Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 11

May 25, 2023

The Marriage — “An Alchemical Quest”

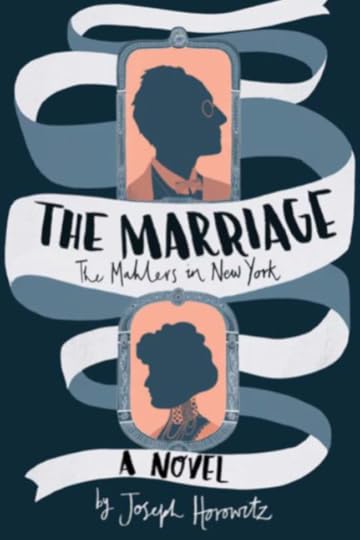

From Erik den Breejen’s review of my novel The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York, in the current New York Sun::

“Mr. Horowitz’s is an alchemical quest – to bring memories and accounts from dusty archives to life . . .

“When recreating a rehearsal of Mahler’s own Second Symphony, Mr. Horowitz’s rich use of detail compellingly evokes the feeling of the music but also the artist’s own unease in his new home: ‘a hushed and distant trumpet song, a tender lullaby over cascading harps. Memories – despoiled by these renegade Americans in a city of cement.’

“This in contrast to the vivid description of the triumphant debut performance in Munich of Mahler’s ‘Symphony of a Thousand’ . . . The music created ‘a surging organism, a sentient community bound by a single primal impulse of apocalyptic sound and feeling.’

“While rehearsing the orchestra, Mahler instructs the players that the work is “a mosaic, not a blend. Shifting grains of color, always individual grains” – an astute description of Mahler’s music as well as The Marriage itself, with its myriad distinct strains coalescing into a convincing whole.”

Den Breejen also writes:

“One of the central problems facing contemporary orchestras is how to appeal to a generation raised on 15-second videos. A ‘dumbing down’ of programming is not what Mr. Horowitz sees as the solution. ‘’Orchestras have moved in a different direction than museums,’ he says. ‘The thing that most dismays me is that museums are so far ahead of orchestras. They have scholars on staff, they embrace scholarship, they curate the past, which means they have a knowledgeable understanding of previous achievement, and in particular, American achievement. No orchestra even aspires to do that. . . . ‘

“Amid this weekend’s sold-out performances of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony led by the New York Philharmonic’s future music director, Gustavo Dudamel — who inspired the character Rodrigo on the Amazon series Mozart in the Jungle — I asked Mr. Horowitz if he thought the problem of the ‘celebrity conductor’ that he outlined in Understanding Toscanini persisted to this day.

“He offered diplomacy, while adding, ‘The fact that a conductor, rather than a composer, should be the iconic musician, is, I think, a problem that begins with Toscanini and exists to this day.’’

May 23, 2023

Boulder’s 36th (!) Mahlerfest — A Communal Labor of Love

The author riding the carousel at Nederland (alt. 8,000 feet), 30 minutes from Boulder.

The author riding the carousel at Nederland (alt. 8,000 feet), 30 minutes from Boulder.Thirty-six years ago, the conductor Robert Olson, a faculty member at Boulder’s University of Colorado, created Colorado Mahlerfest for hungry Mahlerites. In 1987, performances of Mahler symphonies were far less common, far less pervasive than today. The first Mahlerfest comprised the First Symphony, an early movement for piano quartet, and a set of songs.

Mahlerfest XXXVI, which concluded last Sunday afternoon, included three orchestral concerts, two chamber music concerts, and a film. As the author The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York, I took part in an all-day symposium. The entire festival experience was impressive.

Mahler’s is not living-room music. He composed big pieces for a community of listeners. It was the communal aspect of Boulder’s Mahlerfest that surprised me most..

The centerpiece of the festival was a performance of the Resurrection Symphony, which lasts ninety minutes and requires a large orchestra, offstage brass and percussion, two vocal soloists, and a big chorus. The audience at Macky Hall, on the University of Colorado campus, numbered about a thousand. Completed in 1922, the hall is picturesque, with tall cathedral windows. The rapt audience was remarkably inter-generational – something not to be found in New York City concert halls these days, and crucial to the ambience of shared experience.

As unusual is that the orchestra of 100-plus players felt part of it all. They arrived to play Mahler from all over the United States. Only the principal players were paid. The others came as a labor of love.

The conductor was Kenneth Woods, in charge since Olson’s departure in 2015. A gifted speaker and thinker, he is a pervasive presence. He is not addressed as “maestro” – the presiding maestro being Gustav Mahler.

Woods’ performance of Mahler 2 left no doubt that he is a major Mahler interpreter. I have heard cleaner performance of this work, but never one more convincing. The symphony suffered a long and tortuous gestation lasting some six years. The first movement is a funeral march, the second a Landler of sorts, the third a kaleidoscopic scherzo. After that, the piece goes its own way, with agonized words by Klopstock and Mahler, an opening of graves, a march of the dead, and a final paean of transcendence.

This blazing sequence risks shattering under pressure into disconnected shards of brilliance. The opening march movement alone, some twenty minutes long, combines grief and fury with soaring intimations of serenity. Mahler asks that the fundamental speed change more than two dozen times. Woods’ reading here embraced an exceptional range of mood and tempo. But a mighty Ur-pulse was sustained. The movement ends with a wasted tread, then a torrential scalar descent, then two pizzicato chords. Reading a sharply accented staccato triplet, Woods’ violas (an exceptional group) more than honored the score; they enacted the dirge’s culminating fatigue. The play of tempo in these closing measures was so keenly gauged that the silences told loudly and precisely. And so it was in the subsequent movements, with their many critical pauses; the trajectory remained organic. Midway through the pivotal mezzo-soprano solo – right at “the loving God will grant me light” — the Boulder sun emerged, streaming through the high cathedral windows. An uncanny moment.

Woods was also responsible for the artistic heft of the festival’s five packed days. The Resurrection Symphony was preceded by an ambitious symphonic work by Thea Musgrave: Phoenix Rising (1997). A Mahler “Liederaband,” recreating Mahler’s Vienna concert of January 29, 1905, comprised sixteen songs with orchestra: Kindertotenlieder, Ruckert-Lieder, and selections from Des Knaben Wunderhorn. A chamber orchestra program comprised the American premiere of Hans Gal’s Fourth Symphony (1974) and act one of Wagner’s Die Walkure (with reduced forces). Two chamber music concerts included a terrific rendition of Korngold’s String Sextet (Op. 10), Ernest Bloch’s Suite for Cello and Piano (a transcription of his viola suite), and shorter works by Max Reger, Erwin Schulhoff, Egon Wellesz, Olivier Messiaen, and Luciano Berio.

Next May, Mahlerfest XXXVII will explore the relationship between Mahler and Richard Strauss. The orchestral fare will include Mahler’s Fourth and Strauss’s Alpine Symphony. I’ll be there.

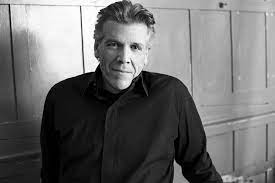

The 2023 Mahlerfest Symposium may be accessed here. My presentation begins one hour and 48 minutes into the link and includes commentary by Thomas Hampson. I deal with (1) Mahler’s New York performances and what they sounded like, and (2) why Henry Krehbiel regarded Mahler’s New York Philharmonic tenure a “failure” (and how I turn their relationship into historical fiction).

May 15, 2023

“Re-Imagining Mahler” — A Colorado Mahlerfest Live-Stream this Saturday

“Re-Imagining Mahler – and Why His Brief New York Philharmonic Tenure Was Truly a ‘Failure’” is the topic of my talk at this Saturday’s Colorado Mahlerfest Symposium in Boulder. I’ll also address creative fiction as a vital tool for the cultural historian.

I’ll be joined (from Vienna) by Thomas Hampson – who has recorded another excerpt from my new novel The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York (which among other things explains the nature of Mahler’s “failure”).

The Symposium will be live-streamed here.

You can see the day’s line-up of talks here (I’m 10:15 to 11:45 am Mountain Time).

You can listen to Tom read the beginning of my chapter one — the Mahlers being greeted by Heinrich Conried, the Metropolitan Opera’s bumbling manager — here:

May 8, 2023

Thomas Hampson Reads from “The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York”

Thomas Hampson, a singer long identified with the songs of Gustav Mahler, has kindly recorded a couple of excerpts from my new novel The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York – a book he calls “revelatory.”

Here’s Tom reading my account of Gustav and Alma interacting in Gustav’s dressing room, following a rehearsal of Tristan und Isolde at the Metropolitan Opera:

If you’re curious to know how my book begins, you can see me reading the opening chapter – in which Heinrich Conried, the bumbling director of the beleaguered Metropolitan Opera, greets the famous couple from Vienna.

I next discuss The Marriage at the Colorado Mahlerfest symposium on May 20 in Boulder.

My Einsamkeit, adapting songs by Mahler and Schubert for bass trombone and piano, will be performed with choreopraphy by Igal Perry at New York’s Peridance Center on June 17 and 18.

My Mahlerei, a bass trombone concerto adapting the scherzo from Mahler’s Fourth Symphony, will be performed by David Taylor at the Brevard Music Festival on July 5.

Advance Praise for The Marriage:

Horowitz is a master of what I would call “passionate scholarship.” He has a stake in what he writes. There is a lot of very sensitive skin in his game. As a literary writer he is at heart the free-spirited scholar he has been for decades; his prose frames in precise words the psychological ambiguities of personalities no less than the nu- ances of musical compositions or performances. His deep histor- ical knowledge blends with his narrative imagination to bring to life the sounds, the smells, the physical textures, the very air his characters breathed: Gustav and Alma Mahler are, at the same time, accurate historical portraits and haunting literary presences.

Antonio Muñoz Molina, winner of the Jerusalem Prize

❦

Despite his emotions having so often been on show, there has al- ways been something enigmatic and unknowable about Gustav Mahler. But where biographers and other musicologists have struggled, Joseph Horowitz succeeds brilliantly in revealing the inner Mahler in this powerful and moving novel. It is a triumph of historical imagination.

Richard Aldous, author of Tunes of Glory: The Life of Malcolm Sargent; Eugene Meyer Professor of History and Culture, Bard College

❦

If we want to get closer to the “truth” of Mahler and his music, if we hope to improve our understanding of the person and his crea- tions, we need to acknowledge the role our imagination must play in the learning process. In the case of Mahler, the essential facts have long been known. What we need now are fresh attempts to conceive what further truths they might contain. Joseph Horow- itz’s brilliant novel reveals much to us about who Mahler was, what he accomplished, and how he related to his world. Readers will be as eager to study it as they would any biography, and they can expect to learn as much.

Charles Youmans, author of Mahler and Strauss: In Dialogue (2016); editor of Mahler in Context (2021); Professor of Musicology, Penn State University

❦

Joe Horowitz’s The Marriage portrays Mahler with more power and poignancy than anyone else ever has. Set in a spider web of New York City wealth, power, and intrigue, the writing is so pro- foundly personal, so searingly intimate, that it is sometimes painful to read – to get that close to Mahler and his wife Alma – “the most beautiful woman in Vienna.” I found myself unable to resist reading passages several times. This is a book for people who love Mahler and long to know him intimately (and there are millions) – a truer, more human Mahler than we have ever before encountered. Alma is also fabulously drawn, with all her love and antipathy towards her husband.

JoAnn Falletta, Music Director, the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra

❦

Persuasive and fair. It is refreshing to see this chapter of Gustav Mahler’s biography from an American perspective, written by someone not automatically biased in favor of Europe.

Karol Berger, author of Beyond Reason: Wagner contra Nietzsche; Osgood Hooker Professor in Fine Arts, Stanford University

April 30, 2023

Mahler vs. Anton Seidl — “All the Things that Mahler Wasn’t”

Yesterday – the publication date for my novel The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York – I had an enthralling video exchange with Morten Solvik of the Mahler Foundation in Vienna. You can see it here.

Some highlights:

3:24 – “You can’t understand the story of Mahler in New York without first understanding what went on there before he arrived – something Mahler himself never understood. And this was noted and resented. . . When Henry Krehbiel called Mahler’s American career a ‘failure,’ this was a comprehensible verdict.” Mahler’s New York predecessor Anton Seidl – who makes Krehbiel’s verdict comprehensible – “was all the things that Mahler wasn’t”: an American citizen who summered in the Catskills, who befriended the American composer, who assumed a mantle of cultural leadership.

6:18 – Henry-Louis de La Grange, Mahler’s most prominent, most copious biographer, came to graciously understand Seidl’s significance — “I took him aside and told him about Seidl. But he could never overcome his antipathy to Henry Krehbiel.” The New York music critics, generally, were far more sagacious than de La Grange allowed. “Their reviews of Mahler the conductor retain credibility.”

9:25 – Re: historical fiction: my first experiment was in my young readers’ book Dvorak in America (2003). “I had acquired a very intimate relationship with Seidl” via the un-catalogued archives at Columbia University and the Brooklyn Historical Society , handling his letters, his memorabilia, even speeches written in pencil. “It was a bewitching experience.” Evoking Seidl conversing with Dvorak at Fleischmann’s Cafe, “I actually knew what he would say.” I discovered that “I could learn things writing historical fiction, that it’s a very special tool for the cultural historian. . . . In some ways The Marriage is more like ‘creative non-fiction.’ It hews closely to events that actually occurred.”

10:07 – “My fundamental sense of Mahler is of someone who lives inside his head. There’s nothing wrong with that if you’re a composer – but it’s not so great if you’re the music director of an orchestra.” Dvorak, in comparison, at all times absorbed his environment; it was “inevitable that he would write a New World symphony – and inconceivable that Mahler would do so. . . . He never researched American music. it was obvious that he hadn’t done his homework.”

18:00 – Mahler at the Met: his innovations – importing Alfred Roller’s Fidelio production, treating Mozart as ensemble opera – were “striking, new, and successful – but ephemeral.” “They didn’t take.”

25:00 – The Mahler sonority: “everything in your face, a flat perspective like a Klimt canvas, a new conception of symphonic sound.”

30:00 – “People who write about Mahler in New York only see what happened just before he came – a period of institutional decline. . . . This is so poorly done.” Also: virtually unnoticed is that Mahler never complained at about his orchestra at the Metropolitan Opera – “and that was the New York orchestra that most mattered, not the New York Philharmonic.” Also unnoticed: New York City was regularly visited by the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Arthur Nikisch. “That’s a really high standard.” A crucial factor was Henry Higginson, “a mind-boggling figure” who invented, owned, and operated the Boston Symphony. “You spend some time with Higginson – it’s just humbling. . . . It’s something that’s unheard of today – a person of this stature running an orchestra.” Compared to the New York Philharmonic’s Mary Sheldon – “night and day.” And Seidl, too, had a Higginson. This was Laura Langford, Brooklyn’s leading impresario. “Something Mahler never had.”

42:00 – Henry Krehbiel – “the elephant in the room,” “the greatest figure in the history of American musical journalism.” “You can’t know Mahler in New York without knowing Henry Krehbiel – and Mahler’s biographers don’t know Henry Krehbiel.”

49:00 – “Alma [Mahler] is someone who doesn’t really know who she is or what she wants.” In a new environment, unlike her husband [in his hotel room], she’s “exploratory.” She reveals herself “in juxtaposition with women more professionally accomplished than herself . . . when situated in a room with Olive Fremstad or Natalie Curtis.”

1:05 – Snapshots: Mahler vs. Toscanini; Mahler and Ives

Anton Seidl is the core topic of my book “Wagner Nights: An American History” (1995).

My thanks to Morten Solvik, Thomas Hampson, and the Mahler Foundation. Stay tuned for Thomas Hampson reading from “The Marriage.”

April 25, 2023

Mahler vs. Toscanini — and this Saturday’s “Mahler Hour” on Zoom

“How would you compare Mahler and Toscanini in New York?” asked Kenneth Wood, Artistic Director of Boulder’s Colorado MahlerFest, in a zoom conversation a few days ago about my new novel: The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York (the official pub date is this Saturday).

You can see and hear my answer here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wXCgIWXRoqk

You can also hear me in conversation with Morten Solvik of the Mahler Foundation on “The Mahler Hour” this coming Saturday at 10 am ET by tuning in here: https://www.youtube.com/c/MahlerFoundation

If you want to know what I said about Mahler and Toscanini without bothering with the link, I said this:

Mahler was displaced at the Metropolitan Opera by “an Italian juggernaut.” “Mahler didn’t care to investigate the New York musical situation he encountered in 1907. This got him into a lot of trouble and signifies, I would say, his most striking personal trait – that he lived inside his head. And that’s fine if you’re a composer. It’s not so great if you’re a music director.”

As for Toscanini – “Unlike Mahler, you couldn’t oppose him. If Mahler was opposed he’d get upset. If Toscanini was opposed, he would just bulldoze over every adversary. And when he decided that he was going to appropriate the Wagner repertoire, Mahler fought a completely futile rearguard action before realizing that he was outgunned. Being rebuffed at the Met, he would up conducting the New York Philharmonic. . . Imagine these dueling personalities in New York, Mahler and Toscanini – that itself could be a book, but it’s never been written.”

Kenneth Woods: “Maybe that’s your own next book.’

JH: “I think I shot my wad in Understanding Toscanini in 1987. Whenever I return to that topic, there are still people around who get very upset,”

When asked to summarize my new novel (5:30), I reply: “It was a very taxing moment for this very odd couple. It’s an interesting context in which to observe Mahler and his wife – as newcomers.”

KW: “Who thrived more?”

JH: “That’s a mind-boggling question.” For Mahler (as for Toscanini, after World War I), New York signified among other things an opportunity to conduct symphonies – something he couldn’t much do in Europe. As for Alma: “Things are here even more complicated. She’s much harder to read than her husband because she’s someone in a state of internal confusion about who she is and what she wants. Did New York clarify this for her? I don’t think so. I would say this: at least for me, her most revealing moments are when she finds herself in the presence of a woman more professionaly accomplished than herself. You know, you learn things when you write historical fiction.” In my book, in the presence of the soprano Olive Fremstad, and of the fledgling ethnomusicologist Natalie Curtis, Alma “realizes what she wasn’t.”

KW (at 10:17): “In writing a historical novel, where are the borders between fact and fiction?”

I here distinguished between “historical fiction” and “creative non-fiction.” I add: “My book is two things – it’s a novel and it’s also the first book-length treatment of the Mahlers in America – a topic that’s been murdered because everybody who writes about it knows next to nothing about New York.” Mahler’s New York “was a world music capital” in which Anton Seidl and Antonin Dvorak, dominant in the 1880s and 1890s, cast long shadows. And there was Mahler’s nemesis, the critic Henry Krehbiel, who quite accurately declared Mahler’s New York tenure “a failure.” An initial crisis (13:35): When, as the Philharmonic program annotator, Krehbiel asked permission to print Mahler’s program for his First Symphony, he wound up writing a program note disclosing that Mahler forbade program notes. “Their relationship deteriorated after that.”

KW (at 15:20): Did the ‘factionalized” music critics in Vienna influence Mahler’s standoffish behavior towards Krehbiel and other New York critics?

JH: “American music criticism is a species unto itself – especially in this period, when it’s at its apex.” Krehbiel and others filed their reviews immediately — they appeared the next morning. This practice was unknown abroad. Also: “As Mahler may or may not have noticed, there was no anti-Semitism in the New York musical press.”

To close on a note of controversy (18:40), I opine that those Viennese critics who called Mahler’s music, and even his interpretations, “Jewish” were “not necessarily anti-Semitic.” I here reference Arthur Farwell’s remarkable blow-by-blow review of Mahler’s Mahleresque reading of Schubert’s Ninth Symphony with the Philharmonic, in the Musical America — a crucial text for my treatment of Mahler in performance in The Marriage..

–I speak at the Boulder’s Colorado MahlerFest symposium on May 20.

–My “Mahlerei” for bass trombone and chamber ensemble will be performed at the Brevard Music Festival on July 5 (with sui generis soloist David Taylor).

–My “Einsamkeit,” re-imagining songs by Maher and Schubert (also with David Taylor), will be performed at New York City’s Peridance Center on June 17 and 18, with choreography by Igal Perry.

April 24, 2023

“Shostakovich in South Dakota” on NPR — A New Template for Orchestras

My NPR “More than Music” program “Shostakovich in South Dakota” can now be accessed here.

I document the impact of a remarkable contextualized performance of Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony by Delta David Gier and his singular South Dakota Symphony last February – and ponder its significance for the future of embattled American orchestras striving to retain pertinence today. Shostakovich’s symphony was composed during the Nazis’ strangling 872-day siege of Leningrad.

Here are a few excerpts from the show:

“For Mark Bertrand, the pastor of Sioux Falls’ Grace Presbyterian Church, Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony evoked the resilience of Ukrainian resistance to Russia’s invading army in 2023. Bertrand also found himself thinking about the role of culture in a nation’s life. ‘It’s striking that as the symphony was being composed, Shostakovich was updating people in real time about his progress. They were looking forward to this happening. And it can’t be the case that this besieged population was just seeking some entertainment to get their thoughts off their everyday reality. I tried to imagine us today feeling a similar kind of anticipation for an artistic statement. We don’t value things the way they did. It really gets you thinking about how different their values must have been.’ . . .

“As Shostakovich’s symphony began its slow, inexorable ascent toward a final climax, Bertrand found himself thinking about a German soldier whose words were quoted earlier in the evening. The Russians not only broadcast the Leningrad Symphony throughout the Soviet Union. They managed to broadcast it via loudspeakers to the Nazi troops blockading Leningrad. After the war, a German soldier testified: ‘It had a slow but powerful effect on us. The realization began to dawn that we would never take Leningrad. We began to see that there was something stronger than starvation, fear and weather – the will to remain human.’”

Another participant in the NPR program is the New Yorker’s Alex Ross, who says:

“There’s just a tremendous amount of caution, a tremendous amount of groupthink, in the orchestra world. So to see an orchestra really out on its own, forging its own identity, and bringing its audience along with it is just extremely impressive – even more impressive than I anticipated. . .

“For a music director to carry off an ambitious project, you have to be there. You have to be on the scene, persuading people, interacting with them, listening to their ideas. Not just communicating your own. Building a sense of cooperation. You cannot do that as effectively if you’re flying in for two or three weeks, and another couple of weeks in the winter, and another two weeks in the spring. I find it a bit outrageous that music directors are so highly paid to begin with for one job – and then you find them holding a second or even a third position with exorbitant salaries in those places as well. This, of all things, is something the orchestra world should really be thinking about: drastically revising our idea of who a music director is, what their job entails.”

The South Dakota Symphony’s performance of the Leningrad Symphony was elaborately partnered by South Dakota State University. Reflecting on dropping enrollments in the Humanities, David Reynold’s, director SDSU’s the School of Performing Arts, says: “I realize that in some high school curricula today the story of World War II may be only a week. I think that finding a way to use the performing arts to bring this kind of story to life is a wonderful opportunity to touch students who are growing up with social media and other non-traditional resources. Students in our Music Appreciation classes – those are the folks that one of these days will be bank presidents, school board presidents, and will decide the role of the arts in public and private schools. It’s very important for them to have experiences just like this one – Shostakovich and the siege of Leningrad. To get them thinking that life would be incomplete without the arts being a part of it.”

I also explore the South Dakota Symphony’s signature Lakota Music Project, which connects SDSO to Indian reservations throughout the state, and about which SDSO principal second violinist Magda Modzelewska says: “In Indian culture we’ve found such peace and good will. It’s truly remarkable how similar our musical goals are. We get to share something sublime.”

This story of an orchestra that does just about everything different seems to me so important to the future wellbeing of the American arts that I’m generating a 6,000-word “manifesto,” scheduled for future publication by The American Scholar.

A listening guide to the 50-minute broadcast follows.

PART ONE: The Leningrad Symphony

3:15 — About the symphony and the siege

5:45 — Mark Bertrand on experiencing the Leningrad Symphony

7:10 — Magda Modzelewska on performing Shostakovich

PART TWO: The Lakota Music Project

12:04 — “Wind on Clear Lake” by Jeffrey Paul

14:20 — Delta David Gier on the history of the Lakota Music Project

20:12 — Lakota flutist Bryan Akipa

23:10 — The Composition Academies

25:45 — Arthur Farwell and “Pawnee Horses”

27:10 — Farwell’s “Hako” Quartet

PART THREE: The SDSO as a Model

30:00 — The bedroom scene from Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth

34:00 — The Shostakovich Eighth Quartet on campus

37:00 — David Reynolds of South Dakota State University on collaborating with SDSO

39:15 — Alex Ross on the SDSO and the future of orchestras-

April 20, 2023

“Drastically revising our idea of who a music director is” — The South Dakota Symphony on NPR

The Creekside Singers performing with the South Dakota Symphony

“There’s just a tremendous amount of caution, a tremendous amount of groupthink, in the orchestra world. So to see an orchestra really out on its own, forging its own identity, and bringing its audience along with it is just extremely impressive – even more impressive than I anticipated.”

That’s Alex Ross, of The New Yorker, discussing the South Dakota Symphony in my upcoming NPR “More than Music” program: “Shostakovich in South Dakota,” which airs via WAMU’s “1A” newsmagazine this coming Monday at 11 am ET. Referencing Delta David Gier, who has been the South Dakota Symphony’s music director since 2003, and who moved to Sioux Falls and raised his family there, Ross continues:

“For a music director to carry off an ambitious project, you have to be there. You have to be on the scene, persuading people, interacting with them, listening to their ideas. Not just communicating your own. Building a sense of cooperation. You cannot do that as effectively if you’re flying in for two or three weeks, and another couple of weeks in the winter, and another two weeks in the spring. I find it a bit outrageous that music directors are so highly paid to begin with for one job – and then you find them holding a second or even a third position with exorbitant salaries in those places as well. This, of all things, is something the orchestra world should really be thinking about: drastically revising our idea of who a music director is, what their job entails.”

Ross told me he had long considered visiting South Dakota to see for himself what Delta David Gier was up to – programing quantities of new music, regularly tackling big repertoire. The focus of my NPR show is Gier’s contextualized performance of Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony last February, with linkage to South Dakota’s two major universities. I also explore the symphony’s signature Lakota Music Project, which connects SDSO to Indian reservations throughout the state, and about which SDSO principal second violinist Magda Modzelewska says: “In Indian culture we’ve found such peace and good will. It’s truly remarkable how similar our musical goals are. We get to share something sublime.”

April 18, 2023

Five Festivals for the Charles Ives Sesquicentenary

The National Endowment for the Humanities today announced a $400,000 grant to resume “Music Unwound,” a national consortium of orchestras and universities, begun in 2010, that explores topics in American music. I serve as director.

Music Unwound disseminates a template I have long espoused: thematic, cross-disciplinary symphonic concerts linked to schools. I believe it represents the future – and that the sooner we come to it, the sooner we can fortify an arts species today embattled: the American orchestra.

Three Music Unwound themes are now in play: “The Souls of Black Folk” (showcasing William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony), “New World Encounters” (about jazz abroad), and “Charles Ives’ America.” The participating institutions are the Brevard Music Festival (lead partner), the Jacobs School of Music at the University of Indiana/Bloomington, the Chicago Sinfonietta (partnering Illinois State University), the South Dakota Symphony (partnering two universities), the Blair School of Music (Vanderbilt University), and The Orchestra Now (Bard Conservatory/College).

Five of the nine Music Unwound festivals will be multi-event Ives celebrations targeting the Charles Ives Sesquicentenary in 2024. As I have often written: this is a crucial moment for the American symphonic community, if we are ever to secure a “usable past.” The core participants include the Ives scholar Peter Burkholder, the baritone William Sharp, and the historian Allen Guelzo. The NEH Music Unwound application puts it this way:

“This project creates a fresh approach to an iconic American widely regarded as America’s supreme concert composer, yet little-performed because his music retains an esoteric taint. In part, this results from its belated discovery (ca. 1940-1960, long after Ives had ceased composing) by modernists who cherished complexity. Today, in post-modern times, the opportunity is ripe to rediscover Ives as a turn-of-the- century Connecticut Yankee rooted in Transcendentalism and Progressivism — a product (however idiosyncratic) of his own time and place. Ives’s vivid personality, and a plethora of memorable writings (essays and letters), reinforce this opportunity to better acquaint American audiences with the Ives idiom — to penetrate its assaultive exterior and connect to its heart and soul. The MU project creates a permanent set of tools — scripts and visual tracks — that orchestras and presenters can use to nudge Ives into his rightful place in the mainstream repertoire. . . .

“Ives is a quintessential musical Progressive, zealous in his faith in democracy, the common man, and the former slave. No less than Mark Twain, he pioneered in fostering an American idiom boldly appropriating vernacular expression (for Twain, Huck Finn’s dialect; for Ives, quotidian New England strains). Both were self-reliant New World creators. Both empathetically tackled issues of race. The Twain/Ives relationship is a sub-theme of “Ives’s America.”

“Part two of the central symphonic program is a contextualized performance of Ives’s Second Symphony. It furnishes an ideal introduction to the composer, readily accessible as a Germanic Romantic symphony. At the same time, Ives is already rambunctiously American. As Peter Burkholder (who helped to create “Charles Ives’s America”) writes in his seminal Ives study All Made of Tunes, Ives here achieves a distinctive voice “by using American material, and by emphasizing allusion and quotation…. Borrowed material appears on almost every page…to create a symphony that is suffused with the character of American melody.” Via the parlor and salon, Ives identified with hymns and minstrel tunes; via the organ loft, he identified with Bach; via his father and his Yale composition professor Horatio Parker, he identified with Beethoven and Brahms. That all of these influences intermingle in the Second Symphony, that all are equally audible and equally privileged, creates a musical kaleidoscope more multifarious than any by Mahler. Ives’s egalitarian ethos, and the ethos of uplift, are equally served.

“With its myriad source tunes, Ives’s Second is a prime candidate for contextualization — and the Music Unwound performances are directly preceded by a performance (baritone/piano) of selected marches, songs, and hymns that Ives integrates, with pertinent commentary — illustrating, for instance, how an inane college song becomes the lyric second subject of movement two, and how the “Civil War” finale celebrates the freeing of enslaved Americans. It bears stressing that most of the tunes Ives uses are no longer familiar.

“Part one of the symphonic program features Ives’ Three Places in New England, the first of which is a “death march” commemorating Colonel Robert Shaw’s heroic Black Civil War regiment, as famously memorialized by the sculptor Augustus St. Gaudens. This is an example of an important Ives composition that no new listener could possibly “read” without some help.”

No dates yet — stay tuned.

P.S. — My warmest congratulations to Jason Posnock, one of the nation’s premier artistic administrators, who was just named incoming President of the wonderful Brevard Music Festival. And best wishes to Mark Weinstein, the outgoing President, who raised the fesitval’s profile and greatly expanded its resources.

April 16, 2023

Rediscovering Harry Burleigh: A Valedictory Setting of Langston Hughes

In recent weeks I’ve had occasion to perform Harry Burleigh’s “Lovely Dark and Lonely One” with three singers: Emery Stephens at St. Olaf’s College, George Shirley for Chamber Music Cincinnati, and Sidney Outlaw at Princeton University. And I write in this weekend’s Wall Street Journal that this “may be credibly judged one of the most memorable of all American concer songs.’” In fact, I argue, it may be understood as Burleigh’s 1935 valeictory, a song (setting but re-interpreting Langston Hughes) about Burleigh himself, preaching faith and forbearance. The recordings I have encountered of this song seem a little small to me; I hope to be able to post the Cincinnati or Princeton performance in the coming weeks. That said, you can listen to a lovely reading here.

I write in part:

Burleigh (1866-1949) is the pivotal figure in the transformation of the spirituals of the American South into solo concert songs. You might even say that black classical music begins with the five versions of “Deep River,” for solo voice or chorus, that Burleigh created between 1913 and 1917. Their impact was electrifying. . . . He [also] became a prolific composer of art songs distinct from his arrangements of spirituals. This body of music was exceptionally popular into the 1920s, championed by John McCormack . . . and other prominent recitalists of the day. Burleigh’s spirituals are still widely sung. But beginning in the late 1920s, his art songs swiftly receded from view. In the context of modernism, of the Harlem Renaissance and its enthusiasm for jazz, Burleigh sounded old-fashioned. . . .

Re-encountered today, this late song seems a valedictory. Only two minutes long, it is—even for Burleigh—a superb exercise in concentration: of mood and expression, of melody, of mobile harmonic activity. It achieves a compositional voice as personal as his spiritual arrangements are elemental. The piano part, virtually symphonic, is co-equal with the voice, with which it eloquently interacts. The mediation between black (bluesy harmonies) and white celebrates the duality of Burleigh the man and artist. Nowhere is Burleigh closer to Wagner; he virtually quotes the Prelude to Tristan und Isolde—an opera he attended 66 times at the Met. But the most distinguishing feature of this exceptional song is that Burleigh has re-interpreted Hughes’s poem . . .

Processing Hughes’s expression of impatience, Burleigh turns the poem upside down. His method is to first score the closing word, “wait,” as an exclamation crowning the vocal line—and then to twice reconsider it, softening and caressing it so that the meaning turns serene: an expression of forbearance and faith. He then reprises the poem’s first two lines . . . so that the final quiet melodic ascent consecrates youth and sunlight. In this 12-bar sequence, it is the intervening piano that becalms the singer, claiming a lasting philosophic repose. Not for Burleigh is Langston Hughes’s agitation, or the activism of a Paul Robeson. Nor is there the merest hint of modernist dissonance. We do not have to agree with him in order to admire the eloquence with which he here sustains his credo . . . that “deliverance from all that hinders and oppresses the soul will come and man—every man—will be free.”

Burleigh intended “Lovely Dark and Lonely One” for Marian Anderson, whom he mentored, and whose renditions of Burleigh’s “Deep River” were indelibly her own. But Anderson chose not to sing “Lovely Dark and Lonely One.” It is in fact a song personal to Harry Burleigh. It also happens to be Burleigh’s final concert song. If he therefore quit composing art songs at the peak of his creative powers, his truncated odyssey bears comparison to other, more famous casualties of modernism: Charles Ives, Edward Elgar, Manuel de Falla and Jean Sibelius, all of whom stopped composing when they discovered themselves aesthetically estranged after World War I. . . .

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers