Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 2

July 20, 2025

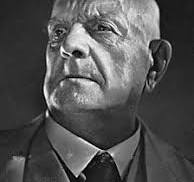

Alfred Brendel (1931-2025)

In the wake of the death of the pianist Alfred Brendel on June 16, I notice a sharp uptick in viewers of my 2016 “Wall Street Journal” review of Brendel’s collected writings, my main interest being Brendel and Franz Schubert. I reproduce an excerpt from my review below. You can read the whole thing here:

In the Schubert essays here collected, Mr. Brendel hones a metaphor that ceaselessly illuminates this protean composer: the “sleepwalker.” Using Beethoven’s decisiveness of form and sentiment as a foil, he showcases Schubert’s waywardness—a defining feature long misread as weakness. As opposed to Beethoven’s “inexorable forward drive,” Schubert can convey “a passive state, a series of episodes communicating mysteriously with one another.” As opposed to Beethoven the “architect,” Schubert “strides across harmonic abysses as though by compulsion, and we cannot help remembering that sleepwalkers never lose their step.” Next to Beethoven’s “concentration,” Schubert ”lets himself be transported, just a hair’s breadth from the abyss, not so much mastering life as being at its mercy.”

These observations will strike home to anyone who has listened closely to the Schubert sonatas or whose fingers have grappled with them and experienced at close quarters their chronic resistance to definitive formulation. Their ambiguities of sentiment and interpretation excite feelings of vulnerability. The A major Sonata, D. 959—for some, Schubert’s supreme achievement for the keyboard—begins at least three times. Only with the dreamy second subject, a Lied, does the first movement attain a recognizable expressive state. The second movement shatters into atonal chaos. An endless finale gradually establishes the first movement’s song mode as an anchoring poetic ingredient. Translating this music into words, Mr. Brendel finds “desolate grace behind which madness hides.”

One corollary, as with Mahler, is a musical state of existential duress unknown to Beethoven, a condition of unease or terror prescient of world horrors to come. Mr. Brendel: “In such moments the music exposes neither passions nor thunderstorms, neither the heat of combat nor the vehemence of heroic exertion, but assaults of fever and delusion.” Schubert presents “an energy that is nervous and unsettled . . . ; his pathos is steeped in fear.” An “impression of manic energy” points to “the depressive core of [Schubert’s] personality.”

Mahler himself wrote of Schubert’s “freedom below the surface of convention.” Mr. Brendel: “The music of these two composers does not set self-sufficient order against chaos. Events do not unfold with graceful or grim logic; they could have taken another turn at many points. We feel not masters but victims of the situation. . . .”

For a related blog on “Schubert and the Music of Exhaustion,” click here .

July 6, 2025

Will Europeans Curate Our Receding Cultural Past?

My 2022 book Dvorak’s Prophecy has just been published in German (by Wolke Verlag) with a new Foreword for German-language readers: “The European/American Transaction.” I take note that the recent Charles Ives Sesquicentenary “was mainly celebrated in Europe”; that it is in Europe “that every city boasts a jazz scene engaging Americans who cannot find American gigs beyond a few major cities;” and that my novel about Gustav Mahler “sells far more briskly in Germany than in the United States.”

A few weeks ago I was apprised of Ingo Metzmacher’s remarkable Ives tribute in Hanover last June 8 featuring Thomas Hampson, the NDR Radio Philharmonic, a university orchestra, and nine choirs, plus running commentary by Metzmacher. Would that a major American orchestra would even consider something of this kind.

Here’s how my new Foreword ends:

“Among the reviews greeting Dvorak’s Prophecy, my new paradigm was most personally embraced not by a musician or music critic, but by a prominent African-American arbiter of American mores: John McWhorter in the New York Times. ‘Horowitz has taught me a new way of processing the timeline of American classical music,’ McWhorter wrote. Addressing Porgy and Bess, he added: ‘Horowitz teaches us to stop hearing [it] narrowly, as a Black opera, or as some sideline oddity called a folk opera. It is what opera should be in this country, with our history, period. Under this analysis, the scores to Copland’s Billy the Kid and Rodeo, for all their beauty, are the fascinating but sideline development, not Porgy and Bess.’ More informative, in its way, was an unsigned review in Publishers Weekly by a writer so impatient with my book that he obviously skimmed parts of it, misidentifying Arthur Farwell as a Black composer and summarizing: ‘Horowitz’s preoccupation with long-forgotten, avant-garde critical controversies make this interpretation of America’s protean musical development feel dated.’

