, it’s easier than ever to go into debt. Many writers will start small, buying things they don’t need or going on trips they can’t afford. This is a very misguided approach. Debt is debt. It doesn’t matter whether you accumulate it slowly or quickly. The important thing is to go as deep as you possibly can. So drop your health insurance and cavort with contagious people. Take out loans to go to medical school. (You don’t have to actually attend.) Buy everything advertised during one entire NFL season. Then sit back and let the debt crush you. Doesn’t it feel tormentingly good?

Rejection

Nothing torments the soul better than rejection. And no one attracts rejection better than a writer. Vast numbers of journals, editors, agents and friends stand ready to dish it out to you at any moment. But the best form of rejection is the kind that comes on a little slip of paper or in an email, preferably from a magazine or literary journal that has taken eight months to let you know they don’t want your work. Why? Because you can print them out. Collect them all, like baseball cards. Wallpaper your bathroom with them. Make drink coasters. Or bind them together to make a Rejection-A-Day calendar—the perfect gift for the writer who feels worthless.

Disease

No one wants a disease. And yet we all admire the passion of those artists tormented by disease. What would Wordsworth and the Brontës have been without consumption? What kind of paradise would John Milton have envisioned if he hadn’t been blind? We can’t recommend that you go out and contract a debilitating disease. But if you can manage to get a bad case of foot fungus or a nasty persistent sinus infection, it would go a long way towards perfecting your tormented state.

That’s it. Now go out there and make misery your muse.

September 12, 2013

Behavioral Management for World Peace

As I zoom up I-95 to take my son to school, we listen to NPR. He’s in fifth grade, learning about World War II, so I figure he’s old enough to hear about Syria.

He has a lot of questions about Syria and I answer as best I can, but I have always taught him that violence is bad. I have praised him yesterday for walking away from a blatant insult, for staying calm instead of hitting his five-year-old sister back. And here is Obama talking about bombing Syria.

Somewhere along the way, Obama got instructions from his own parents and teachers on how to be a good guy. No hitting, Barack. No vindictiveness. Be nice. And he listened. This is how he advanced, how he got into Harvard Law, how he got elected to the most powerful position and is the most powerful man in the Western world.

Someone in the White House had to teach this genteel man. Someone pulled him aside and said, with all due respect, Mr. Obama, it’s the real world here. In school, in Congress, you get ahead by being smart and well-mannered. In the international arena, you use guns, bombs, drones. It’s about power. You see someone you don’t like, you eliminate him. It’s not murder. It’s maintaining the upper hand. It’s sending a message.

Here’s my personal opinion of that world view: it’s archaic. A head of state is a person. His subjects are people. And people, as psychologists have learned, and I have seen in my roles as physician, mother, and researcher of political oppression, respond much more powerfully and deeply to positive reinforcement than to punishment. Rule with the well-being of the people in mind, and you have a loyal, if noisy following. Rule with violence and intimidation and you will have quick but superficial and short term obedience that hides resentment and the desire for retaliation. Force breeds more violence. It’s a simple, reliable formula.

So a head of state slaughters his people. It’s unconsionable, it’s sickening. He’s controlling with violence. He’s a bully. International experts hover around the president, saying, the only thing he understands is violence. The message must be sent. Bomb him.

Call me naïve– I’m no politician or international relations expert. But this is like going up to the school bully, punching him in the face, and telling him he ought to stop bullying people, or else. Of course he’ll stop, because he’s afraid of you. But now he’s mad at you, knows that you’re a hypocrite, and is even madder at the kid he was bullying. He’s plotting retaliation, big time, and this time he’s bringing friends.

In the old days, people would approach a school bully just that way, just as we would have disciplined our children by spanking and whipping. But these days we are enlightened. We know it will be more effective to talk to the bully. We find out what his circumstances are. We talk with his parents. We devise, in the best of cases, an incentive system. We find out what he really, really wants, and use that as a reward. No bullying for the rest of the year and you go to your favorite summer camp. The bully is invested. He is motivated. He’s doing what you want, and you give him what he wants. He appreciates, over the long run, how you have helped him. When he’s older he may even emulate you.

In the international arena we are still in the old days. We are stuck in punitive mode, bullying with whips and belts, exchanging eyes for eyes and teeth for teeth, anti-tank missiles for aircraft carriers. We are out of touch with human nature.

I drop off my son at his new school–one that, by making him feel accepted and valued, has transformed his classroom behavior from that of a caged animal to that of an enthusiastic little scholar. As he walks happily toward his class, I fantasize about an enlightened way of approaching international conflict. I dream of a world in which states are rewarded for abiding by international laws of non-violence and human rights. The state with the most improved human rights conditions gets funds to host the next Olympics. The state that resolves its rebellion nonviolently gets the most favorable trade agreements across the board. The state that gives up its nuclear weapons gets a huge deal on oil or a seat in the United Nations. Whatever it is that different states want and need, we could conspire together, globally, to give it to them, if they behave nicely. So that a man who would be president doesn’t grow up to unlearn everything his mother ever taught him about life. And so that international news stories make perfect sense. Even to a ten year old child.

Summer Lessons from an Unpublished Essay

For the better part of the last decade, I’ve been reading other people’s essays for a living–as a writing teacher.

By the time summer comes, I’m eager to trade teaching for my own work. And this one wasn’t any different—I had three glorious months of writing time.

But there was one thing I didn’t do.

Every summer for the last seven years I’ve returned to an essay that is, so far, unpublished. But now it’s September, and time to admit that another summer has come and gone without me returning to that essay. And maybe I never will.

I thought about it all summer. I found an old printed copy when I straightened my study for the summer. I read it over. I liked it. I even liked the writer’s voice I found on those pages. I could try again, I told myself. But since I wrote it, digital has changed how we read. At 10,000 words, the essay is so long it would get rejected for length alone.

There’s an old writing teacher’s cliché I’m sure I’ve rehearsed in every class I’ve ever taught: “No one writes for the desk drawer.” Stephen King says to put your draft in the desk for six weeks before revising. Annie Dillard, in The Writing Life, likens revision to carpentry. A “line of word is like a hammer,” she writes. Be on the lookout for the “bearing wall that has to go.”

But does it have to be in print to matter? Sometimes, are we writing for ourselves?

The idea was I’d write an essay in reply to Camera Lucida, French critic Roland Barthes’s little book on two subjects close to me–grief and photography. I took on writing it at a time when I wasn’t sure I could read or write with any discipline. Yes, I was a photographic historian, but I was also a widow with a four-year-old. I knew my abilities as a critic weren’t entirely gone—I could teach literature and history and convey my passion for images and ideas to my students. But grief had left me foggy, unsure about what I wanted to put on the page.

Writing in response to someone else gave me a structure. It was a way to brace myself, as if I were wearing casts to regain my strength.

It took a year. I struggled with reading and sitting at my desk without bolting. I worked in small increments until I built up stamina. I devised a way to write that was both emotional and analytical. The work of reading, thinking, and writing helped me reclaim part of myself I thought grief had destroyed.

I sent the finished essay out a few times, but it never found a home. Scholarly journals said it was too intimate, literary journals said it was too intellectual. Their comments exposed my own ambivalence. Was I an academic, a critic, or simply a prose writer? Unsure, I set it aside.

Friends who’ve read it long ago still ask what happened to it. Just last spring, a friend took the time to re-read it. “It needs more Volpe, less Barthes,” he told me. Something sank in that hadn’t before: I needed to claim my voice.

When I started writing the essay I wasn’t sure that, even if I could write, I had anything worth saying. I pegged my thoughts against the author to whose book I was responding—I wasn’t reaching far out enough on my own. Now I see I wasn’t strong enough in claiming my own experience. I borrowed Barthes’ until I could hold my own with the essay form and discover what I needed to say. In other words, I was acting like a student—in the best sense of the word.

It’s easy for me to tell my students that books teach us, that writing in response to ideas brings us someplace new. But the teacher hadn’t acknowledged this for herself: if you let it, writing can change you.

If I wanted to, I could still reclaim the essay and push myself to get back to it. Should I? I’m not the same person who wrote that essay so long ago. Reading it now, I see and hear a previous version of myself. Would revision give the essay more of me or a different me? Maybe this essay isn’t meant to be published, maybe it’s meant to be evidence of who I’ve become—an essayist. Maybe what mattered is that I wrote it at all.

Andrea L. Volpe has taught at Harvard, Colby, and Boston University. Her work has been published in

The New York Times

,

The Christian Science Monitor

,

Cognoscenti

,

Barnstorm

, and The Calla Lily Review, among others. Follow her on twitter at @andrealvolpe and find her at www.andrealvolpe.com.

Andrea L. Volpe has taught at Harvard, Colby, and Boston University. Her work has been published in

The New York Times

,

The Christian Science Monitor

,

Cognoscenti

,

Barnstorm

, and The Calla Lily Review, among others. Follow her on twitter at @andrealvolpe and find her at www.andrealvolpe.com.

September 11, 2013

Fall Book Buying Guide

It’s still summer, but it won’t be for long. And that means fall’s a coming. It’s one of the biggest times of the year for publishers and booksellers, leading into the end-of-year gift buying season when many of the big, important books get published. It’s like Oscar season except for books.

So here’s my (woefully incomplete, entirely subjective) list of interesting novels (mostly) on the near horizon.

Doctor Sleep, by Stephen King. A sequel to The Shining. Come on, who hasn’t read The Shining? What fan wouldn’t be interested in finding out what happens to an adult Danny Torrance. For his first sequel, King picked well. In typical fashion, this one’s a real horror: “Dan, now using his “shining” to help others, encounters another magical being in the form of 12-year-old Abra Stone, who he must save from the True Knot, a clan of malicious paranormals who live off the steam that children with the “shining” produce when they die.” Ew, gross! Count me in!

The Goldfinch, by Donna Tartt. I still remember the fun of The Secret History from the early 90s, and Tartt’s new novel sounds like a worthy companion. It starts “an explosion at the Metropolitan Museum that kills narrator Theo Decker’s beloved mother and results in his unlikely possession of a Dutch masterwork called The Goldfinch. Shootouts, gangsters, pillowcases, storage lockers, and the black market for art all play parts in the ensuing life of the painting in Theo’s care.”

The Circle, by Dave Eggers. On a roll after his last book, A Hologram for the King, became a A National Book Award Finalist, Eggers is back with a Douglas Coupland/Max Barry-esqe tale of a young woman who lands a job at a hip Internet company, only to find things are not all what they seem. “What begins as the captivating story of one woman’s ambition and idealism soon becomes a heart-racing novel of suspense, raising questions about memory, history, privacy, democracy, and the limits of human knowledge.” So much for idealism.

Half the Kingdom, by Lore Segal. Author of the acclaimed novella, Lucinella, Segal returns with a dark comedy about aging in a post 9/11 world.

At Night We Walk in Circles, by Daniel Alarcon. The second novel by the author of the wonderful, riveting, and heartrending Lost Radio City, “draws inspiration from stories told to him by prisoners jailed in Lima’s largest prison. Alarcón again situates his novel in a South American state, where the protagonist flounders until he’s cast in a revival of a touring play penned by the leader of a guerilla theatre troupe.”

The Lowland, by Jhumpa Lahiri. More Pulitzer Prizewinning storytelling with the story of two brothers. “Udayan, the younger by 15 months, is passionate, idealistic and ripe for involvement in the political rebellion in 1960s India. Subhash is the ‘good brother,’ the parent-pleaser, who goes off to study and teach in America. But when Udayan, inevitably, ends up a victim of his self-made political violence, Subhash steps in and marries his dead brother’s pregnant wife.” Excerpted earlier this summer in the New Yorker fiction issue.

His Wife Leaves Him, by Stephen Dixon. The latest from this iconoclast concerns the interior life of a man whose wife has just left him. No doubt this will be an exhaustive survey of one man’s psychological landscape. If I know my Dixon. And I think I do.

The Thicket, by Joe R. Lansdale. The author of Bad Chili and Bubba Ho-tep returns with a western full of “love and vengeance at the dark dawn of the East Texas oil boom.”

The Daylight Gate, by Jeanette Winterson. A novella about a group of mostly poor women in the north of England, labeled the Lancashire Witches, who are on trial for witchcraft in 1612.

Enon, by Paul Harding. Harding’s second novel is a sequel to his Pulitzer Prize winning Tinkers. In Enon, “the grieving Charlie Crosby, grandson of the “Tinkers” protagonist, tries to come to terms with the death of his daughter and the breakup of his marriage.”

My Notorious Life, by Kate Manning. The fictional account of Axie Muldoon, “a fiery heroine for the ages.” Sara Nelson says “A historical novel of Dickensian sprawl, My Notorious Life is loosely based on the experiences of an infamous midwife in late 19th century New York. While she’s eventually dubbed Madame X by a rabid press. our heroine’s strength is that for all her success at self transformation, she remains forever the orphaned guttersnipe Axie Muldoon–a pioneer for women’s rights before anyone much knew that such rights could exist.”

Dream of the Antique Dealer’s Daughter, by Robin Smith-Johnson. Not a novel, but a debut collection of poems by this wonderful Cape Cod poet. Her work has been described as luminous and ethereal. I should know: I’m her brother (go sis!). Her collection is coming out this December from Word Poetry Books.

And one more for you. It’s not new, but will be newly out in paperback this month:

May We Be Forgiven, A.M. Homes – I didn’t cotton to Music for Torching, so when I read her 2007 This Book Will Save Your Life, a sprawling L.A.-set novel , I fell quickly and happily for the book’s humor and humanity. May We Be Forgiven promises more of the same with “a darkly comic look at twenty-first-century domestic life and the possibility of personal transformation.”

How about you? What upcoming release are you making room for on your bookshelves?

September 9, 2013

A Literary Experiment: Crowdsourcing the Fate of a Girl

I have not been a published author very long. I’m still learning about the sacred relationship between writer and reader. What is given; what is received? For one, I’m of the belief that readers owe authors very little. If I’m not doing my job on the page, you won’t stay. End of story.

When I first started writing, I thought of myself as very avant garde, a sentence-cultist. I was too cool for plot and quotation marks. Then, during one particularly sharp workshop, my professor simply said: You write beautiful sentences, but I’m not the reader for you. You’re still writing for yourself.

This is what we southerners call a Come to Jesus Moment. This is when you have to assume No Cry Face in public. You are the Terminator; what are feelings?

Ever since that workshop, I’ve been asking myself: what do I owe my readers? What information do they need? What would be satisfying?

That said, artistic merit and technique matter to me. I still like sentences that punch you in the stomach. I can’t promise to give readers exactly what they want; I just have to convince them to trust me and come along for the ride.

Sometimes what the reader wants for a character is not possible. Often a protagonist’s happiness, or freedom, is hard-earned, maybe even impossible. How many books with happy endings do you know? Or how many happy people, for that matter? Authors have to honor the struggle of being human.

*

When Medium and Ploughshares asked me to write an experimental story, one where I let readers weigh in on the ending to a narrative, I knew I’d have to construct a narrative that ended with a significant choice. Here’s why: 1) a big decision has powerful narrative energy – readers typically feel it coming and want to read on 2) it was the best way I could imagine inviting others into my work, letting them tell me what they want.

So why the hell was I so surprised when readers responded to me not with what they wanted next for the story, but for the character?

I wrote about a young girl, Emery Dixon, who was struggling to create her identity after a stint in boarding school. I’d been reading Rachel Simmons’ book The Curse of the Good Girl and thinking about that nasty phase of post-adolescence where so many young women lose their confidence and fall into pleasing behaviors, Mean Girl antics, and ritual apologizing. I thought of the book as a parenting guide—I have two young daughters—but reading it made that miserable period of my life very fresh. I poured those feelings into my story.

I don’t want to give the story away, but after a series of bad decisions, Emery has been brought home from college by her parents, and late one night she is staring at her open bedroom window. I asked readers: does she stay or does she go?

I wasn’t prepared for the answers. I was interested in the technical response to my story: what happens next? What I received—in other words, my gift from readers—were heartfelt emails, phone calls, margin notes, Facebook and Twitter responses that expressed concern for my character. In many cases, the reader participation in the narrative was not based on what they thought happened next, but what was best for Emery.

When I posted the endings, I felt dishonest. I realized that I had not let the readers choose my character’s fate; I had already decided that long before. I let them choose one of many paths toward Emery’s further self-discovery. I could not give them the happy endings they wanted. After reading the endings, some readers responded that they felt guilty for choosing a particular path for Emery.

I received more than a few moving emails from other women about what this story reminded them of, how uncomfortable Emery’s experience made them feel. How it made them afraid as parents of young girls.

We read, I think, with an eye for beauty on the page, but also a resolution mindset. We read with our desperately empathetic brains, all our humanity intact. What a beautiful lesson for a writer, a reminder of where we take the readers when we go somewhere undesirable, or maybe even somewhere true.

Megan Mayhew Bergman lives on a small farm in Shaftsbury Vermont with her veterinarian husband and two daughters. She is the author of Birds of a Lesser Paradise and a forthcoming novel, both from Scribner.

Megan Mayhew Bergman lives on a small farm in Shaftsbury Vermont with her veterinarian husband and two daughters. She is the author of Birds of a Lesser Paradise and a forthcoming novel, both from Scribner.

She can be found at www.mayhewbergman.com and sharing chicken photos and deep thoughts on 80s music videos on Twitter @mayhewbergman.

September 8, 2013

After You Sign The Publishing Contract: What Comes Next?

Imagine this: Someone asks you to marry them, and because you are so eager (desperate?) to wed, you say yes—even though you don’t know them, don’t know what they expect, and don’t know what they’ll bring to the table besides the (gender-free) shiny ring they push up on your finger.

That’s kind of what it’s like the first time you enter a contract with a publisher. Perhaps some of you were a whole lot smarter and you knew what was coming, but more likely you resembled me: naïve, starry-eyed, gasping with disbelief and playing the Sally Field card: You like me, you really like me, twirling in a circle of happiness, kissing your agent through the phone, and having no idea what came next.

So what should you expect? What’s going to happen first, second, and third? It drove me crazy not to know (when I published my first novel.) I’m an excessively need-to-know-everything person, which led to me driving my editor and agent crazy, which led to co-authoring a guidebook What To Do Before Your Book Launch with M.J. Rose. Because along with our mutual need-to-know, is a need-to-share. This overview of the basic steps your publisher will likely take after your contract is signed comes from that guide.

Every publisher’s timeline is different; within your publishing house, every editor is different, and every client at that house will get different treatment. With that as given, here’s what you can expect from your publisher after you get that first check:

1. A launch date will be set. It can be a year to eighteen months (or a little more or a little less) ahead depending on the book and the house.

2. Your editor will provide editorial comments to guide you in your first revision. This process could take anywhere from one step to many iterations, as you and your editor go back and forth.

3. Your editor will accept the final manuscript and send it to a copy editor.

4. You’ll get your second check.

5. About 6–7 months pre-launch your editor will be presenting the book internally at a launch meeting to various departments, such as: Sales, Special Sales, Design, Marketing, Publicity, Audio and Subrights.)

6. Cover design will begin. (And later you’ll get to approve a final.) This will also happen 6–7 months before publication—usually after that internal launch meeting.

7. You’ll receive a copy-edited manuscript—with a deadline. In time you’ll get second pass pages and sometimes third. With each subsequent set of pages, you will be ‘allowed’ to make less changes, so be thorough.

8. About 5–6 months pre-publication you will be assigned a publicist and a marketing person. This is usually 6–7 months pre-launch.

9. Discussions between you and your editor about who to get blurbs from will be initiated. Never be afraid to ask your editor and agent to help here if you don’t feel comfortable asking other authors yourself.

10. Galleys (advance reader copies aka ARCs) will be sent out for reviews and blurbs. This is usually 4–6 months prepublication. (You will get you own ARCs—best used for those who will help spread word of the book.)

11. At the 4–5 month pre-publication point your editor will present your book at a sales conference to all the sales reps. You should get a copy of the sales catalog including your book.

12. Once sales conference is over, marketing and PR plans will be finalized and your editor will be keeping you up to date about what the house is going to do for your book.

13. About 3–5 months pre-publication, early reviews from the trade will start to come in.

14. About 2–3 months pre–publication, you should be working with marketing and publicity to set up plans.

15. About 6–8 weeks pre-publication your editor will send you the first finished book.

(The above information was taken from WHAT TO DO BEFORE YOUR BOOK LAUNCH, which also contains a timeline author tasks in the year before a book comes out, along with all other aspects of launching a book.)

September 5, 2013

You Don’t Say

Robin Black

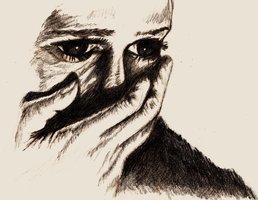

So, here is a writing exercise it might be fun to try. (And arguably the best part is that there’s no actual writing involved.)

For one hour, during a time when you are with at least one other person, keep track of everything you think, but do not say. Better yet, since thinking about what you’re thinking about requires the kind of mental contortion that may result in a brain sprain, at some point,after you have been around other people, try to remember a few of the things you were thinking but did not say.

