Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 274

May 13, 2013

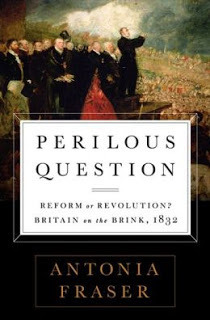

Reform or Revolution in Britain? The Latest by Antonia Fraser

Antonia Fraser, biographer of Mary, Queen of Scots and Marie Antoinette, Cromwell, and Charles II has written a history of the Parliamentary reform movement in 1832:

Antonia Fraser, biographer of Mary, Queen of Scots and Marie Antoinette, Cromwell, and Charles II has written a history of the Parliamentary reform movement in 1832:Antonia Fraser, international and bestselling historian, tackles the two-year revolution that totally changed Britain in her new book, The Perilous Question. Fraser brilliantly evokes the key period of pre-Victorian political and social history - the passing of the 1832 Great Reform Bill.

For our inconclusive times, there is an attractive resonance with 1832, with its 'rotten boroughs' of Old Sarum and the disappearing village of Dunwich, and its lines of great resistance to reform. This book is character-driven - on the one hand, the reforming heroes are the Whig aristocrats Lord Grey, Lord Althorp, Lord John Russell, Lord Brougham and the Irish orator Daniel O'Connell. They included members of the richest and most landed Cabinet in history, yet they were determined to bring liberty, which whittled away their own power, to the country. The all-too-conservative opposition comprised Lord Londonderry, the Duke of Wellington, the intransigent Duchess of Kent and the consort of the Tory King William IV, Queen Adelaide. Finally, there were 'revolutionaries' and reformers, like William Cobbett, the author of Rural Rides.

This is a book that features a most eventful year, much of it violent. Riots in Bristol, Manchester and Nottingham, and wider themes of Irish and 'negro emancipation' underscore the narrative. The time-span of the book is from Wellington's intractable declaration in November 1830 that 'The beginning of reform is the beginning of revolution', to 7th June 1832, the date of the extremely reluctant royal assent by William IV to the Great Reform Bill; under the double threat of the creation of 60 new peers in the House of Lords and the threat of revolution throughout the country. These events led to a complete change in the way Britain was governed, a two-year revolution that Antonia Fraser brings to vivid and dramatic life.

Because this great reform movement begins just a year after the passage of Catholic Emancipation in Parliament, I would be interested in exploring the connections between these reform movements. Some of the same characters are involved in these reforms--Daniel O'Connell, the Duke of Wellington, Robert Peel, etc--and these major steps in reform are related. Yet another book to consider on a reading list! Her main challenge, I am sure, is to make the achievement of relatively moderate advances in voting rights and reapportioning parliamentary districts a compelling story without making the Tories seem horribly reactionary.

Published on May 13, 2013 22:30

May 12, 2013

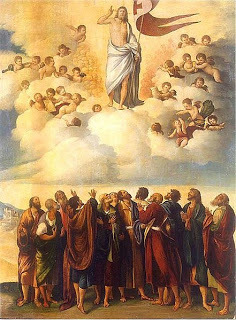

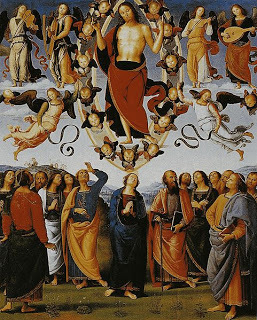

Venerable Bede's Hymn for the Ascension of Our Lord

We sang this hymn, translated from the Latin of the Venerable Bede by Benjamin Webb, at Mass for Ascension Thursday Sunday yesterday:

We sang this hymn, translated from the Latin of the Venerable Bede by Benjamin Webb, at Mass for Ascension Thursday Sunday yesterday:A hymn of glory let us sing:

New songs throughout the world shall ring:

Alleluia! Alleluia!

Christ, by a road before untrod,

Ascendeth to the throne of God.

Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia!

The holy apostolic band

Upon the Mount of Olives stand;

Alleluia! Alleluia!

And with his followers they see

Jesus' resplendent majesty.

Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia!

To whom the angels, drawing nigh,

"Why stand and gaze upon the sky?

Alleluia! Alleluia!

This is the Saviour!" thus they say;

"This is his noble triumph-day."

Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia!

"Again shall ye behold him so

As ye today have seen him go

Alleluia! Alleluia!

In glorious pomp ascending high,

Up to the portals of the sky."

Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia!

Oh, grant us thitherward to tend

And with unwearied hearts ascend

Alleluia! Alleluia!

Unto thy kingdom's throne, where thou,

As is our faith, art seated now.

Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia!

Be thou our Joy and strong Defence

Who art our future Recompense:

Alleluia! Alleluia!

So shall the light that springs from thee

Be ours through all eternity.

Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia!

O risen Christ, ascended Lord,

All praise to thee let earth accord,

Alleluia! Alleluia!

Who art, while endless ages run,

With Father and with Spirit One.

Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia!

I've always liked the phrase "the holy apostolic band" and have often wondered if a Christian rock group should adopt it as their name! This website has a post analysing the text of Bede's poem.

Hymnum canamus gloriae

Hymni novi nunc personent,

Christus novo cum tramite

Ad Patris ascendit thronum.

Transit triumpho gloriae

Poli potenter culmina,

Qui movete mortem absumserat,

Derisus a mortalibus.

Erant in admirabili

Regis triumpho alti throni

Coetus simul coelestinum

Polum petentes agminum.

Apostoli tum, mystico

In montes stantes chrismatis

Cum matre claram virgine

Iesu videbant gloriam.

Published on May 12, 2013 22:30

May 11, 2013

Gatsby, Morality, and Mr. Blue

Father Alexander Lucie-Smith previews the new movie version of The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald's great novel of the "Roaring Twenties", in The Catholic Herald:

What a strange world it is, the world of the novel! The reality that the characters live in is wafer-thin, and under the brittle and glassy surface, unpleasant truths lurk. The climactic scenes both centre around dead bodies, as if this were the terrible fact from which humanity is fleeing. In the end the novel is about death, and how we can never cheat it, how it stalks us through life. There is something elemental about the world of Gatsby: on the one hand it is about all the things people want: love, power, money, renown, glamour; at the same time it is telling us that none of these things are lasting, all of them turn to dust and ashes. Gatsby’s palatial mansion on Long Island turns out to be as false as a Potemkin façade.

Gatsby is not really a religious novel, but it is, in an odd way, a moral novel, telling us about the emptiness to be found in the heart of human desire, the hollowness of life. It is close in spirit (as well as date) to T S Eliot’s famous poem The Wasteland. It may not tell us anything about religion or the life of the spirit, but it makes one thing clear. The world is an empty place, and we need some spiritual truths to make life bearable; and faith is the best refuge we have from the sterility of life and the pressing nature of death. Or so it seems to me: I wonder how the film will confront these existential themes?

Father Lucie-Smith's comments reminded me of Father John Breslin's comments in his introduction to Myles Connolly's Mr. Blue, that J. Blue was the Catholic Jay Gatsby:

In 1925, F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby appeared, a year after Chesterton's St. Francis of Assisi and three years before Mr. Blue. The brief novel, now an academic classic, recounts the story of Jay Gatsby, a mysterious millionaire who takes his place, somewhat brashly, among the moneyed aristocracy of eastern Long Island in pursuit of Daisy Buchanan, the love of his impoverished youth.

In the very first sentence of his novella, Myles Connolly identifies his hero as J. Blue. Could that be a coincidence? Hardly, for someone as well read as Connolly. Jay Gatsby stands for everything that Blue, three years later, rejects: the pursuit of great wealth, the willingness to do whatever it takes to win, the craving for status and acceptance. Gatsby is also, as Blue turns out to be, bigger than life, lavish in style, doomed to die young, a striking figure who fascinates and puzzles his own half-admiring chronicler, the reserved future journalist Nick Carraway.

Can we imagine Gatsby and Blue inhabiting the same space in the Jazz Age before the Crash? Despite their commitments to radically different value systems, these two might have hit it off. Certainly, the view from the skyscraper would have stirred Gatsby; he might even have been able to pick out the light on Daisy's dock in East Egg, with the help of binoculars. And certainly the lavish style Blue takes up briefly on inheriting a fortune--multiple houses, limousines, world trips--would have appealed to Jay Gatsby. But Blue's true delight in his wealth is in giving it away as fast as possible, hiring servants and then setting them up in their own homes, keeping his fortune in over a hundred checking accounts so he can write checks at any time.

There is a startling echo of Jay Gatsby in Connolly's book. Halfway through Gatsby, Nick Carraway reveals the millionaire's origins as Jay Gatz, the son of a shiftless farmer, who re-created himself as the worldly Jay Gatsby, sprung "from his Platonic conception of himself. He was a son of God, a phrase which, if it means anything, means just that, and he must be about his Father's business, the service of a vast, vulgar, and meretricious beauty."

Contrast that with Blue's apostrophe to the stars from the roof of his Manhattan skyscraper: "God is more intimate here. . . . Don't you find Him so? This is height without desolation, isolation without emptiness. . . . I think my heart would break with all the immensity if I did not know that God Himself once stood beneath it, a young man, as small as I. . . . I'm no microcosm. I, too, am a Son of God!"

Blue and Gatsby clearly serve different Gods, who nonetheless lead each of them to an early grave. Their deaths, however, could hardly be more different. Worshiping mammon and his memory of Daisy, Jay Gatsby finds himself defeated by both. Daisy refuses to admit that she never loved her husband, Tom, thereby destroying Gatsby's romantic dream. Moreover, her willingness to let Gatsby shoulder responsibility for her reckless driving--which killed Tom's mistress--costs Gatsby his life, at the hands of the victim's aggrieved husband.

J. Blue also dies because of the reckless driving of the rich. And like Gatsby, he dies protecting someone else, pushing a homeless black man out of danger and taking the blow from the speeding limousine himself. But there the parallel stops. What propels Blue, like Gatsby, is a dream, but a selfless one, founded on the gospel example of Jesus and renewed in a quite literal way a millennium later by the man from Assisi. Blue has chosen a way of life that startles, challenges, and puzzles the people around him just as thoroughly as Jesus and Francis did in their times.

From the couple of reviews of Baz Luhrman's new film I've read, I don't think that I will see it--sounds too frenetic for me. Perhaps TCM will show the Alan Ladd version this month!

Published on May 11, 2013 23:00

Happy Mother's Day! May as Mary's Month

The MAY Magnificat by Gerard Manley Hopkins

MAY is Mary’s month, and I

Muse at that and wonder why:

Her feasts follow reason,

Dated due to season—

Candlemas, Lady Day;

Why fasten that upon her,

With a feasting in her honour?

Is it only its being brighter

Than the most are must delight her?

Is it opportunest

And flowers finds soonest?

Ask of her, the mighty mother:

Her reply puts this other

Question: What is Spring?—

Growth in every thing—

Flesh and fleece, fur and feather,

Grass and greenworld all together;

Star-eyed strawberry-breasted

Throstle above her nested

Cluster of bugle blue eggs thin

Forms and warms the life within;

And bird and blossom swell

In sod or sheath or shell.

All things rising, all things sizing

Mary sees, sympathising

With that world of good,

Nature’s motherhood.

Their magnifying of each its kind

With delight calls to mind

How she did in her stored

Magnify the Lord.

Well but there was more than this:

Spring’s universal bliss

Much, had much to say

To offering Mary May.

When drop-of-blood-and-foam-dapple

Bloom lights the orchard-apple

And thicket and thorp are merry

With silver-surfèd cherry

And azuring-over greybell makes

Wood banks and brakes wash wet like lakes

And magic cuckoocall

Caps, clears, and clinches all—

This ecstasy all through mothering earth

Tells Mary her mirth till Christ’s birth

To remember and exultation

In God who was her salvation.

Published on May 11, 2013 22:30

May 10, 2013

The Carthusian Martyrs at York; Hanging in Chains

Two of the Carthusians of the Charterhouse of London began their agonizing and slow death by being hung in chains from the York city battlements: Blessed John Rochester and Blessed James Walworth. They were beatified by Pope Leo XIII on the 20th of December in 1886 or 1888 (I've found two sources with two dates!).

After the first three Carthusian priors were executed on May 4, 1535, the next three leaders in line, Humphrey Middlemore, William Exmew and Sebastian Newdigate, were executed on June 19 that same year and these two monks were taken from London to the Charterhouse of St. Michael in Hull.

In the wake of the Pilgrimage of Grace, Rochester and Walworth were tried in York by Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk and found guilty of treason.

The Catholic Encyclopedia offers this detail about Blessed John Rochester:

Priest and martyr, born probably at Terling, Essex, England, about 1498; died at York, 11 May, 1537. He was the third son of John Rochester, of Terling, and Grisold, daughter of Walter Writtle, of Bobbingworth. He joined the Carthusians, was a choir monk of the Charterhouse in London, and strenuously opposed the new doctrine of the royal supremacy. He was arrested and sent a prisoner to the Carthusian convent at Hull. From there he was removed to York, where he was hung in chains. With him there suffered one James Walworth (?Wannert; Walwerke), Carthusian priest and martyr, concerning whom little or nothing is known. He may have been the "Jacobus Walwerke" who signed the Oath of Succession of 1534. John Rochester was beatified in 1888 by Leo XIII.

It must have been an agonizing death--hanging until death by exposure and dehydration--left like their brother Carthusians in Newgate Prison in London. When Rowan Williams, who resigned last year as Archbishop of Canterbury, remembered the Carthusian martyrs at the Charterhouse in London in 2010, he quoted H.F.M. Prescott's The Man on a Donkey and her description of Robert Aske's sufferings while hanging in chains, dying slowly by hunger, thirst, and exposure:

And towards the end of that extraordinary novel, we watch and listen to Robert Aske, the leader of the Pilgrimage of Grace, in his last anguished moments, hanging in chains from the Keep of the Castle in York: "God did not now nor would in any furthest future prevail. Once he had come and died. If he came again, again he would die, and again and so forever, by his own will, rendered powerless against the free and evil wills of men. Then Aske met the full assault of darkness without reprieve of hoped for light, for God ultimately vanquished was no God at all. But yet, though God was not God, as the head of the dung worm turns, so his spirit turned blindly, gropingly, hopelessly loyal, towards that good, that holy, that merciful - which though not God, though vanquished - was still the last dear love of a vanquished and tortured man." . . . Robert Aske hangs in chains still, but (as Hilda Prescott's novel portrays it) a discovery has been made as he falls from level to level of despair and desire 'For now, yet with no greater fissure between then and now, and as a man's eyes are aware where no star was of the first star of night, now he was aware of One, vanquished God, Saviour who could as little save others as himself. But now, beside him and beyond, was nothing - and he was silence and light.'

Blessed martyrs of the Carthusians, pray for us!

After the first three Carthusian priors were executed on May 4, 1535, the next three leaders in line, Humphrey Middlemore, William Exmew and Sebastian Newdigate, were executed on June 19 that same year and these two monks were taken from London to the Charterhouse of St. Michael in Hull.

In the wake of the Pilgrimage of Grace, Rochester and Walworth were tried in York by Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk and found guilty of treason.

The Catholic Encyclopedia offers this detail about Blessed John Rochester:

Priest and martyr, born probably at Terling, Essex, England, about 1498; died at York, 11 May, 1537. He was the third son of John Rochester, of Terling, and Grisold, daughter of Walter Writtle, of Bobbingworth. He joined the Carthusians, was a choir monk of the Charterhouse in London, and strenuously opposed the new doctrine of the royal supremacy. He was arrested and sent a prisoner to the Carthusian convent at Hull. From there he was removed to York, where he was hung in chains. With him there suffered one James Walworth (?Wannert; Walwerke), Carthusian priest and martyr, concerning whom little or nothing is known. He may have been the "Jacobus Walwerke" who signed the Oath of Succession of 1534. John Rochester was beatified in 1888 by Leo XIII.

It must have been an agonizing death--hanging until death by exposure and dehydration--left like their brother Carthusians in Newgate Prison in London. When Rowan Williams, who resigned last year as Archbishop of Canterbury, remembered the Carthusian martyrs at the Charterhouse in London in 2010, he quoted H.F.M. Prescott's The Man on a Donkey and her description of Robert Aske's sufferings while hanging in chains, dying slowly by hunger, thirst, and exposure:

And towards the end of that extraordinary novel, we watch and listen to Robert Aske, the leader of the Pilgrimage of Grace, in his last anguished moments, hanging in chains from the Keep of the Castle in York: "God did not now nor would in any furthest future prevail. Once he had come and died. If he came again, again he would die, and again and so forever, by his own will, rendered powerless against the free and evil wills of men. Then Aske met the full assault of darkness without reprieve of hoped for light, for God ultimately vanquished was no God at all. But yet, though God was not God, as the head of the dung worm turns, so his spirit turned blindly, gropingly, hopelessly loyal, towards that good, that holy, that merciful - which though not God, though vanquished - was still the last dear love of a vanquished and tortured man." . . . Robert Aske hangs in chains still, but (as Hilda Prescott's novel portrays it) a discovery has been made as he falls from level to level of despair and desire 'For now, yet with no greater fissure between then and now, and as a man's eyes are aware where no star was of the first star of night, now he was aware of One, vanquished God, Saviour who could as little save others as himself. But now, beside him and beyond, was nothing - and he was silence and light.'

Blessed martyrs of the Carthusians, pray for us!

Published on May 10, 2013 23:00

Ci-Devants of the Russian Revolution: "Former People"

I realize this question will sound naive, but why do revolutionary movements have to be so cruel? After the former ruling class is overthrown and defeated, must it also be eradicated through oppression, violence, cruelty, degradation, etc? Can't the members of the former ruling class just be exiled? Those are the questions I kept asking as I read Douglas Smith's Former People: The Final Days of the Russian Aristocracy.

I realize this question will sound naive, but why do revolutionary movements have to be so cruel? After the former ruling class is overthrown and defeated, must it also be eradicated through oppression, violence, cruelty, degradation, etc? Can't the members of the former ruling class just be exiled? Those are the questions I kept asking as I read Douglas Smith's Former People: The Final Days of the Russian Aristocracy.As the book's blurb proclaims:

Epic in scope, precise in detail, and heart-breaking in its human drama, Former People is the first book to recount the history of the aristocracy caught up in the maelstrom of the Bolshevik Revolution and the creation of Stalin’s Russia. Filled with chilling tales of looted palaces and burning estates, of desperate flights in the night from marauding peasants and Red Army soldiers, of imprisonment, exile, and execution, it is the story of how a centuries’-old elite, famous for its glittering wealth, its service to the Tsar and Empire, and its promotion of the arts and culture, was dispossessed and destroyed along with the rest of old Russia.

Yet Former People is also a story of survival and accommodation, of how many of the tsarist ruling class—so-called “former people” and “class enemies”—overcame the psychological wounds inflicted by the loss of their world and decades of repression as they struggled to find a place for themselves and their families in the new, hostile order of the Soviet Union. Chronicling the fate of two great aristocratic families—the Sheremetevs and the Golitsyns—it reveals how even in the darkest depths of the terror, daily life went on.

Told with sensitivity and nuance by acclaimed historian Douglas Smith, Former People is the dramatic portrait of two of Russia’s most powerful aristocratic families, and a sweeping account of their homeland in violent transition.

Even though Douglas Smith is focused on the fate of the aristocracy, he also describes the injustices meted out to the peasants (the former serfs) before AND after the Russian Revolution and the Civil War, especially under Stalin's Five Year Plans. As he notes, the great developments in infrastructure were all paid for by the crushing burden of taxation on the rural peasant and of course built by the slave labor of both peasant and former aristocrat. I thought this was a magnificent history, although I admit that I was sometimes confused about which generation of one of the two families he was writing about (but that's partly my fault)--it's like Tudor England, except the names are Vladimir, Pavel, Yelena, and Smith does provide a list of main characters, family trees, maps, and two sections of photographs of memebers of both families before and after the Revolution. Fascinating; makes me want to explore the fates of the ci-devants of the French Revolution!

(Note: I checked this book out from the public library)

Published on May 10, 2013 22:30

May 9, 2013

Newman at Grandpont House in Oxford

I met with a rep from Scepter Publishers a couple of weeks ago and he gave me a copy of a book of essays published by Grandpont House in Oxford (England). John Powers asked me to read and review it. The essays were published after a series of presentations on John Henry Newman leading up to his beatification by Pope Benedict XVI in September 2010: Grandpont Papers 2: The Legacy of John Henry Newman: Essays for the Beatification.

Before I write more about the volume, let me introduce you to Grandpont House and give some more background on the presentations:

According to its website--source of the photo above--"Grandpont House is a late-Georgian building constructed over a branch of the Thames, overlooking Christ Church Meadows in central Oxford. Since 1959 it has acted as a venue for academic, cultural, outreach and religious activities for students and others. Like many other such university centres throughout the world, its establishment was inspired by St Josemaría Escrivá, the founder of Opus Dei."

The centre just completed a series of lectures on C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien during Hilary term and Trinity term, which included presentations by Walter Hooper and Stratford Caldecott--"To mark the anniversaries of Lewis and Tolkien – fifty and forty years ago respectively – six seminars will take place at Grandpont House with a view to exploring different aspects of the two scholar-writers. These seminars are not primarily intended for English literature specialists, but aim to engage a general public who are interested in a whole range of topics from ecology to political systems, story-telling to film, philosophy to theology. Each speaker will talk for around 45 minutes, followed by discussion and dialogue—and if something of the convivial atmosphere of the Inklings is rekindled, so much the better." I hope I can get a review copy of those lectures too!

The seminars adapted for the Grandpont Papers took place in May, June, and July of 2010, and this bulletin from Opus Dei gives us details about the speakers and their topics:

In the months leading up to the beatification of John Henry Newman (held in Birmingham, on September 19), Grandpont House university residence organized a cycle of seminars on the writings of the English cardinal. The sessions were directed to the university population of Oxford who wanted to learn more about Newman’s thought.

The first seminar, entitled “Newman and the Laity,” was held on May 22. Msgr. Richard Stork spoke about Newman’s vision of the role of the laity in the Church and in society. Professor Paul Shrimpton then discussed Newman’s ideas on the formation of the laity. He put special emphasis on approach taken at the “Catholic University” that Newman founded in 1854, and at the “Oratory School,” also founded by Newman in 1859.

The sessions on Saturday, June 19, centered on “Newman and Humanism.” Rev. James Pereiro spoke about reason and faith in the Cardinal’s thought and the influence of Aristotle’s ethics. Professor Shrimpton looked at Newman’s vision for the university. Following the thought of the new Blessed, he said that the university should be aimed not a imparting a specific body of knowledge, but rather at the development of a balanced and mature human personality.

The last of the seminars, on “Newman and Conscience,” took place on Saturday, July 17. The first speaker, Fr. Peter Bristow, said that one of Newman’s principal contributions to religious thought was the emphasis placed on the role of conscience in Christian life. This is a recurrent theme in his works and letters, especially in his well-known “Letter to the Duke of Norfolk.” The concluding session was given by the spokesman for Newman’s beatification, Jack Valero, who talked about “Newman and Communication.” Valero highlighted the influence of Newman’s writings on the young Joseph Ratzinger, and on the German student Sophie Scholl and other members of the “White Rose” student movement, some of whom lost their life in opposing Nazism.

Those are three great Newmanian topics: the Laity, Humanism (reason and education), and Conscience! The volume concludes with a reprint of Pope Benedict XVI's Homily at the Beatification of John Henry Newman in September 2010. The other contents are:

Introduction by James Mirabel, Director of Grandpont House

Newman's Idea of the Laity by Monsignor Richard Stork

Newman and the Formation of the Laity by Dr. Paul Shrimpton

"Lead Kindly Light": Reason and Faith by Father James Pereiro

Newman's Pastoral Idea of A University by Dr. Paul Shrimpton

Newman's Teaching on Conscience by Father Peter Bristow

Communicating Newman in the Media by Jack Valero

I'm familiar with the content of most of these essays, of course; Monsignor Stork creatively uses three of Newman's marks of true development to survey Newman's passion and concern for the formation of a laity "who know their religion, who enter into it, who know just where they stand, who know what they hold and what they do not, who know their creed so well that they can give an account of it, who know so much of history that they can defend it. . . . an intelligent, well-instructed laity". I particularly appreciated Professor Paul Shrimpton's analysis of Newman's Idea of of A University because of the focus in his first essay on how Newman wanted the Irish University and the Oratory School to help form the laity for their proper roles in society. Shrimpton addresses Newman's efforts to establish a community of learning and formation; his balance of the instruction and formation students would receive--lectures and tutoring; instruction and counselling; order and recreation--Newman had a definite vision. Unfortunately, the bishops in Ireland began to see the need for a seminary, not a college, and Newman's idea of a university was never completely implemented.

Thinking of Newman as an Aristotelian was a bit of a stunner, but Father James Periero also references Bishop Butler's Analogies, which was more familiar to me. Newman's teaching on conscience is very familiar to me, and Father Bristow really brings out that both the Popes and Newman knew what conscience really meant. Newman had to defend true conscience against even Gladstone's misunderstanding of Pope Pius IX's anathema against "so-called freedom of conscience." That form of freedom of conscience, not the classic Catholic sense, was mere self-will. The final essay just demonstrates how hard it is to portray a Victorian saint in the modern media--Mr. Valero covers several "controversies" in the mix of stories about Newman from his sexuality to his teaching on conscience.

This is a very successful volume of essays, delivered in the place on earth Newman loved the best, where he hoped to be like snapdragon, forever growing on the walls--and in a way he is, now more than ever.

To get your own copy, please check with the Grandpont website on the Library tab--again, I hope Grandpont Papers 3 or 4 is the collection of essays on Lewis and Tolkien. (Images from the website used by permission.)

Published on May 09, 2013 22:30

May 8, 2013

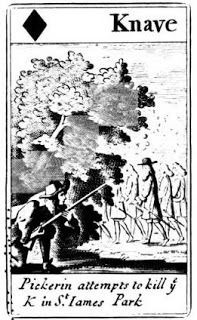

A Benedictine Popish Plot Victim: Blessed Thomas Pickering

Blessed Thomas Pickering was a Benedictine lay brother and martyr caught up in Titus Oates' duplicitous plot; a member of an old Westmoreland family, b. c. 1621; executed at Tyburn, 9 May, 1679. He was sent to the Benedictine monastery of St. Gregory at Douai, where he took vows as a lay brother in 1660. In 1665 he was sent to London, where, as steward or procurator to the little community of Benedictines who served Queen Catherine of Braganza's chapel royal, he became known personally to the queen and Charles II; and when in 1675, urged by the parliament, Charles issued a proclamation ordering the Benedictines to leave England within a fixed time, Pickering was allowed to remain, probably on the ground that he was not a priest.

Blessed Thomas Pickering was a Benedictine lay brother and martyr caught up in Titus Oates' duplicitous plot; a member of an old Westmoreland family, b. c. 1621; executed at Tyburn, 9 May, 1679. He was sent to the Benedictine monastery of St. Gregory at Douai, where he took vows as a lay brother in 1660. In 1665 he was sent to London, where, as steward or procurator to the little community of Benedictines who served Queen Catherine of Braganza's chapel royal, he became known personally to the queen and Charles II; and when in 1675, urged by the parliament, Charles issued a proclamation ordering the Benedictines to leave England within a fixed time, Pickering was allowed to remain, probably on the ground that he was not a priest. In 1678 came the pretended revelations of Titus Oates, and Pickering was accused of conspiring to murder the king. No evidence except Oates's word was produced and Pickering's innocence was so obvious that the queen publicly announced her belief in him, but the jury found him guilty, and with two others he was condemned to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. The king was divided between the wish to save the innocent men and fear of the popular clamour, which loudly demanded the death of Oates's victims, and twice within a month the three prisoners were ordered for execution and then reprieved. At length Charles remitted the execution of the other two, hoping that this would satisfy the people and save Pickering from his fate. The contrary took place, however, and 26 April, 1679, the House of Commons petitioned for Pickering's execution. Charles yielded and the long-deferred sentence was carried out on the ninth of May. A small piece of cloth stained with his blood is preserved among the relics at Downside Abbey.

The British Museum has a page dedicated to the deck of the Popish/Oates Plot playing cards, one of which depicted Brother Thomas Pickering's fictitious attempt on Charles II's life--and so does the V&A, providing this background:

Object Type

These playing cards are engravings. The images were made by cutting lines into the surface of a flat piece of metal, inking the plate and then transferring the ink held in the lines onto a sheet of paper. Francis Barlow's original drawings for the engravings are in the British Museum, London.

Subject

The Popish Plot was a fictitious Catholic conspiracy to kill Charles II that the Reverend Titus Oates claimed to have uncovered in 1678.The pictures on these cards tell the story of the plot and show the dire penalties meted out to alleged Roman Catholic enemies of the state. Sets of playing cards depicting historical events were very popular in the last quarter of the 17th century. There are other political packs from the time of the Popish Plot depicting 'All the Popish Plots' and the Rye House Plot, a conspiracy to assassinate Charles II and his brother, James, Duke of York.

Historical Context

There was great fear in Britain at the time of Catholic intrigue and a very real apprehension that on the death of Charles his Roman Catholic brother, James, would be placed on the throne. Prints were used to fuel public anxiety, and playing cards were another ideal means of spreading political propaganda at a low cost. Many packs were designed and engraved by leading artists of the day.

Published on May 08, 2013 23:00

Greenblatt, Renaissance Self-Fashioning and The Swerve

I read this passage of R.R. Reno's

Imprimis

article with great interest:

From the end of the Civil War until the 1960s, the wealthiest, best educated, and most powerful Americans remained largely loyal to Christianity. That’s changed. There were warning signs. William F. Buckley, Jr. chronicled how Yale in the early ’50s could no longer support even the bland religiosity of liberal Protestantism. Today, Yale and other elite institutions can be relied upon to provide anti-Christian propaganda. Stephen Pinker and Stephen Greenblatt at Harvard publish books that show how Christianity pretty much ruins everything, as Christopher Hitchens put it so bluntly. The major presses publish book after book by scholars like Elaine Pagels at Princeton, who argues that Christianity is for the most part an invention of power hungry bishops who suppressed the genuine diversity and spiritual richness of early followers of Jesus.

One can dispute the accuracy of the books, articles, and lectures of these and other authors. This is necessary, but unlikely to be effective. Experts savaged Greenblatt’s book on Lucretius, The Swerve, but it won the National Book Award for non-fiction. That’s not an accident. Greenblatt and others at elite universities are serving an important ideological purpose by using their academic authority to discredit Christianity, whose adherents are obstacles not only to abortion and gay rights, but to medical research unrestricted by moral concerns about the use of fetal tissue, to new reproductive technologies, to doctor-assisted suicide, and in general to liquefying traditional moral limits so that they can be reconstructed according to the desires of the Nones. Books by these elite academics reassure the Nones and their fellow travelers that they are not opposed to anything good or even respectable, but rather to historic forms of oppression, ignorance, and prejudice.

I noted Greenblatt's The Swerve when it was reviewed in the

Wall Street Journal

a couple of year ago and I see that Father Robert Barron noted his work too, partially because Father Barron had read Greenblatt's Will in the World. When I was in graduate school I read the professor's Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare and it was rather influential on my reading of Shakespeare's plays. The University of Chicago Press reissued the book in 2005:

I noted Greenblatt's The Swerve when it was reviewed in the

Wall Street Journal

a couple of year ago and I see that Father Robert Barron noted his work too, partially because Father Barron had read Greenblatt's Will in the World. When I was in graduate school I read the professor's Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare and it was rather influential on my reading of Shakespeare's plays. The University of Chicago Press reissued the book in 2005:

Renaissance Self-Fashioning is a study of sixteenth-century life and literature that spawned a new era of scholarly inquiry. Stephen Greenblatt examines the structure of selfhood as evidenced in major literary figures of the English Renaissance—More, Tyndale, Wyatt, Spenser, Marlowe, and Shakespeare—and finds that in the early modern period new questions surrounding the nature of identity heavily influenced the literature of the era. Now a classic text in literary studies, Renaissance Self-Fashioning continues to be of interest to students of the Renaissance, English literature, and the new historicist tradition, and this new edition includes a preface by the author on the book's creation and influence.

Although The Swerve won the National Book Award, I certainly hope it does not have the same influence in academia--as Reno notes, it should not, because it is not accurate history or effective interpretation, but it just might because it fits a certain pattern and need. Reviews by Father Barron, Jim Hinch in the Los Angeles Review of Books, and Professor John Monfasani in Reviews in History make its inaccuracies and errors clear. Just to cite Father Barron's response to Greenblatt's incorrect view of the Middle Ages:

I will give just a few examples of the egregious caricature of medieval Christianity that he feels compelled to present. Whereas Lucretius, Poggio, and their modern intellectual successors were marked by a restless curiosity and an adventurous desire to explore the physical universe, Catholics, Greenblatt maintains, were dogmatic, repressive, exclusively other-worldly. As evidence for this claim, he cites the medieval conviction, cultivated especially in the monasteries, that “curiositas” is a sin. Well, it might have helped if he had searched out what medieval Christians meant by that term. He would have discovered that “curiositas” names, not intellectual curiosity, but what we might characterize as gossip or minding other people’s business, seeking to know that which you have no business knowing. In point of fact, the virtue that answers the vice of “curiositas” is “studiositas” (studiousness), the serious pursuit of knowledge. As anyone even mildly familiar with medieval Christianity knows, this virtue was exemplified by some of the greatest spirits that western civilization has produced. St. Albert the Great assiduously studied Aristotelianism, which was the leading science of his time and which was concerned, above all, with searching out the causes of things; St. Thomas Aquinas’s soaring intellectualism is on vivid display on every page of his voluminous work, which runs the gamut from God and the angels to planets, plants, human societies, economics, politics, animals, etc. Bonaventure, Duns Scotus, William of Occam, Alexander of Hales, Henry of Ghent, Roger Bacon—to name just some of the most prominent figures—pursued scientific, practical and metaphysical questions with an intensity and, yes, curiosity rarely rivaled. I readily grant that an intellectual paradigm shift occurred in the 16th century, but to claim that the sciences emerged out of rank and uncurious superstition is simply a calumny.

A second feature of Greenblatt’s caricature is that medieval Christianity was dualistic, morose, deeply opposed to the pleasures of the body, and masochistic in its asceticism. As evidence he brings forward the many accounts of self-flagellation and use of the “discipline” that took place in medieval monasteries and among penitential societies. No one can deny that such practices were a feature of medieval religious life, but to take them as somehow paradigmatic of the medieval attitude toward the body is simply ridiculous. Nowhere in the literature of the world do we see more boisterous and even bawdy celebrations of the body, sensual pleasure and sexuality than in Dante’s “Divine Comedy,” Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales” and Boccaccio’s “Decameron;” and even a casual glance at the figures in the colored glass windows of Chartres Cathedral or the Sainte Chapelle reveals an extraordinary celebration of the energy and color of ordinary life. That the dominant Christian attitude in the Middle Ages was a life-denying asceticism is quite absurd.

Despite Greenblatt’s assertions, the Catholic Middle Ages did not require Lucretius’s “De rerum natura” to learn the importance of either intellectual curiosity or the joys of this life. And in point of fact, the cultural world of modernity that emerged through the exertions of Descartes, Pascal, Galileo, Newton, Jefferson and company actually owed a great deal, intellectually and artistically, to the medieval period. The story of modernity’s rise is much more complex and finally much more interesting than the one told by Stephen Greenblatt, and it is altogether possible to celebrate the legitimate achievements of modern culture without knocking down a straw-man version of Catholicism.

Regine Pernoud would agree!

From the end of the Civil War until the 1960s, the wealthiest, best educated, and most powerful Americans remained largely loyal to Christianity. That’s changed. There were warning signs. William F. Buckley, Jr. chronicled how Yale in the early ’50s could no longer support even the bland religiosity of liberal Protestantism. Today, Yale and other elite institutions can be relied upon to provide anti-Christian propaganda. Stephen Pinker and Stephen Greenblatt at Harvard publish books that show how Christianity pretty much ruins everything, as Christopher Hitchens put it so bluntly. The major presses publish book after book by scholars like Elaine Pagels at Princeton, who argues that Christianity is for the most part an invention of power hungry bishops who suppressed the genuine diversity and spiritual richness of early followers of Jesus.

One can dispute the accuracy of the books, articles, and lectures of these and other authors. This is necessary, but unlikely to be effective. Experts savaged Greenblatt’s book on Lucretius, The Swerve, but it won the National Book Award for non-fiction. That’s not an accident. Greenblatt and others at elite universities are serving an important ideological purpose by using their academic authority to discredit Christianity, whose adherents are obstacles not only to abortion and gay rights, but to medical research unrestricted by moral concerns about the use of fetal tissue, to new reproductive technologies, to doctor-assisted suicide, and in general to liquefying traditional moral limits so that they can be reconstructed according to the desires of the Nones. Books by these elite academics reassure the Nones and their fellow travelers that they are not opposed to anything good or even respectable, but rather to historic forms of oppression, ignorance, and prejudice.

I noted Greenblatt's The Swerve when it was reviewed in the

Wall Street Journal

a couple of year ago and I see that Father Robert Barron noted his work too, partially because Father Barron had read Greenblatt's Will in the World. When I was in graduate school I read the professor's Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare and it was rather influential on my reading of Shakespeare's plays. The University of Chicago Press reissued the book in 2005:

I noted Greenblatt's The Swerve when it was reviewed in the

Wall Street Journal

a couple of year ago and I see that Father Robert Barron noted his work too, partially because Father Barron had read Greenblatt's Will in the World. When I was in graduate school I read the professor's Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare and it was rather influential on my reading of Shakespeare's plays. The University of Chicago Press reissued the book in 2005:Renaissance Self-Fashioning is a study of sixteenth-century life and literature that spawned a new era of scholarly inquiry. Stephen Greenblatt examines the structure of selfhood as evidenced in major literary figures of the English Renaissance—More, Tyndale, Wyatt, Spenser, Marlowe, and Shakespeare—and finds that in the early modern period new questions surrounding the nature of identity heavily influenced the literature of the era. Now a classic text in literary studies, Renaissance Self-Fashioning continues to be of interest to students of the Renaissance, English literature, and the new historicist tradition, and this new edition includes a preface by the author on the book's creation and influence.

Although The Swerve won the National Book Award, I certainly hope it does not have the same influence in academia--as Reno notes, it should not, because it is not accurate history or effective interpretation, but it just might because it fits a certain pattern and need. Reviews by Father Barron, Jim Hinch in the Los Angeles Review of Books, and Professor John Monfasani in Reviews in History make its inaccuracies and errors clear. Just to cite Father Barron's response to Greenblatt's incorrect view of the Middle Ages:

I will give just a few examples of the egregious caricature of medieval Christianity that he feels compelled to present. Whereas Lucretius, Poggio, and their modern intellectual successors were marked by a restless curiosity and an adventurous desire to explore the physical universe, Catholics, Greenblatt maintains, were dogmatic, repressive, exclusively other-worldly. As evidence for this claim, he cites the medieval conviction, cultivated especially in the monasteries, that “curiositas” is a sin. Well, it might have helped if he had searched out what medieval Christians meant by that term. He would have discovered that “curiositas” names, not intellectual curiosity, but what we might characterize as gossip or minding other people’s business, seeking to know that which you have no business knowing. In point of fact, the virtue that answers the vice of “curiositas” is “studiositas” (studiousness), the serious pursuit of knowledge. As anyone even mildly familiar with medieval Christianity knows, this virtue was exemplified by some of the greatest spirits that western civilization has produced. St. Albert the Great assiduously studied Aristotelianism, which was the leading science of his time and which was concerned, above all, with searching out the causes of things; St. Thomas Aquinas’s soaring intellectualism is on vivid display on every page of his voluminous work, which runs the gamut from God and the angels to planets, plants, human societies, economics, politics, animals, etc. Bonaventure, Duns Scotus, William of Occam, Alexander of Hales, Henry of Ghent, Roger Bacon—to name just some of the most prominent figures—pursued scientific, practical and metaphysical questions with an intensity and, yes, curiosity rarely rivaled. I readily grant that an intellectual paradigm shift occurred in the 16th century, but to claim that the sciences emerged out of rank and uncurious superstition is simply a calumny.

A second feature of Greenblatt’s caricature is that medieval Christianity was dualistic, morose, deeply opposed to the pleasures of the body, and masochistic in its asceticism. As evidence he brings forward the many accounts of self-flagellation and use of the “discipline” that took place in medieval monasteries and among penitential societies. No one can deny that such practices were a feature of medieval religious life, but to take them as somehow paradigmatic of the medieval attitude toward the body is simply ridiculous. Nowhere in the literature of the world do we see more boisterous and even bawdy celebrations of the body, sensual pleasure and sexuality than in Dante’s “Divine Comedy,” Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales” and Boccaccio’s “Decameron;” and even a casual glance at the figures in the colored glass windows of Chartres Cathedral or the Sainte Chapelle reveals an extraordinary celebration of the energy and color of ordinary life. That the dominant Christian attitude in the Middle Ages was a life-denying asceticism is quite absurd.

Despite Greenblatt’s assertions, the Catholic Middle Ages did not require Lucretius’s “De rerum natura” to learn the importance of either intellectual curiosity or the joys of this life. And in point of fact, the cultural world of modernity that emerged through the exertions of Descartes, Pascal, Galileo, Newton, Jefferson and company actually owed a great deal, intellectually and artistically, to the medieval period. The story of modernity’s rise is much more complex and finally much more interesting than the one told by Stephen Greenblatt, and it is altogether possible to celebrate the legitimate achievements of modern culture without knocking down a straw-man version of Catholicism.

Regine Pernoud would agree!

Published on May 08, 2013 22:30

May 7, 2013

John Guy on Henry VIII's FOUR Children

According to the publisher, Oxford University Press:

According to the publisher, Oxford University Press:Behind the facade of politics and pageantry at the Tudor court, there was a family drama.

Nothing drove Henry VIII, England’s wealthiest and most powerful king, more than producing a legitimate male heir and so perpetuating his dynasty. To that end, he married six wives, became the subject of the most notorious divorce case of the sixteenth century, and broke with the pope, all in an age of international competition and warfare, social unrest and growing religious intolerance and discord.

Henry fathered four living children, each by a different mother. Their interrelationships were often scarred by jealousy, mutual distrust, sibling rivalry, even hatred. Possessed of quick wits and strong wills, their characters were defined partly by the educations they received, and partly by events over which they had no control.

Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond, although recognized as the king’s son, could never forget his illegitimacy. Edward died while still in his teens, desperately plotting to exclude his half-sisters from the throne. Mary’s world was shattered by her mother’s divorce and her own unhappy marriage. Elizabeth was the most successful, but also the luckiest. Even so, she lived with the knowledge that her father had ordered her mother’s execution, was often in fear of her own life, and could never marry the one man she truly loved.

Henry’s children idolized their father, even if they differed radically over how to perpetuate his legacy. To tell their stories, John Guy returns to the archives, drawing on a vast array of contemporary records, personal letters, and first-hand accounts.

Features:

*The intriguing family drama of England's most powerful king and his battle to perpetuate the Tudor dynasty

*A tale of six marriages, adultery, execution, and the most notorious divorce case of the sixteenth century

*A skilfully woven narrative based on original documents, personal letters, eyewitness accounts, and the handwritten letters of the four children themselves

*Shows how the childhood experiences and relationships of Henry's four children shaped their later lives - and the destiny of a nation

Note the inclusion of Henry Fitzroy, the Duke of Richmond! When Alison Weir wrote her book on the children of Henry VIII, she highlighted the heirs of Henry VIII at the end of his reign (Edward, Jane Grey, Mary, and Elizabeth). John Guy explains why he included the Duke of Richmond and comments on Mary's character in this interview:

What inspired you to write The Children of Henry VIII?

I got fed up with people from tv companies or guides in stately homes trying to tell me that Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn came to visit X or Y places as a family, with baby Elizabeth in one or other of their arms. The royal children were brought up in nurseries set apart from where their parents were living, often many miles apart. The children were together only on a handful of occasions in Henry’s entire reign, and each was rarely able to spend much time with Henry or their mother. I wanted to include Henry Fitzroy, the king’s illegitimate son, since he tends to be forgotten and yet he was an important part of the story in the earlier years. I also thought it could be illuminating to relate and position each of the children more precisely to one another, and that this might improve our understanding of the period as a whole, which turned out to be the case.

What do you think is one of the most common misconceptions about Henry’s daughter, Mary Tudor?

Mary was by nature generous, especially to her friends and supporters, but could also be generous to those who opposed her – after all, she had decided not to execute Lady Jane Grey until she learned of Wyatt’s rebellion and of Jane’s father’s role in it. She tended to give people the benefit of the doubt, but when I found how much she hated Elizabeth from the beginning and how this vendetta played out in Mary’s own reign, I was rather shocked. I was also surprised to discover the scale of Mary’s intransigence over religion in Edward’s reign – even when her cousin the Emperor Charles V told her to cease making her own houses symbols of resistance to Protestantism by having mass celebrated daily and inviting passers-by to attend, she wouldn’t stop. Charles thought it was enough that she had a licence to say [attend] mass herself – to satisfy her own conscience. He was too experienced a politician to think Mary should deliberately provoke the Duke of Northumberland. And he certainly didn’t want Mary to seek exile in his own dominions. I hadn’t realized just how intransigent Mary could be – something Philip was to discover fairly quickly when he married her.

Guy means that Mary should have stopped with just having Mass celebrated for her attendance--not that Mary "said" Mass! Leanda de Lisle writes of Guy's achievement in the April 2013 issue of the Literary Review:

John Guy is that rare cross: a scholar who also writes for the popular market. It shows here, as he sketches with verve and fluency the education and beliefs, as well as, briefly, the reigns of these last Tudors. But where he excels is in illuminating the relationships between the squabbling siblings. They say if you've got lemons make lemonade, and in Guy's hands the story of The Children of Henry VIII is fresh, sparkling and sharp.

De Lisle also comments that the "squabbling siblings" were "horrid to each other, but not horrid enough"! and suggests that Mary, having failed to bear a child by Philip of Spain to bump Elizabeth from the succession, should have used one of the plots against her (the Wyatt Rebellion Guy mentions above perhaps) as a reason to have Elizabeth executed. Philip of Spain prevented that action and surely lived to regret it as Elizabeth repaid him with war in the Spanish Netherlands and pirate raids on Spanish ships.

Published on May 07, 2013 22:30