Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 254

November 16, 2013

St. Hugh of Lincoln, Carthusian and Bishop

Except that this is Sunday, today, November 17 is the feast of St Hugh of Lincoln. According to this site:

Hugh of Lincoln was the son of William, Lord of Avalon. He was born at Avalon Castle in Burgundy and was raised and educated at a convent at Villard-Benoit after his mother died when he was eight. He was professed at fifteen, ordained a deacon at nineteen, and was made prior of a monastery at Saint-Maxim. While visiting the Grande Chartreuse with his prior in 1160. It was then he decided to become a Carthusian there and was ordained. After ten years, he was named procurator and in 1175 became Abbot of the first Carthusian monastery in England. This had been built by King Henry II as part of his penance for the murder of Thomas Becket.

His reputation for holiness and sanctity spread all over England and attracted many to the monastery. He admonished Henry for keeping Sees vacant to enrich the royal coffers. Income from the vacant Sees went to the royal treasury. He was then named bishop of the eighteen year old vacant See of Lincoln in 1186 - a post he accepted only when ordered to do so by the prior of the Grande Chartreuse. Hugh quickly restored clerical discipline, labored to restore religion to the diocese, and became known for his wisdom and justice.

He was one of the leaders in denouncing the persecution of the Jews that swept England, 1190-91, repeatedly facing down armed mobs and making them release their victims. He went on a diplomatic mission to France for King John in 1199, visiting the Grande Chartreuse, Cluny, and Citeaux, and returned from the trip in poor health. A few months later, while attending a national council in London, he was stricken and died two months later at the Old Temple in London on November 16. He was canonized twenty years later, in 1220, the first Carthusian to be so honored.

The Charterhouse St. Hugh of Lincoln led was at Witham in Somerset and this site provides details of St. Hugh's founding, really of the priory, since so little had been done when he arrived:

It was probably in 1179 (fn. 83) that at the request of Henry II a few Carthusian monks, how many we do not know, left their home near Grenoble to found in England the first house of their order. Norbert (fn. 84) came as the leader of the band and the first prior of the new house and with him Aynard and one Gerard of Nevers. But no preparations had been made for them, the villein tenants did not welcome them, for they were foreigners, nor did they agree, except after compensation, to be removed from their houses and lands. For the monks themselves no shelter had been provided. So very soon Prior Norbert gave up in despair and returned to Carthusia, regarding it as impossible to establish a house there unless they had more support than the king seemed disposed to give. In succession to him another, whose name is not given, was sent forth, and he died soon after from exposure and the severity of the climate. Then it was that Henry II took up the matter with some earnestness. He was arranging a marriage for his son John with Agnes the daughter of Humbert III Count of Maurienne and he asked the latter's advice concerning the difficulties at Witham. Count Humbert mentioned Hugh of Avalon, already the foremost of the monks of Carthusia, as the man most likely to succeed, though he warned Henry how he was valued, and how difficult it would be to get him to leave his monastery and come to England. Henry nevertheless persevered and sent Reginald, Bishop of Bath, and others on the errand to the monastery to ask definitely for Hugh of Avalon. At first the prior was unwilling to part with him, (fn. 85) for he was procurator of the house and much valued, and Hugh on his part regarding himself as unfit to undertake the task, definitely refused his consent; but the Bishop of Grenoble, John de Sassenage, had been won over, probably by Bishop Reginald, and at his entreaty the prior gave way and Hugh of Avalon started for England. On his arrival, which seems to have been in 1180, he found that nothing had been done at Witham and all practically had to be begun towards the new foundation. He stipulated that the tillers of the soil, the poor villein tenants, should receive no loss in being compelled to change their abode, and he endeavoured to persuade the king to indemnify them for the houses they had built, which now had to be pulled down. Certainly he seems to have set about the work in earnest, obtaining only after constant pressure on Henry II the necessary means. He is said to have built houses for the monks and the lay brethren, and the metrical life of St. Hugh records that he built the walls of the chapel and vaulted it in stone. The existing church at Witham is generally regarded as the church of the Conversi or lay brethren. The walls seem older than the time of Hugh, and apparently had buttresses attached to them for the purpose of strengthening them to carry the weight of the stone roof.

The last prior and 12 monks surrendered Witham on the 15th of March in 1539, received their pensions--and avoided the fate of many of the Carthusians of the Charterhouse of London, and the priories at Beauvale and Axholme.

Published on November 16, 2013 22:30

Tintern Abbey: The Ruins and Wordsworth's Memories

Tintern Abbey's ruins are a great tourist destination now, per this website:

The appeal of this exceptional Cistercian abbey remains as enduring as ever

An area of outstanding beauty complemented by this outstanding beauty in stone. If only the walls could talk! The chants of countless monks echo through the masonry here. Despite the shell of this grand structure being open to the skies, it remains the best-preserved medieval abbey in Wales. Although the abbey church was rebuilt under the patronage of Roger Bigod, lord of nearby Chepstow Castle, in the late 13th century, the monastery retains its original design.

Tintern was only the second Cistercian foundation in Britain, and the first in Wales. The present-day remains are a mixture of building works covering a 400-year period between 1131 and 1536. Very little remains of the first buildings but you will marvel at the vast windows and later decorative details displayed in the walls, doorways and soaring archways.

The lands of the abbey were divided into agricultural units or granges, worked on by lay brothers.

On September 3, 1536 Abbot Wyche surrendered Tintern Abbey to King Henry VIII’s officials and ended a way of life which had lasted 400 years.

There’s a lot still going on at Tintern Abbey 500 years on! A major two-year programme of conservation work has been completed on the iconic 13th-century west front – one of the great glories of Gothic architecture in Britain. The statue of Our Lady of Tintern is installed in the south aisle of the abbey for all to see.

If only the Blessed Sacrament and the Altar and the Work of God could be restored there--not just the statue of Our Lady of Tintern--and the ruin not just echo with the memories of chant!

It was on July 13 in 1789 that William Wordsworth and his sister Mary visited Tintern Abbey and as David Lehman writes in The Wall Street Journal, William then wrote a great Romantic poem about memory and nature: "Lines composed a few miles above Tintern Abbey, on revisiting the banks of the Wye during a tour". Lehman tells us why it is a great work of art. The poem

presents the crisis of melancholy, specifically the melancholy over the passing of youth. If the majestic prospect of a ruined 12th-century church on the Welsh side of the River Wye triggers the meditation, the landscape's fourth dimension—time as an almost palpable presence—dominates it. Five years have gone by since the poet last stood here. Now his thoughts turn naturally to the changes since then and to trepidations over what may ensue.

Wordsworth has a fierce nostalgia for boyhood—"when like a roe / I bounded o'er the mountains, by the sides / Of the deep rivers, and the lonely streams, / Wherever nature led." But the reality principle is strong in him; he shuts off the reverie in four curt syllables: "That time is past." The crisis is solved, the melancholy fit cured, by the key apprehension of a divinity located not in the remote heavens but on earth, in nature. The conviction that there is "a motion and a spirit that impels / All thinking things, all objects of all thought, / And rolls through all things" expresses itself with the force of a soul-restoring epiphany. . . . The poem is a triumph emotionally. The seemingly spontaneous overflow of feelings in the last movement of the poem—the prayer addressed to Dorothy Wordsworth—may bring tears to your eyes. I know no finer or more tender expression of a man's love for his sister. The poem is a triumph, too, of the "cheerful faith" that reconciles us to losses and compensates for them. It comes as close as Wordsworth ever did to achieving a metrical ideal: the language approaching prose, with the fixed meter acting as a firm restraint.

You may find the text of the poem here.

Image Credit: Wikipedia Commons

Published on November 16, 2013 22:30

November 15, 2013

Froude's Remains and the Oxford Martyrs Memorial

Image Credit: Wikipedia Commons

Image Credit: Wikipedia CommonsOn October 16, 1555, Protestant bishops Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley were burned at the stake in Oxford, having been tried and convicted of heresy during the reign of Queen Mary I. In 1843, a Gothic style memorial, designed by George Gilbert Scott, was erected at the intersection of St. Gile's, Magdalen and Beaumont streets near Balliol College. Why was the memoral erected 288/287 years after the martyrdom of Latimer, Ridley, and Thomas Cranmer (executed on March 21, 1556)? Why did the memorial include such a pointedly anti-Catholic dedication?

To the Glory of God, and in grateful commemoration of His servants, Thomas Cranmer, Nicholas Ridley, Hugh Latimer, Prelates of the Church of England, who near this spot yielded their bodies to be burned, bearing witness to the sacred truths which they had affirmed and maintained against the errors of the Church of Rome, and rejoicing that to them it was given not only to believe in Christ, but also to suffer for His sake; this monument was erected by public subscription in the year of our Lord God, MDCCCXLI.

The memorial project was launched in response to the Oxford Movement and the publication of Richard Hurrell Froude's Remains, which demonstrated the late Oriel Fellow's interest in some Catholic devotions, in 1838, two years after his death. Newman and Keble, when editing the Remains, included a Preface containing strong denials tht Froude would have considered becoming a Catholic! Nevertheless, the Reverend Charles Pourtales Golightly (who did not "go lightly"), formerly John Henry Newman's curate at St. Mary's-St. Nicholas' in Littlemore, and other evangelical Anglicans were alarmed by the Romanizing tendencies of the Oxford Movement (Sacraments, sacramentals, and saints) and even more angered by some of Froude's comments: particularly his regrets that the Reformation--particularly the English Reformation--had ever happened. Golightly began the subscription campaign to build the memorial as an effort to counter and protest the Oxford Movement.

Golightly and Newman had a Huguenot background in common and they had been acquaintances for a long time, and Golightly was independently wealthy and therefore could take on poor Anglican parishes and do many good works. He was completely opposed to the ritualistic aspects of the Oxford Movement. It seems curious that Sir Gilbert Scott built the memorial in the Gothic style, since many could identify Gothic with the Catholic Middle Ages, but Scott did not equate Gothic with solely ecclesiastical architecture. He also designed the Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens across from the Royal Albert Hall. It also displays Scott's interest in the Gothic Revival style.

It's also interesting to note that in 1843 when the Martyrs Monument was dedicated, Newman was in Littlemore at the College and by September of that year had resigned from St. Mary's and was working on the Development of Christian Doctrine, writing himself into the Catholic Church.

Published on November 15, 2013 23:00

British and Colonial Anti-Popery

Reflecting on Guy Fawkes day in colonial America, author and politician Daniel Hannon makes these surprising comments in

The Catholic Herald

--surprising in that a culture that feared Catholicism (Papistry/Popery) as inimical to freedom and liberty yet realized that religious freedom was necessary and that Catholics must be able to practice their faith:

Reflecting on Guy Fawkes day in colonial America, author and politician Daniel Hannon makes these surprising comments in

The Catholic Herald

--surprising in that a culture that feared Catholicism (Papistry/Popery) as inimical to freedom and liberty yet realized that religious freedom was necessary and that Catholics must be able to practice their faith: Guy Fawkes Night used to be popular in North America, especially in Massachusetts. We have excised that fact from our collective memory, as we have more generally the bellicose anti-Catholicism that powered the American Revolution. We tell ourselves that the argument was about “No taxation without representation” and, for some, it was. But while constitutional questions obsessed the pamphleteering classes whose words we read today, the masses were more exercised by the perceived threat of superstition and idolatry that had sparked their ancestors’ hegira across the Atlantic in the first place. They were horrified by the government’s decision, in 1774, to recognise the traditional rights of the Catholic Church in Quebec.

To many Nonconformists, it seemed that George III was sending the popish serpent after them into Eden. As the First Continental Congress put it in its resolutions: “The dominion of Canada is to be so extended that by their numbers daily swelling with Catholic emigrants from Europe, and by their devotion to Administration, so friendly to their religion, they might become formidable to us, and on occasion, be fit instruments in the hands of power, to reduce the ancient free Protestant Colonies to the same state of slavery with themselves.”

Puritans and Presbyterians saw Anglicanism, with its stately communions and surplices and altar rails, as more than half allied to Rome. There had been a furious reaction in the 1760s when the Archbishop of Canterbury sought to bring the colonists into the fold. Thomas Secker, who had been born a Dissenter, and had the heavy-handed zeal of a convert, had tried to set up an Anglican missionary church in, of all places, Cambridge, Massachusetts, capital of New England Congregationalism. He sought to strike down the Massachusetts Act, which allowed for Puritan missionary work among the Indians and, most unpopular of all, to create American bishops.

The ministry backed off, but trust was never recovered. As the great historian of religion in America, William Warren Sweet, put it: “Religious strife between the Church of England and the Dissenters furnished the mountain of combustible material for the great conflagration, while the dispute over stamp, tea and other taxes acted merely as the matches of ignition.”

John Adams is remembered today as a humane and decent man – which he was. We forget that he earnestly wondered: “Can a free government possibly exist with the Roman Catholic religion?” Thomas Jefferson’s stirring defences of liberty move us even now. Yet he was convinced that “in every country and in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty. He is always in alliance with the despot, abetting his abuses in return for protection to his own.”

Americans had, as so often, distilled to greater potency a tendency that was present throughout the English-speaking world: an inchoate but strong conviction that Catholicism threatened freedom. Daniel Defoe talked of “a hundred thousand country fellows prepared to fight to the death against Popery, without knowing whether it be a man or a horse”. Anti-Catholicism was not principally doctrinal: few people were much interested in whether you believed in priestly celibacy or praying for the souls of the dead. Rather, it was geopolitical. . . .

And here’s the almost miraculous thing: they ended up creating a uniquely individualist culture that endured when religious practice waned. Adams and Jefferson led the first state in the world based on true religious freedom (as opposed to toleration). From a spasm of sectarianism came, paradoxically, pluralism. And, once it had come, it held on. “I never met an English Catholic who did not value, as much as any Protestant, the free institutions of his country,” wrote an astonished Tocqueville.

The title of Daniel Hannan's forthcoming book is Inventing Freedom: How the English-Speaking Peoples Made the Modern World--I wonder how he will interpret the so-called Glorious Revolution? Will he acknowledge James II and the campaign for religious toleration and freedom of conscience or will he repeat the old canards about William and Mary invading to defeat tyranny?

Published on November 15, 2013 22:30

November 14, 2013

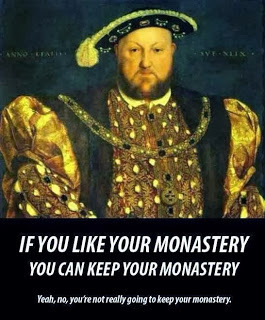

November 15, 1539: No, You Cannot Keep Your Monasteries

This image has been making the rounds on various facebook pages and blogs, comparing President Obama's promises about insurance while campaigning for the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare) to Henry VIII and the Dissolution of the Monasteries. (You might recall that comparisons between Henry VIII and President Obama have come up before in the context of the HHS Mandates on contraceptive, abortafacient, and sterilization coverage.) I don't think that Henry VIII--whose only campaigns were military--ever made such a promise, but certainly on this day, November 15, in 1539, the Abbots of Glastonbury and Reading Abbeys found out that they could not keep their monasteries open. Blessed Richard Whiting, Blessed John Thorne, and Blessed Roger James were executed on Glastonbury Tor near their empty and soon to be desolated abbey, and Blessed Hugh (Cook) Faringdon, Blessed John Rugg and Blessed John Eynon were executed at Reading Abbey.

Glastonbury was one of the richest abbeys in the kingdom, and one of the best run and most observant of the Rule of St. Benedict: it was a ripe target for Henry VIII, Thomas Cromwell, and the Court of Augmentations. Cromwell had to trump up some charges against the elderly abbot. Both Abbot Whiting and Abbot Faringdon of Reading Abbey had gone along with Henry VIII's claims of supremacy over the Ecclesiae Anglicanae, but when they refused to surrender their monasteries, they surrended their lives.

More about the martyrs at Glastonbury here and about those at Reading . Perhaps their martyrdoms expiated their guilt for denying the authority of Christ's Vicar on earth: These six martyrs of the Dissolution of the Monasteries on November 15, 1539 (three each at Reading and Glastonbury) represent in some ways the remorse of the abbots and abbey leadership, who had accepted Henry VIII's oaths that proclaimed his authority over the Church of England as Supreme Head and Governor. Somehow they did not realize or imagine what he could and would do with that power and authority.

Published on November 14, 2013 22:30

November 13, 2013

Speaking of Coincidences! Two Champions of Religious Toleration Born

Two allies in the effort to bring religious toleration and freedom of conscience to England were born on the same date, in 1633 and 1644, respectively: James, the Duke of York (later James II) and William Penn, the Quaker founder of Pennsylvania.

Two allies in the effort to bring religious toleration and freedom of conscience to England were born on the same date, in 1633 and 1644, respectively: James, the Duke of York (later James II) and William Penn, the Quaker founder of Pennsylvania.On October 14, 1633, King Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria welcomed the birth of their second son and third child, further securing the succession. James was titled the Duke of York. During the English Civil War he was captured by Fairfax but escaped to Holland.

He served in the armies of France and of Spain while on the Continent after the fall of the monarchy and the execution of his father. He secretly married Anne Hyde, the daughter of Lord Clarendon in 1660, but continued his womanizing ways. Anne bore him two daughters, Mary and Anne. When Charles II returned to England and the throne, James became the Lord High Admiral and declared himself a Catholic in 1672.

Anne Hyde, the Duchess of York had also become a Catholic and died in 1671--James then married Mary Beatrice of Modena, a Catholic Italian princess. Of course, the crucial event of his life--at least as it influenced his reign--was the birth of his only son, James Francis Edward on June 10, 1688. In combination with his efforts to make religious toleration and freedom of conscience the law the in England, this birth of a Catholic prince led to the Glorious Revolution, as his daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange deposed him in 1688.

His reputation for courage in battle suffered after the invasion of William of Orange. He panicked and fled for France. Before the Battle of the Boyne he suffered nose bleeds and did not execute a successful battle plan. The Encyclopedia Britannica in 1910 offered this harsh assessment:

"The political ineptitude of James is clear; he often showed firmness when conciliation was needful, and weakness when resolution alone could have saved the day. Moreover, though he mismanaged almost every political problem with which he personally dealt, he was singularly tactless and impatient of advice. But in general political morality he was not below his age, and in his advocacy of toleration decidedly above it. He was more honest and sincere than Charles II, more genuinely patriotic in his foreign policy, and more consistent in his religious attitude. That his brother retained the throne while James lost it is an ironical demonstration that a more pitiless fate awaits the ruler whose faults are of the intellect, than one whose faults are of the heart."

The line, "But in general political morality he was not below his age, and in his advocacy of toleration decidedly above it" does give James the credit he deserves although it does not go far enough. James did not just advocate toleration or tolerance; his Declaration of Indulgence addresses freedom of conscience for his subjects.

Also, as I have alluded to Edward Corps' The Court in Exile before, he seems to have repented both for the moral harm he did in being unfaithful to both his wives and for the political errors he made in ruling while he lived in France at St. Germain-en-Laye. James became prayerful and devout, and more sincerely lived up to his religious beliefs. James II's ally in the campaign for religious liberty and freedom of conscience was William Penn, born on November 14 in 1644. He was an early Quaker leader, the founder of Pennsylvania, and, in a way, the founder of Philadelphia, according to this wikipedia article. On October 21, 1692William and Mary removed him from the governorship of Pennsylvania, accusing him of being a Papist--all because he had worked with James II on religious freedom in England.

Published on November 13, 2013 22:30

November 12, 2013

St. Anthony of Padua in Scotland and England

As my husband and I attend Sunday Mass nearly every week at the Church of St. Anthony of Padua, this news about the relics of that great saint in Scotland and England caught my attention. As

The Catholic Herald

notes,

As my husband and I attend Sunday Mass nearly every week at the Church of St. Anthony of Padua, this news about the relics of that great saint in Scotland and England caught my attention. As

The Catholic Herald

notes, Catholics filled Westminster Cathedral on Saturday to venerate the relics of St Anthony of Padua.

The arrival of the saint’s relics, which comprised a small piece of petrified flesh and a layer of skin from the saint’s cheek, was part of a UK tour marking the 750th anniversary of the discovery of St Anthony’s incorrupt tongue.

Following an afternoon of veneration, where pilgrims queued for hours outside the cathedral in order to visit the relics, Archbishop Vincent Nichols of Westminster celebrated Mass in honour of the great saint.

During his homily, Archbishop Nichols said that St Anthony was a guide to those who have lost their way. He said: “On this most fundamental of all journeys we often get lost, taking a wrong path, ending up in a cul-de-sac, distracted by bright lights or misjudgement. St Anthony is well known for helping us to find lost things. And he can help us in this way too. He can help us to find again our true path whenever we have lost our way.”

[I'm not surprised that Archbishop Nichols has supported the veneration of these relics, as he urged Catholics throughout England to visit an exhibition at the British Museum in 2011 on relics and reliquaries:

All British Catholics should try to visit the new exhibition of relics and reliquaries at the British Museum in London, Archbishop Vincent Nichols of Westminster has said.

Treasures of Heaven: saints, relics and devotion in medieval Europe opened in the historic Round Reading Room at the museum today.

“I think this is a very, very unique and remarkable exhibition. There are objects here, for example the Mandylion, the face of Christ, which will never leave the Vatican again,” the archbishop said.

“I would just urge Catholics in England and Wales and from further afield to make the effort to come to the British Museum some time between now and October to take up this very unique opportunity. It’s a once-in-a-lifetime, and it’s well worth the journey.”]

The relics of St. Anthony continue their journey through Scotland and England, as The Catholic Herald continues:

Following their visit to Westminster Cathedral, the relics’ tour concluded at St Peter’s Italian Church in Clerkenwell. It is estimated that the relics have attracted 250,000 people across the UK during their tour.

Prior to their arrival at Westminster Cathedral, St Anthony’s relics had visited Belfast, Glasgow, Aberdeen, Newcastle, Manchester, Liverpool and Chester.

During their veneration at the Franciscan Church in Chester, the Church of St Francis, Bishop Mark Davies of Shrewsbury reminded pilgrims that they were too called to be saints.

Addressing a packed church last Thursday, Bishop Davies said: “In Rome yesterday Pope Francis reminded us of the startling fact that the term ‘saint’ refers to you and to me, to everyone who believes in the Lord Jesus and are incorporated in Him and in the Church through Baptism. We are to be all saints!”

St. Anthony of Padua, pray for us!

Image: Guercino's St Anthony of Padua with the Infant Christ.

Published on November 12, 2013 22:30

November 11, 2013

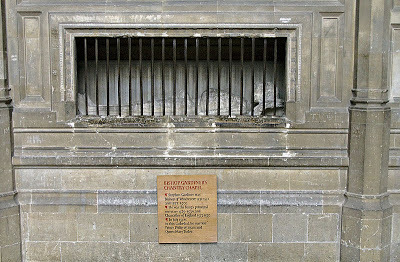

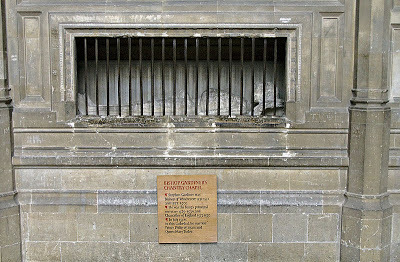

Bishop Stephen Gardiner, RIP

Stephen Gardiner, Mary I's Chancellor and the Bishop of Winchester, died on November 12, 1555. While he had supported Henry VIII's supremacy, he also opposed Edward VI's Calvinist Reformation, and then he assisted Mary I, and renounced his views on the supremacy, since that was a role she rejected. The 1910 Encyclopedia Britannica summed up his life and character thusly:

Perhaps no celebrated character of that age has been the subject of so much ill-merited abuse at the hands of popular historians. That his virtue was not equal to every trial must be admitted, but that he was anything like the morose and narrowminded bigot he is commonly represented there is nothing whatever to show. He has been called ambitious, turbulent, crafty, abject, vindictive, bloodthirsty and a good many other things besides, not quite in keeping with each other; in addition to which it is roundly asserted by Bishop Burnet that he was despised alike by Henry and by Mary, both of whom made use of him as a tool. How such a mean and abject character submitted to remain five years in prison rather than change his principles is not very clearly explained; and as to his being despised, we have seen already that neither Henry nor Mary considered him by any means despicable. The truth is, there is not a single divine or statesman of that day whose course throughout was so thoroughly consistent. He was no friend to the Reformation, it is true, but he was at least a conscientious opponent. In doctrine he adhered to the old faith from first to last, while as a question of church policy, the only matter for consideration with him was whether the new laws and ordinances were constitutionally justifiable.

His merits as a theologian it is unnecessary to discuss; it is as a statesman and a lawyer that he stands conspicuous. But his learning even in divinity was far from commonplace. The part that he was allowed to take in the drawing up of doctrinal formularies in Henry VIII's time is not clear; but at a later date he was the author of various tracts in defence of the Real Presence against Cranmer, some of which, being written in prison, were published abroad under a feigned name. Controversial writings also passed between him and Bucer, with whom he had several interviews in Germany, when he was there as Henry VIII's ambassador.

He was a friend of learning in every form, and took great interest especially in promoting the study of Greek at Cambridge. He was, however, opposed to the new method of pronouncing the language introduced by Sir John Cheke, and wrote letters to him and Sir Thomas Smith upon the subject, in which, according to Ascham, his opponents showed themselves the better critics, but he the superior genius. In his own household he loved to take in young university men of promise; and many whom he thus encouraged became distinguished in after life as bishops, ambassadors and secretaries of state. His house, indeed, was spoken of by Leland as the seat of eloquence and the special abode of the muses.

He lies buried in his own cathedral at Winchester, where his effigy is still to be seen. (Image credit for his chantry tomb: wikipedia commons.) His last words were: "I have erred with Peter, but have not wept with Peter." The bishop has been in the news lately, as an important document of the English Reformation was recently sold at auction, but its export has been prevented, per this story from The Guardian: A 16th-century manuscript that shines a light on a furious battle between two bishops of Winchester, over the then touchstone Reformation issue of clerical marriage, has had a temporary export bar placed on it. The culture minister, Ed Vaizey, announced the bar on Thursday in the hope that someone will find the money to keep the manuscript in the UK. The paper's abridged title is A Traictise declarying and plainly prouying, that the pretensed marriage of Priestes … is no mariage (1554), and was sold by the Law Society at Sotheby's in June for £116,500 , nearly six times the upper estimate. The manuscript contains two diametrically opposed positions on clerical marriage. There is the anti-marriage stance of Stephen Gardiner and the virulently pro-marriage opinions of John Ponet, one of Thomas Cranmer's righthand men and a key figure in the English Reformation. It was Ponet who replaced Gardiner as bishop of Winchester in 1551, although his tenure lasted only two years, before he was forced to flee England when the Catholic Mary Tudor came to the throne in 1553. Gardiner then resumed the job. It's interesting to note that John Ponet survived Gardiner only by several months, as he died in August of 1556. Ponet argued for tyrannicide--specifically, the execution of Mary I--while in exile on the Continent in A Shorte Treatise of Politike Power.

Stephen Gardiner, Mary I's Chancellor and the Bishop of Winchester, died on November 12, 1555. While he had supported Henry VIII's supremacy, he also opposed Edward VI's Calvinist Reformation, and then he assisted Mary I, and renounced his views on the supremacy, since that was a role she rejected. The 1910 Encyclopedia Britannica summed up his life and character thusly:

Perhaps no celebrated character of that age has been the subject of so much ill-merited abuse at the hands of popular historians. That his virtue was not equal to every trial must be admitted, but that he was anything like the morose and narrowminded bigot he is commonly represented there is nothing whatever to show. He has been called ambitious, turbulent, crafty, abject, vindictive, bloodthirsty and a good many other things besides, not quite in keeping with each other; in addition to which it is roundly asserted by Bishop Burnet that he was despised alike by Henry and by Mary, both of whom made use of him as a tool. How such a mean and abject character submitted to remain five years in prison rather than change his principles is not very clearly explained; and as to his being despised, we have seen already that neither Henry nor Mary considered him by any means despicable. The truth is, there is not a single divine or statesman of that day whose course throughout was so thoroughly consistent. He was no friend to the Reformation, it is true, but he was at least a conscientious opponent. In doctrine he adhered to the old faith from first to last, while as a question of church policy, the only matter for consideration with him was whether the new laws and ordinances were constitutionally justifiable.

His merits as a theologian it is unnecessary to discuss; it is as a statesman and a lawyer that he stands conspicuous. But his learning even in divinity was far from commonplace. The part that he was allowed to take in the drawing up of doctrinal formularies in Henry VIII's time is not clear; but at a later date he was the author of various tracts in defence of the Real Presence against Cranmer, some of which, being written in prison, were published abroad under a feigned name. Controversial writings also passed between him and Bucer, with whom he had several interviews in Germany, when he was there as Henry VIII's ambassador.

He was a friend of learning in every form, and took great interest especially in promoting the study of Greek at Cambridge. He was, however, opposed to the new method of pronouncing the language introduced by Sir John Cheke, and wrote letters to him and Sir Thomas Smith upon the subject, in which, according to Ascham, his opponents showed themselves the better critics, but he the superior genius. In his own household he loved to take in young university men of promise; and many whom he thus encouraged became distinguished in after life as bishops, ambassadors and secretaries of state. His house, indeed, was spoken of by Leland as the seat of eloquence and the special abode of the muses.

He lies buried in his own cathedral at Winchester, where his effigy is still to be seen. (Image credit for his chantry tomb: wikipedia commons.) His last words were: "I have erred with Peter, but have not wept with Peter." The bishop has been in the news lately, as an important document of the English Reformation was recently sold at auction, but its export has been prevented, per this story from The Guardian: A 16th-century manuscript that shines a light on a furious battle between two bishops of Winchester, over the then touchstone Reformation issue of clerical marriage, has had a temporary export bar placed on it. The culture minister, Ed Vaizey, announced the bar on Thursday in the hope that someone will find the money to keep the manuscript in the UK. The paper's abridged title is A Traictise declarying and plainly prouying, that the pretensed marriage of Priestes … is no mariage (1554), and was sold by the Law Society at Sotheby's in June for £116,500 , nearly six times the upper estimate. The manuscript contains two diametrically opposed positions on clerical marriage. There is the anti-marriage stance of Stephen Gardiner and the virulently pro-marriage opinions of John Ponet, one of Thomas Cranmer's righthand men and a key figure in the English Reformation. It was Ponet who replaced Gardiner as bishop of Winchester in 1551, although his tenure lasted only two years, before he was forced to flee England when the Catholic Mary Tudor came to the throne in 1553. Gardiner then resumed the job. It's interesting to note that John Ponet survived Gardiner only by several months, as he died in August of 1556. Ponet argued for tyrannicide--specifically, the execution of Mary I--while in exile on the Continent in A Shorte Treatise of Politike Power.

Published on November 11, 2013 22:30

November 10, 2013

Luytens and Curzon Remember "The Glorious Dead"

Our God, our help in ages past,Our hope for years to come,

Our God, our help in ages past,Our hope for years to come,Our shelter from the stormy blast,

And our eternal home.

Under the shadow of Thy throne

Thy saints have dwelt secure;

Sufficient is Thine arm alone,

And our defense is sure.

Before the hills in order stood,

Or earth received her frame,

From everlasting Thou art God,

To endless years the same.

Thy Word commands our flesh to dust,

“Return, ye sons of men:”

All nations rose from earth at first,

And turn to earth again.

A thousand ages in Thy sight

Are like an evening gone;

Short as the watch that ends the night

Before the rising sun.

The busy tribes of flesh and blood,

With all their lives and cares,

Are carried downwards by the flood,

And lost in following years.

Time, like an ever rolling stream,

Bears all its sons away;

They fly, forgotten, as a dream

Dies at the opening day.

Like flowery fields the nations stand

Pleased with the morning light;

The flowers beneath the mower’s hand

Lie withering ere ‘tis night.

Our God, our help in ages past,

Our hope for years to come,

Be Thou our guard while troubles last,

And our eternal home. Bruce Cole writes in The Wall Street Journal how England remembers "The Glorious Dead" of WWI: both with the Cenotaph designed by Edwin Lutyens and the ceremony prepared by Lord Curzon of Kedleston. First, the monument, with the note that it depicts no overt religious symbolism, and yet that many saw religious symbolism in the empty "tomb": The Cenotaph struck a deep emotional chord. In a memo to the War Cabinet just four days after the Peace Day parade, Mond noted the "growing public" interest in a permanent Cenotaph and wrote that Lutyens was eager to design it "on the same line." The War Cabinet, which included Winston Churchill, approved the new Cenotaph. Few monuments of such distinction have been conceived in such haste and built with such speed.

Other than replicating the wood and plaster with Portland limestone there was almost no change in the design, except for one important refinement: entasis, a principle used by the ancient Greeks, in which vertical lines are given a slightly convex curve as they taper upward to fool the eye, which would otherwise see them as out of true alignment. The result was a minimal but sophisticated arrangement of shapes, moldings and setbacks derived from classical prototypes. Bereft of any overt religious, national or didactic symbolism, its power arose solely from its stark, somber, unadorned form.

The Cenotaph's unveiling on Nov. 11, 1920, was heightened by another solemn commemoration: the burial of the Unknown Warrior, whose body was returned from France for entombment in Westminster Abbey to memorialize the thousands still missing.

Draped with two large Union Jacks, the Cenotaph was unveiled by George V as the gun carriage bearing the Unknown Warrior stopped at the monument on its way to the Abbey. Thus, the memorial function of the Cenotaph, crowned by an empty sarcophagus, was heightened by the presence of an unknown soldier. Relatives of the missing were comforted because, as they said, it was possible to believe that he might be their husband, son, father or brother. For many, the vacant tomb of Lutyens's Cenotaph would recall Christ's resurrection and its embodiment of salvation for their fallen

Describing the ceremony, the Times of London reported that Big Ben "boomed out, louder, it seemed, than ever one hears it even in the stillness of dawn." The king "released the flags...they fell away, and it stood, clean and wonderful in its naked beauty. Big Ben ceased; and the very pulse of Time stood still. In silence, broken only by a near-by sob, the great multitude bowed its head." And then Cole describes the ceremony for the dedication of the Cenotaph, which has become the ceremony for each Remembrance Day:

The dedication ceremony designed for the new Cenotaph gave increased meaning to the monument. The event was planned by a member of the War Cabinet, Lord Curzon of Kedleston, an epitome of English aristocracy and privilege. As Viceroy of India, he was the impresario of the great Delhi Durbar of 1903, a spectacular two-week pageant of Imperial pageantry featuring a cast of thousands.

Curzon, who had organized the events around the unveiling of the temporary Cenotaph, was now asked to design the ceremony for the dedication of its successor. But if anyone thought he would create a majestic procession, they were wrong.

Instead, he produced something very different, a service of the utmost modesty and sobriety that would complement Lutyens's austere monument. The ceremony would be minimal, poignant and brief: the hymn "O God Our Help in Ages Past," the doleful "Last Post," and two minutes of silence, not of prayer but in memory of the fallen. Some nine decades later, Curzon's touching ceremony is still celebrated at the Cenotaph on Britain's annual Remembrance Day.

Curzon insisted that the ceremony should be for veterans and war widows. Similarly, places for the service in the Abbey, he declared, were to be assigned not to "society ladies or the wives of dignitaries, but to the selected widows and mothers of those who had fallen, especially in the humbler ranks."

This aligned with the widespread democratic appeal of the Cenotaph, which neither proclaims victory nor sentimentalizes the fallen, but instead brilliantly evokes the loss of millions. This explanation makes me think of one advantage of having a national Church: the inclusion of a beautiful Christian hymn, Isaac Watts "O God Our Help in Ages Past", based on Psalm 90, as part of a national ceremony. England may have grown more secular since that "war to end all wars" but the hymn is still part of the ceremony. Image source: wikipedia commons.

Published on November 10, 2013 22:30

November 9, 2013

Blessed Dominic Barberi, Pray for us!

Fr John Kearns, the Provincial of the Congregation of the Passion of Jesus Christ in England and Wales wrote on the legacy of Blessed Dominic Barberi in

The Catholic Herald

as the Passionists recently celebrated the 50th anniversary of the beatification of Blessed Dominic by Pope Paul VI:

Blessed Dominic is remembered by many Catholics simply as the priest who received Blessed John Henry Newman into the Church. But he was far more than that: during Dominic’s Mass of beatification on October 27 1963 Pope Paul VI noted that he had “more than one claim to outstanding merit”, that he was a theologian, a philosopher, and had anticipated elements of the First Vatican Council.

Years earlier, in 1926, Cardinal Francis Bourne of Westminster had been even more effusive. “Of all the preachers of the divine Word who have worked for the salvation of souls in England,” the cardinal wrote, “there is no one, in our opinion, to whom we are more indebted than the Servant of God, Dominic of the Mother of God. I should consider myself happy if I had the power and right to dedicate this whole diocese to his care and protection, and be allowed to honour him as our patron and protector of England.”

Dominic’s encounter with Newman at Littlemore in Oxfordshire, in October 1845, may perhaps be only a small part of his story, but it is important nevertheless. This is because Newman himself tells us that he entered the Catholic Church precisely at that moment because of the supernatural qualities he recognised instantly in the Italian missionary. “When his form came into sight, I was moved to the depths in the strangest way,” he wrote years later. “His very look had about it something holy.” Church scholars today acknowledge that the sanctity of Blessed Dominic confirmed for Newman what he had come to believe intellectually about the Catholic faith.

Father Kearns also points out that:

It is surely no accident that Dominic Barberi was beatified during the Second Vatican Council. One of the Council’s themes was to prepare the Church for effective mission in the modern world, as noted by Archbishop Bernard Longley of Birmingham, during a recent Mass at Dominic’s tomb in St Helens. Archbishop Longley said that Blessed Dominic provides us with a great model for such mission. For that reason he was named by the archdiocese as a patron of the Year of Faith, inaugurated to mark the 50th anniversary of the Council.

Blessed Dominic’s example first and foremost represents a call to holiness. It is this witness of life, this experience of goodness, that attracts people to Christ above all else. For us, it means interior conversion, a theme constantly proposed by Pope Francis: to heal, to bring Christ to others, we must ourselves first be holy.

Note that the cause for Blessed Dominic's canonization is active, and in fact has been renewed by the Archdiocese of Birmingham!

Catholics are being asked to pray for the intercession of Blessed Dominic Barberi in the hope that the second miracle needed for his canonisation might soon be found. . . .

Passionist Fr Benedict Lodge, postulator of Blessed Dominic’s Cause for Canonisation, has appealed for prayers for miracles at the intercession of the Italian missionary at a time when his life will be remembered.

He said that several reports of alleged miraculous healings at the intercession of Blessed Dominic have fallen short of the rigorous criteria applied by theologians and medics and none is at present under investigation.

“What better way to both celebrate the 50th anniversary of the beatification of Blessed Dominic and the Year of Faith than to find the miracle that would lead to the canonisation of this great man who did so much to enkindle the Catholic faith in this country?” said Fr Lodge.

Blessed Dominic is remembered by many Catholics simply as the priest who received Blessed John Henry Newman into the Church. But he was far more than that: during Dominic’s Mass of beatification on October 27 1963 Pope Paul VI noted that he had “more than one claim to outstanding merit”, that he was a theologian, a philosopher, and had anticipated elements of the First Vatican Council.

Years earlier, in 1926, Cardinal Francis Bourne of Westminster had been even more effusive. “Of all the preachers of the divine Word who have worked for the salvation of souls in England,” the cardinal wrote, “there is no one, in our opinion, to whom we are more indebted than the Servant of God, Dominic of the Mother of God. I should consider myself happy if I had the power and right to dedicate this whole diocese to his care and protection, and be allowed to honour him as our patron and protector of England.”

Dominic’s encounter with Newman at Littlemore in Oxfordshire, in October 1845, may perhaps be only a small part of his story, but it is important nevertheless. This is because Newman himself tells us that he entered the Catholic Church precisely at that moment because of the supernatural qualities he recognised instantly in the Italian missionary. “When his form came into sight, I was moved to the depths in the strangest way,” he wrote years later. “His very look had about it something holy.” Church scholars today acknowledge that the sanctity of Blessed Dominic confirmed for Newman what he had come to believe intellectually about the Catholic faith.

Father Kearns also points out that:

It is surely no accident that Dominic Barberi was beatified during the Second Vatican Council. One of the Council’s themes was to prepare the Church for effective mission in the modern world, as noted by Archbishop Bernard Longley of Birmingham, during a recent Mass at Dominic’s tomb in St Helens. Archbishop Longley said that Blessed Dominic provides us with a great model for such mission. For that reason he was named by the archdiocese as a patron of the Year of Faith, inaugurated to mark the 50th anniversary of the Council.

Blessed Dominic’s example first and foremost represents a call to holiness. It is this witness of life, this experience of goodness, that attracts people to Christ above all else. For us, it means interior conversion, a theme constantly proposed by Pope Francis: to heal, to bring Christ to others, we must ourselves first be holy.

Note that the cause for Blessed Dominic's canonization is active, and in fact has been renewed by the Archdiocese of Birmingham!

Catholics are being asked to pray for the intercession of Blessed Dominic Barberi in the hope that the second miracle needed for his canonisation might soon be found. . . .

Passionist Fr Benedict Lodge, postulator of Blessed Dominic’s Cause for Canonisation, has appealed for prayers for miracles at the intercession of the Italian missionary at a time when his life will be remembered.

He said that several reports of alleged miraculous healings at the intercession of Blessed Dominic have fallen short of the rigorous criteria applied by theologians and medics and none is at present under investigation.

“What better way to both celebrate the 50th anniversary of the beatification of Blessed Dominic and the Year of Faith than to find the miracle that would lead to the canonisation of this great man who did so much to enkindle the Catholic faith in this country?” said Fr Lodge.

Published on November 09, 2013 22:30