Phil Simon's Blog, page 60

September 9, 2015

Why Jargon Has Prevailed

By trade, Frederick Winslow Taylor was an American mechanical engineer, but he’s not renowned for that. Long before the Bobs in Office Space, Taylor was arguably the world’s first efficiency expert. In the late nineteenth century, he spent a great deal of time watching factory workers performing manual tasks. Taylor wasn’t bored, nor was he a voyeur. He was working, recording everything he saw with his stopwatch. He was on a quest to find the one best way to do each job. That information would further his ultimate goal: to improve—in fact, to maximize—economic efficiency, especially labor productivity. This became the basis for his theory of scientific management.

Taylor passed away in 1915, but his significance in the business world has persevered. For example, in The Management Myth: Debunking Modern Business Philosophy, Matthew Stewart describes Taylor’s posthumous impact:

The management idol continues to exert its most direct effect on business education. Although Taylor and his doctrine fell from favor at the business schools as his name became associated with public controversy, his fundamental idea that business management is an applied science remained cemented in the foundations of business school. In 1959, for example, the highly influential Gordon and Howell report on the state of business education called for a reinvigoration of the scientific foundations of business educations.

Over the years, many critics have attacked Taylor’s theory. Today you’re unlikely to meet one of his acolytes, but Taylor remains an influential if controversial figure a century after his death. Perhaps Taylorism’s crowning achievement was that it represented the earliest known attempt to apply science to the field of management. Even now this is an open debate: Is management a true science?

It’s a contentious issue with enormous stakes. Corporations pay handsomely for elite management consulting firms such as Bain Capital, McKinsey, Accenture, and the Boston Consulting Group. Ditto for gurus such as Tom Peters, Jim Collins, and Guy Kawasaki. For his part, Collins can command as much as $100,000 for a daylong seminar, not including first-class accommodations. Even junior McKinsey consultants bill upward of $300 per hour.

CEOs pay these exorbitant sums for two reasons. First, hiring a prominent consultancy or guru is widely viewed as safe. Many CEOs continue to abide by the maxim “Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM.” Second, experts promise to fix what ails their clients. For this type of coin, management experts are supposed to provide organizations with valuable advice that is guaranteed to work. Can you imagine a team of very pricey consultants concluding a six-month assignment with the words “We’re pretty sure that [our recommendations] might work?”

Except they often don’t, and here’s where the “management is a science” argument crumbles. If management really were a true science, then it stands to reason that it would always follow immutable laws. For instance, consider chemistry. Water always freezes at 0°C and boils at 100°C at 1 atmosphere. Period. There are never any exceptions.

Where is the management analog?

Keep thinking.

Give up?

It doesn’t exist.

Put differently, management is doubtless a critical discipline, but referring to it as a science is erroneous. Think of it more as a philosophy or, at best, a social science—and there’s nothing wrong with that. Unfortunately, a great deal of modern management theory and its practitioners continue to suffer from a scientific inferiority complex. In Stewart’s words:

As with Taylor’s purported general science of efficiency, most efforts to concoct a general science of organizations fail not because the universal principles they put forward are wrong—they are usually right—but because they don’t belong to an applied science. They properly belong to a philosophy.

Many other books touch on the central theme that even expert predictions are nothing more than coin flips:

The Halo Effect: . . . and the Eight Other Business Delusions That Deceive Managers by Phil Rosenzweig

The Witch Doctors: Making Sense of the Management Gurus by John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge

Everything Is Obvious: How Common Sense Fails Us by Duncan J. Watts

The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Forget trying to predict, manipulate, and manage social and economic systems. Attempting to do this on even an individual level is bound to go awry. For myriad reasons, the same strategy that worked for Company A at one point may fail abysmally when Company B implements it. Diversifying offerings can save one company and ravage another, even if they are in the same industry.

These types of vicissitudes are not very scientific. Even if a team of the world’s best management consultants told you that your company ought to “stick to its knitting,” adhering to that advice guarantees zilch. This is even truer now than it was 20 years ago. Against this backdrop of rampant technological change, far too many external factors are at play to ensure anything remotely resembling certainty. A trite bromide and 10-point plan will not by themselves yield the desired results. Business is not a laboratory; one cannot hold all other factors constant to pinpoint cause and effect.

This brings us to the liberal use of buzzwords by gurus, management consultants, and MBAs. I challenge you to think of three groups of people who have wrought more jargon on the business community. Scientists create and use sophisticated terms to explain new and complex phenomena. It logically follows, then, that management types will do this as well. In an effort to appear smart and scientific, they have coined phrases like thinking outside the box, paradigm shift, optics, and scores more. They have perverted more than their fair share of simple words as well.

Many buzzwords or pithy axioms from management consultants can be explained just as well—in fact, usually better—in simple English. From the consultants’ perspective, though, simplicity and clarity pose a significant problem: It makes them appear less smart, less scientific. Maybe they wouldn’t be able to charge as much if their advice seemed so obvious.

This post was excerpted from Message Not Received: Why Business Communication Is Broken and How to Fix It and published on HuffingtonPost.

The post Why Jargon Has Prevailed appeared first on Phil Simon.

September 8, 2015

On Success, Clarity, and Simplicity

There’s no shortage of “as-a-service” terms infecting permeating the tech and business landscapes these days. Troll around the web or a social-media site for a few minutes and you’ll find a gaggle of terms both established/understood and wholly contrived. I’d put SaaS in the former category and confusing neologisms such as BDaaS and MBaaS in the latter.

It’s completely out of hand. I’m just waiting for the birth of “service as a service.”

Oh, wait. It already exists.

In the past, I’ve been very critical of the increasing prevalence of tech jargon and term inflation both on my site and on others. I felt so strongly about the subject that I penned a book about it. Message Not Received argues for the simplest possible language in the business world.

What’s the harm?

You might be thinking, What’s the harm of using a few buzzwords to define projects? Is business jargon really as pernicious as you suggest?

Put simply, buzzwords inhibit effective business communication.

Put simply, buzzwords inhibit effective business communication. Bad communication costs organizations a great deal of time and money, never mind squandered opportunities and lost market share from increasingly nimble competitors.

But don’t take my word for it. Consider the 2013 Pulse of the Profession™ In-Depth Report: The Essential Role of Communications by the Project Management Institute (PMI). From it:

Poor or substandard communications accounts for more than half of the money at risk on any given project. [C]ompanies risk $135 million for every $1 billion spent on a project. The new research indicates that $75 million of that $135 million (56 percent) is put at risk by ineffective communications, indicating a critical need for organizations to address communications deficiencies at the enterprise level. Respondents also reported that ineffective communications is the primary contributor to project failure one third of the time, and had a negative impact on project success more than half the time.

To be sure, excessive jargon represents only one cause of poor business communications. Relying too much upon e-mail and language/cultural differences are also major culprits. Be that as it may, though, I fail to see how deploying any new technology can be successful if stakeholders (re: employees, vendors, developers, and partners) are not on the same page. I’d wager that the organizations that embrace clarity and simplicity are far more successful than their unclear counterparts.

Simon Says: Your organization is unlikely to be successful without clarity and simplicity.

Partners and clients cannot successfully deploy new technologies while confused about what they are doing, how they are doing it, and their ultimate objectives. When describing new ideas, products, services, and concepts, use whatever terms you like as long as they are commonly understood.

Feedback

What say you?

This post was brought to you by IBM for MSPs and opinions are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s PivotPoint. Dedicated to providing valuable insight from industry thought leaders, PivotPoint offers expertise to help you develop, differentiate, and scale your business.

This post was brought to you by IBM for MSPs and opinions are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s PivotPoint. Dedicated to providing valuable insight from industry thought leaders, PivotPoint offers expertise to help you develop, differentiate, and scale your business.

The post On Success, Clarity, and Simplicity appeared first on Phil Simon.

September 2, 2015

Why We Work by Barry Schwartz

The recent New York Times‘ story on employment at Amazon evoked a slew of visceral reactions, even one from Jeff Bezos himself. It turns out that everyone holds strong opinions about work. In hindsight, though, the Times‘ story and subsequent brouhaha was more about what we do at work—not why we do it. One could argue that the latter question is even more important than the first. Against this backdrop, Why We Work (affiliate link) by Barry Schwartz arrives at a propitious time.

(affiliate link) by Barry Schwartz arrives at a propitious time.

Full disclosure: The publisher sent me a copy without further obligation.

Invoking plenty of Adam Smith, Karl Marx, John Maynard Keynes, and even a bit of Bruce Springsteen, Schwartz’s inspiring manifesto forces us to question the very nature of modern-day work. Why is it generally so dismal? Is it designed because we are “money hungry” or is the causal chain reversed?

Invoking plenty of Adam Smith, Karl Marx, John Maynard Keynes, and even a bit of Bruce Springsteen, Schwartz’s inspiring manifesto forces us to question the very nature of modern-day work. Why is it generally so dismal? Is it designed because we are “money hungry” or is the causal chain reversed?

Via fascinating anecdote and plenty of data, the book forcefully claims that how we work isn’t working—at least not to the extent to which it should. Schwartz cites some interesting examples of employees who go way beyond their job descriptions for nothing other than the desire to help. In fact, as many studies have proven, offering money significantly changes our feelings about social mores (PDF).

Simon Says

Brass tacks: We need to get more out of our jobs than a paycheck. We need meaning. We need purpose. Maybe Abraham Maslow was right after all?

People looking for “the five ways to get started” will find themselves disappointed. This is a big-idea book, not a not a how-to or tactical text.

I only wish that it was longer, but TED books are deliberately short.

Feedback

What say you?

Cross-posted on Huffington Post.

The post Why We Work by Barry Schwartz appeared first on Phil Simon.

September 1, 2015

Why Data Generation Will Become More Passive

An admittedly tech-challenged friend of mine asked me recently, “What is the Internet of Things?”

As someone who prides himself on heeding Einsten’s words, I love queries such as these. People in tech should be able to explain to an eight-year-old what they do. Her question was very much on my mind as I penned this post.

A Ridiculously Brief History of User-Generated Data and the Web

Let’s go back in time for a moment to the dawn of the World Wide Web. Depending on your age, you might not even remember an era with fax machines, land lines, and inter-office memos. Yes, we once did live in a world sans web pages, e-mail, and apps. Trust me. It really did exist. I was there.

There’s much more to it, but it’s fair to characterize the first two decades of the Web as follows. Web 1.0 allowed the masses to consume content at an unprecedented scale and rate, but only relatively tech-savvy folks could produce it.

Around 2005 or so, the first incarnation of the Web started to give way to what we now call Web 2.0. For the first time, laypersons (read: non-techies) were able to easily generate their own content en masse. As I wrote in Too Big to Ignore, for the most part, “you [didn’t] need to be a programmer to generate content, but you [needed] to be a person.”

Put differently, Web 2.0 made data generation far more accessible than its antecedent. You only needed to actively upload a YouTube video, write a blog post, or share a photo. (Let’s forget fairly recent arrivals such as bots, social-media schedulers such as HootSuite and Buffer, and cool automation services like IFTTT for a moment.) Today, anyone with a modicum of tech proficiency can set up a Tumblr blog, Facebook page, WordPress site, or Twitter account. (Becoming a Twitter power user, though, takes a bit more time.)

Against this backdrop, the amounts and types of data have exploded. An unprecedented data (re: text, audio, social media, images, and videos) has flooded the Web. This is the largely unstructured nature of what we now call Big Data. The reasons include the rise of mobile devices, the growing prevalence of broadband, social media, generational factors, new business models that encourage cord-cutting, binge watching, vastly lower data-storage prices, Moore’s Law, and plenty of others.

How the IoT Will Embiggen Big Data

This begs the question: How does the Internet of Things (IoT) change things? In short, think passive, not active.

Make no mistake: The IoT represents a sea change.

Over the past few years, the IoT has received an insane amount of buzz. Trace it roots, though, and you’ll find that Kevin Ashton of MIT coined it way back in 1999. In short, the term represents an increasing array of machines that connect to the Internet—and its consequences are profound. Nearly ten years after introducing it, Ashton reflected on where we are going:

We need to empower computers with their own means of gathering information, so they can see, hear and smell the world for themselves, in all its random glory. Radio-frequency identification (RFID) and sensor technology enable computers to observe, identify and understand the world—without the limitations of human-entered data.

If we had computers that knew everything there was to know about things—using data they gathered without any help from us—we would be able to track and count everything, and greatly reduce waste, loss, and cost. We would know when things needed replacing, repairing, or recalling, and whether they were fresh or past their best.

And this is exactly what is happening.

x

Simon Says

Think of the Internet of Things not as more tech jargon, but as an development with profound implications—and not all of them good. It represents a sea change in who will be generating most data—or, more precisely, what will be generating most data. Machines will passively and automatically create more data than human beings currently do. Partners will help progressive organizations make sense of all of this data.

Put differently, it will only make Big Data, well, bigger.

Feedback

What say you? Where do we go now?

This post was brought to you by IBM for MSPs and opinions are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s PivotPoint. Dedicated to providing valuable insight from industry thought leaders, PivotPoint offers expertise to help you develop, differentiate, and scale your business.

This post was brought to you by IBM for MSPs and opinions are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s PivotPoint. Dedicated to providing valuable insight from industry thought leaders, PivotPoint offers expertise to help you develop, differentiate, and scale your business.

The post Why Data Generation Will Become More Passive appeared first on Phil Simon.

August 31, 2015

The Foolishness of Relying on Social-Media Numbers

Some people equate the number of followers on different social networks with importance and influence. (Hell, they call it Klout for a reason, right?)

And this is often a mistake.

In a very real sense, the Internet has changed nothing. People will always try to game the system, whether that’s with Twitter followers, Spotify listens, or Facebook likes. Churchill’s quote above on democracy is equally apropos to capitalism. It simultaneously represents both the best and worst that we can do. The fleas come with the dog.

As I’ll explain below, relying on these numbers is often both foolish and even destructive.

A Little Yarn

I know a guy who bills himself as an “influencer”, a term that I despise. (It implies that influence is a binary, not a continuum. Everyone has some degree of influence.)

x

Let’s call him Terry here, a nod to Ocean’s Eleven. Terry’s bona fides look good on a superficial level. He sports more than 50,000 Twitter followers and a Klout score north of 70. Primarily because of this, a Fortune 50 company a while back paid him to attend a major event. It was easy money: Terry only had sit on a panel and blog and tweet a few musings about the conference.

Did things go according to plan? Of course not.

It turns out that Terry likes drama and caused quite the ruckus. He got into it with a few others on the panel and then took his rant to Twitter, packing an extraordinary amount of vitriol into 140 or fewer characters. He expressed his displeasure at being a “puppet” for tech companies and, stuffing salt in the wound, made sure to include the event’s hashtag.

Did I mention that he was paid to attend this event?

The point of this little yarn is that social-media numbers often tell at best an incomplete story. More Twitter followers doesn’t mean a hill of beans.

A Better Social-Media Strategy

For my part, I prefer that a relatively small but growing number of sentient human beings follow me, not a mix of people, bots, and spam accounts. To this end, I recently audited my account. Here’s what I found:

View post on imgur.com

Not bad. Ninety-five percent of my followers are real. In the past, I have used tools like ManageFlitter to purge undesirable accounts from my official numbers.

Simon Says

For my money, quality trumps quantity every time. Period. Poseurs are usually exposed eventually.

Feedback

What say you?

The post The Foolishness of Relying on Social-Media Numbers appeared first on Phil Simon.

August 28, 2015

#NoEmail Vodcast with Luis Suarez

“No e-mail” pioneer Luis Suarez recently interviewed me about Message Not Received on his his regular Google hangout. Luis is a bit of a legend in business circles. The former IBM employee has been e-mail-free for a very long time, and the two of us talked about how to communicate better at work.

“No e-mail” pioneer Luis Suarez recently interviewed me about Message Not Received on his his regular Google hangout. Luis is a bit of a legend in business circles. The former IBM employee has been e-mail-free for a very long time, and the two of us talked about how to communicate better at work.

x

The post #NoEmail Vodcast with Luis Suarez appeared first on Phil Simon.

August 25, 2015

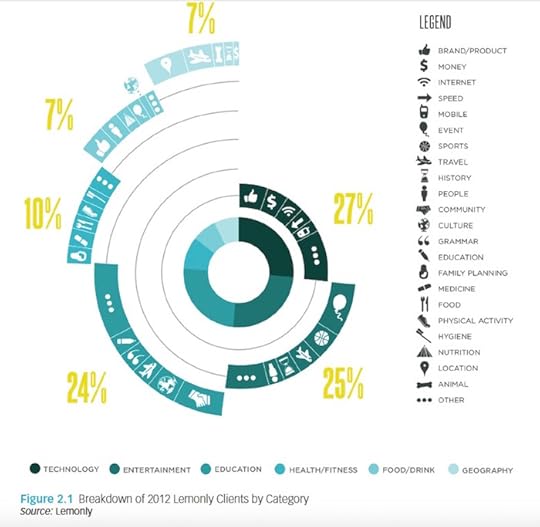

On Visualizing Data and Laziness

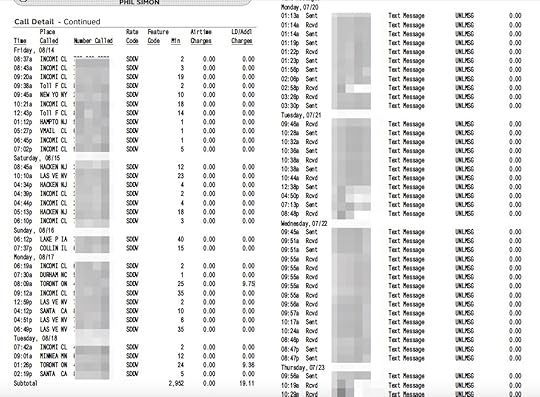

It’s been a while since I’ve blogged about data visualization. My focus for the past year or so has been business communication and Message Not Received. Today, though, my AT&T bill got my dataviz juices going and inspired this rant.

By way of background, I already pay AT&T in excess of $120/month, about one-third of which subsidizes my new iPhone. It’s not a small expense, but it’s a certainly necessary one for someone without a land line. In any event, my bill this month inexplicably exceeded $140 and I wanted to understand why.

Data Detective

Don’t make your customers play detective.

The first page of the bill showed $19.11 in international charges. Fair enough, but I wanted to know which calls contributed to the overage. Lamentably, AT&T made that nearly impossible to discern. (Perhaps this is no accident, but that’s an entirely different question.)

Weeding through the monstrosity of a 14-page PDF that AT&T calls a monthly bill, I finally identified the two recent calls to journalists in Canada about the recent New York Times’ story on Amazon. The charges didn’t make any sense to me, as my current plan had covered calls make to—and received from—North America. Or so I thought.

Click to embiggen.

Any color coding or conditional formatting on these charges? Nope. Easy sorting by price? Not in a PDF.

I called AT&T to straighten things out and, to make a long story short, all is well.

x

Simon Says

Presenting information need not be beautiful in ways like this:

Still, there’s just no excuse today for making customers hunt and peck to find relevant information.

For more on this, see How Not to Visualize Data.

Feedback

What say you?

The post On Visualizing Data and Laziness appeared first on Phil Simon.

August 17, 2015

Four of the Biggest Mistakes that Non-Fiction Writers Make

Long before I could call myself a professional writer, I read quite a bit.

Many times, I had no choice over what I was supposed to read. This included hundreds of texts in high school, college, and grad school. In my consulting days, required reading included:

Confusing corporate policies

Long requirements documents

How-to books on software programs I needed to learn

Manuals on courses that I ultimately taught

Long story short: If I encountered bad writing, there wasn’t much that I could really do about it. I had to slog through.

That’s no longer the case.

These days, other than some legal forms, speaking contracts, and official corporate correspondence, very little of my reading today qualifies as mandatory. In fact, I can’t remember the last time that anyone assigned me anything. I’d bet that you’re in the same boat.

Merely shouting down all naysayers is both puerile and ultimately futile.

That’s not to say, though, that I don’t receive plenty of unsolicited reading recommendations. I get tons of those. For whatever reason, most of my “leisure” reading over the past decade has tended to fall into the non-fiction bucket, and I like to think that I know a thing or six about effective communication and, in particular, non-fiction writing.

Against this backdrop, here are four of my biggest pet peeves from non-fiction authors:

Failing to properly cite their sources. This one is maddening. How hard is it to search the Web for a proper statistic, study, authority, or article supporting your claim? Is it really too much to include a simple footnote or hyperlink? The days of microfiche and card catalogs are long gone. Writers who make broad claims without a scintilla of proof are just lazy and irresponsible.

Substituting interview transcription with proper writing. I know several authors who erroneously believe that most writing consists of transcribing others’ words. Hogwash. If you’re asking people to buy one of your books and take the time to read it, you owe those people more than that. Analyze. Synthesize. Offer an original thought or thirty. Don’t just copy and paste entire interviews and pass it off as proper writing.

Omitting appropriate disclaimers. If you’ve done work with a company, then say so, dammit. Ditto for sponsorships or other sweetheart arrangements. Company X makes the best wares? That might be the case, but is its marketing department paying you to write as much? Not disclosing important relationships is unethical. Period.

Immediately becoming defensive when reading honest criticism of their work. One-star Amazon reviews can sting, and rare is the author of a popular or best-selling book who hasn’t received one. Some critical reviews come from trolls, but others are very insightful and accurate. Yet, many times I’ll see a one-star review and the first comment is from the author defending him/herself. For two reasons, I’m not a fan of responding to these reviews. Don’t feed the Troll, as they say. Second, in many instances, a slew of negative reviews might actually help you improve your writing skills. Merely shouting down all naysayers (irrespective of merit) is both puerile and ultimately futile.

Feedback

What say you?

The post Four of the Biggest Mistakes that Non-Fiction Writers Make appeared first on Phil Simon.

August 13, 2015

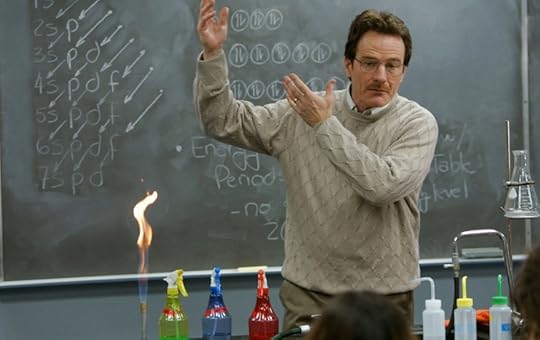

Now Open: Office Hours

For more than 20 years now, I have been educating people in a wide variety of capacities. I started in academic settings. I tutored students after college and then worked as a teaching assistant (TA) in grad school. On a professional level, I taught classes on sexual harassment in my HR days and moved on to classes on enterprise software applications. In hindsight, teaching served as excellent training for public speaking.

Let the learning begin.

Fundamentally, I enjoy learning new things, sharing my knowledge with others, and solving problems. There’s a part of me that misses teaching. I’ve looked in to becoming adjunct professor a few times over the years and it’s something that I’d really like to do under the right circumstances. In an era of MOOCs and online learning “platforms” such as Udemy and Coursera, though, it’s folly to think that learning only occurs in a classroom today. On the contrary, there have never been more ways to acquire knowledge and put it to use.

To this end, I will start holding office hours: free, 30-minute, zero-obligation sessions in which you can pick my brain about whatever topic you like. I envision the sessions as two-way conversations/dialogues, not stodgy lectures/monologues.

I’m going to test this for three months. If it’s successful, then I’ll continue it.

I put together a little FAQ that explains the particulars.

Let the learning begin.

The post Now Open: Office Hours appeared first on Phil Simon.

August 11, 2015

Thoughts on the New Google

Even ten years ago, only a middling or sinking organization would consider adopting a fundamentally new management structure. The notion that one of the most successful companies on the planet by any standard would shake things up so dramatically was anathema.

Bold moves are not only advisable today, they’re often necessary.

Well, this isn’t 2005.

In case you needed any more proof, consider Google’s Alphabet announcement yesterday. Google as we know it still exists, albeit with new management. A new holding company will own Google and other properties.

Was such a dramatic move necessary for Google to survive? Of course not. The company is churning out near-record profits and dominates search and mobile devices. (Don’t call them monopolies, though.)

x

Simon Says: Bold is good.

In The Age of the Platform, complacency is a surefire way to ensure irrelevance or even obsolescence. Just ask Blockbuster, AOL, Yahoo!, RIM, and scores more. Bold moves such as massive acquisitions, management shakeups, and new product launches are not just optional today, they’re often wise and even necessary.

More than ever, success today is no guarantee of success tomorrow.

Feedback

What say you?

The post Thoughts on the New Google appeared first on Phil Simon.