Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 251

December 15, 2013

Kings Over the Water and their Supporters' "Material Culture"

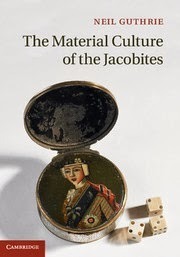

Coming soon from Cambridge University Press: The Material Culture of the Jacobites by Neil Guthrie:

Coming soon from Cambridge University Press: The Material Culture of the Jacobites by Neil Guthrie:The Jacobites, adherents of the exiled King James II of England and VII of Scotland and his descendants, continue to command attention long after the end of realistic Jacobite hopes down to the present. Extraordinarily, the promotion of the Jacobite cause and adherence to it were recorded in a rich and highly miscellaneous store of objects, including medals, portraits, pin-cushions, glassware and dice-boxes. Interdisciplinary and highly illustrated, this book combines legal and art history to survey the extensive material culture associated with Jacobites and Jacobitism. Neil Guthrie considers the attractions and the risks of making, distributing and possessing ‘things of danger’; their imagery and inscriptions; and their place in a variety of contexts in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Finally, he explores the many complex reasons underlying the long-lasting fascination with the Jacobites.

The Cambridge University Press website contains several .pdfs of excerpts from the book, including the Table of Contents:

Introduction

1. 'By things themselves': the danger of Jacobite material culture

2. 'Many emblems of sedition and treason': patterns of Jacobite visual symbolism

3. 'Their disloyal and wicked inscriptions': the uses of texts on Jacobite objects

4. 'Tempora mutantur et nos mutamur in illis': phases and varieties of Jacobite material culture

5. 'Those who are fortunate enough to possess pictures and relics': later uses of Jacobite material culture

Bibliography

The National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia has an exhibition now of one of the most common Jacobite objects: the glassware used to toast the true Kings of England:

So the Stuart supporters, or Jacobites, instituted, amongst other things, the practice of drinking toasts to their King “over the water” in glasses engraved with cryptic symbols which reflected their Stuart loyalties.

The NGV possesses an extensive and important collection of these rare glasses, many of them generous gifts from the Morgan family of Melbourne. Kings over the water will explore the fascinating hidden symbolism of these beautiful objects, created as part of a doomed political adventure whose tragic history continues to cast a romantic spell even today.

The exhibition site includes an essay on the glassware's manufacture and use, detailing the symbols etched in glass to represent the Stuart claimants:

Jacobite glasses were decorated with engraved cryptic symbols and mottos which, to those who understood their coded messages, spoke of the drinker’s loyalty to the Stuart dynasty. By far the most common symbol was the six-petalled white heraldic rose, an ancient emblem of the Stuarts. The white rose also had connotations of strict legitimacy. Its adoption by James III as his personal badge was particularly appropriate as rumours of his illegitimacy had been circulated by political enemies since his birth.

On its own, the white rose is believed to have stood for the exiled king. A rose bud to the right of the rose represented his heir apparent, Prince Charles Edward Stuart. A second rosebud, to the left of the rose, represented Prince Henry Benedict Stuart, Princes Charles’s younger brother. When there are two rosebuds, that representing Prince Charles is often larger and on the verge of opening.

And the Latin mottoes:

Audentior Ibo (I shall go more boldly). This motto probably derived from the sixth book of Virgil’s Aeneid, in which Aeneas consults a mystic who warns him of grim fighting to come, but adds ‘sed contra audentior ito’ (‘but go forth against it with great daring’).Radiat (It shines).Redeat (May he return). This motto appears on a medal with a bust of Prince Charles, struck in 1752 for the Oak Society.Rede (Return!).Redi. Perhaps an abbreviation of Redii (I have returned).Reditti (Restore).Revirescit (It revives).Fiat (May it come to pass). This is also a Latin equivalent of ‘Amen’.Turno Tempus Erit (For Turnus there shall be a time). Turnus is a character in Virgil’s Aeneid who struggles against Aeneas for mastery of Italy. Aeneas defeats Turnus in battle and is inclined to spare his life, but notices that Turnus wears the sword of a friend of his whom he has killed. Aeneas slays Turnus in revenge. Turnus may be meant to stand for the Duke of Cumberland, who defeated the Jacobites at Culloden. The glass warns that the Hanoverian victory may be short lived.Hic Vir Hic Est (This, this is the man). This motto derives from the sixth book of Virgil’s Aeneid. After the fall of Troy, Aeneas escapes to Italy where he is permitted to descend into the underworld in order to gain a glimpse of the future. He sees the coming glory of Rome, and the appearance of Augutus Caesar is heralded with the phrase Hic Vir Hic Est.

Published on December 15, 2013 22:30

December 14, 2013

Johannes Vermeer, RIP, December 15, 1675

Believe it or not, there is a connection between the death of Johannes Vermeer and the English Reformation, the topic of this blog! The connection is the relationship between Church and State, always fraught with difficulty, but especially when the State chooses an official church and religion. The artist Johannes Vermeer became a Catholic when he married, and this site notes:

Believe it or not, there is a connection between the death of Johannes Vermeer and the English Reformation, the topic of this blog! The connection is the relationship between Church and State, always fraught with difficulty, but especially when the State chooses an official church and religion. The artist Johannes Vermeer became a Catholic when he married, and this site notes:By the time Vermeer's parents were married in 1615, the suppression of the public celebration of the Catholic faith in Delft was complete. But even though national decrees denied Catholics the right to serve public office, many areas of the Netherlands remained solidly Roman Catholic. Despite the hostility, Dutch Catholics continued to worship and educate their children throughout the 17th century. In large cities like Amsterdam, Haarlem and Utrecht, commercial concerns dampened repeated calls for anti-Catholic laws. Although intolerance existed in the United Provinces, on the whole Dutch Catholics enjoyed remarkable freedoms compared with religious minorities elsewhere in early modern Europe. Penal laws against Catholics were occasionally enforced and Catholics were vulnerable to extortion, but things could have been far worse.

Vermeer very probably converted to Catholicism upon his marriage to Catharina Bolnes [in 1653] and there is no sign that his decision had negative repercussions on his career. The most influential painter in Delft and friend of the Vermeer family, Leonaert Bramer as well as the popular painter of Dutch family life, Jan Steen were noted Catholics.

So, like Catholics in England, Catholics in the Netherlands had to worship secretly--that line "things could have been far worse" might indeed be applied to English Catholics during the 17th century. Since this painting dates to 1670-1672, English Catholics were still under the Penal and Recusancy laws that made it an act of treason for a priest to be in England and a felony for a layperson to assist a Catholic priest in any way--although there was a hiatus in the persecution of Catholics during those years of Charles II's reign. It would start up again after the Fire of London and while Titus Oates' nefarious conspiracy of a conspiracy ran its perjurous course.

Catholics in the Netherlands were allowed to worship in schiulkerk, or hidden churches, as long as they kept it quiet.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City has this Vermeer currently on display. Its description:

One of Vermeer's most unusual pictures, this large canvas was probably commissioned by a Catholic patron. The subject was adopted from a standard handbook of iconography, Cesare Ripa's "Iconologia." Vermeer interpreted Ripa's description of Faith with the "world at her feet" literally, showing a Dutch globe published in 1618. The divine world is suggested by the glass sphere hanging overhead. The painting of the Crucifixion on the wall copies a work by Jacob Jordaens. Among the several Christological symbols, the most prominent are the apple, emblem of the first sin, and the serpent (Satan) crushed by a stone (Christ, the "cornerstone" of the church). Dating from about 1670, the work strikes a balance between abstraction and haunting similitude.

Painted about 1670–72, this picture presents an allegory of Vermeer's adopted religion, and was probably made expressly for a private Catholic patron or for a schuilkerk, a hidden Catholic church. It is unlike any other work by Vermeer, though it shows compositional similarities to The Art of Painting (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) of about 1666–68. The latter work is also allegorical in subject, but only nominally, as it was intended mainly as a virtuosic display of the artist's abilities. In the MMA canvas, Vermeer shifts his late style towards a more classicist and schematic manner.

The choice and interpretation of the imagery included here would have been discussed by the artist and his patron. For many of the allegorical motifs, Vermeer must have turned to Cesare Ripa's emblem book, Iconologia (Rome, 1603), translated in a Dutch edition by Dirck Pietersz Pers (Amsterdam, 1644). The female figure represents the Catholic Faith, wearing white, a symbol of purity, and blue, the "hue of heaven". A hand raised to the heart indicates the source of living faith. She rests her foot on a globe, published in 1618 by Jodocus Hondius, to illustrate Ripa's description of Faith with "the world under her feet". In the foreground, Vermeer shows the "cornerstone" of the Church (Christ) crushing a serpent (Satan). The nearby apple, which has been bitten, stands for original sin. The table is transformed into an altar with the addition of a chalice, crucifix, and a Bible or, more likely because of its proximity to other objects used for the Mass, a missal. The glass sphere, hanging from a ribbon, was a popular decorative curiosity; in this context, it may be viewed as a symbol of heaven or God. The room itself, with its high ceiling, marble floor, and a large altarpiece based on a work by Jacob Jordaens (possibly identical with one in Vermeer's estate), was meant to be recognized by contemporary viewers as a private chapel installed within a large house or some other secular building. Though apparently an illusionistic device, the tapestry at left would also have been understood as part of a very large hanging, drawn aside to reveal a normally secluded space.

This book, published by Harvard University Press, covers the era: Faith on the margins: Catholics and Catholicism in the Dutch Golden Age by Charles H. Parker and this book even compares the two minority communities of Catholics in England and the Netherlands. And Vermeer is in the news with the release of Tim's Vermeer , a movie about a man's efforts to figure out how Vermeer composed his paintings so perfectly balancing light and shadow, using a camera obscura.

Published on December 14, 2013 22:30

December 13, 2013

William Oddie on the Ordinariate Liturgy

William Oddie was once an Anglican and he recently attended a Mass at an Ordinariate church and then wrote about it in

The Catholic Herald

:

I had never once felt, since my conversion, that I missed Anglicanism: the Church of England had become so awful, so impossible for anyone tending in a Catholic direction, that I was far more conscious, when I made my submission nearly 25 years ago, of how wonderful it was to be a Catholic. But I had forgotten, after my youthful atheism, how wonderful I thought so much of Anglicanism was, after the dry, dry desert of actual unbelief. One thing I loved was the setting of the Ordinary of the Eucharist (as I always called it before I discovered the excitements of Anglo-Catholicism) by the composer John Merbecke. This was Cranmer’s translation set to a kind of reformed plainchant (one note to a syllable), which though deriving from Gregorian chant eschewed its (I think wonderful) peripatetic longeurs. On Advent Sunday, I sang the creed to Merbecke for the first time in nearly 30 years: it all came back as though it was yesterday, and it was wonderfully moving. Another unexpectedly wonderful bonus I hadn’t anticipated was the entire absence of the suppressed irritation I so often feel at the debased English of the readings in the Roman Missal from the Jerusalem Bible: the readings, of course, were from the Authorised version, the King James Bible, now authorised afresh for liturgical use by our dear Pope Benedict.

I could go on about how splendid it all was. It was not just a voyage of rediscovery, however: it was also a realisation anew of how lifegiving a thing it is to belong to a Church which determines and teaches with authority what theological meaning actually is. Cranmer’s freshly composed prayers (as opposed to his translations from the Sarum rite, as with the Ordinary of the Mass and many of his collects) are sometimes written in deliberately ambiguous language, so as to be acceptable to a distinctly, even dangerously, various public, some members of it — then as now — radically Protestant but many of them still resentfully Catholic at heart. Again and again, you come across phrases which can be read in either a Catholic or a Protestant way. The authorisation of the use of such prayers by the Congregation for Divine Worship, quite simply removes the ambiguities.

Read the rest here.

I had never once felt, since my conversion, that I missed Anglicanism: the Church of England had become so awful, so impossible for anyone tending in a Catholic direction, that I was far more conscious, when I made my submission nearly 25 years ago, of how wonderful it was to be a Catholic. But I had forgotten, after my youthful atheism, how wonderful I thought so much of Anglicanism was, after the dry, dry desert of actual unbelief. One thing I loved was the setting of the Ordinary of the Eucharist (as I always called it before I discovered the excitements of Anglo-Catholicism) by the composer John Merbecke. This was Cranmer’s translation set to a kind of reformed plainchant (one note to a syllable), which though deriving from Gregorian chant eschewed its (I think wonderful) peripatetic longeurs. On Advent Sunday, I sang the creed to Merbecke for the first time in nearly 30 years: it all came back as though it was yesterday, and it was wonderfully moving. Another unexpectedly wonderful bonus I hadn’t anticipated was the entire absence of the suppressed irritation I so often feel at the debased English of the readings in the Roman Missal from the Jerusalem Bible: the readings, of course, were from the Authorised version, the King James Bible, now authorised afresh for liturgical use by our dear Pope Benedict.

I could go on about how splendid it all was. It was not just a voyage of rediscovery, however: it was also a realisation anew of how lifegiving a thing it is to belong to a Church which determines and teaches with authority what theological meaning actually is. Cranmer’s freshly composed prayers (as opposed to his translations from the Sarum rite, as with the Ordinary of the Mass and many of his collects) are sometimes written in deliberately ambiguous language, so as to be acceptable to a distinctly, even dangerously, various public, some members of it — then as now — radically Protestant but many of them still resentfully Catholic at heart. Again and again, you come across phrases which can be read in either a Catholic or a Protestant way. The authorisation of the use of such prayers by the Congregation for Divine Worship, quite simply removes the ambiguities.

Read the rest here.

Published on December 13, 2013 22:30

December 12, 2013

The Wise Virgins and the Advent of the Bridegroom

The Parable of the Ten Bridesmaids; Matthew, chapter 25 “Then the kingdom of heaven shall be compared to ten maidens who took their lamps and went to meet the bridegroom.[a] 2 Five of them were foolish, and five were wise. 3 For when the foolish took their lamps, they took no oil with them; 4 but the wise took flasks of oil with their lamps. 5 As the bridegroom was delayed, they all slumbered and slept. 6 But at midnight there was a cry, ‘Behold, the bridegroom! Come out to meet him.’ 7 Then all those maidens rose and trimmed their lamps. 8 And the foolish said to the wise, ‘Give us some of your oil, for our lamps are going out.’ 9 But the wise replied, ‘Perhaps there will not be enough for us and for you; go rather to the dealers and buy for yourselves.’ 10 And while they went to buy, the bridegroom came, and those who were ready went in with him to the marriage feast; and the door was shut. 11 Afterward the other maidens came also, saying, ‘Lord, lord, open to us.’ 12 But he replied, ‘Truly, I say to you, I do not know you.’ 13 Watch therefore, for you know neither the day nor the hour. (RSV)

The Parable of the Ten Bridesmaids; Matthew, chapter 25 “Then the kingdom of heaven shall be compared to ten maidens who took their lamps and went to meet the bridegroom.[a] 2 Five of them were foolish, and five were wise. 3 For when the foolish took their lamps, they took no oil with them; 4 but the wise took flasks of oil with their lamps. 5 As the bridegroom was delayed, they all slumbered and slept. 6 But at midnight there was a cry, ‘Behold, the bridegroom! Come out to meet him.’ 7 Then all those maidens rose and trimmed their lamps. 8 And the foolish said to the wise, ‘Give us some of your oil, for our lamps are going out.’ 9 But the wise replied, ‘Perhaps there will not be enough for us and for you; go rather to the dealers and buy for yourselves.’ 10 And while they went to buy, the bridegroom came, and those who were ready went in with him to the marriage feast; and the door was shut. 11 Afterward the other maidens came also, saying, ‘Lord, lord, open to us.’ 12 But he replied, ‘Truly, I say to you, I do not know you.’ 13 Watch therefore, for you know neither the day nor the hour. (RSV)The German chorale Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme by Philipp Nicolai, a 16th century Lutheran hymnist and pastor, reflects on Our Lord's counsel to "Watch therefore, for you know neither the day nor the hour." Note that the music for the hymn was written by Hans Sachs, one of Wagner's Meistersingers.

Catherine Winkworth translated the hymn in the 19th century:

1. Wake, awake, for night is flying,

The watchmen on the heights are crying;

Awake, Jerusalem, at last!

Midnight hears the welcome voices,

And at the thrilling cry rejoices:

Come forth, ye virgins, night is past!

The Bridegroom comes, awake,

Your lamps with gladness take;

Hallelujah!

And for His marriage-feast prepare,

For ye must go to meet Him there.

2. Zion hears the watchmen singing,

And all her heart with joy is springing,

She wakes, she rises from her gloom;

For her Lord comes down all-glorious,

The strong in grace, in truth victorious,

Her Star is risen, her Light is come!

Ah come, Thou blessed Lord,

O Jesus, Son of God,

Hallelujah!

We follow till the halls we see

Where Thou hast bid us sup with Thee!

3. Now let all the heavens adore Thee,

And men and angels sing before Thee,

With harp and cymbal's clearest tone;

Of one pearl each shining portal,

Where we are with the choir immortal

Of angels round Thy dazzling throne;

Nor eye hath seen, nor ear

Hath yet attain'd to hear

What there is ours,

But we rejoice, and sing to Thee

Our hymn of joy eternally.

Published on December 12, 2013 23:00

An Advent Hymnn for Christ's Second Coming: The Dies Irae

If we think of the Dies Irae, The Day of Wrath, we think of it as the sequence in the Catholic Requiem Mass according to the Extraordinary Form of the Latin Rite--but it is the ultimate Advent hymn to proclaim Christ's Second Coming, which the first part of Advent anticipates. Here is a translation by the Very Reverend James Ambrose Dominic Aylward:

That day of wrath and grief and shame, Shall fold the world in sheeted flame,

As psalm and Sibyl songs proclaim.

What terror on each breast shall lie

When, downward from the bending sky,

The judge shall come our souls to try.

The trump, through death's dominions blown,

Shall summon with a dreadful tone

The buried nations round the throne.

Nature and death in dumb surprise

Shall see the ancient dead arise,

To stand before the judge's eyes.

And lo, the written book appears,

Which all that faithful record bears,

From whence the world its sentence hears.

The Lord of judgment sits him down,

And every secret thing makes known ;

No crime escapes his vengeful frown.

Ah, how shall I that day endure ?

What patron's friendly voice secure,

When scarce the just themselves are sure ?

O king of dreadful majesty,

Who grantest grace and mercy free,

Grant mercy now and grace to me.

Good Lord, 'twas for my sinful sake,

That thou our suffering flesh didst take ;

Then do not now my soul forsake.

Thou soughtest me when I had strayed ;

Thy blood divine my ransom paid ;

Shall all that love be fruitless made ?

O just avenging judge, I pray,

For pity take my sins away,

Before the great accounting-day.

I groan beneath the guilt, which thou

Canst read upon my blushing brow ;

But spare, O God, thy suppliant now.

Thou, who didst Mary's sins unbind,

And mercy for the robber find,

Dost fill with hope my anxious mind.

Though worthless all my prayers appear, S

till let me not, my Saviour dear,

The everlasting burnings bear.

Give me at thy right hand a place,

Amongst thy sheep, a child of grace, Far from the goats' accursed race.

Yea, when thy justly kindled ire Shall bind the lost in chains of fire, Oh, call me to thy chosen choir.

Lo, here I plead and suppliant bend, Nor cease my contrite heart to rend, That so thou spare me in the end.

Oh, on that day, that day of weeping, When man shall wake from death's dark sleeping, To stand before his judge divine,

Save, save this trembling soul of mine : Yea, grant to all, O Saviour blest, Who die in thee, the saints' sweet rest.

The original sequence is attributed to Thomas of Celano, a Franciscan from the thirteenth century. The translator, the Very Reverend James Ambrose Dominic Aylward, was a

Theologian and poet, born at Leeds, 4 April, 1813; died at Hinckley (England), 5 October, 1872. He was educated at the Dominican priory of Hinckley, entered the Order of St. Dominic, was ordained priest in 1836, became provincial in l850, first Prior of Woodchester in 1854, and provincial a second time in 1866. He composed several pious manuals for the use of his community and "A Novena for the Holy Season of Advent" gathered from the prophecies, anthems, etc., of the Roman Missal and Breviary (Derby, 1849). He reedited (London, 1867) a "Life of Blessed Virgin St. Catherine of Sienna", translated from the Italian by the Dominican Father John Fen (Louvain, 1609), also an English translation of Father Chocarne's "Inner Life of Lacordaire" (Dublin, 1867). His essays '' On the Mystical Elements in Religion, and on Old and Modern Spiritism " were edited posthumously by Cardinal Manning (London, 1874). Father Aylward's principal monument is his translation of Latin hymns, most of which he contributed to "The Catholic Weekly Instructor." In his "Annus Sanctus" (London, 1884) Orbey Shipley has reprinted many of them. He says of Father Aylward that he was "a cultivated and talented priest of varied powers and gifts."

Published on December 12, 2013 22:30

December 10, 2013

Christmas Carols on the BBC

The BBC (Radio 4) is broadcasting a series on Christmas Carols:

The Christmas carol is as popular now as it was when carolers celebrated the birth of Edward III in 1312. Back then the carol was a generic term for a song with its roots in dance form, nowadays only the strictest scholar would quibble with the fact that a carol is a Christmas song.

But the journey the carol has taken is unique in music history because each shift in the story has been preserved in the carols that we sing today. Go to a carol concert now and you're likely to hear folk, medieval, mid-victorian and modern music all happily combined. It's hard to imagine that happening in any other situation.

In these programmes Jeremy Summerly follows the carol journey through the Golden age of the Medieval carol into the troubled period of Reformation and puritanism, along the byways of the 17th and 18th century waits and gallery musicians and in to the sudden explosion of interest in the carol in the 19th century. It's a story that sees the carol veer between the sacred and secular even before there was any understanding of those terms. For long periods the church, both catholic and protestant, was uneasy about the virility and homespun nature of carol tunes and carol texts. Nowadays many people think that church music is defined by the carols they hear from Kings College Cambridge.

He traces the folk carol in and out of church grounds, the carol hymn, the fuguing carol and the many other off-shoots, some of which survive to this day and many others which languish unloved but ready for re-discovery.

You may listen to the first episode for the next six days.

The Christmas carol is as popular now as it was when carolers celebrated the birth of Edward III in 1312. Back then the carol was a generic term for a song with its roots in dance form, nowadays only the strictest scholar would quibble with the fact that a carol is a Christmas song.

But the journey the carol has taken is unique in music history because each shift in the story has been preserved in the carols that we sing today. Go to a carol concert now and you're likely to hear folk, medieval, mid-victorian and modern music all happily combined. It's hard to imagine that happening in any other situation.

In these programmes Jeremy Summerly follows the carol journey through the Golden age of the Medieval carol into the troubled period of Reformation and puritanism, along the byways of the 17th and 18th century waits and gallery musicians and in to the sudden explosion of interest in the carol in the 19th century. It's a story that sees the carol veer between the sacred and secular even before there was any understanding of those terms. For long periods the church, both catholic and protestant, was uneasy about the virility and homespun nature of carol tunes and carol texts. Nowadays many people think that church music is defined by the carols they hear from Kings College Cambridge.

He traces the folk carol in and out of church grounds, the carol hymn, the fuguing carol and the many other off-shoots, some of which survive to this day and many others which languish unloved but ready for re-discovery.

You may listen to the first episode for the next six days.

Published on December 10, 2013 22:30

December 9, 2013

December 10, 1591: Executions on Gray's Inn Road and at Tyburn

St. Swithun Wells was hanged for NOT attending a Catholic Mass in Elizabethan England. His wife Alice attended the Mass held in his house near Gray's Inn in London, but he wasn't there when the priest hunters burst in during the Mass celebrated by Father Edmund Gennings. Those attending held the pursuivants off. His wife, Fathers Gennings (pictured here) and Polydore Plasden, and three other laymen, John Mason, Sidney Hodgson, and Brian Lacey were arrested at the end of the Mass. Swithun was arrested when he came home.

St. Swithun Wells was hanged for NOT attending a Catholic Mass in Elizabethan England. His wife Alice attended the Mass held in his house near Gray's Inn in London, but he wasn't there when the priest hunters burst in during the Mass celebrated by Father Edmund Gennings. Those attending held the pursuivants off. His wife, Fathers Gennings (pictured here) and Polydore Plasden, and three other laymen, John Mason, Sidney Hodgson, and Brian Lacey were arrested at the end of the Mass. Swithun was arrested when he came home.At his trial, he said he wished he could have attended that Mass and that was enough for the Elizabethan authorities! He was hung near his home on Gray's Inn Road in London, and he spoke to Richard Topcliffe before he died, hoping that this persecutor and torturer of Catholics would convert! He said, "I pray God make you a Paul of a Saul, of a bloody persecutor one of the Catholic Church's children." St. Swithun as a school master had for a time conformed to the official church but then had returned to the Catholic faith.

As he was led to the scaffold, Wells saw an old friend in the crowd and called out to him: "Farewell, dear friend, farewell to all hawking, hunting, and old pastimes. I am now going a better way"!

St. Swithun's wife Alice received a reprieve from her death sentence, but died in prison in 1602. The two priests and the other three laymen were all executed on December 10. Sir Walter Raleigh was present at the execution and heard Father Polydore pray for Queen Elizabeth. Raleigh then asked him about his loyalty to Queen Elizabeth as the rightful ruler of England and liked his answers, so ordered him to be hung until dead, thus avoiding the rest of the torture of his execution. On the other hand, Topcliffe made sure that Father Gennings suffered all the tortures of being hung and quartered: he was left to hang but a short time and was fully conscious as the executioner started cutting him up. Father Gennings had said, "I know not ever to have offended the Queen. If to say Mass be treason, I confess to have done it and glory in it."

The two priests and the house owner have been canonized: St. Edmund Gennings, St. Polydore Plasden, and St. Swithun Wells--among the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales in 1970. The two laymen who helped defend St. Edmund Gennings at Mass and were sentenced to death for that felony (sic) were beatified (Blessed John Mason and Blessed Sidney Hodgson) by Pope Pius XI in 1929.

But these were not the only martyrdoms in London that day in 1591--Father Eustace White and layman Brian Lacey were executed at Tyburn. St. Eustace White was a convert to Catholicism--his anti-Catholic father cursed him and White endured permanent estrangement from his family. In 1584 Eustace began studies for the priesthood in Rheims, France and Rome, Italy, and was ordained at the Venerable English College in Rome in 1588. In November 1588 he returned to the west of England to minister to covert Catholics. The Church was going through a period of persecution in England, made even worse by the attack of the Armada from Catholic Spain. Arrested in Blandford, Dorset, England on 1 September 1591 for the crime of being a priest. He was lodged in Bridwell prison in London, and repeatedly tortured.

But these were not the only martyrdoms in London that day in 1591--Father Eustace White and layman Brian Lacey were executed at Tyburn. St. Eustace White was a convert to Catholicism--his anti-Catholic father cursed him and White endured permanent estrangement from his family. In 1584 Eustace began studies for the priesthood in Rheims, France and Rome, Italy, and was ordained at the Venerable English College in Rome in 1588. In November 1588 he returned to the west of England to minister to covert Catholics. The Church was going through a period of persecution in England, made even worse by the attack of the Armada from Catholic Spain. Arrested in Blandford, Dorset, England on 1 September 1591 for the crime of being a priest. He was lodged in Bridwell prison in London, and repeatedly tortured. He endured the torture technique developed by Richard Topcliffe and used on St. Robert Southwell and others, being hung by the wrists. As he wrote to Fr. Henry Garnet, SJ from prison:

"The morrow after Simon and Jude's day I was hanged at the wall from the ground, my manacles fast locked into a staple as high as I could reach upon a stool: the stool taken away where I hanged from a little after 8 o'clock in the morning until after 4 in the afternoon, without any ease or comfort at all, saving that Topcliffe came in and told me that the Spaniards were come into Southwark by our means: 'For lo, do you not hear the drums' (for then the drums played in honour of the Lord Mayor). The next day after also I was hanged up an hour or two: such is the malicious minds of our adversaries."

At his trial he forgave the judges who sentenced him to death. He is also one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales. You could read more about him in this book.

Brian Lacey was a Yorkshire country gentleman. Cousin, companion and assistant to Blessed Father Montford Scott. Arrested in 1586 for helping and hiding priests. Arrested again in 1591 when his own brother Richard betrayed him, Brian was tortured at Bridewell prison to learn the names of more people who had helped priests. Finally arraigned down the Old Bailey, he was condemed to death for his faith, for aiding priests and encouraging Catholic. Pope Pius XI also beatified him in 1929. Blessed Brian Lacey was also related to Blessed William Lacey, a 1582 martyr in York.

Published on December 09, 2013 22:30

December 8, 2013

Recreating Howard/Tudor Tombs in Norfolk

Again, from

The Daily Mail

, comes this story about the tombs built for Thomas Howard and his son-in-law, Henry Fitzroy, the Duke of Richmond:

Technology used to understand distant planets has helped reconstruct two ornate Tudor tombs that were destroyed during King Henry VIII's anti-Catholic offensive.

The tombs were commissioned by Thomas Howard, the third Duke of Norfolk, in the 16th century for Thetford Priory in Norfolk and when the priory was dissolved in 1540, some parts of the tombs were salvaged while others were abandoned in the ruins until they were excavated in the 1930s.

The Space Research Centre, part of the Leicester Department of Physics and Astronomy used these artefacts, along with drawings and 3D computer scanning technology that is currently used to construct how planets would have looked, to virtually reassemble two of the Howard Tombs.

Thomas Howard, the Third Duke of Norfolk, was one of Henry VIII's most ambitious nobles: he was scheduled for execution on charges of treason when Henry VIII died. His son was executed on the same charges, but Howard survived through the reign of Edward VI and into the reign of Mary I.

As British History Online describes, Thetford Priory was a Cluniac House dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, and the last prior hoped for survival, based on the Howard connections, and Thomas Howard had the same hope, based on Tudor connections:

On 26 March, 1537, Prior William wrote to Cromwell, in answer to his application for the preferment of his servant, John Myllsent, to their farm of Lynford. They begged to be excused, as their founder (patron), the Duke of Norfolk, had the custody of their convent seal. (fn. 49)

The Duke of Norfolk, the powerful patron of Thetford Priory, naturally looked with dismay upon the approaching destruction of this house and of the church, where not only his remote but more immediate ancestors had been honourably interred. His father, Sir Thomas Howard,earl of Surrey and duke of Norfolk, who died on 21 May, 1524, was buried before the high altar of the conventual church, where a costly monument to himself and Agnes his wife had been erected; whilst still more recently, in 1536, Henry Fitzroy, duke of Somerset, had been buried in the same place. As a means of preserving the church and establishment, the duke proposed to convert the priory into a church of secular canons, with a dean and chapter. In 1539 he petitioned the king to that effect, stating that there lay buried in that church the bodies of the Duke of Richmond, the king's natural son;the duke's late wife, Lady Anne, aunt to his highness; the late Duke of Norfolk and other of his ancestors; and that he was setting up tombs for himself and the duke of Richmond which would cost £400. He also promised to make it 'a very honest parish church.' At first the king gave ear to the proposal, and Thetford was included in a list with five others, of 'collegiate churches newly to be made and erected by the king.' Whereupon the duke had articles of a thorough scheme drawn up for insertion in the expected letters patent, whereby the monastery was to be translated into a dean and chapter.The dean was to be Prior William, (fn. 50) and the six prebendaries and eight secular canons were to be the monks of the former house, whose names are set forth in detail. The nomination of the dean was to rest with the duke and his heirs. The scheme included the appointment by the dean and chapter of a doctor or bachelor of divinity as preacher in the house, with a stipend of £20. (fn. 51) .

But the capricious king changed his mind,and insisted on the absolute dissolution of thepriory. The duke found that further resistance was hopeless, and on 16 February, 1540, PriorWilliam and thirteen monks signed a deed ofsurrender. (fn. 52) Two months later the site and the whole possessions of the priory passed to theDuke of Norfolk for £1,000, and by the service of a knight's fee and an annual rental of£59 5s. 1d. The bones of Henry's natural son,and of the late Duke of Norfolk and others, together with their tombs, were removed to anewly erected chancel of the Suffolk church of Framingham, and the grand church of St.Mary of Thetford speedily went to decay.

From: 'Houses of Cluniac monks: The priory of St Mary, Thetford', A History of the County of Norfolk: Volume 2 (1906), pp. 363-369.

As The Daily Mail article goes on to point out, quoting the leader of the project:

‘Our exhibition studies the catastrophic effects of the Dissolution of Thetford Priory and of Henry VIII's attempted destruction of Thomas Howard, third duke of Norfolk, on the ducal tomb-monuments at Thetford,’ said Dr Phillip Lindley, of the University of Leicester’s Department of the History of Art and Film.

‘Using 3D laser scanning and 3D prints, we have - virtually - dismantled the monuments at Framlingham and recombined them with the parts left at Thetford in 1540, to try to reconstruct the monuments as they were first intended, in a mixture of the virtual and the real.

‘The museum is a few hundred yards from the priory site where the tomb-monuments were first carved nearly five hundred years ago.'

The museum referred to is The Ancient House Museum in Thretford, Norfolk and this exhibition is part of the Representing Re-Formation project:

The Howard Tombs are key works in the development of sculpture in England and may well have been produced by sculptors from across the channel: certainly, they have been described as ‘outstanding examples of Franco-Italian sculptural influence’. Building on the foundations established by earlier scholars, we shall deploy conventional art-historical techniques – study of form, style and subject matter – supplementing them with a battery of approaches drawn from the humanities (specifically history and archaeology) and scientific techniques – such as 3-D scanning, XRF, and Raman spectroscopy, in a collaborative enterprise comprising researchers drawn from three universities and from English Heritage.

We aim to reconstruct the monuments’ original context at Thetford and to recover the Howards’ strategies to commemorate themselves and their predecessors during the reigns of the Tudor monarchs Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I. We shall study how the monuments were constructed, which components are missing and why, and will use digital interpretive media to display and interpret these complex 3D historical objects for a range of audiences. Together with the other research groups and with the assistance of Jan Summerfield of English Heritage and Oliver Bone and his team from the Norfolk Museums Service, we will be organising an exhibition in the Ancient House Museum in Thetford.

Technology used to understand distant planets has helped reconstruct two ornate Tudor tombs that were destroyed during King Henry VIII's anti-Catholic offensive.

The tombs were commissioned by Thomas Howard, the third Duke of Norfolk, in the 16th century for Thetford Priory in Norfolk and when the priory was dissolved in 1540, some parts of the tombs were salvaged while others were abandoned in the ruins until they were excavated in the 1930s.

The Space Research Centre, part of the Leicester Department of Physics and Astronomy used these artefacts, along with drawings and 3D computer scanning technology that is currently used to construct how planets would have looked, to virtually reassemble two of the Howard Tombs.

Thomas Howard, the Third Duke of Norfolk, was one of Henry VIII's most ambitious nobles: he was scheduled for execution on charges of treason when Henry VIII died. His son was executed on the same charges, but Howard survived through the reign of Edward VI and into the reign of Mary I.

As British History Online describes, Thetford Priory was a Cluniac House dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, and the last prior hoped for survival, based on the Howard connections, and Thomas Howard had the same hope, based on Tudor connections:

On 26 March, 1537, Prior William wrote to Cromwell, in answer to his application for the preferment of his servant, John Myllsent, to their farm of Lynford. They begged to be excused, as their founder (patron), the Duke of Norfolk, had the custody of their convent seal. (fn. 49)

The Duke of Norfolk, the powerful patron of Thetford Priory, naturally looked with dismay upon the approaching destruction of this house and of the church, where not only his remote but more immediate ancestors had been honourably interred. His father, Sir Thomas Howard,earl of Surrey and duke of Norfolk, who died on 21 May, 1524, was buried before the high altar of the conventual church, where a costly monument to himself and Agnes his wife had been erected; whilst still more recently, in 1536, Henry Fitzroy, duke of Somerset, had been buried in the same place. As a means of preserving the church and establishment, the duke proposed to convert the priory into a church of secular canons, with a dean and chapter. In 1539 he petitioned the king to that effect, stating that there lay buried in that church the bodies of the Duke of Richmond, the king's natural son;the duke's late wife, Lady Anne, aunt to his highness; the late Duke of Norfolk and other of his ancestors; and that he was setting up tombs for himself and the duke of Richmond which would cost £400. He also promised to make it 'a very honest parish church.' At first the king gave ear to the proposal, and Thetford was included in a list with five others, of 'collegiate churches newly to be made and erected by the king.' Whereupon the duke had articles of a thorough scheme drawn up for insertion in the expected letters patent, whereby the monastery was to be translated into a dean and chapter.The dean was to be Prior William, (fn. 50) and the six prebendaries and eight secular canons were to be the monks of the former house, whose names are set forth in detail. The nomination of the dean was to rest with the duke and his heirs. The scheme included the appointment by the dean and chapter of a doctor or bachelor of divinity as preacher in the house, with a stipend of £20. (fn. 51) .

But the capricious king changed his mind,and insisted on the absolute dissolution of thepriory. The duke found that further resistance was hopeless, and on 16 February, 1540, PriorWilliam and thirteen monks signed a deed ofsurrender. (fn. 52) Two months later the site and the whole possessions of the priory passed to theDuke of Norfolk for £1,000, and by the service of a knight's fee and an annual rental of£59 5s. 1d. The bones of Henry's natural son,and of the late Duke of Norfolk and others, together with their tombs, were removed to anewly erected chancel of the Suffolk church of Framingham, and the grand church of St.Mary of Thetford speedily went to decay.

From: 'Houses of Cluniac monks: The priory of St Mary, Thetford', A History of the County of Norfolk: Volume 2 (1906), pp. 363-369.

As The Daily Mail article goes on to point out, quoting the leader of the project:

‘Our exhibition studies the catastrophic effects of the Dissolution of Thetford Priory and of Henry VIII's attempted destruction of Thomas Howard, third duke of Norfolk, on the ducal tomb-monuments at Thetford,’ said Dr Phillip Lindley, of the University of Leicester’s Department of the History of Art and Film.

‘Using 3D laser scanning and 3D prints, we have - virtually - dismantled the monuments at Framlingham and recombined them with the parts left at Thetford in 1540, to try to reconstruct the monuments as they were first intended, in a mixture of the virtual and the real.

‘The museum is a few hundred yards from the priory site where the tomb-monuments were first carved nearly five hundred years ago.'

The museum referred to is The Ancient House Museum in Thretford, Norfolk and this exhibition is part of the Representing Re-Formation project:

The Howard Tombs are key works in the development of sculpture in England and may well have been produced by sculptors from across the channel: certainly, they have been described as ‘outstanding examples of Franco-Italian sculptural influence’. Building on the foundations established by earlier scholars, we shall deploy conventional art-historical techniques – study of form, style and subject matter – supplementing them with a battery of approaches drawn from the humanities (specifically history and archaeology) and scientific techniques – such as 3-D scanning, XRF, and Raman spectroscopy, in a collaborative enterprise comprising researchers drawn from three universities and from English Heritage.

We aim to reconstruct the monuments’ original context at Thetford and to recover the Howards’ strategies to commemorate themselves and their predecessors during the reigns of the Tudor monarchs Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I. We shall study how the monuments were constructed, which components are missing and why, and will use digital interpretive media to display and interpret these complex 3D historical objects for a range of audiences. Together with the other research groups and with the assistance of Jan Summerfield of English Heritage and Oliver Bone and his team from the Norfolk Museums Service, we will be organising an exhibition in the Ancient House Museum in Thetford.

Published on December 08, 2013 22:30

December 6, 2013

The Sound of Music: The Original Version?

You might have watched the live production of Rodgers & Hammerstein's stage version on NBC on Thursday, December 5--and that was the crucial note about the broadcast: that it was of the stage version. Too many people in on-line comments said the live version did not measure up to the original (the Julie Andrew's movie), not realizing that they had never seen the original: Mary Martin and Theodore Bikel as the Maria and the Captain in the last musical play that Rodgers & Hammerstein wrote together. I think many viewers expected a remake of the movie. What we saw was the (almost) original order and selection of the songs from the stage play--no "I Have Confidence in Me" (which Rodgers wrote for the movie). I was disappointed that they did not include "An Ordinary Couple" from the stage play, but instead chose "Something Good", which Rodgers also wrote (lyrics and music) for the movie.

I have not heard the soundtrack from the 1998 Broadway revival with Rebecca Luker but I did hear her sing "The Hills Are Alive" on the Kennedy Honors program for Julie Andrews. That revival included both "I Have Confidence in Me" and "Something Good" from the movie and the two songs for Elsa Schrader and Max Detweiler ("How Can Love Survive" and "There's No Way to Stop It"). The last song is really important to the plot because Elsa sings herself right out of her engagement to Captain von Trapp--and she knows it immediately.

For a really complete version of all the music for The Sound of Music, I guess the Telarc 1987 studio cast album wraps it all up: all the songs from both stage and screen. Frederica von Stade, Haken Hagegard, Eileen Farrell (the Abbess), and Barbara Daniels (Elsa Schrader) make up a strong vocal cast. Erich Kunzel, the late great conductor of the Cincinnati Pops did present a series of concert versions of the musical so there was some performing background for the opera stars. Except for Farrell (who did have a pop recording career along with her operatic career), the others sang operetta during their stage careers so they weren't completely unfamiliar with the musical form. Barbara Daniels sang Mama Rose and Dolly Levy!

Of course the movie version is what we think of first for this musical--and as I've watched it over the years, much as I have loved the music, it's the performance of Eleanor Parker as Baroness Schrader that I've appreciated more and more. She plays that role so brilliantly, because she doesn't let you hate her when you almost should. Even as she encourages Julie Andrews to leave and run back to the Abbey, it's clear that she is surprised at how right she is: the Captain and Maria do love each other, and "There's no Way to Stop It". She has some of the best lines in the movie--"Why didn't you tell me to bring my harmonica?"; the line about helping Maria becoming a nun in the Abbey, and even her breaking up with Georg: delicacy and some real strength of character there. Here's some that coincidential-connection trivia: Eleanor Parker played the role of opera singer Marjorie Lawrence in the 1955 movie Interrupted Melody, and Eileen Farrell, who sang the part of the Abbess on the Telarc CD, dubbed her opera performances.

Published on December 06, 2013 23:30

The Sound of Music

You might have watched the live production of Rodgers & Hammerstein's stage version on NBC on Thursday, December 5--and that was the crucial note about the broadcast: that it was of the stage version. Too many people in on-line comments said the live version did not measure up to the original (the Julie Andrew's movie), not realizing that they had never seen the original: Mary Martin and Theodore Bikel as the Maria and the Captain in the last musical play that Rodgers & Hammerstein wrote together. I think many viewers expected a remake of the movie. What we saw was the (almost) original order and selection of the songs from the stage play--no "I Have Confidence in Me" (which Rodgers wrote for the movie). I was disappointed that they did not include "An Ordinary Couple" from the stage play, but instead chose "Something Good", which Rodgers also wrote (lyrics and music) for the movie.

I have not heard the soundtrack from the 1998 Broadway revival with Rebecca Luker but I did hear her sing "The Hills Are Alive" on the Kennedy Honors program for Julie Andrews. That revival included both "I Have Confidence in Me" and "Something Good" from the movie and the two songs for Elsa Schrader and Max Detweiler ("How Can Love Survive" and "There's No Way to Stop It"). The last song is really important to the plot because Elsa sings herself right out of her engagement to Captain von Trapp--and she knows it immediately.

For a really complete version of all the music for The Sound of Music, I guess the Telarc 1987 studio cast album wraps it all up: all the songs from both stage and screen. Frederica von Stade, Haken Hagegard, Eileen Farrell (the Abbess), and Barbara Daniels (Elsa Schrader) make up a strong vocal cast. Erich Kunzel, the late great conductor of the Cincinnati Pops did present a series of concert versions of the musical so there was some performing background for the opera stars. Except for Farrell (who did have a pop recording career along with her operatic career), the others sang operetta during their stage careers so they weren't completely unfamiliar with the musical form. Barbara Daniels sang Mama Rose and Dolly Levy!

Of course the movie version is what we think of first for this musical--and as I've watched it over the years, much as I have loved the music, it's the performance of Eleanor Parker as Baroness Schrader that I've appreciated more and more. She plays that role so brilliantly, because she doesn't let you hate her when you almost should. Even as she encourages Julie Andrews to leave and run back to the Abbey, it's clear that she is surprised at how right she is: the Captain and Maria do love each other, and "There's no Way to Stop It". She has some of the best lines in the movie--"Why didn't you tell me to bring my harmonica?"; the line about helping Maria becoming a nun in the Abbey, and even her breaking up with Georg: delicacy and some real strength of character there. Here's some that coincidential-connection trivia: Eleanor Parker played the role of opera singer Marjorie Lawrence in the 1955 movie Interrupted Melody, and Eileen Farrell, who sang the part of the Abbess on the Telarc CD, dubbed her opera performances.

Published on December 06, 2013 23:30