Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 14

May 31, 2022

“How I Wish We Had Something Like That Today”

Fill in the blanks:

“This was performed and broadcast to millions of people. And something that should resonate with all of us today is the confluence of fine art and popular art and a mass medium – something we’ve lost in this era, when we’re being sliced into ever narrower shards of demographics. The brilliance of what xxx and xxx did was to embrace all of us, in the best [Walt] Whitman spirit. To make all of us one nation, one community. How I wish we had something like that today.”

The blanks read “Bernard Herrmann” and “Norman Corwin.” The speaker is Murray Horwitz, former head of cultural programing for National Public Radio. And the source is my latest “More than Music” NPR documentary, broadcast yesterday. Its topic: the radio plays of the 1930s and 1940s generally, and the Corwin/Herrmann “Whitman” (June 20, 1944) specifically.

To hear yesterday’s 50-minute show, click here.

Following Murray’s lead, I chime in to suggest that “Whitman” (starring Charles Laughton, music by Herrmann, scripted and produced by Corwin) was “an act of democratic faith in a democratic American audience,” achieving “a kind of optimum engagement, reaching the largest possible audience without diluting Whitman’s verse. We’re very far from that ideal in today’s world of social media.”

Here again is Murray, from the same show: “Radio was IT – the only broadcast medium. And there were only four national networks. So pretty much everybody in the country was listening to the same stuff.” And the stuff was a product of live commercial broadcasting, often presented non-commercially without ads.

The further pertinence of “Whitman” is inescapable. He espoused inclusive American ideals. He healed the ripped national fabric after the Civil War.

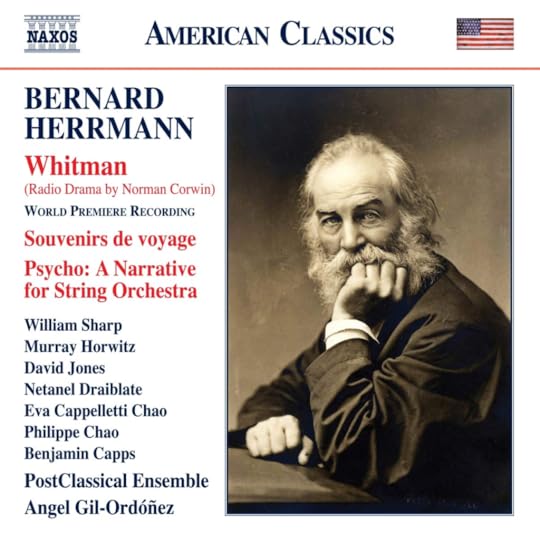

Does the Herrmann/Corwin “Whitman” matter today? In effect, it’s a 30-minute composition for narrator and orchestra, awaiting attention. The baritone William Sharp, who takes the part of Whitman in the PostClassical Ensemble “Whitman” recording on Naxos, says: “It speaks to us so strongly,” a “magically wonderful thing” to hear were orchestras to program it.

(Herrmann is part of the “new paradigm” – the new narrative for American classical music – that I propose in my book Dvorak’s Prophecy. I continue to regard him as the most under-rated 20th century American composer. Why aren’t our orchestras programing his Moby Dick cantata? It’s certainly not because Herrmann doesn’t sell. We’re talking about the composer of Psycho, Vertigo, and Citizen Kane.)

The participants in yesterday’s radio show, in addition to Murray and Bill, include Alex Ross of The New Yorker (a huge Herrmann fan) and the Whitman scholar Karen Karbenier.

The next “More than Music” NPR documentary will air July 4. The topic (tracking Mark Clague’s superb new book) is the unlikely history of the “The Star-Spangled Banner” – which we’ll hear performed by Jimi Hendrix, Whitney Houston, and Jose Feliciano, among others. And we’ll sample verses you’ve never heard before.

Again, my thanks to Rupert Allman and Jenn White of WAMU’s “1A” for believing in what Rupert calls “long-form radio.”

A “listener’s guide” follows:

00:00 – We start with the shower scene from Psycho, “to get everyone’s attention.”

2:30 – Orson Welles and the birth of radio drama: “The War of the Worlds”

8:07 – Bernard Herrmann hypnotically sets Whitman’s paean to the grass — “handkerchief of the lord” – consecrating the young Civil War dead.

12:30 – Herrmann’s unforgettable invocation of “America the Beautiful,” a “teeming nation of nations.”

15:50 – Whitman and Herrmann extol a great democratic citizenry, “immense in passion, pulse, and power.”

19:57 – Murray Horwitz: “Radio was IT.”

21:12 – Radio’s biggest star: FDR. The first “fireside chat.”

24:29 – Whitman’s “radical vision of democracy” explored by Whitman scholar Karen Karbinier (“He strikes a perfect balance between individuality and community”).

31:29 – Dorothy Herrmann describes her notoriously irascible father reacting to a prelminary screening of Psycho (“Did you ever see such a piece of crap?”).

32:54 – Herrmann’s sublime Clarinet Quintet, featuring clarinetist David Jones.

39:04 – Alex Ross on Herrmann (“one of the most original composers of any century,” “a very great talent, one that we’re still very far from appreciating and celebrating in full.”

To purchase a related Bernard Herrmann DVD (“Beyond ‘Psycho’”), click here.

May 24, 2022

What Museums Can Do and Orchestras Cannot Do

Winslow Homer: “Lost in the Grand Banks”

Winslow Homer: “Lost in the Grand Banks”I keenly anticipated the Metropolitan Museum’s current Winslow Homer retrospective. Titled “Cross-Currents,” it comprises 88 oils and watercolors, a 200-page scholarly catalogue, a “visiting guide,” an audio guide, and docents readily at hand. The driving aspiration is to newly frame a major nineteenth century American painter, with due regard for our current wrestlings with issues of American purpose and identity.

In short – it is a necessary exercise in curating the American past, something our museums do and our orchestras do not.

As I write in Dvorak’s Prophecy, cities (I mention Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, New York, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh) whose art museums “regularly scrutinize the American cultural narrative” host orchestras innocent of this endeavor. And I specifically cite a 2018 Metropolitan Museum exhibit tracing the lineage of the painter Thomas Cole, adding:

“Were an orchestra to do something similar, it might be a contextualized presentation of the symphonies of John Knowles Paine (1875, 1879) – crucial progenitors of the American-sounding Second and Third Symphonies of George Chadwick. I would not call Paine a ‘great composer.’ But he is a great and necessary figure in the history of American classical music. American orchestras do not even know him.”

Were an American orchestra to “do something similar” to the Met’s Winslow Homer retrospective, it would be a celebration of our greatest symphonist: Charles Ives, whose 2024 Sesquicentenary is nearly upon us. Will anything like that take place? There is a tool kit at hand: the “Brevard Project” this July. It’s a week-long think tank/seminar exploring the ways American orchestras can “use the past” to serve the nation and reinvigorate their mission..

***

Devouring the Winslow Homer galleries, I was impelled to recall the 1895 Civil War oration of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., with the immortal words: “Through our great good fortune, in our youth our hearts were touched with fire. It was given to us to learn at the outset that life is a profound and passionate thing.”

Self-made, virtually self-taught as a painter, Homer (1836-1910) apprenticed to a commercial lithographer at nineteen and became a frequent illustrator for Harper’s Weekly and Ballou’s Pictorial. He was all of 25 years old when the Civil War erupted. He became its most memorable painter. This singular apprenticeship “touched with fire” powered his destiny with gathering force. He seized the elemental – and, with his signature seascapes, became the recorder of man at war with his surroundings in an indifferent world. Many an iconic Homer canvas shows sailors at the mercy of a sullen sea. At the Met, I was galvanized by the existential power of “Lost in the Grand Banks” (1885), with its brooding and featureless gray sky.

The trope of the self-invented, self-made American artist figures prominently in Dvorak’s Prophecy. I apply it to Walt Whitman, Hermann Melville, and – most especially – to Ives. It connects to something as “unfinished” as the United States itself. The Met’s Homer retrospective documents years of renewal, but also – at least to my eyes – pronounced terminal decline. My impression is that his lack of formal technical training ultimately became a source of limitation.

Many years ago, an exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum cruelly juxtaposed the watercolors of Homer and John Singer Sargent. Homer was proud of his watercolors, and justly so. But Sargent’s command of this treacherous medium was sovereign. As a technician, he disclosed a virtuosity beyond Homer’s reach.

Seizing the Civil War, grappling with man’s war with the elements, Homer was an artist whose themes sometimes exceeded his means. And Sargent’s means can surpass his themes. It is in the music of Charles Ives – music still under-performed and under-recognized – that great American themes and uncanny, idiosyncratic means jostle in a wondrously dynamic equilibrium.

The Ives Sesquicentenary seems to me a make-or-break moment for our struggling orchestras.

May 16, 2022

Remembering Lexo

When I filed my eulogy for Alexander Toradze, one of the emails I received was from David Hyslop. The former CEO of the Minnesota Orchestra, he knew Lexo at home in Minneapolis and on tour. Hyslop remembered Toradze as a great talent – and an even “greater person.”

I was reminded, after a fashion, of a malicious review filed by a colleague during my New York Times tenure in the late 1970s. This was someone who loathed a Toradze performance. His review declared Toradze’s career over – he was a pianist no longer in demand by audiences or orchestras, the Times’ readers were informed. When I next encountered my colleague, I felt the need to inform him that I knew Alexander Toradze rather well, and that he was an “exceptional human being.” My colleague replied in a casual sing-song: “I’m sure that’s true.” This ended our exchange with the glib sentiment: So what? — it doesn’t matter. But it did matter, and it does.

In Fort Worth, in the wake of the 1977 Cliburn Competition, the local public TV station produced a thirty-minute film: “Lexo.” This was before the era of soundbites. The film ends with a nearly complete performance of Stravinsky’s Three Movements from Petrushka, documenting an interpretation so vividly characterized that more than a few pianists regard it is a benchmark. But the glimpses afforded of Lexo’s interaction with his host family, including two young children, are every bit as memorable. At the age of 25, the Toradze personality – its onslaught of warmth and wellbeing — was already as striking as Toradze the pianist.

In the wake of Lexo’s death, recorded concert performances are freshly turning up on youtube. One is the Tchaikovsky B-flat minor concerto, with David Atherton and the Hong Kong Philharmonic. This is from 1990 – the same year as the Prokofiev Third my son Bernie has flagged. Lexo’s mettlesome intellect is documented in fraught interaction with a volcano of feeling. It would be a pale understatement to characterize the old warhorse as re-animated by such inhabitation; Tchaikovsky can barely hang on.

In the irreplaceable living room of Lexo’s South Bend home – a room filled with memorabilia and photographs and above all with memories – I two days ago discovered an album of photographs of his mother. She was a famous Georgian film actress. (His father was the pre-eminent Georgian composer.) Liana is smiling and proud. She has her arm around young Lexo, perhaps ten years old – and his arm is around her. Lexo’s countenance also evinces love and pride. But he is not smiling. One clearly senses something exceptional about the object of his mother’s high regard – an autonomy of spirit, a maturity beyond his years.

How Lexo left his mother, father, and sister in 1983 is a story many times told. Touring with a Moscow orchestra in Spain, he was not permitted to perform. He had not been allowed to visit the United States, where he already had an excited and appreciative audience, for four years. Discovering himself in a Madrid restaurant without an escort, he impulsively sought asylum. A recent Russian posting quotes a newspaper interview from 2013 in which he says, “I never intended to leave anywhere, let alone run away . . . I broke down. It’s hard to believe, but it was a completely unprepared situation. I was thirty-one years old.” The Toradze odyssey, complex and unfathomable, may partly be read as evidence of the human cost of the Cold War.

The night he would die in his sleep, Lexo texted a smiling selfie with cigar to Vladimir Feltsman, a friend of many decades. He was in an expansive mood. Notwithstanding a recent heart episode, he was feeling robust. He had just been told that his cardiac readings were strong. He was actually on the mend from a period of poor health.

A related blog: Toradze on Stravinsky

May 12, 2022

Alexander Toradze 1952-2022

The pianist Alexander Toradze, who died yesterday of heart failure at the age of 69, was much more than a friend.

Lexo enjoyed telling the story of our first encounter – a story of American naivete. This took place in a small room at Carnegie Hall. He was touring as a Soviet artist; the year must have been 1979. The meeting was arranged by Mary Lou Falcone, the publicist of the Van Cliburn Piano Competition, in which Lexo’s second-place finish had stirred a national controversy. Mary Lou doubtless envisioned a lively exchange. I was eager to know how Alexander Toradze felt about the Soviet suppression of Alfred Schinittke and other “forbidden” Russian composers. He replied, without skipping a beat: “When was the last time John Cage’s prepared piano pieces were performed at Carnegie?” This took place in the presence of a man sitting silently in a corner – Lexo’s Soviet handler, of whom I was oblivious.

Lexo was in all things original. I have not met anyone more gifted at thinking while speaking – his remarks were never generic. For him, conversation was an art – doubtless a skill he acquired in his native Tbilisi, where toasting is a competitive creative act. Because his father was the leading Georgian composer, and his mother a prominent screen actress, he enjoyed access to the highest precincts of Soviet culture – including meetings of the Composers’ Union – at an early age. It showed.

In my book The Ivory Trade, I documented the youthful aplomb, the intensity of charm, of Lexo at full throttle at the 1976 Clibrun competition:

“Round-faced and pudgy, sociable, demonstrative, he was a born performer. Earnestly searching for an errant English word, he would purse his lips and knit his brow, and shut his eyes in a hard squint. In repose, his features turned vulnerably soft. Pleasure crinkled his eyes, puffed his cheeks, and stretched his mouth into a broad smile. . . .

“From the moment he sat down to play, Toradze was an adrenaline machine, arms ifidgeting, torso twisting, legs twitching, as he nervously glanced at the orchestra and the conductor. In action, eyes clamped, jaw clenched, he crowded the keyboard like a pugilist, bowing his head, curling his back, spreading his elbows. He beat time sharply with his left foot. His powerful hands, with their surprisingly long fingers, stood tall, tickling the keys or punishing them.

“Everything Toradze touched sounded different. His Bach was Gothic. His Haydn was relentless, formidably dour. He traversed a Scarlatti sonata in an eerie, mountful slow motion . . . “

Many years later, an attempt to implant Toradze in a documentary film for American public television proved a predictable fiasco. His discourse could not be captured in soundbites. A subsequent film by Behrouz Jamali recorded Lexo telling three stories over the course of one hour; it is the one to see.

The Toradze approach was not for everyone – or for all repertoire. Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto was one piece that could not survive a Lexo onslaught. I thought he made his deepest statement in Prokofiev’s Concerto No. 2, which he read – Lexo always needed a story – as a requiem for Maximilian Schmidthof, who committed suicide. This detailed reading – a traumatic narrative of loss — transforms and amplifies the music in surprising ways. In music, an “agogic” accent is achieved not via loudness, but a slight delay. In his commercial recording of this work, partnered by his lifetime friend Valery Gergiev, the tremendous agogic accent Toradze interpolates at 11:42 (just after the first movement cadenza), and which Gergiev thunderously absorbs, is not to be found on the page.

My son Bernie, who knows such things, believes Toradze’s supreme recorded performance is a 1990 version of the concerto he was practicing in the days preceding his death: Prokofiev’s No. 3, again with Gergiev. Hear it.

As a Moscow Conservatory student, Lexo listened clandestinely to the Voice of America “Jazz Hour.” He was not the only one for whom jazz signified American freedoms. Jazz informed Lexo’s thundering syncopations in Prokofiev and Stravinsky. Possibly his favorite story was meeting Ella Fitzgerald in Portland, Oregon. Touring as a Soviet artist in 1978, he discovered that Fitzgerald and Oscar Peterson were about to perform a Portland concert. When he refused to take a scheduled flight for a Miami rehearsal, his American manager, Shelly Gold, told him he was jeopardizing his career. Lexo stayed in Portand and wound up onstage with Ella Fitzgerald. He dropped to his knees and kissed her hands. He told her that she mattered more in Russia than she could possibly matter to any American. Her photograph was always on his piano. (A full telling of this story begins at 18:16 here.)

Once, during a panel conversation in Washington D.C., Lexo heard an American music historian sarcastically demean Tikhon Khrennikov. The longtime head of the Soviet Composer’s Union, Khrennikov was initially appointed by Stalin, whom he faithfully served. When the Khrennikov lecture was over, Lexo casually remarked: “I knew Khrennikov. I also knew his wife, who was Jewish.” Without heat, he redrew Khrennikov as a flesh and blood mortal, fending as best he could. It was a Woody Allen moment.

Like other Soviet emigrants I have known, Lexo looked back without illusions or ideological blinders. He saw no cartoons. But America – I must say — proved something less than he had hoped or expected.

His 1983 defection was characteristically novelistic. Touring with a Moscow orchestra in Spain, he was forbidden to perform. It was a last straw. He entered the American embassy and requested refugee status. Two days later, the orchestra’s concertmaster hung himself in a hotel bathroom. Russian intelligence agents attempted to kidnap Lexo in a restaurant. There were high-speed chases on Spanish highways. Three months later, he began a nine-city tour with the Los Angeles Philharmonic: his first American concerts in more than four years.

Lexo eventually wound up in South Bend, Indiana, occupying an endowed Piano chair at the University of Indiana there. This was not the big IU music school in Bloomington, but a much smaller operation looking for prominence. It seemed an incongruous move, but Lexo capitalized on the opportunity at hand and created a singular artistic phenomenon: the Toradze Piano Studio. Single-handedly, he recreated the intense mentoring environment he had known in Moscow, as well as the communal social life he had known in Tbilisi. Composed of students and former students, the Studio toured widely, especially abroad, purveying thematic festivals many of which I partnered. There were marathon programs of Shostakovich in Paris, Prokofiev in Edinburgh and St. Petersburg, Stravinsky in Rotterdarm, Rachmaninoff in Salzburg. For the Ruhr Piano Festival, the Studio performed the entire solo output of Alexander Scriabin as an eight-hour marathon.

Lexo’s suburban South Bend home was the site of innumerable gargantuan dinners and post-concert parties. His Russian and Georgian students ate pizza, played basketball, and barbecued salmon in their backyards. They shopped for steak and vodka in the early hours of the morning in vast twenty-four hour food marts. It was all a testimony to Lexo’s personal magnetism; the warmth of his nature, his depth of experience.

In my book Artists in Exile I reported Lexo observing in 2006:

“From the standpoint of nourishing cultural needs, South Bend may not be the ideal place for young artists to grow up. And it may not be true that we actually enjoy in this country all the ‘open society’ benefits that we’ve been told about. But for my generation – in Soviet Russia, at the Moscow Conservatory and also in Tbilisi – this notion of American freedom is still powerful, and I’m sure it’s still powerful for the world at large. . . . Willis Conover’s jazz hour on the Voice of America — that was the talk of my generation and also of my parents’ generation. Of course you were in danger if you listened to these broadcasts. We often listened in a basement, where an older friend of ours had a very powerful shortwave receiver. That gave us a sense of freedom. Then life goes by and you actually get to this country and you carry this notion with you, even if you grow disappointed. Even if everyday life can be pretty harsh and difficult, still that can’t spoil the dream. It’s a dream so strongly associated with your youth that you’re just saturated with it. You can smell it, taste, it, touch it. You can’t kill it and you don’t want to kill it. This dream is one of the things that bonds our group, in America. It’s a condition of hope associated with a faraway place. It’s actually a dream stronger than any reality. . . .

“I mean, I can’t envision a group of perforemers in which 80 per cent are not native born succeeding anywhere else. Can you imagine something like that in Russia? In Germany? In France? You need an open, accepting environment, you need the attitude: ‘Let it be.’ I feel this in South Bend.”

But it’s all gone now, and not only because Lexo himself is gone. Lexo’s odyssey was as complex and unfathomable as Lexo himself.

***

In Behrouz’s film, Lexo performs Prokofiev’s Seventh Piano Sonata in a manner unknown to Prokofiev and yet conveying its own kind of truth. Lexo’s interpretation is wholly invested in the experience of wartime – of Prokofiev and World War II. The first movement is reconceived without barlines, as if improvised in the heat of the moment. Its second theme, with repeated notes, is for Lexo “drops of tears.” The entire second movement is performed with the soft pedal down. The finale is performed without pedal.

In The Ivory Trade, Lexo says: “l can’t just look at a score and think: ‘Gosh, what a beautiful concerto; I’m going to make it just delicious.’ That doesn’t interest me. Composers, if they are expressing something, they do it because they cannot express it in other ways, because there is something they need to get out of their system. You don’t need to get out of your system pure happiness and joy. You need an element of discomfort, or irritation . . . That’s where our real differences are – in pain. Tolstoy, at the beginning of Anna Karenina, says, ”All happy families resemble one another; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” So I have to find this element. I have to find two or three pages of pain. Then I use that, because I can associate with that, and elaborate. I can use my own experience. And fortunately, my own experience with pain is quite considerable.”

In Behrouz’s documentary, I comment that Toradze interprets the Prokofiev Seventh Sonata via a process of “infiltration” of thought and feeling. “You can’t just surrender to the composer,” I suggest, “or you surrender yourself.” Referencing the scenarios he adduces in this sonata, and also in Beethoven’s Op. 109, I further tell him: “It’s not important whether your story is true. It’s true for you. It’s an instrument of interpretation; it lets you inhabit the music.” In the interpretation of music, there are different varieties of “fidelity” and “authenticity.”

Lexo possessed a special capacity to extract subjective truths binding his personal experience with notes on a page. Essentially, it was a special capacity to probe himself.

Lexo was like a brother to me and to my wife Agnes. He was like an uncle to my two children. I count knowing him, for more than four decades, among the most privileged experiences of my life.

April 14, 2022

Silvestre Revueltas, Arthur Farwell, and the “New Paradigm”

Every once in a while a review comes along that eloquently affirms the convictions inspiring a book or recording – even though the convictions in question may not be widely known or held.

I’m thinking — gratefully — of two Naxos CDs I’ve recently produced, as received by Nestor Castiglione in Music Web International and by Curt Cacioppo in the same publication as well as via his own blog. The music is by Silvestre Revueltas and Arthur Farwell — composers I extol as part of my “new paradigm” for American classical music in Dvorak’s Prophecy.

Revueltas’s Redes is (alas) not an especially famous film score – but it’s one of the most galvanizing ever composed. Reviewing the new Naxos world premiere recording of the complete Redes music, performed by Angel Gil-Ordonez and PostClassical Ensemble, Castiglione writes:

“It is as welcome a revelation as can be hoped, permitting the listener to finally grasp the unfettered breadth of Revueltas’s genius. Like Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich, and Bernard Herrmann, Revueltas crafted evocative music that not only blended with and augmented on-screen action, but managed to create its own self-sustaining logic and structure . . . a dazzling symphonic fresco that displays Revueltas’s imagination in full flight.”

Contrasting Revueltas with Aaron Copland, whose music for The City is recorded on the same disk, Castiglione observes:

“The Mexican was intuitive, earthy, and intemperate, the last trait contributing directly to his tragically short life and even shorter creative career. The American, on the other hand, was calculating, urbane, and restrained. Where they coincided was in their sympathy for the political left, each taking up pen and score paper to agitate for what they believed to be a better tomorrow, and in their shared appreciation of the emerging importance of cinema in helping to convey their message to a mass audience.”

Cacioppo’s reviews are of Arthur Farwell’s Hako String Quartet – also a world premiere Naxos recording, with the Dakota String Quartet:

“In his Op. 65, Farwell surpasses all previous efforts, including his own, at attempting . . . cross-cultural coalescence. The process and result seem sui generis until we encounter, a generation later, a Native composer who conversely embraced Western musical tradition: Louis Ballard (1931-2007). Ballard, part Quapaw and part Cherokee, was descended from chiefs on both sides of his family, and grew up learning the cultural practices of his people. At the same time, he pursued a musical path of study at the University of Tulsa with Béla Rózsa, and a career that took him to New York City and the celebrated capitals of Europe. Louis felt himself at once an avowed post-Schoenbergian and thoroughly Indian. Ultimately he said, pointing to one of his scores, ‘This is not Native American music or any type of music other than “Louis Ballard music.”’ Now that we are finally able to hear and take measure of Farwell’s Hako quartet, and reflect upon its genesis and intent, it becomes clear what exact counterparts he and Ballard are in historical relation to each other, each searching for synthesis, each writing his music, each shining a light toward compositional advancement. The parallel conjures up the Hopi twins at the North and South poles, who keep the planet rotating. Each composer takes the cultural inheritance bequeathed and entrusted to him and pools it with resources of the other in an effort to define his individual artistic identity, consequently widening and enriching the art.”

In fact, all the music here – Revueltas’s Redes, dignifying rural fishermen ensnared in a punitive market economy, Copland’s The City, proselytizing for a workers’ paradise, Farwell’s Hako, celebrating Native wisdom – seeks to “widen and enrich.”

Here’s a pertinent film: Redes Lives!

Here’s a pertinent National Public Radio documentary on “Mexico’s most famous unknown composer.”

Here’s a pertinent film about Copland, populism, and the Red Scare.

April 11, 2022

The Brevard Project — A Call to Action

I frame my book Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music as a call to action.

It ends: “If American classical music — our performers and institutions of performance, our conservatories, our agencies of philanthropy — can awaken to the moment at hand, classical music in America may yet acquire a vital future, at last buoyed and directed by a proper past.”

I’m talking about counteracting a condition of “pastlessness” – a failure to explore American cultural roots, a need to pursue a more inclusive American musical narrative. It’s all in my book.

For as long as I can remember, American orchestras have been chastised about a failure to innovate. The response, by and large, has focused on fund-raising, marketing, and board development. But the challenge at hand is not about selling tickets. It’s about re-thinking artistic practice.

And there may at last be a critical mass of like-minded individuals and institutions ready to take the plunge. I am referring to the “Brevard Project” – “Reimagining the Future of Orchestral Programming” — debuting this July at the wonderful Brevard Music Festival. The sponsoring organizations, in addition to Brevard itself, are ArtsJournal, Bard College’s training orchestra The Orchestra Now, the Blair School of Music (Vanderbilt University), the Chicago Sinfonietta, the South Dakota Symphony, and the University of Michigan School of Music. When you factor in what’s already happening at these places, it’s an auspicious list.

The Project faculty is also exceptional. Some of the names, in addition to myself, are Leon Botstein, Lorenzo Candelaria, Mark Clague, Lara Downes, JoAnn Falletta, Delta David Gier, Blake-Anthony Johnson, Doug McLennan, Jesse Rosen, George Shirley, and Larry Tamburri.

The dates are July 11 to 16. Conductors, artistic administrators, executive directors, community engagement specialists, conservatory students, and board members are all welcome to apply. The fee, including tuition, housing, and meals, is $600. For information, click here.

Concurrently, Brevard is hosting a “Dvorak’s Prophecy” festival. The dates are July 8 to 15. There will be four concerts and numerous ancillary events. The repertoire includes William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony, the world premiere of Dawson’s “Largo” for violin and piano, a rare opportunity to hear Arthur Farwell’s magnificent Hako Quartet, novelties by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and Margaret Bonds, etc., etc. The performers include the legendary George Shirley.

Brevard itself is an idyllic retreat in the Blue Ridge Mountains, not far from Asheville. Temperate weather. No bugs.

April 2, 2022

Marian Anderson, Soundbites, and “Dvorak’s Prophecy”

The Conclusion to my book-in-progress When the Arts Mattered: An Exhortation begins:

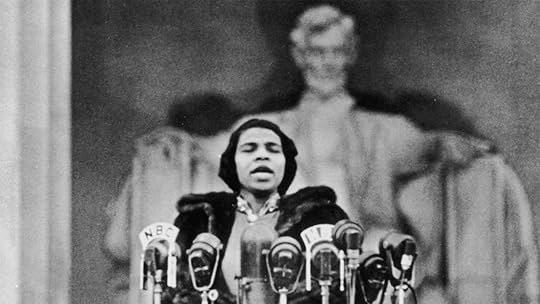

“No viewer could possibly glean the hypnotic impact of Marian Anderson from watching the 2022 public television documentary ‘The Whole World in Her Hands.’ Over the course of one hour and 53 minutes, she is rarely permitted to perform or speak for as long as a minute without some form of distraction – a photograph, a film, a voice-over advisory. When the moment comes for ‘My Country ‘Tis of Thee’ on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial – a mesmerizing newsreel clip – she sings for 17 seconds before a re-enacted commentary takes precedence (‘I as an individual was not important on that day – it happened to be the people I represented’), accompanied by an inter-racial gallery of American faces; the singing continues as a backdrop.

“A previous Marian Anderson documentary, produced by Kultur Films, is a little more lenient. But one has to go back 1957 – to Edward R. Murrow and ‘See It Now’ – to encounter a fundamentally different approach. Documenting Anderson’s recent tour of Asia, this 25-minute commercial TV show is sufficiently patient that one can engage in the moment. Her performance of ‘He’s Got the Whole World in his Hands’ unfolds gloriously, in four contrasting verses. And we feel privileged to see her sing a four-minute operatic aria with the fledgling Bombay City Symphony. No one feels impelled to inform us that Marian Anderson is a great artist.

“It would take a cognitive psychologist to adequately explore the pertinent costs of the soundbite mentality, now so ubiquitous that we do not even notice that our engagement with screens is necessarily superficial.”

Thanks to Naxos – a singular enterprise whose fearless sense of adventure is personified by its founder and ageless mastermind Klaus Heymann — my six “Dvorak’s Prophecy” documentary films are readily available via DVD or via the Naxos Video Library. They link to my book Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music. And – radically and tenaciously – they reject the soundbite template.

A new mega-review of the book and the films, by Mark Grant in The American Scholar, says it all:

“Can anything be done to effect a rapprochement between the old and the new paradigms so that the heritage of classical music can be revivified for younger generations? One possible answer is being suggested by the scholar and critic Joseph Horowitz in his new book Dvořák’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music. Horowitz seems to say that it’s not necessary to topple canonical classical music idols as if they were the Buddhas of Bamiyan, because a rich parallel heritage of African-American classical music has been hiding in plain sight all along. He has assumed the role of a skilled art conservator who is cleaning up an old master, removing an overlayer to disclose a pentimento: an underlayer that is a veritable classical music 1619 project. And at the same time, in a series of six companion videos that he narrates (Dvořák’s Prophecy: A New Narrative for American Classical Music, produced by Naxos), Horowitz goes a good way toward remediating the problematic aspects of media literacy, sound-bite epistemology, Snapchat concentration spans, and ahistorical narcissism that bedevil our culture today.

“Horowitz also argues that the primary champion and practitioner of Native American–based art music, the white Anglo-American composer Arthur Farwell, has not only been unfairly neglected, but is also still vexed by the charge of cultural appropriation. These and other questions are teased out both in his book and in the accompanying six videos, which focus on Dvořák, Ives, Black composers, Bernard Herrmann, Lou Harrison, and Copland, respectively. As a group, these videos (along with a CD of Farwell’s music) sweep together a vast canvas of . . . Americana . . . All are interestingly told. The video documentaries eschew the Ken Burns style of rapid montage and instead go into deep focus. Talking heads speak at length rather than in sound bites. The music on the soundtracks, performed by the Washington, D.C.–based PostClassical Ensemble (of which Horowitz is executive director) and conducted by Angel Gil-Ordóñez, is not interrupted by hyperkinetic visual montages or multiple voiceovers. It’s the documentary equivalent of “slow food”; there is room to absorb and think and remember. . . .

“The videos are fascinating and should be widely purchased and used by educators and institutions throughout the country to proselytize the unconverted. If classical music is going to survive and thrive, we need zealous advocates like Joseph Horowitz to continue beating the drum.”

To sample (and purchase) the six “Dvorak’s Prophecy” films – and strike a blow against soundbite reductionism — click here.

March 14, 2022

Revueltas and Social Justice on NPR

At the top of today’s 50-minute National Public Radio feature on Silvestre Revueltas – the fourth radio documentary I’ve produced for the WAMU newsmagazine “1A” – I observe:

“Art promoting social justice is everywhere upon us. It’s what our composers and visual artists and playwrights want to produce, it’s what presenters want to present, it’s what our foundations want to fund. We all feel that we’re responding to a state of emergency, especially with regard to issues of race and social justice – and that includes composer of classical music.”

You can hear it here.

Mexico, in the 1920s and ‘30s, was a place where political art flourished. The political murals of Diego Rivera, the political music of Silvestre Revueltas rose above ideology and propaganda to inspirationally define a nation. How and why that happened – and what we can learn from it today – is the topic I pursue.

I’m joined by the social critic John McWhorter, author of the best-selling Woke Racism, who warns that woke activism can diminish the arts (go to 34:50).

My other guests are the Mexican composer Ana Lara, the Revueltas scholars Roberto Kolb and Lorenzo Candelaria, the historian John Tutino, and PostClassical Ensemble conductor Angel Gil-Ordonez. I also sample President John F. Kennedy’s arts advocacy and ponder its pertinence (go to 31:50).

For a fascinating comment on the caliber of Mexico’s political leadership in the thirties – President Lazaro Cardenes possessed a singular cultural/educational vision – go to 23:30.

My final thoughts, at the end of the show: “I’m reminded that William Faulkner had something pretty harsh to say in 1958. Faulkner wrote: ‘The artist has no more actual place in the American culture of today that than he has in the American economy of today, no place at all in the warp and woof, the thews and sinews, the mosiac of the American dream.’ President Kennedy was responding to the estrangement of American artists like Faulkner . . . Do the American arts, can the arts inspire social justice – can they help refresh American identity? Will there by an American Diego Rivera? Can we hope for an American Silvestre Revueltas?”

The show highlights a new PostClassical Ensemble Naxos CD – the world premiere recording of Revueltas’s complete soundtrack to the iconic film of the Mexican Revolution: Redes (1936), unforgettably shot by Paul Strand.

Revueltas – “Mexico’s most famous unknown composer” – figures prominently in my “new paradigm” for American classical music, explored in my new book Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music.

To see a PostClassical Ensemble documentary film about Revueltas and Redes, click here.

To purchase the new CD with the complete soundtrack, click here.

To purchase a Naxos DVD with the complete film, click here.

I am again indebted to 1A producer Rupert Allman and 1A host Jenn White for this generous allocation of time for an important and ambitious topic, and to my colleague Peter Bogdanoff for his invaluable technical assistance.

February 24, 2022

The Russian Stravinsky

What happened to Stravinsky in the West? What to make of his “neo-classicism”? These are questions I’ve many times pondered in this space.

The superb Soviet-trained musicians who belatedly discovered Stravinsky’s post-Russian odyssey have certainly heard his music with different ears. The most extreme case I know is that of my great friend Alexander Toradze, for whom Stravinsky is at all times “Russian.” You can glean the same re-understanding from the Stravinsky performances of his longtime collaborator Valery Gergiev.

The latest evidence is the latest “PostClassical” webcast: an astounding performance of Stravinsky’s Concerto for Piano and Winds with Toradze and PostClassical Ensemble conducted by Angel Gil-Ordóñez. Toradze’s extensive commentary takes issue with the composer’s own instructions.

The many stories at hand include Lexo’s onstage meeting with Ella Fitzgerald in Portland, Oregon, in 1978, as a touring Soviet artist, and his stunning recollections of Stravinsky’s 1962 encounter with the legendary Soviet pianist Maria Yudina. He also shares his religious reading of the Piano Concerto’s slow movement as a “duality” of Roman Catholic and Russian Orthodox influences.

Angel and I join Lexo alongside our usual host, the inimitable Bill McGlaughlin. Listen here.

For more Toradze — a fabulous film — click here.

LISTENING GUIDE:

5:00 – Stravinsky speaks: “music can express nothing” and cannot be “interpreted” – his neo-classical credo, formulated in Paris after World War I.

6:00 – A 1928 recording by Stravinsky and his son Soulima of Mozart’s C minor Fugue embodies the radically impersonal aesthetic Stravinsky now embraced; I call it “insolently impersonal.”

8:30 – Toradze remembers Stravinsky’s own performance of The Firebird in Moscow (1962) as “very uninteresting.” In his edition of Stravinsky’s Piano Sonata (published after the composer’s death), Soulima contradicted his father and embraced expressive “interpretation.” Toradze understands Stravinsky’s strictures against interpretation as a strategy for counteracting traditional piano styles rooted in Romantic repertoire (Liszt, Chopin, etc.). He recalls that, in Russia in 1962, Stravinsky testified that he always “dreamt in Russian.”

23:00 – We sample Stravinsky’s own 1968 recording of the Piano Concerto (with Philippe Entremont). Toradze finds the opening Largo too fast; he endorses the original tempo marking: “Largissimo.” He argues that composers are sometimes self-consciously constrained performing their own music, and cites Rachmaninoff as an example.

32:00 – Movement 1 of the Stravinsky Concerto, with Toradze and Angel Gil-Ordóñez is conducting PostClassical Ensemble (2011)

40:00 – The influence of jazz on Stravinsky and Toradze. During Toradze’s student years in Moscow, American jazz was “food for the soul”; it created the illusion “that’s what [American] freedom is about.”

54:00 – In 1978, on tour in Portland, Oregon, Toradze met Ella Fitzgerald and told her (onstage) that she was “a goddess” in the Soviet Union.

57:00 – In Toradze’s religious reading of the second movement of the Stravinsky Concerto, a “duality” of Roman Catholic and Russian Orthodox musical influences interact. Stravinsky, in France, believed his bleeding finger was cured by a religious miracle.

1:05 – Movement 2 of the Stravinsky Concerto, with Toradze and Gil-Ordóñez

1:20 – Movement 3 of the Stravinsky Concerto, with Toradze and Gil-Ordóñez

1:25 – Toradze remembers the Russian pianist Maria Yudina, “a colossal figure” who long championed Stravinsky in the USSR. She first heard the Stravinsky Concerto performed by Seymour Lipkin, Leonard Bernstein, and the NY Philharmonic on tour in Moscow in 1959. She met Stravinsky in Moscow in 1962 and was dismayed to discover him susceptible to “photo opportunities and journalists.”

We close by sampling Yudina’s 1962 recording of the Stravinsky Concerto, conducted by Genadi Rozhdestvensky.

January 12, 2022

The Arts and Social Justice — Bedfellows?

Diego Rivera, Triumph of the Revolution (1926)

Diego Rivera, Triumph of the Revolution (1926)Today’s online edition of The American Purpose – an indispensable centrist voice pondering the contemporary condition of government, politics, and the arts – includes a piece of mine inviting dialogue on a topic people don’t dare talk about – the insistence that arts institutions necessarily serve as instruments for social justice.

You can read the whole article here. What follow are excerpts:

I am thinking especially of the charitable foundations that have decided to stop funding the arts, or to only fund arts activities that explicitly promote diversity, equality, and justice. This is the reductionist notion that has steered philanthropic giving away from traditional “high culture.” . . .

But insisting that plays, paintings, and symphonies expressly serve social justice quite obviously risks marginalizing the arts by erasing part of what they stand for. . . .

I have long been the recipient of communications from silenced voices – creative and performing artists who fear reprisal if they speak out loud:

“The foundations are pitting the arts community against itself.”

“Foundations today are behaving as blunt instruments . . . To me, the most profound fallacy is the notion that there’s not enough money to do both – to serve social justice concerns and to maintain contact with our past cultural pillars.”

“I believe the foundations are engaged in a form of blackmail. The way to get other people to even consider your point of view is not by legislating morality. It disrespects the power of religion, or of art — if you believe that art has the power to bring people together. In the case of evangelicals and today’s charitable foundations – they’re trying to alter the essential DNA of religion and of culture in order to prove ‘relevance.’”

“We are in a period of calling out and shaming – and the foundations are following the activists. Of course, you have to start somewhere, and certainly this is a starting point that will see results. People understand that. But it’s my impression that we’ll move from the understandable to the upsetting pretty quickly. We all know we can’t go back to the way things were. That doesn’t mean we should burn everything down. We must move forward in a more enlightened way, with greater understanding of how our structures caused harm.” . . .

One version of the rejection of “high culture” goes like this: “The arts are thriving today in communities all across the United States. It all depends on where you look.” . . . This conviction observes a surging political art, passionately fixed on issues of diversity and inclusivity. But is this sufficient for art to “thrive”? . . .

Instead of the loaded high/low distinction, consider juxtaposing art that endures with art that proves transitory. To be sure, transitory art has its place. But cultural memory, when it sticks, is an indispensable source of ballast, whether personal, communal, or national. A crucial ingredient, increasingly elusive, is a usable past: roots in common. In fact, we can only escape the past – its sins and omissions – by embracing it. And this, traditionally, is a vital task for the creative artist in every field. It is part of what makes political art matter. . . .

Does art serve social justice? Does social justice serve art? My own impression is that much of what today passes for politically aroused art fails to transcend journalistic agitation. It does not linger in the mind and heart. It does not furnish the ballast associated with great literature and music, paintings and sculpture. That equation is traditional. It may also be indispensable.

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers