Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 258

October 6, 2013

Lepanto and the Feast of the Holy Rosary

White founts falling in the courts of the sun, And the Soldan of Byzantium is smiling as they run;

There is laughter like the fountains in that face of all men feared,

It stirs the forest darkness, the darkness of his beard,

It curls the blood-red crescent, the crescent of his lips,

For the inmost sea of all the earth is shaken with his ships.

They have dared the white republics up the capes of Italy,

They have dashed the Adriatic round the Lion of the Sea,

And the Pope has cast his arms abroad for agony and loss,

And called the kings of Christendom for swords about the Cross,

The cold queen of England is looking in the glass;

The shadow of the Valois is yawning at the Mass;

From evening isles fantastical rings faint the Spanish gun,

And the Lord upon the Golden Horn is laughing in the sun.

--G.K. Chesterton's "Lepanto"

Today is the Feast of Our Lady of the Rosary, which was previously called "Our Lady of Victory" in thanksgiving for the victory of the combined naval forces of The Holy League against the Ottoman Turks in one of the great naval battles of the era.

Christopher Check has told this great story on a CD set from Ignatius Press, which includes a reading of G.K. Chesterton's poem, "Lepanto":

Christopher Check has told this great story on a CD set from Ignatius Press, which includes a reading of G.K. Chesterton's poem, "Lepanto":

On October 7, 1571, the most important sea battle in history was fought near the mouth of what is today called the Gulf of Patras, then the Gulf of Lepanto. On one side were the war galleys of the Holy League and on the other, those of the Ottoman Turks, rowed by tens of thousands of Christian galley slaves. Although the battle decided the future of Europe, few Europeans, and even fewer European Americans, know the story, much less how close Western Europe came to suffering an Islamic conquest.

On October 7, 1911, English poet and theologian G.K. Chesterton honored the battle with what is perhaps the greatest ballad of the 20th century. He wrote this extraordinary poem while the postman impatiently waited for the copy. It was instantly popular and remained so for years. The ballad by the great GKC is no less inspiring today and is more timely than ever, as the West faces the growing threat of Islam. Our Wichita branch of the American Chesterton Society is reading Chesterton's other great narrative poem, The Ballad of the White Horse, and an essential feature of our first meeting, which I'm sure we'll continue, was our reading the poem aloud. In addition to praying the Rosary on this feast, I think reading "Lepanto" aloud would be appropriate!

There is laughter like the fountains in that face of all men feared,

It stirs the forest darkness, the darkness of his beard,

It curls the blood-red crescent, the crescent of his lips,

For the inmost sea of all the earth is shaken with his ships.

They have dared the white republics up the capes of Italy,

They have dashed the Adriatic round the Lion of the Sea,

And the Pope has cast his arms abroad for agony and loss,

And called the kings of Christendom for swords about the Cross,

The cold queen of England is looking in the glass;

The shadow of the Valois is yawning at the Mass;

From evening isles fantastical rings faint the Spanish gun,

And the Lord upon the Golden Horn is laughing in the sun.

--G.K. Chesterton's "Lepanto"

Today is the Feast of Our Lady of the Rosary, which was previously called "Our Lady of Victory" in thanksgiving for the victory of the combined naval forces of The Holy League against the Ottoman Turks in one of the great naval battles of the era.

Christopher Check has told this great story on a CD set from Ignatius Press, which includes a reading of G.K. Chesterton's poem, "Lepanto":

Christopher Check has told this great story on a CD set from Ignatius Press, which includes a reading of G.K. Chesterton's poem, "Lepanto":On October 7, 1571, the most important sea battle in history was fought near the mouth of what is today called the Gulf of Patras, then the Gulf of Lepanto. On one side were the war galleys of the Holy League and on the other, those of the Ottoman Turks, rowed by tens of thousands of Christian galley slaves. Although the battle decided the future of Europe, few Europeans, and even fewer European Americans, know the story, much less how close Western Europe came to suffering an Islamic conquest.

On October 7, 1911, English poet and theologian G.K. Chesterton honored the battle with what is perhaps the greatest ballad of the 20th century. He wrote this extraordinary poem while the postman impatiently waited for the copy. It was instantly popular and remained so for years. The ballad by the great GKC is no less inspiring today and is more timely than ever, as the West faces the growing threat of Islam. Our Wichita branch of the American Chesterton Society is reading Chesterton's other great narrative poem, The Ballad of the White Horse, and an essential feature of our first meeting, which I'm sure we'll continue, was our reading the poem aloud. In addition to praying the Rosary on this feast, I think reading "Lepanto" aloud would be appropriate!

Published on October 06, 2013 22:30

October 4, 2013

"Art Under Attack" at Tate Britain: Under Attack

Art Under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm opened this week at the Tate Britain, and reviews are not totally positive. Not having seen the exhibition of course, I can still see what the reviewers are concerned about: the exhibition equates the destruction of Catholic art and heritage with deconstructionist art:

From The Guardian :

Art Under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm wants to make us think, but I found myself asking the wrong questions and drawing the wrong conclusions. The exhibition fumbles with ideas about "iconoclasm", or the deliberate destruction of art: can art vandalism be art? Is there a perverse humour or truth or beauty in a suffragette slashing Velázquez's Venus or the IRA blowing up Nelson's Pillar in Dublin?

But seeing the Chapmans' glib attacks on old art in the same show as that unforgettably moving Dead Christ, which resurfaced under the Mercers' Chapel in London in 1954, invites grim thoughts about what art is now. The Chapmans' disfiguring of portraits could only happen in a cynical moneyed art world that has no soul. They have the cash to buy oil paintings in order to trash them. Their clients find that kind of thing amusing.

I go back to the Dead Christ: a passionate work of art made to help ordinary people contemplate the biggest realities of life and death. The contrast damns the Chapmans to hell.

Tender depictions of the Virgin Mary and harrowing visions of the sufferings of Christ abound in the first few galleries of this show, in stone and wood and stained glass. All have been damaged, many almost beyond recognition . There are illuminated manuscripts with pages torn out. A painting of the inside of Canterbury Cathedral in 1657 looks innocuous until you see little Puritans patiently, precisely smashing out its stained glass windows.

These rooms offer a truly eye-opening revelation of how much great art was lost when the Protestant Word erased the Catholic image – sometimes literally, as when a painting of the Man of Sorrows had a Biblical text written over it .

But none of this has anything to do with the studiously ambivalent, pretentious way the rest of the show explores modern attacks on art. The casting down of Catholic art in the Reformation did not make that art more "interesting": it is loss, pure loss. Countless things have gone forever. Others survive as battered husks. Their destruction is tragic, to be mourned.

Metro publishes a similar review about how the exhibition confuses the viewer. The New York Times review is more positive but still a little ambivalent. The Guardian, which is the "media partner" of the exhibition, provides this slideshow of images. One of those images was featured on the cover of Eamon Duffy's great The Stripping of the Altars paperback edition.

Published on October 04, 2013 22:30

October 3, 2013

More on the Christian Heritage Centre

Lord Alton, Lord Windsor and Jan Graffius, the curator of the Christian Heritage Centre collection at Stonyhurst were on EWTN Live last night and talked about their visit to Washington, DC, displaying some the relics and artefacts they hope to display soon in England. The World Over news show was really all about religious freedom and conscience protections last night, as Raymond Arroyo also interviewed the Little Sisters of the Poor, who have filed a class action law suit against the HHS Mandates.

The Christian Heritage Centre segment was highlighted by close ups of a small crucifix owned by St. Thomas More and also a book from the library at St. Omers, where Stonyhurst College began, with doodles by John Carroll and Charles Carroll. John Carroll was of course the first Catholic bishop in the United States--in Baltimore Maryland--and Charles Carroll of Carrollton was the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence.

The Christian Heritage Centre does have a website and they are accepting donations to build the exhibition space needed to have these objects from English Catholic history from the Middle Ages to the present day.

The Catholic Herald writes about the visit of the three to Washington here:

Lord Nicholas Windsor is this week leading a group from Stonyhurst College, in Lancashire, on a trip to the USA to promote the Stonyhurst Christian Heritage Centre Project.

He is accompanied by Lord Alton of Liverpool, a life peer of the House of Lords, and Stonyhurst’s curator, Jan Graffius, who has with her a number of sacred artefacts from the Stonyhurst collection, including St Thomas More’s crucifix.

Lord Nicholas Windsor and Lord Alton are visiting Washington DC, Baltimore and Boston to promote their joint project and to considerably widen access to the extensive historic collection.

Earlier in the week the group attended morning Mass celebrated by the Archbishop Emeritus, Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, at St Matthew’s Cathedral in Washington DC yesterday. Cardinal McCarrick expressed his support for the Christian Heritage Centre project and said that by properly appreciating and understanding our past “we will be equipped to face the considerable challenges which confront us today and which will continue to face us in the future”.

But while we are remembering the Jesuits who collected these relics of the English martyrs and other artefacts, including relics of their own martyrs like St. Edmund Campion, since today is the feast of St. Francis of Assisi, let us not forget the Franciscan martyrs of the English Reformation. From Blessed John Forest to St. John Wall, they suffered and died for the Catholic faith England.

The Christian Heritage Centre segment was highlighted by close ups of a small crucifix owned by St. Thomas More and also a book from the library at St. Omers, where Stonyhurst College began, with doodles by John Carroll and Charles Carroll. John Carroll was of course the first Catholic bishop in the United States--in Baltimore Maryland--and Charles Carroll of Carrollton was the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence.

The Christian Heritage Centre does have a website and they are accepting donations to build the exhibition space needed to have these objects from English Catholic history from the Middle Ages to the present day.

The Catholic Herald writes about the visit of the three to Washington here:

Lord Nicholas Windsor is this week leading a group from Stonyhurst College, in Lancashire, on a trip to the USA to promote the Stonyhurst Christian Heritage Centre Project.

He is accompanied by Lord Alton of Liverpool, a life peer of the House of Lords, and Stonyhurst’s curator, Jan Graffius, who has with her a number of sacred artefacts from the Stonyhurst collection, including St Thomas More’s crucifix.

Lord Nicholas Windsor and Lord Alton are visiting Washington DC, Baltimore and Boston to promote their joint project and to considerably widen access to the extensive historic collection.

Earlier in the week the group attended morning Mass celebrated by the Archbishop Emeritus, Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, at St Matthew’s Cathedral in Washington DC yesterday. Cardinal McCarrick expressed his support for the Christian Heritage Centre project and said that by properly appreciating and understanding our past “we will be equipped to face the considerable challenges which confront us today and which will continue to face us in the future”.

But while we are remembering the Jesuits who collected these relics of the English martyrs and other artefacts, including relics of their own martyrs like St. Edmund Campion, since today is the feast of St. Francis of Assisi, let us not forget the Franciscan martyrs of the English Reformation. From Blessed John Forest to St. John Wall, they suffered and died for the Catholic faith England.

Published on October 03, 2013 22:30

October 2, 2013

Nicholas Windsor, Lord Alton, and Stonyhurst

From

Crisis

magazine comes this great story about the Catholic convert who lost his place in the royal succession of England (Lord Nicholas Windsor) and a plan for a "Museum of Christian Heritage to be located at the Jesuit estate Stonyhurst, the home of Stonyhurst College in Lancashire, England."

The Jesuits at Stonyhurst have collected some marvelous artefacts, according to author Austin Ruse:

The story of this project begins in 1593 when English Catholics established a boy’s school at a place called St. Omers not far from Calais then subject to the Spanish crown. Catholic education was not legal at the time in England and so English boys were sent there for education and protection. Besides protecting English boys, the school became a protector of precious Catholic items like vestments, manuscripts, and relics that were endangered on English soil. Thus began what is now called the “oldest surviving museum collection in the English-speaking world.”

The first acquisition in the collection came in 1609 when they took possession of Henry VII’s cope and chasuble. The Jesuits have religiously added to this collection as they have traveled the world from that time. Some of the other remarkable items include a thorn from the Crown of Thorns, the rope that bound St. Edmund Campion at the time of his execution, and personal items belonging to St. Thomas More, Elizabeth of York, Mary Tudor, Mary Queen of Scots, James II and the Stuart Family including items belong to Bonnie Prince Charlie.

The Jesuits left France and set up shop at Stonyhurst where the first museum was begun in 1796. The Arundell Library was opened there in 1855 and housed such amazing artifacts as the Book of Hours that is said to have been handed by Mary, Queen of Scotts, to her chaplain on the scaffold just before her execution.

The foundation of this Christian Heritage Centre was inspired by Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI's visit to Scotland and England in 2010. Lord David Alton's website has more about the proposed display of these artefacts (from September 2011):

One year ago, at Westminster, Pope Benedict told English Catholics not to lose their identity; not to forget their Christian roots; to remember who they are; to pass on their beliefs to their children and to share their love of their Faith with their countrymen.Some flavour of that identity has memorably been revealed in the remarkable “Treasures From Heaven” (sic)* exhibition recently staged at the British Museum and sponsored by two significant Catholics, John Studzinski CBE and Michael Hintze. Both men have been honoured with Papal Knighthoods by the Holy See for their services to arts and culture.

*Treasures of Heaven is the correct title.

The queues which have formed at the British Museum underline the public appetite for sacred culture. I saw the same phenomenon during 2008, when Liverpool was European Capital of Culture and, at St.Francis Xavier’s church, and an exhibition was staged entitled “Held in Trust”. Around 30,000 people poured in to the magnificent setting of SFX to see some of the wonderful artefacts loaned by Stonyhurst College and by the Society of Jesus. Arising out of the “Held In Trust” exhibition, Stonyhurst College published a beautiful book, by the same name, detailing some of the Collections which they hold and which they want to house in a permanent Christian Heritage Centre.

As a lasting legacy of Pope Benedict’s historic State Visit, the College Governors and the Society of Jesus have made available a Grade Two listed site, close to the College, the Corn Mill Buildings, which would be developed into an exhibition and interpretive centre. John Cowdall, the Chairman of Governors, Andrew Johnson, Stonyhurst headmaster, and the outgoing Provincial, Fr.Michael Holman SJ are all to be warmly applauded for this initiative.

Open to visitors The Christian Heritage Centre will have a mission to tell the Catholic story to future generations. Much more than a museum, it will be an interactive and inspirational educational centre; a study and retreat centre; a major visitors’ attraction; and a place where the rising generation will be inspired by the sacrifices of the past. The Christian Heritage Centre will be administered by a free standing charitable Trust. Knowledge of those who went before – and the price which they paid for the religious liberties and freedoms which we enjoy today – will help and guide our young people as they face today’s challenges and aggressive militant secularism.

Lord Alton and Lord Nicholas Windsor visited the Catholic Information Center in Washington, DC last night for a reception--unfortunately, I cannot find a website established for the Christian Heritage Centre at Stonyhurst.

The Jesuits at Stonyhurst have collected some marvelous artefacts, according to author Austin Ruse:

The story of this project begins in 1593 when English Catholics established a boy’s school at a place called St. Omers not far from Calais then subject to the Spanish crown. Catholic education was not legal at the time in England and so English boys were sent there for education and protection. Besides protecting English boys, the school became a protector of precious Catholic items like vestments, manuscripts, and relics that were endangered on English soil. Thus began what is now called the “oldest surviving museum collection in the English-speaking world.”

The first acquisition in the collection came in 1609 when they took possession of Henry VII’s cope and chasuble. The Jesuits have religiously added to this collection as they have traveled the world from that time. Some of the other remarkable items include a thorn from the Crown of Thorns, the rope that bound St. Edmund Campion at the time of his execution, and personal items belonging to St. Thomas More, Elizabeth of York, Mary Tudor, Mary Queen of Scots, James II and the Stuart Family including items belong to Bonnie Prince Charlie.

The Jesuits left France and set up shop at Stonyhurst where the first museum was begun in 1796. The Arundell Library was opened there in 1855 and housed such amazing artifacts as the Book of Hours that is said to have been handed by Mary, Queen of Scotts, to her chaplain on the scaffold just before her execution.

The foundation of this Christian Heritage Centre was inspired by Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI's visit to Scotland and England in 2010. Lord David Alton's website has more about the proposed display of these artefacts (from September 2011):

One year ago, at Westminster, Pope Benedict told English Catholics not to lose their identity; not to forget their Christian roots; to remember who they are; to pass on their beliefs to their children and to share their love of their Faith with their countrymen.Some flavour of that identity has memorably been revealed in the remarkable “Treasures From Heaven” (sic)* exhibition recently staged at the British Museum and sponsored by two significant Catholics, John Studzinski CBE and Michael Hintze. Both men have been honoured with Papal Knighthoods by the Holy See for their services to arts and culture.

*Treasures of Heaven is the correct title.

The queues which have formed at the British Museum underline the public appetite for sacred culture. I saw the same phenomenon during 2008, when Liverpool was European Capital of Culture and, at St.Francis Xavier’s church, and an exhibition was staged entitled “Held in Trust”. Around 30,000 people poured in to the magnificent setting of SFX to see some of the wonderful artefacts loaned by Stonyhurst College and by the Society of Jesus. Arising out of the “Held In Trust” exhibition, Stonyhurst College published a beautiful book, by the same name, detailing some of the Collections which they hold and which they want to house in a permanent Christian Heritage Centre.

As a lasting legacy of Pope Benedict’s historic State Visit, the College Governors and the Society of Jesus have made available a Grade Two listed site, close to the College, the Corn Mill Buildings, which would be developed into an exhibition and interpretive centre. John Cowdall, the Chairman of Governors, Andrew Johnson, Stonyhurst headmaster, and the outgoing Provincial, Fr.Michael Holman SJ are all to be warmly applauded for this initiative.

Open to visitors The Christian Heritage Centre will have a mission to tell the Catholic story to future generations. Much more than a museum, it will be an interactive and inspirational educational centre; a study and retreat centre; a major visitors’ attraction; and a place where the rising generation will be inspired by the sacrifices of the past. The Christian Heritage Centre will be administered by a free standing charitable Trust. Knowledge of those who went before – and the price which they paid for the religious liberties and freedoms which we enjoy today – will help and guide our young people as they face today’s challenges and aggressive militant secularism.

Lord Alton and Lord Nicholas Windsor visited the Catholic Information Center in Washington, DC last night for a reception--unfortunately, I cannot find a website established for the Christian Heritage Centre at Stonyhurst.

Published on October 02, 2013 22:30

October 1, 2013

Martyrdom and Father Kapaun's Cause

A Vatican lawyer involved with the cause of Servant of God Emil Kapaun, who suffered and died in a Korean prison camp, visited Wichita, Kansas last week and commented on the progress of the cause. According to the

Wichita Eagle

, which ran a multi-part story about Father Kapaun and his heroism, Andrea Ambrosi offered warnings of delay and uncertainty:

A Vatican lawyer involved with the cause of Servant of God Emil Kapaun, who suffered and died in a Korean prison camp, visited Wichita, Kansas last week and commented on the progress of the cause. According to the

Wichita Eagle

, which ran a multi-part story about Father Kapaun and his heroism, Andrea Ambrosi offered warnings of delay and uncertainty: Speaking with translation by Ohio-born aide Madeleine Kuns, he said a key decision the Vatican must make is whether Kapaun was martyred for standing up for his faith.

There is no doubt Kapaun was a hero, he said. But was he a martyr?

Ambrosi said he has analyzed more than 8,000 documents and testimonies, including from Korean War combat soldiers who saw Kapaun’s heroism. Ambrosi said that for the first time after years of study of Kapaun’s life, he now plans to propose Kapaun as a martyr in his report to the Vatican, a report he thinks will be completed in the next six months.

And that bit about martyrdom is important to the Vatican’s decision. But because the Vatican’s bar for martyrdom is so high, even his recommendation may not be enough to persuade church officials, Ambrosi said. If the church decides Kapaun was martyred – killed because he was a religious person defending his faith – it could significantly speed up the process to canonize Kapaun to full sainthood. But if the cardinals in the Congregation for the Causes of Saints decide Kapaun wasn’t a martyr, it could mean many years before Kapaun’s sainthood cause would advance.

Martyrdom was not always easy to prove in the case of the English Martyrs, either, as this site explains:

The cases of the English martyrs killed during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and Elizabeth (1534-1603) provide certain challenges from a documentary standpoint, making it very difficult to establish with certainty the fact of martyrdom.

First, the legal proscription of Catholicism in England from 1534 to emancipation in 1829 means that it was not always possible to carry out investigations into the causes of these martyrs. In the times when harboring a priest was a capital crime and even attending Mass punishable by a fine of 1600 shillings, carrying out these investigations under proper canonical form was simply not possible. Free and open inquiry into the cases of the English martyrs and access to the documentation regarding their deaths was not available until the restoration of the English hierarchy in 1850, by which time over three centuries had elapsed since the time of most of the martyrs.

Second, because the persecution of the Catholic Church in England was carried out under a fundamentally political program, those convicted and punished under the penal laws are often listed as cases of 'treason' or 'conspiracy' in the official records, which are often the only records. Though we know that the threat of Catholic conspiracies was extremely overblown and many "plots" were even fabricated (the Titus Oates Plot, for example), there were nevertheless certain Catholics who were involved in clandestine political activities. The result is that it is very difficult to tell the exact details when both organizing a political conspiracy and simply saying Mass are both classified as "treason" in the official record. Finally, in many cases, there was no official record kept whatsoever, making reconstructing events extremely difficult. . . .

This was particularly true in the case of those who opposed the dissolution of their monasteries:

A classic case of this last problem are the three Benedictine abbots of Glastonbury, Reading and Colchester, all put to death quietly for treason in 1539 and all of which lack any official documentation.

This, then, is a brief summary of some of the difficulties the restored Catholic hierarchy of England faced when it first began to push for the causes of the English martyrs. Despite the English Church's admirable desire to raise many of its heroic sons to the altars, the Sacred Congregation for Rites was characteristically slow-moving and skeptical of proceeding to beatification when so much documentary evidence was lacking. In fact, when the English hierarchy sent off the available documentation on 353 martyrs Rome in 1880, 76 applications were rejected for lack of sufficient historical evidence. These rejected martyrs are known as dilati, those whose cases are referred back to the Ordinary for insufficient evidence.

And some of those causes of the dilati are still waiting for more evidence.

Published on October 01, 2013 23:00

Historical Apologetics @ Homiletic & Pastoral Review

Homiletic & Pastoral Review , which recently went to a web-only format, published an article I submitted on "Knowing Enough History to Defend It: Catholic History and Apologetics":

While many seem to disregard the study of history as a wasteful pastime, events in Catholic Church history are often used to attack us. Based on ignorance, prejudice, or confusion, people know, or think they know, something about our Church’s past that is scandalous, cruel, or just bad. They use this misinformation or some distorted view of an event to attack the Church’s credibility on current moral issues, as if to say an institution that can perpetrate such misdeeds in the past can’t tell me what to do with my body (artificial birth control, abortion, fornication, etc.); it can’t tell me what’s right and what’s wrong.

Catholics should be prepared with at least a brief reply to commonly cited events and issues in the Church’s two millennia past. In the words of Blessed John Henry Newman, we need to be Catholics “who know so much of history that (we) can defend it.” We might not be able to change someone’s mind when she asks us about why the Church was so mean to Galileo, but at least we can demonstrate that we know our history. If she’s not willing to listen to a dissertation-length explanation, a few points might help her understand better. The fact that we know may impress her, open the door to more friendly conversation, and grant an opportunity to witness the reason for our joy in being Catholic. This article offers some guidelines and hints for answering these historical questions.

Please read the rest there. I meant for it to be a survey of helpful hints on answering common questions about Church History, inspired by Blessed John Henry Newman. If you want to read the original--that is, Blessed John Henry Newman--on Church History, you should peruse the five letters he wrote to John Rickards Mozley, his nephew. When Newman speaks about the "light" side of the Catholic Church, he is much more eloquent than I am:

But leaving the highest and truest outcome of the Catholic Church and descending to history, certainly I would maintain firmly, with most writers on the Evidences, that, as the Church has a dark side, so (as you do not seem to admit) it has a light side also, and that its good has been more potent and permanent and evidently intrinsic to it than its evil. Here, of course, we have to rely on the narrative of historians, if we have not made a study of original documents ourselves. It would be a long business (assuming their correctness), but an easy business too, to show how Christianity has raised the moral standard, tone, and customs of human society; and it must be recollected that for 1500 years Christianity and the Catholic Church are in history identical. The care and elevation of the lower classes, the championship of the weak against the powerful, the abolition of slavery, hospitals, the redemption of captives, education of children, agriculture, literature, the cultivation of the virtues of piety, devotion, justice, charity, chastity, family affection, are all historical monuments of the influence and teaching of the Church. Turn to the non-Catholic historians, to Gibbon, Voigt, Hurter, Guizot, Ranke, Waddington, Bowden, Milman, and you will find that they agree in their praises, as well as in their accusations, of the Catholic Church. Guizot says that Christianity would not have weathered the barbarism of the Middle Age but for the Church. Milman says almost or altogether the same. Neander sings the praises of the monks. Hurter was converted by his historical researches. Ranke shows how the Popes fought against the savageness of the Spanish Inquisition. Bowden brings out visibly how the cause of Hildebrand was the cause of religion and morals. If in the long line there be bad as well as good Popes, do not forget that long succession, continuous and thick, of holy and heroic men, all subjects of the Popes, and most of them his direct instruments in the most noble and serviceable and most various works, and some of them Popes themselves, such as Patrick, Leo, Gregory, Augustine, Boniface, Columban, Alfred, Wulstan, Queen Margaret of Scotland, Louis IX., Vincent Ferrer, Las Casas, Turibius, Xavier, Vincent of Paul—all of whom, as multitudes besides, in their day were the life of religion.

And when he answers his nephew's questions about the St. Bartholomew Day's Massacre and the "bad" popes, Newman is direct and "unapologetic" with his apologetics:

I think such insane acts as St. Bartholomew's Massacre were prompted by mortal fear. The French Court considered (rightly or wrongly) that if they did not murder the Huguenots, the Huguenots would murder them. Thus I explain Pope Gregory's hasty approbation of so great a crime, without waiting to hear both sides. After a period of luxury and sloth, the sudden outburst of the Reformation frightened the Court of Rome out of its wits, and there were those who thought the one thing needful was to put it down anyhow, as the destruction, at least eventually, of all religion, morality, and society. Perhaps they were right in this fear; and thus they got mixed up with mere politicians, unscrupulous men, and became in the eyes of posterity answerable for deeds which were not properly theirs. I was reading the other day a defence of Pius V. against Lord Acton, the point of which was that in no sense was it the Pope who sanctioned the plot for assassinating Elizabeth, but, the Duke of Alva. Yet who can deny, true as this may be, still that to readers of history the Pope and the Duke are in one boat? Then, again, their agents, or the sovereigns who sought their sanction for certain courses or measures, went far beyond the intention of the Popes, who nevertheless, from their political entanglements, could not resume the powers that they had once given over to them. A large society, such as the Church, is necessarily a political power, and to touch politics is to touch pitch. A private Catholic is not answerable for the Pope's political errors, any more than the shareholder in a railway in 1875 is answerable for the railway's accidents in 1860, nay, or in 1875.

You say that at least the Popes ought publicly to confess, when it is proved they have gone wrong. Does Queen Victoria confess the sins of George IV.? Do principals feel it generous to abandon their subordinates, or loyal children acquiesce in attacks on their parents? As to controversialists, they are pleaders at a bar, and are afraid to make admissions lest these should be turned against them. To speak out is in the long run the wisest, the most expedient, the most noble policy; seldom the possible, or the natural. Why are private memoirs kept back from publication for thirty or sixty years? No party can be kept together if there is no reticence. But in fact, except among controversialists, there is no want of candour and frankness among us; witness the fact that Protestant attacks on us generally are drawn from the admissions of Catholics. Baronius, writing under the Pope's eye, speaks in the strongest terms of the evil state of the Popedom in the dark age; Rinaldus, his continuator, speaks against Alexander VI.; St. Bernard, St. Thomas, and many others speak against the conduct of the Roman See in their own times. So do Pope Adrian VI., Paul IV., &c. So do holy women in their writings, such as St. Bridget.

Published on October 01, 2013 22:30

September 30, 2013

October 1, 1588 at Chichester (and at Canterbury)

In response to the attempted invasion of England by Spain, from late August through October in 1588, the Elizabeth government arranged several executions of Catholic priests and/or laity in demonstration of the fate of traitors. In Chichester and in Canterbury on October 1, 1588, the government planned two more group executions of priests.

In Chichester, something unusual happened—one of the priests on the scaffold recanted and agreed to take the Oath of Supremacy. Four priests had been condemned to death on September 30, but one of the four had already taken the Oath of Supremacy after condemnation to avoid being hung, drawn, and quartered.

Father Edward James and Father Ralph Crockett had been arrested on April 19, 1586 and held in prison in London for more than two years without trial (from April 27, 1586). After the failure of the Spanish Armada, these imprisoned Catholic priests were prime targets of the English government for vengeance and punishment. Fr. James and Fr. Crockett were tried in Chichester along with Father John Oven and Father Francis Edwardes, found guilty and sentenced to death, but Fr. Oven took the Oath of Supremacy and was reprieved.

Then on October 1st, at Broyle Heath, Fr. Edwardes took the Oath of Supremacy and was reprieved--Fr. James and Fr. Crockett refused to recant and the butchery of their execution was carried out, after they first absolved each other on the scaffold. So often when we tell the story of the Catholic recusants and the Catholic priests of that recusant era, we emphasize the heroic faithfulness of those who suffered and died. This story reminds us that some who faced the crisis of life and death chose to recant their Catholic faith and avoid martyrdom.

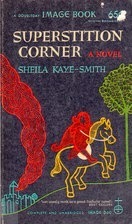

In her novel

Superstition Corner

, the Catholic convert from Anglicanism Sheila Kaye-Smith depicts the effect of Father Edwardes recanting and accepting the Oath of Supremacy on a recusant Catholic who knew him. Catherine Alard has travelled to Chichester, hoping to meet her brother who is now a Catholic priest, and hears about the impending executions:

In her novel

Superstition Corner

, the Catholic convert from Anglicanism Sheila Kaye-Smith depicts the effect of Father Edwardes recanting and accepting the Oath of Supremacy on a recusant Catholic who knew him. Catherine Alard has travelled to Chichester, hoping to meet her brother who is now a Catholic priest, and hears about the impending executions:

Among much that was painful for her to hear, Catherine learned that the names of the other two priests were Ralph Crockett and Edward James, so she now knew for certain that Father Oven had refused his martyr's crown. The number of her honest men was dwindling . . . miserere mei. . . . She felt strangely moved and exalted, almost light-headed, as at last she jostled her way under the gate and came out on the high-road leading to the Broyle.

About a mile farther on the gallows rose up before her, and she felt a curious fear and constriction of her heart. This would not be the first hanging she had seen, but it would indeed, as the landlord had said, be different from the others. To-day she would see men die, but not for their own sins. No doubt their sufferings would be a passion offered for the sins of the unfaithful—for the unfaithful that they did not know as well as for the unfaithful that they knew. These three friends would die expiating her father's conformity, her mother's adultery, her friend's apostasy: they would wipe her world clean as they left it. . . . Yet before they died she would have to witness dreadful things, and for a moment her heart failed her. Though she had never been squeamish, she was glad to be on the outskirts of the crowd that swarmed round the scaffold.

Catherine witnesses the executions of Father Crockett, appalled by the animosity of the crowd toward the priest and horrified by his suffering:

Then silence fell: the executioner stood on the ladder watching the victim's struggles, and when they seemed to decrease gave the order for him to be cut down. He was caught as he fell, and his clothes torn off him, so that castration and dismemberment could follow while he was still alive. Catherine had never before seen an execution for high treason, and an ordinary hanging had always stopped short of this. She began to feel a little sick, and would have closed her eyes had she been able, but a kind of paralysis had taken her, and she could not move; she could only sit there staring and holding up her beads.

After seeing Father James suffer in the same horrible way, she notices that Father Edwardes’ execution is not proceeding apace, but that he has begun to cry out for mercy:

"Oh, Lord!" cried Catherine. "Oh, dear, dear Lord!" A great yell broke from the crowd, and she expected to see the wretched man carried up the ladder and flung off in a bundle. But the next moment she saw that something else was happening. Three men in black who had been standing with the magistrates on the scaffold now came forward, and she guessed that they were the Protestant ministers. They gathered round Francis Edwards (sic), who was vomiting. She knew that they were offering him his life at a price which in his terror and exhaustion he might pay. De profundus clamavi ad te, Domine: Domine, exaudi vocem meum. Oh, Lord, help him; oh, Lord, spare him. . . . Oh, Lord, let him fall down dead rather than deny his faith. . . . Oh, Lord, spare him. . . . Domine, Domine, exaudi vocem meum. The crowd was shouting and muttering—some were urging the martyr to change his faith and save his life. "'At, that's right 'at, that's right!" "Be a Protestant and live!" But others said: "You can never trust a Jesuit." "Set him free and he poisons us all." The cries swelled to a roar, and all the time a voice was shouting in her ear miserere mei! miserere mei! She did not know it was her own. . . .

She could stay no longer; the sheriff came to the edge of the scaffold to address the crowd, but she would not wait. She had seen enough—too much; and in that distracted moment she did not know which was too much—the sufferings of the martyrs or the sparing of the apostate. Francis Edwards had been spared—he would not have to climb that ladder, to endure that agony, to suffer that outrageous death. She was glad—she was glad. No, no—she was not glad. She was sorry.

Kaye-Smith’s description of the crowd and its changing fancies serve as a good example the expectations of the witnesses of the executions to see justice handed out effectively.

For the story of the Canterbury martyrs, click here.

In Chichester, something unusual happened—one of the priests on the scaffold recanted and agreed to take the Oath of Supremacy. Four priests had been condemned to death on September 30, but one of the four had already taken the Oath of Supremacy after condemnation to avoid being hung, drawn, and quartered.

Father Edward James and Father Ralph Crockett had been arrested on April 19, 1586 and held in prison in London for more than two years without trial (from April 27, 1586). After the failure of the Spanish Armada, these imprisoned Catholic priests were prime targets of the English government for vengeance and punishment. Fr. James and Fr. Crockett were tried in Chichester along with Father John Oven and Father Francis Edwardes, found guilty and sentenced to death, but Fr. Oven took the Oath of Supremacy and was reprieved.

Then on October 1st, at Broyle Heath, Fr. Edwardes took the Oath of Supremacy and was reprieved--Fr. James and Fr. Crockett refused to recant and the butchery of their execution was carried out, after they first absolved each other on the scaffold. So often when we tell the story of the Catholic recusants and the Catholic priests of that recusant era, we emphasize the heroic faithfulness of those who suffered and died. This story reminds us that some who faced the crisis of life and death chose to recant their Catholic faith and avoid martyrdom.

In her novel

Superstition Corner

, the Catholic convert from Anglicanism Sheila Kaye-Smith depicts the effect of Father Edwardes recanting and accepting the Oath of Supremacy on a recusant Catholic who knew him. Catherine Alard has travelled to Chichester, hoping to meet her brother who is now a Catholic priest, and hears about the impending executions:

In her novel

Superstition Corner

, the Catholic convert from Anglicanism Sheila Kaye-Smith depicts the effect of Father Edwardes recanting and accepting the Oath of Supremacy on a recusant Catholic who knew him. Catherine Alard has travelled to Chichester, hoping to meet her brother who is now a Catholic priest, and hears about the impending executions:Among much that was painful for her to hear, Catherine learned that the names of the other two priests were Ralph Crockett and Edward James, so she now knew for certain that Father Oven had refused his martyr's crown. The number of her honest men was dwindling . . . miserere mei. . . . She felt strangely moved and exalted, almost light-headed, as at last she jostled her way under the gate and came out on the high-road leading to the Broyle.

About a mile farther on the gallows rose up before her, and she felt a curious fear and constriction of her heart. This would not be the first hanging she had seen, but it would indeed, as the landlord had said, be different from the others. To-day she would see men die, but not for their own sins. No doubt their sufferings would be a passion offered for the sins of the unfaithful—for the unfaithful that they did not know as well as for the unfaithful that they knew. These three friends would die expiating her father's conformity, her mother's adultery, her friend's apostasy: they would wipe her world clean as they left it. . . . Yet before they died she would have to witness dreadful things, and for a moment her heart failed her. Though she had never been squeamish, she was glad to be on the outskirts of the crowd that swarmed round the scaffold.

Catherine witnesses the executions of Father Crockett, appalled by the animosity of the crowd toward the priest and horrified by his suffering:

Then silence fell: the executioner stood on the ladder watching the victim's struggles, and when they seemed to decrease gave the order for him to be cut down. He was caught as he fell, and his clothes torn off him, so that castration and dismemberment could follow while he was still alive. Catherine had never before seen an execution for high treason, and an ordinary hanging had always stopped short of this. She began to feel a little sick, and would have closed her eyes had she been able, but a kind of paralysis had taken her, and she could not move; she could only sit there staring and holding up her beads.

After seeing Father James suffer in the same horrible way, she notices that Father Edwardes’ execution is not proceeding apace, but that he has begun to cry out for mercy:

"Oh, Lord!" cried Catherine. "Oh, dear, dear Lord!" A great yell broke from the crowd, and she expected to see the wretched man carried up the ladder and flung off in a bundle. But the next moment she saw that something else was happening. Three men in black who had been standing with the magistrates on the scaffold now came forward, and she guessed that they were the Protestant ministers. They gathered round Francis Edwards (sic), who was vomiting. She knew that they were offering him his life at a price which in his terror and exhaustion he might pay. De profundus clamavi ad te, Domine: Domine, exaudi vocem meum. Oh, Lord, help him; oh, Lord, spare him. . . . Oh, Lord, let him fall down dead rather than deny his faith. . . . Oh, Lord, spare him. . . . Domine, Domine, exaudi vocem meum. The crowd was shouting and muttering—some were urging the martyr to change his faith and save his life. "'At, that's right 'at, that's right!" "Be a Protestant and live!" But others said: "You can never trust a Jesuit." "Set him free and he poisons us all." The cries swelled to a roar, and all the time a voice was shouting in her ear miserere mei! miserere mei! She did not know it was her own. . . .

She could stay no longer; the sheriff came to the edge of the scaffold to address the crowd, but she would not wait. She had seen enough—too much; and in that distracted moment she did not know which was too much—the sufferings of the martyrs or the sparing of the apostate. Francis Edwards had been spared—he would not have to climb that ladder, to endure that agony, to suffer that outrageous death. She was glad—she was glad. No, no—she was not glad. She was sorry.

Kaye-Smith’s description of the crowd and its changing fancies serve as a good example the expectations of the witnesses of the executions to see justice handed out effectively.

For the story of the Canterbury martyrs, click here.

Published on September 30, 2013 22:30

September 29, 2013

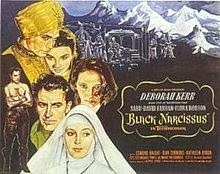

Deborah Kerr and The English Reformation

Today is the anniversary of the birth of one of my favorite actresses, Deborah Kerr, in 1921. You might think that there is no connection between that anniversary and the subject of this blog, but you would be wrong!

First, Deborah Kerr played Catherine Parr, Henry VIII's last wife, in the 1953 movie, Young Bess, based on Margaret Irwin's novel of the same title. Parr's Protestant evangelical tendencies are depicted when Henry VIII (played by Charles Laughton, again) accuses her of authorizing an English translation of the Holy Bible without his permission.

Secondly, Kerr played an Irish girl who hates the memory of Oliver Cromwell so much that she won't spend her honeymoon in an inn named the "Cromwell Arms" in the movie titled either The Adventurous or I See a Dark Stranger.

Thirdly, Deborah Kerr played the role of Sister Clodagh in the movie based on Rumer Godden's Black Narcissus. Rumer Godden is one of the authors I mention in my litany of conversions in the last chapter of Supremacy and Survival: How Catholics Endured the English Reformation. Interesting, Kathleen Byron, who plays Sister Ruth, the mad, bad nun, also appeared in Young Bess, as Anne Seymour, Edward Seymour's wife.

Finally--and this is obscure indeed--Kerr played Gulielma Maria Springett, William Penn's first wife, in Penn of Pennsylvania, a rather unsuccessful biopic of King James II's ally in the attempt to bring religious freedom to England before the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

Convinced?

Published on September 29, 2013 22:30

September 28, 2013

English Monarchs and Music on the BBC

I wonder if we shall see David Starkey's BBC series on Music and Monarchy, on PBS which includes many examples of Renaissance polyphony, royal influence on musical composers, and the integration of music in the life and ceremony of royalty in England from the Middle Ages to the modern era. If not, a book, DVD, and CD are either available now or for pre-order and release later this year. There is also a youtube video of the first episode, beginning with Henry V and Henry VIII (interrupted by commercials).

Gramaphone Magazine

liked the series:

Gramaphone Magazine

liked the series:

There's a sort of exuberant delight to Starkey's presentation – there he is pondering a performance just off centre-stage, or sometimes even standing right next to the conductor, or perhaps midway between the two ranks of choir stalls. He may as well stand in the best acoustic spot I suppose – but I guess the message is that Starkey is on a journey of discovery, and, through him, so are we. It's accessible history in the best tradition: rich in observation, a strong narrative told with conviction and colour, enthusing energetically throughout. The script takes fascinating facets of the story and elevates them with the sort of rhetoric which has made Starkey such a successful communicator of history. Thus, Henry V's French invasions were 'A Holy War to be fought with music'. Henry VIII 'was a master of the politics of splendour, and the brightest jewel and the most effective instrument was his Chapel Royal'. Episode one closes with Elizabeth I's court and the glories of her Chapel Royal: 'Outside it was the cold winter of Protestant austerity, inside it was indeed the warm summer of the Golden age of English Church music'.

But above all, we get to see some of the most important pieces of music of the past half-millennium performed in the places for which they were written, by the modern musicians who know them best, among them David Skinner, Fretwork, Richard Egarr and the Choirs of King's College Cambridge and Westminster Abbey. The lists of works featuring in the series runs onto four sides of A4.

Music, argues Starkey's series, was as integral to the image and power of monarchy as were armies and architecture. Nothing embodies the latter quite so well as Westminster Abbey itself of course, built as a shrine to a King-Saint, and later adorned at the east end with its glorious Lady Chapel in the most exquisite Perpendicular Gothic and itself a monument to Tudor prestige. Here, and throughout the Abbey's many chapels, the kings and queens now lie silent beneath austere tombs. The music, of course, lives on. Perhaps it's fitting that of all the memorials in the Abbey, it's one to a musician - Handel, sculpted by Louis-François Roubiliac - that is by far the most full of life.

The Spectator

likes the book too, and highlights the influence of the English Reformation on English music, as Starkey notes that Henry VIII nearly destroyed the liturgical music he loved so much:

The Spectator

likes the book too, and highlights the influence of the English Reformation on English music, as Starkey notes that Henry VIII nearly destroyed the liturgical music he loved so much:

The Reformation targeted not merely the liturgy gracing the chapels themselves but the very performance style of their masses and motets. As early as 1516 Erasmus, in his Commentary on Corinthians 1.14, had criticised the vogue for increasingly complex polyphony, ‘a certain elaborate and theatrical music’ for which English clerics cherished a special fondness. ‘Those who are more doltish than really learned are not content unless they can use a distorted kind of music called descant.’ Thirty years later, with the walls whitewashed, shrines desecrated and idolatrous images torn down, Archbishop Cranmer, backed by Queen Catherine Parr, took up the cry. ‘In mine opinion,’ he told Henry VIII, ‘the song that shall be made would not be full of notes, but as near as may be, for every syllable a note, so that it may be sung distinctly and devoutly.’

Starkey and Greening neatly demonstrate how much of what we treasure in Tudor church music is due to skilful religious fudging and compromise by Catholic court musicians, as also to the unfathomable quirks and ambiguities of Elizabeth I’s spiritual outlook and artistic tastes. Sovereigns in her time were noted, not always sycophantically, as accomplished performers, vocal or instrumental. Elizabeth may not have been quite such a versatile keyboard player as her flatterers claimed, but King Charles I handled a bass viol with professional skill and honoured his lutenists and singers with the ultimate royal accolade of leaning a hand on their shoulders as they played. Music & Monarchy captures the tragic irony underlying Charles’s execution outside the very same Inigo Jones Banqueting House once resonating with the lyrics and dances of those extravagant masques which, during the 1630s, had sustained the increasing illusion of his kingship.

The book and the DVD are definitely on my wish list!

Gramaphone Magazine

liked the series:

Gramaphone Magazine

liked the series:There's a sort of exuberant delight to Starkey's presentation – there he is pondering a performance just off centre-stage, or sometimes even standing right next to the conductor, or perhaps midway between the two ranks of choir stalls. He may as well stand in the best acoustic spot I suppose – but I guess the message is that Starkey is on a journey of discovery, and, through him, so are we. It's accessible history in the best tradition: rich in observation, a strong narrative told with conviction and colour, enthusing energetically throughout. The script takes fascinating facets of the story and elevates them with the sort of rhetoric which has made Starkey such a successful communicator of history. Thus, Henry V's French invasions were 'A Holy War to be fought with music'. Henry VIII 'was a master of the politics of splendour, and the brightest jewel and the most effective instrument was his Chapel Royal'. Episode one closes with Elizabeth I's court and the glories of her Chapel Royal: 'Outside it was the cold winter of Protestant austerity, inside it was indeed the warm summer of the Golden age of English Church music'.

But above all, we get to see some of the most important pieces of music of the past half-millennium performed in the places for which they were written, by the modern musicians who know them best, among them David Skinner, Fretwork, Richard Egarr and the Choirs of King's College Cambridge and Westminster Abbey. The lists of works featuring in the series runs onto four sides of A4.

Music, argues Starkey's series, was as integral to the image and power of monarchy as were armies and architecture. Nothing embodies the latter quite so well as Westminster Abbey itself of course, built as a shrine to a King-Saint, and later adorned at the east end with its glorious Lady Chapel in the most exquisite Perpendicular Gothic and itself a monument to Tudor prestige. Here, and throughout the Abbey's many chapels, the kings and queens now lie silent beneath austere tombs. The music, of course, lives on. Perhaps it's fitting that of all the memorials in the Abbey, it's one to a musician - Handel, sculpted by Louis-François Roubiliac - that is by far the most full of life.

The Spectator

likes the book too, and highlights the influence of the English Reformation on English music, as Starkey notes that Henry VIII nearly destroyed the liturgical music he loved so much:

The Spectator

likes the book too, and highlights the influence of the English Reformation on English music, as Starkey notes that Henry VIII nearly destroyed the liturgical music he loved so much:The Reformation targeted not merely the liturgy gracing the chapels themselves but the very performance style of their masses and motets. As early as 1516 Erasmus, in his Commentary on Corinthians 1.14, had criticised the vogue for increasingly complex polyphony, ‘a certain elaborate and theatrical music’ for which English clerics cherished a special fondness. ‘Those who are more doltish than really learned are not content unless they can use a distorted kind of music called descant.’ Thirty years later, with the walls whitewashed, shrines desecrated and idolatrous images torn down, Archbishop Cranmer, backed by Queen Catherine Parr, took up the cry. ‘In mine opinion,’ he told Henry VIII, ‘the song that shall be made would not be full of notes, but as near as may be, for every syllable a note, so that it may be sung distinctly and devoutly.’

Starkey and Greening neatly demonstrate how much of what we treasure in Tudor church music is due to skilful religious fudging and compromise by Catholic court musicians, as also to the unfathomable quirks and ambiguities of Elizabeth I’s spiritual outlook and artistic tastes. Sovereigns in her time were noted, not always sycophantically, as accomplished performers, vocal or instrumental. Elizabeth may not have been quite such a versatile keyboard player as her flatterers claimed, but King Charles I handled a bass viol with professional skill and honoured his lutenists and singers with the ultimate royal accolade of leaning a hand on their shoulders as they played. Music & Monarchy captures the tragic irony underlying Charles’s execution outside the very same Inigo Jones Banqueting House once resonating with the lyrics and dances of those extravagant masques which, during the 1630s, had sustained the increasing illusion of his kingship.

The book and the DVD are definitely on my wish list!

Published on September 28, 2013 22:30

September 26, 2013

Shakespeare and Catholicism, Redux

A forthcoming book, published by Penn State University Press:

A forthcoming book, published by Penn State University Press:For years scholars and others have been trying to out Shakespeare as an ardent Calvinist, a crypto-Catholic, a Puritan-baiter, a secularist, or a devotee of some hybrid faith. In Religion Around Shakespeare, Peter Kaufman sets aside such speculation in favor of considering the historic and religious context surrounding his work. Employing extensive archival research, he aims to assist literary historians who probe the religious discourses, characters, and events that seem to have found places in Shakespeare’s plays and to aid general readers or playgoers developing an interest in the plays’ and playwright’s religious contexts: Catholic, conformist, and reformist. Kaufman argues that sermons preached around Shakespeare and conflicts that left their marks on literature, law, municipal chronicles, and vestry minutes enlivened the world in which (and with which) he worked and can enrich our understanding of the playwright and his plays.

You may read a sample chapter, the Introduction, at the Penn State University Press webpage for Religion Around Shakespeare:

I am not a literary historian, and what follows is not another interpretation of several of Shakespeare’s plays. For decades I have been studying the religious cultures of late Tudor and early Jacobean England, particularly what Alison Shell now calls the “fierce internal debate” that “beset” the established church, which was having problems as well “see[ing] off challenges from outside.” What I do in this book is give everyone interested in reading, watching, interpreting, or performing the plays a good look at the religion around Shakespeare. Circumstance is my subject.

Historians have long been at work on the religion of Shakespeare, and a few have gotten around to the religion around him. Several relatively recent and much publicized efforts suggest that late Elizabethan and early Stuart theatergoers justifiably saw Shakespeare’s plays as coded endorsements of expatriate Catholic missionaries’ efforts to restore the realm’s old faith, which Shell characterizes as “challenges from [the] outside.” Those presentations of the playwright’s Catholicism claim to have cracked the code that concealed his religiously unreformed opinions from religiously reformed government censors while it cued Catholics in his first audiences to his abiding allegiance to what they remembered as traditional Christianity. What twenty-first-century playgoers may see and hear simply as Hamlet’s brooding over the skull of poor Yorick is, after some code cracking, an “encrypted tribute” to the Englishman Edmund Campion, who left the realm rather than subscribe to his queen’s religion, returned to reinforce the faith of the resident Catholics, and died a martyr. . . .

Where did Shakespeare fit? Literary historians looking to out him as a Calvinist or a Catholic or a devotee of some “hybrid faith” should find something of interest here, although what follows will fall short of a definitive answer to their questions. I am not mining for that metal. Unquestionably, the playwright borrowed from the religion around him, and what he deposited in his drama “infused” performances, as Leah Marcus says, “with a vitality born of circumstance.” The plays profit from Shakespeare’s “sublimation into high drama of what is casually there at hand.” Nonetheless, to proceed from what was “at hand” and what is now staged so often to a singular scribe’s secrets—to his religious convictions—requires a razzle-dazzle that I am inadequately equipped to attempt.

Circumstance—the religion around the playwright, not his faith or the plays’ proper interpretations—is my subject. I leave Shakespeare’s outlook to others. My challenge is to see how well we can see what he saw when he looked out.

Reading this brief introduction, it's clear that Professor Kaufman will not say that Shakespeare was a Catholic, even if a Church Papist. Since he refers to the encoded Catholicism of Shakespeare's plays in the Introduction, I wonder if he will directly engage the arguments of Clare Asquith's Shadowplay: The Hidden Beliefs and Coded Politics of William Shakespeare. For those who follow this theme of Shakespeare's religious identity, Religion Around Shakespeare seems to be an intriguing addition to the bibliography. And if you like to read about the religious background and milieu of other authors, this is the first book in a series "Religion Around":

Books in this series examine the religious forces surrounding cultural icons from all facets of world history and contemporary culture. By bringing religious background into the foreground, these studies will help give readers a more complex understanding and greater appreciation for individual subjects, their work, and their lasting influence. Forthcoming volumes will explore the religion around Emily Dickinson, Virginia Woolf, and Langston Hughes, among others.

Published on September 26, 2013 22:30