“Precisely. The quest for a usable literary past once undertaken by Van Wyck Brooks, Lewis Mumford, and F. O. Matthiessen, the useless musical past once proclaimed by Copland and Thomson, were mainstream intellectual events, not ‘avant-garde.’ If in fact they are ‘long-forgotten’ and ‘dated,’ so much the worse for us. Equally informative, I would say, is that a publication kindred to Dvorak’s Prophecy, in the form of a provocative piece of historical fiction, was concurrently undertaken not by an American writer, but by Christian Much, who was born in Luxemburg and writes in German. . . .

“A related perspective: the recent Charles Ives Sesquicentenary (he was born in 1874) was mainly celebrated in Europe. And so is jazz (so vital to American identity): it is in Europe that every city boasts a jazz scene engaging Americans who cannot find American gigs beyond a few major cities. I am reminded that when the American West was initially documented, among the first prominent professional artists to portray Native America happened to be Swiss: Karl Bodmer. The most celebrated painter of Rocky Mountain landscapes was German-born: Albert Bierstadt. The German-Russian painter Louis Choris was an important early chronicler of the Pacific coast. The most important chronicler of musical New York, in its fin-de-siecle heyday, was Henry Krehbiel, a bilingual product of German immigrant parents. . . .

“Will Europeans, in decades to come, prove necessary custodians of the American cultural past? I can only hope so.“

July 3, 2025

Combating American Isolationism with Cultural Diplomacy

My unforgettable experience touring South Africa with the University of Michigan Symphony Orchestra and their conductor Kenneth Kiesler is the topic of my most recent NPR feature and also of three previous blogs in this space. (Above: Karen Slack singing “My Man’s Gone Now” in Cape Town, photographed by Patrick Morgan.) Today, “The American Scholar” publishes my further reflections online . I write in part:

“Cultural exchange was once a high-profile foreign policy priority for occupants of the White House. A pivotal instance was the 1959 visit to Soviet Russia of Leonard Bernstein and his New York Philharmonic. Bernstein brought Ives and Copland to the USSR, but also performed Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony. His interpretation—with a sped-up ending—was embraced by Shostakovich himself. This startling exercise in mutual understanding was not so different from the University of Michigan musicians setting down their instruments and singing the beloved Xhosa hymn “Bawo, Thixo Somandla.” But MAGA signifies a new isolationism—a go-it-alone toughness. The cancelation of the Voice of America, of Fulbright scholarships, of USAID are all part of this picture. And so is the new hostility to hosting Chinese students.

“My own experience of Chinese students is meager but unforgettable. One was hearing and meeting a 20-year-old Chinese pianist: Yifan Wu. His favorite composers are Robert Schumann and Paul Hindemith—a singular pairing. For his all-Schumann recital in New York City, he brought (from China) his own piano bench (he sits low). He improvised between pieces. His interpretation of Schumann’s Kreisleriana was the most compelling I have ever heard. In conversation, he is voluble and cosmopolitan. The kicker is that to date Yifan Wu is wholly trained in China, by Chinese teachers. Then there was the pair of Chinese students my wife and I encountered at a neighborhood restaurant. We were astonished by their poise and maturity—and the alacrity with which they spoke critically (and not) about conditions in China.

“China, right now, is exercising immense influence in South Africa. To keep young Chinese out of the United States, or to discourage study in China, makes so little sense that retaining soft diplomacy, sans governmental support, becomes a patriotic initiative. It also sustains the arts in a world at risk. And—a related goal—it sustains basic American ideals of individual freedom. . . .”

Juxtaposing “the gaudy AI imagery of dueling elephants and murderous crocodiles that I encounter on my YouTube feed” with the same animals we glimpsed coexisting in real life in the Pilanesburg National Park, I conclude:

“Doubtless the University of Michigan tour was conceived as a showcase for its exceptional orchestra, abroad and at Carnegie Hall. Its higher purpose, deserving even greater applause, was to combat metastasizing American isolationism—and, commensurately, the growing insularity of young Americans entrapped by circumstances and technologies now being inflicted upon them. “Doubtless the University of Michigan tour was conceived as a showcase for its exceptional orchestra, abroad and at Carnegie Hall. Its higher purpose, deserving even greater applause, was to combat metastasizing American isolationism—and, commensurately, the growing insularity of young Americans entrapped by circumstances and technologies now being inflicted upon them.”

Our sunset safari at the Pilanesburg National Park, as captured by Patrick Morgan

Our sunset safari at the Pilanesburg National Park, as captured by Patrick Morgan

June 25, 2025

“A Service to the Nation” — The University of Michigan Symphony Orchestra Tours South Africa

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa in the Oval Office with United States President Donald Trump

My most recent More than Music documentary on NPR ponders the South African tour of the remarkable University of Michigan Symphony Orchestra, led by Kenneth Kiesler. The tour happened to coincide with inflamed relations between South Africa and President Donald Trump. I conclude: “During the long Cold War decades, the US sent musicians abroad to countries where we were competing for influence with other major powers — where we were insufficiently known or not sympathetically understood. South Africa is such a country today – right now. The University of Michigan tour showered credit on the university and its young musicians. It also, I would suggest, performed a service to the nation.”

A recurrent theme, in the show, is the rule of law – and an impression, in South Africa, that at present it’s more reliable there (where ex-President Jacob Zuma was tried, convicted, and imprisoned) than in the United States. Another is that the Trump Presidency, for some South Africans, triggers memories of the apartheid decades.

Andries Coetzee, who accompanied the tour, is a University of Michigan Linguistics professor who was born and raised in South Africa. He testifies to the urgency of exposing American college students to other cultures, and the commensurate importance of welcoming foreign students at American universities. And he told me a startling story about a meeting at the University of Western Cape, which has long partnered the University of Michigan. Once a Black university under apartheid, University of Western Cape is now “a powerhouse in South African education, representing the country as a whole,” Coetzee said. “What was very moving to me . . . was when members of the leadership team turned to us, representing the University of Michigan, and said: . . . ‘Now you are in a situation in the US where higher education is under severe duress and oppression. . . . We have a lot of experience over decades on how to exist under such conditions. How can we now help you?’’”

Another participant in the NPR show is Christopher Ballantine, South Africa’s pre-eminent music historian and, at 82, a veteran of the anti-apartheid struggle. Like Coetzee, he acknowledges the formidable challenges South Africa faces today, including rampant Black unemployment. Like Coetzee, he’s optimistic about the country’s future. Chris regularly reports on South African opera for the British journal Opera. He told me that my recent experience of Aida in Cape Town – the subject of a previous blog — was a truthful experience.

“What’s made South African opera so rich in Black vocal talent is the long tradition of choral singing in South Africa. Thousands of choirs. . . . When this Black singing talent is brought into the opera house, before audiences that are unfortunately still largely white — although that’s slowly changing — then you do get this bridging. The rapturous applause is not just rapturous applause at superlative singing, it’s also rapturous applause because people are coming together in a way that never used to be possible. You see that all the time. Not only at concerts. . . . If you go to important sports matches in South Africa – the rugby world cup, for example, which South Africa has now won on the last two occasions — there’s an enormous sense of national pride and national unity around that.”

I asked Chris Ballantine if classical music in South Africa is stigmatized as “colonial.” He replied:

“There is of course a keen awareness of the colonial legacy here. But it’s not used in any kind of punitive way. And that’s unlikely ever to occur. If you think of the fact that South Africa is one of the most multi-cultural countries in the world. The constitution guarantees cultural diversity. It guarantees the right of all 12 official languages to exist side by side. What that means is that this recent nonsense about white genocide in South Africa is just that. It’s total fabrication.”

I also chat with South Africa’s leading classical music impresario, Bongani Tembe, who runs the orchestras in Durban and Johannesburg, and in 2022 founded a national South Africa orchestra with government support.

In two previous blogs, I deployed video clips to document the transformative impact of the young Michigan musicians in Soweto, Pretoria, Johannesburg, and Cape Town. On the NPR show, you can sample their performance of one of the peak achievements in Black classical music: William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony (1932). It’s a piece I’ve written about a lot. Kiesler’s reading, in South Africa, was the strongest I’ve ever heard, superior to all the commercial recordings. As I remark on NPR: “These highly skilled pre-professional musicians comprise one of the least jaded, most engaged symphonic ensembles I’ve ever come across” – a topic that connects to my recent report, in the New York Review of Books, on Aida at the Metropolitan Opera (and its jaded musicians).

In my NPR show, I award the last word to the orchestra’s remarkable conductor. Ken Kiesler had no idea, when he chose South Africa for his orchestra’s first tour abroad, that the visit would coincide with the expulsion of South Africa’s ambassador to the US. It made the tour all the more meaningful, Kiesler said.

“Isn’t cultural diplomacy the sort of natural result of simply being authentic and sharing ourselves with others and receiving how they are with respect, even with admiration and love? When we remove what happens between governments, and government leaders, it’s just people listening to each other. Its such a beautiful experience that connects us . . And I think we should do more of it, all of us.”

Kiesler added that he initially considered taking his orchestra to the major halls of Europe. “It didn’t inspire me, and I knew it was the wrong thing.” South Africa “felt like the right place and the right time.”

P.S. – As my NPR colleague Jenn White observes, More than Music is no longer supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities – allocated funds were cancelled. WAMU, our host station, is currently seeking alternative sources of sponsorship.

To hear a pertinent More than Music show on cultural diplomacy click here .

My pertinent book, on the cultural Cold War, is “The Propaganda of Freedom.”

LISTENING GUIDE (to hear the show, click here):

3:00 — Kenneth Kiesler on the Soweto experience

7:25 — Andries Coetzee on the Soweto experience

12:00 — The University of Michigan Symphony Orchestra surges through the first movement coda of the Dawson symphony

14:30 — Kiesler on the Dawson symphony and South Africa

15:45 — The UMSO plays “Hope in the Night” — movement two of the Dawson symphony

21:00 — Bongani Tembe on classical music in South Africa today

26:30 — Christopher Ballantine on South African pride

28:30 — The UMSO nails the ending of the Dawson symphony

31:00 — A dozen at the District Six museum describes a disappointing visit of Columbia University students

32:00 — Coetzee on the urgency of global engagement

39:00 — Coetzee on the University of Western Cape’s offer to help the University of Michigan

42:00 — Final observations from Kenneth Kiesler

May 31, 2025

“Aida” in South Africa: a Sonic Earthquake

Photo: Oscar O’Ryan

Never in an opera house have I thrilled to such a sonic earthquake as the wall of sound produced by the Cape Town Opera in its current production of Verdi’s Aida. In the triumphal scene, the stage is packed with robust Black voices, all functioning at full throttle. A decibel more would be painful to the ears.

A crucial ingredient – the reason nothing comparable is possible at the Metropolitan Opera – is the scale of the house: 1,487 seats, versus the Met’s 3,800. And the acoustics (as experienced from row G in the orchestra) are terrific.

Cape Town has a long history of opera, including many distinguished Italian visitors. Today, the singers are South Africans. The company remains a vital component of the city’s cultural life. Aida is being given five times and the entire run seems sold out. The audience (overwhelmingly white) is expectant, appreciative, warmly enthusiastic. The company (overwhelmingly Black) is a company, an ensemble, populated by “house soloists.”

Nobulumko Mngxekeza, singing Aida, was introduced to music when she joined her high school chorus. She later studied voice at the University of Cape Town College of Music – a trajectory that has in recent decades produced countless South African operatic artists now featured in Europe and the United States. She commands a rich-hued soprano of good size. Her previous roles, all lighter, include Bess, Pamina, and Micaela.

The company’s pit orchestra is the Cape Town Philharmonic, a practiced full-time professional ensemble. The Aida conductor is the company’s music director, Kamal Khan. Though I found his reading unexceptional, the house’s vivid pit acoustic insures high impact, especially from the low brass.

The Aida director, Magdalene Minnaar, is a South African soprano who also serves as the company’s artistic director. She has conceived an “Afro-Futurist” production, strangely set and costumed. To my eyes, it contributed little but rarely got in the way – excepting four robotic supernumeraries whose rapid mechanical gait at all times violated the music. The contributions of the choreographer, Gregory Vuyani Maqoma, were both more telling and more original.

What I most appreciated was the buoyancy and informality of the occasion. (I am told it is difficult even to purchase a suit and tie in cosmopolitan Cape Town.) Of opera as an elite pastime there is not even a whiff. The season to date has notably included a festival of short operas (with piano accompaniment), including new works plus Schoenberg’s Erwartung and Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle. The Barber of Seville and The Magic Flute are coming up.

May 27, 2025

“A Tale of Two Cities” — Music and Race in Boston and New York

My latest installment of “More than Music” on NPR explores racial attitudes in Boston and New York at the turn of the twentieth century. During Antonin Dvorak’s historic American sojourn (1892-95), he was classified by Boston’s music critics as a “Slav” – a rung below Anglo-Saxons like Beethoven. The leading Boston critic, Philip Hale, also called Dvorak a “negrophile” and decried his influence on Boston’s leading composer, George Chadwick. Hale considered African-Americans “barbarians.”

As this line of thought – hierarchizing race – was once ubiquitous, we may be shocked but unsurprised. It is the New York response to Dvorak that is truly surprising. When New York’s critics assessed Dvorak, racial hierarchies were never invoked. In fact, no less than Dvorak when he espoused “Negro melodies,” many New Yorkers looked to Black America for musical instruction and guidance.

It was at Manhattan’s Madison Square Garden Concert Hall that Dvorak led an inter-racial orchestra, an all-Black chorus, and two stellar Black soloists in his arrangement of Stephen Foster’s “Old Folks at Home” in 1894. Three years later, William Randolph Hearst rented the Metropolitan Opera House for a fundraiser featuring the Black vaudeville stars Bert Williams and George Walker alongside excerpts from Aida and Rigoletto. Those events were unthinkable in Boston.

In short: New York was a city of immigrants. In Boston, you were an American if your forebears descended from the Mayflower. My own writings – in particular, comparing Boston and New York in Classical Music in America: A History of Its Rise and Fall (2005) – have long explored the surprising fluidity of race in late Gilded Age New York.

A comparable perspective, also sampled on “A Tale of Two Cities,” is detailed in Dale Cockrell’s remarkable 2019 book, Everybody’s Doin’ It — Sex, Music and Dance in New York: 1840 to 1917. Cockrell’s methodology was to scour the reports of undercover agents working for a well-heeled vigilante group: The Committee of Fourteen. They infiltrated saloons, hotels, dance halls, and brothels. The “disorderly behavior” they successfully terminated was specifically inter-racial: music, dancing, and sex. Segregation set in just after World War I. Harlem’s famous Cotton Club, where Black musicians entertained white audiences, was one result.

“I don’t know where this myth got established,” Cockrell says of Gilded Age stereotypes emphasizing snobbery and privilege. Applied to musical New York, “it’s just wrong.”

As I remark on NPR: “The iconic image is Edith Wharton’s account of going to the opera, in her 1920 novel The Age ofInnocence – a world of snobbery, wealth and fashion. But look again and Wharton is only describing one stratum of the audience at the Academy of Music: the boxholders. We know from other accounts that the Academy’s opera audience was roiling with boisterous Germans and Italians. During intermissions, they would congregate with the singers, amid clouds of cigar smoke and liquor fumes, in a basement lager beer cavern.”

To read my “Wall Street Journal” review of Dale Cockrell’s book, click here.

To read a review of “More than Music” in the Boston Musical Intelligencer, click here.

LISTENING GUIDE (to hear the show, click here):

PART ONE: Dvorak sets “Old Folks at Home” in New York; Music critics hierarchize race in Boston

PART TWO (12:00) : Celebrating Boston’s George Chadwick — “the most maligned and misunderstood American composer”

PART THREE (29:50) : Boston debates Arthur Nikisch’s Beethoven 5; Dale Cockrell expounds racial fluidity in NYC before WW I

May 24, 2025

Cultural Diplomacy in South Africa Continued: the University of Michigan Concert Orchestra Goes to Soweto

The Soweto audience erupts. Video by Mathew Pimental

Among my most telling experiences of South Africa, when I first visited in 2023, was encountering a group of uniformed schoolchildren passing through security at the Johannesburg airport. They were all singing, beautifully and happily.

It is a singing country. Jeremy Silver, Director of Opera at the University of Cape Town – a program that quite famously produces Black opera singers in profusion – moved to South Africa from Great Britain. In the NPR show I produced on South African opera – “You Get What You Deserve” (2024) — Silver says of his students that theirs is “a completely different world [from the US]. . . . It’s interesting: you might have thought that the experience of being segregated could have provoked exactly the same sort of emotions as with the enslaved population of the States. But in fact there’s an incredible energy and jubilation amongst the African community here. No matter how much people are suffering. There’s still a huge amount of poverty. But there’s always a smile, there’s always a hope.”

A similar observation, on the same NPR program, came from John McWhorter, a prominent African-American voice on race and culture: “To a Black American, some Africans can seem almost oddly secure and joyous – they don’t seem to have a basic sense of whiteness as an insult to them.”

Music in South Africa wears many faces. Seemingly always, however, it exudes resilience in the presence of adversity. It is both infectious and humbling.

***

Soweto was the second stop in the current South Africa tour by Kenneth Kiesler and his terrific University of Michigan Concert Orchestra. The venue was the Regina Mundi Catholic Church, a historic landmark in the victorious struggle against apartheid. Bullet holes once inflicted by police guns have purposely not been patched.

In a previous blog I described the orchestra’s first concert, at the University of Pretoria. Upon hearing the musicians sing the beloved Xhosa song “Bawo, Thixo Somandla,” the inter-racial audience burst into rhythmic clapping and piercing ululation. In Soweto, where the audience was Black, the listeners burst into jubilant song. The church rang with “Bawo, Thixo Somandla,” and with the traditional hymn “Plea for Africa,” and again during Miriam Makeba’s iconic “Pata Pata.” The music grew tidal. The audience departed the church singing. Many in the orchestra wept.

***

The generous program Kiesler has chosen for the tour – which ends at Carnegie Hall on May 30 (New Yorkers take note) – is both ingenious and empathetic. The main work – about which I long screamed in the wilderness – is William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony (1932), a profound narrative of servitude and liberation in which the excavation of African roots plays a key role.

Kiesler paired the Dawson with excerpts from George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. That is: he coupled the two most fulfilled interwar realizations of Antonin Dvorak’s 1893 prophecy that “Negro melodies” would foster a “great and noble school” of American classical music. In combination, they encapsulate a road not taken. Had Dawson enjoyed success and produced a series of African-American symphonies, had Gershwin not died at the age of 38, classical music in the US could have pursued a more distinctive, more protean path.

Kiesler also programed Harry Burleigh’s “Deep River,” as orchestrated by Carl Davis. Once Dvorak’s New York assistant, Burleigh was the first composer of high consequence to follow in Dvorak’s wake: it is he who influentially turned spirituals into art songs, with “Deep River’ (1913) coming first. The degree to which the “Deep River” we know is in fact a Burleigh composition is a fascinating topic. Equally fascinating is the version he composed for a cappella male chorus: it begins by citing the chordal introduction to the Largo from Dvorak’s New World Symphony. The iconic concert spiritual of the 1920 and ‘30s – its deliberate tempo and reverent tone (the earliest extant “Deep River,” from the 1870s, is upbeat) — was partly inspired by a visiting Bohemian genius with roots in the soil.

Dvorak’s symphony was also a lodestar for Dawson: that the Negro Folk Symphony, like Dvorak’s “New World,” is a Romantic national symphony is one reason for its neglect during long modernist decades that favored a leaner, cleaner “American“ sound. To my own ears, the symphonies by Aaron Copland and Roy Harris today seem less formidable than symphonies of Dawson and Charles Ives that more intimately hug the American vernacular.

***

I listened to the Soweto concert alongside Andries Coetze, a University of Michigan linguistics professor who was born and raised in South Africa. When it was over – when the singing audience slowly and ceremoniously filed out of the church, with songs of liberation still ringing in the nave — Andries’s eyes moistened and he said:

“I’ve lived in the US now for 26 years and I come back to South Africa very often. But I have not felt as at home, as a South African, as I do at this moment – not for a very long time. When I became a United States citizen some fifteen years ago, I automatically lost my South African citizenship. It didn’t mean that I stopped identifying as South African — that is who I am. But I did feel as if I was robbed of a part of my identity. Two weeks ago, the South African Constitutional Court ruled that the law under which I lost citizenship is unconstitutional. So after nearly fifteen years of not being a South African citizen, I am all of a sudden one again. Or more accurately, according to the ruling, I have actually been a citizen all along. Tonight felt like a confirmation of my belonging – like a reaffirmation of my identity. It was a ‘welcome home’ from my fellow South Africans.”

And he hugged his nearest fellow South Africans, still swaying and singing, still reluctant to depart.

To listen to my NPR shows about opera in South Africa and about Harry Burleigh, click here.

To read about the Dawson symphony, click here.

My most pertinent book: Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music (2021).

May 21, 2025

American Cultural Diplomacy in South Africa Right Now, Courtesy of the University of Michigan

Video by Mathew Pimental

At the precise moment that US President Donald Trump was accusing South African President Cyril Ramaphosa of denying acts of racial persecution, the University of Michigan Orchestra began a five-concert tour of South Africa with a smashing two and half hour program at the University of Pretoria.

The main work on the program was a neglected American masterpiece influenced by Africa: William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony of 1932. The terrific performance, ignited by conductor Kenneth Kiesler, nailed the symphony’s rocketing syncopations — and drove the sold out audience to a ululating frenzy of acclaim.

But the concert’s peak impact occurred near the close, when the 100 musicians abandoned their instruments and stood to sing the beloved Xhosa song “Bawo Thixo Somandla.” Halfway through, they began to sway and gesture. They ambushed the sold-out audience into a condition of incredulous delight.

Six decades ago, cultural exchange between the US and USSR proved an indispensable foreign policy instrument, beginning with Leonard Bernstein’s 1959 tour to Soviet Russia with his New York Philharmonic. As the Cold War waned, however, so did soft diplomacy. Today, it is – at least for the moment – cancelled by a posturing toughness.

The University of Michigan orchestra next proceeds to Soweto and Cape Town — in counterpoint with exacerbated relations between the US and South Africa.

At a joint rehearsal earlier today with Michigan musicians playing alongside the University of Pretoria Orchestra, Kiesler told the group: “How moving it is to be all together, when our governments are not.”

To read a related article about the waning of soft diplomacy, click here .

May 8, 2025

What Ails Today’s Metropolitan Opera? — It’s in the Pit

The current issue of the “New York Review of Books” carries my review of the Metropolitan Opera’s current “Aida” – a new production given fourteen times this season. It features one of the company’s heralded young stars – the soprano Angel Blue – and it’s mainly conducted by the Met’s music director, Yannick Nezet-Seguin. The result is tepid. As “Aida” is the quintessential grand opera, its current fate, I write, “must disclose something about the fate of the house” and the challenges it faces. A crucial defect “is what’s happening – and not — in the pit.” I proceed to compare today’s “Aida” conductor and orchestra with the Met orchestra of the 1930s and the conductor then presiding over Italian opera: Ettore Panizza – a Verdi interpreter of genius. I write in part:

Of the Met’s earliest Aida broadcasts, the most esteemed (it is readily available on youtube) was aired on February 6, 1937. . . . What first commands attention is Panizza and his band. The intensity of this contribution is not merely different in degree from what we now hear; its difference is fundamental: a difference in kind. Compared to Nezet-Seguin, Panizza deploys a vast range of tempo (the final duet is more than a third slower than the one to which we have grown accustomed). Additionally, the pulse throughout is radically flexible, accommodating scorching accelerandos (typically at cadences and phrase endings) and lyric allargandos (expanding the arc of a sung phrase). At the same time, linear tension is maintained – so the cumulative effect is that of an ongoing flexed line. All of this furnishes punctuation and trajectory, shape and purpose. The pit is not supportive; it is collaborative. . . . [In act three,] Amonasro enters: a wild man: “You are not my daughter! You are the slave of the Pharaohs!” And Panizzza’s orchestra is wild. . . . Juxtaposed with this powder keg, today’s Met orchestra is a matchbox. . . .

The American arts are mired in a crisis of cultural memory. The implications for the Metropolitan Opera . . . are infinitely complex. A basic reality, finally, is that grand opera is a product of the nineteenth century, and its most idiomatic exponents began to fade from the scene half a century later. Absent a time machine, maintaining opera as a living artform can today only be an exercise in ingenious accommodation. Panizza was no anomaly – he embodied interpretive norms once widespread and now best remembered via the recordings of Toscanini (they were colleagues at La Scala). Are those performance practices – if adequately acknowledged and studied – to any extent revivable? Is it at least possible to revive the intensities of a Dmitri Mitropoulos or Georg Solti – non-idiomatic Verdi conductors who lit a fire at the Met? A further consideration: Toscanini, in his final Met season, led 68 out of 209 performances. Panizza, in his final Met season, led 38 of 69 performances given in Italian. This season, Nezet-Seguin (who is also music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra) leads only 36 of 194 performances. The house needs a genuine music director of its own.

For a related blog on Yannick Nezet-Seguin conducting Wagner at the Met, click here.

For a related article on Lawrence Tibbett and the “crisis” afflicting opera in America, click here.

April 18, 2025

Three Who Quit: Ives, Elgar, Sibelius and the Crisis of Modernism

The current “Musical Opinion” (UK) carries an essay of mine: “Three Who Quit: Ives, Elgar, Sibelius, and the Crisis of Modernism.” Strange bedfellows? Think again. Ultimately, my topic is the dead end afflicting twentieth century classical music. My final sentences read: “The dialectical tension between present and past, long the mainspring for musical creativity, has gone slack. In Ives, Elgar, and Sibelius, in Stravinsky and Schoenberg, this conundrum, differently manifest, ran its fatal course.” What follows is an extract – my closing sally – with key points in boldface. (The same issue — which you can download below — carries an excellent piece on Shostakovich):

Musical Opinion April – June 2025DownloadA glance at the leading musical modernists contemporaneous with Ives is instructive. Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg — not the residual Romantics Elgar, Sibelius, and Ives — are latter-day Fausts, craving experience new and original. Courageously, perilously, they undertook a radical transformation of their own stylistic signatures.

And they do not [like the anti-modernists Elgar, Sibelius, and Ives] invoke Nature. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov did – most profoundly in his late opera The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh, composed in 1907 when Stravinsky was his prize pupil, virtually a surrogate son. The twittering, shimmering forest music of Stravinsky’s The Firebird (1910) is a sequel to Rimsky’s. Gustav Mahler, a seminal inspiration for Schoenberg and his followers, was a supreme Nature poet. And so, initially, was Schoenberg, in the comparably twittering, shimmering Prelude to Gurre-Lieder (1910) – but never thereafter. As post-World War I modernists, Stravinsky and Schoenberg were dissident, deracinated. No less than the modernist painters and novelists, their predilection was to deconstruct and reformulate. Elgar, Sibelius, and Ives eavesdrop on Nature – a posture of humility, comity, and subordination. Concomitantly: for them, the past remained a daily background presence. Stravinsky and Schoenberg were emigres dislodged by world events; Stravinsky’s St. Petersburg, Schoenberg’s Vienna were no more.

But can the past ever be evaded? In 1928 Stravinsky composed a ballet, The Fairy’s Kiss, adapting more than a dozen Tchaikovsky songs and piano pieces. The plot reads as an allegory of Tchaikovsky’s fate: kissed by the muses at birth, doomed to an early death. The two Tchaikovsky works most tellingly cited say it all: “Lullaby in a Storm” and “None but the Lonely Heart,” both plaintive songs. The Fairy’s Kiss is Stravinsky revisiting his own childhood, confiding his emotional roots.

In 1948 Schoenberg wrote a short essay titled “On Revient Toujours.” It begins by remembering “with great pleasure” a leisurely journey in a Viennese fiacre through the Black Forest – that is, a Nature experience both seductive and frightening. Schoenberg applies this adventure to his recent reversion to an older, tonal style – an occasional desire “to dwell in the old.” “A longing to return to the older style was always vigorous in me,” he admits. “And from time to time I had to yield to the urge.”

If even for Stravinsky and Schoenberg musical retrospection proved inescapable, for Ives, Elgar, and Sibelius – and also for Gustav Mahler – it acquired a new tone: not just an embrace of the past, but a yearning compelled by dislocation from the present: a chronic impulse, exigent and unwilled.

Some two centuries after Johann Sebastian Bach, Ives, Elgar, and Sibelius felt spent. Stravinsky, too, eventually discovered himself in crisis, unable to compose – and opted for Schoenberg’s 12-tone method. But – we can now admit – 12-tone music proved a wrong turn, a dead end.

Straddling a transitional moment they could not command, Ives, Elgar, and Sibelius foretold the terminus of the symphonic canon; they are casualties of uprooted tradition. Significantly, the final contributor to the mainstream orchestral repertoire, Dmitri Shostakovich, composed behind an Iron Curtain that kept modernism and cosmopolitan modernity at bay: he could feast on Bach and Beethoven, Mussorgsky and Mahler. Today, too many new orchestral works sound like makeshift music, erected in sand.

The dialectical tension between present and past, long the mainspring for musical creativity, has gone slack. In Ives, Elgar, and Sibelius, in Stravinsky and Schoenberg, this conundrum, differently manifest, ran its fatal course.

“Three Who Quit” is an excerpt from my book-in-progress “Why Ives?” Another chapter adapts my essay on Ives and Mahler for “The American Scholar.” The’yre both offshoots of the Ives Sesquicentenary, and of the four NEH-funded Ives festivals I co-curated with J. Peter Burkholder.

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers