Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 248

January 13, 2014

Blessed Margaret Pole, On the Block

On the English Historical Fiction Authors blog, Judith Arnopp writes about Blessed Margaret Pole, imagining her last moments:It is May 27th 1541 and an old woman wakes in her prison at the Tower of London. She stretches her limbs and blinks at the early morning light filtering through the high window, and groans as she remembers that today is the day she is to die.

Reluctant to shed the warmth of the furred nightgown sent to her by Queen Katherine just a few weeks ago, she shivers while her woman rolls up her hose, ties her fur lined petticoat and secures her new worsted kirtle. She prays for a while, the familiar rhythm of the words whispering from chapped lips until a footstep sounds. The rattle of a chain, bolts shooting back, the creak of the door.

Reluctant to shed the warmth of the furred nightgown sent to her by Queen Katherine just a few weeks ago, she shivers while her woman rolls up her hose, ties her fur lined petticoat and secures her new worsted kirtle. She prays for a while, the familiar rhythm of the words whispering from chapped lips until a footstep sounds. The rattle of a chain, bolts shooting back, the creak of the door.

‘It is time, Madam.’

Outside, the world is calm. The sky is white. Fresh green leaves bright against the sombre walls. A flurry of ravens fly up as the small party passes beneath their roost. There is no scaffold for Margaret, just a block and a terrified executioner about to take his first victim. . . .

As Judith Arnopp notes, Hazel Pierce’s biography Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury 1473-1541: Loyalty, Lineage and Leadership, which is now out in paperback, is still the only major biography of this great lady.

Reluctant to shed the warmth of the furred nightgown sent to her by Queen Katherine just a few weeks ago, she shivers while her woman rolls up her hose, ties her fur lined petticoat and secures her new worsted kirtle. She prays for a while, the familiar rhythm of the words whispering from chapped lips until a footstep sounds. The rattle of a chain, bolts shooting back, the creak of the door.

Reluctant to shed the warmth of the furred nightgown sent to her by Queen Katherine just a few weeks ago, she shivers while her woman rolls up her hose, ties her fur lined petticoat and secures her new worsted kirtle. She prays for a while, the familiar rhythm of the words whispering from chapped lips until a footstep sounds. The rattle of a chain, bolts shooting back, the creak of the door. ‘It is time, Madam.’

Outside, the world is calm. The sky is white. Fresh green leaves bright against the sombre walls. A flurry of ravens fly up as the small party passes beneath their roost. There is no scaffold for Margaret, just a block and a terrified executioner about to take his first victim. . . .

As Judith Arnopp notes, Hazel Pierce’s biography Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury 1473-1541: Loyalty, Lineage and Leadership, which is now out in paperback, is still the only major biography of this great lady.

Published on January 13, 2014 22:30

January 12, 2014

"Recusancy and Regicide" from Penn History Review

Carolyn Vinnicombe, at that time a junior at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote this analysis of the Jesuit mission in Reformation England, published in the Spring 2012 issue of the Penn History Review:

Carolyn Vinnicombe, at that time a junior at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote this analysis of the Jesuit mission in Reformation England, published in the Spring 2012 issue of the Penn History Review:Introduction: In pursuing their goals of reviving the religious zeal of the English Catholic community by converting them to religious opposition in the later sixteenth and earlier seventeenth centuries, the drivers of the Jesuit mission in England, under the guidance of the Jesuit Robert Persons, failed. They did so not because Catholic doctrine lacked appeal in protestant Elizabethan England, but because their conversion strategy was wholly unsuited to the political realities of the times. Instead, the aggregate effects of the Church’s clerical infighting over the issues of conformity and disputation as a conversion device, failure to understand the practical needs of the average Catholic, and Person’s ill-fated political plotting polarized the English against the Jesuits and created a religious and political environment so toxic that it cannibalized the mission’s own conversion efforts. Though the Jesuits saw later success with the publication of their non-polemic spiritual texts, they never succeeded in gaining back the ground they lost as a result of their catastrophic early strategy.

The issue of conformity to the Elizabethan Settlement of 1569 presented a dilemma without an absolute solution for the English Catholic community. When Pope Pius V’s Regans in Excelsis of 1570, excommunicated the queen, and prompted her regime to mandate attendance at protestant services, it left English Catholics floundering to find traction on the plane of religious devotion. Could they still call themselves Catholics if they yielded to the state and attended protestant services, but maintained Catholicism in their hearts, or were only those who defied the state and refused to attend services worthy of the “Catholic” label and, indeed, salvation? This was a question for which neither the laity nor the Church had a clear answer.

Read the rest of the article here.

Published on January 12, 2014 22:30

January 9, 2014

The Play's The Thing--Then and Now

Times Higher Education reviews The Drama of Reform: Theology and Theatricality, 1461-1553 by Tamara Atkin (reviewed by Helen Smith):

Whereas the drama of the English Renaissance is celebrated, frequently performed and a staple of school and university curricula, the plays of the English Reformation (or rather the multiple, incremental and partial reformations of the four British nations) are neglected with almost equal enthusiasm. In part, this can be explained by their unfortunate chronological position, wedged awkwardly, in stylistic as well as temporal terms, between the medieval and early modern. In part, it comes down to our lack of knowledge about where and why many of these plays were performed, despite some diligent detective work. Ultimately, though, the lack of widespread zeal for the plays may be a result of their own passionate espousal of the religious arguments that transformed personal and national identities in the middle years of the 16th century.

The Drama of Reform follows the lead of recent scholarship in embracing the complexities of reformist drama, from the polemical plays of John Bale to the likes of Jacke Jugeler, which claims to be only a “merie” reworking of Plautus, but is centrally concerned with debates concerning the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Tamara Atkin’s book concentrates on four plays, dedicating a chapter to each and identifying telling, and often precise, links between their contents and the proponents of reform. What we get rather less of, however, is a sense of how representative these plays are and how they fit alongside more traditional, orthodox drama.

And The Independent reviews the Royal Shakespeare Company theatrical adaptation of the first two novels about Thomas Cromwell written by Hilary Mantel--which have their own "theology":

One hesitates to use the phrase “a marriage made in heaven” in the vicinity of Henry VIII but that would be a fair way of describing this brilliant union between the RSC and Hilary Mantel.

The Company has just unveiled its epic six-hour stage version of her two prize-winning novels which view the English Reformation and the deadly intrigues of the Tudor court from the vantage point of Thomas Cromwell, the Putney blacksmith's son who rose to be royal fixer-in-chief.

The marathon press performance began at 1pm and, after a dinner break, concluded at 10pm. But such is the dramatic skill of the adaptation by Mike Poulton (with whom Mantel has worked closely) and the unflagging power and fascination of Jeremy Herrin's fleet, incisively acted production that, if the final instalment of the trilogy had been completed and turned into a play, I would gladly have stayed up all night.

There are inevitable losses in the transition from page to stage - from the atmospheric richness of Mantel's prose to the flashbacks to formative experiences in Cromwell's past, such as his witnessing, in boyhood, the pitiless auto-da-fe of a female heretic.

But Ben Miles is superlative at conveying the inner complexities of the man – the shrewd watchfulness, the sense of banked-down grief, the little flashes of sardonic humour. David Starkey once described Cromwell as “Alastair Campbell with an axe” but in these plays we get a thoroughly three-dimensional figure.

Beyond the pages of a book, literary or theological, the representation of personal drama on stage, comic or tragic, has an attractiveness that reaches out to another audience. Someone who would never read John Bales's theological arguments in the 16th century would learn from his plays. In the same way, Mantel's fiction translated to the stage becomes even an even more powerful representation of her characterizations of Cromwell and Thomas More, for example. That is certainly why the Society of Jesus developed a dramatic tradition in their schools, to teach their students about the art of persuasion (rhetoric) and to inculcate virtue. More on the Jesuits and drama here.

Published on January 09, 2014 22:30

January 8, 2014

Constantine in Wichita, Kansas

No--not the Keanu Reeves's movie; I mean the Emperor Constantine!

No--not the Keanu Reeves's movie; I mean the Emperor Constantine!Some major speakers are going to be in Wichita next weekend to discuss "Constantine, Christendom, and Christian Renewal", according to The Wichita Eagle :

“Constantine, Christendom and Christian Renewal” is the theme of the fourth annual Eighth Day Symposium, Jan. 16 to Jan. 18 at St. George Orthodox Cathedral in Wichita.

The symposium is sponsored by Eighth Day Institute, a nonprofit effort to renew culture through faith and learning. Speakers from four traditions will headline the event: Peter Leithart, president of Trinity House and adjunct senior fellow at New St. Andrews College; Vigen Guorian, professor of religious studies at the University of Virginia; Alan Kreider, professor of church history and mission at Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary; and Benjamin Wiker, faculty associate at the Veritas Center for Ethics and Public Life and visiting associate professor of theology at Franciscan University.

The cost of the symposium is $40 a day or $75 for two days; lunch is included. A banquet on Jan. 17 at 7 p.m. is $35. Register online at http://www.eighthdayinstitute.com/ , by calling 316-573-8413, or in person at Eighth Day Books, 2838 E. Douglas. Registration will also be available at the door; the cathedral is at 7515 E. 13th St.

You can find out more about the speakers--really major academic presenters and authors--here.

Read more here: http://www.kansas.com/2014/01/07/3216...

Published on January 08, 2014 22:30

January 7, 2014

Happy Birthday, John Carroll!

Russell Shaw writes about the life and career of John Carroll in the December 23, 2013 issue of Our Sunday Visitor newsweekly:

A member of a wealthy and respected Catholic family, with excellent contacts among America’s political and social elite, Archbishop Carroll proved notably adept at building bridges with the non-Catholic world in a career spanning more than three decades. “A gentleman of learning and abilities,” John Adams, who was to be second president of the United States, said of the young priest in 1776, the year of American independence.Along with persuading Protestants that Catholics also had a place in America, John Carroll was to tackle the mammoth task of building the infrastructure of the Church from scratch. And in this, too, he proved remarkably successful.He was born Jan. 8, 1735, at his parents’ plantation in southern Maryland, the fourth of seven children. His older brother, Daniel, was to be one of only five men who signed both the Articles of Confederation and the U.S. Constitution. His cousin and lifelong friend, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, was the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence and the first U.S. senator from Maryland.Read the rest here.

A member of a wealthy and respected Catholic family, with excellent contacts among America’s political and social elite, Archbishop Carroll proved notably adept at building bridges with the non-Catholic world in a career spanning more than three decades. “A gentleman of learning and abilities,” John Adams, who was to be second president of the United States, said of the young priest in 1776, the year of American independence.Along with persuading Protestants that Catholics also had a place in America, John Carroll was to tackle the mammoth task of building the infrastructure of the Church from scratch. And in this, too, he proved remarkably successful.He was born Jan. 8, 1735, at his parents’ plantation in southern Maryland, the fourth of seven children. His older brother, Daniel, was to be one of only five men who signed both the Articles of Confederation and the U.S. Constitution. His cousin and lifelong friend, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, was the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence and the first U.S. senator from Maryland.Read the rest here.

Published on January 07, 2014 22:30

January 5, 2014

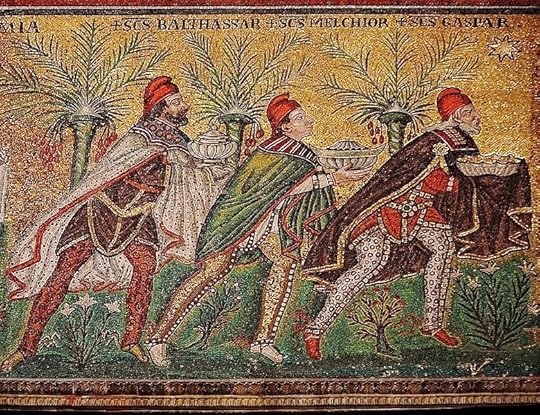

Today is Epiphany: The Twelfth Day!

