Oxford University Press's Blog, page 300

November 16, 2017

World Philosophy Day 2017: political philosophy across the globe [map]

The third Thursday in November marks World Philosophy Day, an event founded by UNESCO to emphasise the importance of philosophy in the development of human thought, for each culture and for each individual. This year, the OUP Philosophy team have decided to incorporate the Oxford Philosophy Festival theme of applying philosophy in politics to our World Philosophy Day content. If you would like to read further about this topic, visit our content hub for a curated list of online resources on the topics being covered by the speakers.

We have also put together an interactive map with some of the many fascinating political philosophers from across the globe. Find out more about different perceptions of political philosophy around the world, as well as some of the areas of overlap.

Map background: CIA WorldFactBook-Political world. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

Featured image: Galaxy world map by 3333873. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post World Philosophy Day 2017: political philosophy across the globe [map] appeared first on OUPblog.

November 15, 2017

What can we all do to tackle antibiotic resistance?

Welcome to the Oxford Journals guide to antibiotic resistance. The 13th – 19th November marks World Antibiotic Awareness Week, an annual international campaign set up by the World Health Organisation (WHO) to combat the spread of antibiotic resistance, and raise awareness of the potential consequences. Even better, it’s not just scientists, politicians, and medical professionals who can work towards a solution – you can be part of it too. Let’s start with the basics:

What exactly is an antibiotic?

Antibiotics are the medicines used to prevent and treat bacterial infections. They do not treat colds, flu, or other viral infections. And they aren’t just used on humans; some animals are also regularly given antibiotics to make them grow faster, or help them survive stressful, crowded, or unsanitary conditions.

What is antibiotic resistance?

Bacteria can change and evolve in response to the medicines we use, eventually becoming resistant to the effects of antibiotics. It is always the bacteria that become resistant, not the person or animal. The antibiotic-resistant bacteria are then spread via food, the environment – contaminated water, for example – or by direct contact with infected humans or animals.

“Antibiotics do not treat viral infections, like colds and flu.” GIF used with permission from the WHO.

“Antibiotics do not treat viral infections, like colds and flu.” GIF used with permission from the WHO.So what? Why is antibiotic resistance a problem?

When bacteria become resistant to our medicines, the symptoms they cause become harder to treat. If you get an infection from antibiotic-resistant bacteria it can incur higher medical costs, lead to prolonged stints in hospital, and carries higher risk of permanent consequences, including mortality.

Now you have an overview of the problem, the next step is moving towards a solution. There are many facets to the problem, and there is no magical cure. For starters, we asked some of our journal editors to explain what scientific research is doing to help in the fight against antibiotic resistance:

“By now many, if not most, people will be aware of the threat antimicrobial resistance poses to global health. The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy is dedicated to playing its part and currently devotes much of its content to this problem and to potential solutions. The journal particularly focuses on how to gain a better understanding of what is needed to optimize the use of the antimicrobial agents we already have, on new approaches to overcoming resistance, and on new drugs that are in development.”

— Peter Donnelly, Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy

“Antibiotic resistance is a growing problem worldwide, more particularly in developing countries that are very popular destinations for travellers. As a consequence multi drug resistant (MDR) bacteria may be imported by travellers in Western countries. The spectrum of infection is wide from asymptomatic carriage to life-threatening infections. Urinary tract infections and pyoderma are leading causes of consultation in travellers returning from tropical countries, and may be due to MDR bacteria, respectively Enterobacteriacae and Staphylococcus aureus. These MDR bacteria may even be further transmitted in the community and the hospital setting.”

— Eric Caumes, Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Travel Medicine

“The rise of #AntibioticResistance is leading to untreatable infections which can affect anyone, of any age, in any country.” GIF used with permission from the WHO.

“The rise of #AntibioticResistance is leading to untreatable infections which can affect anyone, of any age, in any country.” GIF used with permission from the WHO.

“AMR will be a very persistent problem. Pathogenic bacteria will always find a way to outsmart us and will develop resistance to every new drug we’ll create. This sounds like bad news and in a sense it is. But we can tackle the problem by taking several measures, including good stewardship, fast and reliable diagnostics, but above all by continuously applying novel concepts in drug development. We have too long been satisfied by directly mining nature and using chemical modification of existing antibiotics. We now need to be more creative and apply novel methods in screening and eliciting production of natural products, but also by using new scaffolds and templates for chemical- and bioengineering, new administration methods and other ways of regulating their bioactivity. In this way, we can keep on refuelling the pipeline of novel lead molecules to be taken into drug development programs, and be safe in the future against ever occurring highly resistant pathogenic strains.”

— Oscar Kuipers, Editor, FEMS Microbiology Reviews

It’s excellent to know that key research is already taking place, but there are things that you can do right now to help improve the outlook for the future:

Prevent infections – wash your hands regularly, avoid other people when you’re unwell, and make sure all your vaccinations are up to date.

Only use antibiotics when they have been prescribed for you by a certified health professional – and trust their judgement when they don’t give you any.

Always take the full prescription – even if you start to feel better after a few days, the bacteria are still in your body, and stopping halfway through will give them time to adapt, evolve, and become resistant to that particular medicine.

Never share antibiotics with anyone else, or use leftover antibiotics.

Featured image credit: Featured image credit: Biofilm of antibiotic resistant bacteria by Kateryna Kon. © via Shutterstock.

The post What can we all do to tackle antibiotic resistance? appeared first on OUPblog.

Nine of diamonds, or the curse of Scotland: an etymological drama in two acts: Act 1

The origin of this mysterious phrase, “nine of diamonds,” has been discussed for over two hundred years. Nor are surveys wanting. I cannot say anything on this subject the world does not know, and I have no serious preferences for any of the relatively promising hypotheses. Yet I have probably amassed more clippings on this mysterious expression than any of my predecessors (the archives of the OED must contain a richer treasure trove, but it is out of public view), so that sitting on such a collection makes me feel a bit like the dog in the manger. In addition to dictionaries and books, I, as always, have a heap of articles and notes from The Gentleman’s Magazine, Notes and Queries, and The Spectator. Below, I’ll dispense with references, but, if someone needs them, I’ll be happy to provide both volume and page numbers.

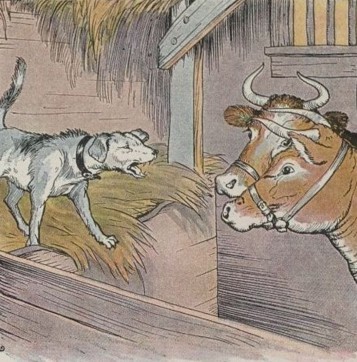

“The dog in the manger, not a character to emulate.” Image credit: The Dog in the Manger courtesy of Project Gutenberg. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“The dog in the manger, not a character to emulate.” Image credit: The Dog in the Manger courtesy of Project Gutenberg. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Enter Prolog: On Cards, Men, and Numerals

“The queen of clubs is called in Northamptonshire Queen Bess, perhaps, because that queen, history says, was of a swarthy complexion [and for that reason some imaginative scholars thought that Shakespeare’s Dark Lady of the Sonnets, who, incidentally, is never called either lady or dark in the poems, was the queen]; the four of spades, Ned Stokes, but why I know not; the nine of diamonds, the curse of Scotland, because every ninth monarch of that nation was a bad king to his subjects. I have been told by old people, that this card [nine of diamonds] was called long before the Rebellion in 1745, and therefore it could not arise from the circumstance of the Duke of Cumberland’s sending orders, accidentally written upon the card, the night before the battle of Culloden for General Campbell to give no quarter” [about all these things more will be said next week]. With regard to every ninth monarch being evil, it should be remembered that nine is a common number in myths and later folklore (for instance, the Scandinavian god Odin hanged himself as part of a mysterious self-sacrifice and was suspended from a tree for nine nights. See also my post titled “Nine Tailors Make a Man” for April 6, 2016. Every mention of nine in popular stories should arouse a researcher’s suspicion.

“The most unfortunate of all cards, as far as one tradition goes.” Image credit: “Diamonds Nine 9 Card Recreation Games Cards” by Clker-Free-Vector-Images. CC0 via Pixabay.

“The most unfortunate of all cards, as far as one tradition goes.” Image credit: “Diamonds Nine 9 Card Recreation Games Cards” by Clker-Free-Vector-Images. CC0 via Pixabay.The Case of a Missing Card

It has been documented that people, sometimes important personalities, did scribble notes on the reverse of playing cards. And the card allegedly written at Culloden has been invoked many times in the discussion of the phrase the curse of Scotland. Has it been found? “…I am told on good authority that the identical card is preserved at Slains Castle, Aberdeenshire, the seat of Lord Errol” (written in 1893). Alas and alack! Half a year later, in 1894, a rejoinder appeared: “…my friend Capt. Webbe, who married a sister of the present Lord Errol, has most kindly made a search for this card, and he writes to me: ‘…the only card I can find among the Kilmarnock papers is the eight of diamonds; it has a short letter written on the back of it from the Duke of Hamilton to the Countess of Yarmouth, expressing regret at his not having been able to call upon her. There is no other card, nor has my wife ever heard of there ever having been another in existence here’.” This is a bit of an anticlimax. By way of consolation, I may add that the name of Little Lord Fauntleroy’s mother (“Dearest”) was Mrs. Errol. She too had been married to a captain, the youngest of the three sons of the Earl of Dorincourt.

“Beware of the evil playing cards may bring!” Image credit: “Military Alice In Wonderland Disneyland Paris Theme” by dassel. CC0 via Pixabay.

“Beware of the evil playing cards may bring!” Image credit: “Military Alice In Wonderland Disneyland Paris Theme” by dassel. CC0 via Pixabay.The Plot Thickens: Cards, Like an Ill Wind, Bring No One Any Good

One of the card games bears the name Pope Joan. It was possibly introduced to Scotland by Mary of Lorraine (1515-1560), regent of her daughter Mary Stuart, or James, Duke of York, later King of England (1631-1701), the last (deposed) Catholic English king. In the game, the nine of diamonds, or the Pope, is the winning card, and the story goes that many Scottish courtiers were ruined because of their addiction to that game. The antipapal spirit of the Scots supposedly caused the pope to be called the Curse of Scotland. This game was originally called Pope Julio and goes back to the reign of Queen Elizabeth (Queen Bess). I note with some unease that the sources mention another equally deleterious French game, called comette or comète, also introduced by Mary of Lorraine. Comète was played with two

whole packs, the first containing all the red cards, the other the black. Each pack was to be used alternately, the nine of diamonds being the red comète, and the nine of clubs the black. By this method there will be two comètes moving in the same circle, and each equally liable to be called the curse of Scotland.

Cards and Phonetics. Say No to Sentimental Guessing

Curse in the phrase curse of Scotland may be an old way of pronouncing cross in Scotch. “St. Andrew is the patron saint of Scotland; he suffered on a cross, not of the usual form, but like the letter X, which has since been commonly called a St. Andrew’s cross.” This was written in 1849. An immediate refutation followed this conjecture: “The nine resembles St. Andrew’s cross less than five, in a pack of cards; and, moreover, the nine of any other suit would be equally applicable.” Incidentally, the same objection should be leveled against the connection between the card and every ninth king of Scotland being a tyrant. But lo and behold! In 1875, the old idea occurred to another correspondent. Obviously, the author did not know that he had a predecessor (a common curse of those who love rushing into print) and concluded his note on a melancholy note: “This may be held to be somewhat fanciful, but it is a fanciful matter with which we are dealing.” Yet he was self-confident: “This derivation does away with a great deal of sentimental guessing; but I have no doubt it is the true one, though the question still remains, why was it applied to the Nine of Diamonds, and not to any of the other nines? I have not considered this point.” Beware of the etymologists who say I have no doubt. And indeed why just nine of diamonds? (See above!) We again witness reference to the form of the cross: “When I say the form of the Nine of Diamonds suggests (to some extent) the form of St. Andrew’s Cross, it is meant that we may suppose two cross lines proceeding from the diamonds at the foot.

Image credit: Martirio de San Andrés by Juan Correa de Vivar. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Martirio de San Andrés by Juan Correa de Vivar. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Cards and Taxes

In 1894, the following excerpt from The History of Scotland by John Hill Burton was quoted: “Diamonds, nine of, called the curse of Scotland, from Scotch member of Parliament, part of whose family arms is the nine of diamonds, voting for the introduction of the malt tax into Scotland.” As conjectured, the Member of Parliament might be Daniel Campbell of Shawfield, member for Glasgow, provided his arms contained nine lozenges. His house was destroyed by a mob in 1727, because he was suspected of “having given Government the information on the habits and statistics of Scotland necessary for the preparation of the malt tax, as well as of having exposed a system of evasion of duties in the Scots tobacco trade.” Shawfield riots are a well-documented event. The rest is intelligent guessing.

To be continued.

Featured image: “C M Coolidge Dogs Canines Poker Cards Humor” by 12019. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Nine of diamonds, or the curse of Scotland: an etymological drama in two acts: Act 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

Place of the Year 2017 Longlist: Vote for your pick

With the end of 2017 approaching, and in conjunction with the publication of the Atlas of the World, 24th edition, today we launch our efforts to decide on what the Place of the Year (POTY) 2017 should be. Many places around the world (and beyond) throughout the past year have been at the center of historic news and events, but which location was the most noteworthy?

To get an idea of what stood out most, we turned to the people of New York City at Bryant Park and asked them what they thought the Place of the Year should be. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many New Yorkers agreed that the Big Apple deserved to win the POTY award for 2017. Other answers included Istanbul, Charlottesville, and North Korea.

We also asked our colleagues at Oxford University Press for their help to create a longlist and they all came back with some interesting and significant nominations. So now we open up the question to you: what do you think should be the Place of the Year for 2017?

With your input, we’ll narrow the list down to a shortlist to be released on 21 November. Following another round of voting from the public, and input from our committee of geographers and experts, the Place of the Year will be announced on 4 December. In the meantime, we’ll be posting here regularly with insights on the POTY contenders. Vote in the poll below by 17 November. Or, if you think there’s a place we missed, please let us know in the comments.

Place of the Year 2017 longlist

We thank the Bryant Park Corporation for assistance with the creation of our video.

Featured image credit: THE REMEDY IS TRAVEL by Andrew Neel. CC0 public domain via Unsplash.

The post Place of the Year 2017 Longlist: Vote for your pick appeared first on OUPblog.

Found: a viable, alternative model of the firm?

In recent years, many things have gone wrong with the conventional ways of organising and conducting business. And the problems persist; indeed they have spread and become endemic. These include short-termism, insecure work, extreme disparities in rewards and life chances, ethical failures, dishonesty and manipulation, and periodic hollowing-out followed by corporate collapse and wider economic crises.

The system has, in many ways, become self-defeating and unstable even in its own terms. The single-minded pursuit of shareholder value courts a tolerance of malpractice which sets the scene for a race to the bottom. At the heart of the system is the model of the modern corporation. In many ways, it now seems unfit for purpose in the context of the global economy. The John Lewis Partnership is illustrative of an alternative approach: one which seeks to balance the interests of multiple stakeholders; which distributes knowledge, power and reward more widely; and one which enables at least some democratic accountability.

It might be thought that the JLP model is already well-known: a popular, middle class retailer, offering quality goods and dedicated customer service from owner-partners. But, from our long engagement with the organisation, we conclude that the JLP phenomenon is more complex and more interesting than these well-known features portray.

The Partnership is dedicated to the dual objectives of partner happiness and a successful business. Many insiders believe that the one drives the other. So, it is not a choice between ‘nicer or better’ but both — in a mutually, reinforcing way. However, this practice is not so straightforward. We find that the model does not automatically deliver the goods. Indeed, there have been periods when the organisation was considered dated, dowdy, and plagued by complacency.

The organisation is not answerable to the City and can thus pursue longer-term objectives. It can, and does, use its own assets to invest and also borrows for the same reasons. The strategic choices around allocation of resources between investment for the future, rewards to partners in the form of salaries and the annual bonus, the pension fund, and customer service, represent ongoing tensions.

The key to success is found in the skillful ongoing attention to managing these tensions. But, the enabling platform to their actions is provided by the Articles of Association and the Constitution, the culture, and the cultivated set of expectations which nudge directors into (mainly) doing the right thing.

So, could other businesses adopt this model? In part yes. JLP point the way to the how and to the rewards. However, many business owners will baulk at the prospect of adopting the full package which requires the sharing of ownership and of power. Instead, partial cherry-picking seems likely to be (at best) the chosen path.

Featured image credit: John Lewis Newcastle by Mankind 2k. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Found: a viable, alternative model of the firm? appeared first on OUPblog.

5 facts that help us understand the world of early American yoga

Since the publication of Mark Singleton’s Yoga Body, the yoga world has been swirling with the notion that the postural practice you’ll find in today’s fitness centers is not nearly as old as we’ve liked to imagine. With the release of Singleton’s collaboration with James Mallinson—Roots of Yoga—the jury is still out on the precise role of yoga poses in the practice’s long and varied history. It is nevertheless plain to see that yoga’s root system is far more extensive and complex than even the most respected popularizers, such as B.K.S. Iyengar’s midcentury classic Light on Yoga (1966), would have us believe.

However, long and varied as yoga’s history on the Indian subcontinent may be, its comparatively short residency on American soil is no less interesting. Early American yoga—a concept held together only by the fact that it appears to belong to a cast of characters who call themselves yogis—oscillates between the menacing and the marvelous, the magical and the mechanical, the strange and the familiar. Here are five facts from the world of early American yoga.

1. Americans were pretty scared of yogis

Nineteenth-century American audiences largely imagined yogis as magicians and ascetics reclining on their beds of nails. To explain these wonders in light of modern demands of science and rationalism, they tended to attribute the yogi’s abilities to their highly developed hypnotic powers, which allowed them to exercise control over his own mind and body but also those of others. When actual flesh-and-blood yogis began arriving on American shores, the same audiences were equally fascinated and terrified by their potential powers. Popular media churned with stories of women going hopelessly insane after having attended a lecture by this or that Swami. Husbands and children were abandoned and fortunes signed away under the hypnotic sway of the yogi’s sinister gaze.

Headline from the Washington Post, February 12, 1912. Courtesy of Anya P. Foxen

Headline from the Washington Post, February 12, 1912. Courtesy of Anya P. Foxen2. Yogis were some of America’s first superheroes

For all the panic over their sinister powers, yogis—or less threatening white imitators—became some of America’s first superheroes. Arguably the first such character appeared on radio and the silver screen rather than the pulp page. Chandu the Magician, born Frank Chandler, was an American who traveled to Tibet to learn Eastern magic from a yogi Master—or several, the details are not consistently clear—and returned endowed with superpowers and a turban that aided him through a myriad of mysteries and adventures. After Chandu’s debut in the early 1930s, a literal army of comic book imitators followed. At least seven superheroes who had traveled to the Orient and returned wearing some combination of a tuxedo, a cape, and a turban appeared by 1940.

Yarko the Great, a stage magician with real magical powers, created by Will Eisner of Wonder Comics in 1939. Public domain via notasdecine.

Yarko the Great, a stage magician with real magical powers, created by Will Eisner of Wonder Comics in 1939. Public domain via notasdecine.3. Yogis were into science

Hypnotism and superpowers aside, early transnational yogis were incredibly interested in substantiating their metaphysical claims in the language of modern science. While visiting the US Swami Vivekananda enjoyed a tête-à-tête with none other than Nikola Tesla. The Swami left the meeting excited by Tesla’s promise that he could mathematically demonstrate that force and matter are reducible to potential energy (thus theoretically supporting some of the Swami’s loftier claims) and Tesla was inspired to write a short essay on “Man’s Greatest Achievement,” which argued that humanity was on the verge of scientific discoveries that would endow humans with god-like powers. Some forty years later, Paramahansa Yogananda would fill his spiritual classic, Autobiography of a Yogi, with similar claims by appealing to the work of Einstein.

4. Yogis consciously borrowed from and built on European physical culture

Early physical practices prescribed by yogis on American soil often did not resemble the yoga postures of today. As illustrated above, Yogananda as well as several of his contemporaries relied on basic exercises from European systems of calisthenics to provide a physical dimension to their systems of practice. Half a world away, Indian innovators such as Tirumalai Krishnamacarya and Sri Yogendra were coopting more complex European gymnastic forms to supplement their repertoires of asanas. Indeed, Yogendra’s manuals on yoga—among one of the first when they were published in the late 1920s—openly referred to multiple contemporary European and American systems as comparable but ultimately inferior (due to their lack of systematic reliance on breath) to his own.

A torso rotating exercise featured in Yogananda’s Yogoda system, which was almost certainly based on European forms such as those found in Danish physical culturalist Jørgen Peter Müller’s 1904 work, Mit System (My System). Courtesy of Anya P. Foxen

A torso rotating exercise featured in Yogananda’s Yogoda system, which was almost certainly based on European forms such as those found in Danish physical culturalist Jørgen Peter Müller’s 1904 work, Mit System (My System). Courtesy of Anya P. Foxen5. American yoga shares its origins with modern dance

The physical postures that we recognize today as yoga asanas would have been likely to be identified as dance poses by early-twentieth-century Americans. The ubiquity of a system of physical expression known as Delsarteism, the rising popularity of “Oriental dance” as an exercise regimen and general pastime of middle-class American women, and the flourishing exchange between Indian and Euro-American traditions of physical culture created a whirlwind of bodily expression that, by the 1920s, birthed modern yoga in India on the one hand, and modern dance in America on the other. It would take another few decades before Americans fully came to associate the light dance-like gymnastics practiced by middle-class American women with the breath-driven asanas introduced to them by the second-wave of transnational yogis.

American dancer Ruth St. Denis teaches a “yoga class” Denishawn school in Los Angeles, 1915. Public domain via the New York Public Library.

American dancer Ruth St. Denis teaches a “yoga class” Denishawn school in Los Angeles, 1915. Public domain via the New York Public Library.Featured image credit: Yoga Uyuni Salt flat by Farsai C. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post 5 facts that help us understand the world of early American yoga appeared first on OUPblog.

November 14, 2017

Inter-racial relationships laid the foundations for immigration in Britain

In the public imagination the inter-war period is today characterised as a period of economic, moral and political collapse among European nations. Crippling economic depression, ethnic ultra-nationalism, fascism, eugenics, anti-Semitism and racism are all closely and inseparably linked with the years between 1918 and 1939. Working-class Britons of the period have been characterised as having enthusiastically fed on a regular diet of Empire Day pageantry and jingoism which fostered among them a deep hostility to anything, or anyone, considered to be alien. A combination of chauvinism, competition for jobs and even psychosexual inadequacy have all been posited as underlying causes for white working-class antagonism to non-white migrants in their midst. The port riots of 1919-1920 between anti-immigrant mobs and non-white seafarers are a case in point. Indeed, the attitude of the British working classes toward non-whites during this inter-war years has often been gauged by these events.

However, as a historian of non-white immigration to Britain in the early twentieth century – the period when the British Empire was at its fullest extent and its propaganda penetrated deepest – I have studied evidence to suggest that there is another, strikingly different, story to tell. It suggests that numerous white working-class natives – those who came into regular contact with men who had arrived from Britain’s colonies in search of work – had not swallowed the racial justifications for empire. Moreover, newcomers and natives were, for the most part, willing and able to rub along quite tolerably with each other, often forming lasting and positive relationships.

My research into ‘mixed marriages’ in Britain during the early twentieth century – specifically those where one partner had a Muslim name – shows their widespread distribution across the country. As one would expect for a migration primarily originating among seafarers, concentrations of such couples existed in deep-water ports such as London, Cardiff, South Shields and Liverpool. However, clusters of marriages are also located in towns and cities across Britain, many of which are inland. George Orwell and J.B. Priestley noticed Asian migrants in British cities, although neither appeared able to properly comprehend their presence. Priestley, in his travelogue and social commentary English Journey, described the children of unions between natives and newcomers, disparagingly referring to their parents as ‘the riff-raff of the stokeholds and the slatterns of the slums…’

My research, focused on the Yorkshire steel-making city of Sheffield (summarised in my recent Past and Present article ‘The Social Networks of South Asian Migrants in the Sheffield Area During the Early Twentieth Century’), used records of marriages, births and deaths, electoral registers, census returns, local press reports, family testimony and working-class memoirs as its evidence base. It shows early arrivals of Muslim South Asians from the First World War onwards. Some, such as Ayaht Khan, Noor Mohammed and Ali Amidulla, settled down and raised families with their white working-class wives (also see my blog post The Afghan queen, the Sheffield steelworker’s daughter, and a more ‘sanguine’ approach to migration history). The men worked in heavy industry or as door-to-door pedlars and street hawkers. In the 1930s, they were joined by Sikh men similarly employed in peddling as well as in the building trades.

“Many migrants are presented not as alien interlopers, but as remarkably embedded within the life of their neighbourhoods.”

What is common for most of the migrants located by my study is that a substantial proportion of them formed relationships with white working-class natives who played significant roles in the newcomers’ lives. Natives appear in records and testimony as wives, in-laws, workmates, friends, co-lodgers, and neighbours to the migrant men. Native in-laws and workmates provided them with accommodation, as did families running general lodging houses. Natives witnessed marriages and supported couples when they found themselves in difficulties, such as when the authorities harassed them with spurious challenges to their British subject status. In short, many migrants are presented not as alien interlopers, but as remarkably embedded within the life of their neighbourhoods.

Most significantly, native-newcomer households aided new arrivals in Britain – often kinsmen of the husband – providing them with lodging and cultural orientation. They helped them find work and introduced them to the broader native-newcomer social network. Native-newcomer households also acted as anchor points for chains of kinship migration between India and Britain. This process, whereby mixed couples acted as agents of ongoing migration, was replicated in individual households across the country. When considered in aggregate, it made a significant, possibly vital, contribution to successful migration and settlement. Mixed households acted as nodes on social networks that sustained flows of migrants to Britain throughout the inter-war period, the Second World War and into the Windrush era of mass New Commonwealth immigration. In the testimony of pioneer migrants, a great many acknowledge the mixed households into which they were welcomed upon their arrival in Britain.

Unfortunately, this is a largely overlooked aspect of Britain’s story of immigration and settlement by the peoples of its empire. This may be due to a tendency to view British society as monolithic in its support for imperialism and in its attitudes to racial and ethnic difference during the first half of the twentieth century. As migration historian Laura Tabili has pointed out, this view has stressed ‘barriers between rather than dialogue among’ the people of Britain and ‘has isolated migrants analytically from British society and history.’ While state archives may offer us valuable insights into the thoughts and deeds of British imperialism, they tell us precious little about the situation on the ground. In order to look beyond such a monolithic view of British society we must look elsewhere for insights into the everyday lives of ordinary Britons. The records of marriages and births are one particularly rich source illuminating some of the experience of native-newcomer relationships during the inter-war period. Further research into such relationships would aid a more rounded understanding of the period, its complexities and paradoxes, and help fill the gap in our understanding of how ordinary Britons responded to perceived racial difference at a time when the empire was at its fullest extent.

Featured image: “Hands, Ring, Hand, Fingers, Female Hands, Engagement” by MarinaVoitik. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Inter-racial relationships laid the foundations for immigration in Britain appeared first on OUPblog.

How to write for an encyclopedia or other reference work

From time to time, many of us will have the opportunity to write for a reference work like an encyclopedia or a handbook. The word encyclopedia has been around for a couple of thousand years and comes from the Greek term for general education. Encyclopedias as general reference books came about in the eighteenth century and the most ubiquitous when I was a student was the Encyclopædia Britannica. But there also specialized encyclopedias of linguistic, law, mathematics, cuisine, music, and more. These are sometimes just called handbooks (or yearbooks if they are published annually). And there are encyclopedias of particular geographical areas, such as the online New Georgia Encyclopedia or the Oregon Encyclopedia.

Reference works like encyclopedias are often organized into a taxonomy of categories like biography, events, places, institutions, ideas and theories, the natural world. In the age of the internet, well-balanced coverage is crucial to be sure that all the necessary topics are covered well, not just the most popular ones. Editors debate about the right taxonomy, what topics to include, how many words to assign. They wheel and deal to get the most authoritative writers, and they fret when someone doesn’t come through on a crucial topic.

What should authors focus on?

The first rule is to stay within the word limit, even if you think that your topic deserves more space or than the 500 or 750 or 2000 words you’ve been allotted. Consider it an opportunity to practice the virtue of conciseness.

Draw on existing well-documented research, even if the documentation will not appear in the printed or posted version of an article. Many reference works ask for citations and notes, but use them as in-house tools for the editors and fact checkers—and keep them on file in case there are questions later.

“Blue and Gold Cover Book on Brown Wooden Shelf” by Negative Space. CC0 via Pexels.

“Blue and Gold Cover Book on Brown Wooden Shelf” by Negative Space. CC0 via Pexels.Your audience is the general reader, so imagine someone who is interested in the topic but is also new to it. That means you will want to either avoid technical jargon or unobtrusively explain it. You also-want to have an organization and exposition that suits the topic. It’s easy to fall into a one-size-fits-all formula, but some topics require a chronology of events, others need an explanation of a process, problem, or reasoning, and some topics are best treated with a sense of wonder.

Specific details are your friends. Rather than mention that so-and-so was part of a large family, mention that she had six brothers and a sister. The detail shows the readers and referees you’ve done some homework and keeps the reader from wandering. If you can manage it, and an anecdote or quirky fact. That can make the difference between a memorable snapshot and a mere recitation of facts.

Remember to start strong, with a good lead (or lede as the old school journalists would spell it). Here are some examples from the Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America.

Fudge, typically chocolate but commonly marketed in dozens of flavors, is a candy made by boiling a sugar mixture until it forms a soft ball when dropped into ice water (or reaches 234˚ F to 238˚ F at sea level), then stirring to make a soft candy.

Cream soda is a soft drink whose main ingredients are water, sweetener, and vanilla.

The cucumber, Cucumis sativus, is a subtropical annual originating in India.

Applejack, an American type of apple brandy, was widely produced during the colonial period of American history.

Such openings get readers interested and hint at what is coming next: discoveries, domestication, properties, recipes, cultural impact. With a good lead, much of your work is done.

Encyclopedia and other reference articles are a chance to think about topics that you are already familiar with in a way that makes them teachable. And they can also be a way for you to rethink and expand your expertise–to learn something new and something more. It’s definitely worth the effort.

Featured image: “Encyclopedias: 336/366” by Kevin Doncaster. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How to write for an encyclopedia or other reference work appeared first on OUPblog.

Children behind bars: a look at the American juvenile justice system [extract]

In America today, adolescents are frequently moved from juvenile court to adult criminal court where they can be sentenced with little regard for their age or circumstance. In these adult correctional facilities, they can be exposed to high rates of physical and sexual assault from other inmates or end up held in solitary confinement.

In the following excerpt from The War on Kids: How American Juvenile Justice Lost Its Way, we follow author Cara Drinan as she travels prior to the 2012 presidential election, to visit the first of many of these young inmates whom she would come to know during her research.

I met Terrence on a muggy August morning at the Taylor Correctional Institution (TCI) in Perry, Florida. Perry is about a two- and-a-half hour drive west from Jacksonville on the edge of Florida’s panhandle. Despite its nearly deserted Main Street and depressed feel, Perry is less than ten miles from the Gulf of Mexico and only one hour from the state’s capital. The town has approximately 7,000 residents; the prison can hold nearly 3,000 inmates. TCI employs more than 550 staff members, and a quarter of the town’s residents live below the poverty line. Perry is a prison town, and a Confederate flag greets its visitors.

Months of research had brought me to Perry. As a law professor whose scholarship focuses on criminal justice reform, I’d become especially interested in juvenile justice in 2010. That year, the United States Supreme Court had considered the case of Terrence Jamar Graham, who, at 17, had been sentenced to life without parole for his involvement in an attempted robbery of a barbeque restaurant. The Supreme Court, in Graham v. Florida, held that life without parole sentences for juveniles who commit non- homicide offenses are cruel and unusual— that they violate the Eighth Amendment. As a result, Terrence was entitled to a new sentencing hearing and ultimately received a 25-year sentence.

After months of researching and writing about the Graham case, I had decided that I needed to meet the young man at the center of the Court’s decision. I asked Terrence’s lawyer, Bryan Gowdy, who had successfully argued Terrence’s case before the Supreme Court, if I could do so.

Like a good lawyer, mindful of his client’s autonomy, Bryan told me to “ask Terrence.” Terrence and I exchanged letters; he agreed to meet me; the Florida Department of Corrections allowed me to schedule a visit; and several months later, my visit day had arrived.

The night before my scheduled visit, I had landed in Jacksonville and driven to Perry, wanting to be on time for my 9 a.m. slot the next day. Thirty minutes outside Jacksonville the landscape grew sparse. I shifted back and forth between radio static and a half-audible talk radio host ranting about President Barack Obama. With the 2012 presidential campaign at fever pitch, the host declared that Clinton had been our first black president and that Obama was our first gay president because he supported the “gay Gestapo.”

I reached Perry at dusk. As I wound along a narrow residential road heading into the center of town, I was struck by the beauty of its huge oak trees and dangling Spanish moss. At the same time, two images from that short stretch have stayed with me. First: a man coming out of a trailer home, picking up a small dog by the neck in a terribly cruel manner. I looked away, fearing what was to come. Second: a closed-down store that advertised “gun alternatives.” This was a town that had seen more prosperous days.

After a fitful night’s sleep at the Perry Holiday Inn Express, I woke early and drove the short distance to the prison. TCI comprises three separate facilities, and I visited them all before reaching the right one. Walking toward the gates of each facility, I was conscious of the men who were already out and about working in the prison yard under the merciless sun and the supervision of guards. The inmates were black; the guards were white. It had rained the night before, so everything was damp, and with the growing heat, a mist rose from the concrete. The air smelled like the coat of a wet dog.

Before beginning the security process, I left all valuables in my car— cash, laptop, phone. I was allowed to bring in my audio recorder, a pad of paper, and a pen. The metal detector beeped loudly at me. After several passes, I suggested to the skeptical- looking guard that my underwire bra might be causing the problem. I took off my light suit jacket at his instruction and stood there awkwardly in my bra and tank top. He waved the wand over me again. “Yup. It’s the bra,” he said. As I hurriedly got my jacket back on, he looked at me sternly and said: “keep the jacket on.”

The guard led me to the interview room and handed me a small, cigarette-pack-shaped alarm. There was a single button on it. He said to me casually: “call if you need me; press the alarm to call for more people if there’s an incident.” He didn’t describe what would constitute an incident. The “interview room” was closer to a storage closet than a room. Approximately three feet by five feet with a door on each side, strangely, the room had a sink on one wall. Someone had set up a scratched, shaky card table with two folding chairs. I was led into the space through one door (that was left open), and the door opposite me was open, as well. I was told that Terrence would be brought in through the opposite door. Where was he coming from? What would he look like? Would the guard escorting him be polite? Was I being recorded? My mind raced as I set up my recorder and waited for Terrence to arrive. The room was dirty.

My pre-interview jitters disappeared when Terrence was led into the room. He was my height, trim, and well groomed. Terrence had kind, deep brown eyes, and he was incredibly polite. I began by asking him to describe his typical daily routine, and after that question, I never relied upon another one that I’d drafted in advance. We just talked— about his life in prison, his family, and how he passes the time. When several hours had passed, I knew I should be heading back to Jacksonville— I was scheduled to present a paper at an academic conference hours away. I felt sad and guilty leaving. I promised Terrence we’d stay in touch, and that I would be back. I had to say it, and I felt like he needed to hear it. As I packed up my things, I asked Terrence if he knows what he’ll do when he’s released. He didn’t miss a beat: “first I gotta make it outta here.”

Featured image credit: “barbed-wire-wire-fencing-defense” by Maaark. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Children behind bars: a look at the American juvenile justice system [extract] appeared first on OUPblog.

Engendering communication – Episode 42 – The Oxford Comment

In a constantly changing world, it’s only natural that language continues to evolve as well. Words or phrases that no longer apply are phased out and in their place emerges lexicon that better reflect the diversity of gender, race, and sexuality in contemporary culture. From under-privileged children being taught how to read at home with cookbooks, to groups of students who adopt the use of new words to better explain experiences they see in their own communities, educators are also recognizing the need to understand how changing culture influences the way students of different backgrounds speak.

In this episode of The Oxford Comment, we chatted with SJ Miller, Deputy Director of Educational Equity Supports and Services at the NYU Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools; and David E. Kirkland, author of “Black Musculine Language” from The Oxford Handbook of African American Language, and Executive Director of the NYU Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools; to discuss the developments we’re seeing in today’s English lexicon and how we can positively incorporate linguistic change instead of dismissing it.

Featured image credit: Microphone by BreakingTheWalls. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Engendering communication – Episode 42 – The Oxford Comment appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers