Randy Susan Meyers's Blog, page 32

November 6, 2013

The Joy of Jewish Book Festivals

“Don’t forget; Jewish people read an enormous amount,” my lovely (and Jewish) literary agent said before my book launch. “We really love books.”

I nodded. Yes, I knew that—at least I knew it inasmuch as I was Jewish and I read—as did my mother, my sister, and my daughters, but could I raise that sample to the status of landslide? Discerning what was true in my culture was fraught with difficulty. I grew up with a slight case of anomie, surrounded by a cultural belief that all-things-Jewish=equals families-pushing-one-towards-great-achievement, while, among other family oddities, my grandmother taught me to shoplift.

I was unclear what being Jewish meant or if I belonged.

Then, in November 2011, I had the great good fortune of being invited to participate in Jewish Book Festival and finally felt the full impact of being welcomed into the larger Jewish community.

Jewish Book Month, according to the overseeing Jewish Book Council is “an annual event on the American Jewish calendar dedicated to the celebration of Jewish books. It is observed during the month proceeding Hanukkah, thus the exact date changes from year to year.”

For writers, this translates to: if you’re a Jewish author, or wrote a Jewish-themed book, you can participate in a massive authorial version of American Idol. Call it Jewish Writer Idol, only rather than one winner, there are many, and the chosen ones speak at some number of the over 100 Jewish Book Festivals. If you scale the steps (applications, sending books, etc) you earn the right to sit in Hebrew Union College, crowded thigh-to-thigh in a roomful of other authors, seated before representatives of the various festivals. You’ll have 2 short (or, in some cases, seemingly endless) minutes to convince the audience to pick your book. The not-thanked-enough audience sits through endless afternoon and evening sessions, until the books must merge into one giant mybookillustrateswithdepthandcaring.

Afterward, the audience returns home to read boxes of books before the picks are chosen, traded, and who-knows-what. (I actually know almost nothing about what goes on behind the closed doors—but I imagine it as a giant book debate, perhaps like a continent-wide game of Monopoly.)

Meanwhile, I experienced the nerd equivalent of Rush Week, waiting to see if I got any invitations; then becoming totally Sally Field when they arrived: They liked me! They really liked me!

And then I flew around the country. How to describe the feeling of walking into these Jewish Community Centers filled with readers eager to hear from you? I felt as though I were finally meeting every aunt, uncle, and cousin I’d ever wished for.

Warmth and love was present everywhere: In Columbus, Ohio I had the pleasure of pairing up with local anti-domestic violence groups (based on themes in my novel) and within the event, moving from discussing my book to considering best practices for prevention. The JCC bookstore was heaped with books I wanted to read. Pure gold. (Plus I got to have dinner with my much-admired online author friend Carla Buckley.)

Unless I’m kidding myself, I made friends for life. Detroit knocked me over. I walked into their “Book Club Night” to be greeted by over 300 men and women. Somehow, in this large insightful crowd, we became an intimate group of friends discussing details of writing and life. (It’s also where I gushingly embarrassed myself by sharing with my 300 personal friends my admiration of the upcoming author Darin Strauss.

I’m still red-faced. Moral of story: 300 people do not hold secrets.

The world can be mighty small for a minority: I learned that playing Jewish geography in San Diego. Along with being spellbound by how enraptured they were with books, I discovered connections to high school, camp, college, and most important—to the Jewish Federation of Philanthropy, who saved my life as a child. I had the thrill of seeing that they nurtured authors from both large and small presses, such as my friend Ellen Meeropol, a Red Hen author. It was also here that I finally met Lois Alter Mark in person, who introduced me to Miriam Mendoza’s sad and yet emboldening story of her family’s encounter with domestic homicide.

Have I mentioned food? I flew at 6 AM from San Diego to St. Louis. There the joy of presentation and forming a mutual admiration society with co-panelist, author Alyson Richman (whose book gripped me the entire flight home) mingled with a hospitality that still warms me today. Local children’s author, Jody Feldman saved my life with coffee and caring when she greeted me (inside!) at the airport. The next morning, Alyson, the moderator, Ellen Futterman, editor of the St. Louis Jewish Light, and I, were treated to breakfast and an opportunity to meet each other before our event. After the incredibly well-attended and joyous morning (with Alyson and I now firmly in love) we were taken out to a magnificent multi-course lunch.

By now, I was considering moving to the Midwest.

The food theme continued in Virginia Beach. A tower of desserts gilded the Book Club Night. Seated in a stuffed armed chair, I spoke with a group of women and men who’d not only read my book, but came armed with deeply moving questions and consideration. Again paired with a local domestic violence group—and again I was struck by community connections, dedication to helping, and the commitment to books and life-long learning. I was picked up for the event by a woman filled with the spirit of generosity and family, and driven back to my hotel by her mother—a woman who dedicated part of her retirement to teaching children to read

Back home, I got a few snappish reactions from non-Jewish writer friends, usually along the lines of, “Why isn’t there a Wasp book festival?” (I bit my tongue against saying: There is. It’s called life,) put off by the exclusionary nature of the events. To me, it’s a way for a tiny percentage (.02 %) of the world, a percentage sharply cut by the Holocaust, to celebrate how despite a history of oppression and anti-semitism, we became strong at the broken places—and are diverse enough to include those as different as Dr. Izzeldin Abuelaish, an advocate for peace in the face of devastating personal tragedy, Susan Orlean, author of Rin Tin Tin: The Life and the Legend, and Rabbi Andrea Myers, once a Lutheran, now a member of the New York Board of Rabbis, as well as a lesbian who was active in New York’s fight to recognize gay marriage, in the celebration.

Every community I visited brought remembrance of the past and hopeful embrace of the future. On a personal level, they provided not only an opportunity to talk about my book, but my anomie is greatly ameliorated. Being Jewish means a host of things—including ensuring provision of a big tent. I was invited, I felt cherished, and I belonged.

And, as my agent wisely said: Jewish people really love books.

This is a re-run, originally published in 2011. Now that I am again participating in the Jewish Book Festivals (St. Louis, Cherry Hill, Boca Raton & West Hartford, it seemed the right time to once again say thanks.

October 16, 2013

Outlining A Story: When Advice Differs

Advice to writers is a funny thing (I’ve had my share of taking and giving) and when I have the opportunity (hubris?) to offer my opinions, I try to remember to preface my words with “this is what works for me.”

Oppositional advice can spin one’s head around. It often all sounds good, something that struck me as I caught up with recent (paper) issues of The Writer, reading first, in the November issue, the thoughts (on writing a novel) of Andre Dubus III, New York Times bestselling author:

“Dream, dream, dream it though. Write more with your body and less with your head. Don’t think a story through, don’t think it out. The danger of thinking it through is that most of us are not smart enough to do it that way. We have to go one moment at a time.”

Later in the article, he included in his ‘advice to new writers,’ “Do not outline stories and do not think about stories. Find one true sentence at a time, one detail at a time.”

Dubus teaches writing; he frowns on writer’s groups. (Oh no, am I diluting my work?) He ‘drifts into dream-like silence,’ and has low-tech habits to become more intimate with his characters.

Also in November’s issue, we have Amor Towles, author of NYT Bestselling Rules of Civility, in an interview, referencing a novel that was a ‘dud’:

. . .because he had not carefully out outlined in advance, Towles knew his unpublished novel set in Russia had little chance of success. He approached his next book with a fresh strategy, allotting himself 52 weeks to write a 26-chapter novel.

On not waiting for inspiration and perseverance, Towles says:

“ . . . eventually you can get lost in the process and creative function takes over.”

October’s issue of The Writer offers “6 reasons a workshop jolts your writing.” (Ah, sweet relief, I can remain with my much-loved writing group.)

Also in the October issue is Bram Stoker award winner Jonathan Maberry, who stresses the need to “stop mythologizing the life of a writer. Don’t wait for the must to whisper in your ear . . . A writer is no different that a plumber, a landscaper or a dental hygienist.”

Also in the October issue is Bram Stoker award winner Jonathan Maberry, who stresses the need to “stop mythologizing the life of a writer. Don’t wait for the must to whisper in your ear . . . A writer is no different that a plumber, a landscaper or a dental hygienist.”

I believe in the power of advice. (My “Homemade MFA” was based on reading shelves of book on writing.) But, though there are some absolutes (always end a sentence with some form of punctuation would seem a good rule) one must find the balance between advice that bewilders or makes one feel less senseless and that which leaves us enriched. Perhaps this is also the danger of taking writing courses with a teacher who expounds on a one-way-to-paradise approach. Imitation is not always the wisest course. Truman Capote, Patricia Highsmith, and Marcel Proust, according to Daily Rituals: How Great Minds Make Time, Find Inspiration, and Get to Work: How Artists Work by Mason Currey, “all wrote worked in bed, surrounded by a cocoon of food, alcohol and cigarettes.”

However, those habits were not the fount of their success.

Stephen King, often used as gold standard for the not-outlining group, says he plots in advance “as infrequently as possible. I distrust plot for two reasons: first, because our lives are largely plotless, even when you add in all our reasonable precautions and careful planning; and second, because I believe plotting and the spontaneity of real creation aren’t compatible.”

Aaron Hamburger began a January 2013 essay in the New York Times online “Opinionater” with the words, “In my experience, one of the surest ways to kill the creative energy of a work of fiction at its inception is with an outline.” (He believes in reverse outlining.)

Had I read that when as I settled into my first published novel I might still be floundering. (Although I do reverse outline—but I also do it in forward.) For me, an outline (and everyone has a different idea of what constitutes an outline—mine is formulating one third of a book at a time) provides the freedom to be as creative as I want. If I go ‘off-outline,’ that’s okay, but I have my security blanket.

Justin Cronin says “There’s an outline for each of the books that I adhere to pretty closely, but I’m not averse to taking it in a new direction, as long as I can get it back to where I need it to go.”

Khaled Hosseini states “I don’t outline at all; I don’t find it useful, and I don’t like the way it boxes me in. I like the element of surprise and spontaneity, of letting the story find its own way.”

R. L. Stine swears “If you do enough planning before you start to write, there’s no way you can have writer’s block. I do a complete chapter by chapter outline.”

Jeffrey Deaver is pro-outline: “The outline is 95 percent of the book. Then I sit down and write, and that’s the easy part.”

Diane Galbadon is not: “I don’t plot the books out ahead of time, I don’t plan them. I don’t begin at the beginning and end at the end. I don’t work with an outline and I don’t work in a straight line.”

The head spins, but my guess is that few writers truly fit into a rigid guideline:

I always have a basic plot outline, but I like to leave some things to be decided while I write. J. K. Rowling

Perhaps the ‘outlining debate’ was best answered by Joseph Finder, who wrote:

“Outline or not?

This is the question I get most of all, whether by e-mail or at conferences: Do you outline or not?

It’s a good and important question, and here’s the thing: There’s no Right Answer. All of us writers make up our own rules as we go along. There’s no one way to do it.’

Except perhaps for the recent advice from Between The Margins own Juliette Fay, who wrested me from a book stymie by advising something that will always live with me:

So get your whiny hiney in that chair and produce some verbiage, you big baby.

The only magic rule to which we must all adhere.

October 2, 2013

Signs You May Be In An Abusive Relationship

October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month.

When I worked with batterers, people always asked why the women stayed. Why didn’t they ask why the offenders were violent? Is it because it’s easier to blame the victim? Is it because these abusive men scare us as much as they scare their victims, so it’s easier to confront them?

Women (and I mainly talk about women—because my experience is all with male abusers and female victims) often don’t recognize patterens of abuse until they are in so deep that escaping takes more money or power or strength than they can muster. Abusive people usually know how to put the glitter out in the beginning. Few fall in love with the abusive partner–we fall for that funny, charming, attentive guy. Then, when the warning signs start, and we chafe against it, he knows how to bring back that funny, charmer when it’s needed. Or the sad “no one but you understands me” guy. And the “forgive me, this will never happen again–and I’ve never loved anyone like I love you” guy.

Pay attention to the warning signs that you may be in an abusive relationship. ( And remember, though these warnings are written in the guise of straight man/straight woman, abuse knows no gender or sexual preference boundaries:)

Jealousy: Does he want to be with you constantly? Accuse of you cheating? Follow you? Call far too often?

Controlling Behavior: Does he become angry if you’re late, always need to know who you were with, where you went, what you wore, and what you said? Do you have to ask permission to do things? Does he want veto power over your friendships?

Instant Involvement: Be careful of a man who claims ‘love at first sight’, and says that you are the ‘only one who can make him feel this way.’ Be cautious of a man who pressures you for commitment too quickly, perhaps suggesting that you move in together or become engaged within 6 months of meeting.

Unrealistic Expectations: This may seem strange, but compliments that seem excessive are a warning sign. Beware those who see or expect perfection, and those who say, “you are all I need; I am all you need.”

Isolation: Controlling and abusive men will try to cut off your resources and distance you from your friends and family, perhaps by telling you that your family doesn’t love you or that you are too dependent on them. They will say your friends are stupid. They will keep you from the car, get angry when you talk on the phone, and make it difficult for you to go to school or work.

Blames Others for Problems: For controlling and abusive men, any problems they have at school or work are always someone else’s fault. In the relationship, anything that goes wrong is because of you. They consider themselves a victim in almost all circumstances.

Blames Others for Feelings: Beware of men who make you feel responsible for how they feel, who see everything as a personal attack, are easily insulted, and who have tantrums about the injustice of things that happen to them. Abusive men will look for fights, blow things out of proportion, and overreact to small irritations.

Disrespectful or Cruel to Others: Dangerous men will punish animals and children cruelly. They are insensitive to pain and suffering and have expectations of children that surpass abilities. They tease children until they cry and treat people disrespectfully.

Use of Force During Sex: When men show little concern over whether you want sex or not and use sulking or anger to manipulate you into sexual compliance, this is a warning sign. Degrading sexual remarks about you should be taken as indication of a serious problem.

Rigid Sex Roles: Abusive men often believe that women are inferior to men and that a woman cannot be a whole person without a relationship.

Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde: Beware of men who are nice one moment and explode the next, and men who have rapid and extreme mood swings.

Past Battering: Abusers will deny and minimize their past violence, saying it is a lie, or their ex is crazy, or that is wasn’t that bad.

Breaking or Striking Objects: Violent men will break things, beat on tables, throw objects, and use other methods to inspire fear.

Any Force during an Argument: No one should be physically restrained, pushed, or shoved. Any use of weapons, kicking, hitting, slapping, or other physical violence is abuse.

Let’s all stay safe out there.

If you need help:

National Domestic Violence Hotline

Help For Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgendered Community

September 30, 2013

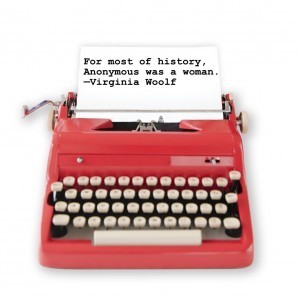

Sexism, Name-Calling & Deniers in Writing: Which Side Are You On, Gentlemen?

Like a compass needle that points north, a man’s accusing finger always finds a woman. Always.—Khaled Hosseini

A few questions:

Why do some folks get in such an uproar when women simply ask for a fair shake, equal footing?

Why does anyone think women writers are exempt from institutional sexism? The Mad Men era was not long ago. The 19thamendment to the constitution, giving women the right to vote, was only ratified in 1920. Help Wanted ads were segregated by gender into the seventies.

Why are folks surprised when women don’t find screenwriter Seth Macfarlane satirical when he dismisses the breathtaking film The Accused, in which Jodie Foster plays the victim of a horrific gang rape, by noting that he got a look at a Foster’s breasts.

Rage against incidents like this is comes out time and again—so why do male writers who insult women writers continue to act surprised when there’s a backlash? Why do they then blame their words on (choose one) the interviewer, the women-without-senses-of-humor, or the cabal of angry women-commercial-writers? Does this come from the same instinctual place of those who, each time I write about domestic violence, whine and scream “women do it too!” as though, in fact, two wrongs ever did make a right?

Does it stem from the reasons listed in the comic-truth of “5 Ways Modern Men Are Trained to Hate Women?” where the author divulges:

“women took it all away .. . This is why no amount of male domination will ever be enough, why no level of control or privilege or female submission will ever satisfy us. We can put you under a burqa, we can force you out of the workplace — it won’t matter. You’re still all we think about, and that gives you power over us. And we resent you for it.”

Historically, white guys always had the better shot at topping the ‘smart writer heap.’ Writers who should know better brag (usually including—wryly—the words “I know this isn’t politically correct”) about reading only “dead white guys,” as though proving their can’t-be-beaten-out-of-them intellectual prowess. (I often wonder whether these writers would be okay if only dead people bought their books.)

Dismissive remarks against women writers make sense in the context of men (consciously or not) guarding their places in line, those hoping to enter the realm of becoming a ‘canonical writer.” Eons of privilege afford men a better shot at early admission to the canon. Who among us wants to lose power? Better to dismiss the idea that the power differential exists, or to be intellectually snide, than give up one’s that upper rung on the literary hierarchy. Power threatened engenders hostility, or, worse, outright hatred, as seen in Michelle Dean’s list on Flavorwire’s of “7 Breathtakingly Sexist Quotes by Famous and Respected Male Authors,” which includes these words from Norman Mailer: “A little bit of rape is good for a man’s soul.”

And yes, that a male writer exploring relationships and family is likely to be considered groundbreaking and a woman’s book on the same territory is called ‘women’s fiction,’ is a part of the equation. Can we equate snide comments, a pink glittery book cover vs. a moody shot, to violence against women and the recent war against women? Maybe yes, maybe no, but we can plug it right into the canon of micro-indignities which keep women from recognizing that they are entitled to half the sky.

Each comment, each dismissal of reality (see the Vida Count if you want more facts and figures) is another slice in the death of a woman writer’s esteem by a thousand cuts. Who’s holding the knives and why?

There is The Bragger:

In an interview with award winning novelist, David Gilmour, who also teaches literature at the University of Toronto, Gilmour says:

“I can only teach stuff I love. I can’t teach stuff that I don’t, and I haven’t encountered any Canadian writers yet that I love enough to teach. I’m not interested in teaching books by women. Virginia Woolf is the only writer that interests me as a woman writer, so I do teach one of her short stories. But once again, when I was given this job I said I would only teach the people that I truly, truly love. Unfortunately, none of those happen to be Chinese, or women. Except for Virginia Woolf. And when I tried to teach Virginia Woolf, she’s too sophisticated, even for a third-year class. Usually at the beginning of the semester a hand shoots up and someone asks why there aren’t any women writers in the course. I say I don’t love women writers enough to teach them, if you want women writers go down the hall. What I teach is guys. Serious heterosexual guys. F. Scott Fitzgerald, Chekhov, Tolstoy. Real guy-guys. Henry Miller. Philip Roth.”

All this pitting of sex against sex, of quality against quality; all this claiming of superiority and imputing of inferiority, belong to the private-school stage of human existence where there are ‘sides,’ and it is necessary for one side to beat another side, and of the utmost importance to walk up to a platform and receive from the hands of the Headmaster himself a highly ornamental pot.— Virginia Woolf

Often seen? The: “Oh, yeah? Well it’s worse in other places!”fellow:

Frank Bruni wrote a thoughtful NYT piece regarding “Sexism’s Puzzling Stamina,” reflecting on, “. . . all the recent reminders of how often women are still victimized, how potently they’re still resented and how tenaciously a musty male chauvinism endures. On this front even more than the others, I somehow thought we’d be further along by now.”

Jonathan Franzen responded to Bruni (who referenced VIDA’s research on the disparity of women’s work being highlighted in the media) with a letter to the editor which included following:

“There may still be gender imbalances in the world of books, but very strong numbers of women are writing, editing, publishing and reviewing novels. The world most glaringly dominated by male sexism is one that Mr. Bruni neglects to mention: New York City theater.”

It is puzzling why a famed writer wastes time defending statistical disparity by saying “it’s worse in other fields.” Really? What is behind the odd defensiveness?

When all else fails, there is always the role of The “Name-caller”

Jeffrey Eugenides, given the chance (in the midst of a swell of coverage of his newly released novel The Marriage Plot) to reflect on gender disparity, responds to the interview question “Would “The Marriage Plot” have had a different cover if it was written by a woman? Something pink or frilly or less serious?” with:

“As a male you can never know and you’re not supposed to talk about it. But I have lots of female literary novelists who I don’t think would agree. I’m friendly with Meg Wolitzer and she was a big fan of “The Marriage Plot,” and she wrote something about this, and especially about the treatments of the covers. I wondered about that, if that might be true, if women get treated differently in the way that their covers are marketed. You know, it’s possible.

To me, it was a little bit … I didn’t really know why Jodi Picoult is complaining. She’s a huge best-seller and everyone reads her books, and she doesn’t seem starved for attention, in my mind — so I was surprised that she would be the one belly-aching. There’s plenty of extremely worthy novelists who are getting very little attention. I think they have more right to complain. And it usually has nothing to do with their gender, but just the marketplace.”

Belly-aching? Nothing to do with gender? Has he seen the numbers? Has he heard of the pink ghetto of women’s books on domestic drama vs. the treatment men get writing on the same topic? Does he know about the ‘cover flip?’

Why the denial of reality?

And one can always become a “Name it and it shall be true!”declarant

VS Naipaul, a winner of the Nobel Prize for literature, considered one of the greatest British writers of his generation said in an interview that no woman writer could be his literary equal; that Jane Austen’s “sentimental sense of the world” made her his inferior; “I read a piece of writing and within a paragraph or two I know whether it is by a woman or not. I think [it is] unequal to me.”

I’m not concerned with your liking or disliking me… All I ask is that you respect me as a human being.—Jackie Robinson

Chuck Wendig wrote an essay titled “25 THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT SEXISM & MISOGYNY IN WRITING & PUBLISHING, where he reaches out to other men with the words: “I hate to borrow a twee saying from our Masters at Homeland Security, but when you see inequality, it’s time to kick up some dust, time to throw a little sand. To borrow another twee sentiment: all evil requires is for good folks to stand by and do nothing. All sexism needs to thrive is for good people to do the same.”

Wendig recognizes that this is not a women-writer issue, literary-writer issue, commercial-writer, genre-writer or any-slice-of-writer issue: it is a writer issue. Perhaps I should paraphrase the tweet by K. Tempest Bradford, in response to a shower of sexism in the literary world of science fiction and fantasy:

“This would be a good time for the men who write science fiction who aren’t douchecanoes to step up and tell the other dudes to go to hell.”

Bradford’s call was well answered by Jason Sanford:

“We’re tired of your sexism and hate. Clean up or ship out. You’re holding back the genre we love. And it’s time for the men of SF to step up and also say this behavior is not acceptable.”

Thanks, Jason.

So, to borrow from Bradford: Can you help handle the gentlemen, guys? Your friends, daughters, girlfriends, wives, and mothers are wondering—which side are you on?

Deliver me from writers who say the way they live doesn’t matter. I’m not sure a bad person can write a good book. If art doesn’t make us better, then what on earth is it for. Alice Walker

September 27, 2013

Novels About Novelists

Does everyone have sub-genres within genres for which they hold an unusual fondness?

I can’t resist a good infidelity story (really, can anything beat Presumed Innocent by Scott Turow?) I can rarely refuse the intricacies of inter-racial love (Meeting of the Waters by Kim Mclarin,) or a memoir about substance abuse (Drinking: A Love Story by Caroline Knapp. I treasure reading about the layers of an unknown (to me) culture (A Fine Balance by Rohintin Mistry) or the heartbreak of emigrants navigating a new world (my current audio/car book is Shanghai Sisters by Lisa See,) but for a real roll in schadenfreude reading, I pick up a juicy novel about novelists.

Grub by Elise Blackwell: I ate up this Shakespearean ‘all’s well that ends well’ satire, described as a “a long overdue retelling of New Grub Street—George Gissing’s classic satire of the Victorian literary marketplace—Grub chronicles the triumphs and humiliations of a group of young novelists living in and around New York City.” This book reminds writers to watch the hubris and check literary-attitudes at the door; but it does it with tender love and great humor.

Breakable You by Brian Morton: All of Morton’s novels reveal the writer in his/her quirks, foibles, and often-unattractive hunger—though never callously. It’s hard for me to pick just one of this author’s books, but I found it most memorable for the story of just how far a writer might go to gain glory, and what it life might be as the wife, daughter, or friend of such a writer.

Read all of his books.

How I Became a Famous Novelist by Steve Hely: This broad satire of Pete Tarslow, a lost soul who sets out to write a novel to impress the woman who dumped him, somehow meets what seem like disparate goals by portraying a character who is a naïf attempting to be Machiavellian. Hely skewers self-importance with a broad gun. This is a fast and funny read. Treat yourself after the holidays: spend New Year’s Day reading this.

Misery by Stephen King: Page-whipping layered with psychological insight, this is a book that will not be put down. Publisher’s Weekly said: “a writer held hostage by his self-proclaimed “number-one fan, is unadulterated terrifying. Paul Sheldon, a writer of historical romances, is in a car accident; rescued by nurse Annie Wilkes, he slowly realizes that salvation can be worse than death.”

The Bestseller by Olivia Goldsmith: This fun and gobble-it-down tale for authors is described thusly by Publisher’s Weekly: “It’s is an old adage that books about publishing do not sell, because those likely to be most interested will beg, borrow or steal them rather than buy. In the case of the latest by Goldsmith (The First Wives Club) that would be a pity, because it is a highly entertaining tale with a good share of romance and drama, considerable humor and some cynical fun at the expense of the book business; there are many recognizable characters, and a number of real-life walk-ons. (There’s even an index so book people can look themselves up, but be warned: it is not what it seems.) Goldsmith’s busy plot which makes publishing seem as glamorous and crazy as fashion or the movies (settings for two of her previous books)? offers four women with novels being considered by high-powered New York publisher Davis & Dash. There is an elderly romance queen with a fading readership; a proud mother trying to get someone to read a magnum opus by her dead daughter; a cool young Englishwoman who has penned a quirkily charming book about a busload of American tourists in Tuscany; and a desperate young woman whose devious husband is trying to steal all the credit for her true-crime roman a clef. Throw in a corrupt publisher doctoring the books to try to make his own sales look bigger, a nymphomaniac and alcoholic editor-in-chief, a staunch young editor and her lesbian agent friend, and you have the makings of a spicy literary stew.”

Fun, huh? Can you see why I had to include almost the entire review? Sadly, the book is out of print (the author, Olivia Goldsmith died six years ago) but it’s well worth getting from the library or ordering second-hand.

September 9, 2013

After You Sign The Publishing Contract: What Comes Next?

Imagine this: Someone asks you to marry them, and because you are so eager (desperate?) to wed, you say yes—even though you don’t know them, don’t know what they expect, and don’t know what they’ll bring to the table besides the (gender-free) shiny ring they push up on your finger.

That’s kind of what it’s like the first time you enter a contract with a publisher. Perhaps some of you were a whole lot smarter and you knew what was coming, but more likely you resembled me: naïve, starry-eyed, gasping with disbelief and playing the Sally Field card: You like me, you really like me, twirling in a circle of happiness, kissing your agent through the phone, and having no idea what came next.

So what should you expect? What’s going to happen first, second, and third? It drove me crazy not to know (when I published my first novel.) I’m an excessively need-to-know-everything person, which led to me driving my editor and agent crazy, which led to co-authoring a guidebook What To Do Before Your Book Launch with M.J. Rose. Because along with our mutual need-to-know, is a need-to-share. This overview of the basic steps your publisher will likely take after your contract is signed comes from that guide.

Every publisher’s timeline is different; within your publishing house, every editor is different, and every client at that house will get different treatment. With that as given, here’s what you can expect from your publisher after you get that first check:

1. A launch date will be set. It can be a year to eighteen months (or a little more or a little less) ahead depending on the book and the house.

2. Your editor will provide editorial comments to guide you in your first revision. This process could take anywhere from one step to many iterations, as you and your editor go back and forth.

2. Your editor will provide editorial comments to guide you in your first revision. This process could take anywhere from one step to many iterations, as you and your editor go back and forth.

3. Your editor will accept the final manuscript and send it to a copy editor.

4. You’ll get your second check.

5. About 6–7 months pre-launch your editor will be presenting the book internally at a launch meeting to various departments, such as: Sales, Special Sales, Design, Marketing, Publicity, Audio and Subrights.)

6. Cover design will begin. (And later you’ll get to approve a final.) This will also happen 6–7 months before publication—usually after that internal launch meeting.

7. You’ll receive a copy-edited manuscript—with a deadline. In time you’ll get second pass pages and sometimes third. With each subsequent set of pages, you will be ‘allowed’ to make less changes, so be thorough.

8. About 5–6 months pre-publication you will be assigned a publicist and a marketing person. This is usually 6–7 months pre-launch.

9. Discussions between you and your editor about who to get blurbs from will be initiated. Never be afraid to ask your editor and agent to help here if you don’t feel comfortable asking other authors yourself.

10. Galleys (advance reader copies aka ARCs) will be sent out for reviews and blurbs. This is usually 4–6 months prepublication. (You will get you own ARCs—best used for those who will help spread word of the book.)

11. At the 4–5 month pre-publication point your editor will present your book at a sales conference to all the sales reps. You should get a copy of the sales catalog including your book.

12. Once sales conference is over, marketing and PR plans will be finalized and your editor will be keeping you up to date about what the house is going to do for your book.

13. About 3–5 months pre-publication, early reviews from the trade will start to come in.

14. About 2–3 months pre–publication, you should be working with marketing and publicity to set up plans.

15. About 6–8 weeks pre-publication your editor will send you the first finished book.

(The above information was taken from WHAT TO DO BEFORE YOUR BOOK LAUNCH, which also contains a timeline author tasks in the year before a book comes out, along with all other aspects of launching a book.)

August 5, 2013

The Battle Between The Wind & The Sun

Long ago, the Wind and the Sun quarreled over who was stronger. Upon seeing a traveler coming down the road, the Sun said: “Now we can end our dispute. Whichever of us causes that traveler to take off his cloak shall be regarded as the victor. You begin.”

The Sun retired behind a cloud.

The Wind blew, blustered, and raged upon the traveling man, but the harsher he blew, the tighter the man wrapped his coat. At last, exhausted, the Wind gave up in despair.

The Sun came out and blazed in all her glory upon the traveler. Soon the man tipped his face up to the warmth. He removed his coat and basked in the Sun’s rays.

Kindness effects more than severity.

Persuasion is better than Force.

Warmth wins more true followers, love and loyalty than punishment.

(A favorite of mine, adapted from Aesop’s Fables)

August 2, 2013

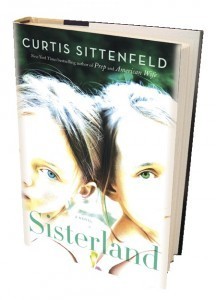

Book Love from Kris in Brattleboro: What I Loved About Sisterland

When I’m lucky, I get an email from my friend Kris Alden, the smartest, fastest, and most intensely loving reader of books I know. This week I got lucky:

There are few authors who can write about sibling rivalry; ESP; racism; society’s condemnation of stay at home parents; senior citizen sex; natural disasters, adoption and same sex relationships in one book and turn those dissonant topics into a riveting and provocative story.

Curtis Sittenfeld, the author of Sisterland is on of those authors.

Vi and Daisy (aka Kate) are twins who share more than their looks. They are both psychic or have the “senses” as they call it. Daisy wants nothing to do with this dubious gift and spends much of her life stuffing her abilities down into a shadowy shameful place. Vi, on the other hand, welcomes this opportunity to be the different one and thrives on the celebrity that her powers bring her. Their lives are on opposite ends of the spectrum: Kate (as she is now called) is a stay at home mom—a loving and devoted albeit somewhat bored wife and is determined to live a “normal” life.

Vi—in and out of doomed relationships and reluctant to admit she is a lesbian—flaunts her abilities and the attention, good or bad, they bring. Her prediction of a devastating earthquake bring a storm of media attention and hate mail down on both sisters with surprising and long lasting results.

As in her previous books, Sittenfeld appears to have no need for us to like her characters. Most of her characters are painted with a wide swath from the same unlikeable brush. She only requests—and is given—a curiosity that will keep us wanting to know what happens to these people next.

I was wary of this book (as I am of most books about psychic abilities.) Not because I don’t believe that some people are given the ability to know things in this world that most of us don’t. I do believe that. But, because most fiction about this subject is predictable, clichéd, and written in a way that, even if you wanted to believe, you just couldn’t get past the “Twilight Zone’ aspect of the writing. Sisterland does none of those things. It’s a story about two sisters growing up in a less than perfect world who have something very special to either embrace or run from. It’s a story about the struggle to find your place in the world. And, mostly, it’s a story about learning to live with the consequences of our choices. And that is often hard to do.

Kris has had a lifelong love affair with the written word and one of her fears is that the world will run out of books before she is done reading. When she isn’t creating collages, reading or thinking about reading, she runs a personal chef service, “Someone’s in the Kitchen.” She adores being a grandma; her kids, her friends, her cats, her art and oh, yeah...her books. She can be reached at Potluck3@gmail.com.

July 25, 2013

Distracted, Tired, Worn-Out: Writing the Darker Side of Parenthood

Between pretending to be perfect mothers and the reality of flawed (real) moms lay murky truth: We always love our children; we don’t always love being mothers. We’re M&M’s, our shells of goodness covering malleable centers of insecurity, always seeking evidence we’re not alone.

Great books of being raised by evil parents abound; rarer are authentic stories of imperfect mothers, written without cover of apologies for the character’s negative thoughts like, She’s drunk! She’s crazy! I understand this all too well. Writer-mothers also fear judgment, and who’s less revered than bad moms? But oh, how soothing to learn one’s not alone in ambivalence. We need reminding that feelings don’t equal actions, and that angry inside thoughts (even while murmuring soothing words to a screeching infant, calming a toddler in midst of a tantrum, biting back screams while coping with surly fourteen-year-olds) don’t define us.

A million things engender inside thoughts: Our checkbook’s empty. We hate building Lego castles. Maybe we’re divorced and distracted by fantasies of sparkly sex with a new beau—or simply too exhausted from a day of working at home or outside to make a single pan of brownies for that class party.

Novels capturing these moments from the mother’s point of view saved me when my children were small. Books like I Don’t Know How She Does It by Allison Pearson and Jump At The Sun by Kim McLarin. Brave writers led me through the thicket of motherhood ambivalence. Even now, with grown children, I feel the push-pull of parenthood and work. Mothering isn’t just a 24- hour job, it lasts a lifetime, and there’s always more you can give, no matter how old your children. Toni Morrison said it in Beloved: “Grown don’t mean nothing to a mother. A child is a child. They get bigger, older, but grown? What’s that suppose to mean? In my heart it don’t mean a thing.”

I had my first daughter at 21; I don’t remember what it’s like to be an adult without children. How could I not write about mothering? Memories of revelatory books still bring comfort, but writing the core of raising children may be the toughest write of all. We’re not forgiven transgressions of motherhood. Saying everyday truths aloud—stretch marks, boredom—is difficult, but the harder truths sometimes feels impossible. How to reveal that the health, happiness, and success of our children make or break us every day and forever? Done right, motherhood begs the question, “Do you mind stepping aside for a lifetime? This is the truth I want to tell.

July 13, 2013

An Instant Shrink for Writers

The Ambivalent Writer, The Natural, The Wicked Child, The Self Promoter, The Neurotic: which one are you? These are the first five chapter titles of Betsy Lerner’s (agent, writer, editor) book, The Forest for the Trees. It was first published in 2000, and I’ve probably read it yearly since buying it. (Note picture of worn book reflecting clutching, bathtub reading, and talismanic lifting to heart, kissing, and offering to God.) Now a revised version has launched.

Lerner’s book will always be on top of my constantly changing top ten writing books list. Not because it teaches one better ways to write, not because it teaches one how to navigate the shoals of publishing, and not because it will teach you a guaranteed way to get an agent (though it will help with all the above) but because it takes you to the other side of the desk and holds up a mirror. An unflinching mirror held in a sympathetically lit room.

Lerner holds your hand; she interprets your dreams (and the meaning of query responses) and scolds when needed. In other words, you’ll get a writer’s shrink for the cost of a trade paperback.

Most notable, is Lerner’s writing. Clear as water, cool as the same, and welcome as a brownie to a food addict, her words entertain, teach, and soothe. Plus, very important for someone (um, me) who will cry at the slightest sense that someone actually does not like her, Lerner does not scold.

I’ve gone back to Forest for the Trees through every stage of writing: While writing the (many) books that landed in the drawer, while writing the book that almost made it, and finally, blessedly, while writing the book that got published.

When I searched for an agent, I read this book as though searching for the missing link of humanity. When I searched for a second agent (after the literary divorce,) yes, back to Betsy. When I got the agent, when she sold my book, when I tried to figure out what my editor was thinking and why the entire publicity didn’t have me on speed dial: Betsy, Betsy, Betsy.

Forest for the Trees was my long term Effexor, my short hit of Xanax, and my glass of wine and I recommend self-medicating two ways: 1) take as needed. 2) Read minimum once per annum.

(SUMMER RE-RUN)