Aaron Ross Powell's Blog, page 19

November 29, 2011

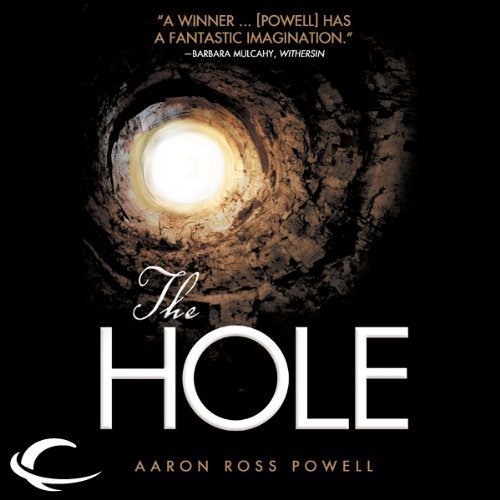

THE HOLE is now an audiobook!

I’m super thrilled to announce that THE HOLE is now available as a wonderfully narrated audiobook from Audible! What’s more, you can get it completely free!

To get the book for free, all you need to do is sign up for an Audible trial membership. That comes with one free book (which rather obviously ought to be THE HOLE). Download your book, cancel the membership, and keep the book. Easy and you don’t pay a thing. (Though if you like Audible–and you should because they’re great–then keep the membership and support them so they can do more of my books in the future.)

My novel benefits greatly from the terrific narration of Mark Boyett. I was completely out of the loop when it came to production, so I had no idea who’d be reading it until the finish product popped up on Audible’s site.

My novel benefits greatly from the terrific narration of Mark Boyett. I was completely out of the loop when it came to production, so I had no idea who’d be reading it until the finish product popped up on Audible’s site.

Lucky for me, Boyett is perfect. He nails the book’s tone and brings Elliot and Evajean to life. Interestingly–to me, at least–he brings them to life every-so-slightly differently than I imagined them. Elliot is less sure of himself by a tad than I’d thought him. Evajean is quieter. But it works. Really well.

In fact, my only complaint (and it’s the kind that’ll bother me and probably nobody else) is that Boyett pronounces her name “Eve-a-jean.” In my head, she’s “Eh-vah-jean.” So there you go.

Anyway, I love it. And I’m sure you will, too. Given how much better Boyett’s reading makes my prose sound, I now consider the audiobook the definitive version of THE HOLE.

So what are you waiting for? Go get it.

November 22, 2011

With Mitt Romney the presumptive frontrunner this election season, I think we all…

With Mitt Romney the presumptive frontrunner this election season, I think we all can agree that what's needed is a great horror novel drawing on Mormonism. Lucky for America, I've written one. And it's now out as an audiobook from Audible and +Permuted Press.

Embedded Link

The Hole

Check out this great listen on Audible.com. The world, as Elliot Bishop and Evajean Rhodes know it, is gone. Destroyed. In just two weeks, a horrific plague raged across the planet – driving its vi…

Google+: View post on Google+

November 21, 2011

Finished the homicide desk in L.A

Noire. The individual mysteries were pretty good, but the conclusion to that arc — and the way it tied together what came before — was downright silly. I can't stand the lazy mystery writing crutch of "We don't know how to solve this mystery, so let's just have the killer reveal himself." The first episode of the (otherwise brilliant) Sherlock did the same thing.Here's hoping the arson arc goes better.

Google+: View post on Google+

September 30, 2011

Rejoice! Facebook’s “frictionless sharing” IS all about the ads.

Facebook’s new “frictionless sharing” has the Internet in a tizzy. Even lawmakers are piling on.

The basic idea is this: It used to be if you wanted to, say, share the song you’re listening to into your Facebook account, you had to click on it and tell the program to “Share.” You had to take action. Frictionless sharing changes that. Now, you can give a music-streaming service like Spotify permission to automatically share everything you’re listening to, in real time, to you Facebook friends. Of course, Facebook gives you a great deal of control over who can actually see it–and you can turn it off on an app-by-app basis at any time.

(For example, I have Spotify setup to share my listening habits, but in such a way that only I can see them. So I get the benefits of the cool pattern recognition and timeline features, without having to tell all the world what songs I dig.)

People are, in general, reacting pretty negatively to this. (Or, at least, the most vocal people are reacting negatively.) However, in doing so, they’re often confusing two distinct criticisms of frictionless sharing. One is that it’s silly. The other is that it’s wrong.

Frictionless sharing is silly.

When I first heard Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg announce the feature, that’s exactly what I thought, too. Who is this thing for? I simply don’t care enough about the musical tastes or cooking choices of my friends (let alone my acquaintances) to want to see what they’re listening to or eating in real time.

Parents used to complain about how much their teenagers were always on the phone. Now it’s texting. But the underlying social urge is the same: Teens can’t get enough of each other. They’re all, “OMG! Did you hear what so-and-so did? I know, right?” Ubiquitous social content is the bread and butter of 13 year old girls.

Still, most of Facebook’s users are adults–and adults are content to get all the juicy details about their friends rather less often.

So it’s not immediately clear who this feature is for–other than, of course, Facebook and its advertisers. Which makes it appear, from the user’s perspective, downright silly. Except that the user’s mistaken. Frictionless sharing definitely is for Facebook and its advertisers. But it’s also for you.

But is frictionless sharing also wrong?

If frictionless sharing is just silly, then it’s easy to ignore. But if it’s wrong–like in the sense of ethically not-good-at-all–then we have more reason for concern.

So what’s wrong with it? There’s the privacy problems, of course. If you’re broadcasting everything you listen to, then you better be certain you don’t have any guilty pleasures. But this is easily fixed: either only make shared data visible to yourself or don’t allow sharing in the first place. Yes, Facebook’s privacy controls can be confusing, but the recent updates actually allow application developers to make the pop-up permissions request box more clear than it was before.

Your privacy isn’t really the root of the “it’s wrong” concern, however. You have control of that. What you don’t have control over is how Facebook uses the data it does collect about you. Call this the “You’re the product, not the customer!” argument.

To make money (Zuckerberg is in business, after all), Facebook could charge its users. At perhaps $10 a month, even if only 100,000,000 of them stick around, that’s still a billion bucks a month. Not too shabby. But Facebook doesn’t charge. From the user’s perspective, Facebook is free–and will stay that way.

What Facebook does instead is sell advertising, giving over a portion of each page to third-party marketers hawking their wares to Facebook’s enormous user base. And to do this–or, at least, to do it well–they need data. About you.

Advertising’s only annoying when it sucks.

We all claim to hate advertising. Except that we really don’t. What we hate is advertising we’re not interested in. If I pick up a copy of Better Homes and Gardens and flip through it, what I find are pages and pages of awful, annoying ads. Call these “spam.”

Back in middle school, though, when I grabbed a copy of Dragon Magazine, the Dungeons & Dragons periodical, off the shelf in the school library, I didn’t see those adverts as spam. No, they were cool. Informative. They were content.

The difference, obviously, is that Better Homes and Gardens is filled with ads for products I don’t care about. Dragon, on the other hand, featured ads telling me about things I actually wanted.

And that’s where Facebook’s data comes in. Facebook needs to gather data if its advertisers are going to give me Dragon ads (content) instead of Better Homes and Gardens ones (spam). In fact, the more data Facebook has about me, the more likely I am to see the ads as content instead of spam.

This is what frictionless sharing does. It’s also the answer to the “What’s in it for me?” question. Frictionless sharing lets Facebook improve my experience on its site by increasing the quality of the ads it serves to me. This is a win for its advertisers (they’re more likely to get a new customer), a win for Facebook (it can charge more for the ad space), and a win for me (I like learning about new products I actually want and enjoy).

This is why it seems so odd when people get upset at customer data gathering in general. If that data’s being used in a dangerous way, then there’s cause for concern. Obviously. But the reason Facebook wants that data is not to hurt me or you. It’s to make our Facebook experience better.

And, hey, you can always just turn it off.

March 14, 2011

The 99¢ E-book Means Shorter Books–and that’s Good.

This book is too long.

E-book prices appear to be in a race to the bottom. When Amazon first opened its Kindle store, it priced most bestsellers at $9.99. Big publishers fought for higher prices, both to put more money in their pockets and to prevent “devaluing” books. But authors went the other direction. As David Carnoy explained in a recent article for CNET, “Just last year, the magic price point for a lot of indie (self-published) authors was $2.99.” Even this puny price–just a third what many mass-market paperbacks cost–didn’t last. Carnoy goes on, “But then something happened on the the way to the check-out cart. Some authors started saying, ‘Screw it, I’m not selling that much at $2.99, I’ll just go to 99 cents and see what happens.’ And bam, some of these books took off. And some really took off.”

Will Someone Not Think of the Authors?

This incredible shrinking price has provoked genuine questions about the future of the book, however. Today, a new fiction hardcover retails for around $30. Amazon discounts that, as do many bookstores, but even the discounted price far exceeds $0.99. Authors happily put in the long, long hours it takes to write a novel in exchange for their (surprisingly small) cut of $30. (“Surprisingly small” typically meaning somewhere between 10% and 15%, or $3 to $4.50.) Earning $3 for each copy sold without doubt beats the 29 cents Amazon gives an author when his book sells for $0.99.

The result of these one-tenth royalties, the worry goes, is fewer books. Who wants to put in the long, long hours it takes to write a novel if you’re only going to pocket a little more than a quarter each time someone reads it? (At $2.99, Amazon’s kickback to the author jumps to $2, which looks a whole lot better–and a whole lot closer to print book rates.)

Let’s set aside the reasonable counter that, at $0.99 (or even at $2.99), readers are likely to buy quite a few more novels than they did at $9.99 or $30. After all, no matter what the price, people only have so many hours in the day to read. It’s also why I believe $0.99 novels won’t mean fewer novels. Instead, $0.99 novels will mean shorter novels.

And that’s a very good thing.

Most Books are Too Long

Ed McBain’s first 87th Precinct novel, Cop Hater, publish in 1956, ran 166 pages. A decade later, in 1968, McBain published Fuzz, at 288 pages. By 1989, with Lullaby, the page count ballooned to 432. The length of McBain’s work fluctuated, but never settled to anything approaching Cop Hater’s sub-200.

Elmore Leonard’s famous 1961 novel, Hombre, runs a mere 208 pages. Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon is only 217 pages, while Raymond Chandler’s classic, The Big Sleep, is only 139. Would any of these giants of fiction been better longer?

These books are just right.

A place exists for long books, of course. Sticking with the crime genre, James Ellroy’s magisterial L.A. Confidential is 512 pages, without an ounce of fat. (The novel’s famously spare prose style in fact resulted from his publisher telling Ellroy that the original manuscript was far too long, Ellroy said to me at a book signing once. Ellroy went back and removed every unnecessary word, so as to bring the length down without impacting the labyrinthine plot.) Long novels can develop character and setting and mood in a way short novels often can’t. Long novels can, in that sense, be richer than their shorter peers.

But most authors don’t write rich novels. And most novels need not be rich. The bulk of fiction is not Charles Dickens or Marcel Proust, nor should it be. The bulk of fiction is story and stories frequently are better shorter. Infinite Jest (1104 pages) is great, but an armful of books like that would make any of us long for And Then There Were None (272 pages).

In Praise of Short Books

Few people walk out in the middle of a movie, even if it’s rather bad. Few of us will drop a novel once we’re more than a third in, even if the prose is miserable. We engage in such irrational behavior not because we’re crazy or because we don’t understand sunk costs. Rather, we stick with mediocre (or worse) storytelling because we want to know how the story ends.

In this way, long novels ask a great deal of their readers. If the novel is wonderful, the extra time the author demands will be repaid with dividends when the final page is reached. But most novels aren’t wonderful and almost all of us can think of several books we finished and thought, “That was okay or even pretty good, but it could’ve been half that long.”

The simple fact is that most novels are too long. We authors could learn a lot from the masters of the pulps, who churned out tale after rip-roaring tale, offering huge entertainment in very small packages. We may think our opus is worthy of 700 pages, but it’s probably not. And a 700 page book means asking our readers to forgo the other 350 page book they could’ve read if ours had been half as long. Or the two-and-a-half other books they could’ve read if novels averaged a reasonable 200 pages.

Cheaper Books are Shorter Books

That’s exactly what I predict will result from the price of novels dropping to a buck. Authors won’t give up writing (if we did it to get rich, few of us would be writing today, anyway). Rather, seeing that they’ll only earn a quarter for every sale will make writers look at their works not as monuments it took them ten years to craft and so it better take the reader that much time to appreciate. Instead, authors will shift back into the pulp mindset, seeing their books as stories to be written quickly for maximum entertainment, before moving on to the next.

In an ideal world, novels would settle into a happy length of around 50,000 words–or a little over 150 pages. That’s more than enough space to tell most stories.

And it’s short enough that readers can finish it quickly and move on to the author’s next 50,000 word, 99 cent pageturner.

Aaron Ross Powell's Blog

- Aaron Ross Powell's profile

- 18 followers