Oxford University Press's Blog, page 302

November 11, 2017

“Thank you for your service” isn’t enough [excerpt]

On this Veterans Day, we honor those fallen and herald those still fighting. We also examine what more can be done in terms of listening and understanding those who have seen the perils of war firsthand. In this excerpt from AfterWar: Healing the Moral Wounds of our Soldiers, author Nancy Sherman shares with us her time spent with a veteran of Afghanistan and his feelings on those who expect so much from soldiers and can only offer thanks in return.

At a civilian-veteran gathering in Washington D.C. in early summer of 2012, a young vet came forward, turned to a civilian he hadn’t met before, and said: “Don’t just tell me ‘Thank you for your service.’ First say, ‘Please.’” The remark was polemical and just what was meant was vague. But the resentment expressed was unmistakable. You couldn’t be a civilian in that room and not feel the sting. The remark broke the ice and the dialogue began.

I brought a Marine vet with me that evening who had just finished his freshman year at Georgetown. He wasn’t the vet who spoke those words, but he shared some of the anger.

At twenty-two years of age, T. M. (“TM”) Gibbons-Neff served as a rifleman in charge of an eight-man team in a second deployment to Afghanistan. His unit was among the first to arrive in Afghanistan in December 2009 as part of President Obama’s surge that would send 30,000 additional U.S. troops to try to turn around the course of the eight-year-old stagnating war. Like many of those troops, TM was posted to the southwest of the country, to the violent southern Helmand Province.

Embedded Training Teams conducting Rough Terrain Driving. Credit: “Mtn Viper Trainin” by Cpl. Brian A. Tuthill, USMC. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Embedded Training Teams conducting Rough Terrain Driving. Credit: “Mtn Viper Trainin” by Cpl. Brian A. Tuthill, USMC. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.On the evening of day one of the first mission, on the edge of a Taliban-held village, TM and two other teammates were crouched down on the highest rooftop they could find, surveying the nooks and crannies where the insurgents could hide and arm. They had their scopes on several who looked suspicious, but they drew no fire and so just kept to their lookouts. Then, it got “sporty,” says TM, in his measured way, with lightning rounds and pops coming in from three different directions. Two rounds hit the arms of his buddy, Matt Tooker, just as he stood up to launch a grenade; another ricocheted off the body armor of his light gunner, Matt Bostrom, leaving severe chest wounds. Less than 24 hours into the mission, and TM was already down two out of his eight men. The game plan had totally shifted: he had been the observer and now he was the primary shooter, and needed to find another observer. By the end of the day he was squarely in the role of “strategic corporal,” the apt term coined by retired Marine Commandant General Charles Krulak for a low guy on the noncommissioned totem pole, typically in a remote and dangerous outpost, away from direct supervision, having to implement quick tactical and moral decisions with far-reaching strategic implications. For TM, resuscitating the mission all-consumed him. Even the thought that he had two friends who had just got badly wounded barely surfaced. He was operating in “code red.” Not even the most subliminal, sweet thoughts of home and his girlfriend darted through his mind.

In due course the losses sunk in. And more losses piled on. A year and a half later, Matt Tooker, shot that night, was killed in a motorcycle crash back home. TM is pretty sure it was the culmination of risky, suicidal behavior: with a maimed arm, he could no longer hold the sniper role that had come to define him. Two other close friends were killed in action in Afghanistan in May 2010. TM’s Marine career had begun with his father’s death (a Vietnam War Navy veteran), just days after TM had arrived at boot camp. “I’m no stranger to people I know getting ripped out of my life pretty quickly,” he says, at twenty-four, with a war weariness that doesn’t easily match his boyish looks and small frame. The names of his three fallen best buddies are engraved on a black bracelet he wears on his right wrist. It is his own memorial, a place to remember his buddies by touch, the way visitors run their fingers over the names on the Vietnam Wall.

TM has done his share of grieving and visiting team members at Walter Reed Hospital who weren’t as lucky as he. Still, the grief and the visits fuel a deep sadness about what he thinks of as the futility of some of his missions in Afghanistan. When he first got to Georgetown University, the loose political banter on the social media sites about the need to intervene in various conflict areas around the world—Libya, Iran, Syria—riled him. It was hard to watch his peers beating the war drums while fully insulated from the consequences of deployments. The media- and philanthropy-backed campaign against the Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony and his abduction of children as soldiers in his Lord’s Resistance Army (launched through the popular YouTube video “Kony 2012”) made him especially resentful of his classmates’ sense of comfortable entitlement. His own losses were still fresh. He didn’t want to see more: “You know, a thing like Kony . . ., and all these people saying, ‘We should do more. What are we going to do about it?’ You’re not going to go over there! . . . That will be our job, and then more of my friends will get buried, and then you guys can talk about it on Facebook. That’s what upsets me. . . . The politics. The policy. The rant. . . . Oh, you want to go over there and stop Kony. Hey, you YouTube watcher: Is this going to be you?. . .”

I am not saying don’t support that political agenda. Or don’t think about those little kids who are dying out there. But what about our kids who are dying out there!

TM did not hit the Send button on any of the Facebook replies he composed. Instead, he went on to write about his war experience—for the New York Times war blog, the Washington Post, Time, the Atlantic, the Nation, and other war blogs. He has served as executive editor of Georgetown’s student newspaper, The Hoya. A year or so after we met, he took a seminar I taught on war ethics, and helped create in that class a remarkable civilian– veteran dialogue. And he has done that on campus, too, serving as the head of the campus student veteran association. He is processing his war publicly and reflectively in writing and community outreach. But his early feelings of resentment, like those of the veteran who turned to the civilian that night, are important to hear and important to try to understand.

Those feelings are, in part, resentment at too easy a beating of the war drums by civilians safe from battle, infused with militarism at a distance.

Featured image credit: U.S. Marines prepare to leave Border Fort 12 via helicopter, May 2005 by Sgt Michael A. Blaha. Public domain via

Wikimedia Commons.

The post “Thank you for your service” isn’t enough [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

November 10, 2017

On burnout, trauma, and self-care with Erin Jessee

Last week, Erin Jessee gave us a list of critical questions to ask to mitigate risk in oral history fieldwork. Today, we’ve invited Jessee back to the blog to talk more in-depth about her recently published article, “Managing Danger in Oral Historical Fieldwork,” spotting signs of trauma during interviews, and dealing with the sensitive nature of oral history.

You note that discussion of dangerous or distressing research encounters are common in “corridor talks” among oral historians, yet rarely make it into the scholarly literature. What kind of feedback or reactions have you had from colleagues as you make these conversations more public?

Since the article went online, I’ve had a handful of emails thanking me for taking the time to write it, as it’s helping oral historians think through the dangers they’ve faced in past projects, and begin assessing potential future dangers. I also presented a few key points from the article at the Oral History Association meeting in Minneapolis, and the responses were entirely positive and supportive of the idea that—particularly given the recent deregulation of oral history in the United States—we can and should be doing more to assess danger in our work. Most oral historians seem to at least recognize the need to be more open about the potential for danger or emotional distress resulting either directly from the difficult narratives to which they’re exposed or from the personal wounds that these narratives reopen. The few resistant individuals tend to come from other fields, and object on the grounds that it wrongly detracts attention away from our participants. I understand this concern, but I think we need to find a balance between acknowledging the potentially negative impact our research can have on our mental and physical health—ideally, to create an environment that offers practitioners who are struggling more support—while still privileging participants’ narratives.

How can oral historians do a better job of spotting signs of trauma in each other, and responding positively?

This is important, because I get the impression that many oral historians feel embarrassed or ashamed to admit when their physical and mental health has been negatively impacted by their research. Many of us are navigating heavy workloads, and it doesn’t seem practical to suggest that we all undertake formal training in counselling. Likewise, we may not all be in positions where we’re able or willing to take on the often-unpaid emotional labor that is demanded of us in helping our colleagues process personal or work-related crises, particularly when it extends beyond a momentary bad mood or emergency. But there are things we can do in our professional lives that can make it easier for us to support our colleagues when they’re in distress or minimize the potential for that distress to occur in the first place. For example, Beth Hudnall Stamm’s tips for self-care are helpful for resilience-planning in advance of fieldwork but also include small acts that people can incorporate into their everyday lives. Over time they can help to make them not only more aware of the sources of stress and harm they navigate in their work, research, and personal lives, but also make us more supportive and empathetic colleagues and coworkers.

Because of the sensitive nature of your work, some of the life histories you record must ultimately be destroyed. Have you had any difficulty navigating that reality with narrators who want to have their full story told, or institutions and scholars that want access to the primary data?

Because I’ve incorporated a very thorough informed consent process throughout my fieldwork, and most of the people I’ve interviewed are intimately familiar with the potential risks they face in participating in the research project, I haven’t encountered any resistance from participants to destroying the interviews we’ve conducted in the past. I should note, however, that the destruction of these interviews was a requirement of the ethics committee at the university where I conducted my doctoral studies, the underlying research design for which underwent review in 2007. I haven’t heard of any researchers in recent years being required to destroy their fieldwork data. Indeed, current best practices seem to allow for the anonymization of any materials that contain personally identifying information, and limited archiving—usually closed to the public and future researchers unless permission is given by the original researcher and/or participants.

That said, with the push to demonstrate positive public impact in academic research, I have noticed some tensions between researchers, and university administration and funding agencies. In the UK, universities often maintain online repositories in which oral historians are expected to deposit their interviews, as well as associated publications, to comply with open access requirements. Funding agencies can, as a starting point, require researchers to make use of these repositories as a condition for applying for funding. The tensions emerge around researchers’ concerns that while these repositories include options for closing sensitive materials to the public, they’re still held online and, as such, are hackable. Researchers’ efforts to remove any personally identifying information prior to depositing data in these repositories doesn’t eliminate the possibility of someone’s face or voice being recognized in the event these materials do find their way into the outside world. As such, researchers who are conducting research on potentially sensitive subject matter often feel they are inappropriate for archiving their data, particularly for older projects in which these online repositories were not discussed as a potential means of archiving or dissemination for the interviews entrusted to us.

Is there anything you couldn’t address in the article that you’d like to share here?

The US Oral History Association (OHA) has formed a Task Force charged with revisiting the organization’s Principles and Best Practices in light of deregulation and the increasingly authoritarian political climate in the US. The Task Force will be presenting the revised best practices for discussion at the OHA meeting in Montréal in October 2018. Meanwhile, in the UK, the Oral History Society and the Oral History Network of Ireland are organizing what will undoubtedly be an important conference in June 2018 on Dangerous Oral Histories: Risks, Responsibilities, and Rewards. This means there will be lots of opportunities for oral historians to publically discuss the challenges they face in their research, as well as strategies for more effectively anticipating and managing danger, regardless of where and with whom they are conducting interviews.

What self-care strategies do you utilize? Chime into the discussion in the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Featured image credit: “Exhaustion” by Jessica Cross. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post On burnout, trauma, and self-care with Erin Jessee appeared first on OUPblog.

Sentence structure for writers: understanding weight and clarity [extract]

Some sentences just sound awkward. In order to ensure clarity, writers need to consider more than just grammar: weight is equally important.

In the following extract from Making Sense, acclaimed linguist David Crystal shows how sentence length (and weight) affects writing quality.

Say the following two sentences aloud. Which of them is more natural and easier to understand?

It was nice of John and Mary to come and visit us the other day.

For John and Mary to come and visit us the other day was nice.

I’ve tested sentence pairs like this many times and never come across anyone who prefers the second sentence. People say things like it’s ‘awkward’ and ‘clumsy’; ‘ending the sentence with was nice sounds abrupt’; ‘putting all that information at the beginning stops me getting to the point’; and ‘the first one’s much clearer’.

Here’s another example. Which of these two sentences sounds more natural?

The trouble began suddenly on the thirty-first of October 1998.

The trouble began on the thirty-first of October 1998 suddenly.

Again, the first is judged to be the better alternative. The second sentence doesn’t break any grammatical rules, and could easily turn up in a novel, but few people like it, and some teachers would correct it.

What both these examples show is the importance of length, or weight. The first pair illustrates how English speakers like to place the ‘heavier’ part of a sentence towards the end rather than at the beginning. The second pair shows a preference for a longer time adverbial to come after a shorter one. Both illustrate the principle of end-weight. It was a principle that the prescriptive grammarians recognized too. In his appendix on ‘perspicuity’, Lindley Murray states several rules for promoting what he calls the ‘strength’ of sentences. His fourth rule is: ‘when our sentence consists of two members, the longer should, generally, be the concluding one’.

Children learn this principle early in their third year of life. Suzie, for example, knew the phrase red car, and around age two started to use it in bigger sentences. But she would say such things as see red car long before she said things like red car gone. In grammatical terms: she expanded her object before she expanded her subject.

It will be that way throughout her life. Adults too in their conversational speech keep their subjects short and put the bulk of the information after the verb. Three-quarters of the clauses we use in everyday conversation begin with just a pronoun or a very short noun phrase:

I know what you’re thinking.

We went to the show by taxi.

The rain was coming down in buckets.

Only as speech becomes more formal and subject matter more intricate do we encounter long subjects:

All the critical remarks that have been made about his conduct amount to very little.

Taking in such a sentence, we feel the extra demand being made on our memory. We have to keep those eleven words in mind before we learn what the speaker or writer is going to do to them.

Longer subjects, of course, are common in written English, as in this science report:

The products of the decomposition of diaryl peroxides in various solvents have been extensively studied by Smith (1992).

A really long subject, especially one containing difficult words or concepts, may make such a demand on our working memory that we have to go back and read the sentence again, as in this tax-return instruction from the 1960s:

Particulars of the date of sale and sale price of a car used only for the purposes of your office or employment (or the date of cessation of use and open market price of that date) should be furnished on a separate sheet.

This is the kind of sentence up with which the Plain English Campaign did not put. And indeed, as a result of that campaign, tax returns and other documents for public use have had a serious linguistic makeover in recent years.

In speech, if a subject goes on for too long, listener frustration starts to build up, as it’s difficult to retain all the information without knowing what’s going to be done with it:

My supporters in the party, who have been behind me from the very outset of this campaign, and who know very well that the country is also behind me …

We urgently need a verb! It’s a problem that can present itself in writing too, as when we read a slowly scrolling news headline on our television screen that begins like this:

The writer and broadcaster John Jones, author of the best-selling series of children’s books on elephants, and well-known presenter of natural history programmes on BBC2…

…Has won a prize? Has died? Has joined Real Madrid? Once, the scrolling subject went on for so long that I had forgotten the name of the person by the time the sentence came to an end, announcing his death.

Long subjects can be a problem for children in their early reading. The sooner they get to the verb, the sooner they will get a sense of what the sentence is about. So a sentence such as this one presents an immediate processing difficulty:

A big red jug full of warm milk was on the table.

Eight words to hold in mind before we get to the point. The end-weight principle suggests it would be easier to read as:

On the table was a big red jug full of warm milk.

Featured image credit: “coffee-school-homework-coffee-shop” by ejlindstrom. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Sentence structure for writers: understanding weight and clarity [extract] appeared first on OUPblog.

The history of medical ethics

On the 20th of August 1947, 16 German physicians were found guilty of heinous crimes against humanity. They had been willing participants in one of the largest examples of ethnic cleansing in modern history. During the Second World War, these Nazi doctors had conducted pseudoscientific medical experiments upon concentration camp prisoners and the stories that unfolded during their trial – The Doctors’ Trial – were filled with descriptions of torture, deliberate mutilation, and murder.

Though the nature of their crimes was undeniably impermissible, the doctors’ defence argued that their experiments were not so different from others that had been conducted prior to the war. They claimed that there was no international law governing what was, and what could not be, considered ethical human experiment. As a result, the judges presiding at this tribunal recognised the need for a comprehensive and sophisticated way to protect human research subjects. They drafted the Nuremberg Code: a set of ten principles centred upon the consent and autonomy of the patient, not the physician. 2017 marks 70 years since the creation of the Nuremberg Code, and its influence on human-rights law and the field of medical ethics is undeniable. Discover the history of medical ethics, from Hippocrates to the present day, in the interactive timeline below.

Featured image credit: An alchemist reading a book; his assistants stirring the cible on the other side of the room. Engraving by P.F. Basan after D. Teniers the younger, 1640/1650. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The history of medical ethics appeared first on OUPblog.

November 9, 2017

50 years after the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement

From 15-18 November, members of the American Society of Criminology (ASC) will gather in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania for the ASC’s annual conference. The theme of this year’s meeting is Crime, Legitimacy, and Reform: 50 Years After the President’s Commission. Specifically, 2017 marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of the final report of the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, appointed by President Lyndon Johnson in 1965. The aim of this report was to gather evidence with regard to the problem of crime in the United States and the federal government’s role in fighting it and reforming the nation’s criminal justice system. Entitled, The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society the report contained 200 recommendations that, according to the Commission, collectively constituted “a call for a revolution in the way America thinks about crime.” The Commission called for more training and education for law enforcement; change to juvenile justice and adult corrections centered on rehabilitative ideals; and greater research on the causes, consequences, and responses to crime.

Given that there are more than 1,000 sessions and roundtable discussions on this year’s program, the ASC conference itself stands as evidence of the impact of the President’s Commission. But if one peruses the Commission’s report, it quickly becomes clear that their conceptualization of crime was a narrow one; the Commission was largely concerned with street crime, including drug offenses. This is perhaps not surprising, since the Commission was appointed in the wake of civil rights demonstrations and riots to which law enforcement responded with sometimes deadly force. Fifty years later, a substantial number of papers at the ASC conference will address the continuing problem of police use of deadly force, particularly against African Americans, which, in itself, should prompt sober reflection among conference attendees.

Conspicuously absent from the Commission’s report was any discussion of gender-based violence, including intimate partner violence and sexual assault. It was not until the late 1970s that this problem began to get sustained attention, chiefly as a result of the women’s movement and feminist consciousness rising, and political activism. Feminist criminologists published research documenting the prevalence of gender-based violence, its consequences for victims, and the ineffective, and typically, victim-blaming criminal justice response that essentially allowed perpetrators to act with impunity. The ASC’s Division on Women and Crime (DWC), which was established in 1984 by feminist criminologists interested in studying gender, crime, and criminal justice, is now the largest ASC division, and sponsors numerous paper sessions at the annual conference that address gender-based violence. But now presentations on gender-based violence are found throughout the program, not only in DWC-sponsored sessions, which indicates the tremendous growth in this area of research in the relatively short span of about four decades. Many of these presentations will emphasize the intersectional nature of gender-based violence – that is, how gender intersects with other sites of social inequality (e.g., race and ethnicity, social class, sexual orientation, age, immigration status) to produce differences in victimization, perpetration, and criminal justice responses. Moreover, a substantial number of presentations will address cross-national differences in gender-based violence.

As ASC conference attendees reflect on the legacy of the President’s Commission this year, it behooves us, especially in the contemporary political climate, to critically examine specific social constructions of crime, and the (sometimes deadly) consequences of ignoring the salience of intersecting inequalities in criminal offending, victimization, and the workings of the criminal justice system.

Featured image credit: people woman shadow by StockSnap. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post 50 years after the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement appeared first on OUPblog.

Singing insects: a tale of two synchronies

What is a chorus, what is an insect chorus, and why might we be interested in how and why singing insects create orchestral productions? To begin, chorusing is about timing. In a chorus, singers align their verses with one another in some non-random way.

When singing insects form a chorus, the alignment may only be a crude grouping of song during a given time of the day or night; e.g. a midday or evening chorus. But in the case of insect species that repeat discrete song units – calls, chirps, buzzes, etc. – in rhythmic fashion, the chorus may be much more refined. Here, neighboring singers may adjust the period and phase of their rhythms such that their song units are synchronized or alternate with one another. It is these high-precision choruses, particularly those that involve collective synchrony, that draw a lot of interest. Analogous phenomena occur in insects that generate visual displays, notably fireflies, and these too intrigue us. Perhaps our fascination is driven by an intrinsic appreciation for pattern in space and time.

Insect synchronies are about long-range advertisement songs that males broadcast to females. What makes male insects synchronize when females are within earshot? Three explanations may account for this cooperation among males. First, synchrony may preserve the clarity of rhythm or discrete song units within a local group that nearby females need to hear before moving toward any one male. Under these circumstances, a male who does not synchronize can reduce his neighbor’s attractiveness, but in so doing he will also jeopardize his own, a spiteful act that selection is not expected to favor. Second, synchrony may pose a cognitive problem for predators and parasites who listen to the advertisement songs of their prey and hosts before attacking. That is, when sound arrives from myriad directions, pinpointing any one source may be difficult. Third, synchrony would maximize the peak sound intensity that a local group of males broadcast, affording a group that synchronizes a longer radius of attraction than a comparable group that does not bother to. While these are seemingly cogent explanations based on sensory perception and ecology, it is worth noting that rather little supporting evidence exists. Neighboring males can achieve regular synchrony by making various call timing adjustments. A simple but effective mechanism recently found in European bushcrickets is to refrain from initiating a call for a 600-900 ms interval following the endings of neighbors’ calls.

Image credit: Ephippiger diurnus male by Gilles San Martin. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Ephippiger diurnus male by Gilles San Martin. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.An alternative to the adaptationist paradigm – which underlies the above propositions – is that complex synchronous displays may just emerge as an incidental byproduct of simple pairwise interactions between neighboring males. Importantly, these pairwise interactions are generally competitive, not cooperative. For example, hearing in acoustic animal species often entails attention to the first of two (or more) calls separated by a brief time interval and then ignoring the second call. ‘Leading call effects’ may originate as neural mechanisms that improve sound source localization, but when they occur in females evaluating potential mates they are expressed as a preference for the first male to sing.

Consequently, males come under intense selection pressure to play ‘timing games’ with each other that limit production of following calls and increase leading ones. A common game is deploying a ‘phase-delay mechanism’ that 1) resets the (central nervous system) rhythm generator regulating one’s calls to its basal level upon hearing a neighbor, 2) inhibits the generator by locking it at that basal level until the neighbor’s song ends, and then 3) releases the normal, free-running call rhythm. Simulations show that when males with comparable songs deploy this mechanism, a structured chorus emerges. The chorus is a synchronous one if rebound from inhibition approximates the normal rhythm, but alternation arises if the rebound is a bit faster. But even where nearest neighbors alternate, a considerable amount of synchrony occurs in the chorus: Males generally exhibit ‘selective attention’ to their nearest neighbor, which means that when males C and D each alternate with male B, C and D then synchronize. Some recent tests confirm that this type of structured chorusing may occur in the absence of any female preference for synchrony or alternation per se; i.e. the males who generate the chorus do not benefit from their overall production.

Because synchronies may arise from cooperation or competition, the study of insect choruses can offer some insight to the roles of these opposing forces in shaping behavior. Experiments with two closely related, chorusing bushcricket species, Sorapagus catalaunicus and Ephippiger diurnus, have yielded some surprising findings. S. catalaunicus males generate regular synchrony, and it was expected to reflect a necessity to maintain discrete calls for attracting females. E. diurnus males generate a mixture of alternation and synchrony, expected to emerge from competition to reduce the incidence of following calls, which females ignore. But tests showed that females in both species needed to hear discrete calls clearly separated by silent gaps, and females in both also had a strong preference for leading calls. It was inferred that call length, long in S. catalaunicus and short in E. diurnus, influenced the outcome by selecting for a specialized mechanism ensuring silent gaps in S. catalaunicus. These findings show how a small difference in a very basic trait can trigger a cascade of evolutionary events, ultimately influencing the emergence of rather dissimilar behavior characterizing social interactions at the level of animal groups.

Featured image credit: “Banner Header Sound Wave Music Wave” by TheDigitalArtist. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Singing insects: a tale of two synchronies appeared first on OUPblog.

Animal of the month: nine facts about badgers

Badgers are short, stocky mammals that are part of the Mustelidae family. Although badgers are found in Africa, Eurasia, and North America, these animals are possibly best-known from their frequent appearance in literature, such as “Badger” from The Wind in the Willows and Hufflepuff’s house animal in the Harry Potter series, and for being a 2003 internet sensation. But a part from recognizing badgers in books and Youtube videos, what do you know about these animals?

For the month of November, we’re celebrating badgers – starting with nine interesting facts about these popular musteloids.

While badgers are known for living in burrows, European badgers dig the most complex dens, or “setts”, which are passed down from one badger generation to the next. The largest sett excavated was 879 m (0.54miles) of tunnels, and had 129 entrances.

Despite typically being a solitary animal, some badgers have been known to live in symbiosis with other animals when foraging for food. In particular, the honey badger and a small bird called the black-throated honey guide work together. When the bird discovers a hive, it will search for a badger and guide it with its song to the hive. The honey badger will then open the hive with its claws, so it can feed on honeycomb, while the bird eats bee larvae and wax.

While badgers are found on several continents, Eurasian badgers are the most widespread mustelids, with their habitat ranging from the British Isles to South China.

Climate change has been impacting badger populations. Milder winters brought on by global warming can lead to an increase in badger populations, where as reduction in rainfall can have a negative impact on cub survival rates.

A female American Badger about four years old at the Oxbow Zollman Zoo in Olmsted County, Minnesota by Jonathunder. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

A female American Badger about four years old at the Oxbow Zollman Zoo in Olmsted County, Minnesota by Jonathunder. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.One of the most comprehensive, long-term studies of medium sized carnivores anywhere in the world focuses on badgers. This study, which is located in Wytham Woods in Oxford, was started in 1972 and is still on-going today.

Despite usually being solitary creatures, a past study shows that European badgers may partition the collective responsibility of marking their territories through latrine use. Patterns of latrine use showed that individual badgers did not defecate at the section closest to where they happened to be active, but rather according to a pattern resulting in comprehensive, regular group coverage of their territory border.

Badgers are omnivores, eating a diet of insects, plants, and small vertebrates (such as rabbits, ground squirrels, hedgehogs, prairie dogs, and gophers). European badgers are particularly dependent upon earthworms, and have been known to eat several hundred in one night.

In the United Kingdom, badgers have been known to transmit bovine tuberculosis (bTB) to cattle. Badger culling, an attempt to control the disease in cattle by killing badgers, has been among the most controversial issues in wildlife disease management globally.

Recent studies have shown that badgers are substantially more fearful of humans than of their extant or extinct carnivore predators. Badgers’ reactions in response to audio recordings of bear, wolf, dog, and humans were tested and showed that badgers delayed foraging when they heard dog or bear recordings, but they would completely refrain from foraging until the human audio playbacks were completely off.

Featured image credit: Badger photo by Hans Veth. CC0 public domain via Unsplash.

The post Animal of the month: nine facts about badgers appeared first on OUPblog.

Crime and punishment, and the spirit of St Petersburg

Crime and Punishment is a story of a murder and morality that draws deeply on Dostoevsky’s personal experiences as a prisoner. It contrasts criminality with conscience, nihilism with consequences, and examines the lengths to which people will go to retain a sense of liberty.

One of the factors that brought all these things together was the novel’s setting, around the Haymarket in St Petersburg, where the grandeur of the imperial capital gives way to poverty, squalor, and vice. The city here is not merely a backdrop but reflects the imposition of the will of one man, its founder Peter the Great, who famously decreed its existence and oversaw its building, which cost the lives of thousands of slaves. In Notes from Underground, the narrator describes St Petersburg as ‘the most abstract and premeditated city in the whole wide world’ – again alluding to that problem of abstraction and its potential to elevate ideas over lives. In this most ideological and willed of cities, the most ideological and willed of murders seems bound to happen.

Crime and Punishment embodies the spirit of St Petersburg to the extent that the character of Raskolnikov seems willed into existence by the city itself. Dostoevsky’s own dramatic life and rejection of the radical ideas of his youth led him to discover this combination. It produced a novel that still speaks to us as strongly today as it did when it was first published 150 years ago.

Trace the footsteps of the characters around the city, with quotes taken from the novel, with this interactive map.

Featured image credit: St Petersburg Russia by MariaShvedova. Creative Commons via Pixabay.

The post Crime and punishment, and the spirit of St Petersburg appeared first on OUPblog.

What’s going on in the shadows? A visual arts timeline

Although cast shadows lurk almost everywhere in the visual arts, they often slip by audiences unnoticed. That’s unfortunate, since every shadow tells a story. Whether painted, filmed, photographed, or generated in real time, shadows provide vital information that makes a representation engaging to the eye. Shadows speak about the shape, volume, location, and texture of objects, as well as about the source of light, the time of day or season, the quality of the atmosphere, and so on.

Reattaching a Shadow, Peter Pan, Disney Studios, 1953. Figure 1.1, Grasping Shadows: The Dark Side of Literature, Painting, Photography, and Film (OUP 2017) by William Chapman Sharpe.

Reattaching a Shadow, Peter Pan, Disney Studios, 1953. Figure 1.1, Grasping Shadows: The Dark Side of Literature, Painting, Photography, and Film (OUP 2017) by William Chapman Sharpe. But as the famous example of Peter Pan’s amputated shadow reveals, shadows depicted in artworks can be arbitrarily shaped, placed, and even cut off by their creators. Therefore, beyond offering physical information, shadows have much to tell us on a social and psychological level. Consciously or not, whenever we see shadows we “read” them (and their creators’ intentions) in a cultural context that lends the shadows power or denies their substance, causing them to seem prophetic or threatening or willful or wispy. In the course of a dozen images, this timeline shows how some of the key meanings of cast shadows have developed over the centuries.

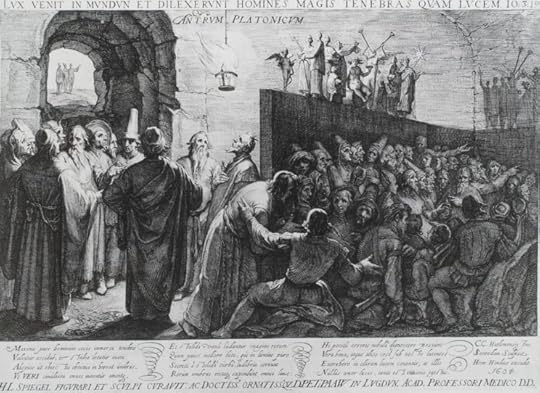

1. Since classical times, artists, scientists, and philosophers have argued about the value of shadows. The ancient Greeks were the first artists to use cast shadows, as they developed a “geometry of the light” that located objects in relation to a consistent light source. Mistrusting the way that shadows helped such painters to deceive the eye, Plato insisted that shadows mislead people about the true nature of reality. In his Allegory of the Cave (375BCE), Plato set up a shadow-substance opposition that has dominated Western thinking about shadows ever since.

Jan Saenredam (printmaker) and Cornelis van Haarlem (artist), Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, 1604. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

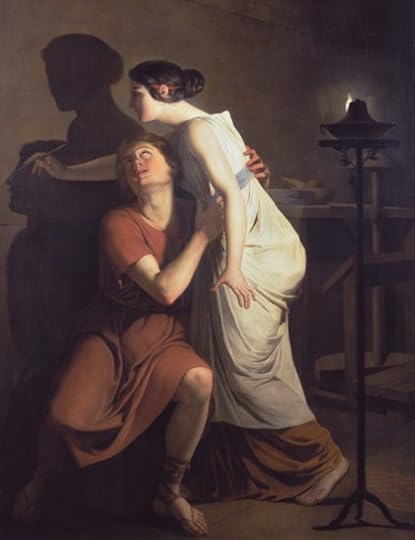

2. As if to challenge Plato’s reasoned dismissal of shadows, the Roman historian Pliny the Elder asserted in his Natural History (79 CE) that art was born when a young woman named Dibutades traced the shadow of her lover on a wall, by the light of a lamp. Since the lover was about to leave on a long journey, the shadow image not only became the first human-made representation, it also became an almost magical substitute for his presence. While Plato thought that shadows were dangerously false, Pliny suggested that they could be romantically true, as if to capture a person’s shadow was to capture part of his vital essence.

Joseph Benoit Suvée, The Invention of the Art of Drawing, 1793. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

3. The story of Dibutades was highly popular in the 18th Century, when it reinforced the vogue for a new form of shadow-capture, silhouettes. In English, cut-paper silhouettes were first known as Shadowgraphs or Shades, since they were often made by tracing a person’s shadow. Silhouettes exploit one of the key features of the shadow, its dark, mysterious interior, into which viewers can project whatever details imagination can provide.

Thomas Holloway, A Sure and Convenient Machine for Drawing Silhouettes, 1792. Figure 2.17, Grasping Shadows: The Dark Side of Literature, Painting, Photography, and Film (OUP 2017) by William Chapman Sharpe.

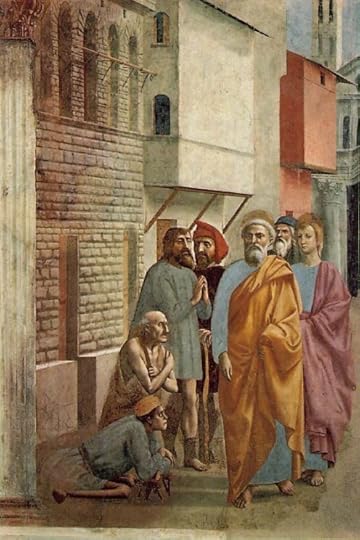

4. Meanwhile, after a dormant period in medieval times, Renaissance artists returned to the Greco-Roman shadow and developed its use in relation to the emerging art of perspective. Shadows became more accurately shaped and placed, even as unwritten rules governed their use so that they would not impinge too greatly on the human figure. In Masaccio’s The Tribute Money (1425), for example, cast shadows cover the ground but never obscure the human form.

Masaccio, The Tribute Money, Brancacci Chapel of the basilica of Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, 1425. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

5. In the first painting to make a shadow its primary subject, Saint Peter Healing the Sick with His Shadow (1427-1428), Masaccio made sure that the transformative shadow of St. Peter falls around and under the figures that it touches with its heaven-sent power. Like many villainous shadows later to come, the holy shadow has a special power that emanates from its source, but the Renaissance painter will not let the shadow dominate the work pictorially.

Masaccio, St. Peter Healing the Sick with his Shadow, 1427–1428. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

6. From the Renaissance onward, most painted shadows serve to make objects seem more “real” in volume and placement, but Rembrandt was a pioneer in giving the shadow psychological weight. In an early self-portrait he depicts himself with his eyes in shadow, as if to show how his very vision is embedded in the chiaroscuro that makes his paintings so dramatic.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait, 1629. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

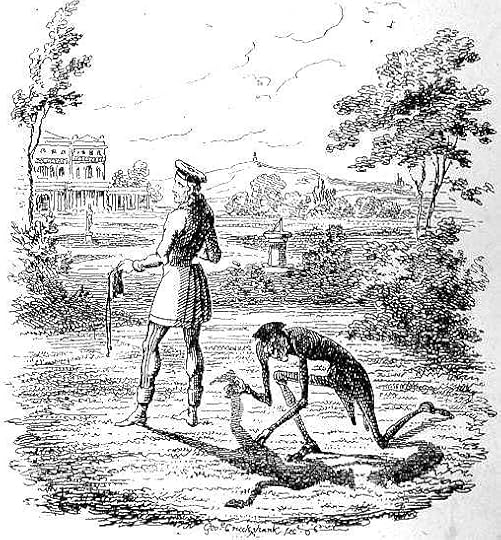

7. After the Renaissance, the Western world adapted so well to the idea that artistically rendered people need shadows that the absence of a personal shadow could cause a great commotion. Illustrated by many artists, Adelbert von Chamisso’s story of Peter Schlemiel, the man who sold his shadow (1814), became a big hit in Europe in the early nineteenth century. Since Peter’s acquaintances would have nothing to do with a man who had no shadow, it became clear from the story that having a shadow was a sign of humanity, a signal of full participation in human life.

George Cruikshank, Peter Schlemihl Selling His Shadow, 1827. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

8. But only a few decades later, the first stand-alone shadows of humans appeared in art, independent of anybody to cast them. It was as if the shadow alone could now do the work of the substance-shadow couple. It was William Collins who discovered in his painting Rustic Civility (1833) just how visually effective a “mere” shadow could be, introducing a powerful narrative element at the same time. Here children open a gate for their social “betters,” in the form of a horseman who represents the English country gentry.

William Collins, Rustic Civility, 1833. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Used under Fair Use via Wikimedia Commons.

9. The advent of photography was initially regarded as a matter of “fixing a shadow.” Henry Fox Talbot explained his process in 1839 by saying that, using chemistry, he had found a way to capture “the most transitory of all things, a shadow.” The way photographs “drew” with light connected them in the public mind withs to Pliny’s story of tracing shadows on a wall. The poet Elizabeth Barrett wrote to a friend in 1843, that a photograph was like “the very shadow of the person lying there fixed forever!”

Clementina Hawarden, Isabella Grace, 5 Princess Gardens, 1861—1862.Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Figure 2.18, Grasping Shadows: The Dark Side of Literature, Painting, Photography, and Film (OUP 2017) by William Chapman Sharpe.

10. As cinema developed, film directors rapidly picked up the atmospheric and dramatic shadow-vocabulary used by painters since the time of Caravaggio and Rembrandt. In classics such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Nosferatu, the German Expressionists made shadows into active participants in the drama. “Murder by shadow” soon became an integral part of cinematic lore.

The Shadow’s Prey, Nosferatu, directed by F. W. Murnau, 1922. Used under Fair Use.

11. More recently, artists have used actual shadows made by high-powered lights to construct interactive street art in which people can encounter their own shadows in settings that reveal just how alien yet also reassuring shadows can be.

Mario Martinelli, Meeting the Shadow, 2013. Used under Fair Use.

12. Wherever art goes, advertising soon follows. Some of the latest forms of advertising use immaterial shadows to sell tangible goods. If in contemporary art the shadow plays, on today’s billboards the shadow pays.

Ellis Gallagher and Pablo Powers, “The Lighter Side of Dark,” 2011. Used under Fair Use.

Featured image: Photo of shadows by terimakasih0. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post What’s going on in the shadows? A visual arts timeline appeared first on OUPblog.

November 8, 2017

The last piece of wool: the Oxford etymologist goes woolgathering

I have never heard anyone use the idiom to go woolgathering, but it occurs in older books with some regularity, and that’s why I know it. To go woolgathering means “to indulge in aimless thought, day dreaming, or fruitless pursuit.” Sometimes only absent-mindedness is implied. There seems to be an uneasy consensus about the idiom’s origin, but, although I cannot offer an alternative etymology, I am afraid that the existing one should be abandoned.

According to my database, this idiom has been discussed only in the popular press of the relatively recent past (the earliest reference I have goes back to The Gentleman’s Magazine for March 1789 and the latest to Notes and Queries for 1889-1890) and dictionaries, but dictionaries do not say anything one cannot find in the periodicals. The main obstacle in our research is that the phrase surfaced in print in the middle of the sixteenth century, while the conjectures about its historical background are late. Some information was probably lost between 1553 (the date of the earliest citation in the OED) and 1789. If the idiom originally meant what it means today, it may have been coined at one of the peaks of the process known in English history as enclosure (or inclosure), though wool industry and wool trade in England goes back to the beginning of the Common Era.

David, as a young man, playing pipe and bell as he watches his sheep in the pasture.

David, as a young man, playing pipe and bell as he watches his sheep in the pasture.E. Cobham Brewer, the author of the once immensely popular Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, wrote this: “Your wits are gone wool-gathering. You are in a brown study. Your brains are asleep, and you seem bewildered. The allusion is to village children sent to gather wool from hedges; while so employed they are absent, and for a trivial purpose. To be wool-gathering is to be absent-minded, but to be so to no good purpose.” It is amusing that Brewer referred to the idiom in a brown study “in a state of deep reverie or gloomy meditation,” which does not seem to have crossed the Atlantic (see my post for 22 October 2014) and may be obsolete even in England. Perhaps its source is French. The problem with Brewer’s book is that it contains few or no references to the sources. How did he find the origin of the idiom? Did he suggest it himself or did he read it somewhere? In any way, those who have tried to account for the existence of the odd phrase remained more or less at the level of Brewer’s explanation.

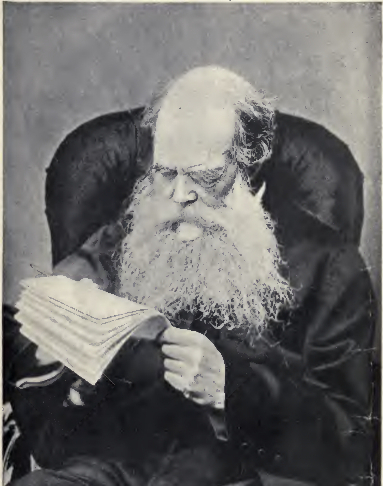

This is E. Cobham Brewer, the author of numerous books, but only one is still remembered and available, though abridged and revised.

This is E. Cobham Brewer, the author of numerous books, but only one is still remembered and available, though abridged and revised.Did anyone ever gather wool from hedges? This is the testimony of the correspondents to Notes and Queries. The phrase was coined “in allusion to the poor old women, generally too infirm for other work, who go wandering by the hedge-sides to pick off the small bits of wool left by the sheep on the thorns. Perhaps one of poorest and most beggarly of all employments.” In response to this statement the following was said in 1889: “… wool-gathering was not very long ago a common practice in pastoral districts, and was not ‘the most beggarly of all employments’…. I have known substantial farmers who did not disdain to go out of their way for the purpose of picking wool off the thorns and hedges; and the wool thus gleaned was found very useful… for stuffing horse-collars, cushions, mattresses, &c…. the wool so procured would be of considerable service to cottagers for spinning into blankets; and it is quite a mistake to suppose that our proverb has any contemptuous intentions. It refers rather to the wide and irregular range of such wanderings as the wool-gatherer’s.”

Nor were children spared this job, as said in the once popular and later satirized tract The Shepherd of Salisbury Plain (1795). There it is “mentioned that even the very young children could be usefully employed in gathering the locks of wool found on the bramble bushes and thorns, which wool was carded and spun during the winter evening and made into stockings.” The reading of The Shepherd of Salisbury Plain shows that, even though gathering wool was not a “beggarly” occupation, it was left for poor people to indulge in. According to one opinion, woolgathering was an employment “so poor and unremunerative that well-wishers of their species could not help feeling pity for those who had no better employment. They had to wander through many fields painfully to pick from the thorns small scraps of wool torn from sheep generally poor and lousy.” The correspondent continues: “So when it is said of one that his ‘wits are gone wool-gathering’, I understand by it that his [a nice reference to poor women, small children of both sexes, and one] mind is wandering, and wandering where it is not likely to find anything of value.” But even at the end of the nineteenth century the possible value of the wool collected by children in a season could come to four hundred pounds. (For the curious: we are told by knowledgeable people that the children used to catch up the bits of wool quickly by means of short sticks with a bit of notched iron hoop at the end.)

Gone a-woolgathering.

Gone a-woolgathering.Most appropriately, Wordsworth’s sonnet was quoted in the exchange: “Intent on gathering wool from hedge and brake/ Yon busy Little-ones rejoice that soon/ A poor old Dame will bless them for the boon;/ Great is their glee while flake they add to flake/ With rival earnestness….” Let us leave the “little-ones’” rejoicing for another occasion and rather remember the poor old Dame. As a final flourish, I may quote Thomas Blount (1618-1679; his book Fragmenta Antiquitatis… is quoted in my sources). A certain Peter de Baldewyn was expected to gather wool “for our Lady the Queen from the White Thorns, if he chose to do it; and if he refused to gather it,” he had to “pay twenty shillings a year at the King’s Exchequer.” This statement makes us wonder whether the earliest wool gatherers were beggarly (poor) women and very young children. The very task we are discussing may need another definition. The correspondent to The Gentleman’s Magazine thought that ancient woolgathering “was no mere gleaning from hedge and bush, but a collection of a sort of rent-charge in wool exigible from tenants.”

I am returning to the beginning of the story. To my mind, the idea that gathering wool from thorns and bushes “necessitated much wandering to little purpose,” as The Century Dictionary tentatively put it, cannot be substantiated: the wandering was “goal-oriented” and needed a lot of attention. Its results were far from negligible. As early as the 1550’s, the phrase was current in the figurative meaning still familiar to us. It takes some time for the direct sense of a phrase to develop into an obscure metaphor. We will probably never find out who was the first to kick the bucket or pay through the nose (see the posts for 24 September and 15 October 2014), but there must have been a connection between the act and the idiom. Woolgathering has nothing in common with daydreaming or absentmindedness. Nor is it (to repeat!) a fruitless pursuit. Perhaps in the beginning it designated a process different from the one people observed in the recent past.

All these ideas are of course classic exercises in woolgathering, and I’d rather not go too far afield. It suffices to repeat that the origin of our idiom is unknown and that what is said in dictionaries about it should be taken with a huge grain of salt.

Many a mickle makes a muckle.

Many a mickle makes a muckle.Image credits: Featured and (4): “Tufts of wool on barbed wire fence” by Neil Theasby, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Geograph. (1) “David, as a young man, playing pipe and bell as he watches his sheep in the pasture.” by Anonymous. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) “E. Cobham Brewer image in 1922 book” by London, New York [etc.] Cassell and Company, Limited, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) “Child, school, girl” by Cole Stivers, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The last piece of wool: the Oxford etymologist goes woolgathering appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers