Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 282

February 18, 2013

Cancelling and Rescheduling!

Yesterday was quite a day: First I heard that Father Ian Ker is ill and unable to come to Wichita for the Cardinal Newman Lecture at Newman University--so that event was cancelled. We were looking forward to seeing him again very much, because we were to join some other friends for dinner with Father Ker after the lecture!

Then late last night, I heard that Teresa Tomeo's Catholic Connection would not be live on the air today because Teresa is ill! This morning's 8:15 am.. EST/7:15 a.m. CST interview about the Catholic Martyrs of England pilgrimage will be postponed until tomorrow (Wednesday, February 20) at the same time!

I'll keep you updated on this ever-changing schedule!

In anticipation of St. Robert Southwell's feast this week, here's a poem about time and change:

Times Go by Turns

By Robert Southwell

THE lopped tree in time may grow again,

Most naked plants renew both fruit and flower;

The sorriest wight may find release of pain,

The driest soil suck in some moistening shower.

Times go by turns, and chances change by course,

From foul to fair, from better hap to worse.

The sea of Fortune doth not ever flow,

She draws her favours to the lowest ebb.

Her tides hath equal times to come and go,

Her loom doth weave the fine and coarsest web.

No joy so great but runneth to an end,

No hap so hard but may in fine amend.

Not always fall of leaf, nor ever spring,

No endless night, yet not eternal day;

The saddest birds a season find to sing,

The roughest storm a calm may soon allay.

Thus, with succeeding turns, God tempereth all,

That man may hope to rise, yet fear to fall.

A chance may win that by mischance was lost;

The net, that holds no great, takes little fish;

In some things all, in all things none are crossed;

Few all they need, but none have all they wish.

Unmeddled joys here to no man befall;

Who least, hath some; who most, hath never all.

Then late last night, I heard that Teresa Tomeo's Catholic Connection would not be live on the air today because Teresa is ill! This morning's 8:15 am.. EST/7:15 a.m. CST interview about the Catholic Martyrs of England pilgrimage will be postponed until tomorrow (Wednesday, February 20) at the same time!

I'll keep you updated on this ever-changing schedule!

In anticipation of St. Robert Southwell's feast this week, here's a poem about time and change:

Times Go by Turns

By Robert Southwell

THE lopped tree in time may grow again,

Most naked plants renew both fruit and flower;

The sorriest wight may find release of pain,

The driest soil suck in some moistening shower.

Times go by turns, and chances change by course,

From foul to fair, from better hap to worse.

The sea of Fortune doth not ever flow,

She draws her favours to the lowest ebb.

Her tides hath equal times to come and go,

Her loom doth weave the fine and coarsest web.

No joy so great but runneth to an end,

No hap so hard but may in fine amend.

Not always fall of leaf, nor ever spring,

No endless night, yet not eternal day;

The saddest birds a season find to sing,

The roughest storm a calm may soon allay.

Thus, with succeeding turns, God tempereth all,

That man may hope to rise, yet fear to fall.

A chance may win that by mischance was lost;

The net, that holds no great, takes little fish;

In some things all, in all things none are crossed;

Few all they need, but none have all they wish.

Unmeddled joys here to no man befall;

Who least, hath some; who most, hath never all.

Published on February 18, 2013 22:30

February 17, 2013

The Butt of Malmsey in the Tower of London

CLARENCE: O, I have passed a miserable night,

So full of fearful dreams, of ugly sights,

That, as I am a Christian faithful man,

I would not spend another such night

Though 'twere to buy a world of happy days--

So full of dismal terror was the time.

Methoughts that I had broken from the Tower

And was embarked to cross the Bergundy,

And in my company my brother Gloucester,

Who from my cabin tempted me to walk

Upon the hatches: thence we looked toward England

And cited up a thousand heavy times,

During the wars of York and Lancaster,

That had befall'n us. As we paced along

Upon the giddy footing of the hatches,

Methought that Gloucester stumblèd, and in falling

Struck me (that thought to stay him) overboard

Into the tumbling billows of the main.

O Lord! methought what pain it was to drown!

What dreadful noise of waters in mine ears!

What sights of ugly death within mine eyes!

Methoughts I saw a thousand fearful wracks;

A thousand men that fishes gnawed upon;

Wedges of gold, great anchors, heaps of pearl,

Inestimable stones, unvaluèd jewels,

All scatt'red in the bottom of the sea:

Some lay in dead men's skulls, and in the holes

Where eyes did once inhabit, there were crept

(As 'twere in scorn of eyes) reflecting gems,

That wooed the slimy bottom of the deep

And mocked the dead bones that lay scatt'red by.

I passed (methought) the melancholy flood,

With that sour ferryman which poets write of,

Unto the kingdom of perpetual night.

The first that there did greet my stranger soul

Was my great father-in-law, renownèd Warwick,

Who spake aloud, 'What scourge for perjury

Can this dark monarchy afford false Clarence?'

And so he vanished. Then came wand'ring by

A shadow like an angel, with bright hair

Dabbled in blood, and he shrieked aloud,

'Clarence is come -- false, fleeting, perjured Clarence,

That stabbed me in the field by Tewkesbury:

Seize on him, Furies, take him unto torment!'

With that (methoughts) a legion of foul fiends

Environed me, and howlèd in mine ears

Such hideous cries that with the very noise

I, trembling, waked, and for a season after

Could not believe but that I was in hell,

Such terrible impression made my dream. (Richard III, Act 1, scene iv)

George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence, Earl of Warwick, Earl of Salisbury, and Lord of Richmond; brother of King Edward IV and King Richard III, died in the Tower of London on February 18, 1478--murdered and drowned in a butt of malmsey wine, at least according to Shakespeare. He was the third son of Richard of York, the great-grandson of Edward III and Cecily Neville. He had married Isabella Neville, daughter of the Kingmaker, Richard Neville, the Earl of Warwick (she died in 1476). Thus their two surviving children, Margaret and Edward, were left to the care of their aunt, Anne Neville until she died in 1485. Both of his children would also be imprisoned in the Tower and taken from it to be executed by the victorious Tudors:

--Margaret Pole, 8th Countess of Salisbury (14 August 1473 – 27 May 1541). Married Sir Richard Pole; executed by Henry VIII.

--Edward Plantagenet, 17th Earl of Warwick (25 February 1475 – 28 November 1499). Executed by Henry VII for attempting to escape the Tower of London, in connection with the pretender, Perkin Warbeck. Evidently, his close confinement for so many years had made him most naive and unworldly. With his execution, the male line of the House of York was finished.

--Edward Plantagenet, 17th Earl of Warwick (25 February 1475 – 28 November 1499). Executed by Henry VII for attempting to escape the Tower of London, in connection with the pretender, Perkin Warbeck. Evidently, his close confinement for so many years had made him most naive and unworldly. With his execution, the male line of the House of York was finished.His older sister would certainly learn more about the world, marrying Henry VII's cousin, Sir Richard Pole, a Welsh Knight so that her Plantagenet claim to the throne would be diminished. (Shakespeare ascribes that arranged marriage to Richard III: "The son of Clarence have I pent up close; /His daughter meanly have I match'd in marriage" (Richard III, Act IV, scene 3). And her sons and daughters would learn much too--as the third generation of her family suffered in the Tower of London.

Published on February 17, 2013 22:30

February 16, 2013

Happy 125th Birthday, Ronald Knox!

Baronius Press has a major announcement:

Baronius Press has a major announcement:In celebration of the 125th anniversary of the birthday of Ronald Knox on the 17th February 2013, Baronius Press announced today that the text of the Knox Bible translation will be published on Newadvent.org — one of the largest Catholic websites in the English speaking world.

Baronius Press’ editor in chief Dr. John Newton said: "Since this edition came back into print — after an absence from our shelves of many decades — it has again been lauded as one of the finest 20th century Bible translation by Cardinals, Bishops and biblical experts alike. The clarity and beauty of this translation will help Catholics to deepen their faith and knowledge of scripture, especially during this year of Faith."

Kevin Knight of New Advent said he was delighted to be able to offer the Knox Bible to his readers. He commented: "We are happy to be able to offer the Knox Bible translation freely to our readers. This is one of the most elegant and readable translations that I have come across and we will be promoting it widely on our website".

The Knox Bible translation was described as "a masterful translation of the Bible" by Time Magazine and was the first vernacular version to be approved for liturgical use in the 20th century. It has featured on EWTN, received praise from Cardinal Cormac Murphy O’Connor, Archbishop Vincent Nichols, Dr. Rowan Williams and Dr. Scott Hahn among others. It has also received many positive reviews from Catholic Biblical scholars and writers.

I reviewed the new edition last year. More about Monsignor Ronald Knox here.

Published on February 16, 2013 23:00

Oh, to be in Oxford in March!

For this Tolkien conference:

For this Tolkien conference: J. R. R. Tolkien is one of the best known authors of the twentieth century, and his books The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings have entertained and intrigued readers alike for decades, becoming some of the most popular books of all time. Many people will have read these novels, or seen the filmed adaptations, but have had little opportunity to take their interests further. To meet this need the Oxford Tolkien Spring School is being organised by the University of Oxford's English Faculty (where Tolkien taught for most of his career), aimed at those who have read some of Tolkien's fiction and wish to discover more. A series of introductory lectures by world-leading Tolkien scholars have been assembled, to take place in the English Faculty, University of Oxford, over the 21-23 March, 2013. Talks will cover Tolkien's life, his work as an academic, his mythology, the influences of medieval literature on his fiction, his languages, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and his other lesser known works. There will also be panel discussions looking at Tolkien's place in the the literary canon. There will also be opportunities to see the sights of Oxford that were so important to Tolkien and his colleagues, as well as an introduction to some of the Tolkien collections at the University.

More info here and here!

I certainly look forward to our day in Oxford on our way from York to London on the Catholic Martyrs of England pilgrimage. We will focus more on Blessed John Henry Newman--and of course, the many Catholic Martyrs from Oxford (like St. Edmund Campion)--but Tolkien, Lewis, and the Inklings won't be far from my thoughts, at least.

The itinerary for that day in Oxford includes visiting the Anglican St. Mary's to see the martyr's shrine; Oriel and Trinity Colleges, and the Oxford Oratory. Lunch at the "Bird and the Baby" would fit in nicely, with shopping at St. Philip's Bookstore and Blackwells! The tour's spiritual director, Father Steve Mateja, will celebrate Mass at St. Aloysius, the Oxford Oratory. Should be a splendid day in Oxford!

Father Majeta and I will be on Teresa Tomeo's Catholic Connection radio show one morning this week, and I'll let you know!

Published on February 16, 2013 22:30

February 15, 2013

Two Former "Anglicans" on EWTN

A couple of shows on EWTN's

The Journey Home

, hosted by Marcus Grodi of the Coming Home Network have an English Reformation connection:

A couple of shows on EWTN's

The Journey Home

, hosted by Marcus Grodi of the Coming Home Network have an English Reformation connection:On Monday, February 18, Marcus Grodi welcomes Fr. John Saward, a former Anglican, to discuss his conversion.

On Monday, February 25, Msgr. Jeffrey Steenson [ ]the Ordinary of the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter, established for Anglicans who want to be Catholic. As a former Episcopal bishop, he discusses with Marcus what convinced him to become a Catholic.

Father John Saward is the Pastor at SS Gregory and Augustine Catholic Church in Oxford and posts this biography:

Fr John Saward was born in 1947, and first trained for the Anglican ministry, receiving Anglican orders in 1972. He was received into the Catholic Church in 1979.

After many years teaching theology in Catholic institutions, he was ordained priest in 2003 and made Priest in Charge of SS Gregory & Augustine in 2005.

Fr Saward is also a Fellow of Blackfriars, the house of studies of the Dominicans, which is a Permanent Private Hall of Oxford University.

He is the author of numerous works of theology, and the official English translator of Pope Benedict XVI's work, 'The Spirit of the Liturgy.'

Here is a link to his C.V. He is one of the editors of Firmly I Believe and Truly: The Spiritual Tradition of Catholic England 1483-1999, a lovely big book I dip into all the time. He is also the author of The Beauty of Holiness and the Holiness of Beauty; The Mysteries of March: Hans Urs Von Balthasar on the Incarnation and Easter, and Redeemer in the Womb, three books I have read and learned much from. Perhaps I'll re-read The Mysteries of March for Lent.

Here is a link to his C.V. He is one of the editors of Firmly I Believe and Truly: The Spiritual Tradition of Catholic England 1483-1999, a lovely big book I dip into all the time. He is also the author of The Beauty of Holiness and the Holiness of Beauty; The Mysteries of March: Hans Urs Von Balthasar on the Incarnation and Easter, and Redeemer in the Womb, three books I have read and learned much from. Perhaps I'll re-read The Mysteries of March for Lent.From the website of the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter comes this biography of Monsignor Jeffrey Steenson:

Pope Benedict XVI appointed Rev. Jeffrey N. Steenson as the first Ordinary of the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter on January 1, 2012.

Fr. Steenson teaches patristics (the study of the early church fathers) at the University of St. Thomas and St. Mary’s Seminary in Houston, TX.

He and his wife Debra were received into the Catholic Church in 2007, after 28 years of ministry in the Church of England and the Episcopal Church. Fr. Steenson was ordained for the Catholic priesthood in the Archdiocese of Santa Fe in 2009, and was instrumental in establishing the formation program for Anglican priests applying for the Catholic priesthood as part of the ordinariate.

Ordained an Anglican priest in 1980, he served Episcopal parishes in suburban Philadelphia, Pa. (from 1983), and Fort Worth, Texas (from 1989), before becoming canon to the ordinary in the Episcopal Diocese of the Rio Grande (New Mexico and far west Texas) (in 2000). In 2004, he was elected bishop of that diocese. Fr. Steenson was educated at Trinity College, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, Harvard Divinity School and the University of Oxford, where he received a doctor of philosophy degree in 1983.

Fr. Steenson has been keenly interested in the question of Catholic unity for many years, drawn to this path, as so many Anglicans and others have, through the writings of the church fathers. Patristic study is one of the glories of the Anglican theological tradition, and perhaps no text better illustrates this trajectory as well as these words from St. Irenaeus of Lyon in the later 2nd century: “It is necessary that all churches be in accord with this church [Rome] on account of her more excellent apostolic foundations” (Against Heresies 3.3.2).

These should be two fascinating episodes.

UPDATE: EWTN is pre-empting the Monday, February 18 episode for the PRAYER VIGIL AND ROSARY FOR DEACON WILLIAM STELTEMEIERFr. Miguel, Celebrant and Fr. Wade Menezes, Homilist. for the repose of the soul of the Founding President and long time Chairman of EWTN, Deacon William Steltemeier. The "repeat" schedule is:

Tue. Feb. 19 at 1:00 AM ET

Fri. Feb. 22 at 1:00 PM ET

Mon. Mar. 18 at 8:00 PM ET

Tue. Mar. 19 at 1:00 AM ET

Fri. Mar. 22 at 1:00 PM ET

and I believe EWTN will post the interview on their youtube channel.

May Deacon Bill rest in the Peace of Christ. I met him and his wife when I travelled to Irondale, Alabama for EWTN Live and EWTN Bookmark broadcasts.

Published on February 15, 2013 22:30

February 14, 2013

Bishop Challoner on Fasting

As I have mentioned before on this blog, Bishop Challoner was a very important figure for Catholics in the long eighteenth century. As a minority, they were at their lowest ebb since the Elizabethan settlement: the exiled Stuarts, planning invasions of Scotland, drew many of their nobles and other leaders to France; the Enlightenment Church of England did not care enough about upholding doctrine to urge persecution, and they were generally ignored and weak. Bishop Challoner wrote books of devotion and lives of the saints, including English saints and martyrs of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to inspire them.

As I have mentioned before on this blog, Bishop Challoner was a very important figure for Catholics in the long eighteenth century. As a minority, they were at their lowest ebb since the Elizabethan settlement: the exiled Stuarts, planning invasions of Scotland, drew many of their nobles and other leaders to France; the Enlightenment Church of England did not care enough about upholding doctrine to urge persecution, and they were generally ignored and weak. Bishop Challoner wrote books of devotion and lives of the saints, including English saints and martyrs of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to inspire them.This site features a great resource of meditations by Bishop Challoner, including this one for the Friday after Ash Wedneday, on Fasting:

Consider first, that fasting, according to the present discipline of the Church, implies three things. First, we are to abstain from flesh meat on fasting days; secondly, we are to eat but one meal in the day; and thirdly, we are not to take that meal till about noon. The ancient discipline of the Church was more rigorous, both in point of the abstinence, and in not allowing the meal in Lent till the evening. These regulations are calculated to mortify the sensual appetite by penance and self-denial. If you find some difficulty in the observance of them, offer it up to God for your sins. Fasting is not designed to please, but to punish. Your diligent compliance on this occasion with the laws of your mother the Church will also give an additional value to your mortifications, from the virtue of obedience.

Consider 2ndly, that we must not content ourselves with the outward observance of these regulations that relate to our diet on fasting days, but we must principally have regard to the inward spirit, and what we may call the very soul of the fast, which is a penitential spirit; without this the outward observance is but like a carcass without life. This penitential spirit implies a deep sense of the guilt of our sins; a horror and a hearty sorrow for them; a sincere desire to return to God, and to renounce our sinful ways for the future; and particularly a readiness of mind to make the best satisfaction we are capable of to divine justice by penancing ourselves for our sins. Fasting, performed in this spirit, cannot fail of moving God to mercy. O my soul, let thy fasting be always animated with this spirit

Consider 3rdly, that fervent prayer and alms-deeds also, according to each one’s ability, ought to be the inseparable companions of our fasting. These three sisters should go hand-in-hand, Tob. xii. 8, to help us in our warfare against our three mortal enemies, the flesh, the world, and the devil. The practice of these three eminent good works we must oppose to that triple concupiscence which reigns in the world, and by means of which Satan maintains his unhappy reign. By fasting we overcome the lusts of the flesh by alms-deeds we subdue the lusts of the eyes, by which we are apt to covet the mammon of the world, and its empty toys; and by fervent and humble prayer we conquer the pride of life, and put to flight the devil, the king of pride. O let us never forget to call in these powerful auxiliaries to help us in our warfare. Let alms-deeds and prayer ever accompany our fasts.

Conclude to follow these rules, if you desire your fast should be acceptable; if you fail in them, it will not be such a fast as God hath chosen.

Read more here.

Published on February 14, 2013 22:30

February 13, 2013

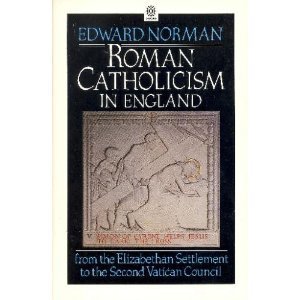

Book Review: Roman Catholicism in England

Edward Norman, who recently joined the Catholic Church through the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham, wrote this OPUS book in 1985:

Edward Norman, who recently joined the Catholic Church through the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham, wrote this OPUS book in 1985:Roman Catholicism in England[: from the Elizabethan Settlement to the Second Vatican Council] is the first study for several decades of the way in which the English Catholics have asserted their faith in the four centuries since the Reformation, of how they have sought to balance allegiance to Rome and the 'old faith' with loyalty to the English Constitution, even in times of severe persecution. It examines the ideas of leading figures in the Church, assessing their contribution to significant changes in Roman Catholicism up to the Second Vatican Council and pinpointing the shifts away from traditional antagonism.

This short survey, only 138 pages (including index) covers the recusant centuries of martyrdom and suffering, the long eighteenth century, emancipation and restoration in the nineteenth century, and Catholic involvement in twentieth century England, including Catholic opposition to the establishment of the Welfare State (primarily because of its effects on the family). Norman begins with a fascinating comment on the particular response of Catholics in England to being an oppressed and suppressed minority: he notes that "small religious communities and churches, existing at the margin of society" which have attracted "the hostility of their neighbors" and are "subject to active persecution" often develop a sectarian and radical outlook. Norman contends, however, that "The English Catholic 'recusants'--those who refused to conform to the laws of the unitary Protestant establishment--did not develop sectarian qualities, did not become political radicals (although a few sought revolution as a means of procuring a Catholic dynastic restoration), did not deviate from orthodoxy, and did not above all, quietly slide back into a comfortable acquiescence with the new order."

Norman concludes with this admiring comment: "Theirs is a noble history of enormous self-sacrifice for higher purposes, and of a rooted determination to preserve both their English virtue and their religious allegiance in a sensible and clear balance."

This is just the first page of the book! I found similar insights and brilliance throughout the contents of Roman Catholicism in England:

Preface

1. A rejected minority

2. The Elizabethan settlement

3. Catholics under the penal laws

4. The era of Emancipation and expansion

5. Leaders and thinkers

6. Twentieth-century developments

Suggested further reading

Index

Highly recommended.

Note: Norman dedicated the book to Saint Henry Walpole "Domus Sancti Petri Alumnus"!

Published on February 13, 2013 22:30

February 12, 2013

The Ashless Ash Wednesday of 1548

Eamon Duffy's The Stripping of the Altars is so indispensible! If I had to be on a desert island and couldn't follow up on G.K. Chesterton’s advice to have a book about building ships, I would want to have Duffy's book with me. It definitely changed our view of the English Reformation. Note that Alec Ryrie comes at the English Reformation from a distinctly Protestant view, but appreciates Duffy’s achievement so well:

As an interpretation of English Reformation history, there was nothing particularly revolutionary about The Stripping of the Altars. The argument, essentially, was that pre-Reformation English Catholicism was a vibrant, popular, unified and flourishing tradition; a tradition that was then wantonly, deliberately and violently destroyed by a small clique of Protestant extremists. Others had made similar arguments, and while this picture can be overstated, precious few scholars today reject it entirely.

Duffy's particular achievement, though, was to show us "traditional religion" (not "popular" religion, he insists: the elite shared it, too) at parish level. And Duffy, an Irish Catholic born in 1947, understands this tradition in his bones. He can explain how, for example, an illiterate people could fully understand a Latin liturgy even if they could not actually translate it. He rescues medieval Catholicism from both the caricatures of later Protestantism and the condescension of later Catholicism. . . .

But he has changed the discipline, for three reasons. First, the sheer mass of evidence his scholarship has accumulated. This is a fat book, which, as a review quoted on the cover insists, is "not a page too long". Second, it makes sense of so much else. Scholars with Protestant sympathies frequently agree with Duffy about much of what happened, if not with his tone of lament. His rehabilitation of Mary I - long remembered as "Bloody Mary" - has been particularly compelling.

Lastly, the passion with which he writes gives the reader not merely a shrewd historical argument but a compelling vision of what it meant actually to live this traditional religion. It is a vision that a secular historian could not have given us.

In the chapter on Edward VI, ("The Attack on Traditional Religion III: The Reign of Edward VI") he recounts the Ashless Ash Wednesday of 1548, which followed the Candle-less Candlemas of the Feast of the Purification. Palm Sunday was palm-less that year, of course, and no processions--no Creeping to the Cross on Good Friday. The entire edifice of Catholic culture and liturgy was being dismantled in England.

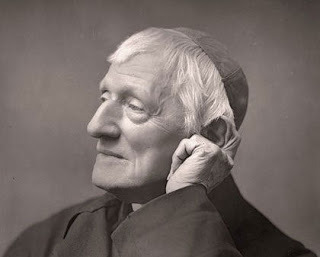

Blessed John Henry Newman moved his listeners to tears at the first Catholic synod held in the Diocese of Westminster on July 13, 1852 when he preached his sermon on the Second Spring:

Three centuries ago, and the Catholic Church, that great creation of God's power, stood in this land in pride of place. It had the honours of near a thousand years upon it; it was enthroned in some twenty sees up and down the broad country; it was based in the will of a faithful people; it energized through ten thousand instruments of power and influence; and it was ennobled by a host of Saints and Martyrs. The churches, one by one, recounted and rejoiced in the line of glorified intercessors, who were the respective objects of their grateful homage. Canterbury alone numbered perhaps some sixteen, from St. Augustine to St. Dunstan and St. Elphege, from St. Anselm and St. Thomas down to St. Edmund. York had its St. Paulinus, St. John, St. Wilfrid, and St. William; London, its St. Erconwald; Durham, its St. Cuthbert; Winton, its St. Swithun. Then there were St. Aidan of Lindisfarne, and St. Hugh of Lincoln, and St. Chad of Lichfield, and St. Thomas of Hereford, and St. Oswald and St. Wulstan of Worcester, and St. Osmund of Salisbury, and St. Birinus of Dorchester, and St. Richard of Chichester. And then, too its religious orders, its monastic establishments, its universities, its wide relations all over Europe, its high prerogatives in the temporal state, its wealth, its dependencies, its popular honours,--where was there in the whole of Christendom a more glorious hierarchy? Mixed up with the civil institutions, with king and nobles, with the people, found in every village an in every town,--it seemed destined to stand, so long as England stood, and to outlast, it might be, England's greatness.

But it was the high decree of heaven, that the majesty of that presence should be blotted out. It is a long story, my Fathers and Brothers--you know it well. I need not go through it. The vivifying principle of truth, the shadow of St. Peter, the grace of the Redeemer, left it. That old Church in its day became a corpse (a marvellous, an awful change!); and then it did but corrupt the air which once it refreshed, and cumber the ground which once it beautified. So all seemed to be lost; and there was a struggle for a time, and then its priests were cast out or martyred. There were sacrileges innumerable. Its temples were profaned or destroyed; its revenues seized by covetous nobles, or squandered upon the ministers of a new faith. The presence of Catholicism was at length simply removed,--its grace disowned,--its power despised,--its name, except as a matter of history, at length almost unknown. It took a long time to do this thoroughly; much time, much thought, much labour, much expense; but at last it was done. Oh, that miserable day, centuries before we were born! What a martyrdom to live in it and see the fair form of Truth, moral and material, hacked piecemeal, and every limb and organ carried off, and burned in the fire, or cast into the deep! But at last the work was done. Truth was disposed of, and shovelled away, and there was a calm, a silence, a sort of peace;--and such was about the state of things when we were born into this weary world.

As an interpretation of English Reformation history, there was nothing particularly revolutionary about The Stripping of the Altars. The argument, essentially, was that pre-Reformation English Catholicism was a vibrant, popular, unified and flourishing tradition; a tradition that was then wantonly, deliberately and violently destroyed by a small clique of Protestant extremists. Others had made similar arguments, and while this picture can be overstated, precious few scholars today reject it entirely.

Duffy's particular achievement, though, was to show us "traditional religion" (not "popular" religion, he insists: the elite shared it, too) at parish level. And Duffy, an Irish Catholic born in 1947, understands this tradition in his bones. He can explain how, for example, an illiterate people could fully understand a Latin liturgy even if they could not actually translate it. He rescues medieval Catholicism from both the caricatures of later Protestantism and the condescension of later Catholicism. . . .

But he has changed the discipline, for three reasons. First, the sheer mass of evidence his scholarship has accumulated. This is a fat book, which, as a review quoted on the cover insists, is "not a page too long". Second, it makes sense of so much else. Scholars with Protestant sympathies frequently agree with Duffy about much of what happened, if not with his tone of lament. His rehabilitation of Mary I - long remembered as "Bloody Mary" - has been particularly compelling.

Lastly, the passion with which he writes gives the reader not merely a shrewd historical argument but a compelling vision of what it meant actually to live this traditional religion. It is a vision that a secular historian could not have given us.

In the chapter on Edward VI, ("The Attack on Traditional Religion III: The Reign of Edward VI") he recounts the Ashless Ash Wednesday of 1548, which followed the Candle-less Candlemas of the Feast of the Purification. Palm Sunday was palm-less that year, of course, and no processions--no Creeping to the Cross on Good Friday. The entire edifice of Catholic culture and liturgy was being dismantled in England.

Blessed John Henry Newman moved his listeners to tears at the first Catholic synod held in the Diocese of Westminster on July 13, 1852 when he preached his sermon on the Second Spring:

Three centuries ago, and the Catholic Church, that great creation of God's power, stood in this land in pride of place. It had the honours of near a thousand years upon it; it was enthroned in some twenty sees up and down the broad country; it was based in the will of a faithful people; it energized through ten thousand instruments of power and influence; and it was ennobled by a host of Saints and Martyrs. The churches, one by one, recounted and rejoiced in the line of glorified intercessors, who were the respective objects of their grateful homage. Canterbury alone numbered perhaps some sixteen, from St. Augustine to St. Dunstan and St. Elphege, from St. Anselm and St. Thomas down to St. Edmund. York had its St. Paulinus, St. John, St. Wilfrid, and St. William; London, its St. Erconwald; Durham, its St. Cuthbert; Winton, its St. Swithun. Then there were St. Aidan of Lindisfarne, and St. Hugh of Lincoln, and St. Chad of Lichfield, and St. Thomas of Hereford, and St. Oswald and St. Wulstan of Worcester, and St. Osmund of Salisbury, and St. Birinus of Dorchester, and St. Richard of Chichester. And then, too its religious orders, its monastic establishments, its universities, its wide relations all over Europe, its high prerogatives in the temporal state, its wealth, its dependencies, its popular honours,--where was there in the whole of Christendom a more glorious hierarchy? Mixed up with the civil institutions, with king and nobles, with the people, found in every village an in every town,--it seemed destined to stand, so long as England stood, and to outlast, it might be, England's greatness.

But it was the high decree of heaven, that the majesty of that presence should be blotted out. It is a long story, my Fathers and Brothers--you know it well. I need not go through it. The vivifying principle of truth, the shadow of St. Peter, the grace of the Redeemer, left it. That old Church in its day became a corpse (a marvellous, an awful change!); and then it did but corrupt the air which once it refreshed, and cumber the ground which once it beautified. So all seemed to be lost; and there was a struggle for a time, and then its priests were cast out or martyred. There were sacrileges innumerable. Its temples were profaned or destroyed; its revenues seized by covetous nobles, or squandered upon the ministers of a new faith. The presence of Catholicism was at length simply removed,--its grace disowned,--its power despised,--its name, except as a matter of history, at length almost unknown. It took a long time to do this thoroughly; much time, much thought, much labour, much expense; but at last it was done. Oh, that miserable day, centuries before we were born! What a martyrdom to live in it and see the fair form of Truth, moral and material, hacked piecemeal, and every limb and organ carried off, and burned in the fire, or cast into the deep! But at last the work was done. Truth was disposed of, and shovelled away, and there was a calm, a silence, a sort of peace;--and such was about the state of things when we were born into this weary world.

Published on February 12, 2013 23:00

Blessed John Henry Newman on Lent

On Ash Wednesday in 2007, Edward T. Oakes, SJ, offered some quotations from Blessed John Henry Newman appropriate to the beginning of Lent (featured on

First Things

):

On Ash Wednesday in 2007, Edward T. Oakes, SJ, offered some quotations from Blessed John Henry Newman appropriate to the beginning of Lent (featured on

First Things

):No theologian working inside the traditions of western Christianity was more sensitive to the rhythms of the Church's liturgical year than was John Henry Newman. Which, of course, stands to reason, given the fact that, as an Anglican curate at St. Clement's in Oxford and later as vicar at St. Mary's in Littlemore, he gave sermons "in season and out" that were soon recognized as the most theologically rich ever delivered since patristic times, later published in eight volumes as Parochial and Plain Sermons. Yes, his appointment as a Fellow of Oriel College at Oxford gave clear testimony to his academic brilliance, a verdict of his peers that he vindicated with such scholarly publications as Lectures on Justification and The Arians of the Fourth Century. But his real work during that period from 1824 to 1843 was in pastoral care, including preaching nearly every Sunday with a tenacity and depth that caught the imagination of hearers and readers from his day to our own.

This being the onset of the season of Lent—when Christians think especially on the reality of sin in their lives—I thought I would offer a string of quotations from Newman appropriate to this season now begun, a catena, as it were, of "edifying discourses" from a master at homiletical brilliance.

What has always struck me about his Lenten sermons are two themes delicately balanced: On the one hand, Newman sets the bar of Christian holiness very high; yet, on the other, he shows an acute awareness of the weaknesses that beset Christians and so understands them when they fail (as we are all bound to do) to measure up to his extraordinarily demanding standards. As to the first theme, take this typical passage from his sermon "The Religion of the Day":

We dwell in the full light of the Gospel, and the full grace of the Sacraments. We ought then to have the holiness of the Apostles. There is no reason except our own willful corruption, that we are not by this time walking in the steps of St. Paul or St. John, and following them as they followed Christ. . . . Nothing is more difficult than to be disciplined and regular in our religion. It is very easy to be religious by fits and starts, and to keep up our feelings by artificial stimulants; but regularity seems to trammel us, and we become impatient.

Read the rest here.

Published on February 12, 2013 22:30

February 11, 2013

Five English Catholic Martyrs and the Ladywell Shrine in Lancashire

From the Catholic Encyclopedia comes this account of one of the five priests executed on February 12, 1584, Blessed George Haydock, and of course, his connection to the other four, accused with him of a conspiracy against Queen Elizabeth I:

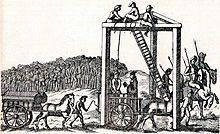

From the Catholic Encyclopedia comes this account of one of the five priests executed on February 12, 1584, Blessed George Haydock, and of course, his connection to the other four, accused with him of a conspiracy against Queen Elizabeth I:English martyr; born 1556; executed at Tyburn, 12 February, 1583-84. He was the youngest son of Evan Haydock of Cottam Hall, Lancashire, and Helen, daughter of William Westby of Mowbreck Hall, Lancashire; was educated at the English Colleges at Douai and Rome, and ordained priest (apparently at Reims), 21 December, 1581. Arrested in London soon after landing, he spent a year and three months in the strictest confinement in the Tower, suffering from the recrudescence of a severe malarial fever first contracted in the early summer of 1581 when visiting the seven churches of Rome. About May, 1583, though he remained in the Tower, his imprisonment was relaxed to "free custody", and he was able to administer the Sacraments to his fellow-prisoners. During the first period of his captivity he was accustomed to decorate his cell with the name and arms of the pope scratched or drawn in charcoal on the door or walls, and through his career his devotion to the papacy amounted to a passion. It therefore gave him particular pleasure that on the following feast of St. Peter's Chair at Rome (16 January) he and other priests imprisoned in the Tower were examined at the Guildhall by the recorder touching their beliefs, though he frankly confesses it was with reluctance that he was eventually obliged to declare that the queen was a heretic, and so seal his fate. On 5 February, 1583-4, he was indicted with James Fenn, a Somersetshire man, formerly fellow of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, the future martyr William Deane, who had been ordained priest the same day as himself, and six other priests, for having conspired against the queen at Reims, 23 September, 1581, agreeing to come to England, 1 October, and setting out for England, 1 November. In point of fact he arrived at Reims on 1 November, 1581. On the same 5 February two equally ridiculous indictments were brought, the one against Thomas Hemerford, a Dorsetshire man, sometime scholar of St. John's College, Oxford, the other against John Munden, a Dorsetshire man, sometime fellow of New College, Oxford, John Nutter, a Lancashire man, sometime scholar of St. John's College, Cambridge, and two other priests. The next day, St. Dorothy's Day, Haydock, Fenn, Hemerford, Munden, and Nutter were brought to the bar and pleaded not guilty.

Haydock had for a long time shown a great devotion to St. Dorothy, and was accustomed to commit himself and his actions to her daily protection. It may be that he first entered the college at Douai on that day in 1574-5, but this is uncertain. The "Concertatio Ecclesiae" says he was arrested on this day in 1581-2, but the Tower bills state that he was committed to the Tower on the 5th, in which case he was arrested on the 4th. On Friday the 7th all five were found guilty, and sentenced to death. The other four were committed in shackles to "the pit" in the Tower, but Haydock, probably lest he should elude the executioner by a natural death, was sent back to his old quarters. Early on Wednesday the 12th he said Mass, and later the five priests were drawn to Tyburn on hurdles; Haydock, being probably the youngest and certainly the weakest in health, was the first to suffer. An eyewitness has given us an account of their martyrdom, which Father Pollen, S.J., has printed in the fifth volume of the Catholic Record Society.

He describes Haydock as "a man of complexion fayre, of countenance milde, and in professing of his faith passing stoute". He had been reciting prayers all the way, and as he mounted the cart said aloud the last verse of "Te lucis ante terminum". He acknowledged Elizabeth as his rightful queen, but confessed that he had called her a heretic. He then recited secretly a Latin hymn, refused to pray in English with the people, but desired that all Catholics would pray for him and his country. Whereupon one bystander cried "Here be noe Catholicks", and another "We be all Catholicks"; Haydock explained "I meane Catholicks of the Catholick Roman Church, and I pray God that my bloud may encrease the Catholick faith in England". Then the cart was driven away, and though "the officer strock at the rope sundry times before he fell downe", Haydock was alive when he was disembowelled. So was Hemerford, who suffered second. The unknown eyewitness says, "when the tormentor did cutt off his members, he did cry, 'Oh! A!'; I heard myself standing under the gibbet". As for Fenn, "before the cart was driven away, he was stripped of all his apparell saving his shirt only, and presently after the cart was driven away his shirt was pulled of his back, so that he hung stark naked, whereat the people muttered greatly". He also was cut down alive, though one of the sheriffs was for mercy. Nutter and Munden were the last to suffer. They made speeches and prayers similar to those uttered by their predecessors. Unlike them they were allowed to hang longer, if not till they were dead, at any rate until they were quite unconscious. Haydock was twenty-eight, Munden about forty, Fenn, a widower, with two children, was probably also about forty, Hemerford was probably about Haydock's age; Nutter's age is quite unknown.

The Haydock family of Lancashire was one of the great recusant families of that northwestern county that resisted the established Church of England. Later this month, on February 21, I'll post about Thomas Haycock, publisher. On April 11, I'll tell you about his brother, Father George Leo Haydock.

The Ladywell Shrine, The Shrine of Our Lady and the Martyrs, is in Lancashire.

Published on February 11, 2013 22:30