Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 281

February 25, 2013

A Poem from Hilaire Belloc

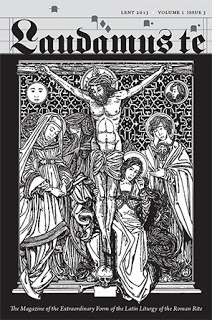

The Lent issue of the

Laudamus Te

Magazine of the Extraordinary Form of the Latin Liturgy of the Roman Rite, features this poem by Hilaire Belloc:

The Lent issue of the

Laudamus Te

Magazine of the Extraordinary Form of the Latin Liturgy of the Roman Rite, features this poem by Hilaire Belloc:Our Lord and Our Lady

They warned Our Lady for the Child

That was Our Blessed Lord,

And She took Him into the desert wild,

Over the camel's ford.

And a long song She sang to Him

And a short story told:

And she wrapped Him in a woollen cloak

To keep Him from the cold.

But when Our Lord was grown a man

The rich they dragged Him down,

And they crucified Him in Golgotha,

Out and beyond the town.

They crucified Him on Calvary,

Upon an April day;

And because He had been Her little Son

She followed Him all the way.

Our Lady stood beside the Cross,

A little space apart,

And when She heard Our Lord cry out

A sword went through her heart.

They laid Our Lord in a marble tomb,

Dead, in a winding sheet.

But Our Lady stands above the world

With the white moon at her feet.

Laudamus Te needs some help to stay in production and sent out a notice about subscriptions and delays: if you appreciate the beauty and reverence of the Extraordinary Form of the Latin Liturgy of the Roman Rite, you might consider a subscription. The publishers are bravely doing something beautiful in support of the traditional Latin Mass, answering Pope Benedict XVI's call for its renewal:

For this reason we will be taking a break in production. You will receive a Holy Week/Easter Week issue and then not another issue until this summer. We must catch up with propers editing or Laudamus Te magazine will fail. Your subscription will stay intact and resume when we resume. You will still receive the same number of issues that you subscribed to receive. We are very sorry to have to take this measure, but feel we have no choice until we get a little ahead. We hope you will stick with us as we work to catch up!

We are struggling to attract subscriptions as well. So far we have about 750 subscribers, but we need several thousand. With every penny going toward production, printing, and mailing costs, we have no budget for advertising. A very kind individual stepped in temporarily to purchase ads for Laudamus Te, but we cannot rely upon this kind of generosity alone.

So, we are launching a subscription campaign. If everyone now receiving Laudamus Te were to attract just two new subscribers, our production costs per copy would drop dramatically and the extra money would provide a much-needed funding cushion. We love this magazine as much as you do and are committed to its success. Will you help? Please tell your friends about the magazine and let us know if you would be willing to pass out flyers at your parish. Many of you have paid for gift subscriptions and made donations, and we very much appreciate your help. Please also keep us in your prayers.

Published on February 25, 2013 22:30

February 24, 2013

Why Use Latin When the Liturgy is in English?

I have this on order from amazon.com:

I have this on order from amazon.com:Where late the sweet birds sang: Latin Music from Tudor England by Magnificat directed by Philip Cave frrom Linn Records

Per the "liner" notes, Magnificat is exploring a little mystery--why was church music written to Latin texts when the official liturgical language was English? Of course, Latin was still an important diplomatic and scholarly language in the sixteenth century, but music for the Church of England's Book of Common Prayer should have been set for English texts.

The early Elizabethan years present a fascinating period of stylistic transition in vocal music to sacred Latin texts, as well as posing some intriguing questions about context. For whom was this Latin music written, given that one of the first pieces of legislation in the new Queen's reign was the Act of Uniformity, which specified that church services should be held in English rather than in Latin, in all but a few places? And what was the practical impact of the new religious laws on composers such as Thomas Tallis, Robert Parsons, Robert White and William Byrd?

While Byrd's lifelong commitment to the Catholic faith is well documented, little is known for certain about the religious convictions of the other composers. The debate continues on whether they favoured Latin texts because they were writing for institutions where some of these texts were still permitted, because they retained loyalty to the Catholic faith, alternatively that they had in mind domestic or devotional music-making, or simply because they had an enduring affection for the old ways. Whatever its intended destination, the music's structure shows a move away from the ritual plainchant cantus firmus-based hymns and responds of Mary's chapel towards freely composed imitative polyphony in which text and music are much more closely connected. It seems to have taken noticeably longer for composers of English-texted sacred music to move on from the artistic constraints of Edwardian Protestantism to produce works of comparable musical interest (though there are, of course, a few notable exceptions to this generalisation, such as Tallis's miniature masterpiece "If ye love me").

We are lucky to have this music and to have Magnificat record it:

Much of the music presented here is known to us not through sources compiled for use in church - hardly any have survived - but because it was included in one or other of the largely retrospective manuscript collections now in the library of Christ Church, Oxford, assembled by Robert Dow (Mss.984-88, c.1581 - 88) and John Baldwin (Mss.979-83, c.1575 - 81). Although dating individual works with certainty is rarely possible, most of the music chosen for this recording is thought to come from the 1560s and 70s. . . .

Considering and compiling this recording is something that has occupied my thoughts over several years. Both in content and performing style it represents the fruits of a personal journey that started at a time when most of this music was not at all widely known. None of us dared to dream then that it could ever be shared with the thousands of people who have now come to value it. Time moves on, and witnessing that positive progress gives cause for some satisfaction.

Overall, the mini-trend of performing groups like the Tallis Scholars, Stille Antico, Magnificat, The Tudor Consort, The Byrd Ensemble, and others, reflecting on the religious conflict during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is fascinating to me.

You might notice the Shakespearean reference in the CD title:

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.

In me thou see'st the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west;

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death's second self, that seals up all in rest.

In me thou see'st the glowing of such fire,

That on the ashes of his youth doth lie,

As the death-bed, whereon it must expire,

Consumed with that which it was nourish'd by.

This thou perceiv'st, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well, which thou must leave ere long.

Eamon Duffy parsed that line, "Bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang" to identify William Shakespeare with a sort of nostaglia for the monasteries and lost Catholic culture, in his book Saints, Sacrilege, and Sedition last year. This reviewer Professor David J. Davis, thinks it too much a throwaway:

Finally, the chapter, almost whimsically, speculates about the bard himself, seeking to include him in this expanding cabal of conservative voices. Despite Duffy's disclaimer that he is not arguing ‘that Shakespeare was a Catholic’, he does interpret Sonnet 73 as one that ‘decisively aligns Shakespeare against the Reformation’ (pp. 253, 250). Assuming this is true, that a single sonnet captures Shakespeare’s views of the Reformation, which is a grand and hasty assumption, Duffy does not propose what this means for the Stratford dramatist’s religious creed. Duffy’s argument is little more than a playful suggestion, based upon a single line in a single poem, but it is, in the end, more a scholarly flight-of-fancy than the kind of historical nuance we have come to expect from Duffy’s analysis. Moreover, it is a somewhat limp method of wrapping up the entire book, leaving readers with something much more akin to a sigh than a bang.

Published on February 24, 2013 22:30

February 23, 2013

How to Prepare for a Pilgrimage

Vanessa Denha-Garmo asked a very good question at the end of her interview of Father Steve Matejas and me on Catholic Connection last week: How should people prepare for going on the Catholic Martyrs of England Pilgrimage? Here are some hints:

Vanessa Denha-Garmo asked a very good question at the end of her interview of Father Steve Matejas and me on Catholic Connection last week: How should people prepare for going on the Catholic Martyrs of England Pilgrimage? Here are some hints:1) All travel involves planning and preparation. When my husband's career provided him with many opportunities to travel and I could go with him, I would plan and prepare my own itinerary for our destination. I would usually research three or four categories of things to see and visit: churches, bookstores, and colleges or universities, plus the usual monuments or museums as applicable. At first, back in the twentieth century, that often involved buying guidebooks or writing to tourism offices for brochures. Now, of course, the internet provides those resources. Corporate Travel Services, Father Steve, and I have taken care of some that planning--CTS books the flights, makes the hotel reservations, arranges the tours; Father and I have given our input to the itinerary.

Pilgrims might want to do their own planning about what they want to do in the evenings when the tour events are over--what sights to see or other places to visit; where to eat in York or London when dinner is not part of the schedule, for example. And there is a half-day in London "on your own" before we conclude the pilgrimage with a visit to St. Etheldreda's for Mass and the Tyburn Convent for a visit to the Martyrs' Shrine and Relics.

2) Pilgrimage travel involves not only practical but spiritual preparation. The Canterbury pilgrims, pictured above, went on pilgrimage for a spiritual purpose: expiation of sin; as penance after confession; for healing; for some other special intention. Pilgrims to England in September this year might prepare a special intention on the tour. The overall intentions of the pilgrimage, as Father Steve and I articulated them, is for us all to increase our devotion to these English martyrs and to meditate on their sacrifices for Jesus and His Church--the implications and impact on each of us today. Before a pilgrimage, we should go to Confession, receive Holy Communion, and pray, pray, pray for the grace to complete the tour with devotion, compassion for each other, and the success of all the travel arrangements, connections, and reservations.

3) A participant on a tour like this might indeed benefit from some supplemental reading and viewing. A copy of my book, Supremacy and Survival: How Catholics Endured the English Reformation, is part of the package from Corporate Travel Services. Father Steve mentioned two other good books to read: Edmund Campion by Evelyn Waugh and The Autobiography of a Hunted Priest by Father John Gerard, SJ. I'd also recommend Saint Robert Southwell and Henry Garnet: A Study in Friendship by Philip Caraman, SJ and Into the Lion's Den: The Jesuit Mission in Elizabethan England and Wales, 1580-1603 by Robert E. Scully, SJ, published by The Institute of Jesuit Sources (St. Louis, Missouri), c. 2011. They could read about St. Thomas More in various biographies, including this one I reviewed last year. With some reservations about Robert Bolt's view of conscience, they could watch A Man for All Seasons, or watch some of the Mary's Dowry productions on the Catholic Martyrs of the English Reformation. They could watch Playing Elizabeth's Tune for some musical background on the era and the conflicts caused by the State imposition of religious orthodoxy. There are more reading ideas for the Stuart era and even more for Blessed John Henry Newman (Oxford) and St. Thomas a Becket (Canterbury), but the works listed above are more accessible.

Published on February 23, 2013 22:30

February 22, 2013

Review Essay on Spying in Elizabeth I's Reign

Paul Dean, Head of English at Summer Fields School, Oxford, reviews two books for The New Criterion about the spy network operating in England during the reign of Elizabeth I. One is a new biography of Sir Francis Walsingham, which must be the third biography in the past five to ten years, The Queen's Agent by John Cooper; the other is a book I've mentioned before: The Watchers by Stephen Alford. A couple of excerpts:

A “loyal Catholic” was a contradiction in terms. Since the queen had been excommunicated by Pope Pius V’s bull Regnans in excelsis in 1570—which, incidentally, prompts the surprising reflection that England remained technically a Catholic country for the first twelve years of her reign—her Catholic subjects had been released from obedience to her or her laws. (John Cooper, however, remarks that the bull was not widely publicized in England and suggests that “most English Catholics never saw a copy.”) Many priests and laity worked actively to overthrow and replace her, first by Mary Queen of Scots, then, after the latter’s execution for treason in 1587—an act which was forced upon a reluctant Elizabeth by her ministers, who had effectively rigged the case against her royal cousin—by King Philip of Spain. Alford’s book tells the stories of many plotters on both sides: some, like John Somerville, minor figures, others among the great of the land. Intriguing though these stories are, they give the work an episodic feel; it lacks the narrative drive of Cooper’s biography of Walsingham (which Alford seems not to know). Where they cover the same ground, Cooper is usually clearer and more perceptive.

and

Cooper sensibly warns us of the danger of reading history written by the victors: “The myth that Catholicism is somehow alien to Englishness has had a long and corrosive effect on the national memory of the British Isles.” The first generation of Catholic missionary priests did not seek Elizabeth’s overthrow—indeed, Pope Pius IV offered to leave the Church of England undisturbed if only Catholics were granted freedom to worship. Cardinal Allen’s seminary at Douai, founded in 1568, initially encouraged its graduates to go to England to give pastoral support to Catholic families, not to make converts. (Allen himself, however, advocated the invasion of England by the powers of France and Spain.) Several priests prayed for the queen on the scaffold. Walsingham was uneasy about so many executions—not from humane motives, but because he felt that to create martyrs was to play into the enemy’s hands. It became increasingly difficult, and finally impossible, for many Catholics to take the oath of loyalty which was imposed on every citizen, requiring them “to withstand, pursue, and suppress” anyone designing to hurt the queen. Meanwhile, parliamentary legislation of the 1570s and 1580s, steered through by Walsingham, greatly extended the legal definition of treason.

Commenting on Cooper's explanation of Walsingham's involvement in the downfall of Mary, Queen of Scots, Dean notes:

Walsingham alone, the spider in the center of the web, saw the whole picture. Propelled by his extreme Protestant zeal, he was not above bypassing the law in order to gain his ends. He even recruited a Catholic priest, Gilbert Gifford, by whose means he was able to intercept correspondence between Mary, Queen of Scots and her contacts in Paris, and thereby unmask the Babington plot. (Among the plotters, by the way, was Chidiock Tichborne, whose poem written on the eve of his execution, “My prime of youth is but a frost of cares,” is a small masterpiece.) Gifford was trained by Thomas Phelippes, Walsingham’s chief cipher specialist, about whom Alford writes interestingly. Phelippes and Walsingham went so far as to add a coded postscript to one of Mary’s letters to Babington, using wording which would support a charge of treason against her. Also working on this case was Robert Poley, who was implicated in the death of Marlowe and was probably acting on government orders. (Alford’s downplaying of the evidence for Marlowe’s espionage activity as “sketchy and circumstantial” is questionable.) Babington realized too late that Poley might not be reliable, and wrote him a heartrending note: “I am the same I always pretended. I pray God you be so.” Babington’s inevitable execution in 1586 was made exceptionally brutal; on the personal orders of Elizabeth, “for more terror,” he was rent limb from limb. Mary, being royal, was beheaded, although Elizabeth would have preferred her quietly murdered in private, and even tried to persuade her jailer to do the deed himself.

Read the rest here. Remember, though, that the public reaction to Babington's horrible execution led Elizabeth to withdraw that order: the other conspirators were hung until dead, then cut up and their body parts displayed as the usual warning to plotters.

Published on February 22, 2013 22:30

February 21, 2013

A Different Suggestion for Lenten Reading Material

From the current issue of

Touchstone Magazine

:

From the current issue of

Touchstone Magazine

:Gilbert Meilaender on Reading Dorothy Sayers's Play Cycle for Lent

On June 4, 1955, C. S. Lewis wrote to Dorothy Sayers to thank her for a pamphlet and letter she had sent him. He noted, in passing, that "as always in Holy Week," he had been "re-reading [Sayers's] The Man Born to Be King. It stands up to this v. particular kind of test extremely well." We might, I think, do far worse than imitate Lewis in our own Lenten reading.

The Man Born to Be King is a series of radio plays, twelve in all, dramatizing the life of Jesus from birth to death and resurrection. First broadcast by the BBC in 1941–1942, they were published in 1943, together with Sayers's notes for each play and a long Introduction she wrote recounting both her aims and approaches in writing the plays and some of the first (often comical) reactions from the public. . . .

That is where the artist's skill and imaginative powers are essential, and, to my mind at least, Sayers is at the top of her form in these plays. Those who know her other writings will recall how insistently she argued that her task was to produce—as best she could—good work, plays that were truly good art. The theology implicit in the story and the religious impact of the events recounted would, she hoped, emerge from the story told, but her task was simply to tell that story in as coherent and arresting a fashion as possible. She had to develop the story through characters who, unlike us, do not know how it will end, and who could not, therefore, think in ways that might seem natural to us.

The plays may, therefore, call for some imaginative stretching on our part, but that stretching may also offer in turn a considerable theological payoff. In particular, it may keep Christians from a mistake they have often made—supposing that the political and religious leaders responsible for Jesus' death had as their aim "doing away with God." That is not how Sayers tells the story. "We, the audience, know what they were doing; the whole point and poignancy of the tragedy is lost unless we realise that they did not."

I have read Sayers' radio plays a few times, too, but usually for her depiction of the Nativity. Something that really thrilled me at the end of the online article was this link to an audio version of this play cycle--and it's free! I haven't listened to it yet, but it might answer my plea from a couple of years ago.

Published on February 21, 2013 22:30

The Ordinariate and the Chair

Today is the titular feast of the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter in the United States and Canada:

Note on the Solemnity of the Chair of St. Peter

In his statement on February 11, 2013, our Ordinary, Msgr. Steenson, reminded us that “members of the Ordinariate are in a particular way the spiritual children of His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI,” and Msgr. Steenson exhorts us, despite some feelings of sadness and a sense of shock, to deeper joy and special gratitude to the Holy Father “for giving us this beautiful gift of communion.”

On Friday, February 22, the Ordinariate of the Chair of St Peter will celebrate its Solemnity of Title, and the Ordinary commends all Ordinariate communities in North America to express their gratitude to Pope Benedict with the singing of a Solemn Te Deum of Thanksgiving (at the conclusion of Mass or Evensong, or as a separate service). After the Te Deum and its versicles, this special rite of thanksgiving may conclude with the following prayer:

Let us pray.

O God, whose mercies are without number, and the treasure of whose goodness is infinite: we render thanks unto thy most gracious majesty for the gifts which thou hast bestowed upon us (and especially for the pontificate of our Holy Father Benedict XVI, and for the gift of communion with the Chair of Peter); evermore beseeching thy mercy that, as thou dost grant the prayers of them that call upon thee, so thou wouldst not forsake them, but rather dispose their way towards the attainment of thy heavenly reward. Through Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee in the unity of the Holy Ghost, one God world without end. Amen.

The Ordinary and the Ordinariate community is aware that the Te Deum is not usually heard during Lent. However, February 22 is the Ordinariate’s Titular Solemnity and should be kept as such according to the Particular Calendar approved by the Holy See. The Te Deum is rightly proclaimed; Friday abstinence may be dispensed; the liturgical color is white; and the Gloria and Creed are said or sung at Mass (the Alleluia is omitted, as throughout the season).

With thankful joy, let us then pray and work that Pope Benedict’s “labors in the vineyard might continue to bring forth a fruitful harvest.”

Amen!

Note on the Solemnity of the Chair of St. Peter

In his statement on February 11, 2013, our Ordinary, Msgr. Steenson, reminded us that “members of the Ordinariate are in a particular way the spiritual children of His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI,” and Msgr. Steenson exhorts us, despite some feelings of sadness and a sense of shock, to deeper joy and special gratitude to the Holy Father “for giving us this beautiful gift of communion.”

On Friday, February 22, the Ordinariate of the Chair of St Peter will celebrate its Solemnity of Title, and the Ordinary commends all Ordinariate communities in North America to express their gratitude to Pope Benedict with the singing of a Solemn Te Deum of Thanksgiving (at the conclusion of Mass or Evensong, or as a separate service). After the Te Deum and its versicles, this special rite of thanksgiving may conclude with the following prayer:

Let us pray.

O God, whose mercies are without number, and the treasure of whose goodness is infinite: we render thanks unto thy most gracious majesty for the gifts which thou hast bestowed upon us (and especially for the pontificate of our Holy Father Benedict XVI, and for the gift of communion with the Chair of Peter); evermore beseeching thy mercy that, as thou dost grant the prayers of them that call upon thee, so thou wouldst not forsake them, but rather dispose their way towards the attainment of thy heavenly reward. Through Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee in the unity of the Holy Ghost, one God world without end. Amen.

The Ordinary and the Ordinariate community is aware that the Te Deum is not usually heard during Lent. However, February 22 is the Ordinariate’s Titular Solemnity and should be kept as such according to the Particular Calendar approved by the Holy See. The Te Deum is rightly proclaimed; Friday abstinence may be dispensed; the liturgical color is white; and the Gloria and Creed are said or sung at Mass (the Alleluia is omitted, as throughout the season).

With thankful joy, let us then pray and work that Pope Benedict’s “labors in the vineyard might continue to bring forth a fruitful harvest.”

Amen!

Published on February 21, 2013 22:30

February 20, 2013

Thomas Haydock, 18th Century English Catholic Publisher

According to wikipedia:

Thomas Haydock (1772–1859), born of one of the oldest English Catholic Recusant families, was a schoolmaster and publisher. His dedication to making religious books available to fellow Catholics suffering under the English Penal Laws came at great personal cost. He is best remembered for publishing an edition of the Douay Bible with extended commentary, compiled chiefly by his brother George Leo Haydock. Originally published in 1811 and still in print, it is one of the most enduring contributions to Catholic biblical studies. . . .

Haydock was born February 21, 1772 in Cottam, in the Fylde section of Lancashire in northern England. This is an area that was slow to accept the new Protestant religion. Speaking of Lancashire, Lord Burghley, advisor to Queen Elizabeth I complained, "The Papists every where are growen so confident, that they contempne Magistrats and their authoritie." In later centuries Lancashire would retain a small but determined Catholic population supported by families of the landed gentry, sometimes hosting secret Masses in their homes. The Haydocks were among the most prominent of these families and became legendary in their service to the Catholic Recusant movement. During the Elizabethan persecution, Father George Haydock (1556–1584), a "seminary priest", suffered martyrdom. He was beatified in 1987, earning the title “Blessed.” Early in the 18th century, Father Cuthbert Haydock (1684–1763) said secret Masses in a chapel hidden in the attic of Lane End House, Mawdesley, the home of his sister and brother-in-law.

Thomas Haydock was part of a unique generation whose combined contributions to this family tradition would be extraordinary. His father was a namesake of Blessed George Haydock. His two brothers both became priests. Older brother James (1765–1809) died caring for the sick of his congregation during a typhus epidemic. Younger brother George Leo (1774–1849), in addition to his work on the Bible, spent his career pastoring poor rural missions. A sister, Margaret (1767? - 1854), joined the Augustinian nuns, taking the name Sister Stanislaus.

He wanted to become a priest too:

After receiving his elementary education at a school established for Catholic students at Mowbreck Hall, Thomas was sent in 1785 to the English College, Douai, France, where he joined his brother, George. This institution was established for Catholic exiles in the 16th century to provide secondary education and preparation for the priesthood. His studies were interrupted in 1793, when the French revolutionary government declared war with England, closed the English College, and imprisoned some of its pro-England students. Both Haydock brothers managed to elude the authorities and escape back to England.

Continuing his pursuit of ordination, Thomas next went to the English College, Lisbon. His superiors there did not feel he had a priestly vocation and sent him home in 1795. Undeterred, he went to the new seminary established at Crook Hall, Durham with his brother George in 1796. Again, his vocation was questioned. Described as “easy going” (see also the “Tragic Personal Life” section below), he seems to have been judged by his superiors as constitutionally unsuited for the risks and hardships of the Catholic priesthood in Penal Period England. The eloquence and dedication Thomas expresses in his letters certainly support his sincerity; and his three attempts at the priesthood show his tenacity. However, against the wishes of his older and recently ordained brother James, he was finally persuaded to leave the seminary. Family friend and former Douay professor Benedict Rayment (1764–1842), who would later serve as editor of some of Haydock’s published works, remarked that of the three Haydock brothers seeking the priesthood, ‘’Thomas would have been the best’’.

Instead, he became a publisher of Catholic books, most notably his own brother George's commentary on the Douai-Rheims English translation of the Holy Bible. Although it was a very popular and important work, he struggled as a publisher:

Thomas Haydock had an enthusiasm for publishing, but was seriously lacking in business skills. He had a trustful nature that associates freely exploited, depriving him of profit and forcing him continually to operate on a shoestring. Although his Bible sold well, he lost money to his managers, clerks, and canvassers and was forced heavily into debt to an unscrupulous lender. Former Douay classmate Father (later Bishop) Robert Gradwell (1777–1860) wrote in August 1817 that Haydock was living in Dublin, “low in the world.” In 1818 he was arrested for debt and served four months in prison.

The experience did not discourage him from continuing his publishing business. By 1822 he was able to issue the first volume of a new edition of the Bible, a more modest undertaking this time, in a smaller octavo format and without the extended commentary of the folio edition. He had to take on several partners to complete the Bible’s second volume in 1824. This edition had many misprints, including the notable substitution of fornications for fortifications in II Corinthians 10:4. He had no known involvement with an American folio edition of the Haydock Bible published in Philadelphia in 1825.

Circa 1818 Haydock married Mary Lynch or Lynde of Dublin. Unfortunately, tragedy would dog his family life, just as it did his business. Mary died in 1823. Their three children all died young. The name of only one is known: George (1822–1840). Curiously, some books dated 1827 have the imprint, Thomas Haydock & Son. The apparent inconsistency between the publication date and the likely ages of any sons that could have been living at the time is a mystery.

Haydock struggled on with publishing at least until 1831, when he was able to reissue the New Testament portion of his original folio Bible. No dated works after that year are known, although he published undated works that may have appeared later. In 1832 he made an unsuccessful attempt to begin a journal called The Catholic Penny Magazine. At some point, he opened a school in Dublin where he resumed teaching until 1840. He left Dublin probably about that year and moved first to Liverpool, then to Preston. He could only watch as other publishers enjoyed success with new editions of his Bible: two British editions, one in 1845-48, another ca. 1853, and an American edition in 1852-4. He died at Preston in 1859, aged 87, with an estate valued at “less than 100 Pounds Sterling.” He was buried in the Haydock family grave at Newhouse Chapel, Newsham.

Thomas Haydock (1772–1859), born of one of the oldest English Catholic Recusant families, was a schoolmaster and publisher. His dedication to making religious books available to fellow Catholics suffering under the English Penal Laws came at great personal cost. He is best remembered for publishing an edition of the Douay Bible with extended commentary, compiled chiefly by his brother George Leo Haydock. Originally published in 1811 and still in print, it is one of the most enduring contributions to Catholic biblical studies. . . .

Haydock was born February 21, 1772 in Cottam, in the Fylde section of Lancashire in northern England. This is an area that was slow to accept the new Protestant religion. Speaking of Lancashire, Lord Burghley, advisor to Queen Elizabeth I complained, "The Papists every where are growen so confident, that they contempne Magistrats and their authoritie." In later centuries Lancashire would retain a small but determined Catholic population supported by families of the landed gentry, sometimes hosting secret Masses in their homes. The Haydocks were among the most prominent of these families and became legendary in their service to the Catholic Recusant movement. During the Elizabethan persecution, Father George Haydock (1556–1584), a "seminary priest", suffered martyrdom. He was beatified in 1987, earning the title “Blessed.” Early in the 18th century, Father Cuthbert Haydock (1684–1763) said secret Masses in a chapel hidden in the attic of Lane End House, Mawdesley, the home of his sister and brother-in-law.

Thomas Haydock was part of a unique generation whose combined contributions to this family tradition would be extraordinary. His father was a namesake of Blessed George Haydock. His two brothers both became priests. Older brother James (1765–1809) died caring for the sick of his congregation during a typhus epidemic. Younger brother George Leo (1774–1849), in addition to his work on the Bible, spent his career pastoring poor rural missions. A sister, Margaret (1767? - 1854), joined the Augustinian nuns, taking the name Sister Stanislaus.

He wanted to become a priest too:

After receiving his elementary education at a school established for Catholic students at Mowbreck Hall, Thomas was sent in 1785 to the English College, Douai, France, where he joined his brother, George. This institution was established for Catholic exiles in the 16th century to provide secondary education and preparation for the priesthood. His studies were interrupted in 1793, when the French revolutionary government declared war with England, closed the English College, and imprisoned some of its pro-England students. Both Haydock brothers managed to elude the authorities and escape back to England.

Continuing his pursuit of ordination, Thomas next went to the English College, Lisbon. His superiors there did not feel he had a priestly vocation and sent him home in 1795. Undeterred, he went to the new seminary established at Crook Hall, Durham with his brother George in 1796. Again, his vocation was questioned. Described as “easy going” (see also the “Tragic Personal Life” section below), he seems to have been judged by his superiors as constitutionally unsuited for the risks and hardships of the Catholic priesthood in Penal Period England. The eloquence and dedication Thomas expresses in his letters certainly support his sincerity; and his three attempts at the priesthood show his tenacity. However, against the wishes of his older and recently ordained brother James, he was finally persuaded to leave the seminary. Family friend and former Douay professor Benedict Rayment (1764–1842), who would later serve as editor of some of Haydock’s published works, remarked that of the three Haydock brothers seeking the priesthood, ‘’Thomas would have been the best’’.

Instead, he became a publisher of Catholic books, most notably his own brother George's commentary on the Douai-Rheims English translation of the Holy Bible. Although it was a very popular and important work, he struggled as a publisher:

Thomas Haydock had an enthusiasm for publishing, but was seriously lacking in business skills. He had a trustful nature that associates freely exploited, depriving him of profit and forcing him continually to operate on a shoestring. Although his Bible sold well, he lost money to his managers, clerks, and canvassers and was forced heavily into debt to an unscrupulous lender. Former Douay classmate Father (later Bishop) Robert Gradwell (1777–1860) wrote in August 1817 that Haydock was living in Dublin, “low in the world.” In 1818 he was arrested for debt and served four months in prison.

The experience did not discourage him from continuing his publishing business. By 1822 he was able to issue the first volume of a new edition of the Bible, a more modest undertaking this time, in a smaller octavo format and without the extended commentary of the folio edition. He had to take on several partners to complete the Bible’s second volume in 1824. This edition had many misprints, including the notable substitution of fornications for fortifications in II Corinthians 10:4. He had no known involvement with an American folio edition of the Haydock Bible published in Philadelphia in 1825.

Circa 1818 Haydock married Mary Lynch or Lynde of Dublin. Unfortunately, tragedy would dog his family life, just as it did his business. Mary died in 1823. Their three children all died young. The name of only one is known: George (1822–1840). Curiously, some books dated 1827 have the imprint, Thomas Haydock & Son. The apparent inconsistency between the publication date and the likely ages of any sons that could have been living at the time is a mystery.

Haydock struggled on with publishing at least until 1831, when he was able to reissue the New Testament portion of his original folio Bible. No dated works after that year are known, although he published undated works that may have appeared later. In 1832 he made an unsuccessful attempt to begin a journal called The Catholic Penny Magazine. At some point, he opened a school in Dublin where he resumed teaching until 1840. He left Dublin probably about that year and moved first to Liverpool, then to Preston. He could only watch as other publishers enjoyed success with new editions of his Bible: two British editions, one in 1845-48, another ca. 1853, and an American edition in 1852-4. He died at Preston in 1859, aged 87, with an estate valued at “less than 100 Pounds Sterling.” He was buried in the Haydock family grave at Newhouse Chapel, Newsham.

Published on February 20, 2013 22:30

St. Robert Southwell, SJ

St. Robert Southwell was 33 years old when he was executed at Tyburn on February 21, 1595. When he cited his age during his trial, his torturer Richard Topcliffe mocked him for claiming equality with Jesus Christ. Southwell answered that he was but a worm.

St. Robert Southwell was 33 years old when he was executed at Tyburn on February 21, 1595. When he cited his age during his trial, his torturer Richard Topcliffe mocked him for claiming equality with Jesus Christ. Southwell answered that he was but a worm.It is hard to be temperate when writing about his arrest, torture and execution--it is obviously a horrendous blot against the Elizabethan "regime". He was betrayed by a woman that Elizabeth's pursuivant Richard Topcliffe had raped and blackmailed--he promised to find her a husband since she was pregnant with his child if she would turn Southwell in; he was tortured--illegally and excruciatingly--numerous times, starting with a visit to Topcliffe's personal torture chamber, while Elizabeth's officials looked on; then he was held in fetid conditions until his father visited him in Westminster's gatehouse and petitioned the queen to put him to death rather than leave him there, in his own filth.Moved to the Tower of London he was held in greater but solitary comfort, but Queen Elizabeth allowed the sadistic Topcliffe to continue torturing Southwell, who had readily admitted his priesthood. Prior to his trial on February 20 he was moved into a hole called Limbo; the government did not even try to implicate him in any plot against the Queen; he was executed just because he was a Catholic priest. When he was executed on February 21st, the crowds made sure he was dead before the butchery began--and no one cheered when his severed head was displayed to the crowd. Indeed, Elizabeth's government recognized that they had gone too far--there was lull in executions of Catholic priests in London. Lord Cecil even ignored Topcliffe's desires to get started on new victims.Robert Southwell was canonized by Pope Paul VI among the group called The Forty Martyrs of England and Wales. In addition to be a great saint and steadfast martyr, he is regarded as one of the great poets of the Elizabethan Age. Much of his poetry was written while he was held in solitary confinement in the Tower of London and was published posthumously. One of the best accounts of his mission and his suffering is Philip Caraman's study of St. Robert Southwell's friendship with Father Henry Garnet, SJ, which I reviewed here.

Published on February 20, 2013 22:30

Happy Birthday to Blessed John Henry Newman

In honor of Blessed John Henry Newman's birthday on February 21, 1801, here is a great video from Corpus Christi Watershed, produced for his beatification by Pope Benedict XVI in 2010. I think this is the best melody and arrangement of "Lead, Kindly Light" (aka "The Pillar of the Cloud") that I have ever heard--it brings out the drama and the crucible of conversion. The composer's name is Kevin Allen.

Corpus Christi Watershed produced more videos before Newman's beatification, working with the Birmingham Oratory:

Newman Archivium Project

St. Philip Shrine Chapel

The Cardinal’s Personal Chapel

The Oratory Church and Prayer

Birmingham Oratory Church

Cardinal Newman’s Library

The Oratory Library and Learning

The Cardinal’s Room

Cardinal Newman Portrait Restoration

The Oratory Clock

The Cardinal’s Effects

Rednal • A Silent Film

Corpus Christi Watershed produced more videos before Newman's beatification, working with the Birmingham Oratory:

Newman Archivium Project

St. Philip Shrine Chapel

The Cardinal’s Personal Chapel

The Oratory Church and Prayer

Birmingham Oratory Church

Cardinal Newman’s Library

The Oratory Library and Learning

The Cardinal’s Room

Cardinal Newman Portrait Restoration

The Oratory Clock

The Cardinal’s Effects

Rednal • A Silent Film

Published on February 20, 2013 22:16

February 19, 2013

Catholic Connection with Vanessa Denha Garmo

RESCHEDULED FROM TUESDAY! {Teresa Tomeo was ill yesterday.}

Father Steve Mateja and I will be on Ave Maria Radio's Catholic Connection this morning at 8:15 EST (7:15 CST). We will promote the Catholic Martyrs of England Pilgrimage, discussing the purpose of the tour and its itinerary with host Teresa Tomeo substitute host Vanessa Denha Garmo! Audio archives for the show are stored here.

Here are the details of the itinerary (subject to change and adjustment):

Day 1: Departure

Depart USA on overnight flight to London, England

Day 2: Arrive in London (D)

Arrive in London and meet your English tour escort. Depart for the historically preserved town of York in northern England. Check into hotel and freshen up before a special Welcome Dinner and presentation on the English Catholic Martyrs (Three Reasons for Martyrdom: Henry VIII’s Supremacy, Elizabeth I’s Recusancy/Penal Laws, and the Popish Plot during the reign of Charles II). Overnight in York.

Day 3: York and the Yorkshire Martyrs (B)

This morning visit the St. Margaret Clitherow Shrine. Known as the “pearl of York” St. Margaret was martyred after refusing to admit or deny that she was hiding priests during the English Reformation. Afterwards, visit York Minster Cathedral, an imposing gothic church that is one of the largest of its kind. Then visit the English Martyrs Parish to celebrate Mass. After lunch visit the majestic Ruins and Gardens of St. Mary’s Abbey, once the largest and most powerful Abbey in northern England. Visit the storied York Castle and Site of York Tyburn (where martyrs were executed). This evening enjoy dinner on own. Overnight in York.

Day 4: Day Trip to Oxford (B|D)

Today, check out of hotel and depart for Oxford. Visit St. Mary’s in Oxford (Catholic, Anglican, and Protestant) Martyrs Shrine. Afterward visit the Oxford Oratory, Oriel and Trinity Colleges all sites associated with the life of Blessed John Henry Newman. Celebrate Mass at Oratory. Time for shopping at St. Phillip’s Bookstore. Continue on to London for dinner and overnight in London.

Day 5: London (B)

Today visit to the Tower of London and see the cell of St. Thomas More and Tower Green, his execution site. Visit also Beauchamp Tower to see graffiti by Catholic martyrs. See also the Chapel of St. John (site of St. Edmund Campion’s disputations with Anglican divines) and St. Peter ad Vincula (burial site of St. Thomas More and St. John Fisher). Afterwards visit the area of Westminster, famous for the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben, as well as the two great churches, Catholic Westminster Cathedral and, of course, Westminster Abbey. See the site of the various trials of St. John Fisher, St. Thomas More and St. Edmund Campion. Celebrate Mass at Westminster Cathedral and learn the story of St. John Southworth, Martyr of Westminster. Dinner on your own and overnight in London.

Day 6: Canterbury (B|D)

After breakfast set out for the city of Canterbury, destination of Chaucer’s pilgrims from the Canterbury Tales. It was also the most important ancient city in England and traditional home of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Today you will tour Canterbury focusing on the life of St Thomas Becket. It was in this city that the Saint was murdered in his own Canterbury Cathedral and was canonized shortly thereafter. You will also visit the house where St Thomas More’s eldest daughter Meg and her husband William Roper lived, opposite St Dunstan’s Church. The Roper family vault is where Thomas More’s head is buried. His daughter retrieved it after it was displayed on the Tower Bridge. Visit St. Thomas of Canterbury Catholic Church and celebrate Mass. Dinner and overnight in London.

Day 7: Arundel in Sussex (B)

Today depart for Arundel Castle with its sweeping grounds and gardens, it was built in the 11th century and is considered one of the great treasure houses of England with a history rich in Catholic tradition. Afterwards, visit Arundel Cathedral, dedicated to St. Philip Howard, and celebrate Mass. Return to London for dinner on your own and overnight.

Day 8: London (B|D)

This morning enjoy free time to explore London on your own. Visit the National Art Gallery, shop at the world-famous Harrods’s, or spend time like a local in Trafalgar Square. This afternoon visit to St. Etheldreda’s to celebrate Mass followed by a visit to the cloistered Benedictine Tyburn Convent to see the Tyburn Tree, site of martyrdom for many. Farewell dinner tonight and overnight in London.

Day Nine: Departure to USA (B)

After breakfast transfer to the airport for return flight to USA.

Published on February 19, 2013 22:30