Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 262

August 16, 2013

Anne Boleyn's Execution: Why with a Sword?

Leanda de Lisle explains why, in

The Spectator

:

With his wife, Anne Boleyn, in the Tower, Henry VIII considered every detail of her coming death, poring over plans for the scaffold. As he did so he made a unique decision. Anne, alone among all victims of the Tudors, was to be beheaded with a sword and not the traditional axe. The question that has, until now, remained unanswered is — why?

Historians have suggested that Henry chose the sword because Anne had spent time in France, where the nobility were executed this way, or because it offered a more dignified end. But Henry did not care about Anne’s feelings. Anne was told she was to be beheaded on the morning of 18 May, and then kept waiting until noon before being told she was to die the next day. At the root of Henry’s decision was Henry thinking not about Anne, but about himself.

That last sentence is the key to de Lisle's explanation: she connects Henry's concern with his hurt pride and reputation, disclosed in the trials of his queen and her courtiers with the image of Camelot:

In Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, Guinevere was sentenced to death by burning. Henry decided Anne would be beheaded with a sword — the symbol of Camelot, of a rightful king, and of masculinity. Historians argue over whether Anne was really guilty of adultery, and whether Henry or Cromwell was more responsible for her destruction. But the choice of a sword to kill Anne reflects one certain fact: Henry’s overweening vanity and self-righteousness.

What do you think of her explanation?

With his wife, Anne Boleyn, in the Tower, Henry VIII considered every detail of her coming death, poring over plans for the scaffold. As he did so he made a unique decision. Anne, alone among all victims of the Tudors, was to be beheaded with a sword and not the traditional axe. The question that has, until now, remained unanswered is — why?

Historians have suggested that Henry chose the sword because Anne had spent time in France, where the nobility were executed this way, or because it offered a more dignified end. But Henry did not care about Anne’s feelings. Anne was told she was to be beheaded on the morning of 18 May, and then kept waiting until noon before being told she was to die the next day. At the root of Henry’s decision was Henry thinking not about Anne, but about himself.

That last sentence is the key to de Lisle's explanation: she connects Henry's concern with his hurt pride and reputation, disclosed in the trials of his queen and her courtiers with the image of Camelot:

In Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, Guinevere was sentenced to death by burning. Henry decided Anne would be beheaded with a sword — the symbol of Camelot, of a rightful king, and of masculinity. Historians argue over whether Anne was really guilty of adultery, and whether Henry or Cromwell was more responsible for her destruction. But the choice of a sword to kill Anne reflects one certain fact: Henry’s overweening vanity and self-righteousness.

What do you think of her explanation?

Published on August 16, 2013 22:30

August 15, 2013

The Everlasting Man and an Odious Assignment

Our Wichita, Kansas chapter of the American Chesterton Society meets tonight at Eighth Day Books at 6:30. If you are in Wichita, like Chesterton, bookstores, and refreshments, it's the place to be tonight. Except for the assignment we've been given. It's an odious assignment--it's an impossible assignment--it's an incredible assignment: Pick ONE of my favorite passages from

The Everlasting Man

!

Our Wichita, Kansas chapter of the American Chesterton Society meets tonight at Eighth Day Books at 6:30. If you are in Wichita, like Chesterton, bookstores, and refreshments, it's the place to be tonight. Except for the assignment we've been given. It's an odious assignment--it's an impossible assignment--it's an incredible assignment: Pick ONE of my favorite passages from

The Everlasting Man

! Quoting Chesterton is like quoting Blessed John Henry Newman: you may find the pithy statement you want to cite, but you have to surround it by all the context before and after. In their different ways, Chesterton and Newman advance their arguments so precisely (if not always concisely) that the entire context is essential. That's why people can get in trouble when they cherry pick statements from Newman. Some have used his statement about change to justify change he never intended ("In a higher world it is otherwise, but here below to live is to change, and to be perfect is to have changed often.")--as though he advocated change for change sake. Primarily, they ignore the sentence that precedes it:

But whatever be the risk of corruption from intercourse with the world around, such a risk must be encountered; if a great idea is duly to be understood, and much more if it is to be fully exhibited. It is elicited and expanded by trial, and battles into perfection and supremacy. Nor does it escape the collision of opinion even in its earlier years, nor does it remain truer to itself, and with a better claim to be considered one and the same, though externally protected from vicissitude and change. It is indeed sometimes said that the stream is clearest near the spring. Whatever use may fairly be made of this image, it does not apply to the history of a philosophy or belief, which on the contrary is more equable, and purer, and stronger, when its bed has become deep, and broad, and full. It necessarily rises out of an existing state of things, and for a time savours of the soil. Its vital element needs disengaging from what is foreign and temporary, and is employed in efforts after freedom which become wore vigorous and hopeful as its years increase. Its beginnings are no measure of its capabilities, nor of its scope. At first no one knows what it is, or what it is worth. It remains perhaps for a time quiescent; it tries, as it were, its limbs, and proves the ground under it, and feels its way. From time to time it makes essays which fail, and are in consequence abandoned. It seems in suspense which way to go; it wavers, and at length strikes out in one definite direction. In time it enters upon strange territory; points of controversy alter their bearing; parties rise and around it; dangers and hopes appear in new relations; and old principles reappear under new forms. It changes with them in order to remain the same. (From The Development of Doctrine , chapter 1, section 1)

But if I must choose one of my favorite passages from The Everlasting Man , I suppose it could be this from Part 2, Chapter 3: The Strangest Story in the World:

Every attempt to amplify that story has diminished it. The task has been attempted by many men of real genius and eloquence as well as by only too many vulgar sentimentalists and self-conscious rhetoricians. The tale has been retold with patronizing pathos by elegant skeptics and with fluent enthusiasm by boisterous best-sellers. It will not be retold here. The grinding power of the plain words of the Gospel story is like the power of millstones; and those who can read them simply enough will feel as if rocks had been rolled upon them. Criticism is only words about words; and of what use are words about such words as these? What is the use of wordpainting about the dark garden filled suddenly with torchlight and furious faces? 'Are you come out with swords and staves as against a robber? All day I sat in your temple teaching, and you took me not.' Can anything be added to the massive and gathered restraint of that irony; like a great wave lifted to the sky and refusing to fall? 'Daughters of Jerusalem, weep not for me but weep for yourselves and for your children!

As the High Priest asked what further need he had of witnesses, we might well ask what further need we have of words. Peter in a panic repudiated him: 'and immediately the cock crew; and Jesus looked upon Peter, and Peter went out and wept bitterly.' Has anyone any further remarks to offer? Just before the murder he prayed for all the murderous race of men saying 'They know not what they do'; is there anything to say to that, except that we know as little what we say? Is there any need to repeat and spin out the story of how the tragedy trailed up the Via Dolorosa and how they threw him in haphazard with two thieves in one of the ordinary batches of execution; and how in all that horror and howling wilderness of desertion one voice spoke in homage, a startling voice from the very last place where it was looked for, the gibbet of the criminal; and he said to that nameless ruffian, 'This night shalt thou be with me in Paradise'? Is there anything to put after that but a full-stop? Or is anyone prepared to answer adequately that farewell gesture to all flesh which created for his Mother a new Son?

As the High Priest asked what further need he had of witnesses, we might well ask what further need we have of words. Peter in a panic repudiated him: 'and immediately the cock crew; and Jesus looked upon Peter, and Peter went out and wept bitterly.' Has anyone any further remarks to offer? Just before the murder he prayed for all the murderous race of men saying 'They know not what they do'; is there anything to say to that, except that we know as little what we say? Is there any need to repeat and spin out the story of how the tragedy trailed up the Via Dolorosa and how they threw him in haphazard with two thieves in one of the ordinary batches of execution; and how in all that horror and howling wilderness of desertion one voice spoke in homage, a startling voice from the very last place where it was looked for, the gibbet of the criminal; and he said to that nameless ruffian, 'This night shalt thou be with me in Paradise'? Is there anything to put after that but a full-stop? Or is anyone prepared to answer adequately that farewell gesture to all flesh which created for his Mother a new Son?But I would want to go on with the next brilliance of Chesterton:

It is more within my powers, and here more immediately to my purpose, to point out that in that scene were symbolically gathered all the human forces that have been vaguely sketched in this story. As kings and philosophers and the popular element had been symbolically present at his birth, so they were more practically concerned in his death; and with that we come face to face with the essential fact to be realized. All the great groups that stood about the Cross represent in one way or another the great historical truth of the time; that the world could not save itself. Man could do no more. Rome and Jerusalem and Athens and everything else were going down like a sea turned into a slow cataract. Externally indeed the ancient world was still at its strongest, it is always at that moment that the inmost weakness begins. But in order to understand that weakness we must repeat what has been said more than once; that it was not the weakness of a thing originally weak. It was emphatically the strength of the world that was turned to weakness and the wisdom of the world that was turned to folly.

In this story of Good Friday it is the best things in the world that are at their worst. That is what really shows us the world at its worst. It was, for instance, the priests of a true monotheism and the soldiers of an international civilization. Rome, the legend, founded upon fallen Troy and triumphant over fallen Carthage, had stood for a heroism which was the nearest that any pagan ever came to chivalry. Rome had defended the household gods and the human decencies against the ogres of Africa and the hermaphrodite monstrosities of Greece. But in the lightning flash of this incident, we see great Rome, the imperial republic, going downward under her Lucretian doom. Scepticism has eaten away even the confident sanity of the conquerors of the world. He who is enthroned to say what is justice can only ask, 'What is truth?' So in that drama which decided the whole fate of antiquity, one of the central figures is fixed in what seems the reverse of his true role. Rome was almost another name for responsibility . Yet he stands forever as a sort of rocking statue of the irresponsible. Man could do no more. Even the practical bad become the impracticable. Standing between the pillars of his own judgment-seat, a Roman had washed his hands of the world. There too were the priests of that pure and original truth that was behind all the mythologies like the sky behind the clouds. It was the most important truth in the world; and even that could not save the world. Perhaps there is something overpowering in pure personal theism; like seeing the sun and moon and sky come together to form one staring face. Perhaps the truth is too tremendous when not broken by some intermediaries divine or human; perhaps it is merely too pure and far away.

See what I mean? Do you have a favorite passage from The Everlasting Man--or would you end up quoting most of any chapter like me?

Since that day it has never been quite enough to say that God is in his heaven and all is right with the world; since the rumor that God had left his heavens to set it right.

Published on August 15, 2013 22:30

August 14, 2013

Hymns and Music for the Feast of the Assumption of Our Lady

This site has a great list of appropriate hymns and musical selection for today's feast, including this hymn by Father John Lingard:

This site has a great list of appropriate hymns and musical selection for today's feast, including this hymn by Father John Lingard: Hail, Queen of heaven, the ocean star,

Guide of the wanderer here below,

Thrown on life's surge, we claim thy care,

Save us from peril and from woe.

Mother of Christ, Star of the sea

Pray for the wanderer, pray for me.

O gentle, chaste, and spotless Maid,

We sinners make our prayers through thee;

Remind thy Son that He has paid

The price of our iniquity.

Virgin most pure, Star of the sea,

Pray for the sinner, pray for me.

And while to Him Who reigns above

In Godhead one, in Persons three,

The Source of life, of grace, of love,

Homage we pay on bended knee:

Do thou, bright Queen, Star of the sea,

Pray for thy children, pray for me.

Father John Lingard (5 February 1771 – 17 July 1851), of course, was the Catholic priest who wrote the great eight-volume work The History of England that did so much to overturn the Whig view of English history. More on the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the English Reformation here.

Published on August 14, 2013 22:30

August 13, 2013

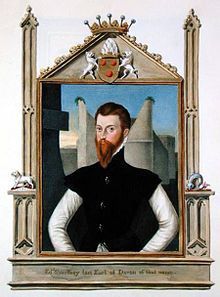

Catherine of York, her Son, and her Grandson

Catherine of York, second from the right, was born on August 14, 1479. She was the ninth child and sixth daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. In 1495, she married the eldest son and heir-apparent of Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon, William Courtenay. Her sister, Elizabeth of York married Henry VII, but for a time William Courtenay was under a cloud during the reign of Henry VII after Elizabeth died. Restored to favor by Henry VIII, his attainder was removed, and Catherine and William's son Henry was in favor at Court also, participating in the great Field of the Cloth of Gold meeting between Henry and Francis I of France, for example.

Catherine of York, second from the right, was born on August 14, 1479. She was the ninth child and sixth daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. In 1495, she married the eldest son and heir-apparent of Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon, William Courtenay. Her sister, Elizabeth of York married Henry VII, but for a time William Courtenay was under a cloud during the reign of Henry VII after Elizabeth died. Restored to favor by Henry VIII, his attainder was removed, and Catherine and William's son Henry was in favor at Court also, participating in the great Field of the Cloth of Gold meeting between Henry and Francis I of France, for example.Catherine and William's son, Henry Courtenay, 1st Marquess of Exeter was the father of Edward Courtenay, the 1st Earl of Devon (second creation). The Courtenay family held great power in the west of England as well as an excellent Yorkist claim to the throne, and, although Henry Courtenay benefitted from the Dissolution of the Monasteries, he otherwise opposed Thomas Cromwell. Nevertheless, he had supported Henry VIII in his dynastic efforts even as his wife remained a close friend to Katherine of Aragon (and even of Katherine Barton, the Nun of Kent!). The whole family, Henry, Edward and Gertrude, Henry's second wife and Edwards's mother were imprisoned in the Tower of London in 1538. They were suspected in the Exeter Conspiracy, which also brought down the Countess of Salisbury, Margaret Pole's family--Gertrude and Margaret were together in the Tower for sometime. [Note that Margaret Pole was also born on August 14, in 1473; another strong Yorkist claimant to the throne.] Henry Courtenay was beheaded on Tower Hill on 9 January 1539; his wife was released in 1540 (and Margaret Pole was executed in 1541). Imprisoned during the reign of Henry VIII, Edward was not included in the amnesty announced by Edward VI, and thus remained in the Tower, mostly in solitary confinement, for almost 15 years.

When Mary I came to the throne, Edward was released. Stephen Gardiner, the former--and restored--Bishop of Winchester had mentored the young man while in prison, and continued as his champion. Edward hoped to marry the queen

, maintained a princely household in prospect of those hopes, and may have even participated in the Wyatt Rebellion when Mary's betrothal to Philip of Spain dashed them. He also reached out to Mary's half-sister Elizabeth, in the hopes of combining the House of Tudor and the House of York in even greater unity. His role in the Wyatt Rebellion was never proved, so he was exiled, after first enduring imprisonment again in the Tower of London and then in Fotheringay. He died suddenly on September 18, 1556 in Padua after catching a chill while hunting. His mother, who had become one of Mary's ladies-in-waiting, died two years later. She had remained a devout and devoted Catholic throughout the religious changes of Henry VIII and Edward VI's reigns.

, maintained a princely household in prospect of those hopes, and may have even participated in the Wyatt Rebellion when Mary's betrothal to Philip of Spain dashed them. He also reached out to Mary's half-sister Elizabeth, in the hopes of combining the House of Tudor and the House of York in even greater unity. His role in the Wyatt Rebellion was never proved, so he was exiled, after first enduring imprisonment again in the Tower of London and then in Fotheringay. He died suddenly on September 18, 1556 in Padua after catching a chill while hunting. His mother, who had become one of Mary's ladies-in-waiting, died two years later. She had remained a devout and devoted Catholic throughout the religious changes of Henry VIII and Edward VI's reigns.Part of the lesson of this family story is, of course, the danger those royal princes and princesses of the House of York posed to the Tudor dynasty, even after Henry VII merged the two houses through marriage to Elizabeth of York. With putative claimants to the throne opposing some aspect of Tudor rule (like the changes in religion; a foreign marriage), the Tudors reacted in succession (Henry VII, Henry VIII, and even Mary I) with imprisonment, attainder, exile, and even execution.

Published on August 13, 2013 23:00

St. Maximilian Kolbe and the Militia of the Immaculata

Today is the feast of St. Maximilian Kolbe, the Auschwitz martyr: more about him and his martyrdom here and here.

Today is the feast of St. Maximilian Kolbe, the Auschwitz martyr: more about him and his martyrdom here and here. My true reason for posting about him is a conference I plan to attend next month associated with his Militia of the Immaculata, at which Dale Ahlquist of the American Chesterton Society will be the featured speaker. I don't know what his topic will be, but surely he'll find some unity between the two journalists: St. Maximilian and G.K. Chesterton:

Dale Ahlquist, host of EWTN’s “G.K. Chesterton: The Apostle of Common Sense,” will be the featured speaker at the Militia Immaculata Midwest Conference, Sept 6-7, at the Savior Pastoral Center in Kansas City, Kan. Also speaking will be Fr. Stephen McKinley, rector of the National Shrine of St. Maximilian Kolbe. The weekend includes concerts, Mass, benediction, and the Divine Mercy Chaplet. For information about registration, accommodations, and meals, email Christine Rossi at immaculata8@kc.rr.com.

St. Maximilian Kolbe is the patron saint of media communications!

Here's a link to the flyer and more info on the conference location.

Published on August 13, 2013 22:30

August 12, 2013

Connections Between Martyrs: Inspiration and Imitation

I've written before about how St. Edmund Campion's trial and passion influenced both St. Henry Walpole and St. Philip Howard--and how Walpole imitated Campion so completely that he endured torture, engaged in theological disputations, and suffered martyrdom just like his model. Today's martyr, Blessed William Freeman, witnessed the execution of Blessed Edward Stransham, and it changed his life:

He was born in East Riding, Yorkshire, he studied at Oxford and was converted to Catholicism in 1586 by the martyrdom of Blessed Edward Stransahm at Tyburn. (His parents were recusant Catholics but he had conformed to the established church.) He went to Reims, France, where he was ordained in 1587. He went back to England the following year, and labored for the English mission in Worcestershire and Warwickshire until arrested in early 1595. Seven months later he was hanged, drawn, and quartered at Warwick on August 13. William was beatified in 1929.

Blessed Edward Stransham was born at Oxford about 1554; suffered at Tyburn, 21 January, 1586. He was educated at St. John's College, Oxford, becoming B.A. in 1575-6; arrived at Douai in 1577, and went with the college to Reims in 1578, whence he came back to England owing to illness. In 1579, however, he returned to Reims, and was ordained priest at Soissons in Dec., 1580. He left for England, 30 June, 1581, with his fellow-martyr, Nicholas Woodfen, of London Diocese, ordained priest at Reims, 25 March, 1581. In 1583 Stransham came back to Reims with twelve Oxford converts. After five months there he went to Paris, where he remained about eighteen months at death's door from consumption. He was arrested in Bishopgate Street Without, London, 17 July, 1585, while saying Mass, and was condemned at the next assizes for being a priest.

He was born in East Riding, Yorkshire, he studied at Oxford and was converted to Catholicism in 1586 by the martyrdom of Blessed Edward Stransahm at Tyburn. (His parents were recusant Catholics but he had conformed to the established church.) He went to Reims, France, where he was ordained in 1587. He went back to England the following year, and labored for the English mission in Worcestershire and Warwickshire until arrested in early 1595. Seven months later he was hanged, drawn, and quartered at Warwick on August 13. William was beatified in 1929.

Blessed Edward Stransham was born at Oxford about 1554; suffered at Tyburn, 21 January, 1586. He was educated at St. John's College, Oxford, becoming B.A. in 1575-6; arrived at Douai in 1577, and went with the college to Reims in 1578, whence he came back to England owing to illness. In 1579, however, he returned to Reims, and was ordained priest at Soissons in Dec., 1580. He left for England, 30 June, 1581, with his fellow-martyr, Nicholas Woodfen, of London Diocese, ordained priest at Reims, 25 March, 1581. In 1583 Stransham came back to Reims with twelve Oxford converts. After five months there he went to Paris, where he remained about eighteen months at death's door from consumption. He was arrested in Bishopgate Street Without, London, 17 July, 1585, while saying Mass, and was condemned at the next assizes for being a priest.

Published on August 12, 2013 23:00

New Biography of Edmund Burke

Political philosophy and history are not my strong suits, but this biography of the founder of political conservatism does sound worthwhile (from

The Catholic Herald

):

Political philosophy and history are not my strong suits, but this biography of the founder of political conservatism does sound worthwhile (from

The Catholic Herald

):Publishing is often about timing, and the praise rightly lumped on Jesse Norman’s new biography reflects the fact that our political discourse has for too long had a Burke-shaped hole. As the author says in the second part of the book, which focuses on the politician’s ideas, Burke’s reputation has gone through boom and bust since his death in 1797, but the last few years have been lean ones. Now, with the current crisis of liberalism, both social and economic, he suggests that Burke is due a comeback, and not necessarily just on the Right.

Born in Dublin in 1729, Burke came from a mixed marriage. It was through his Catholic mother, Mary, that he developed his instinctive sympathy for the plight of the country’s mostly poor majority. His relationship with his Protestant father, Richard, seemed to have been difficult, although he did pay for Edmund to attend Trinity College Dublin and then the Middle Temple in London.

Burke arrived in the Great Wen at a time when clubs were flowering, and these played a crucial part in the development of British politics and capitalism (in contrast, the French regime discouraged them as potential conspiratorial). Burke’s was simply called The Club, and met from 1764 in the Turk’s Head tavern in Soho. Among its nine founding members were Burke himself, Joshua Reynolds, Oliver Goldsmith and Samuel Johnson. That’s some fantasy dinner party. And let’s not forget Burke’s Edinburgh connections: on a visit to London David Hume gave him a copy of The Theory of Moral Sentiments by Adam Smith. . . .

Throughout this period, and until the French Revolution, Burke was not recognisably “Right-wing”, as it would later be called. He supported Catholic emancipation and argued in favour of conciliation with the American colonies. Burke was not against all change, just extreme change. As he wrote in a 1779 letter: “Moderation is a virtue not only amiable but powerful. It is a disposing, arranging, conciliating, cementing virtue.” In Norman’s words: “For radical change to be genuinely worthwhile, it must bring overwhelming social benefit, or be the product of the most extreme necessity.”

The central theme of Burkean thought would, of course, come to the fore in his Reflections on the Revolution in France, written in the style of a letter to the pro-revolutionary Whig clubs in London. An instant bestseller, although outsold by Thomas Paine’s counterblast Rights of Man, it articulated many conservative principles. Burke believed in liberty, compassion, in helping the poor and tolerance, but he was opposed to abstract ideas, which he believed had brought disaster to France. As he wrote in A Letter to the Sheriffs of Bristol: “What is the use of discussing a man’s abstract right to food or medicine? The question is upon the method of procuring them and administering them… I shall always advise to call in aid of the farmer and the physician, rather than the professor of metaphysics.”

More about the book here from the publisher, Basic Books.

Published on August 12, 2013 22:30

August 11, 2013

Blessed Pope Innocent XI and James II

Blessed Pope Innocent XI died on August 12, 1689. His papacy is known for his efforts to reform and simplify life in the Vatican and throughout the Church. He was also an opponent of King Louis XIV's Gallicanism and absolutism. As the

Catholic Encyclopedia

tells it, that opposition spread to concerns about King James II's "autocratic" reign in England:

Blessed Pope Innocent XI died on August 12, 1689. His papacy is known for his efforts to reform and simplify life in the Vatican and throughout the Church. He was also an opponent of King Louis XIV's Gallicanism and absolutism. As the

Catholic Encyclopedia

tells it, that opposition spread to concerns about King James II's "autocratic" reign in England:The whole pontificate of Innocent XI is marked by a continuous struggle with the absolutism of King Louis XIV of France. . . . All the efforts of Innocent XI to induce King Louis to respect the rights of the Church were useless. . . . Innocent XI did not approve the imprudent manner in which James II attempted to restore Catholicism in England. He also repeatedly expressed his displeasure at the support which James II gave to the autocratic King Louis XIV in his measures hostile to the Church. It is, therefore, not surprising that Innocent XI had little sympathy for the Catholic King of England, and that he did not assist him in his hour of trial. There is, however, no ground for the accusation that Innocent XI was informed of the designs which William of Orange had upon England, much less that he supported him in the overthrow of James II.

Of course, popes are not impeccable; they can err in political and strategic matters. Blessed Pope Innocent XI was either misinformed or unaware that James II was pursuing freedom of conscience in England through Parliamentary elections and that he had the backing of many other Christians and even William Penn, the Quaker.

As this blogger sees it:

In the north there were more problems. Catholic hopes had soared when King Charles II of Britain converted on his deathbed and was succeeded by his openly Catholic brother King James II. The Pope advised the new King of England, Scotland and Ireland to move slowly and carefully, knowing that the English had developed a paranoid fear of Catholics, before trying to restore religious freedom to Catholics and dissenting Protestants. However, James II was tied by blood and money to the King of France and he paid no attention to the warnings of Innocent XI. He went ahead with his program of religious freedom, British Protestants were terrified and James was promptly overthrown by a Protestant coup in concert with a Dutch invasion. The chance for a Catholic revival in Britain had been lost and Pope Innocent XI, whose opposition to Louis XIV had put him on the generally Protestant side of that conflict, died only the next year in June of 1689.

The image of Pope Innocent XI depends a great deal on who is painting the picture. Many British and French Catholics still have a little lingering dislike of him. In fact, more than 50 years after his death French cardinals still blocked efforts to canonize the pontiff in 1744. It was not until 1956 that the Pope was declared Blessed Innocent XI and a declaration on his sainthood seems unlikely. However, despite the considerable opposition he aroused, it was mostly due to his staunch defense of the independence of the Church. He was not a lavish pontiff and left the treasury in surprisingly good shape, he was sincerely and devoutly religious and committed to cleaning up the Church and defending Christianity. All in all, a great man.

Published on August 11, 2013 22:30

August 9, 2013

Crime, Torture and Punishment in the 16th Century

Peter Marshall reviews this new book on torture and execution as practiced in Nuremburg, Germany for the Literary Review :

This is a marvellous book about a fascinating subject. It is, in a sense, a portrait of a serial killer. Frantz Schmidt was employed between 1578 and 1618 as the official executioner (and torturer) of the prosperous German city of Nuremberg. Over the course of his career he personally despatched 394 people, and flogged, branded or otherwise maimed many hundreds more. His life is also a tale of honour, duty and a lasting quest for meaning and redemption.

The penal regimes of pre-modern European states were harsh and violent, heavy on deterrence and the symbolism of retribution. Towns such as Nuremberg needed professional executioners to deal with an ever-present threat of criminality through the public infliction of capital and corporal sentences. Punishing malefactors with lengthy periods of incarceration was an idea for the future, and would probably have struck 16th-century people as unnecessarily cruel. Methods ranged from execution with the sword (the most honourable) to hanging (the least), and from the relatively quick and merciful to the dreadful penalty of staking a person to the ground and breaking their limbs one after the other with a heavy cartwheel. This was not a world of mindless violence: the punishments Schmidt imposed were carefully prescribed by the city authorities, down to the number of 'nips' (pieces of flesh torn from the limbs with red-hot tongs) convicts were to receive on their way to the gallows.

This gruesome regimen can be reconstructed because, over the course of 45 years, Schmidt kept a personal journal - not a diary in anything like the modern sense, but a usually terse and impersonal chronological record of all the punishments he had inflicted, including some details of the crimes behind them. The journal is not a new discovery (a version of it was printed as long ago as 1801), but Joel Harrington, drawing on a previously unused, near-contemporary copy, is the first historian to realise its full potential. The source lends itself to a social history of crime and punishment, but Harrington also attempts something more interesting and ambitious: to enter imaginatively into the world-view of its compiler and construct a rounded portrait of a personality and a life. Cleverly, he weaves Schmidt's own words wherever possible into his historical narrative, placing them in italics to let us identify what he has reported and what the author has conjectured or imaginatively inferred (invariably pitched pleasingly between excessive caution and undue presumption). It is a virtuoso performance. Harrington is able to draw on a range of ancillary documents, but this is the best example of making a single, apparently unpromising historical source sing since Eamon Duffy breathed life into a set of dusty English churchwardens' accounts in The Voices of Morebath.

Macmillan, the U.S. publisher, provides some excerpts and other material here. A couple of years ago, I corresponded with Professor Frank W. Barlow of Mount Holyoke College, who is at work on a biography of Richard Topcliffe. I really doubt that Topcliffe would have kept such an impersonal journal of his work of pursuing and torturing Catholic priests. From all that I've read of Topcliffe he took personal satisfaction in capturing priests like St. Robert Southwell and may have even enjoyed inflicting pain.

Published on August 09, 2013 23:00

William Oddie on Chesterton's Cause

From

The Catholic Herald

:

Many, many people have prayed, for many years, for the opening of this Cause, without any official response. Now we seem to have one. The Bishop of Northampton (the relevant authority, since Chesterton’s home town, Beaconsfield, is in his diocese), has given Martin Thompson, of the Chesterton Society (with whom he has had a prolonged conversation on the matter), permission to say that he “is sympathetic to our wishes and is seeking a suitable cleric to begin an investigation into the potential for opening a cause for [G K] Chesterton”. So he has not yet opened an official Cause: but he has begun the necessary preliminaries without which no Cause could be opened. This isn’t yet the end of the long years of prayer for a Cause to be officially estabished: but to adapt and slightly reverse Churchill’s famous phrase, it is the beginning of the end, and not simply the end of the beginning (the beginning was ended years ago).

After that Chestertonian turn of phrase, Oddie quotes J.J. Scarisbrick, the Catholic historian and pro-life leader:

After that Chestertonian turn of phrase, Oddie quotes J.J. Scarisbrick, the Catholic historian and pro-life leader:

“We all know,” he replied, “that he was an enormously good man as well as an enormous one. My point is that he was more than that. There was a special integrity and blamelessness about him, a special devotion to the good and to justice … Above all, there was that breathtaking, intuitive (almost angelic) possession of the Truth and awareness of the supernatural which only a truly holy person can enjoy. This was the gift of heroic intelligence and understanding – and of heroic prophecy. He was a giant, spiritually as well as physically. Has there ever been anyone quite like him in Catholic history?”

And then he cites one of the qualities I've read about often--how Chesterton could disagree with someone's ideas without attacking the person (something we need so much today):

Chesterton, like many great saints (Newman springs irresistibly to mind) was a controversialist in his bones. But no matter how combatively he argued, as Belloc wrote after his death, “he seemed always to be in a mood not only of comprehension for his opponent but of admiration for some quality in him… it was this in him which made him, with other qualities, so universally beloved.” This combination of combativeness with charity was a quality that Chesterton shared with other holy men; it is, indeed, one of the reasons he understood them so well, a clear example of what is termed “connaturality”, the faculty by which one holy man has a special insight into the mind and heart of another; St Thomas Aquinas’s huge productivity, he wrote, could not have been achieved “if he had not been thinking even when he was not writing; but above all thinking combatively. This, in his case, certainly did not mean bitterly or spitefully or uncharitably; but it did mean combatively. As a matter of fact, it is generally the man who is not ready to argue, who is ready to sneer. That is why, in recent literature, there has been so little argument and so much sneering.”

Read the rest here. I have just been reading about the historian J.J. Scarisbrick and his pro-life efforts in Edward Short's new book Culture and Abortion . I had not realized the great biographer of Henry VIII and one of the early English Reformation revisionist historians was the founder of a comprehensive pro-life organization! Mr. Short sent me a copy of Culture and Abortion, his book of essays from Gracewing Publishers: In Christifideles Laici (1988), Pope John Paul II exhorts his readers to recognize that "The inviolability of the person, which is a reflection of the absolute inviolability of God, finds its primary and fundamental expression in the inviolability of human life." For this great champion of life, "the common outcry, which is justly made on behalf of human rights ... the right to health, to home, to work, to family, to culture-is false and illusory if the right to life, the most basic and fundamental right and the condition for all other personal rights, is not defended with maximum determination." This is the conviction that prompted Edward Short to write Culture and Abortion, a study which looks at how our own culture betrays the inviolability of life by invoking what feminists call 'reproductive rights' to justify killing children in the womb. Examining the scourge of abortion from a cultural perspective, Edward Short draws on history, literature and the encyclicals of popes to show how defending the right to life can help us to reaffirm an understanding of culture that is based not on human pride or human power but on what Pope Paul II calls the "civilization of life and love." Wide-ranging and incisive, Culture and Abortion takes a fresh and provocative look at the often unacknowledged evil that continues to define our culture of death. Mr. Short has asked me for my honest opinion about his new book and I will offer it gladly soon!

In Christifideles Laici (1988), Pope John Paul II exhorts his readers to recognize that "The inviolability of the person, which is a reflection of the absolute inviolability of God, finds its primary and fundamental expression in the inviolability of human life." For this great champion of life, "the common outcry, which is justly made on behalf of human rights ... the right to health, to home, to work, to family, to culture-is false and illusory if the right to life, the most basic and fundamental right and the condition for all other personal rights, is not defended with maximum determination." This is the conviction that prompted Edward Short to write Culture and Abortion, a study which looks at how our own culture betrays the inviolability of life by invoking what feminists call 'reproductive rights' to justify killing children in the womb. Examining the scourge of abortion from a cultural perspective, Edward Short draws on history, literature and the encyclicals of popes to show how defending the right to life can help us to reaffirm an understanding of culture that is based not on human pride or human power but on what Pope Paul II calls the "civilization of life and love." Wide-ranging and incisive, Culture and Abortion takes a fresh and provocative look at the often unacknowledged evil that continues to define our culture of death. Mr. Short has asked me for my honest opinion about his new book and I will offer it gladly soon!

Many, many people have prayed, for many years, for the opening of this Cause, without any official response. Now we seem to have one. The Bishop of Northampton (the relevant authority, since Chesterton’s home town, Beaconsfield, is in his diocese), has given Martin Thompson, of the Chesterton Society (with whom he has had a prolonged conversation on the matter), permission to say that he “is sympathetic to our wishes and is seeking a suitable cleric to begin an investigation into the potential for opening a cause for [G K] Chesterton”. So he has not yet opened an official Cause: but he has begun the necessary preliminaries without which no Cause could be opened. This isn’t yet the end of the long years of prayer for a Cause to be officially estabished: but to adapt and slightly reverse Churchill’s famous phrase, it is the beginning of the end, and not simply the end of the beginning (the beginning was ended years ago).

After that Chestertonian turn of phrase, Oddie quotes J.J. Scarisbrick, the Catholic historian and pro-life leader:

After that Chestertonian turn of phrase, Oddie quotes J.J. Scarisbrick, the Catholic historian and pro-life leader:“We all know,” he replied, “that he was an enormously good man as well as an enormous one. My point is that he was more than that. There was a special integrity and blamelessness about him, a special devotion to the good and to justice … Above all, there was that breathtaking, intuitive (almost angelic) possession of the Truth and awareness of the supernatural which only a truly holy person can enjoy. This was the gift of heroic intelligence and understanding – and of heroic prophecy. He was a giant, spiritually as well as physically. Has there ever been anyone quite like him in Catholic history?”

And then he cites one of the qualities I've read about often--how Chesterton could disagree with someone's ideas without attacking the person (something we need so much today):

Chesterton, like many great saints (Newman springs irresistibly to mind) was a controversialist in his bones. But no matter how combatively he argued, as Belloc wrote after his death, “he seemed always to be in a mood not only of comprehension for his opponent but of admiration for some quality in him… it was this in him which made him, with other qualities, so universally beloved.” This combination of combativeness with charity was a quality that Chesterton shared with other holy men; it is, indeed, one of the reasons he understood them so well, a clear example of what is termed “connaturality”, the faculty by which one holy man has a special insight into the mind and heart of another; St Thomas Aquinas’s huge productivity, he wrote, could not have been achieved “if he had not been thinking even when he was not writing; but above all thinking combatively. This, in his case, certainly did not mean bitterly or spitefully or uncharitably; but it did mean combatively. As a matter of fact, it is generally the man who is not ready to argue, who is ready to sneer. That is why, in recent literature, there has been so little argument and so much sneering.”

Read the rest here. I have just been reading about the historian J.J. Scarisbrick and his pro-life efforts in Edward Short's new book Culture and Abortion . I had not realized the great biographer of Henry VIII and one of the early English Reformation revisionist historians was the founder of a comprehensive pro-life organization! Mr. Short sent me a copy of Culture and Abortion, his book of essays from Gracewing Publishers:

In Christifideles Laici (1988), Pope John Paul II exhorts his readers to recognize that "The inviolability of the person, which is a reflection of the absolute inviolability of God, finds its primary and fundamental expression in the inviolability of human life." For this great champion of life, "the common outcry, which is justly made on behalf of human rights ... the right to health, to home, to work, to family, to culture-is false and illusory if the right to life, the most basic and fundamental right and the condition for all other personal rights, is not defended with maximum determination." This is the conviction that prompted Edward Short to write Culture and Abortion, a study which looks at how our own culture betrays the inviolability of life by invoking what feminists call 'reproductive rights' to justify killing children in the womb. Examining the scourge of abortion from a cultural perspective, Edward Short draws on history, literature and the encyclicals of popes to show how defending the right to life can help us to reaffirm an understanding of culture that is based not on human pride or human power but on what Pope Paul II calls the "civilization of life and love." Wide-ranging and incisive, Culture and Abortion takes a fresh and provocative look at the often unacknowledged evil that continues to define our culture of death. Mr. Short has asked me for my honest opinion about his new book and I will offer it gladly soon!

In Christifideles Laici (1988), Pope John Paul II exhorts his readers to recognize that "The inviolability of the person, which is a reflection of the absolute inviolability of God, finds its primary and fundamental expression in the inviolability of human life." For this great champion of life, "the common outcry, which is justly made on behalf of human rights ... the right to health, to home, to work, to family, to culture-is false and illusory if the right to life, the most basic and fundamental right and the condition for all other personal rights, is not defended with maximum determination." This is the conviction that prompted Edward Short to write Culture and Abortion, a study which looks at how our own culture betrays the inviolability of life by invoking what feminists call 'reproductive rights' to justify killing children in the womb. Examining the scourge of abortion from a cultural perspective, Edward Short draws on history, literature and the encyclicals of popes to show how defending the right to life can help us to reaffirm an understanding of culture that is based not on human pride or human power but on what Pope Paul II calls the "civilization of life and love." Wide-ranging and incisive, Culture and Abortion takes a fresh and provocative look at the often unacknowledged evil that continues to define our culture of death. Mr. Short has asked me for my honest opinion about his new book and I will offer it gladly soon!

Published on August 09, 2013 22:30