Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 263

August 8, 2013

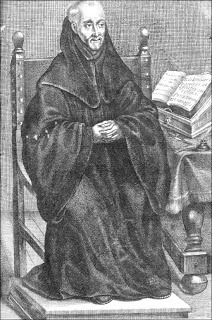

David Augustine Baker, OSB

Benedictine priest and monk (David) Augustine Baker died of the plague on August 9, 1641. He was a missionary priest in England, a spiritual director of English Benedictine nuns in exile, and a mystic, writing books on Catholic spirituality. As this site notes Father Baker, "was one of the earliest members of the newly restored English Benedictine Congregation. He has three claims on our attention. "He supervised the link between Sigebert Buckley of Westminster and the old English Congregation and the new English monks from Italy.

Benedictine priest and monk (David) Augustine Baker died of the plague on August 9, 1641. He was a missionary priest in England, a spiritual director of English Benedictine nuns in exile, and a mystic, writing books on Catholic spirituality. As this site notes Father Baker, "was one of the earliest members of the newly restored English Benedictine Congregation. He has three claims on our attention. "He supervised the link between Sigebert Buckley of Westminster and the old English Congregation and the new English monks from Italy. "He collected a huge amount of historical material to support the claim (against newer orders) that the conversion of England was from the beginning essentially Benedictine.

"He explored deep into the spiritual world of prayer, teaching many, especially among our nuns, the fruitful realities of the life of prayer. In this his influence is incalculable, and is still with us today. Apart from the language in which it is set out, which is, not unreasonably, a little dated, it is a spirituality which sits well on the more recent columns of the church's inner structure. It grew in the Counter- Reformation world, but has older roots and survives when some of the more enthusiastic accretions of the seventeenth century have largely evaporated."This blogger comments on Father Baker's spirituality and life of prayer:

Like the Fathers of the Church, Dom Augustine regarded continuous prayer as the whole purpose of monastic life; but he did not reserve contemplation to monks and nuns alone. For St Symeon the New Theologian it is as connected with holy communion as baptism is connected with conversion. Dom Augustine wrote of the solitude that is a necessary condition for contemplation:

Now this so necessary solitude can be found more perfectly and permanently in a well-ordered religious state … yet it is not confined to that state but that, in the world also, and in a secular course of life, God has oft raised and guided many souls in these perfect ways, affording them even there as much solitude and as much internal freedom of spirit as he saw was necessary to bring them to a high degree of perfection.

Just as he believed that people can be called by God to contemplation in all walks of life, so he believed that a monk can pursue his goal in any conditions imposed on him by obedience. Being sent on the Mission was not unmonastic if the monk has sufficient spiritual maturity not to be diverted from his contemplative goal. Indeed his argument with Dom Rudisind was that life in a monastery can also be a distraction from contemplation in someone who is too concerned about the externals of monastic life. I believe that, if the teaching of Dom Augustine Baker is complemented by the teaching of P. Jean-Paul de Caussade SJ with his “Abandonment to Divine Providence” and his “Sacrament of the Present Moment”, and if this is set within the context of a sound understanding of the Liturgy and, hence, of the Church, then the English Benedictine Congregation will be seen to have a common goal, a coherent doctrine how to achieve it, and a flexibility to adapt the monastic observances to whatever circumstances may arise.

Published on August 08, 2013 22:30

August 7, 2013

The Dominicans in England, Before and After

The English Reformation, of course. In honor of the feast of St. Dominic of Guzman, founder of the Order of Preachers, the Dominicans, some background on this order of friars in England. According to the Blackfriars site, the order settled first in Canterbury, but then in Oxford, establishing themselves in the intellectual center:

The English Reformation, of course. In honor of the feast of St. Dominic of Guzman, founder of the Order of Preachers, the Dominicans, some background on this order of friars in England. According to the Blackfriars site, the order settled first in Canterbury, but then in Oxford, establishing themselves in the intellectual center:When a dozen Dominican friars, led by Gilbert of Fresney, their first provincial, arrived in England on 5 August 1221, they first visited Canterbury, the ecclesiastical capital of England, then London, the political capital. They finally established their first community inside the city walls of Oxford, England’s intellectual capital, on 15 August. These friars of the Order of Preachers quickly settled into the life and teaching of the early University, which proved a good place to find new recruits. Land for a new priory just outside the city walls was provided by the generosity of the Countess of Oxford, Isabel de Bolebec.

Like the first foundation at Oxford, every house in the province was to be a centre of learning, and each formed and educated novices for the mission of preaching. Priories were soon founded in other major towns and cities, where the friars could find alms on which they had to live. As mendicants they were forbidden to own and rent properties until 1475. The friars and their houses and large churches for prayer and preaching often became known as ‘Black Friars’, because of the black cape (cappa) the brothers wear over their white habits. ‘Blackfriars Bridge’, where the medieval London Blackfriars stood on the north bank of the River Thames from 1224, and where the English parliament met more than once during the Middle Ages, is only one example. A gift of shoes in 1233 indicates that about 100 brothers lived in the London Blackfriars, the largest of the medieval communities.

The friars exercised their mission at all levels of society. Not only did they work among the most unfortunate, but they were also confessors to royalty and acted as ambassadors or diplomats. When a new priory was founded, it was normally with the help of a royal or noble benefaction. By 1275 the Province of England contained at least 76 houses, not only 39 in England, but also 23 in Ireland, 9 in Scotland, and 5 in Wales. There was also a monastery of nuns at Dartford. Before the Black Death in the fourteenth century, the Province could boast of being the largest in the Order, with a membership of around 3,000 friars. Scotland became an independent province in 1481, and Ireland in 1484.

Of course, all this was destroyed by the Dissolution of the Monasteries, when Cromwell turned his attention to the friars:

At the Reformation, there were 55 houses in England and Wales. Their visitation began in 1538, and by March 1539 all were dissolved. Those friars who did not accept appointments in the Established Church were left without a pension and had to seek a Dominican life in the priories of Europe. In disguise and using aliases, they would return to England one by one as missionaries. Some were captured, imprisoned and tortured. Community life was restored in the Province by the foundation of a priory at Bornhem, Flanders, in what is today Belgium, in 1658, by Philip (later Cardinal) Howard. He also refounded the nuns, and began a school, to which English Catholics could send their sons, and where potential friars could be formed. So many men wanted to join the Order that a second priory was required, and a house was founded first in Rome and then in Louvain.

The great restoration of the Dominican Order in England came through the efforts of Father Bede Jarrett, Provincial from 1916 to 1932. This site provides more detail. You might recall that it was at the Blackfriars in London that Queen Katherine of Aragon defended her virtue as Henry VIII's true and validly married wife. The English Heritage site notes that the Gloucester Blackfriars "is one of the most complete Dominican priories to survive from the Middle Ages in England." Dartford Priory was the only Dominican house of nuns in England, also dissolved n 1539.

Published on August 07, 2013 23:00

Father and Son Martyrs: The Feltons of Bermondsey Abbey

Today is the anniversary of the martyrdom of Blessed John Felton (executed 8 August 1570) during the reign of Elizabeth I in the aftermath of the Northern Rebellion and the publication of Regnans in excelsis by Pope St. Pius V:

Today is the anniversary of the martyrdom of Blessed John Felton (executed 8 August 1570) during the reign of Elizabeth I in the aftermath of the Northern Rebellion and the publication of Regnans in excelsis by Pope St. Pius V:Almost all of what is known about Felton's background comes from the narrative of his daughter, Frances Salisbury. The manuscript that holds her story has a blank where his age should be, but it does say that he was a wealthy man of Norfolk ancestry, who lived at Bermondsey Abbey near Southwark. He "was a man of stature little and of complexion black". His wife had been a playmate of Elizabeth I, a maid-of-honour to Queen Mary and the widow of one of Mary's auditors (a legal official of the papal court).

Felton was arrested for fixing a copy of Pope Pius V's Bull Regnans in Excelsis ("reigning on high"), excommunicating Queen Elizabeth, to the gates of the Bishop of London's palace near St. Paul's. This was a significant act of treason as the document, which released Elizabeth's subjects from their allegiance, needed to be promulgated in England before it could take legal effect. The deed brought about the end of the previous policy of tolerance towards those Catholics who were content occasionally to attend their parish church while keeping their true beliefs to themselves. . . .

[this policy had already ended, and not just with the Northern Rebellion of 1569; the fines for recusancy had been mounting because the government was becoming frustrated with how Catholics were holding out against conformity]

The law records say that the act was committed around eleven at night on 24 May 1570, but Salisbury claims it happened between two and three in the morning of the following day, the Feast of Corpus Christi. Felton had received the bulls in Calais and given one to a friend, William Mellowes of Lincoln's Inn. This copy was discovered on 25 May and after being racked, Mellowes implicated Felton, who was arrested on 26 May. Felton immediately confessed and glorified in his deed, "treasonably declar[ing] that the queen . . . ought not to be the queen of England", but he was still racked as the authorities were seeking, through his testimony, to implicate Guerau de Spes, the Ambassador of Spain, in the action. Felton was condemned on 4 August and executed by hanging four days later in St. Paul's Churchyard, London. He was cut down alive for quartering, and his daughter says that he uttered the holy name of Jesus once or twice when the hangman had his heart in his hand. He was beatified in 1886 by Pope Leo XIII.

His son, Blessed Thomas Felton, remained true to the Catholic Faith and followed in his father's footsteps to the scaffold (although at Tyburn, not St. Paul's). He was born about 1567 at Bermondsey Abbey, Surrey, was in his youth page to Lady Lovett. Afterwards he was sent to the English College at Rheims, where he received the first tonsure from the hands of the Cardinal de Guise, archbishop of Rheims, in 1583. He then entered the order of Minims, but being unable to endure its austerities he returned to England. On landing in England Fleton was arrested, brought to London, and committed to the Poultry Compter. About two years later his aunt, Mrs. Blount, obtained his release through the interest of some of her friends at court. He attempted to return to France, but was again intercepted and committed to Bridewell. After some time he regained his liberty, and made a second attempt to get back to Rheims, but was rearrested and recommitted to Bridewell, where he was put into "Little Ease" and otherwise cruelly tortured. He was brought to trial at Newgate, just after the defeat of the Spanish Armada, and was asked whether, if the Spanish forces had landed, he would have taken the part of Queen Elizabeth. His reply was that he would have taken part with God and his country. But he refused to acknowledge the queen to be the Supreme Head of the Church of England, and was accordingly condemned to death. The next day, 28 August 1588, he and another priest, named James Claxton or Clarkson, were conveyed on horseback from Bridewell to the place of execution, between Brentford and Hounslow, and were there hanged and quartered.

Like his father, he was beatified in 1886 by Pope Leo XIII.

The Minims or Order of Minim Friars were founded by St. Francis of Paola in Italy during the fifteenth century. The "austerities" mentioned above include not just the usual vows of chastity, poverty, and obedience, but a vow of a "Lenten way of life"--constant abstinence from meat and dairy products.

On the other hand, if you like Paulaner beer from Munich, that's from a former Minim friary!

Published on August 07, 2013 22:30

August 6, 2013

Saint Gilbert Keith Chesterton?

You might recall that I highlighted William Oddie's suggestion that G.K. Chesterton be the next Englishman proposed for beatification and canonization in the Catholic Church. At last weekend's annual American Chesterton Conference in Worcester, MA, Dale Ahlquist announced that he had permission from Peter John Haworth Doyle of Northampton in the UK to announce that he wants to open a cause for Chesterton's canonization. So it's not an announcement that the cause is open, but that the bishop wants to find a priest of his diocese to lead the cause.

Nevertheless, the American Chesterton Society has posted this prayer card--FOR PRIVATE DEVOTION ONLY.

First Things magazine has posted this information on their blog, and the American Chesterton Society has also issued a news release--but nothing is posted on the website of the Northampton diocese.

Nevertheless, the American Chesterton Society has posted this prayer card--FOR PRIVATE DEVOTION ONLY.

First Things magazine has posted this information on their blog, and the American Chesterton Society has also issued a news release--but nothing is posted on the website of the Northampton diocese.

Published on August 06, 2013 23:00

A Judge and Judgement: the Tomb of Sir Thomas Fleming

The main reason for this post today is the tomb of Thomas Fleming, who died on August 7, 1613: he was judge in the trial of Guy Fawkes in 1606. He and his wife are entombed in the church of St Nicholas, North Stoneham in Hampshire. According to the wikipedia article, the inscription reads:

The main reason for this post today is the tomb of Thomas Fleming, who died on August 7, 1613: he was judge in the trial of Guy Fawkes in 1606. He and his wife are entombed in the church of St Nicholas, North Stoneham in Hampshire. According to the wikipedia article, the inscription reads: In most Assvred Hope of A Blessed Resvrection, Here Lyeth Interred ye Bodie of Sir Thomas Flemyng, Knight, Lord Chief Jvstice of England; Great Was His Learning, Many Were His Virtves. He Always Feared God & God Still Blessed Him & ye Love & Favour Both of God & Man Was Daylie Upon Him. He Was In Especiall Grace & Favour With 2 Most Worthie & Virtvovs Princes Q. Elizabeth & King James. Many Offices and Dygnities Were Conferred Upon Him. He Was First Sargeant At Law, Then Recorder of London; Then Solicitor Generall to Both ye Said Princes. Then Lo: Chief Baron of ye Exchequer & after Lo: Chief Jvstice of England. All Which Places He Did Execvte With So Great Integrity, Justice & Discretion that Hys Lyfe Was Of All Good Men Desired, His Death Of All Lamented. He Was Borne at Newporte In ye Isle Of Wight, Brough Up In Learning & ye Studie Of ye Lawe. In ye 26 Yeare Of His Age He Was coopled in ye Blessed State of Matrimony To His Virtvovs Wife, ye La: Mary Fleming, With whom He Lived & Continewed In that Blessed Estate By ye Space Of 43 Yeares. Having By Her In that Tyme 15 Children, 8 Sonnes & 7 Davghters, Of Whom 2 Sonnes & 5 Davghters Died In His Life Time. And Afterwards In Ripeness of Age and Fulness of Happie yeares yt Is to Saie ye 7th Day of Avgvst 1613 in ye 69 Yeare Of His Age, He Left This Life For a Better, Leaving Also Behind Him Livinge Together With His Virtvovs Wife 6 Soones & 2 Davghters.

The memorial is called "the floating Flemings" as Thomas and Mary are depicting resting on their bent elbows. Their surviving children are depicted kneeling and praying beneath their parents--but we know they are not praying for the souls of their departed parents! More on the judge and his judgement of Fawkes here, from the parish website. The image is sourced from wikipedia commons under a Creative Commons Attribution license.

Published on August 06, 2013 22:30

August 5, 2013

John Mason Neale's Translation of Coelestis formam gloriae

In honor of the Feast of the Transfiguration of Our Lord, and in keeping with the anniversary of John Mason Neale's death, his translation of this hymn from the 1495 Sarum Breviary:

O wondrous sight! O vision fair

[originally, A type of those bright rays on high]

Of glory that the church shall share,

Which Christ upon the mountain shows,

Where brighter than the sun He glows!

From age to age the tale declares

How with the three disciples there

Where Moses and Elijah meet,

The Lord holds converse high and sweet.

The law and prophets there have place,

Two chosen witnesses of grace,

The Father’s voice from out the cloud

Proclaims His only Son aloud.

With shining face and bright array,

Christ deigns to manifest that day

What glory shall be theirs above

Who joy in God with perfect love.

And faithful hearts are raised on high

By this great vision’s mystery;

For which in joyful strains we raise

The voice of prayer, the hymn of praise.

O Father, with the eternal Son,

And Holy Spirit, ever One,

Vouchsafe to bring us by Thy grace

To see Thy glory face to face.

Published on August 05, 2013 23:00

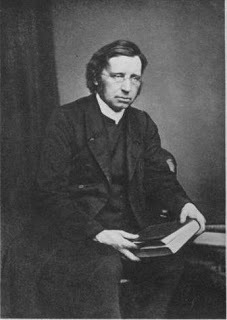

John Mason Neale, RIP

John Mason Neale died on August 6, 1866. If The Portal, the monthly magazine of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham has not included him among their "Anglican Luminaries" thus far, I'm sure they will (there is no searchable index, and I don't have time to search each issue in the archive!. According to this biography (a few excerpts):

Re: His birth and early life:

JOHN MASON NEALE was born on January 24, 1818, in London. His father, Cornelius Neale, Senior Wrangler in 1812, a strong Evangelical, was ordained priest in 1822, but died in the next year at Chiswick. His widow moved to the village of Shepperton. When he was eleven, John Mason was sent to a school at Blackheath, and writes to his former tutor at Shepperton to thank him 'for the very pretty Greek Testament,' out of which, he informs him, 'we have learnt a verse every day,' an early beginning indeed! At fifteen he went to Sherborne. There ' a tall, shy, sallow-faced boy, with thick, dusky hair tumbled above a broad forehead, and dark blue, short-sighted eyes, he moved a solitary figure among the young, happy herd.' He was no athlete, and had no qualifications for schoolboy popularity. But all his life he was an indefatigable walker, and acquired later a great love for mountains; he was also a fearless horseman. Sherborne introduced him to the real country, which, Cockney-born, he was to inhabit for the greater part of his life.

From Sherborne Neale went to Trinity College, Cambridge. Here, again, he remained largely a solitary, though recognized as the most gifted undergraduate of his time, as Keble was at Oxford. A friend and contemporary says of him: 'He was soon marked out as the cleverest man of his year, but neither his father's powers nor his teachers' instructions ever influenced him so as to give him the slightest taste for mathematics. He had through life a rooted dislike to that study. This dislike proved disastrous to his hope of graduating with distinction, for the iron rule (since obsolete), which compelled all candidates for the Classical Tripos to take mathematical honours first, resulted in his being unable to secure the prize which was universally adjudged to him by those who knew his powers.' Yet he won the Members' Prize in 1838, and soon after taking his degree was appointed assistant tutor at Downing College. Always gifted with a talent for poetry, he won the Seatonian Prize for a sacred poem no less than eleven times. He read very widely, and steeped himself in the classics and in mediaeval Latin, which laid the sure foundation for his subsequent fame as a hymnologist. Dr. Overton, in the Dictionary of Hymnology, says of him: 'It is in this species of composition that Dr. Neale's success was pre-eminent, one might almost say unique. He had all the qualifications of a good translator. He was not only an excellent classical scholar in the ordinary sense of the term, but he was positively steeped in mediaeval Latin.' Again, 'Dr. Neale's exquisite ear for melody prevented him from spoiling the rhythm by a too servile imitation of the original; while the spiritedness, which is a marked feature of all his poetry, preserved that spring and dash which is so often wanting in a translation. Unfortunately, his translations have suffered from frequent 'improvements.' But the English Hymnal, which contains a large number of them, preserves them intact.

Re: his interest in ecumenism, or more properly, reunion of Christianity:

It is as a hymnologist and controversialist that Neale has mostly been remembered. But his work for reunion was of the first importance. The word 'Catholic' was one he treasured deeply, and he would even apply it as a term of approbation to such things as woods and fields which struck him as being perfect.

Neale's three years in Madeira gave him the opportunity to start his great History of the Holy Eastern Church. To equip himself for this, he added Russian to his already profound knowledge of Greek. He also added Syriac and Georgian. While in Madeira he acquired a fluent proficiency in Portuguese. By the end of his life he had gained a knowledge of no less than twenty languages. A distinguished contemporary scholar once startled an audience with the remark: 'I'm afraid my Armenian is rather rusty!' It is just the sort of remark Neale might have made. In Madeira he became closely acquainted with Montalembert, the great Catholic writer. Besides his History Neale introduced us to the magnificent hymns of the Eastern Church by his unique translations, as also to its liturgies. His work brought him an appreciative message from the then Tsar, together with a present of £100. It also brought him into touch with Philaret, the famous Metropolitan of Moscow, as also with several Oriental scholars. In his correspondence were discovered letters from France, Russia, Holland, and Spain. In 1860, on receipt of a magnificent present of Icons, he writes: ' I had no idea until now how big a man I was in Russia.' Philaret sent him a rare book, and wrote in it: ' God's blessing and help to those who investigate the truth in the ancient books and traditions of the Church, for the peace and ultimate union of the Churches of God.' This work, so ably helped on by Neale, has indeed made great strides, and we shall not easily forget the man who so early aided them to realization.

and:

Neale was so strongly convinced of the Catholicity of the English Church that he was inclined to be anti-Roman. His experience of the Church in Madeira did not tend to impress him, and he writes in a letter from there in 1844: 'I cannot make, as Montalembert does, visible union, or as the British Critic sometimes seems to wish to do, the desire for visible union with the Chair of St. Peter the keystone, as it were, of the Church, at least not in the sense in which the Western Church has sometimes done. We Orientals take a more general view. The Rock on which the Church is built is St. Peter, but it is a Triple Rock: Antioch where he sat, Alexandria which he superintended, Rome where he suffered. You would be astounded at the weight of evidence in the Doctors of the Western Church.' When Newman left the English Church, Neale regarded it as a reaction from his former strong bias against Rome. He writes on the eve of this departure: 'I hope and believe that Newman will not leave us, but I should not despair if he did. My sheet anchor of hope for the English Church is that you cannot point out a single instance of an heretical or schismatical body which after apparent death awoke to life. The Donatists might have done it, the Copts might have done it, the Nestorians might have done it, but they have not. Why should there be such a startling anomaly to all past experience first of all exhibited in the nineteenth century?' Let us remember that the Donatists were Newman's undoing. In a letter in which Neale speaks of meeting Pusey he remarks: 'He is just the man I fancied. ... I could not wish a man to be more aesthetic than he is. How different from Newman!' Neale believed profoundly in the words of one of his poems that 'England's Church is Catholic, though England's self is not,' and he shows the bright hope of the Catholic Movement in the words: 'I am sure that, in spite of three hundred years' be-calvinization of England, there is yet a chord in most people's hearts that vibrates to Catholic truth.'

Summing up:

Neale was so many-sided that it is difficult to cram him into a pint pot. He lived in the stirring times of the Gorham Judgment and the Jerusalem bishopric question, the question that settled Manning. He wrote vigorous and telling pamphlets, but he made it a rule never to let them be sullied by lack of Christian charity. The occasions were ephemeral, but the pamphlets contain, of course, really solid and permanent matter. We have not the space to deal with them in detail. One saying of his on an important question still current may be quoted: 'Depend upon it, you are not wrong in resisting laydom. I believe with you that it will come in; but the more we resist, the less obnoxiously shall we be infested with it. ... I doubt if it is not a greater departure from discipline than the denial of the Chalice. If we are to give up everything in which we seem likely to be beaten, where shall we stop?'

There now remains all too short a space in which to deal with one of the lasting gifts Neale left to the Church, the Community of St. Margaret, East Grinstead. Like the Sisterhood at Plymouth, it arose out of the necessities of the sick. The rule was founded on the original rule of the Visitation of St. Francis de Sales, before that order became enclosed. Neale deliberately chose a grey rather than a black habit, as being more cheerful for sick people. St. Vincent de Paul provided much inspiration. Carter of Clewer and his famous Sisterhood, together with Butler of Wantage and his, supplied encouragement and example, as also did Father Benson of Cowley. Butler writes with regard to rules: 'My impression is that you have too many, especially for a beginning. Rules should shape themselves as the work grows and need occurs. With good people, such as Sisters of Mercy are likely to be, one can risk a little, and wait to buy experience.' The community started with two Sisters in 1854. They did not live in community till the next year. In June, 1856, a house close to Sackville College was taken, and the Sisters moved into it. Dr. Neale's daughter is still the Rev. Mother of the community, which now has three daughter houses (one of which is St. Saviour's Priory, Haggerston) and sixteen dependencies, including the Free Home for the Dying at Clapham, a college, school, and orphanage in Ceylon, and a house at Johannesburg. Naturally, this venture of faith added greatly to Neale's work. He writes to a Sister saying that he now gets up at five, and hopes to manage four!

Excessive work killed this remarkably gifted son of the Church at the early age of forty-eight, in 1866, very shortly after the death of Keble.

Read more here. I've often featured his hymns and translations on this blog. In this biography, it's clear to me that Neale was one of those who hoped for, as Aidan Nichols commented in his book on the Anglican Ordinariate, the conversion of the Church of England to "Catholicism". Neale didn't yet have to face the choice Nichols cites after the "rupturing of the apostolic succession by the ordination of women rendered that outcome impossible": Would they [Anglo-Catholics] be an ecclesiola, a 'little church', within a body now theologically alien to them though culturally familiar, or would they become an ecclesiola within a body that was culturally unfamiliar to them but theologically congruent?" (pp. 18-19)

Published on August 05, 2013 22:30

August 3, 2013

The English Reformation Today's One Year Anniversary

On Saturday, August 4, 2012, I began my 12-week show, "The English Reformation Today" on Radio Maria US. Almost all of the episodes are available as podcasts on the network's website here. I posted regular summaries of each week's topic on this blog, and you can explore those posts here.

As a preview of upcoming events, I'm pleased to announce that the St. Austin Review (StAR) will publish my article on Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI's legacy for England's Catholics in the September/October issue--but you'll need to be a subscriber to read the article, unless they happen to choose it as the one sample article from the issue on the magazine's website.

Also, the September on-line issue of Homiletic & Pastoral Review will include my article on Church History and Apologetics, which is readily accessible for free!

And, finally, don't forget that I'll be presenting at the Kansas Authors Club annual convention here in Wichita, Kansas. I'm scheduled for 10:00 a.m. on Saturday, October 5 on “Marketing a Non-Fiction Book to a Niche Audience: It’s Quite a F.E.A.T.” Program description:

Stephanie will describe strategies she has developed and techniques she employs to promote her non-fiction, historical work to a niche audience of readers interesting in the history of religion in England. With humility and humor, Stephanie outlines her successes and failures, offering insights and lessons learned by using the acronym F.E.A.T.: F = Finding a Publisher and an Audience (research and success); E = Establishing a Platform (broadcast, print, and on-line social media); A = Addressing Challenges and Opportunities (current events and limitations); T = Tracking down Contacts and Customers (networking and working).

I'm so disappointed that the pilgrimage to England in honor of the English Martyrs of the Reformation did not work out this year. Corporate Travel Services is still on the lookout for a suitable parish to base the pilgrimage in so they may attract enough participation to make it successful.

Published on August 03, 2013 23:00

The Annual Midwest Catholic Family Conference and Temptation

The temptation I write of, naturally, is books. The annual Midwest Catholic Family Conference always brings excellent speakers and presenters--but also, vendors with books, books, and more books--and many religious articles. (Colleges and universities come too, inviting parents and high school students to consider their higher education options, and offering promotional SWAG.) Alas, the St. John Fisher Bookstore no longer exists, but when it was among the vendors, it was hard to stay away: all the Neumann Press books (also, sadly defunct), all the Roman Catholic Books offerings, most of the Ignatius Press books, and most of the Scepter Publishers and Sophia Institute materials too.

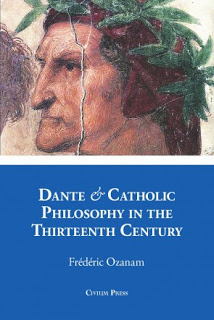

I went hoping to find two books, both from the latter two publishers: Scepter's edition of St. Thomas More's Dialogue of Comfort and Tribulation, and Sophia's new edition of Blessed John Henry Newman's meditations, with an introduction by Bishop James T. Conley, formerly of the Wichita Diocese. I found the Newman, but the proprietor of the store that should have had the More told me he left all his More books in Cincinnati! But then I found this publisher, and this intriguing book:

The work which produced this volume began when the author, only twenty years old at the time, found himself standing in the Camera della Segnatura before Raphael’s Disputa del Sacramento Among the adoring Church—popes, monks, scholars and pastors—one head stood out from all the rest, crowned not in miter or tiara, but with laurels. Why should the painter bestow such august honor on the poet exile?

The work which produced this volume began when the author, only twenty years old at the time, found himself standing in the Camera della Segnatura before Raphael’s Disputa del Sacramento Among the adoring Church—popes, monks, scholars and pastors—one head stood out from all the rest, crowned not in miter or tiara, but with laurels. Why should the painter bestow such august honor on the poet exile?

This book is an attempt to answer that question. Unlike many who comment upon the poet’s work, Ozanam stresses the fidelity of Dante to the Catholic tradition and his filial devotion to the Church. Far from the revolutionary anti-Papal anarchis found in the passages of most commentaries, the portrait which Ozanam, following Raphael’s lead, paints is the visage of aman who has set his mind on higher things and his hands on the lower:

And, yes, I succumbed to the temptation! I also met Lisa Hendey and Dan Egan, both fellow Son Rise Morning Show regulars, and Patrick Coffin from Catholic Answers Live, and many friends!

I went hoping to find two books, both from the latter two publishers: Scepter's edition of St. Thomas More's Dialogue of Comfort and Tribulation, and Sophia's new edition of Blessed John Henry Newman's meditations, with an introduction by Bishop James T. Conley, formerly of the Wichita Diocese. I found the Newman, but the proprietor of the store that should have had the More told me he left all his More books in Cincinnati! But then I found this publisher, and this intriguing book:

The work which produced this volume began when the author, only twenty years old at the time, found himself standing in the Camera della Segnatura before Raphael’s Disputa del Sacramento Among the adoring Church—popes, monks, scholars and pastors—one head stood out from all the rest, crowned not in miter or tiara, but with laurels. Why should the painter bestow such august honor on the poet exile?

The work which produced this volume began when the author, only twenty years old at the time, found himself standing in the Camera della Segnatura before Raphael’s Disputa del Sacramento Among the adoring Church—popes, monks, scholars and pastors—one head stood out from all the rest, crowned not in miter or tiara, but with laurels. Why should the painter bestow such august honor on the poet exile?This book is an attempt to answer that question. Unlike many who comment upon the poet’s work, Ozanam stresses the fidelity of Dante to the Catholic tradition and his filial devotion to the Church. Far from the revolutionary anti-Papal anarchis found in the passages of most commentaries, the portrait which Ozanam, following Raphael’s lead, paints is the visage of aman who has set his mind on higher things and his hands on the lower:

Here is a poet who appeared in a tumultuous age, who lived as if enveloped in storms. Yet, behind the moving shadows of life, he divined immutable realities. Led by reason and by faith, he outstrips time, penetrates into the invisible world, there takes possession and establishes himself as if in his native land—he who has no longer a country here below. From that lofty station, when his eyes fall upon human things, he is able to see at once the beginning and the end; consequently, he measures and judges them.Frédéric Ozanam (1813–1853) was professor of History and Literature at the Sorbonne, writing extensively on the historical contributions of Christianity to society and culture. In 1833, he founded the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul. He was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1997.

And, yes, I succumbed to the temptation! I also met Lisa Hendey and Dan Egan, both fellow Son Rise Morning Show regulars, and Patrick Coffin from Catholic Answers Live, and many friends!

Published on August 03, 2013 22:30

August 2, 2013

The Unintended English Reformation

Norman Jones published this great study in 2002: The English Reformation: Religion and Cultural Adaptation . From the back cover:

Recent debate over the English Reformation has turned around how Catholic the nation was before the Reformation. Most scholars now believe that there was little popular support for the change in religion imposed by Henry VIII. And yet, by the end of Elizabeth's reign England was clearly Protestant. It had abandoned much of its late Medieval culture and replaced it with a new formulation. This book explores how the English, over three generations, adapted to the religious changes and, in the process, radically reconstructed their culture.

Using case studies, the author explores how individuals and the institutions in which they lived and worked, such as families, universities, towns, guilds, and Inns of Court, refashioned themselves in the face of the rapid social, ideological, political, and economic changes loosed by the Reformation. Tracing these responses across three generations, the author emphasizes the way generational interaction and self-interest interrelated to adapt to new circumstances, creating, by the late sixteenth century, a multi-theological culture that exalted nationalism and valued the individual conscience.

List of Illustrations

Abbreviations

Acknowledgements

1. Post Reformation Culture

2. Choosing Reformations

3. Families and Reformations

4. Dissolutions and Opportunities

5. Redefining Communities

6. Reinventing Public Virtue

7. Learning Private Virtue

8. The Post - Reformation World View

Notes

Select Bibliography

Index

This is a fascinating study indeed which demonstrates that the unintended consequences of the English Reformation were: division and anarchy; loss of respect for authority; violence and hatred; loss of community; loss of shared virtues and consensus about behavior; greater secularization; more emphasis on individual conscience and self-interest--and an entirely changed worldview.

The English Reformation set the individual conscience completely adrift from authority outside the self, since even the individual's understanding of what Holy Scripture guided him or her to do relied entirely on his or her interpretation of what Holy Scripture guided him or her to do. The Scriptural admonitions for children to obey their parents and wives to submit to their husbands required some very fancy exigesis when the son or wife wanted to be a Protestant and the father or husband directed them to remain true to the Catholic Church--but not so much if the situation was reversed!

The dissolution of the monasteries and the chantries, the official changes in religion that effected the guilds, colleges, and other associations, all led to the abrogation of wills and bequests, and again, an increased secularization. Organizations like guilds and colleges that had had religion, prayer for the dead founders and benefactors, celebrations and services, Mass and vespers as an integral part of their organization stripped all of that away. They became mostly secular, with an annual sermon on their foundation anniversary (which had been their patron saint's feast day) and then not even that.

In each chapter as Jones looks at the changes that occurred in families, institutions and society through the state-sponsored creation of the via media, with the imposition of uniformity and the Book of Common Prayer, two issues are paramount: individual conscience (what Blessed John Henry Newman would later call "the right of self-will") and self-interest, making the individual. The entire Catholic structure of what later popes would call the Mystical Body of Christ--but which did exist in practice before the English Reformation, was dismantled. As he notes, "When conscience became the measure, it left people confused, willing to grant that individual virtue could only be determined by each individual unless it resulted in actions that damaged secular interests. . . . For many, this meant license, and for some it meant that they had to become more and more shrill in their attempts to drown out competing consciences. The little God sitting inside us, conscience, that was expected to be an infallible guide to God's will, turned out to be a Trojan horse." (p. 195)

In the chapter on "Reinventing Public Virtue", for example, Jones studies how usury, which had been condemned by the Catholic Church and by civic and canon law before the Reformation, was gradually accepted (although regulated) by the only law left, civic law. This "community sin" was taken out of English law, while local sheriffs and officials went after individuals who used blasphemous language. Queen Elizabeth I was never charged, but she certainly violated those laws against blasphemous language, as she often swore "by the mass, by God, by Christ and by many parts of Christ's body, and by saints, faith, troth, and other things. In 1585 William Fuller dared to tell the Queen that her swearing was an evil example to her subjects, encouraging adultery." (p. 167). As Jones notes, she probably replied, "by God's teeth I will not!" stop swearing.

In the final chapter, Jones summarizes this argument by presenting us with two men in contrast: from before the English Reformation, Sir Thomas More; from after the English Reformation, Sir Francis Bacon. As he notes, "they belonged to different mental worlds. They had different conceptions of the self, different ideas of a person's place and duties, different perceptions of how salvation worked, different economic values, and different political values."

In some ways, Norman Jones seems to have anticipated what Brad Gregory would examine in his 2012 study, The Unintended Reformation: How a Religious Revolution Secularized Society . Norman Jones is no apologist for the world view before the English Reformation, as Gregory is for the Catholic world view in Europe before the Reformation. Gregory calls for reform in his study, but Jones is just presenting an excellent overview of social and cultural change. In a way, reading his book reminded me of Eric Ive's The Reformation Experience: Life in the Turbulent 16th Century ; it seems to me that Jones succeeded where Ives failed to describe how people reacted and experienced the Reformation in England; using case studies and describing individual lives, Jones demonstrates the tremendous forces of change in the sixteenth century.

Published on August 02, 2013 22:30