Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 6

August 5, 2024

When Charles Ives Wrote a Song as Magnificent as Brahms’s

In the remarkable absence of any suitable acknowledgement of the Charles Ives Sesquicentenary by our nation’s slumbering orchestras, it has fallen to the National Endowment for the Humanities to celebrate the 150th birthday of America’s greatest creative genius in the realm of classical music.

In its latest embodiment, the NEH Music Unwound consortium, which I have directed for a dozen years, is mainly dedicated to four Ives festivals. The first of these has just transpired at the Brevard Music Festival. Music Unwound contextualizes topics in American classical music. (My NPR “More than Music” programs, which do the same, are also NEH-funded via Music Unwound.) The video clip posted above samples “Charles Ives: A Life in Music,” which uses Ives’s songs to tell his story.

This little theater piece, which I created a decade ago, features a supreme Ives interpreter: the baritone William Sharp. The excerpt here posted, from the July 15 Brevard performance (with pianist Deloise Lima and actress Allison Pohl), juxtaposes two settings of Hermann Allmers’ poem “Feldeinsamkeit” – the famous one by Brahms (1882) and another by the 23-year-old Yale composition student Charles Ives that, incredibly, is just as good.

This exercise deserves to banish the notion – once pervasive — of Ives the gifted dilettante or “primitive.” As Ives himself noted (a reminiscence quoted by Bill prior to singing the two songs), his setting is quite different from Brahms’. The “active tranquility” of Nature, here evoked, became a signature Ives trope. Ives’s Schumanesque piano accompaniment incorporates active particles of harmonic grit not to be found in Schumann.

Ives pertinently wrote: “To think hard and deeply and to say what is thought, regardless of consequences, may produce a first impression . . . of great muddiness . . . The mud may be a form of sincerity.” He endorsed the “mud and scum” Ralph Waldo Emerson extolled in his poem “Music”: “There alway, alway something sings.” “Feldeinsamkeit,” “Remembrance,” “The Housatonic at Stockbridge,” “Thoreau,” and other outdoor reveries are in Ives invariably discordant, however faintly. The water, the ether are never wholly limpid; harmonic and textural impurities abound. Ives’ visions of river and meadow, woods and mountain-top are layered with Emersonian mud and scum: active particles of sound; actives particles of memory. It speaks volumes that Ives’ favorite painter was J. M. W. Turner, whose obscurely layered landscapes resist clarity.

The poetic text for “Feldeinsamkeit,” in English, reads:

I rest at peace in tall green grass

And gaze steadily aloft,

Surrounded by unceasing crickets,

Wondrously interwoven with blue sky.

The lovely white clouds go drifting by

Through the deep blue, like lovely silent dreams;

I feel as if I have long been dead,

Drifting happily with them through eternal space.

The Brevard festival also included a contextualized performance of Ives’ Concord Piano Sonata (magnificently played by Michael Chertock) and of the transcendent finale of his Second String Quartet. And there was an orchestral concert (led by Delta David Gier) featuring Ives’s Second Symphony prefaced by some of the songs, familiar and not, he adapts. My terrific partner in these presentations was J. Peter Burkholder, our pre-eminent Ives scholar.

Upcoming are Music Unwound Ives festivals via Indiana University/Bloomington (September 30 – August 8), Bard College’s The Orchestra Now/Carnegie Hall (November 9, 16-17, 21), and the Chicago Sinfonietta/Illinois State University (March 19-22, 2025).

The first of these – including the premiere of a “visual presentation” of Ives’ Three Places in New England created by Peter Bogdanoff – will be the most ambitious Music Unwound festival ever mounted, with some three dozen events; for complete IU program information, click here.

In addition, The American Scholar will be creating an online Ives Sequicentenary program companion. And I’ll be dedicating my November NPR “More than Music” show to Charles Ives, born 150 years ago this October.

July 9, 2024

Stravinsky in Exile — A New View

The current issue of the New School’s quarterly journal “Social Research” is dedicated to the topic “Exile.” I’m pleased to have contributed something on Igor Stravinsky – suggesting that his Symphony in Three Movements, composed in Los Angeles in response (sort of) to World War II, “complexly monograms its composer’s layer upon layer of identity,” disclosing “a condition of exile equally challenged and resourceful.”

I add: “Had Stravinsky less cause for resilience—had there been no Bolshevik Revolution, no world upheaval—he might have left a musical legacy less intriguingly textured with self-denial and reinvention, less mediated by rationalization, more sustained in the elemental energies powering his initial creative surge [i.e., The Firebird, Petrushka, The Rite of Spring, Les noces.]”

You can access the full article here. You can access the full issue (I recommend Jacques Rupnik on “Milan Kundera’s Liberating Exile” in Paris) here. What follows is a sizable chunk of my article (which I wrote as a sequel to my book “The Propaganda of Freedom: JFK, Shostakovich, Stravinsky, and the Cultural Cold War”) if you’d like an overview:

In the decades after World War I, Stravinsky was considered by many the supreme contemporary composer, transcending nationalism, articulating or adapting to changing aesthetic fashions. But the waning of modernism invites new perspectives on Stravinsky, on the effects of exile. . . .

In his polemics, Stravinsky in exile insisted on the liberating autonomy of the creative act. But the tangled history of the Symphony in Three Movements suggests a composition process that was less than fluent. The [New York] Philharmonic’s “victory symphony” commission . . . proved surprisingly (if secretly) inspirational. . . .

It would not be a stretch to treat Ingolf Dahl’s program note for the Symphony in Three Movements as one in a series of “assisted” Stravinsky writings, alongside the autobiography, the Poetics, and the conversations with [Robert] Craft. The combative, defensive tone is all too familiar. A pregnant example is Dahl’s insistence that it will “one day be universally recognized” that Stravinsky’s Hollywood home, “regarded by some as an ivory tower,” was “close to the core of a world at war.” And yet if the Symphony in Three Movements is partly to be regarded as an engaged response to World War II, its ivory-tower impersonality becomes an incongruously defining trait. The wartime output of others—think of Prokofiev’s Seventh Piano Sonata (1942), Schoenberg’s Ode to Napoleon (1942), Arthur Honegger’s Third Symphony (1946)—is enraged, mournful, consoling. Stravinsky’s militancy, however stirring, is merely descriptive.

Shostakovich is the obvious antipode. He directly experienced the horror of the siege of Leningrad. His musical response, in the Seventh Symphony, was exigent, driven, tidal—and fundamentally interior. . . . Shostakovich himself insisted—pace Stravinsky—upon the moral properties of music.

This reading of Shostakovich as a moral beacon was little heard in the West during the ensuing Cold War decades, when Russia again became the enemy. The Cold War cultural mantra emanating from the White House and the State Department—what I have termed the “propaganda of freedom”—was that only “free artists” in “free societies” could produce lasting artistic achievements. Shostakovich, accordingly, was dismissed as a Soviet stooge, a shackled musical anachronism. Stravinsky, concomitantly, became a free-world icon. . . .

In 1954 Shostakovich was afforded a rare opportunity to share his own view of artistic “freedom” with the New York Times. As he was speaking directly to Harrison Salisbury, the Times’s Moscow bureau chief, the words were his—as “passed by Soviet censors.” He said: “The artist in Russia has more ‘freedom’ than the artist in the West.” The reason? He enjoys, Salisbury paraphrased, “what might be described as a ‘principled’ relationship to society and to the party,” versus a “haphazard” relationship to society, as in Western nations. He is accorded “status” and “a defined role.” . . .

Salisbury was impressed by Shostakovich’s “honesty and sincerity.” It was too much for his editors, who published a “contrasting view” alongside Salisbury’s “Visit with Dmitri Shostakovich.” This was “Music in a Cage” by one Julie Whitney, who proposed as a “very serious question” whether Soviet composers “might not use their talent more successfully if they were out of the ‘gilded’ cage in which Shostakovich declares they are so content.” Doubtless there were many occasions when Shostakovich found “too much attention” being paid to his music. And there were times when it was not “played all over Russia.” Conversely, “too little attention” is plainly something Stravinsky sometimes experienced in the United States. If he had no one telling him what to do, and why, he was susceptible to feeling ignored, unappreciated, misunderstood. In truth, whether or not an “ivory tower,” his fastidiously self-contained Los Angeles study at times conferred “too much freedom”—a freedom not to matter. . . .

Of the prominent Russian artists who wound up in the United States, two who “became Americans” were the conductor Serge Koussevitzky, who established Tanglewood as an indispensable laboratory for American music, and the choreographer George Balanchine, who Americanized Russian classical ballet. At the opposite extreme was the pianist and composer Sergey Rachmaninoff, who (notwithstanding an affinity for the jazz genius Art Tatum) remained incorrigibly Russian in his habits and musical predilections. More than Koussevitzky or Balanchine, more than Rachmaninoff, more than was readily apparent, Stravinsky was at all times pulled in multiple directions. Responding to an invitation from the New York Philharmonic—an invitation irresistible yet confounding, even obtuse—he first culled musical pages from a drawer. Then—as he would eventually disclose with tortured caveats—he resorted for inspiration to newsreels of World War II. The resulting “symphony,” not really a symphony, proved both exhilarating and curious, evasive and emphatic, elusive and visceral. It complexly monograms its composer’s layer upon layer of identity. It discloses a condition of exile equally challenged and resourceful.

Had Stravinsky less cause for resilience—had there been no Bolshevik Revolution, no world upheaval—he might have left a musical legacy less intriguingly textured with self-denial and reinvention, less mediated by rationalization, more sustained in the elemental energies powering his initial creative surge.

June 14, 2024

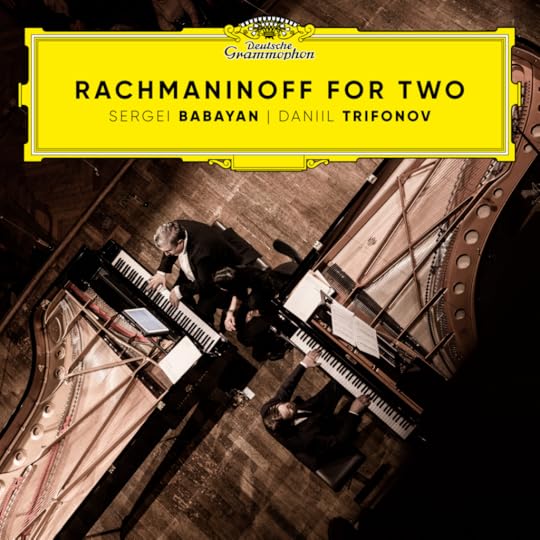

“A Validation Overwhelming and Unprecedented” — Babayan and Trifonov Perform Rachmaninoff

Today’s on-line “The American Scholar” includes something of mine on a magnificent new recording of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s “Symphonic Dances” – and why it matters. You can read the whole thing here.. An extract follows:

Rachmaninoff left two versions of the Symphonic Dances: one for orchestra, the other for two pianos. He premiered the latter, privately, with Vladimir Horowitz. What that sounded like we can only guess. But he also inadvertently left a third version – which eventually became the biggest classical music find of recent decades. And now we have another find: a seminal new DG recording, by Sergei Babayan and Danill Trifonov, that realizes in full the magnitude of Rachmaninoff’s musical leave-taking.

Because Rachmaninoff refused to permit broadcasting or recording of his live performances, we only have his RCA recordings: studio jobs. But on December 21, 1940, the conductor Eugene Ormandy privately recorded Rachmaninoff playing through the Symphonic Dances in preparation for the Philadelphia Orchestra’s premiere performance the following month. This “third version” was released in 2018 as part of a three-CD Marston Records set titled “Rachmaninoff Plays Symphonic Dances.” As I wrote in a review for The Wall Street Journal: “The result is one of the most searing listening experiences in the history of recorded sound. . . As privately imparted to Ormandy, Rachmaninoff’s impromptu solo-piano rendering . . . documents roaring cataracts of sound, massive chording, and pounding accents powered by a demonic thrust the likes of which no studio environment has ever fostered.” It equally registers a trembling undertow of memories faraway and yet omnipresent.

This unprepared, off-the-cuff 26-minute rendition of a 35-minute composition is also necessarily hit and miss, and full of gaps. It sets a towering bar; it documents a lost world. But it is incomplete. The new Babayan/Trifonov recording is in no way a replica. . . . Authentically rendered by Babayan and Trifonov, however, are Rachmaninoff’s magisterial fluidity of tempo and pulse, the heroic range of dynamics, the convulsive ebb and flow, seething and poignant, of an epic confessional. It is a validation overwhelming and unprecedented.

I also write:

In 1952, the Central Intelligence Agency covertly supported an unprecedented international arts festival lavish in cost and purpose: “Masterpieces of the Twentieth Century.” It took place in Paris over the course of a full month. The mastermind was Nicolas Nabokov, Secretary General of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, then the major instrument of American Cold War cultural propaganda.

Nabokov’s premise was that the United States had displaced Europe and Russia as the reigning home for the Western arts. And the twentieth century’s presiding genius, for Nabokov, was his friend Igor Stravinsky, resident in Los Angeles (and like Nabokov living in self-imposed exile from his Russian homeland). Stravinsky dominated the repertoire for Nabokov’s myriad Paris festival performances. Nabokov’s concept was to celebrate “free artists” – cosmopolites liberated from parochial national schools and from the oppressive Soviet yoke. His larger claim – that only “free societies” produce great art, was the fundamental cultural premise of the CIA, State Department, and White House. (In my book The Propaganda of Freedom: JFK, Shostakovich, Stravinsky and the Cultural Cold War, I dub this counter-factual Cold War doctrine the “propaganda of freedom.”)

Nabokov’s favorite case in point was Dmitri Shostakovich. As a widely acknowledged expert on Soviet culture, he influentially denigrated Shostakovich as a Soviet stooge (and named Vittorio Rieti and William Schuman composers of greater consequence). Of the hundreds of compositions programed in Paris in 1952 (by the leading opera companies of Vienna and London, by the New York City Ballet, and by orchestras from Boston, West Berlin, Paris, Geneva, and Rome), Shostakovich was represented by a single piece: a suite from his opera Lady Macbeth. Nabokov chose it because this, notoriously, was the subversive “muddle” that enraged Stalin and provoked a musical crackdown. Wholly unnoticed was that another Russian composer of consequence, like Stravinsky living in the US, was not played at all. This, of course, was the late Sergei Rachmaninoff, written off as a hopeless anachronism.

Today, Nabokov is the anachronism.

To read my “American Scholar” review of a recent Rachmaninoff biography, click here.

To read my “American Scholar” essay on “ripeness” in musical performance, click here.

To read my previous blogs about Sergei Babayan, click here and here.

June 12, 2024

Native America and American Music on NPR: “A Battleground”

This Hamms Beer commercial, which I vividly remember from childhood and our brand-new black-and-white TV, signals “Indian music” with a steady tom-tom beat. The tune (and its tom-tom) adapts the Dagger Dance in Victor Herbert’s opera Natoma. The words – “From the Land of Sky Blue Waters” – reference a once popular concert song by Charles Wakefield Cadman. Both Herbert’s opera and Cadman’s song belong to the “Indianist” movement in American music – the topic of my latest NPR “More than Music” installment: “Native American Inspirations.”

“This tale in its totality,” as I remark at the top of the show, “is a battleground. It actually holds up a mirror to the discontinuity and mistrust that plague the American experience today. But it also incorporates some pretty remarkable music – some of which, you might say, is more or less ‘cancelled’ by present-day sensitivities.”

Unpacking it all, I confer with Timothy Long, who heads the opera program at the Eastman School of Music. Both his father, who was Muskogee Creek, and his mother, who was Choctaw, spoke English as a second language. His mother had been raised in an Indian orphanage in Oklahoma, after which she was moved to an Indian sanatorium. She was so bored there that she began to listen to Beethoven sonata recordings played by Wilhelm Kempff and Alfred Brendel – the music with which Long grew up. So Tim Long lives two musical lives. He also prefers not to listen to the Indianist composers. His reasoning, which he eloquently expounds, has nothing to do with “appropriation” or “permission.” Rather, he says: “We still don’t get recognition – we’re not in the history books, people know nothing about us. This really makes it very difficult to me to listen to the Indianists. We were being occupied, and the occupiers were celebrating us with our music.”

And yet I have long made the music of Arthur Farwell – the most sophisticated of the Indianists — a cause. He seems to me the closest thing to an American Bela Bartok. And he spearheaded a thirty-year chapter in American music that – make of it what you will — is a significant component of our nation’s cultural history.

As it happens, the pianist who has most recorded the Indianist compositions of Farwell is herself Native: Lisa Cheryl Thomas, whose ancestry is Cherokee. She uses word like “authentic” and “informed” when she discusses Farwell. She also says: “I feel we owe a great gratitude to the [non-Native] ethnographers and to the Indianists, especially Farwell. . . . And it’s my goal to keep promoting this with my concerts so that Native American music has a lasting legacy in the fine arts.”

Starting with Louis Ballard (1931-2007) ,whose music I also sample, a growing number of Native American composers have taken up the challenge of marrying Native American sources with the Western concert tradition. On my NPR show, we hear a tribute to Crazy Horse by Jerod Impichchaachaaha’ Tate. It’s performed by Delta David Gier and the South Dakota Symphony, whose “Lakota Music Project”, now more than a decade old, has fostered musical collaborations with Lakota musicians.

I conclude: “Would that a coming to terms with Native America – with the cultural vigor and desolate ordeal of this country’s first inhabitants – could enrich a more harmonious America to come. In truth, that day still seems far distant. But we have at least put far behind us the tom-tom beat of that Hamms Beer commercial with which I grew up.”

LISTENING GUIDE:

2:06: Victor Herbert’s “Dagger Dance” (1911)

5:30: The Scherzo from Dvorak’s New World Symphony (1893), inspired by the Dance of Pau-Puk Keewis in Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha

7:00: Arthur Farwell’s Pawnee Horses (1904), performed by pianist Benjamin Pasternack

8:25: Farwell’s choral Pawnee Horses (1937), performed by the University of Texas Chamber Singers led by James Morrow

12:00: An Omaha song recorded in 1895

16:05: Art historian Adam Harris on George Catlin’s controversial paintings of Indian life

19:25: Lisa Cheryl Thomas on Arthur Farwell

20:45: Farwell’s Navajo War Dance No. 2 (1905), performed by Benjamin Pasternack

25:30: Timothy Long on the Indianists movement

29:05: Charles Wakefield Cadman’s “From the Land of the Sky Blue Waters” (1909)

30:30: Louis Ballard’s Devil’s Promenade (1973), performed by the Fort Smith Symphony conducted by John Jeter

32:15: Jerod Tate on Louis Ballard

33:40: Tate’s Crazy Horse tribute from his Victory Songs (2013), performed by Stephen Bryant and the South Dakota Symphony led by Delta David Gier

37:45: Raven Chacon’s Nilchi’ Shada’ji Nalaghali (Winds that turn on the side from Sun) (2008), performed by Emanuele Arciuli

41:00: Jeffrey Paul’s Wind on Clear Lake, performed by Lakota flutist Bryan Akipa and the South Dakota Symphony led by Gier

May 30, 2024

The “Worst Ever” Carmen — Take Two: A Way Forward

Kelli O’Hara, Renee Fleming, and Joyce DiDonato in “The Hours” [Photo: Evan Zimmerman/Met Opera]

Kelli O’Hara, Renee Fleming, and Joyce DiDonato in “The Hours” [Photo: Evan Zimmerman/Met Opera]In response to my two-day-old blog about the Met’s “worst ever” Carmen, a prominent European artists’ manager wrote (in an email): “If you would have been forced – as I was from professional duty – to attend productions as Tosca at the Aix-en-Provence Festival (staged Christoph Honoré) or Les Troyens at the Bayerische Staatsoper (staged by the same Christoph Honore) or Aida, again at the Bayerische Staatsoper (staged by Damiano Michieletto), you would understand that opera as we knew it, and as we used to love it, is a dead artistic form. It was poisoned little by little by stage directors who did not like opera and used it for their own purposes. We just have to acknowledge this fact and keep going.”

The conductor Paul Polivnick wrote (on facebook): “We don’t take the Mona Lisa and put her in a psychiatrist’s office so she can have her enigmatic smile analyzed.” Another conductor wrote (via email): “Both this article and your recent articles on [Klaus] Makela brought out what is so wrong in today’s opera and music world. . . . I have spent decades conducting in Germany and experienced the gamut from wonderful stagings in the [Walter] Felsenstein tradition to the most horrible Regietheater in which the stagings are total perversion and distortions.” (The sentiment of helplessness – from conductors — seems notable to me.)

Conrad L. Osborne, whose opera blog is mandatory reading, most recently observes: “Of all the productions I have written about over the seven years of this series, to say nothing of (I scour the memory bank in vain) those of several earlier decades, this [Carmen] has come the closest to complete separation of eye and ear: its stage world cannot conceivably have generated this music, and Bizet’s music cannot have evoked this stage world. And it is unrelievedly ugly to look at. With Carmen, the Met has hit what we must hope is rock bottom.”

What next? Do we really need to haplessly “acknowledge . . . and keep going”? What am I to make of the many thousands of readers I have suddenly and uncharacteristically acquired via my recent blogs about the startling resignation of Esa-Pekka Salonen in San Francisco, and the implausible appointment of Klaus Makela in Chicago, and the troubles afflicting the Boston Symphony? Rubber-necking? Or might there be a groundswell of discontent out of which something constructive could emerge?

Here’s an analogy to the degeneration of Regietheater that cripples opera today:

Europe experienced a couple of seismic upheavals during the first half of the twentieth century. The “sweetness and light” of the arts, especially the Germanic arts, seemed discredited. For this and other reasons, a drastic reorientation seemed required. In music, Arnold Schoenberg came up with a new method of composition – with 12-tone rows – that he believed would rescue German music from obsolescence. I know a thing or two about 12-tone composition, having studied it religiously at Swarthmore under a true believer: Claudio Spies. And I became a true believer, too. No longer. It was a wrong turn. And the wrongest turn came in the US, where the historic conditions that produced serial music did not exist. I could name a few 12-tone compositions that deserve to endure – Berg’s Violin Concerto is certainly one, Schoenberg’s Ode to Napoleon (which I have frequently presented in concert to overwhelming effect) is another. But I cannot think of a single American 12-tone piece of lasting consequence. (Can you?)

And so it is with Regietheater. It was a European product. It never made sense to import it lock, stock, and barrel to the New World. And it remains less embedded in the US – and potentially more possible to ameliorate.

What direction to take? First of all, it seems to me: stagings of opera, whatever else they may be, should be musically literate. I mean: stage directors of opera should be able to read music. They should be able to offer guidance to singers – how to inflect a word or phrase. Just as theater directors do. And ideally they should also work in concert with the conductor at hand. Currently, these conditions seem to me infrequently met at the Met.

When I think back to the 1977 Bayreuth productions I have so often described, one manifest aspect is that Götz Friedrich and Harry Kupfer were stage directors profoundly conversant with the operas – Tannhäuser and The Flying Dutchman – at hand. As for Patrice Chereau’s Ring – he shifted the musical and dramatic aesthetic toward modernism. The stage pictures of Richard Peduzzi and the conducting of Pierre Boulez followed suit – the result was an integrated whole. When Chereau’s Siegfried was indisposed, he acted the role himself (with a singer offstage). He had absorbed and memorized every detail, every gesture.

Commensurately: the director of an opera should make a close study of the work at hand. Self-evidently, this cannot be assumed. With its high tech projections and mobile metallic slabs, the Robert Lepage Ring, at the Met, furnished a notorious example. Reviewing Lepage’s Siegfried for the Times Literary Supplement in 2019, I reported:

“Lepage’s virtual-reality special effects include running water, floating leaves, slimy worms, scampering rodents, and a Forest Bird that sits in Siegfried’s lap. The production works best where it is least intrusive: act one. In act two, the shallow playing space vitiates the expansiveness of Wagner’s forest; the dragon, if impressively large and animated, is neither frightening nor poignant. In act three, the magic fire frames Siegfried’s entire scene with Brȕnnhilde. Wagner asks that it disappear after Siegfried penetrates the flames for a reason: the mountaintop he attains trembles with a preternatural stillness, a preamble to apocalyptic events. This is but one example of Lepage’s failure to listen. Directing his singers in this final scene — the most psychologically complex duet in all opera — he is clueless. [That is: Siegfried and Brunnhilde simply stand and sing.]”

No less than the Lepage Ring, Carrie Cracknell’s Met Carmen fails every criterion at hand. She not only cancels Bizet’s score. Her “feminist” take – with Carmen a victim of sexist societal norms – is a banal misreading. What’s Carmen about? Here again is Conrad L. Osborne:

“Dramatically, it introduces an agonizing twist on the [generic operatic] narrative: the couple’s bond holds the seed of its own destruction, and tragedy ensues not when one or both partners die in the struggle against antagonist forces, but when one partner kills the other. Musically, it brings an unprecedented depth and darkness to a tone that is predominantly one of brilliant, crowd-pleasing entertainment, and once past the dashed expectations of its first audience, has found no contradiction there. And there is one more layer. While the history of opera is studded with works derived from mythical sources and which take place either in a mythical world or else one wherein mythical figures and disputes govern and/or intrude into the “real” one (opera began that way, after all), there are only a few wherein a central character assumes a legendary status that itself verges on the mythical, and wherein mythical law, subliminally but quite clearly, guides the ‘real world’ action.”

A crucial detail, derived from the Prosper Merimee novella Bizet adapted: Don Jose is himself a renegade outsider. In fact, he’s killed a man and is well capable of doing so again. The mythic tragedy that Jose and Carmen enact, and which Bizet adapts, cannot be reduced to a lesson in victimization without shrinking the characters and miniaturizing their story.

***

What is the tone of today’s Metropolitan Opera? I fear that it’s summarized by the success of Kevin Puts’s The Hours. The new Met audience, insofar as it can be glimpsed, seems enraptured by this operatic adaptation of the Michael Cunningham novel and its cinematic sequel (with Nicole Kidman as Virginia Woolf).

In Understanding Toscanini (1987), I wrote: “In his landmark 1960 essay ‘Masscult and Midcult,’ Dwight Macdonald, stigmatizing both, wrote of midcult that it has ‘the essential qualities of masscult [but] decently covers them with a cultural figleaf,’ and that it ‘pretends to respect the standards of high culture while in fact it waters them down and vulgarizes them.’ . . . Midcult’s ambiguity, Macdonald argued, makes it the most insidious cultural stratum: ostensibly raising mass culture, it corrupts – packages and petrifies – high culture. It ‘threatens to absorb both its parents. It may become stabilized as the norm of our culture.’ . . To ponder the health of contemporary operatic and symphonic culture is to ponder the diverse ramifications of a vast, democratized audience headquartered here in the United States.”

To suggest that The Hours exemplifies midcult may sound gratuitous. It may sound supercilious. This is not a makeshift effort, like Terrence Blanchard’s Champion and The Fire Shut Up in My Bones. It is an opera skilled and clever in many ways. Greg Pierce’s libretto is ingenious. The vocal writing sings, and so does the orchestra. But aspirations outstrip means. Puts’s idiom is fundamentally saccharine. It craves fulfillment in cliché. Does a sung enactment of a three-woman drama pondering Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway have to end with a vocal trio remembering Der Rosenkavalier?

Invoking Virginia Woolf is false. However unwittingly, it’s opportunistic. The art of Virginia Woolf is nothing like the artifice of Kevin Puts. Read Mrs. Dalloway. Its pronounced musicality – the lyric free verse of its language – is original. The narrative, though seamlessly bound, bristles with unlikely insights into character and behavior. And Woolf is heedlessly, ruthlessly unsentimental. She abhors cliché.

Is mine an extreme reading of a popular new work? Am I ricocheting off the wall? I recognize my own response in the reviews of Alex Ross in The New Yorker and Oussama Zahr in the New York Times. Self-evidently, they both tried hard to like The Hours more than they could. So did I.

Is The Hours what we want today’s Met to be? Could it be something else? Among the peak frustrations of recent seasons was a new Lohengrin directed by Francois Girard: another dark, dystopic re-imagining of an opera flooded with air and light. It was nevertheless possible to enjoy Piotr Beczala, in the title role, as an “in spite of” accomplishment. Wagner’s poetic ending — the reappearance of the swan – proved magically indestructible; the audience came to life. Thomas Mann somewhere describes Lohengrin as “blue” – a memorable evocation. Black it is not.

Thirty years ago, I encountered a Lohengrin in Seattle directed by Stephen Wadsworth. Ben Heppner sang Lohengrin. The swan, for once, was wholly life-like. Its reappearance at the close consummated a moment purely Wagnerian. To paraphrase my viral Tannhäuser blog: as with the cataclysmic climax of the Venusberg orgy in the Met’s Schenk/Schneider-Siemssen Tannhäuser (its sudden transformation to a green valley and piping Shepherd Boy), a credulous rendering, abetted by Wagner’s musical imagination, proved as breathtaking today as in times past.

Lohengrin (Ben Heppner) and the swan [photo: Chris Bennion]

Lohengrin (Ben Heppner) and the swan [photo: Chris Bennion]It was Speight Jenkins, the Seattle Opera’s general manager from 1983 to 2014, who engaged Wadsworth and (I have no doubt) requested a credible swan. But Jenkins’ real find was the Swiss director Francois Rochaix. Rochaix’s Seattle Ring of the Nibelung, lucidly designed by Robert Israel, was the most memorable of my experience. He also staged Parsifal and Die Meistersinger in Seattle. His version of Regietheater was musical, assiduous, and original, scrupulous and creative in equal measure.

Jenkins went his own way. An impassioned, informed Wagnerite, he built on the Seattle Wagner festivals of his predecessor, Glynn Ross. He made the Seattle Opera the Wagner capital of the Western hemisphere. Beholden to no one, defying fashion, he set parameters. He refused to denigrate the operas with imputations of anti-Semitism or sexism. He shrunk the house and enhanced its acoustics. He was omnipresent in the lobbies, in the community. In Wagner Nights: An American History (1994), I summarized: “Rochaix’s response [to Wagner] is not esoteric but fresh, not complex but sincere. And the same can be said for the Seattle Wagner enterprise as a whole. Jenkins has aimed for a balanced Wagner ensemble. He has not courted celebrity performers, pedigreed by Deutsche Grammophon, Salzburg, and Columbia Artists Management. Rather, he has stressed world-class Ring lectures, four-hour Ring symposia, and a serious bookstore. His English supertitles, an innovation so far shunned by the Met, transformed the ambience of the house. . . . Something special has been rekindled: a company whose mission transcends self-promulgation.”

It can be done.

EXTRA CREDIT: Two memories of Francois Rochaix’s Seattle Wagner productions:

— The Rochaix “Ring” showed how a bold exercise in Regietheater can at the same time remain keenly attuned to Wagner’s synthesis of the arts. I write in “The Post-Classical Predicament” (1995 — reprising a long article “On Staging Wagner’s ‘Ring’” in “Opus” Magazine, April 1987):

To underline Siegfried’s coming of age, Rochaix inserts a touching pantomime . . . just after Siegfried penetrates the Magic Fire: he envisions his father’s murder, his mother’s death in childbirth, Fafner’s warning, and the Forest Bird’s summons. Fortified by new self-knowledge, he tentatively kisses Brunnhilde. Rochaix’s handling of this long final scene is so honest that for once Siegfried’s astonished exclamation ‘Das is kein Mann!’ is astonishing, not comic. Disregarding Wagner, Rochaix has Siegfried flee his awakened bride; when Brunnhilde sings ‘Wer ist der Held, der mich erweckt?’ [‘Who is the hero who has awakened me?’], he stands, terrified, well outside her field of vision. Brunnhilde’s gradual transformation from goddess to woman, Siegfried’s coming to terms with adult feelings, their growing proximity, mutual awareness, and commitment — Rochaix’s detailed understanding of all of this, his use of blocking and gestural detail to bind the momentous, compressed emotional scenario, is a triumph of creative empathy.

Many at Seattle found Siegfried’s interpolated pantomime/vision intrusive. The problem is partly Wagner’s; his layoff partway through act 2 of Siegfried created discontinuities in the Ring. In particular, Siegfried and Brunnhilde became somewhat different personalities. Rochaix’s masque intelligently attempts to explain the new Siegfried, whom Brunnhilde eventually praises for his loyalty and valor.

—For more than a decade I regularly reviewed music books and New York operatic performances for the Times Literary Supplement (UK). This was before the internet – to my knowledge, these articles have not been digitized. Here’s my review, from August 2003, of Francois Rochaix’s Seattle Opera “Parsifal” production:

For most of the twentieth century, opera in the United States was synonymous with the New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Nowhere else was anything like a fulltime opera season sustained for decades without interruption. Only in Chicago and San Francisco was a local tradition of opera-giving substantially implanted. But beginning in the 1960s regional companies began to grow dramatically in number, size, and achievement. In 1987 the Met abandoned its annual national tour. Concurrently, English-language supertitles everywhere won converts to opera as theater. Today, America’s leading regional opera companies have acquired unprecedented individuality and sophistication – and nowhere more than in Seattle, which now boasts North America’s leading Wagner house.

The Seattle Opera began presenting summer cycles of the Ring of the Nibelung in 1975 under Glynn Ross, an entrepreneurial visionary who started from scratch. Ross’s successor as of 1983, Speight Jenkins, is also a zealous Wagnerite (he closes the office for Wagner’s birthday). Jenkins opted for a more ambitious Ring, one he could not afford to mount every summer, but more carefully cast, more strongly conducted, and more provocatively staged. The resulting 1986 cycle, directed by Francois Rochaix and designed by Robert Israel, was a landmark event. If the influence of Patrice Chéreau’s 1976 Bayreuth centenary Ring was discernible, in most respects Rochaix (best-known in his native Switzerland) and Israel (then keenly associated with Philip Glass’s Satyagraha) went their own way. Such signature images as the airborne carousel horses ridden by the Valkyries achieved an iconic intensity.

Meanwhile, back in New York, the Met entrusted its Ring and three other Wagner operas to Gunther Schneider-Siemssen and Otto Schenk. The goal was something like the naturalism Wagner himself prescribed, abetted by modern stage technology. The outcome fulfilled Wieland Wagner’s prediction that “a naturalistic set today would simply destroy an illusion, not create one.” Seeking authenticity, Schenk assumed that sin and redemption were concepts whose self-sufficient meanings could shock and inspire as Victorian audiences were shocked and inspired when the Ring and Parsifal were new.

Jenkins mounted fresh Seattle productions of The Flying Dutchman, Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, Die Meistersinger, and Tristan between 1984 and 1998. He also, in 2001, unveiled a new, hyper-realistic Ring conceived by Stephen Wadsworth – a production [which I reviewed for the TLS] both more beautiful than the Met’s and more meddlesome in its psychological portraiture. This summer, Seattle finally completed its traversal of the Wagner canon with a work never before given locally: Parsifal. As the production was assigned to Rochaix and Israel, and happened to coincide with the opening of a new home for the company, expectations ran high: as at Bayreuth in 1882, Wagner’s Bühnenweihfestspiel inaugurated the hall.

The former Seattle Opera House, a product of the 1962 World’s Fair, was merely functional. The Marion Oliver McCaw Hall, on the same site, is in every way an improvement. From stage and pit, the sound is more vivid than before. The voices project easily. The excellent orchestra – mainly members of the Seattle Symphony — has acquired new tonal richness and depth. Visually, the new building seems as airy and spacious as the old one felt ponderous and square. Though the seating capacity has been only slightly reduced – from 3,017 to 2,900 — the gain in intimacy is notable. The central downstairs seating space is narrower, flanked by more sharply raked seats themselves flanked by – the most arresting touch – “floating” boxes rising in a diagonal along the side walls.

“Parsifal” in Seattle (2003), designed by Robert Israel (photo: Chris Bennion)

“Parsifal” in Seattle (2003), designed by Robert Israel (photo: Chris Bennion)The new Parsifal is a more qualified triumph. Jenkins wanted a production that did not underline the work’s decadence or loudly infer racism. He wished to afford his first-time Parsifal audience a positive experience of Wagner’s confusing final opus. At the same time, in engaging Rochaix, he was certain not to obtain a whitewash.

Rochaix dispenses with obvious effects and cheap thrills: the cup does not glow red; the spear is not caught in mid-air. A non-sectarian universality is stressed. The costumes are as often Eastern as Western. The flower maidens include an American flapper and an Arabian Scheherazade. What most stays in the mind’s eye, and teases the brain, is the treatment of the grail knights: a motley assemblage of robed Middle Eastern types, including some whose trance-like gestures and gyrations connote a religious fundamentalism much in the news today. These tableaus are executed with exceptional conviction and attention to detail. They achieve an authentic strangeness – and also insure that we are not to equate holiness with wholesomeness.

Israel’s sets are typically spare. The transformation scenes are chiefly achieved by moving a gigantic slab of stage into a vertical position. Klingsor’s wooden tower occupies the full height of the stage; its “destruction” entails a startling 47-foot descent into the bowels of the theater. A striking inspiration is the macabre coffin/crib in which Titurel sits erect, a severe presence counterposed with his wayward son. In place of scenery, the production mainly opts for color-saturated images produced and manipulated by digital projectors from a behind a screen forming the back of the set. To begin act two, before the prelude in the pit, the ruddy mountain range of act one is digitally rotated to reveal the parched landscape – the mountain’s other side — of Klingsor’s realm. The projectors offer a verdant Classical version of the magic garden – which blurs when Parsifal strives fruitlessly to remember “what I have forgotten” and cannot. Destroyed, the garden digitally decomposes.

A special strength of Rochaix’s Ring was his penchant for adding eloquent witnesses to the action – Wotan, vigilant in a side-stage chair, unforgettably followed the actions of his harried and beloved offspring during Die Walküre act one. Rochaix similarly situates Kundry in a peripheral space, where her act one presence is prolonged beyond the exit specified by Wagner. Amfortas appears, ghost-like, while Kundry administers her seductive act two kiss. When Parsifal returns to Monsalvat in act three, the squires, richly differentiated, gather excitedly to follow the benedictions bestowed by Gurnemanz and Kundry. Far from constraining the singers, these additions, subtly choreographed, create fresh opportunities for characterization while inviting empathy on stage and off.

Of the principal singers, Stephen Milling achieves greatness as Gurnemanz. Like Germany’s René Pape, this young Danish bass, whose Seattle Fasolt and Hunding two summers ago (his American debut) announced the arrival of a major singing actor, has everything: voice, presence, intellect. Not yet 40, he has mastered the long act one narratives: every word, every gesture tells. He credibly impersonates an old man in act three. During the Good Friday music, his large, full-featured face is as expressive an instrument as his huge voice. He next sings Gurnemanz at the Vienna Staatsoper in 2005.

The Parsifal of Britain’s Christopher Ventris is also a major achievement, magnificently acted and strongly sung. Greer Grimsley, the Amfortas (and a Seattle mainstay), was indisposed on August 16; his cover, Gary Simpson, was in every way impressive. Willa Cather, in an indelible 1916 commentary, called Kundry “a summary of the history of womankind,” and continued: “[Wagner] sees in her an instrument of temptation, of salvation, and of service; but always an instrument, a thing driven and employed. . . . She cannot possibly be at peace with herself.” Describing the Kundry of Olive Fremstad, the Met’s principal Wagner soprano from 1903 to 1914 and the Callas of her day, Cather wrote that she “preserves the integrity of the character through all its changes. In the last act, when Kundry washes Parsifal’s feet and dries them with her hair, she is the same driven creature, dragging her long past behind her, an instrument made for purposes eternally contradictory. . . . Who can say what memories of Klingsor’s garden are left on the renunciatory hands that wash Parsifal’s feet?” The tragic entrapment of this extraordinary Wagner creation eludes Linda Watson in the Seattle production. Having sung the role in Bayreuth, New York, and Berlin, she is a singer conscientious, sincere, and skilled. But she lacks the demonic. Rochaix does not help by replacing Kundry’s expiration at the opera’s close with an ecstatic tableau in which she lifts the sacred spear alongside Parsifal and the uplifted grail. Both Kundry and her fate are made to seem the more conventional.

Seattle’s conductor is an Israeli, Asher Fisch, who has led Parsifal in Vienna, Dresden, and Berlin. His authority is evident. Not the least satisfactory aspect of Wagner in Seattle is the audience. Jenkins provides a full menu of pre-performance lectures and post-performance discussions, two symposia, and a CD companion. His audience trusts him, and also Wagner. Once past the prelude, there is no coughing. When people applaud, they mean it.

Another manifestation of loyalty is the new hall itself: of its $127 million cost, more than $70 million comes from non-governmental sources. At a time when other American opera companies are reeling from the recession – Chicago Lyric, Los Angeles, and San Francisco have all cancelled major productions – Jenkins has balanced his budget 12 years in a row, a feat the more remarkable given the collapse of the local economy, with its dependence on .com companies and a Boeing plant greatly diminished in scope and personnel. The summer’s nine Parsifal performances were 85 per cent sold out. The paucity of non-North American visitors – about 1 per cent — was notable.

Wagnerites from outside the United States and Canada should know that the Wadsworth Ring will be repeated in summer 2005 under Robert Spano. Other Seattle Wagner productions will be reprised in the summers of 2004, 2006, and 2008.

Two postscripts complete this American Parsifal report. This past spring, for the first time since 1974, someone other than James Levine led Parsifal at the Met. The someone was Valery Gergiev, and he breathed new life into a tired and tedious production. Gergiev is always heard to best advantage in New York with his own Kirov company. On this occasion, something like the dark ceremonial majesty of a Kirov Boris or Khovantschina was frequently suggested. Also new to the Met Parsifal were René Pape’s Gurnemanz and Falk Struckmann’s Amfortas – unsurpassed characterizations.

Also: thanks to andante.com, the complete Wagner recordings made by Leopold Stokowski for RCA between 1921 and 1940 are now readily available in a 5-CD box (AND1130). These performances document the Philadelphia Orchestra in its peak estate (of which Rachmaninoff said: “Philadelphia has the finest orchestra I have ever heard at any time or any place in my whole life. I don’t know that I would be exaggerating if I said that it is the finest orchestra the world has ever heard”). And they document the most anomalous of all the great Wagner conductors: a New World original, the ultimate sonic sybarite. Stokowski’s 40 minutes of Parsifal excerpts constitute the most beautiful Parsifal performance on records – even, I would say, the most beautifully sung (though there are no human voices). As surely as Karl Muck at Bayreuth keyed on the drama’s ascetic hero, Stokowski singularly inhabits Klingsor and his magic garden.

May 28, 2024

The Met’s “Worst Ever” Carmen and What To Do About It

“Les tringles des sistres tintaient” –Clémentine Margaine as Carmen in act two of Bizet’s “Carmen.” (The truck tires rotate.) Photo: Nina Wurtzel / Met Opera

“Les tringles des sistres tintaient” –Clémentine Margaine as Carmen in act two of Bizet’s “Carmen.” (The truck tires rotate.) Photo: Nina Wurtzel / Met OperaTwo veteran opera-goers of my acquaintance reacted identically to the Metropolitan Opera’s new production of Georges Bizet’s Carmen. One called it “the worst thing I’ve seen at the Met in thirty years.” The other declared it the “nadir” of the company’s 141-year history. I had to go.

A classic description of this opera, by Friedrich Nietzsche, extols it as the apex of “Mediterranean” genius, refuting the dark miasma of Germanic art. Nietzsche called it a “return to nature, health, cheerfulness, youth, virtue!” Its music “liberates the spirit.” It “gives wings to thought.” Bizet’s exoticized Spain is sublimely lucid, streaming with sunlight, hot with perfumed indolence.

Carrie Cracknell’s Met Carmen inflicts black skies, barbed wire, and machine guns. The act one workplace is a guarded facility all of whose female employees wear pink uniforms. The soldiers outside are joined by vagrants (who however sing as if soldiers). The act two gypsy song is danced (sort of) within the confines of the cargo hold of a moving tractor trailer truck. Later in the same act, Carmen’s solo dance of seduction is positioned atop a gasoline pump, a perch so precarious she needs a helping hand from Jose (whom she is defying). The act three set (Bizet’s “wild spot in the mountains”) is the trailer truck overturned, rotating circularly on its side. Dirt and grime are omnipresent.

According to the program book, Cracknell has transplanted Carmen to “a contemporary American industrial town.” Bizet’s Seville cigarette factory is now an “arms factory.” The outcome is a “contemporary American setting” where “the issues at stake seem powerfully relevant.” Carmen and her co-workers are oppressed in a man’s world.

In short, this is a revisionist reading reconstruing plot and characters. And yet Carmen is an opera, not a play. Whatever one makes of the logic of Cracknell’s strategy, it negates the poetry of the music at every turn.

Regietheater, now ubiquitous on world opera stages, was largely born in Germany after World War II – and no wonder. Heilige Kunst seemed, if not discredited, clouded with questions the loudest of which afflicted the operas of Richard Wagner. My own first exposure came at the Bayreuth festival of 1977 – about which I have written extensively (having been sent by the New York Times). Encountering Gotz Friedrich’s Tannhäuser (new in 1972), Patrice Chereau’s Ring of the Nibelung (new in 1976), and Harry Kupfer’s The Flying Dutchman (of which I reviewed the premiere), I encountered a consistency of highly rehearsed operatic acting, wedded to a thoroughness of directorial engagement, wholly new to me. Friedrich’s Tannhäuser was an anti-fascist polemic. Chereau’s method was to assume nothing. He found himself fascinated by the guile of Mime and Alberich, and disgusted by Wotan’s more complex opportunism; he gave him grasping gestures and a scowling face; he dressed him as Wagner.

Kupfer, too, knew what he was doing. I was stunned by his conceit that the main action of the opera was hallucinated by the deranged Senta. I found her character fortified — and also that of Erik, who understood his beloved all too well. The trade-off was a shallower Dutchman, reduced to an idealized figment of imagination. But what most lingered was Kupfer’s ingenious delineation of twin stage-worlds coincident with twin sound-worlds. As I previously wrote in this space: “Kupfer’s handing of musical content was an astounding coup. The opera’s riper, more chromatic stretches were linked to the vigorously depicted fantasy world of Senta’s mind; the squarer, more diatonic parts were framed by the dull walls of Daland’s house, which collapsed outward whenever Senta lost touch. In the big Senta-Dutchman duet, where Wagner’s stylistic lapses are particularly obvious, Kupfer achieved the same effect by alternating between Senta’s fantasy of the Dutchman and the stolid real-life suitor (not in Wagner’s libretto) that her father provided. Never before had I encountered an operatic staging in which the director’s musical literacy was as apparent or pertinent.”

It was only a matter of time before something similar happened at the Met. The breakthrough moment came in 1979 with a re-imagining of The Flying Dutchman by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle. But the breakthrough was careless and superficial. By staging the opera as if dreamt not by the high-strung, headstrong Senta, but by the ancillary Steersman, Ponnelle gained nothing. And the dreamscape itself resembled a high school auditorium at Halloween.

One may ask – one should ask – what purposes may be served transporting historically conditioned Germanic Regietheater to the US. I can think of two. The first, as at Bayreuth, is an exercise in taking a known opera and casting a different light upon it. But nowadays the majority of American operagoers are newcomers, or relatively so: this rationale is cancelled. The second is to discover new “relevance.” But, consulting my long and checkered operatic memory, I cannot think of a single production that by resituating time and place likely enhanced the engagement of audiences new to the work.

Earlier this season, the Met revived the most literal, least revised Wagner staging in memory: the Otto Schenk/Gunther Schneider Siemssen Tannhäuser of 1972. I wrote a series of four blogs opened by thousands of readers. The first read in part:

“Many points of conjunction between what the ear hears and the eye sees are unforgettably clinched. The action begins with the erotic Venusberg. Wagner asks for ‘a wide grotto which, as it curves towards the right in the background, seems to be prolonged till the eye loses it in the distance. From an opening in the rocks, through which the daylight filters dimly, a greenish waterfall plunges down the whole height of the grotto, foaming wildly over the rocks; out of the basin that receives the water a brook flows to the further background; it there forms into a lake, in which Naiads are seen bathing, while Sirens recline on its banks.’ Schneider-Siemssen wisely doesn’t attempt all of this – but he poetically renders enough of it to get the job done. At the climax of the Venusberg orgy, Wagner makes everything suddenly and cataclysmically vanish, to be replaced by ‘a green valley. . . blue sky, bright sun. In the foreground is a shrine to the Virgin. A Shepherd Boy is blowing his pipe and singing.’ A credulous rendering of this transformation, abetted by Wagner’s musical imagination, proves as breathtaking today as half a century ago.

“At the opera’s close, Tannhäuser expires alongside Elisabeth’s bier, and young pilgrims arrive with a flowered staff betokening his foregiveness. Nowadays, this ending is variously revised. It is considered toxic or tired. But faithfully conjoined with the reprise of the Pilgrims’ Chorus, it remains overwhelming. . . .

“The arts are today vanishing from the American experience. There is a crisis in cultural memory. How best keep Tannhäuser alive? Flooded with neophytes, the Metropolitan Opera audience is very different from audiences just a few decades ago. What I observed at the end of Tannhäuser was an ambushed audience thrilled and surprised. The Met is cultivating newcomers with new operas that aren’t very good. A more momentous longterm strategy, it seems to me, would be to present great operas staged in a manner that reinforces – rather than challenges or critiques or refreshes – the intended marriage of words and music. For newcomers to Wagner, an updated Tannhäuser would almost certainly possess less ‘relevance’ than Schenk’s 46-year-old staging – if relevance is to be measured in terms of sheer visceral impact.”

In short: there are lessons to be learned from the new Carmen. But it would take a brave artistic initiative, flaunting fashion, to apply them.

All this I pondered while enduring acts one and two last Wednesday night. After that, I discovered that Diego Matheuz’s gestures of hand and baton, in the pit, were more eloquent than anything to be seen onstage. In fact, the musical highlight of the performance was Matheuz’s shaping of Micaela’s aria, and the poetic virtuosity of the accompanying French horns. I am certain I would have enjoyed the Micaela and Don Jose – Ailyn Perez and Michael Fabiano – under other circumstances.

The Metropolitan Opera’s 2023-24 Carmen deserves to be remembered, and answered, as a seminal lesson in waste – and this at a time when the American arts are starving.

May 23, 2024

Why Colorado Mahlerfest Matters

Ken Woods plies his guitar at “Electric Liederland” [Photo: Mark Bobb]

Ken Woods plies his guitar at “Electric Liederland” [Photo: Mark Bobb]The most profound music ever conceived by Richard Strauss may be Metamorphosen for 23 solo strings. Composed in 1945 when Strauss was 81 years old, it memorializes the cultural inheritance symbolized by the opera houses of Munich, Dresden, and Vienna, all bombed to rubble during what Strauss called “the most terrible period in human history . . . the 12-year reign of bestiality, ignorance, and anti-culture under the greatest animals.” He also wrote: “I am beside myself. . . . There can be no consolation.”

At the thirty-seventh annual Colorado Mahlerfest in Boulder last week, Kenneth Woods prefaced Metamorphosen with Wagner’s overture to Die Meistersinger – a sublime embodiment of what those opera houses were about. The impact of this juxtaposition was devastating — not least because we ourselves increasingly inhabit a time of “ignorance and anti-culture”.

At 55, Woods is the rare conductor with an exceptional curatorial gift. He has been Mahlerfest music director since 2015. His regular job is conducting the English Symphony Orchestra in Worcester (UK). He lives in Carduff, where his wife plays in the BBC National Orchestra of Wales. Born and trained in the US, he has never been offered an American podium of consequence.

The 2024 Mahlerfest packed seven concerts and an all-day symposium into five days. As Woods also plays electric guitar and sings, one evening, “Electric Liederland” in a Boulder rock/folk venue, included edgy riffs on Mahler’s Ninth and Das Lied von der Erde. Another included on its second half “Visions of Childhood,” a sui generis suite for chamber ensemble and soprano conceived by Woods and previously presented in concerts and a recording by the English Symphony Orchestra. It comprised:

–The opening measures of Mahler’s Fourth (arr. Woods)

–Wagner’s Siegfried Idyll (arr. Woods)

–Two songs from Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel (arr. Woods)

–Schubert’s “The Trout,” alternating the song with the variations for piano quintet (arr. Woods)

–Mahler’s “Das irdische Leben” (arr. Woods)

–Schubert’s variations on “Death and the Maiden” (arr. Woods)

–Mahler’s “Das himmlische Leben” (arr. Woods)

The cumulative impact was magical.

The festival’s big pieces (on separate symphonic programs) were Strauss’s Alpine Symphony and Mahler’s Symphony No. 4. (I contributed a symposium talk on Mahler and Schubert; my Mahlerei for bass trombone and chamber ensemble, recasting the Scherzo of Mahler’s Fourth, was also performed.)

Woods’s reading of the Mahler symphony was both spacious and sharply detailed. Of his 94 players, the vast majority are Mahlerfest regulars. They come from as far away as New York and Texas, Canada and Korea. They relish this composer’s sweet portamentos and prickly dynamics. They also manifest a rare degree of pride and engagement. The excitement with which they applaud Woods, and one another, reminds me of the South Dakota Symphony – another orchestra mainly comprised of ardent out-of-towners who don’t come for the money.

Introducing the Meistersinger Overture at a pre-concert talk, Woods highlighted a salient feature of Wagner’s inexhaustible opera: its celebration of cultural community. And this, finally, is what the Colorado Mahlerfest is about. As with last year’s memorable reading of the Resurrection Symphony, the audience for Mahler’s Fourth was strikingly inter-generational, including local families for whom Mahlerfest is an annual ritual. The week also included a mountain hike, open rehearsals, and various breakfasts and dinners.

I will have something to say about my Mahlerei – magnificently realized by Woods and David Taylor – in a forthcoming post. Next year, the featured symphony will be No. 6. In 2026, the Mahlerfest topic will be “Mahler the Man” — explored via the Symphony No. 9 and a staging of the full-length play I have extrapolated from my novel The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York.

May 21, 2024

“Ripeness Is All” — Is the South Dakota Symphony’s Mahler Really Better than Klaus Makela and the Oslo Phil?

Many readers have responded to a series of recent blogs in which I’ve pondered the bewildering appointment of Klaus Makela, age 28, to become music director of the Chicago Symphony beginning in 2027. Some have expressed incredulity that I prefer Delta David Gier’s South Dakota Symphony reading of Mahler’s Third to Makela’s with his superb Oslo Philharmonic.

As it happens, South Dakota has just released a livestream video of its Mahler 3. And Makela’s sits on youtube right here. So you can make the comparison yourself.

As I wrote: to my ears, Makela’s performance of the vast finale sounds “enraptured by the ardor of youth,” whereas Gier’s sounds “enraptured by the pathos of humanity.” That is: Gier’s is the deeper, more Mahlerian reading.

Now that I have had the opportunity to revisit both performances, I find the disparity in impact even greater than I had thought. They are in fact fundamentally different.

During his years as a New York Philharmonic assistant conductor, Gier heard Leonard Bernstein rehearse Mahler’s finale. It’s marked “Langsam. Ruhevoll. Empfunden” (slow, peaceful, heartfelt). Mahler’s original title was “What Love Tells Me” – “love” here designating agape: Christian love for one’s fellow beings. Gier vividly recalls that Bernstein challenged the assistant conductors in the hall to describe the movement in a single word. They all failed. The correct answer was “pain.”

Perhaps this exchange says more about Bernstein than Mahler. And yet Mahler’s sublime finale unquestionably recalls the first movement’s catastrophic upheavals. Have a listen to Gier’s reading. From measure one, it maps an interior trajectory gradually intensified on a vast scale, an odyssey of feeling in which pain is revisited and healed. In Makela’s reading, I detect no searing pain, no inner trajectory. The smile he occasionally flashes seems to me inappropriate. And I find myself aware of the push and tug of the conductor’s baton. It is Gier’s performance that sounds organic, egoless.

At the very beginning of the movement, the South Dakota string choir conveys a stirring gravitas. Mahler instructs “molto expressivo,” “Sehr gebunden,” “Sehr ausdrucksvoll gesungen” (very expressively sung). His portatos and portamentos, dynamic swells, Luftpause – all hallmarks of Mahler style – are more vitally and fully rendered than by the Oslo players. The pianissimo cello song beginning on measure nine searingly intermingles beatitude and sorrow. That’s at 00:36. The second violins, who have been listening, confide a rapt response.

To hear the Oslo cellos and second violins, go to 1:16:19. These opening measures, led by Makela, sing a portentous song. But Mahler’s existential duress is silenced.

Some people find this Mahler movement too long. The very ending follows a triumphant cadence with another, and another, and another, and another. In Makela’s performance, this sequence sounds distended – it could end sooner or later. In Gier’s performance, Mahler’s calibrated re-emphases sound right. And the final message is not a smile, but Mahler’s own superscript: “Behold my wounds: Let not one soul be lost.”

If I am beating a dead horse, it must be beaten. Klaus Makela’s Chicago appointment coincides with his concurrent music directorship of Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw Orchestra. Gier has lived in Sioux Falls since 2005. He is a civic force, an agent of communal identity. Again: age matters. He is 62.

There is no denying that Makela’s is a great talent. As I have twice written: he seems to have been born with a baton in his crib. Orchestras adore him, and no wonder. There is also a panic to find young audiences, to brandish the imagery of youth. It is not his fault that his Mahler lacks ripeness. We should not expect him to simulate a maturity not yet his.

I ponder musical ripeness in a recent American Scholar article. Should you discover a pay-wall, I append what I wrote. My earlier American Scholar article on the South Dakota Symphony and the future of American classical music may be accessed here.

[From “Ripeness Is All,” as recently published online in The American Scholar:]

Today’s biggest controversy in classical music is the Chicago Symphony’s appointment of Klaus Makela, who will become music director in 2027-2028. He will concurrently take over Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw Orchestra – one of the half dozen most eminent European ensembles. He will be all of 32 years old.

No one can reasonably dispute Makela’s precocious talent. He seems to have been born with a baton in his crib. From a tender age, he trained with a legendary Finnish pedagogue: Jorma Panula. His subsequent professional trajectory has been meteoric.

The attendant outcry takes three forms: that, beyond conducting concerts, Makela will lack the maturity (let alone the time) to furnish institutional vision; that he will be conducting too many pieces for the first time under a glaring spotlight; that, given his youth, his interpretations will lack “ripeness.”

The third reservation is the slipperiest – and ultimately the most momentous. It’s long been conventional wisdom that symphonic conductors mature slowly – that age suits them better than, say, singers or dancers or instrumentalists, all of whom practice demanding physical skills. And many a famous conductor has been most eminent when most old. Think of Arturo Toscanini, whose reputation peaked when he was in his eighties. Or Otto Klemperer, who acquired a commanding eminence gris when he was in his seventies. But what, exactly, does musical “ripeness” connote? How is it manifest in performance? And is it imperiled by our ever accelerating world of social media and AI?

I can think of an obvious example of exigent life experience transforming the recreative act. Wilhelm Furtwängler was with Toscanini the most celebrated symphonic conductor of the twentieth century. Because Furtwängler was a performer who channeled the moment, his World War II broadcast performances, from beleaguered Berlin, attain an apocalyptic intensity. And his postwar performances, commensurately, are beleaguered by pain. His 1951 Radio Cairo broadcast of Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique Symphony does not resemble other readings – including Furtwängler’s own 1938 studio recording. The difference is the traumatic memory of war. The composer’s autobiographical heartache is transformed into a dire existential statement transcending the personal. The symphony’s most familiar melody – the first movement “love theme” – is taken so slowly that it changes meaning: it emanates a terminal Weltschmerz.

But I mainly find myself thinking of an artist I knew well, because I wrote a book about him. My Conversations with Arrau (1982) document many eventful meetings with Claudio Arrau beginning in 1978, when he was already 75 years old. Arrau had acquired an elite reputation as a concert pianist prone to tortuous introspection. Earlier in his career, he had been a dazzling virtuoso – and by all account a voluble conversationist. When I knew him, he had withdrawn from language. I observed:

“Arrau is an effortful speaker. Sometimes, before answering a question, he will draw a breath and look away. His sentences break down when a phrase or name will not come, and the ensuing silences can seem dangerous. . . . It is really not far-fetched to surmise that for Arrau words and music occupy distinct personal realms, and that the pronounced civility of the first moderates the instinctual abandon of the second. His gentle manners, his fastidious attire, the artifacts that embellish his work environment – these suggest a striving for order whose musical equivalent is his absolute fidelity to the text, and whose adversary is a substratum of fire and ice. To witness Arrau performing the Liszt sonata is to know how thoroughly this substratum can obliterate his normal self-awareness. Even while sleep, the demons cast a trembling glow from behind his mildest public face. And they penetrate the timbre of his voice. . . . Arrau listens to his own recordings with visible discomfort; he perceive the clothes of civility being stripped away.”

A humbling specimen of Arrau’s mature artistry is a 1976 recording of “Chasse neige.” This is the last of Franz Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes and, according to many, the most challenging to play. Liszt has fashioned a ruthless study in tremolo: the rapidfire alternation of notes or chords. To this he adds gigantic skips, upward and downward, in both hands. The tremolos are pedaled – a smearing effect promoting ambience. At the same time, the more notes the ear discerns, the more exciting – the more harrowing – the etude becomes.

Arrau’s virtuosity is paradoxically mated with patience. Because even in the midst of chaos he never rushes, the clarity of attack remains exceptional. And because he perfected a technical approach to the piano stressing arm and shoulder weight, his tone remains characteristically plush – not chipped, not shallow – regardless of the frantic demands placed upon his fingers. No other rendering of this music, in my experience, is as thick with incident.

But the coup de grace occurs two and a half minutes into the piece, where Liszt – having unleashed a barrage of oscillating chords pulverizing the extremes of treble and bass – writes “calmato,” “accentuato ed espressivo,” and “mezzo piano.” Here the left-hand tremolos cease, replaced by rapid chromatic scales racing upwards and down like dark breaths of wind. Under Arrau’s cushioned hands, the scales are streaked with pain. They momentarily sigh with exhaustion, and with an uncanny sadness of memory. They are the stilled human eye of an inhuman storm.

Arrau performed the music of Liszt throughout his long career. He studied with a distinguished Liszt pupil. He revered Liszt, identified with Liszt. He portrayed Liszt in a Mexican bio-pic. His earliest Liszt recordings date from the 1920s. But never before the 1960s will you hear anything like Arrau’s recording of “Chasse neige.” (Arrau himself once acknowledged to me: “Many people say I’m a ‘late developer.’”) The very keynote of this interpretation, clairvoyantly extrapolated by an artist already 73 years old, is retrospection. A famous 1840 painting of Liszt, by Josef Danhauser, situates him in a lushly appointed salon. George Sand, Alexander Dumas, Victor Hugo, Nicolo Paganini, and Giacomo Rossini are all in attendance. A large bust of Beethoven sits atop the piano. As a conjurer’s recollection of Liszt in his element, revered by his contemporaries, reverencing his great forebear, Arrau’s “Chasse neige” far trumps Danhauser’s painting. Liszt’s “snow storm” resonates and expands; it jars open a bygone world of feeling and experience both conscious and subliminal. It exudes a veritable elixir of memory.

Could any young pianist or conductor accomplish such a feat? There are ways. Van Cliburn peaked at 23 when he won the 1958 Tchaikovsky International piano Competition. Upon landing in Moscow, he had asked to be driven to the Church of St. Basil. Standing snowy Red Square late at night, he thought his heart would stop. He identified the Moscow Conservatory, where the competition was held, with his hero Rachmaninoff, who had graduated with a gold medal in 1892. When he visited Tchaikovsky’s grave in Leningrad, he took some Russian earth to replant at Rachmaninoff’s grave in New York. He called the Russians “my people” and said, “I’ve never felt so at home anywhere in my life.” Living a dream, he moved with a clairvoyant sureness, touching outstretched hands, pledging friendship between nations. Performing Rachmaninoff’s Third Piano Concerto, he built the first movement cadenza – the concerto’s central storm point, an upheaval of expanding force and sonority — with utter sureness: the tidal altitude and breath of its crest were dizzying. The leading Soviet pianists, on the competition jury, proclaimed him a genius. Cliburn’s filmed 1958 and 1960 Moscow performances of concertos by Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky, nestled on youtube, document a young artist surrendering himself completely to the moment. Never again would Cliburn attain such heights of musical expression. And the Russia he knew, insulated from the West, still re-living its musical past, no longer exists.

In 1962, the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition was begun in Forth Worth. To date, its most esteemed gold medalist was Radu Lupu – in 1966, when Lupu was 21 years old. Born in Rumania, he trained in Moscow. His earliest recordings already document an uncanny musical worldliness. As a peerless exponent of Mozart, Schubert, Schumann, and Brahms, Lupu all his life inhabited a bygone world. He shunned twentieth century music. He kept his own counsel. In fact, to the surprise and consternation of the Cliburn Foundation, he had pocketed his first prize and returned to Russia, refusing to undertake the high-profile concert tour prepared for him. Suppose that Klaus Makela had told his manager Jasper Parrott: Thank you very much, but I am not prepared to take over two of the world’s most prominent orchestras. That was Radu Lupu.

The winner of the most recent Cliburn competition is a Korean: Yunchan Lin, now twenty years old. He has catapulted into a major international career. As it happens, one of his acclaimed competition performances was of Liszt’s “Chasse-neige.” You can see and hear it on youtube. Lin has great fingers and he has heart. His rendition is riveting — never glib, never superficial. But it would be vain to look for anything like the scope of Claudio Arrau’s reading. Arrau’s Liszt echoes and re-echoes through corridors of time, a performance for the ages. For that matter: Wilhelm Furtwängler’s Cairo Radio recording of Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique Symphony revealingly juxtaposes with Klaus Makela’s intensely entertaining Pathetique – I heard him conduct it with the New York Philharmonic in December 2022. The third movement march, in particular, memorably ignited. But it would be vain to look for anything like the pain and tragedy of Furtwängler’s reading.

Will Makela and Lim attain ripeness? Consider: Franz Liszt was born in 1811, Claudio Arrau in 1903 – nine decades later. During the intervening century, many things changed. Nevertheless, Arrau was born (in Chillán, Chile) to a world without telephones, without airplanes or cars or radios. Later, he stayed put in Berlin, immersed in the cultural efflorescence of Weimar Germany. He later recalled: “I’m sure that the twenties in Berlin was one of the great blossomings of culture in history. The city offered so much in every field, and everything had a greater importance than in other places. . . . You see, there was a great misery. Many people were starving. There were no jobs. Such times are always fertile. Everything was so difficult that people sought a better life in culture.”

And what if Arrau had been born, like Klaus Makela, in 1996? That’s 94 years after 1903 – about the same time-gap that separated Arrau from Liszt. And yet the century of change ending in 2000 documents an upheaval unprecedented and ongoing – what the German sociologist Hartmut Rosa calls “social acceleration.” Writing in 2013 (Social Acceleration: A New Theory of Modernity), Rosa lists three “fundamental dimensions” of this phenomenon: technological, social, and “pace of life.” He predicts an “unbridled onward rush into an abyss,” possibly including nuclear or climatic catastrophes. He also predicts – accurately – “the diffusion at a furious pace of new diseases” and “new forms of political collapse.” Rosa does not highlight the arts. But socially accelerating atoms of human experience today undermine all previous understandings that art is necessarily appropriative; chaotically askew, they support the illusion that, locked in our disparate identities, we cannot know or speak for one another. What is more, a privatized, atomized lifestyle promotes neither arts patronage nor production. Rather, its diversion mode is the soundbite: particulate cultural matter; stranded arts particles.

A month ago my own quest for anchorage inspired me to re-read Buddenbrooks (1901). How can one absorb that Thomas Mann was in his mid-twenties when he wrote this novel about a mercantile family history in northern Germany? It’s populated with men and women of all ages, from infancy to late infirmity. How could someone so young absorb so much experience? The only possible answer is that Buddenbrooks was written a very long time before social media and cell phones. No sooner did I share my bewilderment with colleagues and friends than I heard back from a prominent scholar who teaches at an eminent university. He had just shared Tristan und Isolde with his freshmen and encountered blank stares in response.

Currently, I’m working on a documentary film based on my book The Propaganda of Freedom: JFK, Shostakovich, Stravinsky, and the Cultural Cold War. So I am making my way through a nine-part Netflix series: “Turning Point: The Bomb and the Cold War.” The archival footage is gripping. Otherwise, this film is an exercise in instant gratification catering to short attention spans. Though an army of scholars has been assembled, the barrage of thirty-second soundbites from a multiplicity of sources pre-empts differing viewpoints. The story at hand becomes a centrist fable, implying a consensus of opinion where none exists: no questions, just answers. And the ubiquity of musical cliche – the soundtrack, which never stops to listen or reflect — turns it all into melodrama: Hiroshima, Nagasaki, the Cuban missile crisis, the Berlin Wall – and Kharkov right now.

Commensurately, cultural memory – for untold centuries, a precondition for creativity and appreciation of the creative act – risks becoming a stack of flashcards processed as media clips. Will sustained immersion in lineage and tradition remain an organic prerequisite for composition, interpretation, and reception?

Gloucester, in King Lear, counsels: “Ripeness is all.” Never has Shakespeare’s observation more resounded as an admonition.

May 12, 2024

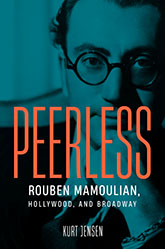

A New Biography Ponders the Controversial Director of “Porgy and Bess”

My Wall Street Journal review of Kurt Jensen’s new Rouben Mamoulian biography takes stock of a unique near-genius, perhaps the least known and appreciated American theater and film director of consequence.