Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 280

March 8, 2013

Happy Birthday, William Cobbett!

In honor of William Cobbett's birthday on March 9, 1763, let us pretend we are gathered in The William Cobbett public house in Farnham, raising a pint in his honor!

Happy Birthday to the author of Rural Rides and A History of the Protestant Reformation in England and Ireland!

G.K. Chesterton wrote of the latter:

“He seemed to be calling black white, when he declared that what was white had been blackened, or that what seemed to be white had only been whitewashed.” Cobbett called Elizabeth I, "Bloody Bess" and Mary I, "Good Queen Mary"--and people reading his work knew that Elizabeth I had been Bloody, "if pursuing people with execution and persecution and torture makes a person bloody" and that Mary I had been good, "if certain real virtues and responsibilities make a person good" -- as Chesterton notes, "It was not really Cobbett's history that was in controversy; it was his controversialism. It was not his facts that were challenged, it was his challenge."

Photo credit: wikipedia commons.

Happy Birthday to the author of Rural Rides and A History of the Protestant Reformation in England and Ireland!

G.K. Chesterton wrote of the latter:

“He seemed to be calling black white, when he declared that what was white had been blackened, or that what seemed to be white had only been whitewashed.” Cobbett called Elizabeth I, "Bloody Bess" and Mary I, "Good Queen Mary"--and people reading his work knew that Elizabeth I had been Bloody, "if pursuing people with execution and persecution and torture makes a person bloody" and that Mary I had been good, "if certain real virtues and responsibilities make a person good" -- as Chesterton notes, "It was not really Cobbett's history that was in controversy; it was his controversialism. It was not his facts that were challenged, it was his challenge."

Photo credit: wikipedia commons.

Published on March 08, 2013 22:30

March 7, 2013

St.Thomas of Canterbury, Martyr (et al)

From the English Historical Fiction Writers blog: Author Rosanne E. Lortz helps us with "Understanding the Archbishop: Thomas Becket and the Case of the Criminous Clerks":

From the English Historical Fiction Writers blog: Author Rosanne E. Lortz helps us with "Understanding the Archbishop: Thomas Becket and the Case of the Criminous Clerks": Thomas Becket is known far and wide as the archbishop who wrangled with England’s Henry II and ended up being slain in the church at Canterbury. Although most consider Becket’s murder a deplorable event, historical opinion is divided over whether Becket was in the right in the first place. Did he really have any justification for standing in Henry’s way? Was he not simply quibbling over minutiae and defending an indefensible position?<

The place that I will pick up in the story is just after Henry finagled matters so that Becket could become the Archbishop of Canterbury. Previously, Becket had been Henry’s royal chancellor and had proved his usefulness and loyalty to the king time and again. But within the month of his election as archbishop, he resigned his position as royal chancellor. It was a move he did not have to make. In the king’s mind, Becket could have retained both positions without any conflict of interest. Becket thought otherwise. This resignation of the chancellorship was the first manifestation that he was not the king’s man any longer.

Those inside of Becket’s household began to see a change in their master. John of Salisbury wrote that, “Upon his consecration he immediately put off the old man, and put on the hairshirt and the monk, crucifying the flesh with its passions and desires.” No longer was his house a scene of Epicurean delights. The gold was gone from the tables. The fare was frugal and spare. Becket also took seriously his liturgical duties. He performed the office of the sacraments with all the reverence that was required but that had never been expected of him. He withdrew as often as he could into prayer and study in order that he might be better equipped for his office of teacher and pastor.

Right away the pulpit of Canterbury resounded with a new voice, a voice powerful and persuasive, the like of which had not been heard since the days of Archbishop Anselm. The chronicler Roger of Pontigny gives us a taste of Becket’s preaching:

It happened at that time in certain crowded gathering that Thomas delivered a sermon to the clergy and people in the presence of the king. His sermon concerned the kingdom of Christ the Lord, which is the Church, and the worldly kingdom, and the powers of each realm, priestly and royal, and also the two swords, the spiritual and the material. And as on this occasion he discussed much about ecclesiastical and secular power in a wonderful way—for he was very eloquent—the king took note of each of his words, and recognizing that he rated ecclesiastical dignity far above any secular title, he did not receive his sermon with a placid spirit. For he sensed from his words how distant the archbishop was from his own position.

Becket had changed, and not—in Henry’s mind—for the better.

Reading about St. Thomas a Becket--and indeed watching the Richard Burton-Peter O'Toole movie, I've often thought that St. Thomas a Becket's change is the perfect demonstration of the power of the Sacrament of Holy Orders. He'd been ordained, after all, and was now a priest and bishop. Becket was transformed.

During the English Catholic Martyrs Pilgrimage, we'll spend a day in Canterbury. Although St. Thomas of Canterbury is the first martyr you think of when you think of Canterbury, there are several Catholic Martyrs from the Reformation era. St. John Stone is one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales, and I would call him a Supremacy martyr. He refused to swear Henry VIII's Oath of Supremacy and suffered martyrdom for the same cause at St. Thomas a Becket: the unity of the Catholic Church and the primacy of Jesus's Vicar on earth, the Pope. St. Thomas More has a Canterbury connection, as his head--the one removed at Henry's command--is in the Roper family chapel of St. Dunstan's Anglican Church. Finally, there are the Oaten Hill Martyrs (Recusant Martyrs) who suffered during the reign of Elizabeth I in the aftermath of the Spanish Armada: Blessed Edward Campion, Blessed Christopher Buxton, Blessed Robert Wilcox, and Blessed Robert Widmerpool. From this site, we know that:

~Robert Wilcox was the first to suffer. He told his companions to be of good heart. He was going to heaven before them, where he would would carry the tidings of their coming after him.

~Edward Campion was next to die. We do not know what he said before his death, but it is on record that he refused a chance to escape from the Marshalsea, saying: I would gladly escape if I did not hope to suffer martyrdom.

~Robert Widmerpool was probably the next to die. He kissed the ladder and the rope, and with the rope round his neck gave God hearty thanks for bringing him to so great a glory as that of dying for his faith in the same place where St Thomas of Canterbury had died for his.

~Finally, Christopher Buxton was led to the scaffold. He was the youngest and was offered his life if he conformed to the new Church. Father Buxton replied: I would not purchase a corruptible life at such a rate, and, if I had one hundred lives, I would willingly lay them all down in defence of my faith.

While we are in Canterbury this September, Father Steven Mateja will offer Mass at St. Thomas of Canterbury Catholic Church.

Published on March 07, 2013 22:30

March 6, 2013

My First Review on CatholicFiction.net: Robert Peckham

I heard about CatholicFiction.net and the sites' need for reviewers from two sources: the Son Rise Morning Show and the Catholic Writers Guide. I've identified four "classic" works to review and here is the first one: Maurice Baring's historical novel, Robert Peckham:

I heard about CatholicFiction.net and the sites' need for reviewers from two sources: the Son Rise Morning Show and the Catholic Writers Guide. I've identified four "classic" works to review and here is the first one: Maurice Baring's historical novel, Robert Peckham:I was rash when I should have been timid, and timid when I should have been bold. . . .I should never have left England. I should have remained and resisted, or died in the attempt.—Robert Peckham, summing up his life in Maurice Baring’s novel, Robert Peckham

Maurice Baring was a contemporary and friend of G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, but his literary contributions as novelist, poet, and essayist are less remembered today. This historical novel, Robert Peckham, is a fascinating first person narration of a life during the Tudor dynasty in England. Robert Peckham, the narrator and protagonist, lives in the shadow of his father in service and loyalty to Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I, witnessing all the religious changes of the sixteenth century and the English Reformation. Peckham sees the execution of martyrs, the dissolution of monasteries, and the destruction of Catholicism—all the while enduring an unhappy marriage and family life.

Other novelists have depicted this era, often including historical characters: Robert Hugh Benson’s trio of Tudor novels (The King’s Achievement, By What Authority?, and Come Rack! Come Rope!) are tales of adventure, as English men and women confront the crucial issues of loyalty and conscience; choosing between their Catholic faith and the established Church of England; suffering torture and execution and proving their courage and endurance. Even those who choose to conform to the state church and renounce their Catholicism suffer loss and endure trouble.

Read the rest at CatholicFiction.net and I'll let you know when my next review is online!

Published on March 06, 2013 22:30

March 5, 2013

The Prebendaries' Plot of 1543 and Tyburn in 1544

Blessed Germain or Jermyn or German Gardiner was executed at Tyburn on March 7, 1544. He was beatified in 1886 by Pope Leo XIII. As Bishop of Winchester Stephen Gardiner's nephew and secretary, he became involved in the Prebendaries' Plot of 1543 and was hung, drawn, and quartered for the denial of Henry VIII's Supremacy over the Church of England.

The Prebendaries' Plot was named after the five prebendary canons of Canterbury Cathedral (including William Hadleigh, a monk at Christchurch Canterbury prior to the monastery's dissolution) who formed its core. Others involved were two holders of the new cathedral office of "six preacher" (created in 1541), along with various local non-cathedral priests and Kentish gentlemen (eg Thomas Moyle, Edward Thwaites and Cyriac Pettit). Simultaneous agitation at the court in Windsor, and the conspiracy in general, was led covertly by Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester.

Henry VIII's chaplain Richard Cox was charged with investigating and suppressing it, and his success (240 priests and 60 laypeople of both sexes were accused of involvement) led to his being made Cranmer's chancellor (and later, under Elizabeth, bishop of Ely). Gardiner survived, though his relation Germain Gardiner, who had acted as his secretary and intermediary to the plotters in Kent, was executed in 1544 for questioning the Royal Supremacy.

So Blessed Germain Gardiner was left as the scapegoat to suffer for the plot, while Henry VIII, still valuing Bishop Stephen Gardiner's efforts in supporting both Henry's "Great Matter" and his more "conservative" reformation of the Church, spared his uncle.

Along with Gardiner, Blessed John Larke, friend of St. Thomas More and former rector of Chelsea (More's parish) and Blessed John Ireland, also connected with St. Thomas More and Chelsea, were executed for denying Henry VIII's Supremacy. Robert Singleton, a parish priest, was also executed under a charge of treason, but he has not been beatified.

John Heywood, the playwright and grandfather of John Donne was also on the scaffold at Tyburn sentenced to death, but he recanted and was spared. He also had connections to St. Thomas More and survived the ups and downs of the Tudor succession until Elizabeth I's reign. Then he went into exile in Mechelen, Belgium where he died around 1580. You may have used one of John Heywood epigrams and not realized the source: wikipedia lists many of the most famous:

What you have, hold.

Haste maketh waste. (1546)

Out of sight out of mind. (1542)

When the sun shineth, make hay. (1546)

Look ere ye leap. (1546)

Two heads are better than one. (1546)

Love me, love my dog. (1546)

Beggars should be no choosers. (1546)

All is well that ends well. (1546)

The fat is in the fire. (1546)

I know on which side my bread is buttered. (1546)

One good turn asketh another. (1546)

A penny for your thought. (1546)

Rome was not built in one day. (1546)

Better late than never. (1546)

An ill wind that bloweth no man to good. (1546)

The more the merrier. (1546)

You cannot see the wood for the trees. (1546)

This hitteth the nail on the head. (1546)

No man ought to look a given horse in the mouth. (1546)

Tread a woorme on the tayle and it must turne agayne. (1546)

Many hands make light work. (1546)

Wolde ye bothe eate your cake and haue your cake? (1562)

When he should get aught, each finger is a thumb. (1546)

The Prebendaries' Plot was named after the five prebendary canons of Canterbury Cathedral (including William Hadleigh, a monk at Christchurch Canterbury prior to the monastery's dissolution) who formed its core. Others involved were two holders of the new cathedral office of "six preacher" (created in 1541), along with various local non-cathedral priests and Kentish gentlemen (eg Thomas Moyle, Edward Thwaites and Cyriac Pettit). Simultaneous agitation at the court in Windsor, and the conspiracy in general, was led covertly by Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester.

Henry VIII's chaplain Richard Cox was charged with investigating and suppressing it, and his success (240 priests and 60 laypeople of both sexes were accused of involvement) led to his being made Cranmer's chancellor (and later, under Elizabeth, bishop of Ely). Gardiner survived, though his relation Germain Gardiner, who had acted as his secretary and intermediary to the plotters in Kent, was executed in 1544 for questioning the Royal Supremacy.

So Blessed Germain Gardiner was left as the scapegoat to suffer for the plot, while Henry VIII, still valuing Bishop Stephen Gardiner's efforts in supporting both Henry's "Great Matter" and his more "conservative" reformation of the Church, spared his uncle.

Along with Gardiner, Blessed John Larke, friend of St. Thomas More and former rector of Chelsea (More's parish) and Blessed John Ireland, also connected with St. Thomas More and Chelsea, were executed for denying Henry VIII's Supremacy. Robert Singleton, a parish priest, was also executed under a charge of treason, but he has not been beatified.

John Heywood, the playwright and grandfather of John Donne was also on the scaffold at Tyburn sentenced to death, but he recanted and was spared. He also had connections to St. Thomas More and survived the ups and downs of the Tudor succession until Elizabeth I's reign. Then he went into exile in Mechelen, Belgium where he died around 1580. You may have used one of John Heywood epigrams and not realized the source: wikipedia lists many of the most famous:

What you have, hold.

Haste maketh waste. (1546)

Out of sight out of mind. (1542)

When the sun shineth, make hay. (1546)

Look ere ye leap. (1546)

Two heads are better than one. (1546)

Love me, love my dog. (1546)

Beggars should be no choosers. (1546)

All is well that ends well. (1546)

The fat is in the fire. (1546)

I know on which side my bread is buttered. (1546)

One good turn asketh another. (1546)

A penny for your thought. (1546)

Rome was not built in one day. (1546)

Better late than never. (1546)

An ill wind that bloweth no man to good. (1546)

The more the merrier. (1546)

You cannot see the wood for the trees. (1546)

This hitteth the nail on the head. (1546)

No man ought to look a given horse in the mouth. (1546)

Tread a woorme on the tayle and it must turne agayne. (1546)

Many hands make light work. (1546)

Wolde ye bothe eate your cake and haue your cake? (1562)

When he should get aught, each finger is a thumb. (1546)

Published on March 05, 2013 22:30

March 4, 2013

Devotion to the Five Wounds of Christ

During my hour of Adoration before the Blessed Sacrament at Blessed Sacrament Church this Sunday, I prayed from A Prayer Book of Catholic Devotions: Praying the Seasons and Feasts of the Church Year, compiled by William G. Storey, DMS, Professor Emeritus of Liturgy and Church History at the University of Notre Dame and published by Loyola Press.

Among the devotions he includes for Lent is to the Five Wounds of Jesus, beginning with this hymn attributed to Thomas a Kempis and translated by John Mason Neale:

O love, how deep, how broad, how high,

How passing thought and fantasy,

That God, the Son of God should take

Our mortal form for mortals' sake.

For us to evil power betrayed,

Scourged, mocked, in purple robe arrayed,

He bore the shameful cross and death,

For us gave up his dying breath.

For us he rose from death again;

For us he went on high to reign;

For us he sent the Spirit here

To guide, to strengthen, and to cheer.

All glory to our Lord and God

For love so deep, so high, so broad:

The Trinity whom we adore

Forever and forevermore.

Then follows a little office of devotion to the Five Wounds. Dr. Storey also includes another devotion attributed to St. Clare of Assisi with prayers to each of the Five Wounds: one in each hand, one in each foot, and one in Our Savior's side.

As you might recall, devotion to the Five Wounds of Jesus was very popular in England before the Reformation and became a symbol of opposition to the Henrician and Elizabethan religious changes. Both the Pilgrimage of Grace and the North Rebellion used the banner of the Five Wounds.

More on this devotion here, from the aptly named Fish Eaters.

Among the devotions he includes for Lent is to the Five Wounds of Jesus, beginning with this hymn attributed to Thomas a Kempis and translated by John Mason Neale:

O love, how deep, how broad, how high,

How passing thought and fantasy,

That God, the Son of God should take

Our mortal form for mortals' sake.

For us to evil power betrayed,

Scourged, mocked, in purple robe arrayed,

He bore the shameful cross and death,

For us gave up his dying breath.

For us he rose from death again;

For us he went on high to reign;

For us he sent the Spirit here

To guide, to strengthen, and to cheer.

All glory to our Lord and God

For love so deep, so high, so broad:

The Trinity whom we adore

Forever and forevermore.

Then follows a little office of devotion to the Five Wounds. Dr. Storey also includes another devotion attributed to St. Clare of Assisi with prayers to each of the Five Wounds: one in each hand, one in each foot, and one in Our Savior's side.

As you might recall, devotion to the Five Wounds of Jesus was very popular in England before the Reformation and became a symbol of opposition to the Henrician and Elizabethan religious changes. Both the Pilgrimage of Grace and the North Rebellion used the banner of the Five Wounds.

More on this devotion here, from the aptly named Fish Eaters.

Published on March 04, 2013 22:30

March 3, 2013

St. Augustine of Canterbury a Traitor in 1590?

Blessed Christopher Bales, priest and martyr, and companions (laymen who assisted him) Blessed Alexander Blake, and Blessed Nicholas Horner, were all executed on March 4, 1590 at three different sites in London. According to the

Catholic Encyclopedia

, his career as a missionary priest in England was brief: Priest and martyr, b. at Coniscliffe near Darlington, County Durham, England, about 1564; executed 4 March, 1590. He entered the English College at Rome, 1 October, 1583, but owing to ill-health was sent to the College at Reims, where he was ordained 28 March, 1587. Sent to England 2 November, 1588, he was soon arrested, racked, and tortured by Topcliffe, and hung up by the hands for twenty-four hours at a time; he bore all most patiently. At length he was tried and condemned for high treason, on the charge of having been ordained beyond seas and coming to England to exercise his office. He asked Judge Anderson whether St. Augustine, Apostle of the English, was also a traitor. The judge said no, but that the act had since been made treason by law. He suffered 4 March, 1590, "about Easter", in Fleet Street opposite Fetter Lane. On the gibbet was set a placard: "For treason and favouring foreign invasion". He spoke to the people from the ladder, showing them that his only "treason" was his priesthood. On the same day Venerable Nicholas Horner suffered in Smithfield for having made Bales a jerkin, and Venerable Alexander Blake in Gray's Inn Lane for lodging him in his house. They were beatified on December 15 in 1929 by Pope Pius XI. Philip Caraman, SJ, includes Blessed Christopher Bales' question to Judge Anderson in his collection of primary sources, The Other Face: Catholic Life Under Elizabeth I: He was asked by the judge according to custom . . . when judgment was about to be pronounced, if he had anything to say for himself. He answered, "This only to I want to know, whether St. Augustine sent hither by St. Gregory was a traitor or not." They answered that he was not . . . He answered them, "Why then do you condemn me to death as a traitor? I am sent hither by the same see: and for the same purpose as he was. Nothing is charged against me that could not also be charged against the saint." But for all that they condemned him. (Greene, Collections); page 230.

The Catholic Encyclopedia also has an entry on Blessed Nicholas Horner and his sufferings and consolations:

Layman and martyr, born at Grantley, Yorkshire, England, date of birth unknown; died at Smithfield, 4 March, 1590. He appears to have been following the calling of a tailor in London, when he was arrested on the charge of harbouring Catholic priests. He was confined for a long time in a damp and noisome cell, where he contracted blood poisoning in one leg, which it became necessary to amputate. It is said that during this operation Horner was favoured with a vision, which acted as an anodyne to his sufferings. He was afterwards liberated, but when he was again found to be harbouring priests he was convicted of felony, and as he refused to conform to the public worship of the Church by law established, was condemned. On the eve of his execution, he had a vision of a crown of glory hanging over his head, which filled him with courage to face the ordeal of the next day. The story of this vision was told by him to a friend, who in turn transmitted it by letter to Father Robert Southwell S.J., 18 March, 1590. Horner was hanged, drawn and quartered because he had relieved and assisted Christopher Bales . . .

The Catholic Encyclopedia also has an entry on Blessed Nicholas Horner and his sufferings and consolations:

Layman and martyr, born at Grantley, Yorkshire, England, date of birth unknown; died at Smithfield, 4 March, 1590. He appears to have been following the calling of a tailor in London, when he was arrested on the charge of harbouring Catholic priests. He was confined for a long time in a damp and noisome cell, where he contracted blood poisoning in one leg, which it became necessary to amputate. It is said that during this operation Horner was favoured with a vision, which acted as an anodyne to his sufferings. He was afterwards liberated, but when he was again found to be harbouring priests he was convicted of felony, and as he refused to conform to the public worship of the Church by law established, was condemned. On the eve of his execution, he had a vision of a crown of glory hanging over his head, which filled him with courage to face the ordeal of the next day. The story of this vision was told by him to a friend, who in turn transmitted it by letter to Father Robert Southwell S.J., 18 March, 1590. Horner was hanged, drawn and quartered because he had relieved and assisted Christopher Bales . . .

Published on March 03, 2013 22:30

March 2, 2013

Sede Vacante and "Marking the Hours"

Browsing ahead in the March issue of the

Magnificat

prayer magazine, I noticed a meditation by "Pope Benedict XVI" with the brief biographical note: "His Holiness Benedict XVI was elected to the See of Saint Peter in 2005", to which now we would need to add, "and renounced the papacy in 2013, becoming Pope Emeritus on the evening of February 28 that year."

Such editing reminded me of Eamon Duffy's Marking of the Hours: English People and Their Prayers, 1240-1570, published by Yale University Press in 2007 and reissued in paperback in 2011. During the Tudor era, the English people had many causes not only to mark the hours of prayer but to mark their prayer books:

Such editing reminded me of Eamon Duffy's Marking of the Hours: English People and Their Prayers, 1240-1570, published by Yale University Press in 2007 and reissued in paperback in 2011. During the Tudor era, the English people had many causes not only to mark the hours of prayer but to mark their prayer books:

In this richly illustrated book, religious historian Eamon Duffy discusses the Book of Hours, unquestionably the most intimate and most widely used book of the later Middle Ages. He examines surviving copies of the personal prayer books which were used for private, domestic devotions, and in which people commonly left traces of their lives. Manuscript prayers, biographical jottings, affectionate messages, autographs, and pious paste-ins often crowd the margins, flyleaves, and blank spaces of such books. From these sometimes clumsy jottings, viewed by generations of librarians and art historians as blemishes at best, vandalism at worst, Duffy teases out precious clues to the private thoughts and public contexts of their owners, and insights into the times in which they lived and prayed. His analysis has a special relevance for the history of women, since women feature very prominently among the identifiable owners and users of the medieval Book of Hours.

Books of Hours range from lavish illuminated manuscripts worth a king’s ransom to mass-produced and sparsely illustrated volumes costing a few shillings or pence. Some include customized prayers and pictures requested by the purchaser, and others, handed down from one family member to another, bear the often poignant traces of a family’s history over several generations. Duffy places these volumes in the context of religious and social change, above all the Reformation, discusses their significance to Catholics and Protestants, and describes the controversy they inspired under successive Tudor regimes. He looks closely at several special volumes, including the cherished Book of Hours that Sir Thomas More kept with him in the Tower of London as he awaited execution.

When my husband and I, with a great priest friend, visited the British Library, we saw examples of these prayer books, including that of Lady Jane Grey and other materials--like St. Thomas More's last letter to Henry VIII--in a display on the Tower of London.

It will be indeed strange today at Mass when there is no mention of a Pope in the Canon. I can vaguely remember the sede vacante period between Blessed Pope John Paul II's death and the election of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger as Benedict XVI, but I will have to listen closely today.

It will be indeed strange today at Mass when there is no mention of a Pope in the Canon. I can vaguely remember the sede vacante period between Blessed Pope John Paul II's death and the election of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger as Benedict XVI, but I will have to listen closely today.

EWTN posts this prayer for the election of a Pope:

Lord God, You are our Eternal Shepherd and Guide. In Your mercy grant Your Church a shepherd who will walk in Your ways and whose watchful care will bring us Your blessing. We ask this through our Lord Jesus Christ, Your Son, who lives and reigns with You and the Holy Spirit, One God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Such editing reminded me of Eamon Duffy's Marking of the Hours: English People and Their Prayers, 1240-1570, published by Yale University Press in 2007 and reissued in paperback in 2011. During the Tudor era, the English people had many causes not only to mark the hours of prayer but to mark their prayer books:

Such editing reminded me of Eamon Duffy's Marking of the Hours: English People and Their Prayers, 1240-1570, published by Yale University Press in 2007 and reissued in paperback in 2011. During the Tudor era, the English people had many causes not only to mark the hours of prayer but to mark their prayer books:In this richly illustrated book, religious historian Eamon Duffy discusses the Book of Hours, unquestionably the most intimate and most widely used book of the later Middle Ages. He examines surviving copies of the personal prayer books which were used for private, domestic devotions, and in which people commonly left traces of their lives. Manuscript prayers, biographical jottings, affectionate messages, autographs, and pious paste-ins often crowd the margins, flyleaves, and blank spaces of such books. From these sometimes clumsy jottings, viewed by generations of librarians and art historians as blemishes at best, vandalism at worst, Duffy teases out precious clues to the private thoughts and public contexts of their owners, and insights into the times in which they lived and prayed. His analysis has a special relevance for the history of women, since women feature very prominently among the identifiable owners and users of the medieval Book of Hours.

Books of Hours range from lavish illuminated manuscripts worth a king’s ransom to mass-produced and sparsely illustrated volumes costing a few shillings or pence. Some include customized prayers and pictures requested by the purchaser, and others, handed down from one family member to another, bear the often poignant traces of a family’s history over several generations. Duffy places these volumes in the context of religious and social change, above all the Reformation, discusses their significance to Catholics and Protestants, and describes the controversy they inspired under successive Tudor regimes. He looks closely at several special volumes, including the cherished Book of Hours that Sir Thomas More kept with him in the Tower of London as he awaited execution.

When my husband and I, with a great priest friend, visited the British Library, we saw examples of these prayer books, including that of Lady Jane Grey and other materials--like St. Thomas More's last letter to Henry VIII--in a display on the Tower of London.

It will be indeed strange today at Mass when there is no mention of a Pope in the Canon. I can vaguely remember the sede vacante period between Blessed Pope John Paul II's death and the election of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger as Benedict XVI, but I will have to listen closely today.

It will be indeed strange today at Mass when there is no mention of a Pope in the Canon. I can vaguely remember the sede vacante period between Blessed Pope John Paul II's death and the election of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger as Benedict XVI, but I will have to listen closely today. EWTN posts this prayer for the election of a Pope:

Lord God, You are our Eternal Shepherd and Guide. In Your mercy grant Your Church a shepherd who will walk in Your ways and whose watchful care will bring us Your blessing. We ask this through our Lord Jesus Christ, Your Son, who lives and reigns with You and the Holy Spirit, One God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Published on March 02, 2013 22:30

March 1, 2013

Believers and Patriots in OSV's The Catholic Answer Magazine

My husband kindly called me at work yesterday to tell me that the March/April 2013 issue contained a feature article written by me! "Believers and Patriots: What is colonial Maryland's legacy of religious freedom?" by Stephanie A. Mann. (Page 30 of

The Catholic Answer Magazine

; subscription required for on-line access.) It is a very well illustrated article. I wrote it during the Fortnight for Religious Freedom last summer and start off with the installation Mass homily of Archbishop William Lori in Baltimore, Maryland:

My husband kindly called me at work yesterday to tell me that the March/April 2013 issue contained a feature article written by me! "Believers and Patriots: What is colonial Maryland's legacy of religious freedom?" by Stephanie A. Mann. (Page 30 of

The Catholic Answer Magazine

; subscription required for on-line access.) It is a very well illustrated article. I wrote it during the Fortnight for Religious Freedom last summer and start off with the installation Mass homily of Archbishop William Lori in Baltimore, Maryland:On May 16, 2012, Bishop William Lori, the chairman of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishop’s Ad Hoc Committee for Religious Liberty, was installed as the Archbishop of Baltimore.

In his homily at his installation Mass, he stressed the need to defend religious liberty, harkening to the foundation of the oldest diocese in the United States of America and its first bishop: “We defend religious liberty . . . because Archbishop John Carroll’s generation of believers and patriots bequeathed to us a precious legacy that has enabled the Church to worship in freedom, to bear witness to Christ publicly, and to do massive and amazing works of pastoral love, education and charity in ways that are true to the faith that inspired them in the first place.”

Archbishop John Carroll’s “generation of believers and patriots” were heirs to the great Maryland experiment in religious liberty in the middle of the 17th century — an experiment that did not last then and has not received the attention it deserves since.

George Calvert founded the Maryland colony as a commercial venture and to demonstrate that it was possible for a person to be a Catholic and loyal to the monarch, a combination long thought impossible in England. He and his heirs struggled to establish the Maryland colony and to maintain religious liberty in its laws and culture. They were swimming against the tide of European religious settlements: subjects were expected to go with the flow of their sovereign’s religion.

Next Saturday, March 9, the Kansas Authors Club District 5 monthly meeting is a read-around by members, and I plan to read from this article. I will also have my book for sale, and distribute information about the Catholic Martyrs of England pilgrimage. The meeting is held at the Wichita Public Library Rockwell Branch, 5939 E. 9th Street, Wichita, KS, 2:00- 4:00 pm--meetings are free and open to the public, so if you're in Wichita, please feel welcome to attend. Refreshments are served!

Published on March 01, 2013 22:30

February 27, 2013

Van Cliburn and Memory

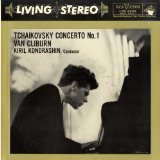

Van Cliburn is dead. He won the great International Tchaikovsky Competition the year I was born, and I do remember that my parents had a copy of his RCA Victor album playing Tchaikovsky's Concerto No. 1--"Living Stereo" on their cabinet record player. This album was mixed in with soundtracks--Ben Hur, The Sound of Music, South Pacific, Camelot, etc.; jazz--Stan Kenton, Dave Brubeck; various pop instrumentalists and bands--Percy Faith, Mantovani, Herb Albert, Ferrante and Teicher, and others. There were some other classicial albums, like collections of Strauss waltzes, and lots of Christmas albums with big classical orchestras and conductors, Eugene Ormandy and Leonard Bernstein.

Van Cliburn is dead. He won the great International Tchaikovsky Competition the year I was born, and I do remember that my parents had a copy of his RCA Victor album playing Tchaikovsky's Concerto No. 1--"Living Stereo" on their cabinet record player. This album was mixed in with soundtracks--Ben Hur, The Sound of Music, South Pacific, Camelot, etc.; jazz--Stan Kenton, Dave Brubeck; various pop instrumentalists and bands--Percy Faith, Mantovani, Herb Albert, Ferrante and Teicher, and others. There were some other classicial albums, like collections of Strauss waltzes, and lots of Christmas albums with big classical orchestras and conductors, Eugene Ormandy and Leonard Bernstein.That our household had a copy of this Van Cliburn album is not surprising. This was the first classical album to go platinum. Cliburn was one of the first American classical artists to have a real popular following. His obits commonly cite Time magazine’s 1958 cover story, which 'quoted a friend as saying Cliburn could become “the first man in history to be a Horowitz, Liberace and Presley all rolled into one.”' A ticker-tape parade for a pianist!

As the AP obit begins:

FORT WORTH, Texas — For a time in Cold War America, Van Cliburn had all the trappings of a rock star: sold-out concerts, adoring, out-of-control fans and a name recognized worldwide. He even got a ticker-tape parade in New York City.

And he did it all with only a piano and some Tchaikovsky concertos.

The celebrated pianist played for every American president since Harry Truman, plus royalty and heads of state around the world. But he is best remembered for winning a 1958 piano competition in Moscow that helped thaw the icy rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Cliburn, who died Wednesday at 78 after fighting bone cancer, was “a great humanitarian and a brilliant musician whose light will continue to shine through his extraordinary legacy,” said his publicist and longtime friend Mary Lou Falcone. “He will be missed by all who knew and admired him, and by countless people he never met.”

The young man from the small east Texas town of Kilgore was a baby-faced 23-year-old when he won the first International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow just six months after the Soviets’ launch of Sputnik embarrassed the U.S. and inaugurated the space race.

The interesting thing about his career is that, although he went from triumph to triumph for a time, he also took time away from touring to take care of his mother. The world of classical music and performance has always fascinated me, as it combines showmanship and tremendous knowledge. Anyone who dedicates his life to studying the great repertoire of Western classical music, understanding the people and the culture that created it -- that's a special person. May he rest in peace.

Published on February 27, 2013 22:30

February 26, 2013

Execution of Anne Line and Companions, February 27, 1601

I will be on the Son Rise Morning Show this morning (7:45 a.m. EST/6:45 a.m. CST) to discuss today's martyrs and the scene at Tyburn on Feburary 27, 1601, when St. Anne Line was hung and then Blessed Mark Barkworth, OSB and Blessed Roger Filcock were hung, drawn, and quartered. You can listen live here online if you don't have an EWTN radio station in your area.

Anne Heigham Line was a convert to Catholicism; she and her brother William Heigham were disinherited and disowned by their Calvinist father. In 1586 she married Roger Line, another disinherited convert. Not long after Anne and Roger married, he and William were arrested for attending Mass and were exiled from England. Roger lived in Flanders and died in 1594.

Father John Gerard SJ, author of the famous book Autobiography of an Elizabethan Priest, asked Anne to manage two different safe houses for Jesuits, even though she was ill, but because she was destitute, surviving on teaching and sewing. She was arrested on the Feast of the Presentation, February 2, 1601, when Father Francis Page was celebrating Mass; he escaped with her help. She was tried on February 26, carried to court in a chair, where she admitted joyfully that she had helped Father Page escape and only regretted that she had not been able to help even more priests escape!

She was hung at Tyburn in London on February 27 and repeated her statement from court before her execution: "I am sentenced to die for harboring a Catholic priest, and so far I am from repenting for having so done, that I wish, with all my soul, that where I have entertained one, I could have entertained a thousand." Two priests, Father Roger Filcock and Father Mark Barkworth, paid tribute to her before their own executions, drawn, hung, and quartered. Father Filcock kissed her dead hand and the hem of her dress as she still hung from the gibbet and proclaimed, “You have gotten the start of us, sister, but we will follow you as quickly as we may.”

Blessed Mark Barkworth OSB was born about 1572 at Searby in Lincolnshire. He studied for a time at Oxford, though no record remains of his stay there. He was received into the Catholic Church at Douai in 1593, by Father George, a Flemish Jesuit and entered the College there with a view to the priesthood. He matriculated at Douai University on 5 October 1594.

On account of an outbreak of the plague, in 1596 Barkworth was sent to Rome and thence to Valladolid in Spain, where he entered the English College on 28 December 1596. On his way to Spain he is said to have had a vision of St Benedict, who told him he would die a martyr, in the Benedictine habit. While at Valladolid he make firmer contact with to the Benedictine Order. The "Catholic Encyclopedia" notes that there are accounts that his interest in the Benedictines resulted in suffering at the hands of the College superiors, but the Encyclopedia expresses scepticism, suggesting anti-Jesuit bias.

Barkworth was ordained priest at the English College some time before July 1599, when he set out for the English Mission together with Father Thomas Garnet. On his way he stayed at the Benedictine Monastery of Hyrache in Navarre, where his wish to join the order was granted by his being made an Oblate with the privilege of making profession at the hour of death.

After having escaped from the hands of the Huguenots of La Rochelle, he was arrested on reaching England and thrown into Newgate, where he was imprisoned for six months, and was then transferred to Bridewell. There he wrote an appeal to Robert Cecil, signed "George Barkworth". At his examinations he was reported to behave with fearlessness and frank gaiety. Having been condemned with a formal jury verdict, he was thrown into "Limbo", the horrible underground dungeon at Newgate, where he is said to have remained "very cheerful" till his death.

Barkworth was executed at Tyburn with Jesuit Roger Filcock and Anne Line, on 27 February 1601. He sang, on the way to Tyburn, the Paschal Anthem: "Hæc dies quam, fecit Dominus exultemus et lætemur in ea", and Father Filcock joined him in the chant:

Hæc dies quam fecit Dominus; [This is the day which the Lord has made:]

exsultemus, et lætemur in ea. [let us be glad and rejoice in it.]

At Tyburn he told the people: "I am come here to die, being a Catholic, a priest, and a religious man, belonging to the Order of St Benedict; it was by this same order that England was converted."

He was said to be "a man of stature tall and well proportioned showing strength, the hair of his head brown, his beard yellow, somewhat heavy eyed". He was of a cheerful disposition. He suffered in the Benedictine habit, under which he wore a hair-shirt. It was noticed that his knees were, like St. James', hardened by constant kneeling, and an apprentice in the crowd picking up his legs, after the quartering, called out: "Which of you Gospellers can show such a knee?" Contrary to usual practice, the quarters of the priests were not exposed but buried near the scaffold. They were later retrieved by Catholics. Barkworth was beatified by Pope Pius XI on 15 December 1929.

Blessed Roger Filcock (1570-1601) was arrested in England while he was fulfilling a probationary period prior to entering the Jesuits. He had studied at the English College in Rheims, France and then in Valladolid, Spain, but when he asked to join the Society he was encouraged to apply again after ministering for awhile in England.

His journey into England was difficult enough. The ship he was traveling on from Bilbao, Spain to Calais, France, was becalmed just outside the port and fell pray to a Dutch ship blockading the harbor. Filcock was captured, but managed to escape and land surreptitiously on the shore in Kent in 1598. Soon after he began his ministry, he contacted Father Henry Garnet, the Jesuit superior, asking to become a Jesuit. He was accepted into the Society in 1600, but then was betrayed by someone he had studied with in Spain. He was arrested and committed to Newgate Prison in London. His trial did not last long, despite the fact that there was no evidence against him and that the names in the indictment were not names he had used. Together with Father Mark Barkworth, a Benedictine, he was tied to a hurdle and dragged through the streets to Tyburn. Barkworth was first to be hung, disembowelled and quartered. Filcock had to watch his companion suffer, knowing that he would immediately follow. Pope John Paul II beatified him, on the 22nd of November 1987.

St. Anne Line was among the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales canonized by Pope Paul VI in 1970. She, St. Margaret Clitherow and St. Margaret Ward share a separate Feast on August 30 (the date of St. Margaret Ward's martyrdom in 1588) in the dioceses of England.

The Catholic Martyrs of England Pilgrimage will visit Tyburn and the Tyburn Convent the day before we return to the USA.

Published on February 26, 2013 22:30