Although many Catholics celebrated the Feast of the Epiphany yesterday at Sunday Mass, today is the twelfth day--the traditional date of the Epiphany of Our Lord. Epiphany means "manifestation" and the day really remembers three great manifestations of Jesus: to the Magi; to John the Baptist in the Jordan; and at the Marriage Feast Cana, where He turned water into wine. A Clerk of Oxford features this fifteenth century English hymn that celebrates the coming of the Magi, narrating the story of their contact with Herod and even his massacre of the Holy Innocents:

Reges de Saba venient,

Aurum, tus myrram offerent.

Alleluia.

1. Now is the Twelfth Day ycome,

The Father and Son together are nome, 1

The Holy Ghost, as they were wone, 2

In fere.

God send us a good New Year!

2. I will you sing with all my might,

Of a Child so fair in sight,

A maiden him bore this endernight,

So still;

As it was his will. . . .A Clerk of Oxford not only explains the carol's origin, but offers an illustrated version of its narration:This is a lively Epiphany carol, full of drama and dialogue. It comes from a fifteenth-century manuscript of carols, BL Sloane 2593, and I've modernised the spelling from this text ; the refrain means "Kings shall come from Sheba, offering gold, frankincense and myrrh" (a quotation from a Christmas hymn). One of my favourite things about it is the moustache-twirling villain Herod in verse 16: "Herod laughed and said, "A-ha!" But really the whole thing is wonderful.

Let's take a lot at the same story as it appears, illustrated in exhaustive detail, in the splendid manuscript BL Yates Thompson 13 . This fourteenth-century English Book of Hours has exquisite illustrations on a whole range of subjects but also depicts the entire narrative of the Magi and King Herod, in a series of pictures running across the bottom of ff. 90-95v. So this is the Visit of the Magi: Medieval Graphic Novel Version.Merry Christmas! Happy Epiphany!Image Source: wikipedia commons.

Published on January 05, 2014 22:30

January 4, 2014

Anne Line and Shakespeare: Tragedy and Christ

On my review stack is this volume, Anne Line: Shakespeare's Tragic Muse by Martin Dodwell. Mr. Dodwell follows up on the efforts of John Finnis and Patrick Martin, and others, who see a connection between Shakespearean works and the story of Anne Line. I've only read a couple of chapters, so I'll withhold my opinion about Dodwell's work.

Surely, however, Anne Line's story is tragic--and amazing--not because of any flaw (the English major's knowledge that every tragic hero has to have a "tragic flaw"), but because of her virtue of conscientious faithfulness. She is rejected by her family because she becomes a Catholic; she loses her husband to exile because they are Catholic and he attends Catholic Mass; she is arrested and condemned to hanging because she aids Catholic priests, and finally she is buried without ceremony or consecration--cast off like a suicide. All of her actions are indeed in conflict with her country's laws and culture, which condemn her Catholicism as treason against the state (and against the monarch). Like Antigone burying her father and brother against Creon's decree, Anne Line upholds her Catholic faith against Elizabeth I's Protestant laws.

There is, of course, a crucial distinction for a Christian tragic heroine: the Resurrection. Now death itself is not tragic in the same sense--it is not just Anne Line's death that appeases the Elizabethan recusancy and penal laws as the ancient Attic tragedy required. With the Resurrection of Jesus Christ, as David B. Hart argued in a First Things article almost 10 years ago (in 2003!), the whole concept of tragedy has changed. When He was crucified, condemned by Pontius Pilate, He overturned that idea of tragedy, because He rose from the dead, defeating Roman execution. Hart explains the Attic view of tragedy and expiation:

As it happens, the word “tragic” is especially apt here. A sacrificial mythos need not always express itself in slaughter, after all. Attic tragedy, for instance, began as a sacrificial rite. It was performed during the festival of Dionysus, which was a fertility festival, of course, but only because it was also an apotropaic celebration of delirium and death: the Dionysia was a sacred negotiation with the wild, antinomian cruelty of the god whose violent orgiastic cult had once, so it was believed, gravely imperiled the city; and the hope that prompted the feast was that, if this devastating force could be contained within bright Apollonian forms and propitiated through a ritual carnival of controlled disorder, the polis could survive for another year, its precarious peace intact. . . .

The religious vision from which Attic tragedy emerged was one of the human community as a kind of besieged citadel preserving itself through the tribute it paid to the powers that both threatened and enlivened it. I can think of no better example of this than that of Antigone, in which the tragic crisis is the result of an insoluble moral conflict between familial piety (a sacred obligation) and the civil duties of kingship (a holy office): Antigone, as a woman, is bound to the chthonian gods (gods of the dead, so of family and household), and Creon, as king, is bound to Apollo (god of the city), and so both are adhering to sacred obligations. The conflict between them, then, far from involving a tension between the profane and the holy, is a conflict within the divine itself, whose only possible resolution is the death — the sacrifice — of the protagonist. Other examples, however, are legion. Necessity’s cruel intransigence rules the gods no less than us; tragedy’s great power is simply to reconcile us to this truth, to what must be, and to the violences of the city that keep at bay the greater violence of cosmic or social disorder. . . .

And then he explains how Jesus Christ changed all that, beginning with the dialogue between Jesus and Pilate in the Gospel of St. John--in which the representative of the Roman Empire is stymied by the regalness of a Jewish peasant--and then considering Peter's tears:

This slave is the Father’s eternal Word, whom God has vindicated, and so ten thousand immemorial certainties are unveiled as lies: the first become last, the mighty are put down from their seats and the lowly exalted, the hungry are filled with good things while the rich are sent empty away. Nietzsche was quite right to be appalled. Almost as striking, for me, is the tale of Peter, at the cock’s crow, going apart to weep. Nowhere in the literature of pagan antiquity, I assure you, had the tears of a rustic been regarded as worthy of anything but ridicule; to treat them with reverence, as meaningful expressions of real human sorrow, would have seemed grotesque from the perspective of all the classical canons of good taste. Those wretchedly subversive tears, and the dangerous philistinism of a narrator so incorrigibly vulgar as to treat them with anything but contempt, were most definitely signs of a slave revolt in morality, if not quite the one against which Nietzsche inveighed — a revolt, moreover, that all the ancient powers proved impotent to resist.

In a narrow sense, then, one might say that the chief offense of the Gospels is their defiance of the insights of tragedy — and not only because Christ does not fit the model of the well-born tragic hero. More important is the incontestable truth that, in the Gospels, the destruction of the protagonist emphatically does not restore or affirm the order of city or cosmos. Were the Gospels to end with Christ’s sepulture, in good tragic style, it would exculpate all parties, including Pilate and the Sanhedrin, whose judgments would be shown to have been fated by the exigencies of the crisis and the burdens of their offices; the story would then reconcile us to the tragic necessity of all such judgments. But instead comes Easter, which rudely interrupts all the minatory and sententious moralisms of the tragic chorus, just as they are about to be uttered to full effect, and which cavalierly violates the central tenet of sound economics: rather than trading the sacrificial victim for some supernatural benefit, and so the particular for the universal, Easter restores the slain hero in his particularity again, as the only truth the Gospels have to offer. This is more than a dramatic peripety. The empty tomb overturns all the “responsible” and “necessary” verdicts of Christ’s judges, and so grants them neither legitimacy nor pardon.

(Among the surprised judges must be the Sanhedrin, with Caiaphas and Annas--and Caiaphas' proposal of offering Jesus as a sacrifice for the good of the community being overturned by reports of His resurrection and appearances.)

The Elizabethan authorities knew that their prosecution of Catholics was creating martyrs--Elizabeth's spymaster Walsingham warned against the power of the martyrs after their executions to create sympathy and inspire followers--so the whole notion of executing Anne Line and the other priests who suffered that same day at Tyburn as a way of proclaiming the power and justice of the state had changed. Not only the Greeks and Romans had to respond to this revolution in life and death in tragedy--but even the Elizabethan/Anglican polis had to recognize that its sacrificial victims lived on beyond Tyburn and an unmarked, unconsecrated grave.

Published on January 04, 2014 22:30

January 1, 2014

Elizabeth Barton: More Questions than Answers?

Beth von Staats posts on Elizabeth Barton, the Holy Maid of Kent for the English Historical Fiction Authors blog, and she uses an icon with the words "Blessed Elizabeth Barton" among her illustrations. Elizabeth Barton has not been beatified by the Catholic Church--she and her confessors were included in the second "cause" for the Reformation martyrs held at Westminster from September, 1888 to August, 1889, but she and her five companions (John Dering, O.S.B., Edward Bocking, O.S.B., Hugh Rich, O.S.F., Richard Masters, priest, Henry Gold, priest) have not moved forward in the process of canonization. Since they were not included in the first cause submitted to Rome, they are among the prætermissi (the passed over). The author and I corresponded on the post to clarify the point.

Nevertheless, von Staats' post is interesting, as she narrates the story of Barton's rise and fall:

Born in obscurity, Elizabeth Barton's life as a celebrated English woman began with what at the time was considered by all Roman Catholics an awe-inspiring trance and God sent miracle. While working as a servant in a Kent household, Barton became seriously ill -- some today might surmise epilepsy, while others might assume delirium or psychosis. Incredibly, she began to speak in rhyming prophecies.

After sharing her vision of a nearby chapel, Elizabeth Barton was taken there and lain before a statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary. As astounding as this sounds, the woman remained there in a trance for a week. Upon awakening, Elizabeth Barton began prophesying again, predicting the death of a child living in her household, and as detailed by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer in a letter to Archdeacon Hawkins, "speaking of many high and godly things, telling also wondrously, by the power of the Holy Ghost as it was thought, things done and said in other places, whereas neither she was herself, nor yet heard no report thereof."

Soon afterward, she was questioned by a special commission established by then Archbishop William Warham. They determined her trances, visions and prophecies genuine, and a "star was born". At least a thousand people took to the road, processing to the little chapel, and like Jim Morrison's grave, the Ford Theater, the town of Bethlehem, and the shrine of St. Thomas Beckett, it became a place of pilgrimage.

Elizabeth Barton's illustrious or infamous career, depending on one's point of you, then began in earnest. Admitted to St. Sepulcre's nunnery in Canterbury, she professed her vows, and her trances, prophecies and clairvoyance continued and increased unabated.

Sister Elizabeth’s messages of warning and predictions of the future were reported to the world outside her cloistered community by a group of priests close to the convent, and her fame and celebrity rose to the highest zenith of Tudor society. Legitimized as filled with the Holy Spirit by the likes of Archbishop William Warham and Bishop John Fisher, who both met with the "Holy Maid of Kent", Sister Elizabeth Barton became exceptionally acclaimed throughout the realm, respected for her piety and marveled for her Godly giftedness.

One of her cited sources is the old Catholic Encyclopedia entry on Elizabeth Barton, which notes that Protestants and Catholics have taken sides on how to interpret her story:

Protestant authors allege that these confessions alone are conclusive of her imposture, but Catholic writers, though they have felt free to hold divergent opinions about the nun, have pointed out the suggestive fact that all that is known as to these confessions emanates from Cromwell or his agents; that all available documents are on his side; that the confession issued as hers is on the face of it not her own composition; that she and her companions were never brought to trial, but were condemned and executed unheard; that there is contemporary evidence that the alleged confession was even then believed to be a forgery. For these reasons, the matter cannot be considered as settled, and unfortunately, the difficulty of arriving at any satisfactory and final decision now seems insuperable.

And "difficulty of arriving at any satisfactory and final decision" about Barton's guilt or innocence, pretense or authenticity as a mystic--and her confessors' roles in her activities--probably means that her cause will not move forward. Barton, Bocking, Dering, et al, may have suffered and died because of their opposition to Henry VIII's religious revolution, but if they were using religious prophecy to manipulate and deceive, they won't be declared blessed or canonized by the Church.

Nevertheless, von Staats' post is interesting, as she narrates the story of Barton's rise and fall:

Born in obscurity, Elizabeth Barton's life as a celebrated English woman began with what at the time was considered by all Roman Catholics an awe-inspiring trance and God sent miracle. While working as a servant in a Kent household, Barton became seriously ill -- some today might surmise epilepsy, while others might assume delirium or psychosis. Incredibly, she began to speak in rhyming prophecies.

After sharing her vision of a nearby chapel, Elizabeth Barton was taken there and lain before a statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary. As astounding as this sounds, the woman remained there in a trance for a week. Upon awakening, Elizabeth Barton began prophesying again, predicting the death of a child living in her household, and as detailed by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer in a letter to Archdeacon Hawkins, "speaking of many high and godly things, telling also wondrously, by the power of the Holy Ghost as it was thought, things done and said in other places, whereas neither she was herself, nor yet heard no report thereof."

Soon afterward, she was questioned by a special commission established by then Archbishop William Warham. They determined her trances, visions and prophecies genuine, and a "star was born". At least a thousand people took to the road, processing to the little chapel, and like Jim Morrison's grave, the Ford Theater, the town of Bethlehem, and the shrine of St. Thomas Beckett, it became a place of pilgrimage.

Elizabeth Barton's illustrious or infamous career, depending on one's point of you, then began in earnest. Admitted to St. Sepulcre's nunnery in Canterbury, she professed her vows, and her trances, prophecies and clairvoyance continued and increased unabated.

Sister Elizabeth’s messages of warning and predictions of the future were reported to the world outside her cloistered community by a group of priests close to the convent, and her fame and celebrity rose to the highest zenith of Tudor society. Legitimized as filled with the Holy Spirit by the likes of Archbishop William Warham and Bishop John Fisher, who both met with the "Holy Maid of Kent", Sister Elizabeth Barton became exceptionally acclaimed throughout the realm, respected for her piety and marveled for her Godly giftedness.

One of her cited sources is the old Catholic Encyclopedia entry on Elizabeth Barton, which notes that Protestants and Catholics have taken sides on how to interpret her story:

Protestant authors allege that these confessions alone are conclusive of her imposture, but Catholic writers, though they have felt free to hold divergent opinions about the nun, have pointed out the suggestive fact that all that is known as to these confessions emanates from Cromwell or his agents; that all available documents are on his side; that the confession issued as hers is on the face of it not her own composition; that she and her companions were never brought to trial, but were condemned and executed unheard; that there is contemporary evidence that the alleged confession was even then believed to be a forgery. For these reasons, the matter cannot be considered as settled, and unfortunately, the difficulty of arriving at any satisfactory and final decision now seems insuperable.

And "difficulty of arriving at any satisfactory and final decision" about Barton's guilt or innocence, pretense or authenticity as a mystic--and her confessors' roles in her activities--probably means that her cause will not move forward. Barton, Bocking, Dering, et al, may have suffered and died because of their opposition to Henry VIII's religious revolution, but if they were using religious prophecy to manipulate and deceive, they won't be declared blessed or canonized by the Church.

Published on January 01, 2014 22:30

December 31, 2013

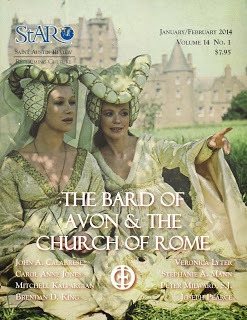

January/February 2014 Articles

In the reverse type on the cover of the January/February 2014 issue of the

St. Austin Review

, you might discern my name:

Then if you access the Table of Contents for the issue, you'll see my article on Pope Benedict's English Catholic Legacy listed "Inter Alia". StAR is a print review with limited on-line access, but I have submitted some texts to supplement the article on the StAR blog. In a way, there's a connection between that StAR article and my article in the January/February 2014 issue of OSV's The Catholic Answer Magazine:

Then if you access the Table of Contents for the issue, you'll see my article on Pope Benedict's English Catholic Legacy listed "Inter Alia". StAR is a print review with limited on-line access, but I have submitted some texts to supplement the article on the StAR blog. In a way, there's a connection between that StAR article and my article in the January/February 2014 issue of OSV's The Catholic Answer Magazine:

"How Can We Hear the "Voice of God"? Blessed John Henry Newman and conscience" is illustrated with a picture from the 2010 beatification of John Henry Newman. OSV recently updated its website and now the articles I've written for TCA are available on-line! Happy New Year!

"How Can We Hear the "Voice of God"? Blessed John Henry Newman and conscience" is illustrated with a picture from the 2010 beatification of John Henry Newman. OSV recently updated its website and now the articles I've written for TCA are available on-line! Happy New Year!

Then if you access the Table of Contents for the issue, you'll see my article on Pope Benedict's English Catholic Legacy listed "Inter Alia". StAR is a print review with limited on-line access, but I have submitted some texts to supplement the article on the StAR blog. In a way, there's a connection between that StAR article and my article in the January/February 2014 issue of OSV's The Catholic Answer Magazine:

Then if you access the Table of Contents for the issue, you'll see my article on Pope Benedict's English Catholic Legacy listed "Inter Alia". StAR is a print review with limited on-line access, but I have submitted some texts to supplement the article on the StAR blog. In a way, there's a connection between that StAR article and my article in the January/February 2014 issue of OSV's The Catholic Answer Magazine:

"How Can We Hear the "Voice of God"? Blessed John Henry Newman and conscience" is illustrated with a picture from the 2010 beatification of John Henry Newman. OSV recently updated its website and now the articles I've written for TCA are available on-line! Happy New Year!

"How Can We Hear the "Voice of God"? Blessed John Henry Newman and conscience" is illustrated with a picture from the 2010 beatification of John Henry Newman. OSV recently updated its website and now the articles I've written for TCA are available on-line! Happy New Year!

Published on December 31, 2013 22:30

Farewell to 2013; Hail to 2014!

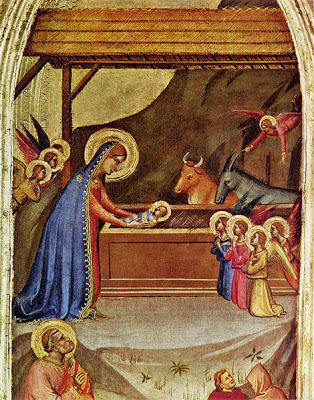

John Mason Neale included this translation of the medieval hymn (Anonymous; Germany; 12th century),

In hoc anni circulo

in his 1853 Carols for Christmas-tide:

John Mason Neale included this translation of the medieval hymn (Anonymous; Germany; 12th century),

In hoc anni circulo

in his 1853 Carols for Christmas-tide:In the ending of the year

Life and light to man appear;

And the Holy Babe is here,

De Virgine;

And the Holy Babe is here,

De Virgine Mariâ.

What in ancient days was slain

This day calls to life again;

God is coming, God shall reign,

De Virgine;

God is coming, God shall reign,

De Virgine Mariâ.

From the desert grew the corn,

Sprang the lily from the thorn,

When the Infant King was born

De Virgine;

When the Infant King was born

De Virgine Mariâ.

On the straw He lays His head,

Hath a manger for His bed,

Thirsts and hungers and is fed

De Virgine;

Thirsts and hungers and is fed

De Virgine Mariâ.

Angel hosts His praises sing,

Three Wise men their off'rings bring,

Ox and ass adore the King,

Cum Virgine;

Ox and ass adore the King,

Cum Virgine Mariâ.

Wherefore let us all to-day

Banish sorrow far away,

Singing and exulting aye,

Cum Virgine;

Singing and exulting aye,

Cum Virgine Mariâ.

As 2013 draws to a close, thank you for your attention to and comments on this blog!

Image source.

Published on December 31, 2013 18:00