Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 264

July 31, 2013

Book Review: Catholics of the Anglican Patrimony

I have submitted a review of this slender volume to the St. Austin Review (StAR) but I also promised I'd offer a review on my blog, so here are some comments about this brief, but very thorough, analysis of the Personal Ordinariate--only 82 pages! (Note that this is NOT what I submitted to StAR.)

Although there are only 82 pages in this book, it is filled with insights from Father Aidan Nichols, OP, and like many fine books, it leads the reader to other books, specifically two by the author: The Panther and the Hind and The Realm . It leads to those books directly, because Father Nichols mentions them in the text--but it could also leads to another book, Christendom Awake . Those three books precede this book precisely because in the last chapter of Catholics of the Anglican Patrimony, Nichols highlights the mission of the Anglican Ordinariate as being a great leader in the New Evangelization and in the goal of the conversion of England.

In the first chapter, Father Nichols places the founding of the Anglican Ordinariates in the context of the Anglo-Catholic tradition of the Church of England, proposing that it is the logical result of that tradition and those within it yearning for the true Church while finding their position in the Church of England untenable.

In the second chapter he examines Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI's vision for true Christian unity and the role of beatiful and ordered liturgy, noting that four of the religious communities Benedict XVI focused on (The Society of Pope Pius X, a certain group of Lutherans, the Eastern Orthodox, and the Anglo-Catholic, High Church Anglicans) each place a high value on such liturgy.

In the penultimate chapter--the one which I found least helpful--Father Nichols looks at the decisions about the Anglican Use for the Personal Ordinariate. I found this chapter least helpful simply because it seemed inconclusive.

Finally, in the last chapter he presents his thesis that the Catholics of the Anglican Patrimony can answer the call he made in The Realm for the conversion of England. He believes that since these Catholics are more "native" to England they will be able to reach out to English culture more easily. He also notes that since these Catholics have not been involved in some of the confusions between left and right in the Catholic Church since the Second Vatican Council they can reach out to disaffected Catholics more easily.

In summary, although the book is very short, it is comprehensive and instructive.

Published on July 31, 2013 23:00

From Conference to Collected Essays

In October of 2010, Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois held a conference titled "Reforming the Reformation". Augustana College is a Lutheran, liberal arts college. The conference description:

Augustana will host the conference "Reforming Reformation" on October 17-19, 2010, organized by Thomas F. Mayer (History). The object is to undertake a fundamental rethinking of all the possible meanings of the term reformation, concept and label. In order to stimulate such thought, the conferees will be divided into four vaguely "national" panels, emphasizing places that either did not have a "real" reformation or had an odd one. This will serve to put in perspective what far too many people still count as the only true reformation, the Protestant one especially in its Lutheran and Calvinist guises. Those four panels will treat Italy, England (emphasizing the Marian interlude since it has almost always been considered a bump on the way to seeing God's will done), the Empire and Spain. Needless to say, the conference will be strongly interdisciplinary, with participants from literature, art history, theology and history.

The conference will be spent mainly in discussion, rather than sitting through papers one after another. Participants will submit their talks at least a month in advance and they will then be circulated to all and sundry. They will also be posted on the Web in such a way that folk at Augustana can get access to them. Sessions will consist of ten-minute summaries followed by discussion and audience interventions. We want to involve students and members of the community as much as possible. The sessions will mix papers up geographically to see what extra comparative sparks that can strike. The conference will open with a plenary session on Sunday evening, mainly to introduce the participants and the themes. The working sessions will be spread through the day on Monday (various history faculty have generously given up their rooms and periods) before we end with one more plenary session, probably at 8:30 on Tuesday morning.

The participants have been urged to think as much as possible about big questions and broader implications. The final versions of their papers will go into a volume to be edited by Mayer and published in his series, "Catholic Christendom, 1300-1700," which will also include a ruminative essay based on the discussions.

List of participants

I. Italy

Daniel Bornstein (history), Washington University

Marcia Hall (art history), Temple University

Abigail Brundin (literature), St Catherine's College, University of Cambridge

II. England

Peter Marshall (history), University of Warwick, England

Anne Overell (history), The Open University, Leeds, England

III. The Empire

John Frymire (history), University of Missouri

Brad Gregory (history), University of Notre Dame Ronald Thiemann (theology), Harvard Divinity School

IV. Spain

LuAnn Homza (history), College of William and Mary

John Edwards (history), Queen's College, University of Oxford Jodi Bilnikoff (history), UNC-Greensboro

Sponsored by the Office of the President, the Institute for Leadership and Service and the Center for the Study of the Christian Millennium, with the support of the Humanities Fund and the Department of History

The result of this conference was indeed a book from Ashgate, which publishes some of the most interesting books at the highest prices imaginable, especially in their Catholic Christendom, 1300–1700 series. The book has the same title as the conference, and Ashgate describes it thus:

The Reformation used to be singular: a unique event that happened within a tidily circumscribed period of time, in a tightly constrained area and largely because of a single individual. Few students of early modern Europe would now accept this view. Offering a broad overview of current scholarly thinking, this collection undertakes a fundamental rethinking of the many and varied meanings of the term concept and label 'reformation', particularly with regard to the Catholic Church.

Accepting the idea of the Reformation as a process or set of processes that cropped up just about anywhere Europeans might be found, the volume explores the consequences of this through an interdisciplinary approach, with contributions from literature, art history, theology and history. By examining a single topic from multiple interdisciplinary perspectives, the volume avoids inadvertently reinforcing disciplinary logic, a common result of the way knowledge has been institutionalized and compartmentalized in research universities over the last century.

The result of this is a much more nuanced view of Catholic Reformation, and once that extends consideration much further - both chronologically, geographically and politically - than is often accepted. As such the volume will prove essential reading to anyone interested in early modern religious history.

Ashgate provides a sample from the book, the Introduction by Thomas Mayer, and Augustana provides as least two of the presentations on-line, by Peter Marshall and by Brad S. Gregory.

Augustana will host the conference "Reforming Reformation" on October 17-19, 2010, organized by Thomas F. Mayer (History). The object is to undertake a fundamental rethinking of all the possible meanings of the term reformation, concept and label. In order to stimulate such thought, the conferees will be divided into four vaguely "national" panels, emphasizing places that either did not have a "real" reformation or had an odd one. This will serve to put in perspective what far too many people still count as the only true reformation, the Protestant one especially in its Lutheran and Calvinist guises. Those four panels will treat Italy, England (emphasizing the Marian interlude since it has almost always been considered a bump on the way to seeing God's will done), the Empire and Spain. Needless to say, the conference will be strongly interdisciplinary, with participants from literature, art history, theology and history.

The conference will be spent mainly in discussion, rather than sitting through papers one after another. Participants will submit their talks at least a month in advance and they will then be circulated to all and sundry. They will also be posted on the Web in such a way that folk at Augustana can get access to them. Sessions will consist of ten-minute summaries followed by discussion and audience interventions. We want to involve students and members of the community as much as possible. The sessions will mix papers up geographically to see what extra comparative sparks that can strike. The conference will open with a plenary session on Sunday evening, mainly to introduce the participants and the themes. The working sessions will be spread through the day on Monday (various history faculty have generously given up their rooms and periods) before we end with one more plenary session, probably at 8:30 on Tuesday morning.

The participants have been urged to think as much as possible about big questions and broader implications. The final versions of their papers will go into a volume to be edited by Mayer and published in his series, "Catholic Christendom, 1300-1700," which will also include a ruminative essay based on the discussions.

List of participants

I. Italy

Daniel Bornstein (history), Washington University

Marcia Hall (art history), Temple University

Abigail Brundin (literature), St Catherine's College, University of Cambridge

II. England

Peter Marshall (history), University of Warwick, England

Anne Overell (history), The Open University, Leeds, England

III. The Empire

John Frymire (history), University of Missouri

Brad Gregory (history), University of Notre Dame Ronald Thiemann (theology), Harvard Divinity School

IV. Spain

LuAnn Homza (history), College of William and Mary

John Edwards (history), Queen's College, University of Oxford Jodi Bilnikoff (history), UNC-Greensboro

Sponsored by the Office of the President, the Institute for Leadership and Service and the Center for the Study of the Christian Millennium, with the support of the Humanities Fund and the Department of History

The result of this conference was indeed a book from Ashgate, which publishes some of the most interesting books at the highest prices imaginable, especially in their Catholic Christendom, 1300–1700 series. The book has the same title as the conference, and Ashgate describes it thus:

The Reformation used to be singular: a unique event that happened within a tidily circumscribed period of time, in a tightly constrained area and largely because of a single individual. Few students of early modern Europe would now accept this view. Offering a broad overview of current scholarly thinking, this collection undertakes a fundamental rethinking of the many and varied meanings of the term concept and label 'reformation', particularly with regard to the Catholic Church.

Accepting the idea of the Reformation as a process or set of processes that cropped up just about anywhere Europeans might be found, the volume explores the consequences of this through an interdisciplinary approach, with contributions from literature, art history, theology and history. By examining a single topic from multiple interdisciplinary perspectives, the volume avoids inadvertently reinforcing disciplinary logic, a common result of the way knowledge has been institutionalized and compartmentalized in research universities over the last century.

The result of this is a much more nuanced view of Catholic Reformation, and once that extends consideration much further - both chronologically, geographically and politically - than is often accepted. As such the volume will prove essential reading to anyone interested in early modern religious history.

Ashgate provides a sample from the book, the Introduction by Thomas Mayer, and Augustana provides as least two of the presentations on-line, by Peter Marshall and by Brad S. Gregory.

Published on July 31, 2013 22:30

July 30, 2013

From 1986 to 2013: The Debate On The English Reformation

Rosemary O'Day, Emeritus Professor and Senior Research Associate in History at the Open University, has revised her 1986 book on the historiography of the English Reformation. From Manchester University Press:

Extensively revised and updated, this new edition of The debate on the English Reformation combines a discussion of successive historical approaches to the English Reformation with a critical review of recent debates in the area, offering a major contribution to modern historiography as well as to Reformation studies. It explores the way in which successive generations have found the Reformation relevant to their own times and have in the process rediscovered, redefined and rewritten its story. It shows that not only people who called themselves historians but also politicians, ecclesiastics, journalists and campaigners argued about interpretations of the Reformation and the motivations of its principal agents. The author also shows how, in the twentieth century, the debate was influenced by the development of history as a subject and, in the twenty-first century, by state control of the academy. Undergraduates, researchers and lecturers alike will find this an invaluable and essential companion to their studies.

Introduction

1. Contemporary historiography of the English Reformation, 1525–70

2. Interpretations of the Reformation from Fuller to Strype

3. Historians and contemporary politics: 1780–1850

4. The Church of England in crisis: the Reformation heritage

5. The Tudor revolution in religion: the twentieth-century debate

6. The Reformation and the people: Discovery

7. The Church: how it changed

8. The Debate in the age of peer review

9. The Place of the Reformation in modern biography, fiction and the media

Conclusion: Reformation: Reformulation, Reiteration and Reflections

Further Reading

Name index

Subject index

I've indicated the completely new chapters with bold type, but as the publisher's blurb notes that the book is "extensively revised and updated" I would not be surprised to see new material in the other chapters, too. Should be a fascinating update on a text which helped me considerably in my early research.

Published on July 30, 2013 23:00

July 29, 2013

The Second Earl of Southampton Succeeds

Upon the death of his father, Thomas Wriothesley, the First Earl, five year old Henry Wriothesley became the Second Earl of that title on July 30, 1550. His mother, the former Jane Cheney, as a devout Catholic and remained so in spite of changes in the official religion of England. When Henry was baptized, both Henry VIII and the Princess Mary were godparents, and his mother was effectively his guardian until he came of age (in spite of a gentleman being named his official guardian), raising him in the Catholic faith.

Although he was raised Catholic, his noble family standing shielded him from the normal disabilities, fines, and other punishments of the Recusant era. He married Mary Browne, the daughter of Anthony Browne, 1st Viscount Montagu, who also remained Catholic during the succeeding Tudor changes of official religion. Browne remained as Sheriff and MP during Edward VI's reign, but took leadership positions during Mary I's reign, including travel to Rome during negotiations with Pope Julius III to reinstate Catholicism in England. Note that Browne protested the acts of Elizabeth I's first Parliament to establish the Church of England.

It was Henry Wriothesley's connection to Thomas Howard, the Fourth Duke of Norfolk and the latter's plans to marry the deposed Mary, Queen of Scots in 1569 (around the same time as the Northern Rebellion) that plunged both Wriothesley and his father-in-law into trouble with Elizabeth I. Add to that the heightened tension for Catholics in England caused by the Papal Bull of 1570, with the choice of loyalty to the Church or loyalty to the Queen, and it's no surprise that the Second Earl of Southampton spent some time in the Tower of London. This site notes that it might have been from 1571 to 1574. Then he returned to Hampshire in positions of trust--but, was suspected of having sheltered St. Edmund Campion in 1581--and died on October 4, 1581.

Henry's son Henry became the Third Earl of Southampton, Shakespeare's patron, who also spent some time in the Tower; his daughter Mary married into another Catholic noble family as the first wife of Thomas Arundell, 1st Baron Arundell of Wardour (and he spent some time in the Tower because he was a Catholic too!). After the Fourth Earl of Southamption died in 1667, the title was extinct, because Thomas Wriothesley had only daughters from three marriages.

Interestingly, I find no portrait of the Second Earl on-line at the National Portrait Gallery in London--eleven of son and ten of his grandson, but none of him! The image above is a photo of his tomb in St Peter's Church, Titchfield, Hampshire, with his mother's tomb above, from wikipedia commons. As you might surmise, St. Peter's Church was the family church, obtained from the Court of Augmentations by Thomas Wriothesley, the First Earl, upon the suppression of the Premonstratensian Abbey on December 28, 1537--the family tombs occupy the South Chapel.

Published on July 29, 2013 22:30

July 28, 2013

William Wilberforce, The Great Emancipator, RIP

When the movie Amazing Grace was released on DVD several years ago, we gave copies of it to many people as Christmas presents because we were so impressed by the story of William Wilberforce--who died on July 29 in 1833--and the effectiveness of the presentation of his causes and faith in the movie (although the latter was not as focused as it could have been). The movie was based on Eric Metaxas' book AMAZING GRACE: William Wilberforce and the Heroic Campaign to End Slavery. More on his life and influence here, from the BBC. Of course, the movie does not depict what happened in the Wilberforce family after his death: that three of his sons would become Catholics, mostly under the influence of the Oxford Movement. For that story, The Parting of Friends: The Wilberforces and Henry Manning by David Newsome is an excellent source. As David Denton reviewed Newsome's book in The New Oxford Review in 1994, he notes the context of their conversions: In England in the early 1800s, William Wilberforce was the Great Emancipator. He had been the most visible personality in the abolition of the British slave trade (1807), and of slavery itself in the Empire, though that would only occur shortly after his death. The joyful, self-sacrificing Christian influence that the senior Wilberforce and others of that wealthy evangelical group, the "Clapham Sect," brought to bear on English society was considerable. They have aptly been characterized as the Fathers of the Victorian Age.

When the movie Amazing Grace was released on DVD several years ago, we gave copies of it to many people as Christmas presents because we were so impressed by the story of William Wilberforce--who died on July 29 in 1833--and the effectiveness of the presentation of his causes and faith in the movie (although the latter was not as focused as it could have been). The movie was based on Eric Metaxas' book AMAZING GRACE: William Wilberforce and the Heroic Campaign to End Slavery. More on his life and influence here, from the BBC. Of course, the movie does not depict what happened in the Wilberforce family after his death: that three of his sons would become Catholics, mostly under the influence of the Oxford Movement. For that story, The Parting of Friends: The Wilberforces and Henry Manning by David Newsome is an excellent source. As David Denton reviewed Newsome's book in The New Oxford Review in 1994, he notes the context of their conversions: In England in the early 1800s, William Wilberforce was the Great Emancipator. He had been the most visible personality in the abolition of the British slave trade (1807), and of slavery itself in the Empire, though that would only occur shortly after his death. The joyful, self-sacrificing Christian influence that the senior Wilberforce and others of that wealthy evangelical group, the "Clapham Sect," brought to bear on English society was considerable. They have aptly been characterized as the Fathers of the Victorian Age.Wilberforce sent three sons, Robert, Samuel, and Henry, to be educated at Oxford's Oriel College. This was a departure for an evangelical or Low Churchman, since most sons of these families were sent to Cambridge University, which was considered much more sympathetic to Low Church theology. At Oxford these bright, high-minded sons of the Great Emancipator became part of the golden academic renaissance that had been taking place there since the turn of the 17th century. There they came into contact not only with the High Church influence of John Keble and Edward Posey, but with Hurrell Froude and John Henry Newman, both former evangelicals whose Anglo-Catholicism had not only begun to nettle the somnambulant C. of E., but was, for evangelicals, threatening the Reformation itself. Troubling as they were for evangelicals, these Anglo-Catholics were inexorable adversaries of the latitudinarianism growing in power at Oxford and in the C. of E., which, then as now, submits the creeds, doctrines, and Scriptures to the delusions of skeptical reason and the acids of materialism. In fact, it's interesting to note that William Wilberforce died just 15 days after John Keble preached his "National Apostasy" sermon and at the very date of his death, Hugh James Rose was holding a meeting at his church rectory in Hadleigh to form the Association of Friends of the Church, which Hurrell Froude and William Palmer led. The Oxford Movement or Tractarian movement really took off with John Henry Newman's sermons in the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin and the "Tracts for the Times", but the seeming coincidence of dates between the death of the Great Emancipator and the beginning of the Oxford Movement is fascinating.

Published on July 28, 2013 22:30

July 27, 2013

Wishful Thinking? Two Ways England Could be Catholic Today!

Although the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge were safely delivered of a healthy baby boy, a couple of British publications are looking back in history at a couple of "might have been" "what if's"--what if Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon's first baby boy have survived? and what if the eldest child, not the eldest son, had been the heir?

First, from the New Statesman , by Amy Licence:

History also provides examples of royal births which illuminate the pressures experienced by queens, whose role required them to deliver the future, in a literal and metaphorical sense. Henry VIII’s marital exploits are well known, but the birth of his first son, early in his reign, is less well remembered. Following his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, in 1509, Henry began the quest to father a son which would last for the next 28 years. It was to be far more difficult to achieve than he could ever have imagined. Early in 1511, Catherine delivered a boy whom they named Henry. When the news was proclaimed, London went into celebration. Days of public rejoicing and partying followed, with bells ringing, wine flowing, cannons at the Tower booming and bonfires burning in the streets. The boy was given a magnificent christening, with jousts, pageants, feasts and tournaments: it was the second most expensive occasion of Henry’s reign, outshone only by the legendary Field of Cloth of Gold. A special gallery was built for Catherine and her ladies to watch the proceedings and it seemed as if the future of the Tudor dynasty was secure.

However, tragedy struck. Before the child was two months old, he succumbed to one of the infant illnesses of the day. Had he lived, the little prince would have become Henry IX of England. Although it is not possible to rewrite history, the implications of his imagined survival help us understand the impact of his premature death. Had this child lived, the well-known story of Henry’s six wives almost certainly would not have happened. Perhaps the course of the English Reformation would also have played out differently. There would have been no Edward VI, no Mary I or even Queen Elizabeth. The imagined reign of Henry IX is another historical “whatif” which provides a fascinating alternative path for English history; save for one small twist of fate, perhaps even an infection that may easily be cleared up by antibiotics today, it may have become established historical fact. The life and death of this tragic prince truly did shape the future of his country.

And this from the Mirror :

What if the monarch's oldest child - even if it was a girl - had always inherited the throne? Well, we could all be Catholic... and speaking German.

VICTORIA II NOT EDWARD VIIBy marrying Frederick II of Prussia in 1858, Queen Victoria's oldest child, daughter Victoria, 17, became Empress of Germany and Queen of Prussia.

She would have become Britain's queen on January 21, 1901, when her mother died. But she died of breast cancer on August 5 that year.

The throne would then have gone to her son - Kaiser Wilhelm II who led Germany during the First World War.

ELIZABETH II NOT CHARLES IIf we'd let the oldest child inherit the throne 400 years ago, it could have prevented the English Civil War. On the death of James I in 1625, his daughter Elizabeth would have become queen, instead of Charles I. Her descendants were the rulers of Hanover, who later become Britain's kings - her ninth great granddaughter is the real Elizabeth II.

MARGARET I NOT HENRY VIIIAfter the death of Henry VII in 1509, eldest daughter Margaret Tudor could have become monarch instead of the most famous king of all, Henry VIII.

Without Henry's plea in vain for the Pope to annul his heirless marriage to Catherine of Aragon would there have been an English Reformation at all?

Margaret had married James IV of Scotland and their Stuart line ended up inheriting England's throne anyway.

ELIZABETH I NOT EDWARD VMaybe she had a lucky escape, otherwise Elizabeth - eldest child of Edward IV, could have been murdered by her uncle (later Richard III) just like her brothers, the Princes in the Tower.

She became Queen Consort when she married Henry VII. So she was the daughter, sister, niece, wife and mother of monarchs Edward IV and V, Richard III, Henry VII and VIII.

But, as Captain James T. Kirk certainly knows, you just can't mess with the space-time continuum!

First, from the New Statesman , by Amy Licence:

History also provides examples of royal births which illuminate the pressures experienced by queens, whose role required them to deliver the future, in a literal and metaphorical sense. Henry VIII’s marital exploits are well known, but the birth of his first son, early in his reign, is less well remembered. Following his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, in 1509, Henry began the quest to father a son which would last for the next 28 years. It was to be far more difficult to achieve than he could ever have imagined. Early in 1511, Catherine delivered a boy whom they named Henry. When the news was proclaimed, London went into celebration. Days of public rejoicing and partying followed, with bells ringing, wine flowing, cannons at the Tower booming and bonfires burning in the streets. The boy was given a magnificent christening, with jousts, pageants, feasts and tournaments: it was the second most expensive occasion of Henry’s reign, outshone only by the legendary Field of Cloth of Gold. A special gallery was built for Catherine and her ladies to watch the proceedings and it seemed as if the future of the Tudor dynasty was secure.

However, tragedy struck. Before the child was two months old, he succumbed to one of the infant illnesses of the day. Had he lived, the little prince would have become Henry IX of England. Although it is not possible to rewrite history, the implications of his imagined survival help us understand the impact of his premature death. Had this child lived, the well-known story of Henry’s six wives almost certainly would not have happened. Perhaps the course of the English Reformation would also have played out differently. There would have been no Edward VI, no Mary I or even Queen Elizabeth. The imagined reign of Henry IX is another historical “whatif” which provides a fascinating alternative path for English history; save for one small twist of fate, perhaps even an infection that may easily be cleared up by antibiotics today, it may have become established historical fact. The life and death of this tragic prince truly did shape the future of his country.

And this from the Mirror :

What if the monarch's oldest child - even if it was a girl - had always inherited the throne? Well, we could all be Catholic... and speaking German.

VICTORIA II NOT EDWARD VIIBy marrying Frederick II of Prussia in 1858, Queen Victoria's oldest child, daughter Victoria, 17, became Empress of Germany and Queen of Prussia.

She would have become Britain's queen on January 21, 1901, when her mother died. But she died of breast cancer on August 5 that year.

The throne would then have gone to her son - Kaiser Wilhelm II who led Germany during the First World War.

ELIZABETH II NOT CHARLES IIf we'd let the oldest child inherit the throne 400 years ago, it could have prevented the English Civil War. On the death of James I in 1625, his daughter Elizabeth would have become queen, instead of Charles I. Her descendants were the rulers of Hanover, who later become Britain's kings - her ninth great granddaughter is the real Elizabeth II.

MARGARET I NOT HENRY VIIIAfter the death of Henry VII in 1509, eldest daughter Margaret Tudor could have become monarch instead of the most famous king of all, Henry VIII.

Without Henry's plea in vain for the Pope to annul his heirless marriage to Catherine of Aragon would there have been an English Reformation at all?

Margaret had married James IV of Scotland and their Stuart line ended up inheriting England's throne anyway.

ELIZABETH I NOT EDWARD VMaybe she had a lucky escape, otherwise Elizabeth - eldest child of Edward IV, could have been murdered by her uncle (later Richard III) just like her brothers, the Princes in the Tower.

She became Queen Consort when she married Henry VII. So she was the daughter, sister, niece, wife and mother of monarchs Edward IV and V, Richard III, Henry VII and VIII.

But, as Captain James T. Kirk certainly knows, you just can't mess with the space-time continuum!

Published on July 27, 2013 22:30

July 26, 2013

Happy Birthday, Hilaire Belloc! Born in Arcadia

Hilaire Belloc was born on July 27, 1870 in La Celle-Saint-Cloud, west of Paris. Above: the seal of the city. Did you know that his mother, Bessie Raynor Parkes Belloc, was a suffragette? She was also a convert to Catholicism, influenced not only by the intellectual arguments of the Oxford Movement converts but also by the practical charity work of Catholic nuns and she joined the Catholic Church in 1864. According to the wikipedia article on her life:

Hilaire Belloc was born on July 27, 1870 in La Celle-Saint-Cloud, west of Paris. Above: the seal of the city. Did you know that his mother, Bessie Raynor Parkes Belloc, was a suffragette? She was also a convert to Catholicism, influenced not only by the intellectual arguments of the Oxford Movement converts but also by the practical charity work of Catholic nuns and she joined the Catholic Church in 1864. According to the wikipedia article on her life:Aged 38, Bessie Rayner Parkes fell in love with a Frenchman of delicate health, named Louis Belloc, himself the son of a notable woman, Louise Swanton-Belloc. Their five-year long marriage, spent in France, was described by Parkes as Arcadia. The family lived through the Franco-Prussian War and was deeply affected by it on a material level. Parkes never got over her husband’s sudden death in 1872. Their children, Marie Belloc Lowndes (1868-1947) and Hilaire Belloc (1870-1953), went on to become renowned writers in their different ways.

Another source gives more background on the family tree.

According to this site, her husband died of sunstroke. Belloc's sister, Marie, wrote The Lodger, based on the Jack the Ripper crimes. Alfred Hitchcock filmed a silent version, starring Ivor Novello, while Laird Gregar and Merle Oberon starred in the 1944 "talkie". After his father's death, Belloc's mother returned to England and he attended the Oratory in Birmingham.

Happy birthday, JOSEPH HILAIRE PIERRE RENE BELLOC!

Published on July 26, 2013 23:00

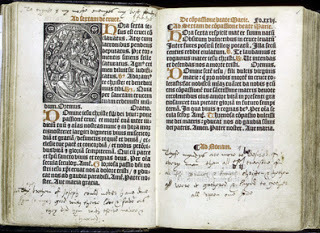

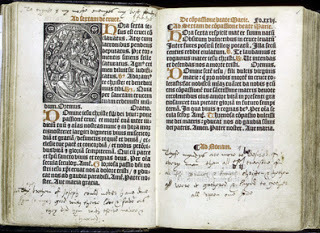

St. Thomas More's Breviary, With Marginalia

Thanks to Elena Maria Vidal's Tea at Trianon blog for her link to Daniel Mitsui's post on St. Thomas More's Breviary, showing the prayer he composed in the Tower of London in the margins at the top and bottum of the pages:

Give me the grace, Good Lord

~To set the world at naught.

~To set the mind firmly on You and not to hang upon the words of men's mouths.

~To be content to be solitary. Not to long for worldly pleasures. Little by little utterly to cast off the world and rid my mind of all its business.

~Not to long to hear of earthly things, but that the hearing of worldly fancies may be displeasing to me.

~Gladly to be thinking of God, piteously to call for His help. To lean into the comfort of God. Busily to labor to love Him.

~To know my own vileness and wretchedness. To humble myself under the mighty hand of God. To bewail my sins and, for the purging of them, patiently to suffer adversity.

~Gladly to bear my purgatory here. To be joyful in tribulations. To walk the narrow way that leads to life.

~To have the last thing in remembrance. To have ever before my eyes my death that is ever at hand. To make death no stranger to me. To foresee and consider the everlasting fire of Hell. To pray for pardon before the judge comes.

~To have continually in mind the passion that Christ suffered for me. For His benefits unceasingly to give Him thanks.

~To buy the time again that I have lost. To abstain from vain conversations. To shun foolish mirth and gladness. To cut off unnecessary recreations.

~Of worldly substance, friends, liberty, life and all, to set the loss at naught, for the winning of Christ.

~To think my worst enemies my best friends, for the brethren of Joseph could never have done him so much good with their love and favor as they did him with their malice and hatred.

~These minds are more to be desired of every man than all the treasures of all the princes and kings, Christian and heathen, were it gathered and laid together all in one heap.

Amen

As he wrote this while in the Tower of London, held there because he would not swear first, the Oath of Succession and then the Oath of Supremacy, Thomas More was obviously preparing himself for martyrdom. He had already lost his freedom, his influence, his power, his friends, and many of the comforts of his family and he was praying to be reconciled to those losses:

~To be content to be solitary. Not to long for worldly pleasures. Little by little utterly to cast off the world and rid my mind of all its business.

More had loved to be with family and friends, to share hospitality and conversation--but now he was in the Tower, solitary and without those pleasures (except for the visits of his daughter, Margaret). He must have longed for those days of conviviality!

~To buy the time again that I have lost. To abstain from vain conversations. To shun foolish mirth and gladness. To cut off unnecessary recreations.

More's sense of humor and delight in fun is well known. Now he's in the Tower, he is obviously not enjoying "unnecessary recreations" but he is clearly weaning himself away from even common pleasures.

~To think my worst enemies my best friends, for the brethren of Joseph could never have done him so much good with their love and favor as they did him with their malice and hatred.

As More endured his imprisonment, the constant pressure to take the oaths; even as he encountered the injustice of his trial on July 1, 1535--he still showed great compassion and almost mercy to those who were harassing and prosecuting him. He even hoped that they somehow would meet "merrily in heaven" after all these earthly conflicts.

~These minds are more to be desired of every man than all the treasures of all the princes and kings, Christian and heathen, were it gathered and laid together all in one heap.

More is putting everything in the perspective of eternity--weighing in a balance the renunciation of all worldly pleasures and even innocent human happiness, and treasuring the opportunity to endure his purgatory while on earth and follow the narrow path, even as it means losing so many of the good things he'd enjoyed while free.

Amen.

Give me the grace, Good Lord

~To set the world at naught.

~To set the mind firmly on You and not to hang upon the words of men's mouths.

~To be content to be solitary. Not to long for worldly pleasures. Little by little utterly to cast off the world and rid my mind of all its business.

~Not to long to hear of earthly things, but that the hearing of worldly fancies may be displeasing to me.

~Gladly to be thinking of God, piteously to call for His help. To lean into the comfort of God. Busily to labor to love Him.

~To know my own vileness and wretchedness. To humble myself under the mighty hand of God. To bewail my sins and, for the purging of them, patiently to suffer adversity.

~Gladly to bear my purgatory here. To be joyful in tribulations. To walk the narrow way that leads to life.

~To have the last thing in remembrance. To have ever before my eyes my death that is ever at hand. To make death no stranger to me. To foresee and consider the everlasting fire of Hell. To pray for pardon before the judge comes.

~To have continually in mind the passion that Christ suffered for me. For His benefits unceasingly to give Him thanks.

~To buy the time again that I have lost. To abstain from vain conversations. To shun foolish mirth and gladness. To cut off unnecessary recreations.

~Of worldly substance, friends, liberty, life and all, to set the loss at naught, for the winning of Christ.

~To think my worst enemies my best friends, for the brethren of Joseph could never have done him so much good with their love and favor as they did him with their malice and hatred.

~These minds are more to be desired of every man than all the treasures of all the princes and kings, Christian and heathen, were it gathered and laid together all in one heap.

Amen

As he wrote this while in the Tower of London, held there because he would not swear first, the Oath of Succession and then the Oath of Supremacy, Thomas More was obviously preparing himself for martyrdom. He had already lost his freedom, his influence, his power, his friends, and many of the comforts of his family and he was praying to be reconciled to those losses:

~To be content to be solitary. Not to long for worldly pleasures. Little by little utterly to cast off the world and rid my mind of all its business.

More had loved to be with family and friends, to share hospitality and conversation--but now he was in the Tower, solitary and without those pleasures (except for the visits of his daughter, Margaret). He must have longed for those days of conviviality!

~To buy the time again that I have lost. To abstain from vain conversations. To shun foolish mirth and gladness. To cut off unnecessary recreations.

More's sense of humor and delight in fun is well known. Now he's in the Tower, he is obviously not enjoying "unnecessary recreations" but he is clearly weaning himself away from even common pleasures.

~To think my worst enemies my best friends, for the brethren of Joseph could never have done him so much good with their love and favor as they did him with their malice and hatred.

As More endured his imprisonment, the constant pressure to take the oaths; even as he encountered the injustice of his trial on July 1, 1535--he still showed great compassion and almost mercy to those who were harassing and prosecuting him. He even hoped that they somehow would meet "merrily in heaven" after all these earthly conflicts.

~These minds are more to be desired of every man than all the treasures of all the princes and kings, Christian and heathen, were it gathered and laid together all in one heap.

More is putting everything in the perspective of eternity--weighing in a balance the renunciation of all worldly pleasures and even innocent human happiness, and treasuring the opportunity to endure his purgatory while on earth and follow the narrow path, even as it means losing so many of the good things he'd enjoyed while free.

Amen.

Published on July 26, 2013 22:30

July 25, 2013

Five Years Before the End of the English Monasteries: 1535 to 1540

Five years is a long time, isn't it? One thousand, eight hundred, and twenty-six days, with an extra day for Leap Year thrown in; six hundred and twenty-four weeks; sixty months. Yet when we look back at history, the days, weeks, and months seem to slide by: Thomas Cromwell starts his Visitation of the Monasteries and then they're all gone, just like that! But during those five years, the monks, friars and nuns in England didn't stop living their lives as monks, friars, and nuns: they prayed the Divine Office, observing the Hours and their Rule; they celebrated feasts and endured fasts; they read and studied and worked--and they responded to the religious changes going on around them. Mary C. Erler, author of

Women, Reading, and Piety in Late Medieval England

also from Cambridge University Press, proposes to describe that reality by studying what the monks, friars, and nuns read and wrote during those crucial years of the history of monasticism in England, from 1530 to 1558.

Five years is a long time, isn't it? One thousand, eight hundred, and twenty-six days, with an extra day for Leap Year thrown in; six hundred and twenty-four weeks; sixty months. Yet when we look back at history, the days, weeks, and months seem to slide by: Thomas Cromwell starts his Visitation of the Monasteries and then they're all gone, just like that! But during those five years, the monks, friars and nuns in England didn't stop living their lives as monks, friars, and nuns: they prayed the Divine Office, observing the Hours and their Rule; they celebrated feasts and endured fasts; they read and studied and worked--and they responded to the religious changes going on around them. Mary C. Erler, author of

Women, Reading, and Piety in Late Medieval England

also from Cambridge University Press, proposes to describe that reality by studying what the monks, friars, and nuns read and wrote during those crucial years of the history of monasticism in England, from 1530 to 1558.From Cambridge University Press:

Reading and Writing during the Dissolution: Monks, Friars, and Nuns 1530–1558

Author: Mary C. Erler From 1534 when Henry VIII became head of the English church until the end of Mary Tudor's reign in 1558, the forms of English religious life evolved quickly and in complex ways. At the heart of these changes stood the country's professed religious men and women, whose institutional homes were closed between 1535 and 1540. Records of their reading and writing offer a remarkable view of these turbulent times. The responses to religious change of friars, anchorites, monks and nuns from London and the surrounding regions are shown through chronicles, devotional texts, and letters. What becomes apparent is the variety of positions that English religious men and women took up at the Reformation and the accommodations that they reached, both spiritual and practical. Of particular interest are the extraordinary letters of Margaret Vernon, head of four nunneries and personal friend of Thomas Cromwell.

~Richly detailed biographies of English monks, friars and nuns, examining their reading and writing

~Offers a fascinating look at the human complexities produced by the Dissolution

~Shows the continuities, as well as the ruptures, in the shift away from traditional social and religious forms

Table of Contents: 1. Looking backward?: London's last anchorite, Simon Appulby (†1537) 2. The Greyfriars Chronicle and the fate of London's Franciscan community

3. Cromwell's nuns: Katherine Bulkeley, Morpheta Kingsmill, Joan Fane

4. Cromwell's abbess and friend, Margaret Vernon

5. 'Refugee Reformation': the effects of exile

6. Richard Whitford's last work, 1541

Appendices

Bibliography

Google books sample here. Looks fascinating!

Published on July 25, 2013 23:00

Lord Rochester, RIP (and the Monkey?)

John Wilmot, the 2nd Earl of Rochester, Restoration poet, satirist, courtier, and patron of the arts, died on July 26, 1680. According to the wikipedia article on his life, career, and reputation, at Court he "was renowned for drunkenness, vivacious conversation, and "extravagant frolics" as part of the Merry Gang (as Andrew Marvell described them)." Charles II tolerated his bad behavior and made him a Gentleman of the Bedchamber and forgave his attempted elopement (abduction) of a rich heiress after only three weeks in the Tower of London.

John Wilmot, the 2nd Earl of Rochester, Restoration poet, satirist, courtier, and patron of the arts, died on July 26, 1680. According to the wikipedia article on his life, career, and reputation, at Court he "was renowned for drunkenness, vivacious conversation, and "extravagant frolics" as part of the Merry Gang (as Andrew Marvell described them)." Charles II tolerated his bad behavior and made him a Gentleman of the Bedchamber and forgave his attempted elopement (abduction) of a rich heiress after only three weeks in the Tower of London.His satires and attacks on the poets he sometimes supported and on Charles II led him into great trouble at Court, however and he did not stay in Charles's good graces long. He died at the young age of 33, and might have had a deathbed conversion, renouncing his wide life of debauchery and sin when Gilbert Burnet (before he became Bishop of Salisbury) visited him as his mother's insistence.

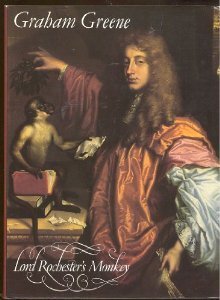

Graham Greene wrote a biography of Lord Rochester, and I remember reading it and being quite thrilled with how wicked Lord Rochester was! Walter Clemons reviewed Greene's book in 1974 for The New York Times and explained the title:

In the best known portrait of John Wilmot, Second Earl of Rochester, a pet monkey proffers a tattered page ripped from one of his master's books. The Earl, resplendent in silks, coolly awards the beast a laurel crown. "Were I...," Rochester wrote, "a spirit free, to choose for my own share/ what sort of flesh and blood I pleas'd to wear,/ I'd be a dog, a monkey or a bear,/ Or any thing but that vain animal/ Who is so proud of being rational."

For more than two centuries Rochester's notoriety as the wildest of "the merry gang" of wits who converged at Charles II's court during the 1660's overshadowed his reputation as a poet. The poetry- skeptical, parodistic, obscene and scathing- was a rediscovery of the 1920's, though John Hayward's 1926 Nonesuch edition escaped prosecution only by being limited to 1,050 copies. A scholarly biography by Vivian de Sola Pinto (1935; revised as "Enthusiast in Wit," 1962) usefully related Rochester's libertinism to Hobbesian materialism- specifically to Hobbes's doctrine that sensory experience was the only philosophical reality. Pinto pitched his claims high: "If Milton is the great poet of belief in the 17th century, Rochester is the great poet of unbelief." . . .

Rochester told the historian Gibert Burnet that "for five years together he was continually drunk; not all the while under the visible effect of it." He was repeatedly banished- and as often recalled- by the King he scurrilously lampooned. Drink made him "extravagantly pleasant"; it also led to disgraces like the smashing of the royal sundial and the brawl at Epsom in which his friend Mr. Downes was killed. Greene plausibly links the most famous of Rochester's masquerades to the aftermath of the Epsom affray: he vanished from London and a mysterious Dr. Alexander Bendo- astrologer, diviner of dreams, dispenser of beauty aids and cures for women's diseases- set up shop on Tower Hill. "Dr. Bendo's" advertisement is one of the most dazzling virtuoso pieces of 17th-century prose. In its impromptu rush of quackery and Biblical cadences, its promises of marvels and its teasing challenge to distinguish the counterfeit from the real. Greene astutely notes "the cracks in the universe of Hobbes, the disturbing doubts in his disbelief, which may have been in Rochester's mind even in the midst of his masquerade, so riddled is the broadsheet with half truths."

Dating his poems is a snare, but Rochester's Songs and his best satires- "A Ramble in St. James's Park," the "Satyr Against Reason and Mankind," "A Letter from Artemisia in the Town to Chloe in the Country," "The Maim'd Debauchee"- all seem to have been written before he turned 29. Thereafter "an embittered and thoughtful man who would die in 1680 of old age at 33," he seldom appeared at court. In his last year he debated theology with the Anglican Gilbert Burnet and underwent a religious conversion, the authenticity of which was impugned when Burnet published his account of it but which Greene, like Vivian de Sola Pinto, believes to have been genuine. "The hand of God touched him," Burnet wrote- "but," Greene characteristically adds, "it did not touch him through the rational arguments of a cleric. If God appeared at the end, it was the sudden secret appearance of a thief... without reason, an act of grace."

The 1976 Penguin edition of Greene's life of Rochester I possess is wonderfully well illustrated with four color portraits, line drawings and frontispieces. Greene demonstrates a great deal of sympathy for this drunken, lustful man, and while Rochester might be "the great poet of unbelief" the topic of religion and faith--Catholic, Puritan, and Anglican--comes up often in the pages.

Published on July 25, 2013 22:30