Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 267

July 10, 2013

King James II and President Barack Obama in the WSJ

This article in

The Wall Street Journal

caught my idea because it mentioned King James II. Michael McConnell writes:

This article in

The Wall Street Journal

caught my idea because it mentioned King James II. Michael McConnell writes:Article II, Section 3, of the Constitution states that the president "shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed." This is a duty, not a discretionary power. While the president does have substantial discretion about how to enforce a law, he has no discretion about whether to do so.

This matter—the limits of executive power—has deep historical roots. During the period of royal absolutism, English monarchs asserted a right to dispense with parliamentary statutes they disliked. King James II's use of the prerogative was a key grievance that lead to the Glorious Revolution of 1688. The very first provision of the English Bill of Rights of 1689—the most important precursor to the U.S. Constitution—declared that "the pretended power of suspending of laws, or the execution of laws, by regal authority, without consent of parliament, is illegal."

To make sure that American presidents could not resurrect a similar prerogative, the Framers of the Constitution made the faithful enforcement of the law a constitutional duty.

Now, Michael McConnell does not examine which laws James II refused to enforce, and I don't think that James II was the first to avail himself of that opportunity. The laws James II refused to enforce and which he and the "Repealers" were in fact working to change were the laws against Catholics, Protestant dissenters and others in England. I am still slowly reading Scott Sowerby's Making Toleration, but I see that the Diocese of Shrewsbury in England appreciates Sowerby's work:

An account of a speech given in Chester by Britain’s last Catholic king has been published for the first time in a book examining the struggle for religious liberty in England in the late 17th century.

The book by the respected American historian Professor Scott Sowerby includes a diary extract of an account of possibly the most important speech by King James II on the subject of religious freedom.

For the first time in 350 years, it provides evidence that James viewed religious liberty as a fundamental human right, placing him years ahead of his time.

In his speech in the Cheshire city in August 1687, the King likened a person’s religious convictions to the colour of his or her skin and vowed to grant toleration to all of his subjects.

His speech was part of a tour of England to drum up support for his Declaration for Liberty of Conscience, a manifesto for the legal toleration of non-conformists – Protestant dissenters, Catholics and Quakers – persecuted under the penal laws and Test Acts, under which James himself had to temporarily surrender any claims to hold political office.

He and his friend, William Penn, the Quaker who gave his name to Pennsylvania, argued that the confiscation of goods and money from Catholics and dissenters constituted a violation of their right to hold private property that was guaranteed by the Magna Carta.

They advocated a new law that would guarantee liberty of conscience and were hoping to construct a “tolerationist” Parliament the following year. James also released thousands of non-Anglican dissenters from prison in a general pardon and suspended the penal legislation.

So there's a wide moral difference between what King James II did in refusing to enact penal laws against Catholics AND Protestant dissenters and the Quakers and whatever President Barack Obama has done in delaying a portion of the "Affordable Care Act"--which is a subject far beyond the purpose of this blog and which I will not discuss--and it's unfortunate that McConnell misrepresents or under-represents James II.

Part of Sowerby's argument is that the "Glorious Revolution" was a conservative backlash against James II's really epoch-making effort to advocate for true religious liberty and conscience rights. So the laws that James II refused to enforce were penal laws against Catholics, Protestant dissenters, and Quakers--not really such an injustice after all. The "Glorious Revolution" which was an invasion of England by the Dutch, invited by the "Immortal Seven", was no great advance for human liberty against the attacks of absolutism, but a rejection of a real advance in human liberty: religious freedom and conscience rights!

Published on July 10, 2013 23:00

July 9, 2013

Lady Jane Grey, the Nine Days Queen

Four days after young King Edward VI died on July 6, 1553, Lady Jane Dudley began her reign as Queen of England. (I call her by her married name because her in-law relationship to the Duke of Northumberland, John Dudley, was essential to her succession to the throne in the eyes of Edward VI). The delay in the accession came about because her father-in-law Dudley waited to announce the king's death while preparing for a smooth transition. Because of her Protestantism, because she was executed by "Bloody" Mary, because John Foxe promoted her cause, she became known as a martyr and victim of Catholic oppression in England--part of the Black Legend of Catholic cruelty. She has also been thought a victim of family abuse and manipulation, an unwilling pawn of Northumberland.

Two studies recently have questioned this view: Eric Ives' Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery and Leanda de Lisle's The Sisters Who Would Be Queen: Mary, Katherine, and Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Tragedy. Both books are all about the issue of the succession in the Tudor Dynasty, either from Edward VI to Jane or Mary, or from Elizabeth I to Mary, Queen of Scots, or the surviving Grey sisters, Mary and Catherine--so in neither book is Jane the main subject, really. I reviewed de Lisle's book, but have not read Ives' book, but as this reviewer notes, Ives' study is a "provocative and revisionist account" that takes nothing for granted:

Two studies recently have questioned this view: Eric Ives' Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery and Leanda de Lisle's The Sisters Who Would Be Queen: Mary, Katherine, and Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Tragedy. Both books are all about the issue of the succession in the Tudor Dynasty, either from Edward VI to Jane or Mary, or from Elizabeth I to Mary, Queen of Scots, or the surviving Grey sisters, Mary and Catherine--so in neither book is Jane the main subject, really. I reviewed de Lisle's book, but have not read Ives' book, but as this reviewer notes, Ives' study is a "provocative and revisionist account" that takes nothing for granted:Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery is not a biography. Rather, it is a book about a dynastic and political crisis. The ‘Tudor Mystery’ that Eric Ives has set out to solve is how the ‘legitimate’ Queen Jane, who commanded considerable political support, was overthrown in favour of the illegitimate Mary Tudor in ‘a wholly unexpected political coup’ (1). Viewing Jane’s rule from this angle produces a provocative and revisionist account of the summer of 1553. This alone would make Ives’ book an important piece of scholarship; that he wields an extensive array of archival evidence and provides the most detailed account to date of the succession crisis of 1553 makes this a book that no Tudor historian can ignore. . . .

Despite the title, Jane Grey is not the focus of Ives’s book, though Ives does discuss Jane’s education, family and religion at some length. His Jane is not the tragic figure who appealed to so many Victorians, but a ‘bluestocking’ and committed evangelical used as a political pawn by her indifferent parents. Jane married Guidlford Dudley reluctantly and was initially disinclined to take the throne: indeed, she was apparently surprised to discover that she was queen. Yet once on the throne she wielded power with a firmer hand than her earlier reluctance might suggest, adamantly blocking plans to invest her husband as king. Jane and her supporters had the advantage. They controlled the court, the state administration and the Tower, and Northumberland oversaw orders to the lord lieutenants in the counties to uphold Jane’s rule, whereas Mary possessed significantly inferior resources and was mistaken in her belief that her cousin, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V would come to her aid. Immediately after Edward’s death, few would have bet on Mary. Yet within thirteen days she had amassed considerable support, had been proclaimed Queen in London with the backing of the Privy Council, and Northumberland, who had led an army out of London in order to suppress Mary’s uprising, had surrendered. All of these developments need to be examined anew if Jane, not Mary, was rightfully queen.

Published on July 09, 2013 23:00

The Carmelites of Compiegne on "The Good Fight"

I'll be on EWTN Radio this Saturday, July 13, talking with Barbara McGuigan on "The Good Fight": our topic will be the Carmelite Martyrs of Compiegne, in anticipation of their memorial on July 17. If you have any questions or comments about these great martyrs of the French Revolution, please call in at 1-877-573-7825.

I'll be on EWTN Radio this Saturday, July 13, talking with Barbara McGuigan on "The Good Fight": our topic will be the Carmelite Martyrs of Compiegne, in anticipation of their memorial on July 17. If you have any questions or comments about these great martyrs of the French Revolution, please call in at 1-877-573-7825."The Good Fight" airs from 1:00 to 3:00 p.m. Central time; 2:00 to 4:00 p.m. Eastern, etc--and you may listen live online at EWTN here.

Barbara and I will examine the heroic story of these martyrs, the campaign of de-Christianization in France during the French Revolution, and apply the lessons of their sacrifice to our lives today. We'll also look at the connection between the Carmelites' story and the English Reformation!

Published on July 09, 2013 22:30

July 8, 2013

Art under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm at The Tate in London

This show will not open at the Tate Britain until October 2, but the BBC and The Guardian have already started to cover it:

Art under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm will be the first exhibition exploring the history of physical attacks on art in Britain from the 16th century to the present day. Iconoclasmdescribes the deliberate destruction of icons, symbols or monuments for religious, political or aesthetic motives. The exhibition will examine the movements and causes which have led to assaults on art through objects, paintings, sculpture and archival material from 2 October.

Highlights include Thomas Johnson’s Interior of Canterbury Cathedral 1657– the only painting documenting Puritan iconoclasm in England – exhibited for the first time alongside stained glass removed from the windows of the cathedral. Edward Burne-Jones’ Sibylla Delphica 1898 and Allen Jones’ Chair 1969, damaged by suffragettes and feminists will be on display, as well as evidence of statues destroyed in Ireland during the 20th century. The show will consider artists such as Gustav Metzger, Yoko Ono and Jake and Dinos Chapman, who have used destruction as a creative force.

Religious iconoclasm of the 16th and 17th centuries will be explored with statues of Christ decapitated during the Dissolution, smashed stained glass from Rievaulx Abbey, fragments of the great rood screen at Winchester Cathedral and a book of hours from British Library, defaced by state-sanctioned religious reformers. These will be accompanied by vivid accounts of the destructive actions of Puritan iconoclasts.

As The Guardian story notes,

"It obviously is a difficult subject," said the director of Tate Britain , Penelope Curtis. "The decision was to treat it seriously rather than shy away from it, to try and explore it properly so that people understood its history more fully."

Curtis, whose idea it was, said it was something Tate Britain ought to do because the museum's collection "covers nearly 500 years but not quite". In fact, the show starts in the 1540s, with Henry VIII and the dissolution of the monasteries, which led to the state-sanctioned destruction of so much art. The events were particular to Britain and changed our visual history forever, said Curtis.

Getting examples of 500-year-old destroyed art is clearly difficult, and one of the star exhibits will be a statue of Jesus that remained hidden for centuries.

Statue of the Dead Christ (1500-1520), which belongs in the collection of the Worshipful Company of Mercers [which is "the Premier Livery Company of the City of London"] in London's Square Mile, was discovered buried beneath the chapel floor in 1954 during the post war clearup. As a result of Protestant attacks it is missing a crown of thorns, arms and lower legs but is otherwise in remarkable condition, the theory being that someone concealed it to protect it from further damage.

It is a powerful statue, with Jesus graphically portrayed with rigor mortis-stiffened limbs, mouth open and carved blood oozing from wounds – it was that power that the Protestant reformers found so dangerous. The Mercers' loan is the first to any exhibition since it was discovered.

This site, focused on the life and times of Margery Kempe, quotes a long description of an iconclastic attack on a parish church in Norfolk:

In the chancel, as it is called, we took up twenty brazen superstitious inscriptions, Ora pro nobis &c.; broke twelve apostles, carved in wood, an cherubims and a lamb with a cross, and took up four superstitious inscriptions in brass, in the north chancel, Jesu filii Dei miserere mei, &c. broke in pieces the rails, and broke down twenty-two popish pictures of angels and saints. We did deface the font and a cross on the font; and took up the brass inscription there, with Cujus animae propitietus Deus, and "pray for the soul," &c. in English. We took up thirteen superstitious brasses. Ordered Moses with his rod and Aaron with his mitre, to be taken down. Ordered eighteen angels off the roof, and cherubims to be taken down and nineteen pictures in the window. The organ I brake and we brake seven popish pictures in the chancel window, - one of Christ, another of St. Andrew, another of St. James, &c. We ordered the steps [before the altar] to be leveled by the parson of the town; and brake the popish inscription, My flesh is meat indeed, and my blood is drink indeed. I gave orders to break the carved work, which I have seen done. There were six superstitious pictures, one crucifix, and the Virgin Mary with the infant Jesus in her arms, and Christ lying in a manger, and the three kings coming to Christ with presents, and three bishops with their mitres and crosier staffs, and eighteen Jesuses written in capital letters, which we gave orders to do out. A picture of St. George, and many others which I remember not, with divers pictures in the windows, which we could not reach, neither would they help us to raise ladders; so we left a warrant with the constable to do it in fourteen days. We brake down a pot of holy water, St. Andrew with his cross, and St. Catherine with her wheel; and we took down the cover of the font, and the four evangelists, and a triangle for the Trinity, a superstitious picture of St. Peter and his keys, an eagle, and a lion with wings. In Bacon's aisle was a friar with a shaven crown, praying to God in these words, Miserere mei Deus, - which we brake down. We brake a holy water font in the chancel. We rent to pieces a hood and surplices. In the chancel was Peter pictured in the windows, with his heels upwards, and John the Baptist, and twenty more superstitious pictures, which we brake: and IHS the Jesuit's badge in the chancel window. In Bacon's aisle, twelve superstition of angels and crosses and a holy water font, and brasses with superstitious inscriptions. And in the cross alley we took up brazen figures and inscriptions, Ora pro nobis. We brake down a cross on the steeple, and three stone crosses in the chancel, and a stone cross in the porch. Quoted by M. Aston, England's Iconoclasts. Vol. 1 Laws Against Images, Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1988: 78-9. (Journal of William Dowsing, p. 244)

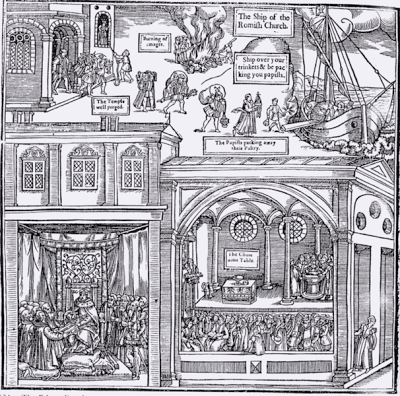

More about Puritan iconoclasm here. Illustration from Wikipedia: Woodcut image from the 1563 edition of Foxe's Book of Martyrs, depicting iconoclasm. In the top part of the image "papists" are packing away their "paltry," while the church is purged of idols. Bottom parts depict clerics receiving the Bible from Queen Elizabeth I, and a communion table.

Published on July 08, 2013 22:30

July 7, 2013

The Christian Century in the WSJ: Decline of the Mainline

Barton Swaim, Communications Manager at the South Carolina Policy Council, book reviewer for The Wall Street Journal and The Weekly Standard, and author of Scottish Men of Letters and the New Public Sphere, 1802-1834, published by Bucknell University Press, reviews a new study of the magazine The Christian Century for The Wall Street Journal:

The Christian Century (its original title was the Christian Oracle) was founded in 1884 as a magazine of the Disciples of Christ, one of the seven principal mainline denominations. Charles Clayton Morrison, a young minister with intellectual ambitions, purchased it in 1908, soon made it nondenominational and edited it for 39 years. Morrison had strong opinions, and he knew how to acquire and use what Ms. Coffman, following the French social theorist Pierre Bourdieu, calls "cultural capital"—assets in the marketplace of political and social influence. . . .

The Century's target audience was, as Morrison put it with characteristic pomposity, "those who might be said to represent the Christian intelligentsia of all the churches." The Christian Century, he thought, would influence the "best minds" in the church, and they in turn would influence the laity.

According to Oxford University Press:

The Christian Century and the Rise of the Protestant Mainline offers the first full-length, critical study of The Christian Century, widely regarded as the most influential religious magazine in America for most of the twentieth century and hailed by Time as "Protestantism's most vigorous voice."

Elesha Coffman narrates the previously untold story of the magazine, exploring its chronic financial struggles, evolving editorial positions, and often fractious relations among writers, editors, and readers, as well as the central role it played in the rise of mainline Protestantism. Coffman situates this narrative within larger trends in American religion and society. Under the editorship of Charles Clayton Morrison from 1908-1947, the magazine spoke out about many of the most pressing social and political issues of the time, from child labor and women's suffrage to war, racism, and the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It published such luminaries as Jane Addams, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Martin Luther King Jr. and jostled with the Nation, the New Republic, and Commonweal, as it sought to enlarge its readership and solidify its position as the voice of liberal Protestantism. But by the 1950s, internal strife between liberals and neo-orthodox and the rising challenge of Billy Graham's evangelicalism would shatter the illusion of Protestant consensus. The coalition of highly educated, theologically and politically liberal Protestants associated with the magazine made a strong case for their own status as shepherds of the American soul but failed to attract a popular following that matched their intellectual and cultural clout.

Elegantly written and persuasively argued, The Christian Century and the Rise of the Protestant Mainline takes readers inside one of the most important religious magazines of the modern era.

Swaim partly agrees with that last statement, but he thinks that Coffman needed to go further in her analysis:

Ms. Coffman's research has uncovered a great deal of material about the rise and decline of mainline Protestantism, and she tells its story well. In my view, however, she treats her subject a little too delicately, with a young scholar's reluctance to draw broad conclusions. So allow me. The decline of liberal Protestantism that began in the 1950s had at least three sources.

Read his analysis of those three sources here. One of them is the wide gap between what the congregants believe about the Holy Bible and Salvation and what the mainline/mainstream Chrisitan intelligentsia posit--think of John Shelby Spong or even the current leader of the Episcopalian Church in the U.S.A., Katharine Jefferts Schori. Sometimes I think of the campaign Blessed John Henry Newman would lead against their teachings, a la his controversy with Renn Dickson Hampden.

Published on July 07, 2013 22:30

July 6, 2013

The Fifth Anniversary of Summorum Pontificum

Picture Credit: by the Priestly Fraternity of Saint Peter, available from http://fssp.org On Saturday July 7, 2007 Pope Benedict XVI issued an Apostolic Letter on the celebration of the Roman Rite according to the Missal of 1962--so today is the fifth anniversary of Summorum Pontificum. As you might recall, papal documents are usually refered to by the first words of the official Latin text (and therefore the English text may not begin with the same words, translated). The first words of this apostolic letter refer to the "supreme pontiffs" and the first several paragraphs are a history lesson:

Up to our own times, it has been the constant concern of supreme pontiffs to ensure that the Church of Christ offers a worthy ritual to the Divine Majesty, 'to the praise and glory of His name,' and 'to the benefit of all His Holy Church.'

Since time immemorial it has been necessary - as it is also for the future - to maintain the principle according to which 'each particular Church must concur with the universal Church, not only as regards the doctrine of the faith and the sacramental signs, but also as regards the usages universally accepted by uninterrupted apostolic tradition, which must be observed not only to avoid errors but also to transmit the integrity of the faith, because the Church's law of prayer corresponds to her law of faith.'

Among the pontiffs who showed that requisite concern, particularly outstanding is the name of St. Gregory the Great, who made every effort to ensure that the new peoples of Europe received both the Catholic faith and the treasures of worship and culture that had been accumulated by the Romans in preceding centuries. He commanded that the form of the sacred liturgy as celebrated in Rome (concerning both the Sacrifice of Mass and the Divine Office) be conserved. He took great concern to ensure the dissemination of monks and nuns who, following the Rule of St. Benedict, together with the announcement of the Gospel illustrated with their lives the wise provision of their Rule that 'nothing should be placed before the work of God.' In this way the sacred liturgy, celebrated according to the Roman use, enriched not only the faith and piety but also the culture of many peoples. It is known, in fact, that the Latin liturgy of the Church in its various forms, in each century of the Christian era, has been a spur to the spiritual life of many saints, has reinforced many peoples in the virtue of religion and fecundated their piety.

Many other Roman pontiffs, in the course of the centuries, showed particular solicitude in ensuring that the sacred liturgy accomplished this task more effectively. Outstanding among them is St. Pius V who, sustained by great pastoral zeal and following the exhortations of the Council of Trent, renewed the entire liturgy of the Church, oversaw the publication of liturgical books amended and 'renewed in accordance with the norms of the Fathers,' and provided them for the use of the Latin Church.

One of the liturgical books of the Roman rite is the Roman Missal, which developed in the city of Rome and, with the passing of the centuries, little by little took forms very similar to that it has had in recent times.

It was towards this same goal that succeeding Roman Pontiffs directed their energies during the subsequent centuries in order to ensure that the rites and liturgical books were brought up to date and when necessary clarified. From the beginning of this century they undertook a more general reform.' Thus our predecessors Clement VIII, Urban VIII, St. Pius X, Benedict XV, Pius XII and Blessed John XXIII all played a part.

Text from EWTN. EWTN also provides a link to the letter then Pope Benedict XVI addressed to his fellow bishops throughtout the world:

With great trust and hope, I am consigning to you as Pastors the text of a new Apostolic Letter "Motu Proprio data" on the use of the Roman liturgy prior to the reform of 1970. The document is the fruit of much reflection, numerous consultations and prayer.

News reports and judgments made without sufficient information have created no little confusion. There have been very divergent reactions ranging from joyful acceptance to harsh opposition, about a plan whose contents were in reality unknown.

This document was most directly opposed on account of two fears, which I would like to address somewhat more closely in this letter.

In the first place, there is the fear that the document detracts from the authority of the Second Vatican Council, one of whose essential decisions – the liturgical reform – is being called into question. This fear is unfounded. In this regard, it must first be said that the Missal published by Paul VI and then republished in two subsequent editions by John Paul II, obviously is and continues to be the normal Form – the Forma ordinaria – of the Eucharistic Liturgy. The last version of the Missale Romanum prior to the Council, which was published with the authority of Pope John XXIII in 1962 and used during the Council, will now be able to be used as a Forma extraordinaria of the liturgical celebration. It is not appropriate to speak of these two versions of the Roman Missal as if they were "two Rites". Rather, it is a matter of a twofold use of one and the same rite.

As for the use of the 1962 Missal as a Forma extraordinaria of the liturgy of the Mass, I would like to draw attention to the fact that this Missal was never juridically abrogated and, consequently, in principle, was always permitted. At the time of the introduction of the new Missal, it did not seem necessary to issue specific norms for the possible use of the earlier Missal. Probably it was thought that it would be a matter of a few individual cases which would be resolved, case by case, on the local level. Afterwards, however, it soon became apparent that a good number of people remained strongly attached to this usage of the Roman Rite, which had been familiar to them from childhood. This was especially the case in countries where the liturgical movement had provided many people with a notable liturgical formation and a deep, personal familiarity with the earlier Form of the liturgical celebration. We all know that, in the movement led by Archbishop Lefebvre, fidelity to the old Missal became an external mark of identity; the reasons for the break which arose over this, however, were at a deeper level. Many people who clearly accepted the binding character of the Second Vatican Council, and were faithful to the Pope and the Bishops, nonetheless also desired to recover the form of the sacred liturgy that was dear to them. This occurred above all because in many places celebrations were not faithful to the prescriptions of the new Missal, but the latter actually was understood as authorizing or even requiring creativity, which frequently led to deformations of the liturgy which were hard to bear. I am speaking from experience, since I too lived through that period with all its hopes and its confusion. And I have seen how arbitrary deformations of the liturgy caused deep pain to individuals totally rooted in the faith of the Church.

(Westminster Cathedral Choir: Te Deum by Victoria)

My husband and I have been attending Sunday Mass in the Extraordinary Form of the Latin Liturgy of the Roman Rite at St. Anthony of Padua Catholic Church for the past five years, and now seek out the "EFLR" whenever we travel. One of the priests who offers the Low Mass one Sunday a month at St. Anthony's has now begun to offer a Low Mass one evening a month at Blessed Sacrament Parish. I have found the celebration of Mass according to the Extraordinary Form to be very conducive to deeper devotion to the Holy Eucharist and the Real Presence of Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament because of its reverence and the holy silence observed throughout the Mass. And as I have continued to study the English Reformation, and particularly to investigate the music of the recusant composers like William Byrd and Peter Philips, I have felt great unity across the ages with those missionary priests celebrating the Mass of the Council of Trent, upon which the Mass of Blessed John XIII in the Roman Missal of 1962 is based. Te Deum Laudamus for the fifth anniversary of Summorum Pontificum!

Published on July 06, 2013 22:30

July 5, 2013

St. Thomas More

I have written and posted and spoken often about St. Thomas More--he's been mentioned 54 times at least on this blog, for example. For the past two years, especially during the two Fortnight for Freedom events, his name and his cause have been mentioned often. He is praised as a martyr for religious freedom, for conscience, for marriage, for Catholic unity; he is noted as a model of Christian humanism, as a father and educator, writer, lawyer, politician, and friend--and he is sometimes a figure of controversy too, over the issues of heresy and trials for heresy during his term as Chancellor and sometimes for the language he used in the print arguments against William Tyndale. But as G.K. Chesterton said in 1929, "[Saint] Thomas More is important today, but he is not as important now as he will be in one hundred years from today"--isn't hard to believe that in 1929, he was "just" Blessed Thomas More? As I noted last year, Chesterton was correct; he was just off a couple of decades. Instead of more words about St. Thomas More, here are some words from St. Thomas More--a prayer he wrote and prayed in the Tower of London, awaiting trial and execution:

I have written and posted and spoken often about St. Thomas More--he's been mentioned 54 times at least on this blog, for example. For the past two years, especially during the two Fortnight for Freedom events, his name and his cause have been mentioned often. He is praised as a martyr for religious freedom, for conscience, for marriage, for Catholic unity; he is noted as a model of Christian humanism, as a father and educator, writer, lawyer, politician, and friend--and he is sometimes a figure of controversy too, over the issues of heresy and trials for heresy during his term as Chancellor and sometimes for the language he used in the print arguments against William Tyndale. But as G.K. Chesterton said in 1929, "[Saint] Thomas More is important today, but he is not as important now as he will be in one hundred years from today"--isn't hard to believe that in 1929, he was "just" Blessed Thomas More? As I noted last year, Chesterton was correct; he was just off a couple of decades. Instead of more words about St. Thomas More, here are some words from St. Thomas More--a prayer he wrote and prayed in the Tower of London, awaiting trial and execution:Give me the grace, Good Lord

~To set the world at naught.

~To set the mind firmly on You and not to hang upon the words of men's mouths.

~To be content to be solitary. Not to long for worldly pleasures. Little by little utterly to cast off the world and rid my mind of all its business.

~Not to long to hear of earthly things, but that the hearing of worldly fancies may be displeasing to me.

~Gladly to be thinking of God, piteously to call for His help. To lean into the comfort of God. Busily to labor to love Him.

~To know my own vileness and wretchedness. To humble myself under the mighty hand of God. To bewail my sins and, for the purging of them, patiently to suffer adversity.

~Gladly to bear my purgatory here. To be joyful in tribulations. To walk the narrow way that leads to life.

~To have the last thing in remembrance. To have ever before my eyes my death that is ever at hand. To make death no stranger to me. To foresee and consider the everlasting fire of Hell. To pray for pardon before the judge comes.

~To have continually in mind the passion that Christ suffered for me. For His benefits unceasingly to give Him thanks.

~To buy the time again that I have lost. To abstain from vain conversations. To shun foolish mirth and gladness. To cut off unnecessary recreations.

~Of worldly substance, friends, liberty, life and all, to set the loss at naught, for the winning of Christ.

~To think my worst enemies my best friends, for the brethren of Joseph could never have done him so much good with their love and favor as they did him with their malice and hatred.

~These minds are more to be desired of every man than all the treasures of all the princes and kings, Christian and heathen, were it gathered and laid together all in one heap.

Amen

Image from wikipedia commons.

Published on July 05, 2013 22:30

July 4, 2013

BBC History Talks and Festivals in July and October

Two upcoming events:

Two upcoming events:History Live! hosted by the English Heritage Society at Kellmarsh Hall in Northamptonshire features a BBC History Magazine Lecture Tent with many important scholars and interesting topics, including several on English Reformation era topics. For example:

~Elizabeth I: The Queen's Two Bodies

Anna Whitelock will look at the life of Queen Elizabeth I, as both a public and a private person.

About the speaker: Anna Whitelock is a senior lecturer in early modern history at Royal Holloway, University of London. She is also a popular historical author, and her latest book Elizabeth's Bedfellows: An Intimate History of the Queen's Court is published in May.

and

~Scars on the Landscape: Encountering the Dissolution of the Monasteries

By examining some of those places one can visit today, Suzannah Lipscomb will explore the extraordinary impact of Henry VIII's suppression of the monasteries. She will draw out the poignant insights that remaining sites can give us into the enormous extent of the Tudor devastation.

About the speaker: Suzannah Lipscomb is a historian and broadcaster who specialises in the Tudor period. She is Senior Lecturer and Convenor for History at New College of the Humanities. Her most recent book is A Visitor's Companion to Tudor England.

History Live! is scheduled for Saturday and Sunday, 20-21 July.

The BBC History Magazine is hosting its own festival, the BBC History Weekend in Malmesbury, Wiltshire:

This autumn sees the launch of the very first BBC History Magazine weekend festival, in the ancient hilltop town of Malmesbury in Wiltshire. It is the oldest borough in England, with a charter given by Alfred the Great in 880. It’s also the burial place of Æthelstan, grandson of Alfred and the first king of all England, and the abbey that houses his tomb is Malmesbury’s crowning glory. In 1000 AD, Eilmer the flying monk had an early attempt at aviation from the Abbey’s tower (it failed; he broke his legs), and in the churchyard is buried one Hannah Twynnoy, famously eaten by a tiger in the town in 1703. The 17th-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes was born in Malmesbury, so it’s an ideal venue for a history festival.

More than 20 top-name historians will be speaking over the course of the weekend in two lecture rooms in Malmesbury’s Town Hall. There will be a fully-stocked history bookshop, courtesy of Waterstones Cirencester, within the Town Hall for the duration of the festival, where our speakers will be signing books.

Speakers range from Leanda de Lisle to Alison Weir, from Dan Jones to Helen Castor, Linda Porter and Michael Wood, and topics they will discuss are most wide-ranging.

Malmesbury Abbey is now an Anglican parish church, but of course it was a monastery before the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII. It was founded in the 7th century as a Benedictine monastery and King Athelstan is bured there. This event is scheduled for October 25 through 27.

Published on July 04, 2013 22:30

July 3, 2013

Happy Independence Day!

From The Wall Street Journal, by David Dubal:

The best Fourth of July celebration I could give myself would be to play through (even sloppily) Louis Moreau Gottschalk's dazzling display of fireworks, "The Union: Concert Paraphrase on National Airs." It's a terrific concoction of approximately eight minutes of American patriotic tunes, where Gottschalk weaves together "Yankee Doodle," "Hail, Columbia" and "The Star-Spangled Banner," the last not yet the official anthem of the United States. Composed in 1862, Gottschalk (1829-1869) dedicated "The Union" to his favorite Union general, George B. McClellan.

The composition begins with a brilliant cannonade of octaves followed by a downward right-hand cadenza, as the composer leads to an exposition of the "The Star-Spangled Banner" marked malinconico, or melancholy. He then proceeds with trumpet calls and echoes on the piano, followed by droll drum rolls heard no less than 76 times in the left hand deep in the bass while playing "Hail, Columbia" in the right hand. Gottschalk is now ready to combine "Yankee Doodle" in the right hand with "Hail, Columbia" in the left in deft counterpoint. More trumpet calls follow, and then a blast of triple fortissimo octaves, Con Furia, plunging from the key of B-flat into a plush E-flat major, and once more joins "Yankee Doodle" with "Hail, Columbia," this time in glorious chordal pomp. It all ends grandioso, in triumph.

I cannot let the celebration of Independence Day go by without reminding you of the issues of religious liberty that we face in the U.S.A. today. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops has issued a letter, joined by signatories as diverse as the Krishnas, the Church of Scientology, the Southern Baptist Convention, many Catholic university presidents, the Anglican Church in North America, many other Evangelical Christian organizations, etc, etc, all "Standing Together for Religious Freedom."

And just a couple more reminders about the colonial efforts to promote religious freedom in Maryland with my two part review of Papist Patriots: The Making of American Catholic Identity by Maura Jane Farrelly, here and here. And don't forget that I wrote about Maryland's contribution to religious freedom in OSV's The Catholic Answer Magazine earlier this year.

God Bless America!

Published on July 03, 2013 22:30

July 2, 2013

The Brother and the Curate: The Hollywood Bronte Family

Last night, I watched Devotion, the 1946 Warner Brothers biopic of the Bronte sisters, Charlotte, Emily, and Anne--and their brother Branwell, and their father's curate, Mr. Arthur Nichols. The names and the setting of the movie are mostly accurate, but much of the biography is not, of course. I still found it an interesting movie, however, mostly because of the performances of Olivia de Havilland as Charlotte and of Ida Lupino as Emily. The actress (Nancy Coleman) who played Anne Bronte resembled the portrait painted by Branwell, but she is a secondary character.

Charlotte, as portrayed by de Havilland, is almost wilfully unaware of her errors and follies: forcing Emily to go to Brussels; falling in love with Monsieur Heger, the married headmaster of that school; her ambitious drive for literary fame is overwhelming; she consistently errs in interpreting the actions of her father's curate, Mr. Arthur Nicholls (Paul Henreid)--and generally, she does not know what is really going on! De Havilland plays this unself-aware heroine so well that the viewer wants to read her the riot act!

Emily is the real lead in the movie, at least as the trailer, linked above, indicates--she is the real genius, the true lover, the one devoted to her brother's best interests (knowing that London will be too tempting for him), in love with the curate, misunderstood by Charlotte; able to see Charlotte's folly--drawn to the moors, dreaming of death (or Heathcliff?).

In typical Hollywood fashion, the accents vary wildly. Lupino was born in England and de Havilland in Japan of British parents, but Paul Henreid's Austro-Hungarian accent is unremarked and unexplained. As the Reverend Mr. Patrick Bronte's curate, he seems very well off, with an elegant wardrobe--he is depicted as doing good works in the parish, visiting the poor and the sick, but one of his most constant efforts is getting the drunken Branwell home from the pub or the party. Those efforts earn him only animosity from Charlotte--and from Emily at first. The Reverend Mr. Patrick Bronte, played by Montagu Love, is always in his study, preparing a sermon. We never see the inside of Reverend Bronte's church.

Arthur Kennedy as Branwell Bronte is a convincing drunk, although it's not very clear why his sisters are so devoted to him because he is so mocking of their efforts and even of their sacrifices for him. The film completely ignores the fantasy world the sisters and brother developed, nor does it depict the poverty, want, and death the family struggled with--the sisters did not become governess to earn extra money! . Still, it was a fascinating movie to watch for the sake of the two lead actresses, Lupino and de Havilland.

Published on July 02, 2013 22:30