Oxford University Press's Blog, page 305

November 2, 2017

The Bolivarian (r)evolution: the perpetual liberation of Venezuela

Ignoring both domestic and international protests, Venezuela’s president Nicolás Maduro has recently overseen the creation of a Constituent Assembly with the power to dissolve parliament, rewrite the constitution, and remove any remaining checks on his power. But this should not be interpreted merely as a power grab by yet another desperate ruler. History’s invisible hand is at work, playing out a recurring theme that has haunted Venezuela since its formation by Simón Bolívar.

On his deathbed in 1830, Bolívar wrote a letter to the new president of Ecuador, General Juan José Flores, encouraging him to flee the continent: “The country is bound to fall into unimaginable chaos, after which it will pass into the hands of an undistinguishable string of tyrants of every color; Once we are devoured by all manner of crime and reduced to a frenzy of violence, no one — not even the Europeans — will want to subjugate us.”

Now, almost 200 years later, Bolívar’s quote seems prescient. Ironically, he himself became the prototype for the series of democratically elected leaders turned autocrats.

With each generation the mythical stature of Bolívar has increased.

Simón Bolívar swept to power on the back of his legendary military victories against impossible odds. Riding a white horse and donning a cape, he freed much of the Spanish-speaking Americas from colonial rule. And while he started out a staunch democrat, he ended his rule as a dictator and was eventually cast out to die alone and in poverty. In spite of his ignominious final days, in death his flaws were soon forgotten and his virtues enhanced until they took on mythical proportions.

The embellishment of Bolívar’s legend started twelve years after his death. Oddly, it also involved the repeated exhuming of his corpse. In November 1842, seeking to tie himself to the Liberator, President José Antonio Páez successfully repatriated Bolívar’s remains, except his heart, from Colombia to his native Venezuela.

Impressed by the populist impact Páez derived from associating himself with the Liberator’s image, in the 1870s, dictator Antonio Guzmán Blanco decided that he too would dig up Bolívar’s remains and have them transferred to a newly built National Pantheon.

And so it has continued. With each generation the mythical stature of Bolívar has increased.

During the rule of Hugo Chávez, the cult of Bolívar would achieve its apex, as the magical realism of the region’s literary traditions increasingly blended into political rhetoric. Chávez transformed Bolívar from a noun to an adjective, from a historical figure to a spirit, embodied by all his supporters.

Chávez’s infatuation with the Liberator started at the military academy in Caracas where he and a group of like-minded cadets dreamed of economic and social liberation. On 17 December 1982, the anniversary of Bolívar’s death, they formed a Bolivarian revolutionary army, MBR, and repeated the same oath that Bolívar had first uttered when he pledged to devote his life to liberate Venezuela from Spanish oppression: “I will not allow my arm to relax, nor my soul to rest, until I have broken the chains that oppress us.”

From then on, Chávez would incorporate Bolívar into everything he did. Every attempted coup, every speech to the nation, was carried out in the name of the Liberator. The first place Chávez visited after having been pardoned from prison in 1994 was Bolívar’s tomb. And after gaining power in 1999, he had a Bolivarian constitution drafted and renamed the country the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. The Bolivarian revolution was equipped with a Bolivarian intelligence service, Bolivarian universities were founded, and in Avenida Bolívar Chávez campaigned to abolish presidential term limits so that he, like the Liberator, would be able to rule indefinitely. And of course, in 2010, Chávez too dug up the body of Bolívar, an event that was broadcast live to the nation.

After Chávez died of cancer in March 2013, his successor Nicolás Maduro has sustained the “Bolivarian” legacy. On 14 May 2013, Maduro inaugurated a new, $140 million-mausoleum for Bolívar. A 54-meter tall, white-tiled building, it has been likened to the snow-covered Andean peaks Bolívar traversed in pursuit of his Spanish foes.

During Maduro’s rule, Venezuela has descended into a crippling crisis marked by corruption, mismanagement, and widespread shortages of food and medicine. In May 2017, in response to increasing support for the opposition and its latest series of protests, Maduro called a vote for a Constituent Assembly able to grant him and his ruling Socialist Party unlimited powers. Amidst widespread allegations of voter fraud, Maduro announced the greatest electoral victory the Bolivarian revolution had ever seen: “It’s when imperialism challenges us that we prove ourselves worthy of the blood of the liberators that runs through the veins of men, women, children and young people.”

Maduro is now in the final stages of the “Bolivarian evolution”: the transition from democrat to dictator, and as such he will remain in power until the next Liberator rises from the people to free them, most probably also in the name of Simón Bolívar. As Bolívar left behind countless speeches and writings, full of contradictions, most political standpoints can find support somewhere in his canon. While he started out professing that “regular elections are essential to popular government” and “a nation in which one man rules is a nation of slaves,” he later conceded that dictatorship was the only way to accomplish anything when ruling an uneducated and “immature” people. Consequently, Bolívar drafted a new constitution, giving the president the power to rule for life and select his own successor.

Maduro is not a lone despot. Nor will he be the last. He is simply another turn in Venezuela’s Bolivarian cycle of perpetual liberation.

Featured image credit: Venezuelan flag by Alexander Rodriguez. CC0 via Pixabay

The post The Bolivarian (r)evolution: the perpetual liberation of Venezuela appeared first on OUPblog.

The origins of performance anxiety

Please consider the following questions before reading further. (1) When does performance anxiety begin? (2) When did you get your first review? (3) Who is your most severe critic? (4) Who is your best supporter?

We all heard our first musical melodies in the voices of our mothers or fathers – when they talked to us, smiled in response to our gurgles, and sweetly sang lullabies. We cooed back to them or relaxed and slept peacefully. We were held, fed, and had our diapers changed. We were comforted, and soothed –all in response to our cries – our first songs. Together we composed a duet. This is an ideal scenario, but parents are not always able to satisfy all our needs. Both gratification and lack of gratification have a profound impact on our lifelong psychological development.

Image credit: Piano “Children Child Music Instrument Musical” by coyot. CC0 via Pixabay.

Image credit: Piano “Children Child Music Instrument Musical” by coyot. CC0 via Pixabay.As infants, we learn – or begin to sense – that we have enormous power to make others respond to us. Of course, we don’t know that rationally, but the nursery provides the stage for our first performance and our ability to have an effect upon (m)others. We were taken care of by our first adoring critic. Our earliest hours and days in the nursery began a life long process of learning to trust others and establish the foundations for self-esteem. It is awesome to reflect upon the enormous power of the newborn to command other people! Our very first review to our music came in the nursery. Therein begins our sensitivity to the reactions of others to our music – and an important root of our performance anxiety.

Noted psychologist and educator Erik Erikson has written about human development from a biological, psychological, and social perspective encompassing the entire life cycle. His famous chart, “The Eight Stages of Man,” is in his book Childhood and Society (1950). I have found his ideas particularly helpful to understanding the importance of development in musicians, particularly so since children begin to study musical instruments at very young ages. The first four stages of Eriksons’s chart are explained below in the context of stage fright in adolescents. All eight stages are discussed in Managing Stage Fright, where practical strategies for dealing with performance anxiety are suggested based on age.

Erikson discusses adaptive and maladaptive outcomes of each stage (not right or wrong outcomes). There are tasks to be balanced as we grow. Each stage is believed to be embedded in subsequent stages as we compose our unique life histories. We do not outgrown earlier stages, but incorporate how we navigate the previous stage into the next. Anxiety can lead us to regress to earlier stages. In reading the brief summaries below, keep in mind that ages are approximate for each stage but are illustrative for normal development and that there are potential impediments that risk healthy development at every stage.

Stage 1 (Birth-1 year ): Trust vs Mistrust

Physical and emotional care is received from mother and caregivers. The baby learns to trust the “other” for basic needs. This early relationship lays the foundation for trust in self as well as ability to have an impact upon the “other” with cries, gurgles, coos, smiles – all non-verbal sounds. Non-verbal sounds are our first music performances and communication with others.

Stage 2 Ages 2-3: Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt

The toddler learns to walk, talk, use the potty, and develop pleasure in controlling him/herself and others. Toddler talk i.e., boo boos, making a mess, accidents” is typical language that refers to bodily functions that can be heard in phrases performers use about having “accidents” on stage. Developing physical and emotional self-control is a precursor to acquiring self esteem. “His Majesty The Baby”, a title Freud coined to connote the “power” of the newborn, gradually compels the baby to relinquish instant gratifications of infancy. This does not always happen smoothly or without sensitive help from parents. The child, now upright in walking and talking, is increasingly independent and yet still dependent on others.

Stage 3 Ages 4-6: Initiative vs. Guilt

The births of siblings, special love for the parent of opposite sex, observing sexual and generational differences are accompanied by envy, greed, and other longings for approval and fears of rejection. Some children begin piano lessons during this stage. Winning and losing approval become paramount as the music teacher is mentally experienced as a parental figure. Students later search for approval and being favorites (winners) by juries at competitions.

Stage 4 Ages 7-12: Industry vs. Inferiority

Many children begin music lessons at this age and are very motivated to seek favor by teachers, juries, audiences who can reward with applause and “love”. In fact, the audience becomes the metaphor for the parents who can love – or reject – the child. The stage of the nursery gradually becomes a stage for a concert.

Psychological development and musical development share common psychological pathways from our earliest years about how we feel about ourselves and others. This includes our feelings about how we can have an effect on others (or not) or control (or not ) them through our music-making.

Image credit: IMG_3261 by Kian McKellar. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: IMG_3261 by Kian McKellar. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.For musicians (and other types of performers), this often surfaces as a wish for a “perfect performance” in order to receive “perfect” love and nurturance from the parent/audience. We received our “first review” from our parents in the nursery. The nature of these earliest interactions shapes our psychological development forever after – including stage fright.

When discussing the quest for “perfection”, I emphasize the importance of coming to terms with our own and others’ imperfections. I was pleased to receive responses from readers, including from one teacher who spoke of a healthy attitude about performing. With the teacher’s permission, I quote her below:

“I stress always that we are making music: this is not a test; making music is not an athletic event to see who the fastest, etc is. It is about expressing something through sound…I tell the students that the music already exists, that the composer endeavors (imperfectly) to notate it, that we endeavor (imperfectly) to realize this already extant music. The “imperfect” is a given. The only questions are, “Did we make music, share something, express something?”

Featured image credit: “Audience Concert Music Entertainment People Crowd” by Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post The origins of performance anxiety appeared first on OUPblog.

November 1, 2017

Which fictional TV Lawyer are you? [quiz]

Have you ever watched a legal drama on TV and wondered what kind of lawyer you’d be? Perhaps you’d have a soft spot for the underdog, or maybe you’d take on any case so long as the money was good? Perhaps working on criminal cases would be your thing? Either way, you’d need to know the legal system inside and out.

Take our quiz to find out which TV lawyer you might be.

Featured image credit: ‘Supreme Court of the United States’ by Phil Roeder. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Which fictional TV Lawyer are you? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

October etymological gleanings continued

There is a good word aftermath. Aftercrop is also fine, though rare, but, to my regret, afterglean does not exist (in aftermath, math– is related to mow, and –th is a suffix, as in length, breadth, and warmth). Anyway, I sometimes receive letters bypassing OUP’s official address. They deal with etymology and usage. As a rule, I answer them almost at once, and our correspondence remains known only to the questioner and me. But some queries may be interesting to a larger audience. Also, in September I was a guest on Minnesota Public Radio. There was no time to respond to all the calls from the listeners, and I decided to take care of some old letters and recent questions now.

Why does until mean the same as till? Shouldn’t until mean the opposite of till? No. Until, which is a borrowing from Scandinavian, goes back to und-til, in which und– means practically the same as –til. This word is a tautological compound (I have often written about such words). Both its elements are of Scandinavian origin. The same un– can be seen in the now obsolete preposition unto. Much more often one has to explain why inflammable means the same as flammable. The prefix in– here means “inside,” as opposed to in-, occurring in such words as inept and insecure.

One of the most common questions I receive concerns the pronunciation of February as Febuary (the second variant is extremely common, perhaps even prevalent, in American English). I have a distinct recollection that I have already dealt with this recalcitrant word, but the answer must have been part of some gleanings, and I can no longer remember where it occurred years ago. Here is a brief comment. The earliest recorded Middle English forms of February are feouerles and feouerreres moneð. The first of them already shows the speakers’ trouble with r…r. The word’s Old French etymon was feverier (the modern form is almost the same: février), which traces back to Latin februārius. The Roman februa festival of purification was held on February 15. The early Modern English spellings were febery, febveray, and the like. Dickens recorded the pronunciation Febouary. The modern literary pronunciation is fully Latinized. It can be seen that both variants (with the first r and without it) are extremely old. The preference of so many people for Febuary can have two reasons. The loss of the first r may be due to dissimilation: when two identical sounds occur in close contact, one often disappears or is changed. But it is also possible that, when people say January, February, they allow the form of the first word to affect the form of the second. This process has been observed in the history of numerals. For instance, four may have “borrowed” its initial f from five. The letter I received reads so: “I wish someone would teach the pronunciation of February. Each year I suffer for a month when people say Febuary instead of February.” Beware of self-inflicted wounds! People have been saying something like Febuary for seven centuries. Consequently, the hope of changing their habits is slim. From a historical point of view, if by history we understand tradition and longevity, both pronunciations are equally old. Today’s written form is certainly February, but English speakers are so used to writing mute letters that those who prefer –buary should take the variant with r…r without demur.

FEB(R)UARY. The word is tricky, but the month is providentially short (even this year).

FEB(R)UARY. The word is tricky, but the month is providentially short (even this year).Why do so many people say kidden instead of kitten? Indeed, in American English, t is voiced only between vowels, so that Plato and playdough, Sweetish and Swedish become indistinguishable. In the students’ papers, I have come across title wave and deep-seeded prejudices. (Guess the “etymology” of both phrases.) But rotten, cotton, written, smitten, and their likes are not affected by this process. With regard to kitten, I can offer only one explanation for what it is worth. A kitten is often called kitty, and kitty, naturally, becomes kiddy. From kiddy the consonant d seems to have made its way into kitten. Compare margarine. The word has so often been pronounced in its short form marge that margarine became marjarine.

A typical title wave.

A typical title wave. Here is a kiddy with a kidder (an exercise in American English phonetics.

Here is a kiddy with a kidder (an exercise in American English phonetics.Is it correct to say: “I feel badly”? Not by a long chalk, though it depends on how long one wants the chalk to be. Compare: “I feel happily,”—something that no one would say. But several facts should be taken into consideration. People often confuse good and well and say “I am good” instead of “I am well.” This is odd, even though we hope that everybody around us is both good and well. On the other hand, adjectives sometimes oust adverbs in a rather alarming way. I hear again and again: “She sings beautiful,” as though the speaker is German. However, the line is easy to cross. Consider loud and loudly. Don’t speak so loud. It obviously means “don’t speak so loudly.” It sounds good, the moon shines bright (the variant the moon shines brightly is, I think, acceptable, but it sounds well is nonsense), come back real quick, drive slow, and many, many others, including fast, an adverb, and fast, an adjective, show how tenuous the line between adjectives and adverbs (and not only in unbuttoned colloquial speech) is in Modern English. So no wonder that people begin to say: “I feel badly.”

Here is somebody who is both good and well.

Here is somebody who is both good and well.Different than versus different from. This is another old chestnut. All manuals of usage and dictionaries that have “panels” touch upon these phrases. It appears that different than, rare in British English, enjoys great popularity in the US. Conversely, different to, fully acceptable in GB, sounds exotic in American English. Different from is more logical because people and things differ from, not than or to one another. Moreover, than is associated with comparison (bigger than, worse than). But, as I keep repeating more with sadness than conviction, if very many people say something, their norm becomes at least partly acceptable. Ain’t has been hounded out of respectable society, but, like John Barleycorn, it refused to die. Lay instead of lie (lay down and have a rest) is irrational and ugly, but millions of people think otherwise. So has it become rational and beautiful, like millions of other things since the Middle English period and even Shakespeare’s time? In American English, I cannot but think has almost killed its more respectable synonym I can’t help thinking. Examples of this kind can be multiplied ad libitum. To sum up, even though swimming upstream may be a waste of time and effort, different from is still preferable.

Data: singular or plural? This question has also been asked many times. From the etymological point of view data is of course a neuter plural form of a Latin noun, but English speakers can (or cannot?) care less for Latin and “decided” that data is singular. It is possible to say data are. However, those who say so are few, and being better than one’s neighbor may invite the accusation of snobbery. Agenda is a neuter plural form of a Latin gerund. How many people remember that, and do those who remember say agenda are?

Many letters I receive deal with adverbs: “thankfully, I am healthy,” “hopefully, we’ll win,” “actually, the weather is not bad.” Actually has become a pest (“World War One actually began in 1914”—this is another quotation from a student’s paper) and should be weeded out of “polite conversation,” except when it is meaningful (“Did you actually [= really] mean it?”). Thankfully and hopefully would be all right if they had not been overused. They have become clichés. We hear them all the time; hence their jarring effect. And in this context isn’t fortunately better than thankfully? Reinforcing adverbs like actually, certainly, and definitely are often used to make a weak conclusion sound convincing. “He is really a good man” (there is something suspicious behind this forceful statement), “it is certainly true” (is it?), “this book is definitely the best” (perhaps). The clinching argument should depend on facts and logic rather than on rhetoric. Yet when we speak, we want to convince the audience, and all’s grist that comes to the mill, but a weapon used again and again of necessity becomes blunt.

Featured image credit and (2): “Girl, kitten” by Amanda McConnell, Public Domain via Pixabay. Image credits: (1) “February calendar” by Photos Public Domain, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) A Woman in Blue (Portrait of the Duchess of Beaufort) by Thomas Gainsborough, Public Domain via WikiArt.

The post October etymological gleanings continued appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford Philosophy Festival, 16th–19th November 2017

Oxford University Press and Blackwell’s are delighted to team up once again to host the Oxford Philosophy Festival to celebrate the quest for knowledge and ideas. This year, our theme centres around applying philosophy in politics. Come and join us as we discuss religious liberty and discrimination with John Corvino, the benefits of a marriage-free state with Clare Chambers, the true nature of the oil industry with Leif Wenar, and much more. If you’re not able to attend in person, please enjoy our online resources on these important issues, along with our content on World Philosophy Day.

More information, along with registration links to these free events, are below.

Clare Chambers’ Against Marriage book launch

Thursday 16th November 2017, 19:00 – 20:00 GMT

At our first event of the festival, Clare Chambers will be launching her new publication Against Marriage: An Egalitarian Defense of the Marriage-Free State. In Against Marriage Clare Chambers argues that state-recognised marriage violates both equality and liberty, even when expanded to include same-sex couples. Instead Chambers proposes the marriage-free state: an egalitarian state in which religious or secular marriages are permitted but have no legal status.

Register online for our Clare Chambers event.

Very Short Introductions speed dating event

Friday 17th November 2017, 19:00 – 20:00 GMT

The Very Short Introduction series is a fabulous way of being introduced to a new subject, containing over 500 different books in the series. At this event, audience members will have the opportunity to meet six expert authors who have each written a Very Short Introduction book. In small groups moving around the Norrington room, the groups will have a ten minute period with each author, having the opportunity to ask questions and receive a brief introduction to the subjects. The evening will feature:

Maria Rosa Antognazza, Leibniz: A Very Short Introduction

Ian Stewart, Infinity: A Very Short Introduction

Simon Glendinning, Derrida: A Very Short Introduction

Yujin Nagasawa, Miracles: A Very Short Introduction

Susan Blackmore, Consciousness: A Very Short Introduction

Samir Okasha, Philosophy of Science: Very Short Introduction

Register online for our VSI event.

John Corvino on Debating Religious Liberty and Discrimination

Saturday 18th November 2017, 11:30 – 12:30 GMT

John Corvino is the author of What’s Wrong with Homosexuality?, and co-author of Debating Same-Sex Marriage and Debating Religious Liberty and Discrimination. At this event, John Corvino will be delving into the topic covered in his most recent publication, the balance between supporting religious liberty and opposing discrimination, and what we can do regarding legislation in these areas.

Register online for our John Corvino event.

Andrew Copson on Secularism: Politics, Religion, Freedom

Saturday 18th November 2017, 13:30 – 14:30 GMT

Andrew Copson is the Chief Executive of Humanists UK, and author of Secularism: Politics, Religion, Freedom. At this event, Andrew Copson will be discussing the topics in his book further, including the deep tensions a secular state faces from resurgent religious identity politics, and those a religious state faces from insurgent secularists and will consider how secularism connects with contentious issues such as blasphemy, religious persecution, religious discrimination, and freedom of belief.

Register online for our Andrew Copson event.

Leif Wenar on Blood Oil: Tyrants, Violence, and the Rules that Run the World

Saturday 18th November 2017, 15:00 – 16:00 GMT

Leif Wenar is Professor of Politics and Chair of Philosophy at King’s College-London, and is author of Blood Oil: Tyrants, Violence, and the Rules that Run the World. At this event, Leif Wenar will be going into the topics found in Blood Oil, including how today’s natural resource trade runs on the same rule that once made the slave trade, colonialism, apartheid, and genocide legal, and how the West can lead the world the next step forward in history through a peaceful resource revolution.

Register online for our Leif Wenar event.

Richard Marshall on Ethics at 3am

Sunday 19th November 2017, 11:30 – 12:30 GMT

Richard Marshall is the author of Philosophy at 3AM: Questions and Answers with 25 Top Philosophers, and more recently Ethics at 3:AM: Questions and Answers on How to Live Well. At this event, Richard Marshall will be discussing the collection of interviews in Ethics at 3am regarding what ethicists and moral philosophers really think about, and the most pressing concerns in the discipline of philosophy today.

Register online for our Richard Marshall event.

Jonathan Birch on The Philosophy of Social Evolution

Sunday 19th November 2017, 13:30 – 14:30 GMT

Jonathan Birch is the author of The Philosophy of Social Evolution, a fascinating exploration of the role that evolutionary theory can play in understanding the social world. At this event, Jonathan Birch will be interviewed by Elizabeth Hannon on his recent publication, focusing on the evolution of altruism, microbial evolution, and cultural evolution.

Register online for our Jonathan Birch event.

David Edmonds with Jeff-McMahan on Derek Parfit

Sunday 19th November 2017, 15:00 – 16:00 GMT

In our closing event, David Edmonds will be in discussion with Jeff McMahan about the lifetime and achievements of Derek Parfit (1942–2017). Derek Parfit is the author of the bestselling three volume collection On What Matters and Reasons and Persons, one of the most influential books in philosophy of the last several decades.

Register online for our closing event.

If you are in the Oxford area between Thursday 16th and Sunday 19th November, make sure to register for any of the above events and hear from some leading academics on the application of philosophy in politics. We look forward to seeing you at Blackwell’s, Broad Street!

Featured image credit: Justitia, Goddess of Justice. Photo by pixel2013. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Oxford Philosophy Festival, 16th–19th November 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

“Take control”: delusions of sovereignty

The phrase “take control” served as a mantra for the Vote Leave campaign in the United Kingdom’s referendum of 2016 about its membership of the European Union. The country was held to the same constraints and obligations as the EU’s other twenty-seven members. the United Kingdom, as the campaigners declared, could not manage its own borders, organise its own trade, define and regulate the rights of its own citizens ,and, above all, determine its own laws. Admittedly, none of these incapacities was entirely the case; but, taken together and in conjunction with other alleged drawbacks of membership, they surely constituted a dilution of “British sovereignty.” The Leave campaigners explicitly associated “control” with “sovereignty,” and thereby furnished their favoured term with appearances of technical resonance and historical depth.

For the term “sovereignty” is certainly a time-honoured concept, and heavy with legal implications. Traceable to ancient Rome if not to ancient Greece, its origins have been discerned in the emperor’s imperium, authority exercised over a unitary empire, and the source of law from which, as the great jurisconsult Ulpian declared, the legislator himself was absolved. Medieval canonists translated the concept into plenitudo potestatis, ‘fullness of power,’ a level of authority, divinely conferred, which the papal monarch wielded in relation to a universal church.

Image credit: Les Six Livres de la République by Jean Bodin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Les Six Livres de la République by Jean Bodin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Formulation of the secular equivalent for the modern era has been credited to the French jurist and philosopher Jean Bodin who expressed it by means of the term souveraineté. Sovereignty, for Bodin, was “the absolute and perpetual power of a state” (état, république), an entity characterised by “union under the same authority”, an authority indivisible and made manifest through the giving of law “to all in general and each in particular.”

The definition reverberated down the ages, with regular emphasis upon unity. For Hobbes, the “great Leviathan” took shape when a people formed “a real unity of them all” with no “return to the confusion of a disunited multitude” and under the aegis of a “sovereign” as “sole legislator.” For Rousseau, a république is constituted by a “multitude united in one body,” an entity “sovereign when it is active” and possessing a “general will” expressed in the form of law. And for Kant, the “forms of a state” were divided and determined by its “form of sovereignty” and “form of government,” laws in the republican form being acts of the “general will through which the many persons become one nation.”

It would seem, then, that all these thinkers were dealing in much the same set of ideas. But such an appearance of consistency is, of course, misleading. In the history of ideas, considerations of context are of first importance, as is medium of communication: the physical context within which every thinker conducts his or her life, the intellectual context in which each individual pursues his or her thought, and the language in which that thought is expressed. How can products of Kantian rationalism, presented in German in eighteenth-century Prussia, be treated simply on a par with elements of Rousseauian moralism, written in French in Louis XV’s France; or equated with particular outputs of Hobbesian materialism or “scientism,” expressed in English in seventeenth-century England; or married with offspring of Bodinian blends of scholastic and humanist ideas, discussed now in French, now in Latin, in the troubled setting of sixteenth-century France?

Concepts in history are, to borrow a distinguished scholar’s formulation, “culturally embedded.” We have indeed and long since understood that they are not to be treated as nuggets of ideas, inert, objective, transferable from thinker to thinker down the ages and conveying the same essential meaning at every stage. Even so, appreciation of their cultural conditioning requires much more than cursory acknowledgement by means of some categoric term or phrase. Scarcely more adequate for such a purpose are broad overviews, sweeping approaches surveying over several centuries numerous thinkers of multiple cultural provenances. If we are to penetrate what another distinguished scholar has termed “an author’s contemporary world of meaning”, there can be no real substitute for detailed evaluation case by case. And this requires groundwork: in other words, not just ‘intellectual history’, but ‘intellectual biography.’

The historical enterprise has undergone many changes since Carlyle wrote almost two centuries ago of history as “the essence of innumerable biographies.” Yet in the history of concepts, the proposition must still bear much weight. It carries considerable importance for the contemporary world if the validity of political positions supported through casual deployment of portentous terminology such as “sovereignty” is to be properly assessed.

Featured image credit: Plan of Paris c. 1550, attributed to Olivier Truschet and Germain Hoyau. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post “Take control”: delusions of sovereignty appeared first on OUPblog.

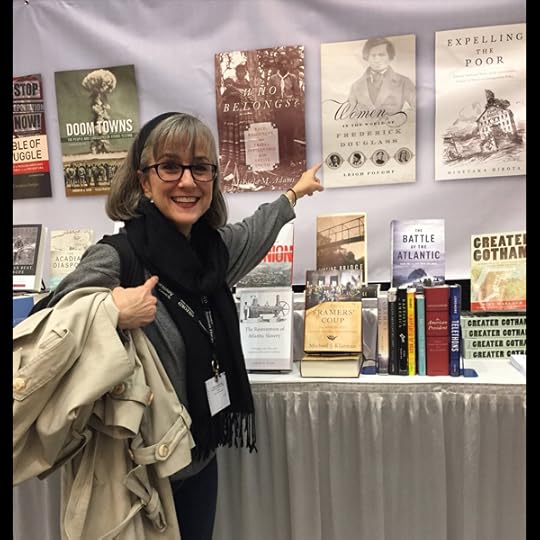

Happy National Author’s Day from OUP [slideshow]

The first of November is National Author’s Day–a day to honor authors and the books that they write. To celebrate, we’ve put together a slideshow of Oxford’s authors pictured at events throughout the year.

Jessica Goodman, Jennifer Rushworth, and Helena Taylor

Pictured: Jessica Goodman (Goldoni in Paris), Jennifer Rushworth (Discourses of Mourning in Dante, Petrarch, and Proust), and Helena Taylor (The Lives of Ovid in Seventeenth-Century French Culture)

Guy Fiti Sinclair

Pictured: Guy Fiti Sinclair (To Reform the World) at the 13th Annual Conference of the European Society for International Law

Mark Steinberg

Pictured: Mark Steinberg (The Russian Revolution, 1905-1921)at the 131st Annual Meeting of the American Historian Association

Jean d’Aspremont and Catherine Brölmann

Pictured: Jean d’Aspremont and Catherine Brölmann (Oxford International Organizations) at the 13th Annual Conference of the European Society for International Law

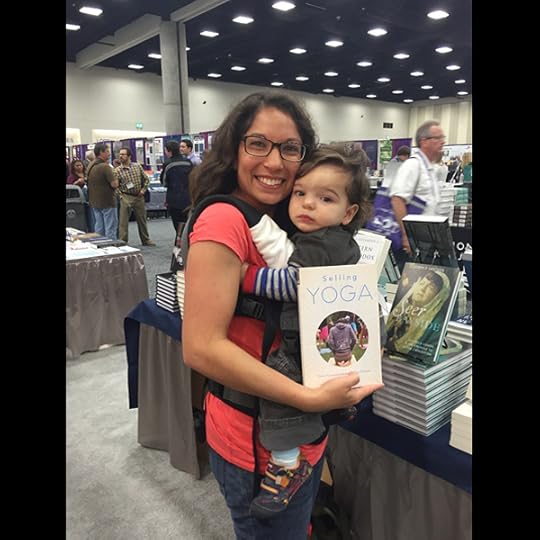

Andrea Jain

Pictured: Andrea Jain (Selling Yoga) at the American Academy of Religion

Kaitlyn Regehr and Matilda Temperley

Pictured: Kaitlyn Regehr and Matilda Temperley (The League of Exotic Dancers) at Oxford’s Book Expo America after-party

Ellen Gruber Garvey

Pictured: Ellen Gruber Garvey (Writing with Scissors) with some of the CBS Sunday Morning team

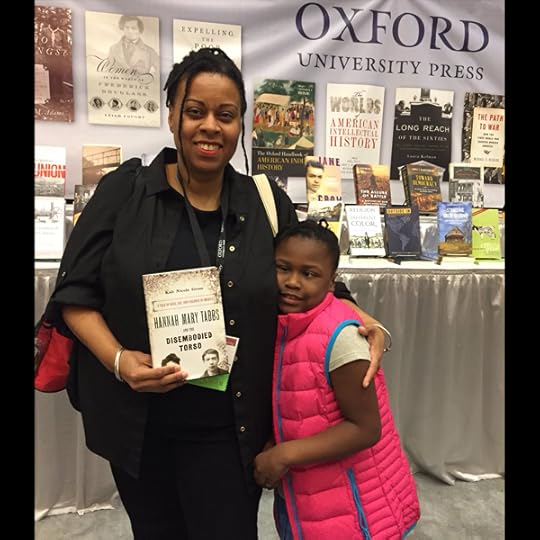

Kali Nicole Gross

Pictured: Kali Nicole Gross (Hannah Mary Tabbs and the Disembodied Torso) at the 2017 annual meeting of the Organization of American Historians

Greg Garrett

Pictured: Greg Garrett (Living with the Living Dead) speaking at his book signing at BookPeople

Michael A. Cohen

Pictured: Michael A. Cohen (American Maelstrom) speaking at Oxford University Press, NY

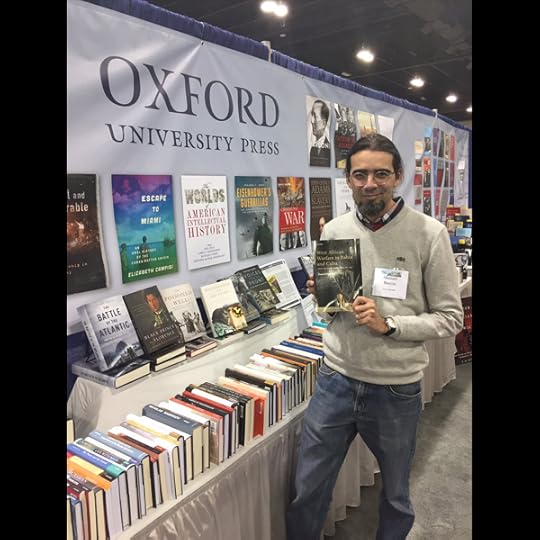

Manuel Barcia

Pictured: Manuel Barcia (West African Warfare in Bahia and Cuba) at the 131st Annual Meeting of the American Historian Association

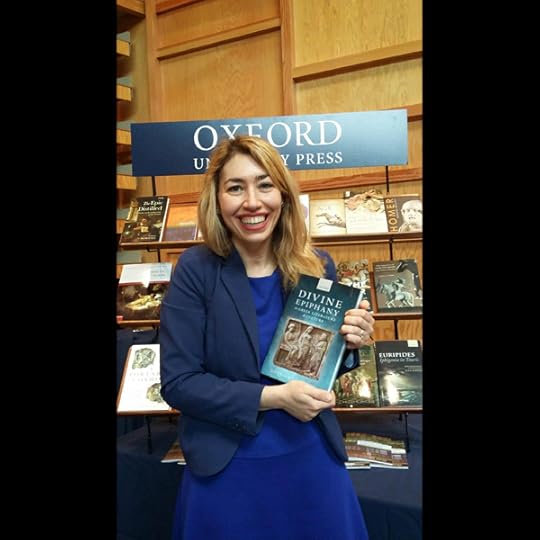

Georgia Petridou

Pictured: Georgia Petridou (Divine Epiphany in Greek Literature and Culture)

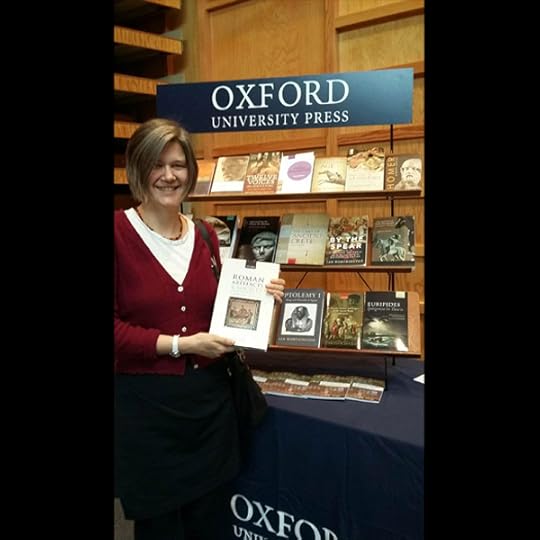

Ellen Swift

Pictured: Ellen Swift (Roman Artifacts and Society)

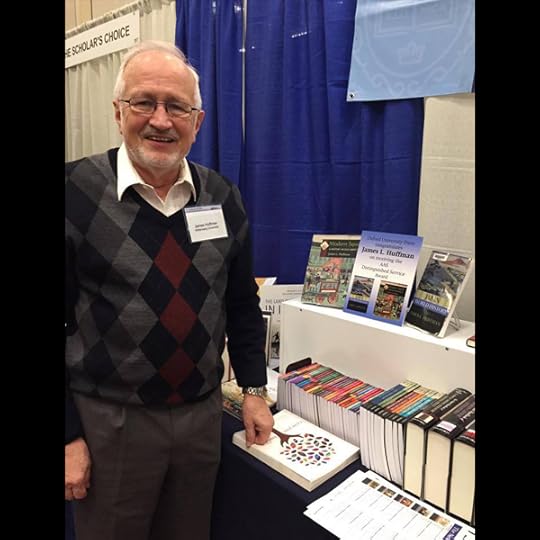

Jim Huffman

Pictured: Jim Huffman (Modern Japan and (Japan in World History) at the 131st Annual Meeting of the American Historian Association, where he was awarded the AAS Distinguished Service Award

Terri Bourus and Gary Taylor

Pictured: Terri Bourus and Gary Taylor, General Editors of The New Oxford Shakespeare

Leigh Fought

Pictured: Leigh Fought (Women in the World of Frederick Douglass) 2017 annual meeting of the Organization of American Historians

Dean Snow

Pictured: Dean Snow (1777) speaking at Oxford University Press, New York

Jaime Kurtz and Greg Garrett

Pictured: Jaime Kurtz (The Happy Traveler) and Greg Garrett (Living with the Living Dead) at Oxford’s Book Expo America after-party

Sara McDougall

Pictured: Sara McDougall (Royal Bastards) at the 2017 Berkshire Conference of Women Historians

James Rushworth

Pictured: James Rushworth (Madness and the Romantic Poet)

Antony Augoustakis

Pictured: Antony Augoustakis, editor of Flavian Epic, Statius, Thebaid 8, and STARZ Spartacus

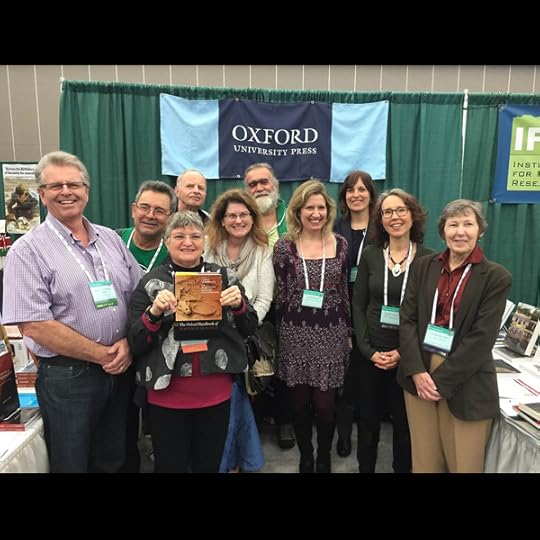

The Oxford Handbook of Zooarchaeology team

Pictured: Members of (The Oxford Handbook of Zooarchaeology) team

Featured image credit: “books-knowledge-school-library” by StockSnap. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Happy National Author’s Day from OUP [slideshow] appeared first on OUPblog.

Q&A with R. Andrew Chesnut on Santa Muerte

Santa Muerte, a skeleton saint, has attracted millions of devotees over the past decade. We spoke to R. Andrew Chesnut, author of Devoted to Death, about the history and origins of Santa Muerte, why she has gained popularity, and the process and challenges of his research on the “Bony Lady.”

For those who don’t know already, could you speak a little about the Santa Muerte cult? What are its origins, where is it most heavily practiced, what are some core beliefs?

Santa Muerte, or Saint Death in English, is a Mexican folk saint that personifies death in the form of a female skeleton. She is the product of syncretism between the Spanish Grim Reapress (la Parca) and Prehispanic beliefs in death deities among certain indigenous groups in Mexico. Spanish Catholic clergy brought the image of the Grim Reapress to the New World as a tool of evangelization of indigenous peoples. Both the Aztecs and Mayas had several death deities in their pantheon of gods and goddesses, so it was natural for many indigenous people to correlate the Spanish Grim Reapress with the Aztec death goddess, Mictecacihuatl, for example. Today, it’s the fastest growing new religious movement in the Americas with an estimated 10 to 12 million devotees across the globe but especially concentrated in Mexico, Central America, and the US Devotees view her as a potent, multitasking miracle-worker who can deliver on petitions quicker than her religious rivals.

What changes in the field have occurred during the time between the first and second editions of Devoted to Death?

Most notably, Santa Muerte has transcended her Mexican roots and claimed devotees among diverse nationalities, ethnicities, and sexual orientations. Here in the US she’s become especially popular among Euro-American LGBTQ individuals. One of the devotional leaders in the US is Steven Bragg, the preeminent Santa Muerte practitioner in New Orleans, who is a gay white man raised in a conservative Protestant denomination in Mississippi. Another major development is condemnation by the Catholic Church in Mexico, at the Vatican, and now even by a few American bishops. The Church views veneration of death as anathema to Christian belief in Jesus having vanquished death on the cross.

Why did you decide to pursue this particular field of study?

I was already two years into a book project on the Virgin of Guadalupe but wasn’t feeling very inspired. In the context of research malaise, the Bony Lady appeared on my laptop on March, 2009, and beckoned me to contemplate her. She appeared in the form of a news item reporting on the Mexican army’s destruction of some forty of her shrines on the Texas and California borders with Mexico. Having traveled in Mexico on a regular basis since the early 1980s I was familiar with the death saint but had no idea that she’d become religious enemy number one of the Felipe Calderón administration in its escalated war on the drug cartels. So after consulting with colleagues and family members, I decided to put the Guadalupe project on hold and plunge into a new one on the intriguing skeleton saint.

R. Andrew Chesnut with a statue of the Santa Muerte. Used with permission.

R. Andrew Chesnut with a statue of the Santa Muerte. Used with permission.What was one particularly exciting fact you learned during your research?

Before starting my research, I had no idea that Santa Muerte is considered a potent Love Doctor! In fact, from the 1940s to the 1980s, love magic was the sole type of supernatural service that Saint Death is reported engaging in by Mexican and American anthropologists who came across her throughout the Mexican republic. Her oldest known prayer, printed on the back of thousands of votive candles, is the love-binding petition to bring an errant husband or boyfriend back to the woman he’s cheating on, humbled at her feet and asking for forgiveness. The red votive candle of love and passion is still the top selling Santa Muerte jar candle in Mexico.

What was the most challenging part of your research?

Balancing safety concerns with my research agenda. With some 200,000 deaths over the past decade in the ongoing drug war, Mexico is surpassed only by Syria in absolute numbers of dead. My wife is from the state of Michoacán, which has been one of the epicenters of narco-violence, and I really wanted to do research there, which I did, without taking major risks.

What are you currently reading (personally or work related)?

The Huron-Wendat Feast of the Dead by Erik Seeman, which explores the common ground provided by the funerary practices of French colonists and the Huron-Wendat nation of Quebec.

What would be your top tips for an aspiring academic author?

While we academics shouldn’t let market forces dictate our research agendas, aspiring authors must consider the potential marketability of their research topics. Even at academic presses, decisions whether to publish are partly driven by sales potential. Within the relatively obscure field of Latin American religion, I have chosen research topics of broader interest, such as charismatic Christianity and Santa Muerte.

How do you see your field evolving in the future?

I operate in several fields, but I think Religious Studies will develop an even greater focus on lived religion and spirituality in the digital age.

What is your next project?

My new research project is on Catholic death culture in the West, particularly material expressions, such as memento mori, ossuaries and holy relics. I spent last summer in Portugal and Italy doing field work.

Featured image used with Permission of R. Andrew Chesnut.

The post Q&A with R. Andrew Chesnut on Santa Muerte appeared first on OUPblog.

October 31, 2017

How well do you know Confucius? [quiz]

This October, the OUP Philosophy team honors Confucius (551 BC–479 BC) as their Philosopher of the Month. Recognized today as China’s greatest teacher, Confucius was an early philosopher whose influence on intellectual and social history extended well beyond the boundaries of China. His lessons emphasized moral cultivation, stressed literacy, and demanded that his students be enthusiastic, serious, and self-reflective.

How much do you know about Confucius and his teachings? Test your knowledge with our quiz below.

Quiz image: Image of Confucius circa 1770. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image: Temple in Chongming Island, Shanghai, China. Photo by Joshua Wickerham. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How well do you know Confucius? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

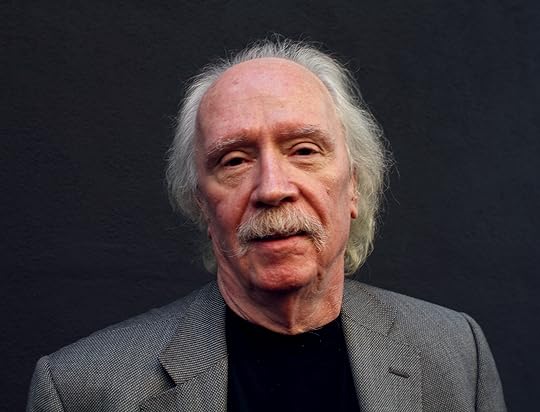

Horror films reinforce our fear instincts: Q&A with John Carpenter

John Carpenter’s classic suspense film Halloween from 1978 launched the slasher subgenre into the mainstream. The low-budget horror picture introduced iconic Michael Myers as an almost otherworldly force of evil, stalking and killing babysitters in otherwise peaceful Haddonfield. It featured a bare-bones plot, a simple, haunting musical score composed by Carpenter himself, some truly nerve-wracking editing and cinematography, and it spawned a deluge of sequels, prequels, rip-offs, and homages. There’d be no Scream films without Halloween, no Friday the 13th franchise, no “rules for surviving a horror film.” Cinema—suspense and horror cinema in particular—would be a lot poorer without Mr. Carpenter’s massive influence.

Halloween is now hailed as a masterpiece of horror, consistently showing up on “Best Horror Films” lists, but it has also sparked controversy over alleged misogyny and sadism. In this film, some critics argued, young women are punished for having premarital sex—all but the chaste “Final Girl.” Michael Myers, they claimed, was an agent of conservative morality, and viewers indulged misogynistic, sadistic pleasures by identifying with him. But that approach is misguided. Myers is an agent of pure, anti-social evil, and the characters who are killed are the ones who fail to be vigilant. The film does not invite us to identify with Myers—it invites us to identify with his victims. The pleasure of watching Halloween is the peculiar pleasure of vicarious immersion into a world torn apart by horror.

I spoke to Mr. Carpenter as research for my book, and the rest of this blog post is a transcription of that conversation.

Mathias Clasen: How do you feel about what critics have said about Halloween? Especially the Final Girl stuff, the sexually conservative ideological structure that is supposed to be in your work?

John Carpenter: This all comes from one guy, a Canadian reviewer, Robin Wood. He was running a film festival around the time, I think it was American Nightmares. It was his idea that Halloween was revenge of the repressed. That’s what he called it. I don’t agree with that. At all.

MC: Yeah, I don’t see it either. The way I see it, the character who is not busy having sex is being aware of her surroundings, and that’s why she survives.

JC: Exactly right, that’s exactly it.

MC: So, picking up on that, do you see Halloween as an upbeat or a downbeat film?

John Carpenter (2010). Photo by Nathan Hartley Maas. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

John Carpenter (2010). Photo by Nathan Hartley Maas. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.JC: Upbeat or downbeat film, wow. You know, that’s a really tough one to say, I don’t know if I see it as either. It’s just a little scary tale to be told around a campfire like so many movies are. And that’s about all it is, it’s not that much more than that.

MC: On the one hand it seems to say “you’re not safe,” you know, “anywhere you go a creepy guy in a mask could be there waiting for you,” but on the other hand [it says] “if you’re aware, you’ll go through the night.”

JC: That’s right, you’ll live through the night, which is always an important message. Well, I think more than just a creepy guy with a mask, I think Halloween says “evil does exist”. And if you’re aware, you can survive. Let’s put it that way.

MC: So what do you think about evil? I mean social psychologists, for example, don’t believe there is such a thing.

JC: Sure there is. Of course there is. The lack of empathy. That’s simple. It really exists, there is a lack of empathy. Some human beings don’t have it at all. At all.

MC: Including Mike Myers.

JC: Well, he’s not really human.

MC: [Some critics] talked about the use of optical point of view in slasher films, and how that supposedly leads to identification, and [they focused on] the famous first shot in Halloween where we see things through the eyes of young Mike Myers. My take on it is that you’re saving the big surprise of who the culprit is.

JC: That’s exactly right, it’s a way of disguising who the killer is.

MC: So no invitation to empathize with…

JC: No, God no. The whole movie is about surviving horror, it’s not about identifying with horror. No. It’s “watch out!”

MC: What do you think about the function of horror, why do people seek out this stuff?

JC: Well, catharsis, I guess, is one of the ancient explanations. It’s a way of coping, a way for all of us to cope with the darkness. And it has become a thrill ride type of thing, so it’s all of those. It’s a ritual, a societal ritual. “Let’s go to a horror movie.” Especially if you have a girl with you, you can cuddle, which is always fun.

MC: That’s true, the so-called “snuggle theory,” that you slip the arm around the girl screaming for dear life and show her that you can master it.

JC: That’s right, that’s part of it.

MC: When was the last time you were really, truly afraid in a movie theater?

JC: Well, I don’t go to the movie theaters anymore because of cell phones and such, but we’re all afraid of the same things. So I’m afraid of the exact same thing as you are. There’s no difference. And human beings are all afraid of the same things, that’s one of the reasons that the genre is so profound, so universal, so worldwide. You know, there are different ideas of humor. People laugh at different things in different cultures. But you see this giant monster walking around and we all respond the same way: “Holy shit! Get me out of here!”

MC: Yeah, I agree with that, that’s one of the key claims in my book—that people tend to be afraid of the same things no matter where they come from. It’s usually the dark, and heights, and spiders, and snakes, and…

JC: Yeah, you got it all, there’s a list, you know, loss of identity, disfigurement, loss of a loved one, I mean, it goes on and on.

MC: So those are some of the same evolved, hardwired buttons that horror pushes?

JC: Yes, that’s exactly it. It’s hardwired. All of this is part of our survival techniques developed over years of evolution. And it’s just our way of surviving this thing called life. We need to survive it, so we developed techniques.

MC: And you think horror films, horror literature can help us refine or calibrate those techniques?

JC: Yeah, take a dip in horror and I think it, you know, if nothing else, it reinforces what you already know. It reinforces what your instincts are.

The interview was kindly transcribed by Charlotte Biermann Bentsen.

Featured image credit: Photo of graveyard. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Horror films reinforce our fear instincts: Q&A with John Carpenter appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers