Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 15

January 7, 2022

Dvorak’s Prophecy — A “Systematic Curatorial Effort”

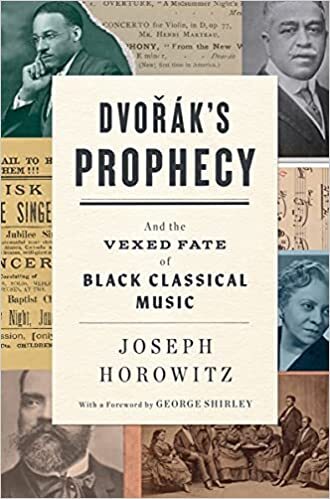

The author most recently interviewed by Richard Aldous, in his always lively “Book Stack” series for The American Purpose, happens to be me, talking about Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music. You can hear our 30-minute chat here.

At one point, 22 minutes in, Richard in a surge of effusion pronounces: “Your time has come.” He references the new Philadelphia Orchestra recording of two Florence Price symphonies, and other evidence that American orchestras are finally attending to music forgotten and otherwise overlooked.

Not so fast, I reply. The rush to perform music by Black composers is more than welcome – but “we need a more systematic curatorial effort” based “on an informed overview.” In particular, I continue (casting further aspersion on Richard’s optimism), if American orchestras are to enjoy a “formidable future” they must once and for all embrace “our greatest composer” of concert music: Charles Edward Ives.

Ives, I opine, is not only a victim of a modernist “standard narrative” into which he does not fit; he is also an object of prejudice – that his music is “difficult.”

Of the six Dvorak’s Prophecy films just released by Naxos in tandem with my book, “Charles Ives’ America” is an impassioned act of advocacy. It maintains that Ives should become known as a member of the same supreme New World cultural pantheon as Walt Whitman and Herman Melville – and that, moreover, “he can become known.” His music is in fact “readily appreciable.” Here’s the trailer to the Ives film, with fabulous visual treatments by Peter Bogdanoff:

For more information on the Dvorak’s Prophecy films, click here.

December 16, 2021

John McWhorter on “Dvorak’s Prophecy”

In his New York Times column two days ago, John McWhorter wrote of Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music: “Horowitz has taught me a new way of processing the timeline of American classical music. . . . His lesson should resound.”

Attending Porgy and Bess at the Met, McWhorter continued, “I experienced the opera for the first time as an imperious touchstone rather than as a fascinating question. . . . Horowitz teaches us to stop hearing Porgy and Bess narrowly, as a Black opera, or as some sideline oddity called a folk opera. It is what opera should be in this country, with our history, period. Under this analysis, the scores to Copland’s Billy the Kid and Rodeo, for all their beauty, are the fascinating but sideline development, not Porgy and Bess.”

I long ago discovered that an author cannot really control the content of a book. It will read differently for different readers. This is not only because different readers are people different from the author, but because the ways in which I may process and present information in a book are personal, erratic, at times incidental.

What most brought this home to me was my most extravagantly praised and reviled opus: Understanding Toscanini: How He Became an American Culture-God and Helped Create a New Audience for Old Music (1987). This was a very long book with many balls in the air, flying at different heights and velocities. Descriptions of what I had written, in the “good” reviews, sometimes surprised me as much as the assaults from musicians, music historians, and music lovers who mainly registered trampled turf or a defilement of acknowledged deities.

Most recently the author of Woke Racism, McWhorter is more a social critic than a music critic. But he knows music (his take on the notorious Heinrich Schenker controversy at the University of Texas is the most sensible I have read). In the case of my Dvorak book, he has swallowed and digested it whole, then applied its findings in one commanding gesture. His Times column registers what any author craves – understanding of a writer’s intentions so true that he can run with it.

Here he is again:

“Porgy and Bess can feel, at times, messy. You never quite know what’s coming and might wonder whether it all hangs together. But that’s just it: Maybe as an American piece it shouldn’t hang together any more than America ever has. Horowitz cherishes this quality in what he regards as true American art in an eternally hybrid experiment of a nation, charting a commonality between the narratively baggy quality of Mark Twain’s greatest works and the splashy, smashed-up quality of so much of Charles Ives’s work, where despite the stringent classical structure overall, a folk tune can come crashing into the proceedings. Those who saw Copland as the real thing tended to find Ives’s work interesting but somewhat quaint and unfinished. But Horowitz points to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s thought that ‘in the mud and scum of things, there alway, alway something sings.’ That mud and scum, for Emerson, was what we now call authenticity.”

Yes, yes, and yes. I discard the modernist paradigm that assumes that nothing of real interest was composed by an American before 1915, that views Ives and Gershwin as gifted amateurs, that for decades patronized Porgy and Bess as if it were not an overwhelming cathartic experience (in a good production).

In my book, I find Emersonian “mud and scum” not only in Ives (who himself cited this poem), but other self-made, “unfinished” American creators, including Whitman, Melville, and Twain. Emily Dickinson and William Faulkner (my favorite American novelist, who was no Henry James) also fit this list. And extolling the necessary pertinence of the Black vernacular to American creativity, to the perenialy unfinished project of national identity, I cite W. E. B. Du Bois and Ralph Ellison, William Levi Dawson and Toni Morrison.

