Phil Simon's Blog, page 61

August 10, 2015

Demystifying the Data Scientist

Odds are that you’ve heard the increasingly trendy business term data scientist. To be sure, there’s no shortage of myths around them, but I have yet to meet very many people who can answer in plain English, “Just what does a data scientist do, actually?”

It’s a question that, to answer properly, requires more questions.

Do they even exist or are they unicorns? What does one look like, anyway?

Yes. Here you go.

x

What sub-fields does data science consist of?

Data science is a bouillabaisse of a number of other related quantitative and technical disciplines. These include: math, dataviz, statistics, data engineering, pattern recognition and learning, advanced computing, uncertainty modeling, data warehousing, and high-performance computing (HPC).

Data science is a bouillabaisse of a number of other related quantitative and technical disciplines. These include: math, dataviz, statistics, data engineering, pattern recognition and learning, advanced computing, uncertainty modeling, data warehousing, and high-performance computing (HPC).

Is supply keeping up with demand?

In short, no. This is why they command large salaries.

While the numbers vary, there’s general consensus that we need more of them—many more. The vaunted management firm McKinsey believes that “The United States alone faces a shortage of 140,000 to 190,000 people with analytical expertise…to understand and make decisions based on the analysis of Big Data.”

Is there any overlap between the modern data scientist and a business analyst?

Yes, but there are real differences. This is not simply a matter of nomenclature. That is, these are not one and the same. As I wrote in Too Big to Ignore:

By tapping into these varied disciplines, data scientists are able to extract meaning from data in innovative ways. Not only can they answer the questions that currently vex organizations, they can find better ones to ask.

This might seem a bit abstract, so let’s make it more concrete.

A traditional data or business analyst typically examines data from a single source. Perhaps this is a CRM or ERP application. By way of contrast, a data scientist will go deeper. S/he will explore and examine data from sources often external to the enterprise. These may include social data, linked data, and open data. (For more on the latter, see my interview with Joel Gurin on his excellent book Open Data Now.)

What about the tools?

Data science is a bouillabaisse of a number of other related quantitative and technical disciplines.

It’s the difference between checkers and chess. A business analyst will almost always use Microsoft Excel or Access. Data scientists will use far more powerful and predictive tools like R.

Does a data scientist need to know Bayes’ theorem?

Is strong business acumen required?

Absolutely. It’s a moral imperative.

x

What other non-technical skills are essential?

The best data scientists excel at critical thinking. The job entails—in fact, requires—a high degree of human judgment. This goes double when selecting and defining the problem. It’s downright false to claim that data scientists are slaves to computers, automation, and data. As IBM puts it, “they will pick the right problems that have the most value to the organization.” Excellent communications and presentation skills are also sine qua nons. Being able to determine “the answer” means nothing if you can’t explain it effectively to upper management and laypersons.

Feedback

What say you?

This post was brought to you by IBM for MSPs and opinions are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s PivotPoint. Dedicated to providing valuable insight from industry thought leaders, PivotPoint offers expertise to help you develop, differentiate, and scale your business.

This post was brought to you by IBM for MSPs and opinions are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s PivotPoint. Dedicated to providing valuable insight from industry thought leaders, PivotPoint offers expertise to help you develop, differentiate, and scale your business.

The post Demystifying the Data Scientist appeared first on Phil Simon.

August 4, 2015

Proof that You Don’t Need Rely Upon E-Mail

I love stories like these.

VentureBeat recently ran a great piece about Mejor Trato, a neat Mexican company that has junked e-mail, meetings, and managers. To say that the results are striking would be a vast understatement: Permanent four-day weeks.

Let that sink in for a moment.

Is Mejor Trato Unique?

Well, yes and no. I haven’t heard of many organizations that have adopted three-day weekends, never mind 86’d the notion of a manager. (With regard to the latter, Zappos is one of the few.)

On the other hand, MT is hardly the only company to realize the insanity of “collaborating” over a technology rooted in the paper corporate memo. Via three full-length case studies, I endeavored in Message Not Received to introduce actual companies that have embrace new, truly collaborative tools. I like to think that I succeeded, but make no mistake: Plenty of other organizations not profiled in the book get it—and more are coming on board every day.

Nothing is stopping you from slaying the e-mail dragon.

You may be thinking that eradicating e-mail would never work in your organization. Maybe you’re right. But what about significantly reducing its internal use? Not possible? Nonsense.

Simon Says

A point from the book bears repeating here: We love to blame technology (in this case, e-mail) because it can’t blame us back. Nothing is stopping you, your group, your department, your division, and/or your organization from experimenting with different alternatives. You’re only a Google search and a few clicks away.

Feedback

What say you?

The post Proof that You Don’t Need Rely Upon E-Mail appeared first on Phil Simon.

August 3, 2015

Not All APIs Are Created Equal

Perhaps the single most overused buzzword in contemporary business is platform. Try to find a company today that doesn’t brand itself as a platform of some sort. It borders on comical. Why label a yourself a ride-sharing service? Platform is so much sexier. Just ask Lyft (as told by Google):

Just because I wear a funny hat, though, doesn’t make me the Pope.

Walking the Talk

At a high level, true platforms incorporate two types of developer building blocks: APIs and SDKs. (This is a key point in The Age of the Platform.) A company that doesn’t use either, if not both, is just paying lip service to the notion of platform thinking. Think marketing more than reality. Put differently, APIs and SDKs are necessary but not sufficient conditions for building a successful platform. Without them, a company simply cannot attract increasingly critical developers. With APIs and SDKs, nothing is guaranteed. Just ask Microsoft and BlackBerry, two companies resigned to irrelevance in the smartphone wars.

True platforms incorporate two types of building blocks: APIs and SDKs.

But it is downright silly to think of an API as a binary. It’s not. Rather, there are many different types of APIs. (For more on this, see Proprietary APIs: A New Tool in the Age of the Platform.) The sooner that organizations and their leaders understand this, the quicker they’ll be able to reap the ample rewards that platforms can confer.

A Cutter Consortium report manifests the different types of—and general uses for—APIs:

TypeDescription

FreeAPI provided for free; usually done to attract consumers or promote APIs.

Developer PaysDeveloper has to pay for the API or its usage.

Pay as You GoCommon model for cloud-based APIs: developer pays only for parts of API currently being used; typically allows easy scaling up or down upon developer's needs.

FreemiumBasic version of API provided for free; developers can switch any time to a premium version that doesn't have limitations but must be paid for.

Unit-BasedDevelopers must pay based on number of API calls made; calls are typically grouped into units (e.g., by call type) and billed as such (e.g., per 1000 API calls).

TieredAmount developers must pay depends on price tier; tier determined by predefined factor (e.g., total number of calls per month, amount of provider resources required).

Transaction FeeAPI provider takes cut from every transaction done through API.

Developer Gets PaidDeveloper gets paid by the API provider).

Rev-ShareProvider shares percentage of revenue earned through use of API (e.g., revenue from advertising).

AffiliateProvider pays developers based on specific agreement. Usually, this model is used with advertising (i.e., CPA [cost per action/acquisition], CPC [cost per click], or CPM [cost per mile]) or customer referral. Latter can beone time" (e.g., paid for every new customer signup) or recurring (e.g., paid every month as long as referred customer stays subscribed).

IndirectCovers models with indirect methods of payment or revenue.

Content AcquisitionAPIs used to gather valuable data (for the provider's business) from users —e.g., advertisements, posts, listings, feedback, opinions.

SaaSAPIs that go together with/or are part of SaaS business model; can be included into a base SaaS offering or used as an additional benefit in an upsell.

Content SyndicationMaking content (e.g., news, articles) available to be published by other parties with the goal of getting wider exposure.

Internal UseAPIs aimed at internal use; can be consumer-facing (public Web, mobile/devices) or internal facing (SOA+, Web/mobile).

The table above begs the question: What does this all mean for third parties? Many things, but here’s one chilling thought.

Let’s say that you envision your app seamlessly retrieving data from external sources. Wouldn’t it be cool to plug into a powerful, popular, and data-rich API like Netflix’s? Sounds great, but you may be out of luck. Netflix effectively shut down its public API more than a year ago. That may very well scuttle your plans from the get-go. And make no mistake, Netflix is hardly alone here. Twitter and LinkedIn have also earned the ire of many developers by severely restricting or eliminating access to their APIs.

Simon Says: Do your homework.

APIs can do amazing things. It’s no understatement to say that their explosion has created tens of billions of dollars of revenue. Hollywood is even jealous. Thinking of all APIs willy-nilly, though, is a recipe for disaster. Do your homework before spending a great deal of time and money on your “platform.”

Feedback

What say you?

This post was brought to you by IBM for MSPs and opinions are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s PivotPoint. Dedicated to providing valuable insight from industry thought leaders, PivotPoint offers expertise to help you develop, differentiate, and scale your business.

This post was brought to you by IBM for MSPs and opinions are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s PivotPoint. Dedicated to providing valuable insight from industry thought leaders, PivotPoint offers expertise to help you develop, differentiate, and scale your business.

The post Not All APIs Are Created Equal appeared first on Phil Simon.

July 30, 2015

Advice to Startups: Stop Using the Word ‘Platform.’ Please.

To be sure, the word platform has become de rigueur in the business lexicon. I’m actually surprised when I hear startup founders describe their companies and not use the term.

While fashionable, for a long time now being a “platform” has ceased to become a differentiator. In fact, it often invites more indifference and confusion than real understanding—precisely the opposite effect that founders desire.

For instance, at a recent conference I attended, I met a woman and our conversation went like this:

Me: Hi. I’m Phil. Nice to meet you. What do you do?

Woman: I started [Company X]. We are a gift-experience platform.

Me: What does that mean?

I’d hazard to guess that no one wants to hear those four words after explaining his or her company, job, book, movie, etc.

Was this an isolated event? Nope. Later that evening, another person confused me for five minutes with a convoluted description of her company. Something about apps, platforms, and the elderly. I wasn’t really sure.

Solution

Simplicity and questions are beautiful things.

The founder of the “gift-experience platform” and I wound up having a nice conversation. She was receptive to my honest feedback. I suggested that she should try to ask questions upon meeting people, not drop ostensibly sophisticated terms like platform. Conversations would then go like this:

Person: Hi. I’m [insert name]. Nice to meet you. What do you do?

Woman: Have you ever wanted to give a friend a cool experience such as having dinner with his favorite rock star or athlete?

Person: Yes, I have.

Woman: That’s what [Company X] does.

Person: Cool. Tell me more.

Simon Says

Fight the urge to use jargon. Simplicity and questions are beautiful things, especially when you’re trying to get people to, you know, understand you.

Feedback

What say you?

Cross-posted on Medium.

The post Advice to Startups: Stop Using the Word ‘Platform.’ Please. appeared first on Phil Simon.

Advice to Startups: Stop Using the Word ‘Platform’

To be sure, the word platform has become de rigueur in the business lexicon. I’m actually surprised when I hear startup founders describe their companies and not use the term.

While fashionable, for a long time now being a “platform” has ceased to become a differentiator. In fact, it often invites more indifference and confusion than real understanding—precisely the opposite effect that founders desire.

For instance, at a recent conference I attended, I met a woman and our conversation went like this:

Me: Hi. I’m Phil. Nice to meet you. What do you do?

Woman: I started [Company X]. We are a gift-experience platform.

Me: What does that mean?

I’d hazard to guess that no one wants to hear those four words after explaining his or her company, job, book, movie, etc.

Was this an isolated event? Nope. Later that evening, another person confused me for five minutes with a convoluted description of her company. Something about apps, platforms, and the elderly. I wasn’t really sure.

Solution

Simplicity and questions are beautiful things.

The founder of the “gift-experience platform” and I wound up having a nice conversation. She was receptive to my honest feedback. I suggested that she should try to ask questions upon meeting people, not drop ostensibly sophisticated terms like platform. Conversations would then go like this:

Person: Hi. I’m [insert name]. Nice to meet you. What do you do?

Woman: Have you ever wanted to give a friend a cool experience such as having dinner with his favorite rock star or athlete?

Person: Yes, I have.

Woman: That’s what [Company X] does.

Person: Cool. Tell me more.

Simon Says

Fight the urge to use jargon. Simplicity and questions are beautiful things, especially when you’re trying to get people to, you know, understand you.

Feedback

What say you?

Cross-posted on Medium.

The post Advice to Startups: Stop Using the Word ‘Platform’ appeared first on Phil Simon.

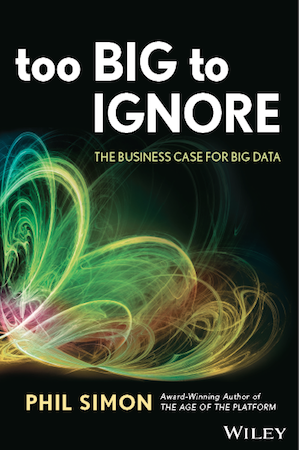

Paperback Version of Too Big to Ignore Is Coming

Around two-and-a-half years ago, Wiley published my fifth book Too Big to Ignore.

Around two-and-a-half years ago, Wiley published my fifth book Too Big to Ignore.

No, it did not take the literary world by storm. No Pulitzer. Still, the book has done reasonably well. I learned a while back that a Chinese version was in the works (好消息), and that has become a reality. And now there’s more good news.

I just learned that Wiley is will publishing a paperback version of the book with a target release date of October. It’s my first book to go from hardcover to paperback.

Golf applause.

The post Paperback Version of Too Big to Ignore Is Coming appeared first on Phil Simon.

July 22, 2015

The Vicious Cycle of Conference Mediocrity

Think about the last five proper conferences that you attended. (Forget Meetups.)

I’ll wait.

How many of them were actually worth your time and the expense? (Forget for a moment if your company footed the bill.)

Again, I’ll wait.

How many of those conferences really wowed you?

I’d be willing to bet that that number is two or fewer.

I’ll also wager that the largest problem with these conferences wasn’t the venue. I doubt that your biggest gripe was the quality of the food or the beverages. You probably weren’t happy with the Wifi, but that alone is unlikely to completely sour the event for you. Ditto if you didn’t get enough time to network.

Nope, in my experience, the fundamental problem with conferences typically lies with the people on stage. Bad speakers make for bad conferences.

Here’s an important corollary: Great and even really good speakers almost always negate the effects of lousy accoutrements.

To wit, nobody has ever said the following:

“I learned a great deal from the conference speakers but wouldn’t return because the coffee was lousy.”

“Although the speakers bored the hell out of me, I can’t wait to come back. The coffee and lunch were amazing!”

Asking the Big Question

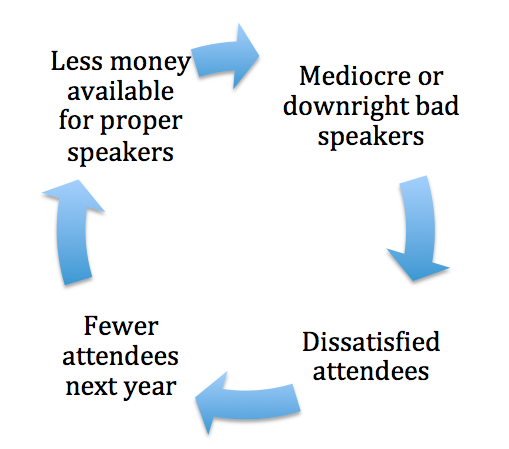

If you believe—as I do—that quality speakers are part and parcel to a satisfying conference, then riddle me this: Why are so many people on stage so mediocre? Put differently, why do conference organizers routinely place so little emphasis on the most important aspect of their events?

While the specifics vary among conferences, the answer usually isn’t rocket surgery: Many conferences lack the funds to hire proper (read: professional) speakers. Many organizers attempt to lure dynamic professional speakers with the vague promise of “exposure”, expenses covered, and the opportunity to sell books from the back of the room. Few if any established orators will go for this, though. With anything in life, though, you get what you pay for.

Unable to catch the big or even medium fish, conference organizers often resort to Plan B. They try to fill their speaking and panel slots with a combination of the following:

Calls for talks (read: speakers are chosen via some formal vetting process)

Volunteers

Employees from sponsors

Speakers are no exception. As with anything in life, you get what you pay for.

Is this understandable on several levels? Of course. From the standpoint of the conference organizer, the speaking slots are filled. (Check that box.) What’s more, some amateur speakers are actually quite good, but make no mistake: the average professional public speaker trumps the average amateur any day of the week and twice on Sunday. It’s not even close.

The unwillingness of many conference organizers to bring in true professionals results in the following vicious cycle:

Let’s say that you’re thinking about attending an upcoming conference. Consider the following two options:

Option A: $1,000 for a truly valuable two- or three-day conference staffed by informative and provocative speakers.

Option B: $600 for a mediocre conference with a few decent speakers—and a bunch of terrible ones.

Option C: Go to neither.

Which one appeals to you more? I’d bet that you or your manager would pay 67 percent more for Option B. Why waste the time and money on Option A? In fact, I’d rank them as follows: A, C, B.

In case you’re wondering what a bad speaker looks like, see below.

The horrible slide and willingness to turn his back on the audience are telltale signs.

Simon Says: How to Break the Cycle

Look, few conferences can break the bank and bring in rock stars like Malcolm Gladwell (rumored to get $80,000 per speech). Economics is about scarcity and choices. Think about this next time you’re planning a conference.

Make attendees buy their own booze. Charge a little bit more. Find another way of making the numbers work without skimping on speaker expenses. It’s a near surefire way to leave attendees wanting.

Feedback

What say you?

The post The Vicious Cycle of Conference Mediocrity appeared first on Phil Simon.

July 14, 2015

People Operations: Three Hard Truths

Google is nothing if not a trendsetter. Thanks to Google, today many companies let key employees employees experiment with skunkworks projects (read: the since-retired 20-percent rule). No, Larry and Sergey didn’t invent A/B testing, but few organizations have popularized it to the extent that Google has. Ditto for employee surveys—and really doing something with the results.

It seems that we’ll be soon able to add people operations to that list. Today, many companies appear to be dancing to Google’s tune. This is not to say, however, that People Operations has supplanted the traditional HR function in very many organizations. It hasn’t. It’s obvious that it’s starting to gain traction in many HR circles.

This begs the question: Does your organization need to get on the People Operations train?

A simple rebranding exercise is unlikely to really make a difference.

I’ll be the first to concede that HR has a long—and justifiably—been viewed as the red-headed stepchild in most organizations. The paradox is profound: Almost without exception, CEOs talk about people being their greatest assets, yet the majority of HR departments barely maintain anything beyond the most basic employee data, such as name, address, title, hire date, rate of pay, benefits, and the like. And don’t get me started on the accuracy of that information.

Three Hard Truths about People Ops

Where does this leave us with respect to People Ops? Here goes.

First, the temptation to adopt a trendy name is easy to understand. (We’ve been hearing that HR needs to become a strategic partner for more than two decades now.) In and of itself, though, a simple rebranding exercise won’t make a lick of difference.

Second, just because People Ops worked at Google doesn’t mean that it will work at your organization. Unless and until your employees routinely make data-based decisions, the monikers of their departments are irrelevant. Actually doing something with data is infinitely more important than a department’s name. A Personnel department that embraces quantitative thinking is exponentially more valuable than a People Ops department that doesn’t.

Third, an organization need not form a People Ops department to be successful. What’s more, an organization won’t necessarily be successful just because it has created one. In a way, this is analogous to the presence of a Chief Data Officer.

Simon Says

Make no mistake: the opportunity around people analytics is huge, but there is a chasm between reality and possibility. Beyond tradition, most Finance, Marketing, R&D, and Sales departments maintain relatively high levels of credibility for one reason: they use data to make (more) intelligent decisions, minimize risk, and predict.

Why should HR, Personnel, People Ops, or [insert new stylish name] be any different?

Feedback

What say you?

The post People Operations: Three Hard Truths appeared first on Phil Simon.

July 10, 2015

Recent Posts

It would be an interesting exercise to calculate precisely how many words I have published over the last six years. Rough estimate: it has to be approaching two million. I derived that number by adding up the books, entries on this site (now more than 1,000), and posts for clients. With respect to the latter, here are some of my most recent contributions:

Defining DevOps: 6 key attributes everyone should understand

DevOps: The importance of clear communication

Top 4 obstacles to effective agile methods within DevOps

DevOps: 4 benefits of using agile methods

What Zappos’ bold moves teach us about data governance

Is effective data governance possible in an era of Big Data?

The three-group theory of change management

Three Things that Driverless Cars Teach Us about the Future

The post Recent Posts appeared first on Phil Simon.

July 7, 2015

The Data Wars Revisited

Nearly eight years ago, Josh McHugh in a great Wired piece asked the question, Should Web Giants Let Startups Use the Information They Have About You? The article examines the pros and cons of allowing small companies to scrape data.

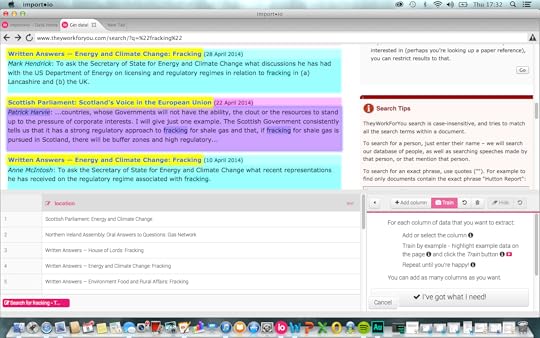

In the nearly eight years since the publication of that piece, scraping data remains a controversial practice. To be sure, there’s significant demand for tools that pull data from websites and return it in usable formats. Startups such as Grepsr, Krakio, promptcloud, and import.io allow technical and, in many cases, non-technical users to grab data en masse from websites and create customized application program interfaces (APIs). Put differently, these go well beyond old-school copying and pasting. (Read my interview with import.io CEO David White here.)

import.io screen shot. Click to embiggen.

Across the aisle, many companies view scraping “their” data as a tremendous threat. For instance, the practice represents on way to get yourself banned from Facebook. Zuck understandably doesn’t want people gobbling up reams of Facebook data, without question one of his company’s most valuable assets.

The Larger Trend

As companies grow, they start to restrict access to their APIs.

I’m not going to argue the merits and demerits of scraping here. I do, however, want to call attention to the larger trend going on here. The data wars are not confined to popular sites such as Facebook and Google. The battle for data is becoming increasingly bloody. What’s more, it’s manifesting itself in decidedly unsexy areas such as HR software. (See my post earlier this month on the Zenefits-ADP scuffle.)

Build a custom or proprietary API. No longer is the sole purview of tech behemoths.

Build a data moat, something that Netflix, Amazon, and Facebook have effectively done.

Close or limit access to its API. Many have done this, including Twitter and LinkedIn. Yes, developers can violate the terms of an API and get slapped for doing so.

Simon Says: The data wars have arrived.

To be sure, there are pros and cons with all strategies. For instance, option three might “protect” data, but it’s going to earn the ire of developers and users. Wooing developers and partners by opening “platforms” and APIs is standard practice at the beginning. As companies grow, however, they start to restrict access to their APIs.

In The Age of the Platform, there are no simple answers.

Feedback

What say you?

This post was brought to you by IBM for MSPs. The opinions in this post are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s PivotPoint. Dedicated to providing valuable insight from industry thought leaders, PivotPoint offers expertise to help you develop, differentiate, and scale your business.

This post was brought to you by IBM for MSPs. The opinions in this post are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s PivotPoint. Dedicated to providing valuable insight from industry thought leaders, PivotPoint offers expertise to help you develop, differentiate, and scale your business.

The post The Data Wars Revisited appeared first on Phil Simon.