Oxford University Press's Blog, page 307

October 29, 2017

Public lands, private profit

In August, Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke gave President Trump his review of all the large national monuments declared since 1996, a review required by an executive order signed last April. Zinke traveled to many monuments, speaking to a few local groups but mostly to politicians and energy executives. Ultimately, he recommended reductions to four national monuments including Bears Ears, in southern Utah, whose territory he believes should be cut from 1.35 million acres to 160,000 acres. Along the way, Zinke and allies ignored and belittled Native American activists.

The Trump Presidency began within, donating his first quarter salary, just over $78,000, to the National Park Service (NPS). Meanwhile, his proposed budget aimed to reduce the Department of the Interior’s funding by 12%, despite a deferred maintenance backlog of $25 billion for the NPS alone. Simultaneously, Congress used the Congressional Review Act to eliminate the Bureau of Land Management’s new planning system, known as Planning 2.0. By signing the repeal, Trump keeps in place badly outdated planning procedures under the guise of local control.

Although no signature legislation has passed, President Trump and his congressional allies have already made several consequential changes, notably in the ways that the administration is undermining the public lands system. These changes often misconstrue the lands’ historical purpose—to serve the public interest—and roll back victories for science and democracy that conservationists won over the past half-century.

Americans have long contended over public lands, as we should. We all share in their ownership. And that is a historical oddity, because perhaps nowhere in the world do people love private property as much as in the United States.

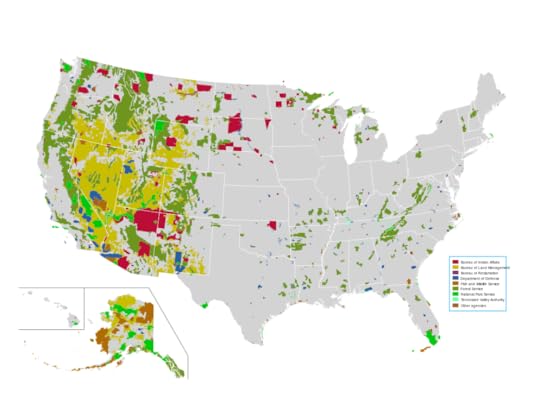

Since the late nineteenth century, though, the government’s legislative and executive branches have set aside millions of acres to be held outside the private property regime. Since Congress declared the first national park (Yellowstone) in 1872, the national government has sought to set aside lands as permanently belonging to the public. Today, the nation’s public land amounts to well over 600,000,000 acres nationally, or roughly 27% of the United States. Nevertheless, there has long been tension over just what is meant by “public good.”

Map of the US federal lands in 2005, a system that includes more than a quarter of the US land mass under different protective statuses, by National Atlas of the United States. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Map of the US federal lands in 2005, a system that includes more than a quarter of the US land mass under different protective statuses, by National Atlas of the United States. Public domain via Wikimedia CommonsThroughout their histories, public land agencies such as the Bureau of Land Management have relied on public experts to manage resources. But special interest groups long pursued private goals, seeking to maximize commodity production. For many decades, for example, ranchers practically ran the BLM (at times even supplementing federal salaries). Until the 1960s, federal land agencies administered their lands with little accountability to the broader public to whom the land purportedly belonged. Beginning with the Wilderness Act in 1964 and the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970, Congress empowered the public to weigh in on planning and management actions. Eventually, public hearings became standard and required, an opening that allowed broader participation and different values to influence public land policy.

This caused a sea-change in administering the public lands. Scientists began questioning a management system that relied predominantly on economic considerations. Ecological data showed that eliminating such predators as wolves and grizzlies, long a tool in the federal toolkit, turned out to have cascading consequences throughout ecosystems; fire suppression on national forests transformed open forests into tangled tinderboxes and threatened future landscapes. In the 1970s, Congress told federal land agencies to rely more on science in a series of new laws (e.g., Endangered Species Act of 1973, National Forest Management Act of 1976, etc.) and provided administrative agencies with clearer direction. These laws relied on novel ecological data and methodologies while renewing democratic processes.

These new laws have greatly contributed to conservation successes. The National Wilderness Preservation System has grown from nine million acres to nearly 110 million. Some of the worst clearcutting and overgrazing has been stopped. Even crowded national parks are taking steps to minimize tourist traffic. Despite these positive changes, new environmental laws have also slowed down planning and implementation, frustrating resource users, land managers, and environmentalists. Some agencies suffer from low morale, including lack of clarity about missions. When the BLM focused almost exclusively on administering the range for livestock production, their mission was clear; now, managing those same ranges for wilderness, recreation, restoration, wild horses, livestock, and oil and gas can lead to an amorphous and dissipating sense of purpose. Traditional constituents have lost their preeminent position. For communities whose identities—and paychecks—once depended on logging national forests or grazing public lands, the environmental revolution of the last 50 years has seemingly reversed their fortunes.

That is where the Trump Administration steps in dangerously: to appeal to a sense of loss and to promise a return to traditional dominance. His “Make America Great Again” is explicitly a historical promise, if also a deeply vague one.

The Bundy et al. armed takeover of Oregon’s Malheur National Wildlife Refuge last year (briefly) enacted a revanchist fantasy that “returned” government land to its rightful owners: white ranchers. This history is problematic and selective, writing out the Paiute, for instance, and it willfully misunderstands the long history of the federal presence in the region. But the Bundys gave us a grim glimpse on public land what can be done when groups organize to serve a mythic past, a prospect that extends beyond the public lands.

Reducing funding to national parks; opening more public lands to oil and gas development (a boom facilitated by the Obama Administration but poised to accelerate now); rolling back the size and purpose of national monuments; bypassing planning reforms for national ranges—all of these trends skew the public lands system and divert it from its historical trajectory of the last half-century. Environmental laws enacted under overwhelming bipartisan majorities in the 1960s and 1970s (the Wilderness Act had one “no” vote in the House of Representatives; the Endangered Species Act passed the Senate unanimously) helped reverse ecological degradation and promote democratic processes.

These lands embody the public trust. Any administration that works to maximize profit and to minimize public input for them threatens to reinstate the excesses and problems of past decades.

Featured image credit: Cedar Mesa Valley of the Gods by Bob Wick , Bureau of Land Management. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Public lands, private profit appeared first on OUPblog.

Constitutional resistance to executive power

In a blog post following the election of Donald J. Trump, Professor Mark A. Graber examined the new president’s cavalier attitude toward constitutional norms and predicted that, “[o]ver the next few years, Americans and constitutional observers are likely to learn whether the Framers in 1787 did indeed contrive ‘a machine that would go of itself’ or whether human intervention is necessary both to operate the constitution and compensate for systemic constitutional failures.”

Nine months into the Trump administration (at this writing), the machine continues to go: the structural checks and balances that flow from a federal government of separated powers have worked to allow challenges to, and even thwart, some of the president’s policy moves.

Consider, for instance, the raft of litigation in response to Trump’s executive orders limiting immigration from specified countries, with federal judges considering the weight that should be accorded the origins and consequences of these orders in determining whether they comport with our commitments to religious freedom and equal protection of the laws. Or look at the overwhelming bipartisan support in Congress for a law proscribing the president’s authority to influence sanctions against Russia for that country’s interference in the 2016 presidential election and hostile action in Crimea.

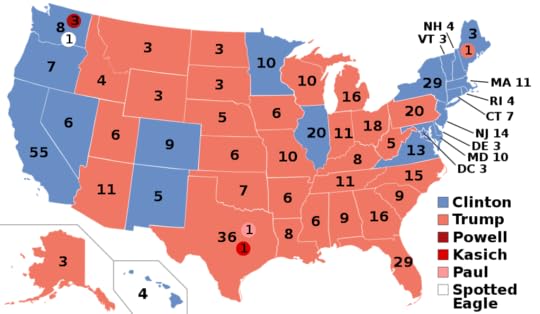

2016 US presidential election results by Seb az86556. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

2016 US presidential election results by Seb az86556. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.These examples confirm the vitality of the fail-safe mechanisms the framers embedded in the machine. At the same time, there are limits to what the federal courts and Congress can do about a president who displays such little respect for constitutional norms—and, indeed, the rule of law. The courts, after all, can address only the cases brought before them—and they rightly continue to show appropriate deference to the executive’s policy expertise in many areas. And the majority in both houses of Congress, owing to a stark partisan divide, has acquiesced to executive actions it surely would not have tolerated were the President from the other party.

But our constitutional scheme contains another mechanism available to citizens who seek to resist the questionable exercise of executive power: the states. State courts and state governments are positioned in our federalist system to act as counterpoints to both executive overreaching and executive withdrawal. In respect to the former, consider Lunn v. Commonwealth, in which the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that federal requests of state officers to detain individuals pending removal proceedings, absent legitimate grounds for arrest, find no support in any state or federal law. In respect to the latter, consider the efforts of several states, following the president’s decision to withdraw the United States from the Paris climate accord, to continue to address the causes and consequences of global climate change.

Aside from purely symbolic action regarding matters of national security and foreign policy, state government resistance to particular executive policies will be a function of the local and regional interests affected by those policies. For state courts, resistance will be a function of the reach of local constitutional and statutory law, which may be more protective of individual rights and provide for more expansive regulatory safeguards than federal law. If nothing else, state legislative chambers and courtrooms—like their federal counterparts—are fora in which the efficacy of the chief executive’s policy preferences can be raised and debated. Such actions of themselves serve a valuable educational role, and they may lead to legislation or judicial rulings that signal a state’s lack of support for certain policies—and to the hope, should other states send similar signals, that the force of such resistance will not be denied.

Featured Image Credit: “City Lights of the United States” by NASA Earth Observatory. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Constitutional resistance to executive power appeared first on OUPblog.

How welcoming practices and positive school climate can prevent bullying

Sometimes the most effective tools to reduce bullying in schools are as simple as a sincere hello.

What happens when a student or parent first walks in to a new school? What welcoming practices occur during the initial registration process, when parents first complete a set of forms, when they hear the first hello, or when students are first introduced to teachers and classmates? Are students and parents greeted with warmth, guidance, and understanding, or is it a cold administrative process?

We know that the welcoming process is vitally important to vulnerable groups who are often highly mobile. Vulnerable groups such as homeless students, students in foster care, or group homes, students who have been involved in the juvenile justice system, LGBTQ students, military-connected students, and documented and undocumented students from immigrant families are at a higher risk for bullying if schools don’t welcome them with a process that acknowledges their culture, demonstrates their value as part of the school community, and celebrates their diversity in a positive way. How students are welcomed into new schools can affect their feelings of connectedness, their relationships with students and teachers, attendance, whether they drift into risk-taking peer groups, if they are bullied, and even their academic trajectory. Efforts as straight-forward as training student ambassadors to welcome new students before they enter the school make a world of difference.

Many schools naturally have a welcoming environment due to their philosophy, mission, and staff, and there is much to be learned from them. With the Every Student Succeeds Act, passed in 2015 by President Obama, now urging states to integrate school climate metrics into their accountability and survey systems, using welcoming practices and other strategies to create a positive school climate as a way to prevent bullying victimization has become a high priority for our nation’s schools.

Kid, children by Tina Floersch. Public domain via Unsplash.

Kid, children by Tina Floersch. Public domain via Unsplash.There are challenges associated with a more data-driven approach to school programs, however. Given how many schools there are in each state (California alone has approximately 10,000 schools) how can we ensure our nation’s schools all have high-quality welcoming, school climate, social-emotional learning and bullying prevention approaches that avoid a one-size-fits-all approach? Each school has its own academic profile, demographics, culture, climate, types of bullying, and ways of welcoming. Historically, data collection in schools has been used to reinforce a high-stakes atmosphere, and punish schools who underperform. This approach of using data needs to be changed so that data is seen as a democratic form of voice. This way student, teacher, and parent voices are heard and shared at each school. When this is achieved schools can adopt both a ground-up and top-down approach to implementation.

If states generate accurate and meaningful metrics that each school, district, region, and state can jointly use, schools will be liberated to learn from other schools that have created optimal and model environments. A specific school will know exactly the types of bullying problems they are facing and can arrive at potential solutions based on the voices of the students, teachers, and parents from their school. A school may discover they have a significant problem of bullying through social exclusion and create responses specifically focused on the lunch area and during recess. Another school from the same neighborhood and community may identify problems around fighting in the boy’s bathroom which would require a different approach entirely. Having regional data also allows schools to find and learn from others similar to them that have been successful at creating welcoming, positive climates. Certain evidence-based programs may work better for some schools and regions but not others. An excellent regional monitoring system that gauges school climate and bullying, such as the one used in Israel, provides schools with a local data-driven, and locally led way to strategize about specific problems in ways that make sense for each school. This approach, however, also allows each school to compare progress with local schools and with schools across the state.

If we are serious about preventing bullying, improving school climate, welcoming students, and giving students social-emotional skills, then we need a data infrastructure and a process that allows schools to use the information to improve. Each school will be slightly different, with different solutions that change year to year based on changing demographics, teaching staff, and community needs. Students, parents, and teachers will become participants in the change process rather than objects of the change process. Their ideas, solutions, and strategies that work will be included in the school improvement process. There are many ways to welcome new families, many ways to celebrate our students and teachers, and myriad ways to prevent bullying from occurring in schools. Putting students’ and teachers’ voices at the center of the process can build positive climates to prevent bullying nationwide.

Featured image credit: school lockers by lindahicks. Public domain via pixabay.

The post How welcoming practices and positive school climate can prevent bullying appeared first on OUPblog.

October 28, 2017

Open Access: Q&A with GigaScience executive editor, Scott Edmunds

The 10th Annual International Open Access Week is marked as 23-29 October 2017. This year, the theme is “Open In Order To…” which is “an invitation to answer the question of what concrete benefits can be realized by making scholarly outputs openly available?” To celebrate Open Access Week, we talked to Scott Edmunds, Executive Editor for GigaScience.

Scott, from an editor’s perspective, what are the pros and cons of open access research?

From an editors perspective it means our efforts are maximized because everyone can access the end products of our efforts. I can’t see any negatives as what we are supposed to be doing is assessing and disseminating academic research, and to do this properly the process should be transparent, accountable and not hidden away.

What would you say is the number one benefit of the open access model for researchers?

Everyone can access and re-utilize their work for the common good, not just a wealthy elite with expensive library subscriptions but the global research community, people outside of traditional academia, the citizen tax-payers that funded the research, and even machines. As in this data-driven world, machine readability is important for data-mining and cross disciplinary analyses to squeeze every last bit of insight out of your research.

In what ways can editors and authors support open access research?

Only publish and work with open access journals. Use pre-print servers and archive your papers in institutional repositories. When given the choice in licensing your work always choose true Budapest Open Access Initiative defined licenses, i.e. creative commons CC-BY.

Why did you carry out this research, as if wanting people to read and re-use your work is important then it needs to be open and accessible?

Why do you believe the publishing industry seen an increase in the number of open access journals in recent years?

How we handle digital content has taken a while to evolve since the rise of the world wide web, but socially and in terms of policy its becoming the norm, with the biggest driver being funder mandates.

As an editor of an open access journal, what do you find is your greatest challenge?

The infrastructure we have is not brilliantly suited for the digital, connected era we now live and work in. Open licenses reduce some of the friction, but the tools we use to read, write, review and disseminate our content are still clunky and need improvement.

What would you tell an author who is hesitant about paying to submit their research to an open access journal?

Why did you carry out this research, as if wanting people to read and re-use your work is important then it needs to be open and accessible? In the 21st century, putting up unnecessary barriers to your work limits your relevance and voice.

Featured image credit: “Sign Open Neon Business Electric Electrical” by @Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Open Access: Q&A with GigaScience executive editor, Scott Edmunds appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know quantum physics? [quiz]

Quantum physics is one of the most important intellectual movements in human history. Today, quantum physics is everywhere: it explains how our computers work, how lasers transmit information across the Internet, and allows scientists to predict accurately the behavior of nearly every particle in nature. Its application continues to be fundamental in the investigation of the most expansive questions related to our world and the universe.

In Quantum Physics: What Everyone Needs to Know®, quantum physicist Michael G. Raymer distills the basic principles of such an abstract field, and addresses the many ways quantum physics is a key factor in today’s science and beyond. Take this quiz to find out how much you know about the field of quantum physics!

Quiz background image: 3 trajectories guided by the wave function by Alexandre Gondran. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: “Quantum Mechanics” by geralt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post How well do you know quantum physics? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

When rivers die – and are reborn

Most of the great cities of the world were built on rivers, for rivers have provided the water, the agricultural fertility, and the transport links essential for most great civilizations. This presents a series of puzzles. Why have the people who depend on those rivers so often poisoned their own water sources? How much pollution is enough to kill a river? And what is needed to bring one back to life?

I didn’t think much about this growing up as a child in London in the 1960s. All I knew or thought I knew, was that the Thames was toxic. If we fell into the river we would have to go to hospital and be subjected to a “stomach pump” to extract the dirty water. We children imagined a kind of reverse bicycle pump stuffed down our throats, which is more or less how it works in reality.

As I grew up and began to travel, I saw, sailed on, walked along, and read about many more waterways, from streams and canals to the great rivers of the world. Some – the Nile, the Zambezi, the Essequibo, the Mekong – were remarkably clean, because of the absence of large cities along most of their lengths. Others, like the Rhine and the Seine, were so-so. And still others, particularly the waterways of densely populated Asian cities undergoing their high-speed industrial revolutions, were filthy. The Malaysian writer Rehman Rashid’s description of the Sungei Segget as a “rank, black, stagnant, noisome ditch, filling the town centre of Johor Baru with the aroma of raw sewage and rotting carcasses” reminded me of Charles Dickens’s description in Hard Times of a fictional town in the north of England that was probably Preston: “Down upon the river that was black and thick with dye, some Coketown boys who were at large – a rare sight there – rowed a crazy boat, which made a spumous track upon the water as it jogged along, while every dip of an oar stirred up vile smells.”

Spumous? If you’re looking for spumous, I can recommend the Yamuna River below the Okhla barrage in Delhi, after the city and the farmers around it have taken most of the clean water for irrigation and drinking and replaced it with a mixture of industrial waste and the untreated sewage of one of the world’s largest cities. At dawn, the great mounds of white foam thrown up by the barrage are tinged with pink as they float gently across the oily, black surface of a holy river once celebrated in ancient Indian literature as a paradise of turtles, birds, fish, deer and the gopis or female cowherds who tended to the playful god Krishna. So disgusting is this water that the latest official measurements I could find from Okhla show it to contain half a million times the number of faecal bacteria allowed under the Indian standard for bathing water.

River ganga dusk by Surender Ranga. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

River ganga dusk by Surender Ranga. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The abuse of the Yamuna, and the Ganges or Ganga of which it is a major tributary, is particularly puzzling because both rivers are worshipped as goddesses by hundreds of millions of Hindus, and because they are so important as sources of water and fertile silt to the vast populations of north India, from the lower slopes of the western Himalayas all the way to Calcutta and Dhaka and the Bay of Bengal in the east.

Enter Narendra Modi, prime minister of India since 2014 and leader of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party. The Yamuna just below Delhi is already dead, but the Ganges itself, while gravely threatened by pollution and over-extraction of water, is very much alive. You can see fresh-water dolphins far up the river in Allahabad, Varanasi, and Patna.

Modi has made saving the Ganges one of his policy priorities, and he once told Barack Obama, then US president, that he wanted to rescue India’s great river just as the United States had restored the Chicago River. The cleaning of the tidal Thames in London – once devoid of all fish life – and of the Rhine in continental Europe are other examples to follow.

Modi seems to have the political will to save the Yamuna and the Ganges, and he would certainly win the backing of the majority of Indians for the improved sanitation and pollution control that will be necessary. There is money there too, including $1 billion from the World Bank in what would be among its largest ever projects.

Three years into Modi’s five-year mandate, however, surprisingly little has been achieved to restore India’s rivers. It looks as if I’ll have a long wait before I can jump into the Yamuna at Okhla and go for a swim without needing my stomach pumped afterwards.

Featured Image: “hindu-india-sun-worship-hinduism” by guaravaroraji0. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post When rivers die – and are reborn appeared first on OUPblog.

October 27, 2017

Disaggregation and the war on terror [excerpt]

The early years of the 21st century are marred by acts of violence and terrorism on a global scale. Over a decade later the world’s problems in dealing with international threats are unfortunately far from over. In this excerpt from Blood Year: The Unraveling of Western Counterterrorism, author David Kilcullen looks back on a time he was called upon to help develop a strategy for the Australian government in fighting this new global threat.

In October 2002 terrorists from al-Qaeda’s Southeast Asian affiliate, Jemaah Islamiyah, bombed two nightclubs on the Indonesian island of Bali. They murdered 202 people, including eighty-eight Australians, and injured another 209, many blinded or maimed for life by horrific burns. Bali was the first mass-casualty hit by al-Qaeda or its affiliates after 9/11, a wake-up call that showed the terrorist threat was very much alive and close to home. It spurred the Australian government into increased action on counterterrorism.

A small group of officers, led by the ambassador for counterterrorism, Les Luck, was selected from Australia’s key national security agencies, given access to all available intelligence, and tasked to conduct a strategic assessment of the threat. In early 2004, as an infantry lieutenant colonel with a professional background in guerrilla and unconventional warfare, several years’ experience training and advising indigenous forces, and a PhD that included fieldwork with insurgents and Islamic extremists in Southeast Asia, I was pulled out of a desk job at Army headquarters to join the team. Our efforts produced Transnational Terrorism: The Threat to Australia, the framework until 2011 for Australia’s counterterrorism strategy and for cooperation with regional partners and allies including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and New Zealand.

Looking at the threat in early 2004, we saw a pattern: the invasion of Afghanistan had scattered but not destroyed the original, hierarchical AQ structure that had existed before 9/11. Many of those fighting for AQ in Afghanistan in 2001 had been killed or captured, or had fled into Pakistan, Iran or Iraq. Osama bin Laden and his deputy, Ayman al-Zawahiri, were in hiding; Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (planner of 9/11 and mastermind of the Bali bombing) was in CIA custody at an undisclosed location. What was left of AQ’s senior leadership was no longer a supreme command or organizational headquarters, but a clearing house for information, money and expertise, a propaganda hub, and the inspiration for a far-flung assortment of local movements, most of which pre-dated AQ.

Image credit: Afghanistan air base by 12019. CC0 via Pixabay.

Image credit: Afghanistan air base by 12019. CC0 via Pixabay.Al-Qaeda’s “Centre of Gravity”—from which it drew its strength and freedom of action—was neither its numbers nor its combat capability (both of which were relatively small) but rather its ability to manipulate, mobilize and aggregate the effects of many diverse local groups across the world, none of which were natural allies to each other.

In this sense, AQ had much in common with traditional insurgent movements, which manipulate local, pre-existing grievances as a way to mobilize populations, creating a mass base of support for a relatively small force of fast-moving, lightly equipped guerrillas. These guerrillas work with numerically larger underground and auxiliary networks to target weak points such as government outposts, isolated police and military units, and poorly governed spaces. They might try to build “liberated” areas, forge coalitions of like minded allies into a popular front, or transition to a conventional war of movement and thereby overthrow the state. But unlike classical insurgents, who target one country or region, AQ was a worldwide movement with global goals. Thus, to succeed, bin Laden’s people had to inject themselves into others’ conflicts on a global scale, twist local grievances and exploit them for their own transnational ends. This meant that AQ’s critical requirement, and its greatest vulnerability, was its need to unify many disparate groups—in Somalia, Indonesia, Chechnya, Nigeria, Yemen, the Philippines or half-a-dozen other places. Take away its ability to aggregate the effects of such groups, and AQ’s threat would be hugely diminished, as would the risk of another 9/11. Bin Laden would be just one more extremist among many in Pakistan, not a global threat. He and the AQ leadership would become strategically irrelevant: we could kill or capture them later, at our leisure—or not.

Out of this emerged a view of al-Qaeda as a form of globalized insurgency, and a strategy known as “Disaggregation.” Writing for a military audience in late 2003, I laid it out like this:

Dozens of local movements, grievances and issues have been aggregated (through regional and global players) into a global jihad against the West. These regional and global players prey upon, link and exploit local actors and issues that are pre-existing. What makes the jihad so dangerous is its global nature. Without the … ability to aggregate dozens of conflicts into a broad movement, the global jihad ceases to exist. It becomes simply a series of disparate local conflicts that are capable of being solved by nation-states and can be addressed at the regional or national level without interference from global enemies such as Al Qa’eda … A strategy of Disaggregation would seek to dismantle, or break up, the links that allow the jihad to function as a global entity.

They say you should be careful what you wish for. In designing Disaggregation, our team was reacting against President Bush, who, through the invasion of Iraq, the “axis of evil” speech and statements like “Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists,” had (in our view) destabilized the greater Middle East and greatly inflated the danger of terrorism. The existing strategy had lumped together diverse threats, so that Washington ran the risk of creating new adversaries, and of fighting simultaneously enemies who could have been fought sequentially (or not at all). Practices instituted in the early years of the War on Terrorism, as a result of this “Aggregation” of threats, had proven strategically counterproductive and morally problematic.

Featured Image: Afghanistan by The US Army. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Disaggregation and the war on terror [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

Marketing-driven government (Part 2)

Current conceptions of marketing in government

When marketing is used in government, its impact is often limited because it is dogged by a short-term, fragmented approach influenced by political time cycles. Government marketing is often characterised by an overemphasis on broadcast communications, including digital platforms, to the exclusion of a more citizen-centric approach focused on listening, relationship building, and social networking. Within government the application of marketing principles is also limited by a number of structural barriers and practices that include a lack of cross department coordination, inappropriate budgetary allocation systems and a lack of adequate return on investment, cost benefit analysis, and value for money audit. These barriers are compounded by a chronic lack of marketing capacity and capability within many government organisations.

Marketing is also often perceived as a function that can be applied after policy and strategy has been set. It is viewed as a set of procedures dominated by communications planning that are applied to inform and motivate people to comply with whatever advice is being disseminated by government. Social marketing is often seen as a third order function behind policy development and strategy formulation. In many government departments, most activity labelled ‘Marketing’ is in reality smart communications, sometimes informed by citizen insight.

Stuck in the past

Marketing in government needs to catch up with the rest of marketing. Marketing in the commercial sector is not about persuading people to buy stuff they don’t want or need: it is about building relationships that are mutually beneficial and developing products and services that people want, and delivering them in ways that delight and enrich people’s lives. Marketing today is also about respect and responsiveness. If you want someone to spend some time even considering what you have to offer, you increasingly need their permission to do this. The days of aggressively assaulting people’s space and time with pushy promotions are disappearing fast. Now promotions need to be intrinsically valuable to people if they are to be effective. Marketing is focused on value creation, building brand loyalty, and aspiration. The principles of relationship marketing, permission-based marketing, and service dominant logic need to be used by those interested in advocating the wider integration of marketing in the governmental sector.

A majority of government marketing practice is stuck in the past using limiting principles and tools to analyse, develop, implement, and evaluate social policy. This self-inflicted limitation, together with status quo bias in favour of existing social policy development processes and the antithesis held by some politicians and policy makers referred to earlier, equates to a powerful set of barriers to a more strategic application of a modern marketing principles within the government sector.

Developing marketing capacity and capability across government

What is required if marketing is to be fully utilized within government is the need for a managerial cultural shift towards a more citizen-informed and engaged approach and one that seeks to apply marketing principles to the development of all social policy and strategy. This means positioning marketing directors in posts with authority and the development of more marketing and market research expertise in all government departments. Governments could assist this process by developing professional training programmes and establishing centres of good practice and research excellence.

“Annual budget allocations based on historial precedent fuel short-term thinking and end of year budget dumping”

One of the most important components of a strategic approach to applying marketing within government is the allocation and management of marketing and communication budgets. In government departments the control of marketing budgets is often split between marketing and communication departments and policy leads. Policy leads often have power to decide on what marketing budgets are used for. This lack of control by marketing managers in government over budgets can work against a strategic and consistent approach to delivery. Annual budget allocations based on historical precedent also fuel short-term thinking and end of year budget dumping. If a more strategic approach was applied to government marketing programmes, budgets would be set up and measured in terms of return of investment, cost benefit analysis, and value for money audit. Strategically, marketing budgets from across different government departments should also be able to be pooled or transferred as often social issues and challenges cut across several departments responsibilities.

A strategic approach to commissioning and using market research is also a key component that needs to improve in much government marketing. Often individual departments or teams within a single department will commission research to support specific programmes. Often this research and the analysis performed on it is not made available to other teams who may find it helpful. A more joined up and strategic approach to commissioning marketing research should be a top priority when developing an overall strategic approach. A strategic plan to gather and disseminate target audience and stakeholder research across departments should also be developed.

Paper Dolls by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 Creative Commons via Pixabay.

Paper Dolls by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 Creative Commons via Pixabay.Conclusion

Marketing will inevitably become more central in government policy making, strategy formulation, and operational programme delivery. This shift is being driven by the shift in power that is happening all over the world related to the growing wealth, improved education, and a growing expectation horizon amongst more and more of the world’s citizens. This change will demand a response from governments, many of which continue to operate an elitist top down approach to policy formulation and social programme delivery.

A more citizen-focused approach will be necessary to meet citizen’s’ aspirations and expectations of government and its agencies. This shift in approach will however be delayed as long as governments continue to ignore, misinterpret, and misapply marketing. Governments should be encouraged and aided by professional marketing organisations academics and marketing practitioners to establish systems and policy development environments where marketing can be comprehensively applied to enrich social programmes.

The job of government is to support and enable people to live great lives; to encourage and regulate markets that create well-being, foster civic coalitions that promote social good, and protect and support citizens. It follows then that governments need to be able to understand and engage citizens to optimally deliver these roles. Marketing is the best policy tool to assist governments in achieving this.

Featured image credit: Westminster Bridge by Atanas Chankov. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Marketing-driven government (Part 2) appeared first on OUPblog.

Hop heads and locaholics: excerpt from Beeronomics

Beer drinkers across the United States observe the National American Beer Day annually on 27 October. Over the last few decades IPAs, craft beer, and microbreweries have taken over the American beer market and continue their steady growth.

The following extract from Johan Swinnen and Devin Briski’s Beeronomics: How Beer Explains the World discusses some of the strategies of the American craft beer movement.

Northern California has long hosted many a tour of intoxicants: first, through the fertile Sonoma and Napa county vineyards famous for deep red Zinfandels, and then further along to California’s “Emerald Triangle” of Humboldt, Mendocino, and Trinity counties. Microbreweries and brewpubs are relative newcomers on this terrain, though they’ve quickly established their niche among the mannered locavores’ less coherent cousins—the locaholics.

As the story goes, India pale ale (IPA) was born of the imperial age, at the dawn of globalization, when English beer producers figured out that beer would last longer on boat rides if they increased the amount of hops and the alcohol content in their pale ales. How ironic, then, that what started as a preservation strategy has become a regional hallmark for many breweries in northern Californian. It is in this region that “hop heads”—Sierra Nevada brewery’s affectionate term for drinkers chasing ever-higher IBU (international bitterness unit) levels—get their back-of-the-tongue fix. Picturesque coastal highways weave through vineyards while towns offer visitors the opportunity for a lineup of West Coast IPAs so strong they’ve become a style of their own. With recent growth and acquisition by Heineken, Lagunitas’ IPA has gained national attention. Local visitors can enjoy increased access to smaller release batches of its IPA Maximus and Hop Stoopid brews. This is a brewery that considers their 47 IBU Dogtown brew to be the standalone pale ale. For comparison, Budweiser has an IBU of 7.

Anchor Brewing bar by Binksternet. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Anchor Brewing bar by Binksternet. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.But kingpin of the region is undoubtedly Sierra Nevada, singlehandedly making its hometown of Chico a tourist destination and leading the way nationally with its double IPA Torpedo—the top-selling IPA in the United States, and the product of founder Ken Grossman’s wonkiness, utilizing a torpedo machine to double the bitter flavor. The national bestseller is sold locally alongside an experimental floral IPA with rose extract added to the aromatic hops, only slightly less bitter than the brewery’s notorious Hoptimum. These styles offer a visceral departure from the light lagers that American macrobreweries have been peddling in conjunction with the NFL for so long. These days, flagship brews are almost overwhelmingly top-fermented ales, and are frequently IPAs—diverse brews with dark, complex flavors and high alcohol content. And they’re more expensive—a six-pack of Lagunitas costs about the same as a twelvepack of Bud Light. And they’ve been a runaway success. The American domestic market share for craft beer has been increasing steadily since the mid-1980s. But it took the Great Recession in 2008 to offer a first indication that California crafts were here to stay. Sales of the craft sector climbed from $5.7 million in 2007 to $12 million in 2012. This growth happened during a period when the beer market continued to shrink and sales for imported beers like Heineken and Stella Artois took a nosedive. During this span of time, sales of Sierra Nevada increased 23% and Lagunitas more than tripled their output.

Now, the million dollar question surrounding the future of American beer is how, exactly, microbreweries will manage to turn their significant size constraints into their biggest competitive advantage.

Nestled at the bottom of Potrero Hill, positioned with a full view of the famous harbor for which the city is named, stands Anchor Brewery. This is one of six locations the brewery has occupied in recorded history, all as a San Francisco institution embodying the weight of its name.

Founded in 1896, Anchor is the only brewery to continue brewing San Francisco’s regional “steam beer.” Though the exact origins of steam beer are somewhat a mystery, the style may refer to the nineteenth century practice of lagering vats on roofs so the city’s famous nighttime fog would cool them, creating a steam-like effect. The amber beer is brewed using lager yeast while fermenting in warmer ale-like temperatures. Anchor Brewery revived the steam beer for local consumption after prohibition. The brewery was shut down in 1959, sold and reopened in 1960, then sold again in 1965 because of struggles with finances. The third time was the charm: none other than Fritz Maytag, heir to the household appliance fortune, bought a 51% controlling share in the brewery within a few hours of visiting. Maytag is something of a spiritual godfather to the craft beer movement, and Anchor is considered the “first craft brewery.”

His vision was radical amid a culture resistant to change. The vanguard for small breweries at that time was the Brewers Association of America (BAA), founded during World War II by Bill O’Shea. In 1940, there were 684 breweries producing 54.9 million barrels of beer a year. When Maytag bought Anchor, the number of breweries had fallen to 197 producing double that amount of beer. By 1980, there were only 101 breweries but production had nearly doubled again, to 188.1 million barrels—the top five breweries produced more than three-quarters of that. Americans were drinking more beer than ever, but this beer was coming from a falling number of increasingly large-capacity macrobreweries.

Featured image credit: beer garden glass mug by Alexas_Fotos. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Hop heads and locaholics: excerpt from Beeronomics appeared first on OUPblog.

October 26, 2017

Harry Potter at the British Library: Challenges, Innovations, and Magic

Last Friday the Harry Potter: A History of Magic exhibition opened at the British Library. It is a much anticipated showcase of Harry Potter artefacts, including many from the vaults of Bloomsbury and J.K. Rowling herself. It also offers a fantastic chance to see some of the British Library’s most rare, historic, and difficult-to-display items.

We visited the British Library to talk to co-curator Tanya Kirk about the challenges of putting on the exhibition, the pioneering elements of the project, and the magical experience of curating material about one of the world’s biggest book series.

Challenges

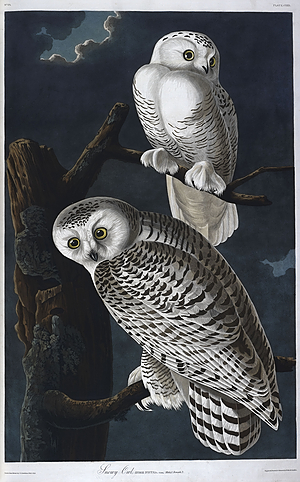

The exhibition involves a number of artefacts that have never been on display before because they’re so difficult to handle. One of the books in the exhibition is John James Audubon’s The Birds of America, featuring illustrations of every native bird in America, drawn at full size. This means the book is the size of the largest bird included – 3 ¼ feet (1m) tall. Tanya explained that it can’t often be displayed because it takes four people to lift it. “We had to have a special case made for it, because it didn’t fit in any of our other cases.”

Another challenging piece is a huge celestial globe, dating from 1693, which depicts the constellations. “It didn’t go through many of the doors,” Tanya said. “You have to plan the route very far ahead of time; measure all the doorways.”

One of the biggest challenges for the curators was working on an exhibition that will have to travel around the world – it will be opening in New York in October 2018.

“We’ve done touring exhibitions in the UK,” Tanya said, “but we’ve never done one abroad, and it’s a much bigger scale than what we’ve done before… At one point we were working on both exhibitions at the same time. It was a bit confusing actually!”

The collaborations in this exhibition were also a new challenge. The curators normally work alone on exhibitions, but this one involved collaborations with Bloomsbury, Google Arts and Culture, The Blair Partnership, and J.K. Rowling herself, as well as other museums and libraries. Julian Harrison, lead curator of the exhibition, said that attempts to borrow a garden gnome from The Garden Museum went particularly poorly, as they were initially offered a David Cameron gnome – however another gnome was eventually secured instead.

Innovations

Google and the British Library have a long standing relationship, but their partnership on this exhibition was a first. Suhair Khan of the Google Cultural Institute said that the collaboration was a natural one, as adding Augmented Reality to the exhibition would bring a magical element through technology. Google worked on digitising the celestial globe that features in the exhibition, allowing visitors to explore it.

Tanya said, “We obviously can’t spin the globe in the exhibition, and it’s beautiful all the way round, so it seemed like the perfect solution to be able to digitally spin it and see the other side.”

Another of the exhibition’s innovations is a sector-first partnership between 20 public libraries in the UK, who will present panels inspired by the exhibition alongside their own collections, highlighting regional connections to magical traditions and folklore, and allowing a full network of libraries from Edinburgh to Portsmouth to share ideas and inspire their patrons.

Magic

The exhibition has given the curators chance to explore the magic of the British Library collections in a whole new way, making new connections between artefacts and digging into uncharted depths within the archives.

“We have got far more books about magic than I thought we did,” Tanya said. “There was one hilarious day where I just found a whole rack of shelves that were all about magic in the basement here. There was just so much to choose from!”

The curators narrowed down a huge longlist of items to the most exciting and visually appealing, from a 3000 year old cauldron found in the Thames, to a black moon crystal belonging to a witch called Smelly Nelly.

“My favourite thing is the brief history of the Basilisk,” Tanya said. “It’s got this hilarious illustration, in which the Basilisk looks totally unfrightening, but the description of it is terrifying, so the two things don’t match at all.”

For a Harry Potter fan, working on the exhibition was a magical experience. One of Tanya’s highlights as a long-time fan of the series was going through Bloomsbury’s safe of papers, and Jim Kay’s illustrations; apparently there were “lots of geek opportunities”.

But probably the most magical part of the exhibition is learning about the ways in which the Harry Potter books are grounded in reality and history.

“I’ve learned that there’s a lot more historical basis in the Harry Potter books than I’d thought,” Tanya said. “So things like Nicolas Flamel, that we’ve got a big feature on, I don’t think I’d fully appreciated that he was a real person and that his wife was a real person. It was a bit mind-blowing actually, that it is all based on things and not just totally imaginary.”

The post Harry Potter at the British Library: Challenges, Innovations, and Magic appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers