Aaron Ross Powell's Blog, page 15

March 2, 2015

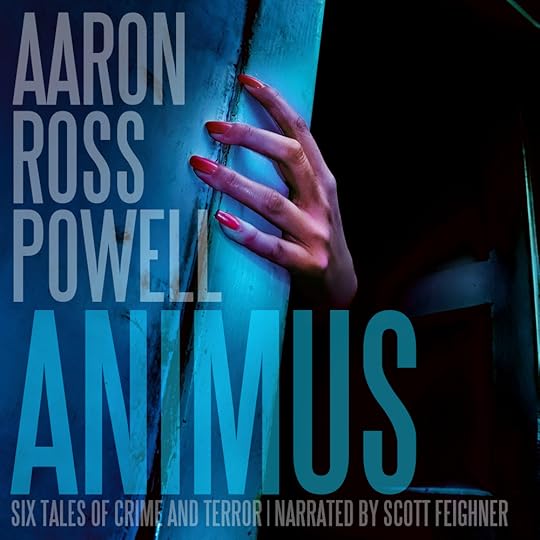

Animus is now an audiobook.

My short story collection, Animus: Six Tales of Crime and Terror, is now an audiobook, narrated wonderfully by Scott F. Feighner. Scott did an incredible job of giving the characters life, and managed to make me sound like a much better writer than I am. Which is everything you could wish for in a narrator.

The book’s available on Audible, Amazon, and iTunes. You can get for free from Audible if you sign up for their trial membership, which includes one book of your choice.

And if you’ve read or listened to the book and feel like leaving a review on one of those sites, I’d really appreciate it.

Thanks and enjoy!

February 19, 2015

James Ellroy’s Perfidia: Mid-tier from the best there is.

Up front, Perfidia is a James Ellroy murder mystery set in Los Angeles in the 1940s. It’s big, complex, mean, and ugly in all the ways that make Ellroy the best crime writer alive today, and probably the best crime writer there’s ever been.

But it’s not a perfect book, not like L.A. Confidential, White Jazz, and American Tabloid. Still, even imperfect Ellroy’s a whole hell of a lot better than just about anything else.

Beginning with The Black Dahlia in 1987 and continuing through the rest of the L.A. Quartet and then the American Underworld trilogy, Ellroy’s novels have advanced chronologically through a secret history of America, from 1947 and the most famous murder in L.A. history—though perhaps eclipsed by the O.J. Simpson killings—through the assassinations of JFK, RFK, and MLK. With Perfidia, he begins a second L.A. Quartet, this one set during World War II and kicking off with the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

On the one hand, this is great. Nobody writes mid-century L.A. like Ellroy. But it also means he’s filling in the backstory of the characters who populated those prior seven books—and I’m just not convinced he pulls it off. Granted, it’s be a while since I read the first L.A. Quartet, but my sense is the events of Perfidia don’t jibe with the way those characters think and behave in their later appearances. There’s also an attempt to shoehorn relationships that needn’t exist. One such example—and I chose it because it’s made clear early in the book and so isn’t a spoiler, and is particularly egregious—is the discovery that Elizabeth Short, the Black Dahlia herself, is in fact the daughter of Dudley Smith, the arch villain of, and arguably best character in, Ellroy’s corpus. It’s silly and unnecessary, and makes this carefully constructed world Ellroy’s built over his career suddenly seem too neat and too, well, constructed.

A second issue I had with Perfidia is the writing itself. Ellroy’s never satisfied with his prose, and his evolving style sets him apart from other writers in the genre. Every new Ellroy book features his voice, but often in radically new garb.

Perfidia sticks with late-Ellroy style, which is too bad. We can divide Ellroy’s prose into three periods. The first covers his early novels through The Big Nowhere. Here, Ellroy was writing conventional prose, albeit high quality conventional prose, which got better with each new novel. But then something happened with L.A. Confidential. I asked him about this year ago at an author signing. What he told me was that the manuscript for that book ran long. Really, really long. His publisher said, “This is great, but you need to cut it in half.” L.A. Confidential has a famously dense plot. You can’t really pull any events from it. So Ellroy instead pulled words. He slashed every word that wasn’t necessary to convey the meaning of each sentence. The result is some of the most dazzling prose in the English language.

He took this a step further in White Jazz, the most stylistically perfect book I’ve ever read. American Tabloid remained minimal, but wasn’t as out there. The Cold Six Thousand went even more minimal and is probably the low point of Ellroy’s evolving style. He recognized this, recognized that he’d alienated even his fans. Between that book and the final in the American Underworld trilogy, he released a collection of stories, Destination: Morgue!. Here we can see, in exaggerated form, Ellroy’s turn to what I’ll call his “poetry slam” style of prose. Lots of alliteration. Lots of repetition of phrases. Lots of italics. This is prose meant to be read aloud in Ellroy’s voice, the voice he affects for book events and talk shows. It’s the prose he uses in Blood’s a Rover and now in Perfidia. And, compared to the later books of the L.A. Quartet, it’s still hard and beautiful mostly, but it’s also often distracting and sometimes comical.

Then there’s the problem of Ellroy’s women. The murder of his mother when he was a child shapes Ellroy’s life and writing. Anyone who’s read him knows that. He has one memoir on it, and another on how it impacted his relationships with women. Many of his novels deal with his mother’s death in one way or another, none more explicitly than The Black Dahlia, where he metaphorically solves her murder by way of finding Elizabeth Short’s killer. Ellroy’s spent his life chasing women in pursuit of and in reconciliation with one lost woman.

It’s a tragic tale and a tragic psychology, and it’s arguably responsible for a great deal of his novels’ power. But it’s also begun to hurt his fiction. You can see it in Blood’s a Rover and now Perfidia. Women who aren’t minor characters end up as variations of Ellroy’s ideal woman, his vision of a perfect woman. But the problem is perfection allows no variation. There’s only one way to be perfect. And so all Ellroy’s women come off the same. Joan Rosen Klein in Blood’s a Rover is the same woman as Kay Lake and Claire DeHaven in Perfidia. All have Ellroy’s expansive vocabulary. All speak with baroque syntax and possess unrealistically keen psychological insight. Take chunks of dialog or inner monologue from each and they’d be indistinguishable. They’re just not believable as characters. Ellroy’s men have flaws. They live and breathe and make mistakes. They’re noble and nasty. But Joan and Claire and Kate exist like goddesses come down to wade among mortals. They feel detached from the narrative. They break the verisimilitude of Ellroy’s America. I don’t know if, given his past, Ellroy is capable of writing women characters who don’t drown in the tedium of their own perfection. Which is too bad.

I fear I’m coming off as overwhelmingly critical of Perfidia. And I am critical, but only because I know what Ellroy’s capable of. He’s likely the best crime novelist of all time. He’s, in my mind, the best writer, regardless of genre, working today. And among quintessentially Americanauthors—the ones who speak to something deep at the core of the American identity—Ellroy ranks with the best the country’s produced. Nobody understands the ugliness and flirtations with fascism that haunt this country’s greatness like he does. Perfidia is a great book. It’s better than The Black Dahlia, The Cold Six Thousand, and Blood’s a Rover. But it doesn’t reach quite the dizzying heights of The Big Nowhere, L.A. Confidential, White Jazz, and American Tabloid.

Still, if the second L.A. Quartet follows the trajectory of quality seen in the first (a tall order, I know), we’re in for something amazing.M

January 22, 2015

Top 40 Music, Kids These Days, and the Bland Middle

Is popular music today worse than it was when I was a teen in the 90s and was more aware of popular music? Of course! Generational decline is an ironclad law. Millennials are the worst!

On her blog, Libby Jacobson has a nice analysis of this, comparing a Top 40 list from 1996 from one today. She notes that in the 1996 list, “only Alanis Morissette had two songs in the Top 40,” while in today’s list,

Taylor Swift has two songs in the Top 5. Meghan Trainor has two songs in the top 10. Maroon 5: Two songs in Top 20. Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj, Sam Smith, Sia, and Ed Sheeran appear twice in the list. When you include collaborations, Drake, John Newman, Tove Lo and Juicy J also appear multiple times on the list. Not only does pop music all sound the same these days, the mainstream-successful stuff is largely being made by the same people.

She concludes that “pop music is converging both in terms of style/sound and in terms of the talent & personalities producing it” and asks young people to “put down the Taylor Swift and go exploring.”

The thing is, I’m not sure she’s reading the data correctly. Let me offer an alternative take, while admitting that I could be totally off.

I bet if you look at the percent of the music-listening public who listed to/heard/recognized each of the songs on the top 40 lists, you’d fine that it’s declined dramatically between 1996 and today. In other words, the most popular music today isn’t as popular as the most popular music in 1996.

Music has always had call it a “bland middle.” There’s always been a set of bands that are both popular and kind of all sound the same. (I say this as someone who chiefly listens to 90s punk rock, which is quite often utterly interchangeable.) There are people whose taste runs to that bland middle, but there area great deal of people whose tastes don’t.

One thing rather dramatically different about music today from when I was a kid is how easy–and cheap!–it is to access both a lot of it, and a lot of variety. Used to be, I had to save up for a CD, which was around ten or fifteen bucks, and then listen the hell out of it until I had money for another. With Spotify, I can pay that much on a monthly basis to have unlimited access to basically any song there is. This has the effect of dropping the marginal cost of music exploration to zero and making such exploration very easy. Just click around and listen.

Let’s say that among the audience for music, there are 100 “tastes.” There are 100 kinds of music people prefer, with different people ranking those tastes differently. If music is expensive, you’re less likely to try all 100 tastes. Instead, you’ll stick with the ones that you know you like. And if exploration is difficult, you’ll be less likely to even know about all 100 possible tastes, and even within your preferred tastes, you’re likely to only know about the most popular bands because those are the ones everyone else knows about and so are the ones you’ve heard of.

But if music is cheap, you’ll try out more, if not all, of the 100. And within each, you’ll try more bands. (This is made even easier by services like Pandora or Spotify Radio, which let you in effect say, “Here’s my particular taste. Find me things within it I don’t know about.”)

What does this all have to do with the makeup of the Top 40 list? Well, the Top 40 list is a relative ranking of popularity. It’s the most popular stuff at any given time, but it doesn’t tell you how popular that stuff is compared to the most popular stuff from yesterday or years ago.

So my hypothesis is that in 1996, the average number of tastes that had a sizable share of the listening public’s attention and the average number of bands each person listened to within those tastes was lower than today. Today, individual people’s tastes likely diverge more, and within those tastes they likely listen to more variety.

Thus what looks like more variety in the Top 40 in 1996 is actually representative of less variety among the public as a whole. More of those 100 tastes are popular enough to make the Top 40 because people have converged more on a subset of those 100. And what looks like a lack of variety in the Top 40 today is actually representative of more variety among the public as a whole. People are more divergent in their tastes and they’re listening to more bands within those tastes, which means the taste/band combinations that make the Top 40 are those that only slightly edge out all the others people dig. And those are likely to reside in the bland middle.

January 18, 2015

Nobody Likes the Star Wars Prequels and Disney Knows It

One of the striking features of what Disney’s done so far with Star Wars since they took over is the near complete abandoning of the prequel era as not only the default era—as it has been for years—but even as coequal with the Original Trilogy.

Disney appears to recognize what Star Wars fans long have, but Lucas never did: the prequels were failures not just as films and as stories, but as collections of characters and as world-building as well. For people who love Star Wars, the prequels just aren’t Star Wars. Not really, not deep down. And the characters who populate them aren’t interesting enough to carry the franchise—even acknowledging that the Clone Wars wasn’t terrible.

Which is why it’s so freshening to see Disney say—with the new films, with the comics, and the books, and Star Wars Rebels—“We hear you, we get it, too. Star Wars is the Rebellion Era and always has been.”

December 24, 2014

Real Violence, Simulated Violence, and Thinking War is Awesome

Most of us enjoy violence. The top movies each year largely come from genres dependent on scenes of people getting hurt, whether comic book action, crime thrillers, horror, or sci-fi and fantasy epics. We play violent video games, shooting and punching and blowing up imaginary people or the avatars of other players.

But the violence we enjoy is fake. That’s important. I’m happy to watch a movie about people getting beaten up and murdered. I love crime fiction and shooting people in Grand Theft Auto. Yet show me the same stuff in real life–hell, ask me to imagine the same stuff in real life–and it’s not at all the same. In fact, I hate it. Violence–real violence–repels me, as it does most other people.

Things weren’t always like this, of course. Historically, we have countless instances of real violence as entertainment–think gladiators and public hangings–as well as the kind of common, everyday slaughter that indicates a lack of widespread aversion to violent acts. In fact, the growing distaste for violence, which eventually became disgust and outright horror, was necessary to us growing morally, as people and as civilizations. Good people do not commit violent acts–except perhaps in extreme instances of defense of self or others. Much less do they enjoy violent acts, actual violent acts, with real people suffering real pain.

Except, I’ve come to believe, some of us, at some level, still do. My supposition–and it must remain one because I’m not sure how to research its veracity–is that a great deal of foreign policy hawkishness, support for CIA torture, cheering on of brutal police behavior, and so on, is the result of people not possessing an instinctive recognition of the distinction between legitimately-exciting-but-pretend violence and the horror of real violence. In other words, there are people out there who get just the sort of pleasure in carrying out–or, most often, witnessing or thinking about–actual violent acts that you or I get from playing a first-person shooter or watching a terrific action scene. These are the people who, for example, talk about war as if it’s awesome. They get excited at the prospect of another bombing campaign. They love military hardware and can’t wait to see it put to use. Their first reaction to any problem overseas is to call for blowing people up.

This likely results from one or both of two particular failures, one of character, the other of reasoning. The first is a devaluing of the humanity of others, particularly others of different nations, religions, cultures, or colors. This is an outright moral failing. A morally good person will recognize the humanity of others and see violence against them as repugnant. A bad person will think some people are less worthy of basic dignity and so will be less concerned by violence against them.

The second failure doesn’t necessarily reflect on the person’s character so much as it does on the person’s wisdom in putting his moral motivations into practice. Here, the person doesn’t explicitly believe unsimulated violence is okay. Instead, he has a difficult time recognizing recognizing it. His mind treats real violence, especially real violence depected in media such as in news reports, as if it were simulated violence. Of course, if asked about this directly, the person won’t admit to thinking the violence in the news is fake. He’s not stupid. But in the moment, when watching it, or when thinking about a bombing campaign or the brutality of cops busting heads, he’ll subconsciously fool himself and approach it the same way the rest of us do simulated violence.

There’s an interesting difference in how progressives and conservatives go wrong in thinking about violence. By and large, progressives are more concerned about direct violence done by the state than conservatives. They tend to be more wary of war and lament civilian casualties. (Though partisanship complicates this, obviously, causing Democrats to show more support for state violence when it’s perpetrated by a Democratic president.) Progressives also tend to decry police violence against minorities and marginalized groups. But they also overlook a great deal of state violence. Every law and regulation they clamor for, after all, is backed by force and ultimately only carries weight as a law or regulation if there are men with guns prepared to shoot people who don’t comply. So progressives think real violence isn’t okay–or at least pay lip service to being turned off by it–but at the same time fail to recognize the violence baked into their vision for a well-functioning, well-covered, and largely state-run society.

Conservatives, on the other hand, seem more likely to recognize the pervasiveness of state violence, but care less about violence itself. They’re the ones–again, I’m dealing in broad generalties here–who champion bombing compaigns and respond to police bruality with, “Well, he/they had it coming.” Unlike progressives, they appear not to care about the harm. Or, worse, they see the violence as righteous and just. As deserved.

As I write this, it occurs to me that these opposed attitudes to real violence get sometimes flipped when the subject is simulated violence. By and large, cultural progressives don’t mind violence on television, in the movies, or in video games. They may not want their children watching or playing particularly violent media, but they don’t see it as the downfall of society or even much of a threat to their own kids’ wellbeing, and so don’t call for its censorship. Cultural conservatives, on the other hand, are frequently among the first to blame video games after a school shooting and say how Grant Theft Auto leads to more crime. Much of their ire at the media is, of course, more about displays of sex and alternative sexualities, but a good portion of it is reserved for violence. To risk too much of a generalization, progressives hate violence when it’s real and conservatives hate it when it’s fake.

I’m not quite sure what to make of any of this. And, like I said, it’s all based on general impressions on my part. I don’t know how one would set about proving or disproving that neoconservatives champion war in part because they get excited at the prospect of bombing people. Certainly, none of them would admit to it. But if I’m right, even a little, then it raises serious concerns about governing the country. It’s one thing to disagree about the data on which policy produces better results. Reasonable people can have rather divergent opinions. Likewise, we can have meaningful conversations about the proper distribution of state power versus personal freedom. But there’s no rational or moral groundwork for the view that violence engaging each other via violence is okay. It’s just not, full stop. And if there are people out there who don’t only think it’s okay, but at some level think it’s fun, then we’ve got problems. Big ones. We can, and must, be better than that.

December 16, 2014

Storytelling and Imaginary Worlds

Peter Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy isn’t very fun and that’s largely because it’s a trilogy. Lawrence Dodds claims this unnecessary expansion of a very short novel into a very long, three part film results from giving in to desires of nerds. Dodds’s article is interesting and worth reading, but also rather confused. He makes two claims when he thinks he’s making one, and it’s not clear either is to blame for the turgid storytelling of Jackson’s films.

Here’s Dodds’s first formulation of the problem:

This is what British sci-fi author M. John Harrison called “the clomping foot of nerdism” – and, unfortunately for all of us, it has taken over. In an essay which caused a storm in sci-fi’s teacup back in 2007, Harrison criticised the urge, felt by both authors and fans, to exhaustively catalogue every detail of an unreal world as if it were a real place rather than a literary device.

Nerds like heavily detailed worlds. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings was heavily detailed. His novel The Hobbit was not. The former, in Dodd’s opinion, lacked a good story. The latter exemplifies the “spirit of the storyteller.”

But does a world rich in detail get in the way of telling a great story? I’m not so sure. I can think of many examples of wonderful stories set in exceedingly detailed imaginary worlds. Dune, for instance. And let’s not forget that our own world is pretty detailed–“a real place rather than a literary device”–and yet we manage to tell good stories set within it all the time.

The problem with the Hobbit movies isn’t the exhaustive detail. It’s that Jackson can’t seem to figure out what the story is. In fact, most of what’s wrong with the movies isn’t the constant mention of world details. It’s the other stories Jackson piles in and the unnecessary action sequences he “contributes” to Tolkien’s tale.

That nerds like exhaustively detailed worlds isn’t a problem so long as nerds like good stories told in those worlds, too. And they do! Because everyone likes good stories and dislikes bad ones, and people generally agree that Jackson’s Hobbit movies lack something when it comes to storytelling.

Dodds’s goes on to raise another concern about nerd culture, as if it were the same as the first. But it’s not.

What nerds are chasing when they get passionate about canon is a fantasy of purity – the idea that a fictional world could be solely dictated by its own internal consistency and not by real-world demands. But they are forgetting how the original, Biblical canon was formed. Like some humming simulation, fantasy canons can be quickly snuffed out if their owners in the real world decree. Star Wars is changing because the people who own it want JJ Abrams to make a new movie and make them more money. They believe he can’t do that if he’s bound and encumbered on every side by the intricate designs of its previous stewards. That, in the end, is that.

Here he has brought up something weird about (some) nerd culture. It’s the Trekkie profoundly upset by inconsistencies between subsystems in the warp drive between episodes. It’s the tendency of a certain sort of nerd to blur the line between fantasy and reality.

But I’m not sure what this has to do with level of detail or how the two are necessarily linked. Look at cannon debates about old 80s cartoons with only a handful of episodes. Look at bronies.

For certain breed of nerd, system clarity matters more than it does to most. They like the world–or a world–to be comprehensible. It’s why they’re drawn to computers, which are unambiguous. It’s why they embrace utilitarianism, with its algorithmic approach to human morality. It’s why they dig Star Trek’s federation–with its clear rules and uncomplicated dress code–over the messy world outside their door.

But that’s its own issue and has little or nothing to do with the difference between Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit.

December 15, 2014

The Rot in America’s Soul

It’s difficult to overstate the evil of the acts documented in the torture report. To see the evil of the men who oversaw those acts, read through Dick Cheney’s Meet the Press interview from Sunday. Conor Friedersdorf has a good overview. Cheney sees nothing wrong with committing horrific acts against human beings, so long as doing so somehow, possibly leads to fulfilling his objective. Writes Friedersdorf,

That exchange leaves no room for mistaking former vice-president Cheney’s position: better to chain a man to the wall of a cell, douse him in cold water, and leave him there to freeze to death, even if he later turns out to be innocent, than to release that same man and risk not that he detonates a nuclear bomb in Manhattan, but that he ends up “on the battlefield,” where there’s a chance he could harm Americans. What if fully one-in-four prisoners tortured by the CIA were innocent?

Dick Cheney belongs in a cell. That much is obvious, and no reasonable, moral person can disagree. The trouble is, it’ll never happen. Cheney will live out the rest of his life free, getting paid for speeches, talking at conservative think tanks, and appearing on TV. He’s a war criminal who will be defended by partisans and will escape justice because of politics. America prides itself on its values and lectures the rest of the world about theirs. And there’s much to admire about American values. But how we treat evil reflects on our values, too. Especially when that evil used to have an office in the White House.

November 5, 2014

A Reply to My Essay on the Immorality of Voting

My friend and colleague Jonathan Blanks has written a response to my essay yesterday on the morally troubling aspects of voting. In the delightfully titled “Pay No Attention to the Man Who Won’t Stand Behind the Voting Curtain,” Blanks takes me to task for putting philosophy before practicality.

Philosophy has its place, as it informs our beliefs and ideals. However, removing yourself—and, more damning, those whom agree with you most—from the election process eliminates the largest incentive for politicians to care what you and those like you believe.

His argument is that even if my vote doesn’t decide the election–and the chance of it doing so is so small as to effectively not exist–government still pays attention to voting collectives.

But in toss-up districts and states, enough people who vote libertarian can, by shifting the margin, change the outcome of an election. A party that is on the losing end of that would be wise to cater to libertarian issues in the future.

Whether he’s right is a political science question, not a philosophy one. And he may be right that there are times practicality trumps moral purity. (Though if and when that’s true is, of course, a philosophical question!) But I think this is a case where we can both be right. As I wrote at the end of my piece,

If you cast a vote today, there’s a pretty high chance that in morally significant ways you’re acting just like those friends mugging the old man. You may think there are good reasons for doing this, that a world where you vote for violations of basic human dignity and autonomy will be more livable—happier, freer, wealthier, more equal—than one where you don’t. But you’re still party to countless immoralities.

Sometimes committing a moral wrong is justified. Sometimes we have very good reasons to do something unethical. (The inability to recognize and shed light on these situations is one of the chief reasons utilitarianism remains an unsatisfactory moral philosophy.) But that doesn’t mean they’re not still, to some extent, immoral.

A Quick Take on Peter F. Hamilton’s “The Reality Dysfunction”

Summer before last, I finished the Mass Effect trilogy and it left me wanting more space opera. I’d read a ton of science fiction in high school and early college, but then drifted into crime novels. Mass Effect gave me a newfound appetite for spaceships, galactic mysteries, and epic storytelling.

This took a bit of research, given how out of touch I was with the space opera genre. But I found Peter F. Hamilton, decided his Night’s Dawn trilogy was the place to start, and ordered The Reality Dysfunction. That was in July 2012. I finished the book this week. It’s a long book, but not that long.

Thing is, between starting my first Hamilton novel and finishing it, I read five-and-a-half more of his books: the two books of the Commonwealth Saga, the Void Trilogy, and the first part of Great North Road. In fact, from the time I picked up The Reality Dysfunction and today, Hamilton has accounted for a sizable chunk of my fiction reading. I’m hooked. I’ll likely polish off his entire corpus soon enough.

This book has everything that makes Hamilton great. Amazing world-building, economically-defined but still intriguing characters, terrific plotting. The pacing’s good, too, if you aren’t turned off by setting detail. (As a guy who grew up reading fat RPG books obsessively, I dig the stuff.)

But Hamilton made a poor decision in structuring the book, and it’s what caused me to take so long to finish it. While his later books feature lots of characters, he puts the focus on typically three or four. In The Reality Dysfunction, I lost count. Often, a lengthy section will be from the point of view of a character introduced for that section and then never seen again.

Anyone who played the Mass Effect trilogy–which, again, are what prompted my plunge into Hamilton’s books–knows that beyond anything else those games worked because of their characters. No matter how strange events got, they were grounded in a group of people you came to care about. Hamilton’s later books are the same. After finishing the Commonwealth Saga, I didn’t realize how much I missed some of the characters until they reappeared in the The Dreaming Void and it felt like bumping into old friends.

That’s what’s missing from The Reality Dysfunction. The world is excellent, the plot engaging, and I want to know how it all ends. But it reads like a series of events instead of the experiences of people. We’re not with any particular character enough to feel attached. Which made the book easy to drift away from. I liked it while I was reading it, but when I put it down for something else (a habit I appear completely stuck with), I didn’t feel much draw to go back. It’s one thing to find out what happens next. But what makes a book un-put-downable is wanting to find out what happens next to characters you care about.

Buy The Reality Dysfunction from Amazon

November 4, 2014

The Moral Ambiguity of Voting

For election day, I’ve published a new column at Libertarianism.org on the morally troubling aspects of voting.

When we vote, we aren’t just deciding for ourselves. We’re attempting to decide for others, too. We’re not just expressing a preference (“I prefer traditional taxis to ride sharing services.”), but also expressing a desire to see that preference made, through the application of violence or the threat of violence, the law of the land. We’re saying our opinions are so informed, correct, and important that we’re willing to have men with guns make our fellow Americans obey them, even if our fellow Americans also believe their own opinions are informed, correct, and important.

Aaron Ross Powell's Blog

- Aaron Ross Powell's profile

- 18 followers