Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 10

September 5, 2023

“The Jazz Threat” on NPR

In my book Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music, I call “an antipathy to jazz” one of the defining attributes of American classical music during the interwar decades. I’ve also written a lot about “the jazz threat.” In the US, jazz bore a Black taint; it was linked to brothels and nightclubs; it was declasse. Henry Ford’s notorious Dearborn Independent denounced jazz as a “morally filthy” alliance of crude African-Americans and clever Jewish “merchandizers.” European-born composers more greatly esteemed jazz than their American colleagues.

All of this is the topic of my most recent “More than Music” NPR documentary [click to open]. I explore the jazz affinities of Maurice Ravel, Igor Stravinsky, and Paul Hindemith. Moving on to today, I cite the Swiss-born composer Daniel Schnyder, who achieves a bristling jazz/classical fusion without shortcuts. And I sample the jazz-infused performances of Schnyder on saxophone, pipa virtuoso Min Xiao-fen, and bass trombonist David Taylor.

Eventually, I ask Michael Dease if the jazz threat persists. An award-winning trombonist, Dease is white-passing though his mother is Black – so he finds himself eavesdropping on conversations bearing on music and race. His short answer is: yes – jazz remains more prestigious abroad. To hear his long answer, go to 39:00.

Wrapping up, I observe that a lot of what’s being composed today sounds “makeshift” to my ears – a panoply of mixed musical genres and styles unsupported by a panoply of knowledge. “Especially in the US, the jazz threat we’ve been talking about compartmentalized music – classical versus popular, high versus low. Today’s music, by comparison, eagerly squeezes the ‘big [musical] sponge’ Daniel Schnyder extols. The challenge is to squeeze the sponge in a really informed and considered way. The composers we’ve sampled all furnish lessons in doing precisely that. “

A nation’s music anchors its identity. That America’s music is formidably Black creates tensions that continue to stress the national fabric.

(Most of the performances here were recorded at last summer’s Brevard Music Festival, supported by a “Music Unwound” grant from the NEH. The next Brevard NEH Music Unwound festival, next July, will be the first of four celebrating the sesquicentenary of Charles Ives.

A LISTENING GUIDE:

PART ONE:

00:00 — Hindemith’s Symphonic Metamorphosis, with its jazz fugue

6:10 — Berlin’s Comedian Harmonists sing Cole Porter

8:45 — Woody Herman’s Bijou, an influence on . . .

10:30 — Stravinsky’s Ebony Concerto

PART TWO

12:00 — A sublime “Blues” by Ravel

15:40 — Josephine Baker in Paris

16:50 — Paris as a refuge for Black American musicians

18:45 — Aaron Copland and Roy Harris on the limitations of jazz

21:00 — Ravel and Gershwin

25:00 — Ravel’s jazzy piano concerto in G

PART THREE

30:15 — A fabulous Duo for saxophone and bass trombone by Daniel Schnyder

34:00 — David Taylor plays Schubert on his bass trombone

37:00 — Min Xiao-fen plays Thelonious Monk on her pipa

39:00 — Michael Dease on why jazz remains more prestigious abroad

47:00 — Schnyder’s bass trombone concerto — an exemplary “musical sponge”

August 22, 2023

Pedro Carboné (1960-2023)

The pianist Pedro Carboné – who was one of my closest friends – died last night of a stroke in Alicante, Spain, where he resided. He was a peerless exponent of the formidable piano works of Isaac Albeniz and Manuel de Falla. He was only sixty-three years old.

Pedro was born in Zaragoza. His first important teacher was Pilar Bayona – in the world of Spanish piano, a consequential name. He recorded the complete Chopin Etudes at a tender age. He later retooled his technique guided by Jean-Bernard Pommier, whom he credited with helping him achieve a deeper, more penetrating tone.

Fullness of texture was a Carboné hallmark — crucial in the dense chordal masses and insanely entangled sonorities charting the summit of the Spanish keyboard literature: Albeniz’s 90-minute Iberia, which Pedro expunged of sentimentality and perfume. In Spanish repertoire (not including Granados, for which he did not care), he insisted on a degree of austerity. There was nothing Gallic about his Andalusian style; it projected an immense and stubborn dignity. Compared to the influential Iberias of Alicia de Larrocha, compared to the touristic Iberia orchestrations of Enrique Arbos, Pedro projected a darker, more dissonant Spain.

Pedro enjoyed talking at his concerts – and, once begun, found it hard to stop. Most memorably, he called Falla’s keyboard concerto (which he performed on the piano, not the alternative harpsichord) “an encapsulation of the history of Spanish music” – and this otherwise inscrutable composition became iconic. The first movement dissects a popular song from medieval Spain. The second is a stark religious epiphany – the Spain of the Escorial. The third pays homage to the eighteenth-century harpsichord school of Scarlatti and Soler. The entire exercise partakes of twentieth century modernism. (Pedro explained that Falla skips the nineteenth century – the century of zarzuela – because he disdained it.)

The Fantasia Betica for solo piano – Falla’s final flamenco appropriation – is another keyboard masterpiece in search of Spain. Pedro here treated flamenco with the same extraordinary gravitas that Falla attained. In the third movement of Falla’s Nights in the Gardens of Spain Pedro discovered “the birth of Spanish music.” If you want to know why, you can hear Pedro play and explain everything here — https://www.wwfm.org/webcasts/2018-12...

More recently, Pedro was intent on resurrecting the music of Oscar Espla, an original twentieth century voice sidelined by the reactionary aesthetics of Franco’s regime.

Pedro was a frequent house-guest in our Manhattan apartment. He was an object of intense affection for my wife and children. He also knew our Golden doodle, Teddy, from puppydom. He was an exemplary eater and refrigerator-raider. And he was my most frequent piano-duet partner. On countless occasions we plunged through the symphonies of Mozart and Beethoven. The biggest racket we ever made came in the first-movement development of Beethoven’s Eighth, whose convulsive energies perfectly suit the keyboard. In the manic intensities of certain Schubert marches, and the same composer’s Divertissement a la hongroise, we discerned a tongue-in-cheek hilarity. We memorably discovered that the knitted textures of Schubert’s C major Symphony can generate a wholly satisfying four-hand concert work. Pedro’s authority in Bach – in four-hand transcriptions of the great organ works, in Victor Babin’s beautiful two-piano versions of the trio sonatas – was utterly natural; he flawlessly projected polyphonic textures I could only skim. With compatible partners, the piano duet becomes a rare medium for spontaneous intimacy.

Pedro was closely bonded to his mother (who survives him) and to his two sisters and their families. I greatly regret that I had no occasion to meet Lina, the loving companion of his last years. His abiding love for his dog Tobi was both touching and telling.

August 15, 2023

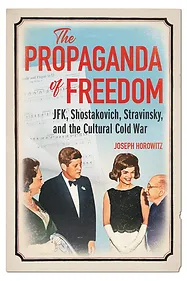

The Cultural Cold War — at a 30 % Discount

My brand-new website posts information on my brand-new book: The Propaganda of Freedom: JFK, Shostakovich, Stravinsky, and the Cultural Cold War.

The pub date is September 26. You can order it now at a 30 per cent discount.

Here’s a description:

Eloquently extolled by President John F. Kennedy, the idea that only “free artists” in free societies can produce great art became a bedrock of America’s cultural Cold War. But this dogma defied centuries of historical evidence — to say nothing of achievements within the Soviet Union.

Joseph Horowitz writes: “That so many fine minds could have cheapened freedom by over-praising it, turning it into a reductionist propaganda mantra, is one measure of the intellectual cost of the Cold War.”

In a post-pandemic Afterword, Horowitz assesses the Kennedy Administration’s arts advocacy initiatives and their pertinence to today’s fraught American national identity. He writes: “We are witnessing an erosion of the arts far beyond the arts challenge that worried President Kennedy. . . . The mistrust of federal arts subsidies I today encounter – even within the arts community itself — is partly a residue, however unnoticed, of the propaganda of freedom.”

Horowitz shows how the efforts of the CIA-funded Congress for Cultural Freedom were distorted by an anti-totalitarian “psychology of exile” traceable to its secretary general, the displaced Russian aristocrat/composer Nicolas Nabokov, and to Nabokov’s hero Igor Stravinsky.

In counterpoint, he investigates personal, social, and political factors that actually shape the creative act. He here focuses on Stravinsky, who in Los Angeles experienced a “freedom not to matter,” and Dmitri Shostakovich, who was both victim and beneficiary of Soviet cultural policies. He also takes a fresh look at cultural exchange and explores paradoxical similarities and differences framing the popularization of classical music in the Soviet Union and the United States.

In closing, Horowitz calls for “greatly increased government support [of the arts] at every level” and writes: “That the Kennedy White House failed to recognize the place of the arts in Soviet Russia says something not just about the Cold War, but about the United States, then and now. . . The United States won the Cold War. The cultural Cold War did not yield a victor.”

Challenging long-entrenched myths, The Propaganda of Freedom newly explores the tangled relationship between the ideology of freedom and ideals of cultural achievement.

ADVANCE PRAISE:

The Propaganda of Freedom is a wholly absorbing indictment of the CIA’s Congress of Cultural Freedom as supremely misconceived — something of a mirror image, in fact, of post-war Stalinist Russia. In that sense they deserved each other.

–John Beyrle, former US Ambassador to Russia (2008-2012)

Joseph Horowitz’s thesis that an ideology of “freedom” made it impossible for leading American intellectuals to recognize the cultural achievements of Soviet artists during the Cold War is compelling and convincing — even for readers unversed in the cultural or musical history of the twentieth century. In fact, all too often American foreign policy is based on the false premise that promoting “individual freedom” must remain at the heart of the nation’s efforts to exert influence abroad.

The Propaganda of Freedom raises important questions not only about the efficacy of US foreign policy, but also about the relationship between culture and democracy, even about the nature of democracy itself — questions extremely pertinent in a world where populist political movements have called into question democratic norms that once seemed unassailable.

Above all, it is the author’s extrapolation of a “fetishization of freedom’’ that makes this work so vital. Horowitz writes: “That so many fine minds could have cheapened freedom by over-praising it, turning it into a reductionist propaganda mantra, is one measure of the intellectual cost of the Cold War.” His book serves as a warning that the American tendency towards political and cultural unilateralism is not only naïve, but dangerous.

–David Woolner, Resident Historian, the Roosevelt Institute; author of The Last One Hundred Days: FDR at War and at Peace

This exceptional revisionist study, by one of the leading cultural historians and public intellectuals of the last four decades, completely upends our understanding of the cultural Cold War and of JFK’s role as a national arts advocate.

–Richard Aldous, author of Schlesinger: The Imperial Historian

Joseph Horowitz’s fascinating study presents fresh perspectives on old arguments – including JFK’s idea that culture only exists where freedom exists. It also serves as a warning as we precipitate a new and dangerous Cold War.

-Elizabeth Wilson, author of Shostakovich: A Life Remembered

The Propaganda of Freedom dramatically changes our understanding of a fascinating chapter in twentieth century cultural history.

– Vladimir Feltsman

August 3, 2023

Schubert Lieder on the Trombone (continued)

The 20-minute Mahler/Schubert song cycle Einsamkeit, which I have concocted with the bass trombonist David Taylor, maps a dire trajectory. Each song begins with a disappointed lover. Each discloses an ever more extreme state of “Einsamkeit” – of an existential solitude grown strange and inscrutable.

The ineffability of late Schubert was brought home to me by an email from William Sharp, one of America’s premiere vocal recitalists, in response to my earlier Einsamkeit blog. Bill writes of “Der Leiermann,” the final song of Schubert’s cycle Winterreise (and also of Einsamkeit):

“I have never understood why anyone calls the protagonist of Winterreise a ‘madman’! Where does that impression come from? Winterreise is a traumatic 24-hour journey of loss and self-imposed isolation precipitated by the loss of a loved potential spouse through social/class strictures. It ends with the voluntary end of withdrawal into depression. The poet approaches the poor musician (artists are poor — that’s why they can’t be married) and suggests a healing artistic collaboration. The artist no longer wishes to die, and will save himself with his art. The Müller boy [in Die schone Mullerin] hasn’t got this life-saving thing in his life, and commits suicide.”

This compelling reading is not that of – for instance — Richard Capell, in his indispensable 1928 study of Schubert songs. Capell writes of this “last turning of the wintry road”: “A madman meets a beggar, links with him his fortune, and the two disappear into the snowy landscape . . . We may read anything or nothing much into the cleared scene.”

Johann Michael Vogl, the most eminent contemporary exponent of Schubert’s songs, wrote after Schubert died that his compositions were products “not of conscious action” but “of providence,” that they occupy “a state of clairvoyance or somnambulism.” The pianist Claudio Arrau applied to late Schubert the term “Todesnähe” – a proximity to death.

Einsamkeit begins with Mahler’s “Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht” – a jilted lover’s lament. Schubert’s “Die Stadt” and “Der Doppelganger,” coming next, are disturbed utterances – but the dank city, and harrowing “double” on the street below, are images we can glean. “Die Nebensonnen,” with its three suns in the cold sky, and “Der Leiermann,” with its strange hurdy-gurdy man, are images less readily interpretable. Different readers, different singers, will render them differently.

David Taylor and I first performed Einsamkeit with dancers, two months ago. Igal Perry unforgettably inhabited the Leiermann in a white suit (you can see a video here). A few weeks ago, David and I performed Einsamkeit sans dancers at the Brevard Music Festival (the video at the top of this column). David’s bass trombone, with its various mutes and techniques of utterance, is a marvel of instrumental virtuosity. Mainly, however, his rendering of the five songs is a tour de force of expressive musical speech.

What we have done to Mahler and Schubert (my accompaniments are far from literal) will be differently processed by different listeners. At Brevard, there were musicians in the audience who felt we had newly excavated (not distorted) what Mahler and Schubert were saying.

Further thoughts: working on “Die Stadt,” with its gray water and “dreary rhythm,” I suddenly realized its kinship to very late Liszt – to his Venetian piano cameos La lugubre gondola I and II. And also, by extension, to Busoni’s ghostly, rocking Berceuse. (All these works, Schubert’s included, visit the outskirts of tonality.) I had a look at Liszt’s influential piano versions of Schubert’s songs – and discovered that, in scoring the cycle Schwanangesang, he places “Die Stadt” first. And he transcribes it with a fiendish relish: a tremendous achievement, in its way. But Liszt’s pianistic flourishes diminish the strangeness Schubert’s inspiration. Late Schubert also turns uncanny in his Drei Klavierstucke, D. 946 – which will never rival in popularity the two sets of Impromptus. If “Die Stadt” forecasts late Liszt, here the intermingling of quotidian and sublime is virtually Mahlerian.

When you watch and listen to the Brevard Einsamkeit, be sure to use headphones – or many details (including David’s singing of “Die Nebensonnen”) will be inaudible. My thanks to Brevard’s Matt Queen for filming/editing. The Brevard performance included the supertitles below:

Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht (00:00)

When my sweetheart has her wedding day

It will be my day of sorrow

I’ll weep, weep for my darling.

Die Stadt (4:12)

On the distant horizon

The town appears as a misty shape.

A dank breeze ruffles

The grey water in dreary rhythm.

The boatman rows my boat.

The sun rears up and shows me

The place where I lost my love.

Der Doppelgänger (The Double) (7:47)

The night is still. The streets are quiet.

Here is the house where my sweetheart lived.

A man stands there, wringing his hands.

Horror grips me as I see his face

And the moon shows me my own self!

Die Nebensonnen (11:32)

I saw three suns in the bright cold sky

And watched them long with steadfast eye. . . .

Now the best two are gone.

And if the third would only go

That all were dark ‘twere better so.

Der Leiermann (14:40)

Beyond the village stands the organ-grinder

Playing as best he can with numb fingers.

He staggers barefoot in the snow.

No one stops to listen or to look.

Strange old man, shall I go with you?

Will you join in my songs?

July 23, 2023

“Closer to Mahler and his wife Alma than any other author I have read”

The most recent review of my new novel, The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York, is by Clive Paget in Musical America(July 18). Paget writes:

“With his unparalleled knowledge of fin-de-siècle classical music in America, Joseph Horowitz has brought us closer to Mahler and his wife Alma than any other author I have read. . . . At times, your heart breaks for them both. . . . In Gustav and Alma Mahler, Horowitz has created two of classical music’s most convincing fictional portraits.”

Paget also finds that my “realization” of Alma Mahler “makes her a far more complex and sympathetic figure than the usual trophy hunter on the lookout for the next husband.” This is now a governing motif of the book’s reception – and illuminating for me because (as I’ve previously written in this space) I made no conscious effort to rehabilitate Alma. Rather, I endeavored to experience events as she herself did. It is a novelist’s task – and demonstrates (as I argue in the book’s Preface) that historical fiction can be an indispensable tool for the cultural historian.

I must add that Paget’s flattering comparison of my portraiture of turn-of-the-century New York society to the “vibrant brushstrokes of John Singer Sargent” captures precisely the intent of the “deliciously opulent” prose style I have consciously attempted.

The full review is appended.

By Clive Paget, Musical America

LONDON — How to fathom the unknowable? Gustav Mahler is one of history’s most complex and contradictory personalities, a man disarmingly naïve, intellectually profound, blunt to the point of rudeness, dictatorial, preoccupied—and frequently all at the same time. Literary biographers struggle to pin him down, swayed by all sorts of predispositions. With his unparalleled knowledge of fin-de-siècle classical music in America, Joseph Horowitz could easily have joined them, writing a U.S.-centric polemic on Mahler’s four-year career as a conductor in New York. Instead, he’s written his first novel, and in the process brought us closer to Mahler and his wife Alma than any other author I have read.

The Marriage traces Mahler’s annual American sojourns, from his heralded first arrival in December 1907 to take up the conducting reins at the Metropolitan Opera, to his final departure in April 1911, a broken man in the full knowledge that he was going home to die. Imagined through the eyes of the composer himself, his emotionally conflicted wife, and other historical figures, the author offers a glimpse into the Machiavellian goings on of the wealthy socialites and artistic personalities who saw Mahler as a means to their own ends.

Horowitz does have an agenda. He’s not unreasonably concerned that all previous writings on the composer—including the fourth volume of Henri Le Grange’s magisterial biography—have been way too Eurocentric. As such, he has issues he wants to address, laid out here in a preface and substantial afterword. Mahler was entirely unsuited to America, he opines. Far from it being the case that his fatal illness cut short a promising middle-period career as a conductor, the Austrian composer’s controversial artistic choices and unbending personality made him as many enemies in the U.S. as he’d left behind in Vienna.

Not a happy time

On the one hand, he was compromised by a typically European snobbishness that left him unable to appreciate the high level of performances that American audiences had enjoyed for decades under his short-lived predecessor—and golden boy of Bayreuth—Anton Seidl. On the other, his typically unbending way with the press, and in particular his handling of the doyen of critics Henry Krehbiel, at The New York Tribune, merely hastened his downfall. Ultimately, his time at the helm of the newly constituted New York Philharmonic was a dismal failure.

It’s a credit to Horowitz that he resists riding these hobby horses in the novel (or if he does, it’s always aimed at deepening our understanding of the personalities involved). Drawing on firsthand newspaper accounts, Gustav and Alma’s letters, and his own awareness of the seething, Byzantine American music milieu into which Mr. and Mrs. Mahler found themselves precipitated, he conjures a vivid portrait of New York society and life in the teeming city at the turn of the century. An assured portraitist, he brings his cast to life with the vibrant brushstrokes of a John Singer Sargent.

Mahler emerges here as a reasonably astute operator, but much given to introspection, the result of the death of his elder daughter in 1907. At first, he’s optimistic he might discover a New World audience for his own music free from the twin biases of old-world Antisemitism and artistic conservatism. Alas, he’s no match for the society ladies—and ultimately the shackles of their artistic committee—while failing to appreciate the pool of local talent successfully tapped into by his noted compatriot Anton Dvorák. When he discovers his wife’s infidelity with young architect Walter Gropius, his reaction is blinkered and hopelessly innocent.

Even more compelling is Horowitz’s realization of Alma. History has not been kind to Alma Schindler Mahler Gropius Werfel, 20 years her husband’s junior, but Horowitz makes her a far more complex and sympathetic figure than the usual trophy hunter on the lookout for the next husband. To do this he’s simply taken her letters at face value—not a bad place to start—and what

emerges is a woman desperate to find herself but tragically shackled to the least likely man to help her do so. At times, your heart breaks for them both.

Their New York world

Horowitz surrounds them with a supporting cast of fully three-dimensional characters. There’s society doctor Joseph Fraenkel whose physical examinations of Alma invariably “took the form of a surrogate exercise in mutual sensual arousal”; there’s the pert, functional, and determined Mary Sheldon who brings Mahler to the Philharmonic and bit by bit ties his hands; and there’s Krehbiel, a brilliant polyglot yet ponderous pedant, who considers himself snubbed by Mahler and, like the worst kind of critics, lives on memories of cozy relationships with Seidl and Dvorák.

Along the way you learn about various people who pass through Mahler’s orbit,

from the chronically unwell Met Opera impresario Heinrich Conreid to the sexually ambiguous Wagnerian soprano Olive Fremstad. There’s a lovely cameo for Feruccio Busoni, an ethereal cloaked figure flitting from Mahler’s sickbed and gliding out the door. Throughout, Horowitz’s stylish prose is interrogating, illuminating, and often deliciously opulent.

Historical novel and musical treatise, The Marriage is for anybody who enjoys a good read, but especially for people wanting to know more about who Mahler really was. I may not always believe every single word he writes, but in Gustav and Alma Mahler, Horowitz has created two of classical music’s most convincing fictional portraits.

July 13, 2023

How to Ignite a Standing Ovation for a Stravinsky Symphony; or: When is it OK to Project Moving Images During a Concert?

Readers of this blog, and listeners to my NPR shows, will recall that a South Dakota performance of Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony last February unforgettably galvanized a Sioux Falls audience. A major factor was a 40-minute preamble, with live music, exploring the symphony’s relationship to the Siege of Leningrad and the depredations of Joseph Stalin. I came away from that experience convinced that this is a work that should never be performed in the US without some form of contextualization.

I had a second such experience at the Brevard Music Festival last week: a performance of Stravinsky’s Symphony in Three Movements that ignited a standing ovation. If you know this piece, you will understand that standing ovations are not a likely consequence of any performance. There were two main reasons: a 20-minute preamble including a jazz band, and an accompanying film.

The story of the Symphony in Three Movements – which I have told before in this space – is so tangled that sharing it with an audience can either result in profound ennui or keen engagement. It includes the Woody Herman Band, a bad Hollywood film about a French peasant girl susceptible to religious visions, and newsreel images the relevance of which Stravinsky both confirmed and denied.

It all amounts to a remarkable study of the creative act – one which wholly disproves Stravinsky’s notorious insistence that he found inspiration only in his brain, never from outside resources. That this work was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic as a World War II “Victory symphony” was in fact a gift to the composer during a fallow period – years of diminished inspiration Aaron Copland, for one, blamed on a condition of rootlessness: a “psychology of exile.”

The basic text here is a confession to Robert Craft, long after the symphony’s premiere, that the third movement linked to “a concrete impression of the war, almost always cinematographic in origin.” Stephen Walsh, in his 2008 Stravinsky biography, dismisses the pertinence of this unlikely testimony.. That Walsh is plainly wrong is demonstrated by a “visual presentation” created years ago (for the Pacific Symphony) by my gifted colleague Peter Bogdanoff, deploying the newsreel imagery Stravinsky specified. His finale in fact plays very credibly as a kind of film score.

Whether that justifies showing Peter’s film is a question that was vigorously debated at Brevard during a post-concert discussion. In general, I think projecting moving images during a symphonic concert is a terrible idea. I oppose showing planets for Holst’s The Planets, showing an Appalachian spring for Copland’s Appalachian Spring, showing the siege of Leningrad for Shostakovich’s Seventh. All that is kitsch. It confines the listening experience.

As someone who has produced thematic concerts for over half a century, I have only twice deviated from this conviction: for the finale of Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements, and for the Largo and Scherzo of Dvorak’s New World Symphony. These are both revelatory exercises in discovering what was in the composer’s head. Why is there a triangle in Dvorak’s Scherzo? Because Pau-Puk Keewis, in Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha, had bells on his moccasins. Why all those string tremlolos in the Largo? Because the day Minnehaha died it was bitter cold and Hiawatha, in the forest, was trembling. (Peter’s “visual presentation” for the Largo and Scherzo, used by dozens of orchestras, may be seen here. By the way, his visuals are ingeniously keyed to follow the conductor, not the other way around.)

I will find myself producing half a dozen Ives festivals for the 2024 Sesquicentenary – and anticipate working with Peter on visuals for Ives’s astonishing tribute to Colonel Robert Gould Shaw’s Black Civil War Regiment: “The St. Gaudens at Boston Commons.” Here is iconic American music that means nothing without contextualization – as I have discovered, eg, at Carnegie Hall performances led by James Levine and Christoph on Dohnanyi. (That American orchestras should awaken to this reality is the topic of my upcoming 6,000-word rant in The American Scholar.)

I should add that the Brevard concert – to be repeated in two seasons by the inimitable South Dakota Symphony — was supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities. So will be all those Ives festivals, beginning at Brevard in July 2024. How I wish our orchestras would reinvent themselves as humanities institutions. Museums are already there.

If you want to know more, I append the script for the second half of the Brevard concert, which was hosted and conducted by Kazem Abdullah.

I also append, in full, Stravinsky’s scenario for the finale of the Symphony in Three Movements.

I’ll have more to say about all of this in a subsequent blog about the Brevard festival, and an NPR More than Music show coming up in September.

Here is the script (accompanied throughout by visuals):

LIVE MUSIC : Bijou, as recorded by Woody Herman

That was Bijou – a “rumba a la jazz” recorded by the Woody Herman band in 1945. Known as the “Thundering Herd,” the Herman band so impressed Igor Stravinsky in LA that he composed a piece for it – the Ebony Concerto we’re about to hear.

Born in Russia in 1882, Stravinsky was first exposed to American popular music in Paris before World War I. Some years after that, when the Swiss conductor Ernest Ansermet toured the US with the Ballet russe, he brought back memories of “incredible” jazz music – and also sheet music, presumably Dixieland numbers, which he shared with Stravinsky.

Stravinsky composed a “Ragtime” of his own in 1918. Later in his long odyssey, landing in Hollywood following years in Switzerland and France, he heard recordings of the Herman band – including “Bijou” – the Cuban-influenced piece we just heard.

And so Stravinsky’s Ebony Concerto was dedicated to Woody Herman and premiered by his band in 1946. The result is a compressed, seven-minute “concerto” in three movements – of which the second, as in Ravel’s Violin Sonata [heard on part one], is a “Blues.”

As it turns out, what Stravinsky admired in Herman’s swing band was not the virtuosity of the individual players, or the tunes they sang. Rather, Stravinsky is entranced by the band’s discipline, its rhythmic zest, its array of instrumental color. As with Berlin’s Neue Sachlichkeit and France’s neo-classicism [discussed in part one], it’s “cool” jazz that matters here, not the hot variety.

Think of the Ebony Concerto as Igor Stravinsky’s personal distillation of the thundering Woody Herman sound. Our clarinet soloist is David Oh.

LIVE MUSIC: Igor Stravinsky: Ebony Concerto

While composing his Ebony Concerto, Stravinsky concurrently worked on a Symphony in Three Movements – probably the best-known piece he composed during his thirty years in Los Angeles. The strange story of this piece is a study in cultural exchange between the Old World and the New.

For instance: the second of the three movements in Stravinsky’s symphony began as music for a 1943 Hollywood film: The Song of Bernadette, starring Jennifer Jones as a nineteenth century French peasant girl susceptible to miraculous visions. Stravinsky hoped to write the soundtrack – only to be replaced by Alfred Newman. But in the second movement of his symphony he inserted music he had composed for a scene in which the Virgin Mary materializes. With its meandering flute and slithery harp, this music remains spooky.

MUSIC: mvmt 2 excerpt

The story of the Symphony in Three Movements grows stranger still. It was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic in 1945 as a World War II “Victory Symphony,” celebrating the impending triumph over Germany and Japan.

This was an opportunity Stravinsky could not turn down. But he did not use the word “Victory” in the title because he had long insisted that music could mean nothing but itself. This led to complications when the Philharmonic requested a program note. Stravinsky replied:

“It is well known that no program is to be sought in my musical output. . . . Sorry if this is disappointing but no story to be told, no narration and what I would say would only make yawn the majority of your public.” (Letter projected on screen.]

Eventually, Stravinsky asked the Philharmonic to publish a program note by the composer Ingolf Dahl. Dahl’s note, duly printed in the Philharmonic program book, was certain to “make yawn the majority.” A specimen: “The thematic germs of this first movement are of ultimate condensation. They consist of the interval of the minor third (with its inversion, the major sixth) and an ascending scale fragment.” [Program note projected on screen.]

But Stravinsky did eventually oblige the Philharmonic with a brief “Word” conceding:

“During the process of creation in this our arduous time, time of despair and hope, time of continual torments — maybe all those repercussions have stamped the character of this Symphony.” [Document projected on screen]

To complete this tangled tale: decades later, Stravinsky was asked by his assistant Robert Craft, “In what ways is the Symphony in Three Movements marked by world events?” Stravinsky answered:

“Certain specific events excited my musical imagination. Each episode is linked in my mind with a concrete impression of the war, almost always cinematographic in origin. For instance, the beginning of the third movement is partly a musical reaction to newsreels I had seen of goose-stepping soldiers. The march music predominates until the fugue, the beginning of which marks the turning point when the German war machine failed at Stalingrad. The final chord is a token of my extra exuberance in the triumph of the Allies.”

Stravinsky added, inimitably: “In spite of what I have admitted, the symphony is not programmatic. Composers combine notes. That is all.”

But it’s not all. Some years ago, Joseph Horowitz, the author of tonight’s script, collaborated with Peter Bogdanoff, who created tonight’s visuals, on a “visual presentation” for the six-minute finale of the Symphony in Three Movements, culling newsreel footage faithfully following Stravinsky’s scenario. Here, for instance, are those goose-stepping soldiers.

MUSIC: March with visuals (beginning of mvmt 3)

For the performance we’re about to hear, the last of Stravinsky’s symphonic movements will be accompanied by the visual track Horowitz and Bogdanoff created.

Considered as a “war symphony,” the Symphony in Three Movements registers the “American” perspective of a self-exiled Russian in his Hollywood. As for jazz [the topic of part one of the concert]– the syncopated kick and swagger of that Woody Herman rumba, Bijou, with which we began part two of our concert – listen to Stravinsky connect to that. And check out the very beginning of Stravinsky’s symphony. It really swings.

Please join us after tonight’s concert for a post-concert discussion with me, tonight’s artists, and Joe Horowitz. And now, to close: Igor Stravinsky’s Symphony in Three Movements.

MUSIC: Symphony in Three Movements [with visuals for movement 3]

And here, in full , is what Stravinsky said about that finale in Dialogues and a Diary (1962):

The Symphony was written under the impression of world event. I will not say that it expresses my feelings about them, but only that, without participation of what I think of as my will, they excited my musical imagination. And the impressions that activated me were not general, or ideological, but specific: each episode in the symphony is linked in my imagination with a specific cinematographic impression of the war.

The finale even contains the genesis of a war plot, though I recognized it as such only after the composition was completed. The beginning of the movement is partly and in some inexplicable way a musical reaction to the newsreels and documentaries I had seen of goose-stepping soldiers. The square march beat, the brass-band instrumentation, the grotesque crescendo in the tuba, these are all related to those abhorrent pictures.

Though what I call my impressions of world events were derived almost entirely from films, the root of my indignation was a personal experience. One day, in Munich, in 1932, I saw a squad of Brown Shirts enter the street below the balcony of my room at the Bayerisches Hof and assault a group of civilians. The latter tried to defend themselves with street benches, but they were soon crushed beneath tose clumsy shields. . . . That same night . . . as we dined, a gang in swastika armbands entered the room. One of them began to talk insultingly about Jews and to aim his remarks in our direction. . . . [The photographer] Eric Schall protested, and at that they began to kick and to hit him . . . We were rescued by a timely taxi . . . . Schall was battered and bloody . . .

But to return to the plot of the movement, in spite of contrasting episodes such as the canon for bassoons, the march music is predominant until the fugue, which is the stasis and the turning point. The immobility at the beginning of this fugue is comic, I think – and so, to me, was the overturned arrogance of the Germans when their machine failed. The exposition of the fugue and the end of the Symphony are associated in my plot with the rise of the Allies, and the final, rather too commercial, D-flat sixth chord – instead of the expected C – is a token of my extra exuberance in the Allied triumph. The figure xxxxx was developed from the timpani part in the introduction to the first movement. It is somehow, inexplicably, associated in my imagination with the movements of war machines . . .

The first movement was likewise inspired by a war film, this time a documentary of scorched-earth tactics in China. . . .

In spite of what I have said, the Symphony is not programmatic. Composers combine notes. That is all.

June 26, 2023

Translating Schubert — “Clairvoyance or Somnambulism”

How reckon with late Schubert? It inhabits a timeless musical precinct unto itself.

The pianist Claudio Claudio Arrau (in my book Conversations with Arrau) applied the term “Todesnähe” – a proximity to death. After Schubert (born in 1797) contracted syphilis in 1822 or 1823, his intimacy with death ripened. In 1824 he wrote: “I feel myself to be the most unhappy and wretched creature in the world. Imagine a man whose health will never be right again, and who, in sheer despair over this, ever makes things worse and worse, instead of better.”

But there is more than that. Late in his short life (he died in 1828), Schubert’s characteristic morbidity turned uncanny. A late Schubert song like “Der Doppelganger” projects a Dostoyevskian derangement.

I long ago proposed to my friend the bass trombonist David Taylor that “Doppelganger” would suit his extreme virtuosity – which complements extreme states of feeling. He first performed “Doppelganger” at the Musikverein in Vienna. The response was fortifying.

More recently, Taylor and I have been reading Mahler songs. The result is a five-song cycle for bass trombone and piano that I call “Einsamkeit.” The songs are by Mahler and Schubert. They begin with a jilted lover. Each maps a more advanced state of existential solitude:

Mahler: Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht

Schubert: Die Stadt

Schubert: Der Doppelganger

Schubert: Die Nebensonnen

Schubert: Der Leiermann

I cajoled the Israeli-American choreographer Igal Perry to turn this 20-minute cycle (our tempos are very deliberate) into a dance piece. I have known and worked with Igal for more than a decade. I wanted him to dance the Leiermann — the final song of Schubert’s cycle Die Winterreise. And so he did – last weekend, with his Peridance Contemporary Dance Company.

Richard Capell, in his peerless Schubert’s Songs (1928), says of “Der Leiermann” (“The Hurdy-Gurdy Man”): “A madman meets a beggar, links with him his fortune, and the two disappear into the snowy landscape . . . We may read anything or nothing much into the cleared scene.” Capell also writes that it is “the last turning of the wintry road – a chance encounter to which no purpose had led, but there, and so not refused by our poet and musician.”

Counter-intuitively, Igal’s Leiermann wore a white suit. But his gaunt, angular presence registered – instantly — a distressed gravitas. His impersonation was all depth; his disjunct gestures were minimal, almost incidental.

At the end of Schubert’s song, the singer addresses the Leiermann:

Strange old man,

shall I go with you?

Will you turn your hurdy-gurdy

to my songs?

For this naked summons I had Taylor unmute his horn. Perry’s Leiermann strayed upstage and mounted a staircase to a vacant window, in which he became a silhouette.

Johann Michael Vogl, the most eminent contemporary exponent of Schubert’s songs, wrote after Schubert died that his compositions were products “not of conscious action” but “of providence,” that they occupy “a state of clairvoyance or somnambulism.”

David Taylor and I next perform “Einsamkeit” – with subtitles, sans dancers – at the Brevard (N.C.) Music Festival on July 6.

June 22, 2023

Mahler and the NY Philharmonic — and the Pertinence of his “Failure” Today

This coming Tuesday night, I will be chatting for two hours with Bill McGlaughlin and Dave Osenberg on WWFM about Mahler in New York. The show will be streamed live at www.wwfm.org from 7 to 9 pm ET.

The topic is my new novel, The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York, about which Bill has written:

“This book is a tremendous achievement. . . . For the first time in my experience, Alma Mahler emerged not as a stick figure in the margins of the story, but central. Wayward, mercurial, fascinating, devoted to her husband and yet living (and concealing) her own life. As I read I became increasingly fond of her and sympathetic in a way that was new to me. . . . Mahler is now heard around the world. And this book deepens our experience and satisfaction and love.”

We’ll be sampling interviews with musicians who played under Mahler with the New York Philharmonic (1909-1911) – and also historic Mahler recordings by Oskar Fried and Dimitri Mitropoulos.

And we’ll explore the stormy relationship between Mahler and Henry Krehbiel, the formidable “dean” of New York City’s music critics, who notoriously called Mahler’s New York tenure a “failure.” What did he mean by that? What’s its pertinence right now, when orchestras are struggling to redefine their mission and that of their “music director”?

Tune in and find out.

June 8, 2023

“A Brave Experiment” and “Profound Journey” (by a Previously Tendentious Author)

Writers discover quickly that their books – any books – have no fixed meanings. They will read differently to different readers. And their printed words never precisely convey an author’s thoughts and stories.

Processing the response to my first novel – The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York – I now further discover that fictionalized characters and events all the more elude authorial control.

My good friend Bill McGlaughlin (esteemed conductor/inimitable broadcaster) writes to me of Henry Krehbiel – alongside Gustav and Alma, one of the three main characters in my historical fiction: “Has there ever been a bigger blowhard, stuffed fat with his own self-importance?”

I wrote back: “Bill, I LIKE Krehbiel.”

Bill: “I know that!”

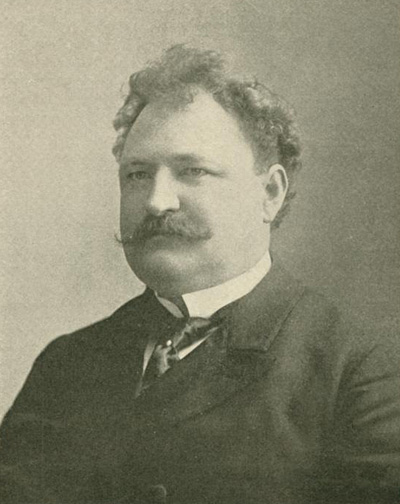

Henry Edward Krehbiel

Henry Edward KrehbielBill also writes: “For the first time in my experience, Alma Schindler/Mahler/Gropius/Werfel emerged not as a stick figure in the margins of the story, but central . . . As I read I became increasingly fond of her and sympathetic in a way that was new to me.”

Similarly: Peter Davison, in a review just posted, writes: “The most striking insights of The Marriage are about Alma.”

And yet I did not purposely undertake a newly compassionate portrait of Alma.

What I absorb from these responses (both of which begot further responses via email) is that Henry Krehbiel, in my book, stands on his own two feet, as does Alma Mahler on hers. Davison added: “Readers will respond according to their own feelings . . . because you are not steering them towards any particular judgments.”

Anyone familiar with my previous eleven books – anyone familiar with me, period — will appreciate that all my life I have been steering people towards particular judgments. And I now discover within myself novelist who does not do that. I marvel at this wholly unconscious transformation.

I share more of what Peter and Bill wrote below.

From Peter Davison’s review:

We are offered by the author a portrait of Mahler that is real. . . .

The most striking insights of The Marriage are about Alma. . . . The book lays bare the paradoxes of Mahler’s character which Alma had patiently to endure. His hypersensitivity and infantile insecurities co-existed with a tyrannical willpower which spared no one – particularly not Alma, least of all himself.

We see how Alma was at one level willingly compliant with Mahler’s demands. She needed to be needed, to be lover, mother and nurse, as well as mid-wife to the products of genius. And Alma [herself] was a bundle of contradictions, more unsure of herself in New York society than might have been expected, particularly when faced with independent-minded women . . .

In conclusion, I should draw attention to Horowitz’s use of language . . . Most impressive are his poetical accounts of Mahler’s music which profoundly acknowledge the composer’s genius, signaling that the author has no wish to diminish Mahler’s musical achievements. Descriptions of rehearsals for the Fourth Symphony in New York and the triumphant premiere of the Eighth in Munich stand out, capturing in just a few words the spirit of these great, if vastly different, works.

The Marriage is a brave experiment, following wherever the imagination leads to fill gaps in historical knowledge and to test the validity of long held assumptions.

From Bill McGlaughlin:

For the first time in my experience, Alma Schindler/Mahler/Gropius/Werfel emerged not as a stick figure in the margins of the story, but central. Wayward, mercurial, fascinating, devoted to her husband and yet living (and concealing) her own life. As I read I became increasingly fond of her and sympathetic in a way that was new to me. . . .

Going deeper and deeper, below his scholarship, Joe really imagines this lost world in a way we can enter it with him. This is his greatest achievement, I think. . . .

Along the way Joe lets us meet Mahler and his supporters and detractors, some of whom are portrayed sympathetically. Others — Henry Krehbiel, notably — are damned with their own words. (Has there ever been a bigger blowhard, stuffed fat with his own self-importance, smashing through the thickets of the music business?) . . .

To balance Krehbiel, let me cite Mahler’s insight on the real worth of Richard Strauss:

“Somewhere beneath Strauss’ insane nonchalance dwells the voice of the Earth Spirit.”

Exactly so and very generous in appraising the work of a very irritating rival. . . .

The overall trajectory of Mahler’s life in these years could leave a reader despondent. Then, just when we’re about to abandon all hope, Joe gives us the story of the premiere of the Eighth Symphony in Munich, one of the greatest triumphs of Mahler’s life. This chapter is filled with love and music and children and leaves us with the will to go on.

Joe’s Mahler & Alma is a staggering achievement, enthralling, moving and inspiring. Reading its final pages, with Busoni appearing as an Angel of Death, one has the sense of having completed a profound journey, although one that is only a prelude of what is to come in the years beyond. Mahler is now heard around the world. And this book deepens our experience and satisfaction and love.

May 26, 2023

“Einsamkeit” = Bass Trombone + Piano + Dancers

My new “Einsamkeit” concoction, setting songs by Mahler and Schubert, premieres June 17 (7:30 pm) and 18 (3 pm) at the KnJ Theater near Union Square.

I’m collaborating with the singular bass trombonist David Taylor (“Killer!” – NY Times), Igal Perry (a choreographer who really knows music), and Igal’s Peridance Contemporary Dance Company (which is celebrating its fortieth anniversary season).

The centerpiece is Taylor’s rendition of Schubert’s “Doppelganger” – a version harrowing and virtuosic in equal measure, known and feared by all bass trombonists.

The other songs we adapt are:

Mahler: Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht

Schubert: Die Stadt

Schubert: Nebensonnen (which Taylor SINGS!)

Schubert: Der Leiermann (which Igal may dance)

David Taylor and I began playing Schubert songs together in my apartment decades ago. We had earlier played through the Beethoven cello sonatas (which David sight-read). One day I was struck with the realization that Taylor could do some real damage with late Schubert. “Doppelganger” felt especially lethal. He first performed it in Vienna at the Musikverein. It worked.

“Einsamkeit” begins with solo Bach, performed by cellist Nan-Cheng Chen, choreographed by Igal Perry.

Tickets here.

(David Taylor and I next perform “Einsamkeit” (sans dancers) at the Brevard Music Festival on July 6. Taylor performs my “Mahlerei” for bass trombone and chamber ensemble at Brevard on July 5.)

[image error]

[image error]

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers