Stephanie A. Mann's Blog

October 13, 2025

Book Review: Blessed Germain Gardiner on John Frith

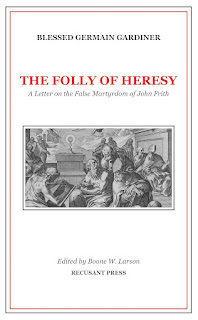

The editor of this book, Boone W. Larson, contacted me and offered to send me a copy to read and review, because I have posted in the past about the author of the letter, Blessed Germain Gardiner.Book description:

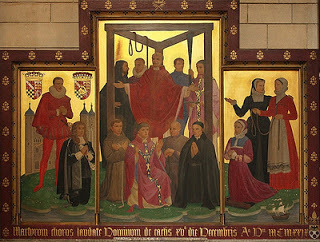

The editor of this book, Boone W. Larson, contacted me and offered to send me a copy to read and review, because I have posted in the past about the author of the letter, Blessed Germain Gardiner.Book description:The Folly of Heresy was first published in 1534. It was written in response to the trial and supposed martyrdom of John Frith, who famously denied the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. The author, Blessed Germain Gardiner—himself martyred in 1544 for denying King Henry's religious supremacy—saw in Frith's case a dangerous occasion for confusion and scandal among England's Catholics. How could they, he asked, honor a man who denied so important a doctrine of the faith? The work (which first bore a verbose title beginning with A letter of a yonge gentylman...) is not only a Scriptural-Patristic defense of the Real Presence but also a brief chronicle of Blessed Germain's personal interviews of Frith before the latter's sentencing. His account, beyond being valuable to Christians interested in Sacramental and Eucharistic theology, is in fact of extraordinary value to scholars of Henrician religious history. Despite its value, it has remained out of print since it was first issued almost five hundred years ago.

The present edition has been thoroughly revised: archaic and unintelligible spellings and grammar have been adjusted, many explanatory notes have been added, and the originally very lengthy paragraphs have been divided up for easier digestion. An introduction, textual-critical endnotes, an appendix, and indices have also been created for this edition by the editor. These editorial supplements will serve to make an otherwise inaccessible piece of English history not only approchable [sic] but enjoyable for the modern reader, whether his interest be casual or scholarly.

(No artificial intelligence was used in the creation or editing of any part of this book.)

I can also assure you that no artificial intelligence was used in this review, either!

It's great to see an independent scholar like Mr. Larson pursuing his enthusiasm in English recusant history and literature. He has already edited the Rev. Paul M. Kimball's translation of On the Just Punishment of Heretics by Alfonso de Castro, O.F.M. published by Dolorosa Press, 2024. He is preparing another important book by the Catholic exile and controversialist Thomas Stapleton, S.T.D., A Fortress of the Faith and other Works of English Recusant Theology. That will be a very important publication.

In this letter Blessed Germain Gardiner describes his attempts to reason with John Frith who would not be persuaded to renounce his heretical stance against the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. This indeed was a doctrine that Henry VIII insisted upon as Supreme Head and Governor of the Church of England, that Jesus is really present, Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity in Holy Communion; in agreement with his master at the time, Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury did too, although he would later change his mind.

Gardiner brings evidence and texts of the interpretation of Scripture and Church doctrine from the Fathers of the Church to reason with Frith, but finds him not just obstinate but changeable. He requires one standard of proof but once it's been given, changes the requirement. Gardiner notes that William Tyndale had written from the Continent advising Frith not to proceed with this line of argument--he wasn't ready for it himself.

I have to admit that--and this was true even when I read some of Saint Thomas More's apologetic/argumentative works--this kind of back-and-forth narrative of the conversations between Gardiner and Frith is not as "enjoyable" for me as promised in the book description above (from Amazon.com). Note More had exchanged arguments with John Frith too (in 1532) on the doctrine of the Real Presence. Gardiner's letter is dated August 1, 1534; More had been imprisoned in the Tower of London since April 17 of that year.

But the introduction and footnotes (often providing extended quotations from the Fathers, etc.) certainly make the work accessible. Blessed Germain Gardiner's concern for John Frith and his great efforts to reconcile him with the Eucharistic teaching of the Catholic Church certainly shine through. It's an important document and the editor is to be commended for his diligence and excellent work.

October 9, 2025

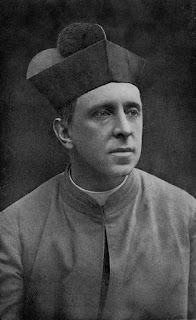

Preview: 120th Anniversary of R.H. Benson's "The King's Achievement"

The King's Achievement

, Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson's historical novel about the Dissolution of the Monasteries, was published in 1905, 120 years ago. It was one of those books I read years before I started studying the English Reformation in depth before writing my book, so I've selected it for our next Son Rise Morning Show 2025 anniversary on Monday, October 13, Columbus Day! I'll be on the air at my usual time, 7:50 a.m. Eastern/6:50 a.m. Central to discuss this anniversary and its importance. Please listen live here or catch the podcast later here.

The King's Achievement

, Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson's historical novel about the Dissolution of the Monasteries, was published in 1905, 120 years ago. It was one of those books I read years before I started studying the English Reformation in depth before writing my book, so I've selected it for our next Son Rise Morning Show 2025 anniversary on Monday, October 13, Columbus Day! I'll be on the air at my usual time, 7:50 a.m. Eastern/6:50 a.m. Central to discuss this anniversary and its importance. Please listen live here or catch the podcast later here.Like its sequel, By What Authority? , which was published in 1904, The King's Achievement is a family drama, as Benson shows the divisions caused in two families by the English Reformation during the reigns of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. One link between the two novels, for example, is the former nun, Margaret Torridon, taken from her convent by her own brother in The King's Achievement, living years later in the Catholic household of her brother-in-law and sister Mary in By What Authority?

Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson was a convert to Catholicism, the youngest son of Edward White Benson, the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1883 to 1896, and his wife, Mary. Robert's older brothers, E.F. (Edward Frederick) and A.C. (Arthur Christopher) were also authors: E.F. wrote the "Mapp and Lucia" novels and A.C. contributed to Elgar's Coronation Ode written for Edward VII in 1902 and "Land of Hope and Glory"; he was also Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge. Their sister Margaret was an Egyptologist.

After his conversion to Catholicism in 1903, Robert Hugh Benson was ordained a priest the next year.

He wrote several novels, historical and contemporary, and consulted with Don Bede Camm, another Catholic convert, who studied the English Reformation martyrs, on his historical novels. He acknowledges Dom Bede Camm's assistance in both By What Authority? and The King's Achievement.

Dom Bede Camm was inspired by the stories of the English Catholic martyrs beatified by Pope Leo XIII and published a two-volume book about them in 1904, Lives of the English Martyrs. He also helped the Benedictine Adorers of the Sacred Heart of Montmartre who had established a convent near the former site of Tyburn Tree, where many martyrs suffered.

So Camm was a good resource for Benson, but the characters and the dramas Benson created are fictional--although Thomas More, Thomas Cromwell, and other historical people appear in The King's Achievement.

Ralph, the elder son of the Torridon family, works for Thomas Cromwell and he goes to visit More at his Chelsea home in Chapter V, "Master More":

It was a wonderfully pleasant house, Ralph thought, as his wherry came up to the foot of the garden stairs that led down from the lawn to the river. It stood well back in its own grounds, divided from the river by a wall with a wicket gate in it. There was a little grove of trees on either side of it ; a flock of pigeons were wheeling about the bell-turret 'that rose into the clear blue sky, and from which came a stroke or two, announcing the approach of dinner-time as he went up the steps.

There was a figure lying on its face in the shadow by the house, as Ralph came up the path, and a small dog, that seemed to be trying to dig the head out from the hands in which it was buried, ceased his excavations and set up a shrill barking. The figure rolled over, and sat up ; the pleasant brown face was all creased with laughter ; small pieces of grass were clinging to the long hair, and Ralph, to his amazement, recognised the ex- Lord Chancellor of England.

In the plot of The King's Achievement, the crucial issue is Ralph's corruption and cruelty as he does Cromwell's will, closing the monasteries and nunneries, leaving the practice of his family's Catholic faith, and even preparing to betray even his master Cromwell when his fall comes, after having betrayed Thomas More by pretending to help him. Beatrice, a young lady from More's household, loves Ralph and trusts him until he demonstrates his cruelty to More and his own family.

It's an old fashioned novel, but Benson demonstrates great insight into Ralph's character, as he continues to serve Cromwell as he believes he is serving Henry VIII, betraying his own father, his brother Chris a monk at Lewes, and his sisters. There are some dramatic scenes of family conflict and estrangement, especially in the chapters "Father and Son" and "A Nun's Defiance", when Ralph "visits" his sister Margaret's convent to cast her out because she is underage. Benson depicts the corruption of Cromwell's visitors of the monasteries and the convents, and even as Ralph sees it himself, he accepts it as part of his duty to his master and his king.

The twist of the novel is that the great concern of Beatrice and Chris is the redemption of the souls of Ralph and his mother, who also become cold and skeptical toward both family and Church. Beatrice and Chris work together to reconcile both of them in spite of all the suffering they've endured.

The significance of this book is that, while Dom Bede Camm was studying the English martyrs and writing individual stories about their sufferings, and at the same time helping the Benedictine Adorers of the Sacred Heart of Montmartre establish their monastery shrine near Tyburn, Monsignor Benson was offering this historical novel.

Thus he could show what these divisions, disruptions, and sufferings meant to families, to the relationships between husband and wife, father and son, sister and brother, brother and brother, and even a man and a woman who were beginning to love each other perhaps toward being married. As dramatic as the martyrdoms of Thomas More, the three Carthusians, and Bishop John Fisher were--and Benson does not neglect them--readers can sympathize and even empathize with what the families suffered.

That's what fiction or drama can do. And Benson does it very well.

October 2, 2025

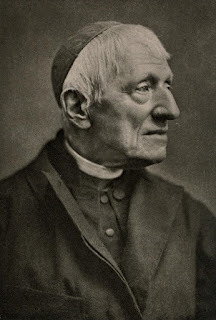

Preview: The 180th Anniversary of Newman's Conversion

Next Thursday, October 9, is Saint John Henry Newman's Feast Day, celebrated as a Feast at Masses in England and as an Obligatory Memorial here in the USA in the Anglican Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter, so naturally the anniversary of his conversion to Catholicism is the next 2025 Anniversary to celebrate on the Son Rise Morning Show!

Next Thursday, October 9, is Saint John Henry Newman's Feast Day, celebrated as a Feast at Masses in England and as an Obligatory Memorial here in the USA in the Anglican Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter, so naturally the anniversary of his conversion to Catholicism is the next 2025 Anniversary to celebrate on the Son Rise Morning Show! I'll be on the air Monday, October 6 at my usual time 7:50 a.m. Eastern/6:50 a.m. Central to discuss this anniversary and its importance. Please listen live here or catch the podcast later here.

Newman had been living in Littlemore outside of Oxford with several followers since April 19, 1842. He had preached his last sermon as an Anglican minister, "The Parting of Friends" on September 25, 1843, and had gradually been cutting his ties to Oxford--especially since he'd moved all his books to Littlemore! The impetus for his final decision to become a Roman Catholic was the coming of the Passionist priest (now Blessed) Dominic Barberi to Littlemore. One of his biographers, William Ward, demonstrates how Newman proceeded once he knew of the opportunity:

On October 3 he addressed a letter to the Provost of Oriel resigning his Fellowship. On the same day he wrote to Pusey informing him of this act, and adding, 'anything may happen to me now any day.'

On October 5 he notes in his diary, 'I kept indoors all day preparing for general confession.' [Edward] Oakeley was with W. G. Ward at Rose Hill, and dined with Newman that evening. On October 7 [Ambrose] St. John returned to Littlemore, and Newman had with him when he took the great and solemn step the one disciple to whom he habitually opened his whole mind. On this day he wrote thus to Henry Wilberforce [who hoped that Newman would delay any final action until Advent or Christmas]:

Littlemore: October 7, 1845.

'My dearest H. W.,—Father Dominic the Passionist is passing this way, on his way from Aston in Staffordshire to Belgium, where a chapter of his Order is to be held at this time. He is to come to Littlemore for the night as a guest of one of us [William Dalgairns] whom he has admitted at Aston. He does not know of my intentions, but I shall ask of him admission into the One true Fold of the Redeemer. I shall keep this back till after it is all over. . . .

'Father Dominic has had his thoughts turned to England from a youth, in a distinct and remarkable way. For thirty years he has expected to be sent to England, and about three years since was sent without any act of his own by his superior. . . . It is an accident his coming here, and I had no thoughts of applying to him till quite lately, nor should, I suppose, but for this accident.

'With all affectionate thoughts to your wife and children and to yourself,

I am, my dear H. W.,

Tuus usque ad cineres,

J. H. N.'

Newman refers to Father Barberi's visit to Littlemore as "an accident"; we might associate the word "accident" with a catastrophic event, like a car wreck or a fall, and the most common synonyms for accident reflect that (disaster, mishap, catastrophe, etc.), even though that is its secondary meaning.

Newman means "accident" as the word derives from Latin: "accident-, accidens "chance event, contingent attribute", according to Merriam-Webster. He had wanted to make his final decision after his study of Church History in the Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine was published, so that his actions would have some explanation. But since Father Barberi was coming to Littlemore, Newman prepared to be received into the Catholic Church.

Newman means "accident" as the word derives from Latin: "accident-, accidens "chance event, contingent attribute", according to Merriam-Webster. He had wanted to make his final decision after his study of Church History in the Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine was published, so that his actions would have some explanation. But since Father Barberi was coming to Littlemore, Newman prepared to be received into the Catholic Church.As Ward explains:

On the evening of October 8 Father Dominic was expected, and almost at the same time [Richard] Stanton, who had been absent for a few weeks, returned. Father Dominic was to arrive at Oxford by the coach in the afternoon. Up to the very day itself Newman did not speak to the community at Littlemore of his intention. Dalgairns and St. John were to meet the Passionist Father in Oxford. The former has left the following account of what passed:

'At that time all of us except St. John, though we did not doubt Newman would become a Catholic, were anxious and ignorant of his intentions in detail. About 3 o'clock I went to take my hat and stick and walk across the fields to the Oxford "Angel" where the coach stopped. As I was taking my stick Newman said to me in a very low and quiet {94} tone: "When you see your friend, will you tell him that I wish him to receive me into the Church of Christ?" I said: "Yes" and no more. I told Fr. Dominic as he was dismounting from the top of the coach. He said: "God be praised," and neither of us spoke again till we reached Littlemore.'

And note that others took advantage of this happy accident of Father Barberi stopping in Littlemore on his way to Belgium:

It was then pouring with rain. Newman made his general confession that night, and was afterwards quite prostrate. Ambrose St. John and Stanton helped him out of the little Oratory. On the morrow his diary has this record: 'admitted into the Catholic Church with [Frederick] Bowles and Stanton.' Next day Newman made his first communion in the Oratory at Littlemore, in which Mass was said for the first time, and Father Dominic received Mr. and Mrs. Woodmason and their two daughters. Newman walked into Oxford in the afternoon with St. John to see Mr. Newsham, the Catholic priest. On the eleventh Father Dominic left. On the same day Newman paid a visit to W. G. Ward at Rose Hill, and Charles Marriott came to see him at Littlemore [Note 9].

Thus very quietly and without parade took place the great event dreamt of for so many years—with dread at first, in hope at last.

When I visited the Newman Centre at Littlemore in 2010, our guide, one of the Sisters of the Spiritual Family the Work, showed us the letters Newman wrote to his sisters and others on October 9, 1845 telling them of this "great event" and also a stole of Blessed Dominic Barberi's in a glass case. The Littlemore Newman Centre and the Birmingham Oratory are the major shrines to Newman in England, and I'm glad I went to at least one of them, perhaps the most important because of the date of his conversion, his feast day. He died in Birmingham on April 11, 1890, Saint Clare of Assisi's feast day.

Blessed Dominic Barberi, pray for us!

Saint John Henry Newman, pray for us!

September 25, 2025

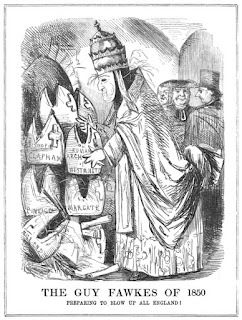

Preview: The Restoration of the Hierarchy/the Gorham Judgment/Anglican Difficulties: 1850

One hundred and seventy five years ago, three events in England now offer some context to the history of religion in England for us to consider:

One hundred and seventy five years ago, three events in England now offer some context to the history of religion in England for us to consider: 1. On September 29, 1850 Blessed Pope Pius IX restored the Catholic hierarchy in England, an act of "Papal Aggression" according to the Queen and her Parliament;

2. The Gorham Judgment on March 8, 1850 led several more Tractarians to "Cross the Tiber";

3. Oratorian Father John Henry Newman reached out to those Tractarians with his public Lectures on Difficulties Felt by Anglicans in Submitting to the Catholic Church, starting in July 1850.

So on Monday, September 29, the feast of the Archangels, we'll consider these 2025 Anniversaries in our Son Rise Morning Show series by focusing on the Gorham Judgment, which, like later decisions in the Church of England, led some on the edge of conversion to "submit" to the Catholic Church. I'll be on the air at my usual time around 7:50 a.m. Eastern/6:50 a.m. Central to discuss this anniversary and its importance. Please listen live here or catch the podcast later here.

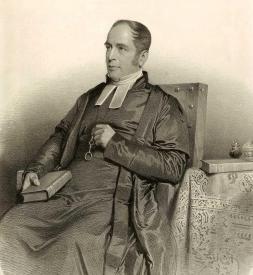

The Reverend George Cornelius Gorham (1787-1857) was appointed to a "living" (a pastoral position) at the vicarage in Bramford Speke in Exeter. The Anglican bishop of that diocese--the appointment was made by the Lord Chancellor, Charles Christopher Pepys, 1st Earl of Cottenham--Henry Phillpotts, refused to install Gorham in the living because Gorham's views on Baptism weren't orthodox according to Church of England doctrine. He did not believe in the Sacramental Grace of Baptism to be salvific but as conditional. Gorham appealed to the Anglican Bishops Court of Arches and lost on appeal. So Gorham took his cause to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, a secular authority, who overruled the Bishops Court.

To those who'd remained in the Tractarian/Oxford Movement, this was a real blow. Henry Manning, the Archdeacon particularly felt the blow. Newman's "defection" and the bishops' action against the Movement had been bad enough, but here was more proof that the Church of England was an Erastian church, under the control of the secular state which presumed to determine what the Church believed. The Privy Council, not the Court of Arches, had interpreted the Thirty-Nine Articles--this was a real crisis.

Manning and others, including William Gladstone, made an appeal to the bishops to undo this Privy Council action. When that was ignored, Manning and others--but not Gladstone--made the great decision to convert to Catholicism. Among those who joined Manning: Thomas William Allies, William Wilberforce, Jr. and his brothers Robert and Henry Wilberforce, sons of "The Great Emancipator", William Wilberforce, Sr.; John Hungerford Pollen, William Dodsworth, James Hope-Scott, and Edward Badeley.

Manning and others, including William Gladstone, made an appeal to the bishops to undo this Privy Council action. When that was ignored, Manning and others--but not Gladstone--made the great decision to convert to Catholicism. Among those who joined Manning: Thomas William Allies, William Wilberforce, Jr. and his brothers Robert and Henry Wilberforce, sons of "The Great Emancipator", William Wilberforce, Sr.; John Hungerford Pollen, William Dodsworth, James Hope-Scott, and Edward Badeley.The context of those conversions, taking place even as Queen Victoria and Parliament felt threatened by Pope Pius IX appointing Catholic bishops to organize Catholic dioceses in England, was momentous. Newman saw the opportunity to reach out to Manning and others, using arguments to answer the kind of difficulties he'd encountered along the way to his conversion, and therefore offered a lecture series in London on those Anglican Difficulties.

In the wake of the Gorham Judgment, he emphasized the Erastian nature of the Established Church. In the first lecture "On the Relation of the National Church to the Nation" he warned them:

He was warning them that the Erastian Church of England would follow the spirit of the age and the interests of the establishment and that "changes in the nation" would be the source of church teaching, not those "Truths divinely revealed, developed, and explained by men of genius in the past . . ."

I have said all this, my brethren, not in declamation, but to bring out clearly to you, why I cannot feel interest of any kind in the National Church, nor put any trust in it at all from its past history, as if it were, in however narrow a sense, a guardian of orthodoxy. It is as little bound by what it said or did formerly, as this morning's newspaper by its former numbers, except as it is bound by the Law; and while it is upheld by the Law, it will not be weakened by the subtraction of individuals, nor fortified by their continuance. Its life is an Act of Parliament. It will not be able to resist the Arian, Sabellian, or Unitarian heresies now, because Bull or Waterland resisted them a century or two before; nor on the other hand would it be unable to resist them, though its more orthodox theologians were presently to leave it. It will be able to resist them while the State gives the word; it would be unable, when the State forbids it. Elizabeth boasted that she "tuned her pulpits;" Charles forbade discussions on predestination; George on the Holy Trinity; Victoria allows differences on Holy Baptism. While the nation wishes an Establishment, it will remain, whatever individuals are for it or against it; and that which determines its existence will determine its voice. Of course {9} the presence or departure of individuals will be one out of various disturbing causes, which may delay or accelerate by a certain number of years a change in its teaching: but, after all, the change itself depends on events broader and deeper than these; it depends on changes in the nation. As the nation changes its political, so may it change its religious views; the causes which carried the Reform Bill and Free Trade may make short work with orthodoxy.

After 1850, there have been other decisions made in the Church of England that have incited Anglican pastors and laymen to become Catholic, like ordaining women as priests and bishops. Pope Saint John Paul II, with the Pastoral Provision, and Pope Benedict XVI, with the creation of the Anglican Ordinariate, acknowledged the impact of such decisions by welcoming Episcopalian and Anglican clergy to the Catholic priesthood, even if married after their conversions, if they felt the call.

Saint John Henry Newman, pray for us!Blessed Pius IX, pray for us!

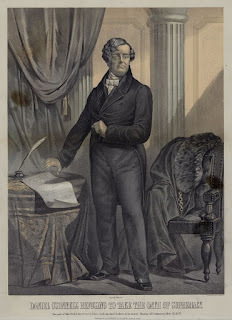

Image Credit (Public Domain): Portrait of the Reverend George Cornelius Gorham

September 21, 2025

Book Review: "Weep, Shudder, Die" by Dana Gioia

I enjoy listening to, watching, and reading about opera. When I was little my grandparents--and later my parents--had the two volume Lincoln Library of Essential Information (not sure what edition) and it contained a section with synopses of all the major operas and I nearly memorized them. The plot to Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots shocked me and then I had to read about the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre! Probably in the Funk & Wagnalls encyclopedia.

I enjoy listening to, watching, and reading about opera. When I was little my grandparents--and later my parents--had the two volume Lincoln Library of Essential Information (not sure what edition) and it contained a section with synopses of all the major operas and I nearly memorized them. The plot to Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots shocked me and then I had to read about the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre! Probably in the Funk & Wagnalls encyclopedia.I've attended eight or so operatic performances, but I've watched many more on television and listened to them on the radio (especially the Met's Saturday Matinee broadcasts!), records, compact discs, and now YouTube. So when I saw this book recommended on an OperaAmerica video, I had to read it: Weep, Shudder, Die: On Opera and Poetry, by Dana Gioia.

According to the publisher, Paul Dry Books:

Or laughed.

Weep, Shudder, Die explores opera from the perspective by which the art was originally created, as the most intense form of poetic drama. The great operas have an essential connection to poetry, song, and the primal power of the human voice. The aim of opera is irrational enchantment, the unleashing of emotions and visionary imagination.

Gioia rejects the conventional view of opera which assumes that great operas can be built on execrable texts. He insists that in opera, words matter. Operas begin as words; strong words inspire composers, weak words burden them. Ultimately, singers embody the words to give the music a human form for the audience.

Weep, Shudder, Die is a poet’s book about opera. To some, that statement will suggest writing that is airy, impressionistic, and unreliable, but a poet also brings a practical sense of how words animate opera, lend life to imaginary characters, and give human shape to music. Written from a lifelong devotion to the art, Gioia’s book is for anyone who has wept in the dark of an opera house.

I appreciated the autobiographical background of Gioia's boyhood, college days, and travels to Europe. He describes his discovery of opera, classical music, and literature, and how they set him apart from his classmates.

His encyclopedic and detailed analysis of the great librettists of the core of the standard repertoire is helpful: 24 of the 50 most performed operas have librettos written by eight poets:

Lorenzo Da PonteFelice Romani Francisco Maria Piave Salvadore CammaranoArrigo BoitoLuigi IllicaHugo von HoffmansthalRichard Wagner

Gioia also selects "stellar teams":Mozart with Da Ponte Bellini with RomaniVerdi with Piave Verdi with BoitoPuccini with IllicaStrauss with HoffmansthalWagner with Wagner (he wrote his own "poems")[Cammarano wrote the libretto for Verdi's Il Trovatore]

He also highlights Pietro Metastasio, whose librettos inspired Vivaldi, Handel, Gluck, Haydn, Mozart, and Donizetti, even after his death, especially for the opera seria style.

Although Gioia argues that opera is an incredibly collaborative art of the theatre, he focuses mostly on the composer and the librettist and even notes that he will not--except for one slip--talk about the singers who sing the words and music, even though he admits later in the book that each singer will interpret the words and music differently. He mentions singers he heard in Vienna, with Cesare Siepi, Sena Jurinac, Gundula Janowitz, and Wilma Lipp--so a long time ago. He mentions Leontyne Price, William Warfield, and others, including Leyla Gencer, but the index doesn't tell me where; she was a great bel canto soprano but did not make many commercial recordings; I think she was called "the queen of the bootlegs"! He briefly mentions the system of "fach"; on page 151 he states: "Opera exists only through the skill and artistry of singers. I didn't understand opera until I saw great singers perform it." He also does not write much about the conductors of opera. His focus is on the libretto as it inspires the composer to compose the music the conductor, the orchestra, and the singers will perform.

Chapters on individual opera librettists and composers in the USA from Menotti and Floyd to Bernstein and Sondheim are discerning and fascinating and then in last chapters he gets into his own experience writing opera librettos and how much it differed from his work as a poet, expressing himself, not the characters in the operas, etc. Crucially, he also discusses the relationship between opera in the USA and our musical theater--what American works are operas and which are musical theater pieces? Porgy and Bess? Sweeney Todd? A Little Night Music? Candide?

Gioia also discusses the state of opera in the USA: there's a dwindling market but it's passionate and devoted. The OperaAmerica video I watched (in which this book was recommended) highlighted the great quality of the singers prepared and trained in the USA and their limited opportunities: the interviewee said he was encouraging singers to go the European houses (Germany, Austria, and Switzerland) where they can become "house singers" and practice and perform their repertoire. That is certainly going to affect the opportunities for librettists and composers in the USA. It's a fascinating book.

I found Leyla Gencer! Page 99 not page 211 as it's listed in the index.

September 18, 2025

Preview: Henriëtte Bosmans and "Lead, Kindly Light" in 1945

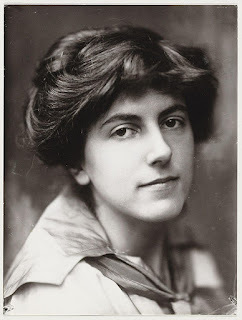

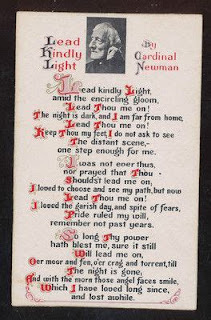

I had never heard of Henriëtte Bosmans until earlier this month! And I certainly did not know that she had composed a work for soprano and either piano or orchestra based on Saint John Henry Newman's poem "Lead, Kindly Light"--and that it had premiered in 1945, thus 80 years ago. With that date, however, I knew this was a topic for our Son Rise Morning Show 2025 Anniversary series.

I had never heard of Henriëtte Bosmans until earlier this month! And I certainly did not know that she had composed a work for soprano and either piano or orchestra based on Saint John Henry Newman's poem "Lead, Kindly Light"--and that it had premiered in 1945, thus 80 years ago. With that date, however, I knew this was a topic for our Son Rise Morning Show 2025 Anniversary series. Therefore, on Monday, September 22, I'll be on the air at my usual time around 7:50 a.m. Eastern/6:50 a.m. Central to discuss this anniversary and its background. Please listen live here or catch the podcast later here.

Bosmans was born in Amsterdam on December 6, 1895 (130 years ago); her father was Catholic and her mother was Jewish--and her father died when she was six months old. It was a musical family as her father had been the principal cellist of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and her mother, Sarah Benedicts, was a piano teacher at the Amsterdam Conservatory.

Henriëtte studied piano with her mother and other instructors at the Conservatory and taught piano herself; then she began her concert and composing careers as this website explains:

Bosmans debuted as a concert pianist in 1915 in Utrecht. She performed throughout Europe with among others Pierre Monteux, Willem Mengelberg and Ernest Ansermet. She gave 22 concerts with the Concertgebouw Orchestra alone between 1929 and 1949. She played one of her own compositions at a concert in Geneva in 1929. In 1940, one of her compositions was performed in concert by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, with Ruth Posselt as the soloist. In 1941, Posselt again performed work by Bosmans, with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.The BBC Music Magazine recounts a terrible event in her life even as she was forbidden from publishing or performing her works because her mother Jewish and because Henriette refused to cooperate with the Nazi cultural authorities in occupied Netherlands:

One day, in a climate of constant threat, the worst happened: Sara was arrested by the Gestapo. Taken to the Westerbork transit camp, the last stop for many before they were deported and murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau and Sobibor, her fate seemed sealed.

Bosmans went to the Gestapo HQ in Amsterdam to plea for her mother’s life, apparently confronting the officers. She also turned to Willem Mengelberg, conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra, to ask his help. Astonishingly, five days after arriving at Westerbork, Sara was freed and sent back to Amsterdam.

The same article explains how she turned from composing for the piano, cello, and other stringed instruments after the end of World War II and to composing for the voice, including Newman's "Lead, Kindly Light":

Her creative spirit was rekindled by the end of the war. ‘Oppression is crushed and freedom begins,’ cries her liberation song Daar Komen de Canadezen (Here come the Canadians). She dedicated both this and Gebed (Prayer) to Jo Vincent, a famous Dutch soprano who had appeared at the Proms [in England]. In 1945, Vincent appeared in Amsterdam with the Concertgebouw and Sir Adrian Boult to sing Lead, kindly light, Bosmans’s setting of a hopeful English text by Cardinal Newman.

The date of that concert was November 3, 1945, just six months after the liberation of The Netherlands on May 5 when the Germans officially surrendered at the demand of the Royal Canadian Regiment (thus the song about the Canadians coming!).

The date of that concert was November 3, 1945, just six months after the liberation of The Netherlands on May 5 when the Germans officially surrendered at the demand of the Royal Canadian Regiment (thus the song about the Canadians coming!). Unlike the hymn settings by John Bacchus Dykes (Lux Benigna), William Henry Harris (Alberta), David Evans (Bonifacio), Charles H. Purday (Sandon), or Arthur Sullivan (Lux in Tenebris), this is a work for a professional vocalist with either orchestral or piano accompaniment. The piano score is marked throughout as "Adagio sostenuto" for the keyboard and either "piu tranquillo" or "poco animato" for the soprano soloist, so it is delicate and subdued, in spite of its hopeful ending.

Henriëtte died on July 2, 1952. May she rest in the peace of that Kindly Light.

Saint John Henry, pray for us!

Image Source (Public Domain): Photograph of Henriëtte Bosmans (1917) by Jacob Merkelbach (1877-1942)

September 11, 2025

Preview: Fifteen Years Ago, Newman's Beatification

Earlier this month, King Charles III visited the Birmingham Oratory in honor of Saint John Henry Newman being named a Doctor of the Catholic Church. You might recall that as the Prince of Wales he attended Newman's canonization in 2019.

Earlier this month, King Charles III visited the Birmingham Oratory in honor of Saint John Henry Newman being named a Doctor of the Catholic Church. You might recall that as the Prince of Wales he attended Newman's canonization in 2019. Fifteen years ago this month, Pope Benedict XVI came to Scotland and England on a State Visit and beatified Newman in Cofton Park outside Birmingham. So on Monday, September 15--very appropriately, since Pope Benedict arrived in Scotland on September 16, 2010--we'll remember this anniversary on the Son Rise Morning Show, at my usual time (6:50 a.m. Central/7:50 a.m. Eastern); please listen live here or catch the podcast later here.

You can still find details about that State Visit here! Just some highlights:

Thursday, September 16, 2010: Queen Elizabeth II met Pope Benedict XVI at the airport and offered some remarks:

. . .Your Holiness, in recent times you have said that ‘religions can never become vehicles of hatred, that never by invoking the name of God can evil and violence be justified’. Today, in this country, we stand united in that conviction. We hold that freedom to worship is at the core of our tolerant and democratic society.Pope Benedict responded by remembering another anniversary, the end of World War II:

On behalf of the people of the United Kingdom I wish you a most fruitful and memorable visit.

. . . As we reflect on the sobering lessons of the atheist extremism of the twentieth century, let us never forget how the exclusion of God, religion and virtue from public life leads ultimately to a truncated vision of man and of society and thus to a "reductive vision of the person and his destiny" (Caritas in Veritate, 29).

Sixty-five years ago, Britain played an essential role in forging the post-war international consensus which favoured the establishment of the United Nations and ushered in a hitherto unknown period of peace and prosperity in Europe. . . .

He participated in a parade honoring Saint Ninian after an official visit with the Queen and Prince Philip at Holyroodhouse, and then celebrated Mass in Glasgow's Bellahouston Park, where Saint John Paul II celebrated Mass in 1982.

Friday, September 17, 2010: After leaving Scotland for England, the pope attended several events in London, met with the Archbishop of Canterbury and then spoke at Westminster Hall to politicians and other government officials, where he highlighted another great Englishman and saint:

Later that evening he prayed Evensong in Westminster Abbey with the Archbishop of Canterbury and other church dignitaries.As I speak to you in this historic setting, I think of the countless men and women down the centuries who have played their part in the momentous events that have taken place within these walls and have shaped the lives of many generations of Britons, and others besides. In particular, I recall the figure of Saint Thomas More, the great English scholar and statesman, who is admired by believers and non-believers alike for the integrity with which he followed his conscience, even at the cost of displeasing the sovereign whose “good servant” he was, because he chose to serve God first. The dilemma which faced More in those difficult times, the perennial question of the relationship between what is owed to Caesar and what is owed to God, allows me the opportunity to reflect with you briefly on the proper place of religious belief within the political process. . . .

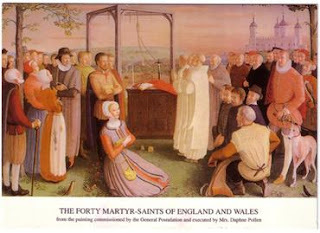

Saturday, September 18, 2010: This day was dedicated to Catholic Westminster: the Cardinal Archbishop, Mass at Westminster Cathedral, and Eucharistic Adoration that night in Hyde Park, where Pope Benedict talked about Newman and alluded to other English martyrs:

Newman’s life also teaches us that passion for the truth, intellectual honesty and genuine conversion are costly. The truth that sets us free cannot be kept to ourselves; it calls for testimony, it begs to be heard, and in the end its convincing power comes from itself and not from the human eloquence or arguments in which it may be couched. Not far from here, at Tyburn, great numbers of our brothers and sisters died for the faith; the witness of their fidelity to the end was ever more powerful than the inspired words that so many of them spoke before surrendering everything to the Lord. In our own time, the price to be paid for fidelity to the Gospel is no longer being hanged, drawn and quartered but it often involves being dismissed out of hand, ridiculed or parodied. And yet, the Church cannot withdraw from the task of proclaiming Christ and his Gospel as saving truth, the source of our ultimate happiness as individuals and as the foundation of a just and humane society.

Finally, Newman teaches us that if we have accepted the truth of Christ and committed our lives to him, there can be no separation between what we believe and the way we live our lives. Our every thought, word and action must be directed to the glory of God and the spread of his Kingdom. Newman understood this, and was the great champion of the prophetic office of the Christian laity. . . .

And finally, Sunday, September 19, 2010: The day of the Beatification Mass at Cofton Park. Pope Benedict had admired Newman since he was a young man and he certainly knew the depths of Newman's intellectual, historical, and rhetorical brilliance but he emphasized a different aspect at the end of his homily:

While it is John Henry Newman’s intellectual legacy that has understandably received most attention in the vast literature devoted to his life and work, I prefer on this occasion to conclude with a brief reflection on his life as a priest, a pastor of souls. The warmth and humanity underlying his appreciation of the pastoral ministry is beautifully expressed in another of his famous sermons: “Had Angels been your priests, my brethren, they could not have condoled with you, sympathized with you, have had compassion on you, felt tenderly for you, and made allowances for you, as we can; they could not have been your patterns and guides, and have led you on from your old selves into a new life, as they can who come from the midst of you” (“Men, not Angels: the Priests of the Gospel”, Discourses to Mixed Congregations, 3). He lived out that profoundly human vision of priestly ministry in his devoted care for the people of Birmingham during the years that he spent at the Oratory he founded, visiting the sick and the poor, comforting the bereaved, caring for those in prison. No wonder that on his death so many thousands of people lined the local streets as his body was taken to its place of burial not half a mile from here. One hundred and twenty years later, great crowds have assembled once again to rejoice in the Church’s solemn recognition of the outstanding holiness of this much-loved father of souls. What better way to express the joy of this moment than by turning to our heavenly Father in heartfelt thanksgiving, praying in the words that Blessed John Henry Newman placed on the lips of the choirs of angels in heaven:Praise to the Holiest in the height

And in the depth be praise;

In all his words most wonderful,

Most sure in all his ways!

After visiting the Birmingham Oratory and other meetings, Pope Benedict received a farewell from David Cameron the Prime Minister as this had been a State Visit:

. . . Your Holiness, your presence here has been a great honour for our country. Now you are leaving us – and I hope with strong memories. When you think of our country, think of it as one that not only cherishes faith, but one that is deeply, but quietly, compassionate. I see it in the incredible response to the floods in Pakistan. I see it in the spirit of community that drives countless good deeds done for friends and neighbours every day. And in my own life, I have seen it in the many, many kind messages that I have had as I have cradled a new daughter and said goodbye to a wonderful father. . . .

Those comments seem quite heartfelt.

Saint John Henry Newman, pray for us!

September 4, 2025

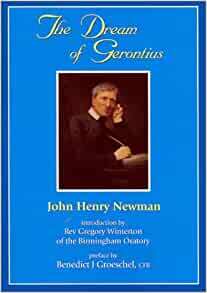

Preview: The Composition and Publication of the "Dream of the Gerontius" in 1865

Before Edward Elgar set the text of Newman's Dream of Gerontius to music in 1900, of course, Newman had written that eloquent poem about death, judgment, Heaven, and hell in 1895, 160 years ago this year.

So, since two weeks ago on the Son Rise Morning Show we featured the Elgar anniversary, this coming Monday, September 8, we'll look at the composition and publication of Saint (Doctor) John Henry Newman's poem itself in 1865. (The Son Rise Morning hosts were busy the week before at the EWTN Radio Conference in Washington, DC and took the Monday, September 1 Labor Day holiday off!) I'll be on the air at my usual time around 7:50 a.m. Eastern/6:50 a.m. Central. Please listen live here or catch the podcast later here.

Newman's other most famous poem is "The Pillar of the Cloud", better known as "Lead, Kindly Light". He wrote that poem and many others while he was travelling with his friend Hurrell Froude in Italy and the Mediterranean. He wrote those verses in the Romantic mode as defined by William Wordsworth in the Preface to Lyrical Ballads (1800): as ". . . the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity", reflecting on his experiences on that journey.

Newman wrote this poem, the longest we have of his, on 52 scraps of paper between January 17 and February 7, 1865. There was a sudden inspiration and an urge to write it--and a definite end to the inspiration. One of his biographers, Wilfrid Ward, describes its composition:

Now, after the abandonment of the Oxford scheme [to found an Oratory for Catholic students, who could at last attend Oxford] gave him leisure for it, he set down in dramatic form the vision of a Christian's death on which his imagination had been dwelling. The writing of it was a sudden inspiration, and his work was begun in January and completed in February 1865. "On the 17th of January last," he writes to Mr. Allies in October, "it came into my head to write it, I really can't tell how. And I wrote on till it was finished on small bits of paper, and I could no more write anything else by willing it than I could fly." To another correspondent [The Rev. John Telford, priest at Ryde] also, who was fascinated by the Dream, and longed to have the picture it gave still further filled in, he wrote:"You do me too much honour if you think I am to see in a dream everything that is to be seen in the subject dreamed about. I have said what I saw. Various spiritual writers see various aspects of it; and under their protection and pattern I have set down the dream as it came before the sleeper. It is not my fault if the sleeper did not dream more. Perhaps something woke him. Dreams are generally fragmentary. I have nothing more to tell."

As I wrote in an earlier post about this poem, Newman was able to turn away from controversy and difficulties to contemplate eternal truths:

Perhaps after such strain of confusion, controversy, and confrontation, it was restful to contemplate the certainties of God's justice and mercy when a man dies. No more secrecy and indirection; the soul meets Jesus, knows Him, knows himself, and looks forward to being with the Holy Trinity and the saints in Heaven after his purgation. Newman explored the Church's dogmatic teachings about death and judgement, heaven and hell in a mystical, dreamy poem, harking back to his childhood love of fantasy and wonder--his sense that life was somehow a dream--while reflecting his assent to the certainties of divine revelation and his faith in the reality of God. He also includes liturgical and devotional prayers for the dying and the death, including the Litany of the Saints and the Proficiscere prayer ("Go forth, Christian Soul") in a supremely, confidently Catholic poem.

Although though it is "a supremely, confidently Catholic poem" The Dream met with ecumenical approval--even his former defamer Charles Kingsley liked it! William Gladstone and Algernon Charles Swinburne, the decadent school poet, admired the poem's verse and power. Francis Hastings Doyle, the Professor of Poetry at the University of Oxford, gave a lecture on The Dream of Gerontius in 1868. News that General George Gordon, "Chinese Gordon", had a copy of the poem with him at Khartoum--and that he had annotated it--when he was attacked and killed in January 1885 gave the poem even greater notoriety. As Father Ian Ker of happy memory noted in his biography of Newman, "interest in the fate of Gordon of Khartoum" was so intense that William Neville transcribed Gordon's annotations into copies of The Dream of Gerontius (p. 741).

The Dream of Gerontius was then published in the May and June issues of The Month, a periodical founded in 1864 by the convert Frances Margaret Taylor (Mother Magdalen of the Sacred Heart, Poor Servants of the Mother of God). The Jesuits in England bought The Month in 1865 and Father Henry James Coleridge, another convert (great nephew of the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge), became the publisher and editor.So the 160th anniversary of this poem is worth remembering as the work continues to have its impact artistically and theologically. It may not always be, as Francis Hastings Doyle commented, the greatest artistic success, but it has perdured through the decades through its beauty and depth.

[In 2022, throughout the month of November, Matt and Anna and I went through The Dream of Gerontius in as much detail as we could in our Monday morning segments!]

Saint John Henry Newman, pray for us!

August 21, 2025

Preview: The Premiere of Elgar's "Dream of Gerontius", 1900

There's yet another new recording of Sir Edward Elgar's Dream of Gerontius (from Finland!), based on Saint John Henry Newman's epic poem--in scope if not in length--of the Four Last Things. The last recording won multiple awards this year.

There's yet another new recording of Sir Edward Elgar's Dream of Gerontius (from Finland!), based on Saint John Henry Newman's epic poem--in scope if not in length--of the Four Last Things. The last recording won multiple awards this year. And yet when it premiered in 1900 in Birmingham, things did not go well, and reviews of performances lately often include comments about "how Catholic" and esoteric the work is, qualified by praise of the music and orchestration! Nevertheless, it's an often performed and recorded choral masterpiece.

Since this year marks the 125th anniversary of Elgar composing it and of its premier in 1900, it's up next in our Son Rise Morning Show 2025 Anniversaries series on Monday, August 25. I'll be on the air around 7:50 a.m. Eastern/6:50 a.m. Central. Please listen live here or catch the podcast later here.

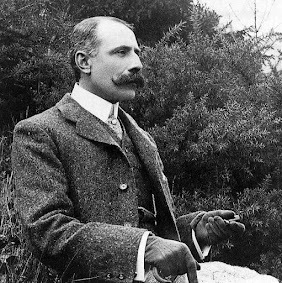

Elgar (June 2, 1857-February 23, 1934) composed this work (not really an oratorio) 60 years after Saint John Henry Newman wrote the Dream of Gerontius in 1865--so 2025 is also the 160th anniversary of the poem from which Elgar excerpted sections.

Edward Elgar's mother Ann was a convert to Catholicism while his father remained Anglican; Edward was baptized and raised Catholic. His father William disapproved--while at the same time serving as the organist at Saint George's Catholic Church in Worcester from 1846 to 1885--and became a Catholic on his deathbed! As the BBC classical magazine website explains, Elgar was coming off the great success of the Enigma Variations in 1900 when he decided to compose a great choral work based on Newman's poem for the Three Choirs Festival in Birmingham that year. He composed quickly and concluded that "This is the best of me; for the rest, I ate, and drank, and slept, loved and hated, like another: my life was as the vapour and is not; but this I saw and knew; this, if anything of mine, is worth your memory."

Unfortunately,

the first performance was plagued by mishaps. The choirmaster, Charles Swinnerton Heap, died shortly after rehearsals began and was replaced by the ageing William Stockley, who wasn’t equal to the task and who, in any case, didn’t try to mask his distaste for the subject matter. Hans Richter, the conductor, only received the full score one day before orchestra rehearsals began and only one of the soloists was in good voice on the day. Although the press generally conceded that a decent work had been presented, it was widely accepted that the first performance had been a disaster.Fortunately,

The German conductor Julius Buths was in the Birmingham audience and recognised that Gerontius merited a decent hearing. It was Buths’s performances in Düsseldorf in 1901 and ’02 that alerted the British musical world to the fact that Elgar had indeed produced something extraordinary. The occasions were a huge success, Elgar was fêted as a hero and was presented with two enormous laurel wreaths which he and Alice somehow managed to lug back to Malvern. Richard Strauss wrote ‘I raise my glass to the welfare and success of the first English progressivist, Meister Elgar’. If the Catholic Elgar hadn’t arrived before, the Anglican establishment had no choice but to concede that he certainly had done so now.

In spite of reviews like this (or in deviance of them!), Elgar's Dream of Gerontius is one of my favorite works. I've three recordings on CD and the DVD record of a great performance at Canterbury Cathedral by Dame Janet Baker as the Angel and Peter Pears as Gerontius/the Soul, conducted by Sir Adrian Boult.

When my mother was in her final days, I was called by the Hospice nurse to come early one more morning and I took my 1962 Roman Missal with the prayers for the dying. When I prayed the priest's prayer "PROFICISCERE, anima Christiana, de hoc mundo!"--

Go forth upon thy journey, Christian soul!Go from this world! Go, in the name of God

The omnipotent Father, who created thee!

Go, in the name of Jesus Christ, our Lord,

Son of the living God, who bled for thee!

Go, in the name of the Holy Spirit, who

Hath been poured out on thee! Go, in the name

Of Angels and Archangels; in the name

Of Thrones and Dominations; in the name

Of Princedoms and of Powers; and in the name

Of Cherubim and Seraphim, go forth! . . .

--I heard Elgar's music in my "mind's ear"!

What's sad about Elgar's own life is that the initial failure of the Dream of Gerontius had lasting effects on his faith in God and religious devotion, as this website explains:

What's sad about Elgar's own life is that the initial failure of the Dream of Gerontius had lasting effects on his faith in God and religious devotion, as this website explains:

Ironically, it was the early failure of The Dream of Gerontius itself that led him to make the oft-quoted remark “I always knew God was against art…”, continuing “I have allowed my heart to open once – it is now shut against every religious feeling…”, this shortly before beginning work on The Apostles and The Kingdom, two oratorios viewed from an admittedly more neutral religious perspective.

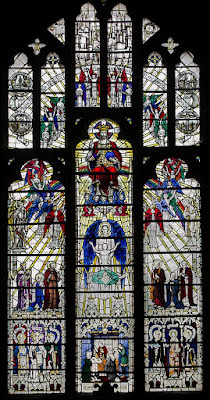

As he grew older, his belief gradually withered. Although on his deathbed he is reported to have reaffirmed his commitment to the Roman Catholic faith and, while unconscious, received the last rites, he had not attended a church service for many a year. He claimed to have no belief in a life after death and to have taken exception to the dogma of the Catholic liturgy.That same website offers a snarky comment about Elgar's memorial stained glass window being in the Anglican Worcester Cathedral (image use under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license: "The Elgar Window by A. K. Nicholson, 1935, based on the Dream of Gerontius. The window shows Gerontius ascending to the Heavenly City, surrounded by figures from the Bible [?]*."

I could be snarky too and point out that Worcester Cathedral was a Catholic church from 680 to 1535 (and 1555-1559 during Mary I's reign)! *There are Catholic saints depicted there, including two canonized bishops of Worcester, Oswald and Wulfstan, Saint Cecilia, Saint Gregory the Great, Saint Francis of Assisi, Saint Peter (with the keys!) the Blessed Virgin Mary, Saint Joseph, and King David with his harp, etc.

The memorial plaque to Elgar in the cathedral includes the words from the prayers he may or may not have heard on his deathbed: "PROFICISCERE, anima Christiana, de hoc mundo!"

Edward Elgar and his wife Alice are buried in the cemetery of St. Wulstan’s Catholic Church at Little Malvern in Worcestershire, where a 75th anniversary memorial Mass was offered for him in 2009.

May Edward and Alice Elgar rest in peace!

Saint John Henry Newman, pray for us!

Image Credit (Public Domain): English composer Edward Elgar, likely in the early 1900s.

August 14, 2025

Preview: 250th Anniversary of "The Liberator" Daniel O'Connell's Birth

The man who became known as "The Liberator" in Ireland from anti-Catholic legislation and political tests was born on August 6, 1775, 250 years ago.

Daniel O'Connell was born in County Kerry on the southwest coast of Ireland to a Catholic family who had maintained their property because they arranged for Protestant trustees. That's just one of the freedoms--owning private property--that O'Connell worked to secure for Irish Catholics during his life. We'll celebrate this 250th anniversary on Monday, August 18 on the Son Rise Morning Show! I'll be on the air around 7:50 a.m. Eastern/6:50 a.m. Central. Please listen live here or catch the podcast later here.

Because he was Catholic and could not attend college in Ireland in his youth, O'Connell studied at the Jesuit College at Saint-Omer--and fled the bloody violence of the French Revolution in 1793! He studied law in England, practiced law in Ireland; while he appreciated the greater freedom afforded Catholics in the "Roman Catholic Relief" Acts of 1791 and 1793, he sought even greater freedom for Catholics in Ireland--including their right to vote for Catholics to represent them in the House of Commons in Parliament. Marked by the violence of the French Revolution and with the lessons of other failed attempts to gain freedom for Catholics in Ireland, where they were the vast majority, O'Connell proceeded to organize and to test the system by standing for Parliament in Ireland and being elected in 1828--shaming the British, reform-minded Government out of its Anti-Catholic (doctrine) exclusions and Oaths.

Because he was Catholic and could not attend college in Ireland in his youth, O'Connell studied at the Jesuit College at Saint-Omer--and fled the bloody violence of the French Revolution in 1793! He studied law in England, practiced law in Ireland; while he appreciated the greater freedom afforded Catholics in the "Roman Catholic Relief" Acts of 1791 and 1793, he sought even greater freedom for Catholics in Ireland--including their right to vote for Catholics to represent them in the House of Commons in Parliament. Marked by the violence of the French Revolution and with the lessons of other failed attempts to gain freedom for Catholics in Ireland, where they were the vast majority, O'Connell proceeded to organize and to test the system by standing for Parliament in Ireland and being elected in 1828--shaming the British, reform-minded Government out of its Anti-Catholic (doctrine) exclusions and Oaths. Thus the passage of the 1829 Catholic Emancipation Act, removing most of those exclusions and eventually the anti-Catholic Oath O'Connell would have had to take before being seated in Parliament: to deny the Real Presence of Jesus in the Eucharist (Transubstantiation), prayer to the Virgin Mary and the Saints, and participation in the Catholic Mass and reception of Holy Communion there--and to abjure political fealty to the Pope. He still had to declare he "was a true Christian". [Catholic nobility would also be able to take their seats in the House of Lords.]

Of course there were some compromises made in the process of this Parliamentary action in 1829: only men who owned property worth ten pounds per annum could vote (raised from two pounds) and Catholics still had to tithe 10% of their land's value to the Anglican Church of Ireland (taxation without ecclesial representation!). These difficulties were eventually addressed, and O'Connell had to run for the seat he had just won again in the 1829 Clare County special election (perhaps some hoped he'd lose without those poorer voters who had supported him in 1828--but he ran unopposed!)

The National Library of Ireland comments that he "changed the face of Irish history":

A brilliant orator, political organiser and advocate for non-violent reform, O’Connell led the campaign for Catholic Emancipation and founded the Repeal Association to challenge the Act of Union. Known as ‘The Liberator’, he was the first Catholic to win a seat in the British Parliament in more than 100 years. O’Connell helped forge a model of peaceful mass mobilisation that influenced movements far beyond Ireland.

As we mark the 250th anniversary of his birth this year, the National Library of Ireland (NLI) invites the public to rediscover the life and legacy of one of the nation’s most consequential political figures through our unparalleled Daniel O’Connell collections. . . .

On August 6, there was an official Irish Government ceremony at Derrynane House, Caherdaniel, Co. Kerry, O'Connell's birthplace--and you may watch it on RTE (and hear a little Irish spoken!). The speakers emphasize O'Connell's influence beyond Ireland in the cause of freedom and progress, but I hope they don't really include the right to abortion in that progress, but they might. In 2023, there were more than 10,000 babies murdered in the womb, through legal abortions.

There was a wide range of events and programs to honor the anniversary of O'Connell's birth, including a statue outside the Irish Parliament:

The Bank of Ireland is gifting a statue of Daniel O’Connell to the Houses of the Oireachtas. The statue which is currently located in their College Green Branch will be moved to the Leinster House building for unveiling later this year.

Mention of a statue reminded me that G.K. Chesterton called for a statue of Daniel O'Connell in London back in 1929, and in 2014 Francis Campbell, writing for The Catholic Herald, echoed Chesterton's idea when a statue of Mahatma Gandhi was announced, dedicated the next year in Parliament Square.

In "The Early Bird in History" Chesterton had written about how the Catholic Church rehabilitated Saint Joan of Arc long before the English (or even G.B. Shaw) had considered it and then noted:

And I for one hope to see the day when this measure of magnanimity [regarding late-developing English sympathy for Saint Joan of Arc] shall be filled up where it has been most wanting; and some such payment made for the deepest debt of all. I should like to see the day when the English put up a statue of [Robert] Emmett beside the statue of Washington; and I wish that in the Centenary of Emancipation [1829-1929] there were likely to be as much fuss in London about the figure of Daniel O'Connell as there was about that of Abraham Lincoln.

Robert Emmet, like George Washington, had rebelled and fought against the English, leading the Rising of 1803 but, unlike Washington, lost and therefore was hanged, drawn, and quartered on September 20 in Dublin that year. Why does one rebel gets a statue and the other doesn't? Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in the Union and Mahatma Gandhi worked to end Untouchability in India, etc. Why do two liberators of the enslaved and oppressed get statues and another doesn't?

There's still no statue of either Irish hero in London.

Saint Patrick, pray for us!

Image Source (Public Domain): Lithograph of Daniel O'Connell refusing to take the oath of supremacy. Caption: "One part of this Oath I know to be false; and another I believe to be untrue. House of Commons, May 20, 1829."