I think it can be agreed that modernism is over – but the obituaries remain insufficiently framed. In the closing pages of Dvorak’s Prophecy, I write:

“The new American classical-music paradigm I have here proposed, reaching into the past, treats the twentieth century as an aberration in an Ur-narrative. The modernist juggernaut, whatever its triumphs, elevated art to lonely heights. It cherished highbrow pedigrees. It also punished the past. The triumphs remain. But the punishments, whether inflicted by Van Wyck Brooks and Lewis Mumford, or by Alfred Barr’s Museum of Modern Art, proved transient. It is time that the American musical pastlessness proclaimed by Virgil Thomson, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein also be put to rest.”

The revisionist reckoning I have attempted to apply to American classical music will doubtless resonate in other fields of American creative and intellectual endeavor. The rehabilitation of John Singer Sargent (for decades dismissed by modernists as a society painter) is a related phenomenon I could not resist inserting in Dvorak’s Prophecy. The historian Allen Guelzo – an appreciative reader of my book – adds:

“The fate of American classical music has a definite parallel to American philosophy in the same period. The cognate to Dvorak and Dawson is the collegiate moral philosophy tradition and the idealist pragmatism of Charles Sanders Peirce and Josiah Royce. All of them were consigned to the same “pastlessness,” and a new philosophic narrative was created around William James and John Dewey in much the same way that a new musical narrative was confected by Virgil Thomson and Aaron Copland.”

Did American philosophy begin with William James? Did American intellectual history slumber through the Gilded Age? Some people think so — still.

For information on the six “Dvorak’s Prophecy” documentary films just released by Naxos, click here.

For readers who discover a paywall attempting to access John McWhorter, here’s part of what he wrote:

“Much of the history of classical music in America has been written as if indigenous American musical forms were ultimately insufficient to form the basis of mature art, such that Dvořák’s call fell largely upon deaf ears. . . . Joseph Horowitz writes in his new book, Dvořák’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music, that in the first half of the 20th century, a cadre of American composers created American classical music that either held Native American and Black music at an arm’s length or ignored it . . .

“Hence, the music of Aaron Copland, in works such as Appalachian Spring, is often treated as where American classical music went for real, with Porgy and Bess often treated as a zesty but idiosyncratic business created by an undertrained upstart. One can love Porgy and Bess deeply and yet fall for this perception . . .

“No more: Horowitz has taught me a new way of processing the timeline of American classical music. If Dvořák’s counsel made sense — that is, if America is to develop a native classical music in the sense that a Bartók used Hungarian folk music to shape his work — then the through line runs directly through “Porgy and Bess.” Taking in the Metropolitan Opera’s fine production a few days ago, I experienced the opera for the first time as an imperious touchstone rather than as a fascinating question. . . .

“Porgy and Bess can feel, at times, messy. You never quite know what’s coming and might wonder whether it all hangs together. But that’s just it: Maybe as an American piece it shouldn’t hang together any more than America ever has. Horowitz cherishes this quality in what he regards as true American art in an eternally hybrid experiment of a nation, charting a commonality between the narratively baggy quality of Mark Twain’s greatest works and the splashy, smashed-up quality of so much of Charles Ives’s work, where despite the stringent classical structure overall, a folk tune can come crashing into the proceedings. Those who saw Copland as the real thing tended to find Ives’s work interesting but somewhat quaint and unfinished. But Horowitz points to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s thought that “in the mud and scum of things, there alway, alway something sings.” That mud and scum, for Emerson, was what we now call authenticity.

“Black composers, of course, created truly American classical music of this kind — William Dawson’s smashing Negro Folk Symphony is one example. Yet Porgy and Bess qualifies, despite its white creators, as a keystone of where truly American classical music had gone by its time, as well as one guide for where it should go. . . .

“Horowitz teaches us to stop hearing Porgy and Bess narrowly, as a Black opera, or as some sideline oddity called a folk opera. It is what opera should be in this country, with our history, period. Under this analysis, the scores to Copland’s Billy the Kid and Rodeo, for all their beauty, are the fascinating but sideline development, not Porgy and Bess. Broadway pieces incorporating Black and immigrant musical styles that play plausibly in opera houses, like Kurt Weill and Langston Hughes’s Street Scene and Marc Blitzstein’s Regina, are less collectors’ oddities than pavers on the path to true American classical music, landing farther from the bull’s-eye than Porgy and Bess but worth attending to.

“Horowitz has taught me to listen to Black classical music as what the most American of classical music is. His lesson should resound.”

November 27, 2021

DVORAK’S PROPHECY on NPR — Are the Arts Still a “Fit Topic” for Historians?

At the conclusion of the National Public Radio feature I’ve produced about “The Fate of Black Classical Music,” Jenn White – who so graciously hosts the daily newsmagazine “1A” – asks me:

“In the Foreword to your new book Dvorak’s Prophecy, George Shirley – the first Black tenor to sing leading roles at the Met — writes: ‘Because of our current conversation about race, we now observe a seemingly desperate effort to make up for lost time, to present Black faces in the concert hall. But if it’s going to become a permanent new way of thinking, there has to be new understanding.’ What does he mean by that?”

I answer:

“George Shirley is 87 years old — he’s seen a lot. And as we’ve heard him say, he’s witnessed steps forward in race relations in America, and backward steps coming after those. When he talks about ‘a permanent new way of thinking,’ he means permanent change — not ephemeral change, as we’ve seen in the past. And he’s referencing what I call a ‘usable past’ – lasting cultural roots.

“You know, I went to a prestigious liberal arts college [it was Swarthmore]. I graduated a long time ago, in 1970. I majored in History. And in my four years there I never once heard the name W. E. B. Du Bois. And I certainly did not read Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk, which today I regard as pretty much obligatory reading for educated Americans. Du Bois, his book – they’re part of a usable American past, something we can all utilize as an anchor.

“George Shirley references ‘a seemingly desperate effort.’ What is this about? It says that we have to rethink the concert experience in our concert halls, on our campuses. We need to rethink the learning the experience. It’s not enough just to perform Black classical music. We should use the story of Du Bois, the story of Dvorak, the story of Harry Burleigh. We need to tell stories about the American past in order to anchor a constructive American future.”

It’s my good fortune to be creating 50-minute radio documentaries for Rupert Allman, the producer of “1A.” Rupert welcomes “deep dives” into timely topics. In the case of “The Fate of Black Classical Music” (which aired on Thanksgiving), the big picture – as in my book – has to do with prioritizing something in ever shorter supply in our United States: informed historical memory. A good chunk of our show is dedicated to an exchange with the historian Allen Guelzo, whose recent biography of Robert E. Lee is an exemplary instance of “using the past” with integrity and informed understanding. Guelzo is also the rare American historian who really knows the arts, including classical music. I asked him why American historians have failed to document Black classical music. He answered:

“Historians who write about music history are usually to be found in conservatories or in Music departments. But they’re not usually found in History departments. Now perhaps the reason for that is that the people who populate History departments simply don’t see the arts as part of their turf . . . And there is a certain professional segregation that goes on that way — which suggests, however faintly and however politely, that culture is not really a fit topic of interest for historians.”

Guelzo observes that “we don’t educate people in music the way we once did.” No Child Left Behind and STEM, he continues, “have been death for arts education, especially in music. . . . Nothing surprised me more in writing Robert E. Lee – A Life than tripping over the odd fact that when Lee was Superintendent of West Point, the faculty got together to play Schumann and Mendelssohn string quartets.”

A prominent recent history of the US – Jill Lepore’s wonderfully readable These Truths – delves deeply into issues that matter today, including slavery and race. But there isn’t a single sentence on the arts. I asked Guelzo what he made of that. He replied:

“Part of it is the way historians are trained these days, in their graduate programs, which generally pay next to no attention to the arts. That was certainly my experience at the University of Pennsylvania. . . . Are we really adequately describing the lives that Americans have lived? . . . I think not. We’ve desperately shortchanged our understanding of the past.”

Guelzo calls classical music a “foreign country” for those who write about the US. “If any thought is given to classical music at all, it’s as a social representation of elite class identity. And yet classical music is an enormously supple conveyer of social meaning.”

And so it is with Black classical music, and with the American Dvorak. When Allen Guelzo says that William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony and George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess “prove that Dvorak was right” when he prophesied that “Negro melodies” would foster a “great and noble” school of American classical music, Guelzo means that these artworks absorb and dignify core aspects of the American experience, enduring American truths. I comment:

“The story of Black classical music is both black and white. It includes W. E. B. Du Bois and William Dawson – and also Antonin Dvorak and George Gershwin. It also includes, in glorious fulfillment of Dvorak’s prophecy, Porgy and Bess – whose most fervent admirers included the members of the original 1935 cast.

“In the wake of Gershwin’s sudden, shocking death in 1937, a memorial concert was held at the Hollywood Bowl. The participants included Ruby Elzy, a gifted Black soprano who sang Serena in the original Porgy production on Broadway. Elzy, too, would die young – of a botched operation. She had been planning to sing Verdi’s Aida – for a Black opera company. Ruby Elzy’s rendition of ‘My Man’s Gone Now,’ at the Gershwin Memorial Concert, is the most extraordinary performance I know of any selection from George Gershwin’s opera. The aria itself is steeped in the yearning of the sorrow songs. The performance combines the bluesy pathos of Billie Holliday with the operatic splendor of a young artist on the cusp of what would have become a notable career. It is Ruby Elzy’s keening lament for the departed composer.”

You can hear Ruby Elzy sing “My Man’s Gone Now” – and the rest of the NPR feature – here (scroll to the bottom of the page for a time-code and use your cursor to naviage). And here’s an outline of the show:

PART ONE:

William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony (1934), why it matters, and why we don’t know it. With commentary by the late conductor Michael Morgan (8:00) and by Angel Gil-Ordóñez, who conducts the DC premiere this March with PostClassical Ensemble (9:00).

PART TWO:

George Shirley (12:05) remembers how Rudolf Bing desegregated the Metropolitan Opera. Allen Guelzo (18:00) ponders why American historians ignore the arts. Ruby Elzy sings “My Man’s Gone Now” (27:00).

PART THREE:

Excerpts (30:00) from PostClassical Ensemble’s Nov. 14 “narrative concert” – “The Souls of Black Folk” — at D.C.’s historic All Soul’s Church, with music by Harry Burleigh, Margaret Bonds, and Florence Price, plus readings from Du Bois, Langston Hughes, and Margaret Bonds. The participants include students from Howard University, and the Chorale of the Coalition of African-Americans for the Performing Arts. The final work is Price’s Suite for Brasses and Piano(1949), in its first performance (by pianist Elizabeth Hill with members of PCE conducted by Angel Gil-Ordóñez) in more than half a century (40:00).

–For more on PCE’s Black Classical Music Festival, click here.

–For more on my new book “Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music,” click here.

–For more on the six “Dvorak’s Prophecy” documentary films just released by Naxos, click here.

November 23, 2021

Dvorak’s Prophecy — A Two-Hour Webcast

My brand-new book Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music (already a best book of the year in The Financial Times and Kirkus Reviews) proposes a “new paradigm” for the history of American classical music.

Replacing the modernist “standard narrative” popularized by Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein, it begins not ca. 1920 but with the sorrow songs so memorably extolled by W E. B. Du Bois and Antonin Dvorak. Emphasizing proximity to vernacular speech and song, it privileges Charles Ives and George Gershwin as our two great creative talents. And it necessarily incorporates the Black Classical Music now being belatedly exhumed.

In effect, I am presenting a buried lineage, beginning with the American Dvorak and proceeding to Harry Burleigh, Nathaniel Dett, William Levi Dawson, Florence Price, William Grant Still – all of whom absorbed Dvorak’s roots-in-the-soil Romantic cultural nationalism. The peak achievements here include (I would say) Burleigh’s “Steal Away” and (setting Langston Hughes) “Lovely Dark and Lonely One,” Dett’s The Ordering of Moses, and Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony.

Another way of looking at it all is to fix on the composers left out of the standard narrative – the American Dvorak, Burleigh, Ives, Gershwin, Dawson – and also, e.g., Silvestre Revueltas, Bernard Herrmann, and Lou Harrison. (My series of “Dvorak’s Prophecies” films, just now released on Naxos, includes treatments of Ives, Dawson, Herrmann, and Harrison.)

These eight “left out” composers have long been explored and promoted by PostClassical Ensemble and my PCE colleague Angel Gil-Ordonez – and the most recent “PostClassical” webcast, on WWFM, is dedicated to Dvorak’s Prophecy and compositions by these eight formidable American voices. In conversation with Angel and the inimitable Bill McGlaughlin, we ask and re-ask: “How is it possible these pieces aren’t known?” Angel calls the American neglect of Ives “the biggest mystery in American music.” I comment that Revueltas is “the composer we should be studying right now” – because he knows how to embed the call for social justice into enduring works of art.

Basically, American classical musicians have lacked curiosity about American music; they remain fundamentally Eurocentric. In my book, I treat this as a larger American self-affliction; the epigraph quotes George Santayana: “The American mind does not oppose tradition it forgets it.”

And this matters more than ever. Never before have we so urgently needed a common cultural inheritance to foster a newly consolidated national self-awareness.

This is a need so acute that it isn’t noticed or discussed.

Here (below) is a Listeners Guide for our three-part WWFM webcast. Profuse thanks, as ever, to David Osenberg, who makes WWFM the nation’s most enterprising classical-music radio station.

For information on the book and the films: www.josephhorowitz.com

COMING UP: “DVORAK’S PROPHECY ON NPR: “1A” Thursday, Nov 25 at 10 am ET.

PART ONE:

00:00 – Harry Burleigh: Steal Away (Kevin Deas and Joe Horowitz at the National Cathedral)

7:00 – Burleigh as a forgotten hero of American music. His place in the new narrative proposed by Horowitz in Dvorak’s Prophecy, replacing the modernist “standard narrative” of American classical music

15:00 – Antonin Dvorak’s little-known “American” style after the New World Symphony. His American Suite, movement 3, performed by PostClassical Ensemble and Angel Gil-Ordóñez, for whom it proclaims “This is America!”

23:00 – Dvorak’s three American tropes: African-American, Native American, the American West. How to account for our continued ignorance of his later American output? Horowitz: “We’re just not interested in ourselves, we lack curiosity.” The Metropolitan Museum traces a lineage of American painting; the NY Philharmonic does not trace a lineage of American music.

29:00 – The “most striking omission”: Charles Ives. Gil-Ordóñez: the failure to play Ives is “the biggest mystery” in American music, “really a tragedy.”

36:00 – Ives: The Housatonic at Stockbridge (as presented in the new “Dvorak’s Prophecy” film “Charles Ives’ America”)

PART TWO:

00:00 – George Gershwin and “the Gershwin threat.” An under-rated Gershwin piece: the Cuban Overture, with its surprising Andalusian episode

2:08 – Gershwin Cuban Overture, performed by Angel Gil-Ordóñez and PCE

14:08 – Why don’t we know the Cuban Overture? It fails the criteria of modernism

18:55 – William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony: “buried treasure”

20:26 – Dawson’s symphony, movement 2: “Hope in the Night,” performed by Leopold Stokowski

41:00 – Could the Black musical motherlode that fostered popular genres have equally served American classical music?

PART THREE:

2:00 – Silvestre Revueltas: another major composer who falls outside the modernist narrative. Gil-Ordóñez: “another tragedy.”

8:15 – Revueltas: Redes (ending), with PCE conducted by Angel Gil-Ordóñez

11:52 – Why Revueltas is “the composer we should be studying right now” re: political art and social justice.

22:00 – Lou Harrison and his Violin Concerto

25:00 – Harrison Violin Concerto, movement 3, with Tim Fain and PCE led by Gil-Ordóñez

35:25 – Bernard Herrmann as “the most under-rated 20th century American composer”

38:00 – Herrmann’s Psycho Narrative performed by PCE and Gil-Ordóñez

November 21, 2021

Dvorak’s Prophecy, the CIA, and More

My two-hour conversation with Kirill Gerstein, who hosts an indispensable weekly “webinar” dealing with musical issues, mainly focused on my new book Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music.

But – as in my book (yesterday named one of the best of the year in The Financial Times) – many other topics were broached.

If you’re interested in sampling our exchange, here’s a handy Listener’s Guide:

8:00 – The saga of Aaron Copland as a parable about the fate of the American artist.

12:00 – Dvorak’s American legacy and Black Classical Music.

20:00 – Dvorak’s bluesy American style in the American Suite and Humoresques

28:00 – George Gershwin as the great hope of 20th century American classical music. “The Gershwin threat” of the interwar decades. “The Gershwin Moment” today.

38:00 – What to do right now? Curate the American past. How art museums get it right.

40:00 – Arthur Judson vs. Otto Klemperer and Dmitri Mitropoulos: how a “salesman of great music” displaced forward-thinking conductors as an arbiter of taste.

46:00 – Why American orchestras need scholars on staff. The critical lack of “symphonic Dramaturgs.”

54:00 – The debate over “cultural appropriation” and how it penalizes composers of consequence.

58:00 – Today’s big find in Black Classical Music: William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony.

1:06 – A huge topic: Charles Ives as a victim of the modernist “Standard Narrative.” Why his music must become better known. The Housatonic at Stockbridge.

1:16 – The comparable neglect of Mexico’s Silvestre Revueltas.

1:23 – The CIA, the cultural Cold War, and the modernist Standard Narrative – a glimpse at my forthcoming book The Propaganda of Freedom: JFK, Stravinsky, Shostakovich, and the Cultural Cold Warrior [Nicolas Nabokov]

1:30 – Why the US Government needs to play a bigger and more proactive role in support of the arts. How Richard Goodwin nearly became an influential arts advisor to JFK.

1:34 – The erasure of the arts from the American experience. We forget how much the arts once mattered more, as in the Gilded Age.

My thanks to Kirill.

November 14, 2021

Dvorak’s Prophecy — Online Wednesday

It’s my pleasure to be Kirill Gerstein’s guest this Wednesday for his “Kronberg Academy” online seminar – that’s at noon ET and you can register here.

To my knowledge, this series is unique. It dives deeply – for two hours – into musical topics. It attracts a distinguished international audience. I will be discussing my new book Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music, and also sampling the companion Dvorak’s Prophecy films I’ve produced for Naxos in collaboration with PostClassical Ensemble.

As many of you will know, Kirill Gerstein is a probing concert pianist with extensive jazz training – someone who performs the Gershwin concerto with improvised passagework. The example of Dvorak’s bluesy American piano style, in such little-known works as the F major Humoresque and American Suite, will be a topic of special interest.

We’ll also be talking about Aaron Copland and the Red Scare, about Charles Ives and Transcendentalism, and about the recovery of an amazing specimen of “Black Classical Music” – William Levi Dawson’s oracular Negro Folk Symphony.

November 5, 2021

“Die Meistersinger” in Covid Times

Lise Davidsen, Michael Volle, and Klaus Florian Vogt in the Met Meistersinger

Lise Davidsen, Michael Volle, and Klaus Florian Vogt in the Met MeistersingerLike every lifelong Wagnerite, I regard any opportunity to experience Die Meistersinger as special. It was my first opera at the Met, in 1962 – and also my most recent, last night. There have been half a dozen other Met Meistersingers in between. I’ve also encountered Die Meistersinger in San Francisco, Bayreuth, and Munich, and at the City Opera (in English).

These performances have varied greatly in certain details, but the sensation of Meistersinger uplift has been a constant. This time felt different: the opera’s central theme – the centrality of the arts in society, in a community of feeling, in a nation’s identity – today seems under siege. And of course there is the pandemic.

Die Meistersinger is an opera that must actually feel communal to register fully. On this occasion, there were swaths of empty seats downstairs, especially for acts one (because many arrived late) and three (or left early). I felt no tingling of expectancy from this scattered crowd. The fellow next to me occasionally examined his watch. The applause was tepid. Symptoms of indifference? Of unfamiliarity? Post-Covid disorientation?

The performance started slowly. The orchestra sounded soggy. Walther lacked the vocal heft to drive the act one climax. I felt I was witnessing an artifact from another epoch, dutifully mounted for posthumous inspection.

But act three told. It almost always does. Eva commences an erotic game: claiming that her shoes pinch (they do not), she makes Sachs fondle her foot. When Walther appears, resplendent, the real reason for her visit is disclosed: she stands transfixed. Sachs takes out his jealousy on his hammer and leather: “Always cobbling, that is my lot!” Wagner’s instructions here read: “Eva bursts into a sudden fit of weeping and sinks on Sach’s breast, sobbing and clinging to him. Walther advances and wrings Sachs’s hand. Sachs at last composes himself and tears himself away as if in vexation, so that Eva now rests on Walther’s shoulder.” Sachs is unmollified: he rails against clients who cannot be satisfied, against widowed cobblers being made a sport, against women generally. So Eva takes charge. It was you who awakened me to womanhood, she sings. And if it weren’t for Walther, I’d marry you instead. This strategic lie prods Sachs to a pivotal act of resigned self-understanding: he will never remarry. Seizing the moment, he announces a christening of Walther’s song. The godparents will be himself and Eva, the witnesses David and Magdalena. For good measure, he promotes David from apprentice to journeyman. And he appoints Eva to lead the ceremony. This takes the form of a quintet; the opera’s musical and dramatic apogee, it seals the personal transformation of all five participants. Eva has acquired the mettle of an adult. Walther has honed his unruly genius. David, with whose callowness we are acquainted, will now wed the older, more experienced Lena. And Sachs will remain a widower and an artisan, reconciled to the wisdom of age and the boldness of youth.

I wept. And again at the beginning of the second scene – where there is no cause for weeping. It’s all Nuremberg, celebrating a singing contest: Wagner’s tableau of a wholesome and united civic culture, fortified by music, poetry, and dance. Today: a seeming chimera.

Further impressions? Hans Sachs, Wagner’s shoemaker/philosopher/poet, is both serene and disconsolate, elevated and eruptive. Donald McIntyre, who sang Sachs at the Met in the 1990s, reportedly called him “bi-polar”; and McIntyre memorably clinched this character’s propensity to anger and dark introspection. In the current Met run, Michael Volle – like most Sachses — projects a more uniform benignity. But his range of mood and address remains varied and knit.

Sachs’s two scenes with Eva illustrate in microcosm the human dimension of this miraculous opera. She herself is a miracle: could Mathilde Wesendonck – here in part Wagner’s muse — have possibly married as much sweetness and innocence with so charming a propensity for guile? In Evchen, every morsel of shyness or deference is suspect. In act one, she’s instantly and recklessly in love with Walther. Harboring no illusions about Beckmesser, who will sing for her hand, she proceeds to enlist Sachs’s help with a cunning as natural as it is desperate. Playing on his impractical affection (he is her father’s age), she teases him with the possibility of herself becoming his wife – an exchange in which both know more than they dare acknowledge. The tables turn once Sachs, through feigned innocence, forces Eva to anxiously declare her actual mission: she needs to know how Walther fared earlier in the day. Will he become a mastersinger and hence eligible to wed her? Can Sachs assist? “For him all is lost,” Sachs replies in provocation. “Mister high and mighty – let him go!” Sachs having thus regained his composure, Eva loses hers. “It stinks of pitch here!” she exclaims and turns on her heel. “I thought so,” Sachs reflects. “Now we must find a way.”

Eva’s act two declaration that “an obedient child speaks only when asked,” and her father’s dim response (“How wise! How good!”), comprise a hilarious cameo of a relationship she surely rules. At the Met, Lise Davidsen’s straightforward delivery of this line summarizes the kind of detail her ingratiating Eva glides past. But her soprano commands a memorably radiant top (she over-balances the quintet) — and she seems a natural actress awaiting further instruction. Georg Zeppenfeld, as Pogner, is an artist of consequence with a voice just large enough for the Met’s over-sized auditorium. Johannes Martin Kranzle, the Beckmesser, fails to elicit sympathy (as the late Hermann Prey did opposite McIntyre’s Sachs); but his, too, is a portrait that tells. As for Klaus Florian Vogt’s underpowered Walther, I was at least grateful for his stamina and diction. Antonio Pappano, who conducts, savors the breadth of Wagner’s score. I appreciated the patience with which he weighted the pauses often prefacing its sublime moments.

If you are searching for a wholly satisfying Meistersinger experience on CD, good luck. The best I know is the 1936 Met broadcast conducted by Artur Bodanzky. Friedrich Schorr is Sachs – his signature part. Elisabeth Rethberg is Eva. The tenor is Rene Maison – an unremembered Belgian who if he materialized today would eclipse all competition in such parts as Walther, Florestan, Lohengrin, and Erik. I also recently sampled, on youtube, a 1949 Munich Meistersinger with the young Hans Hotter as Sachs, Eugen Jochum conducting. The act two Fliedermonolog is something to hear.

Re-experiencing Die Meistersinger at the Met in challenged times made everything else seem small. It was a good feeling.

October 26, 2021

Charles Ives’ America

“’Charles Ives’ America’ is very likely the most important film ever made about American music” – JoAnn Falletta, Music Director, The Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra

My forthcoming book, Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music (WW Norton, Nov. 25) links to six documentary films.

Of these, “Charles Ives’ America” attempts a landmark feat of advocacy. It argues that Ives not only deserves to be situated at the center of American classical music, but that he should become as generally well-known and esteemed as such American icons as Herman Melville and Walt Whitman.

The film strives to overcome the notion that Ives is esoteric — not readily approachable. It approaches Ives through his words and music, and also the Civil War, the Transcendentalists, and his Connecticut porch.

My collaborator Peter Bogdanoff has rendered such music as “The Housatonic at Stockbridge” and “The Alcotts” (both included in their entirety) with spellbinding visual panache. For “The ‘St. Gaudens’ in Boston Common” he has done more than that: in combination with James Sinclair’s inspired commentary, Peter has taken the most elusive of Ives’s signature compositions and fashioned a visual rendering that will electrify first-time listeners.

If any music seals Ives’ pertinence today, it is this 1911 “Black March” memorializing Colonel Robert Gould Shaw’s Black Civil War regiment as famously depicted by Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ Boston Common bas-relief, with its proud Black faces and striding Black bodies. As I write in Dvorak’s Prophecy, “Ives’s ghost-dirge is suffused with weary echoes of Civil War songs, plantation songs, minstrel songs: a fog of memory, a dream distillation whose hypnotic tread and consecrating ‘Amen’ close celebrate an act of stoic fortitude.”

In addition to Peter Bogdanoff and Jim Sinclair, my collaborators on the Ives film include the music historians Peter Burkholder and Judith Tick and two peerless Ives performers: the pianist Steven Mayer and the baritone William Sharp (accompanied by Paul Sanchez).

October 6, 2021

Arts Myopia

Here’s my piece in today’s “American Purpose,” Jeff Gedmin’s daily online magazine which valuably charts a centrist position not only with regard to government and politics, but also pays due attention to the arts.

The condition of the arts in the United States has never been more chaotic or confusing. The pandemic revealed – if such revelation was necessary – a general indifference to “saving our cultural institutions.” This priority was swiftly heeded in Europe with respect to orchestras, opera houses, theaters, and museums. Meanwhile, a new emphasis on social justice either buttresses our institutions of culture or maims them.

One thing is certain: More than ever, the arts need money. But from whom, and for what purpose? The traditional American model is laissez-faire: private sources, including corporate and foundation gifts. But private giving to arts and learning after the fashion of Carnegie, Mellon, Frick, and Rockefeller is not practiced by Gates or Bezos. The big charitable foundations, meanwhile, are no longer arts-focused. To understand this sea change, just watch, if you can, Derek Chauvin murdering George Floyd. The European model of robust government arts subsidies is one obvious fix, but there is no political will to repeat anything like FDR’s WPA, with its ambitious arts and literacy projects.

The current stress on diversity and inclusivity, however warranted, endangers or distorts a cultural canon that we cannot (in fact, must not) wholly jettison. Indeed, the canon is newly pertinent. Think, for instance, of how Herman Melville, Charles Ives, and William Faulkner reference the African-American experience in words and music. Melville’s Benito Cereno, about a Black slave rebellion at sea; Ives’ “The St. Gaudens in Boston Common,” conjuring the stoic heroism of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw’s Black Civil War regiment; Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, in which Black servants humanize and instruct a dysfunctional white dynasty, and Light in August, about a man who cannot tell whether he is Black or white– these are not instruments of social reform. Rather, they inexhaustibly ponder American racial inequities. If they are part of a common cultural inheritance that we must claim and refresh, they’re also incorrigibly elitist – not for everyone. What is worse, if you’re woke, Ives quotes Stephen Foster songs once sung in blackface. Faulkner’s personal take on segregation – which, as revealed in Michael Gorra’s exemplary The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War, does not diminish his fiction – was a product of its time. Melville’s lineage in Moby-Dick honors William Shakespeare, king of the white cultural patriarchs.

Enter Ask the Experts, by Michael Sy Uy. This new book, by an assistant dean of Harvard College, explores “How Ford, Rockefeller, and the NEA” (the National Endowment for the Arts) “Changed American Music.” The book’s central argument – that a “tight social network” has favored the advisory expertise and musical compositions of white males linked to “elite” and “prestigious” institutions, mainly in the northeastern United States – is both credible and unsurprising. Moreover, the book says, a disproportionate amount of money has gone to orchestras and opera companies to the detriment of folk and indigenous music, not to mention jazz.

Scouring public and private reports, Uy has amassed a detailed narrative spanning the years 1953 to 1976, an “explosive” period of arts and music funding. Ford’s music grants grew from zero to $3.4 million by 1974, with a peak of $81 million in 1966. Rockefeller’s music grants peaked at $7.8 million in 1957. NEA music grants rose to $25.1 million in 1977.

The Rockefeller Foundation prioritized university music centers that espoused serialism and other “advanced” non-tonal styles — what Winthrop Sargent, in The New Yorker, caustically dubbed “foundation music.” This music’s scientific patina resonated with the Rockefeller ethos. It was male and modern, insular and self-perpetuating. To Cold Warriors, including some in the CIA, it signified artistic freedom in contrast to lockstep Soviet Socialist Realism – in retrospect, a risible claim because serialism exerted its own tyranny. Uy names names: Virgil Thomson, Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, Lukas Foss, and Milton Babbitt repeatedly appear as Rockfeller “experts.” “It is “difficult not to pause and note,” Uy writes, “the gender and racial background of these ‘wise men’ who essentially served as gatekeepers.” He adds that “by ‘the arts,’ what the Rockefeller Foundation . . . had in mind were the high arts of the Western European tradition, and those located primarily in New York.”

The Ford Foundation, in comparison, was a bastion of traditional practice. Its experts were “not only non-practitioners but also conservative advocates of the status quo.” Ford’s signature arts initiative was its 1966 Symphony Orchestra Program: $80.2 million ($626 million today) gifted to 61 American orchestras in 33 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. This was the brainchild of McNeil Lowry, Ford’s activist arts and humanities head. He called the gift an “unprecedented act of philanthropy in the artistic and cultural life of a nation,” one that would help “the most universally established of cultural institutions.” A Ford annual report called it the “largest single amount ever given to the arts by any foundation.” Uy reports that Lowry was “initially concerned that federal entry into the arts field,” via the NEA, would “take away publicity from his own . . . program.” Uy also observes that “no one challenged the ‘universality’ of orchestras as a basic historical fact.”

The NEA itself, founded in 1965, was more egalitarian. Its “large and comprehensive system of panelists,” Uy writes, represented a “different approach to employing experts.” Its most proactive leader, Nancy Hanks, was a woman. Her music chief, Walter Anderson, was “the most powerful African American in government arts grant making.” Still, the NEA overwhelmingly favored “Western European high art organizations.“ Jazz and folk music constituted “only a fraction of its overall budget.”

Observing the grant-making process up close, Uy also documents an assortment of inevitable vagaries and inequities. What mattered was not only who sat on the panel but who happened to be in the room, since attendance could be erratic. And it mattered whether an application was reviewed when the panel was fresh or tired. Amid the mountain of statistics Uy has culled, notably impressive is the “Top Ten Foundation Recipients in Music, 2006-2015.” The Metropolitan Opera placed first, with $176.3 million from 2,059 grants. The Metropolitan Opera Association placed third, with $88.4 million from 1,327 grants. (The New York Philharmonic, by comparison, landed $67.6 million from 1,380 grants.) “One cannot emphasize enough,” Uy says, “the magnitudes of disparity. The Metropolitan Opera alone received more than six times what went to all folk and indigenous music groups combined.” He adds that donations from individuals whose household incomes were greater than $1 million exceeded foundation giving to arts and culture. It was all “profoundly undemocratic.”

Is Uy’s critique just? Finger-waving at Rockefeller and “foundation music” ignores what it felt like to engage with “contemporary music” in the 1960s. Tonal music was not respectable; to imply that Rockefeller could have somehow defied all conventional wisdom seems naïve. Also, Uy underrates Rockefeller’s Recorded Anthology of American Music, which made available the first recorded performances of historically important works by composers like Anthony Philipp Heinrich and Arthur Farwell under the supervision of music historians who knew something about Heinrich and Farwell. I wish that Uy had more to say about Rockefeller’s critique of Ford’s “deliberate rejection of academia as a vehicle for arts development in the United States:” In stark contrast to the museum community, the orchestras so lavishly supported by Ford made no attempt at liaison with scholars. This is one reason why orchestras failed to curate the American musical past, a defect – the topic of my forthcoming book, Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music – that mattered then and matters even more today. Classical music in the United States remains chronically Eurocentric; it lacks New World roots.

If the drift of Uy’s critique – that music funding was undemocratic and elitist – is undebatable, it leaves more important questions undebated. Do we still need a canon? If so, what should be included, what left out? Beethoven is an elite composer and opera an elite art form, but I cannot think of a more therapeutic art work right now than Fidelio. And what is Fidelio? The vast majority of educated people under the age of 30 probably cannot say. Are the arts therefore “dying?” Or, as I am told by members of the foundation community, are they newly “thriving,” empowered by a communal ethos that does not discriminate by gender, race, or class?

Orchestras are the elephant in the room. No other institutional embodiment of American culture has fallen so far or seems so clueless today. Here, the Ford Foundation is also an elephant. According to Uy, its massive Symphony Orchestra Program supported the status quo – but not really, I would say. Rather, the story resembles one of those foreign policy disasters in which good intentions ignite unanticipated consequences. One starting point for McNeil Lowry’s grand initiative was his accurate perception that symphonic musicians were grossly underpaid. Another was his thought that orchestras should, for the first time, offer full seasons of concerts and employment. These goals seemed to conjoin. By 1970-71, six orchestras had agreed to 52-week contracts; another five had contracts of 45 weeks or more. The new frequency of performance, however, was not audience-driven. True, many symphony musicians had now attained a respectable living wage for the first time – but at a hidden cost. Performing as many as 150 times a year, orchestras scrambled to devise concerts for which no listeners existed. Their budgets, including rapidly expanding departments devoted to marketing and development, mushroomed. There was also an artistic cost: fatigue and boredom. In retrospect, the musicians should have been paid more per service, not paid for more services.

The Ford Foundation was surprised and disappointed to see expanding orchestral deficits notwithstanding their largesse. Paradoxically, it became harder than ever for orchestras to “innovate.” For this failure they were duly punished: Foundations grew increasingly reluctant to help out. In the 1990s, when I was running the Brooklyn Philharmonic Orchestra at BAM, the BPO was accepted into the Knight Foundation’s “Magic of Music” program, created to support artistic experimentation. We were truly experimental – our programing was thematic and cross-disciplinary – but other orchestras in the group were not. Knight responded by terminating “The Magic of Music.” Today, the only major charitable foundation funding artistic innovation in the symphonic field is Mellon.

Orchestras are mainly to blame for these troubles. By and large, they have failed to rethink the concert experience, failed to explore native repertoire, failed to revisit issues of purpose and scope. But foundations are not blameless. Knight’s “The Magic of Music” failed to engage informed consultants. Susan Feder, Mellon’s long-time arts and culture program officer, is an exception; when she arrived in 2007, she shrewdly discriminated between recipients who were coasting and those with something on the ball.

In sum, orchestras have been left unprepared for the current cultural moment, with its changing audience demographics and shifting political, social, and arts mores. It will not be enough to simply engage more Black instrumentalists, soloists, and composers.

The story I have just told about Ford, Knight, and Mellon will not be found in Ask the Experts. Rather, Michael Sy Uy’s book is captive to the myopia of a precarious cultural moment, one that we today – all of us – mutually inhabit.

October 3, 2021

On the State of the Arts Today: An Emergency

Nicolas Bejarano Isaza is a young trumpeter, born in Colombia, living in LA. He specializes in new music. He also hosts a podcast: The Arts Salon.

I had the pleasure of meeting Nicolas via the trombonist David Taylor, aptly described in the New York Times as a “killer” virtuoso. Nicolas is no killer – but his cultural base and depth of inquiry are exceptional among young musicians today. He interviewed me for 90 minutes and 22 seconds – and if you have 90 minutes and 22 seconds, you won’t find our conversation boring.

The topic is the state of the arts today: an emergency.

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers