Oxford University Press's Blog, page 303

November 8, 2017

National Family Caregivers (NFC) Month: a reading list

National Family Caregivers (NFC) Month is celebrated each November, in honor and recognition of the roughly 40 million Americans providing care to an adult family member or loved one. In 1997 President William J. Clinton signed the first NFC Month Presidential Proclamation, articulating that “Selflessly offering their energy and love to those in need, family caregivers have earned our heartfelt gratitude and profound respect.” Since that time, every President has continued this tradition, issuing annual proclamations recognizing and honoring family caregivers each November.

This commemorative month is a time to celebrate the contributions of family caregivers, raise awareness of the challenges they face, increase public support for this vast and often invisible workforce, and educate family caregivers about the resources available to them. Caregiving takes a toll on one’s physical, emotional, and financial well-being – especially for the more than three million caregivers ages 75 and older, who may need assistance themselves. At the same time, most caregivers report immeasurable benefits, including a feeling of purpose, a renewed closeness with their loved one, and the chance to “give back” to the parent, spouse, grandparent, or sibling who has been their confidante and protector. In celebration of National Family Caregivers Month, we have created a reading list of recent articles from Gerontological Society of America journals that reveal new scientific insights into the lives of family caregivers.

“Multiple Chronic Conditions in Spousal Caregivers of Older Adults with Functional Disability: Associations with Caregiving Difficulties and Gains” by Polenick et al. (2017)

Many family caregivers are older adults themselves, and must manage their own health chronic health conditions while also assisting their ailing spouse or partner. This study uses data from 359 spousal caregiver-care recipient dyads from the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) and National Study of Caregiving (NSOC) to examine similarities and differences in how caregivers and their spouses manage multiple chronic conditions (MCCs). Couples that are mismatched in how they manage their MCCs have poorer health outcomes, and may benefit from support in maintaining their own health as well as their caregiving responsibilities.

“Activity Engagement among Older Adult Spousal Caregivers” by Queen et al. (2017)

Staying engaged and involved in the activities one enjoys may be an important source of caregiver well-being. This study used four waves of data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to examine the ways that spousal caregivers’ well-being is affected by changes in their participation in physical, social, self-care, passive, and novel information processing activities. Caregiving is linked with declines in one’s participation in physical activities, which may ultimately undermine one’s overall well-being.

Elderly by sarcifilippo. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Elderly by sarcifilippo. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.“Health Benefits Associated With Three Helping Behaviors: Evidence for Incident Cardiovascular Disease” by Burr et al. (2017)

Do caregiving and other types of helping behaviors affect specific disease outcomes? This study uses ten years of data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to explore the impact on cardiovascular disease (CVD) of three helping behaviors: formal volunteering, informal helping, and caregiving for a parent or spouse. Although caregiving was not linked to CVD risk, volunteering and providing informal help were linked with reduced risk of heart disease. Helping may enhance one’s health, especially if these prosocial behaviors are not particularly stressful or physical strenuous.

“Explaining the Gender Gap in the Caregiving Burden of Partner Caregivers” by Swinkels, Joukje, et al. (2017)

Men and women experience caregiving differently, and thus may experience different health consequences. Using data from the Netherlands’ Older Persons and Informal Caregivers Survey—Minimum Data Set, this study examined gender differences in the burdens facing spouse/partner caregivers and the health consequences of these burdens. Women report more caregiving burden, because they experience more secondary stressors like relationship and financial difficulties, although men’s feelings of burden are linked to the intensity of care required. Reducing care hours may be protective to men whereas social support may benefit women caregivers.

“Routine Support to Parents and Stressors in Everyday Domains: Associations with Negative Affect and Cortisol” by Savla et al. (2017)

Caregiving often involves daily or “routine” support to aging parents and loved ones. This study uses daily diary data from the National Study of Daily Experiences (NSDE) to explore whether providing routine support to parents is linked with higher negative affect and salivary cortisol – a marker of stress exposure and risk factor for disease. The results show that providing routine support to parents is linked with both negative health outcomes, although these effects were not amplified on days when children experienced stress at work. This study confirms that caregiving is a stressful experience, regardless of the other co-occurring strains one is experiencing.

“The Association between Informal Caregiving and Exit from Employment among Older Workers: Prospective Findings from the UK Household Longitudinal Study” by Carr et al. (2016)

The demands of caregiving may hasten exits from paid employment, especially for older workers. This study uses data from five waves of the Understanding Society study in the United Kingdom and explores associations between informal caregiving and exits from paid employment. In general, full-time employees who were also caregivers were more likely to stop working, compared to those not providing care, with particularly pronounced patterns among women. Employers could help extend older employees’ working lives by recognizing and supporting their caregiving demands at home.

“Modeling Cortisol Daily Rhythms of Family Caregivers of Individuals with Dementia: Daily Stressors and Adult Day Services Use” by Liu et al. (2016)

The demands placed on dementia caregivers are particularly daunting. This study uses data from the Daily Stress and Health (DASH) study to examine whether and how caregivers’ use of adult day services (ADS) affected their daily cortisol levels – an indicator of physiological responses to chronic stress. The study examined the typical diurnal cortisol trajectory and its differential associations with an intervention, the adult day services (ADS) use, among a sample of family caregivers who experienced high levels of daily stress. ADS use was associated with healthier cortisol profiles, suggesting the biophysiological benefits of daily ADS use for older caregivers under chronic stress and high levels of daily stress.

Featured Image credit: “A Flame from the Ashes” by Josh Appel. CC0 public domain via Unsplash.

The post National Family Caregivers (NFC) Month: a reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

The end of liberalism

Fifty-nine years ago, William Proxmire of the now-Rust Belt state of Wisconsin took the floor of the US Senate in support of a bill that would lower tariffs on imported goods. My then-boss had brought with him a few hundred of the many pro-free-trade letters that our office had received in support of the bill.

Every single letter was written by a member of the United Auto Workers. At the time, manufacturing workers supported the liberal agenda of expanded world trade.

But that was then. I’d be willing to bet that many who wrote those letters urging Proxmire to support freer trade, and their children, voted for Donald Trump in droves, helping him to carry Wisconsin, the first Republican presidential win there in a generation.

Liberalism — and not just a reduction in trade barriers — is now in trouble. Initially a set of values that advanced individual rights and tolerance as a hallmark of a well-governed society, liberalism came to embrace a laissez-faire economic model that today places these values in jeopardy. In the process, liberalism has lost sight of the ends that once animated it. Xenophobic intolerance is a symptom, not a cause, of liberalism having lost its bearings, and of its lack of a convincing narrative of what went wrong.

Those ends include protecting religious minorities and defending the weak against the strong. William Pitt, a member of the British parliament, in 1763 explained the political meaning of private property: “The poorest man may in his cottage bid defiance to all the forces of the Crown. It may be frail – its roof may shake – the wind may enter – the rain may enter – but the king of England cannot enter – all his force dares not cross the threshold of the ruined tenement.”

John Maynard Keynes in 1926 explained how the fateful marriage of political and economic liberalism came about: “At the end of the 17th century the divine right of monarchs gave place to natural liberty . . . and the divine right of the church to the principle of toleration . . . the effect — through the new ethical significance attributed to contract – was to buttress property.”

Liberalism’s perfect storm was thus of its own making.

The response to growing inequality in property – “socialism and democratic egalitarianism,” according to Keynes — was contained as a result of “a miraculous union” delivered by “economists, who spring to prominence just at the right moment [with] the idea of a divine harmony between private exchange and the public good.” And so, in the 19th century, liberalism took on board laissez-faire. Its effect would be to empower the rich against the poor and the market against community.

It was partly in response to the ongoing increase in disparities of wealth that in the first half of the 20th century, liberalism was embraced as a modern conception of democracy. Under pressure from democratic socialist parties and the threat of communist revolution, economic and political elites conceded to the democratization of liberalism: Universal suffrage joined toleration, private property, and competitive markets as a liberal hallmark of good governance.

The figure below records this progress.

Figure 1. The advance of democracy in the world, from The Economy by The CORE Project. Green portions of the bar are periods of both inclusive voting rights, civil liberties and fair elections. Light green portions refer to periods in which a significant ethnic minority was de facto or de jure disenfranchised.

Figure 1. The advance of democracy in the world, from The Economy by The CORE Project. Green portions of the bar are periods of both inclusive voting rights, civil liberties and fair elections. Light green portions refer to periods in which a significant ethnic minority was de facto or de jure disenfranchised.Initially a set of values that advanced individual rights and tolerance as a hallmark of a well-governed society, liberalism came to embrace a laissez-faire economic model that today places these values in jeopardy.

This extension of voting rights to women and people without property was followed by an expanded role of governments later in the 20th century. In most liberal societies, disparities in living standards fell and real wages rose, especially in the three-decades-long “golden age” of capitalism, following the end of World War II. But with the end of the golden age in the mid-1970s, things started to go wrong.

In the United States, real wages stopped growing; workers stretched to sustain the living standards of their parents. Others resisted adjusting to unregulated market-driven shocks, refusing to abandon family and neighbors to seek work elsewhere, and watching their communities decay. Especially from the late 1970s onwards, and accelerating after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, parties on both sides of the aisle in many countries adopted policies to deregulate financial, labor, and other markets. Economic disparities exploded.

Into this combustible mix, the success of another liberal project — integrating the global economy, including migrations unprecedented since the late 19th century — sparked a backlash that has gathered force over the past decade: a xenophobic and parochial narrative blaming “others.”

To many, the story made sense of the former welder, now barely managing to get by, and the boarded up windows on Main Street. It is not convincing if facts matter. But in many countries, it has carried the day in the absence of a competing account, one that might have targeted instead those who had profited from the deregulation of markets.

Liberalism’s perfect storm was thus of its own making: Global laissez-faire provided ready-made scapegoats for growing economic disparities and the decline of once proud manufacturing communities that were the correlates of its domestic laissez-faire.

With universal suffrage, the fate of liberal values is now in the hands of a broad electorate, many of whom (or their ancestors) had been vociferous defenders of liberal freedoms in the past. The advance of democracy — including the extension of the vote to those without property — in the 19th and 20th centuries was driven by movements of workers, small farmers, and the urban poor. Today, the active support of the less well-off is again essential to the defense and deepening of liberal freedoms.

The marriage of liberalism to an economic model guaranteed to promote inequality now makes this unlikely. But rejecting “free trade” in favor of protectionism will only promote its parochial mindset.

Endangered liberal values would stand a better chance in a society committed to defending the weak and vulnerable, as did the early liberals, and to insure people against the economic insecurities that inevitably accompany a technologically dynamic and cosmopolitan economy.

A version of this post was originally published on Boston Globe.

Featured image credit: statue of liberty banner header by The Digital Artist. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The end of liberalism appeared first on OUPblog.

The history of Acupuncture [timeline]

With its roots stretching back to over 6,000 years BCE, Acupuncture is one of the world’s oldest medical practices. This practice of inserting fine needles into specific areas of the body to ‘stimulate sensory nerves under the skin and in the muscles of the body’ is used widely on a global scale to alleviate pain caused by a variety of conditions. However, this form of traditional Chinese medicine has had a turbulent history, often being met with cynicism from medical professionals in the East and West, and has even been a banned practice. Our timeline, based on Clinical Acupuncture and Ancient Chinese Medicine, explores the rich history of acupuncture from its beginnings in ancient China to its use in modern medicine.

Featured Imaged Credit: Beschrijving van Japan – naaldensteek pag 459’ by Englebert Kaempfer. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The history of Acupuncture [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

Is there definitive proof of the existence of God?

When Kurt Gödel, one of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century, died in 1978 he left mysterious notes filled with logical symbols. Towards the end of his life a rumour circulated that this enigmatic genius was engaged in a secret project that was not directly relevant to his usual mathematical work. According to the rumour, he had tried to develop a logical proof of the existence of God. The notes that Gödel left, which were published a decade after his death, confirmed that the rumour was indeed correct. Gödel had invented a version of the so-called modal ontological argument for God’s existence.

The modal ontological argument purports to establish the astounding thesis that the mere possibility of the existence of God entails its actuality. That is, the argument says, once we agree that God can in principle exist we can’t but accept that God does actually exist. There are many distinct versions of the modal ontological argument but one of the most straightforward can be presented as follows.

According to ‘perfect being theism’, a form of theism most widely accepted among Judaeo-Christian-Islamic theists, God is a being that exists necessarily. Such a being is distinct from contingent beings like tables, cars, planets and people, which exist merely by chance. If God exists at all, there is no possible situation in which he fails to exist. Proponents of perfect being theism also typically say that God is all-powerful, all-knowing, and morally perfect because he is perfect in all respects. This observation suggests that the thesis ‘it is possible that God exists’ is equivalent to ‘it is possible that, necessarily, an all-powerful, all-knowing and morally perfect being exists.’ At this point the modal ontological argument appeals to a principle in modal logic that is widely accepted by logicians: If it is ‘possible’ that something is ‘necessary’, then that thing is simply ‘necessary.’ In other words, if we have the sentence ‘it is possible that something is necessary’ we can drop the phrase ‘it is possible that’ without changing the meaning. If we apply this logical principle to what we have derived so far, namely, the thesis ‘it is possible that, necessarily, an all-powerful, all-knowing and morally perfect being exists’, we can derive the thesis ‘it is necessary that an all-powerful, all-knowing and morally perfect being exists.’ This is equivalent to saying that God exists necessarily. If God exists necessarily, then God actually exists. Hence, the mere possibility of the existence of God logically entails its actuality.

Portrait of Kurt Gödel, one of the most significant logicians of the 20th century, as a student in Vienna by unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Kurt Gödel, one of the most significant logicians of the 20th century, as a student in Vienna by unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Theists’ attempts to demonstrate the possibility of God involve some of the most creative ideas in philosophy. Clement Dore and Alexander Pruss, for example, try to establish the possibility that God exists by appealing to the fact that many people have encountered God in religious experiences. Dore and Pruss do not assume that these religious experiences are veridical – they are willing to accept that some (or even all) of them are hallucinations. However, according to them, if the existence of God is impossible then God cannot even appear in hallucinations. The fact that people encounter God in religious experiences suggests that, even if they are hallucinations, the existence of God is at least possible.

To take another example, Carl Kordig tries to establish the possibility that God exists by appealing to the so-called ‘ought implies can’ principle. If we ought to rescue a drowning child we can rescue that child. Conversely, if we cannot for some reason rescue a drowning child, then it is not the case that we ought to rescue that child. Kordig says that God ought to exist because he is a perfect being. And given that God ought to exist we can infer with the ‘ought implies can’ principle that he can exist as well. Hence, it is possible that God exists.

How does Gödel try to show that God’s existence is possible? He argues that it is possible because God has only positive properties. If God were to have both positive and negative properties simultaneously it would seem impossible for him to exist because they would contradict each other. For example, it would seem impossible for God to exist if he were to have the property of being all knowing (a positive property) and the property of being ignorant (a negative property) simultaneously. Therefore God, as the greatest possible being, has only positive properties, such as the properties of being all knowing, all powerful and morally perfect, which, according to Gödel, do not contradict each other.

Whether the abovementioned arguments for the possibility of God succeed is disputed. Yet the modal ontological argument is important because it seems to reduce the burden of proof on theists dramatically. They no longer need to rely on traditional arguments for the actuality of the existence of God, which appeal to the origin of the universe, the source of morality, the apparent design in nature, testimonies of miracles, and so on. All they need to do is show that the existence of God is at least possible. If we can show that, we can simply plug it into the modal ontological argument and derive, as a matter of logic, that the existence of God is actual. Hence, the modal ontological argument places us only a half-step away from a definitive proof of the existence of God.

Featured image credit: sunlight sunrise sunset dawn by 5hashank. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Is there definitive proof of the existence of God? appeared first on OUPblog.

November 7, 2017

Celtic goddesses to inspire writers [slideshow]

In Greek Mythology, the muses were called upon by artists and musicians to guide and inspire their work. This National Novel Writing Month, we’ve traveled to the Celtic isles to call upon some lesser known goddesses to help inspire different genres and tropes you may wish to put to paper. Referencing Celtic Mythology: Tales of Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes, we’ve pulled together a list of five Celtic goddesses for writers.

Epic Journey: Nehalennia

Gaulish goddess perhaps associated with seafarers.

Seafarers would call on this Gaulish goddess to guide them across the water and so should you before you deep dive into your research on the next great literary adventure.

Image credit: “Nehalennia.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Money: Rosmerta

Gaulish goddess of prosperity.

Whether it’s a roman á clef on the very wealthy, a get rich quick scheme, or the hope that your novel takes off as the next bestseller, you’ll need this goddess of wealth and prosperity on your side.

Image credit: “Rosmerta-Autun” provided by NantonosAedui. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

Feel-Good Story: Anu

Irish mother goddess.

Keeping a story personal and heartfelt is so important and the Irish mother goddess is always ready to listen and lend a helping hand on your writers path.

Image credit: The “Paps of Anu” are named after the Irish goddess Anu. “The western Pap from the eastern Pap” by Colin Park. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Self-Help: Sulis

British goddess of healing.

Whether you write to help others or to calm yourself, make sure to brew a warm tea for the British goddess of healing and all will be well.

Image credit: “Minerva Sulis” by Hchc2009. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

When you can’t decide: Brigid

Triple goddess of fertility, medicine, and poetry.

The original multi-tasker, she was the triple-goddess of fertility, medicine, and poetry. If she can manage to be different inspirations to different people, you have no excuses to not try out something new.

Image credit: “087 Dinéault Statue de divinité Brigitte” by Moreau.henri. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: “analog-binder-blank-book” by Pixabay. CC0 public domain via Pexels.

The post Celtic goddesses to inspire writers [slideshow] appeared first on OUPblog.

Sharia courts in America?

Islamic courts need not be scary so long as they adopt the general framework used for religious arbitration in America. Islamic arbitration tribunals have a place in America (just like any religious arbitration does), but Sharia Courts must function consistent with American attitudes and laws towards religious arbitration tribunals generally. By observing how Jewish rabbinical courts are regulated by U.S. law and function within their religious communities, one sees that Islamic courts could be another example of the kind of religious arbitration that is a well-established feature of the American religious life. The central question is not whether American law will accept Sharia courts, but whether Sharia courts will accept the limitations American law imposes on them.

Since the 1924 Federal Arbitration Act, American law has evolved from offering only one venue and law for dispute resolution to permitting numerous options, including laws of different legal systems to resolve disputes through binding arbitration. In essence, the idea is that people can agree to resolve disputes not only in a court under American law, but also in arbitration and in accordance with any set of rules to which the parties agree. Parties can rely on arbitration because the law allows them to turn to the courts for enforcement of the arbitrators’ decisions.

The virtue of this approach generally is clear: if people want to do business according to French law, or Jewish law, and they sign a contract agreeing to that, the legal system ought to respect their choices. And if they agree that they want disputes resolved by French lawyers they agreed to, or three rabbis they selected, we ought to give people the freedom to resolve disputes as they wish. Arbitration’s essence is contract.

Image credit: Ground Zero Mosque Protesters by David Shankbone. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia.

Image credit: Ground Zero Mosque Protesters by David Shankbone. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia.This model has enabled the development of a thriving Jewish law court system within the United States: indeed, religious Americans resolve disputes with others pursuant to the norms and values of their respective religious traditions in many faiths.

We should expect to witness a rise in religious arbitration. As the common social fabric in America has shifted to a secular model, many religious people no longer see the legal system as reflecting their values. Religious arbitration becomes a way that people can agree to enforce their values. Consider adultery in American divorce law as an example: once illegal, then financially penalized, and now, in most states, legally inconsequential. Religious couples may instead want their marriages governed by the rules of their faith, and sign a prenuptial agreement to this end penalizing adultery. Then, in the event of a divorce, they may prefer religious arbitration, where the person judging shares the values by which they have chosen to live.

The fact that religious arbitration is currently legally permissible does not mean that Islamic arbitration is desirable to secular society. Arbitration sometimes facilitates the underhanded waiver of rights and religious arbitration could allow the enforcement of religious law that our secular society finds repugnant. Parties can use religious law to resolve disputes that foster unequal treatment of women or abuse of children.

How does our legal system prevent this? Three ways:

First, courts only enforce religious arbitration awards when parties have willingly agreed to participate: religious communities may pressure members to keep disputes “in-house,” which needs to be balanced with the rights of religious association in a community. A judge must ensure that the individual’s participation in faith-based arbitration processes is truly voluntary.

Second, religious arbitration must adhere to procedural limitations, such as allowing lawyers to be present, treating all parties and witnesses equally regardless of gender, and ensuring that arbitrators lack bias. When this is not done, arbitration awards should not be enforced.

Third, religious systems must respect the limits imposed by law: in America, that limit is financial awards only and child custody recommendations (subject to review by a judge). While arbitration permits parties to resolve disputes through “Singaporean law” or “Islamic law” if that is what they agree to, American law must still limit the authority of arbitration panels and never permit corporal punishment (even if Singaporean law permits it).

Recognizing these limits is critical for successful religious arbitration. Religious communities that do not accept these limitations will find that their religious arbitration decisions will not be enforced by secular courts. To make this system work, religious arbitration panels need to employ skilled lawyers and professionals who are also members of their home religious community and who can provide expertise in secular law, the faith’s own religious law, and contemporary commercial practices. Dual expertise is crucial.

All of these lessons were learned by rabbinical tribunals over the last half century and have contributed to their success in America. The fears about Sharia Law and Islamic courts could be real, but Islamic tribunals can implement the same protective measures used in rabbinical courts if they wish. Such would prevent the many abuses highlighted by various news articles over the last decades and lead to more legally acceptable Islamic courts.

Islamic adaption to American arbitration law norms would be good for secular and religious America and American Muslims. By permitting religious communities to conduct private faith-based dispute resolution within clear American law limits, there is a chance that religious and secular segments of society and culture will engage in conversation that moderates its extremes. The fanatically religious community would benefit from these conversations, as would virulently secular society. The interactions — between secular courts and religious arbitration panels, and between religious and American laws — hold out the possibility that American society may be able to temper the more extreme tendencies of both Islamic practices and the secular legal system by encouraging religious communities to grow from their interactions with America, while allowing America to learn from the best of many religions.

Featured Image Credit: Sharia Law Billoard by Matt57. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia.

The post Sharia courts in America? appeared first on OUPblog.

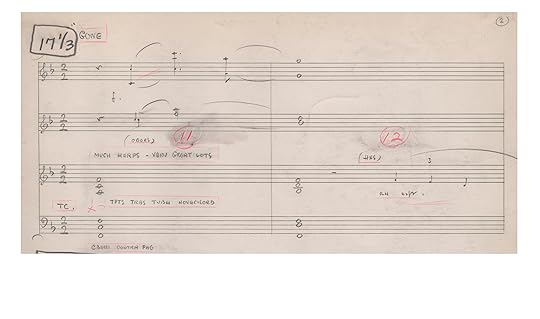

Unanswered questions in Gone with the Wind’s main title

If asked to recall a melody from Gone with the Wind, what might come to mind? For many, it’s the same four notes: a valiant leap followed by a gracious descent. This is the beginning of the Tara theme, named by composer Max Steiner for the plantation home of Scarlett O’Hara, whose impassioned misunderstandings of people and place propel the story.

Less known is that Max Steiner fashioned his Tara theme from another melody that he had unveiled in They Made Me a Criminal, a modest Warner Bros. film released eleven months before David O. Selznick’s production of Gone with the Wind. This melodic forerunner had its own predecessor, with Steiner spinning it from a simpler prototype used in Crime School (1938).

The earlier melodies share several features that were not extended to Tara: namely, walking bass accompaniments, blue notes, and swung rhythms. For Crime School, Steiner even instructed his assisting orchestrator to strive for something “sort of ‘American’” and “hot.” Steiner also wrote the n-word next to “blues,” acknowledging a cultural debt in blatantly racist terms. For They Made Me a Criminal, Steiner counseled his orchestrator to emulate George Gershwin, who mingled jazz and symphonic idioms in Rhapsody in Blue. With the benefit of hindsight, Steiner’s concoction for that film sounds like a blues-sprinkled Tara theme.

Image courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

Image courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.Why did Steiner turn to these melodies when contemplating Tara? The earlier films showed young, inner-city Irish Americans struggling against overwhelming odds to escape poverty and ascend the social ladder. The characters’ ethnicity and “whatever it takes” attitudes correspond to Scarlett’s. But Steiner’s incorporation of sounds associated with jazz and the blues—the expected musical accompaniment for depicting hard, city living in 1930s films—gives these melodies a racial inflection that remains relevant in Gone with the Wind.

To carry the sounds of jazz to the fields of Tara would have been jarringly anachronistic. But it is striking that Steiner’s adaptation wipes away all traces of a racialized and racist past: walking bass lines are replaced with plushly sustained chords in the brass, swung figures are sharpened into square, dotted rhythms, and blue notes are replaced with overzealous harp arpeggios. One annotation in the score even reads “quite some harp.” (Louise Klos, one of the harpists, was Steiner’s wife.) Whether Steiner intended it, the process of drawing on, then marginalizing, African-American culture reflects through music the troublingly majestic portrayal of plantation life that characterizes the film.

Of course, most in the audience would not recognize the Tara theme as adapted from these earlier models. Also lost would have been Steiner’s decision to draw his musical emblem for Tara from melodies born of blues and jazz (or at least Steiner’s impression of them).

Did Steiner, not above writing racist slurs in the privacy of a handwritten score, make this selection to plant a provocative irony? That just as Scarlett’s family depended on enslaved African Americans, so the Tara theme admitted through disavowal its indebtedness to African American culture? At the very least, Steiner felt compelled to qualify Gone with the Wind as a “human document, dealing with white people,” an observation that is obvious yet necessary.

Image courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

Image courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.But the tale does not stop there. Steiner did not write the initial presentation of the Tara theme heard in the film’s main title. He delegated the plum task to Hugo Friedfhofer, an orchestrator who had assisted Steiner on They Made Me a Criminal. With Steiner’s theme in hand, Friedhofer got to work setting what would become one of the most famous passages of music ever to come out of Hollywood. Friedhofer then passed his sketches—signed “Max Steiner & Co.”—to Reginald Bassett, who arranged Friedhofer’s arrangement for full symphony orchestra.

Tellingly, Friedhofer does not begin the main title with the Tara theme. He starts with a fragment of “Dixie” before shifting to a resplendent orchestration of Mammy’s theme. While the decision to open with “Dixie” seems intuitive for the film’s setting, its abrupt exit for Mammy’s music is less straightforward. It opens the door for speculation about music’s capacity to sustain readings that offer counterpoint to a film’s projected worldview. Friedhofer might have picked any number of Civil War-era tunes or character themes to follow “Dixie.” Did he choose Mammy’s to connect with the Tara theme’s backstory? To show that without the labor of enslaved individuals like Mammy there was no Tara? (For her role as Mammy, Hattie McDaniel became the first African American to win an Academy Award, a distinction that was overdue and fraught. Writing for The Chicago Defender, Clarence Muse praised McDaniel’s performance while urging readers to support African-American filmmakers and “fight your way out” of the narrow roles Hollywood offered to African Americans. “If you don’t,” he warned, “all of our artists will become immortal gems of the old South.”)

The questions this music poses are raised quietly. And they may have only been heard—if heard at all—among the musicians who toiled in Hollywood, composing, arranging, and recording one another’s work day after day. But while Gone with the Wind marks an exceptional effort in the history of film, the shared construction of its music points to a common, collaborative dynamic in Hollywood music-making that often developed over multiple productions, like the Tara theme itself. As for music’s capacity to both celebrate and challenge the film it announces, Gone with the Wind stands apart, an appropriate distinction for a film that engenders sympathy for diverse characters while holding a flawed vision of humanity in its heart.

Featured Image: “Hollywood Sign Iconic Mountains Los Angeles” by 12019. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post Unanswered questions in Gone with the Wind’s main title appeared first on OUPblog.

Fake facts and favourite sayings

When the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations was first published in 1941, it all seemed so simple. It was taken for granted that a quotation was a familiar line from a great poet or a famous figure in history, and the source could easily be found in standard literary works or history books. Those early compilers of quotations did not think of fake facts and the internet. “Fake facts”, or perhaps more accurately misunderstandings, have been around in the world of quotations for a long time. Often, when people see a line they like, they simply copy it and repeat it. Take, for instance:

“At the touch of love, everyone becomes a poet”

If (at the time of reading), the words were attributed to the Greek philosopher Plato, this would be repeated too. But in fact it was not Plato who originally said it. Although it is found in his work The Symposium, he was explicitly quoting the playwright Euripides.

Sometimes it is even possible to spot the very point at which such mistakes occur. “The time you enjoy wasting is not wasted time” is often attributed to the mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell, but actually first occurs as an editorial comment by the Canadian writer Laurence J. Peter on Russell’s line “The thing that I should wish to obtain from money would be leisure with security.” Clearly the aside has taken on more life than the original. On the same page Peter adds to Aristotle’s “The end of labour is to gain leisure” with “so that you can drink coffee on your own time”, but somehow no-one has attributed an enthusiasm for coffee to Aristotle!

More often the transition remains unclear. Over twenty years ago we kept coming across a rather long but very apt quotation, always linked to the Roman satirist Petronius:

“We trained hard…but it seemed that every time we were beginning to form up into teams we would be reorganized. I was to learn later in life that we tend to meet any new situation by reorganizing; and a wonderful method it can be for creating the illusion of progress while producing confusion, inefficiency, and demoralization.”

Image Credit: “Head of Platon, roman copy.” The original was exposed in the Academy after the death of the philosoph (348/347 BC) by Bibi Saint-Pol. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: “Head of Platon, roman copy.” The original was exposed in the Academy after the death of the philosoph (348/347 BC) by Bibi Saint-Pol. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Given that only a limited range of writing by Petronius has survived, it was relatively easy to establish that this was not included, so we attributed it to the very prolific author “Anonymous” as a modern saying. A few years ago, the origin was finally traced to a passage in a short story about the war in Burma by Charlton Ogburn Jr., published in the magazine Harpers in 1957. How it became attached to Petronius is a mystery we’d love to solve.

One fruitful source of confusion is film. A favourite quote from the 2001 film The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring is:

“Even the smallest person can change the course of the future”

Spoken by Galadriel, this line does not appear in the book, and the credit should really go to the screenwriters, not the author J.R.R. Tolkien (the idea does occur in a speech elsewhere in the book by another character, Elrond, but the wording is completely different). Likewise, “We read to know that we’re not alone” is almost universally attributed to C. S. Lewis. However this is not something that Lewis himself said, but a line given to his character in the film Shadowlands, and the credit for it should really be given to the screenwriter William Nicholson.

Clearly, misattributions have been arising ever since people started quoting each other, but the existence of the internet has greatly expanded and accelerated the process. In the past, an attribution was only likely to become widespread if it appeared in print, and this limited the possibilities. Today, it only takes one careless tweet or blog, and repetition on a huge scale sets in. For example:

“And when it rains on your parade, look up rather than down”

Is a quotation widely attributed to G. K. Chesterton, but the Oxford English Dictionary has not found the phrase “to rain on a person’s parade” before Bob Merrill wrote the song for the musical Funny Girl in 1964. G. K. Chesterton died in 1936, and there is no sign of this saying before the twenty-first century. It is highly unlikely, not to say impossible, that Chesterton ever wrote this.

But while it propagates errors, the internet is also invaluable in tracing quotations, particularly with the advent of full-text searching. In the early 1990s our researcher looked diligently in the voluminous writings of Thomas Jefferson for the quotation:

“Nothing gives one person so great advantage over another, as to remain always cool and unruffled under all circumstances.”

Turning page after page, he failed to find it, but years later with an online text search it was immediately traced to the right letter. So unsurprisingly, the internet both helps and hinders the seeker after accuracy in quotations. It can be a great resource, so long as we remember with John Dryden:

“Nor is the people’s judgement always true:

The most may err as grossly as the few.”

And perhaps we should give the last word to the novelist Dan Brown:

“’Google’ is not a synonym for ‘research.’”

Featured Image credit: “Jefferson, Thomas (bust)” from the National Archives and Records Administration. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Fake facts and favourite sayings appeared first on OUPblog.

November 6, 2017

The constitutionality of the parsonage allowance

Under Internal Revenue Code Section 107(2), “ministers of the gospel” can exclude from the federal income tax cash payments from their congregations and other religious employers for such ministers’ housing. The IRS and the courts have held that this income tax exclusion applies to clergy of all religions including rabbis, cantors, and imams. Income tax-free housing payments to clergy are commonly denoted as “parsonage allowances.” Judge Barbara Crabb of the US District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin, adhering to her earlier conclusion, has recently held the federal income tax exclusion for parsonage allowances unconstitutional.

Judge Crabb’s conclusion that Code Section 107(2) violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment rests on the premises that all tax exemptions constitute subsidies and that the purpose and effect of tax exemptions limited to religious actors are to subsidize religion. The most important articulation of these premises occurs in the US Supreme Court’s decision in “Texas Monthly v. Bullock.” That decision struck as unconstitutional Texas’ sales tax exemption for religious literature.

The parsonage allowance controversy will proceed from Judge Crabb’s trial court to the US Court of Appeals and, perhaps, the US Supreme Court. In these courts, an alternative vantage will be pressed. In another Supreme Court decision, Walz v. Commissioner, Chief Justice Burger condoned for himself and five of his colleagues “permissible state accommodation” “to avoid excessive entanglement” of government and religious institutions. On these entanglement-avoiding grounds, Walz upheld against the constitutional challenge of New York’s property tax exemption for religious properties. From this perspective (embraced by three justices dissenting in Texas Monthly), the income tax exclusion created for parsonage allowances by Section 107(2) is a constitutionally reasonable accommodation between church and state to avoid entanglement between them.

My conclusion (rejected by Judge Crabb) is that Section 107(2) survives constitutional challenge under Walz and that opinion’s approval of religious tax exemptions to minimize church-state entanglement. The income tax exclusion created by Section 107(2) for clerical housing allowances is a plausible (though not compelled) means of reducing the church-state entanglement inherent in taxing religious institutions and actors.

In our society, there is no more entangling legal relationship than the relationship between the tax collector and the taxpayer.

Americans celebrate the separation of church and state. But under modern American tax systems, there is no plausible way to separate completely the secular and the sectarian. When governments tax churches and other religious institutions (as governments often do), the result is church-state entanglement as churches and other religious entities comply with the tax law, and governments enforce the tax law against these sectarian institutions.

If governments exempt from taxation churches and other religious entities, a different type of church-state entanglement occurs, as it becomes necessary at the borders of exemption to determine who is religious and thus qualifies for the exemption. Either way – taxing or exempting – modern tax systems entangle church and state.

The best we can do is minimize the inevitable entanglement between the modern church and modern government. Some taxes entangle more than others. Sales taxes, for example, typically engender less church-state entanglement than other taxes since most sales are easily valued cash transactions in which the purchaser has the additional cash to pay the tax. It is thus unsurprising that many states subject religious institutions, as buyers, sellers or both, to their less entangling sales taxes.

On the other hand, the property taxation of churches carries greater possibilities for church-state entanglement since church properties may be difficult to value and since churches (like other property taxpayers) may lack cash to pay the tax. It is thus equally unsurprising that every state in the union exempts from property taxation houses of worship – though the states vary among themselves in their respective policies toward the property taxation of church-owned housing and of religious facilities such as a summer camps. Some states tax these kinds of religious facilities. Other states do not.

In the broader context articulated in Walz, the federal government’s decision to exclude from income taxation parsonage allowances is a “permissible state accommodation” “to avoid excessive entanglement” of government and religious institutions.

Permitted does not mean required. As a matter of tax policy, cash parsonage allowances are more closely analogous to the sales taxes which states often impose on churches than to the property taxes from which churches are exempt. Like cash sales, parsonage allowances involve easily valued cash transactions between clergy and their respective congregations and other employers. As a matter of tax policy, it is fairer and more efficient to tax cash income than to exclude it from the tax base.

Thus, the higher courts should, on the authority of Walz and its entanglement-avoidance rationale, overturn Judge Crabb’s decision and confirm the constitutionality of Internal Revenue Code Section 107(2) and the income tax exclusion that provision extends to parsonage allowances. On the other hand, as Congress seeks to reform the federal income tax by broadening the tax’s base to lower the tax’s rates, the income tax’s exclusion of parsonage allowance should be one of the many provisions Congress should repeal.

Featured image credit: Religious escape by Tim Wright. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post The constitutionality of the parsonage allowance appeared first on OUPblog.

Herpes and human evolution: a suitable topic for dinner?

Politics and religion are always topics best avoided at dinner and it’s perhaps not too much of a stretch to add STIs to that list. But it was over dinner at King’s College, Cambridge that my colleagues Charlotte Houldcroft, Krishna Kumar, and I first started to talk about the fascinating relationship humans have with Herpes.

The Herpesviridae are a fascinating family of DNA viruses. Found across the animal kingdom in everything from humans to corals, mammalian herpes viruses date to around 180-220 million years ago and have split into three sub families: Alpha, Beta, and Gamma. The Herpes Simplex genus belongs to the Alpha subfamily as does the genus Varicellovirus (which in humans gives us chickenpox and shingles). As mammal species diverged, the herpes simplex virus went with them. If we fast forward to the present and take the primates as an example, each species of primate generally has their own unique form of herpes simplex virus. The word Herpes comes from the ancient Greek herpien meaning ‘to creep’ and a better description of the virus is hard to imagine. Through a combination of being highly infectious, periods of latency and teasing the body’s immune system, herpes is a superbly adapted group of viruses that look like they will be keeping humans company for a long time to come. The classic ‘tingle’ on the lips of an imminent cold sore is in fact herpes simplex virus reactivating within a facial nerve, to eventually emerge as a blister on the lips or around the mouth.

Humans are relatively unusual primates by any standard but also when it comes to herpes. While most primates only carry their own form of herpes simplex (e.g. ChHV in chimps & MHV1 in macaques) humans have two forms: HSV1 which causes cold sores and HSV2 which causes genital herpes. What’s interesting is that while HSV1 has co-speciated with humans, HSV2 is more closely related to chimpanzee herpes. A 2014 paper by Joel Werthiem and colleagues compared the phylogenies (family trees) of the viruses and their primate hosts and demonstrated that HSV2 jumped to the human lineage sometime between 3-1.4 million years ago but suggested no further refinements could be made. To us this was a challenge in the form of classic detective story and we began to design a way to try and identify the culprit. Or to put it another way ‘who did what to whom’!

Trying to reconstruct an event that happened millions of years ago obviously presents a number of issues as all studies that use fossil data are working with imperfect records of the past. When it came to unravelling the mystery of the extra herpes virus the problem was essentially to try and identify the route of transmission from the ancestral chimpanzee population to a hominin species we know is ancestral to Homo sapiens. Once HSV2 gains entry to a species it stays, easily transferred from mother to baby, as well as through blood, saliva, and sex. Since HSV2 is ideally suited to low density populations, because it causes a life-long, rarely fatal infection, genital herpes caused by HSV2 would have crept across Africa the way it creeps down nerve endings in our sex organs – slowly but surely.

Paranthropus boisei – forensic facial reconstruction. Draw made by Cicero Moraes and 3D scanning of the skull by Dr. Moacir Elias Santos. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Paranthropus boisei – forensic facial reconstruction. Draw made by Cicero Moraes and 3D scanning of the skull by Dr. Moacir Elias Santos. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.We began by collating data ranging from fossil finds to genital herpes prevalence and ancient African climates. Data from palaeoclimate records served as a proxy for where the chimpanzees’ ancestors were during the time window (because fossils don’t preserve well in tropical conditions only one chimp ancestor has currently been found from around 500,000 years ago) and this formed our reservoir of HSV2. Climate fluctuations over millennia caused forests and lakes to expand and contract so layering climate data with fossil locations helped us determine the species most likely to come into contact with ancestral chimpanzees in the forests, as well as other hominins at water sources. Naturally there are a number of known unknowns here but we have taken care to control for variability in our analysis in terms of time and space. Our models then tested for the most likely route of infection and produced a suspect that we weren’t expecting. Paranthropus boisei (P.boisei), a heavyset bipedal hominin with a smallish brain and dish-like face, was identified as the culprit.

P.boisei most likely contracted HSV2 through scavenging ancestral chimp meat or coming in to conflict with chimps where savannah met forest – the infection seeping in via bites or open sores. Hominins with HSV1 may have been initially protected from symptomatic HSV2, which would have initially occupied the mouth (as it still does in some people today). That is until HSV2 adapted to a different mucosal niche located in the genitals. Close contact between P.boisei and our ancestor Homo erectus would have been fairly common around sources of water, such as Kenya’s Lake Turkana. The appearance of Homo erectus around two million years ago was accompanied by evidence of hunting and butchery. Once again, consuming infected tissue would have transmitted the virus – only this time it was P.boisei being eaten.

That we can use data from diseases to reconstruct events that are completely invisible to the archaeological and fossil records and well beyond the 400,000 year old age of the oldest ancient human DNA is what we find most exciting. The signals in the HSV2 virus are records of direct contact between the ancestors of us and chimps that we can tangibly now ‘see’ and gives us direct insight into the daily lives of our ancestors. Not a bad result from a herpes-themed chat over dinner.

Featured image credit: Homme d’Olduvai by Pflege24. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Herpes and human evolution: a suitable topic for dinner? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers