Aaron Ross Powell's Blog, page 14

January 26, 2016

Stupidity, Immorality, and Political Differences

We treat people’s political beliefs as indicative of their character or competence, but that’s often a mistake.

Too often in political debate, we assume the absolute veracity of our empirical beliefs. We know that private schools fail to serve the underprivileged, or that immigrants take jobs, or that trade deficits harm the working class.

We admit no possibility that we might not have enough information to justify our views or that conceptual framework we employ to interpret evidence might have imperfections. Furthermore, we tend to think that our views aren’t just correct, but obviously correct. It’s not that the data is murky, but we’ve managed to get the right read on it. No, the data is clear as day, and the interpretive framework we employ self-evident. And if the data is that clear, then there must be something wrong with those who don’t see it. Since private schools are so obviously inadequate, we think, then those who want private schools must want inadequate schools.

Too often, this is how we evaluate the policy proposals of our political adversaries. Because the evidence supporting our preferred policies is obvious, and because the way we interpret that evidence self-evident, we tend not to see differences of political opinion stemming from good faith disagreement about the underlying facts or how best to interpret them. Instead, we see differing political opinion as the result of explicit desires to work against the goals of our preferred policies.

Say we believe that Policy A, which we support, will lead to good Result X. We encounter someone who instead advocates for Policy B. Because of our certainty about the evidence and how to interpret it, too many of us too often see that person’s support for Policy B coming not from a good faith and reasoned belief that Policy B is a better way to get to Result X. Because if what we believe is both correct and obvious, then the advocate of Policy B must know that it will undermine the achievement of X. And if X is a good result, then this person doesn’t just disagree with us, but actively wants something bad to happen.

Unfortunately, this all-too-common way of thinking about political debate leads to serious problems, because it means that our empirical beliefs are essentially closed to critique unless that critique comes from someone who already shares our policy preferences. If our interlocutor doesn’t share our policy preferences, then before the conversation can get off the ground, we’ve already decided he is either stupid (he’s too dumb to see his error) or immoral (he maliciously prefers evil outcomes). But, of course, if our empirical priors or interpretive framework are wrong, then someone with better priors will likely come to a different policy conclusion.

Thus individual policy preferences exist as a signal of their holder’s intelligence or moral worth — and a challenge to one’s policy preferences gets interpreted as an attack on the holder’s smarts or basic goodness. Because we believe that certain policy preferences signal moral worth, we adopt our policy preferences based on how we would like to be perceived. And we hold to those policies regardless of their actual, real-world outcomes, or pay so little attention to their outcomes that we never feel the need to revise our political preferences.

Alternatively, we could just assume that people we disagree with differ from us because they’ve read the data one way, while we read it another, and yet both of us are operating in good faith and are reasonable people. This is clearly not the case in every instance of disagreement, yet treating disagreement this way is a pretty good way to go about political debate. Assume the best of your opponent unless you have strong reason to do otherwise.

Let’s say you and I differ on education policy. You’re a strong supporter of public schools, while I think we ought to switch to a system of publicly-financed private schools. It’s possible that I support private schools because I’m either stupid (the evidence is clear, but I’m too dumb to see it) or I’m immoral (I don’t care about poor kids getting a quality education, and so am happy to see only the rich become educated). It’s also possible, however, that I instead want to see everyone, rich and poor, get a quality education, but believe, after careful consideration, that the evidence supports private schools and school choice as the best way to achieve that. I could be wrong about that evidence, of course, but so could you. Debating that is bound to be more fruitful than simply condemning each other as benighted.

We need to be careful, however. Because there is a moral element to politics, and that means we shouldn’t take the above as an argument against seeing any moral angle to political differences. There are policy preferences that are immoral and reflect poorly on the moral quality of those who hold them. We should call those out when we see them. Some policy preferences actually do aim at immoral goals, and some depend on arguments and evidence so blindingly bad that to hold on to them evinces a morally blameworthy level of ignorance. We can see Jim Crow was an example of the former, while anti-GMO policies fall within the latter.

The difference between that sort of moral judgment, however, and the kind I’m challenging is where morals enter. We can begin with moral judgments and derive our politics from there. We can say, for example, that it’s morally wrong to lock people in cages because they exhibit non-violent behavior we find off-putting, and conclude policies based on the belief that such a thing is acceptable are wrong, and that people who prefer those policies are open to moral critique. Likewise with policies motivated by other immoralities, such as collectivism and nationalism.

That’s the kind of moral judgment we ought to be making in politics. Unfortunately, too much of what passes for moral judgment is just a feather-ruffling means to inoculate one’s ill-considered beliefs against reasonable criticism. The line between the two can be difficult — and personally painful — to draw, but it’s safe to say that most of what passes for morality in political discourse falls on the wrong side of it.

This essay originally appeared on Libertarianism.org .

Stupidity, Immorality, and Political Differences was originally published in Aaron Ross Powell’s Homepage on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

January 21, 2016

Free Thoughts Episode 118: Ben Powell

Everybody hates sweatshops. Except the people who work there because the alternatives are even worse.

That’s what we talk about on this week’s episode of Free Thoughts, and we’re joined by Ben Powell. He’s director of the Free Market Institute at Texas Tech University and a professor of economics at the Rawls College of Business. He’s the author of Out of Poverty: Sweatshops in the Global Economy.

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/cdn.cato.org/libertarianismdotorg/freethoughts/FreeThoughts_118.mp3

January 19, 2016

Political Disagreement over Facts vs. Morals

Too often in political debate, we assume the absolute veracity of our empirical beliefs. There’s no possibility that we might not have enough information to justify our views or that our interpretive framework might have imperfections. Furthermore, because our views are both correct and seem obviously correct to us, they must also be obviously correct to others.

From that bedrock of certainty, we then evaluate policy proposals different from our own to be a product not of differing, but good faith, empirical views or interpretive frameworks, held by reasonable people, but as explicit desires to work against the goals of our preferred policies. Thus if we believe that Policy A will lead to Result X, then anyone who prefers Policy B does so not because they believe in good faith and after reasonable study that Policy B is a better way to get to Result X, but that they instead know or by any reasonable standard ought to know that Policy B will undermine the achievement of X—or more likely specifically desire to undermine X.

This leads to serious problems, because it means that our empirical beliefs aren’t open to critique, unless that critique comes from someone who already shares our policy preferences. Because if our interlocutor doesn’t share our policy preferences, then before the conversation can get off the ground, we’ve already decided he is either stupid or immoral. But, of course, if our empirical priors or interpretive framework are wrong, then someone with the right (or at least more right) priors will likely come to a different policy conclusion.

The result is politics not as an attempt to improve the state of the world but instead as moral posturing. We believe that certain policy preferences signal moral worth, and so adopt our policy preferences based on how the people we want to appear moral to will judge us.

Rectifying this does not mean abandoning morality in politics or ceasing to judge the moral character of our political opponents in any capacity. Because there are policy preferences that are immoral and reflect poorly on the moral quality of those who hold them. We should call those out when we see them.

The difference between that sort of moral judgment, however, and the kind I outlined above is where morals enter. We can begin with moral judgements and derive our politics from there. We can say, for example, that locking people in cages because they exhibit non-violent behavior we find off-putting is morally wrong, and so policies based on the belief that such thing is acceptable are wrong, and that people who prefer those policies are open to moral critique. Likewise with policies motivated by other immoralities, such as collectivism and nationalism.

That’s the kind of moral judgment we ought to be making in politics. Unfortunately, too much of what passes for moral judgment is just feather ruffling and an attempt to inoculate one’s ill-considered beliefs against reasonable critique. The line between the two can be difficult—and personally painful—to draw, but it’s safe to say that most of what passes for morality in political discourse falls on the wrong side of it.

December 21, 2015

Thoughts on THE FORCE AWAKENS

Star Wars: The Force Awakens did was it needed to. It restarted the franchise after Lucas’s disastrous prequel turn. It stamped Star Wars as Disney’s in the same way Iron Man did with Marvel. We weren’t just picking up where we left off, but rebooting a bit, too–and that’s fine. It’s what had to happen.

I enjoyed the movie immensely, and not just because I got to take my six year old daughter for her first experience of Star Wars on the big screen. (She loved it.)

What follows isn’t a composed review. I’ll need to see it a few more times for that. Instead, it’s more a random set of things that occurred to me during the movie and after. I’ve avoided spoilers, too.

*

My daughter’s a Star Wars Rebels fan and her favorite character is Sabine. Still is. But Rey’s edging in. I never really understood how bad the movie business (and the publishing business and the television business) is at giving girls action heroes to root for until I had a daughter. Now I can’t escape it. It’s a constant struggle finding something to show her or read to her that has a female protagonist who isn’t a princess or school girl obsessed with boys or isn’t focused on teaching how to be nice or how to get along with friends.

Rey’s exactly what Star Wars needed. A girl who kicks ass and isn’t a princesses and–unlike Sabine–gets top billing. When we left the theater, Nora said, “I want to be Rey for Halloween.”

*

I was always optimistic about this movie. Leading up to it, all the signs pointed in the right direction, and all the new Star Wars stuff Disney gave us was pretty damn good. Star Wars Rebels was easily the best new Star Wars on a screen since Return of the Jedi. The new comics capture the feel of the good Star Wars movies. It was clear Disney saw the Rebellion Era as the “default,” and would use it to inform the look and feel of future material.

And we were going to see a return to practical effects. Which goddamn did we need, after the bad (and not just dated) CGI of the prequels. For the most part, The Force Awakens succeeds here. The aliens in its version of the Cantina sequence look great.

But–and here’s my turn toward complaining–the large creature work failed. The creatures moved like stage productions, where you admire the artistry while still seeing clearly that it’s a few guys in a suit. None lived up to the standard Jabba set 30 years ago. You could watch the costumes crinkle around the knees, and the stilts inside as they walked. In fact, I’d say that both the big creatures (the one Rey runs across in the desert when she finds BB-8 and the one Finn shares a watering hole with) are far less convincing as living animals than, say, Jurassic Park two decades ago.

Maybe in the era of computer imagery for everything, large-scale practical creature effects is a lost art.

*

Now the oddest thing about the movie, and something that bugged me from the opening scene. Nearly ever shot with people in it felt compressed. Like everything happening was in a small area in the middle of empty space. Especially when the action took place outside, I got a distinct impression of watching a filmed stage production. Everything felt crisp, and constructed, and right there in front of you, because, unlike with the prequels, it all was.

The original trilogy, this made come off as a lived in universe. The Force Awakens too frequently looked like a built universe. Almost as if it were a very high budget fan film.

*

Which leads to my biggest complaint about the movie. As bad as they were, the prequels gave a strong sense of a universe. What we saw in the camera’s frame was but a piece of a much larger place, with events happening we weren’t being shown. It felt like stuff was happening off frame.

The Force Awakens (consciously?) returned to the style of A New Hope, with little indication that there was a universe out there. This worked for the first Star Wars. But I think it did because that movie oriented us. We could extrapolate from the little it gave us. There’s a galactic empire that controls basically everything. So what we’re not seeing is probably controlled by them. There’s a Rebellion that’s small and scrappy. What we see of it is close to all there is.

The Force Awakens plays the same game. Except, shouldn’t the roles be reversed? The Rebellion won and we’re told there’s a Republic now. But all we see of that Republic is a small and scrappy band of freedom fighters, with only a handful of X-Wings, and a single shot of people standing on a balcony in a city on an unknown world. The First Order, on the other hand, is supposed to be a remnant of the Empire, because we’re told it is. But what we see is a dominant organization with access to countless ships and soldiers, an organization that certainly appears to have near total control over the area of space the movie happens in. So while A New Hope showed us only a tiny portion of its universe, we had not trouble imagining the rest. The Force Awakens shows us only a tiny portion of its universe, but what we see conflicts with what we’re lead to believe about the rest.

I know the details will get filled in by novels and comics, but sitting in the theater, I found myself thinking more than once, “I don’t get this setting.”

*

I loved the color. No orange and teal. The effect was to make the movie feel older than it is, like a throwback. Which I’m sure was intentional. Though in ten years, it’ll make the movie feel more contemporary than contemporary movies now, as the orange and teal look will make those films look dated.

*

The movie was too short. Important events–or important explanations for important events–were very clearly cut in post. I hope that someday we’ll get a Peter Jackson style extended cut, adding an hour or more of footage. It’ll be a better movie for it.

*

Setting aside what I said about the confused world-building, I don’t mind at all the in medias res nature of the story. It enunciated the clean break from Lucas’s Star Wars. This is Disney’s franchise now. They’ll go good places with it.

*

Yes, it repeated many of A New Hope’s story beats. Some worked, others didn’t, and still others could’ve been taken away entirely and not missed at all. This shared skeleton seems to be the biggest gripe people have with the new movie. But I guess it didn’t bother me. I took it as Disney building a new franchise out of the corpse of the old, and doing it by going back to where this all started. Star Wars has always been packed with repeated beats. The ones in The Force Awakens worked fine.

*

I still can’t believe we’re going to get new Star Wars every Christmas.

November 3, 2015

Star Wars: Lost Stars – A terrific Star Wars story dragged down by unfortunate YA-ness

Claudia Gray’s Star Wars: Lost Stars caps off my reading of the five novels in the Journey to Star Wars: The Force Awakens series. On the whole, they’ve been quite good—and much better than the old EU stuff. Part of that, I’m sure, is their canon-ness. These books—and I know this is silly—are about what actually happened in the Star Wars universe. The EU, on the other hand, always had a whiff of fan fiction.

Gray’s novel is, on the one hand, a terrific look at the events of the three movies (plus a few years more) from a different and fun direction. But, I really wish it hadn’t been YA. Or rather, I wish it hadn’t been YA romance.

This is, I’ll admit, the first YA “boy-and-girl-fall-for-each-other-and-run-into-troubles” book I’ve read. Though I take it that genre’s kind of a thing among a pretty big set of readers. (Twilight and all the other supernatural romances fall into this category, I guess?) But, so far as I can tell, what it meant in practice is that we got basically a war story with a bunch of teen drama and teen romance shoehorned in, both of which were at best boring.

And, while the events of the novel were a ton of fun to read about, the two main characters, Thane and Ciena, were so totally flat, so totally without interesting features, that I didn’t care a jot about their budding love or tortured loyalties. Maybe that’s a romance thing. That you want the readers to be able to imagine themselves as one of the two leads, as so you have to make them sort of empty vessels and totally non-threatening, so there’s nothing where the reader’s like, “Oh, I don’t want to imagine myself as thatguy or girl.” For someone who didn’t find the drama/romance compelling, though, the flatness leaves the characters feeling, well, flat.

But, anyway, that aside, I quite enjoyed Lost Stars. Seeing how Imperials reacted to things like the destruction of Alderaan and then of the first Death Star was pretty neat. As was the Battle of Jakku.

I just wish it hadn’t been a novel about kids acting and talking like really bland kids.

October 8, 2015

Politics is Destroying Your Soul

Politics doesn’t just make the world around us worse. It makes us worse, as well.

Politics is nothing to be proud of. We shouldn’t believe in it, shouldn’t get excited about it. Shouldn’t think it’s noble or, worse, fun. On a good day, politics is a silly game with negative externalities. A waste of countless hours and countless minds — hours and minds that could’ve gone to productive, radical, world-changing, and life-improving pursuits. Politics, on a good day, is lost opportunities. On a bad day, it’s livelihoods and sometimes lives destroyed. It’s violence and ignorance and fear.

Strong words demand definitions, though. So what do I mean by “politics?” I mean the act of deciding for others via the mechanisms of the state. Choosing for others, and then getting government to make them go along with our choices. Granted, when we make decisions via those mechanisms — by, say, voting — we expect the outcome will apply to ourselves and not just to other people. But it’s misleading to say we are “deciding for ourselves” when we vote, because if what we vote for is something we would’ve done anyway, we could always choose to do it independent of a vote. If I think contributing money to a cause is worthwhile, I don’t need the state to make me do it. I can cut a check any time. By voting, by shifting from the personal and voluntary to the political and compulsory, we call for the application of force. A vote is the majority compelling the minority to comply with the majority’s wishes. Thus politics is a method of decision-making where choices are moved from individuals choosing privately to groups choosing collectively, and where the decisions those groups arrive at are backed by law and regulation. It’s this last aspect — the backing by the force of law — that distinguishes politics from, say, five friends voting on where to go for dinner.

Most of us have at least a sense there’s something wrong with politics. Watch cable news, listen to talk radio, sit through weeks or months of campaign ads, and it’s impossible to avoid the unseemliness of political practice. It’s off-putting and makes us, or ought to make us, question the character of anyone enthusiastic about it. But its pernicious influence extends beyond those who embrace politics as a vocation or hobby. Politics represents a corrupting influence in all our lives, a stumbling block in our paths toward living well. No matter how minimal our participation.

Politics accomplishes this by undermining our ability to practice well the art of good living. One way is indirect: politics contributes to an environment where learning the skill of living well becomes more difficult than it would be otherwise. An important prerequisite to living well is a certain amount of material security — if we’re just scraping by, we have no time for higher pursuits. We’re used to common libertarian claims, grounded in economics, that a system where decisions are made politically — whether through the democratic process or by legislators and bureaucrats instead of by individuals — will lead to less wealth and innovation, and thus give us fewer resources to lead the kinds of lives we would decide to lead in a world of choice and plenty. In this way, a politically controlled environment becomes less compatible with maximally good lives.

But politics doesn’t just make the world around us worse. It makes us worse, as well. When we participate in politics — by seeking office, by voting — we take part in a system where we attempt to decide for others while they attempt to decide for us, and where those decisions, whoever makes them, are backed by violence or, at the very least, the threat of violence. It’s a system where the participants say to each other, “I know what’s best for you, you need to do what I say, and if you don’t, these men with guns will threaten you or take your money or lock you in a cage or kill you.” Such a system encourages us to deal with each other in ways beneath the standards of behavior we ought to reach for, and it encourages us to see each other not as friends and companions and fellow seekers of the good life, but as enemies and rivals and obstacles in the way of finding happiness.

Politics inculcates pettiness, short-sightedness, Manichean thinking, tribal feuds, selfishness, and rage. It discourages reason and respect and a basic appreciation of the dignity of others, especially those who seek lives different from our own. It makes us less likely to find virtuous mentors or learn from the virtuous actions of others, because everyone we encounter will themselves suffer from its corrosive influence. Politics encourages extreme reactions instead of careful seeking of the proper, measured response. Politics distances decisions from local knowledge and so limits moral wisdom by making it less likely we will act to bring about virtuous outcomes even when motivated by virtuous impulses.

Politics is, at best, a blunt instrument, though perhaps an occasionally necessary one. But its use has costs, including, I believe, degradation of our character. We should resort to politics only when we have no other options, and then only reluctantly. At the very least, it should never be cause for celebration or held up as the ideal of civic virtue. In short, politics makes us worse. We’d be better people without it. Better off if we rejected the political as a means to flex our will in the world and instead made more effort to live up to our potential as rational, discoursive beings. The good life is not the life of politics and politics is, at a fundamental level, incompatible with the good life.

This story originally appeared on Libertarianism.org .

Politics is Destroying Your Soul was originally published in Aaron Ross Powell’s Homepage on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Let he who is without dumb beliefs be the first to laugh at Xenu

Watched HBO’s Going Clear last night. A powerful and infuriating documentary.

But here’s the thing: At several points in the movie, we shift from being told about the horrors of the organization’s practices to the silliness of many of its beliefs. Particularly the scene where Paul Haggis learns about Xenu and the interstellar DC-8s. I mean, it’s crazy, right? Who could believe such nutty stuff?

I want to urge caution when giggling at the odd Scientology creation myth and other related weirdness. While the organization does awful things, the content of its beliefs is really no more silly than the stuff present in pretty much every major religion. Rising from the dead? Water into wine? Devils controlling our minds? A trip from Mecca to Jerusalem on a flying horse? Talking bushes?

The only difference with Scientology, the only thing that makes it so okay to laugh at, is its lack of distance. Hubbard invented this stuff just decades ago, instead of centuries or millennia. Thus it’s very clear that it was invented. But so was all the rest of it. We just don’t have records of it.

So if you’re religious, chances are you believe things just as silly to the non-believer as the stuff in Going Clear. (And even if you’re non-religious, chances are you have all sorts of unfounded, silly beliefs. We all do. They’re just of a different category.)

Which is all just a long way of saying, “Be nice.” Or, at least, be a little self-aware when poking fun.

This post originally appeared on my website . If you liked it, please consider joining my very-low-volume mailing list .

Let he who is without dumb beliefs be the first to laugh at Xenu was originally published in Aaron Ross Powell’s Homepage on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

April 22, 2015

The Hard Part’s the Story

You get to a point in the initial stages of a story where it kind of clicks. Where the plot shifts from a vague idea and a series of “What next?” questions to a big picture with all its edges defined.

That’s where I am—finally!—with the new novella/novel. I have notes for every scene through the end, they all add up to something pretty much makes sense, and quite a lot of those scenes are either done or in pretty good shape. It’s looking like this thing will run 20 or 30 thousand words. So shorter than a novel but longer than a short story. A novella. But we’ll see. The story’s a mystery, with a bit of magic and a lot of weirdness, and prose I’m rather digging.

All I’m really missing now is a title. Which is weird because those are usually the first thing to come to me. Working title’s Mr. V, and I don’t like that much.

Animus Audiobook Promo Codes

The audiobook version of Animus, my short story collection, is now widely available. And I still have quite a few promo codes for it. So if you up for leaving a review on Amazon and Audible, send me an email and I’ll give you a code to get a free copy.

For what it’s worth, the last story in the collection introduces the main character of the probably-getting-a-new-title Mr. V.

Patreon

I’ve setup a Patreon page for my writing. If you’re pretty sure you’ll want to read Mr. V and whatever books I release after that, signing up’s a great way to support future stories while effectively pre-ordering them at $2 a pop, less than it’ll cost to buy them on the Kindle. And you don’t pay anything until I actually release something. If I get enough supporters, it’ll let me do cool stuff, like have professional audiobook narration done for each, or get them into print in addition to ebook releases. Give it a look.

March 31, 2015

Let he who is without dumb beliefs be the first to laugh at Xenu

Watched HBO’s Going Clear last night. A powerful and infuriating documentary.

But here’s the thing: At several points in the movie, we shift from being told about the horrors of the organization’s practices to the silliness of many of its beliefs. Particularly the scene where Paul Haggis learns about Xenu and the interstellar DC-8s. I mean, it’s crazy, right? Who could believe such nutty stuff?

I want to urge caution when giggling at the odd Scientology creation myth and other related weirdness. While the organization does awful things, the content of its beliefs is really no more silly than the stuff present in pretty much every major religion. Rising from the dead? Water into wine? Devils controlling our minds? A trip from Mecca to Jerusalem on a flying horse? Talking bushes?

The only difference with Scientology, the only thing that makes it so okay to laugh at, is its lack of distance. Hubbard invented this stuff just decades ago, instead of centuries or millennia. Thus it’s very clear that it was invented. But so was all the rest of it. We just don’t have records of it.

So if you’re religious, chances are you believe things just as silly to the non-believer as the stuff in Going Clear. (And even if you’re non-religious, chances are you have all sorts of unfounded, silly beliefs. We all do. They’re just of a different category.)

Which is all just a long way of saying, “Be nice.” Or, at least, be a little self-aware when poking fun.

March 18, 2015

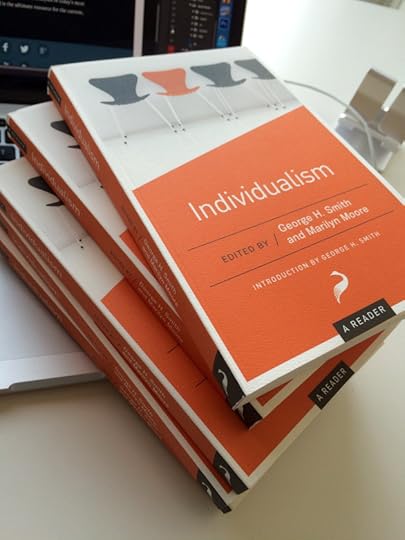

Individualism: A Reader

I’m happy to announce the first book in the new Libertarianism.org Readers series, Individualism: A Reader, edited by George H. Smith and Marilyn Moore. I’m series editor on these and there are already quite a few more Readers planned.

Individualism is one of most criticized and least understood ideas in social and political thought. Is individualism the ability to act independently amidst a web of social forces? A vital element of personal liberty and a shield against conformity? Does it lead to or away from unifying individuals with communities?

Individualism: A Reader provides a wealth of illuminating essays from the 17th to the early 20th centuries. In 26 selections from 25 writers individualism is explained and defended, often from unusual perspectives. This anthology includes not only selections from well-known writers, but also many lesser-known pieces–reprinted here for the first time–by philosophers, social theorists, and economists who have been overlooked in standard accounts of individualism.

The depth and complexity of ideas about individualism are reflected in the six sections in this collection. The first examines individuality generally, with the following five detailing social, moral, political, religious, and economic individualism. Throughout, individualism is analyzed and defended through the lenses of classical liberalism, free-market libertarianism, individual anarchism, voluntary socialism, religious individualism, abolitionism, free thought, and radical feminism.

Both richly historical and sharply contemporary, Individualism: A Reader provides a multitude of perspectives and insights on personal liberty and the history of freedom.

The book officially comes out on April 7, but you can preorder it now at Amazon. Kindle and audiobook editions will be available soon.

Aaron Ross Powell's Blog

- Aaron Ross Powell's profile

- 18 followers