Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 249

December 30, 2013

King of Angels or King of the English? Adeste Fideles/O Come All Ye Faithful

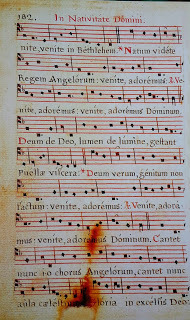

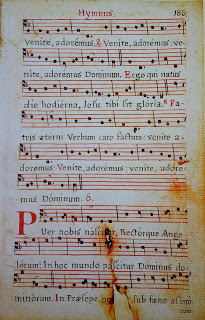

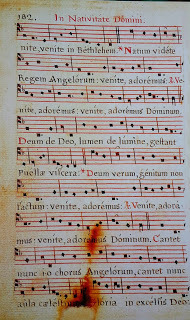

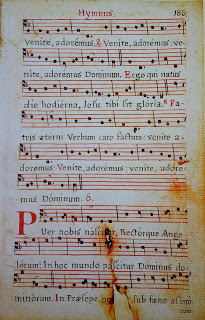

Because I sent a contribution to the Christian Heritage Centre at Stonyhurst in England, they sent me a Christmas card, signed by Lord and Lady Windsor, Nicholas and Paola. The art for the outside of the Christmas card is one of the manuscript copies of John Francis Wade's "Adeste, Fideles". My husband took the pictures below:

The most familiar translation of this hymn, which was written by Wade in 1750, is by Frederick Oakeley, an Oxford Movement follower of Blessed John Henry Newman, who joined the Catholic Church in 1845.

There is a very common theory that this hymn contains a code referring to Bonnie Prince Charlie--Wade was a Jacobite, and an exile in Europe after the '45. The BBC cites this expert, Bennett Zon of Durham University:

He said "clear references" to the prince were in the lyrics, written by John Francis Wade in the 18th Century. The prince was defeated at the Battle of Culloden in 1746 after raising an army to take the British throne.Born shortly before Christmas in December 1720, Bonnie Prince Charlie was the grandson of England's last Catholic monarch, James II. He was born in exile in Italy and became the focus for Catholic Jacobite rebels intent on restoring the House of Stuart to the British throne.

Prof Zon, said there was "far more" to the carol - also known as Adeste Fideles - than was originally thought.He said: "Fideles is Faithful Catholic Jacobites. Bethlehem is a common Jacobite cipher for England, and Regem Angelorum is a well-known pun on Angelorum, angels and Anglorum, English. "The meaning of the Christmas carol is clear: 'Come and Behold Him, Born the King of Angels' really means, 'Come and Behold Him, Born the King of the English' - Bonnie Prince Charlie." Professor Zon said the Jacobite meaning of the carol gradually faded as the cause lost its grip on popular consciousness.

This interpretation has been around for a long time, however, according to this site. I can accept the possible code in the first verse, but wonder about the rest of the hymn. Did John Francis Wade really intend his fellow Jacobites to think of Bonnie Prince Charlie as "Deum de Deo" (God from God), "Lumen de Lumine" (Light from Light)? I have my doubts about that! Canon Oakeley's translation:

O come, all ye faithful,

Joyful and triumphant,

O come ye, O come ye to Bethlehem;

Come and behold Him

Born the King of angels;

Chorus: O come, let us adore Him,

O come, let us adore Him,

O come, let us adore Him,

Christ the Lord.

God of God,

Light of Light;

Lo, He abhors not the Virgin's womb:

Very God,

Begotten, not created; Chorus.

Sing, choirs of angels;

Sking in exultation,

Sing, all ye citizens of heaven above;

Glory to God

In the highest; Chorus.

Yea, Lord, we greet Thee,

Born this happy morning:

Jesus, to Thee be glory given;

Word of the Father,

Late in flesh appearing; Chorus.

The most familiar translation of this hymn, which was written by Wade in 1750, is by Frederick Oakeley, an Oxford Movement follower of Blessed John Henry Newman, who joined the Catholic Church in 1845.

There is a very common theory that this hymn contains a code referring to Bonnie Prince Charlie--Wade was a Jacobite, and an exile in Europe after the '45. The BBC cites this expert, Bennett Zon of Durham University:

He said "clear references" to the prince were in the lyrics, written by John Francis Wade in the 18th Century. The prince was defeated at the Battle of Culloden in 1746 after raising an army to take the British throne.Born shortly before Christmas in December 1720, Bonnie Prince Charlie was the grandson of England's last Catholic monarch, James II. He was born in exile in Italy and became the focus for Catholic Jacobite rebels intent on restoring the House of Stuart to the British throne.

Prof Zon, said there was "far more" to the carol - also known as Adeste Fideles - than was originally thought.He said: "Fideles is Faithful Catholic Jacobites. Bethlehem is a common Jacobite cipher for England, and Regem Angelorum is a well-known pun on Angelorum, angels and Anglorum, English. "The meaning of the Christmas carol is clear: 'Come and Behold Him, Born the King of Angels' really means, 'Come and Behold Him, Born the King of the English' - Bonnie Prince Charlie." Professor Zon said the Jacobite meaning of the carol gradually faded as the cause lost its grip on popular consciousness.

This interpretation has been around for a long time, however, according to this site. I can accept the possible code in the first verse, but wonder about the rest of the hymn. Did John Francis Wade really intend his fellow Jacobites to think of Bonnie Prince Charlie as "Deum de Deo" (God from God), "Lumen de Lumine" (Light from Light)? I have my doubts about that! Canon Oakeley's translation:

O come, all ye faithful,

Joyful and triumphant,

O come ye, O come ye to Bethlehem;

Come and behold Him

Born the King of angels;

Chorus: O come, let us adore Him,

O come, let us adore Him,

O come, let us adore Him,

Christ the Lord.

God of God,

Light of Light;

Lo, He abhors not the Virgin's womb:

Very God,

Begotten, not created; Chorus.

Sing, choirs of angels;

Sking in exultation,

Sing, all ye citizens of heaven above;

Glory to God

In the highest; Chorus.

Yea, Lord, we greet Thee,

Born this happy morning:

Jesus, to Thee be glory given;

Word of the Father,

Late in flesh appearing; Chorus.

Published on December 30, 2013 22:30

December 29, 2013

Forty Days of Christmas? Oh, Yeah!

I agree with

A Clerk of Oxford

:

As a lover of carols, I'm much in favour of the medieval practice of keeping Christmas celebrations going all through the dark days of January, so today I thought I would post a carol which encourages us to keep singing throughout this season. It runs through not just the twelve days of Christmas but also the forty days of the Christmas season, all the way up to Candlemas, the Feast of the Purification, on February 2. It's a fifteenth-century carol (from Bodleian MS Eng. poet. e. I), and the unmodernised text can be found on this site , which also lists the various feasts mentioned: St Stephen on the 26th, St John on the 27th, the Holy Innocents on the 28th, St Thomas Becket on the 29th (check back soon for more carols about him!), the Circumcision of Christ on January 1st, Epiphany and Candlemas.

Make we mirth

For Christ's birth,

And sing we Yule til Candlemas.

1. The first day of Yule have we in mind,

How God was man born of our kind;

For he the bonds would unbind

Of all our sins and wickedness.

2. The second day we sing of Stephen,

Who stoned was and rose up even

To God whom he saw stand in heaven,

And crowned was for his prowess. [bravery]

3. The third day belongeth to Saint John,

Who was Christ's darling, dearer none,

To whom he entrusted, when he should gone, [when he had to die]

His mother dear for her cleanness. [purity]

4. The fourth day of the children young,

Whom Herod put to death with wrong;

Of Christ they could not tell with tongue,

But with their blood bore him witness.

5. The fifth day belongeth to Saint Thomas,

Who, like a strong pillar of brass,

Held up the church, and slain he was,

Because he stood with righteousness.

6. The eighth day Jesu took his name,

Who saved mankind from sin and shame,

And circumcised was, for no blame,

But as example of meekness.

7. The twelfth day offered to him kings three,

Gold, myrrh, and incense, these gifts free,

For God, and man, and king was he,

Thus worshipped they his worthiness.

8. On the fortieth day came Mary mild,

Unto the temple with her child,

To show herself clean, who never was defiled,

And therewith endeth Christmas.

Read the rest of the commentary here.

And this year, Candlemas is on Sunday!

As a lover of carols, I'm much in favour of the medieval practice of keeping Christmas celebrations going all through the dark days of January, so today I thought I would post a carol which encourages us to keep singing throughout this season. It runs through not just the twelve days of Christmas but also the forty days of the Christmas season, all the way up to Candlemas, the Feast of the Purification, on February 2. It's a fifteenth-century carol (from Bodleian MS Eng. poet. e. I), and the unmodernised text can be found on this site , which also lists the various feasts mentioned: St Stephen on the 26th, St John on the 27th, the Holy Innocents on the 28th, St Thomas Becket on the 29th (check back soon for more carols about him!), the Circumcision of Christ on January 1st, Epiphany and Candlemas.

Make we mirth

For Christ's birth,

And sing we Yule til Candlemas.

1. The first day of Yule have we in mind,

How God was man born of our kind;

For he the bonds would unbind

Of all our sins and wickedness.

2. The second day we sing of Stephen,

Who stoned was and rose up even

To God whom he saw stand in heaven,

And crowned was for his prowess. [bravery]

3. The third day belongeth to Saint John,

Who was Christ's darling, dearer none,

To whom he entrusted, when he should gone, [when he had to die]

His mother dear for her cleanness. [purity]

4. The fourth day of the children young,

Whom Herod put to death with wrong;

Of Christ they could not tell with tongue,

But with their blood bore him witness.

5. The fifth day belongeth to Saint Thomas,

Who, like a strong pillar of brass,

Held up the church, and slain he was,

Because he stood with righteousness.

6. The eighth day Jesu took his name,

Who saved mankind from sin and shame,

And circumcised was, for no blame,

But as example of meekness.

7. The twelfth day offered to him kings three,

Gold, myrrh, and incense, these gifts free,

For God, and man, and king was he,

Thus worshipped they his worthiness.

8. On the fortieth day came Mary mild,

Unto the temple with her child,

To show herself clean, who never was defiled,

And therewith endeth Christmas.

Read the rest of the commentary here.

And this year, Candlemas is on Sunday!

Published on December 29, 2013 22:30

December 28, 2013

The Second Howard Martyr on the Block

Blessed William Howard, who was St. Philip Howard's grandson, was beheaded on December 29, 1680 on Tower Hill as a result of the Popish Plot; he had been tried in the House of Lords and found guilty. He protested his innocence throughout the trial and on the scaffold:Next he lift up his hands, standing up, and said. "I beseech Thee, God, not to avenge my innocent blood upon any man in the Whole kingdom ; no, not against those who by their perjuries have brought me here. For I profess before Almighty God that I never combined against the King's life, nor any body else, but whatever I did was only to procure liberty for the Romish religion. And, as for the Duke of York, I do here declare, upon my Salvation, I know of no design that he ever had against the King, but hath ever behaved himself, for ought I know, as a loving, loyal brother ought to do.So now, upon my Salvation, I have said true all that I have said. And I pray God to have mercy upon my soul." . . .After which he went round the scaffold and spake to the multitude thus, "I pray God, bless the King, and bless you all, especially the King's loyal subjects (such as I am myself) for I know you have a good and gracious King as ever reigned. God forgive me my sins, I forgive all the world, even those fellows that brought me here, and pray God to send them no worse punishment than to repent and tell the truth. And so, God bless you all."And some replyed, "God have mercy upon your soul." Then a minister applyed himself, and said, "Sir; you did disown the indulgences of the Romish Church."To which he answered, with a great passion." Sir ; what have you to do with my religion? Pray do not trouble me. However, I do say that the Church of Rome allows no indulgences for murder, lying, &c., and whatever I have said is true. What need you trouble yourself? "Min. "Have you received no absolution?"Answ. "I have received none at all. Sir, trouble not yourself, nor me."Min. "You said that you never saw those witnesses."Answ. "I never saw any of them but Dugdale, and that was at a time when I spoke to him about a footboy, or a foot match."Then his man took off his periwig and upper coat, and with a pair of sizers (sic) cut off the collar of his masters shirt, after which, W.S. lyes down in a white satin waistcoat, a quilted sky-coloured silk cap, with lace turn 'd up, &c.He gave his watch to a gentleman, crucifix to his page, his staff and paper to another.Having fitted his neck to the block, rise up upon his knees and prayed to himself, then takes the block and embraced it, then 'his servants cut off more of the linen, in all which time he sent up short prayers, that Christ would receive his spirit. Then lying down and praying upon the block, the sheriff Cornish askt' of the headsman, in kindness to W.S., if he had given him any sign. He answered "No." Whereupon W.S. rose up in a consternation and asked what they wanted. To which it was answered, "What sign will you give, Sir?"Answ. "No sign at all. Take your own time. God's will be done."Whereupon the executioner said, " I hope you forgive me?"He made answer, "I do." Then lying down again, two of his servants came with a piece of black silk to receive the head. Then the headsman took the Axe in 'his hand, and after some pause gave the blow, Which was cleverly done, save the cutting off a little skin, which was cut off immediately with a knife. Pope Pius XI beatified William Howard in 1929.

Published on December 28, 2013 22:30

David Starkey's "Music and Monarchy"

This Christmas, my husband gave me a copy of the DVD set of the BBC's series, "David Starkey's Music & Monarchy", a beautifully produced overview of musical history in England, considering the influence of the monarchy on mostly ceremonial church music. Starkey begins with Henry V, who even wrote music for parts of the Mass, and ends the series with the coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953. During the four episodes, choirs and ensembles perform great music by well known composers like Thomas Tallis, William Byrd, Orlando Gibbons, Henry Purcell, George Handel, Thomas Arne, Hubert Parry, Charles Villiers Stanford, Edward Elgar, and Ralph Vaughan Williams. Also, there are works by lesser known composers like Thomas Tomkins, William Lawes, Henry Lawes, Pelham Humphrey, William Croft, and Albert, Prince Consort of Queen Victoria. Eton College, King's College, Cambridge, Westminster Abbey, St. Paul's Cathedral, and Canterbury Cathedral are among the venues, while the Choirs of Eton, King's College, Canterbury Cathedral, Westminster Abbey, and St. Paul's Cathedral perform in situ. Fretwork, Alamire, the Academy of Ancient Music, The Parley of Instruments, The Band of the Life Guards, and several soloists also perform. The musical selections and the performance are uniformly excellent, and Starkey's narration and his interviews with performers, conductors, and music historians are enlightening. The story of English music and monarchy basically follows, from Henry VIII on, the outline of English Reformation history during the Tudor dynasty, with the repercussions of religious division during the Stuart Dynasty, the Interregnum, Restoration, Glorious Revolution, Protestant succession through the House of Hanover, the Victorian and Edwardian eras, and finally, the House of Windsor succeeding. In the latter part of the history, Starkey considers the impact of the Oxford Movement on English church music, but he really does not consider the impact of secularization on English church music. There were a couple of very great surprises: that Willliam and Mary dissolved the Chapel Royal and ended Henry Purcell's career as a royal composer of religious music--and that Thomas Arne wrote both "Rule, Britannia" and "God Save the King" in the midst of conflict between George II and his estranged son, Frederick the Prince of Wales (who was the father of King George III). Arne wrote "Rule, Britannia" for Frederick as part of a masque honoring King Alfred the Great and supporting the expansion of the British Navy, and then wrote "God Save the King" to support George II. To me, the most noticeable gap is how little he considers the crucial restoration of Tudor church music during the reign of Mary I--when Tallis and Byrd and others were able to write polyphony again. That gap also means that Starkey does not consider the influence of great Spanish composers like Victoria, de Monte and Guerrero on English polyphony, or the exile of Catholic composers like Peter Philips, John Bull, and others. Starkey would only have had to consult Harry Christophers and The Sixteen to explore that crucial period through their CD

The Flowering of Genius

. Instead, Starkey skips over that period, perhaps because it does not fit his rather Whiggish narrative of English history. That issue aside, the musical performances and the venues make this two-disc set a prized possession. As my husband commented, we could watch the first episode over and over again:

This Christmas, my husband gave me a copy of the DVD set of the BBC's series, "David Starkey's Music & Monarchy", a beautifully produced overview of musical history in England, considering the influence of the monarchy on mostly ceremonial church music. Starkey begins with Henry V, who even wrote music for parts of the Mass, and ends the series with the coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953. During the four episodes, choirs and ensembles perform great music by well known composers like Thomas Tallis, William Byrd, Orlando Gibbons, Henry Purcell, George Handel, Thomas Arne, Hubert Parry, Charles Villiers Stanford, Edward Elgar, and Ralph Vaughan Williams. Also, there are works by lesser known composers like Thomas Tomkins, William Lawes, Henry Lawes, Pelham Humphrey, William Croft, and Albert, Prince Consort of Queen Victoria. Eton College, King's College, Cambridge, Westminster Abbey, St. Paul's Cathedral, and Canterbury Cathedral are among the venues, while the Choirs of Eton, King's College, Canterbury Cathedral, Westminster Abbey, and St. Paul's Cathedral perform in situ. Fretwork, Alamire, the Academy of Ancient Music, The Parley of Instruments, The Band of the Life Guards, and several soloists also perform. The musical selections and the performance are uniformly excellent, and Starkey's narration and his interviews with performers, conductors, and music historians are enlightening. The story of English music and monarchy basically follows, from Henry VIII on, the outline of English Reformation history during the Tudor dynasty, with the repercussions of religious division during the Stuart Dynasty, the Interregnum, Restoration, Glorious Revolution, Protestant succession through the House of Hanover, the Victorian and Edwardian eras, and finally, the House of Windsor succeeding. In the latter part of the history, Starkey considers the impact of the Oxford Movement on English church music, but he really does not consider the impact of secularization on English church music. There were a couple of very great surprises: that Willliam and Mary dissolved the Chapel Royal and ended Henry Purcell's career as a royal composer of religious music--and that Thomas Arne wrote both "Rule, Britannia" and "God Save the King" in the midst of conflict between George II and his estranged son, Frederick the Prince of Wales (who was the father of King George III). Arne wrote "Rule, Britannia" for Frederick as part of a masque honoring King Alfred the Great and supporting the expansion of the British Navy, and then wrote "God Save the King" to support George II. To me, the most noticeable gap is how little he considers the crucial restoration of Tudor church music during the reign of Mary I--when Tallis and Byrd and others were able to write polyphony again. That gap also means that Starkey does not consider the influence of great Spanish composers like Victoria, de Monte and Guerrero on English polyphony, or the exile of Catholic composers like Peter Philips, John Bull, and others. Starkey would only have had to consult Harry Christophers and The Sixteen to explore that crucial period through their CD

The Flowering of Genius

. Instead, Starkey skips over that period, perhaps because it does not fit his rather Whiggish narrative of English history. That issue aside, the musical performances and the venues make this two-disc set a prized possession. As my husband commented, we could watch the first episode over and over again:

Published on December 28, 2013 22:30

December 27, 2013

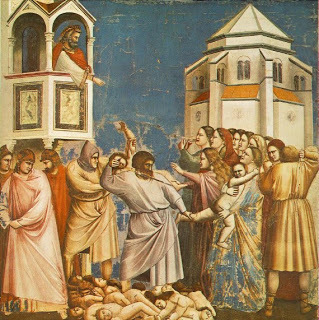

Feast of the Holy Innocents and the Coventry Carol

The Coventry Carol was part of a 16th century mystery play depicting the slaughter of the young boys in Bethlehem as described in St. Matthew's Gospel, chapter 2, verses 16-18:

The Coventry Carol was part of a 16th century mystery play depicting the slaughter of the young boys in Bethlehem as described in St. Matthew's Gospel, chapter 2, verses 16-18:Then Herod perceiving that he was deluded by the wise men, was exceeding angry; and sending killed all the men children that were in Bethlehem, and in all the borders thereof, from two years old and under, according to the time which he had diligently inquired of the wise men. Then was fulfilled that which was spoken by Jeremias the prophet, saying: A voice in Rama was heard, lamentation and great mourning; Rachel bewailing her children, and would not be comforted, because they are not. (Douai-Rheims translation).

Lully, lullay, Thou little tiny Child,By, by, lully, lullay.

O sisters too, how may we do,For to preserve this dayThis poor Youngling for Whom we singBy, by, lully, lullay?

Herod the king, in his raging,Charged he hath this dayHis men of might, in his own sight,All young children to slay.

That woe is me, poor Child for Thee!

And ever morn and dayFor Thy parting neither say nor sing,By, by, lully, lullay.

Lully, lullay, Thou little tiny Child,By, by, lully, lullay.

Because Henry VIII proscribed these mystery plays, and the last authentic manuscript was burned in the 19th century, the words we have now are based on transcriptions. Here is a performance from Westminster Cathedral.

There is another famous hymn for this Feast, very ancient, by Prudentius, Salvete flores Martyrum.

John Mason Neale collaborated on a translation:

1. All hail! ye infant Martyr-flowers,

Cut off in life’s first dawning hours:

As rosebuds, snapt in tempest strife,

When Herod sought your Saviour’s life.

2. You, tender flock of lambs, we sing,

First victims slain for Christ your King:

Beneath the Altar’s heav’nly ray

With Martyr-palms and crowns ye play.

3. For their redemption glory be,

O Jesu, Virgin-born, to thee,

With Father, and with Holy Ghost,

For ever from the Martyr-host. Amen.

Published on December 27, 2013 22:30

December 26, 2013

A Survivor of the English Monastic Tradition: Brother Petroc

A dear friend gave me, as a birthday present, Brother Petroc's Return, a historical fantasy novel by S.M.C., Sister Mary Catherine Anderson, first published in 1937 by Little, Brown and Company. It was also published as an Image Books paperback:

The current edition is from the Dominican Nuns of Summit (New Jersey). The convent's website is down until January 2, 2014: www.nunsopsummit.org:

S.M.C. was born in Cornwall (an Anglican clergyman's daughter) and became a Catholic with her family while still a young girl, according to the biography at the back of the paperback. She wrote several historical novels set in Cornwall, especially about the Prayer Book Rebellion. I think the Dominicans in Summit intend to publish more of her works, but only the coming of the new year will confirm that information, since they have shut down their website during the Octave of Christmas (amazon.com does offer another work, The Chronicles of Thomas Frith, O.P.). I would be pleased to read S.M.C.'s historical novels.

She is a sophisticated and brilliant historical novelist based on my reading this book, at least. Using the "Hypothesis" as she calls it of a miracle, she demonstrates some great changes in religious life from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries.

Brother Petroc dies on August 14, 1549 in the midst of the Prayer Book Rebellion after learning that his two brothers have died fighting against Edward VI's imposition of the Book of Common Prayer. The Benedictine monastery in which he professed was saved from the Dissolution of the Monasteries because it was so hidden and unknown, perched at the top of a cliff on the Atlantic coast. He is buried in haste since the monks must flee from Edward's troops.

Four hundred years later, Benedictines have purchased and restored the ruined monastery and then the Abbot, Prior and Subprior discover Brother Petroc, not just incorrupt, but alive! S.M.C. carefully details the long recovery of the man who was buried 400 years before, and along the way, as this review from The Tablet in 1937 notes, reveals what really separates him from his Benedictine brothers, in spite of the fact they are living according to the same Rule:

The process of adjustment, as Brother Petroc again takes his place in his community, gives the author her opportunity of showing the great changes which have taken place in spiritual method during the last four hundred years. Before the Reformation, in the ages of Faith, the Christian, and especially the contemplative, thought more directly in terms of God's Will and less directly in terms of his own soul ; today, in Petroc's words, "People of this generation seem to place themselves in the centre of their universe, and to look at life from that standpoint." The pre-Reformation attitude is extrovert, the post-Reformation introvert. . . .

And the kindly but unimaginative Dom Maurus, who unwittingly did so much harm by bringing Petroc too suddenly into contact with a flood of new impressions, expresses the point well : "St. Benedict and the older Masters of the Spiritual Life had started with God and viewed the soul from that standpoint. Self-knowledge came through a comparison of their own souls with God, at Whom they were looking, and the desire that arose therefrom of rendering themselves as little unworthy of Him as possible. . . . Now the later exponents started with the soul itself and cleansed and disciplined it systematically, in order to make it fit for the entrance of God."

When I say that S.M.C. is a "sophisticated and brilliant historical novelist" I mean that she conveys this rather abstract and even academic fact through character development and plot. It is worked into the story as Brother Petroc amazes the Novices with whom he studies with his calmness, understanding, and holiness. Among those who think him merely simple and slow, the Prior comes to appreciate his wisdom and even his gifts as a poet, as he finds one of Brother Petroc's poems by chance:

Of winter-thorn and white-thorn

Fain would I sing,

Of Marye Flower of Heaven,

Of Chryste our King.

It fell about the Yule-tide,

When winds are starke and wilde,

That of a mayden stainless

Was born a littyl Child.

It fell about the Spring-time,

When flowers are freshe to see,

That Chryste, the Sonne of Marye,

Did die uponne a tree . . . (pp. 147-148)

Not wishing to spoil the plot, I won't offer any more synopsis. Reading Brother Petroc's Return allows the reader, like the Novices, to be "in contact with a survival of the ages of faith, the great ages of the world", and like them will find it "so unusual and interesting" (p. 73). Highly recommended. As The Tablet reviewer said in 1937:

Brother Petroc's Return is a book of quite exceptional merit, for it shows not only a profound and deep comprehension of the ways of the Christian spirit, but is in itself a book of great beauty, a joy to read, and a profit to study.

The current edition is from the Dominican Nuns of Summit (New Jersey). The convent's website is down until January 2, 2014: www.nunsopsummit.org:

S.M.C. was born in Cornwall (an Anglican clergyman's daughter) and became a Catholic with her family while still a young girl, according to the biography at the back of the paperback. She wrote several historical novels set in Cornwall, especially about the Prayer Book Rebellion. I think the Dominicans in Summit intend to publish more of her works, but only the coming of the new year will confirm that information, since they have shut down their website during the Octave of Christmas (amazon.com does offer another work, The Chronicles of Thomas Frith, O.P.). I would be pleased to read S.M.C.'s historical novels.

She is a sophisticated and brilliant historical novelist based on my reading this book, at least. Using the "Hypothesis" as she calls it of a miracle, she demonstrates some great changes in religious life from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries.

Brother Petroc dies on August 14, 1549 in the midst of the Prayer Book Rebellion after learning that his two brothers have died fighting against Edward VI's imposition of the Book of Common Prayer. The Benedictine monastery in which he professed was saved from the Dissolution of the Monasteries because it was so hidden and unknown, perched at the top of a cliff on the Atlantic coast. He is buried in haste since the monks must flee from Edward's troops.

Four hundred years later, Benedictines have purchased and restored the ruined monastery and then the Abbot, Prior and Subprior discover Brother Petroc, not just incorrupt, but alive! S.M.C. carefully details the long recovery of the man who was buried 400 years before, and along the way, as this review from The Tablet in 1937 notes, reveals what really separates him from his Benedictine brothers, in spite of the fact they are living according to the same Rule:

The process of adjustment, as Brother Petroc again takes his place in his community, gives the author her opportunity of showing the great changes which have taken place in spiritual method during the last four hundred years. Before the Reformation, in the ages of Faith, the Christian, and especially the contemplative, thought more directly in terms of God's Will and less directly in terms of his own soul ; today, in Petroc's words, "People of this generation seem to place themselves in the centre of their universe, and to look at life from that standpoint." The pre-Reformation attitude is extrovert, the post-Reformation introvert. . . .

And the kindly but unimaginative Dom Maurus, who unwittingly did so much harm by bringing Petroc too suddenly into contact with a flood of new impressions, expresses the point well : "St. Benedict and the older Masters of the Spiritual Life had started with God and viewed the soul from that standpoint. Self-knowledge came through a comparison of their own souls with God, at Whom they were looking, and the desire that arose therefrom of rendering themselves as little unworthy of Him as possible. . . . Now the later exponents started with the soul itself and cleansed and disciplined it systematically, in order to make it fit for the entrance of God."

When I say that S.M.C. is a "sophisticated and brilliant historical novelist" I mean that she conveys this rather abstract and even academic fact through character development and plot. It is worked into the story as Brother Petroc amazes the Novices with whom he studies with his calmness, understanding, and holiness. Among those who think him merely simple and slow, the Prior comes to appreciate his wisdom and even his gifts as a poet, as he finds one of Brother Petroc's poems by chance:

Of winter-thorn and white-thorn

Fain would I sing,

Of Marye Flower of Heaven,

Of Chryste our King.

It fell about the Yule-tide,

When winds are starke and wilde,

That of a mayden stainless

Was born a littyl Child.

It fell about the Spring-time,

When flowers are freshe to see,

That Chryste, the Sonne of Marye,

Did die uponne a tree . . . (pp. 147-148)

Not wishing to spoil the plot, I won't offer any more synopsis. Reading Brother Petroc's Return allows the reader, like the Novices, to be "in contact with a survival of the ages of faith, the great ages of the world", and like them will find it "so unusual and interesting" (p. 73). Highly recommended. As The Tablet reviewer said in 1937:

Brother Petroc's Return is a book of quite exceptional merit, for it shows not only a profound and deep comprehension of the ways of the Christian spirit, but is in itself a book of great beauty, a joy to read, and a profit to study.

Published on December 26, 2013 22:30

December 25, 2013

The Feast of Saint Stephen and "Good King Wenceslaus"

John Mason Neale composed this carol for St. Stephen's Day, Good King Wenceslas. According to this site:

Today, Dec. 26, is the Feast of St. Stephen, the first martyr of the Christian church.

But while this is an interesting and doubtless profound commemoration in the calendar of the liturgical churches, the day is better known by the reference in the Christmas carol “Good King Wenceslas,” written by the Rev. John Mason Neale and published in 1853. It is a very odd sort of song in a number of ways. The tune appears in popular culture even more often than the words do and is played in the background to almost every film set at Christmas time that I have ever seen.

In the first place, it is not a traditional carol, a song sung by generations in honor of Christmas, although Neale published it in a book titled “Carols for Christmas.” It was entirely composed in Victorian England and was set to the tune “Tempus adest floridum,” which is an Easter song that dates to the 13th century with entirely different lyrics. The Latin title means “The time is near for flowering.” The subject of the song, King Wenceslas, who immortalizes St. Stephen’s Day, was not even a king, nor was he English, and he actually died a rather nasty death in Bohemia, in what is now the Czech Republic. It is a song immortalizing a medieval Catholic saint, written by an Anglican clergyman in Protestant England. . . .

Good King Wenceslas looked outOn the feast of StephenWhen the snow lay round aboutDeep and crisp and even.Brightly shone the moon that nightThough the frost was cruelWhen a poor man came in sightGath'ring winter fuel.

"Hither, page, and stand by meIf thou know'st it, tellingYonder peasant, who is he?Where and what his dwelling?""Sire, he lives a good league henceUnderneath the mountainRight against the forest fenceBy Saint Agnes' fountain."

"Bring me flesh and bring me wineBring me pine logs hitherThou and I will see him dineWhen we bear him thither."Page and monarch forth they wentForth they went togetherThrough the rude wind's wild lamentAnd the bitter weather.

"Sire, the night is darker nowAnd the wind blows strongerFails my heart, I know not how,I can go no longer.""Mark my footsteps, my good pageTread thou in them boldlyThou shalt find the winter's rageFreeze thy blood less coldly."

In his master's steps he trodWhere the snow lay dintedHeat was in the very sodWhich the Saint had printed.Therefore, Christian men, be sureWealth or rank possessingYe who now will bless the poorShall yourselves find blessing.

Published on December 25, 2013 23:30

The Feast of St. Stephen and the English Catholic Martyrs

St. Stephen is course the proto-martyr and his imitation of Christ was so exact that he spoke the same words of forgiveness for his executioners. Because the Venerable English College in Rome was like "a nursery for martyrs", the custom arose of one of their seminarians preaching on the feast of St. Stephen, according to this blog:

St. Stephen is course the proto-martyr and his imitation of Christ was so exact that he spoke the same words of forgiveness for his executioners. Because the Venerable English College in Rome was like "a nursery for martyrs", the custom arose of one of their seminarians preaching on the feast of St. Stephen, according to this blog:The English College gained a reputation as a nursery of martyrs. Owing to the number of its martyred students, the custom arose of a student of the college preaching, on the theme of martyrdom, before the Pope on St Stephen’s Day.

On St Stephen’s Day, 1581, Blessed John Cornelius, who had entered the English College, Rome, in April 1580, preached before Pope Gregory XIII. (Pope Gregory XIII is best remembered for producing, with the help of Christopher Clavius S J, the Gregorian calendar.) In his sermon, John called the College the “Pontifical Seminary of Martyrs”. Thirteen years later, on 4th July 1594, John Cornelius was martyred at Dorchester, Oxfordshire. He was beatified by Pope Pius XI in 1929.

On St Stephen’s Day 1642, the recently ordained Welshman, David Lewis, preached before Pope Urban VIII in the Lateran Basilica. He preached in Latin and his sermon, entitled “Corona Christi pro spinis gemmea” was on the Martyrdom of St Stephen, the first Christian Martyr. David Lewis was martyred at Usk on 27th August 1679. He was canonised in 1970 by Pope Paul VI.

Here is the College's Litany of Martyrs:

St Ralph Sherwin, 1581

St Luke Kirby, 1582

Blessed John Shert, 1582

Blessed William Lacey, 1582

Blessed Thomas Cottam, 1582

Blessed William Hart, 1583

Blessed George Haydock, 1584

Blessed Thomas Hemerford, 1584

Blessed John Munden, 1584

Blessed John Lowe, 1586

Blessed Robert Morton, 1588

Blessed Richard Leigh, 1588

Blessed Edward James, 1588

Blessed Christopher Buxton, 1588

Blessed Christopher Bales, 1590

Blessed Edmund Duke, 1590

St Polydore Plasden, 1591

St Eustace White, 1591

Blessed Joseph Lambton, 1592

Blessed Thomas Pormort, 1592

Blessed John Cornelius S J, 1594

Blessed John Ingram, 1594

Blessed Edward Thwing, 1594

St Robert Southwell S J, 1595

St Henry Walpole S J, 1595

Blessed Robert Middleton, 1601

Blessed Robert Watkinson, 1602

Venerable Thomas Tichborne, 1602

Blessed Edward Oldcorne, 1606

St John Almond , 1612

Blessed Richard Smith, 1612

Blessed John Thules, 1616

Blessed John Lockwood, 1642

Venerable Edward Morgan, 1642

Venerable Brian Tansfield S J, 1643

St Henry Morse S J, 1645

Blessed John Woodcock O F M, 1646

Venerable Edward Mico S J, 1678

Blessed Antony Turner S J, 1679

St John Wall O F M, 1679

St David Lewis S J, 1679

More on the College and the Age of Martyrs here.

Published on December 25, 2013 22:30

Barton Swaim on Jay Parini's "Jesus: The Human Face of God"

I don't know if Barton Swaim would like this comparison or not, but I thought of G.K. Chesterton when I read his review of the novelist and critic's book about Jesus (from

The Wall Street Journal

):

One of the wonderful qualities of the New Testament's four Gospels is that they force you either to embrace or reject them. You can study the Gospels as "literature" if you like, but their logic subverts any attempt to treat them as you would treat other literary texts. "Hamlet" may reach dizzying heights of sublimity and repay a lifetime of study, but it doesn't ask for radical changes in your thought and behavior and has no power to compel them.

Three centuries of critical New Testament scholarship haven't changed this. The Quest for the Historical Jesus, an attempt to interpret the canonical Gospel texts without reference to supernatural explanations, began with German scholarship in the 18th century, gradually took hold of universities and divinity schools elsewhere in Europe and America during the 19th century, and exploded in popularity during the latter half of the 20th century. Hundreds, probably thousands, of books purporting to explain the identity and intentions of Jesus of Nazareth have been published since the "quest" began in the 1770s; and yet, despite scholars' confident pronouncements about how Jesus went from political revolutionary or peaceable philosopher to Eternal Son of God, the Gospels' claims about him are neither more nor less plausible than they were before. . . .

The point here isn't that the Gospels must be true. It is that the Gospels offer no easy way to explain away their content. They therefore demand one of two choices. Either they relay things that Jesus actually said and did, in which case he really is who the New Testament claims he is, or they are haphazard collections of deliberately fabricated stories about a man who may have said some extraordinary things in first-century Judea but who has no more claim on your attention than Socrates. C.S. Lewis, among others, made a similar argument about Jesus' self-descriptions: "Either this man was, and is, the Son of God, or else a madman or something worse." And while that argument has often been dismissed on the grounds that it assumes all the Gospels' quotations of Jesus to be authentic, its logic applies with equal or greater force to the four Gospel texts themselves. Either they are true or they are collections of precious fables. There is no third option. They cannot be somehow factually false but metaphorically true—the human mind rightly rejects that kind of reasoning as highfalutin cant. This point is powerfully made by Jay Parini's "Jesus," although Mr. Parini didn't intend to make that point at all. Read the rest here.

One of the wonderful qualities of the New Testament's four Gospels is that they force you either to embrace or reject them. You can study the Gospels as "literature" if you like, but their logic subverts any attempt to treat them as you would treat other literary texts. "Hamlet" may reach dizzying heights of sublimity and repay a lifetime of study, but it doesn't ask for radical changes in your thought and behavior and has no power to compel them.

Three centuries of critical New Testament scholarship haven't changed this. The Quest for the Historical Jesus, an attempt to interpret the canonical Gospel texts without reference to supernatural explanations, began with German scholarship in the 18th century, gradually took hold of universities and divinity schools elsewhere in Europe and America during the 19th century, and exploded in popularity during the latter half of the 20th century. Hundreds, probably thousands, of books purporting to explain the identity and intentions of Jesus of Nazareth have been published since the "quest" began in the 1770s; and yet, despite scholars' confident pronouncements about how Jesus went from political revolutionary or peaceable philosopher to Eternal Son of God, the Gospels' claims about him are neither more nor less plausible than they were before. . . .

The point here isn't that the Gospels must be true. It is that the Gospels offer no easy way to explain away their content. They therefore demand one of two choices. Either they relay things that Jesus actually said and did, in which case he really is who the New Testament claims he is, or they are haphazard collections of deliberately fabricated stories about a man who may have said some extraordinary things in first-century Judea but who has no more claim on your attention than Socrates. C.S. Lewis, among others, made a similar argument about Jesus' self-descriptions: "Either this man was, and is, the Son of God, or else a madman or something worse." And while that argument has often been dismissed on the grounds that it assumes all the Gospels' quotations of Jesus to be authentic, its logic applies with equal or greater force to the four Gospel texts themselves. Either they are true or they are collections of precious fables. There is no third option. They cannot be somehow factually false but metaphorically true—the human mind rightly rejects that kind of reasoning as highfalutin cant. This point is powerfully made by Jay Parini's "Jesus," although Mr. Parini didn't intend to make that point at all. Read the rest here.

Published on December 25, 2013 22:30

December 24, 2013

From the Cambridge Lessons and Carols Yesterday

After the Annunciation reading from the Gospel according to St. Luke, the Choir of King's College Cambridge sang this happy hymn:

1. Angelus ad virginem

Subintrans in conclave.

Virginis formidinum

Demulcens inquit "Ave."

Ave regina virginum,

Coeliteraeque dominum

Concipies

Et paries

Intacta,

Salutem hominum.

Tu porta coeli facta

Medella criminum.

2. Quomodo conciperem,

quae virum non cognovi?

Qualiter infringerem,

quae firma mente vovi?

'Spiritus sancti gratia

Perficiet haec omnia;

Ne timaes,

sed gaudeas,

secura,

quod castimonia

Manebit in te pura

Dei potentia.'