That’s step one. Step two is to make an honest appraisal of which was more interesting, what you did say or what you didn’t say? Which revealed more about your true character? Which carried in it more potential for drama? Which exposed more about what was actually going on between you and the other people?

Yeah. I thought so.

Step three? Go reread your own fiction and ask yourself whether what goes unspoken is playing a large enough role in your work.

One of the joys of fiction that’s obvious but maybe not marveled at enough is the magical access a reader is given to the inner lives of other people – albeit make-believe ones. Among fiction writers the subject of this access most often arises in the context of (endless) conversations about and treatises on the subject of point of view. Which point of view allows an author to share the thoughts of how many characters? How does all of that work? How do you change points of view within a single scene? What the heck is narrative distance? And so on. (And on and on. . .) And I for one am a bit of a point of view junkie, or maybe I mean a point of view nerd. I love those discussion, love the strategizing and love exploring the implications of all those choices.

But what at times gets lost in the conversation, the forest obscured by all those many, many trees, is this simple fact: fiction allows us to have unlimited access to the thoughts of other people. There are limitless possibilities! Yet the thoughts that appear in fiction are often quite limited. And in some sense they are too tied to the dialogue in a scene. All too often once we set one character in conversation with another, we forget about the conversation that character is having with herself. And the fact is, it’s very often that conversation that contains all the really juicy stuff. And it’s the juicy stuff that reveals character. And revealing character is something that we all want to do.

There’s another benefit too to a fictional wandering mind. Including a character’s thoughts can render dialogue looser by introducing other strands, taking away that artificial call-and-response quality that fictional dialogue too often has.

The very best critique I ever received of my dialogue was: These people say exactly what they mean too much. I didn’t take that to mean that people are all duplicitous most of the time, but that there is a wealth of tension to be found in the discrepancy between what a character says and what’s really on her mind. And tension, in fiction, is wealth indeed.

So here are three exercises to try the next time you want to add some layers of complexity to a scene and a character both. Oh and the examples here are not offered as great literature, but just to give some sense about how much more layered a scene can be when there are thoughts that go unspoken on the page.

1. Have your point of view character explicitly think of saying something but decide against it:

“For a moment, Eleanor imagined herself telling him about having burned the stew, but he seemed so happy sitting there with his drink and his anticipatory smile. ”Do you think we should dress for dinner?” she asked instead. “We never do anymore.”

2. Have a character’s mind wander so she loses track of the conversation at hand:

While Cynthia continued to talk on and on about the argument she’d had with the roofer, Estelle tried to remember the name of the little shop where she had bought her boots the year before. It had sounded like a nursery rhyme. Mother Goose Shoes. Or Little Lamb Shoes. Something like that, but not either of those.

“I have no idea if I was even right,” Cynthia said. “But I gave up trying to be reasonable about ten minutes in.”

“I’m sure you were right,” Estelle answered, though of course she had stopped paying attention long ago. “You’re usually right.”

3. Have a character keep up a running internal critique of the conversation without missing a beat in the actual dialogue.

“Friends don’t let friends buy skunks,” George said, and Maria cringed inside at the pun.

“Not around here they don’t,” she said.

“Buy skunks,” he repeated, grinning from ear to ear.

What a moron. Did he think she hadn’t heard it or hadn’t gotten his joke?

“Nope,” she said. “Friends do not let friends buy skunks. That’s a good one, George.”

With each exercise, ask yourself whether more was revealed about the character (and also about the relationship between the two characters) by what was said or by what wasn’t said. And remember, a character’s thoughts don’t have to be 100% engaged in the conversation at hand. In fact, it’s very often better if they’re allowed to wander a bit – as our thoughts so often do. One of the great strengths of fiction is its associative quality, precisely because so much of our thinking is itself associative. We make connections that aren’t always logical or obvious. And there’s no reason that our characters can’t have minds that jump around in that manner too.

There are a million – or more – other ways to play with trying to capture the unspoken on the page. Write a scene in which one character has a secret they are dying to divulge but can’t. Write another in which one character has OCD and is counting how many syllables the other character uses in every sentence. Write one in which a character is trying hard not to think about something – but can’t help herself.

Or, as I started by saying, start by keeping track of everything you don’t say the next time you find yourself in conversation. And go on from there. . .

Originally appeared on Beyond the Margins on August 15, 2011.

September 4, 2013

Remembering Tucker: Writing What You Don’t Know and Wish You Didn’t Have to Learn

There is a scene in my novel where a dog is put to sleep at a veterinarian’s office. It is a telling moment, because the dog’s owner slips away at the beginning of the procedure, leaving his girlfriend to comfort the dog at the end of his life.

The euthanasia of a dog is not something I had ever seen myself, and writing this scene was not something I enjoyed. At the time, our own dog was a healthy seven year old, and I resisted thoughts of the day we’d have to say goodbye to him, whenever that might be. It also brought to mind the Golden Retriever of my childhood, who’d lived to be 18. By the time she was eased out of this world, I’d already left home and hadn’t had the chance to say goodbye.

But years later, I was there for my own cat’s last moments. And as much as I didn’t want to dwell on that memory, when it came time to write, I did know what it was like to be in that exam room doing the hard thing.

The veterinarian had agreed to let her stay on my shoulder, which had always been her favorite place to be. Her front paws kneaded at my shoulderblades, small tapping movements that felt on that day like a pat on the back, You’re doing the right thing. I was five months pregnant with my third child, but that cat had been my first baby, adopted 12 years before from the ASCPA in New York. Its staffer had even questioned on my ability to be a working, single kitten-mother: “How late are you at the office?” she’d asked. “Do you travel?”

I was five months pregnant with my third child, but that cat had been my first baby, adopted 12 years before from the ASCPA in New York. Its staffer had even questioned on my ability to be a working, single kitten-mother: “How late are you at the office?” she’d asked. “Do you travel?”

As they gave my cat the sedative I stroked the soft lawn of her back, feeling the bump of each vertebrae. Soon, her weight settled in a way that conveyed her departure even more than the last injection would. As painful as it was, there was some relief in knowing I’d had the strength to be present: I had seen her out of this life with the same companionship she’d shown me through it.

As they gave my cat the sedative I stroked the soft lawn of her back, feeling the bump of each vertebrae. Soon, her weight settled in a way that conveyed her departure even more than the last injection would. As painful as it was, there was some relief in knowing I’d had the strength to be present: I had seen her out of this life with the same companionship she’d shown me through it.

Still, I knew my perspective was different than the one I was writing for my novel. I’d held my cat in my arms as she’d died, an intensely intimate act, but I had not had the experience of looking at her as it happened. I thought about asking a few friends what it was like to euthanize their dogs, but frankly, I didn’t want to put any of us through that. I assumed I could extrapolate well enough from my own event to create this new one. Writers must always be writing about things they have not themselves experienced.

But when it came time for me to experience it for myself, there were things I had not known. It had not occurred to me that a dog put on a metal examination table might work to stay up rather than lay down. That even wearied, he’d be reluctant to concede his ability to stand, to give up his view of the world upright for the last time.

I didn’t know that after the sedative the pupils would dilate, increasing and decreasing as we spoke to him. I thought it was in response to the familiarity of our fading voices, my husband’s and mine, but it could have been just a reaction to the chemical. Or maybe in his final moments, a dog sees bits of his life as people are said to do: Revisiting the first swim in the lake chasing a thrown stick, and the arrival of each noisy newborn who would grow to pull his tail. Recalling his first meeting with that cat, who had hissed until eventually becoming dear as a sibling. And finally settling back on the memory of those actual siblings, littermates of fox-colored pups photographed together in a large Christmas box for the owners who would claim them at eight weeks. Hopefully in his visions there were flashes of the kindness I’d shown him instead of the scoldings, which at that moment I was remembering all too well.

and the arrival of each noisy newborn who would grow to pull his tail. Recalling his first meeting with that cat, who had hissed until eventually becoming dear as a sibling. And finally settling back on the memory of those actual siblings, littermates of fox-colored pups photographed together in a large Christmas box for the owners who would claim them at eight weeks. Hopefully in his visions there were flashes of the kindness I’d shown him instead of the scoldings, which at that moment I was remembering all too well.

In the end I rubbed his never-groomed-enough ears, as my character had in the scene I’d written. But unlike my character I bent low and told him Good boy, over and over. Because unlike my character I was the dog’s owner, and an owner knows the final words her dog wants to hear. That in spite of the counter surfing and carpet soiling, he’d been a very good boy.

Those are the things I didn’t know when I wrote about the fictional dog five years ago. But I know them now.

Originally appeared on Beyond the Margins July 29, 2010.

Chris Abouzeid's Blog

- Chris Abouzeid's profile

- 21 followers