Randy Susan Meyers's Blog, page 33

June 26, 2013

“Is That Character You? Your Husband? Your Sister???” No: It’s The Butter In The Cookies

There something a little creepy about knowing that when friends, family, neighbors, and mailman read the novels I wrote, that they’re probably thinking: So that’s what she thinks about when she has sex! Oh, that’s how she really views her kids! My God, she lies to her husband?

No matter how much I insist that no, the mean cheating husband is not really a faintly disguised version of my husband (or ex-husband), I’m quite sure that their nod of agreement translates to, Sure. I just bet.

How to explain a writer’s joyous transmogrification of demons into fiction? How to tell someone that no, that is not my mother, my sister, my husband, but a stew of the emotions and fears and love that I’ve absorbed. Philip Roth said it well in an interview (that I can’t locate) where he explained how it was the very goodness of his mother that allowed him to write about awful mothers. I understood that so well, because it was only after I entered a warm loving relationship that I could explore the darkest parts of myself without fear.

I’ve tried to explain my work process, in answer to those knowing glances about my characters: No. It’s not me—it’s nuggets of all my fixations blown up into a world of crazy. It is, as I recently read in The Nobodies Album, a novel by Carolyn Parkhurst, the butter that I can finally put in the cookies, a phrase from Parkhurst’s main character, a writer, who muses:

“There’s an analogy I came up with once for an interview who asked me how much of my material was autobiographical. I said that the life experience of a fiction writer is like butter in cookie dough: it’s a crucial part of flavor and texture—you certainly couldn’t leave it out—but if you’ve done it right, it can’t be discerned as a separate element. There shouldn’t be a place that anyone can point to and say, There—she’s talking about her miscarriage, or Look—he wrote that because his wife has an affair.”

I hope I never forget the phrase (and that I always give proper thanks to Ms. Parkhurst) about “the butter in cookie dough”. What a perfect capture for fiction—taking the elemental issues with which one struggles, giving those problems to one’s characters, and kneading those thorny emotional themes that haunt into the thoughts, minds, and actions of those characters until, hopefully, you can beat that sucker into submission.

Then move on to the next one.

How do you explain to a neighbor that your lifelong struggle with a mother obsessed with vanity became a character’s need to re-invent herself as a cosmetic tycoon? That your daily struggle with weight grew into a character’s morbid obesity? That your lonesome childhood morphed into a Dickensian orphanage?

How do you answer the questions, “Where did you get that idea?” There’s not a book club I’ve visited that hasn’t asked me that question about my book, and while the answers I give are honest: a childhood incident, the work I’ve done, a letter to the editor I read—those are the answers about the book’s recipe. Now, thanks to Pankhurst, I have the answer to how the emotions marbling the story really came about:

It’s the butter in the cookies.

June 14, 2013

My Father Bought Me Pretty Shoes

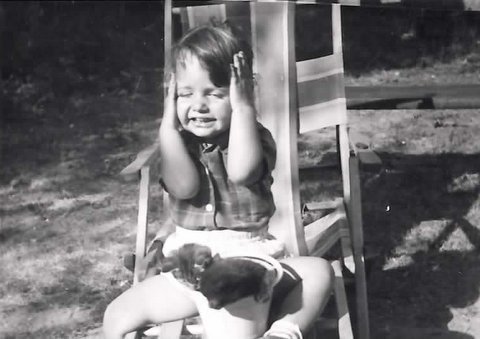

I dreaded Father’s Day as a child. Every year (during those far less aware days) we were asked to make a card for our father as a classroom project. My father died when I was nine, so from that day forward I made cards for my grandfather, embarrassed by my lack.

Most of what I’ve written about my father has been unhappy snapshots based on memories I’ve inherited or been given. Once he tried to kill my mother . He drank to excess and when he did, he became (according to my cousin who saw more than I did) quiet, sometimes angry, depressed or sullen. According to others, he took pills. Many of them and they were the cause of his death at 35.

I don’t know much about my father. He served in World War II. In Africa. He was responsible for something to do with writing. In the photos he sent back to my mother he was often wearing a bathing suit and he typed messages on the back of them. As a fatherless child (who hadn’t yet uncovered any family secrets) I read the simple sentences on the back of those photographs as though they held the secrets of the universe; trying to know out who my father was through those eight or ten words. He compared the beaches of Africa to Coney Island. He wrote funny messages to my mother; in my mind, I pumped up those messages until they became sonnets.

I have heartbreakingly warm memories of my father, despite the family history. I don’t remember him high or drunk. When I cried, he told me to “stop the banana splits” and then bought me something special. (I don’t remember why I was crying. I know it was on a weekend I spent with him, my sister, and my grandparents. He and my mother were divorced.)

He played ragtime on the piano. He seemed to love me. He seemed sad. All the time.

After he died, no one ever mentioned him again. When I was old enough to be less afraid of upsetting my mother, I tried teasing bits information from her.

All she professed to remember was that she married him because he was handsome. And everyone was getting married. So I hold onto the love I feel for no reason I can truly remember, except that he once bought me pretty patent leather shoes with straps you could swing to the back.

When he fought in WW II he was so young—perhaps 21? He was handsome. He played the piano. He fought in World War II when he was barely in his twenties. And when I cried, he noticed.

June 6, 2013

Rescuing Children With Happiness

Being invisible is pretty hard for a kid. Crummy childhoods take many forms and usually it’s an amalgam of yuck. Smacks and screams thankfully have a time limit, but neglect is the evil gift that never stops.

Even the most benign neglect—like being a latchkey kid—can foster loneliness.

When trouble fills a family, kids are pushed to the background. I lived in a land of my own imagining, where I believed my real parents, President Kennedy and Jackie, had left me to fend for myself, testing a ‘cream will rise to the top’ theory. Meanwhile my beleaguered sister, by nine, was trying her sullen best to cook me supper.

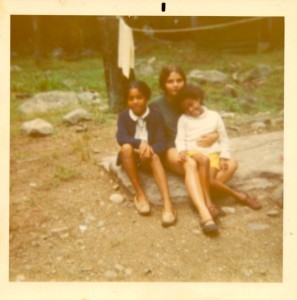

If it hadn’t been for the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies I doubt my sister and I could have ended up strong at the broken places. Our mom was a struggling single mother who did her very best. Our dad suffered in ways we’ll never understand, papering his sadness with drugs and dying at thirty-six.

But we had the summer! Through the magical generosity of the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies, we spent our summers at Camp Mikan, our paradise. We entered a bus somewhere in Manhattan’s Lower East Side and came out of the bus blinking in the sunlight and breathing the sweet green air of Harriman State Park. Sunshine! Swimming! Friends!

Visibility!

In memory, it was a Wizard of Oz transition from black and white to color. At camp we went from unnoticed to the coolness of being all summer campers. My sister became a big shot, a member of an envied clique, moving up the ranks of camp hierarchy until eventually she was head of the waterfront (only the coolest job in the world.) I became part of a pack of safely rebellious friends who kept me going through the lonely winters.

We got to be kids

I starred in Guys and Dolls. Jill gathered groupies! We hiked. Canoed. Short-sheeted counselors. Married head-counselors Frenchy and Danny taught me I could be lovable and through loving them I learned early on that interracial marriage was a non-issue. Luke Bragg taught me to get up on stage and from being with him, through osmosis, I learned gay or straight made no difference.

We got to be kids.

Women ran Mikan. They taught Jill and I that women were strong and loving and firm and trustworthy. They taught us that is was possible to be protected in this world.

Back home, we were once again invisible and quiet children cleaning the house, uncomplaining and obedient, waiting for the year to pass so we could again have a childhood. Summer came and once more we could swim, sing, mold clay, hit a ball, learn folkdance (I still dance the mizourlou in my mind) and unclench from being coiled watchers.

Doris Bedell, who ran the camp, shaped our lives more than she’d ever imagine. She loved us, she scolded us, and she made us feel seen. She probably helped my sister become the best teacher in Brooklyn. Her memory stayed with me when I ran a camp and community center in Boston.

Summer can save a kid. One person can offer a child enough hope to hang on. Think about this as we get ready to slide into school vacation.

One adult can change a child’s world.

Remember this.

Think of who you can touch.

Thank you Federation of Jewish Philanthropies. Thank you for my childhood.

(originally posted in 2010)

May 29, 2013

What Makes A Satisfying End?

Beginning a book is easier than ending it (at least for me.) A beginning is exciting and glittery, filled with excitement and hope. First sentences are sexy. They pop into my mind all the time. If I only had to write the first lines, I could write a million books

But then you have to end it.

Wrap it up.

Like a television finale?

Television shows are (unknown to many it seems—considering how much attention they are given) actually written. By writers. Writers can build characters that induce sympathy for the devil (Walter White in Breaking Bad) and then, if they choose, shatter that sympathy into distaste for the devil (Don Draper in this season of Mad Men.)

When, where, and how to choose that ending? That is the question.

End too soon and it’s rubbery, underdone. Blech. You want to spit it out–and who wants readers to spit out their books?

Do it too late and you got yourself some burnt book. Yech. Charred remains of blackened overdone gone-on-too-long just-like-this sentence endings. Do you want your readers to say “Thank God it’s over,” when they close your book? Television shows and novels are certainly different, but they’re from the same species. Stories–long, long stories, which at some point must end.

But how?

Fade out . . .ending?

The most memorable fade out?

The Sopranos.

The screen went black. Everyone thought something had gone wrong with their television. At the time, I found it enraging. With time, I’ve decided it truly worked. I certainly didn’t want to see Tony die at the end. No matter how awful he was, and how awful his deeds, the writers did a phenomenal job building sympathy for that devil and there was no place to go. Happy ending? How? This open-ended ending let us imagine either Tony’s just desserts or envision how, once again, a bad guy can get away with the most awful of crimes.

Take away? If you go for a risky ending, some will love you; some will hate you. This is an artistic decision—one your editor may fight to death to prevent, or, she will love it.

Horrible sadness?

Roseanne ended with Dan’s death. To me, it was an unfair ending, disrespectful of an audience who had fallen in love with this couple, with the family—with the conceit of the show. There really should be a rule: no killing off a main character as a way to wrap up a sitcom. Comedy, folks. We don’t come for the death.

Take-away? Don’t try turning a satiric comedy into a Shakespearean drama in the last chapter.

Upbeat everything is wonderful ending? Leaving a sense of future ending?

The other night I watched the final episode of The Office—a show I’ve always enjoyed for it’s slightly squirmy humor mixed with sentiment (and with the spice of some truly odd characters (Dwight, Angela, Dwayne) put head to head with ‘normal’ ones (Oscar, Pam, Jim.) It was a show that always poured equal measure of discomfort and romanticism. The ending satisfied—because it kept the promise of the show and took it too a conclusion that (for me) offered the satisfaction of tying up loose ends (will Dwight and Angela ever get together?) with a sense of a everyone’s lives going on in a forward motion.

Like the fractured fairy tale it always was, we were given a fractured happy ending, a joining of the Meta (bringing together the documentary film makers who’d been the off-stage members of the cast) with the day-to-day lives of the show members. There were no loose ends. We can leave these people without worry (even ever-depressed Tobey and round-heeled Meredith seem to have some hope, when we see then flirting in the background.)

A happy ending works and satisfies–but only if it stays true to the character’s quirks and story throughout. If The Office ended with Pam and Jim winning the lottery, it would have been like eating overly sweet cake. We’d get queasy…maybe even throw up.

Tying up all the loose ends ending?

Most satisfying television I’ve ever watched? Six Feet Under, where we saw each character through to their final moments. In a montage where I could barely blink for fear of missing a moment, in my memory I saw the ultimate outcome of every main character. Did I cry? I sobbed like a little baby. The episode wrung me out. In the best possible way.

Take-away? Keep track of all your story lines. You don’t have to follow your characters through to their death—but your plot lines should have some resolution.

Bleak ending? Why did I bother ending?

Seinfeld. Need I say more? No matter how much Larry David defends it, this was an ending that took a great show and flattened it like a pancake at the end. The finale felt as though the writer was having too much fun at the viewer’s expense.

Take away? I believe the writer has a covenant with the reader. You provide the best possible stories—they will bring you into their heart. And come the day you separate, the moment it’s time to say goodbye, do you want to break their heart?

Or do you want them to sigh, close the book with regret that it’s over, and think how they can’t wait for your next novel?

May 19, 2013

Collective Guilt vs Collective Fear

“Justice is better than chivalry if we cannot have both.”

-Alice Stone Blackwell

The Internet is a tricky beast. Sitting alone, cozy in ragged sweatpants, writing while curled on the couch, it’s easy to believe that you’re cloaked in isolation, even as you spill on that most public of forums. Thus, I hesitate before committing words online. After reading a recent well-intentioned post—about an SS officer—a piece written by a friend of a dear friend, an article meant in good will, I wrestled more than usual.

The essay focused on a particular slice of the copious research this first-generation American author did while writing a novel (which I have not read) about Germany before, during, and after WWII, from the point of view of a young German woman who falls in love with a Jewish man.

During her research, the writer (through her family ties in Germany) met with an elderly former SS officer—an officer and doctor— who the writer concludes was stationed on the front lines, not in a camp.

They met in the man’s home, where a German Mother’s Cross (a program begun by Hitler, encouraging German women to have more Aryan children, which yearly—on Hitler’s mother’s birthday—awarded women crosses centered with swastikas for fertility) hung on the wall, a menorah sat on top of a cabinet, and, in an album of wartime shots shared with the author, was a photo of the officer standing with Hitler.

The author doesn’t question these displayed and shown items: she doesn’t want to discomfort the family member who arranged the interview, upset the doctor’s wife, or continue the process of“collective guilt.” Perhaps the officer was forced into his role, the author suggests. The author herself was a victim of assumption, having been taunted by being called a Nazi because her parents were German.

Despite her sincere attempt to be fair (“who was I to judge him now?” she asks), after finishing the essay I was shaken. Badly. Before writing a comment, I spent hours pondering the wisdom of ignoring the post versus attempting conversation. I didn’t want to anger or insult the writer, or publicly ‘call her out,’ and thus hesitated to commit my feelings to public paper. Still, however well-intentioned, her words felt like slaps against my history. I couldn’t get the essay out of my mind.

Not writing didn’t seem like an option.

“It is obvious that the war which Hitler and his accomplices waged was a war not only against Jewish men, women, and children, but also against Jewish religion, Jewish culture, Jewish tradition, therefore Jewish memory.” ― Elie Wiesel, Night

Like most Jewish children born in the fifties, the Holocaust was a constant shadow. If the German generation born after WWII suffered from collective guilt, trying to cast off the shame of their parents and grandparents, or convince themselves or the world of the innocence of their parents and grandparents, the generation of Jewish children born of the same time, suffered from collective fear.

I didn’t grow up in a traditional Jewish family (if such a thing exists) by any stretch of the imagination. The first time I entered a synagogue was for a friend’s Bar Mitzvah. But I read voraciously, and from the time I received my ‘adult’ card at the Brooklyn Public Library, I was reading accounts—fiction and nonfiction—of the Holocaust. The non-fairy tales of my youth were The Diary of Anne Frank, Mila 18, and Night (which then morphed to Jubilee and Roots, as I conflated the horrors of slavery and concentration camps into one mass of fright).

I grew up with a sense of doom—partly from these stories I consumed, partly due to my own family’s silence (my paternal great-grandparents emigrated from Germany, but I never knew why) and perhaps partially the hours spent looking at photos my father sent my mother from his post in Africa during WWII. That vast wasteland of desert merged in my mind with the nuclear wasteland I envisioned thanks to those elementary school drills spent under my classroom desk—the desks meant to shield us come the nuclear attack.

I never knew whether it was more likely I’d end up a survivor of a bomb, cowering under a desk, or sleeping on a wooden plank in an Auschwitz-like camp. Sophie’s Choice haunted me after my daughters were born. When I received an engagement ring, my crazy first and unbidden thought was that I could sew it into the lining of my coat if I needed to bribe a guard or save a child.

“The schools would fail through their silence, the Church through its forgiveness, and the home through the denial and silence of the parents. The new generation has to hear what the older generation refuses to tell it.” ― Simon Wiesenthal

I worked for many years with batterers—men who were adjudicated into a program for domestic violence prevention, men who had beaten, hit, punched, and sometimes killed their wives. They sat and stared at me, denying with the most innocent of eyes the very crimes I had laid out in photos in front of me.

She ran into my fist.

I grabbed her arm and then she ran in circles around me, and that is how she broke her own arm.

She had a soft head, and that is why she died when her head hit the iron railing.

People ask if the men ever changed and my answer remains the same: only if they are able to face their crimes and cruelty. Denial, and the shame these men felt (whether shame at being caught, shame at hurting people they should have loved, or shame at their hidden crimes being brought into the bright sunlight), blocked their change. How do you change if you can’t admit what happened?

Questions of shame and guilt spill to the next generation in families where domestic violence occurs. Are children of abusers doomed to abuse or be abused? Can they inherit a denial of familial guilt, which prevents them from comfort in their own skin and belief in their memories?

Does awareness that your people were killed in vast numbers (for being Jewish, which you are) leave one forever frightened?

What does it do to the frightened, to have that past denied?

What does it do to the children of perpetrators of violence? How does one put together love for a parent even in light of feeling revulsion for the deeds they did or the beliefs they carried?

Should there be a scale of pain and justice here, for these generations now and future? Or should we accept that everyone is the star of their own show, that pain is always relative?

For me, it’s all in the truth. I take no comfort in lies, half-truths, and fairy tales.

I learned from my scientist husband that what is, is. This lesson crystalized for me when, after a lifetime of trying to run from facing issues of fluctuating weight issues, I learned truth could be freeing. Like most women, the size of my dress rules my mood, while at the same time I veil myself from accepting the reality of that number. Pictures where I looked like a whale? Bad camera. Skirts tightening beyond the ability to button? Must be shrinkage at the dry cleaners. Don’t think about those waistbands. Put on an elasticized skirt.

What is, is.

After a lifetime of avoiding the scale, I began weighing myself. And continued to weigh myself every day. And, knowing the truth, I lost weight.

When a nation faces truth, perhaps the psychic weight begins to fall away and collective guilt lifts. Recently a series on German television, Our Mothers, Our Fathers, gripped the nation. According to War History Online:

Reviewers have praised the drama for breaking new ground by showing how the Nazi system reached into every corner of life. Christian Buss, a culture editor for the magazine Spiegel, wrote in a review of the drama that while the question of Germans’ collective guilt had been resolved, the role of individuals remained unclear.

“Who has had the conversation with their own parents and grandparents about the moral failings of their elders?” he wrote. “The history of the Third Reich has been examined down to the level of Hitler’s dog while our own family history is a deep dark crater.”

I want to see this series. The closest I can come to leaving my fear is by understanding how a vast number of people turned to evil—and that they are willing to examine it right. Pretending that nobody in their family ever knew what was going on is far more frightening. If a tiny portion of a nation could truly commit such horrors with nobody knowing but the smallest handful of people—what hope does a frightened child have? If the grandchildren of American slaves are told, “nobody knew it was happening,” why should they believe it couldn’t happen quite easily again?

When I visited the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC the exhibit which most captivated me was a film of survivors talking about their experience—in specific, a man who said that while he was in the camps he thanked God each day in his prayers. I don’t remember the exact words, but the essence was this:

“What are you thanking God for?” he was asked.

“I am thanking God for not making me him,” he said, gesturing towards the guard.

There is pain in participating in evil—especially if one feels bullied into that involvement. Choosing a path of righteousness is always easier in one’s imaginings, but it’s also true that evil flourishes best in silence.

Compassion towards those who feel forced to participate in something as enormously evil as slavery or genocide (whether in Armenia, Rwanda, or Germany) is a kindness that can only be meted out when a perpetrator acknowledges his or her role. A wronged community needs justice and truth to reach reconciliation.

Anti-Semitism, racism, and hierarchies of cultural, racial, and religious power are alive and well. Compassion towards perpetrators of evil (and those who blinded themselves to the evil next door) must be leavened with keeping truth in place. Smothering reality with blankets of kindness is in the end no kindness: not if our goal is preventing future generations of children from living in collective fear.

May 11, 2013

Re-remembering Mothers

I never met a book by Ruth Reichl I haven’t loved, and my adoration continued with this book.

Where others were hearty meals, Not Becoming My Mother was a deceptively simple snack. (I’m certain that Ms. Reichl, former editor of Gourmet Magazine, would find a more elegant food analogy, but I, alas, am but a quick and dirty cook, though one who loves reading the work of educated ones—like Ruth Reichl)

In her previous books, the author consistently folded her cooking and restaurant reviewing skills into personal memoir—making a mixture with the consistency of magic. Her work has always been fascinating, down-to-earth, and erudite—and always offered the reader fascinating glimpses into the world of food and Ms. Reichl’s own intriguing life, which often included portraits of her sad, unusual, and, to the author, exasperating, mother.

This 110-page gem boils it all down to the author’s mother true story. It is not an apology for what she’s previously written. Or, perhaps, it is.

Any daughter whose lived her life under the thumb of her mother’s quirks and enraging mothering mistakes will fly through this book, reading of Reichl’s brave attempts to find out the truth of her mother’s life. She writes of living her life on “Mim tales”—a trait with which my sister and I can over-identify, having dined, perhaps too long, on a pathetic treasure trove of Mom stories.

But as I read the author’s unearthing of her mother’s truth (her now-realization of her mother’s eccentricities as representing being crammed into the tiniest of housewifery boxes and the narrowest of work roles) I found it hard to catch my breath, amazed at the author’s courage in uncovering her own perhaps lack of generosity towards her mother, and deeply admiring her ability to now find the heroic in her mother.

Because I was with her every step.

Like Ruth Reichl, I too berate myself for not managing to rise above the role of daughter to my mother, and become a woman and friend to her. However, perhaps when one grows up with a larger-than-life mother, that’s an impossible goal. Maybe only after death severed a relationship that held us so emotionally hostage that we spent our lives holding our breath, can we step back and offer perspective.

So, thank you Mom for being a role model of friendship, you who offered such a striking portrait of being a loyal companion to so many wonderful women.

Thank you Mom for showing such a flair for beauty.

Thank you for showing us the wonder and fun of work.

For laughing very hard. For always appreciating a good story. For your advice on men. And women.

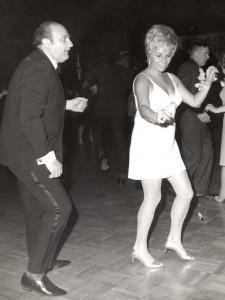

Yes, you were often right. About many things. And you lived your life working your ass off. And dancing like crazy–dancing so well.

We miss you. Happy Mother’s Day.

May 4, 2013

Give Mom Some Schadenfreude for Mother’s Day!

A few days ago, at an event at the incredibly wonderful Reading Public Library (in Reading Massachusetts) one of the librarians bought my book for her mother. For Mother’s Day. Using a large amount of not-usually-available-to-me control, I didn’t say any of the following:

“Nothing says Mother’s Day like cheating, anger, and hating-being–a-mother for Mother’s Day!”

In fact, that’s true. Who the heck wants to get Little Women on Mother’s Day? Not me. Does anyone want to psychically compete with Marmee?

No. I. Don’t.

I want to be feted with a pile of books that say:

Dear Mom,

This book is about a really troubled mother. This is a mother who truly effed up her kids. This mother is so much worse than you, Mom!!

Love,

Your fairly normal and grateful daughters.

With that in mind, five books that will tell Mom: You are so much better that these mom-characters. We could have been so much more screwed up! These are difficult complex (not necessarily bad, but not exactly who you want to rock you to sleep) mothers in memoirs and novels. These are all books I’ve read and loved. Which probably tells you everything you need to know about me.

1. We Need To Talk About Kevin by Lionel Shriver

“Eva never really wanted to be a mother—and certainly not the mother of a boy who ends up murdering seven of his fellow high school students, a cafeteria worker, and a much-adored teacher who tried to befriend him, all two days before his sixteenth birthday. Now, two years later, it is time for her to come to terms with marriage, career, family, parenthood, and Kevin’s horrific rampage, in a series of startlingly direct correspondences with her estranged husband, Franklin. Uneasy with the sacrifices and social demotion of motherhood from the start, Eva fears that her alarming dislike for her own son may be responsible for driving him so nihilistically off the rails.”

2. A Map of The World by Jane Hamilton

“The Goodwins, Howard, Alice, and their little girls, Emma and Claire, live on a dairy farm in Wisconsin. Although suspiciously regarded by their neighbors as “that hippie couple” because of their well-educated, urban background, Howard and Alice believe they have found a source of emotional strength in the farm, he tending the barn while Alice works as a nurse in the local elementary school. But their peaceful life is shattered one day when a neighbor’s two-year-old daughter drowns in the Goodwins’ pond while under Alice’s care. Tormented by the accident, Alice descends even further into darkness when she is accused of sexually abusing of a student at the elementary school. Soon, Alice is arrested, incarcerated, and as good as convicted in the eyes of a suspicious community. As a child, Alice designed her own map of the world to find her bearings. Now, as an adult, she must find her way again, through a maze of lies, doubt and ill will. “

3. Terms of Endearment by Larry McMurty

“Aurora is the kind of woman who makes the whole world orbit around her, including a string of devoted suitors. Widowed and overprotective of her daughter, Aurora adapts at her own pace until life sends two enormous challenges her way: Emma’s hasty marriage and subsequent battle with cancer. Terms of Endearment is the Oscar-winning story of a memorable mother and her feisty daughter and their struggle to find the courage and humor to live through life’s hazards — and to love each other as never before.”

4. Tender at the Bone by Ruth Reichl

“Tender at the Bone, is the story of a life determined, enhanced, and defined in equal measure by a passion for food, unforgettable people, and the love of tales well told. Beginning with Reichl’s mother, the notorious food-poisoner known as the Queen of Mold, Reichl introduces us to the fascinating characters who shaped her world and her tastes, from the gourmand Monsieur du Croix, who served Reichl her first soufflé, to those at her politically correct table in Berkeley who championed the organic food revolution in the 1970s. Spiced with Reichl’s infectious humor and sprinkled with her favorite recipes, Tender at the Bone is a witty and compelling chronicle of a culinary sensualist’s coming-of-age.”

5. The Glass Castle by Jeannette Walls

“Jeannette Walls grew up with parents whose ideals and stubborn nonconformity were both their curse and their salvation. Rex and Rose Mary Walls had four children. In the beginning, they lived like nomads, moving among Southwest desert towns, camping in the mountains. Rex was a charismatic, brilliant man who, when sober, captured his children’s imagination, teaching them physics, geology, and above all, how to embrace life fearlessly. Rose Mary, who painted and wrote and couldn’t stand the responsibility of providing for her family, called herself an “excitement addict.” Cooking a meal that would be consumed in fifteen minutes had no appeal when she could make a painting that might last forever.”

April 25, 2013

Writing (and reading) Sex Scenes: Good, Bad, & Ugly

I tried to think of a, um, sexier title for this post, but they all sounded, um, icky, and the last thing I want when I’m writing about sex is an ick factor. Writing about icky sex: terrific. Writing icky about sex: terrible.

I’ve been thinking about this ever since Pia Lindstrom, an interviewer from Sirius Radio, shocked me out of my I-can-handle-any-question mood when she asked something to the effect of:

So, I was surprised by how much sex is in your book. You did it so well. People say it’s hard to write about sex. How did you do it?

Um. Um. Um. Now there was a question I hadn’t been asked before. Sex is included in my work. (Ask my mother-in-law. When she read one of my earlier works—an in-the-drawer-book—she told my husband that I wrote ‘sex novels.’)

Wait! Before you run to the bookstore in hopes of getting a fun sex novel, save your money. Buy something by Jackie Collins. The sex I wanted to convey in The Murderer’s Daughters was the gritty emotional side of the bedroom; the stuff we hate to admit is true.

I had to answer Pia (and fast.) How did I write about sex?

By praying no one would ask me about it.

By telling myself that my husband knows I am not writing about him (except for the good parts, of course.)

By realizing that writing about sex isn’t about insert Tab A into Slot B—it’s about the emotion behind the writhing.

By remembering what Elizabeth Benedict said in her wonderful book, The Joy of Writing Sex:

Benedict: A good sex scene is not always about good sex, but it is always an example of good writing.

It’s easier to write about sex when it’s ‘bad,’ when the character is damaging herself through the act, or using sex as panacea or cover-up, than it is to write about good sex. Perhaps it’s a variation on Tolstoy’s famous aphorism about happy families vs. unhappy families. All fantastic sex is remarkably similar in how it lights up the brain, while “I gotta get through this somehow” sex is a textured way to reveal the problems in a relationship, which leads to Benedict’s next point:

Benedict: A good sex scene should always connect to the larger concerns of the work.

When writing about my main characters, sisters Lulu and Merry, I wanted to show them reacting in wildly divergent ways to the same trauma (the murder of their mother by their father.) Naturally, their experiences of sexuality were defined by that horrendous act. If I wanted to reveal the ways they were affected by witnessing their mother’s death, I needed to go into their bedrooms, and not in a polite manner.

Benedict: The needs, impulses and histories of your characters should drive a sex scene.

Most readers can tell when in a sex scene, the writer has stepped away from the character and inserted a boilerplate moment. It’s easy to understand why a writer might avoid writing deeply about sex. Nobody’s comfortable with the idea that readers who know them might think they are reading a page from the writer’s life.

Which means, if you want to be true to your reader, you have two choices. 1) Take the readers off your shoulder and be willing to go all the way (sorry about that—couldn’t resist) in revealing the good, the bad, and the ugly, or, 2) Skip the sex and use the f a d e – o u t.

Benedict: The relationship your characters have to one another—whether they are adulters or strangers on a train—should exert more influence on how you write about their sexual encounters than should any anatomical detail.

Can I just say how much I hate clinical words in novels? I want writers to capture the inner monologue so well that there is only a very small space between character and reader. Thus, for me, the clinical terms leap out from a page as though the writer is shouting. It becomes a ‘look at me’ moment, rather than a ‘be in the character’ moment. Unless, of course, the character is a sex-ed teacher.

What goes on in a character’s mind as Tab A meets Slot B? Are they actually describing their partner’s body? In The House on Fortune Street by Margot Livesey, the following passage of a couple embarking on their first sexual encounter reveals the emotional and physical relationship of this particular couple without a single clinical detail:

From then on it was all haste and confusion. He undid a few buttons on her blouse and left her to manage the rest while he wrestled with his own clothes. She undressed quickly, eager to be hidden between the sheets. Edward, clumsy with his underwear, took a few seconds longer. Then he was beside her, the whole shocking length of him, and they were clinging to each other. It seemed to Dara that they were struggling to surmount some huge barrier—the barrier between not being and being lovers—and they must do whatever necessary to get over it.

From this passage, the reader immediately knows that Dara is not chasing an orgasm and that she is bringing to this encounter a truckload of emotional baggage.

This is what I want from sex scenes—secret glimpses into the soul, which are possible only at our most vulnerable moments: when we break apart and when we come together—and sex is often a time when those moments collapse into one.

One of the most difficult sex scenes I wrote in The Murderer’s Daughters was one where Merry, one of my two main characters, finally realized that her married lover is one more punishing mistake in her life, a scene which ended with these words:

“Quinn wrenched from me a sad orgasm born of friction and time, and then he came.”

Writing great sex is sort of like having great sex, I suppose—losing yourself in the truth of the moment, sometimes awful moments. Except when you’re writing, you get to go back and edit it until the moments are just exactly what you want.

April 19, 2013

“I can be changed by what

happens to me, but I re...

“I can be changed by what

happens to me, but I refuse to

be reduced by it.”

Maya Angelou

Picture courtesy ox http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...

April 15, 2013

Are Writers Pushing Too Hard?

When I was a reader, I spoke as a reader, I understood as a reader.

When I became a writer, I read as a writer, I understood as a writer.

I just finished “Readers Don’t Owe Authors S**t” on the online site Book Riot. The credo of the post is basically this: writers and independent bookstores shouldn’t nag readers (into shopping Indie, posting reviews, asking for shout-outs, etc.). Much of it resonated in me. I’ve been asked to spread the word many times—and though most of the time I’m happy to help, I don’t like to feel I’ll be ostracized for non-compliance.

When my first novel debuted, it was pretty late in my game. (I was 57.) Though an addicted reader, the only “insider” information and terms I knew, came from novels such as The Bestseller by Olivia Goldsmith. (The first time anyone used the term “the list” I didn’t have a clue that’s how the cool kids referenced the New York Times Bestseller list.) I published my first novel just around the time social media exploded (at least in my awareness,) so I’ve never experienced books or authors online, except as an author/reader—but being a reader is my identity.

As a small child, I went to the library daily. (The only books we had was a Reader’s Digest Condensed Digest, an oversized photo book about Africa with a scratchy grey cover, and a copy of Ideal Marriage by Van de Velde, hidden in my mother’s nightstand.)

Eventually, I built up a small shelf of books—spending my babysitting dollars on the YA of my time, by Beverly Cleary (Fifteen! The Sister of the Bride!), I read and re-read every book I owned. When I traded Brooklyn NY for Berkeley California, books took up as much room in my backpack as my teensy mini dresses. When I became a mother, I managed my book-a-day habit by using the library, so I could buy books for my daughters.

Books have always been the platform on which my sanity rested. Reading was a quiet private pursuit, consisting of reviews, bookstores, library shelves, and trading books and titles with friends.

Authors were akin to gods.

Is it different now? I go back to the sudden onslaught of articles such as “Readers Don’t Owe Writers S**T.” (The article references other essays.) It’s an article I agree with in many facts, if not tone. The author writes, in bold, I don’t owe you your dream career, explaining:

“I want very much for my favourite writers to write books, and I often make the choice to support that by purchasing their books. Sometimes in more than one form. Sometimes in multiple copies as gifts. But I don’t owe my favourite writers those things. Likewise, when I read a wonderful book, I tell lots and lots of people about it. But I don’t owe that to the wonderful books I’ve loved. These are choices I make freely because I love stories and books. And when I make these choices, it is about my relationship with the person I am sharing my love of the book with. It is about neither author nor bookshop, at the core.”

The author goes on to say, “When an author I follow on social media tells me I am not doing enough to sell his or her books for him or her on social media, I stop following that author.”

I understand. Completely. Who wanted to be scolded? It’s not a readers’ job to sell our books. I’ve winced seeing writers online doing everything from groveling to begging to screeching for readers to buy them, “like” their pages, write Amazon reviews. I’ve winced at myself, even as I pretend that when I do it I somehow sound cute and not pathetic.

But, though books have a life outside of the writer, they are still our books. Readers do not need to do a blessed thing after closing the last page, that is true—but at their core, these are our books. They exist only for the multiplicity of hours we spent writing them.

Stephanie Cowell, author of five novels and a winner of an American Book Award, wrote this when I asked her opinion on the topic: “I do think that kind of pushy behavior (described in the article) is beyond the pale … no one should be pushed like that. But I think if we like an author’s work or the author is living and not making a Dan Brown fortune, it is the right thing to buy the book, not borrow it. We contribute to all sorts of things, most of us. We don’t borrow a meal in a restaurant. Of course, if we can’t afford it, then we can do second-hand or borrow by all means…but again, the author has no right to say anything. It just creates bad feelings. I remember when a friend with a lot of money sent me two remaindered books to autograph… I bit my tongue hard.”

Here’s the thing–we’re caught between the proverbial Scylla and Charybdis. Just as actors love acting, dancers love dancing, and comedians love cracking jokes, writers love writing. But though some of all of the above are doing it for a joy of craft alone, a great deal of us are doing it for a living and suddenly, in this new online world, this translated into promoting anything and everything we can. (Cute puppies! Funny kids! Adorable elderly parents saying the sweetest things!)

God save the writer with neither cuteness nor tragedy to promote, because we’re all fighting for attention. There are more books than ever. Bowker reports that over three million books were published in the U.S. in 2010 (May 18, 2011 Bowker Report). The number of new print titles issued by U.S. publishers has grown from 215,777 in 2002 to 316,480 in 2010. And in 2010 more than 2.7 million “non-traditional” titles were also published, including self-published books, reprints of public domain works, and other print-on-demand books.

Cable television somewhat democratized the medium, but it also brought a din of competition—the same is going on with publishing. There are fewer mainstream reviews and a greater number of consumer reviews. There is tremendous pressure to be online, get the word out, do book clubs in person, by Skype, by train, plane & automobile. Write posts. Do events. Go to festivals. Participate on panels. Form support groups. Shout out other writers. None of the above is breaking rocks, but for mid-list writers there is no money in it either. It’s done for free, or, more likely, it’s done for free and paid for by the writers. When you see those “book tours!!” you can bet that 90% of them are author-funded.

After our books are published, most writers spend months online and in person, trying to convince readers—without turning them off—that our books are worth their time and money. (Or just their time—libraries are book buyers of the highest order. Writers love having readers request our books. )

All this après-writing work requires learning the close-to-impossible: how to do it graciously and well. One (well, me) can spend hours and hours studying how to do it properly, how to find the right tone and voice, and one can still blow it. Ah, that rock and hard place: on the one hand, squirming at posting another “Me! Me! Me!” and on the other hand, studying your Bookscan numbers and Amazon ranking as though examining the Dead Sea Scrolls. How tempting, how easy, to simply post one more me-me-me about one’s book.

MJ Rose, owner of Authorbuzz—a book marketing firm—and a bestselling author (her next book, Seduction, releases May 7) says,

“Authors live in a time when what we’re asked to do, what we think we need to do, and what our publishers often expect us to do, make us look unseemly. Authors online act in ways they’d never allow themselves in person. It’s rare when I meet an author in person who acts the way they do online. One rule I use is this: before I say anything online, I ask myself is this something I’d share with someone I just met at a cocktail party? If the answer is no, then I don’t post it.”

Author Catherine McKenzie (her latest book is Forgotten) is acutely aware of this issue: “I think every writer these days has that me-me-me feeling whenever their book comes out (and in the months leading up to it and after it). I remember when my first book came out a couple of years ago in January, 2010. I dubbed it the “month of me” and was thoroughly sick of myself by the end of it. One thing I find helps is I turn that me-me-me spotlight onto other authors. It’s so much easier to say “read this!” or “buy this!” when I’m getting nothing out of it other than turning other people onto good books”. (You can see Catherine’s current such project here.)

Relentless recounting of successes by authors (the extreme-don’t-try-this-at-home version of Me! Me! Me!) can also drive other writers insane. Internationally praised historical fiction writer C.W. Gortner, (his most recent book is The Queen’s Vow: A Novel of Isabella of Castile) is the friend I need when the torture becomes too much. As we went back and forth about a recent online debacle, he said:

“Watching that was like a mash-up of Wonder Woman and Shameless. I’m going to Prada to bask in things I cannot afford and escape the Me-Me Circus. It’s getting to the point that Facebook qualifies as an instrument of torture.”

That’s okay. In some ways. I am doing my dream job. And I don’t expect anyone owes me a thing (except not stealing my book. No piracy please. I never did it to a musician: I’m glad my karma is clear.)And then, with in between all that booty-shaking, uber-gracious tweeting, and traveling, you have to write. Most authors will say writing their first book, in the quiet of non-selling, was the most comfortable. I know for me, because of the whole corporate problem my publisher is caught in (ongoing negotiations with Barnes and Noble, which has resulted in almost no Simon & Schuster books being carried at the only major chain bookstore in the United States) my promotion time has extended beyond the normal month or two. I’ll be traveling, online and on Amtrak, from February through June, visiting independent bookstores, book clubs, and participating in events. The result is that I’m fighting for a quiet space to write. And the result of that is working seven days a week since my book came out in February.

So, are writers being unseemly? Perhaps some of us are, sometimes. Some appear me-me-me all the time. Laura Harrington, winner of the 2012 Massachusetts Book Award for fiction, says, “I like to think of Katherine Hepburn. She understood stardom and she also understood privacy.

Her desire for privacy actually enhanced her mystery and her allure. She will always be considered a “class act.” I think there’s something nearly desperate about some of what’s going on – and that is never attractive.”

I agree with Laura. And yet, I study my numbers. I worry, I watch, and like most authors I vacillate between my desire to be Katherine Hepburn and my pull towards jumping up and down like a contestant on Let’s Make A Deal.

So, when I cringe at another’s (or my own) urges towards me-me-me, I try to remember to allocate a bit of kindness towards writers (like me) trying to dance as fast as we can.