Aaron Ross Powell's Blog, page 18

October 3, 2012

A proto-"Politics Makes Us Worse"

Politics does awful, awful things to us–and anyone seeking virtue ought to avoid politics to the greatest extent possible. That’s the thesis my colleague Trevor Burrus and I developed in our short essay, “Politics Makes Us Worse.” And it’s a thesis found in this wonderful passage from Auberon Herbert’s 1908 essay, “Mr. Spencer and the Great Machine.”

We all know that the course which our politicians of both parties will take, even in the near future, the wisest man cannot foresee. We all know that it will probably be a zigzag course; that it will have “sharp curves,” that it may be in self-evident contradiction to its own past; that although there are many honorable and high-minded men in both parties, the interest of the party, as a party, ever tends to be the supreme influence, overriding the scruples of the truer-judging, the wiser and more careful. Why must it be so, as things are today? Because this conflict for power over each other is altogether different in its nature to all other—more or less useful and stimulating—conflicts in which we engage in daily life. As soon as we place unlimited power in the hands of those who govern, the conflict which decides who is to possess the absolute sovereignty over us involves our deepest interests, involves all our rights over ourselves, all our relations to each other, all that we most deeply cherish, all that we have, all that we are in ourselves. It is a conflict of such supreme fateful importance, as we shall presently see in more detail, that once engaged in it we must win, whatever the cost; and we can hardly suffer anything, however great or good in itself, to stand between us and victory. In that conflict affecting all the supreme issues of life, neither you nor I, if we are on different sides, can afford to be beaten.

There is little noble about politics. No matter how grand you think your favored politician is, chances are he’s engaged in exactly what Herbert describes.

A proto-”Politics Makes Us Worse”

Politics does awful, awful things to us–and anyone seeking virtue ought to avoid politics to the greatest extent possible. That’s the thesis my colleague Trevor Burrus and I developed in our short essay, “Politics Makes Us Worse.” And it’s a thesis found in this wonderful passage from Auberon Herbert’s 1908 essay, “Mr. Spencer and the Great Machine.”

We all know that the course which our politicians of both parties will take, even in the near future, the wisest man cannot foresee. We all know that it will probably be a zigzag course; that it will have “sharp curves,” that it may be in self-evident contradiction to its own past; that although there are many honorable and high-minded men in both parties, the interest of the party, as a party, ever tends to be the supreme influence, overriding the scruples of the truer-judging, the wiser and more careful. Why must it be so, as things are today? Because this conflict for power over each other is altogether different in its nature to all other—more or less useful and stimulating—conflicts in which we engage in daily life. As soon as we place unlimited power in the hands of those who govern, the conflict which decides who is to possess the absolute sovereignty over us involves our deepest interests, involves all our rights over ourselves, all our relations to each other, all that we most deeply cherish, all that we have, all that we are in ourselves. It is a conflict of such supreme fateful importance, as we shall presently see in more detail, that once engaged in it we must win, whatever the cost; and we can hardly suffer anything, however great or good in itself, to stand between us and victory. In that conflict affecting all the supreme issues of life, neither you nor I, if we are on different sides, can afford to be beaten.

There is little noble about politics. No matter how grand you think your favored politician is, chances are he’s engaged in exactly what Herbert describes.

August 1, 2012

This month: THE HOLE for just $0.99.

Now through August 22, Permuted Press has a bunch of great titles on sale for just 99 cents. Including my novel, THE HOLE. So if you haven’t read it already (really?!?), now’s a great time to pick it up.

From the back cover:

The world as Elliot Bishop and Evajean Rhodes know it is gone. Destroyed. In just two weeks, a horrific plague raged across the planet—driving its victims insane before killing them.

The two survivors set out on an unimaginable journey, driven by a cryptic message from Evajean’s husband: If anything terrible happens, you must get to Salt Lake City. But the pair soon discover they are not alone, and that the plague has done more than kill. The countryside between Virginia and Utah now crawls with victims who have been driven mad—violent lunatics fueled with definite yet unknown purpose.

To survive, Elliot and Evajean must fight for their lives—against the crazies, against sinister forces who would stop their quest, against long-ago hidden menaces—and uncover the deeply guarded secret of those driven mad and the plague that spawned them. The secret of a destructive force unleashed on the world by one of America’s most powerful religious sects…

Get it for pretty much any ebook reader you can imagine–and in print–right here.

July 31, 2012

Aristotle and the Corrosive Influence of Modern Politics

Some time back I wrote a piece at Libertarianism.org arguing that politics makes us worse. I didn’t (just) mean that politics makes us worse off, or that the country itself would be better managed if politics worked better. No, what I meant (in addition to those things) was that politics–the politics of partisanship, one-upmanship, and hating our fellow citizens because they’re on team red or team blue–makes us worse people. It corrupts us, degrades us, makes us vicious.

Some time back I wrote a piece at Libertarianism.org arguing that politics makes us worse. I didn’t (just) mean that politics makes us worse off, or that the country itself would be better managed if politics worked better. No, what I meant (in addition to those things) was that politics–the politics of partisanship, one-upmanship, and hating our fellow citizens because they’re on team red or team blue–makes us worse people. It corrupts us, degrades us, makes us vicious.

Now my colleague Trevor Burrus and I are expanding that thesis into a long essay titled “Politics Makes Us Worse.” As part of my research, I’ve returned to Aristotle. I was delighted to come across this passage in his Nicomachean Ethics where Aristotle speaks to the point I’m trying to make.

But the virtues we get by first exercising them, as also happens in the case of the arts as well. For the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them, e.g. men become builders by building and lyreplayers by playing the lyre; so too we become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts.

This is confirmed by what happens in states; for legislators make the citizens good by forming habits in them, and this is the wish of every legislator, and those who do not effect it miss their mark, and it is in this that a good constitution differs from a bad one.

Again, it is from the same causes and by the same means that every virtue is both produced and destroyed, and similarly every art; for it is from playing the lyre that both good and bad lyre-players are produced. And the corresponding statement is true of builders and of all the rest; men will be good or bad builders as a result of building well or badly. For if this were not so, there would have been no need of a teacher, but all men would have been born good or bad at their craft. This, then, is the case with the virtues also; by doing the acts that we do in our transactions with other men we become just or unjust, and by doing the acts that we do in the presence of danger, and being habituated to feel fear or confidence, we become brave or cowardly. The same is true of appetites and feelings of anger; some men become temperate and good-tempered, others self-indulgent and irascible, by behaving in one way or the other in the appropriate circumstances. Thus, in one word, states of character arise out of like activities. This is why the activities we exhibit must be of a certain kind; it is because the states of character correspond to the differences between these. It makes no small difference, then, whether we form habits of one kind or of another from our very youth; it makes a very great difference, or rather all the difference.

As politics takes over more and more of our lives and so we have more and more reason to engage in politics, we’ll come to see the sort of vicious behavior politics encourages as normal. In Aristotelian terms, we will be habituated into vice and away from virtue. Politics will (and does), in other words, make us worse.

March 14, 2012

How I don't think about morality

Ethical philosophy–and introductory ethics courses–brim with quandaries. There’s a trolly car barreling down the track toward three people. They can’t get out of the way and will surely die if the car hits them. But wait! The track splits and on the other fork sits just one guy. And there’s a switch right in front of you that’ll cause the track to switch and the car to kill him instead of the three people it’ll kill if you don’t act. What do you do?

Theses quandaries exist, of course, to provoke moral thinking. They complicate assumptions of freshmen, they illuminate intuitions, and they serve to distinguish ethical theories at a fine level. What’s more, a moral theory that fails to answer one of these quandaries fails as a moral theory. Because it’s the hard questions that matter, right?

Not really. I’ve grown tired of quandary ethics and it’s why, in part, I find virtue ethics so compelling. The kind of ethical thinking quandaries represent, where factors and rules are weighed and examined to produce an algorithm for morality, seems as far divorced from the way we actually think about morality as the computer code underlying Adobe Photoshop is from the paintings the artist creates within it.

This divide has been particularly clear to me due to what amounts to a timing accident. Concurrent with my exploration of virtue ethics, I’m reading, for the first time, Derek Parfit’s monumental Reasons and Persons. And, while the former resonates, the latter often leaves me cold.

Pushing ethics towards quandaries and improbable scenarios moves it away from the problems all of us really encounter–the problems we need moral philosophy to address. I’ve never been in a trolly car situation and likely never will be.

Much modern moral thinking holds fast to the idea that we should imagine increasingly bizarre situations, apply our theories to those, and mark them as failures if they can’t come up with the right–or even an–answer. The method informs a great deal of Parfit’s book, particularly its early portions about self-defeating theories and whatnot.

Two things stand out this contemporary style of ethical thinking. First, its need for odd hypotheticals to expose a theory’s failures leaves open the possibility that many of these discarded theories would do quite well in every moral circumstance most of us will ever be in. Thus discarding a theory because it fails in weird setups with vanishingly small likelihoods is like discarding the West Coast offense because it’ll do you no good if the other team fields nine foot tall defensive backs who can run the 40 in half a second.

Second, the need to answer quandaries strikes me as something of a false dilemma. Isn’t it more likely that there exist moral situations with no good answer? That no matter what we do in the trolly car scenario, we’ll do wrong? That, even if we (somehow) pick the “better” answer, we’ll still have something to atone for?

This is why ethics as a set of rules to follow gets it at least partly wrong. Presumably following the rules precisely to a conclusion would mean getting the “right” answer. But it seems obvious that many moral situations have no right answer. The same applies to the consequentialist approach. Measuring utility will always point to a “right” answer–except in probably nonexistent situations where the utility gains (or losses) from the two options match exactly.

Thus hard-and-fast deontology and consequentialism don’t, I believe, get it right. They insist on “correct” answers where none exist and, more importantly, fail to match the way we actually think about ethics. Both have much to contribute, of course, but as theories meant to explain the whole of morality, I find both decidedly lacking.

How I don’t think about morality

Ethical philosophy–and introductory ethics courses–brim with quandaries. There’s a trolly car barreling down the track toward three people. They can’t get out of the way and will surely die if the car hits them. But wait! The track splits and on the other fork sits just one guy. And there’s a switch right in front of you that’ll cause the track to switch and the car to kill him instead of the three people it’ll kill if you don’t act. What do you do?

Theses quandaries exist, of course, to provoke moral thinking. They complicate assumptions of freshmen, they illuminate intuitions, and they serve to distinguish ethical theories at a fine level. What’s more, a moral theory that fails to answer one of these quandaries fails as a moral theory. Because it’s the hard questions that matter, right?

Not really. I’ve grown tired of quandary ethics and it’s why, in part, I find virtue ethics so compelling. The kind of ethical thinking quandaries represent, where factors and rules are weighed and examined to produce an algorithm for morality, seems as far divorced from the way we actually think about morality as the computer code underlying Adobe Photoshop is from the paintings the artist creates within it.

This divide has been particularly clear to me due to what amounts to a timing accident. Concurrent with my exploration of virtue ethics, I’m reading, for the first time, Derek Parfit’s monumental Reasons and Persons. And, while the former resonates, the latter often leaves me cold.

Pushing ethics towards quandaries and improbable scenarios moves it away from the problems all of us really encounter–the problems we need moral philosophy to address. I’ve never been in a trolly car situation and likely never will be.

Much modern moral thinking holds fast to the idea that we should imagine increasingly bizarre situations, apply our theories to those, and mark them as failures if they can’t come up with the right–or even an–answer. The method informs a great deal of Parfit’s book, particularly its early portions about self-defeating theories and whatnot.

Two things stand out this contemporary style of ethical thinking. First, its need for odd hypotheticals to expose a theory’s failures leaves open the possibility that many of these discarded theories would do quite well in every moral circumstance most of us will ever be in. Thus discarding a theory because it fails in weird setups with vanishingly small likelihoods is like discarding the West Coast offense because it’ll do you no good if the other team fields nine foot tall defensive backs who can run the 40 in half a second.

Second, the need to answer quandaries strikes me as something of a false dilemma. Isn’t it more likely that there exist moral situations with no good answer? That no matter what we do in the trolly car scenario, we’ll do wrong? That, even if we (somehow) pick the “better” answer, we’ll still have something to atone for?

This is why ethics as a set of rules to follow gets it at least partly wrong. Presumably following the rules precisely to a conclusion would mean getting the “right” answer. But it seems obvious that many moral situations have no right answer. The same applies to the consequentialist approach. Measuring utility will always point to a “right” answer–except in probably nonexistent situations where the utility gains (or losses) from the two options match exactly.

Thus hard-and-fast deontology and consequentialism don’t, I believe, get it right. They insist on “correct” answers where none exist and, more importantly, fail to match the way we actually think about ethics. Both have much to contribute, of course, but as theories meant to explain the whole of morality, I find both decidedly lacking.

March 9, 2012

Thoughts on virtue ethics

I don’t remember encountering virtue ethics much during my undergraduate philosophy degree. We hit on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, of course, the work that serves as the foundation of virtue ethics.

But I don’t believe virtue ethics was ever presented to me as a serious alternative to consequentialism and deontology. And this is too bad. Because only recently did I “discover” virtue ethics–and my initial explorations reveal it as something far more fitting both my views of morality, descriptive and normative, and my temperament than the two big schools of moral philosophy.

Put very simply, virtue ethics differs from consequentialism and deontology in the basic way it answers the “What action is right?” question. Rosalind Hursthouse, in her excellent On Virtue Ethics, summarizes the schools as follows:

Act Utilitarianism: “An action is right if and only if it promotes the best consequences. … The best consequences are those in which happiness is maximized…”

Deontology: “An action is right if and only if it is in accordance with a correct moral rule or principle. … A correct moral rule (principle) is one that…”

Virtue ethics, again quoting Hursthouse, holds that

An action is right if and only if it is what a virtuous agent would characteristically (i.e., acting in character) do in the circumstances. … A virtuous agent is one who has, and exercises, certain character traits, namely, the virtues. … A virtue is a character trait that …

Utilitarian has always troubled me for two reasons, both of which are common criticisms. First, it’s not at all easy to figure out what act will promote the best circumstances. How do we measure? Over what timeframe? Does measuring end up taking so long that, like Hamlet, we never quite get around to deciding? Second, many actions that do seem to increase overall happiness are still, well, wrong. A classic example is killing a homeless guy in the hospital–a guy with no family, no one who’d even know he died–in order to use his organs to save the lives of three people. One person dead is “happier” overall than three people dead, it seems.

Of course, utilitarians offer ways around this. But they’ve never convinced me–and they certainly haven’t convinced me about the first concern.

Deontology sounds better at first. But in order for it to work, we have to know what the rules are and how to apply them. And even simple rules–“Don’t kill.”–get complicated rather quickly. What about self-defense? War? Euthanasia? We can construct more rules and sub-rules to handle these situations, but it strains credulity to think we can have rules covering all situations.

Virtue ethics says simply, “Do what the best of us would do.” In fact, in the form of “What would Jesus do?” it’s probably the most common moral framework among those who don’t think much about moral frameworks.

What’s more, I believe this is the way we actually deal with moral conundrums. It’s not that I shouldn’t deceive because deceiving creates unhappiness or because it violates a rule I was taught. Rather, I don’t deceive because I don’t want to be a deceitful person.

So from the descriptive standpoint–i.e., how we in fact think about morality–virtue ethics sounds more plausible. It also, to my mind, works better normatively. When teaching children to be moral, we don’t tell them to measure utility and we don’t give them exhaustive lists of rules covering every imaginable situation. Instead, we teach them the value of honesty. Of kindness. Of courage and temperance and compassion. We instill in them character traits and then let them apply those traits to situations. What would a courageous person do? What would a kind person do?

Virtue ethics may turn out to be wrong, to be flawed beyond repair. I’m reading an essay now arguing that much of it is from the perspective of modern psychology, for instance.

But virtue ethics has clicked for me in a way no other moral theory to date has. Which makes me wish I’d been given a whole lot more of it back in school.

January 24, 2012

"Animus: Six Tales of Crime and Terror" is now available!

My new short story collection, Animus: Six Tales of Crime and Terror, is now available on the Kindle for just 99 cents. And if you’re an Amazon Prime member, you can get it for free from the Kindle Lending Library.

The collection’s pretty diverse, with some long stories and some quite short. The common theme is bad people up to bad things–hence the title. Here’s the cover blurb:

Three people with secrets to hide meet at a roadside bar during a storm–a meeting that quickly turns deadly. In the very near future, a detective takes a case that leads him into the twisted world of genetic modification and artificial intelligence. An ex-cop is asked to investigate the odd old lady who lives across the street–and discovers truths far weirder than he could’ve imagined. These stories an more can be found in Animus: Six Tales of Crime and Terror.

“Animus: Six Tales of Crime and Terror” is now available!

My new short story collection, Animus: Six Tales of Crime and Terror, is now available on the Kindle for just 99 cents. And if you’re an Amazon Prime member, you can get it for free from the Kindle Lending Library.

The collection’s pretty diverse, with some long stories and some quite short. The common theme is bad people up to bad things–hence the title. Here’s the cover blurb:

Three people with secrets to hide meet at a roadside bar during a storm–a meeting that quickly turns deadly. In the very near future, a detective takes a case that leads him into the twisted world of genetic modification and artificial intelligence. An ex-cop is asked to investigate the odd old lady who lives across the street–and discovers truths far weirder than he could’ve imagined. These stories an more can be found in Animus: Six Tales of Crime and Terror.

December 19, 2011

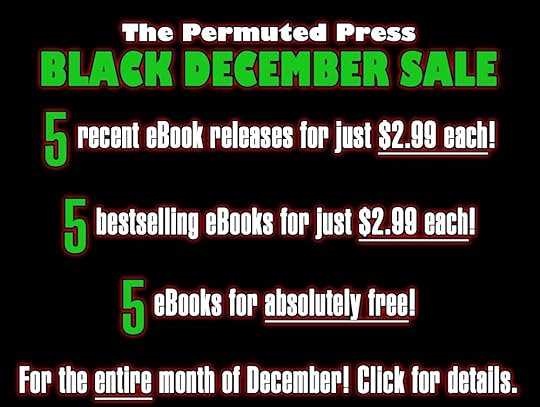

Permuted Press Black December Sale

My awesome publisher, Permuted Press, is having a Black December Sale. You can get tons of great horror titles for super cheap–or free.

Including my novel, THE HOLE, which is just $2.99 as an ebook all this month.

So check it out. And download some free books.

Aaron Ross Powell's Blog

- Aaron Ross Powell's profile

- 18 followers