Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 250

December 23, 2013

From G.K. Chesterton's "The Everlasting Man"

Part II, Chapter One, "The God in the Cave":

Chesterton demonstrates the glorious beauty of Our Mother Mary and her Child: if we ignore Mary when we try to understand Who Jesus Christ is ("God from God, Light from Light, True God from True God", who "came down from heaven, and by the Holy Spirit was incarnate of the Virgin Mary, and became man") we will end up taking "Christ out of Christmas or Christmas out of Christ":

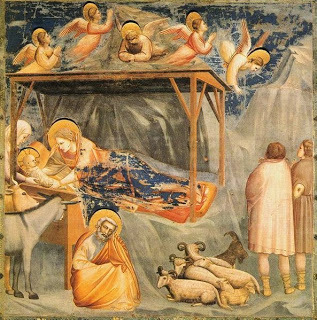

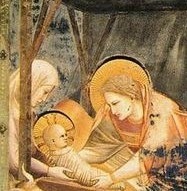

Bethlehem is emphatically a place where extremes meet. Here begins, it is needless to say, another mighty influence for the humanization of Christendom. If the world wanted what is called a non-controversial aspect of Christianity, it would probably select Christmas. Yet it is obviously bound up with what is supposed to be a controversial aspect (I could never at any stage of my opinions imagine why); the respect paid to the Blessed Virgin. When I was a boy a more Puritan generation objected to a statue upon my parish church representing the Virgin and Child. After much controversy, they compromised by taking away the Child. One would think that this was even more corrupted with Mariolatry, unless the mother was counted less dangerous when deprived of a sort of weapon. But the practical difficulty is also a parable. You cannot chip away the statue of a mother from all round that of a newborn child. You cannot suspend the new-born child in mid-air; indeed you cannot really have a statue of a newborn child at all. Similarly, you cannot suspend the idea of a newborn child in the void or think of him without thinking of his mother. You cannot visit the child without visiting the mother, you cannot in common human life approach the child except through the mother. If we are to think of Christ in this aspect at all, the other idea follows I as it is followed in history. We must either leave Christ out of Christmas, or Christmas out of Christ, or we must admit, if only as we admit it in an old picture, that those holy heads are too near together for the haloes not to mingle and cross.

(I think the Giotto portrayal of the Blessed Virgin Mary and baby Jesus, with their heads so close together and their eyes so clearly meeting, represents the haloes mingling and crossing very well.)

Chesterton examines the roles of the shepherds (who find their Shepherd), the Three Kings of Orient (who find Someone greater than their philosophy), and Herod the King (who fears a Baby born in a manger and slaughters the Innocents), and then looks at our role today, as we find "something more human than humanity" in the story and reality of Christmas--God With Us.

This is the trinity of truths symbolised here by the three types in the old Christmas story; the shepherds and the kings and that other king who warred upon the children. It is simply not true to say that other religions and philosophies are in this respect its rivals. It is not true to say that any one of them combines these characters; it is not true to say that any one of them pretends to combine them. Buddhism may profess to be equally mystical; it does not even profess to be equally military. Islam may profess to be equally military; it does not even profess to be equally metaphysical and subtle. Confucianism may profess to satisfy the need of the philosophers for order and reason; it does not even profess to satisfy the need of the mystics for miracle and sacrament and the consecration of concrete things. There are many evidences of this presence of a spirit at once universal and unique. One will serve here which is the symbol of the subject of this chapter; that no other story, no pagan legend or philosophical anecdote or historical event, does in fact affect any of us with that peculiar and even poignant impression produced on us by the word Bethlehem. No other birth of a god or childhood of a sage seems to us to be Christmas or anything like Christmas. It is either too cold or too frivolous, or too formal and classical, or too simple and savage, or too occult and complicated. Not one of us, whatever his opinions, would ever go to such a scene with the sense that he was going home. He might admire it because it was poetical, or because it was philosophical, or any number of other things in separation; but not because it was itself. The truth is that there is a quite peculiar and individual character about the hold of this story on human nature; it is not in its psychological substance at all like a mere legend or the life of a great man. It does not exactly in the ordinary sense turn our minds to greatness; to those extensions and exaggerations of humanity which are turned into gods and heroes, even by the healthiest sort of hero-worship. It does not exactly work outwards, adventurously, to the wonders to be found at the ends of the earth. It is rather something that surprises us from behind, from the hidden and personal part of our being; like that which can some times take us off our guard in the pathos of small objects or the blind pieties of the poor. It is rather as if a man had found an inner room in the very heart of his own house, which he had never suspected; and seen a light from within. It is as if he found something at the back of his own heart that betrayed him into good. It is not made of what the world would call strong materials; or rather it is made of materials whose strength is in that winged levity with which they brush us and pass. It is all that is in us but a brief tenderness that is there made eternal; all that means no more than a momentary softening that is in some strange fashion become a strengthening and a repose; it is the broken speech and the lost word that are made positive and suspended unbroken; as the strange kings fade into a far country and the mountains resound no more with the feet of the shepherds; and only the night and the cavern lie in fold upon fold over something more human than humanity.

Published on December 23, 2013 22:30

December 21, 2013

The Commissioned Carol for King's College, Cambridge

On Christmas Eve, the great Choir of King's College, Cambridge will present its annual Lessons and Carols. Since 1982, the Choir has commissioned a new Christmas carol for the service: this year, Thea Musgrave wrote the music for a Willliam Blake poem:

This year's commissioned carol for A Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols has been composed by Thea Musgrave. It is a setting of the William Blake poem 'Hear the voice of the Bard' (1794).

The composer said: "It was with the greatest pleasure that I accepted a commission to write a carol for the famous choir of King's College, Cambridge, and their conductor Stephen Cleobury.

"After much consideration I chose one of the poems from the Songs of Experience by William Blake.

"The poem speaks of how the 'Bard's Voice' calls out to the 'lapséd soul' and for the 'Holy Word' to renew the 'fallen light'. It also calls for the earth to return after a long night; for the dawn to come and so for the sun to reappear."

Musgrave has won numerous awards for her large and varied body of work and received a CBE in 2002.

The poem she selected:

HEAR the voice of the Bard,

Who present, past, and future, sees;

Whose ears have heard

The Holy Word

That walk’d among the ancient trees;

Calling the lapsèd soul,And weeping in the evening dew;

That might control

The starry pole,

And fallen, fallen light renew!

‘O Earth, O Earth, return!Arise from out the dewy grass!

Night is worn,

And the morn

Rises from the slumbrous mass.

‘Turn away no more;Why wilt thou turn away?

The starry floor,

The watery shore,

Is given thee till the break of day.’

In keeping with my fascination with Dickens' A Christmas Carol, I think I should note that Thea Musgrave wrote an operatic adaptation, with optional children's chorus!

More about the Lessons and Carols from the College website. I appreciate the clarity of the instructions for the queue for possible admittance to the service:

If you would like to attend the service, please join the queue at the main entrance to the College. Normally anyone joining the queue before 9am will get in, but we cannot guarantee this. The queue is admitted into the Chapel at 1.30pm and the service begins at 3pm. The service ends at around 4.30pm. Please note that the service is not suitable for young children. There is no charge for attending, as with any service in the Chapel. A retiring collection is taken after the service for the maintenance of the Chapel.

Arrangements for those who want to queue are as follows:

The only entrance to the College will be via the main gate on King's Parade. All other gates will be locked.Members of the public in the queue will be admitted to the College grounds via the front gate from 7.30am.The Porters will monitor the number of people joining the queue and, once there are as many people in the queue as there are seats available, members of the public will be advised that it is unlikely that they will be able to attend the service.Bags and packages cannot be taken into the Chapel and must be deposited with the Porters in the designated area.Once inside the College grounds toilet facilities are available and refreshments can be purchased from the College coffee shop.Then the program has more detailed instructions about silence and decorum for those attending, since the service is broadcast live on the BBC:

In order not to spoil the service for other members of the congregation and radio listeners, please do not talk or cough unless it is absolutely necessary. Please turn off chiming digital watches and mobile phones. . . . And, whatever you do, don't talk during the organ prelude!

This year's commissioned carol for A Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols has been composed by Thea Musgrave. It is a setting of the William Blake poem 'Hear the voice of the Bard' (1794).

The composer said: "It was with the greatest pleasure that I accepted a commission to write a carol for the famous choir of King's College, Cambridge, and their conductor Stephen Cleobury.

"After much consideration I chose one of the poems from the Songs of Experience by William Blake.

"The poem speaks of how the 'Bard's Voice' calls out to the 'lapséd soul' and for the 'Holy Word' to renew the 'fallen light'. It also calls for the earth to return after a long night; for the dawn to come and so for the sun to reappear."

Musgrave has won numerous awards for her large and varied body of work and received a CBE in 2002.

The poem she selected:

HEAR the voice of the Bard,

Who present, past, and future, sees;

Whose ears have heard

The Holy Word

That walk’d among the ancient trees;

Calling the lapsèd soul,And weeping in the evening dew;

That might control

The starry pole,

And fallen, fallen light renew!

‘O Earth, O Earth, return!Arise from out the dewy grass!

Night is worn,

And the morn

Rises from the slumbrous mass.

‘Turn away no more;Why wilt thou turn away?

The starry floor,

The watery shore,

Is given thee till the break of day.’

In keeping with my fascination with Dickens' A Christmas Carol, I think I should note that Thea Musgrave wrote an operatic adaptation, with optional children's chorus!

More about the Lessons and Carols from the College website. I appreciate the clarity of the instructions for the queue for possible admittance to the service:

If you would like to attend the service, please join the queue at the main entrance to the College. Normally anyone joining the queue before 9am will get in, but we cannot guarantee this. The queue is admitted into the Chapel at 1.30pm and the service begins at 3pm. The service ends at around 4.30pm. Please note that the service is not suitable for young children. There is no charge for attending, as with any service in the Chapel. A retiring collection is taken after the service for the maintenance of the Chapel.

Arrangements for those who want to queue are as follows:

The only entrance to the College will be via the main gate on King's Parade. All other gates will be locked.Members of the public in the queue will be admitted to the College grounds via the front gate from 7.30am.The Porters will monitor the number of people joining the queue and, once there are as many people in the queue as there are seats available, members of the public will be advised that it is unlikely that they will be able to attend the service.Bags and packages cannot be taken into the Chapel and must be deposited with the Porters in the designated area.Once inside the College grounds toilet facilities are available and refreshments can be purchased from the College coffee shop.Then the program has more detailed instructions about silence and decorum for those attending, since the service is broadcast live on the BBC:

In order not to spoil the service for other members of the congregation and radio listeners, please do not talk or cough unless it is absolutely necessary. Please turn off chiming digital watches and mobile phones. . . . And, whatever you do, don't talk during the organ prelude!

Published on December 21, 2013 22:30

Speaking of Persecution: In the WSJ

Philip Jenkins reviews John L. Allen, Jr.'s book, The Global War on Christians for The Wall Street Journal: On Oct. 31, 2010, a dozen Islamist gunmen stormed the Catholic cathedral of Our Lady of Salvation, in Baghdad. Striking during a service, they butchered some 60 priests and worshipers, notionally in revenge for insults to Islam. Ghastly as that crime might be in its own right, atrocities of this kind are quite commonplace around the world. Mobs sack churches in Egypt, Nigerian suicide bombers target worshiping congregations, and Eritrea has its hellish concentration camps for Christians. "Christians today," writes John L. Allen Jr. , "indisputably are the most persecuted religious body on the planet." So widespread and systematic are the attacks, he explains, that they amount to a global war, which he proclaims "the transcendent human rights concern" in the modern world. Mr. Allen is by no means the first writer to address this phenomenon, but he may be the best qualified. He has through the years established himself as among the best-informed commentators on the Vatican and the state of the Roman Catholic Church, and hearing so many contacts recount stories of persecution and discrimination has naturally sensitized him to anti-Christian campaigns, and by no means only those directed against Catholics. . . . In cruder hands, "The Global War on Christians" could easily have turned into an anti-Islamic rant. Yet while Mr. Allen devotes full attention to the evil deeds of Islamists in Iraq, Nigeria and elsewhere, he also refutes the myth "that it's all about Islam." Over the past century, some of the very worst anti-Christian persecutors have been fanatically anti-religious, commonly driven by Marxist-Leninist ideology. Islam, evidently, has nothing to do with the atrocities of the North Korean regime, which has made its country perhaps the worst single place in the world to be a Christian: The government has killed thousands of Christians and imprisoned tens of thousands more, in hideous conditions. Nor does Mr. Allen succumb to the common temptation to concentrate so much on Muslim misdeeds that we ignore savage and persistent persecutions by Hindu fanatics—the pogroms, the forced conversions, the mob attacks against churches, often committed with the tacit acquiescence of police and local governments. Read the rest here. Coming from Philip Jenkins of Baylor University, that's a trust- and attention worthy review.

Philip Jenkins reviews John L. Allen, Jr.'s book, The Global War on Christians for The Wall Street Journal: On Oct. 31, 2010, a dozen Islamist gunmen stormed the Catholic cathedral of Our Lady of Salvation, in Baghdad. Striking during a service, they butchered some 60 priests and worshipers, notionally in revenge for insults to Islam. Ghastly as that crime might be in its own right, atrocities of this kind are quite commonplace around the world. Mobs sack churches in Egypt, Nigerian suicide bombers target worshiping congregations, and Eritrea has its hellish concentration camps for Christians. "Christians today," writes John L. Allen Jr. , "indisputably are the most persecuted religious body on the planet." So widespread and systematic are the attacks, he explains, that they amount to a global war, which he proclaims "the transcendent human rights concern" in the modern world. Mr. Allen is by no means the first writer to address this phenomenon, but he may be the best qualified. He has through the years established himself as among the best-informed commentators on the Vatican and the state of the Roman Catholic Church, and hearing so many contacts recount stories of persecution and discrimination has naturally sensitized him to anti-Christian campaigns, and by no means only those directed against Catholics. . . . In cruder hands, "The Global War on Christians" could easily have turned into an anti-Islamic rant. Yet while Mr. Allen devotes full attention to the evil deeds of Islamists in Iraq, Nigeria and elsewhere, he also refutes the myth "that it's all about Islam." Over the past century, some of the very worst anti-Christian persecutors have been fanatically anti-religious, commonly driven by Marxist-Leninist ideology. Islam, evidently, has nothing to do with the atrocities of the North Korean regime, which has made its country perhaps the worst single place in the world to be a Christian: The government has killed thousands of Christians and imprisoned tens of thousands more, in hideous conditions. Nor does Mr. Allen succumb to the common temptation to concentrate so much on Muslim misdeeds that we ignore savage and persistent persecutions by Hindu fanatics—the pogroms, the forced conversions, the mob attacks against churches, often committed with the tacit acquiescence of police and local governments. Read the rest here. Coming from Philip Jenkins of Baylor University, that's a trust- and attention worthy review.

Philip Jenkins reviews John L. Allen, Jr.'s book, The Global War on Christians for The Wall Street Journal: On Oct. 31, 2010, a dozen Islamist gunmen stormed the Catholic cathedral of Our Lady of Salvation, in Baghdad. Striking during a service, they butchered some 60 priests and worshipers, notionally in revenge for insults to Islam. Ghastly as that crime might be in its own right, atrocities of this kind are quite commonplace around the world. Mobs sack churches in Egypt, Nigerian suicide bombers target worshiping congregations, and Eritrea has its hellish concentration camps for Christians. "Christians today," writes John L. Allen Jr. , "indisputably are the most persecuted religious body on the planet." So widespread and systematic are the attacks, he explains, that they amount to a global war, which he proclaims "the transcendent human rights concern" in the modern world. Mr. Allen is by no means the first writer to address this phenomenon, but he may be the best qualified. He has through the years established himself as among the best-informed commentators on the Vatican and the state of the Roman Catholic Church, and hearing so many contacts recount stories of persecution and discrimination has naturally sensitized him to anti-Christian campaigns, and by no means only those directed against Catholics. . . . In cruder hands, "The Global War on Christians" could easily have turned into an anti-Islamic rant. Yet while Mr. Allen devotes full attention to the evil deeds of Islamists in Iraq, Nigeria and elsewhere, he also refutes the myth "that it's all about Islam." Over the past century, some of the very worst anti-Christian persecutors have been fanatically anti-religious, commonly driven by Marxist-Leninist ideology. Islam, evidently, has nothing to do with the atrocities of the North Korean regime, which has made its country perhaps the worst single place in the world to be a Christian: The government has killed thousands of Christians and imprisoned tens of thousands more, in hideous conditions. Nor does Mr. Allen succumb to the common temptation to concentrate so much on Muslim misdeeds that we ignore savage and persistent persecutions by Hindu fanatics—the pogroms, the forced conversions, the mob attacks against churches, often committed with the tacit acquiescence of police and local governments. Read the rest here. Coming from Philip Jenkins of Baylor University, that's a trust- and attention worthy review.

Philip Jenkins reviews John L. Allen, Jr.'s book, The Global War on Christians for The Wall Street Journal: On Oct. 31, 2010, a dozen Islamist gunmen stormed the Catholic cathedral of Our Lady of Salvation, in Baghdad. Striking during a service, they butchered some 60 priests and worshipers, notionally in revenge for insults to Islam. Ghastly as that crime might be in its own right, atrocities of this kind are quite commonplace around the world. Mobs sack churches in Egypt, Nigerian suicide bombers target worshiping congregations, and Eritrea has its hellish concentration camps for Christians. "Christians today," writes John L. Allen Jr. , "indisputably are the most persecuted religious body on the planet." So widespread and systematic are the attacks, he explains, that they amount to a global war, which he proclaims "the transcendent human rights concern" in the modern world. Mr. Allen is by no means the first writer to address this phenomenon, but he may be the best qualified. He has through the years established himself as among the best-informed commentators on the Vatican and the state of the Roman Catholic Church, and hearing so many contacts recount stories of persecution and discrimination has naturally sensitized him to anti-Christian campaigns, and by no means only those directed against Catholics. . . . In cruder hands, "The Global War on Christians" could easily have turned into an anti-Islamic rant. Yet while Mr. Allen devotes full attention to the evil deeds of Islamists in Iraq, Nigeria and elsewhere, he also refutes the myth "that it's all about Islam." Over the past century, some of the very worst anti-Christian persecutors have been fanatically anti-religious, commonly driven by Marxist-Leninist ideology. Islam, evidently, has nothing to do with the atrocities of the North Korean regime, which has made its country perhaps the worst single place in the world to be a Christian: The government has killed thousands of Christians and imprisoned tens of thousands more, in hideous conditions. Nor does Mr. Allen succumb to the common temptation to concentrate so much on Muslim misdeeds that we ignore savage and persistent persecutions by Hindu fanatics—the pogroms, the forced conversions, the mob attacks against churches, often committed with the tacit acquiescence of police and local governments. Read the rest here. Coming from Philip Jenkins of Baylor University, that's a trust- and attention worthy review.

Published on December 21, 2013 00:00

December 20, 2013

And It Arrived on My Birthday! A Review Copy from Gracewing

This looks like a fascinating study of a period that's not so well known in the history of Catholicism in England after the English Reformation--and I do agree that the usual view of that era is that it was very quiet and stagnant:

This looks like a fascinating study of a period that's not so well known in the history of Catholicism in England after the English Reformation--and I do agree that the usual view of that era is that it was very quiet and stagnant: Persecution Without Martyrdom: The Catholics of North-East England in the Age of the Vicars Apostolic 1688-1850 , by Leo Gooch

Publisher's Blurb: Until comparatively recently, historical studies of English Catholicism have lavished attention on the ‘Age of Martyrs’ of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries or on the ‘Second Spring’ of the nineteenth century, while the eighteenth, a century of ‘persecution without martyrdom’ as Edwin Burton described the life and times of Richard Challoner, is largely passed over. That neglect is wholly unwarranted. The creation of the four Vicariates Apostolic in 1688 marks the foundation of the modern Roman Catholic Church in England AND Wales and a series of significant ecclesiastical developments affecting the disposition and operation of the mission followed over the next century and a half: its emergence from ‘seigneurial’ rule, its shift from its rural strongholds into the towns, and its metamorphosis into a centrally-managed organization. In the secular field, this was the age when major political crises relating to Catholicism arose, when Catholics threw off discrimination and oppression and by degrees emerged from recusancy to full citizenship; and when the sociological character of the English Catholics changed completely. Theses were all important enough singly, but cumulatively they amounted to nothing less than a radical transformation of the structure and outlook of the English Catholics. The later achievements of the Church of Cardinals Manning, Wiseman and Newman could not possibly have been won without the perseverance and vigour of the eighteenth century recusants.

I look forward to reading it and reviewing it.

Published on December 20, 2013 23:00

"A Christmas Carol" on the Silver Screen

Last night, TCM showed several film adaptations of Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol, starting with the Albert Finney musical and then moving on to the classic Alistair Sim version, the first sound version, the Reginald Owen version, and a Rod Serling adaptation.

As with all film adaptations of literary works, the different versions take liberties with the text: Scrooge!, the musical, adds a scene with Marley and Scrooge in Hell--Scrooge is to be Satan's clerk and finds himself wrapped in heavy chains in a ice cold office, colder than the office he kept for his clerk, Bob Cratchit.

Except for the rousingly ironic "Thank You Very Much", I don't think the musical numbers are that memorable, and the Ghost of Christmas Present does not reveal the boy and girl, Ignorance and Want before he departs his time on earth. Once he's transformed and converted, Ebenezer visits the Cratchit house to deliver the prize turkey and presents, all dressed up as Father Christmas.

The Reginald Owen version also shows Scrooge visiting the Cratchit house on Christmas Day--I think both of those changes are mistakes because it eliminates the tension and surprise on December 26 when poor Bob Cratchit arrives late to work and fears he'll lose his job.

The Alistair Sim version is excellent, including the young Ebenezer, George Cole, and includes that most Dickensian scene of the undertaker, housekeeper, and laundress selling Scrooge's few earthly possessions.

Truly, my favorite is the 1984 George C. Scott version, made for television (CBS). The cast is very strong throughout from the protagonist to Susannah York (Mrs. Cratchit), David Warner (Bob), Roger Rees (Fred, Scrooge's nephew), Frank Finlay (as Marley's Ghost), and another good younger Scrooge, Mark Strickson, who once played a Doctor Who sidekick (the Fifth Doctor).

Through the movie adaptations, the impact of A Christmas Carol continues.

God bless us, everyone!

Published on December 20, 2013 04:00

December 19, 2013

Old English O Antiphons: O Key of David

A Clerk of Oxford posts this fascinating background to the O Antiphons, including the Old English versions from the Exeter Book:

We are now in the last days of Advent, the season of the O Antiphons. These ancient antiphons, sung at Vespers in the week before Christmas, retain a remarkable hold on the imagination today - just as they did twelve hundred years ago for one Anglo-Saxon poet, who turned them into a series of short poems in English. For the next few days I want to post the Old English poetic versions of the O Antiphons, which are much more than translations of the Latin texts: they are exquisite poetic meditations on the rich imagery of the antiphons, responding to them in subtle and creative ways. In translating them to post here I've been astonished anew by their beauty and interest, and I hope you'll enjoy them as much as I do.

They survive in a manuscript known as the Exeter Book , an anthology of English poetry on all kinds of themes and in all kinds of forms: elegies, saints' lives, riddles, wisdom poetry, philosophical reflections, heroic laments, and many poems which resist classification. The O Antiphons are the first poems in the collection, and they were probably composed some time earlier than the date of the tenth-century manuscript, perhaps around the year 800. They are anonymous, though once attributed by scholars to Cynewulf , and they long suffered from being lumped together with the poems which follow them in the manuscript (which also concern Christ, so you will sometimes find them being called 'Christ I' or 'Christ A'). However, they deserve to be treated, and appreciated, separately and on their own terms, as a collection of individual poems linked by their common source in the O Antiphons.

Read the rest here.

We are now in the last days of Advent, the season of the O Antiphons. These ancient antiphons, sung at Vespers in the week before Christmas, retain a remarkable hold on the imagination today - just as they did twelve hundred years ago for one Anglo-Saxon poet, who turned them into a series of short poems in English. For the next few days I want to post the Old English poetic versions of the O Antiphons, which are much more than translations of the Latin texts: they are exquisite poetic meditations on the rich imagery of the antiphons, responding to them in subtle and creative ways. In translating them to post here I've been astonished anew by their beauty and interest, and I hope you'll enjoy them as much as I do.

They survive in a manuscript known as the Exeter Book , an anthology of English poetry on all kinds of themes and in all kinds of forms: elegies, saints' lives, riddles, wisdom poetry, philosophical reflections, heroic laments, and many poems which resist classification. The O Antiphons are the first poems in the collection, and they were probably composed some time earlier than the date of the tenth-century manuscript, perhaps around the year 800. They are anonymous, though once attributed by scholars to Cynewulf , and they long suffered from being lumped together with the poems which follow them in the manuscript (which also concern Christ, so you will sometimes find them being called 'Christ I' or 'Christ A'). However, they deserve to be treated, and appreciated, separately and on their own terms, as a collection of individual poems linked by their common source in the O Antiphons.

Read the rest here.

Published on December 19, 2013 22:30

Cosmo Lang, Archbishop of Canterbury

I watched

The King's Speech

on DVD last night, and noted again the role of the Archbishop of Canterbury, played by Sir Derek Jacobi. Cosmo Lang was the Archbishop who buried George V, excoriated Edward VIII after his abdication, and crowned George VI and his wife Elizabeth--and Elizabeth II, too. He is not portrayed very sympathetically in the movie: a bit of a prig about Lionel Logue, etc--and this reviewer of a biography of an Archbishop of Canterbury who reigned over the Church of England during a crucial modern era notes that portrayal:

I watched

The King's Speech

on DVD last night, and noted again the role of the Archbishop of Canterbury, played by Sir Derek Jacobi. Cosmo Lang was the Archbishop who buried George V, excoriated Edward VIII after his abdication, and crowned George VI and his wife Elizabeth--and Elizabeth II, too. He is not portrayed very sympathetically in the movie: a bit of a prig about Lionel Logue, etc--and this reviewer of a biography of an Archbishop of Canterbury who reigned over the Church of England during a crucial modern era notes that portrayal:'I HATE Cosmo Lang!’ exclaimed a member of the audience when Robert Beaken spoke to a seminar at the IHR about Lang, archbishop of Canterbury and subject of this important reassessment. As Beaken rightly notes, Lang’s reputation has suffered in the years since his death. His time as archbishop (1928–42) spanned years of economic depression, the rise of fascism, a royal abdication and the outbreak of world war. But, despite this, the prevailing picture has been of a figure caught in the headlights, reactive rather than in the lead, a puritan and a snob; this image has not been altered by his portrayal (by Derek Jacobi) in the recent film, The King’s Speech. Lang’s case was not helped by the biography by J. G. Lockhart, published in 1949. Written without any particular acquaintance with Lang or access to his official papers, Lockhart’s book has long been unsatisfactory, but it has taken until now for a replacement to appear; and Beaken’s study goes a long way towards superseding Lockhart and presenting Lang afresh.

The book has three primary concerns: with Lang’s relationship with the monarchy; with the disputed process of liturgical reform within the Church of England; and with the Second World War. Chapter seven deals with the last, presenting a panoramic view of Lang’s work in the first and darkest days of the war, when Lang was in his mid-70s. Beaken very effectively documents Lang’s interventions at the highest level: in the articulation of peace aims; in negotiating the rhetorically difficult transformation of Soviet Russia from enemy to ally; in articulating the need for national intercession and for remembrance of the 1914–18 conflict in changed circumstances. There are important refinements to the literature in relation to Lang’s early opposition to the obliteration bombing of Germany (191–3), and (in response to the work of Tom Lawson) concerning who knew what and when within the Church in relation to the Holocaust (206–7).

But these national affairs were not the limit of an archbishop’s concerns. Beaken very effectively documents Lang’s interventions in relation to refugees, evacuees and conscientious objectors, to venereal disease in the army abroad, and to the observance of the Sabbath at home. Lang was supportive of the government and the war effort because he strongly believed that the struggle was a just and necessary one. At the same time, there were limits to what could be morally acceptable even in war, and Lang intervened in private and public as far as there was any likelihood of those efforts being effective.

Read the rest here, including the author's response to the review.

Published on December 19, 2013 04:00

December 17, 2013

Advent Ember Days

As this site reminds us:

Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday after Gaudete Sunday (3rd Sunday of Advent) are known as "Advent Embertide," and they come near the beginning of the Season of Winter (December, January, February). Liturgically, the readings for the days' Masses follow along with the general themes of Advent, opening up with Wednesday's Introit of Isaias 45: 8 and Psalm 18:2 :

Drop down dew, ye heavens, from above, and let the clouds rain the Just: let the earth be opened and bud forth a Savior. The heavens show forth the glory of God: and the firmament declareth the work of His hands.Wednesday's and Saturday's Masses will include one and four Lessons, respectively, with all of them concerning the words of the Prophet Isaias except for the last lesson on Saturday, which comes from Daniel and recounts how Sidrach, Misach, and Abdenago are saved from King Nabuchodonosor's fiery furnace by an angel. This account, which is followed by a glorious hymn, is common to all Embertide Saturdays but for Whit Embertide.

The Gospel readings for the three days concern, respectively, the Annunciation (Luke 1:26-28), Visitation (Luke 1:37-47), and St. John the Baptist's exhorting us to "prepare the way of the Lord and make straight His paths" (Luke 3:1-6). The Rorate Caeli performed above at Hereford Cathedral is from William Byrd's Gradualia: ℣ Rorate coeli desuper et nubes pluant justum

(Drop down dew, ye heavens, from above, and let the clouds rain the just)

℟ Aperiatur terra et germinet salvatorem"

(Let the earth be opened and send forth a Saviour"). Ps. Benedixisti, Domine, terram tuam: avertisti captivitatem IacobO Lord thou hast blessed thy land: thou hast turned away the captivity of Jacob.

Gloria Patri, et Filio, et Spiritui Sancto . . .

Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit . . . It is part of a Votive Mass for Our Lady during Advent and you may find the sheet music here.

Published on December 17, 2013 22:30

December 16, 2013

Dom Prosper Gueranger on the First O Antiphon: O Sapientia

This site has the prayers composed by Dom Prosper Gueranger for the O Antiphons for the Magnifcat canticle at Vespers, December 17 through 23, starting with "O Wisdom, that proceedest from the mouth of the Most High, reaching from end to end mightily, and disposing all things sweetly, come

and teach us the way of prudence.":

O uncreated Wisdom, who art so soon to make Thyself visible to Thy creatures, truly Thou disposest all things. It is by Thy permission that the emperor Augustus issues a decree ordering the enrollment of the whole world. Each citizen of the vast empire is to have his name enrolled in the city of his birth. This prince has no other object in this order, which sets the world in motion, but his own ambition. Men go to and fro by millions, and an unbroken procession traverses the immense Roman world; men think they are doing the bidding of man, and it is God whom they are obeying. This world-wide agitation has really but one object; it is, to bring to Bethlehem a man and woman who live at Nazareth in Galilee, in order that this woman, who is unknown to the world but dear to heaven, and who is at the close of the ninth month since she conceived her Child, may give birth to this Child in Bethlehem; for the Prophet has said of Him: ‘His going forth is from the beginning, from the days of eternity. And thou, 0 Bethlehem! art not the least among the thousand cities of Judah, for out of thee He shall come.’O divine Wisdom! how strong art Thou in thus reaching Thine ends by means which are infallible, though hidden; and yet, how sweet, offering no constraint to man’s free-will; and withal, how fatherly, in providing for our necessities! Thou choosest Bethlehem for Thy birth-place, because Bethlehem signifies the house of bread. In this, Thou teachest us that Thou art our Bread, the nourishment and support of our life. With God as our food, we cannot die. O Wisdom of the Father, living Bread that hast descended from heaven, come speedily into us, that thus we may approach to Thee and be enlightened by Thy light, and by that prudence which leads to salvation.

OSV's The Catholic Answer Magazine features this article describing the O Antiphons and the well-known translation by John Mason Neale.

and teach us the way of prudence.":

O uncreated Wisdom, who art so soon to make Thyself visible to Thy creatures, truly Thou disposest all things. It is by Thy permission that the emperor Augustus issues a decree ordering the enrollment of the whole world. Each citizen of the vast empire is to have his name enrolled in the city of his birth. This prince has no other object in this order, which sets the world in motion, but his own ambition. Men go to and fro by millions, and an unbroken procession traverses the immense Roman world; men think they are doing the bidding of man, and it is God whom they are obeying. This world-wide agitation has really but one object; it is, to bring to Bethlehem a man and woman who live at Nazareth in Galilee, in order that this woman, who is unknown to the world but dear to heaven, and who is at the close of the ninth month since she conceived her Child, may give birth to this Child in Bethlehem; for the Prophet has said of Him: ‘His going forth is from the beginning, from the days of eternity. And thou, 0 Bethlehem! art not the least among the thousand cities of Judah, for out of thee He shall come.’O divine Wisdom! how strong art Thou in thus reaching Thine ends by means which are infallible, though hidden; and yet, how sweet, offering no constraint to man’s free-will; and withal, how fatherly, in providing for our necessities! Thou choosest Bethlehem for Thy birth-place, because Bethlehem signifies the house of bread. In this, Thou teachest us that Thou art our Bread, the nourishment and support of our life. With God as our food, we cannot die. O Wisdom of the Father, living Bread that hast descended from heaven, come speedily into us, that thus we may approach to Thee and be enlightened by Thy light, and by that prudence which leads to salvation.

OSV's The Catholic Answer Magazine features this article describing the O Antiphons and the well-known translation by John Mason Neale.

Published on December 16, 2013 22:30

December 15, 2013

French Romantic Catholics

Romantic Catholics: France's Postrevolutionary Generation in Search of a Modern Faith

is due out from Cornell University Press next March:

Romantic Catholics: France's Postrevolutionary Generation in Search of a Modern Faith

is due out from Cornell University Press next March: In this well-written and imaginatively structured book, Carol E. Harrison brings to life a cohort of nineteenth-century French men and women who argued that a reformed Catholicism could reconcile the divisions in French culture and society that were the legacy of revolution and empire. They include, most prominently, Charles de Montalembert, Pauline Craven, Amélie and Frédéric Ozanam, Léopoldine Hugo, Maurice de Guérin, and Victorine Monniot. The men and women whose stories appear in Romantic Catholics were bound together by filial love, friendship, and in some cases marriage. Harrison draws on their diaries, letters, and published works to construct a portrait of a generation linked by a determination to live their faith in a modern world.

Rejecting both the atomizing force of revolutionary liberalism and the increasing intransigence of the church hierarchy, the romantic Catholics advocated a middle way, in which a revitalized Catholic faith and liberty formed the basis for modern society. Harrison traces the history of nineteenth-century France and, in parallel, the life course of these individuals as they grow up, learn independence, and take on the responsibilities and disappointments of adulthood. Although the shared goals of the romantic Catholics were never realized in French politics and culture, Harrison's work offers a significant corrective to the traditional understanding of the opposition between religion and the secular republican tradition in France.

The Table of Contents:

Introduction: Romantic Catholics and the Two Frances 1. First Communion: The Most Beautiful Day in the Lives and Deaths of Little Girls 2. The Education of Maurice de Guérin 3. The Dilemma of Obedience: Charles de Montalembert, Catholic Citizen4. Pauline Craven's Holy Family: Writing the Modern Saint

5. Frédéric and Amélie Ozanam: Charity, Marriage, and the Catholic Social6. A Free Church in a Free State: The Roman Question Epilogue: The Devout Woman of the Third Republic and the Eclipse of Catholic Fraternity

Looks fascinating.

Published on December 15, 2013 22:30