Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 268

July 1, 2013

Henry VIII: Psychopath?

From novelist Nancy Bilyeau, via the English Historical Fiction Authors blog:

This theory about Henry's mental wiring comes from Oxford researcher Kevin Dutton, who wrote The Wisdom of Psychopaths: Lessons in Life from Saints, Spies and Serial Killers, coming out in paperback later this year. That's correct--this is, among other things, a self-help book. "Psychopaths have a lot of good things going for them," declares the book's website. "They are fearless, confident, charismatic, ruthless and focused--qualities tailor-made for success in twenty-first century society." And for the mid-16th century too? Instead of feeling repulsed by Henry's psychopathic side, should I be proud of him? When he consigned devoted ministers Thomas More and Thomas Cromwell to the Tower, he wasn't cold, he was charismatic. Way to be the boss!

Still, I wanted to know how Professor Dutton diagnosed Henry Tudor. It seems that there is a list of criteria ranging from emotional detachment to feelings of alienation, and 10 people considered "Britain's greatest" were put to the test. Only Henry VIII scored high enough: 174 on a spectrum that required a minimum score of 168 to make it to the Big P. The nine who did not make it: Charles Darwin, Isaac Newton, Elizabeth I, Charles Dickens, Freddie Mercury, Lord Byron, William Shakespeare, Winston Churchill and Oscar Wilde. (I love Queen, but Freddie Mercury?)

If you'd like to know more about the job requirements for being a psychopath, Professor Dutton has a quiz--or rather a "Challenge." Typical of the questions: "Cheating on your partner is OK so long as you don't get caught." Hmmmm. When I think of Henry's marital history, it seems that cheating on his partners was OK even if he was caught. Didn't the Tudor king inform his outraged second wife, "Close your eyes, as your betters have done before you"?

Perhaps Professor Dutton is on to something. But before I agree to lump Henry VIII with Ted Bundy, I thought I'd refresh my memory on what other psychologists and historians have said about Henry's psychological state. His outrageous reign has led to all sorts of speculation.

Read the rest here. Among the theories that Bilyeau discusses is the view that in 1536, Henry VIII suffered terrible injuries in the joust. He was left with that horrible leg wound that would not heal.

I reviewed Suzannah Lipscomb's book, 1536: The Year That Changed Henry VIII a couple of years ago, and I doubted her thesis that he changed so greatly. As Bilyeau notes, he was cruel and capricious toward his courtiers before 1536, too! This was my conclusion:

It's tempting to look at 1536 and the events of those twelve months (the fall at the tournament; the written attack by Reginald Pole; Anne Boleyn's miscarriage, arrest, trial, and execution; the death of Henry Fitzroy, and the Pilgrimage of Grace) as a source for a radical change in behavior. I think rather that there was a development of Henry's characteristic behavior dating from 1534, the beginning of his "reign of terror" against anyone who opposed him. That's when the Act of Supremacy and the Act of Succession, crucial to determining who was for and who was against Henry, were passed. Elizabeth Barton was attainted and executed in 1534. Bishop Fisher and Thomas More were imprisoned in 1534. The Treasons Act was passed in 1534. If any year changed Henry VIII, it was 1534--or rather, Henry VIII changed most radically that year and the behaviors he'd developed continued to determine his reaction to opposition and difficulty.

Published on July 01, 2013 23:00

"Vermeer Bist Du Schön": Music and Vermeer in London

Vermeer and Music: The Art of Love and Leisure sounds like a wonderful exhibition at London's National Art Gallery, combining art, artefacts, and music:

Featuring the Academy of Ancient Music as Resident Ensemble

Explore the musical pastimes of the 17th-century Netherlands through this exhibition combining the art of Vermeer and his contemporaries with rare musical instruments, songbooks and live music.

For the first time the National Gallery’s two paintings by Vermeer, A Young Woman standing at a Virginal and A Young Woman seated at a Virginal are brought together with Vermeer’s Guitar Player, which is currently on exceptional loan from the Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood House.

Three days a week visitors can experience live performances in the exhibition space by the Academy of Ancient Music, bringing the paintings to life with music of the period.

Music was one of the most popular themes in Dutch painting, and carried many diverse associations. In portraits, a musical instrument or songbook might suggest the education or social position of the sitter; in scenes of everyday life, it might act as a metaphor for harmony, or a symbol of transience.

The exhibition displays 17th-century virginals (a type of harpsichord), guitars and lutes alongside the paintings to offer unique insights into the painters’ choice of instruments, and the difference between the real instruments and the way in which the painters chose to represent them.

The Guardian provides more background on the exhibition:

Music from instruments such as the harpsichord, viola da gamba and violin will echo around the rooms of the National Gallery's Sainsbury wing to add atmosphere to a new exhibition exploring the importance of music in 17th-century Dutch art and society.

Musicians from the Academy of Ancient Music will perform on the hour three days a week at a small but evocative show, opening on Wednesday, that will have at its heart five paintings by the Delft master Johannes Vermeer. . . .

The show features music-themed paintings from the Dutch golden age in the same rooms as instruments close to what are depicted, including a virginal, a lute and a lavishly decorated guitar, as well as songbooks that would have been carried around in the hope of finding the right moment.

It includes five of the 36 Vermeer paintings that are known to exist: the National Gallery's two Vermeers of women playing virginals, plus The Music Lesson, loaned by the Royal Collection, and The Guitar Player, which has been on loan to the gallery while its normal home, Kenwood House in north London, is closed for restoration. The fifth Vermeer is being loaned by a private collector from New York.

The show's curator, Betsy Wieseman, said music was far more important and pervasive across society in 17th-century Holland than other European countries. "It was a much more enjoyable musical culture in many respects, focusing on songs rather than grandiose compositions and orchestral pieces."

As well as paintings by artists including Jan Steen, Pieter de Hooch and Gerard ter Borch, a final room shows the latest technical examination carried out on Vermeer's works, showing even hidden fingerprints.

And Richard Egarr, the director of the Academy of Ancient Music, describes music-making during Vermeer's time in Holland:

Making music together has always been a way for people to interact, but that's particularly true of the music from Vermeer's time. The first half of the 17th century saw the dense, complex contrapuntal works by 16th century composers such as Palestrina give way to an expressive and freer art form, music based on single clear lines with a highly emotional impact - it's this period too that saw the birth of opera. New ideas about simplicity took hold, and much of the new music being written was for just two players - a melody line that was usually accompanied by a chordal instrument, often a guitar, or a lute. This of course involved both a very intimate level of contact and also allowed room for much spontaneity.

It is this that Vermeer captures so wonderfully in his paintings - the sense of music created in the moment. Perhaps my favourite of his works - Girl Interrupted at Her Music, in New York's Frick Collection, beautifully conveys that singular moment when you're playing music with great partners and you find you're working off each other. Look at her expression, the look she's giving back over her shoulder to the camera, so to speak, which captures perfectly that moment of shared intimacy that's part of music making. And of course part of that intimacy is the flirtation that would have gone on. After all, one of the reasons why music was such an important part of European society at the time was that it was a chance to meet and flirt, especially in such an intimate setting as that of a student and teacher. I think her expression is one of being "caught in the act", something all musicians will recognise! Like with the best photographs, Vermeer's paintings invite thoughts of what's going to happen next, and what has just happened.

I remember when Christopher Hogwood was the director/conductor of the AAM, and we have a few cds with him as conductor.

Featuring the Academy of Ancient Music as Resident Ensemble

Explore the musical pastimes of the 17th-century Netherlands through this exhibition combining the art of Vermeer and his contemporaries with rare musical instruments, songbooks and live music.

For the first time the National Gallery’s two paintings by Vermeer, A Young Woman standing at a Virginal and A Young Woman seated at a Virginal are brought together with Vermeer’s Guitar Player, which is currently on exceptional loan from the Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood House.

Three days a week visitors can experience live performances in the exhibition space by the Academy of Ancient Music, bringing the paintings to life with music of the period.

Music was one of the most popular themes in Dutch painting, and carried many diverse associations. In portraits, a musical instrument or songbook might suggest the education or social position of the sitter; in scenes of everyday life, it might act as a metaphor for harmony, or a symbol of transience.

The exhibition displays 17th-century virginals (a type of harpsichord), guitars and lutes alongside the paintings to offer unique insights into the painters’ choice of instruments, and the difference between the real instruments and the way in which the painters chose to represent them.

The Guardian provides more background on the exhibition:

Music from instruments such as the harpsichord, viola da gamba and violin will echo around the rooms of the National Gallery's Sainsbury wing to add atmosphere to a new exhibition exploring the importance of music in 17th-century Dutch art and society.

Musicians from the Academy of Ancient Music will perform on the hour three days a week at a small but evocative show, opening on Wednesday, that will have at its heart five paintings by the Delft master Johannes Vermeer. . . .

The show features music-themed paintings from the Dutch golden age in the same rooms as instruments close to what are depicted, including a virginal, a lute and a lavishly decorated guitar, as well as songbooks that would have been carried around in the hope of finding the right moment.

It includes five of the 36 Vermeer paintings that are known to exist: the National Gallery's two Vermeers of women playing virginals, plus The Music Lesson, loaned by the Royal Collection, and The Guitar Player, which has been on loan to the gallery while its normal home, Kenwood House in north London, is closed for restoration. The fifth Vermeer is being loaned by a private collector from New York.

The show's curator, Betsy Wieseman, said music was far more important and pervasive across society in 17th-century Holland than other European countries. "It was a much more enjoyable musical culture in many respects, focusing on songs rather than grandiose compositions and orchestral pieces."

As well as paintings by artists including Jan Steen, Pieter de Hooch and Gerard ter Borch, a final room shows the latest technical examination carried out on Vermeer's works, showing even hidden fingerprints.

And Richard Egarr, the director of the Academy of Ancient Music, describes music-making during Vermeer's time in Holland:

Making music together has always been a way for people to interact, but that's particularly true of the music from Vermeer's time. The first half of the 17th century saw the dense, complex contrapuntal works by 16th century composers such as Palestrina give way to an expressive and freer art form, music based on single clear lines with a highly emotional impact - it's this period too that saw the birth of opera. New ideas about simplicity took hold, and much of the new music being written was for just two players - a melody line that was usually accompanied by a chordal instrument, often a guitar, or a lute. This of course involved both a very intimate level of contact and also allowed room for much spontaneity.

It is this that Vermeer captures so wonderfully in his paintings - the sense of music created in the moment. Perhaps my favourite of his works - Girl Interrupted at Her Music, in New York's Frick Collection, beautifully conveys that singular moment when you're playing music with great partners and you find you're working off each other. Look at her expression, the look she's giving back over her shoulder to the camera, so to speak, which captures perfectly that moment of shared intimacy that's part of music making. And of course part of that intimacy is the flirtation that would have gone on. After all, one of the reasons why music was such an important part of European society at the time was that it was a chance to meet and flirt, especially in such an intimate setting as that of a student and teacher. I think her expression is one of being "caught in the act", something all musicians will recognise! Like with the best photographs, Vermeer's paintings invite thoughts of what's going to happen next, and what has just happened.

I remember when Christopher Hogwood was the director/conductor of the AAM, and we have a few cds with him as conductor.

Published on July 01, 2013 22:30

June 30, 2013

July 1 and the Precious Blood: DOMINE JESU REX ET REDEMPTOR PER SANGUINEM TUUM SALVA NOS

Before the 1969 reforms of the Roman Calendar, today was the Feast of the Most Precious Blood. One of the hymns for the feast was:

Before the 1969 reforms of the Roman Calendar, today was the Feast of the Most Precious Blood. One of the hymns for the feast was:Salvete Christi vulnera,

Immensi amoris pignora,

Quibus perennes rivuli

Manant rubentis Sanguinis.

Nitore stellas vincitis,

Rosas odore et balsama,

Pretio lapillos indicos,

Mellis favos dulcedine.

Per vos patet gratissimum

Nostris asylum mentibus,

Non huc furor minantium

Unquam penetrat hostium.

Quot Jesus in Pretorio

Flagella nudus excipit!

Quot scissa pellis undique

Stillat cruoris guttulas!

Frontem venustam, proh dolor!

Corona pungit spinea,

Clavi retusa cuspide

Pedes manusque perforant.

Postquam sed ille tradidit

Amans volensque spiritum,

Pectus feritur lancea,

Geminusque liquor exilit.

Ut plena sit redemptio

Sub torculari stringitur,

Suique Jesus immemor,

Sibi nil reservat Sanguinis.

Venite, quotquot criminum

Funesta labes inficit:

In hoc salutis balneo

Qui se lavat, mundabitur.

Summi ad Parentis dexteram

Sedenti habenda est gratia,

Qui nos redemit Sanguine,

Sanctoque firmat Spiritu.

Which Henry Nutcombe Oxenham translated. According to the old Catholic Encyclopedia, Oxenham, although attracted to the Catholic Church, and defintely High Church, had troubles after his conversion, although he never reverted or left:

An English controversialist and poet, born at Harrow, 15 Nov., 1829; died at Kensington, 23 March, 1888; was the son of the Rev. William Oxenham, second master of Harrow. He was educated at Harrow School and Balliol College, Oxford, taking his degree in 1850. After receiving Anglican orders, he became curate first at Worminghall, in Buckinghamshire, then at St. Bartholomew's, Cripplegate. While at the latter place, he was received into the Church by Monsignor (afterwards Cardinal) Manning. For a time he contemplated becoming a priest, for which purpose he entered St. Edmund's College, Old Hall, but after receiving minor orders, he left: it is said that his reason was that he believed in the validity of Anglican orders, and considered himself already a priest. He continued to dress as an ecclesiastic and in this anomalous position he spent the remainder of his life. His ambition was to work for the reunion of the Anglican with the Catholic Church, with which end in view, he published a sympathetic article, in answer to Pusey's "Eirenicon", in the shape of a letter to his friend and fellow-convert, Father Lockhart . After the Vatican Council his position became still more anomalous, for his unwillingness to accept the doctrine of Papal Infallibility was known. Though influenced by the action of Dr. Döllinger, with whom he was on intimate terms, he never outwardly severed his connexion with the Catholic Church, and before his death received all the sacraments at the hands of Father Lockhart. His published works include: "The Sentence of Kaires and Poems" (3rd ed., London, 1871); Translation of Döllinger's "First Age of Christianity" (London, 1866, 2 vols: two subsequent editions) and "Lectures on Reunion" (London, 1872); "Catholic Eschatology" (1876; new edition, enlarged, 1878); "Memoir of Lieut. Rudolph de Lisle, R. N." (London, 1886); numerous pamphlets and articles, especially in "The Saturday Review", over the initials X. Y. Z.

He tried his vocation at the London Oratory and travelled to Germany for a long stay. Oxenham never married and was 58 when he died. As an aside, it is interesting that Balliol produced some other famous converts to Catholicism: Gerard Manley Hopkins, Hilaire Belloc, Ronald Knox, Graham Greene, and Christopher Hollis. Don't forget that Lord Peter Wimsey attended Balliol too, according to Dorothy L. Sayers!

Westminster Cathedral in London is dedicated to the Precious Blood of Jesus: DOMINE JESU REX ET REDEMPTOR PER SANGUINEM TUUM SALVA NOS (Lord Jesus, King and Redeemer, save us by your blood) !

Published on June 30, 2013 23:00

Two Martyrs (in 1616 and 1681) on the Son Rise Morning Show

I'll be on much earlier than usual on the Son Rise Morning Show today to discuss two martyrs (Blessed Thomas Maxfield and St. Oliver Plunkett)--at 7:20 a.m. Eastern/6:20 a.m.Central:

I'll be on much earlier than usual on the Son Rise Morning Show today to discuss two martyrs (Blessed Thomas Maxfield and St. Oliver Plunkett)--at 7:20 a.m. Eastern/6:20 a.m.Central:July 1, 1616: A martyrdom in London during James I's reign was an event with international implications--the Spanish ambassadors were quite active around this time in pursuing pardons or even exile (knowing the priest would very likely return).

Blessed Thomas Maxfield was born in Stafford gaol, about 1590, martyred at Tyburn, London, Monday, 1 July, 1616. He was one of the younger sons of William Macclesfield of Chesterton and Maer and Aston, Staffordshire (a firm recusant, condemned to death in 1587 for harbouring priests, one of whom was his brother Humphrey), and Ursula, daughter of Francis Roos, of Laxton, Nottinghamshire. William Macclesfield is said to have died in prison and is one of the prætermissi as William Maxfield; but, as his death occurred in 1608, this is doubtful. Thomas arrived at the English College at Douai on 16 march, 1602-3, but had to return to England 17 May, 1610, owing to ill health. In 1614 he went back to Douai, was ordained priest, and in the next year came to London. Within three months of landing he was arrested, and sent to the Gatehouse, Westminster. After about eight months' imprisonment, he tried to escape by a rope let down from the window in his cell, but was captured on reaching the ground. This was at midnight 14-15 June, 1616. For seventy hours he was placed in the stocks in a filthy dungeon at the Gatehouse, and was then on Monday night (17 June) removed to Newgate, where he was set amongst the worst criminals, two of whom he converted. On Wednesday, 26 June, he was brought to the bar at the Old Bailey, and the next day was condemned solely for being a priest, under 27 Eliz., c, 2. The Spanish ambassador* did his best to obtain a pardon, or at least a reprieve; but, finding his efforts unavailing, had solemn exposition of the Blessed Sacrament in his chapel during the martyr's last night on earth. The procession to Tyburn early on the following morning was joined by many devout Spaniards, who, in spite of insults and mockery, persisted in forming a guard of honour for the martyr. Tyburn-tree itself was found decorated with garlands, and the ground round about strewn with sweet herbs. The sheriff ordered the martyr to be cut down alive, but popular feeling was too strong, and the disembowelling did not take place till he was quite senseless.

Downside Abbey, the Tyburn Convent near Marble Arch, and Holy Trinity Catholic in Staffordshire each honor his relics. See this site for a picture of an altar in Holy Trinity depicting the martyr.

*The Spanish Ambassador at that time was Diego Sarmiento de Acuña, 1st Count of Gondomar, who had succeeded in obtaining the release of Luisa de Carvajal in 1614.

Glorious Martyr, St. Oliver,who willingly gave your life for your faith,help us also to be strong in faith.May we be loyal like you to the see of Peter.By your intercession and examplemay all hatred and bitternessbe banished from the hearts of Irish men and women.May the peace of Christ reign in our hearts,as it did in your heart,even at the moment of your death.Pray for us and for Ireland. Amen. July 1, 1681: St. Oliver Plunkett, the Archbishop of Armagh in Ireland, was executed at Tyborn in London on July 1, 1681. He was the last priest to be executed there and the final victim of the "Popish Plot"--that fraudulent, perjured plot cooked up by the BBC's Worst Briton of the 17th Century: Titus Oates.

Glorious Martyr, St. Oliver,who willingly gave your life for your faith,help us also to be strong in faith.May we be loyal like you to the see of Peter.By your intercession and examplemay all hatred and bitternessbe banished from the hearts of Irish men and women.May the peace of Christ reign in our hearts,as it did in your heart,even at the moment of your death.Pray for us and for Ireland. Amen. July 1, 1681: St. Oliver Plunkett, the Archbishop of Armagh in Ireland, was executed at Tyborn in London on July 1, 1681. He was the last priest to be executed there and the final victim of the "Popish Plot"--that fraudulent, perjured plot cooked up by the BBC's Worst Briton of the 17th Century: Titus Oates.So in the Catholic dioceses of England and Wales AND Ireland, today is the memorial/feast of St. Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, victim of Stuart injustice during the Anti-Catholic madness of Oates' fake plot.

The Whigs in Parliament, opposed most of all to the succession of Charles II's Catholic brother, James the Duke of York, jumped at the opportunity to attack Catholics--and James--when Titus Oates fabricated the story of a great conspiracy. Charles II did not believe most of the elements of the plot Oates "revealed", especially when the perjuror implicated his own queen, Catherine of Braganza, and his brother.

Once Oates was able to compound English fear of Jesuits and Catholics with English fear of Irish Catholics, Plunkett was in grave danger. St. Oliver Plunkett was brought to London from Ireland and accused of conspiring to bring French soldiers and recruit members of his diocese to mount a rebellion against the King and Parliament. There was, of course, no evidence of these accusations and Plunkett could bring no witnesses to testify for him--they were in Ireland and not permitted to come to England. He had been tried before in Ireland--no double jeopardy applied here--and English authorities like Shaftesbury were convinced that no Irish jury (even if packed with Protestants) would convict him.

On the day of his execution he was able to give a long discourse, in which he re-presented the evidence that proved he was not involved in any conspiracy, and which concluded with forgiveness and prayers:

as one of the said deacons (to wit, holy Stephen) did pray for those who stoned him to death; so do I, for those who, with perjuries, spill my innocent blood; saying, as St. Stephen did, "O Lord! lay not this sin to them." I do heartily forgive them, and also the judges, who, by denying me sufficient time to bring my records and witnesses from Ireland, did expose my life to evident danger. I do also forgive all those, who had a hand, in bringing me from Ireland, to be tried here; where it was morally impossible for me to have a fair trial. I do finally forgive all who did concur, directly or indirectly, to take away my life; and I ask forgiveness of all those whom I ever offended by thought, word, or deed.

I beseech the All-powerful, that his Divine Majesty grant our king, queen, and the duke of York, and all the royal family, health, long life, and all prosperity in this world and in the next, everlasting felicity.

Now, that 1 have shewed sufficiently (as I think) how innocent I am of any plot or conspiracy: I would I were able, with the like truth, to clear myself of high crimes committed against the Divine Majesty's commandments, often transgressed by me, for which, I am sorry with all my heart; and if I should or could live a thousand years, I have a firm resolution, and a strong purpose, by your grace, O my God! never to offend you; and I beseech your Divine Majesty, by the merits of Christ, and by the intercession of his Blessed Mother, and all the holy angels and saints, to forgive me my sins, and to grant my soul eternal rest. Miserere mei Deus, etc. Parce anima, etc. In manus tuas, etc.

St. Oliver Plunkett was born in 1629 in Loughcrew, County Meath, Ireland of well-to-do parents and studied for the priesthood at the Irish College in Rome. While Oliver Cromwell was inflicting the "righteous judgement of God" on the Irish who had rebelled against English rule during Charles I's reign, Plunkett had been unable to return to serve his people as a priest after ordination in 1654. He therefore remained in Rome and taught theology. In 1669 he was appointed the Archbishop of Armagh and the Primate of All Ireland and finally returned to Ireland the next year. For a time, Charles II's Restoration leniency allowed Plunkett to accomplish many reforms and reorganizations in education and catechesis. As Archbishop, he confirmed thousands (48,000!) but in 1673, persecution of Catholics in England's colony forced him to go into hiding and close the schools. Arrested in connection with Oates' plot, he was imprisoned at Dublin Castle. He was canonized by Pope Paul VI in 1975 and in 1997 he was named the Patron Saint of Peace and Reconciliation in Ireland. His trial and execution were so manifestly unfair that even Shaftesbury realized things had gone too far--yet, with the Popish Plot's true conspirators, Oates and companions, finally being mistrusted and the whole matter winding down, Charles II did nothing to stop the execution of St. Oliver Plunkett. This site contains a wealth of information, including the prayers and readings for a Mass honoring his Feast.

When Pope Paul VI canonized the martyr, he began his remarks in Gaelic: Dia's muire Dhíbh, a chlann Phádraig! Céad mile fáilte rómhaibh! Tá Naomh nua againn inniu: Comharba Phádraig, Olibhéar Naofa Ploinéad. (God and Mary be with you, family of Saint Patrick! A hundred thousand welcomes! We have a new Saint today: the successor of Saint Patrick, Saint Oliver Plunkett). Today, Venerable Brothers and dear sons and daughters, the Church celebrates the highest expression of love-the supreme measure of Christian and pastoral charity. Today, the Church rejoices with a great joy, because the sacrificial love of Jesus Christ, the Good Shepherd, is reflected and manifested in a new Saint. And this new Saint is Oliver Plunkett, Bishop and Martyr-Oliver Plunkett, successor of Saint Patrick in the See of Armagh-Oliver Plunkett , glory of Ireland and Saint, today and for ever, of the Church of God, Oliver Plunkett is for all-for the entire world-an authentic and outstanding example of the love of Christ. And on our part we bow down today to venerate his sacred relics, just as on former occasions we have personally knelt in prayer and admiration at this shrine in Drogheda.

Published on June 30, 2013 22:00

June 29, 2013

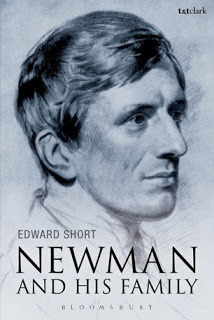

Book Preview: Newman and His Family

I reviewed Edward Short's first book on Blessed John Henry Newman, Newman and His Contemporaries, last year. His second book is due out on August 15--the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. According to the publisher:

I reviewed Edward Short's first book on Blessed John Henry Newman, Newman and His Contemporaries, last year. His second book is due out on August 15--the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. According to the publisher:A study in family history and influence, Newman and his Family looks at how John Henry Newman (1801-90), the priest, educator, theologian, philosopher, novelist, poet and satirist both learned from and was transformed by his parents and his brothers and sisters. The son of a banker in the City of London and a Huguenot mother whose family were famous and innovative paper makers and printers, Newman was the eldest of six children, two boys and three girls--Charles, Harriett, Frank, Jemima and Mary. While the family was reared Anglican, Charles abandoned Christianity for Owenite Socialism and Frank ended his days a Unitarian. Although Mary died young, she had a profound influence on her brother, as did Harriett, who could never reconcile herself to her brother’s conversion. Jemima was also opposed to his conversion, though she lived long enough to witness (from afar) his strange, tumultuous new life as a Catholic. At the same time, since none of the family followed their eldest brother into the Catholic Church, to which Newman converted in 1845, the book also explores the limitations of Newman’s influence and the ways in which family differences led him to a deeper understanding of such themes as home and ostracism, failure and faith, conversion and apostasy, disunity and prayer, infirmity and love.

Based on Newman’s vast correspondence and the correspondence of his different family members, as well as on his published and unpublished writings, Newman and his Family presents the great religious thinker in a freshly personal light, where he can be seen sharing his theological and philosophical convictions directly with those to whom he was most closely tied. While there are excellent studies available on different aspects of Newman and his work, this is the first full-length study to show how the difficulties and heartbreaks inherent in family life helped Newman to understand not only himself and his contemporaries but his deeply personal Christian faith.

Table of Contents: Introduction/ 1. Father and Son/ 2. Mrs. Newman and Amor Matris/ 3. Charles Newman and the Idea of Socialism/ 4. Frank Newman and the Search for Truth/ 5. Mary Newman and the World to Come/ 6. Harriet Newman and English Anti-Romanism/ 7. Jemima Newman and the Misery of Difference/ 8. James Rickards Mozley and Late Victorian Scepticism/ Conclusion: Family, Faith and Love

More about the author and his work here. I look forward to reading this book! (The author has kindly offered to send me a review copy.)

Published on June 29, 2013 22:30

June 28, 2013

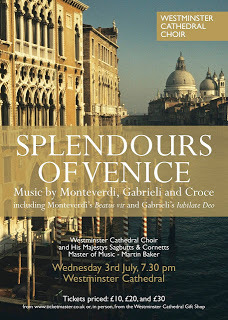

A Concert Not to Be Missed!--But I'll Miss It!!

The New Liturgical Movement blog highlights this concert:

A concert not to be missed: 'Splendours of Venice' is an opportunity to hear the Choir of Westminster Cathedral join forces with His Majestys Sagbutts and Cornetts in a celebration of choral and instrumental music by composers with strong Venetian associations. Monteverdi, Giovanni Gabrieli, Croce, Merulo, Hassler, Grillo, Frescobaldi and Guami are all represented, and Motets in 4, 8, 12 and 16 parts are interspersed with movements from Monteverdi's Mass (published in 1651), his five-part Beatus vir and eight-part Magnificat. Westminster Cathedral is the perfect setting, its Byzantine styling very much a visual echo of San Marco, and the siting of singers in the galleries and the use of the Cathedral's organs will provide dramatic effect.

Full programme:

Iubilate Deo, Giovanni Gabrieli

Gloria (1651 Mass), Monteverdi

Toccata quarta del secondo tuono (Primo libro), Merulo

Beatus vir, Monteverdi

Canzon Terza à 8, Grillo

In spiritu humilitatis, Croce

Hassler Canzon Duodecimitoni à 8, Hassler

Sanctus (1651 Mass), Monteverdi

Toccata Cromaticha per l'Elevatione (Messa della Domenica - Fiori Musicali), Frescobaldi

Agnus Dei (1651 Mass), Monteverdi

O sacrum convivium, Hassler

Canzon La Lucchesina à 8, Guami

Magnificat a 8, Monteverdi

Canzon Terza à 6, Giovanni Gabrieli

Plaudite omnis terra, Giovanni Gabrieli

Omnes gentes plaudite, Giovanni Gabrieli

Published on June 28, 2013 22:30

June 27, 2013

Around the World with the Wichita Public Library

My husband and I have vicariously visited four European capitals in the past couple of weeks: Paris, London, Rome, and Prague--via Naxos Musical Journey DVDs combining video of famous sights in each city with appropriate classical music. We thought two were very effective and two less effective. We have been to all but one of the cities, Prague.

The DVD on Paris, which also includes Chantilly, Versailles, and Chartres, was one of the effective presentations, with scenes from all the famous sights, including Notre Dame, the Musee D'Orsay, Sacre Coeur, etc, and of families in the parks at Luxembourg, the interior of Le Train Bleu in the Gare de Lyon (we ate dinner there twice on business trips to Paris). Good detail in Chantilly, Versailles, and Chartres, too. The music ranges from Marais to Wagner; Mozart to Satie; Meyerbeer to Puccini--all appropriately chosen for the venue and choreography of the video presentation.

The DVD on Paris, which also includes Chantilly, Versailles, and Chartres, was one of the effective presentations, with scenes from all the famous sights, including Notre Dame, the Musee D'Orsay, Sacre Coeur, etc, and of families in the parks at Luxembourg, the interior of Le Train Bleu in the Gare de Lyon (we ate dinner there twice on business trips to Paris). Good detail in Chantilly, Versailles, and Chartres, too. The music ranges from Marais to Wagner; Mozart to Satie; Meyerbeer to Puccini--all appropriately chosen for the venue and choreography of the video presentation.

The DVD on Rome we thought less effective, primarily because the video concentrated so much on street scenes, the Spanish Steps (we thought we'd never stop seeing them), and did not even visit all four major basilicas in Rome--no St. Mary Major, St. Paul Outside the Walls or St. John Lateran at all. The views of the Roman Forum were effective. The musical selections were great, however:

The music here included is all associated in one way or another with Rome and its traditions. It ranges from the overture to Mozart's Roman opera La clemenza di Tito to Wagner's Tannhäuser, whose hero seeks pardon for his sins in the Eternal City, from Puccini's opera Tosca, set in Rome dominated by a corrupt chief of police, to Berlioz's evocation of the city in the age of Benevenuto Cellini, his Roman Carnival Overture.

Again, the DVD for London we thought was great: lots of sights, including both Westminster Cathedral and Westminster Abbey and the bonus of Oxford, including Christ Church and Christ Church Cathedral. The music was beautiful, with many selections from the Enigma Variations by Elgar, including "Nimrod" during the scenes of Christ Church. The Verdi selection was interesting--the chorus of the Scottish Exiles from Macbeth (accompanying images of the Tower of London). The video ends with a bang: fireworks and Handel's Music for the Royal Fireworks!

Again, the DVD for London we thought was great: lots of sights, including both Westminster Cathedral and Westminster Abbey and the bonus of Oxford, including Christ Church and Christ Church Cathedral. The music was beautiful, with many selections from the Enigma Variations by Elgar, including "Nimrod" during the scenes of Christ Church. The Verdi selection was interesting--the chorus of the Scottish Exiles from Macbeth (accompanying images of the Tower of London). The video ends with a bang: fireworks and Handel's Music for the Royal Fireworks!

But the DVD for Prague seemed a little dull--not even a good view of the Charles Bridge! The video did include many beautiful scenes along the river and of countryside and parks--and again, the music was great:

The music included here is associated in one way or another with Prague or Bohemia. It includes works by the Bohemian composers Smetana and Dvořák, by the Moravian composer Janáček, and by Fibich who, with Mozart, always found a ready welcome for his music in Prague.

There are more DVDs in the series, including Salzburg (lots of Mozart), Vienna, and Madrid, and DVDs that encompass highlights from the entire country, like Finland, Germany, and Uzbekistan, as well as two videos dedicated to regions of France, the chateaus of the Loire and Brittany & Normandy--the easy way to armchair travel, without luggage or crowds, or really being there!

The DVD on Paris, which also includes Chantilly, Versailles, and Chartres, was one of the effective presentations, with scenes from all the famous sights, including Notre Dame, the Musee D'Orsay, Sacre Coeur, etc, and of families in the parks at Luxembourg, the interior of Le Train Bleu in the Gare de Lyon (we ate dinner there twice on business trips to Paris). Good detail in Chantilly, Versailles, and Chartres, too. The music ranges from Marais to Wagner; Mozart to Satie; Meyerbeer to Puccini--all appropriately chosen for the venue and choreography of the video presentation.

The DVD on Paris, which also includes Chantilly, Versailles, and Chartres, was one of the effective presentations, with scenes from all the famous sights, including Notre Dame, the Musee D'Orsay, Sacre Coeur, etc, and of families in the parks at Luxembourg, the interior of Le Train Bleu in the Gare de Lyon (we ate dinner there twice on business trips to Paris). Good detail in Chantilly, Versailles, and Chartres, too. The music ranges from Marais to Wagner; Mozart to Satie; Meyerbeer to Puccini--all appropriately chosen for the venue and choreography of the video presentation.The DVD on Rome we thought less effective, primarily because the video concentrated so much on street scenes, the Spanish Steps (we thought we'd never stop seeing them), and did not even visit all four major basilicas in Rome--no St. Mary Major, St. Paul Outside the Walls or St. John Lateran at all. The views of the Roman Forum were effective. The musical selections were great, however:

The music here included is all associated in one way or another with Rome and its traditions. It ranges from the overture to Mozart's Roman opera La clemenza di Tito to Wagner's Tannhäuser, whose hero seeks pardon for his sins in the Eternal City, from Puccini's opera Tosca, set in Rome dominated by a corrupt chief of police, to Berlioz's evocation of the city in the age of Benevenuto Cellini, his Roman Carnival Overture.

Again, the DVD for London we thought was great: lots of sights, including both Westminster Cathedral and Westminster Abbey and the bonus of Oxford, including Christ Church and Christ Church Cathedral. The music was beautiful, with many selections from the Enigma Variations by Elgar, including "Nimrod" during the scenes of Christ Church. The Verdi selection was interesting--the chorus of the Scottish Exiles from Macbeth (accompanying images of the Tower of London). The video ends with a bang: fireworks and Handel's Music for the Royal Fireworks!

Again, the DVD for London we thought was great: lots of sights, including both Westminster Cathedral and Westminster Abbey and the bonus of Oxford, including Christ Church and Christ Church Cathedral. The music was beautiful, with many selections from the Enigma Variations by Elgar, including "Nimrod" during the scenes of Christ Church. The Verdi selection was interesting--the chorus of the Scottish Exiles from Macbeth (accompanying images of the Tower of London). The video ends with a bang: fireworks and Handel's Music for the Royal Fireworks!But the DVD for Prague seemed a little dull--not even a good view of the Charles Bridge! The video did include many beautiful scenes along the river and of countryside and parks--and again, the music was great:

The music included here is associated in one way or another with Prague or Bohemia. It includes works by the Bohemian composers Smetana and Dvořák, by the Moravian composer Janáček, and by Fibich who, with Mozart, always found a ready welcome for his music in Prague.

There are more DVDs in the series, including Salzburg (lots of Mozart), Vienna, and Madrid, and DVDs that encompass highlights from the entire country, like Finland, Germany, and Uzbekistan, as well as two videos dedicated to regions of France, the chateaus of the Loire and Brittany & Normandy--the easy way to armchair travel, without luggage or crowds, or really being there!

Published on June 27, 2013 22:30

June 26, 2013

St. John Southworth, Martyr of Westminster

Father John Southworth came from a Lancashire family who lived at Samlesbury Hall. They chose to pay heavy fines rather than give up the Catholic faith.

Father John Southworth came from a Lancashire family who lived at Samlesbury Hall. They chose to pay heavy fines rather than give up the Catholic faith.He studied at the English College in Douai, now in northern France, (and then moved to Hertfordshire, St Edmunds College) and was ordained priest before he returned to England. Imprisoned and sentenced to death for professing the Catholic faith, he was later deported to France, with the help of Queen Henrietta Maria--he had at first been imprisoned with St. Edmund Arrowsmith in Lancaster and witnessed that martyr's death; then he was moved to The Clink in London and then exiled. Once more he returned to England and lived in Clerkenwell, London, during a plague epidemic, working along with St. Henry Morse. He assisted and converted the sick in Westminster and was arrested again.

He was again arrested under the Interregnum and was tried at the Old Bailey under Elizabethan anti-priest legislation . He pleaded guilty to exercising the priesthood and was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. At his execution at Tyburn, London, he suffered the full pains of his sentence and was hanged, drawn and quartered. He was allowed to speak before his sentence was carried out. Among his last words:

“My faith and obedience to my superiors is all the treason charged against me; nay, I die for Christ’s law, which no human law, by whomsoever made, ought to withstand or contradict… To follow His holy doctrine and imitate His holy death, I willingly suffer at present; this gallows I look on as His Cross, which I gladly take to follow my Dear Saviour…I plead not for myself…but for you poor persecuted Catholics whom I leave behind me.

"My faith is my crime, the performance of my duty the occasion of my condemnation. I confess I am a great sinner; against God I have offended, but am innocent of any sin against man, I mean the Commonwealth, and the present Government."

The Venetian Secretary reported on his execution: he was hung, and was not dead when the executioner "cut out his heart and entrails and threw them into a fire kindled for the purpose, the body being quartered . . . Such is the inhuman cruelty used towards the English Catholic religious."

The Spanish ambassador returned his corpse to Douai for burial. His corpse was sewn together and parboiled, to preserve it. Following the French Revolution, his body was buried in an unmarked grave for its protection. The grave was discovered in 1927 and his remains were returned to England. They are now kept in the Chapel of St George and the English Martyrs in Westminster Cathedral in London. He was beatified in 1929. In 1970, he was canonized by Pope Paul VI as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales. His feast day is 27 June but this is only celebrated in the Westminster diocese.

Published on June 26, 2013 22:30

June 25, 2013

A Requiem for Today?

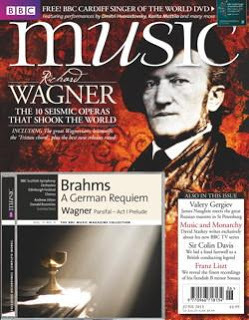

When Colin Davis died earlier this year, I posted several movements from Mozart's Requiem on facebook, because I have enjoyed listening to his recording of Mozart's Requiem for years. Last month's BBC Music Magazine featured a free disc of Brahms' A German Requiem, which is not based upon the Catholic Mass at all, but upon texts Brahms selected from Luther's Bible. The booklet with the CD notes that Brahms wrote the Requiem after his mother's death, but that he did not believe in an afterlife at all. The Catholic Requiem Mass is offered for the repose of the soul of the deceased, but Brahms wrote for the consolation of the living, the surviving, mourning, relatives and friends of the deceased--there's no Judgment, and no resurrection of the dead, either; no Heaven or Hell.

When Colin Davis died earlier this year, I posted several movements from Mozart's Requiem on facebook, because I have enjoyed listening to his recording of Mozart's Requiem for years. Last month's BBC Music Magazine featured a free disc of Brahms' A German Requiem, which is not based upon the Catholic Mass at all, but upon texts Brahms selected from Luther's Bible. The booklet with the CD notes that Brahms wrote the Requiem after his mother's death, but that he did not believe in an afterlife at all. The Catholic Requiem Mass is offered for the repose of the soul of the deceased, but Brahms wrote for the consolation of the living, the surviving, mourning, relatives and friends of the deceased--there's no Judgment, and no resurrection of the dead, either; no Heaven or Hell.Listening to Brahms' Ein Deutsches Requiem for the first time, I did not really hear the words, but the music is beautiful, so often serene. This site notes that the work did not succeed very well when performed in Catholic countries, but was accepted in England and the USA immediately:

Following the paradigm of reception that we have set up for Germany -- the fact that Catholic towns were far more resistant to the Requiem than their Protestant counterparts -- it comes as no surprise to learn that the Requiem was considerably better received in England and the United States than in Catholic countries such as France and Italy. Indeed, we have little documentation of any reception whatsoever in these countries; in England, on the other hand, reviews, commentary, and performances were abundant from 1871 onwards. There is some statistical disagreement about the number of performances of the Requiem in Europe during Brahms' lifetime: while Musgrave cites the figure of 79 performances outside Germany between 1869 and 1876, Kalbeck reports 85 performances between 1867 and 1876

Because it does not pray for the dead or cover those issues of judgment and eternity, Brahms' work is very suited to a more secular age--note this story about the MIT community gathering to perform it after the Boston Marathon bombings:

Unlike other requiems, Brahms wrote his as a comfort for the living. That’s another reason why Buckley wanted to perform it. She said traditional requiems are based on the Latin Mass for the dead.

“One of those texts is about the day of judgment, the day of wrath. So they’re beautiful pieces of music — I mean who doesn’t love the Mozart Requiem? But I think that the Brahms is extra special,” Buckley said. “The connection to his mother is important, and the fact that he chose the text from Luther’s translation of the bible. He believed no text is in judgment of the dead.”

So plans for this massive singing event were set midweek.

Reading the texts Brahms selected does emphasize the comfort, peace and assurance Ein Deutsches Requiem offers--but I did see that he does mention the Resurrection of the Dead:

Behold, I show you a mystery:

We shall not all sleep,

but we all shall be changed

and suddenly, in a moment,

at the sound of the last trombone.

For the trombone shall sound,

and the dead shall be raised incorruptible,

and we shall be changed.

Then shall be fulfilled

The word that is written:

Death is swallowed up in victory.

O Death, where is thy sting?

O Hell, where is thy victory?

Fascinating. I'll have to listen to it again.

Published on June 25, 2013 22:30

June 24, 2013

Dates in June, 1509 and 1529

In addition to being the Feast of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist, yesterday was also the 504th anniversary of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon's coronation in 1509. They had been married in a quiet ceremony in the chapel at Greenwich on June 11. It was also in June, 20 years later (on the 21st) that Catherine of Aragon appeared the legatine court to defend the validity of that wedding day and marriage.

I cannot help but think of the juxtaposition of these dates in June, separated by momentous years and events. In June of 1509, Catherine and Henry were wed and crowned; 20 years later Catherine appeared in a court to try the validity of her marriage; six years after that dramatic trial, one of her strongest defenders was executed when Bishop John Fisher opposed the king's supremacy.

Garrett Mattingly notes in his biography of Catherine of Aragon, "It is hard to imagine Henry and Catherine at their coronation. Their images are pale as ghosts beside their later selves . . ." In 1509, Henry was young, tall, an athlete with a ruddy round-cheeked face, while Catherine was fresh, delicate, sweet and winsome. As Mattingly notes, "The Londoners thought her bonny . . . Henry thought her bonnier than any."

But in 1509, the month of June was filled, as Mattingly comments, with festivity, music, laughter, and dancing. The reign of Henry the Eighth and Catherine of Aragon had begun. As this website notes, everyone had great hopes:

After the serious solemnity of the ceremony came the party. An enormous feast was enjoyed by all the guests in Westminster Hall and continued long into the night. Further celebrations spilled over into the following days and included, dancing, concerts and jousting. The new king, Henry VIII, had not disappointed. He had confirmed the guests’ belief that this gregarious Prince knew how to celebrate like a King.

The poet, and former tutor of Henry, John Skelton, produced poetry to be read or sung during the celebrations. Skelton’s writing demonstrated that he believed the new King would always be fair and protect his people. However, the full extent of the joy experienced by the English on this day is beautifully surmised by a letter sent from Lord Mountjoy to the renowned Dutch Scholar, Erasmus: “Heaven and earth rejoices, everything is full of milk and honey and nectar. Avarice has fled the country. Our King is not after gold, or gems, or precious metals, but virtue, glory, immortality.”

This was unquestionably the feeling of the King as well as his people, for Henry was already looking towards the legend of King Arthur and the example of his own ancestor (and victor at the battle of Agincourt), Henry V, for his Royal inspiration.

And without doubt Henry’s need for glory and immortality would change England forever.

On June 21, 1529, a Papal Legatine court was held to determine the issue of Henry VIII’s request to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Cardinal Thomas Wolsey and Cardinal Campeggio (the Cardinal Protector of England and Legate) from Rome convened the court at Blackfriar’s but Catherine circumvented their plans by speaking directly to Henry, asking for his mercy, and protesting at the unfairness of the proceedings.

On June 21, 1529, a Papal Legatine court was held to determine the issue of Henry VIII’s request to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Cardinal Thomas Wolsey and Cardinal Campeggio (the Cardinal Protector of England and Legate) from Rome convened the court at Blackfriar’s but Catherine circumvented their plans by speaking directly to Henry, asking for his mercy, and protesting at the unfairness of the proceedings.In Shakespeare’s play, The Famous History of the Life of King Henry the Eight, she says:

QUEEN CATHERINE

Sir, I desire you do me right and justice;

And to bestow your pity on me: for

I am a most poor woman, and a stranger,

Born out of your dominions; having here

No judge indifferent, nor no more assurance

Of equal friendship and proceeding. Alas, sir,

In what have I offended you? what cause

Hath my behavior given to your displeasure,

That thus you should proceed to put me off,

And take your good grace from me?

Heaven witness,I have been to you a true and humble wife,

At all times to your will conformable;

Ever in fear to kindle your dislike,

Yea, subject to your countenance, glad or sorry

As I saw it inclined: when was the hour

I ever contradicted your desire,

Or made it not mine too? Or which of your friends

Have I not strove to love, although I knew

He were mine enemy? what friend of mine

That had to him derived your anger, did I

Continue in my liking? nay, gave notice

He was from thence discharged. Sir, call to mind

That I have been your wife, in this obedience,

Upward of twenty years, and have been blest

With many children by you: if, in the course

And process of this time, you can report,

And prove it too, against mine honour aught,

My bond to wedlock, or my love and duty,

Against your sacred person, in God's name,

Turn me away; and let the foul'st contempt

Shut door upon me, and so give me up

To the sharp'st kind of justice. Please you sir,

The king, your father, was reputed for

A prince most prudent, of an excellent

And unmatch'd wit and judgment: Ferdinand,

My father, king of Spain, was reckon'd one

The wisest prince that there had reign'd by many

A year before: it is not to be question'd

That they had gather'd a wise council to them

Of every realm, that did debate this business,

Who deem'd our marriage lawful: wherefore I humbly

Beseech you, sir, to spare me, till I may

Be by my friends in Spain advised; whose counsel

I will implore: if not, i' the name of God,

Your pleasure be fulfill'd!

Henry does not answer her; instead the two Cardinals and Catherine exchange comments about the fairness of the court and Wolsey’s influence on the king.

When she leaves the room, Henry does address her—his speech must reflect Catherine’s lingering popularity and good reputation in England in 1613 or so, when we know the play was performed at the Globe Theatre (a cannon shot caused the theatre to burn down!)

KING HENRY VIII Go thy ways, Kate:

That man i' the world who shall report he has

A better wife, let him in nought be trusted,

For speaking false in that: thou art, alone,

If thy rare qualities, sweet gentleness,

Thy meekness saint-like, wife-like government,

Obeying in commanding, and thy parts

Sovereign and pious else, could speak thee out,

The queen of earthly queens: she's noble born;

And, like her true nobility, she has

Carried herself towards me.

He then goes on to explain his doubts about the validity of their marriage, based in part upon the fact that Catherine never bore a son who survived the womb. This is of course incorrect, as their son Henry, Prince of Wales, died 52 days after birth on the lst of January 1511. Exactly as it occurred in 1529, the scene concludes with Cardinal Campegio declaring the court cannot proceed without Catherine present.

Anne Boleyn appears only briefly in the play and speaks in only one scene, also in very respectful tones about Catherine of Aragon. Anne Bullen, as she is billed, denies that she really wants to be queen herself, although her attendant (“Old Lady”) is cynical about that.

Published on June 24, 2013 23:00