Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 266

July 18, 2013

Aidan Nichols on the Anglican Ordinariate

Yesterday, I came home from work to find this book in my mail! I had requested a review copy from Gracewing and it has arrived--a lovely combination of subject, author, and even the cover photo. Father Aidan Nichols, OP is one of my favorite authors (I've read several of his books, including Catholic Thought since the Enlightenment. A Survey; G.K. Chesterton, Theologian; Rome and the Eastern Churches: A Study in Schism; The Panther and the Hind. A Theological History of Anglicanism; The Realm: An Unfashionable Essay on the Conversion of England; and Christendom Awake: On Re-energizing the Church in Culture.

And of course, you know of my abiding interest in the Anglican Ordinariate; so please watch this space for a review. According to the publisher:

When in 1993 Aidan Nichols revived the long-dormant idea of an Anglican Uniate Church, united with the See of Peter but not absorbed, the reaction of many was incredulity. The ideal of modern Ecumenism was, surely, the corporate reunification of entire Communions. This he roundly declared to be unrealistic, for the Protestant and Liberal elements in Anglican history (and Anglicanism's present reality) could never be digested by Roman stomachs. What was feasible was, rather, the reconciliation of a select body Catholic enough to be united, and Anglican enough not to be absorbed. Just over a dozen years later Pope Benedict XVI, responding to the petitions of various Anglican bishops, promulgated the Apostolic Constitution Apostolorum coetibus and the deed was done. The three 'Ordinariates' now established for 'Catholics of the Anglican Patrimony' in Britain, Australia and North America have been described as the first tangible fruit of Catholic Ecumenism. In this short book Nichols reflects on the historical, theological, and liturgical issues involved. He also shows the congruence of the new development with Benedict's wider thinking, and outlines a specific missionary vocation for reconciled Anglicans in England.

You might remember that early in Pope Francis' reign there was concern that he was not that supportive of the Anglican Ordinariate. A recent announcement alleviates that concern completely, as Damian Thompson reported in his blog:

Opponents of the Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham, set up by Benedict XVI to allow ex-Anglicans to worship together with their own liturgy, were so excited when it was reported that Pope Francis, when Archbishop of Buenos Aires, wasn't keen on the initiative. But if that were ever the case, then he has changed his mind.

This week it emerged that Francis has widened the remit of the Ordinariates in Britain, America and Australia. Until now, only ex-Anglicans and their family members could join the new body. But, thanks to a new paragraph inserted into the Ordinariate's constitution by Francis, nominal Catholics who were baptised but not confirmed can join the structure. Indeed, the Holy Father wants the Ordinariates to go out and evangelise such people. Put bluntly, this suggests that English bishops who wanted to squash the body – and whose allies were rushing to get to the new Pope in order to brief against it – have been thwarted.

Here's the fine print, from the Ordinariate's website :

Pope Francis has approved a significant amendment to the Complementary Norms which govern the life of the Personal Ordinariates established under the auspices of Anglicanorum Coetibus.

On 31 May 2013, the Holy Father made a modification to Article 5 of the Norms, in order to make clear the contribution of the Personal Ordinariates in the work of the New Evangelisation.

This paragraph has been inserted into the Complementary Norms as Article 5 §2:

A person who has been baptised in the Catholic Church but who has not completed the Sacraments of Initiation, and subsequently returns to the faith and practice of the Church as a result of the evangelising mission of the Ordinariate, may be admitted to membership in the Ordinariate and receive the Sacrament of Confirmation or the Sacrament of the Eucharist or both.

This confirms the place of the Personal Ordinariates within the mission of the wider Catholic Church, not simply as a jurisdiction for those from the Anglican tradition, but as a contributor to the urgent work of the New Evangelisation.

As noted by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, enrolment into a Personal Ordinariate remains linked to an objective criterion of incomplete initiation (i.e. baptism, eucharist, or confirmation are lacking), meaning that Catholics may not become members of a Personal Ordinariate ‘for purely subjective motives or personal preference’.

So there you have it: a ringing affirmation of the Ordinariate's mission from a supposedly sceptical pontiff. Now what the new body needs is money and perhaps a little more courage to stick its head above the parapet. The Catholic Bishops of England and Wales have so far declined to organise a nationwide second collection at Mass to help their new brethren. They should do so without delay.

It just makes sense that Pope Francis would "embrace" the Anglican Ordinariate, since it is a great means of evangelization, and that's the great theme of his pontificate, putting the "New Evangelization" promoted by Blessed John Paul II and Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI into action!

Published on July 18, 2013 23:00

St. John Plessington, a Popish Plot Martyr

The Diocese of Shrewsbury provides a biography of one of its two martyrs canonized by Pope Paul VI in 1970, St. John Plessington:

St John Plessington is one of two Shrewsbury saints to be canonised among the 40 martyrs of England and Wales in 1970, the other being St Margaret Ward . He is also one of six of the 40 martyred after they were accused of treason in the “Popish Plot”, which had been fabricated by Titus Oates, and which led to the deaths of more than 25 innocent Catholics in the late part of the 17th century.

Although he was born in Dimples, near Garstang, Lancashire, St John exercised his ministry in Cheshire and North Wales, and he was hanged, drawn and quartered on 19th July 1679 at Boughton Cross, overlooking the River Dee at West Chester. What is remarkable about his execution is that St John wrote his speech for the scaffold ahead of his death. It was later printed and copies still exist. According to Butler’s Lives of the Saints the speech represents “a particularly clear statement of denial in the face of death of the charges upon which he was condemned”, charges which, had they been true, would have made him a dangerous criminal rather than a martyr.

And this site provides the text of his speech:

Dear Countrymen,

I am here to be executed, neither for Theft, Murder, nor anything against the Law of God, nor any fact or Doctrine inconsistent with Monarchy or Civil Government. I suppose several now present heard my trial the last Assizes, and can testify that nothing was laid to my charge but Priesthood, and I am sure that you will find that Priesthood is neither against the Law of God nor Monarchy, or Civil Government. If you will consider either the Old or New Testament (for it is the Basis of Religion […], St Paul tells us in Hebrews 7:12 that the Priesthood being changed, there is made of necessity a change of the Law, and consequently the Priesthood being abolished, the Law and Religion is quite gone.

But I know it will be said that a Priest ordained by authority derived from the See of Rome is by the Law of Nation to die as a Traitor, but if that be so what must become of all the Clergymen or England, for the first Protestant Bishops had their Ordination from those of the Church of Rome, or none at all, as appears by their own writers, so that Ordination comes derivatively to those now living.

As in the Primitive times, Christians were esteemed Traitors, and suffered as such by National Law, so are the Priests of the Roman Church here esteemed, and suffer such. But as Christianity then was not against the law of God, Monarchy or Civil Policy, so now there is not any one Point of the Roman Catholic Faith (of which Faith I am) that is inconsistent therewith, as is evident by induction in each several point. . . .

Both of the websites I've linked include a picture of "a stained glass window in St Winefride’s Church, Holywell, depicts St John ministering to a kneeling woman then giving his speech on the day of his execution." It's interesting that he was allowed to give his speech in full before his execution, but like other Popish Plot martyrs, he had been serving a Catholic family in the area for several years---in his case a decade--without any trouble. It was the Popish Plot and the resulting anti-Catholic hysteria, and the added inducements to turn in any priest for reward and recognition that led to his arrest, charge, and execution.

St John Plessington is one of two Shrewsbury saints to be canonised among the 40 martyrs of England and Wales in 1970, the other being St Margaret Ward . He is also one of six of the 40 martyred after they were accused of treason in the “Popish Plot”, which had been fabricated by Titus Oates, and which led to the deaths of more than 25 innocent Catholics in the late part of the 17th century.

Although he was born in Dimples, near Garstang, Lancashire, St John exercised his ministry in Cheshire and North Wales, and he was hanged, drawn and quartered on 19th July 1679 at Boughton Cross, overlooking the River Dee at West Chester. What is remarkable about his execution is that St John wrote his speech for the scaffold ahead of his death. It was later printed and copies still exist. According to Butler’s Lives of the Saints the speech represents “a particularly clear statement of denial in the face of death of the charges upon which he was condemned”, charges which, had they been true, would have made him a dangerous criminal rather than a martyr.

And this site provides the text of his speech:

Dear Countrymen,

I am here to be executed, neither for Theft, Murder, nor anything against the Law of God, nor any fact or Doctrine inconsistent with Monarchy or Civil Government. I suppose several now present heard my trial the last Assizes, and can testify that nothing was laid to my charge but Priesthood, and I am sure that you will find that Priesthood is neither against the Law of God nor Monarchy, or Civil Government. If you will consider either the Old or New Testament (for it is the Basis of Religion […], St Paul tells us in Hebrews 7:12 that the Priesthood being changed, there is made of necessity a change of the Law, and consequently the Priesthood being abolished, the Law and Religion is quite gone.

But I know it will be said that a Priest ordained by authority derived from the See of Rome is by the Law of Nation to die as a Traitor, but if that be so what must become of all the Clergymen or England, for the first Protestant Bishops had their Ordination from those of the Church of Rome, or none at all, as appears by their own writers, so that Ordination comes derivatively to those now living.

As in the Primitive times, Christians were esteemed Traitors, and suffered as such by National Law, so are the Priests of the Roman Church here esteemed, and suffer such. But as Christianity then was not against the law of God, Monarchy or Civil Policy, so now there is not any one Point of the Roman Catholic Faith (of which Faith I am) that is inconsistent therewith, as is evident by induction in each several point. . . .

Both of the websites I've linked include a picture of "a stained glass window in St Winefride’s Church, Holywell, depicts St John ministering to a kneeling woman then giving his speech on the day of his execution." It's interesting that he was allowed to give his speech in full before his execution, but like other Popish Plot martyrs, he had been serving a Catholic family in the area for several years---in his case a decade--without any trouble. It was the Popish Plot and the resulting anti-Catholic hysteria, and the added inducements to turn in any priest for reward and recognition that led to his arrest, charge, and execution.

Published on July 18, 2013 22:30

July 17, 2013

How to Measure the Success of an Interview

In my full time job I work at a corporation and of course corporations measure everything (especially P&L!). As I work in my free time to promote my book and my ideas, using this blog, facebook, twitters, articles, and radio interviews, I do try to measure my success. I can't really measure my success in dollars, because the return on a book through royalties is rather low. So I have used other measures--contact; connections; comments; compliments; even complaints. These measures tell me that I have had some impact. Last Saturday, I spoke to Barbara McGuigan on EWTN Radio for two hours on her "The Good Fight" radio show, and I invited listeners to search for my blog by "googling" supremacy and survival blog--and I know that 10 people found my blog by using that search. Five more found it by googling stephanie mann supremacy survival, and two or three by combinations like Stephanie Mann blog or stephanie mann barbara mcguigan. Overall page views on my blog increased. Therefore, the interview did produce measurable results. Two listeners left comments on my English History: from Henry VIII to John Henry Newman (1500-1900) facebook page (see badge in the right hand column on this blog) and I received one direct email comment.

In my full time job I work at a corporation and of course corporations measure everything (especially P&L!). As I work in my free time to promote my book and my ideas, using this blog, facebook, twitters, articles, and radio interviews, I do try to measure my success. I can't really measure my success in dollars, because the return on a book through royalties is rather low. So I have used other measures--contact; connections; comments; compliments; even complaints. These measures tell me that I have had some impact. Last Saturday, I spoke to Barbara McGuigan on EWTN Radio for two hours on her "The Good Fight" radio show, and I invited listeners to search for my blog by "googling" supremacy and survival blog--and I know that 10 people found my blog by using that search. Five more found it by googling stephanie mann supremacy survival, and two or three by combinations like Stephanie Mann blog or stephanie mann barbara mcguigan. Overall page views on my blog increased. Therefore, the interview did produce measurable results. Two listeners left comments on my English History: from Henry VIII to John Henry Newman (1500-1900) facebook page (see badge in the right hand column on this blog) and I received one direct email comment.Even though Barbara and I were discussing the Blessed Carmelite Martyrs of Compiegne and the history of de-Christianization of France during the French Revolution, we did bring up the English Reformation and Barbara kindly plugged my book several times. I did see some movement in the ranking on Amazon.com for my book, but I have no way of knowing of any other book sales (at EWTN or other sites or even bookstores) that might have occurred because of her comments.

Of course what's impossible to measure was the satisfaction and fun of speaking with Barbara and with the listeners who called in with questions or comments--two callers even mentioned the operatic connections of Picpus Cemetery: Andrea Chenier and the Carmelites, which I knew about--and, indirectly, Beethoven's Fidelio (not to mention Fernando Paer's version of the same story, and two other operas), which I did not know about--inspired by Adrienne de Noailles Lafayette's efforts to help her husband, the Marquis de Lafayette, escape from prison in Olmütz. You can read more about the Marquise here and more about the operas inspired by their imprisonment here. When the family was finally released from that prison, they probably felt like the prisoners in the great chorus of Fidelio:

So now whenever I hear one of Beethoven's Leonore overtures or listen to my recording of Fidelio (the Klemperer, Ludwig, Vickers classic), I'll think of the Marquise Adrienne de Noailles Lafayette! That kind of enrichment is really immeasurable.

Published on July 17, 2013 22:30

July 16, 2013

The Carmelite Martyrs of Compiegne on the Son Rise Morning Show

Today I'll be on the Son Rise Morning Show at 6:45 a.m. Central/7:45 a.m. Eastern because this is the memorial (in France) of the Carmelite martyrs of Compiegne, victims of the Committee for Public Safety and French Revolution, executed in Paris in 1794. Brian Patrick and I will discuss the sacrificial martyrdom of these Carmelites, who swore to offer their deaths for the peace of France. The Catholic martyrs of the French Revolution are probably as little known as the martyrs of the English Reformation have been, although I hope I've made a dent in that ignorance. Many priests and nuns suffered torture, execution--and exile during the Reign of Terror.

The Carmelites' story also has a great connection to the English Reformation and the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The exiled French priests and nuns who fled the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the dangers of the Terror provoked feelings of sympathy in England. The fact that they were allowed to practice their faith while English Catholics were not contributed to the Catholic Relief movement in Parliament. Among those exiles were actually English Benedictine nuns from Cambrai--they were English nuns in exile on the Continent who then founded a new monastery at Stanbrook Abbey. The foundress of the Cambrai house was none other than Helen More, the great-great-granddaughter of St. Thomas More. Her name in religion became Dame Gertrude More. The Benedictines of Our Lady of Comfort in Cambrai wore the secular clothing of the Carmelites on their journey "home". Stanbrook Abbey was the inspiration for Rumer Godden's novel, In This House of Brede, one of my favorite books. According to her New York Time's obituary:

To do research on ''In This House of Brede,'' Ms. Godden lived for three years near Stanbrook Abbey. Her experience with the nuns there contributed to her decision to convert to Roman Catholicism in 1968. In many of her stories and novels, Ms. Godden would write about the rewards and perils of the contemplative life.

A couple of years ago, I went on a mini-pilgrimage in Paris to the site of the Blessed Carmelites' execution and then to the cemetery behind which their remains were dumped into mass graves: here are links to those posts: the site of execution and the chapel at Picpus, the cemetery grounds at Picpus, and the mass graves.

There were sixteen martyrs in all on July 17, 1794:

Choir Nuns

Mother Teresa of St. Augustine, prioress (Madeleine-Claudine Ledoine) b. 1752

Mother St. Louis, sub-prioress (Marie-Anne [or Antoinett] Brideau) b. 1752

Mother Henriette of Jesus, ex-prioress (Marie-Françoise Gabrielle de Croissy) b. 1745

Sister Mary of Jesus Crucified (Marie-Anne Piedcourt) b. 1715

Sister Charlotte of the Resurrection, ex-sub-prioress and sacristan (Anne-Marie-Madeleine Thouret) b. 1715

Sister Euphrasia of the Immaculate Conception (Marie-Claude Cyprienne) b. 1736

Sister Teresa of the Sacred Heart of Mary (Marie-Antoniette Hanisset) b. 1740

Sister Julie Louise of Jesus, widow (Rose-Chrétien de la Neuville) b. 1741

Sister Teresa of St. Ignatius (Marie-Gabrielle Trézel) b. 1743

Sister Mary-Henrietta of Providence (Anne Petras) b. 1760

Sister Constance, novice (Marie-Geneviève Meunier) b. 1765

Lay Sisters

Sister St. Martha (Marie Dufour) b. 1742

Sister Mary of the Holy Spirit (Angélique Roussel) b. 1742

Sister St. Francis Xavier (Julie Vérolot) b. 1764

Externs:

Catherine Soiron b. 1742

Thérèse Soiron b. 1748

[Image Source: wikipedia commons--from the Carmel in Quidenham, Norfolk!]

Published on July 16, 2013 22:30

July 15, 2013

The Carmelites in Britain Before and After the English Reformation

On this feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, it's only appropriate for me to highlight the presence and absence and restoration of the Carmelite order in England. According to the website of the British Province of Carmelite Friars:

The hermit brothers from Mount Carmel were first brought to Britain in 1242 by returning crusaders; arriving first at Hulne near Alnwick in the north east of England, and then later in the same year at Aylesford in the southern county of Kent.

At that time we were still a group of hermits but, following a historic General Chapter (meeting of the Order) held at Aylesford in 1247, we became part of the newly formed movement of mendicant friars (begging brothers). Because of our white cloaks, we became known as the Whitefriars. . . .

At its height there were more than 1,000 friars in the English Province in some 40 communities (known as priories, friaries or convents), divided into four 'distinctions' with regional headquarters at London, Oxford, Norwich and York. . . .

Carmelite friars were pastors and theologians, confessors to kings and servants of the poor. To read an article about Carmelite spirituality in the fourteenth century, please click here.

Although there was no 'Third Order' of Lay Carmelites and no Carmelite nuns in Britain before the Reformation, we do know of many lay people - including women - who had varying degrees of affiliation to the Order.

The Carmelite presence disappeared from Britain in 1538 with the Dissolution of the Monasteries under King Henry VIII. At the Reformation the friars were dispersed and the houses were either desecrated and destroyed or handed out to private individuals as rewards by the Crown.

The last active friar we know of, George Rayner, died for the Faith in chains (in odium fidei) in York prison during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I.

The site also has information about the restoration of the Carmelite order and the interim when English Carmelites lived in exile on the Continent here. There are even more great resources on the order between the dissolution and the restoration linked here.

St. Simon Stock of England is one of the better known of the Carmelite saints, who received the Brown Scapular in a vision of Our Lady and wrote this prayer:

Flower of Carmel, tall vine, blossom-laden;

splendour of heaven, child-bearing, yet maiden;

none equals thee.

Mother so tender, whom no man didst know,

on Carmel's children thy favours bestow;

Star of the Sea!

Strong stem of Jesse, who bore one bright flower,

be ever near us, and guard us each hour,

who serve thee here.

Purest of lilies, that flowers among thorns,

bring help to true hearts that in weakness turn

and trust in thee.

Strongest of armour, we trust in thy might,

under thy mantle, hard pressed in the fight,

we call to thee.

Our way, uncertain, surrounded by foes,

unfailing counsel you offer to those

who turn to thee.

O gentle Mother, who in Carmel reigns,

share with your servants that gladness you gained,

and now enjoy.

Hail, gate of heaven, with glory now crowned,

bring us to safety, where thy Son is found,

true joy to see. Amen.

Published on July 15, 2013 22:30

July 13, 2013

Bastille Day and Religious Freedom

Today is Bastille Day, when France celebrates the Revolution of 1789. As I view the day, I note that the celebration occurs in the midst of the Novena to Our Lady of Mount Carmel, just two days before that Feast and just three days before the memorial of the Blessed Carmelite Martyrs of Compiegne, whom I discussed with Barbara McGuigan yesterday on The Good Fight and will this Wednesday discuss with Brian Patrick on the Son Rise Morning Show. I sent a version of this post to Barbara as background for our conversation.

Since January 2012, when the Obama administration issued the final version of the Health and Human Services (HHS) Mandate of insurance coverage for “free” contraceptive, abortafacient, and sterilization services, many pundits have cited the historical example of Henry VIII and the English Reformation. See for example, Chris Matthews’ comments on MSNBC: “I guess I grew up watching movies like Becket and A Man for All Seasons and seeing the church and state go to war with each other and being told stories from the Old Testament about the Maccabees, about people, families being told you got to eat pork,” he said. Matthews added that it is “frightening” to him “when the state tells the church what to do.” On The Catholic World Report website, Matthew Cullinan Hoffman saw some parallels between Elizabethan era recusancy laws and the Obama administration’s HHS Mandate against Catholic consciences:

“Intentionally or not, the administration’s policy smacks of the methods established by England’s Queen Elizabeth against Catholic “recusants,” who refused to participate in the worship services of the Anglican Church during the late 16th century. Although Elizabeth’s regime, and those that followed for the next two hundred years, did not provide a penalty for Catholic belief as such, they found a simple and devastating way to coerce Catholics to violate their consciences: the recusancy fine, which was levied against those who absented themselves from Sunday Anglican worship or failed to receive communion once a year.”

In the summer of 2012 and again this summer, the United States Council of Catholic Bishops have sponsored the Fortnight for (Religious) Freedom from June 21 to July 4, beginning the fourteen day period of prayer, fasting, and protest the day before the memorial of Sts. John Fisher and Thomas More. St. Thomas More has particularly been the focus, since he was a layman (and the bishops are calling on the laity for leadership in this effort), and he has even been featured on a prayer card.

While I have been supportive of this interpretation, I think that the French Revolution’s attack on the Catholic Church might be an even better historical parallel for us to consider.

While the English Reformation did introduce a great conflict between Catholics and the state, it did so by creating an Erastian (state controlled) Christian church. There is definitely a confessional element here of the officially Protestant state, with its head being the Supreme Head and Governor of the Church, persecuting Catholics for their faith, especially for their attendance at Holy Mass and their spiritual and ecclesial loyalty to the Pope as the Vicar of Christ. But I suggest the attempted secularization of French culture and the animosity of the revolutionary governments against the Catholic Church as being counter-revolutionary is the more apt comparison.

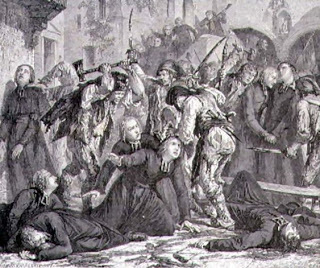

The Incorruptible Maximilien Robespierre and the Reign of Terror led a campaign to excise Christianity from French culture. The revolutionaries were acting on the Enlightenment philosophes’ verbal attacks on the Catholic Church, regarding it as an ally of the old regime. The National Constituent Assembly of France seized all Church property, suppressed convents and monasteries, and forced priests to serve as employees of the State, swearing an oath to the Revolution while denying loyalty to the Pope. The Blessed Sacrament was desecrated, church furnishings and artwork wrecked, and churches destroyed in a massive campaign of iconoclasm. More than 200 non-juring priests and three bishops—those who would not take the required oath—were brutally massacred in Paris on September 2 and 3, 1793 (pictured above). The Carmelites of Compiegne, the Ursulines of Valencienne, and nuns from other religious orders were guillotined as enemies of the Revolution.

The Incorruptible Maximilien Robespierre and the Reign of Terror led a campaign to excise Christianity from French culture. The revolutionaries were acting on the Enlightenment philosophes’ verbal attacks on the Catholic Church, regarding it as an ally of the old regime. The National Constituent Assembly of France seized all Church property, suppressed convents and monasteries, and forced priests to serve as employees of the State, swearing an oath to the Revolution while denying loyalty to the Pope. The Blessed Sacrament was desecrated, church furnishings and artwork wrecked, and churches destroyed in a massive campaign of iconoclasm. More than 200 non-juring priests and three bishops—those who would not take the required oath—were brutally massacred in Paris on September 2 and 3, 1793 (pictured above). The Carmelites of Compiegne, the Ursulines of Valencienne, and nuns from other religious orders were guillotined as enemies of the Revolution.Other steps in the dechristianization of France were to eliminate the Gregorian calendar, the seven day week, the Sunday day of rest and worship; change any street or city name with a religious reference; and ban holy days and saints’ feasts. A new calendar began with Year I of the new Republic. In all these efforts, the French revolutionary governments—from the fall of the monarchy to the restoration of some rights with Napoleon Bonaparte’s Concordat with the Vatican—wanted to demonstrate that the Catholic Church was an enemy of the revolution.

In the revolution’s terms, the Catholic Church was an enemy first because the Church had great wealth and had supported the old structures. But the deeper reason was that the Catholic Church could distract her members from loyalty to the revolution and new state that emphasized absolute unity around the ideals of Liberté, égalité, and fraternité. Note that priests and religious were particularly targeted, as the hierarchy of the Church was forced to choose between loyalty to the State and loyalty to the Church, and contemplative religious orders were suppressed because their lives of prayer and sacrifice were considered useless to the common good. Christianity was fundamentally in conflict with the goals of the revolution, and had to be eradicated from French culture. Of course, this attempt failed—even trying to replace Catholic worship of Almighty God and devotion to His saints with the Cult of the Supreme Being and other deist rituals and festivals—because many of the people, especially in the rural areas, remained true to the Catholic Faith. In the Vendee region of France they fought for their faith (and the monarchy) and the people suffered greatly when Robespierre and his Committee ordered their massacre and devastation of their crops and property.

In the revolution’s terms, the Catholic Church was an enemy first because the Church had great wealth and had supported the old structures. But the deeper reason was that the Catholic Church could distract her members from loyalty to the revolution and new state that emphasized absolute unity around the ideals of Liberté, égalité, and fraternité. Note that priests and religious were particularly targeted, as the hierarchy of the Church was forced to choose between loyalty to the State and loyalty to the Church, and contemplative religious orders were suppressed because their lives of prayer and sacrifice were considered useless to the common good. Christianity was fundamentally in conflict with the goals of the revolution, and had to be eradicated from French culture. Of course, this attempt failed—even trying to replace Catholic worship of Almighty God and devotion to His saints with the Cult of the Supreme Being and other deist rituals and festivals—because many of the people, especially in the rural areas, remained true to the Catholic Faith. In the Vendee region of France they fought for their faith (and the monarchy) and the people suffered greatly when Robespierre and his Committee ordered their massacre and devastation of their crops and property.The parallel I see to our situation today in the United States—and there is another very obvious parallel in France today with the Socialist Hollande government forcing so called “gay marriage” on the people in spite of their overwhelming protests against that legislative action —is the State proclaiming its absolute authority to force the Church and its members to accept the State’s version of the common good. (The same could be said of Enda Kenny of Irish Fine Gael imposing abortion on Ireland in spite of protests and opposition in his own party.) The Obama administration has obviously determined that these contraceptive and “reproductive health services” are required by its standards of the common good. The Church’s argument against that position has been rejected, even when we attempt to use natural law and the dignity of the human person, including the right to life of the unborn, and the fact that fertility is a normal, healthy condition. Our argument from the right of conscientious objection has also been ignored and rejected, because the State has determined that providing these reproductive services is a good that trumps conscience rights and the free exercise of religion, even though the latter is protected by the U.S. Constitution.

The French Revolution established a pattern of State control over and interference with Church and religion, combining those efforts with violence and destruction in the name of secular unity on earthly ideals. In 2012, the film For Greater Glory dramatized the Cristeros War in twentieth-century Mexico, during which the revolutionary government followed the French Revolution’s example to attempt again to destroy Catholicism. As often noted, of course, we are not facing life and death decisions like the recusant Catholics of England, the non-juring priests of France, or the Cristeros in Mexico. Catholic individuals, organizations, universities, and dioceses have access to legislative and judicial means to avoid either compromising our beliefs or paying fines. Nevertheless the French Revolution’s attack on the Catholic Church provides us with a fascinating historical parallel to the modern secular state attempts to impose its will on Catholics and other Christians in the name of the common good.

But the story would be incomplete without remembering the failure of this effort and the recovery of the Church after the French Revolution. The martyrdoms of the priests and seminarians in the September massacres, the execution of the Carmelites, Ursulines, and other religious, inspired Catholics to remain true to their Faith. The government’s very attempt to replace the Catholic Mass with deistic festivals showed that society abhorred the religious vacuum. The laity remained true to their devotions and prayers, even if they could not attend Mass.

And after the rise of Napoleon and the Concordat with the Vatican, the Church in France recovered and grew: new religious orders serving the poor flourished; the monastic orders revived; new educational and social efforts, like the Society of St. Vincent de Paul, involved the laity in charitable works. Great cathedrals and churches were reconsecrated for sacred worship and restored--church bells tolled again to call the people to prayer. although the bells in the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris, having been melted down for coinage and cannon shot, were replaced with out-of-tune bells. This situation was not remedied until 2013, when a new set of bells were consecrated and installed in time for Holy Week.

Pilgrimages to the sites of Marian apparitions—Lourdes, the Rue de Bac (Miraculous Medal), Laus, and La Sallette—recalled medieval piety and devotion. Great saints inspire the Church to this day: St. Therese of Lisieux, St. Bernadette Soubirous, St. Catherine Laboure, Blessed Frederic Ozanam, St. Peter Julian Eymard, St. John Vianney, and many foundresses of the religious orders like St. Mary Magdalen Postel (The Sisters of the Christian Schools of Mercy), St. Mary Euphrasia (The Good Shepherd Sisters), and St. Julie Billiart (The Institute of Notre Dame)—their lives of holiness and service demonstrate the chronic vigor of the Church.

Pilgrimages to the sites of Marian apparitions—Lourdes, the Rue de Bac (Miraculous Medal), Laus, and La Sallette—recalled medieval piety and devotion. Great saints inspire the Church to this day: St. Therese of Lisieux, St. Bernadette Soubirous, St. Catherine Laboure, Blessed Frederic Ozanam, St. Peter Julian Eymard, St. John Vianney, and many foundresses of the religious orders like St. Mary Magdalen Postel (The Sisters of the Christian Schools of Mercy), St. Mary Euphrasia (The Good Shepherd Sisters), and St. Julie Billiart (The Institute of Notre Dame)—their lives of holiness and service demonstrate the chronic vigor of the Church. These signs of revival and renewal clearly demonstrate the continuing guidance and inspiration of the Holy Spirit in the Church. Just as after the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century, God raised up many saints to lead and inspire the Church in the nineteenth century, the Age of Revolution in Europe. That’s why Catholic Church history is always so inspiring and even consoling: it proves that as He promised, Jesus is always with His Church. Whatever dangers or persecutions we encounter—from within and without—He protects and guides us to struggle on in this life to do His will.

Published on July 13, 2013 22:30

July 12, 2013

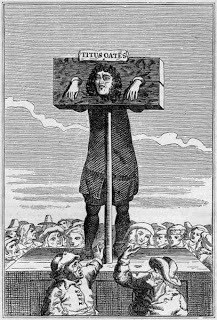

Titus Oates, RIP, July 13, 1705

Titus Oates died in 1705 on July 13, after marrying and becoming a Baptist minister (and then being defrocked); relatively obscure and with his fame forgotten--but still receiving a pension from the British government. BBC History Magazine selected Titus Oates as the Worst Briton of the 17th century and the third worst Briton in last one thousand years in 2006.

With the so-called Popish Plot, Oates implicated and caused the deaths of 15 Catholic priests and laity who were certainly not guilty of any plot to kill King Charles II--since there was no plot. Before the horror of those three years, however, Titus Oates also indicated an inability to decide which Church he belonged to, a propensity to immorality, and a previous charge of perjury. Although he failed at two colleges at the University of Cambridge, he was ordained in the Church of England and served in a parish and as chaplain on a ship, during which service he was accused of sodomy.

After joining the household of the Catholic Duke of Norfolk as a chaplain to the Anglicans in that household, he became a Catholic in 1677. At the same time, however, he was writing anti-Catholic pamphlets.

He studied for a time with the Jesuits in the seminary at Valladolid in Spain, later claiming just to have been there as a spy--he was indeed kicked out in 1678. By September of that same year, Oates was testifying to the King's Council about the Jesuit's plot to murder the Anglican Charles so that Charles' brother James, the Catholic Duke of York could succeed him.

Charles soon figured out that Oates was making some things up, at least, when he caught him in several lies and inaccuracies. He had Oates arrested, but Parliament forced his release. Oates was soon in posh apartments with a nice annual stipend. After a time, however, Judge William Scroggs, who had been subjecting the Catholic defendants to horrible verbal abuse in addition to sentencing them to death, began to turn his scorn upon those testifying against them, and declared the midwife Elizabeth Cellier and Lord Castlemaine, the husband of one of Charles II's mistresses, Barbara, innocent in their trials. In Cellier's trial, he sentenced her accuser to prison for perjury.

Finally, in 1681, Oates was disgraced--kicked out of his nice pad, charged and convicted of sedition, and put in prison. When the Duke of York did succeed his brother, James II had Oates retried, convicted of perjury and sentenced to annual pillory, as pictured above.

During the reign of William and Mary Oates was pardoned and granted another pension.

Published on July 12, 2013 23:00

Two Conferences in One: the Catholic Writer's Guild Conference

From the CWG Blog:

From the CWG Blog:Two conferences of awesomeness, one convenient location. You only need to register for one conference, and you get into the other on that same ticket. Your registration fee covers the cost of renting the venue and lining up the entertainment, supplies, etc., but if you would like to attend the banquets sponsored by the CMN, make sure you purchase tickets when you register.

Conference #1: The Catholic “Marketing Network” Conference.

The title is not quite what it sounds like. This is the trade organization for Catholic bookstores, and producers of Catholic books and goods.

What you’ll get:

1. A giant warehouse sale at what will be, for three days, the largest Catholic Bookstore in the World. Every major Catholic publisher, and a bunch you’ve never heard of. Inspirational gifts, jewelry, games, DVD’s, clothing, bumperstickers, glow-in-the-dark crucifixes — all that cool stuff and then some. Booths run by the friendliest people on the planet. And everything’s on sale, because this is where the independently-owned bookstores come to make their purchases, so the discounts are deep.

2. Daily Masses with some of your favorite priests, adoration chapel (run by the Franciscan Sisters of the Renewal, if they do like last year), confession times offered throughout the week, rosary and holy hours.

3. Evening entertainment (included with your regular admission, no extra charge): Film previews, live music, and inspirational speakers.

4. Book signings and giveaways hosted by all the major publishers.

Conference #2: The Catholic Writers Guild Live Conference. If you like to write, and want a small, encouraging conference where people will learn your name, take an interest in you, and not try to talk you into soft porn as an “art form”, this is the place.

What you get:

5. So many workshops you can’t actually attend them all. Fiction with Michelle Buckman, marketing with one of Amazon’s top e-book bestsellers, a blogging super-panel, legal topics, writers like Teresa Tomeo and Randy Hain and Pat Gohn, and everything you need to know about getting published, from first inspiration until your book is in the reader’s hand. 6. Critique sessions with Art Powers — bring your work and get ready to grow your skills. 7. Pitch sessions: Talk face-to-face with your would-be publisher, and find out if your book is the kind they’d like to add to their line-up. (Register with CWG if you’re

Although I cannot attend this year, I do recommend the conference highly and I do hope to attend in 2014!

Published on July 12, 2013 22:30

July 11, 2013

July 12: Martyrs, A Wedding, and Battles in Ireland

July 12 offers three themes for this blog:

Martyrs:

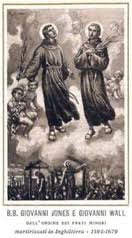

The Franciscans honor their martyrs during the English Reformation: St. John Jones and St. John Wall, and Blesseds Arthur Bell, John Woodcock, and Charles Meehan-Mahoney--their Franciscan memorial date determined by St. John Jones' date of execution in 1598. (And although his memorial is on May 22, I can't leave out Blessed John Forest from this honor roll). Just like the Benedictines yesterday, the Franciscans have martyrs from all three eras: Supremacy, Recusant, and Popish Plot.

A Wedding:

On July 12, 1543, Henry VIII married for the sixth and last time--and his bride was Catherine Parr. This was her third of four marriages, as she married Thomas Seymour after Henry's death in 1547. She had previously been married to Edward Borough and John Neville, Lord Latimer. While married to John Neville she was held hostage in Yorkshire during the Pilgrimage of Grace. His death left her a wealthy widow. Henry VIII noticed her in the household of his daughter Mary. Although she was interested in wedding Thomas Seymour, she thought it prudent to accept the king's proposal!

Battles in Ireland:

While the dates have been under contention, because of the rivalry between the Julian and the Gregorian calendars in the Protestant and Catholic countries of Europe, the Orange Army in on the march today with their annual parades, celebrating the Battle of the Boyne and the Battle at Aughrim and the defeat of James II by William (of William and Mary).

After these decisive victories in Ireland, and the Jacobite surrender of the seige of Limerick, more punitive Penal Laws were passed against Irish Catholics, including, but limited to:

~Exclusion of Catholics from most public offices (since 1607)

~Ban on intermarriage with Protestants; repealed 1778

~Catholics barred from holding firearms or serving in the armed forces (rescinded by Militia Act of 1793)

~Exclusion from the legal professions and the judiciary; repealed (respectively) 1793 and 1829.

~Education Act 1695 – ban on foreign education; repealed 1782.

~Bar to Catholics entering Trinity College Dublin; repealed 1793.

~On a death by a Catholic, his legatee could benefit by conversion to the Church of Ireland;

~Popery Act – Catholic inheritances of land were to be equally subdivided between all an owner's sons with the exception that if the eldest son and heir converted to Protestantism that he would become the one and only tenant of estate and portions for other children not to exceed one third of the estate. This "Gavelkind" system had previously been abolished by 1600.

~Ban on converting from Protestantism to Roman Catholicism on pain of Praemunire: forfeiting all property estates and legacy to the monarch of the time and remaining in prison at the monarch's pleasure. In addition, forfeiting the monarch's protection. No injury however atrocious could have any action brought against it or any reparation for such.

~Ban on Catholics buying land under a lease of more than 31 years; repealed 1778.

~Ban on custody of orphans being granted to Catholics on pain of 500 pounds that was to be donated to the Blue Coat hospital in Dublin.

~Ban on Catholics inheriting Protestant land

~Prohibition on Catholics owning a horse valued at over £5 (in order to keep horses suitable for military activity out of the majority's hands)

~Roman Catholic lay priests had to register to preach under the Registration Act 1704, but seminary priests and Bishops were not able to do so until 1778

~When allowed, new Catholic churches were to be built from wood, not stone, and away from main roads. [Easier to burn down?]

~'No person of the popish religion shall publicly or in private houses teach school, or instruct youth in learning within this realm' upon pain of twenty pounds fine and three months in prison for every such offence. Repealed in 1782.

~Any and all rewards not paid by the crown for alerting authorities of offences to be levied upon the Catholic populace within parish and county.

Published on July 11, 2013 22:30

July 10, 2013

Benedictine Martyrs of the English Reformation

Since July 11 is the feast of St. Benedict of Nursia, founder of Western style monasticism, it seems only right for me to post some background on the Benedictine martyrs of the English Reformation. According to my categorization of the different causes of martyrdom during and after the Long English Reformation, Benedictines suffered as Supremacy Martyrs during the reign of Henry VIII, as Recusant Martyrs during the reigns of Elizabeth I, James I and Charles I, and one as a Popish Plot martyr during the reign of Charles II.

Since July 11 is the feast of St. Benedict of Nursia, founder of Western style monasticism, it seems only right for me to post some background on the Benedictine martyrs of the English Reformation. According to my categorization of the different causes of martyrdom during and after the Long English Reformation, Benedictines suffered as Supremacy Martyrs during the reign of Henry VIII, as Recusant Martyrs during the reigns of Elizabeth I, James I and Charles I, and one as a Popish Plot martyr during the reign of Charles II.The Benedictine Supremacy martyrs are:

Blessed John Beche, Abbot of Colchester, 1 December 1539

Blessed Hugh Faringdon, Abbot of Reading, 14 November 1539

Blessed Richard Whiting, Abbot of Glastonbury, 15 November 1539

Blessed John Rugg, 15 November 1539

Blessed John Thorne, 15 November 1539

(All beatified on 13 May 1895 by Pope Leo XIII)

The Benedictine Recusant martyrs are:

St. John Roberts, 10 December 1610

St. Alban Bartholomew Roe, 21 January 1642

Blessed Mark Barkworth, 27 February 1601

Blessed George Gervase, 11 April 1608

Blessed Maurus Scott, 30 May 1612

Blessed Philip Powell (sometimes spelled Philip Powel), 30 June 1646

(The first two canonized in 1970 by Pope Paul VI, the others beatified either by Pope Pius XI on 15 December 1929 or Blessed John Paul II on 22 November 1987)

The Benedictine Popish Plot martyr is:

Blessed Thomas Pickering, 9 May 1679 (Benedictine lay brother) (Beatified by by Pope Pius XI on 15 December 1929)

Other Benedictines, like Elizabeth Barton and her confessors, suffered for their faith, but have not been beatified or canonized. The Supremacy martyrs were those abbots and monks who suffered during the Dissolution of Monasteries, and again, there were other Benedictines or Cistercians who suffered after the Pilgrimage of Grace who have not been designated as holy martyrs for some reason. Mary I restored the Benedictine order at Westminster Abbey, but with her death, Elizabeth I dissolved the order again. By 1607, there was only one Benedictine monk of the pre-Reformation era alive, Dom Sigebert Buckley, and he is the bridge for the order in the seventeenth century--down to one man!

Published on July 10, 2013 23:00