3. Ad haec virgo nobilis

Respondens inquit ei;

Ancilla sum humilis

Omnipotentis Dei.

Tibi coelesti nuntio,

Tanta secreti conscio,

Consentiens

Et cupiens

Videre

factum quod audio,

Parata sum parere

Dei consilio.

4. Angelus disparuit

Etstatim puellaris

Uterus intumuit

Vi partus salutaris.

Qui, circumdatus utero

Novem mensium numero,

Hinc Exiit

Et iniit

Conflictum,

Affigens humero

Crucem, qua dedit ictum

Hosti mortifero.

5. Eia Mater Domini,

Quae pacem reddidisti

Angelis et homini,

Cum Christum genuisti;

Tuem exora filium

Ut se nobis propitium

Exhibeat,

Et deleat

Peccata;

Praestans auxilium

Vita frui beta

Post hoc exsilium.

This site gives some background:

The cheerfully sounding song about the Annunciation, Angelus ad Virginem or, in its English form, Gabriel, From Heven King Was To The Maide Sende, was a popular Medieval carol that is still popular today. The text of this song is a poetic version of Hail Mary, full of dramatic tension and theological profundity.

It appeared in an Dublin Troper (c. 1361, a music book for use at Mass) and was found in a Sequentiale (Vellum manuscript, 13th or 14th century), possibly connected with the Church of Addle, Yorks. This lyric also appears in the works of John Audelay, in a group of four Marian poems. Audelay may have been a priest; he spent the last years of his life at Haghmond, an Augustinian abbey, and wrote for the monks there.

It is said to have originally consisted of 27 stanzas, with each following stanza beginning with the consecutive letter of the alphabet.

Chaucer mentions it in his Miller's Tale, where poor scholar Nicholas sang it in Latin to the accompaniment of his psaltery:

And over all there lay a psaltery

Whereon he made an evening's melody,

Playing so sweetly that the chamber rang;

And Angelus ad virginem he sang;

And after that he warbled the King's Note:

Often in good voice was his merry throat.

Both the Oxford Book of Carols and, especially, the New Oxford Book of Carols contain musical settings and additional historical notes.

In addition to the translations provided, there is the translation by John Macleod Campbell Crum, 1932, which is reproduced as #547 in Hymn Ancient & Modern, Revised.

The site also notes:

The carol was probably Franciscan in original and brought to Britain by French friars in the 13th century. There is a 14th Irish source for the latin version and, from the same period, a middle-English version which begins:

1. Angelus ad virginem

Subintrans in conclave.

Virginis formidinum

Demulcens inquit "Ave."

Ave regina virginum,

Coeliteraeque dominum

Concipies

Et paries

Intacta,

Salutem hominum.

Tu porta coeli facta

Medella criminum.

2. Quomodo conciperem,

quae virum non cognovi?

Qualiter infringerem,

quae firma mente vovi?

'Spiritus sancti gratia

Perficiet haec omnia;

Ne timaes,

sed gaudeas,

secura,

quod castimonia

Manebit in te pura

Dei potentia.'

3. Ad haec virgo nobilis

Respondens inquit ei;

Ancilla sum humilis

Omnipotentis Dei.

Tibi coelesti nuntio,

Tanta secreti conscio,

Consentiens

Et cupiens

Videre

factum quod audio,

Parata sum parere

Dei consilio.

4. Angelus disparuit

Etstatim puellaris

Uterus intumuit

Vi partus salutaris.

Qui, circumdatus utero

Novem mensium numero,

Hinc Exiit

Et iniit

Conflictum,

Affigens humero

Crucem, qua dedit ictum

Hosti mortifero.

5. Eia Mater Domini,

Quae pacem reddidisti

Angelis et homini,

Cum Christum genuisti;

Tuem exora filium

Ut se nobis propitium

Exhibeat,

Et deleat

Peccata;

Praestans auxilium

Vita frui beta

Post hoc exsilium.

This site gives some background:

The cheerfully sounding song about the Annunciation, Angelus ad Virginem or, in its English form, Gabriel, From Heven King Was To The Maide Sende, was a popular Medieval carol that is still popular today. The text of this song is a poetic version of Hail Mary, full of dramatic tension and theological profundity.

It appeared in an Dublin Troper (c. 1361, a music book for use at Mass) and was found in a Sequentiale (Vellum manuscript, 13th or 14th century), possibly connected with the Church of Addle, Yorks. This lyric also appears in the works of John Audelay, in a group of four Marian poems. Audelay may have been a priest; he spent the last years of his life at Haghmond, an Augustinian abbey, and wrote for the monks there.

It is said to have originally consisted of 27 stanzas, with each following stanza beginning with the consecutive letter of the alphabet.

Chaucer mentions it in his Miller's Tale, where poor scholar Nicholas sang it in Latin to the accompaniment of his psaltery:

And over all there lay a psaltery

Whereon he made an evening's melody,

Playing so sweetly that the chamber rang;

And Angelus ad virginem he sang;

And after that he warbled the King's Note:

Often in good voice was his merry throat.

Both the Oxford Book of Carols and, especially, the New Oxford Book of Carols contain musical settings and additional historical notes.

In addition to the translations provided, there is the translation by John Macleod Campbell Crum, 1932, which is reproduced as #547 in Hymn Ancient & Modern, Revised.

The site also notes:

The carol was probably Franciscan in original and brought to Britain by French friars in the 13th century. There is a 14th Irish source for the latin version and, from the same period, a middle-English version which begins:

Gabriel fram Heven-King / Sent to the Maide sweete,

Broute hir blisful tiding / And fair he gan hir greete:

'Heil be thu, ful of grace aright! / For Godes Son, this Heven Light,

For mannes love / Will man bicome /And take / Fles of thee,

Maide bright, / Manken free for to make / Of sen and devles might.'

Published on December 24, 2013 22:30