Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 252

December 6, 2013

Janet Cardiff: The Forty Part Motet at The Cloisters

Closing tomorrow at the Metropolitan Museum/Cloisters in New York City:

The Forty Part Motet (2001), a sound installation by Janet Cardiff (Canadian, born 1957), will be the first presentation of contemporary art at The Cloisters. Regarded as the artist's masterwork, and consisting of forty high-fidelity speakers positioned on stands in a large oval configuration throughout the Fuentidueña Chapel, the fourteen-minute work, with a three-minute spoken interlude, will continuously play an eleven-minute reworking of the forty-part motet Spem in alium numquam habui (1556?/1573?) by Tudor composer Thomas Tallis (ca. 1505–1585). Spem in alium, which translates as "In No Other Is My Hope," is perhaps Tallis's most famous composition. Visitors are encouraged to walk among the loudspeakers and hear the individual unaccompanied voices—bass, baritone, alto, tenor, and child soprano—one part per speaker—as well as the polyphonic choral effect of the combined singers in an immersive experience. The Forty Part Motet is most often presented in a neutral gallery setting, but in this case the setting is the Cloisters' Fuentidueña Chapel, which features the late twelfth-century apse from the church of San Martín at Fuentidueña, near Segovia, Spain, on permanent loan from the Spanish Government. Set within a churchlike gallery space, and with superb acoustics, it has for more than fifty years proved a fine venue for concerts of early music.

The article on Spem in alium suggests that Tallis wrote this brilliant piece during Mary I's reign, not during Elizabeth I's. After all, the words are drawn from the book of Judith, one of the Deutero-Canonical works usually omitted from Protestant Bibles. The conclusion is:

All these considerations together point to a planned premiere of Spem in alium in Nonsuch Palace in 1556, with Queen Mary Tudor as the intended dedicatee. In the event, that premiere seems not to have occurred—most likely because of the death of Fitzalan's son and daughter in 1556, and of his wife in 1557. The most likely first performance was therefore in 1559 or 1567, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth. (The newly crowned Elizabeth spent five days at Nonsuch in August 1559, and we know from Wateridge's anecdote quoted above that the piece was performed in Arundel House in London; the date of that performance has now been determined to have been 1567.) Queen Elizabeth is therefore most likely the first English monarch to have heard Spem in alium, although the evidence suggests that it was composed for her half-sister, Queen Mary Tudor, as a fortieth-birthday present.

Spem in alium

Spem in alium nunquam

habui praeter in te, Deus Israel:

qui irasceris et propitius eris,

et omnia peccata hominum

in tribulatione dimittis:

Domine Deus, Creator caeli et

respice humilitatem nostram.

Translation:

I have never put my hope in any

besides you, O God of Israel,

who grows angry, but then,

becoming gracious, forgives all the

sins of men in their tribulation:

Lord God, creator of heaven and

earth, look upon our lowliness.

I have read that one reason Spem in Alium is so popular now is that it's featured in that "grey" book series. The exhibit has had quite an effect on visitors and The Cloisters' website for the exhibit is quite detailed. Here is another review.

Published on December 06, 2013 22:30

December 5, 2013

An Advent Hymn: Creator of the Stars of Night

A Clerk of Oxford features this hymn in this blog post, which features different translations from the Middle Ages. The modern translation I'm most familiar with is, of course, by John Mason Neale:

A Clerk of Oxford features this hymn in this blog post, which features different translations from the Middle Ages. The modern translation I'm most familiar with is, of course, by John Mason Neale:Creator of the stars of night,

Thy people’s everlasting light,

Jesu, Redeemer, save us all,

And hear Thy servants when they call.

Thou, grieving that the ancient curse

Should doom to death a universe,

Hast found the medicine, full of grace,

To save and heal a ruined race.

Thou cam’st, the Bridegroom of the bride,

As drew the world to evening-tide;

Proceeding from a virgin shrine,

The spotless Victim all divine.

At Whose dread Name, majestic now,

All knees must bend, all hearts must bow;

And things celestial Thee shall own,

And things terrestrial, Lord alone.

O Thou Whose coming is with dread

To judge and doom the quick and dead,

Preserve us, while we dwell below,

From every insult of the foe.

To God the Father, God the Son,

And God the Spirit, Three in One,

Laud, honor, might, and glory be

From age to age eternally. Amen.

And the Latin original:

Conditor alme siderum

aetérna lux credéntium

Christe redémptor

ómnium exáudi preces súpplicum

Qui cóndolens intéritu

mortis perire saeculum

salvásti mundum languidum

donnas reis remedium.

Vergénte mundi véspere

uti sponsus de thálamo

egréssus honestissima

Virginis matris cláusula.

Cuius forti ponténtiae

genu curvántur ómnia

caeléstia, terréstia

nutu faténtur súbdita.

Te, Sancte fide quáesumus,

venture iudex sáeculi,

consérva nos in témpore

hostis a telo perfidi.

Sit, Christe rex piissime

tibi Patríque glória

cum Spíritu Paráclito

in sempitérna sáecula.

Amen.

So why is it particularly an Advent hymn, often sung at Vespers? It has been part of the Church's Divine Office for centuries, sung to Plainchat (Mode IV). The hymn speaks of Christ's coming for our salvation in terms of eternity and the universe. He created the stars and all light and He comes into the world as Incarnate man to bring us even greater light. This blog post, from a Benedictine monk in Ireland, quotes Pope Benedict XVI from his encyclical Spe Salve:

At the very moment when the Magi, guided by the star, adored Christ the new king, astrology came to an end, because the stars were now moving in the orbit determined by Christ. This scene, in fact, overturns the world-view of that time, which in a different way has become fashionable once again today. It is not the elemental spirits of the universe, the laws of matter, which ultimately govern the world and mankind, but a personal God governs the stars, that is, the universe; it is not the laws of matter and of evolution that have the final say, but reason, will, love–a Person. And if we know this Person and he knows us, then truly the inexorable power of material elements no longer has the last word; we are not slaves of the universe and of its laws, we are free.

Published on December 05, 2013 22:30

December 4, 2013

St. John Almond on the Son Rise Morning Show

I'll be on the

Son Rise Morning Show

today at about 7:45 a.m. Eastern/6:45 a.m. Central to talk about today's English Martyr, St. John Almond. Last year was the 400th anniversary of his execution and the Archdiocese of Liverpool remembered the martyr with a special Mass at a parish in his hometown:

St John Almond was born in Allerton, and so the people of St Bernadette’s can rightfully call him one of their own. He was educated in Much Woolton before moving to Ireland, later travelling to Rheims and then on to Rome where he trained for the sacred priesthood. St John was ordained in 1598, returning to the ‘English Mission’ in 1602. The full weight of the penal legislation against Catholics was in place by this time and so according to the 1585 Act ‘Against Jesuits, Seminary Priests and other such like disobedient persons’, as a Catholic priest come from abroad specifically with the intention of preaching and teaching the Catholic faith, celebrating the Mass and other sacraments and reconciling others to the Catholic faith (‘persuading to popery’, as it was known) St John and his fellow priests, were liable to be charged with high treason. Usually after a period of harsh imprisonment for the purposes of interrogation, which was often accompanied by torture, Catholic priests, after sentence, would be hung (briefly in order that choking may occur), drawn (disembowelled whilst remaining conscious), and quartered (beheaded and dismembered).

St John was a distinguished student, gaining a Doctorate in Divinity, and at a relatively early age he was noted for his theological knowledge and his ability as an apologist and defender of the faith. During his trial he debated points of faith with the protestant Bishop of London, Dr King, and even on the scaffold prior to execution he dealt adeptly with attempts by two protestant ministers to humiliate him and rubbish his arguments. He dealt so eloquently with his three opponents that they had to admit that although they disagreed with him, nevertheless, he was indeed skilful in debate. Dr King said of him that he was, ‘one of the learnedness and insolentest of the Popish priests [sic]’. Before his death St John prayed, distributed alms to the poor, and gave his final oration, concluding with these words: ‘To use this life well is the pathway through death to everlasting life’. . . .

St. John Almond was arrested in 1608 and then again in 1612; he was condemned to death because he was a Catholic priest in England under the Elizabethan statute of 1585 that made his presence in country an act of treason. Several priests had escaped from prison and St. John Almond was chosen to suffer the consequences. In 1612, both the Archbishop of Canterbury George Abbott and the Bishop of London John King were more strident in their anti-Catholicism and more zealous to prosecute Catholic priests. Nonetheless, St. John Almond is one of only three priests executed in 1612 (the others were Blessed Maurus Scott, OSB and Blessed Richard Newport on May 30) and it's interesting to note that he had escaped execution in 1608 when England and James I were still in the thrall of the Gunpowder Plot.

James I believed that persecution was the sign of a false church (which also shows he knew this persecution to be on religious grounds, not merely for state security). Also, the diplomatic positions that James took emphasized peace and conciliation with Catholic Spain or even France, so persecution would be suspended during when it was the diplomatic thing to do--when he was negotiating for the Spanish or French matches, for example. The ambassadors of Spain actively campaigned for priests to be freed and exiled. On the side of enforcing the Elizabethan statutes against Catholic priests were his Archbishop of Canterbury and Parliament, so a few sacrificial lambs would be offered up from time to time, and St. John Almond was definitely one, suffering not only for his priesthood but for the escape of fellow priests. He is one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales canonized by Pope Paul VI in 1970.

St John Almond was born in Allerton, and so the people of St Bernadette’s can rightfully call him one of their own. He was educated in Much Woolton before moving to Ireland, later travelling to Rheims and then on to Rome where he trained for the sacred priesthood. St John was ordained in 1598, returning to the ‘English Mission’ in 1602. The full weight of the penal legislation against Catholics was in place by this time and so according to the 1585 Act ‘Against Jesuits, Seminary Priests and other such like disobedient persons’, as a Catholic priest come from abroad specifically with the intention of preaching and teaching the Catholic faith, celebrating the Mass and other sacraments and reconciling others to the Catholic faith (‘persuading to popery’, as it was known) St John and his fellow priests, were liable to be charged with high treason. Usually after a period of harsh imprisonment for the purposes of interrogation, which was often accompanied by torture, Catholic priests, after sentence, would be hung (briefly in order that choking may occur), drawn (disembowelled whilst remaining conscious), and quartered (beheaded and dismembered).

St John was a distinguished student, gaining a Doctorate in Divinity, and at a relatively early age he was noted for his theological knowledge and his ability as an apologist and defender of the faith. During his trial he debated points of faith with the protestant Bishop of London, Dr King, and even on the scaffold prior to execution he dealt adeptly with attempts by two protestant ministers to humiliate him and rubbish his arguments. He dealt so eloquently with his three opponents that they had to admit that although they disagreed with him, nevertheless, he was indeed skilful in debate. Dr King said of him that he was, ‘one of the learnedness and insolentest of the Popish priests [sic]’. Before his death St John prayed, distributed alms to the poor, and gave his final oration, concluding with these words: ‘To use this life well is the pathway through death to everlasting life’. . . .

St. John Almond was arrested in 1608 and then again in 1612; he was condemned to death because he was a Catholic priest in England under the Elizabethan statute of 1585 that made his presence in country an act of treason. Several priests had escaped from prison and St. John Almond was chosen to suffer the consequences. In 1612, both the Archbishop of Canterbury George Abbott and the Bishop of London John King were more strident in their anti-Catholicism and more zealous to prosecute Catholic priests. Nonetheless, St. John Almond is one of only three priests executed in 1612 (the others were Blessed Maurus Scott, OSB and Blessed Richard Newport on May 30) and it's interesting to note that he had escaped execution in 1608 when England and James I were still in the thrall of the Gunpowder Plot.

James I believed that persecution was the sign of a false church (which also shows he knew this persecution to be on religious grounds, not merely for state security). Also, the diplomatic positions that James took emphasized peace and conciliation with Catholic Spain or even France, so persecution would be suspended during when it was the diplomatic thing to do--when he was negotiating for the Spanish or French matches, for example. The ambassadors of Spain actively campaigned for priests to be freed and exiled. On the side of enforcing the Elizabethan statutes against Catholic priests were his Archbishop of Canterbury and Parliament, so a few sacrificial lambs would be offered up from time to time, and St. John Almond was definitely one, suffering not only for his priesthood but for the escape of fellow priests. He is one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales canonized by Pope Paul VI in 1970.

Published on December 04, 2013 22:30

December 2, 2013

Not Shakespeare's Moor, but His More

The role of More, six times the length of the second-biggest part, is one of the largest in the entire repertoire of Elizabethan and Jacobean drama. It calls for an actor of great versatility: we see him commanding both a crowd and a council chamber, meditating in soliloquy and taking rapid action, philosophising and philanthropising. He is a prankster, a Christian and a voice of reason, truly the wisest fool in Christendom (though it is disappointing that his encounter with his great fellow philosopher and wit, Erasmus of Rotterdam, comes to so little). If, as seems likely, the Shakespearean intervention in the script was intended for a production by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, then one can see why they wanted to stage the play: it would have been a magnificent showcase for their lead tragedian and Shakespeare’s intimate friend Richard Burbage.

Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen write about Shakespeare's colloboration on a play titled Sir Thomas More:

As a tragedy, Sir Thomas More belongs beside the Chamberlain’s Men’s Thomas Lord Cromwell and Shakespeare and Fletcher’s Henry VIII as the story of the rise and fall of a royal counsellor in the turbulent time of the English Reformation. More ascends from Sheriff of London to Lord Chancellor, but falls from the king’s favour when he refuses to participate in the process of enacting the break from Rome. It’s a satisfying arc: we get a full ascendancy, a brief period of power and favour, and then a slow descent to the execution. The moments of More’s career chosen to illustrate this movement are well chosen, oscillating between his most public appearances (the May Day riots, his execution) and private ones (his conversation with Erasmus, his defence of his position to his family). In balancing character and plot, the dramatists create a coherent portrait that, ultimately, goes to show the fickleness of favour and the cost of piety. In the closing scenes, we see him preparing for death with dignity and grace. Whereas the usual scenario in such dramas places the condemned man alone in his cell, sometimes in conversation with his keeper, here we also witness More’s farewell to his family. He is seen as a husband and parent, not just a holy man and a politician.

They also discuss a manuscript with Shakespeare's handwriting:

The exact circumstances in which Shakespeare made his contribution to Sir Thomas More will never be known, though scholars now lean strongly to the view that he did so when at the height of his powers in the early 1600s, not in a prior stage of his career, as was once supposed. But, whatever the date and context, an overwhelming body of internal evidence, in the form of unique marks of orthography, spelling, vocabulary and literary technique, attests that the so-called “Hand D” in the manuscript is truly his. This is Shakespeare in the act of composition, writing rapidly, occasionally changing a word or scratching out a line, mining his capacious imagination and minting his incomparable poetic imagery. But it is also Shakespeare the collaborator, building on the work of other dramatists and contributing to a magnificent team effort.

Read the rest here.

From the play, More's farewell to his family:

Be comforted, good wife, to live and love my children;

For with thee leave I all my care of them.—

Son Roper, for my sake that have loved thee well,

And for her virtue's sake, cherish my child.—

Girl, be not proud, but of thy husband's love;

Ever retain thy virtuous modesty;

That modesty is such a comely garment

As it is never out of fashion, sits as fair

upon the meaner woman as the empress;

No stuff that gold can buy is half so rich,

Nor ornament that so becomes a woman.

Live all and love together, and thereby

You give your father a rich obsequy.

And his execution scene--wit writ in prose:

My Lords of Surrey and Shrewsbury, give me your hands. Yet before we….ye see, though it pleaseth the king to raise me thus high, yet I am not proud, for the higher I mount, the better I can see my friends about me. I am now on a far voyage, and this strange wooden horse must bear me thither; yet I perceive by your looks you like my bargain so ill, that there's not one of ye all dare enter with me. Truly, here's a most sweet gallery; [Walking.] I like the air of it better than my garden at Chelsea. By your patience, good people, that have pressed thus into my bedchamber, if you'll not trouble me, I'll take a sound sleep here.

SHREWSBURY.

My lord, twere good you'ld publish to the world

Your great offence unto his majesty.MORE. My lord, I'll bequeath this legacy to the hangman, [Gives him his gown.] and do it instantly. I confess, his majesty hath been ever good to me; and my offence to his highness makes me of a state pleader a stage player (though I am old, and have a bad voice), to act this last scene of my tragedy. I'll send him (for my trespass) a reverend head, somewhat bald; for it is not requisite any head should stand covered to so high majesty: if that content him not, because I think my body will then do me small pleasure, let him but bury it, and take it.

SURREY.

My lord, my lord, hold conference with your soul;

You see, my lord, the time of life is short.MORE. I see it, my good lord; I dispatched that business the last night. I come hither only to be let blood; my doctor here tells me it is good for the headache.HANGMAN.

I beseech thee, my lord, forgive me!MORE.

Forgive thee, honest fellow! why?HANGMAN.

For your death, my lord.MORE. O, my death? I had rather it were in thy power to forgive me, for thou hast the sharpest action against me; the law, my honest friend, lies in thy hands now: here's thy fee [His purse.]; and, my good fellow, let my suit be dispatched presently; for tis all one pain, to die a lingering death, and to live in the continual mill of a lawsuit. But I can tell thee, my neck is so short, that, if thou shouldst behead an hundred noblemen like myself, thou wouldst ne'er get credit by it; therefore (look ye, sir), do it handsomely, or, of my word, thou shalt never deal with me hereafter. HANGMAN.

I'll take an order for that, my lord.

MORE. One thing more; take heed thou cutst not off my beard: oh, I forgot; execution passed upon that last night, and the body of it lies buried in the Tower.—Stay; ist not possible to make a scape from all this strong guard? it is. There is a thing within me, that will raise And elevate my better part bove sight Of these same weaker eyes; and, Master Shrieves, For all this troop of steel that tends my death, I shall break from you, and fly up to heaven. Let's seek the means for this.

Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen write about Shakespeare's colloboration on a play titled Sir Thomas More:

As a tragedy, Sir Thomas More belongs beside the Chamberlain’s Men’s Thomas Lord Cromwell and Shakespeare and Fletcher’s Henry VIII as the story of the rise and fall of a royal counsellor in the turbulent time of the English Reformation. More ascends from Sheriff of London to Lord Chancellor, but falls from the king’s favour when he refuses to participate in the process of enacting the break from Rome. It’s a satisfying arc: we get a full ascendancy, a brief period of power and favour, and then a slow descent to the execution. The moments of More’s career chosen to illustrate this movement are well chosen, oscillating between his most public appearances (the May Day riots, his execution) and private ones (his conversation with Erasmus, his defence of his position to his family). In balancing character and plot, the dramatists create a coherent portrait that, ultimately, goes to show the fickleness of favour and the cost of piety. In the closing scenes, we see him preparing for death with dignity and grace. Whereas the usual scenario in such dramas places the condemned man alone in his cell, sometimes in conversation with his keeper, here we also witness More’s farewell to his family. He is seen as a husband and parent, not just a holy man and a politician.

They also discuss a manuscript with Shakespeare's handwriting:

The exact circumstances in which Shakespeare made his contribution to Sir Thomas More will never be known, though scholars now lean strongly to the view that he did so when at the height of his powers in the early 1600s, not in a prior stage of his career, as was once supposed. But, whatever the date and context, an overwhelming body of internal evidence, in the form of unique marks of orthography, spelling, vocabulary and literary technique, attests that the so-called “Hand D” in the manuscript is truly his. This is Shakespeare in the act of composition, writing rapidly, occasionally changing a word or scratching out a line, mining his capacious imagination and minting his incomparable poetic imagery. But it is also Shakespeare the collaborator, building on the work of other dramatists and contributing to a magnificent team effort.

Read the rest here.

From the play, More's farewell to his family:

Be comforted, good wife, to live and love my children;

For with thee leave I all my care of them.—

Son Roper, for my sake that have loved thee well,

And for her virtue's sake, cherish my child.—

Girl, be not proud, but of thy husband's love;

Ever retain thy virtuous modesty;

That modesty is such a comely garment

As it is never out of fashion, sits as fair

upon the meaner woman as the empress;

No stuff that gold can buy is half so rich,

Nor ornament that so becomes a woman.

Live all and love together, and thereby

You give your father a rich obsequy.

And his execution scene--wit writ in prose:

My Lords of Surrey and Shrewsbury, give me your hands. Yet before we….ye see, though it pleaseth the king to raise me thus high, yet I am not proud, for the higher I mount, the better I can see my friends about me. I am now on a far voyage, and this strange wooden horse must bear me thither; yet I perceive by your looks you like my bargain so ill, that there's not one of ye all dare enter with me. Truly, here's a most sweet gallery; [Walking.] I like the air of it better than my garden at Chelsea. By your patience, good people, that have pressed thus into my bedchamber, if you'll not trouble me, I'll take a sound sleep here.

SHREWSBURY.

My lord, twere good you'ld publish to the world

Your great offence unto his majesty.MORE. My lord, I'll bequeath this legacy to the hangman, [Gives him his gown.] and do it instantly. I confess, his majesty hath been ever good to me; and my offence to his highness makes me of a state pleader a stage player (though I am old, and have a bad voice), to act this last scene of my tragedy. I'll send him (for my trespass) a reverend head, somewhat bald; for it is not requisite any head should stand covered to so high majesty: if that content him not, because I think my body will then do me small pleasure, let him but bury it, and take it.

SURREY.

My lord, my lord, hold conference with your soul;

You see, my lord, the time of life is short.MORE. I see it, my good lord; I dispatched that business the last night. I come hither only to be let blood; my doctor here tells me it is good for the headache.HANGMAN.

I beseech thee, my lord, forgive me!MORE.

Forgive thee, honest fellow! why?HANGMAN.

For your death, my lord.MORE. O, my death? I had rather it were in thy power to forgive me, for thou hast the sharpest action against me; the law, my honest friend, lies in thy hands now: here's thy fee [His purse.]; and, my good fellow, let my suit be dispatched presently; for tis all one pain, to die a lingering death, and to live in the continual mill of a lawsuit. But I can tell thee, my neck is so short, that, if thou shouldst behead an hundred noblemen like myself, thou wouldst ne'er get credit by it; therefore (look ye, sir), do it handsomely, or, of my word, thou shalt never deal with me hereafter. HANGMAN.

I'll take an order for that, my lord.

MORE. One thing more; take heed thou cutst not off my beard: oh, I forgot; execution passed upon that last night, and the body of it lies buried in the Tower.—Stay; ist not possible to make a scape from all this strong guard? it is. There is a thing within me, that will raise And elevate my better part bove sight Of these same weaker eyes; and, Master Shrieves, For all this troop of steel that tends my death, I shall break from you, and fly up to heaven. Let's seek the means for this.

Published on December 02, 2013 22:30

December 1, 2013

Last Year at the Venerable English College in Rome

On December 1, 2012, the Venerable English College celebrated Martyr's Day with a special ceremony since it was the 650th anniversary year of the College's founding as a guest house for Englishmen visiting Rome on pilgrimage. The Duke and Duchess of Gloucester represented Queen Elizabeth II with this message:

In 1362, English residents in Rome established a‘Hospice of the English’ to care for English pilgrims. The Royal Arms of King Henry IV still adorn your walls to mark the 50th anniversary of that foundation and the close relationship with the Crown. The English Hospice was the origin of what has now become the Venerable English College, following its re-foundation by Pope Gregory XIII in 1579.

The presence of the Duke of Gloucester at your Martyrs’ Day Feast in this 650th anniversary year is a sign of the strength of the relationship between the United Kingdon and the Holy See. It is also recognition of the high esteem in which the Venerable English College is held as a training ground for pastors, priests and future leaders of the Catholic Church of England and Wales. You have always served as a generous and hospitable home away from home for generations of visitors to Rome, even in the most difficult times.

My good wishes go to you all, alumni, staff and students of the Venerabile, past, present and future, for your continuing prosperity.

ELIZABETH R.

Two days later, members of the College met then Pope Benedict XVI at the Vatican:

Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O’Connor, Archbishop Emeritus of Westminster (and himself Rector of the Venerabile from 1971-77) and his successor as Archbishop of Westminster, Archbishop Vincent Nichols, led the group of bishops and staff and students of the Venerabile to meet Pope Benedict on 3rd December in the Sala Clementina of the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace. Present also with them were the Secretary of the Congregation for Divine Worship, Archbishop Arthur Roche, Emeritus Bishop of Leeds; and Archbishops Peter Smith of Southwark and Bernard Longley of Birmingham. All four Archbishops are themselves former students of the Venerabile. Bishops Michael Campbell of Lancaster and Terence Drainey of Middlesbrough were also in attendance.

On entering the Sala Clementina, Pope Benedict paused to venerate the precious relic brought from the College for the occasion. This was the relic of their Protomartyr (first martyr) Saint Ralph Sherwin. Sherwin was martyred on 1st December 1581 at Tyburn in London – just yards from the site of today’s Marble Arch.

Pope Benedict recalled the spirit of the martyrs, especially St. Ralph Sherwin of the College:

Potius hodie quam cras, as Saint Ralph Sherwin said when asked to take the missionary oath, "rather today than tomorrow". These words aptly convey his burning desire to keep the flame of faith alive in England, at whatever personal cost. Those who have truly encountered Christ are unable to keep silent about him. As Saint Peter himself said to the elders and scribes of Jerusalem, "we cannot but speak of what we have seen and heard" ;">Acts 4:20). Saint Boniface, Saint Augustine of Canterbury, Saint Francis Xavier, whose feast we keep today, and so many other missionary saints show us how a deep love for the Lord calls forth a deep desire to bring others to know him. You too, as you follow in the footsteps of the College Martyrs, are the men God has chosen to spread the message of the Gospel today, in England and Wales, in Canada, in Scandinavia. Your forebears faced a real possibility of martyrdom, and it is right and just that you venerate the glorious memory of those forty-four alumni of your College who shed their blood for Christ. You are called to imitate their love for the Lord and their zeal to make him known, potius hodie quam cras. The consequences, the fruits, you may confidently entrust into God’s hands.

And he also cited St. Philip Neri's greeting to seminarians of the College during the sixteenth century:

Please be assured of an affectionate remembrance in my prayers for yourselves and for all the alumni of the Venerable English College. I make my own the greeting so often heard on the lips of a great friend and neighbour of the College, Saint Philip Neri, Salvete, flores martyrum! Commending you, and all to whom the Lord sends you, to the loving intercession of Our Lady of Walsingham, I gladly impart my Apostolic Blessing as a pledge of peace and joy in the Lord Jesus Christ. Thank you.

Read the rest of the report from last year here.

In 1362, English residents in Rome established a‘Hospice of the English’ to care for English pilgrims. The Royal Arms of King Henry IV still adorn your walls to mark the 50th anniversary of that foundation and the close relationship with the Crown. The English Hospice was the origin of what has now become the Venerable English College, following its re-foundation by Pope Gregory XIII in 1579.

The presence of the Duke of Gloucester at your Martyrs’ Day Feast in this 650th anniversary year is a sign of the strength of the relationship between the United Kingdon and the Holy See. It is also recognition of the high esteem in which the Venerable English College is held as a training ground for pastors, priests and future leaders of the Catholic Church of England and Wales. You have always served as a generous and hospitable home away from home for generations of visitors to Rome, even in the most difficult times.

My good wishes go to you all, alumni, staff and students of the Venerabile, past, present and future, for your continuing prosperity.

ELIZABETH R.

Two days later, members of the College met then Pope Benedict XVI at the Vatican:

Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O’Connor, Archbishop Emeritus of Westminster (and himself Rector of the Venerabile from 1971-77) and his successor as Archbishop of Westminster, Archbishop Vincent Nichols, led the group of bishops and staff and students of the Venerabile to meet Pope Benedict on 3rd December in the Sala Clementina of the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace. Present also with them were the Secretary of the Congregation for Divine Worship, Archbishop Arthur Roche, Emeritus Bishop of Leeds; and Archbishops Peter Smith of Southwark and Bernard Longley of Birmingham. All four Archbishops are themselves former students of the Venerabile. Bishops Michael Campbell of Lancaster and Terence Drainey of Middlesbrough were also in attendance.

On entering the Sala Clementina, Pope Benedict paused to venerate the precious relic brought from the College for the occasion. This was the relic of their Protomartyr (first martyr) Saint Ralph Sherwin. Sherwin was martyred on 1st December 1581 at Tyburn in London – just yards from the site of today’s Marble Arch.

Pope Benedict recalled the spirit of the martyrs, especially St. Ralph Sherwin of the College:

Potius hodie quam cras, as Saint Ralph Sherwin said when asked to take the missionary oath, "rather today than tomorrow". These words aptly convey his burning desire to keep the flame of faith alive in England, at whatever personal cost. Those who have truly encountered Christ are unable to keep silent about him. As Saint Peter himself said to the elders and scribes of Jerusalem, "we cannot but speak of what we have seen and heard" ;">Acts 4:20). Saint Boniface, Saint Augustine of Canterbury, Saint Francis Xavier, whose feast we keep today, and so many other missionary saints show us how a deep love for the Lord calls forth a deep desire to bring others to know him. You too, as you follow in the footsteps of the College Martyrs, are the men God has chosen to spread the message of the Gospel today, in England and Wales, in Canada, in Scandinavia. Your forebears faced a real possibility of martyrdom, and it is right and just that you venerate the glorious memory of those forty-four alumni of your College who shed their blood for Christ. You are called to imitate their love for the Lord and their zeal to make him known, potius hodie quam cras. The consequences, the fruits, you may confidently entrust into God’s hands.

And he also cited St. Philip Neri's greeting to seminarians of the College during the sixteenth century:

Please be assured of an affectionate remembrance in my prayers for yourselves and for all the alumni of the Venerable English College. I make my own the greeting so often heard on the lips of a great friend and neighbour of the College, Saint Philip Neri, Salvete, flores martyrum! Commending you, and all to whom the Lord sends you, to the loving intercession of Our Lady of Walsingham, I gladly impart my Apostolic Blessing as a pledge of peace and joy in the Lord Jesus Christ. Thank you.

Read the rest of the report from last year here.

Published on December 01, 2013 23:00

Henry VIII Upside Down is a Devil?

Even Professor Diarmaid MacCulloch thinks it could be so in this story from

The Daily Mail

:

When a British couple discovered a concealed, almost lifesize mural of Henry VIII while redecorating their 16th-century Somerset home a couple of years ago, they could not have been more excited, particularly when an expert spoke of its national importance.

But husband-and-wife Angie and Rhodri Powell were unnerved by a further chance discovery.

When the portrait of Henry on his throne is viewed upside-down his features transform into the devil, with horns and goats’ eyes. The devil appears too when the mural is viewed through a glass [mirror].

The mural is in the couple's drawing-room in the village of Milverton, the former Great Hall of the summer residence of 16th-century archdeacons of Taunton including Thomas Cranmer.

While Henry’s portrait would have been an expression of loyalty, the hidden message suggests it was commissioned by someone with quite another view of a monarch who established himself as head of the Church in England in place of the Pope.

Mrs Powell, a bestselling children’s author who writes under the name Angie Safe, and Mr Powell, a former publisher, came across the devil by accident.

I wonder what happens when you play "Greensleeves" backwards?

Professor Diarmaid MacCulloch, a specialist in the history of the church at Oxford University and Cranmer biographer, said that there was tremendous interest in optical illusion at the time, as shown by the distorted perspectives in Holbein's famous painting of The Ambassadors and William Scrots's portrait of Edward VI.

'So there’s no reason why it shouldn’t be true,' he said.

He noted that one of the then archdeacons felt 'very equivocally' about Henry VIII’s Reformation: 'It's just possible that, for a private joke, he put it in because you could only see it through an optic. I imagine that, in the privacy of his own dining-room… it could be enjoyable.'

For obvious reasons, the painting is unsigned.

Conservator Ann Ballantyne, who is working on the mural, noted that it was painted at a time when the king was behaving 'excruciatingly badly'.

I'm really not so sure about this, but it seems to be receiving quite a lot of real attention! What do you think? Check out the photos at The Daily Mail site, and let me know.

When a British couple discovered a concealed, almost lifesize mural of Henry VIII while redecorating their 16th-century Somerset home a couple of years ago, they could not have been more excited, particularly when an expert spoke of its national importance.

But husband-and-wife Angie and Rhodri Powell were unnerved by a further chance discovery.

When the portrait of Henry on his throne is viewed upside-down his features transform into the devil, with horns and goats’ eyes. The devil appears too when the mural is viewed through a glass [mirror].

The mural is in the couple's drawing-room in the village of Milverton, the former Great Hall of the summer residence of 16th-century archdeacons of Taunton including Thomas Cranmer.

While Henry’s portrait would have been an expression of loyalty, the hidden message suggests it was commissioned by someone with quite another view of a monarch who established himself as head of the Church in England in place of the Pope.

Mrs Powell, a bestselling children’s author who writes under the name Angie Safe, and Mr Powell, a former publisher, came across the devil by accident.

I wonder what happens when you play "Greensleeves" backwards?

Professor Diarmaid MacCulloch, a specialist in the history of the church at Oxford University and Cranmer biographer, said that there was tremendous interest in optical illusion at the time, as shown by the distorted perspectives in Holbein's famous painting of The Ambassadors and William Scrots's portrait of Edward VI.

'So there’s no reason why it shouldn’t be true,' he said.

He noted that one of the then archdeacons felt 'very equivocally' about Henry VIII’s Reformation: 'It's just possible that, for a private joke, he put it in because you could only see it through an optic. I imagine that, in the privacy of his own dining-room… it could be enjoyable.'

For obvious reasons, the painting is unsigned.

Conservator Ann Ballantyne, who is working on the mural, noted that it was painted at a time when the king was behaving 'excruciatingly badly'.

I'm really not so sure about this, but it seems to be receiving quite a lot of real attention! What do you think? Check out the photos at The Daily Mail site, and let me know.

Published on December 01, 2013 22:30

November 30, 2013

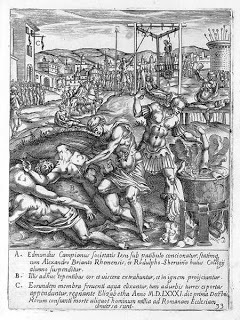

December 1, 1581: The Martyrdoms of Campion, Briant, and Sherwin

Today, of course, is the First Sunday of Advent, but it is also the anniversary of the 1581 executions of St. Edmund Campion, SJ; St. Alexander Briant, SJ, and St. Ralph Sherwin.

Today, of course, is the First Sunday of Advent, but it is also the anniversary of the 1581 executions of St. Edmund Campion, SJ; St. Alexander Briant, SJ, and St. Ralph Sherwin. St. Edmund Campion was born on January 25, 1540 in London, the son of a bookseller. He was raised a Catholic, given a scholarship to St. John's College, Oxford, when fifteen, and became a fellow when only seventeen. His brilliance attracted the attention of such leading personages as the Earl of Leicester, Robert Cecil, and even Queen Elizabeth. He took the Oath of Supremacy acknowledging Elizabeth head of the church in England and became an Anglican deacon in 1564. Doubts about Protestanism increasingly beset him, and in 1569 he went to Ireland where further study convinced him he had been in error, and he returned to Catholicism. Forced to flee the persecution unleashed on Catholics by the excommunication of Elizabeth by Pope Pius V, he went to Douai, France, where he studied theology, joined the Jesuits, and then went to Brno, Bohemia, the following year for his novitiate. He taught at the college of Prague and in 1578 was ordained there. He and Father Robert Persons were the first Jesuits chosen for the English mission and were sent to England in 1580. His activities among the Catholics, the distribution of his Decem rationes at the University Church in Oxford, and the premature publication of his famous Brag (which he had written to present his case if he was captured) made him the object of one of the most intensive manhunts in English history. He was betrayed at Lyford, near Oxford, imprisoned in the Tower of London, and when he refused to apostatize when offered rich inducements to do so, was tortured and then hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn on December 1 on the technical charge of treason, but in reality because of his priesthood.

St. Alexander Briant (1556-1581) was a diocesan priest who entered the Jesuits just before he was executed. He studied at Oxford at Hertford (then Hart Hall) College where he met and became a follower of Robert Parsons at Balliol who later became a Jesuit and slipped into England with Campion. Briant crossed the Channel in August 1577 to attend the English College at Douai where he was reconciled to the Catholic Church. He was ordained in 1578 and in August 1579 returned to his homeland and took up ministry in his native shire (Somerset). He was only able to care for Catholics for two years before priest-hunters caught him by accident.

They searched unsuccessfully for Fr. Persons in one house, and then went to a neighboring house where they discovered Fr. Briant. His captors kept him without food and with little to drink for six days hoping to force information from him about Persons. He refused to speak so he was transferred to the Tower for further interrogation and torture on the rack. He wrote to the English Jesuits about his torture, saying that he kept his mind so firmly set on Christ's Passion that he felt no pain during the torture, only afterwards. He also wrote that just before he was tortured a second time, he had determined to enter the Jesuits if he were released from prison. However, since he doubted that he would be released, he asked to be accepted into the Society. The Jesuits accepted him upon receiving his letter.

St. Alexander Briant had carved a small wooden cross and held it in his hands in the courtroom. When one of the judges took it from him (Why?) he said, "You can take it out of my hands, but not out of my heart." Taking the cross from him seems an act of petty cruelty. I guess when you've tortured a man so much that the man using the rack boasts that the victim will be a foot longer, you'll do just about anything.

St. Ralph Sherwin: Born 1550: Rodsley, Derbyshire. Ralph Sherwin was the nephew of John Woodward, rector of Ingatestone in Essex from 1556 to 1566. In 1568, Sir William Petre of Ingatestone Hall, nominated Ralph to one of eight fellowships he had founded at Exeter College, Oxford; Ralph took his MA there in 1574.

Brought up as a Protestant, Ralph converted to the Catholic faith in 1575, and went to the English college at Douai where he was ordained in 1577. He continued his studies at the English College in Rome, his name being the first in the College register. When an oath requiring students to consent to the English mission was required, Ralph readily agreed, saying, ‘Today rather than tomorrow’.

Ralph returned to England on 1st August 1580, but on 9th November 1580 he was arrested in London and committed to the Marshalsea prison. He was transferred to the Tower of London where he was alternately tortured on the rack and thrown out into the December snow. He was once kept upon the rack for five consecutive days without food. He was offered a bishopric if he would conform to the authorised religion, but refused.

On 20th November 1581, Ralph was tried at Westminster Hall, accused of treason. He wrote a letter to his uncle, John Woodward, saying, "Innocency is my only comfort against all the forged villainy which is fathered on my fellow priests and me." His last words were: "Jesu, Jesu, Jesu, esto mihi Jesus!" "Jesus, Jesus, Jesus, be to me Jesus (Saviour)".

When they were found guilty, St. Edmund Campion told the judges: "In condemning us you condemn all your own ancesters--all the ancient priests, bishops, and kings--all that was once the glory of England, the island of saints, and the most devoted child of the See of Peter. For what have we taught, however you may qualify it with the odious name of treason, that they did not uniformly teach? To be condemned with these lights--not of England only, but of the world--by their degenerate descendants, is both gladness and glory to us."

Upon hearing the sentence of death, the three sang "Te Deum Laudamus".

At Tyburn Tree, St. Alexander Briant watched the brutal execution meted out to those found guilty of treason inflicted on Sherwin and Campion. It's hard to imagine the fortitude and faith necessary to witness such horrors and know that in a moment, you will endure the same--at least humanly speaking. Only the theological virtues of faith, hope and love grants that kind of strength.

These three holy men were canonized by Pope Paul VI among the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales in 1970.

Published on November 30, 2013 22:30

November 29, 2013

The Feast of St. Andrew in 1554: A Holy Day of Reconciliation in England

On November 30, 1554, Reginald Cardinal Pole, the Papal Legate, soon to be Archbishop of Canterbury, received the submission of the English Parliament and granted absolution to the entire kingdom, reconclining England to the Holy See and the universal Catholic Church. As both Alison Weir and H.F.M. Prescott comment in their biographies of Mary I, the first Queen Regnant of England and Ireland, this must have been one of the happiest days of her life as she witnessed this solemn act. She was married to Philip of Spain, her cousin had returned, Parliament and Convocation were both repenting of the acts led by her father and her half-brother to separate England from the Catholic Church--and she believed she was pregnant (as her doctors had told her).

For this day to occur, several things had to be arranged and decided. First of all, for the Papal Legate to arrive in England, the Act of Attainder against Reginald Pole had to be removed by Parliament. This was the Act that condemned his mother Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, and many others to death. Parliament lifted this sentence of death and Mary invited the Papal Legate to return from exile on November 20, 1554. He would be the first Papal Legate present in England since the trial of her mother's marriage in 1529--when Katherine of Aragon appeared before Cardinal Campeggio and Cardinal Wolsey, appealed to Henry her husband and left the Court, impervious to pleas to return. The matter of former Church lands also had to be decided: Henry VIII and then Edward VI had seized the monasteries and then the chantries and the chantry schools, destroyed most of them, sold or given the lands to courtiers and others who benefitted. Were these all to be given back?

The Papal Legate wanted them back, but Mary was more concerned about alienating the Court and nobility her reign had so lately unified against the plots of Northumberland to replace her in the succession with Lady Jane Grey and that of Thomas Wyatt the younger to prevent the Spanish marriage and place her half-sister Elizabeth and young Edward Courtenay on the throne. So the lands and property stayed with their current owners.

On November 28 Cardinal Pole spoke to Parliament and asked them to repeal all the other acts that were obstacles to reunion. On November 29 Parliament did so and then petitioned Queen Mary to intercede with the Papal Legate for absolution and reunion with Rome (two members refused to sign the petition).

Then on St. Andrew's Day Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester and Mary's Chancellor, led the members of both houses of Parliament to kneel before the Papal Legate and Mary, presenting the petition. The petition proclaimed that Parliament was "very sorry and repentant of the schism and disobedience committed in this realm against the See Apostolic" and begged to be returned "into the bosom and unity of Christ's Church."

Cardinal Pole then welcomed "the return of the lost sheep" and granted absolution to the entire kingdom, proclaiming a new Holy Day on November 30: the Feast of Reconciliation. Unfortunately, Cardinal Pole and Mary I would have only three celebrations of this Feast (in 1555, 1556, and 1557)--both died on November 17, 1558, as the Once I Was a Clever Boy blog recounts. This year marks the 455th anniversary of their deaths.

For this day to occur, several things had to be arranged and decided. First of all, for the Papal Legate to arrive in England, the Act of Attainder against Reginald Pole had to be removed by Parliament. This was the Act that condemned his mother Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, and many others to death. Parliament lifted this sentence of death and Mary invited the Papal Legate to return from exile on November 20, 1554. He would be the first Papal Legate present in England since the trial of her mother's marriage in 1529--when Katherine of Aragon appeared before Cardinal Campeggio and Cardinal Wolsey, appealed to Henry her husband and left the Court, impervious to pleas to return. The matter of former Church lands also had to be decided: Henry VIII and then Edward VI had seized the monasteries and then the chantries and the chantry schools, destroyed most of them, sold or given the lands to courtiers and others who benefitted. Were these all to be given back?

The Papal Legate wanted them back, but Mary was more concerned about alienating the Court and nobility her reign had so lately unified against the plots of Northumberland to replace her in the succession with Lady Jane Grey and that of Thomas Wyatt the younger to prevent the Spanish marriage and place her half-sister Elizabeth and young Edward Courtenay on the throne. So the lands and property stayed with their current owners.

On November 28 Cardinal Pole spoke to Parliament and asked them to repeal all the other acts that were obstacles to reunion. On November 29 Parliament did so and then petitioned Queen Mary to intercede with the Papal Legate for absolution and reunion with Rome (two members refused to sign the petition).

Then on St. Andrew's Day Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester and Mary's Chancellor, led the members of both houses of Parliament to kneel before the Papal Legate and Mary, presenting the petition. The petition proclaimed that Parliament was "very sorry and repentant of the schism and disobedience committed in this realm against the See Apostolic" and begged to be returned "into the bosom and unity of Christ's Church."

Cardinal Pole then welcomed "the return of the lost sheep" and granted absolution to the entire kingdom, proclaiming a new Holy Day on November 30: the Feast of Reconciliation. Unfortunately, Cardinal Pole and Mary I would have only three celebrations of this Feast (in 1555, 1556, and 1557)--both died on November 17, 1558, as the Once I Was a Clever Boy blog recounts. This year marks the 455th anniversary of their deaths.

Published on November 29, 2013 22:30

November 28, 2013

Culture and Abortion: Review in Homiletic & Pastoral Review

If you like, you may read my review of Culture and Abortion by Edward Short on the Homiletic & Pastoral Review site. You might remember that Mr. Short is also writing a trilogy on Blessed John Henry Newman:

Newman and His Contemporaries

; Newman and His Family; Newman and His Critics. I wrote the review of Culture and Abortion in August, just after Eydie Gorme died, and worked that circumstance in the review to make my point about the importance of what Short wanted to achieve in this book:

If you like, you may read my review of Culture and Abortion by Edward Short on the Homiletic & Pastoral Review site. You might remember that Mr. Short is also writing a trilogy on Blessed John Henry Newman:

Newman and His Contemporaries

; Newman and His Family; Newman and His Critics. I wrote the review of Culture and Abortion in August, just after Eydie Gorme died, and worked that circumstance in the review to make my point about the importance of what Short wanted to achieve in this book:CULTURE AND ABORTION. By Edward Short. (Gracewing, LTD., Herefordshire, England 2013) ISBN: 978 085244 820 5. 308 pages; $22.46.

The big band, pop, and Latin singer Eydie Gorme, wife of Steve Lawrence, half of “Steve and Eydie,” died in August 2013. Some of my online friends posted videos of her singing some standards. One comment drew my attention–and response. The gist of the comment was that “we face too many dangers today to waste time enjoying this lady’s singing; you need to be talking to us about the challenges we face. We need to be lamenting and groaning in this valley of tears, not taking such useless pleasure.” My response was something like, “Remember the Catholic AND: we can do both. We can pray and prepare for whatever challenges may come our way AND enjoy Eydie Gorme’s talent and beauty. Finding pleasure in her songs does not diminish our concern for the state of the world—in fact, it’s a sign of the love we have for God’s creation.”

I’d say the same about this volume of essays from Edward Short: he demonstrates how in the midst of this valley of tears, in a culture obviously heading in the wrong direction in so many ways—in fact, toward a culture of death and destruction for humanity—we see all around us signs of the culture of life. He finds them in literature, in great men’s lives, in religious orders, in reform efforts, in Papal documents, and in the most unexpected places—and at the same time Short reminds us of the facts of our situation. In the spirit of the Gorme poster, some might say that we have to dedicate ourselves to political and social action to address these issues; that we don’t have time to read poetry and prose; but Short presents them with the Catholic AND. We do have time and we should make time.

Read the rest here. I'll be writing more reviews for Homiletic & Pastoral Review, as Father Meconi sent me a nice box of books that arrived earlier this week!

By the way, that's Lady Macbeth on the cover, failing to wash the blood from her little white hands.

Published on November 28, 2013 22:30

How Hans Holbein Survived at Henry VIII's Court

Historical novelist Nancy Bilyeau describes Hans Holbein's career at Henry VIII's Court and how he survived painting the great portrait of Thomas More (perhaps residing in More's home in Chelsea) and painting the perhaps over flattering portrait of Anne of Cleves. Holbein had some trouble finding the right patrons and portrait subjects--Anne Boleyn was a patron for a time (she lost her head) and Thomas Cromwell was another protrait subject (and he lost his head). Another fascinating story about Henry VIII's Court.

I am curious about what happened to the portrait of More after the fall and execution of Thomas More: did Margaret Roper take the painting with her to the Continent? This site includes a great analysis of the painting, which is now in the Frick Collection, New York City, NY.

By the way, this site has a portrait from the studio of Hans Holbein of More's second wife Alice.

Published on November 28, 2013 22:30