Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 275

May 6, 2013

Religious Freedom, Here and There

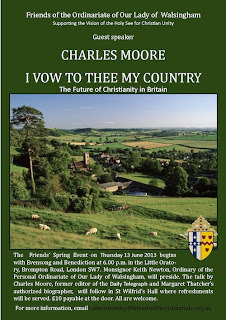

Here's a big event coming up in London, hosted by the Friends of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham.

Here's a big event coming up in London, hosted by the Friends of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham.The title of Charles Moore's talk comes from the poem by Sir Cecil Spring-Rice. Gustav Holst adapted the music from the "Jupiter" section of The Planets:

I vow to thee, my country—all earthly things above—

Entire and whole and perfect, the service of my love;

The love that asks no question, the love that stands the test,

That lays upon the altar the dearest and the best;

The love that never falters, the love that pays the price,

The love that makes undaunted the final sacrifice.

And there’s another country, I’ve heard of long ago—

Most dear to them that love her, most great to them that know;

We may not count her armies, we may not see her King;

Her fortress is a faithful heart, her pride is suffering;

And soul by soul and silently her shining bounds increase,

And her ways are ways of gentleness, and all her paths are peace.

Obviously, the poem and the patriotic hymn (as sung at Princess Diana's funeral) hold loyalty to two kingdoms in balance. There's love of the earthly country, patriotism and sacrifice for England, but ultimately, the greater loyalty has to be to Heaven and Heaven's King, God the Father.

According to the website for the Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham:

Charles Moore, the former editor of The Daily Telegraph, whose authorised biography of Margaret Thatcher has recently been published, is to give a talk on the future of Christianity in Britain at an event in London being organised by the Friends of the Ordinariate. The event will take place in the Little Oratory, Brompton Road, London, on Tuesday 13 June 2013. It will begin with Solemn Evensong & Benediction, celebrated by Mgr Newton and the renowned Oratory choir at 6pm. For more information, visit the website of the Friends of the Ordinariate, www.friendsoftheordinariate.org.uk. Tickets £10 on the door. All welcome.

I'm sure that freedom of religion in England, including the freedom of Christians to practice their faith even when it contradicts the secular government's positions, will be part of the discussion. R.R. Reno, editor of First Things, surveys the current situation of religious freedom in the United States in this month's Imprimis from Hillsdale College:

RELIGIOUS LIBERTY is being redefined in America, or at least many would like it to be. Our secular establishment wants to reduce the autonomy of religious institutions and limit the influence of faith in the public square. The reason is not hard to grasp. In America, “religion” largely means Christianity, and today our secular culture views orthodox Christian churches as troublesome, retrograde, and reactionary forces. They’re seen as anti-science, anti-gay, and anti-women—which is to say anti-progress as the Left defines progress. Not surprisingly, then, the Left believes society will be best served if Christians are limited in their influence on public life. And in the short run this view is likely to succeed. There will be many arguments urging Christians to keep their religion strictly religious rather than “political.” And there won’t just be arguments; there will be laws as well. We’re in the midst of climate change—one that’s getting colder and colder toward religion. . . .

Read the rest here, including the conclusion:

In conclusion, I want to focus not on fury but on the remarkable capacity for communities of faith to endure. My wife’s ancestors lived for generations in the contested borderlands of Poland and Russia. As Jews they were tremendously vulnerable, and yet through their children and their children’s children they endured in spite of discrimination, violence, and attempted genocide. Where now, I ask, are the Russian and Polish aristocrats who dominated them for centuries? Where now is the Thousand Year Reich? Where now is the Soviet worker’s paradise? They have gone to dust. The Torah is still read in the synagogue.

The same holds for Christianity. The Church did not need constitutional protections in order to take root in a hostile pagan culture two thousand years ago.

Published on May 06, 2013 22:30

May 5, 2013

London, May 6, 1590: Two Recusant Martyrs

As the

Catholic Encyclopedia

recounts, Blessed Edward Jones was one of Richard Topcliffe's victims, enduring the torture meted out by Elizabeth I's personal pursuivant:

As the

Catholic Encyclopedia

recounts, Blessed Edward Jones was one of Richard Topcliffe's victims, enduring the torture meted out by Elizabeth I's personal pursuivant:Blessed Edward Jones: Priest and martyr, b. in the Diocese of St. Asaph, Wales, date unknown; d. in London, 6 May 1590. Bred an Anglican, he was received into the Church at the English College, Reims, 1587; he was ordained priest in 1588, and went to England in the same year. In 1590 he was arrested by a priest-catcher, who pretended to be a Catholic, in a shop in Fleet Street. He was imprisoned in the Tower and brutally tortured by Topcliffe, finally admitting he was a priest and had been an Anglican. These admissions were used against him at his trial, but he made a skillful and learned defense, pleading that a confession elicited under torture was not legally sufficient to ensure a conviction. The court complimented him on his courageous bearing, but of course he was convicted of high treason as a priest coming into England. On the same day he was hanged, drawn, and quartered, opposite the grocer's shop where he had been captured, in Fleet Street near the Conduit.

Blessed Anthony Middleton: On the same day there suffered Anthony Middleton, priest and martyr, born probably at Middleton-Tyas, Yorkshire, date unknown, son of Ambrose Middleton of Barnard Castle, Durham, and Cecil, daughter of Anthony Crackenthorpe of Howgill Castle, Westmoreland. He entered the English College at Reims 9 Jan., 1582; was ordained 30 May 1586, and went to England in the same year. His work lay in London and the neighbourhood and he laboured very successfully; he was captured at a house in Clerkenwell (London) by the same artifice which was practiced on Father Jones. On the ladder he said: "I call God to witness I die merely for the Catholic Faith, and for being a priest of the true Religion"; and someone present called out, "Sir, you have spoken very well". The martyr was cut down and disemboweled while yet alive.

The observer's outcry was certainly a dangerous act--the usual procedure would be that the executioner would hold the decapitated head up and proclaim: "The head of a traitor" and the crowd would proclaim: "God Save the Queen!" Most irregular. Also irregular was Topcliffe's torture of Blessed Father Jones: Elizabeth I's government knew this procedure was not only irregular but illegal.--"It was during the time of the Tudors that the use of torture reached its height," wrote historian L.A. Parry in his 1933 book The History of Torture in England. "Under Henry VIII it was frequently employed; it was only used in a small number of cases in the reigns of Edward VI and of Mary. It was whilst Elizabeth sat on the throne that it was made use of more than in any other period of history."

The Golden Age of Elizabeth, indeed.

Published on May 05, 2013 23:00

Rogation Days Before the Feast of the Ascension

Like Ember Days, the Rogation Days were taken out of the Catholic Church calendar after the Second Vatican Council. In a sad way, both of these omissions reflect our separation or alienation from nature. I've heard a commercial for a radio station's severe weather coverage that asks, "Don't you think the weather has just gotten out of control?" Out of whose control? We certainly do not have control of the weather--and even listening to that station's severe weather coverage does nothing to control it! As this site reminds us, and these Rogation Days before the Solemnity of the Ascension of our Lord would remind us, we are definitely not in control:

"Rogation" comes from the Latin "rogare," which means "to ask," and "Rogation Days" are days during which we seek to ask God's mercy, appease His anger, avert His chastisements manifest through natural disasters, and ask for His blessings, particularly with regard to farming, gardening, and other agricultural pursuits. They are set aside to remind us how radically dependent we are on Mother Earth, and how prayer can help protect us from nature's often cruel ways.

It is quite easy, especially for modern city folk, to sentimentalize nature and to forget how powerful, even savage, she can be. Time is spent focusing only on her lovelier aspects -- the beauty of snow, the smell of cedar, the glories of flowers -- as during Embertides -- but in an instant, the veneer of civilization we've built to keep nature under control so we can enjoy her without suffering at her hand can be swept away. Ash and fire raining down from great volcanoes, waters bursting through levees, mountainous tidal waves destroying miles of coastland and entire villages, meteors hurling to earth, tornadoes and hurricanes sweeping away all in their paths, droughts, floods, fires that rampage through forests and towns, avalanches of rocks or snow, killer plagues, the very earth shaking off human life and opening up beneath our feet, cataclysmic events forming mountains and islands, animals that prey on humans, lightning strikes -- these, too, are a part of the natural world. And though nature seems random and fickle, all that happens is either by God's active or passive Will, and all throughout Scripture He uses the elements to warn, punish, humble, and instruct us: earth swallowing up the rebellious, power-mad sons of Eliab; wind destroying Job's house; fire raining down on Sodom and Gomorrha; water destroying everyone but Noe and his family (Numbers 16, Job 1, Genesis 19, Genesis 6). We need to be humble before and respectful of nature, and be aware not to take her for granted or overstep our limits. But we need to be most especially humble before her Creator, Who wills her existence and doings at each instant, whether actively or passively.

As this website notes, as individuals, we can keep these minor Rogation Days, the Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday before Ascension Thursday (except that we instead celebrate Ascension Sunday), by praying the Litany of Saints, exploring the boundaries of our parishes, blessing our own gardens, and praying for good weather, good harvests, and good stewardship of our natural resources--all the while remembering Who is really in control! As Gerard Manley Hopkins reminds us:

THE WORLD is charged with the grandeur of God.It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oilCrushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?Generations have trod, have trod, have trod; And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;And wears man’s smudge and shares man’s smell: the soilIs bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.And for all this, nature is never spent;There lives the dearest freshness deep down things; And though the last lights off the black West wentOh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs—Because the Holy Ghost over the bentWorld broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

"Rogation" comes from the Latin "rogare," which means "to ask," and "Rogation Days" are days during which we seek to ask God's mercy, appease His anger, avert His chastisements manifest through natural disasters, and ask for His blessings, particularly with regard to farming, gardening, and other agricultural pursuits. They are set aside to remind us how radically dependent we are on Mother Earth, and how prayer can help protect us from nature's often cruel ways.

It is quite easy, especially for modern city folk, to sentimentalize nature and to forget how powerful, even savage, she can be. Time is spent focusing only on her lovelier aspects -- the beauty of snow, the smell of cedar, the glories of flowers -- as during Embertides -- but in an instant, the veneer of civilization we've built to keep nature under control so we can enjoy her without suffering at her hand can be swept away. Ash and fire raining down from great volcanoes, waters bursting through levees, mountainous tidal waves destroying miles of coastland and entire villages, meteors hurling to earth, tornadoes and hurricanes sweeping away all in their paths, droughts, floods, fires that rampage through forests and towns, avalanches of rocks or snow, killer plagues, the very earth shaking off human life and opening up beneath our feet, cataclysmic events forming mountains and islands, animals that prey on humans, lightning strikes -- these, too, are a part of the natural world. And though nature seems random and fickle, all that happens is either by God's active or passive Will, and all throughout Scripture He uses the elements to warn, punish, humble, and instruct us: earth swallowing up the rebellious, power-mad sons of Eliab; wind destroying Job's house; fire raining down on Sodom and Gomorrha; water destroying everyone but Noe and his family (Numbers 16, Job 1, Genesis 19, Genesis 6). We need to be humble before and respectful of nature, and be aware not to take her for granted or overstep our limits. But we need to be most especially humble before her Creator, Who wills her existence and doings at each instant, whether actively or passively.

As this website notes, as individuals, we can keep these minor Rogation Days, the Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday before Ascension Thursday (except that we instead celebrate Ascension Sunday), by praying the Litany of Saints, exploring the boundaries of our parishes, blessing our own gardens, and praying for good weather, good harvests, and good stewardship of our natural resources--all the while remembering Who is really in control! As Gerard Manley Hopkins reminds us:

THE WORLD is charged with the grandeur of God.It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oilCrushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?Generations have trod, have trod, have trod; And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;And wears man’s smudge and shares man’s smell: the soilIs bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.And for all this, nature is never spent;There lives the dearest freshness deep down things; And though the last lights off the black West wentOh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs—Because the Holy Ghost over the bentWorld broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

Published on May 05, 2013 22:30

May 4, 2013

"A Little Latin and Less Greek"

No, I'm not talking about Shakespeare--I am speaking of myself. I did study Latin--four years in high school--and Greek--two semesters in college--but except for the fact we've been attending the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite of the Latin Liturgy the past few years, of course, I've forgotten it all.

No, I'm not talking about Shakespeare--I am speaking of myself. I did study Latin--four years in high school--and Greek--two semesters in college--but except for the fact we've been attending the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite of the Latin Liturgy the past few years, of course, I've forgotten it all.This article reminded me of one of parts of translating Latin in high school I enjoyed: the Greek names for all the figures of speech like metonymy and synecdoche, litotes, polysyndeton and asyndeton. We would play with these figures of speech in English and try to write sentences using them to great rhetorical effect--trying to emulate Cicero (see image) in our periodic sentences. Yes, I was a wild child in high school (meiosis!).

One of my favorite uses of polysyndeton, by the way, is this prayer by Blessed John Henry Newman:

May He support us all the day long, till the shades lengthen and the evening comes, and the busy world is hushed, and the fever of life is over, and our work is done. Then in His mercy may He give us a safe lodging, and a holy rest and peace at the last.

Amen.

Columnist Bryan A. Garner has this article in the May issue on the ABA Journal:

Have you ever wondered what it’s called when a speaker adds a superfluous syllable to the middle of a word, as by pronouncing athlete as /ATH-uh-leet/ instead of /ATH-leet/? Or Realtor as /REEL-uh-tur/ instead of /REEL-tur/? There’s a word for it: epenthesis (/ee-PEN-thuh-sis/). Just knowing this term could have a preventive (not “preventative”) effect on mispronunciations.

There are nuanced layers of technicality within the astonishingly large English vocabulary. For vowel epenthesis, as with the schwa sound that some speakers insert in athlete and Realtor, the more precise term (I kid you not) is anaptyxis. And what’s the word for the vowel itself—the one that gets thrust into the middle of a word so needlessly? We had to go to Sanskrit to import a word into English, and now it finds itself nicely ensconced in unabridged English dictionaries: the svarabhakti vowel (/swahr-uh-BAHK-tee/).

Like the Molière character who didn’t realize he’d been speaking prose all his life, you may not have known that you’ve been hearing (perhaps even pronouncing) svarabhakti vowels all your life: mostly the epenthetical schwa.

Garner also sites Farnsworth's Classical English Rhetoric which I have posted on before:

If you delight in technical terms and are an aficionado of classical rhetoric, check out Farnsworth’s Classical English Rhetoric. The dean at the University of Texas law school, Ward Farnsworth is perhaps the world’s leading expert on classical figures of speech.

Farnsworth doesn’t shrink from using big words and teaching about them. The very first word in his very first chapter I’ve long considered my all-time favorite since discovering it at age 16: epizeuxis (/ep-i-ZOOK-sis/), meaning emphatic repetition of a word. Think of Hamlet’s answer to Polonius, who asked what he was reading: “Words, words, words.”

And what if it’s a phrase that gets repeated, not a single word? That’s called epimone (/ee-PIM-uh-nee/). Think of perhaps the greatest 19th-century lawyer, Daniel Webster, speaking on the Senate floor in 1833: “The cause, sir, the cause! Let the world know the cause!” Or, if you prefer, the character Tattoo in the 1970s series Fantasy Island: “The plane! The plane!”

This website lists many of the classical tropes with some examples.

Published on May 04, 2013 22:30

May 3, 2013

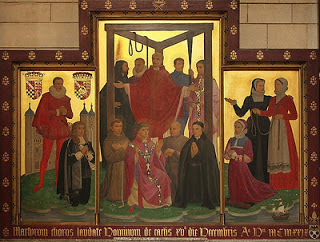

The Feast of The Catholic Martyrs of the Long English Reformation (1535 to 1681)

Today is the great feast honoring all of the Catholic Martyrs of the English Reformation--those canonized by Pope Paul VI and those beatified by Popes John Paul II, Pius XI, and Leo XIII--This feast was moved to this date in 2000 with a new liturgical calendar for the dioceses of England and Wales approved by the Vatican; then in 2010 it was elevated to a Feast (not just a Memorial). It is not a Feast or Memorial on the Liturgical Calendar in the USA--I think it should be!

Moving it to May 4 meant that the feast is celebrated on the anniversary of the protomartyrs of the English Reformation, the Priors of the Carthusian order, a parish priest, and the confessor and chaplain of the Brigittine order at Syon Abbey. These five men, St. John Houghton, St. Augustine Webster, St. Robert Lawrence, Blessed John Haile, and St. Richard Reynolds, were brutally executed at Tyburn before a crowd of Court witnesses. Some sources even suggest that Henry VIII was there in disguise. Drawn on hurdles from the Tower of London (whence St. Thomas More saw them depart), they were hung and quartered while still alive.

The Feast honors all the martyred saints, blessed and canonized from these protomartyrs, through all the others who suffered during the reign of Henry VIII. I call them the Supremacy Martyrs, because they suffered for their denial of Henry VIII's claim to be the Supreme Head and Governor of the Church of England. It includes the other Carthusians, the Observant Franciscans, St. John Stone, the Abbots of Glastonbury, Reading, and Colchester, Katerine of Aragon's Chaplains, Blessed Margaret Pole, the Prebendaries Plot victims, etc.

The Feast also honors all the martyred saints, blessed and canonized from throughout the reigns of Elizabeth I, James I, and Charles I, those whom I call the Recusant Martyrs, because they suffered under the recusancy or penal laws passed by successive Parliaments to eliminate the Catholic faith throughout England. That group includes everyone from the three women martyrs, St. Margeret Clitherow, St. Margaret Ward, and St. Anne Line, to the great Jesuits, St. Edmund Campion, St. Robert Southwell, St. Henry Walpole, Blessed Thomas Holland, and the many laymen who died because they protected or aided a Catholic priest: St. Swithun Wells, Blesseds John Mason, Sidney Hodgson, Richard Langley, Brian Lacey, Marmaduke Bowes, and those laymen who suffered because of the stubborn recusancy: St. Philip Howard, Blesseds James Bird, John Bretton, et al.

Finally, the Feast honors all the martyred saints, blessed and canonized from the reign of Charles II, innocent victims of the Popish Plot, who suffered the double injustice of the recusancy laws and the twisted legal system of England (witnesses prevented from testifying; Oates and his conspirators' evidence valued above the Catholic witnesses, obvious anti-Catholic bias in court, etc): St. John Kemble, St. John Wall, Blessed William Howard, St. Oliver Plunkett, St. David Lewis, Blessed Richard Langhorne, et al.

The list of all these names makes quite a great litany of saints for private devotion! And this blog offers this excellent closing prayer for the litany:

Glorious English Martyrs, you had the courage to witness for Christ before men without counting the cost. Help us to have this same courage in our day.

Glorious English Martyrs, you had a profound love of truth, and would not deny it even though this meant suffering and death. Give us the same love of truth, and zeal for the faith, that you had.

Glorious English Martyrs, at the heart of all you did and endured was the love of God. Help us to know this love, and to pass it to our neighbour.

Glorious English Martyrs, you readily forgave those who persecuted you, and offered your sufferings for their conversion. Intercede for us to have something of the same spirit in the face of injustice or persecution.

Glorious English Martyrs, you persevered in your witness to the end, and joyfully accepted the sufferings that opened to you the Kingdom. Intercede for us, and those who are near to death, or undergoing a trial of faith, that we too may have the grace of final perseverance.

Amen.

Published on May 03, 2013 22:30

May 2, 2013

From the Author of "The Crown" and "The Chalice"

The Catholic Herald features this article by Nancy Bilyeau, the author of two historical fiction novels set in the reign of Henry VIII and featuring a young almost nun who has been cast out of her Dominican convent by the Dissolution of the Monasteries. I've read The Crown, but have also enjoyed Bilyeau's non-fiction essays describing the historical background of this era. This article exemplifies that pleasure :

I began my journey as a life-long Tudor history addict but fairly ignorant of the specifics of the religious orders. I had no spiritual agenda; I was raised by agnostic parents in the American Midwest. But after I learned a family secret when I was 19, I felt increasing curiosity about the Catholic Church. In the last month of her life, my grandmother told my mother that while she and my grandfather, Francis Aloysius O’Neill, babysat me as an infant, they took me to a priest in Chicago, Illinois, for baptism. The first priest they approached for baptism without the parents being present said no; the second one said yes. I was baptised in the Catholic Church but for nearly 20 years did not know it.

After university, I moved to New York City to work in the magazine business. Occasionally I found myself on Fifth Avenue in midtown and would slow down as I approached St Patrick’s Cathedral. I’d walk up the steps, push open the heavy doors, and slide inside to look at the magnificent 330ft-tall space. “Do I belong here?” I’d ask myself as I watched people light candles and pray.

Now, with a plan to write a historical thriller, I dived into my research of the Dissolution of the Monasteries. In most books on the reign of Henry VIII the refrain is the same: the numbers of monks, priests and nuns had dwindled by the 16th century, and many questions had already been raised about the abbeys’ financial and moral soundness. After the monasteries were closed and their occupants evicted, no one much cared, except for some rebels in a failed uprising in the north known as the Pilgrimage of Grace.

Two books that went deeper into the topic made me start to question that conventional wisdom: G W Bernard’s The King’s Reformation described the extreme brutality the king doled out to those who opposed him. It went beyond the executions of Sir Thomas More and Cardinal John Fisher – monks and friars who did not want to forsake the pope and swear an oath to Henry VIII as the head of the church were imprisoned, starved, hanged, beheaded and even carved into pieces. Eamon Duffy’s The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England made a convincing argument that the Catholic faith was a vibrant and essential part of daily life when Henry VIII broke from Rome because he could not get an annulment from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. Most significantly, by dissolving the monasteries the king was able to seize a colossal amount of money.

As with the book I recently reviewed, Treason, by Dena Hunt, Bilyeau's historical fiction has to be judged first for its qualities and effectiveness as a work of fiction. But their influence on readers' impressions of English history are also important--that's the great mixture of historical fiction, when it's well done. It can lead readers to nonfiction works to understand the background of the work, especially when the story seems to contradict the "conventional wisdom". And in the case of the English Reformation, either when dealing with the Dissolution of the Monasteries on the martyrdoms of Catholic priests during the reign of Elizabeth I, I think Supremacy and Survival: How Catholics Endured the English Reformation is a good introduction!

Published on May 02, 2013 22:30

May 1, 2013

Four Important Events on May 2

1536 – Anne Boleyn, Queen of England, is arrested and imprisoned on charges of adultery, incest, treason and witchcraft. She was taken to the Tower of London and to the very apartments she had used before her coronation:

1536 – Anne Boleyn, Queen of England, is arrested and imprisoned on charges of adultery, incest, treason and witchcraft. She was taken to the Tower of London and to the very apartments she had used before her coronation:As you know, Anne Boleyn was arrested on 2nd May 1536 at Greenwich Palace. Alison Weir writes of how Anne was accused of “evil behaviour” by Sir William Paulet, Sir William Fitzwilliam and her uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, charged with adultery and informed that both Mark Smeaton and Sir Henry Norris had confessed their guilt. Anne denied these charges but it was no good, she was allowed to return to her apartments for her dinner, under guard, and then she was escorted by barge along the Thames to the Tower of London.

Although Traitor’s Gate is often pointed out as the place where Anne would have disembarked, Alison Weir points out that Anne, as Queen, was taken to the Court Gate in the Byward Tower, a private entrance. Here she was met by the Lieutenant of the Tower, Sir Edmund Walsingham, who was Sir William Kingston’s deputy and then Anne would then have been escorted along Water Lane (in the Outer Ward), past the back of the Lieutenant’s House to the entrance of the royal palace where she was to be imprisoned.

It was ironic that Anne Boleyn was imprisoned in the same lodgings that she stayed in before her coronation in 1533 – the Queen’s apartments in the Tower’s royal palace.

But where are these lodgings?

In “The Lady in the Tower”, Weir describes Anne’s lodgings as lying “on the east side of the inner ward between the Lanthorn Tower and the Wardrobe Tower” and writes of how these apartments were renovated for Anne’s coronation, with Cromwell spending the equivalent of over £1 million pounds to make them fit for the new queen. These Renaissance style apartments were therefore a luxurious prison for Anne Boleyn but a prison is a prison. If you go to the Tower of London today, it is not possible to see Anne’s prison because these lodgings were uninhabitable by the end of the 16th century and demolished by the end of the 18th century. The present half-timbered Queen’s House which overlooks the green is not where Anne was imprisoned as these apartments were not built until around 1540, at least 4 years after Anne Boleyn’s execution.

1559 – John Knox returns from exile to Scotland to become the leader of the beginning Scottish Reformation. He was thus able to contribute to the revolution that overturned the regency of Queen Mary of Guise for her daughter Mary, the Dauphine of France and Queen of Scotland, draft the Scots Confession for the Parliament, and argue with Mary, Queen of Scots.

1568 – Mary, Queen of Scots, escapes from Loch Leven Castle. She had been imprisoned there after the death of her husband Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, and her abduction by and marriage to Lord Bothwell. Having lost the battle of Carberry Hill on June 15, 1567 before it even began, Mary was taken in custody to Edinburgh and then imprisoned in Loch Leven, where she miscarried and forced to abdicate. Then she escaped on May 2 and lost the battle of Landside eleven days later. By the middle of May in 1568 she was in England and in Elizabeth's custody.

1611 – King James Bible is published for the first time in London, England, by printer Robert Barker. According to the wikipedia article, things did not go smoothly:

The original printing of the Authorized Version was published by Robert Barker, the King's Printer, in 1611 as a complete folio Bible.It was sold looseleaf for ten shillings, or bound for twelve. Robert Barker's father, Christopher, had, in 1589, been granted by Elizabeth I the title of royal Printer, with the perpetual Royal Privilege to print Bibles in England. Robert Barker invested very large sums in printing the new edition, and consequently ran into serious debt, such that he was compelled to sub-lease the privilege to two rival London printers, Bonham Norton and John Bill. It appears that it was initially intended that each printer would print a portion of the text, share printed sheets with the others, and split the proceeds. Bitter financial disputes broke out, as Barker accused Norton and Bill of concealing their profits, while Norton and Bill accused Barker of selling sheets properly due to them as partial Bibles for ready money. There followed decades of continual litigation, and consequent imprisonment for debt for members of the Barker and Norton printing dynasties, while each issued rival editions of the whole Bible. In 1629 the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge successfully managed to assert separate and prior royal licences for Bible printing, for their own university presses – and Cambridge University took the opportunity to print revised editions of the Authorized Version in 1629 and 1638. The editors of these editions included John Bois and John Ward from the original translators. This did not, however, impede the commercial rivalries of the London printers, especially as the Barker family refused to allow any other printers access to the authoritative manuscript of the Authorized Version.

Published on May 01, 2013 23:00

April 30, 2013

The Feast of the Martyrs of England and Wales on the Radio

I'll be on the Son Rise Morning Show Friday morning, May 3 to highlight once again the great Feast of the Martyrs of England and Wales, which is on Saturday, May 4 in the Dioceses of England and Wales. Brian Patrick and I will discuss the martyrs and their feast, which is set on the day the protomartyrs of the English Reformation suffered and died at Tyburn in 1535, at 7:45 a.m. Eastern--6:45 a.m. Central (where I am!)

Then on Monday afternoon, May 6, I'll be on Kresta in the Afternoon to discuss the same feast (Al Kresta is on retreat this week so we'll talk then from 4:35 to 4:55 p.m. Eastern--3:35 to 3:55 p.m. Central.

With both of these interviews, I do want to highlight the upcoming Catholic Martyrs of England Pilgrimage, pointing out that our tour will visit several sites and shrines associated with these martyrs:

York: St. Margaret Clitherow and St. Henry Walpole, and several other priests, including two of the Carthusians of the Charterhouse in London, were martyred there; York was a major center of recusancy;

Oxford: Many of the priests who suffered martyrdom during the reigns of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I were former students at the University of Oxford, including St. Edmund Campion, St. Cuthbert Mayne, St. Ralph Sherwin; and four martyrs were executed in Oxford: Blessed George Nichols and Blessed Richard Yaxley, priests; Blessed Thomas Belson and Blessed Humphrey Pritchard, laymen;

Canterbury: Not only the site of St. Thomas a Becket's martyrdom but also of St. John Stone, Augustinian Canon (executed after Christmas in 1539) and the Oaten Hill martyrs, executed after the failure of the Spanish Armada: Blessed Edward Campion, Blessed Christopher Buxton, Blessed Robert Wilcox, and Blessed Robert Widmerpool--and there's the St. Thomas More connection as his head is buried in St. Dunstan's Anglican church;

London: St. Thomas More, St. John Fisher and many, many others (St. Robert Southwell, St. Oliver Plunkett, St. Anne Line, et al) suffered both at the Tower of London and at Tyburn Tree, and at various other sites in London, including Smithfield, where Blessed John Forrest was burned alive;

Arundel: not the site of martyrdom, but an important shrine at the Cathedral of St. Philip Howard and the location of splendid Arundel Castle, with its exhibit of "relics" of Mary, Queen of Scots and a fascinating chapel.

This pilgrimage, since I developed the itinerary at Corporate Travel Services' request, is unique in its focus on the English martyrs and in the selection of cities and sights to visit. With daily Mass in so many historically significant places (the Parish of English Martyrs in York; St. Aloysius Oratory Church in Oxford; St. Thomas of Canterbury Catholic Church in Canterbury; the Cathedral of St. Philip Howard in Arundel, and St. Etheldreda's and Westminster Cathedral in London!) the spiritual blessings of the pilgrimage will be as great as the historical background we'll all share. All the English Martyrs, pray for us!

Published on April 30, 2013 22:30

April 29, 2013

One of Henry VIII's Loyal Servants: Thomas Audley

Thomas Audley, lst Baron Audley of Warren died on April 30, 1544--he managed to die safely in his bed with his head intact by serving Henry VIII very well. A lawyer by training, Audley served Cardinal Wolsey and served in Parliament, representing Essex and he continued to rise in office throughout Henry VIII's reign.

Audley participated in the trials and executions of not only Thomas More and John Fisher, but also of Anne Boleyn and Thomas Cromwell, and he sentenced the rebels of the Pilgrimage of Grace to death. For these and other services (the annulment of Henry VIII's marriage to Anne of Cleves, for instance), he was not only knighted but became a member of the Order of the Garter. Audley was Lord Keeper of the Great Seal from 1532, when he succeeded Thomas More, to 1544, when he resigned it on April 21. He also succeeded Thomas More as Speaker of the House of Commons in 1529 and as Lord Chancellor in 1533. According to this parliamentary history website, there has been some controversy about his activity at these trials and about his religious positions:

If his knightly status exempted Audley from the trial of Anne Boleyn in 1536 (it was not he but John, 8th Lord Audley, who took part in this), he was involved in all the other state trials of these years. His conduct in these trials, and especially in More’s, has been much criticized but it deserves to be judged in the light of Audley’s own beliefs concerning the rights of the sovereign and the duties of the subject. No such criticism, despite occasional and clearly prejudiced charges of favouritism and corruption, can be levelled against his conduct as an equity judge, and even in cases of treason his attitude is illustrated by his advice in 1536 that the Duke of Suffolk should be armed against the Lincolnshire rebels with a commission to try cases of treason, showing that he took for granted, even in such circumstances, the necessity of a trial at common law.

Audley’s religious position is difficult to assess. A correspondent of Melanchthon named him with Cromwell and Cranmer as friends to Protestantism but, if he was, the friendship was always qualified by his allegiance to the King whose policies he faithfully carried out, a course which in general gives an impression of conservatism. Thus an anonymous enthusiast for the Act of Six Articles (31 Hen. VIII, c.14) again linked Audley with Cromwell as two men who, this time in contrast to Cranmer and to other bishops, had been ‘as good as we can desire’ in the furtherance of the measure. Audley was equally content to follow Cromwell’s lead and what few clashes there were between them arose largely out of minor questions of patronage.

Audley also benefitted from the Dissolution of the Monasteries, receiving grants of Holy Trinity Priory in Aldgate, London (which had been founded by Queen Matilda or Maud, Henry I's wife) and Walden Abbey, where his grandson, Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk built Audley End, which is now part of the English Heritage program. He founded Magdalene College at the University of Cambridge in 1542, after the Benedictine's Buckingham College was closed.

Audley's title as lst Baron Audley of Warren died with him. One of his daughters, Margaret, married Thomas Howard, the 4th Duke of Norfolk (who was executed by Elizabeth I).

Published on April 29, 2013 22:30

April 28, 2013

"Treason" Historical Fiction Plus Tension

I requested and received a review copy of Dena Hunt's historical novel published by Sophia Institute Press; the book arrived Friday in the mail and I finished it Saturday. Except for one issue of historical accuracy, I found the book to be an exciting and effective story about recusant Catholics and missionary priests in Elizabethan England.

I requested and received a review copy of Dena Hunt's historical novel published by Sophia Institute Press; the book arrived Friday in the mail and I finished it Saturday. Except for one issue of historical accuracy, I found the book to be an exciting and effective story about recusant Catholics and missionary priests in Elizabethan England.Matching the achievement of Robert Hugh Benson in depicting the religious conflict and crisis of Reformation England, Dena Hunt adds the element of suspense in Treason: A Catholic Novel of Elizabeth England. With omniscient narration weaving several different story lines in several different locations to a seven day plot, Hunt depicts the underground lives of a missionary priest, the recusant Catholics who shelter him, an unhappily wed wife, an Anglican minister who secretly reads Catholic texts from the Fathers of the Church, and a wealthy family whose home hides many secrets. The various plot lines all come together on the seventh day, and the epilogue depicts the Eighth Day, when two vocations are fulfilled.

Readers of Benson will recognize one of the supporting characters in Hunt's ensemble: Patricia, the Reverend Andrew Wilson's wife resembles Lady Torridon of The King's Achievement in her cold demeanor and dark black eyes and Marion Dent, the Rector's wife in By What Authority in her effect on the recusant Catholics in her village--but without the ducking! But where Benson builds up the tension year after year from 1570 to 1581 and beyond, Hunt presents all that action rapidly, as the main characters meet along the way until they gather at the Anders' home in Somerset and the chaotic climax of the story.

While Hunt keeps up the pace and the novel reads swiftly and easily, she does pause for passages of beautiful description--like this, when Caroline, one of the main characters, explores the grounds of a destroyed convent years after Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries:

The emptiness of it all was so strangely full--like its silence, so deep that it was full of sound. Everything, every place in this ruin, was full of its own contradiction, like two worlds existing together, in the same place, at the same time. How could that be? It was as though there had been a sketch over which a contradictory overlay had been placed in an attempt to eradicate it. But that hadn't happened. Instead, the two realities existed together, and instead of the intended contradiction, the overlay had made something else altogether. Destruction had been transformed into creation--its intention notwithstanding--and it was a creation greater, more beautiful, than the reality it meant to destroy. Destruction had succeeded only in making it eternal.

There are other passages of similar depth as the characters try to reconcile how much they have to hide with how much they want to share their faith and love. Each of them struggles with what they must do to remain true to that faith and love while striving to survive. As Father Stephen tells Caroline when she confesses deceit, "Everyone has to be deceptive now."

The only quarrel I have with the book is the year in which Hunt sets it: 1581. It was not an act of treason to be a Catholic priest in England in 1581; that law was not passed until 1585. The great litany of martyred priests had not yet begun in 1581 as the English mission was redeveloping slowly after the execution of Cuthbert Mayne in 1577; Saints Edmund Campion, Ralph Sherwin, and Alexander Briant would suffer on December 1, 1581. If Father Stephen Long or the two other priests mentioned in the story were to be sentenced to death for treason in the May of 1581, it would not have been for their priesthood and presence in England per se; it would have been for their efforts to convert Anglicans (1581 law), for defending papal supremacy in the Church (1563 law), or for calling Elizabeth a heretic or a schismatic (1571). After 1585, it would be treason for a Jesuit or seminary priest to enter the country (27 Eliz., c. 2)--and I think that Hunt would have done well to set her Catholic novel of Elizabethan England after 1585.

Contents:

Introduction by Joseph PearcePreface by Dena Hunt

Prologue1. The twenty-first of May, in 1581 (in Devonshire)2. The same day, in Somerset3. The next morning, May 22, in Blexton4. The following day, May 23, on the road to Bath5. The morning of May 24, at The Rose and Thorn6. The evening of the same day, May 247. The morning of May 258. The morning of May 269. The afternoon of the same day, the twenty-sixth of May10. The twenty-seventh of May

Epilogue: The fifteenth day of August 1581

It's a very effective historical novel; well-paced and plotted: highly recommended.

Published on April 28, 2013 22:30