Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 13

January 17, 2023

“George Shirley: A Life in Music” on NPR

Harry Burleigh, who turned spirituals into concert songs sung by Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson, wrote in 1917 that “the voice is not nearly so important as the spirit” in performing his historic arrangements.

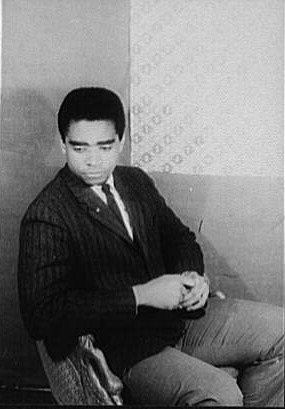

George Shirley, still singing at the age of eighty-nine, is an artist who today gloriously affirms Burleigh’s claim.

In 1961, Shirley became the first Black tenor to sing leading roles at the Metropolitan Opera. He subsequently pursued a notable international career. Today, he continues to sing in concert. It is my privilege to sometimes accompany him – and to have produced the Martin Luther King Day NPR special “George Shirley: A Life in Music.” It may be the best radio show I’ve ever created. You can hear it here.

The Shirley tenor remains strong and true. If its firmness and luster are compromised, in their place is a different kind of steadiness: to stand still and peer deep. Shirley says of Marian Anderson: “She was attuned in such a manner that the spirit sang through her.” And so it does when George Shirley sings Harry Burleigh’s “Deep River” (go to 43:00).

Of his path to the Met, Shirley says: “I never intended to be an opera singer. I was following a script written by the intelligence that created me. When doors were opened, they were opened by people on the inside.” When Shirley became the first Black member of the United States Army Chorus, its director, Samuel Loboda, took an exceptional initiative: he phoned the Pentagon while Shirley waited outside his office. When Shirley sang Romantic leads opposite the Met’s glamorous white sopranos, he accepted an invitation proferred by the company’s general manager, Rudolf Bing, who ignored resistance among his affluent board members. “I didn’t plan that,” Shirley says. “I had chosen to become a public school music teacher in Detroit. It was all in place.”

George Shirley was more than a passive instrument of change. When the Met visited Atlanta, he decided to have his hair cut and happened to choose a barber shop that had never before served Black customers – of which he became the first. When a leading New York music critic, Irving Kolodin, wrote that he “did not look like a French nobleman” singing the Chevalier Des Grieux in Puccini’s Manon Lescaut, Shirley wrote Kolodin a letter inquiring what, exactly, a French nobleman looked like.

And, crucially, doorkeepers invited Shirley inside in response to his evident gifts and character. I have no doubt that the same was true of Roland Hayes and Marian Anderson – and of Harry Burleigh. It is a lineage.

My thanks, as always, to Peter Bogdanoff, my peerless technical producer, and Rupert Allman, the producer of “1A,” who commissions and hosts my “More than Music” radio documentaries.

For links to all eight previous “More than Music” documentaries, visit www.josephhorowitz.com

LISTENING GUIDE:

5:14 — George Shirley on Roland Hayes; Roland Hayes sings Schubert

8:05 — George Shirley sings Roland Hayes’ “L’il Boy” (JH, piano)

13:25 — George Shirley on Marian Anderson

16::58 — George Shirley sings Mozart

18:50 — How George Shirley became the first Black member of the US Army Chorus

24:20 — Irving Kolodin writes that George Shirley “does not look like a French nobleman”

32:30 — George Shirley sings Harry Burleigh’s “Swing Low” (Deloise Lima, piano)

35:55 — George Shirley sings “Oh Freedom”. (Lara Downes, piano)

43:00 — George Shirley sings Burleigh’s “Deep River” (JH, piano)

December 19, 2022

Announcing My First Novel: The Mahlers in New York

My first novel, The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York, will be published in April 2023 by Blackwater Press (a young and enterprising outfit that cares about classical music). It’s already in the hands of prospective reviewers and other interested parties. It’s also announced on my website.

So far as I am aware, this is the first account of Gustav Mahler’s years with the Metropolitan Opera and New York Philharmonic (1907-1911) that does not recapitulate his own ignorance of the New World. In fact, so far as I know it’s the first book-length treatment of this topic.

I also, in a Foreword, present The Marriage as an argument for historical fiction as a vital tool for the cultural historian.

In an Afterword, I write: “Mahler was a great personality and, when circumstances permitted, a great man. He arrived in America weakened and fatigued. His energy and idealism were aroused by the New World, but fitfully . . . he remained a chronic outsider. Gustav Mahler was not really cut out to be music director of an American orchestra, sensitive to the needs of a cultural community, its scribes, audiences, and benefactors. He had bigger things to do.”

I append below five blurbs (“Advance Praise”). But first, as a teaser, here’s one of my favorite passages. It’s April 1909, and Mahler is sailing back to Austria following concerts with his New York Philharmonic:

Vita fugax. This fleeting life. My work unfinished.

And yet: How beautiful the world is! How can any clod claim indifference? How detestable is a “worldly” cynicism! Man is such a marvelous machine. When we see a complex mechanism – a motor car – do we assume that no means of propulsion is present merely because none is visible? So it is with Nature.

He was leaning on the railing, facing sky and water. The great ship was asleep. The enveloping blackness signified the hidden presence both of stars and clouds – and also no doubt of an impregnating deity. Left behind was the concrete of the city, its rackets of noise and miniature facsimiles of lake and forest. Soon he would return to the wooded seclusion of his composing hut the thought of which caused him to sink far into himself, a narcotic sensation laced with the sublime privacies of creative introspection. Lost to the world.

Gradually a half- moon appeared, its outline diffused by drifting wisps of colored air made visible by the pale yellowish light. Directly underneath, darting specks, also yellow, lit the Atlantic: Kantian ephemera, a flickering, fickle world of appearances masking the elusive profundities of existence itself.

The opening pages of the new symphony – his Ninth: dangerous epochal number – had for some time congealed in his ear: a cradle song for violins, harp, and quivering violas – a waterscape, clear or turbid, light or dark in hue, whose tolling brass and timpani intimated shoals of foreboding. A symphonic life stream whose tidal depths controlled a surface multiplicity of incident and allusion, whose deep eruptions shaped the ebb and flow of a restless Life Force in flux, in quest. An oscillation of past and future; of siren songs of memory tugging backward at head and heart; of prophecies of calamity hurtling forward toward a ruthless existential yaw.

Busoni had an inspired term for the sonic noumenal: “Ur-Musik,” underlying imposed symmetries of structure. He discovered its purest, loftiest form in the organ fantasies of Bach and in certain transitional synapses in Beethoven, in the pages of the Hammerklavier in which premonitions of the fugue materialize like atoms flying in a void, limning the elemental. Composers drawing free breath, seeking originality of form, are accused of “formlessness,” Busoni writes. Precisely. To lead music back to its absolute self. That must be the goal.

Mahler attended to the gentle bobbing motion of the Kronprinzessin Cecilie: a buoyant object atop a universe of water. He listened to the lapping of the waves upon the coursing hull beneath, to the faint hum of the engines, whose tremor he could also sense underfoot. But seeking the unknowable – ever pursuing Goethe’s unbeschreibliches – he mainly heard the unhearable: the quivering metaphysic of the dark starless night.

ADVANCE PRAISE:

Horowitz is a master of what I would call “passionate scholarship.” He has a stake in what he writes. There is a lot of very sensitive skin in his game. As a literary writer he is at heart the free-spirited scholar he has been for decades; his prose frames in precise words the psychological ambiguities of personalities no less than the nu- ances of musical compositions or performances. His deep historical knowledge blends with his narrative imagination to bring to life the sounds, the smells, the physical textures, the very air his characters breathed: Gustav and Alma Mahler are, at the same time, accurate historical portraits and haunting literary presences.

–Antonio Muñoz Molina, Winner of the Jerusalem Prize

❦

Despite his emotions having so often been on show, there has always been something enigmatic and unknowable about Gustav Mahler. But where biographers and other musicologists have struggled, Joseph Horowitz succeeds brilliantly in revealing the inner Mahler in this powerful and moving novel. It is a triumph of historical imagination.

–Richard Aldous, author of Tunes of Glory: The Life of Malcolm Sargent; Eugene Meyer Professor of History and Culture, Bard College

❦

If we want to get closer to the “truth” of Mahler and his music, if we hope to improve our understanding of the person and his crea- tions, we need to acknowledge the role our imagination must play in the learning process. In the case of Mahler, the essential facts have long been known. What we need now are fresh attempts to conceive what further truths they might contain. Joseph Horowitz’s brilliant novel reveals much to us about who Mahler was, what he accomplished, and how he related to his world. Readers will be as eager to study it as they would any biography, and they can expect to learn as much.

–Charles Youmans, Author of Mahler and Strauss: In Dialogue (2016); editor of Mahler in Context (2021); Professor of Musicology, Penn State University

❦

Joe Horowitz’s The Marriage portrays Mahler with more power and poignancy than anyone else ever has. Set in a spider web of New York City wealth, power, and intrigue, the writing is so profoundly personal, so searingly intimate, that it is sometimes painful to read – to get that close to Mahler and his wife Alma – “the most beautiful woman in Vienna.” I found myself unable to resist reading passages several times. This is a book for people who love Mahler and long to know him intimately (and there are millions) – a truer, more human Mahler than we have ever before encountered. Alma is also fabulously drawn, with all her love and antipathy towards her husband.

–JoAnn Falletta, Music Director, the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra

❦

Persuasive and fair. It is refreshing to see this chapter of Gustav Mahler’s biography from an American perspective, written by someone not automatically biased in favor of Europe.

–Karol Berger, Author of Beyond Reason: Wagner contra Nietzsche; Osgood Hooker Professor in Fine Arts, Stanford University

December 11, 2022

Klaus Makela Conducts the Philharmonic — Take Two

I am of course grateful for the torrent of comments I have received in response to my previous blog about Klaus Makela conducting Tchaikovsky with the New York Philharmonic. Some of you, however, have misconstrued my meaning. I am certainly not suggesting that Klaus Makela would be an ideal music director for the New York Philharmonic (or for that matter for the Cleveland Orchestra, where rumors are swirling).

I wrote: “The Philharmonic’s challenge is to find a leader with chops, institutional vision, and (I would insist) a passion for exploring American music.” So let’s unpack those criteria, one at a time.

1.CHOPS

My impression is that Klaus Makela is a young man born to conduct orchestras. At the age of 26, he is capable of bringing fresh energy to a well-worn symphony. If he were fifty years older than that, he would probably be capable of extracting a more tragic reading of the Pathetique Symphony. For me, the supreme recording of this work was made by Wilhelm Furtwangler and the Berlin Philharmonic in 1951, courtesy of Radio Cairo. It’s a famous performance that you can access right here. It has little in common with Makela’s thrilling rendition the other day in New York. For instance, the first movement’s “love theme” is transformed into an expression of world-weariness. The entire work becomes an exercise in tormented retrospection. As my wife Agnes remarked, hearing this performance for the first time: it’s about World War II and the aftermath of Hitler. Furtwangler uses Tchaikovsky to channel his own dire experience. You will find a related blog here.

2.INSTITUTIONAL VISION

I have no idea what institutional vision Klaus Makela may exert in his current position as music director of the Orchestre de Paris. He is also chief conductor and artistic advisor of the Oslo Philharmonic. It is apparent that he takes a lively interest in contemporary European music – an excellent sign.

3.A PASSION FOR EXPLORING AMERICAN MUSIC

Let’s just say: very unlikely. On Makela’s Philharmonic program, the opening work was Peru Negro (2012) by the Peruvian composer Jimmy Lopez Bellido. The conductor’s bio in the Philharmonic program lists Lopez Bellido as a composer Makela will also perform with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw. I enjoyed the energy and Latin tang of Peru Negro – but (as I wrote before) it’s the wrong preface for Shostakovich’s Sixth Symphony. As far as Central/South American symphonic music goes, the composer to perform is Silvestre Revueltas, a full-fledged genius with a unique sonic signature. Revueltas isn’t “contemporary”; he died in 1940. And so what? He might as well be a living composer, because our conductors and orchestras have for the most part ignored him. He’s also pertinent today as a surpassing political composer. (You can read more about him in Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music, my plea to curate the American musical past.)

OK so what are the chances of the New York Philharmonic finding a conductor who meets all three criteria? Such conductors have of course existed. Leonard Bernstein was one. Serge Koussevitzky, during his Boston Symphony tenure (1924-1949) was another. And I would call Leopold Stokowski in Philadelphia (1912-1936) a third even though his passion was for exploring all kinds of new and unfamiliar music, some of which happened to be American.

If the Philharmonic cannot locate another Bernstein, Koussevitzky, or Stokowski, the obvious move becomes: don’t appoint a music director. Do what the Berlin Philharmonic does (and also, I have noticed, the London Philharmonic ): appoint a principal conductor. The institutional vision can be supplied by someone else – maybe an executive director (like Ernest Fleischman during his long tenure with the Los Angeles Philharmonic); maybe an artistic administrator. And the expert in American repertoire might be an associate conductor or (something major orchestras need no less than museums that already have them) a scholar on staff.

A reconfiguration of this kind is hardly a new topic. In 2001 the Boston Symphony convened a “summit conference “(I was there) when it hired James Levine to be its music director on top of his consuming responsibilities at the Metropolitan Opera. The premise of that exercise was that most “music directors” were not music directors. As often as not, they have multiple jobs and mainly reside elsewhere. The same observation was mulled at the Brevard Project last summer. (As I have often remarked in this space, an exception that proves the rule is Delta David Gier, music director of the remarkable South Dakota Symphony.)

In April, my first novel will be published: The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York. It explores Gustav Mahler’s fate as conductor of the New York Philharmonic (1909-1911). Henry Krehbiel, in the New York Tribune, notoriously declared Mahler’s music directorship a “failure.” In an Afterword to my book, I comment: “Mahler was a great personality and, when circumstances permitted, a great man. He arrived in America weakened and fatigued. His energy and idealism were aroused by the New World, but fitfully . . . he remained a chronic outsider. Gustav Mahler was not really cut out to be music director of an American orchestra, sensitive to the needs of a cultural community, its scribes, audiences, and benefactors. He had bigger things to do.”

Biographers of Mahler demonize Henry Krehbiel. But Krehbiel was right. He was looking for cultural leadership of the kind personified in Boston by Henry Higginson, in New York by Anton Seidl, and in Chicago by Theodore Thomas. Higginson’s Boston Symphony, under Arthur Nikisch or Karl Muck, was equipped with a major conductor fortified by Higginson’s institutional vision and a general eagerness to explore and pursue American repertoire. Seidl, with the New York Philharmonic (1891-1898), and Thomas, with the Chicago Orchestra (1891-1905), were three-criteria leaders.

Post-Mahler, the New York Philharmonic named Josef Stransky its new conductor: an uninformed choice. After that, Arthur Judson and Clarence Mackay decided that the Philharmonic did not need a music director. So there was no Koussevitzky or Stokowski in New York. It’s a long story, told in full in my Classical Music in America. And it’s more pertinent than ever.

As for Klaus Makela – it is truly wonderful to discover a young conductor so abundantly endowed and justly recognized.

December 9, 2022

Klaus Makela Conducts the Philharmonic

I admit that I am a jaded listener, burdened by a long and presumptuous memory. I heard Mravinsky’s Leningrad Philharmonic during their sole American tour. I heard Jochum and Celibidache conduct Bruckner at Carnegie Hall. At the Met, I heard Karajan in Die Walkure, act one, with with Jon Vickets and Regine Crespin. I heard Nicolai Gedda sing Lenski’s aria. I stood through the entirety of Berlioz’s The Trojans led by Colin Davis at a Proms concert when the work was still barely known. I heard Gergiev lead his Mariinsky Orchestra in Shostakovich. I heard Arrau play Liszt. I heard Gilels plays Chopin.

These days I attend concerts and operas rarely, and with trepidation. A few weeks ago I too eagerly took my daughter to Don Carlo at the Met to introduce her to what for me is Verdi’s supreme opera. The orchestra slumbered for three hours; I did not hear a single sharp attack.

So when a friend handed me a ticket to hear Klaus Makela conduct the New York Philharmonic this morning (at 11 am!), I mainly went to encounter the new Geffen Hall. I realized Makela seems to be the hottest conductor in Europe. I did not, however, look forward to hearing a 26-year-old maestro in Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique Symphony.

But Makela’s Tchaikovsky, while not profound, proved terrific. This fellow must have been born with a baton in his crib. His style of leadership is both commanding and spontaneous. His imprint is personal. I concede that his Pathetique is (alas) more about drama than about pain; but the drama – its nuanced ferocity – carried the day. He has the confidence and authority to listen and respond in the moment to the musicians, both individually and collectively; to the vicissitudes of musical argument and expression. His is a bewildering talent.

One must ask: what are the implications for the Philharmonic? Here is an orchestra coming out of a hiatus period – a wrong-choice music director. They comprise a precision instrument. What might they further become?

The orchestra has a star in its principal clarinetst, Anthony McGill. In the Pathetique, every time McGill spoke one listened intently. His solo at the end of the first movement exposition was transporting. Here Makela dropped his stick to his side and did not conduct – and yet engineered a fabulous explosion to ignite the development. In the 5/4 waltz of the second movement, Carter Brey’s cellos took ownership of Makela’s charming inflection of the singing/skipping tune. The same tune, the same inflections were sung merely dutifully by the violins. The same violinists did too little with the first movement’s aching melodies.

I found the program poorly made: the second work on the first half, Shostakovich’s Sixth Symphony, was a non sequitur following Jimmy Lopez Bellido’s Peru Negro (and the performance lacked gravitas). The Philharmonic audience remains an obstacle: too much coughing. Even after a Pathetique that should have locked every listener in their seat, many were quick to rise, don their coats, and hurry up the aisles, backs to the players. As for the new hall, its intimacy (many fewer seats) is of course a big improvement. For the Pathetique I sat behind the stage, facing Makela. The sound was so vivid that I did not mind that the strings were over-balanced. For the first half, in a rear downstairs seat, I found the sound nothing special.

What my experience mainly said to me is that there’s a future. Conductors can still greatly matter, and such conductors are still being produced (at least in Finland). Makela is already spoken for: in 2027, he takes over Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw Orchestra. The Philharmonic’s challenge is to find a leader with chops, institutional vision, and (I would insist) a passion for exploring American music. In 1951, Leonard Bernstein premiered Charles Ives’ Second Symphony with the Philharmonic: a landmark event. But Ives remains underperformed. (The Ives Sesquicentenary is coming in 2024.) Long ago, in 1894, the Philharmonic triumphantly premiered a formidable American symphony, by George Templeton Strong, in the high Romantic mold; a revival of that hour-long work, creatively contextualized, could be momentous. In 1940, John Barbirolli and the Philharmonic introduced a seething cantata by Bernard Herrmann: Moby Dick. With a top bass-baritone as Ahab, it would be an easy sell (this being the same Bernard Herrmann who composed Psycho, Vertigo, and Citizen Kane). What about William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony, which to my ears towers above Florence Price’s over-performed, overpraised Third Symphony? What about the most formidable of all American piano concertos, by Lou Harrison? That the Philharmonic has yet to program either creates a chance to matter.

Hearing Klaus Makela conduct the New York Philharmonic excited high expectations. The challenges at hand are formidable; but so may be the opportunity.

SOME RELATED BLOGS:

On the Dawson symphony

On Lou Harrison

On American orchestral repertoire

November 28, 2022

Lou Harrison and Cultural Fusion on NPR

While the present-day conflation of the arts with instruments for social justice is dangerously overdrawn, some musical experiences are unquestionably therapeutic, and some composers are more wholesome than others.

My most recent “More than Music” NPR radio documentary celebrates “Lou Harrison and Cultural Fusion.” Of Harrison’s music, I observe:

“In today’s terms, it was ‘global’ and ‘inclusive.’ It celebrates ‘diversity.’ . . .

“One cultural influence that proved crucial for Harrison was Indonesian – the palpitating gamelan orchestras of Java — percussion ensembles which reject directional Western harmonies in favor of a kind of poetic stasis. . . .

“He was an early apostle for gay rights. He campaigned for world peace. He enfolded both East and West – without ever dabbling.

“’Globalization,’ we are told, can mean diffusion – a thinning of the cultural fabric, an unmooring from tradition. Lou Harrison – the man, the musician — was both global and anchored. The absorption of gamelan in such works as his Piano Concerto is so complete that the Harrison style, global influences notwithstanding, is all of a piece; the finished product cannot be called ‘eclectic.’ But it could be called ‘American.’ Harrison’s perennial optimism, his self-made, learn-by-doing, try-everything approach, his polyglot range of affinities are all New World traits.

“He was a composer far ahead of his time. We should aspire to catch up with him.”

The 50-minute broadcast extensively samples Harrison’s majestic Piano Concerto – the most formidable by any American, music American orchestras should please program.

A LISTENING GUIDE:

00:00 – Exploring junk percussion and Harrison’s Concerto for Violin and Percussion

12:00 – Javanese gamelan and its influence on Debussy (14:30) and Ravel (15:30)

17:40 – Balinese gamelan and its influence on Colin McPhee

21:30 – Bill Alves demonstrates the layers of Javanese gamelan

23:55 – Exploring Harrison’s Piano Concerto

35:00 – Lou Harrison the man, with Sumarsam, Bill Alves, Dennis Russell Davies, and Jody Diamond

A related blog:

The Lou Harrison Centenary

October 13, 2022

The Brevard Project: Orchestras, American Roots, and Appropriation

George Shirley’s spellbinding performance of Roland Hayes’ “Lit’l Boy,” filmed last July at the Brevard Music Festival, was a highlight of twin Brevard initiatives: a week-long “Dvorak’s Prophecy” festival inspired by my recent book Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music, and the “Brevard Project,” a think-tank/seminar pondering the fate of the American orchestra. The book, the festival, and the Project all pursue a common theme: the quest for a “usable past” in American classical music: American roots.

This was the topic Dvorak seized when in 1893 he prophesied that “Negro melodies” would foster a “great and noble school” of American classical music. The same prophecy was uttered, even more memorably, by W. E. B. Du Bois a decade later when he called the sorrow songs of Black Americans “the greatest gift of the Negro people.” And indeed the sorrow songs fostered a multitude of popular musical genres known the world over.

But they were mainly squandered by America’s concert composers — the story I tell in my book. The magnitude of this omission was dramatized at Brevard by performances, three days running, by George Shirley: now 89 years old, and 51 years ago the first African-American tenor to sing leading roles at the Metropolitan Opera. Another magnificent African-American vocalist, the baritone Sidney Outlaw, contributed three additional a cappella spirituals that, like George’s performances, seemed to eclipse all the other music-making that week. Himself a product of Brevard, North Carolina — in the Appalachians — Sidney Outlaw came to music through family and church: roots.

This week, The American Purpose — an invaluable centrist journal of government, politics, and the arts — published my further ruminations on the Brevard experience. And The American Scholar –– also a publication with due regard for the fate of the American arts — has concurrentlly published a related piece on Brevard by Douglas McLennan, editor/founder of ArtsJournal. We will be following up with a podcast– including George Shirley — in the coming weeks.

As I write in my American Purpose piece: because I interpolated spirituals into the festival’s culminating symphonic program, I discovered myself unwittingly testing an inescapable appropriation debate: does classical music “sanitize” the Black vernacular. The results were highly informative.

My article in The American Purpose follows:

THE SOUL OF BLACK CLASSICAL MUSIC

“Negro spirituals,” predicted Alain Locke in 1925, would undergo “intimate and original development in directions already the line of advance in modernistic music.… An inevitable art development awaits them, as in the past it has awaited all other great folk music.” Locke’s philosophy of the New Negro aligned with the high-culture predilections W. E. B. Du Bois. Like Du Bois, Locke mistrusted the popular musical marketplace in favor of elite realms of art: symphonies, sonatas, concertos.

Langston Hughes, in his seminal 1926 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” thought otherwise. He heard in jazz “the eternal tom-tom beating of the Negro soul.” He deplored an “urge toward whiteness” in concert-hall applications of Black music. Zora Neale Hurston, supporting Hughes, discerned a “flight from Blackness” in concert spirituals that “squeezed all of the rich Black juice out of the songs.”

This debate over whether Black classical music could convey an authentically Black sound wasn’t moral; it was essentially aesthetic—and plausible. The Black musical vernacular had already proven so fecund in ragtime and the blues that whether a Black concert song or symphony could resonate as elementally was (and remains) an understandable point of debate.

In the Black classical music repertoire belatedly being excavated today, the big find may well be William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony (1932) – effusively praised when Leopold Stokowski first performed it 1934. Referencing Antonin Dvorak’s New World Symphony, and Dvorak’s famous 1893 prediction that “Negro melodies” would foster “a great and noble school of music,” Locke declared that Dawson had here taken the “the same path” as Dvorak, only “much further down the road to native and indigenous musical expression.” Dawson’s symphony, Locke continued, was in fact “unimpeachably Negro.” Dawson himself said that his was a symphony that “only a Negro could have written.” What did he mean by that?

We know that Dawson visited Africa in the 1950s, was greatly stirred, and revised his symphony prior to its belated publication in 1963. The work as we know it begins with a heraldic horn call, a recurrent leitmotif symbolically linking Africa and America. The three movement titles are “The Bond of Africa,” “Hope in the Night,” and “O, Le’ Me Shine, Shine Like a Mornin’ Star!” Self-evidently, Dawson here attempts the portrait of a race.

The big central movement anchors the whole. It begins with a dolorous English horn tune not cradled by strings (like the immortal English horn tune of Dvorak’s symphony), but set atop a parched pizzicato accompaniment: “a melody,” Dawson writes in a program note, “that describes the characteristics, hopes, and longings of a folk held in darkness.” A weary journey into the light ensues. Its eventual climax is punctuated by a clamor of chimes: chains of servitude. Finally, three gong strokes that prefaced the movement—“the Trinity,” says Dawson, “who guides forever the destiny of man”—are amplified by a seismic throb of chimes and timpani. At Stokowski’s first performances, Dawson’s three-fold groundswell, a singular inspiration, ignited an ovation so prolonged that the Philadelphia Orchestra had to stand midway through this first hearing of a new work.

Over the summer, at North Carolina’s enterprising Brevard Music Festival, I had occasion to curate a series of concerts based on my book Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music. Because I interpolated spirituals into the culminating symphonic program, I discovered myself unwittingly testing the appropriation debate. The results were informative.

The two singers at hand set the highest possible bar. One was George Shirley–a legendary name. It was he who in 1961 became the first Black tenor to sing leading roles at the Metropolitan Opera. George is now 89 and still singing. The other Brevard singer, less than half George’s age, was the baritone Sidney Outlaw, whom I invited to sing three spirituals, a cappella, that were deployed in concert works by Dawson, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, and Margaret Bonds. My intention had been to cite the tunes these composers adapted directly ahead of the pertinent pieces. But Sidney Outlaw’s renditions were themselves spellbindingly self-sufficient.

The significance of the once famous British composer Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912) is that Du Bois anointed him the Great Black Hope of classical music – the man who could do the job. At Brevard, we heard Coleridge-Taylor’s “Keep Me from Sinkin’ Down” for violin and orchestra (1912). It’s a beautiful piece – but not as beautiful as an earlier composition it evokes: Dvorak’s Romance for violin and orchestra. It also suffered in comparison to Sidney Outlaw’s hushed, slow-motion chant of the spiritual itself. The warnings of Hughes and Hurston here come true: a product of the Royal Conservatory, Coleridge-Taylor was ultimately too genteel to fulfill the hopes of Dvorak, Du Bois, and Locke.

The Margaret Bonds piece – her biggest for orchestra – was the Montgomery Variations (1964). She here mourns the Montgomery Sunday school bombing of 1964, in which four children died. Every movement adapts “I Want Jesus to Walk with Me” – sung at our concert by Sidney Outlaw. Of the Black concert composers coming after Coleridge-Taylor, Bonds (1913-1972) is the most notably poli-stylistic; she draws on gospel and the blues. But her orchestral writing is too bland, too conventional, to stand up to a sorrow song born in back-breaking toil and de-humanizing oppression.

Our concert closed with the Dawson symphony. Here Sidney Outlaw sang “Oh My Little Soul Gwine Shine,” one of several spirituals Dawson embeds. But Dawson’s symphony did not register as a “flight from Blackness.” It gripped and held. It is worth pondering why.

At Brevard, George Shirley heard the Dawson symphony in live performance for the first time. He remarked, admiringly, that the work surprised him at every turn—but that every surprise instantly seemed “right.” This observation, I think, helps us understand what registers as “authentic” – “unimpeachably Negro” – about this Black symphony: it feels spontaneous, even improvisational: hallmarks of the Black popular genres we well know. And this is mainly a function of Dawson’s ingenious handling of musical structure. Even though the first movement is a sonata form, its components are so cleverly integrated that the seams never show. It builds cunningly to a central eruption—an outburst of strutting syncopations whose lightning physicality is irresistible. The texture of all three movements prickles and percolates with interior detail. The complex writing for percussion must owe something to the polyphonic drumming Dawson heard in Africa.

In short, Dawson retains proximity to the vernacular. He seizes the humor, pathos, and tragedy of the sorrow songs with an oracular vehemence. His symphony exudes a vernacular energy driven by an exigent cause.

How important is the Negro Folk Symphony? A conductor of my acquaintance, who has performed it, calls it the most formidable American symphony subsequent to the symphonies of Charles Ives. That is: Dawson in his opinion eclipses the long canonized Third Symphonies of Aaron Copland and Roy Harris. The recording to hear, sitting on YouTube, is Stokowski’s from 1963. There also exists a YouTube video of a performance by the late Michael Morgan with a distinguished all-Black ensemble: the Gateways Orchestra. How I wish Gateways had programed the Dawson symphony for their Carnegie Hall debut last April.

The high point of the Brevard “Dvorak’s Prophecy” festival was non-symphonic: “George Shirley: A Life in Music.” It comprised a series of reminiscences and reflections, punctuated by recordings by Roland Hayes, Marian Anderson, and George Shirley himself.

Like the festival’s closing orchestral concert, with the Dawson symphony, this afternoon event felt instructive. I am not the only one for whom four rapt performances by Hayes, Anderson, and Shirley somehow eclipsed all the other music heard that week. That all four were delivered by Black artists was not really surprising.

Of the sorrow songs, Du Bois unforgettably wrote:

“Little of beauty has America given the world save the rude grandeur God himself stamped on her bosom; the human spirit in this new world has expressed itself in vigor and ingenuity rather than in beauty. And so by fateful chance the Negro folk-song—the rhythmic cry of the slave—stands to-day not simply as the sole American music, but as the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side the seas. It has been neglected, it has been, and is, half despised, and above all it has been persistently mistaken and misunderstood; but notwithstanding, it still remains as the singular spiritual heritage of the nation and the greatest gift of the Negro people.

“Through all the sorrow of the Sorrow Songs there breathes a hope—a faith in the ultimate justice of things. The minor cadences of despair change often to triumph and calm confidence..… Sometimes it is faith in life, sometimes a faith in death, sometimes assurance of boundless justice in some fair world beyond. But whichever it is, [T]the meaning is always clear: that sometime, some- where, men will judge men by their souls and not by their skins. Is such a hope justified? Do the Sorrow Songs sing true?”

October 7, 2022

Toradze Memorial Concert

The recent Alexander Toradze Memorial Concert, featuring more than a dozen pianists, is now accessible online here.

In addition to a lot of music, this event features three video clips of Lexo speaking and performing.

A Toradze memorial festival will be held in Tbilisi, beginning May 30, 2023, (Lexo’s birthday) with a concert including Vladimir Feltsman performing Mozart’s K. 595 Piano Concerto. The Artistic Director will be Edisher Savitski.

A commemorative CD, including Lexo performing his father’s Piano Concerto, is also planned.

Thank you to Joe Patrych, for hosting the Memorial Concert at Klavierhaus (NYC), and to Behrouz Jamali, for his extraordinary Toradze film.

Lexo’s premature departure is still being processed by those of us who were privileged to know him.

September 11, 2022

Did Kurt Weill “Look Back”?

My favorite recording of any Kurt Weill song – as I have occasion to remark at the close of my recent NPR documentary on Weill’s immigrant odyssey – is Weill’s own rendition of “That’s Him.” Re-encountering this remarkable performance, with the composer accompanying himself at the piano, I feel a need to ponder what makes it so special.

As I observed on the radio:

“It’s a song from his 1943 show One Touch of Venus, originally sung by Mary Martin. So it’s supposed to be sung by a woman. . . . It’s yet another face of Kurt Weill – that of the worldly immigrant, of the New York cosmopolite. It magically evokes the sophistication of Broadway 80 years ago. And the words couldn’t be more distant from the sardonic political wit of Weill’s Berlin partner Bertolt Brecht. They’re by the poet Ogden Nash, who specialized in urbane nonsense rhymes. So this is a love song unlike any other – it achieves romantic effusion via whimsical understatement.”

Nash begins:

You know the way you feel when there is autumn in the air

The way you feel when Antoine has finished with your hair

That’s him.

Nash rhymes about the way you feel “when you smell bread baking . . . The way you feel when a tooth stops aching…. ”

The song peaks with a veritable paean of understatement. The romantic object of desire is:

Not arty, not actory

He’s like a plumber when you need a plumber

He’s . . . satisfactory.

As sung by Weill, this love song is not a love song. You can hear that it’s supposed to be by listening to Mary Martin sing it – a beautifully calculated interpretation, with its calibrated dynamics and sweet portamentos. (She was a trained soprano.)

But it is Weill’s interpretation that’s “not arty, not actory.” Its keynote is the first sentence: “You know how you feel when there is autumn in the air.” For Weill, “That’s Him” becomes a personal expression of twilit serenity. And it’s about Weill himself: a self-portrait.

What’s more: the same twilight tone inflects Weill’s two most popular Broadway tunes: “Speak Low” and “September Song.” Like “That’s him,” “Speak Low” comes from One Touch of Venus, with words by Ogden Nash:

Speak low when you speak love

Our summer’s day withers away too soon, too soon

Speak low when you speak love

Our moment is swift like ships adrift

We’re swept apart too soon

Speak low, darling speak low

Love is a spark, lost in the dark

Too soon, too soon

I feel wherever I go that tomorrow is near

Tomorrow is here and always too soon

Time is so old and love so brief

Love is pure gold and time a thief

We’re late, darling, we’re late

The curtain descends, everything ends

Too soon, too soon

I wait, oh darling, I wait

Will you speak low to me, speak love to me and soon?

The words for “September Song” are Maxwell Anderson’s:

When I was a young man courting the girls

I played me a waiting game

If a maid refused me with tossing curls

I’d let the old Earth take a couple of whirls

While I plied her with tears in lieu of pearls

And as time came around she came my way

As time came around, she came.

When you meet with the young girls early in the spring

You court them in song and rhyme

They answer with words and a clover ring

But if you could examine the goods they bring

They have little to offer but the songs they sing

And a plentiful waste of time of day

A plentiful waste of time.

Oh, it’s a long, long while from May to December

But the days grow short

When you reach September

When the Autumn weather turns the leaves to flame

One hasn’t got time for the waiting game

Oh, the days dwindle down to a precious few

September, November

And these few precious days

I’ll spend with you

These precious days

I’ll spend with you.

As it happens, Weill recorded “Speak Low” – and it sounds like this. He never recorded “September Song” – but he should have, because he would have been the perfect interpreter.

Long ago, when a music critic for the New York Times, I had the privilege of interviewing Weill’s widow, Lotte Lenya, in her Manhattan apartment. She said: “The old-timers were always talking about the past. And Weill never did. Never. Because they would always talk about how marvelous it was in Berlin. And Kurt was always looking ahead. He didn’t want to look back.”

Certainly “Speak Low” and “September Song” explicitly “look ahead” – to “precious days” to come. But the affect of these songs, and of “That’s Him” as rendered by Weill – is autumnal. It would be imprecise to call them “nostalgic.” But they convey a journey’s end. They register, retrospectively, a crucible now mainly past – fleeing the Nazis, skimming Paris and London, tackling the Broadway hegemony of Rodgers & Hammerstein.

Who was Kurt Weill? Judging from his correspondence with Lenya, his personality wasn’t exactly becalmed. The letters allude to frustrations and rivalries. In one (June 4, 1944), Lenya writes (in her acquired English): “Maybe after the war you will have a chance to write operas again and then see what will be left of that Hillbilly show ‘Oklahoma.’ That music sounds dummer and dummer every time I hear it. There is something about tradition and it cant be pound into people. It has to grow trough centuries. Evidently. So lets be patient and be grateful for the little white house we got out of spite of them not knowing your real value.”

But “That’s Him,” “Speak Low,” and “September Song” transcend every second thought, every regret and sorrow. They exude reconciliation. And this autumnal dimension enlarges these songs in special ways. As Lenya testified, Weill didn’t wish to “look back.” But he could not wholly ignore his tumultuous past. Weill died young – at the age of fifty. Whence his twilight tone? His fraught saga of flight, immigration, and assimilation, I believe, can be read into “time is so old, and love so brief.”

A footnote: Weill’s delivery seamlessly mates speech and song. That’s part of its magic. Artur Rubinstein, summarizing the supreme art of Feodor Chaliapin, observed that he sang with the same voice with which he spoke. Cf.: “The Greatest Vocal Recording of All Time.“

September 6, 2022

Kurt Weill’s Immigrant Odyssey on NPR

Kurt Weill, a refugee from Nazi Germany, turned himself into one of Broadway’s leading composers – an amazing feat of assimilation. After the war, he only returned to Europe once, in 1947 – and reported: “Strangely enough, wherever I found decency and humanity in the world, it reminded me of America.”

How does that sentiment play today? It’s a question posed and pondered in my latest NPR “More than Music” documentary, which treats Weill’s odyssey as a lesson in immigration. The commentators include the social critic John McWhorter and the Weill scholar Kim Kowalke, both of whom reference Weill’s anti-apartheid musical Lost in the Stars (1949) – an implicit condemnation of Jim Crow.

Kowalke says: “There’s no question that when he arrived [in 1935] Weill believed in the American dream. . . . That love of country persisted. . . . But like so many others after the war Weill felt that the American dream had been punctured. And I often think — what if he had lived to see what’s going on in this country today? How would he respond?” Maybe, Kowalke continues, with the “bleak warnings” about the “fragility of democracy” earlier to be found in Weill’s Die Bürgschaft (1931) and Der Silbersee (1933).

Asked “What makes Weill Weill?”, Weill himself is heard commenting, on a 1941 radio broadcast: ”I seem to have a very strong awareness of the sufferings of underprivileged people.”

Tracking Weill in Berlin, Paris, and Broadway, our broadcast samples historic recordings by Bertolt Brecht, Walter Huston, Todd Duncan, and Bobby Darin. And we hear terrific modern-day renditions, recorded in live performance at the Brevard Music Festival, by Lisa Vroman and William Sharp, by Brevard’s Janiec Opera Company, and by the Brevard Music Center Orchestra conducted by Keith Lockhart.

My own favorite Weill performance, which closes the show (at 42:20), is Weill himself singing a Broadway love song thathas nothing whatsoever to do with social justice: “That’s Him.” It’s yet another face of Kurt Weill – of the worldly immigrant, the New York cosmopolite. It magically evokes the sophistication of Broadway 80 years ago. And the words couldn’t be more distant from the sardonic political wit of Weill’s Berlin partner Bertolt Brecht. They’re by the poet Ogden Nash, who specialized in urbane nonsense rhymes — and who here conveys romantic effusion via whimsical understatement. Nash begins:

You know the way you feel when there is autumn in the air,

The way you feel when Antoine has finished with your hair,

That’s him.

Nash and Weill rhyme about the way you feel “when you smell bread baking,” the “way you feel when a tooth stops aching.” “That’s Him” peaks with a veritable paean of understatement. The romantic object of desire is

Not arty, not actory.

He’s like a plumber when you need a Plumber.

He’s . . . satisfactory.

Accompanying himself at the piano, Weill is himself “not actory.” Mary Martin, who sang “That’s Him” on Broadway, sounds “arty” by comparison. Weill is here the “plumber”: no less than the song, his rendition divinely celebrates the quotidian.

To listen to the show, click here

LISTENING GUIDE:

00:00 – Bobby Darin and Bertolt Brecht sing “Mack the Knife”

3:20 – Walter Huston sings “September Song”

4:40 – Weill on the radio show “I am an American” (1941)

7:00 – Lisa Vroman and William Sharp sing “How Can You Tell an American?”

9:00 – John McWhorter on Weill’s notion of “America”

12:16 – The Seven Deadly Sins, with commentary by Keith Lockhart

17:45 – Lisa Vroman sings “My Ship”

22:00 – Weill sets Walt Whitman in response to Pearl Harbor

25:40 – The Ice Cream Sextet from Street Scene

31:40 – Kim Kowalke on Weill and social justice

35:00 – John McWhorter on Lost in the Stars

38:20 – Kim Kowalke on Weill and the American dream

42:20 – Weill sings “That’s Him”

FOR A RELATED BLOG, click here.

July 5, 2022

Mocking Freedom? What To Do With the “Star-Spangled Banner”

My July 4 “More than Music” special for National Public Radio seems to me the hottest radio show I’ve ever managed to produce. The topic is The Star-Spangled Banner – as an instrument for exploring issues of race and national identity. You can hear it here.

The Star-Spangled Banner is controversial today for three reasons. The first is that Francis Scott Key, who wrote the words, owned slaves. The second is that the little-known third verse references “hireling and slave” – and we’re not sure what that means. The third is that American identity is being scrutinized as never before in living memory – what does it mean, right now, when we sing “land of the free”?

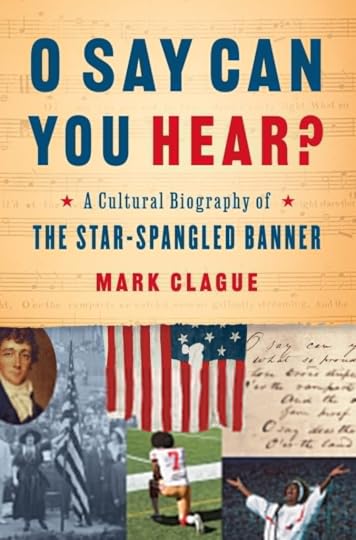

The music historian Mark Clague, who invaluable partners the broadcast, has written an important new book: Oh, Say Can You Hear? It’s a “cultural history” of The Star-Spangled Banner. Mark has many answers. He tells us that Key both owned slaves and, as an attorney, freed nearly 200 enslaved Black Americans. He explains that “slave,” in Key’s third verse, doesn’t refer to African-Americans (which, he adds, doesn’t let Key off the hook).

And Mark eloquently makes a case for retaining The Star-Spangled Banner – with two revisions. As part of our national inheritance, it stands witness to our history; it changes significance over time; it instigates a virtual “conversation” about the shifting meaning of American patriotism.

The outstanding African-American bass-baritone Davone Tines, however, finds The Star-Spangled Banner “colonialist” and “bellicose.” He builds a case for a new national anthem: “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” The “Black national anthem,” it’s as harmonious and inclusive as Keys’ song is (“conquer we must”) is martial.

A third participant in the show is the eminent Civil War historian Allen Guelzo, who tackles a related issue: what to do with statues of Francis Scott Key and other famous slave-owners? Leave them alone, he argues. We are an increasingly forgetful nation. We need to possess a national past.

Along the way, partnered by Peter Bogdanoff’s technical wizardly, I sample renditions by Jimi Hendrix, Aretha Franklin, Whitney Houston, Morton Gould, and Igor Stravinsky, among others. And we also hear two of the more than 500 (!) alternative verses for The Star-Spangled Banner – a post-Civil War anti-slavery lyric by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., which Clague believe should be formally adopted; and a bitterly sarcastic 1844 Abolitionist lyric that, when we hear it sung, chills the spine:

Oh say, do you hear, at the dawn’s early light,

The shrieks of those Bondmen, whose blood is now streaming

From the merciless lash, while our Banner in sight,

With its stars, mocking Freedom, is fitfully gleaming?

Do you see the backs bare, do you mark every score

Of the whip of the driver trace channels of gore

Oh Say does that Star-Spangled Banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free, and the home of the brave?

Here’s a listener’s guide:

7:40 – A close look at Whitney Houston’s 1991 Super Bowl rendition

11:00 – Stravinsky’s version, for which he was accused of “tampering with national property”

14:00 – A close look at Francis Scott Key and slavery

15:04 – What does Key mean by “hireling and slave”?

18:00 – Allen Guelzo on those statues, and related matters

25:00 – Davone Tines on “a demonstrably toxic way of building a foundation for a nation”

26:00 – The Star-Spangled Banner recast as an Abolitionist salvo

33:30 – “Hail Columbia” as an alternative to The Star-Spangled Banner

35:00 – Antonin Dvorak’s alternative to The Star-Spangled Banner

37:00 – Davone Tines’ alternative to The Star-Spangled Banner

43:30 – Mark Clague’s “new verse,” courtesy of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

You can link to previous “More than Music” radio documentaries via the bottom of my home page.

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers