Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 4

December 27, 2024

Ives and the Erosion of the American Arts

In celebration (yet again) of the Ives Sesquicentenary, I write for the online digital magazine Persuasion:

“Of the crises today afflicting the fractured American experience, the least acknowledged and understood is an erosion of the American arts correlating with eroding cultural memory. Never before have Americans elected a president as divorced from historical awareness as Donald Trump. If Charles Ives is the supreme creative genius of American classical music, it’s partly because, more than any other American composer of symphonies and sonatas, he is a custodian of the American past. A product of Danbury, a self-made Connecticut Yankee, he created a bracing New World idiom steeped in the New England Transcendentalists, in the Civil War, in smalltown patriotic celebrations. His improvisatory bravado, espousing the ‘unfinished,’ equally links to such ragged literary icons as Mark Twain, Herman Melville, and Walt Whitman.”

To read the whole piece, click here.

To watch my Ives film documentary, click here.

December 18, 2024

Abraham Lincoln, Ragtime, and Charles Ives on NPR

Jeremy Denk

Jeremy Denk

Allen Guelzo

Allen GuelzoExcerpts from my most recent “More than Music” show on NPR: “Finding the Common Good – Charles Ives at 150”:

Ives is a self-made Connecticut Yankee, born in 1874, who’s all about seeking common purpose, common sentiment, common good. So at a moment when our nation seems to be coming apart, Ives speaks to us about the things that hold us together – or used to. And yet this year’s Ives Sesquicentenary – remarkably – is mainly being celebrated abroad, by European orchestras.

I’m recently back from a nine-day Indiana University festival — by far the biggest Ives celebration here in the US, with two and three events daily. Among the participants was the pianist Gilbert Kalish, still going strong at the age of 89. Back in the 1970s, when the music of Ives was being discovered half a century after he composed it, Kalish was a key figure in a great awakening. At a public forum on Ives’s piano music, I asked him to reflect upon the fate of Charles Ives in the US today. He suddenly fell into a crestfallen mode and said:

“It’s a kind of cultural tragedy in a way – if you think of it.”

Why would losing touch with Charles Ives seem a “tragedy” for Americans? It’s not just because he’s our most remarkable concert composer. It’s because he embodies what we’re losing touch within the American arts today: cultural memory.

Here’s a perspective on Ives from a distinguished Civil War scholar, Allen Guelzo:

“Ives fills a great blank in the experience of a lot of Americans. We exist in an environment that is so immediate, that is so rootless, which lacks so much in the way of cultural ballast, that we feel sometimes like we’re floating weightlessly. In that respect we live downstream from the cultural shift that occurred in Ives’s lifetime. And Ives responds to it by trying to provide for us ballast in the form of the past and the experience of the past. And that’s different from the way other American composers have come at it. Because a lot of American composers who want to invoke the past really do it almost in a decorative fashion. It’s almost like walking into an antique store. That is not the case for Ives.”

Ives, Guelzo says, negotiated a “cultural shift” at the turn of the twentieth century, when American lives were challenged by new technology, and by a decline in the authority of religion and other sources of moral authority. That reminds him of today. And Allen Guelzo is also reminded, by Charles Ives, of Abraham Lincoln. They both feasted on American memory. They both furnished the kind of cultural ballast with which we’re losing touch.

“Lincoln constantly surprises me. I keep finding entirely different ways of looking at the man and how the man looked at things. I am impressed by his sense of historical capacity, and how the history of the country weighed on him, almost as a burden. He felt a kind of responsibility, especially in 1861 to 1865, that everything was balanced on a pinhead, and he was determined to keep that balance the way it had been designed. He’s determined to do that because the future depends upon it. Not only the future of the country, but the future of the very idea of democracy.”

Abraham Lincoln and Charles Ives, Allen Guelzo says, shared a capacity to inhabit American history. And they rallied people – in their different spheres of government and the arts — to participate in that, and discover common roots.

In some respects Ives parallels his European contemporary Gustav Mahler, intermingling high and low — the philosophic with the everyday. Ives’s Concord Sonata closes with a transcendental Nature reverie remembering Thoreau playing the flute on his doorstep overlooking Walden Pond. But an earlier movement of the same work triggers a blast of ragtime to evoke Nathaniel Hawthorne’s fanciful short stories.

It cannot be coincidental that two of the most notable exponents of the Concord Piano Sonata also relish rags by Scott Joplin and his progeny. One is Steven Mayer, who we’ve been listening to. The other pianist is Jeremy Denk, who’s just released an Ives album on Nonesuch including all the piano and violin sonatas. Ragtime was the rage beginning in the 1890s, when Ives was at Yale and pounded ragtime in theaters and taverns. In fact, ragtime was an essential catalyst for what Denk calls “the whole universe of American popular music.” And he continues:

“Ragtime is a way of taking a pre-existing tune and syncopating it and giving it a new life; it’s an act in which you revive something that’s square and stale.”

European composers, and also American composers, attempted to “harness” jazz – and shackled it with quotation marks. Ives, by comparison, is never slumming or condescending. His deployment of ragtime is torrential, impolite, elemental. Denk experiences in Ives “a tremendous homage” to ragtime, an “oppositional” and “improvisational” abandon. And he cites as a case in point Ives Third Violin Sonata, begun in 1905. It’s one of five works on his new Nonesuch Ives Sesquicentenary release, in which he’s joined by the violinist Stefan Jackiw.

Here’s a LISTENING GUIDE to the whole NPR show – which you can access here:

3:00 — Allen Guelzo on Ives and “cultural ballast”

4:50 — The parade down Main Street: William Sharp and Steven Mayer perform “The Circus Band”

7:00 — “The Alcotts” and the “human faith melody”

12:00 — The sonic sorcery of “The Housatonic at Stockbridge”

22:30 — Jeremy Denk, Ives, and ragtime

30:00 — Slavery, “Old Black Joe,” and the Second Symphony

39:30 — Edie Ives on why her father was “a great man”

42:30 — Allen Guelzo on Ives and Lincoln

44:00 — William Sharp and Steven Mayer perform “Serenity”

November 28, 2024

Remembering Teddy

Teddy died last Sunday after a short, swift illness, probably cancer. He was eleven years old.

My seminal Teddy memory: in the kitchen, during his early adulthood, I off-handedly said: “Mommy’s coming.” Teddy quivered with an anticipatory elation that consumed every particle of his being. This was my first experience of his bewildering linguistic acumen, and of an unadulterated emotional vocabulary that would never cease to surprise and amaze.

Much more recently – about a year ago – I informed my wife Agnes that the elevator was broken again and Teddy would have to take the stairs. This information was not imparted to Teddy. But, as was so often the case, Teddy was listening. When I leashed him and opened the front door to our apartment, he proceeded not to the elevator but to the stairs and began to whimper – he hated the stairs, his paws would slip and slide going up and down. The next day I told Teddy “The elevator is fixed” and he was a happy dog.

Teddy was good friends with Neil and Diane down the hall. Early in this relationship, I informed Agnes that Teddy knew we were about to pay them a visit; he had heard us talking about it. Agnes was skeptical. “Go and look,” I suggested. Agnes poked her head out the door and observed Teddy parked on his haunches in front of 6D. “Speak,” I said. He barked, the door opened, and Teddy entered wagging his tail.

The imagery of Teddy anticipating a visit was repeated many times. We acquired a self-serving habit of informing Teddy of impending “surprises.” The biggest announcements were that Bernie or Maggie – our son and daughter – were arriving. Teddy would position himself downstairs in the lobby, tautly immobilized. His suppressed energy would detonate once Bernie or Maggie appeared. We eventually conceded that we were exploiting his loyalty for our own pleasure. So we would strategize to keep Teddy in the dark – which proved impossible, because he eavesdropped even on phone conversations.

During the years that Agnes worked at Wadleigh High School on West 114 Street, Teddy and I would often meet her after work. Teddy would haul me to the bus stop at the corner of 96th and Central Park West and there inspect each arriving uptown bus. Or Teddy and I would walk 18 blocks to Wadleigh — he knew the way. It mattered not if Agnes was delayed. We sat on a stoop scrutinizing the schoolyard. Not once would Teddy look left or right.

Sometimes Agnes felt too tired or too busy to join us for Teddy’s early evening walk. Teddy would tenaciously object. Almost invariably, Agnes would change her mind.

When I took Teddy to Central Park, I chatted with him about one thing or another. However busy reconnoitering, Teddy would glance up to acknowledge my comments and instructions. In later years, he grew increasingly sociable. He took no interest in other dogs – or squirrels or horses, or the occasional raccoon, or the stray coyote we once saw at a distance. He could shrewdly assess which children and adults would likely succumb to his gaze. For many, it was irresistible. Can I pet your dog? What’s his name? May I say hello? Teddy would waylay passengers emerging from a car. He thought nothing of interrupting the cell phone conversations of strangers.

Of his friends on the block (typically with people whose names I never learned), the oldest and most intense was with Dino the night doorman four buildings down. Our midnight walks would begin with single instruction – “Let’s visit Dino” or (on Saturdays and Sundays) “no Dino.” Teddy accepted the finality of “no Dino” and would proceed across the street to pee. “Let’s visit Dino” meant waiting for Dino to appear and open a locked door. Sometimes Dino was not available and Teddy would cross the street with extreme reluctance. Dino’s wife once asked him: “Do you give him treats?” But Teddy’s friendships were never enticed – except by Teddy himself. When Teddy passed, Dino called him an “angel.” I owe my friendship to Dino to Teddy.

I haven’t mentioned that Teddy was born with a couple of serious medical disorders: myasthenia gravis and mega-esophagus. A miracle drug called mestinon kept him alive. But he could not swallow food or water normally. Like all myasthenia gravis dogs, he ate in a “Bailey chair” which kept his throat vertical.

So we hand-fed Teddy three times daily. The risk that Teddy would mis-swallow was ever present – we would have to pound his sides to help dislodge phlegm and errant food. We belonged to a diligent online community of MG dog owners. Bonding with a dog with special needs is itself a special experience.

Agnes and I never left Teddy alone. If we all travelled together, it was by car with Teddy and his chair; Teddy was far too large to pack on a plane. Last Monday, Agnes and I flew together for the first time in over a decade – to be with Maggie and Bernie in San Francisco. When we return to our New York apartment, we will return to Teddy’s chair, to Teddy’s beds, to Teddy’s medicines and toys and blankets and coats – to all things Teddy except Teddy himself.

His passing leaves an immense void.

November 21, 2024

Lawrence Tibbett and the Fate of American Opera Today

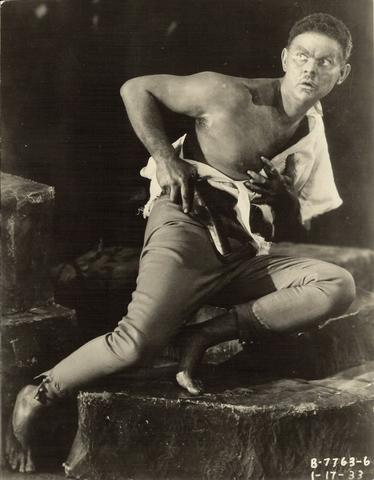

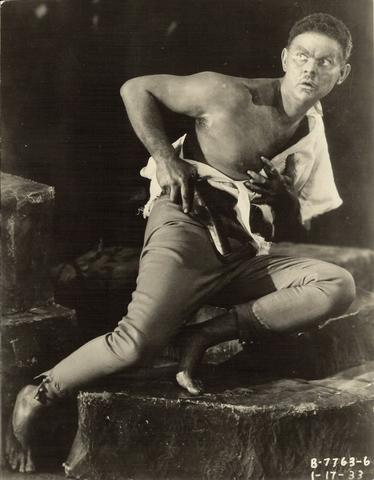

“Singing Black” — Tibbett in “The Emperor Jones” at the Met (1933)

“Singing Black” — Tibbett in “The Emperor Jones” at the Met (1933)Today’s online edition of “The American Scholar” carries my essay on Lawrence Tibbett and how he “prophesied today’s Metropolitan Opera crisis.” You can read it here. An extract follows:

In a recent New York Times “guest essay,” Peter Gelb, the Metropolitan Opera’s embattled general manager, expresses the naïve hope that “new operas by living composers” can make opera “new again.” And he blames critics for being “negative or at times dismissive.” In fact, recent Met seasons have highlighted operas in English composed by Americans. But they’re all recent (the Met still ignores Marc Blitzstein’s Regina [1948], arguably the grandest American opera after Porgy and Bess) and debatable in merit. Works like Terence Blanchard’s Champion and The Fire Shut Up in My Bones, however touted today, will not endure: their craftmanship is makeshift; there is no lineage at hand. And the standard repertoire is increasingly hard to cast with singers capable of projecting musical drama into a 3,850-seat house. In fact, the vast Met auditorium is today an albatross, an emblem of financial duress and artistic crisis.

Of all the many might-have-beens, among the most tantalizing involves Lawrence Tibbett, who seemed a candidate to take over the Met in 1950 – the year an Austrian, Rudolf Bing, was appointed general manager. Though retired from the stage, Tibbett was still widely famous, arguably the foremost singing actor ever produced in the US. As a Verdi baritone, he had more than held his own with pre-eminent Italians. He had starred in Hollywood and on commercial radio, had sung many dozens of recitals annually in cities of every size. American-born, American-made, he embodied a pioneer archetype.

And, no less than Henry Krehbiel [who wrote that opera in the US would remain “experimental” unless and until American works were promoted and embraced], Tibbett was prophetic. He declared opera in America “in grave danger,” entrapped by a “star system” enforced by a social elite. He advocated American opera and opera in English. He urged the substitution of smaller auditoriums, shedding the glamour of opera houses in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco far exceeding in scale European norms. He resisted touring abroad or Italianizing his name. He called for financial incentives for American opera composers. He wrote that “the whole structure of opera must by Americanized if Americans are to support it in the long run.” Ignoring a critical consensus marginalizing George Gershwin as a dilettante, the claimed that Rhapsody in Blue surpassed “in real emotional musical quality half of the arias of standard operatic composers whose works are the backbone of every Metropolitan season.” Singing Gershwin and Cole Porter, Sigmund Romberg and Jerome Kern, singing Lieder in English, he embodied a democratic range of style and repertoire decades ahead of the game. A voluble public advocate, he thundered: “Be yourself! Stop posing! Appreciate the things that lie at your doorstep!”

To access an NPR “More than Music” episode about Lawrence Tibbett, American opera, and “singing Black,” click here.

Lawrence Tibbett and Fate of American Opera Today

“Singing Black” — Tibbett in “The Emperor Jones” at the Met (1933)

“Singing Black” — Tibbett in “The Emperor Jones” at the Met (1933)Today’s online edition of “The American Scholar” carries my essay on Lawrence Tibbett and how he “prophesied today’s Metropolitan Opera crisis.” You can read it here. An extract follows:

In a recent New York Times “guest essay,” Peter Gelb, the Metropolitan Opera’s embattled general manager, expresses the naïve hope that “new operas by living composers” can make opera “new again.” And he blames critics for being “negative or at times dismissive.” In fact, recent Met seasons have highlighted operas in English composed by Americans. But they’re all recent (the Met still ignores Marc Blitzstein’s Regina [1948], arguably the grandest American opera after Porgy and Bess) and debatable in merit. Works like Terence Blanchard’s Champion and The Fire Shut Up in My Bones, however touted today, will not endure: their craftmanship is makeshift; there is no lineage at hand. And the standard repertoire is increasingly hard to cast with singers capable of projecting musical drama into a 3,850-seat house. In fact, the vast Met auditorium is today an albatross, an emblem of financial duress and artistic crisis.

Of all the many might-have-beens, among the most tantalizing involves Lawrence Tibbett, who seemed a candidate to take over the Met in 1950 – the year an Austrian, Rudolf Bing, was appointed general manager. Though retired from the stage, Tibbett was still widely famous, arguably the foremost singing actor ever produced in the US. As a Verdi baritone, he had more than held his own with pre-eminent Italians. He had starred in Hollywood and on commercial radio, had sung many dozens of recitals annually in cities of every size. American-born, American-made, he embodied a pioneer archetype.

And, no less than Henry Krehbiel [who wrote that opera in the US would remain “experimental” unless and until American works were promoted and embraced], Tibbett was prophetic. He declared opera in America “in grave danger,” entrapped by a “star system” enforced by a social elite. He advocated American opera and opera in English. He urged the substitution of smaller auditoriums, shedding the glamour of opera houses in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco far exceeding in scale European norms. He resisted touring abroad or Italianizing his name. He called for financial incentives for American opera composers. He wrote that “the whole structure of opera must by Americanized if Americans are to support it in the long run.” Ignoring a critical consensus marginalizing George Gershwin as a dilettante, the claimed that Rhapsody in Blue surpassed “in real emotional musical quality half of the arias of standard operatic composers whose works are the backbone of every Metropolitan season.” Singing Gershwin and Cole Porter, Sigmund Romberg and Jerome Kern, singing Lieder in English, he embodied a democratic range of style and repertoire decades ahead of the game. A voluble public advocate, he thundered: “Be yourself! Stop posing! Appreciate the things that lie at your doorstep!”

To access an NPR “More than Music” episode about Lawrence Tibbett, American opera, and “singing Black,” click here.

November 13, 2024

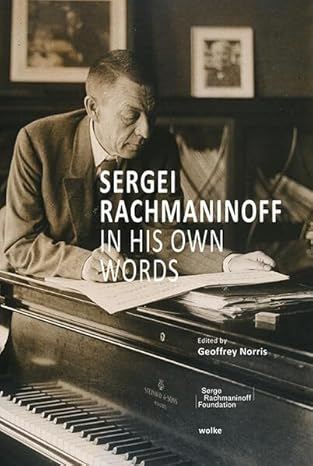

“Rachmaninoff In His Own Words” – A Man of Firm Identity and Principle

A dear friend of mine died recently of a sudden heart attack. I discovered that the only music I found consoling was the slow movement of Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto – the 1929 recording with the composer at the piano, accompanied by Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra.

I am of course aware that many people find this piece maudlin. But Rachmaninoff the pianist is never maudlin. He projects sadness with implacable poise. His expressive inflections are never momentary inspirations; they are governed by a designated template of feeling. He projects a sovereign personality as admirable and imposing as any I can think of in the creative arts.

A new book of Rachmaninoff’s essays and interviews – Sergei Rachmaninoff In His Own Words, edited by Geoffrey Norris – amplifies these observations. I even discovered Rachmaninoff writing about that 1929 recording. But nothing in the book stirred me as profoundly as its preamble. In 1932, Rachmaninoff was one of more than a hundred individuals invited to define “music.” He responded with seven lines in Russian. Translated, they read:

What is music? How can one define it?

Music is a calm moonlight night; a rustling of summer foliage; music is the distant peal of bells at eveningtide. Music is born only in the heart and it appeals only to the heart. It is love!

The Sister of music is Poetry and the Mother is Sorrow!

In the articles and interviews here assembled, Rachmaninoff also testifies that he approaches music “from within.” He writes: “Music should bring relief.” Conducting an orchestra, he experiences an “inner calm”; it reminds him of “driving a motorcar.”

The 1929 concerto recording with Stokowski is a supreme collaboration. Their exchanges are seamless, clairvoyant. Unlike the mix in many modern recordings, the piano is never an exaggerated presence – and Rachmaninoff delights in circulating under the orchestra, then mercurially arising. In the Adagio sostenuto second movement, the famous Stokowski legato – a lava flow – is an ideal medium of expression. The coda to the first movement is also exceptional, with Stokowski’s hyper-sensitive cellos inspiring Rachmaninoff’s sonic imagination. In Rachmaninoff in his Own Words, Stokowski’s orchestra is repeatedly praised as nonpareil. Of the recording of his Second Concerto, Rachmaninoff says (in The Gramophone, April 1931):

“To make records with the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra is as thrilling an experience as any artist could desire. Unquestionably, they are the finest orchestral combination in the world: even the famous New York Philharmonic, which you heard in London under Toscanini last summer, must, I think, take second place. Only by working with the Philadelphians both as soloist and conductor, as has been my privilege, can one fully realise and appreciate their perfection of ensemble.

“Recording my own [Second] Concerto with this orchestra was an unique event. Apart from the fact that I am the only pianist who has played with them for the gramophone, it is very rarely that an artist, whether as soloist or composer, is gratified by hearing his work accompanied and interpreted with so much sympathetic co-operation, such perfection of detail and balance between piano and orchestra. These discs, like all those made by the Philadelphians, were recorded in a concert hall, where we played exactly as though we were giving a public performance. Naturally, this method ensures the most realistic results, but in any case, no studio exists, even in America, that could accommodate an orchestra of a hundred and ten players.

“Their efficiency is almost incredible. In England I hear constant complaints that your orchestras suffer always from under-rehearsal. The Philadelphia Orchestra, on the other hand, have attained such a standard of excellence that they produce the finest results with the minimum of preliminary work. Recently, I conducted their superb recording of my symphony poem, “The Isle of the Dead”, now published in a Victor album of three records which play for about twenty-two minutes. After no more than two rehearsals the orchestra were ready for the microphone, and the entire work was completed in less than four hours.”

Two themes that pervade Rachmaninoff’s public discourse are American music education, which he finds inadequate, and modern music, which he disdains. He praises American orchestras and audiences unstintingly. He calls New York City the “musical capital of the world.” He appreciates the “bold private initiative” of the Boks, who fund the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Curtis Institute. But gifted American music students, he finds, are underserved. They cannot even afford to attend important concerts, because no tickets are set aside for them. And there is no national conservatory, no institutionalization of “the highest and the purest in music radiating from the center.”

(In Russia — including Soviet Russia — an integrated musical community of performers and composers, orchestras and conservatories instilled tradition. Nothing of that sort ever emerged in the United States – although Jeannette Thurber, in founding her National Conservatory of Music and in 1892 naming Antonin Dvorak to lead it, had that in mind. Thurber’s efforts to secure federal funding went nowhere. And Dvorak’s complaints about American music education forecast Rachmaninoff’s.)

In a 1925 Musical Courier article, we learn something pertinent about Rachmaninoff’s regard for another “radiating center” — Konstantin Stanislavsky’s legendary Moscow Art Theatre:

“Rachmaninoff is very devoted to the theatre. In his youth he was a great admirer of Chekhov. He is a friend of the players of the Moscow Art Theatre. I remember what a stimulating sight I saw one afternoon in the Artists’ room after a Rachmaninoff concert at Carnegie Hall, New York. There stood in a corner a huge glittering laurel wreath in green, gold and white, presented to the master pianist with the cordial greetings of the Moscow Art Theatre. The actors and actresses from the greatest theatre of the world led by stalwart and handsome Stanislavsky, almost surrounded him. Some of the men kissed him, and he them in real Russian style. They exchanged a few words in the tempo of a chant before an altar. Then for a minute or two they spoke not a word. The Moscow players simply looked at the great Moscow musician in reverent silence. Such devotion, such poise, such childlike sincerity, I never saw before, even on the stage of the Moscow Art Theatre. The actors surpassed themselves. Then they gently walked away one by one, like so many children, sad at parting from their playmate. The master’s gaze was fixed on them, and he waved at the last actor who looked back as he went out of the door. I watched this bit of drama in life with breathless wonder, and I am not ashamed to admit that the sanctity of the scene moved me to tears. And from the quick movement of his eyelids I could notice that the master’s eyes were not altogether dry either. I shall never forget this one act play of the Moscow Art Theatre, Rachmaninoff playing the part of the hero. It was more than a play, it was a sacrament.”

But perhaps the most abiding motif in Sergei Rachmaninoff In His Own Words is Rachmaninoff’s contempt for musical modernism. For him, beauty in music is an absolute criterion, and music’s supreme ingredient is melody. In this regard, he pursues a polemic whose best-known manifestation, in English-speaking countries, was once Constant Lambert’s Music Ho – A Study of Music in Decline (1934). Intolerant of Igor Stravinsky, Lambert’s anoints Jean Sibelius his contemporary composer of choice.

But Sibelius wrestled with modernism in his Fourth and Fifth Symphonies, anxious and insecure, trying to catch up. Serge Prokofiev, too, strove to be a modernist in competition with Stravinsky. Then he called it quits, returning to Russia and his own Russian Romantic roots.

In 1930, Rachmaninoff revealingly recalled meeting Tchaikovsky “some three years before he died. . . . Tchaikovsky at that time was already world-famous, and honoured by everybody, but he remained unspoiled. He was one of the most charming artists and men I ever met. He had an unequalled delicacy of mind. He was modest, as all really great people are, and simple, as very few are. (I met only one other man who at all resembled him, and that was [Anton] Chekhov.)”

Judging from his interviews and essays, Rachmaninoff was never tortured by modernism. He never wrestled with its challenge to tradition. A man of firm identity and principle, he simply waited it out.

And his music prevails.

Related blogs: Rachmaninoff “the homesick composer”; Rachmaninoff’s valedictory “Symphonic Dances.”

October 22, 2024

“Dear Daddy” — What Kind of Man Was Charles Ives?

What kind of man was Charles Ives? Based on the testimony of those who knew and met him, I would say: a great man. And the greatest such testimonial was left by his daughter, Edie, in a letter she wrote to her father in 1942 on the occasion of his sixty-eighth birthday.

I discovered Edie’s letter thanks to Tom Owens’s Selected Correspondence of Charles Ives (2007). Edie’s tribute is so moving, so illuminating, that I instantly thought to create a concert/playlet around it. The result was “Charles Ives: A Life in Music,” at 50-minute presentation I have many times produced featuring William Sharp – a peerless exponent of Ives’s songs. We use those songs to tell the story of Ives’s life. When we get to Ives’s retirement from business and music – long years of precarious health — we arrive at Edie’s letter. It stuns audiences to tears.

For Ives’s 150th birthday, October 20, WWFM – the most enterprising classical-music radio station I know – produced a two-hour Ives tribute that generously samples “Charles Ives: A Life in Music” as performed last September 30 to launch Indiana University’s nine-day, NEH-supported Ives Sesquicentenary festival. Edie’s letter was read by Caroline Goodwin – and you will find it about 70 minutes into the show. Here’s the text in part:

Dear Daddy,

You are so very modest and sweet Daddy, that I don’t think you realize the full import of the words people use about you, “A great man.”

Daddy, I have had a chance to see so many men lately – fine fellows, and no doubt the cream of our generation. But I have never in all my life come across one who could measure up to the fine standard of life and living that you believe in, and that I have always seen you put into action no matter how many counts were against you. You have fire and imagination that is truly a divine spark, but to me the great thing is that never once have you tried to turn your gift to your own ends. Instead you have continually given to humanity right from your heart, asking nothing in return; — and all too often getting nothing. The thing that makes me happiest about your recognition today is to see the bread you have so generously cast upon most ungrateful waters, finally beginning to return to you. All that great love is flowing back to you at last. Don’t refuse it because it comes so late, Daddy. . . .

And don’t ever feel you’ve been a burden to mother or me. You have been our mainstay, our guide and the sun of our world! We’ve leaned against you and turned to you for everything – and we have never been made to turn away empty-handed.

There follows an unforgettable performance of Ives’s song “Serenity,” with Bill Sharp accompanied by Steven Mayer, himself long an eminent Ives advocate. In fact, just before we get to Edie’s letter, we hear a stirring Steve Mayer performance of “The Alcotts,” from Ives’s Concord Piano Sonata.

The tail end of the WWFM show features excerpts from a prior Ives Sesquicentenary festival, at the Brevard Music Festival last July. First we hear the final pages of “Thoreau,” ending the Concord Sonata, performed by Michael Chertock – another astonishing reading. Then we explore how Ives used Stephen Foster’s “Old Black Joe” (here sung by Paul Robeson) to eloquently express “sympathy for the slaves” in the finale of his Second Symphony – the rousing climax of which is performed by Brevard’s collegiate Sinfonia (one of three Brevard orchestras) led by Delta David Gier.

The commentary, throughout, is by me, Bill McGlaughlin, J. Peter Burkholder, and two of the featured performers: Bill Sharp and Michael Chertock. It all happened thanks to WWFM’s David Osenberg, who possesses the energy and enterprise to do things differently.

Here’s a Listening Guide (click here to access the two-hour WWFM show):

Sung by Charles Ives (1943):

“They Are There”

Sung by William Sharp accompanied by Steven Mayer:

“The Circus Band”

“Memories”

“Feldeinsamkeit” (as set both by Johannes Brahms and Ives)

“Remembrance”

“The Greatest Man”

“The Housatonic at So Stockbridge”

Performed by Steven Mayer:

“The Alcotts” from the Concord Sonata

Read by Caroline Goodwin:

“Dear Daddy”

Sung by William Sharp accompanied by Steven Mayer:

“Serenity”

Performed by Michael Chertock:

“Thoreau” (final pages) from the Concord Sonata

Sung by Paul Robeson:

“Old Black Joe”

Performed by Delta David Gier conducting the Brevard Sinfonia

Ives’s Symphony No. 2 (closing minutes)

October 10, 2024

“Very Likely the Most Important Film Ever Made about American Music”

During the pandemic, unable to produce concerts, I found myself making six documentary films linked to my book Dvorak’s Prophecy. The most necessary of these was and is “Charles Ives’s America.” The Dvorak’s Prophecy films were picked up by Naxos as DVDs – which almost no one purchases any more. For the current Ives Sesquicentenary, however, Naxos has streamed the Ives film on youtube – so it’s now available for free, right here.

“Charles Ives’s America” features extraordinary visual renderings by my longtime colleague Peter Bogdanoff. The necessity of the film was articulated by JoAnn Falletta, who as music director of the Buffalo Philharmonic since 1999 has been a staunch and creative advocate of neglected American repertoire:

“’’Charles Ives’ America” is very likely the most important film ever made about American music. Horowitz moves Ives from the fringes squarely to his position as the seminal composer of our country. The genius of Ives is astonishing, and his creativity without equal. The presentation of his life and world is visually beautiful and deeply moving, but at the center of this film experience is his music. We are amazed by its uncompromising originality, its honesty, its poetic impulse, its clear-eyed humor, and, in the end, its absolute beauty. I fell in love with Ives all over again.”

In a review of all six Dvorak’s Prophecy films in The American Scholar, Mark N. Grant wrote:

“As a group, these videos sweep together a vast canvas of Americana . . . All are interestingly told. The video documentaries eschew the Ken Burns style of rapid montage and instead go into deep focus. Talking heads speak at length rather than in sound bites. The music . . . is not interrupted by hyperkinetic visual montages or multiple voiceovers. It’s the documentary equivalent of ‘slow food’; there is room to absorb and think and remember. . . . The videos should be widely purchased and used by educators and institutions throughout the country to proselytize the unconverted. If classical music is going to survive and thrive, we need zealous advocates like Joseph Horowitz to continue beating the drum.”

My favorite sequence from the Ives film (at 27:30) features The Housatonic at Stockbridge, with the conductor/scholar James Sinclair narrating the magical layering of Ives’s sublime depiction of water and mist.

The film’s participants, additinal to Jim, are the Ives scholars J. Peter Burkholder and Judith Tick, and the baritone William Sharp – a peerless Ives singer whose live performances (with pianist Paul Sanchez) are heard throughout. The other music comes from Naxos recordings by Sinclair, Kenneth Schermerhorn, and Steven Mayer (whose Concord Sonata was named one of the three best recorded versions by Gramophone magazine). Supplementary funding was furnished by the Ives Society.

Naxos’s commitment to Ives bears stressing. It dates back decades, when I had occasion to introduce Klaus Heymann – who founded Naxos in 1987 and is an unsung hero of American music — to the late H. Wiley Hitchcock, then a seminal Ives authority.

Naxos’s “American Classics” series, in which Ives prominently figures, is itself a landmark initiative. Only on Naxos can you hear George Templeton Strong’s hour-long Sintram Symphony (1888) – a high Romantic American opus in the Liszt/Bruckner mold, triumphantly premiered by Anton Seidl in 1892 and subsequently forgotten (Neeme Jarvi considers the slow movement the most beautiful ever composed by an American). Another essential “American Classics” recording is Benjamin Pasternack’s gripping traversal of Aaron Copland’s valedictory: the non-tonal Piano Fantasy. More recently, Arthur Fagin’s Naxos recording of William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony has triggered wide and belated recognition of the most accomplished “Black symphony” of the interwar decades. And Naxos has issued stellar performances of our most neglected composer: the Indianist Arthur Farwell, who comes closer to Bartok than any other American.

The Naxos Ives catalog totals no fewer than 19 releases, including a fresh set of “Orchestral Works” scheduled for November 1. The novelties on this recording, conducted by James Sinclair, include orchestral transcriptions of Schumann and Schubert that Ives composed while a student at Yale. Sinclair’s completion of an Ives’s torso, a theater-orchestra version of his irresistible song “The Circus Band,” is again irresistible. So is the “March No. 3” incorporating “My Old Kentucky Home.”

Here’s a Listening Guide to the Ives film:

00:00 — Ives the song composer (“The Circus Band” and “Memories”), with commentary by William Sharp

13:00 — Ives at Yale; Symphony No. 1

21:00 — Ives and his wife Harmony; “The Housatonic at Stockbridge”

32:00 — Symphony No. 2 and its sources, with commentary by J. Peter Burkholder

44:00 — “The St. Gaudens at Boston Commons” and sources

55:00 — The Concord Piano Sonata

1:06 — Ives as a “moral force” — not a modernist; Edie Ives extols her father as “a great man”

1:12 — Judith Tick on Ives the Progressive

1:18 — Canonizing Ives as a “self-made American genius”

1:20 — “Serenity”

September 26, 2024

A Revelatory Visual Rendering of an American Musical Masterpiece

Of the masterpieces of American classical music, among the least appreciated and least performed is Three Places in New England by Charles Ives.

There is an obvious reason: the piece fails in live performance unless it’s contextualized. In particular, the first movement – “The ‘St. Gaudens’ in Boston Common” – makes little impression unless an audience gleans its inspiration: Augustus St. Gaudens’ bas relief of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw’s historic Black Civil War regiment, most of whose members perished in a heroic assault on Fort Wagner in South Carolina. Ives here singularly produces a ghost dirge suffused with weary echoes of Civil War songs, work songs, plantation songs, church songs, minstrel songs. It is an intense patriotic tribute eschewing the stentorian.

Movement two – “Putnam’s Camp” – uncorks a rambunctious July 4 celebration, as processed by an eagerly imaginative child. Movement three – “The Housatonic at Stockbridge” – is the most majestic, most eloquent American musical rendering of the sublime in Nature. It’s all iconic Americana, never glib, never touristic. But it risks sounding esoteric.

A remedy: Peter Bogdanoff’s ingeniously poetic “visual presentation” for Three Places in New England, which premieres on October 5 at the Ives Sesquicentenary Festival at Indiana University/Bloomington as part of an Ives concert by the Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Arthur Fagen. The same concert will incorporate commentary and source tunes for Three Places and Ives’s Symphony No. 2. The visual presentation will next be seen Feb. 22 at an Ives Sesquicentenary concert given by the Chicago Sinfonietta conducted by Mei-Ann Chen.

For “The St. Gaudens,” Ives furnished a poem reading in part:

Moving—Marching—Faces of Souls!

Marked with generations of pain,

Part-freers of a Destiny,

Slowly, restlessly—swaying us on with you

Towards other Freedom! . . .

Moving—Marching—Faces of Souls!

Ives’s own program note for “Putnam’s Camp” reads:

Once upon a “4th of July,” some time ago, so the story goes, a child went there on a picnic. Wandering away from the rest of the children past the camp ground into the woods, he hopes to catch a glimpse of some of the old soldiers. As he rests on the hillside of laurel and hickories, the tunes of the band and the songs of the children grow fainter and fainter;—when—“mirabile dictu”—over the trees on the crest of the hill he sees a tall woman standing. She reminds him of a picture he has of the Goddess Liberty,—but the face is sorrowful—she is pleading with the soldiers not to forget their “cause” and the great sacrifices they have made for it. But they march out of camp with fife and drum to a popular tune of the day. Suddenly a new national note is heard. Putnam is coming over the hills from the center,—the soldiers turn back and cheer. The little boy awakes, he hears the children’s songs and runs down past the monument to “listen to the band” and join in the games and dances.

(At the forthcoming IU performance, “The St. Gaudens” will be preceded by a reading of Ives’s poem by William Sharp; “Putnam’s Camp” will be preceded by a reading of Ives’s note, again by Bill; “The Housatonic at Stockbridge” will be preceded by a performance of the song by Bill and Steven Mayer. In the video above, Ives’s song is performed by Bill and Paul Sanchez.)

Supported by the NEH Music Unwound consortium, the Indiana University Ives Sesquicentenary Festival (Sept. 30 to October 8) is curated by J. Peter Burkholder and myself. Participants include pianists Steven Mayer, Jeremy Denk, and Gilbert Kalish, the Pacifica String Quartet, university ensembles, and scholars from a variety of disciplines. All concerts are free. For further information – and a 50-page Program Companion – click here.

September 24, 2024

The Downfall of Classical Music

If you’re in the mood for a rollicking conversation about the downfall of classical music in the US, check out this podcast conversation I recently had with the terrific conductor Kenneth Woods (who’s based in the UK rather than the US, in which he deserves a music directorship of consequence).

My favorite sentence:

“Those chickens that are now coming home to roost are the chickens I’ve been writing about since the 1980s [in Understanding Toscanini], for which I was initially vilified. But now that I’ve turned into a prophet, I’m simply ignored.”

These, in sequence, are the topics at hand:

1.The grim situation of the arts in the UK right now: no money.

2.My visit to South Africa, and how classical music there is evolving with notable Black leadership (thanks in part to Nelson Mandela).

3.My ruthless analysis of the interwar popularization or “democratization” of classical music in the US, which anointed Arturo Toscanini “the world’s greatest musician” even though he wasn’t a composer. This was a commercial operation headed by David Sarnoff (RCA/NBC) and Arthur Judson (the managerial powerbroker who declared that “the audience sets taste”). Dead European masters — easiest to merchandize — were prioritized. Amateur music-making was discouraged in favor of broadcasts and recordings by the experts.

4.A barrage of pointed questions and observations from Ken attempting to figure out Toscanini’s primacy (“why he won”). Toscanini’s appeal to mass taste.

5.Ken proposes a thought experiment – subtract Toscanini from the story of classical music and what do you get? You get Serge Koussevitzky and Leopold Stokowski. And where might that have led? I marvel in passing: “Stokowski didn’t care about integrity, it wasn’t part of his vocabulary.”

6.Dmitri Mitropoulos, and why his 1940 Minneapolis Symphony premiere recording of Mahler’s First seems to me the most remarkable Mahler recording ever made – and unthinkable today (with choice audio examples)

7.Ken asks: What if Leonard Bernstein had been appointed Koussevitzky’s successor in Boston in 1950, rather than winding up at the New York Philharmonic (which had no pertinent tradition of espousing American music)? Ken answers himself: “It would have changed the repertoire of all American orchestras.”

8.My own favorite thought experiments:

— What if Gustav Mahler had premiered Ives’s Second Symphony with the New York Philharmonic?

— What if George Gershwin had lived as long as Aaron Copland?

Either would have fundamentally changed the trajectory of American classical music.

9.What if Anton Seidl – who was bigger than Toscanini or Bernstein in New York City – had not died in 1898 at the age of 47? There would have been an annual Wagner festival in Brooklyn as pedigreed at Bayreuth – limiting the damage inflicted on Wagner by Hitler and Winifred Wagner.

10. “I can’t imagine life without cultural memory, although we’re beginning to get a glimpse.” Today’s “makeshift music,” sans lineage or tradition – “eagerly acquisitive and open-eared.”

Today’s famous instrumentalists sans lineage or tradition –vs Sergei Babayan and Daniil Trifonov, who perform Rachmaninoff “in full awareness of a tradition of Russian composition and performance.”

11.The Metropolitan Opera’s “worst ever” Carmen

12.Leonard Bernstein’s capacious vision, revisited today.

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers