Oxford University Press's Blog, page 306

October 31, 2017

Apparitions in the archives: haunted libraries in the UK

Following our look at haunted libraries in the US last year, this Halloween we turn our sights to the phantoms haunting the libraries and private collections of Britain. From a headless ghost, to numerous abnormalities surrounding a vast collection of magical literature from a late ghost hunter, here are some stories around apparitions that have been glimpsed among the stacks – you can choose whether or not you believe them to be true….

St. John’s Library, University of Oxford

St. John’s College Library is thought to be haunted by the headless ghost of Archbishop William Laud, who was beheaded in 1645 following impeachment by the Long Parliament. Guide books perpetuate the myth of the ghost of Archbishop William Laud disturbing readers by kicking his head along the floor of the library. This is not something library staff have reported in living memory. However, there have been several occasions, some recent, others going back fifty years, where readers say they have heard sounds of footsteps advancing and retreating along the floor of the long reading room, which was built by Laud in the 17th Century and is known as the Laudian Library. These sounds have never been explained away by mundane causes such as problems with the heating. As the Deputy Librarian states, “we do know that Laud cared passionately about his library, and we like to think he has a friendly presence here.”

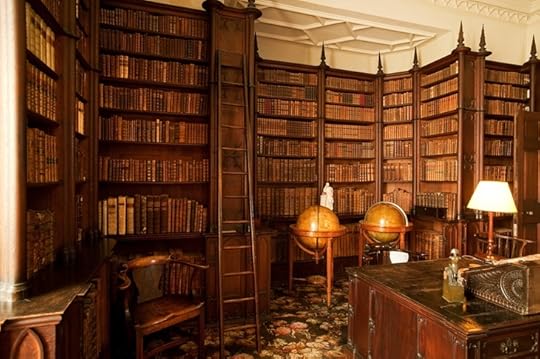

Felbrigg Hall Library by National Trust Images. Used with permission from National Trust.

Felbrigg Hall Library by National Trust Images. Used with permission from National Trust.Felbrigg Hall, Norfolk

Late Felbrigg Hall resident William Windham III was supposedly obsessed with books, and most ghost stories surrounding the estate link back to him and his personal library. Having died from injuries that he sustained after he heroically tried to save burning books from a fire at a friend’s personal library in London, his ghost is now believed to return to his own collection of books at Felbrigg in order to finally read the texts he didn’t get a chance to when he was alive. Staff and volunteers at the Hall report seeing William sitting at the library table, or relaxing in one of his reading chairs. According to at least one source, Windham’s ghost will only appear when a certain combination of books – presumably his favourites – are arranged on the library table.

The Harry Price Collection of Magical Literature, Senate House Library, London

Senate House Library, part of the University of London, is home to the Harry Price Collection. It is a collection of nearly 13,000 books, pamphlets, and periodical titles on all aspects of magic and the paranormal: from conjuring, to witchcraft and the occult, as well as prophecies, and spiritual phenomena such as ghosts and mediums. These were collected by and named after the leading paranormalist and psychical researcher Harry Price, who investigated cases of alleged hauntings during his lifetime. Ever since the books took residence on the eighth floor of Senate House, the library’s staff have reported strange activity, such as hearing the sound of loud laughter or whispering when no one else is around, and seeing floating books or even full-blown apparitions, including a mysterious cloaked figure and a glowing ‘Blue Lady.’

Raglan Castle, © Crown copyright (2017) Cadw, Welsh Government. Used with permission.

Raglan Castle, © Crown copyright (2017) Cadw, Welsh Government. Used with permission.The librarian ghost of Raglan Castle, Monmouthshire, Wales

As one of the last castles built in Wales, Raglan Castle was constructed between 1435 and 1525. Now a ruin, it is still a tourist attraction for visitors, who have reported catching glimpses of a ghost in bardic clothes. This figure has been described as beckoning to them from the vicinity of the wing of the castle that was once the library, and he is therefore thought to be the ghost of the castle’s librarian. During the Civil War, the librarian hid a collection valuable books and manuscripts in a secret tunnel beneath the castle –and it was lucky he did, for one of the first acts perpetrated by the enemy was the destruction of Raglan’s priceless library. Although it is not known when or where the librarian died, it is now thought that his spirit still watches over his hidden cache of literary treasures. The ghost was reportedly last seen in the summer of 2001, when a girl on a school trip came running from the castle, ashen-faced, insisting that she had seen him gesturing to her from a dimly lit corner.

Featured image credit: old books library by jarmoluk. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Apparitions in the archives: haunted libraries in the UK appeared first on OUPblog.

Doing the right thing: ethics in the Zombie Apocalypse [video]

From popular television shows like The Walking Dead and Game of Thrones to countless films, video games, and comics, stories of the Zombie Apocalypse have captivated modern audiences. With horror and fascination, we watch, read, and imagine the decimation of human society as we know it at the hands of the undead. As human civilization comes to an end with the Zombie Apocalypse, so does our existing code of ethics. In a world that now lacks order, our traditional conception of what is right and what is wrong is immediately thrown into question. We sat down with Greg Garrett, author of Living with the Living Dead, to discuss what ethics look like in the Zombie Apocalypse and how zombie films and literature force us to examine our modern system of values.

The man and the boy in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road have a running conversation about the ethics of the apocalypse. They agree that it’s wrong to consume their fellow human beings at any time, but the boy struggles with some of his father’s other guidance because in the course of their daily lives, they sometimes must make choices that seem to violate their code. When they take food or possessions they find on the road, the boy needs to be reassured that the people who own them are dead, that they are not simply stealing from others who are in need as they are. He even wants to hear that those owners would want them to take it. Yes, his father reassures him. They would. Just like we would want them to if the situation were reversed. Because we’re the good guys, and so were they. Still, the boy has a child’s unbending moral code and sense of fairness. “If you break little promises you’ll break big ones,” the boy reminds his father. “That’s what you said.” And on their journey, as they try simultaneously to find food and avoid becoming someone else’s meal, promises get broken.

When the man shoots a stranger who has threatened them, the boy is covered with his blood, a visual representation of the guilt that splashes across them both. The man is not a killer, but as he tells the boy, he will do whatever he has to keep him alive: “My job is to take care of you. I was appointed to do that by God. I will kill anyone who touches you.” This does not mean that the man has not also been affected by the killing; it simply means that he has made an ethical concession common to the Zombie Apocalypse. Just as Wichita in Zombieland says that she will do anything to keep her sister alive, many “good” characters in these zombie narratives do things they would never have done under less extreme circumstances. They compromise moral beliefs. They become more fearful, more calculating, more suspicious than they would wish, all in service of keeping themselves and those they love alive. Like the man, they have this mission, and within reason, they will do whatever it takes to survive. As Shane tells Rick in the “18 Miles Out” episode of season two of The Walking Dead, “You can’t just be the good guy and expect to live.” For many of the survivors of the Zombie Apocalypse the difficult choices arise out of that formulation: You can do the right thing, or what once was the right thing.

Or you can be dead.

The seventeenth-century British political philosopher Thomas Hobbes placed fear at the heart of his understanding of governments and of individual human behavior; for Hobbes, survival was the paramount human drive, and nothing could be worse than a world unraveled by war, the threat of violence, or, one supposes, an overrunning horde of the walking dead. In such a world, Hobbes wrote in his hugely influential work Leviathan, there can be “No Arts; No Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.” For those in The Road, The Walking Dead, 28 Days Later, and many other stories of the Zombie Apocalypse, this is an accurate accounting of the life they can expect: solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. Who would not be afraid in such a world? Continual fear, Hobbes concludes, is worse than all other calamities, and fear drives people to compromises and actions they might not otherwise take.

Featured image credit: “monster-spooky-horror-creepy-weird” by markusspiske. CC0 via

Pixabay.

The post Doing the right thing: ethics in the Zombie Apocalypse [video] appeared first on OUPblog.

J. S. Bach and the celebration of the Reformation

The figure most closely identified with the Protestant Reformation is, of course, Martin Luther. But after him probably comes Johann Sebastian Bach, who spent much of his musical career in the service of Luther’s church. As the world marks the 500th anniversary of the Reformation on 31 October 2017, we can remember that Bach and his contemporaries also took careful note of Reformation anniversaries, commemorating them in liturgy and music.

The year 1755 saw the two hundredth anniversary of the Peace of Augsburg, the 1555 agreement between Lutherans and the Holy Roman Emperor that put an end to confessional war, at least for a time. Bach, who died in 1750, did not live to see this commemoration, but he had his say–Leipzig churches heard a performance of his cantata “Erhalt uns, Herr, bei deinem Wort” BWV 126 (“Uphold us, Lord, by your word”), which takes one of Luther’s hymns as its starting point.

A couple of decades earlier, 1730, had seen the anniversary of the Augsburg Confession, the articles of Lutheran faith presented to the Holy Roman Emperor on 25 June 1530. The Augsburg Confession was a living document to Lutherans in Bach’s time, having been incorporated into the so-called Book of Concord that reconciled several strains of reformed Christianity. Bach, as a condition of his employment as a church musician in Leipzig, was examined on its theological content and had to sign a statement of his adherence to it.

The two hundredth anniversary in 1730 was observed in Leipzig with three days of religious celebration, a duration that put it on par with Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost–the principal feasts of the year. Bach performed a cantata on each of the three days: “Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied” BWV 190a (“Sing to the Lord a new song”), “Gott, man lobet dich in der Stille zu Sion” BWV 120b (“God you are praised in the stillness of Zion”), and “Wünschet Jerusalem Glück” BWV Anh. 4a (“Pray for the peace of Jerusalem”). Complete printed texts for these works survive but no musical sources, though some of the music is known from Bach’s use of it in other works. Another famous piece connected to the Augsburg Confession is Felix Mendelssohn’s Reformation Symphony, composed for the tercentennial in 1830 and quoting Luther’s best known hymn, “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott” (“A mighty fortress is our God”).

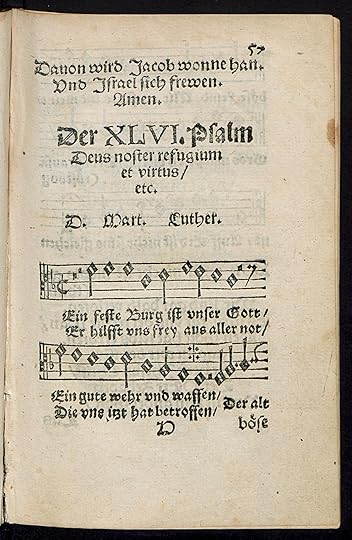

One of the earliest printings of Martin Luther’s hymn “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott.” Geistliche Lieder zu Wittemberg (Wittenberg: Josef Klug, 1544), CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 via Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin/Preussischer Kulturbesitz

One of the earliest printings of Martin Luther’s hymn “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott.” Geistliche Lieder zu Wittemberg (Wittenberg: Josef Klug, 1544), CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 via Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin/Preussischer KulturbesitzAnd 1717 marked the two hundredth anniversary of the most famous Reformation event of all–the appearance of Martin Luther’s Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences, an academic and theological position paper on the nature of repentance. The publication was elevated in popular church history to the status of a defining moment–Luther’s nailing of his 95 theses on the topic to the Wittenberg church door on 31 October 1517. Modern scholarship tends to understand this as being more like a posting on a bulletin board than the defiant act it sounds like today (there’s a book of popular history called The Reformation: How a Monk and a Mallet Changed the World), but the event took on a symbolic role as the beginning of the Lutheran Reformation.

In 1717, the anniversary year, Bach was in the last months of his employment at the court of Weimar, where the reigning Duke arranged elaborate commemorations. There is no indication that Bach composed any of the music marking the occasion, perhaps because relations with his employer were fraying. Bach had received an offer for a more prestigious and better-paying job elsewhere, and the tone of his demand for release led to his month-long imprisonment just a few days after the Reformation bicentennial.

Even outside the anniversary year, 31 October was celebrated as Reformation Day with a special liturgy throughout Lutheran lands beginning in 1667. Bach composed two cantatas for the occasion: “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott” BWV 80, possibly as early as 1724; and “Gott, der Herr, ist Sonn und Schild” BWV 79 (“God, the Lord, is sun and shield”) in 1725. A third cantata may also have been used: the first part of “Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes” BWV 76 (“The heavens tell the glory of God”), originally for a different time of the church year. It is not certain whether the Reformation Day use of this piece took place under Bach or after his lifetime. But whoever adapted it recognized a connection between its opening text from Psalm 19 (“The heavens tell the glory of God, and the skies proclaim the work of his hands; there is no speech nor language where their voice is not heard”) and a reading specified for the Reformation Day liturgy: the next verse of the same psalm: “Their sound has gone out into all lands; alleluia.”

The topic here—God’s word and its spread—was closely associated with the Reformation. In place of a gospel reading, the Reformation festival called for verses from the Book of Revelations, and they, too, take up this theme, “Then I saw an angel flying through the heavens, who had an eternal gospel to proclaim to those who live on earth, and all nations, tribes, languages and peoples.” To Lutherans, the annual celebration of Reformation Day represented this proclamation of God’s word anew, and texts on this topic were especially appropriate.

Bach’s cantata “Gott, der Herr, ist Sonn und Schild” BWV 79, composed in 1725, was intended for Reformation Day from the start. Its festive scoring with two horns and drums reflect the high solemnity of the feast, and its opening psalm chorus of praise is also fitting. One of its arias refers explicitly to God’s word, the familiar Reformation topic, and promises praise “even though the enemy rages hard against us.” This theme, the threat from enemies, appears several times in the cantata and relates to another Reformation Day topic: the vulnerability of the Lutheran Church, persecuted (in its view) by the Pope.

Bach’s other work for Reformation Day, “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott” BWV 80, might be his most famous cantata of all. It centers on Martin Luther’s hymn, whose four verses appear in the work in various musical guises. It, too, invokes the theme of protection from enemies. In fact this topic runs through the first three stanzas of the hymn, cast in military terms: a mighty fortress, weapons and arsenals, the field of battle, the defeat of the enemy. This theme is reflected musically in two movements whose agitated violin lines were a conventional eighteenth-century emblem of battle—a musical representation of the way Lutherans saw themselves in the world.

The military topic of the cantata’s music was reinforced by Bach’s eldest son Wilhelm Friedemann, who made Latin-language adaptations of two chorale movements, not surprisingly for the celebration of a military victory. He added trumpets and drums to his father’s compositions; these instruments, which never had anything to do with J. S. Bach’s Reformation Day cantata, were mistakenly incorporated back into “Ein feste Burg” in the nineteenth century, and this is the form in which the piece became famous.

Eighteenth-century Lutherans took such careful note of Reformation anniversaries in part because confessional tensions were still in the air even after two centuries. When Bach’s cantata 126 was heard in Leipzig at the 1755 commemoration of the Peace of Augsburg, its opening movement strikingly retained the original words of Martin Luther’s hymn: “Preserve us, Lord, by your word/And control the murderousness of Pope and Turk.” This was despite ecclesiastical instructions not to sing this hymn or “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott” at anniversary celebrations that year, in the hope that confessional strife might be kept to a minimum. But staunchly Lutheran Leipzig, ever wary, used Bach’s music to make a statement as it observed the anniversary of a central event of Luther’s Reformation.

Featured Image Credit: “Luther posting his 95 theses in 1517” by Ferdinand Willem Pauwels. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post J. S. Bach and the celebration of the Reformation appeared first on OUPblog.

October 30, 2017

From segregation to the Supreme Court: the life and work of Thurgood Marshall

Marshall (2017) recounts one of the most contentious Supreme Court cases in American history, represented by Thurgood Marshall, who would later serve as the first African American Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. Directed by Reginald Hudlin, with Chadwick Boseman playing the title role, the film establishes Marshall’s greatest legal triumph, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, in which the Court declared the laws allowing for separate but equal public facilities (including public schools) inherently unconstitutional. The case, handed down on 17 May 1954, signalled the end of racial segregation in America and the beginning of the American civil rights movement.

In 2013, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Editor in Chief of the Oxford African American Studies Center, spoke with Larry S. Gibson, Professor of Law at the University of Maryland, whose book Young Thurgood The Making of a Supreme Court Justice recounts the personal and public events that shaped Marshall’s work. Their conversation covered the inconsistent representations of Marshall’s life, and the events that placed Marshall on the path of civil advocacy.

HLG: Were there any surprises in your research on Marshall’s life—something that contradicted an impression you or your colleagues had held?

LG: Marshall was a much more serious young person and student than others have suggested. One reading the earlier biographies of Marshall would get the false impression that the young Marshall was not a serious student, was not exceptionally intelligent or industrious, and that his success can be attributed to his being a “late bloomer” who came awake in law school. Nothing could be further from the truth….

Thurgood Marshall by Yoichi R. Okamoto. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Thurgood Marshall by Yoichi R. Okamoto. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Marshall did not have repeated disciplinary problems in school, as some writers have claimed. He was not sent to the school basement and required to memorize sections of the US Constitution as punishment, as claimed. It is not true that Marshall went to college originally planning to be a dentist and that he changed his plans because he flunked chemistry. On his college application, also reproduced in the book, Marshall said clearly that he planned to be lawyer. Furthermore, the college transcript shows that he got a B and a C in chemistry. In college, Marshall was not repeatedly suspended for pranks. Much of the college lore is built around the telling, retelling, and exaggeration of an incident in which Marshall and one third of the sophomores at Lincoln University were suspended two weeks for hazing freshmen students. Marshall’s involvement was minor, as evidenced by his receiving the lightest penalty of the group.

HLG: Within a few days of becoming a lawyer, Marshall found himself involved in the aftermath of a lynching. Your book suggests that this was a turning point for Marshall. Is it safe to say that this incident in particular put him on the path to becoming a national civil rights advocate, rather than a lawyer running a local practice?

LG: In October 1933, one week after Thurgood Marshall was admitted to law practice; George Armwood was murdered by a mob in a horrific lynching on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. The next day, Thurgood Marshall wrote about the lynching in a letter to his former law school dean, Charles Houston. A few days later, Marshall joined Houston and eight other lawyers in the Maryland governor’s office protesting the lynching, demanding an investigation and legislative changes. Marshall became and remained an active and vocal anti-lynching advocate.

I often wonder what direction Marshall’s career would have taken had three specific incidents not occurred: the first of these being the Armwood lynching. The meeting in the governor’s office to protest the lynching brought Marshall back in touch with Houston. They might have otherwise gone their separate ways. The other fortuitous events were two conventions that happened to be held in Baltimore early in Marshall’s career: the 1934 national convention of the National Bar Association and the 1936 national convention of the NAACP. These two meetings in Marshall’s hometown brought him into direct contact with the nation’s leading black lawyers and civil rights advocates….

HLG: Though Marshall steadily built a reputation as a formidable opponent of segregation, he endured some losses in the courtroom, which your book describes. How did these failures shape his life, outlook, and strategy?

LG: In 1936, black citizens were about 15% of the population of Baltimore County, which surrounds but does not include the city of Baltimore. The county had ten public high schools; however, blacks could not attend any of them and had to come into Baltimore City to attend one, overcrowded, high school. For some youngsters, this meant traveling twenty miles daily while passing several public high schools on the way. My book recounts Marshall’s lawsuit on behalf of Margaret Williams, who wanted to go to a county high school near her community. Marshall lost the case, and it was a stinging loss. But, it is remarkable how quickly Marshall brushed off the loss and immediately turned his attention to his next civil rights challenge: the school teacher salary cases. Black school teachers in Maryland counties and throughout the South were paid about half the salary paid to white teachers of comparable education and experience. That was until Maryland state judges and a federal judge in Maryland began to end that practice in lawsuits brought by Marshall, beginning a few months after the Baltimore County high school case. After Marshall relocated to New York to work for the national NAACP, he replicated the Maryland teacher salary cases in nine other states.

A version of this post was originally published on the Oxford African American Studies Center .

Featured Image Credit: “US Supreme Court Building” by MarkThomas. CC0 Creative Commons via Pixabay .

The post From segregation to the Supreme Court: the life and work of Thurgood Marshall appeared first on OUPblog.

A Q&A with plant scientist, Hitoshi Sakakibara

Although plants are so fundamental to our being, there are still many unanswered questions about the foundations of the organisms that support life on earth. We recently sat down with Hitoshi Sakakibara, the Editor-in-Chief of Plant & Cell Physiology to talk about his background, his role at PCP, and why plant science is vital to our lives.

Can you tell us a little about your background and what inspired you to pursue a career in plant sciences?

I studied molecular aspects of plant nutrition and signaling at the Graduate School of Agricultural Sciences of Nagoya University, and several years later, I got a PI position at RIKEN Institute in 2000. Since then, I have studied the molecular mechanism underlying the coordinated response of plants to nutritional cues to optimize their growth and development, especially focusing on the role of phytohormones.

The reason for my specializing in plant science is that plants are autotrophic organisms supporting life on the earth, and plants give us a wide range of benefits, such as food, materials, and medicine. After my starting university around the mid-80s, I realized that there is great potential hidden in plant science because there are still so many fundamental unanswered questions.

Why is this field so important for society as a whole?

As I mentioned, plants are the foundation that support all life on the earth, and since they cannot easily move like animals, they are always exposed to environmental changes. In order to survive, plants have very plastic and robust growth and metabolic control systems. Understanding these regulatory systems would give us important knowledge to further improve the potential of plants, which will be beneficial to human life and the environment.

How do you see this field developing in the future?

The current trend in plant sciences is to understand the behavior of plants at the physiological and molecular level. However, the knowledge obtained so far has not enabled us to freely modify plant functions and traits as we desire. Development of new crop species still mostly relies on breeders’ trial-and-error. This trend might not be changed radically, but I believe molecular plant physiology will greatly accelerate the generation of new plant species contributing to global food security, amongst other benefits, in the future.

Featured image by Stokpic. CC0 public domain via Pexels.

The post A Q&A with plant scientist, Hitoshi Sakakibara appeared first on OUPblog.

Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace: an audio guide

Tolstoy’s epic masterpiece intertwines the lives of private and public individuals during the time of the Napoleonic wars and the French invasion of Russia. Balls and soirees, the burning of Moscow, the intrigues of statesmen and generals, scenes of violent battles, the quiet moments of everyday life–all in a work whose extraordinary imaginative power has never been surpassed.

In this Oxford World’s Classics audio guide, Amy Mandelker, Associate Professor of Comparative Literature at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, discusses Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace and suggests ways of approaching this magnificent – but sometimes rather daunting – masterpiece of world literature for the first time.

Featured image credit: “ The Battle of Austerlitz” by Francois Gerard. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace: an audio guide appeared first on OUPblog.

9.5 myths about the Reformation

This year marks the 500th anniversary of the beginning of the Reformation and Martin Luther’s nailing of his 95 Theses to the doors of Wittenberg Castle Church. But how much of what we think about it is actually true? To coincide with this occasion, Peter Marshall addresses 9.5 common myths about the Reformation.

1. The Protestant Reformation started on 31 October 1517, when Martin Luther nailed 95 Theses to the door of the Wittenberg Church.

The foundation-myth of the Reformation. Luther wrote 95 Theses, but probably didn’t ever fix them to a church door. It was first recorded nearly thirty years later, and Luther himself never mentioned it – though he did, in letters of 1517-18, repeatedly say he didn’t want a public debate until the authorities had a chance to respond to his concerns about indulgences. Even if the Theses were posted, this would have been no big deal. It was the normal way to announce a debate at a medieval university, and the job was undertaken by lowly beadles, not senior professors. The myth matters, though, because it implies something had ‘begun’, with unstoppable momentum behind it. In fact, Luther had no intention of starting a ‘Reformation’ in 1517, and his Theses were in many ways within the bounds of contemporary orthodoxy.

2. Martin Luther was the leader of the Protestant Movement in the Sixteenth Century.

It wasn’t all Martin Luther, even at the beginning. He was an inspiration, but direct influence on policy was limited to the single German territory of Electoral Saxony. The Reformation movement in Germany and Switzerland in the 1520s and 30s was remarkably varied, with numerous local flavours. In Zürich, as early as 1517, Huyldrich Zwingli was much more important than Luther, as was Johannes Oecolampadius in Basel, Martin Bucer in Strasbourg, and – a little later – John Calvin in Geneva. Almost the very point of the Reformation was it didn’t have a ‘leader.’ The Protestant tendency to argue ferociously among themselves was a major source of theological creativity, as well as of practical difficulty.

3. Luther was the first person to translate the Bible into German.

Actually, no. A medieval translation of the Latin Vulgate Bible was printed well over a dozen times in Germany before 1518, and it has been calculated that at least 18 complete German editions of the Bible, 90 editions of the Gospels, and 14 books of Psalms were printed in Germany before Luther’s famous New Testament of 1522. Protestants themselves started the myth that the Bible was completely neglected in the Middle Ages. But if there hadn’t been a huge interest in the Bible among medieval Catholics, Reformation ideas would have struggled to get traction.

4. Protestant reformers wanted freedom of conscience, and for everyone to decide the meaning of Scripture for themselves.

They didn’t! The leading reformers believed the papacy had maliciously twisted and misinterpreted Scripture, and that its true meaning would be evident to anyone who read or listened to it with faithful intent. At the Diet of Worms in 1521, Luther may or may not have said, ‘Here I stand, I can do no other!’ But he did say ‘my conscience is captive to the Word of God.’ When, having read the Bible, some people decided it didn’t validate ideas such as the Trinity, or the baptising of babies, ‘mainstream’ Protestants persecuted them as enthusiastically as any Catholic bishop.

5. Henry VIII founded the Protestant Church of England.

Henry VIII always regarded himself as a totally orthodox and traditional Catholic – it was the pope and his ‘papist’ followers who had abandoned the Catholic Church. Henry hated Luther and continued periodically to burn Protestants up to his death in 1547. Whether you could actually be a ‘Catholic without the pope’ was an argument people pursued at the time, and one that has continued since.

Part of the Reformation Wall in Geneva, depicting Guillaume Farel, Johannes Calvin, Théodore de Bèze and John Knox. Photo by Roland Zumbühl. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Part of the Reformation Wall in Geneva, depicting Guillaume Farel, Johannes Calvin, Théodore de Bèze and John Knox. Photo by Roland Zumbühl. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.6. Sir Thomas More was a ferocious persecutor, responsible for the deaths of dozens of Protestants.

A sixteenth-century myth, given a new injection of life by the phenomenal success of Hillary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. More certainly hated heresy, and believed that unrepentant heretics deserved death – but so did almost every other responsible person in the sixteenth century. During the period when More was Lord Chancellor (1529-32), six Protestants were burned in England, and he was directly involved in three of the cases – a black mark against a saint, but hardly genocidal.

7. Elizabethan England witnessed a reign of terror against Catholics.

A Catholic myth! Catholics certainly had a difficult time after Elizabeth re-established Protestantism in 1559. Catholic worship was banned, there were fines for not attending church, and missionary priests coming from abroad faced real risks: 124 were hanged over the course of the reign. But ordinary Catholics who kept out of politics were not troubled very much: Elizabeth, as Francis Bacon said of her, had no desire ‘to make windows into men’s hearts and secret thoughts.’ Catholicism survived the sixteenth century as part of an increasingly plural religious scene, and some of the great Catholic landed families still remain in possession of their ancestral homes.

8. The Reformation was always bound to fail in Ireland.

The idea that certain peoples – Irish, Spaniards, Italians – were almost genetically programmed to remain Catholic, while others – English, Dutch, Swedes – were bound to become Protestant is a pervasive myth, which ignores how much it came down, in the end, to politics and chance. Henry VIII’s break with Rome encountered little direct opposition in Ireland, and in the towns at least there was genuine interest in Protestant preaching during Edward VI’s reign. It was a failure to put enough preachers (especially Irish-speaking ones) on the ground that left the field open to Catholic evangelists (Franciscans and Jesuits) in the second half of Elizabeth’s reign.

9. Protestants rejected visual images, and swept all artwork from churches.

It depends. Zwingli and Calvin were intensely worried about the dangers of ‘idolatry’, and in places where their ideas took root (such as Switzerland or Scotland) churches were generally white-washed and unadorned. But so long as they weren’t literally worshipped, Lutherans were much more relaxed about statues and paintings. To this day, churches in Germany and Scandinavia are full of Protestant crucifixes and altarpieces from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, often in extravagant Baroque style.

9.5 The Reformation laid the foundations of the modern world

Half-true, or only half-untrue. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Protestants generally didn’t believe in toleration, freedom of conscience, unfettered scientific investigation, or a universe without spirits, demons, and witches. Nor did they want to change the political order (kings in charge) or the social order (husbands and fathers in charge). Nonetheless, the principal result of the Reformation across much of Europe was to create fragmented and plural societies, and a kind of stalemate where no one side could completely convert or eradicate the other. In some places this served to undermine authoritarian rule, and over the long term it led almost everywhere to a grudging acceptance of minorities, and a growing view that religion was a private matter, not the business of the state.

Featured image credit: Painting of Luther nailing 95 theses by Julius Hübner (1806–1882). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 9.5 myths about the Reformation appeared first on OUPblog.

Legal scholarship and methodology in the era of big data

In a recent Financial Times article, the journalist and anthropologist Gillian Tett reflected on the significance of Cambridge Analytica’s (CA) work in relation to Donald Trump’s successful 2016 Presidential Campaign. While Hilary Clinton had run a campaign using what was understood as traditional ‘political’ data, CA had collected many thousands of data points on people, much of it amassed from their online consumer and social identities. As Tett put it, CA were using a broader understanding of people as ‘social creatures’. The apparent success of this approach raises many questions, many of them ethical and many relating to what we think democracy and citizenship is, but as Tett points out there is no way of putting this ‘genie back in the bottle soon’.

The story of CA is important for legal scholars to reflect upon. Law, like politics, is a multi-dimensional social phenomenon. As such, the question about how to approach the study of law so as to gain real understanding is always a live one and has led to the rise of many different schools of legal scholarship over the last century. These schools essentially focus on different ‘data points’ in researching law. Thus doctrinal legal scholarship focuses on legal reasoning in cases and socio-legal scholarship uses a range of different empirical and theoretical methods to map law in society. And there are many other approaches: law and economics, critical legal studies, legal theory, and so on. Law is the data of legal scholars, to paraphrase Steven Vaughan from a recent blog post, but there is a lot of data and many different ways to get one’s head round it.

The problem is that legal scholars have over time clustered into different groupings, with groups rarely interacting and often talking past one another. It is also often the case that each group caricatures the others. Socio-legal scholars wonder at what they see as the analytical naivety of ‘black letter lawyers’; while those lawyers shake their head at what they see as the crude reductionism of law and economics. One of the lessons of the CA story is the way in which one method of data collection and analysis may inform another set of inquiries – consumer choices relate to political choices. This is not to say that politics is just consumerism, but knowing something about our consumer identity tells us something about our political identity.

The same is true in legal analysis. Take for example Keith Hawkins’ classic socio-legal account of enforcement by environmental officers – Environment and Enforcement: Regulation and the Social Definition of Pollution (Clarendon 1984). The book is grounded in over two years’ empirical research of the work of officers in two water authorities in the United Kingdom that enforce pollution law. It’s easy to pigeonhole this book as a study of the ‘extra-legal’ process of enforcement. Hawkins brings alive the ‘art’ of pollution control work which requires many ‘personal qualities’ including ‘a constant display of helpfulness and reasonableness’. But it is much more than that. It is also a study of the uncertainty of regulatory law and thus law itself. Prosecution may be a last resort as Hawkins shows, but law is ever present. It provides the mandate and context for pollution officers, who are themselves legal actors. Thus, law haunts Hawkins’ account. While the transcripts of interviews with pollution officers describing their work and the interactions with those they regulate may not directly be about law they tell the reader a lot about what law can be. The stories about bluffing, bargaining, and officers appearing on ‘plush carpets’ in ‘dirty wellies’ because they have been investigating oil pollution are not just random stories, but a careful piece of ‘interpretative sociology’ that helps us understand something about law’s place in the world. This is not to say all data points are equal. Hawkins’ study, a work many years in the making, offers insight because he thought carefully about what it was he needed to record and make sense of. The study of any particular data requires the fostering of a particular set of skills and expertise.

“For scholars, big data creates new questions about what it is we should study, and what skills we should foster in ourselves”

Recognising this is not new (that is why we have methods courses for research students), but in the era of big data there is simply a lot more data that legal scholars could analyse and thus the issue of which data can be analysed and how it should be analysed takes on greater significance. The study of some data points enhances understanding, but other data points are just ‘noise’. Some lines of analysis unearth a fundamental truth and others just result in a non-falsifiable hypothesis. For scholars, big data creates new questions about what it is we should study, and what skills we should foster in ourselves, and as Vaughan points out, in our students.

And this is not merely a set of ‘technical questions’. Just as the study of voters raises big questions about morality and the nature of democracy, a study of law through these data points raises questions about how law and legal reasoning operates in a society and how we think it ought to operate. Methods of research raise moral and existential questions and scholars need to be ever vigilant in their quest of finding the best way to make sense of law so as to deepen human understanding – a point that, as Ben Pontin recently highlighted, is ever present in researching environmental law history.

To build on Tett’s comment, the ‘genie’ of methodological choice is indeed out of the bottle. It is not a new genie for legal scholars and we have much to learn from reflecting on our intellectual pasts. But in the era of big data it is a very powerful one in many different ways – some perhaps good, some perhaps bad. We ignore it at our peril.

Featured image credit: ‘Server room’ by NeuPaddy. CCO Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Legal scholarship and methodology in the era of big data appeared first on OUPblog.

October 29, 2017

Blue Planet II returns

Blue Planet returns to our television screens tonight as Blue Planet II, 16 years after the first series aired to great critical acclaim. The series, fronted by Sir David Attenborough, focuses on life beneath the waves, using state-of-the-art technology to bring us closer than ever before to the creatures who call the ocean depths their home. Over the coming weeks, we’re going to be sharing a selection of content from our life science resources, focusing on the theme of that week’s episode of Blue Planet II, over on our Tumblr page.

The topics we’ll be exploring include: ‘the deep’, coral reefs, ‘green seas’, ‘big blue’, coastlines, and the future of our oceans. To kick things off as an introduction, we’re thrilled to share with you a collection of articles and facts all about our wild and wonderful oceans, along with a selection of articles touching on the themes of upcoming episodes to whet your appetite. Be sure to head over to our Tumblr page on the 5th November for the next instalment of our Blue Planet II series!

An overview of our oceans

“The marine environment is the planet’s largest and most important habitat, and covers 3.6 x 1014 m2, which represents about 71% of the Earth’s surface; contains more than 99 per cent of its habitable living space; represents its largest repository of living matter; produces half its primary production; and supports a remarkably diverse and exquisitely adapted array of life forms, from microscopic viruses, bacteria, and plankton to the largest existing animals.”

Underwater by lpittman. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Underwater by lpittman. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Evidence of ocean exploration comes long before written records, with Homo erectus, an early hominid, mastering crossing the relatively small stretches of water that separated one island from another along the Indonesian archipelago, where they established a presence on the island of Flores. There is then an extensive gap in marine archaeological knowledge, before the first waves of Homo sapiens migration out of Africa around 70,000 years ago.

China recently began investing in deep-sea research, leading to the launch of its first multidisciplinary deep sea research program, the “South China Sea”, in 2011.

What are the implications for marine mammals of large-scale changes in the marine acoustic environment? Human sources of sound in the ocean (such as ship traffic, air guns for seismic exploration, and sonar for military and commercial use) can disturb marine mammals, evoking behavioural responses that can be viewed as similar to predation risk, and they can trigger allostatic physiological responses to adapt to the stressor.

Marine mammals and their environment in the twenty-first century: what are the threats facing our marine environments today?

Four different phenomena cause the ocean’s circulation: The wind drags surface waters, inducing surface currents. These surface currents, combined with precipitation and evaporation, create “hills” and “valleys” at the ocean surface that induce pressure changes that generate currents over depths of hundreds or even thousands of meters. Density gradients due to differences in temperature and salinity may also cause horizontal and vertical water masses motions, and tidal currents, which are due to the gravitational fields of the Moon and the Sun. Tides play an important role for the deep ocean mixing.

Marine mammals as ecosystem sentinels: Species dependent on sea ice, such as the polar bear (Ursus maritimus) and the ringed seal (Phoca hispida), provide the clearest examples of sensitivity to climate change.

Conservation physiology can provide insights into pelagic fish demography and ecology by uniting the complementary expertise and skills of fish physiologists and fisheries scientists, which is crucial for effective management and successful conversation of pelagic fishes.

Turtle by 12019. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Turtle by 12019. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.Studies in marine science and fisheries experienced a gradual shift from focusing on limited spatial and temporal national and regional issues in the 1960s through 1980s, to more broadly-based ecological goals focused on recovery and sustainability of coastal ocean goods and services from a global perspective today.

Increasing the size and number of marine protected areas (MPAs) is widely seen as a way to meet ambitious biodiversity and sustainable development goals. Yet, debate still exists on the effectiveness of MPAs in achieving ecological and societal objectives. Although the literature provides significant evidence of the ecological effects of MPAs within their boundaries, much remains to be learned about the ecological and social effects of MPAs on regional and seascape scales. Key to improving the effectiveness of MPAs, and ensuring that they achieve desired outcomes, will be better monitoring that includes ecological and social data collected inside and outside of MPAs.

Cycling of carbon in the upper ocean remains a key aspect in understanding the ability of the world’s ocean to buffer the atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) increase and control the associated raise of pH. So far, the balance between primary production and ecosystem respiration has been shown to be regulated and balanced mostly by photo- and microbial respiration involving zooplankton communities.

Featured image credit: Jellyfish by Free-Photos. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Blue Planet II returns appeared first on OUPblog.

Are we all living in the Anthropocene?

In 2000, atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen and biologist Eugene Stoermer published a short but enormously influential article in Global Change Newsletter. In it, they proposed the adoption of a brand new geological epoch: the Anthropocene. Their argument: humans have had and will continue to have a drastic impact on the planet’s climate, biodiversity, and other elements of the Earth system, and the term “Anthropocene” – from the Greek anthropos, or “human” – most accurately describes this grim new reality. Therefore, they concluded, the Anthropocene should officially supersede the Holocene, a relatively stable 12,000-year period following the most recent ice age. In 2016, the Anthropocene Working Group, comprised of an international group of scientists, submitted a proposal to formalize the term as an official unit of geological time.

For many, the idea of the Anthropocene seems reasonable. Scientists have found it useful as a way to explain oddities like plastiglomerate, a rock-hybrid substance found on a beach in Hawaii in 2006. The result of plastic garbage melted down by wildfires, lava flows, or ocean vents and fused with rock and sand particles, plastiglomerate fits neatly within the Anthropocene narrative outlined by Crutzen and Stoermer.

Moreover, the idea of the Anthropocene continues to attract attention across academic disciplines and in popular discourse and has become something of a meme. The Anthropocene animates discussions amongst environmental humanists, working in fields like philosophy and literary studies, committed to exploring human value systems and motivations that have contributed to current planetary crises. Beyond academia, it has become a trendy issue in environmentalist and political circles, serving as a thematic topic for international seminars such as the UN’s Rio+20 Summit, as well as scientific and environmental journalism, appearing in outlets such as Smithsonian Magazine and NPR’s TED Radio Hour podcast. For some, the idea of the Anthropocene is flattering, suggesting that as masters of our universe, we’ll geo-engineer ourselves out of climate disaster. For others, the Anthropocene amounts to the horrifying realization that “we are the meteor,” destined to doom ourselves through overzealous consumption of the planet’s finite resources.

“Grandpa” by Herriest. CC0 via Pixabay.

“Grandpa” by Herriest. CC0 via Pixabay.Not everyone, however, has warmed to the newly-proposed epoch. Here’s why: as a concept, the Anthropocene operates under the assumption that the human species as a whole is responsible for potentially irreversible environmental catastrophe without acknowledging that some (read: industrialized Western societies) are far more responsible than others (developing nations, indigenous peoples) for rising carbon emissions, ocean acidification, industrial pollution, and the like. Moreover, the Anthropocene is, by default, anthropocentric – in other words, it puts the human species on a pedestal, portraying it as a supreme agent of change. This is arguably how we got here in the first place: certain groups of humans – particularly those committed to advancing colonial, imperial, and capitalist agendas – have long sought to “conquer” or “tame” nature in pursuit of wealth and driven by a deep belief in the superiority of the human species, especially certain “privileged” groups (read: white, Christian, male).

Because of these features, the Anthropocene does not necessarily resonate within indigenous communities, many of whom are disproportionately affected by climate change and environmental injustice. As scholar-activists like Joni Adamson, Kyle Whyte, and Giovanna Di Chiro point out, because many indigenous communities view the world as non-hierarchical, a network of humans and nonhumans deserving equal rights and protections, the Anthropocene at times remains peripheral or absent from indigenous-led environmental and climate justice movements. The concept of the Anthropocene does not fit neatly within indigenous knowledge systems organized around interdependent relationships among humans and nonhuman plants, animals, and ecosystems.

Instead, indigenous activists continue to successfully pursue political and legal reforms that recognize these knowledge systems, such as Bolivia’s adoption of the Law of the Rights of Mother Earth (2011) or the Universal Declaration on the Rights of Mother Earth ratified at the People’s Assembly on Climate Change in 2010. In March 2017, Māori peoples of New Zealand won legal recognition for the Whanganui River. By law, the river must be treated as a living entity with the same legal rights as a human being. This marks a huge victory for the Māori, who view themselves as one with and equal to their natural surroundings. Later this year, Hindu groups attained similar legal status for India’s Ganges and Yamuna Rivers, too.

So, what does this mean for the Anthropocene?

In the very least, it affirms that not all of us are necessarily living “in it,” and that geological time is but one way of understanding and approaching the current climate crisis. It is merely one tool in the toolbox, so to speak, and should be considered alongside other scientific, political, and imaginative means of engaging with climate change. And I’ll end with this: it is the imagination, channeled through literature and art, that I find the most democratic, and therefore the most promising, tool in the toolbox. From recently popularized genres like climate fiction, or “cli-fi,” to novels, short stories, poetry, and film from multi-ethnic and indigenous writers and artists like Karen Tei Yamashita, Linda Hogan, and Juan Carlos Galeano, we are able to explore (and question) a wide range of thought-systems and concepts, including the Anthropocene, that enable us to imaginatively cope with an increasingly unpredictable climate in ways that are socially just.

Featured image credit: Untitled by Andre Cook. CC0 via Pexels.

The post Are we all living in the Anthropocene? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers