Oxford University Press's Blog, page 297

November 25, 2017

In memoriam: Ray Guillery

7 April 2017 brought with it the sad passing of Ray Guillery FRS, celebrated neurophysiologist and neuroanatomist, world leader in thalamo-cortical communication, and Dr Lee’s professor of anatomy and fellow of Hertford College, Oxford, from 1984 to 1996. Dr Lizzie Burns kindly shares her memories of working with Ray on his final book, The Brain as a Tool, for which she was the illustrator.

I first met Ray by chance when I ran a workshop for the ‘Cortex Club’ inspired by the Nobel Prize winning Oxford neuroscientist, Sir Charles Scott Sherrington. The workshop used Sherrington’s poetic words to inspire new connections and promote neuroplasticity – or in the words of Sherrington, to ‘teach the best attitude as to what is yet known’. Ray warmly embraced the opportunity to use modelling material to explore making structures of the brain and asked if I might be interested in creating some illustrations for his book: The Brain as a Tool.

Out of all my collaborations over the past 15 years combining science and art, this involved the most continuous dialogue and engendered the most enduring relationship. Ray was keen to share some of the vast, detailed knowledge he had accrued during his lifetime studying the brain. As someone who had already been creating some artwork about the brain for the Medical Research Council over a decade ago, this sparked a continued fascination for me too, and so I relished this opportunity to learn from Ray and committed myself to creating illustrations. I hoped I could bring to life the beauty of our most complex and essential organ.

While rigorous, Ray also showed that curiosity and playfulness are essential in how we engage with the world

Ray started by showing me some preserved and plastinated brains he used for teaching medical students and neuroscientists. We both shared a strong admiration for the observation and beauty from the old masters of neuroscience, including the Spanish scientist Santiago Ramon y Cajal, and I was fascinated to see the beautiful drawings from Swiss anatomist Albert von Kolliker who had studied in Ray’s birth country of Germany. We also shared distaste for so many current medical illustrations with their airbrushed, artificial, and life-less feel. Rather than looking at illustrations from others, we instead looked at the real specimen, both preserved and via photos of the fresh human brain.

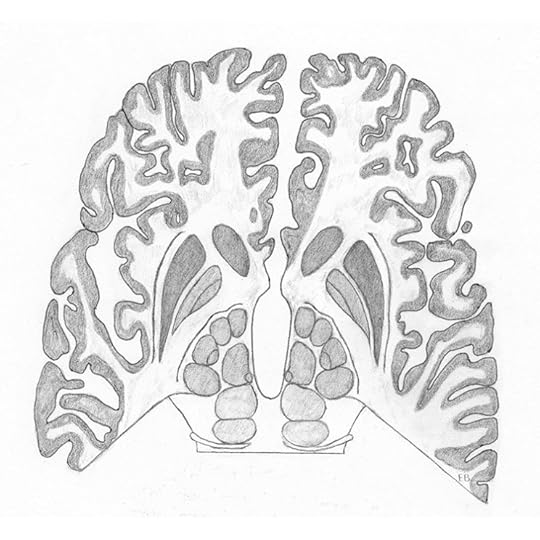

I started enthusiastically sketching what I could see, and Ray kindly guided me towards improvement with great patience and encouragement. They started scratchy and hazy but with time, these images evolved to become stronger and 3-dimensional in feel, though still delicate in appearance. He started to help me see with photos of specimens that no single image would show each area in the way he knew it could be, and that the book would need an artist to render each area together in one holistic image. In Ray’s mind, he knew how they all related and how the perfect specimen would appear. Each image I started to draw was corrected and shared, and we would send them back and forth and meet up to discuss. As Ray had such an eye for detail, getting to the point where he was satisfied and pleased meant a lot. Ray studied vision, and felt the illustrations would make a difference to his book. I hope they do.

Reading Ray’s book while trying to render the exquisite beauty and complexity of the brain gave me an excited feeling of glimpsing the mind-boggling complexity of circuits, connections, and comparisons being made in any particular moment of time. I found a new appreciation for this particular part of our body which is so hidden. We can hardly comprehend what we are, and so it felt right that the images were not simple or quick to create but born of so much thought and care, the same kind that Ray gave in writing his book. While rigorous, Ray also showed that curiosity and playfulness are essential in how we engage with the world, to see what we are in fresh new ways. I wanted to share some of Ray’s beautiful drawings and include a playful image he drew of looking at the world upside down through your legs. He explained there’s a reason the world looks different this way up, and I hope you can enter his book and see the world afresh too.

Ray Guillery

Image from the Anatomical Neuropharmacology Unit at the University of Oxford where he was an Honorary Emeritus Research Fellow

Sketch of a ventral view of the human brain

Sketch of the view of some of the major parts of the mamillothalamic and mamillotegmental connections, with comments from Ray Guillery

The completed illustration of the major parts of the mamillothalamic and mamillotegmental connections in the brain

Illustration by Ray Guillery

‘I wanted to share some of Ray’s beautiful drawings and include a playful image he drew of looking at the world upside down through your legs. He explained there’s a reason the world looks different this way up, and I hope you can enter his book and see the world afresh too’ – Dr Lizzie Burns

A lateral view of the human brain

Summary figure of some of the connections that link the subcortical, phylogenetically old motor centres of the brainstem and spinal cord to the thalamus and cortex

A figure based primarily on experimental studies of the rabbit, showing the connections formed between the somatosensory cortex, the posterolateral thalamic nucleus, and the thalamic reticular nucleus

A schematic view of the major visual pathways as seen in relation to a ventral view of the cerebral hemispheres

A horizontal section through the human brain to show the richly folded cerebral cortex and some of the internal structures of the brain

Featured image credit: An inferior and sagittal view of the human brain by Dr Lizzie Burns. Used with permission.

The post In memoriam: Ray Guillery appeared first on OUPblog.

Beer and brewing by numbers [infographic]

Beer has been a vitally important drink through much of human history, be it just as a drink that was safe to consume when water might not have been, through to having significant economic and even political significance.

The earliest written laws included regulations on beer, tax income from beer funded centuries of British imperialist conquests, and beer is the subject of the oldest international trademark dispute — between the American Budweiser and Czech Budweiser Budvar. The industrial and scientific revolutions had a profound impact on the beer brewing industry, and while for many years cheap and reliable lagers were the tipple of choice, we are now in the midst of a craft beer revolution against industrial brewing. Beer is a lens, or glass if you will, through which we can look at the history of the world and maybe better our understanding, but only until the third pint.

Take a look at some more fun beer facts and figures in our infographic below, with content taken from Beeronomics: How Beer Explains the World.

Download the infographic as a PDF or JPEG.

Featured image credit: Beverages Beer Box Bottle by maxmann. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Beer and brewing by numbers [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

November 24, 2017

In the zone: how balancing stress levels improves performance [excerpt]

Balancing stress is easier said than done. A low-stress state can lead to apathy, while a high-stress state can lead to anxiety. However, being in the right “zone” of stress can lead to peak focus and productivity. In the following excerpt from Boost!, Michael Bar-Eli discusses how applying sports psychology to the workplace can optimize employee performance.

Athletes’ maximum performance, also known as peak performance, is often characterized or accompanied by what is called a “flow state” or “peak experience.” Athletes describe this state as being “on automatic pilot,” “totally involved,” “hot,” “on a roll,” “in a groove,” or “in the zone.” An excellent example is provided by the great German goalkeeper Oliver Kahn in the 2001 champions league final game, between his team FC Bayern Munich and FC Valencia.

In the shootout that won the game, he saved three of seven penalty kicks, or 42.86 percent. Even if you count the penalty he did not stop during the game, this makes it three out of eight, which is 37.5 percent— still far beyond the base rate (that is, the initial chances of a goalkeeper saving a penalty kick to begin with) of 25 percent. He attributed his success to “a state of absolute concentration, with optimal control over my emotions and thoughts.”

A flow state, however, is a rare event—it is an ideal state to which the performer strives, but only infrequently achieves. This is probably one of the reasons why Russian sport psychologist Yuri L. Hanin criticized the Yerkes-Dodson law’s inverted-U hypothesis by arguing that it is unlikely that only one optimal arousal state exists that corresponds with the maximal performances of different athletes across contexts. He used a well-known anxiety test, the state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI), developed by the late US psychologist Charles D. Spielberger and his team, to operationalize arousal. He then conducted systematic retrospective multiple field observations of athletes’ state anxiety and performance levels.

Hanin found that all top athletes had an individual zone of state anxiety in which their maximal performance occurred, whereas poor performances occurred outside this zone. He defined this zone as an athlete’s mean precompetitive state anxiety score on the STAI, plus or minus four points (which is a standard deviation of approximately 0.5), and labeled it the zone of optimal functioning (ZOF).

Later on, Hanin extended this idea to include more emotional states and emphasized the individuality of the ZOF (IZOF). What matters for us now, however, is the fact that most of the time, we sport psychologists are satisfied with our athletes being in their (I)ZOF; if they manage to achieve a flow state it would be a great bonus, because of its low probability of occurrence.

Now, if you combine the main ideas reflected by Yerkes-Dodson and Hanin, you actually get two possible non-optimal arousal states for athletes to be in, and two corresponding strategies for enhancing performance to strive for the maximum:

Too-low arousal, in which “more is more” would be the right strategy—the athlete is advised to increase arousal to try and create optimal conditions.

Too-high arousal, in which “less is more” would be the right strategy—the athlete is advised to decrease arousal to try and create optimal conditions.

The same applies of course in other settings as well, such as when you take an exam or interview for a job. If you are tired, apathetic, or simply indifferent, your arousal is probably too low and somebody has to wake you up. However, if you are too tense, anxious, or pressured, then your arousal is probably too high and you need to relax.

Your natural personality also plays a substantial role: for example, if you are a nervous versus relaxed person, or Type A versus Type B. Type A people are those who are achievement- oriented and highly competitive, have a strong sense of time urgency, find it hard to relax, and become impatient and angry with delays or when confronted with people whom they perceive as incompetent. Type B people are able to work without becoming agitated, and to relax without feeling guilty. They have less of a sense of time urgency—including its accompanying impatience—and are not easily roused to anger.

Your level of expertise plays a role, too—it makes a big difference whether you’re a seasoned professional or a novice. Starting out in the corporate world, as an assistant, you are likely to defer to more experienced coworkers who have a better understanding of company processes, interoffice politics, or a particular industry in general. There is nothing wrong with that, but understanding your strengths and weaknesses will help you figure out how to reach your own level of peak performance.

In finding your or your team’s optimal level of stress and arousal, the environment should also be taken into consideration. The environment that managers and bosses create and cultivate is crucial to employee performance. For example, would you experience more of a threat in a stadium full of 80,000 spectators, as compared to training, or do you revel in it, as did Daley Thompson and Anat Draigor? Understanding and knowing your team, and the individuals that comprise it, will help you create the appropriate environment.

An example of an open-plan office layout. Credit: “OpenPlanRedBalloon1” by VeronicaTherese. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

An example of an open-plan office layout. Credit: “OpenPlanRedBalloon1” by VeronicaTherese. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Consider open-plan offices: at the beginning of the twenty-first century, we find more traditional cubicle structures being eschewed in favor of these new arrangements. As of the end of 2014, about 70 percent of US offices had no or low partitions. Such settings, in which the emphasis is on large, open spaces with little to no barriers between desks and offices, were at first seen as an exciting new way to break from the typical cubicle mode in an effort to raise transparency, camaraderie, and teamwork. Companies like Google, Facebook, Yahoo, eBay, Goldman Sachs, and American Express have all implemented the idea.

What many people didn’t foresee were the accompanying issues of high levels of noise and the lack of privacy, all of which have led to greater stress on employees—and not the good kind. Research over the last decade has shown that open office design is negative to employees’ satisfaction with both their physical environment and perceived productivity.

At the end of the day, it’s important to decide what environment will be best for the team to increase performance—finding that sweet spot may be difficult, but it will lead to a stronger, more successful workforce. If your employees are uncomfortable and stressed out, they are likely to reach that too-high arousal stage and their performance will suffer. As a leader, you will then need to figure out how to decrease that stress and get your team back to its zone of optimal function.

Featured image credit: “man-doing-boxing” by Pixabay. CC0 via Pexels .

The post In the zone: how balancing stress levels improves performance [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

Engaging with history at #OHA2017

For most Americans, Thanksgiving is a time to give thanks for all of the best things in life: family, friends, football, and, of course, heaps of delectable food. Few care to spend any time thinking about the myths that underlie American perceptions of the holiday, and even fewer can appreciate how and why this holiday is frequently observed as a day of mourning among many Native Americans. Protests at Standing Rock and throughout the football world have made it much more difficult to sweep the histories of historically marginalized groups under the rug this holiday season. This year, Thanksgiving and its commonly espoused “theology of divine abundance” will not be enough to obscure the histories of inequality and violence America was founded upon.

Like these protests, the presentations I attended during the Oral History Association’s 2017 annual meeting delivered critical historical narratives and resources that can help us to further challenge some of the nationalist myths that obscure the experiences and perspectives of various marginalized communities in American history. These presentations helped to illuminate important lessons we can learn from an engagement with the histories and contemporary concerns of marginalized peoples in the US. In honor of the holiday season, I have put together a short list of what I was most thankful for during OHA2017.

1. OHA 2017 Keynote Address: Jill Lepore, “Joe Gould, Augusta Savage, and Oral History’s Dark Past”

I think most OHA2017 attendees would agree that the real star of Jill Lepore’s keynote address, in addition to Lepore herself, was Augusta Savage. Though Lepore’s talk (and the book it draws on) focused largely on Joe Gould, the ostensible father of oral history, conversations during the Q&A that followed her lecture focused almost exclusively on Augusta Savage and Lepore’s allusions to the years of physical and sexual violence she suffered at the hands of Joe Gould. And, perhaps even more significant was Lepore’s assertion that there were a number of important men involved in protecting Gould from facing any legal consequences for his violent acts against Savage. This story has begun to ring loudly in my ears as a number of influential men in Hollywood–long protected by their status and associations with other prominent men in the business–tumble down from their pedestals in the face of women who have been inspired to tell their stories by campaigns like #MeToo. Serendipitously timely, Lepore’s, address helps to advance our knowledge on the subject of women, sexism, and (sexual) violence in American history just as we–as a nation–are finally beginning to grapple with the knowledge that women are subjected to wide-spread and largely accepted forms of sexual harassment and sexual violence on a daily basis. As we begin to deal more fully with this reality and all of its (un)intended e/affects, it will be important to earnestly reflect on how race plays a role in shaping women’s (and men’s) experiences with sexism and sexual violence, and stories like Savages’ will provide us with a critical starting place to do this work.

When learning is a two-way street, oral history stories have the power to change the present.

2. Roundtable 065. Documenting Activism in the Age of #BlackLivesMatter and Standing Rock

Everything about this roundtable was superb, however, what I want to share with readers here are links to some of the oral history focused resources roundtable participants have played key roles in establishing for public consumption. These resources would be great sources of information for teachers and researchers alike:

The Documenting the Now project works to ethically collect and preserve “the public’s use of social media for chronicling historically significant events,” and is supported jointly by the University of Maryland, University of California, Riverside (UCR), and Washington University in St. Louis.

Inside the Activists Studio (IAS) is a web-based series that is easily accessible via YouTube and takes inspiration for the interview-styles of the popular television series “Inside the Actors Studio.” Each episode features an interview with activists about their own “political awakening and biography of activism” and is posted online for free and easy access (at least for those with access to a computer and internet).

Invisible to Invincible: Asian Activism in MN, a short documentary film available on YouTube, works to unpack the model minority stereotype while also exploring the history of Asian activism in Minnesota and the US more broadly.

3. Panel 091. Oral History and Critical Pedagogies

Each of the papers presented during this panel were extremely different in their content and subject matter, some presenters sharing insights from their university based institutional ethnographic work and others discussing the use of family oral histories to destabilize neoliberal pedagogies; however, these presentations were tied together by a few underlying ‘truths’ about the significance of oral history to developing critical pedagogies. First, the theme of lost knowledge and/or obscured stories came through in all three papers, as did the real ways that oral history can be used as a tool to bring light to ‘lost’ knowledge or stories of the past. Perhaps more significant, however, are the ways in which each presenter showed us exactly how and why it is so important for teachers, academics, and activists to learn from the communities they work within. In bringing the methods, theories and tools of oral history research into the classroom and other educational spaces, these presenters were able to show us how giving students and teachers the opportunity to bring parts of themselves into their learning environments can enable them to work together to build solidarity and new forms of identity. Thus, the most important truth to be gleaned from the presenters on this panel: When learning is a two-way street, oral history stories have the power to change the present.

What are you thankful for this year? Chime into the discussion in the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Featured image credit: ‘Demilitarize the Police, Black Lives Matter’ by Johnny Silvercloud, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Engaging with history at #OHA2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

A composer’s Christmas: Alan Bullard

Alan Bullard has written many well-loved carols and Christmas works and edited a number of volumes of Christmas carols. To mark the start of the Advent season, we asked him to tell us a bit about his Christmas traditions and what it is about Christmas that inspires his writing.

What’s your favourite thing about the Christmas season?

The Christmas story: it may not have actually happened quite as described, but its message still reaches out to us in so many ways.

Is there anything about Christmas that particularly inspires your composing?

Yes. Although many composers find themselves involved in Christmas-related activities for much of the year, there is something about the dark nights, the decorated houses and churches, and the Christmas message of peace and friendship, that concentrates the mind on the composition of Christmas music. Having said that, I wrote one of my most popular carols on a hot summer’s day!

What marks the beginning of Christmas for you?

Advent Sunday.

What’s your favourite Christmas film and why?

Not really a Christmas film – but watching Marx Brothers films at Christmas with the family has always been a delight.

Alan Bullard at Christmas. Used with permission.

Alan Bullard at Christmas. Used with permission.What’s your favourite Christmas carol and why?

There are so many! A traditional one would be the Polish folk-carol ‘Infant Holy, Infant Lowly’ with, although it was probably a transcription error, the fall of a third in the in the final bar (not the straightened-out version in NOBC). It has a lovely simplicity and a sequence to die for in the middle section.

My favourite twentieth-century carol would be Herbert Howells: ‘A Spotless Rose.’ Howells was my teacher at the Royal College of Music and it’s lovely to remember him in this way, with this freely-flowing and expressive work.

Which one of your own Christmas works are you most proud of and why?

This is hard to answer – but if I had to choose just one it would be ‘Scots Nativity’ for its gentle simplicity and melodiousness, which I’ve never quite been able to replicate.

Are there any seasonal activities that you particularly enjoy doing?

The opportunity to celebrate with friends and family, children and grandchildren. And to sing and worship in Christmas services.

What does a typical Christmas day look like for you?

A typical Christmas day for me starts with attending a midnight service. Then, in the morning, presents, a walk, a light lunch, perhaps another walk, then food preparation, Christmas dinner in the early evening, games, and carols.

Why do you think music is so important to people at Christmas time?

Christmas carols and songs have become part of our folk heritage, and are embedded in so many people’s memories from schooldays that their words and music become a nostalgic evocation of the past as well as a vision of peace for the future.

Featured image credit: Church window by Falco. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post A composer’s Christmas: Alan Bullard appeared first on OUPblog.

November 23, 2017

Rethinking the singalong

When two young veterans came to our elementary school to give a talk and show slides about their experience in Afghanistan, the children were captivated with their presentation. The slides brought to life much of what the soldiers saw and experienced. As the music teacher, I planned to have the children say thank you in a musical way. I didn’t choose a patriotic song, but a song that exemplified the love and appreciation we all had for these soldiers. I chose one song that the entire student body of the school could sing together.

In preparation for this event, we practiced a song called “Still in My Heart” by Teresa Jennings of Music K8 Magazine. With help from another teacher, I figured out the sign language and taught it to all my classes.

After the soldier’s presentation, I announced we would like to thank them for coming as well as thank them for their service. The entire student body stood up from their seats and sang the ballad with the sign language and accompaniment. The lyrics included words like, “Still in my heart you are, still in my mind, still in my dreams, forever.” For the grownups, it was difficult to keep a dry eye, and the veterans appeared moved. My hope is that everyone in that room remembered the love radiating through the air.

Although it was not technically a singalong, the act of a whole student body singing together and sharing feelings and togetherness hopefully gave a wonderful memory. This assembly benefited from a sincere and directed use of ‘song’ to connect. “Connecting” is also one of the new core arts music standards.

What I am proposing is that you purposefully put the singalong into a different category in your mind. Instead of the category music activity put it into the category ‘community.’ The traditional singalong in the 1950s which emphasized the folk song is only one type. As you rethink the singalong, imagine a scenario in which every person in the room or auditorium is thinking “I am here with you.” Activities such as moving all the same way, saying the same words, listening together, and singing the same song are all examples of taking part in something bigger than you.

Photo credit: Used with permission of Kim Milai.

Photo credit: Used with permission of Kim Milai.Music is interwoven into the school’s calendar. It is not just a fill-in activity or even a once-a-year event. The music teacher can be a leader in carving a stronger niche for music within the social structure of the school. For example, you could include an activity within the singalong in which each class or grade shares something different. During this show and tell, each grade takes their turn to sing a song or demonstrate a music activity they learned to the remaining group.

Singalongs can too easily go on automatic, especially if they are well-known songs. They need a teacher trained in proper singing to guide it. Singing “Jingle =Bells” as a group works much better if the children are not screaming the refrain!

You may love standard singalong songs (as I do) like “This Land is Your Land,” by Woodie Guthrie, but also be open to different types of music. Bring in songs from different countries, in different languages. If the language is too ‘difficult’, then let the group sing just the refrain and you sing the verses— but it needs to be purposeful. Ask yourself, what are we communicating to each other?

With surgical precision, the music teacher needs to create both a relaxed and fun atmosphere, but also challenge everyone to not be shy and open their mouths and sing. Look around the room. Are the teachers singing too? Are the students singing and not yelling?

Here is one example. Not every music teacher would be comfortable with this, but during an assembly, I was known to briefly stop the singing and interject some brief instructions to improve the performance. I believed in occasionally using the assembly as a giant classroom. I often would talk to the kids in the audience like we were having a private talk. I would stop to explain how we could communicate the words better and ask them to try again. Sometimes I would conduct a vocal warmup with the whole group in front of their teachers. This was my way of keeping it informal while keeping the quality of the singing high.

The singalong can be the expression that pulls the group together. On the practical end, it was essential I got administrative permission for the song I was going to do and to lock in the stage setup. For the following example, I got permission to use a specific song for an upcoming assembly. In the classroom, we spent time discussing the song’s history and why its use of slang was so important.

I used what I like to call the power of the voice. It’s basically voice projection. It’s something you often hear during a sermon or a speech from an important speaker. While we were honoring the local civil rights matriarch present at our assembly, I introduced a song in which the student body sang the refrain. But I introduced it not by making a speech or just starting to sing. For the song introduction, I held the microphone and respectfully exclaimed, “Ain’t gonna’ let NOBODY turn me round!” By using this unexpected introduction, I had everyone’s attention. I then explained that this song was a powerful protest song when people marched for civil rights in the early 1960s. I cued the students to be ready to sing “Turn me round, turn me round, turn me round…keep on a-walking, keep on a-talking, marchin’ up to Freedom Land.” When I started singing and the student body chimed in for the refrain, it became a “we are all together” moment.

The power of the voice became the power of the song, and as a result, accomplished the connection of the people, all through singalong.

The power of the voice became the power of the song, and as a result accomplished the connection of the people.

Featured image:

Day 240: Classroom in Korea” by Cali4beach. CC by 2.0 via

Flickr

.

The post Rethinking the singalong appeared first on OUPblog.

Thanksgiving traditions from Oxford University Press [slideshow]

To celebrate Thanksgiving this year, we’ve asked Oxford employees to share their holidays traditions. Referencing The Oxford Companion to Food, we put together a slideshow of fun food facts to accompany some of our favorite traditions.

Nuts

“Growing up, we’d always have Thanksgiving at my aunt and uncle’s house, and after the meal and deserts, when the men went and slept (err, watched football), my aunt would bring out this big bowl of nuts, and she and my mom, cousin, grandma, and I would just sit around the table cracking and eating them. We haven’t had them in a while – may have to bring them back this year!” -Alyssa R.

Nuts are highly nutritious. Some contain much fat (e.g. pecan 70 per cent, macadamia nut 66 per cent, Brazil nut 65 per cent, walnut 60 per cent, almond 55 per cent); most have a good protein content (in the range of 10– 30 per cent); and only a few have a very high starch content (notably the chestnut, ginkgo nut, and acorn). The water content of nuts, as they are usually sold, is remarkably low, and they constitute one of the most concentrated kinds of food available. Most nuts, left in the shell, are also remarkable for their keeping quality, and can conveniently be stored for winter use.

Flan

“Every Thanksgiving, my father and I cook Cuban food to add to the meal my mother and her sisters prepare. This creates for an interesting dinner combination since my mother’s family always cooks traditional, African American comfort food. Cuban food is very savory (and the flan I make for dessert is very, very sweet!) so sometimes it’s just the two of us who eat it, but it’s worth it and makes the holiday a little more multicultural.” -Celine AR

Flan is a term with two meanings. The one most familiar in Britain is: ‘An open pastry or sponge case containing a (sweet or savoury) filling.’ In France the term flan carries the first meaning described above, but often has the second meaning: a sweet custard which is baked in a mold in the oven until set. The second meaning is the one which is used in Spain and Portugal, where flan is a standard dessert, and in many countries, e.g. Mexico, where either language is current. In the USA what bears the name flan in Britain is likely to be called tart or pie.

Cranberry

“I would like to pass on this atrocity” -Daniel L.

The cranberry is the most important of the berries borne by a group of low, scrubby, woody plants of the genus Vaccinium. These grow on moors and mountainsides, in bogs, and other places with poor and acid soil in most parts of the world, but are best known in Northern Europe and North America. All yield edible berries. When the Pilgrim Fathers arrived in North America they found a local cranberry, V. macrocarpon, which had berries twice the size of those familiar to Europeans, and an equally good flavour. It was no doubt these large American cranberries which, at an early stage in the evolution of Thanksgiving Day dinner, were made into sauce to accompany the turkey, which became established as its centrepiece.

Pumpkin

“Each year my aunt and uncle take their pumpkins from Halloween and make pumpkin pies to give out at Thanksgiving to our family.” – Mackenzie C.

The pumpkin is a large vegetable fruit, typically orange in colour, round, and ribbed, borne by varieties of the plant Cucurbita pepo, one of four major species in the genus Cucurbita. The name is thought to derive from an old French word pompon, which in turn came from the classical Greek pepon, a name also applied to the melon. When pumpkin is used in sweet dishes, spices such as ginger and cinnamon are commonly added. This practice goes back a long way. For example, American pumpkin pie, a main feature of the American Thanksgiving dinner, may have been derived from old English recipes for sweet pies using ‘tartstuff’, a thick pulp of boiled, spiced fruit.

Crumble

“My family isn’t much for a huge sit-down meal on Thanksgiving. Instead, we spread out tons of cheese and crackers, fruit, and appetizers on the living room coffee table, set up a TV, and watch all the Thanksgiving episodes of F.R.I.E.N.D.S. Then, for dessert, we have something special like pumpkin cheesecake or apple crumble while watching a Christmas movie.”- Heather S.

Crumble is the name of a simple topping spread instead of pastry on fruit pies of the dish type with no bottom crust, such as are popular in Britain. Crumble is much quicker and easier to make than pastry and it seems probable that it developed during the Second World War. It is like a sweet pastry made without water. The ingredients of a modern crumble are flour, butter, and sugar; a little spice is sometimes added. The butter is cut into the dry ingredients, and the mixture spooned onto the pie filling without further preparation, after which the pie is baked. The butter melts and binds the solid ingredients into large grains, but they do not form a solid layer like a true pastry. The texture can only be described as crumbly. Apple crumble is probably the best-known form.

Turkey

“A few years ago when I was living in Cairo, my English flatmate went to great lengths to procure a turkey for me as a surprise, because after all it’s not really Thanksgiving without a turkey. When the butcher she went to had no turkey (of course—it’s an unusual bird in Egypt), a butcher shop employee went off on a mission through Cairo for her and finally returned with a 26-pound frozen turkey strapped to the back of his motorbike, unpackaged but for the black 40-gallon trash bag in which it was loosely wrapped. It was about twice the size of our oven, but once we managed to cut it into pieces and roast it, the breast meat alone fed fourteen people with leftovers, and we made gallons of turkey soup with the legs. It’s one of the best Thanksgivings I’ve ever had, even if it took me a few years to want to eat turkey again.” – Lucie T.

Turkey was originally a prefix to the terms cock, hen, and poult (a young bird), but now stands on its own and denotes the species Meleagris gallopavo. Native to North America, these birds are now farmed and used for table poultry around the globe. In 1609 the inhabitants of Jamestown, reduced almost to starvation, were kept alive by gifts of wild game, including ‘turkies’, from the indigenous population. Wild turkeys were served at the second Thanksgiving dinner in 1621, and may have featured in the first, of 1620.

Cheese

“My parents have the Thanksgiving meal covered. Like really covered. So as I got older and wanted to find some way to contribute, I decided that the afternoon snack (because no one really eats lunch on Thanksgiving at our house) was going to be my contribution. So now, in the days before Thanksgiving, I comb all the cheese shops of Brooklyn to find new and interesting cheeses, olives, whatever looks delicious for snacking. It’s the tradition I made for myself.” – Sarah R.

Cheese is always made from milk but is in other respects of great variety. Its taste may be almost imperceptible, as in some fresh cream cheese, or very strong, as in the most aged blue cheeses. The texture, which depends largely on water content, can be virtually liquid or dry and friable. The fat content ranges from 1 per cent to 75 per cent. The earliest traces of milking come from milk residues in potsherds from north-western Anatolia dating as far back as 6000 BC. Cave paintings in the Libyan Sahara dating from 5000 bc show what might be cheese-making going on in prehistoric Northern Africa. These remains antedate what archaeologists now call the ‘secondary products revolution’, when domesticated animals were exploited for their renewable resources. That profound shift in husbandry practice, estimated to have occurred in the Near East in about 3500 bc, means that it is no surprise that the ancient Sumerians and Egyptians made cheese. Cheese was also familiar in pre-classical Greece, as we know from Homer’s description of Circe serving cheese to Odysseus, and it was a staple food of classical Greece and Rome.

Featured image credit: “mushrooms-tomato-plate-pot-red” by Engin_Akyurt. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Thanksgiving traditions from Oxford University Press [slideshow] appeared first on OUPblog.

Animal of the month: badgers at Wytham Woods [video]

Distinctive and familiar, loved and loathed by different sections of the public, the badger is iconic of the British countryside. But Oxford University’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU) has discovered that, due to their sensitivity to prevailing weather, badgers, like the proverbial canary in a coal mine, are also sentinels of climate change.

Led by Professor David Macdonald, the WildCRU team has studied the intricacies of badger society for over 30 years at Wytham Woods, Oxford’s famous ‘laboratory with leaves’, where, for all practical purposes, Charles Elton invented the science of Ecology in the 1930s. From this meticulous record of all their births, deaths, and marriages, it has emerged that badgers, like Goldilocks, prefer things (well, the weather rather than porridge) to be ‘just right’. If summers are too dry they are unable to find sufficient earthworms, their main prey. But if summers are too wet, badgers get sodden, and prefer to stay underground in their setts if it rains hard, costing them energy and foraging time. Notably too, it is cubs that are most vulnerable to severe weather, as they simultaneously grapple with rapid growth and juvenile infections; exemplifying how populations are only as resilient as their weakest link.

Frost also precludes earthworm availability, although badgers have evolved to cope with a paucity of wood over winter, using periods of torpor to conserve energy. In this regard, initial research found that milder winters were broadly beneficial to badger success, until ever-more benign conditions tempted badgers to wander much further on dark, foggy nights, tragically leading them to fall victim to road traffic accidents in far greater numbers.

Macdonald’s team has also tracked individual badgers with the latest technology, able to measure how the pitch, yaw, and roll of badger motion translates into energy expended. Again, there is subtlety to their findings, because while more corpulent badgers are risk averse, only leaving their setts to forage under optimal conditions, thinner, more desperate badgers do not have this luxury, and would rather die on their feet than in their beds, and venture forth in much less promising weather. Of course, who’s up and who’s abed also affects which badgers can be trapped, or monitored by the group’s video surveillance. Modelling these data reveals that the proportion of the population caught is, accordingly, a product of prevailing weather. This is important not only in making accurate population estimates but, in the case of badgers, highly pertinent to the timing of interventions to cull or vaccinate badgers, as part of national policy connected to TB management.

In collaboration with colleagues in Scotland and Ireland, research has also revealed biogeographic patterns with weather via food and energy budgets, limiting which areas of peripheral habitat badgers occupy. With predicted warming patterns improving weather conditions this will likely lead to more badgers and spreading populations in these regions, although there are risks that this could bring them into greater conflict with farming, development, and traffic.

And so with 2016 the warmest year on record, and with CO2 levels exceeding 400 ppm through 2017, the badger is providing valuable insights, exemplifying the vulnerabilities, and adaptiveness of animals struggling to survive in human-modified habitats subject to human-modified weather.

Elderly badger, eating.

Cubs near sett entrance.

Video still of badgers at sett, from infra-red surveillance.

Sedated cub being handled (‘in denial’).

David Macdonald and Chris Newman with sedated badger.

Badger with fur clip (dark guard hair trimmed to reveal white under fur) for visual ID under surveillance.

Former student Simon Sin releasing a badger after sedation and handling back at its home sett.

Christina Buesching (centre) with her current doctoral students Tanesha Allen (left) and Nadine Sugianto (right).

David Macdonald, examining badger latrine.

All slideshow images used with permission from authors and students.

Featured image credit: Wytham Badgers Video Stills #2 by Hannah Madsen. Used with permission.

The post Animal of the month: badgers at Wytham Woods [video] appeared first on OUPblog.

November 22, 2017

Nine of diamonds, or the curse of Scotland: an etymological drama in two acts: Act 2, Scene 1

Battles, butchers, and tyrants

“This is what remains of us after every battle.” Image credit: The front facing of the Culloden Cairn at Knoydart, Nova Scotia. Knoydart by Wreck Smurfy. CC by 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“This is what remains of us after every battle.” Image credit: The front facing of the Culloden Cairn at Knoydart, Nova Scotia. Knoydart by Wreck Smurfy. CC by 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.CULLODEN. The battle of Culloden took place on 16 April 1746 between the forces of the Catholic “Young Pretender” Charles Edward Stuart, who was at the head of the Jacobites, and those of the government, led by Prince William, the Duke of Cumberland. Charles Edward is remembered in English history as Bonnie Prince Charles. His army lost the battle, and he died in exile. (Just for information: the duke turned 25 on the day before the battle; his opponent was 26; they were cousins.) Immediately after the battle, rumors circulated that the commander of each side instructed his followers to give the enemy no quarter. The “butcher duke” supposedly wrote his order on the back of a playing card. (See more about this card in last weeks’ post.) No authentic documents or cards confirming the order have been found. Moreover, there is a print, dated 21 October 1745 (that is, published half a year before the battle) that represents “the Pretender attempting to lead across the Tweed a herd of bulls laden with curses, excommunications, indulgences, &c. &c. &c. On the ground before them lies the Nine of Diamonds.” Nothing is said about the possible symbolism of the card, but, apparently, it has something to do with “the curse of Scotland” and suggests that in 1741 the connection between the nine of diamonds and the phrase was understood. The print is entitled “Briton’s Association against the Pope’s Bulls.” The pun on bull “animal” ~ bull “papal edict” is obvious. (We can see the Pretender grasping the horns of one of the group of bulls, while between his feet lies the nine of diamonds. Does another pun allude to taking the bull by the horns?) Some other early discussants confirmed the fact that the nine of diamonds had indeed borne the ominous name before Culloden, though no one knew why.

“This is the print showing horned and other bulls.” Image credit: Briton’s Association against the Pope’s Bulls by Anonymous. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 via The British Museum.

“This is the print showing horned and other bulls.” Image credit: Briton’s Association against the Pope’s Bulls by Anonymous. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 via The British Museum.INTERMISSION: ENTER JAMES A. H. MURRAY (Notes and Queries, 8th Series/III, 1893, p. 367): “In Annandale’s ‘Imperial Dictionary,’ after mentioning, among many other ingenious and baseless guesses, a hypothetical connexion of the card with the Battle of Culloden, the author says, ’but the phrase was in use before.’ I shall be grateful to any one who will send me a quotation or reference for the ‘curse of Scotland’ before Culloden, 1745, or indeed before 1791, when it is mentioned in the Gentleman’s Magazine, p. 141. Jam[i]eson has no quotation, and knew it only as colloquial in the south of Scotland. I have not at present any grounds for thinking that the phrase is of Scottish origin.” Every line by J. A. H. Murray is precious. If I were a rich independent publisher, I would bring out two volumes: The Collected Letters of James A. H. Murray, Editor and The Collected Works of Frank Chance, Man of Letters, but, since I am neither a publisher nor a rich man, the books will never appear. To make amends, I have reproduced the letter about the curse of Scotland. As could be expected, Murray received many answers. As late as 1893, his team was obviously unaware of the publications in the Notes and Queries that appeared more than forty years earlier.

“James A. H. Murray, the first and greatest editor of The Oxford English Dictionary.” Image credit: James Murray, editor and philologist via The Oxford English Dictionary. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“James A. H. Murray, the first and greatest editor of The Oxford English Dictionary.” Image credit: James Murray, editor and philologist via The Oxford English Dictionary. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.I have borrowed the next communication from W. A. Chatto’s entertaining book Facts and Speculations on the Origin and History of Playing Cards, 1846 (as quoted by F. C. Birkbeck Terry, an erudite and one of the most active contributors to the Notes and Queries): “This card… appears to have been known in the North as the ‘Curse of Scotland’ many years before the battle of Culloden; for Dr. Houstoun, speaking of the state of parties in Scotland shortly after the rebellion of 1715, says that the Lord Justice-Clerk Ormiston [the note has Ormistone, which, as I understand, is wrong], who had been very zealous in suppressing the rebels, ‘became universally hated in Scotland, where they called him the Curse of Scotland; and when the ladies were at cards playing the Nine of Diamonds (commonly called the Curse of Scotland), they called it the Justice Clerk’.” This is useful information, but it sheds no light on why one particular card got such an ominous name.

Several main participants in the battle of Culloden denied any knowledge of the rumors. The noblemen of the Jacobite party Lord Balmerino and the Lord Kilmanrock, both attainted (as the action was called at that time) and beheaded after the battle (on 18 August 1746), asked another leading supporter of Bonnie Prince Charles, whether he had heard of any such order being made before the battle for giving no quarter to the Duke’s army. This exchange occurred on the day of their execution for high treason, and the doomed men would have gained nothing by lying. They affirmed that they had never heard of such orders. Lord Balmerino said “that he would not knowingly have acted under such order, because he looked upon it as unmilitary, and beneath the character of a soldier.”

No such statement from the duke is extant. The defeated Jacobites were treated with great severity, but no atrocities comparable to those only too well known to our contemporaries were reported. References to the behavior beneath the character of a soldier should seldom be taken at face value, for war is war and has always been attended by unspeakable cruelty. However, neither Prince William (despite the nickname butcher duke) nor the Pretender seems to have given such an order, let alone written it on the back of a playing card, and such a card hardly ever existed.

Today we know for sure that the phrase indeed predates the battle of Culloden, for as early as 1708, a book of questions and answers, titled The British Apollo (about which see my post for June 7, 2017), printed the following reply to the query about this phrase: “Diamonds as the Ornamental jewels of a Royal Crown, imply no more in the above-nam’ed Proverb than a mark of Royalty, for SCOTLAND’S Kings for many Ages, were observ’d, each Ninth to be a Tyrant, who by Civil Wars, and all the fatal consequences of intestal [sic: that is, internecine, internal] discord, plunging the Divided Kingdom into strong Discord, gave occasion, in the course of time, to form the Proverb.” This answer is reproduced with a photo of the page in Wikipedia at Curse of Scotland. Last week, I began my discussion with the hypothesis about every ninth king and need say no more about it.

At this stage of our disquisition, only one conclusion is clear. By 1708, the phrase had become so familiar that no one knew how it came about. The style of The British Apollo is always the same, and there is only one name for it: apodictic (no reasoning, no proof). The editors shed words of wisdom, and we are supposed to admire rather than question their omniscience. I noted this feature of their replies in my post, referred to a few lines above.

Next week will be devoted to the November gleanings, and in early December I’ll finish Act 2. We have one more important battle to discuss and draw some conclusions from our material.

Featured image credit: The Battle of Culloden, oil on canvas by David Morier. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Nine of diamonds, or the curse of Scotland: an etymological drama in two acts: Act 2, Scene 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

Key UK legislation 1987-2017 [timeline]

Where were you in 1987? Platoon wins the best picture Oscar, the Channel Tunnel gets the go ahead, and The Great Storm batters South East England. Meanwhile in a Greek restaurant in Shepherd’s Bush, Francis Rose and publisher Alistair MacQueen come up with the idea of the Blackstone’s Statutes series.

Thirty years later the series is still going strong thanks to careful editorship and a conscientious selection of legislation. The familiar purple books have been at the sides of millions of law students through their exams.

To mark the 30th anniversary of the series, we’ve created a timeline to highlight key pieces of UK legislation passed since 1987.

Featured image credit: Case-Law, Lady Justice, Justice by AJEL. CCO Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Key UK legislation 1987-2017 [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers