Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 19

May 10, 2020

Music in Wartime

Between 1942 and 1945, the three pre-eminent Russian composers wrote music responding to World War II. These responses differ in fascinating and revealing ways.

Both Dmitri Shostakovich and Serge Prokofiev were eyewitnesses to the war; Shostakovich in fact endured the beginning of the siege of Leningrad before being evacuated east along with Prokofiev and other eminent Soviet artists. Prokofiev’s explosive Seventh Piano Sonata (1942), the best-known of his three “War Sonatas,” evokes the actual sounds of war. Shostakovich’s Second Piano Trio (1944) exquisitely discloses an interior view of suffering and fortitude. That his wartime voice is interior makes it – however Russian – the more universal.

Igor Stravinsky, in Los Angeles, composed his Symphony in Three Movements (1942-45) as a “Victory Symphony” on commission from the New York Philharmonic. The finale was inspired by World War II newsreel images – vividly translated into sound, beginning with goose-stepping Nazi soldiers. But this remains an “armchair” view, activated by a financial incentive.

Today’s PostClassical Ensemble “More than Music” video (posted above) – the third in an ongoing series co-presented by The American Interest – is the premiere screening of “Shostakovich in Time of War,” an ingenious 45-minute film by Behrouz Jamali in which I take part as commentator. It revealingly juxtaposes Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and Stravinsky – and the performances, including a reading of the Prokofiev sonata by the inimitable Alexander Toradze, are amazing. The video artist Peter Bogdanoff contributes a singular visual rendering of Stravinsky’s finale, applying the pertinent newsreel clips.

The historian Richard Aldous will be hosting a related Zoom chat with Solomon Volkov (who collaborated with Shostakovich on his memoirs), Angel Gil-Ordóñez, and myself. It will take place Friday, May 15, at 6 pm. If you would like to participate, click here.

Regarding Stravinsky’s “war symphony” – the Philharmonic requested “a new symphony called ‘La Victoire’” to celebrate the impending victory over Germany and Japan. What next transpired is documented in tangled detail by correspondence in the New York Philharmonic Archives. The Philharmonic requested a program note. Stravinsky replied: “It is well known that no program is to be sought in my musical output. . . . Sorry if this is desapointing [sic] but no story to be told, no narration and what I would say would only make yawn the majority of your public which undoubtedly expects exciting descriptions. This, indeed would be so much easier but alas . . . . . ”

Stravinsky then asked the Philharmonic to publish a program note by the composer Ingolf Dahl. Dahl’s note, duly printed in the Philharmonic program book, was itself of the species to “make yawn the majority.” A specimen: “The thematic germs of this [first] movement are of ultimate condensation. They consist of the interval of the minor third (with its inversion, the major sixth) and an ascending scale fragment which forms the background to the piano solo of the middle part.” But Stravinsky obliged the Philharmonic with a brief “Word” conceding: “During the process of creation in this our arduous time of sharp shifting events, time of despear [sic] and hope, time of continual torments, of tention [sic] and at last cessation, relief, my [sic] be all those repercussions have left traces, stamped the character of this Symphony.”

The work thus described – the Symphony Three Movements – is in fact different in tone from the Apollonian exercises Stravinsky had long pursued. Parts are indisputably militant, march-like, propelled by harshly thrusting energies. Many writers, Dahl included, have likened it to a latter-day Rite of Spring. Another unmistakable influence is the swagger and muscle of big band jazz. (Mere months later, Stravinsky completed an Ebony Concerto composed on commission for Woody Herman.) In Stravinsky’s world premiere recording of the Symphony in Three Movements with the New York Philharmonic, the flying syncopations of the opening measures really swing.

Stravinsky later acknowledged Broadway, boogie-woogie, and “the neon glitter of Los Angeles’ boulevards” as influences on his American output. But this was nothing compared to a revelation recorded by Robert Craft in response to the question: “In what ways is the [Symphony in Three Movements] marked by world events?” Stravinsky answered:

“Certain specific events excited my musical imagination. Each episode is linked in my mind with a concrete impression of the war, almost always cinematographic in origin. For instance, the beginning of the third movement is partly a musical reaction to newsreels I had seen of goose-stepping soldiers. The square march beat, the brass-band instrumentation, the grotesque crescendo in the tuba – all these are related to those repellent pictures. In spite of contrasting musical episodes, such as the canon for bassoons, the march music predominates until the fugue, the beginning of which marks the stasis and the turning point. The immobility here seems to me comic, and so, to me, was the overturned arrogance of the Germans when their machine failed at Stalingrad. The fugal exposition and the end of the Symphony are associated with the rise of the Allies, and the final, albeit too commercial, D-flat chord – instead of the expected C – is a token of my extra exuberance in the triumph. The rumba in the finale, developed from the timpani part in the introduction to the first movement, was also associated in my imagination with the movements of war machines . . . ”

Although not everything Stravinsky said about himself bears scrutiny, and although not everything Craft said Stravinsky said can be taken at face value, and although Stravinsky’s testimony about applying wartime “newsreels” has been discounted by his biographer Steven Walsh, the proof is in the music: as Peter Bogdanoff’s video confirms, Stravinsky’s movement three narrative is a fit. Accompanied by the specified clips, this explosive finale, with its strutting marches and detonating chords, functions altogether admirably as a film score. In fact, the point of “stasis” midway through makes no apparent musical sense – it is, rather, a programmatic pivot upon which the tide of battle is reversed. George Balanchine’s famous setting of the Symphony in Three Movements winks at Hollywood and Broadway. But he also told his dancers to think of helicopter searches and other signatures of wartime. More recently, the conductor Valery Gergiev has called the symphony’s opening flourish “an alarm” which should sound “very brutal.” In the dialogue of bassoons near the opening of the finale he hears music of “fear.”

In his conversation with Craft, Stravinsky added, inimitably: “Enough of this. In spite of what I have admitted, the symphony is not programmatic. Composers combine notes. That is all.” But even accepting this hairpin distinction, the compositional process at hand is hardly autonomous. Its programmatic inspiration – the war and its imagery – is fundamental.Or is the Symphony in Three Movements a case of waning inspiration? Aaron Copland sensed in the American Stravinsky a composer who “copies himself.” An anomaly of the Symphony is the prominence of a solo piano in movement one, and of solo harp in movement two. In fact, the first movement originated as an abandoned sketch for piano and orchestra. And movement two appropriates eerie strains created to underscore an apparition of the Virgin Mary in The Song of Bernadette – film music Darryl Zanuck declined to use. Stravinsky rescued these fragments – and therefore composed some passages highlighting the solo piano and solo harp in his finale. But in fact, the pattern of scoring that results is a curious patchwork. And whether the mood and texture of movement two actually fit this “symphony” – for which Stravinsky considered the alternative title “Three Symphonic Movements” – is a good question.

A final frame of reference: Arnold Schoenberg, in Los Angeles, spurned the frequent autonomy of exile, befriending George Gershwin, teaching his UCLA students, mentoring Hollywood’s leading film composers; his A Survivor from Warsaw (1947) and Ode to Napoleon (1942) confront Hitler and the Holocaust with furious words set as Sprechstimme – a kind of heightened speech. Stravinsky, by comparison, was a poised bystander.

May 3, 2020

Shostakovich and the State

“People underestimate Stalin’s level of control,” says Solomon Volkov. “I once started to calculate how many people in the arts Stalin controlled personally — that is, read their writing, listened to their music, attended their performances. And it was close to one thousand. And not in some abstract way. This was an incredible, unprecedented amount of attention to the arts, which was Stalin’s habit. So that Shostakovich knew very well that he was under the constant observation of this most powerful person in the country.”

PostClassical Ensemble today continues its Sunday series of “More than Music” videos, in collaboration with The American Interest and WWFM The Classical Network.

“Shostakovich and the State” presents commentary by Solomon Volkov, author of Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich (1979). The musical focus is Shostakovich’s String Quartet No. 8 (1960): a unique autobiographical document, capturing a moment both personally and historically fraught. The composer’s musical signature — the four-note motif D, E-flat, C, B – begins and pervades the entire work. Though inscribed to “the victims of fascism,” it is at the same time an encoded narrative of harrowing decades of Stalinist oppression.

The Eighth Quartet is also well-known in a string-orchestra version created by Rudolf Barshai. This PostClassical Ensemble video features a terrific concert performance led by Angel Gil-Ordóñez (at 6:10), prefaced and followed by Volkov’s remarks. As a young man, Volkov wrote the first review of the Eighth Quartet – it became his ticket of introduction to the famous composer. He tells this story, and also talks (at 2:55) about Stalin as culture-tsar.

If you’re interested in taking part in a live Zoom chat with myself, Solomon Volkov, and Angel Gil-Ordóñez, click here. (This event is free, but registration is required.)

Next Sunday’s installment: Behrouz Jamali’s PCE film “Shostakovich in Time of War,” juxtaposing musical responses to World War II by Stravinsky, Prokofiev, and Shostakovich.

April 19, 2020

Music in Challenging Times — An Opportunity

Back in the 1930s, American radio – that is, American commercial radio, which is all we had – knew that listeners were amenable to paying attention to what they were hearing and nothing else. A long attention span was assumed.

Commensurately, the airwaves were full of classical music – a phenomenon I pondered in my most reviled book, Understanding Toscanini (1987). (Reviled because I foresaw the swift marginalization of classical music, but never mind.) I wrote:

“As Toscanini’s celebrity attested, culture’s new audience, tutored by Will Durant, H. G. Wells, the ‘University of Chicago Round Table,’ and Billy Phelps of Yale, feasted on great music. Radio offered the Metropolitan Opera and the NBC Symphony on Saturdays, the New York Philharmonic and ‘The Ford Hour’ on Sundays: as of 1939, these four well-known longhair broadcasts were said to reach more than 10 million families a week. Additional live broadcast concerts and operas, and portions of ‘serious’ music emanating from network studios, had diminished since the early thirties. Still, an average Sunday afternoon gave New York City radio listeners perhaps three ‘light classical’ studio concerts and as many studio recitals in addition to the Philharmonic broadcasts; an average Sunday evening added three or four more live concerts and recitals in addition to ‘The Ford Hour’; and the weekday schedule might include more than a dozen live broadcasts of hinterlands orchestras, studio orchestras, and studio recitals.”

An audience study conducted in 1939 showed that in cities (population 100,000 or more), 62 per cent of college graduates “liked listening to classical music in the evening.” For town of 2,500 and under, and farms, the percentage was 49.

You could also tune into Abram Chasins, whose “Piano pointers” on CBS and “Chasins’ Music Series” on NBC – commercial radio, ambitiously masterminded by William Paley and David Sarnoff — were workshops for amateur pianists.

That was then and now is now. And yet I read that a new survey of public radio stations shows that listeners are keen to find distractions from COVID 19. And for some time youtube has been discovering an appetite for “long form” content: two hours of talking and more.

I also read that in Germany’s minister of culture, Monika Grutters, has recommended an expenditure of 50 billion euros ($54 billion) for Germany’s “creative and cultural sectors.” She says: “Our democratic society needs its unique and diverse cultural and media landscape in this historic situation, which was unimaginable until recently. . . artists are not only indispensable, but also vital, especially now.”

At a moment when America’s performing arts institutions are challenged not merely to continue to function but to function in new ways, PostClassical Ensemble – the “experimental” DC-based chamber orchestra I co-founded 17 years ago with the wonderful Angel Gil-Ordonez – will undertake a series of videos exploring the role of music in society. We’ve tentatively christened it “PostClassical: More than Music.”

This initiative comes easily to us, as our programming has typically focused on music as an instrument for mutual understanding and human betterment. In fact, our library of two-hour WWFM webcasts, inimitably hosted by Bill McGlaughlin, is our starting point in this new venture, in which we are partnered by the film-maker Behrouz Jamali and the enterprising journal of politics, government, and culture The American Interest.

Our two most recent projects, before the virus changed everything, were An Armenian Odyssey, at the Washington National Cathedral, and Furtwangler in Wartime, via WWFM. The former explored the power of music to forge inspirational cultural synergies. The latter explored the power of music to “bear witness” during World War II.

We begin posting our new “More than Music” videos today with “Deep River: The Art of the Spiritual,” in which we are joined by PCE Resident Artist Kevin Deas.

Forthcoming programs will include “Shostakovich and the State” (with Solomon Volkov), Arthur Farwell and the “Indianists,” “The Russian Gershwin,” and “Dvorak and America.” The topics at hand are “What is the role of culture in a nation’s life?” and “Who is an American?”

For decades, conventional wisdom about the airwaves has been “classical music radio stations don’t want talking” and “avoid the unfamiliar.”

If that is ever to change, now is the time.

April 12, 2020

Furtwangler, Shostakovich, Toscanini: Music in Adverse Times

Wilhelm Furtwangler

Wilhelm Furtwangler Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Shostakovich Arturo Toscanini

Arturo ToscaniniA new podcast, produced by The American Interest (TAI), translates my article on “Furtwangler and Shostakovich: Bearing Witness in Wartime” into a 30-minute podcast with tremendous musical examples.

The distinguished historian Richard Aldous, as interlocutor, expands my purview to include Arturo Toscanini — a topic of which I’ve steered clear since the publication in 1987 of my Understanding Toscanini (the most discussed and reviled classical music book of its time). But Richard got me started re-comparing Furtwangler and Toscanini — conductors who say “we” and “I,” respectively — and I took the bait.

To hear the podcast, click here

To subscribe to TAI’s free daily newsletter, with considerable essays on politics, government, and culture, click here.

A novel feature of the newsletter are the always surprising listening advisories from editor-in-chief Jeffrey Gedmin, whose recent posting on Abraham Lincoln’s musical affinities included an aria sung (in Russian) by the incomparable Pavel Lisitsian. The connection was A Masked Ball.. Lincoln attended this Verdi opera — in which an American ruler is assassinated — at New York’s Academy of Music in 1861.

Googling the event to refresh my memory, I was amazed to discover that I had written about it for The New York Times in 2001 — and that the President-elect’s appearance at an opera house, in troubled times, inspired an impromptu performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner” by the entire company. Does such patriotism survive today? I learn from my friend Pedro Carbone, in Spain, that the daily ovation for health workers in Zaragoza includes singing: the Spanish national anthem and the EU anthem (set to Beethoven’s Ninth). Here on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, the daily 7 pm tribute, while stirring, is songless.

Here is what I wrote in 2001:

Lincoln and ”A Masked Ball” furnish a memorable snapshot of New York operatic life a century and a half ago. Imagine such a thing today as any president’s being spotted during the first intermission at the opera and exciting an ovation (President Bush would excite stupefaction) — after which the curtain would rise on a performance of ”The Star-Spangled Banner.” That is what happened when Lincoln attended ”A Masked Ball.” Isabella Hinkley, the soprano playing Oscar, sang the anthem’s first stanza half-turned toward Lincoln’s second-tier stage box. Then the entire company joined in, while a huge American flag, all 33 stars blazing, dropped from the proscenium.

Verse No. 2 was taken by Adelaide Phillips, the evening’s Ulrica, to deafening applause. Then came ”Hail, Columbia,” more cheering, and the resumption of ”A Masked Ball.” Lincoln left quietly before the last act and so never witnessed the killing of Riccardo.

April 6, 2020

Music and Healing: An Armenian Odyssey

The healing properties of music is suddenly an inescapable topic.

Serendipitously, the last concert given by PostClassical Ensemble before the pandemic shut down live music was an exercise in healing.

This was An Armenian Odyssey at the Washington National Cathedral on March 4. The final three minutes, documented in the film clip above, evoked the 2018 Velvet Revolution in Yerevan. It consummated a 75-minute Armenian narrative of diaspora, tragedy, and regeneration.

The memorable live animation was created by Kevork Mourad, whom you can see standing amongst the musicians. The cellist is Narek Hakhnazarian. The composer is Vache Sharafyan. PostClassical Ensemble is conducted by Angel Gil-Ordonez.

The troubadour ascending at the close, drawn by Kevork, is an iconic Armenian hero: Sayat-Nova, who composed and sang in four languages. In our production, he embodied cultural fluidity: poetry and song as instruments to foster mutual understanding.

The inspirational ambience of the Great Nave of the National Cathedral enhanced this message. Many wept. We were reminded of the ways in which music can empower and uplift – without appreciating the challenges we would all face in a matter of days.

March 15, 2020

Furtwangler and Shostakovich: Bearing Witness in Wartime

Today’s on-line “The American Interest” carries a greatly expanded version of my blog of Feb. 25 (scroll down for Shostakovich and Ives):

Books continue to be written about what it was like to live in Germany under Hitler. I wonder if any of the authors have auditioned Wilhelm Furtwängler’s wartime broadcasts with the Berlin Philharmonic. They should – and also ponder a kindred question: the function of culture in the life of a nation.

The online products of the Berlin Philharmonic include a $230 box set containing 22 CDs and a 180-page booklet. The contents comprise the orchestra’s complete surviving wartime broadcasts (1939-1945), in the best possible sound, as conducted by a performing artist as controversial as he is legendary. Though other eminent German musicians chose (or were compelled) to emigrate, Furtwängler stayed.

A specimen: the finale of Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 – the last work on Furtwängler’s last wartime broadcast (January 1945). This astounding document opens an audio window on life in Berlin when the city lay in rubbles. Since the orchestra’s historic home had been destroyed one year before, the venue was a faded operetta theater making do as a concert hall. The program had begun with Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 — interrupted midway through when the lights went out. The audience remained. An hour later, the concert resumed. Rather than returning to Mozart, Furtwängler skipped to the concert’s final scheduled work: the Brahms.

What was it like performing and hearing Brahms’ First under such dire circumstances? It becomes quite possible to find out.

Brahms would not have recognized Furtwängler’s1945 reading as Brahmsian. With its radical extremes of tempo and mood, it is not “true to the score.” Rather, it is true to the moment. What I glean is something I could not have predicted: not terror, but pride and defiance. The music itself references the finale of Beethoven’s Ninth, with its epochal call to humanity. Brahms, in turn, fashions a clarion C major horn call, banishing the dark – which on this singular occasion becomes an iteration of “the real Germany,” stalwart in the face of barbarism and insanity.

So potent is Furtwängler’senduring mystique that the debate over his legacy rages unabated. Certainly his presence in Nazi Germany lent prestige to Hitler’s regime. And yet he insisted that he was preserving a precious inheritance. To my ears, his 1945 Brahms broadcast makes these best intentions wholly tangible and intelligible.

Richard Taruskin, in one of three valuable essays in the Berlin Philharmonic booklet, considers “Expressivo in Tempore Belli: Considering the Conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler” – the most empathetic writing I can recall from this prolific music historian. Taruskin writes of Furtwängler:

“His definition of Deutschtum (Germanness) was elastic enough to encompass his Jewish countrymen. In an address commemorating Mendelssohn’s centenary in 1947, which was coincidentally the year of his denazification, Furtwänglerended with the explicit declaration that ‘Mendelssohn, Joachim, Schenker, Mahler – they are both Jews and German,’ and then added heartbreakingly: ‘They testify that we German have every reason to see ourselves as a great and noble people. How tragic that this has to be emphasized today.’”

As Taruskin stresses, Furtwängler’s notion of Werktreue – textual fidelity – was not that of Arturo Toscanini or Igor Stravinsky. Rather, it was Richard Wagner’s: not literal adherence to the composer’s notated instructions, but an act of extrapolation discovering the “idea” of the piece. And, I would add, that idea could prove malleable accordingly to time and place: conditions Furtwängler channeled with uncanny sensitivity and communicative force.

Schubert’s “Great” C major Symphony was a Furtwängler specialty. The work itself is polyvalent, both demonic and — as the Viennese term their notion of charmed wellbeing —gemütlich. Its second movement, marked “Andante con moto,” is and is not a “slow movement.” Rather, it is a march with trumpet tattoos in alternation with intimations of the sublime.

Furtwängler’s December 1942 broadcast performance is never gemütlich. When I had occasion to audition this wartime reading on the radio, my studio colleague Bill McGlaughlin memorably characterized its massive climax as “a firestorm.” Here Schubert’s march is a juggernaut hurtling toward an abyss. The abyss is a silence of three beats. In Furtwangler’s account, the silence lasts eight seconds: an eternity. Reacting in the moment, Bill’s voice quavered when he said: “This time we really broke it; we really broke civilization.” And he characterized the music finally lifting the silence – the tenuous pizzicatos, the tender cello song – as an act of dazed consolation.

Something awful is conveyed in Furtwangler’s wartime reading of Schubert’s climax. It is, I suppose, something Schubert – a seer — may have distantly or subliminally glimpsed. But it is Furtwängler, channeling the moment, who has uncovered it. This terrifying interpretation no more conforms to our notions of “Schubert” than Furtwängler’s 1945 Brahms First supports received wisdom. It instead affirms that music has no fixed meaning, that great works of art are so profoundly imagined that their intent and expression forever mold to changing human circumstances.

* * *

In his potent little book How Shostakovich Changed My Mind, Stephen Johnson tells a relevant story. He travelled to St. Petersburg in 2006 to meet an elderly clarinetist named Viktor Kozlov. Kozlov was a rare survivor of a famous symphonic performance: the Leningrad premiere of Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony on August 18, 1942. The city was in the grips of a murderous Nazi siege. Only fifteen members of the Leningrad Radio Orchestra remained alive. Rations were procured. Additional instrumentalists arrived in armed convoys. The 75-minute symphony, newly composed, was somehow performed. During the last movement, members of the audience began to stand. Shostakovich had born witness.

“One woman even gave the conductor flowers – imagine, there was nothingin the city!,” Kozlov recalled. “And yet this one woman found flowers somewhere. It was wonderful! The music touched people because it reflected the Siege. . . . People were thrilled and astounded that such music was played, even during the Siege of Leningrad!”

Johnson next writes:

“’When you hear this music today,’ I asked hesitantly, ’does it still have the same effect?’ Despite all I had heard, nothing prepared me for what happened next. It was as though a huge wave of emotion struck that apartment, and instantly both Kozlov and his wife were sobbing convulsively. He grasped my forearm tightly – I can feel it again as I’m writing – and just about managed to speak: ‘It’s not possible to say. It’s not possible to say.’”

Shostakovich the composer, Furtwängler the conductor, possessed a genius for channeling the moment. On opposite sides of a devastating conflict, both served a great city facing extinction. A sincerely Soviet artist, Shostakovich practiced attunement to a mass of listeners: spurning art for art’s sake, he prioritized his audience. Furtwängler pertinently insisted that he could only make music in the presence of sympathetic listeners. Equally significant was his baton technique: he notoriously eschewed clear downbeats. Rather than imposing a detailed interpretive blueprint, he bonded with his players in a transporting communal rite. Shostakovich’s symphonies say “we,” not “I.” It is the same with Furtwängler’s performances. This is what makes them feel empowering.

Of course there is a problem with such galvanizing strategies of shared expression. They are susceptible to evil intent. It is a problem inherent to culture itself, and to the protean adaptability of enduring artworks.

Another wartime Furtwängler performance I would call “terrifying” is of the closing moments of Wagner’s opera Die Meistersinger, as given September 5, 1938, in Nuremberg. Rudolf Bockelmann sings Wagner’s apotheosis to German art – in which Hans Sachs warns of “evil tricks” should Germany one day “decay under false, foreign rule.” Bockelmann’s blood-curdling delivery of “Habt acht!” (“Beware!”) is plainly a product of 1938, when Germany was already a nation apart — not 1862, when the opera was premiered. One can argue about Wagner’s intentions here – many have – but, indisputably, he has created a moment dynamically susceptible to changing times. In fact, I cannot think of a creative artist who so revealingly holds up a mirror to any given time or place. Wagnerism in the United States, peaking around 1890, was fundamentally meliorist, not remotely racist or anti-Semitic. At Wagner’s Bayreuth Theater in Hitler’s time, the Festspielhaus was festooned with swastikas and Die Meistersinger excited Nazi salutes.

Thomas Mann, who could never wholly escape his infatuation with Wagner, was a peerless authority on the Germany of Wagner and Furtwängler. He once wrote:

“Art will never be moral or virtuous in any political sense: and progress will never be able to put its trust in art. It has a fundamental tendency to unreliability and treachery; its . . . predilection for the ‘barbarism’’ that begets beauty [is] indestructible; and although some may call this predilection . . . immoral to the point of endangering the world, yet it is an imperishable fact of life, and if one wanted to eradicate this aspect of art . . . then one might well have freed the world from a serious danger; but in the process one would almost certainly have freed it from art itself.”

That is from Mann’s Reflections of a Non-Political Man (1919). With the coming of Hitler, Mann became a “political man”: he wrenched himself apart from the Germany he endorsed and embodied, and moved to California. “Everything else would have meant too narrow and specific an alienation of my existence,” he told a 1945 audience at the Library of Congress. “As an American I am a citizen of the world.” Seven years later, having witnessed the onset of the Cold War and the Red Scare, Mann deserted the U.S. for Switzerland; as early as 1951 he wrote to a friend: “I have no desire to rest my bones in this soulless soil to which I owe nothing, and which knows nothing of me.”

Like Furtwängler, Shostakovich was urged to emigrate and escape a monstrous master. Like Furtwängler,he would not. Custodians of a nation’s culture, oppressed by Hitler and by Stalin, Furtwängler and Shostakovich both were denounced for serving the devil – or derogated as mere stooges. Furtwängler did not join the Party. Shostakovich did. But Shostakovich was no Stalinist. As for Furtwängler, Arnold Schoenberg credibly attested:

“I am sure he was never a Nazi. He was one of those old-fashioned Deutschnationale from the time of Turnvater Jahn, when you were national because of those Western states who went with Napoleon This is more an affair of Studentennationalismus, and it differs very much from that of Bismarck’s time and later on, when Germany was not a defender, but a conqueror. Also I am sure that he was no anti-Semite – or at least no more than any non-Jew. And he is certainly a better musician than all those Toscaninis, Ormandys, Kussevitskis, and the whole rest.”

Furtwängler died in 1954, Shostakovich in 1975. Both outlived the tyrants who oppressed yet paradoxically empowered them.

***

Processing that Berlin Philharmonic Pandora box, I am finally directed to my own nation and its cultural possessions — and led to ponder a poverty of opportunity and risk.

When 9/11 happened – when, again, a great city was assaulted and wounded — America’s orchestras responded with the requiems of Mozart and Brahms, or with Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings. We had and have no Brahms, Schubert, or Shostakovich symphony.

What comes closest, I would say, is the Second Symphony of Charles Ives, completed around 1909. It is redolent of Connecticut porches and bandstands, of New England holidays and Transcendental climes. Every one of the symphony’s melodies – a dense potpourri – is an American tune, secular or religious. It is also a Civil War symphony surging to a patriotic peroration combining “Reveille” and the Civil War song “Wake Nicodemus” with “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean.” In a letter to the conductor Artur Rodzinski, Ives added that he had expressed “sadness for the slaves” by citing the Stephen Foster song “Old Black Joe.” And Ives’s appropriation of this tune, assigned to a solo cello or horn, is in truth his symphony’s most eloquent refrain.

That is: a song once sung in blackface, adapting a dialect caricaturing African-American speech, becomes the symphony’s lyric high point. So it is with America, a nation unfinished and unresolved, whose most popular entertainment for half a century featured white performers masquerading as blacks. The attendant complexities are manifold. Without blackface minstrelsy, there would be no American popular music as we know it. Before the Civil War, blackface was not necessarily racist. And Foster, once America’s most popular composer, was an empathetic observer of the enslaved Americans whose talents and energies he absorbed. As for Ives, he came from Abolitionist stock; his grandmother raised a black boy befriended by Ives’s father during the Civil War.

If Ives conceived the tapestry of his Symphony No. 2 as a knit fabric, if the symphony equally betrays American tears and schisms, it remains a work resilient enough to tell us truths about ourselves. Leonard Bernstein, whose knack for channeling the moment may have been his highest calling as a musical artist, belatedly premiered Ives’s Second in 1951. He also broadcast it and recorded it and proudly took it abroad, where in 1987 he recorded it again in Munich with a German orchestra. It all should have become a lesson and an inspiration.

But like Furtwängler and Shostakovich, Bernstein is unreplaced. American orchestras play Brahms and Schubert and Shostakovich. So far as American music goes, an opportunity to bear witness lies fallow. Or has the American experience simply not inspired concert music that binds a nation?

To access a “PostClassical” webcast featuring the Furtwangler performances mentioned in this article, click here.

February 25, 2020

Furtwangler in Wartime

Books continue to be written about what it was like to live in Germany under Hitler. I wonder if any of the authors have auditioned Wilhelm Furtwangler’s wartime broadcasts with the Berlin Philharmonic. They should.

About a year ago, the Berlin Philharmonic issued a $250 box containing 22 CDs and a 180-page booklet. The contents comprise the complete surviving Furtwangler wartime broadcasts (1939-1945) in the best possible sound. Since most of these performances were recorded with magnetic tape (unprecedented at the time), the dynamic range and general fidelity are superior to the broadcast concerts Americans were (once) accustomed to hearing.

A specimen: the finale of Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 – the final work on Furtwangler’s final wartime broadcast (January 1945). This astounding document opens an audio window on life in Berlin when the city lay in rubbles. Since the orchestra’s historic home had been destroyed one year before, the venue was a faded operetta theater making do as a concert hall. The program had begun with Mozart’s Symphony No 40 — interrupted midway through when the lights went out. The audience stayed. An hour later, the concert resumed. Rather than returning to Mozart, Furtwangler skipped to the concert’s final scheduled work: the Brahms.

What was it like performing and hearing Brahms’ First under such dire circumstances? It becomes quite possible to find out.

It was my privilege to audition this singular performance with my longtime radio colleagues Bill McGlaughlin and Angel Gil-Ordonez on the most recent “PostClassical” webcast via the WWFM Classical Network. Brahms would not have recognized Furtwangler’s 1945 reading as Brahmsian. With its radical extremes of tempo and mood, it is not “true to the score.” Rather, it is true to the moment. What I glean is something I could not have predicted: not terror, but pride and defiance. Brahms’s clarion C major horn call, banishing the dark, here becomes an iteration of “the real Germany,” stalwart in the face of barbarism and insanity.

We should stop presuming to judge Furtwangler’s decision to stay rather than emigrate. His conviction that in doing so he was preserving a precious legacy is here made wholly tangible and intelligible.

Richard Taruskin, in one of three valuable essays in the Berlin Phil booklet, ponders “Expressivo in Tempore Belli: Considering the Conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler” – the most empathetic writing I can recall from this prolific music historian. Taruskin writes of Furtwangler:

“His definition of Deutschtum (Germanness) was elastic enough to encompass his Jewish countrymen. In an address commemorating Mendelssohn’s centenary in 1947, which was coincidentally the year of his denazification, Furtwangler ended with the explicit declaration that ‘Mendelssohn, Joachim, Schenker, Mahler – they are both Jews and German,’ and then added heartbreakingly: ’They testify that we German have every reason to see ourselves as a great and noble people. How tragic that this has to be emphasized today.’”

As Taruskin stresses, Furtwangler’s notion of Werktreue – textual fidelity – was not Toscanini’s or Stravinsky’s. Rather, it was Wagner’s: not literal adherence to the composer’s notated instructions, but an act of extrapolation discovering the “idea” of the piece. And, I would add, that idea could prove malleable accordingly to time and place: conditions Furtwangler channelled with uncanny sensitivity and communicative force.

As I mentioned on the “PostClassical” webcast, I once had occasion to share with my wife, Agnes, a 1951 Furtwangler performance of Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique Symphony. This justly famous Radio Cairo broadcast does and does not resemble Furtwangler’s 1938 studio recording. The difference is the memory of war. Tchaikovsky’s symphony seems — as Agnes remarked – “about World War II.” The composer’s autobiographical heart-ache and Weltschmerz are here transformed into a dire existential statement transcending the personal.

Shostakovich is not irrelevant. He, too, possessed a genius for channeling the moment. The legendary first Leningrad performance of Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony, in the midst of a murderous Nazi siege, was cathartically empowering for a great city facing extinction. Shostakovich’s Seventh was a direct product of those circumstances. Brahms had never intended his First Symphony as a survival strategy. But that is what Furtwangler made it become.

The other discovery of our webcast was a Schubert passage. His “Great” C major Symphony was a Furtwangler specialty. The work itself is polyvalent, both gemutlich and demonic. Its second movement, marked “Andante con moto,” is and is not a “slow movement.” Rather, it is a march with trumpet tattoos in alternation with intimations of the sublime. Furtwangler’s wartime broadcast, in December 1942, is never gemutlich. Bill McGlaughlin, in the WWFM studio, memorably characterized its massive climax as “a firestorm.” Here Schubert’s march is a juggernaut hurtling toward an abyss. The abyss is a silence of three beats. In Furtwangler’s reading, the silence lasts eight seconds: an eternity. Reacting in the moment, Bill’s voice quavered when he said: “This time we really broke it; we really broke civilization.” And he characterized the music finally lifting the silence – the tenuous pizzicatos, the tender cello song – as an act of dazed consolation.

Something awful is conveyed in this Furtwangler reading of Schubert’s climax. It is, I suppose, something Schubert – a seer — may have distantly or subliminally glimpsed. But it is Furtwangler, channeling the moment, who has uncovered it. This reading no more conforms to our notions of “Schubert” than those Brahms and Tchaikovsky performances support received wisdom. They instead affirm that music has no fixed meaning, that great works of art are so profoundly imagined that their intent and expression forever mold to changing human circumstances.

For more on Furtwangler, see my blogs of Aug. 4 and 8, 2018.

A LISTENING GUIDE FOR THE WEBCAST:

PART ONE:

10:18 – Brahms Symphony No. 1: finale (January 1945)

39:40 – Bruckner Symphony No. 9: first movement (October 1944)

PART TWO:

00:00 – Beethoven Symphony No. 5: first movement (September 1939)

7:09 – Beethoven Symphony No. 5: movements three and four (September 1939)

21:38: — Schubert: Symphony No. 9: second movement (December 1942); to hear the silence, go to 32:00

45:08 – Schubert: Symphony No. 9: fourth movement (December 1942)

February 9, 2020

The Best of the “Black Symphonies”

For this weekend’s “Wall Street Journal” I have written an impassioned encomium for William Dawson’s thrilling “Negro Folk Symphony” of 1934 — still (alas) buried treasure:

In 1926 the African-American poet Langston Hughes wrote a seminal Harlem Renaissance essay, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” The mountain “standing in the way of any true Negro art in America,” he declared, was an urge “toward whiteness,” a “desire to pour racial individuality into the mold of American standardization, and to be as little Negro and as much American as possible.” Hughes cited, as an antidote, “the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul”: jazz and the blues.

Truly, America’s protean black musical mother lode has found expression in popular genres of its own invention—not string quartets, symphonies and operas. Nevertheless, a concurrent black classical music was pursued—a buried history today being exhumed. The notable interwar black symphonists comprise a short list of three: William Grant Still, Florence Price and William Levi Dawson. Their failure to excite attention was partly a consequence of institutional bias: African-Americans did not play in major American orchestras or conduct them. And there was also a pertinent aesthetic bias: The reigning modernist idiom was streamlined and clean, inhospitable to vernacular grit. It projected a sanitized “America.”

Over the past decade, both Still and Price have acquired new prominence. But the buried treasure is Dawson’s “Negro Folk Symphony” of 1934, whose three movements chart an ascendant racial odyssey. They notably embed such spirituals as “O Lemme Shine.” A heraldic horn call, symbolically linking Africa and America, binds the whole. Dawson (1899-1990), then 35 years old, had since 1931 led the Tuskegee Institute Choir. He had never before attempted a symphony.

The “Negro Folk Symphony” is anchored by its central slow movement, “Hope in the Night.” It begins with a dolorous English horn tune set atop a parched pizzicato accompaniment: “a melody,” Dawson writes in a program note, “that describes the characteristics, hopes, and longings of a Folk held in darkness.” A weary journey into the light ensues. Its eventual climax is punctuated by a clamor of chimes: chains of servitude. Finally, three gong strokes that prefaced the movement—“the Trinity,” says Dawson, “who guides forever the destiny of man”—are amplified by a seismic throb of chimes, timpani and strings.

If the symphony’s governing mold is European and (as Hughes put it) “standardized,” its energies remain uninhibited. Its lightning physicality of gesture—at one point, the music is intended to suggest “rhythmic clapping of hands and patting of feet”—exudes spontaneity, even improvisation. Dawson seizes the humor, pathos and tragedy of the sorrow songs of the cottonfield with an oracular vehemence. The best-known roughly contemporaneous American symphonies are the Third Symphonies of Aaron Copland and Roy Harris: leaner works favoring a modernist decorum. Dawson’s symphony, in comparison, exudes a wild folk energy driven by an exigent cause.

Notwithstanding its present obscurity, Dawson’s symphony received a galvanizing premiere by Leopold Stokowski and his Philadelphia Orchestra in 1934. Speaking from the stage, Stokowski called it “a wonderful development.” He also broadcast the symphony nationally, and took it to Carnegie Hall. Both in New York and Philadelphia, the young composer was repeatedly called to the stage. Far more remarkable is that “Hope in the Night,” with its culminating three-fold groundswell, ignited an ovation midway through every performance.

Leonard Liebling of the New York American hailed Dawson’s symphony as “the most distinctive and promising American symphonic proclamation which has so far been achieved.” Its most ardent admirers included W.E.B. DuBois’s future wife, Shirley Graham, who wrote to Dawson of her “joy and pride.” As the music historian Gwynne Kuhner Brown has pointed out, the “tumultuous approbation the ‘Negro Folk Symphony’ received from critics and audiences alike set it apart—not only from contemporaneous works by African-Americans, but also from most new classical music of the period.”

After that, the “Negro Folk Symphony” disappeared from view. Stokowski returned to the work in 1963, recording it with his American Symphony. Neeme Jarvi recorded it with the Detroit Symphony 31 years later. But performances and recordings of consequence remain few and far between.

The vital question becomes: “What if?” Dawson became a leading arranger of black spirituals, an honored éminence grise. But he had hoped to write a series of symphonies. He had hoped to conduct orchestras. Antonin Dvorak, teaching in New York in 1893, famously and controversially predicted that a “great and noble school” of American classical music would arise from the “Negro melodies” he adored. His African-American assistant, Harry Burleigh, turned spirituals into concert songs with electrifying success beginning in 1913. George Gershwin, in 1935, produced an opera saturated with the influence of “Negro melodies”: “Porgy and Bess,” arguably the highest creative achievement in American classical music (and this season’s smash hit at the Metropolitan Opera). No less than Dawson’s symphony, these lonely examples—however anathema to Langston Hughes’s famous admonition—suggest that Dvorak did not overestimate the music of black Americans. Rather, he overestimated America.

To read a pertinent essay on “black classical music,” click here.

January 21, 2020

Allan Bloom, Identity Politics, and “Closed Minds”

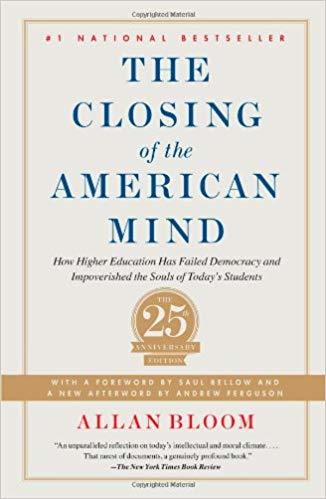

Looking for another book not long ago, I stumbled upon Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind. In 1987, it was a national sensation, a trigger-point for debate over the legacy of the sixties and its “counter-culture.”

Subtitled “How Higher Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today’s Students,” Bloom’s salvo attacked from the right. It was less a polemic than a closely reasoned argument fortified with lofty philosophic learning and grounded classroom experience.

My copy of The Closing of the American Mindis a paperback with scant evidence of close scrutiny. Some three dozen pages are heavily marked with dismissive marginalia. Bloom took aim at my own generation (I was born in 1948). And its political complexion was anathema.

But times have changed and so have I. Rather than replacing it on the shelf, I re-opened The Closing of the American Mind– and discovered that Allan Bloom was prophetic. In effect, he prophesied identity politics and political rectitude – and closed minds and “impoverished souls.”

This is the gist of my long piece in last weekend’s edition of The American Interest. You can read the whole thing here.

And here (from my article) is some of what I have to say about the impact of closed minds and impoverished souls on my own professional endeavors:

American classical music is today a scholarly minefield. The question “What is America?” is central. So is the topic of race. The American music that most matters, nationally and internationally, is black. But classical music in the US has mainly rejected this influence – which is one reason it has remained impossibly Eurocentric. As the visiting Czech composer Antonin Dvorak emphasized in 1893, two obvious sources for an “American” concert idiom are the sorrow songs of the slave, and the songs and rituals of Native America. Issues of appropriation are front and center. It is a perfect storm.

Dvorak directed New York City’s National Conservatory of Music from 1892 to 1895 – in the rise-and-fall of American classical music, a period of peak promise and high achievement. It speaks volumes that he chose as his personal assistant a young African-American baritone who had eloquently acquired the sorrow songs from his grandfather, a former slave. This was Harry Burleigh, who after Dvorak died turned spirituals into concert songs with electrifying success. (If you’ve ever heard Marian Anderson or Paul Robeson sing “Deep River,” that’s Burleigh.) During the Harlem Renaissance, Burleigh’s arrangements were reconsidered by Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes, both of whom detected a “flight from blackness” to the white concert stage. Today, Burleigh’s “appropriation” of the black vernacular is of course newly controversial. That he was inspired by a white composer of genius becomes an uncomfortable fact. An alternative reading, based not on fact but on theory, is that racist Americans impelled him to “whiten” black roots. Burleigh emerges a victim, his agency diminished.

Compounding this confusion is another prophet: W E. B. Du Bois, who like Dvorak foresaw a black American classical music to come. The pertinent lineage from Dvorak to Burleigh includes the ragtime king Scott Joplin (who considered himself a concert composer) and the once famous black British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, urged by Du Bois, Burleigh, and Paul Lawrence Dunbar to take up Dvorak’s prophecy. After Coleridge-Taylor came notable black symphonists of the 1930s and forties: William Grant Still, William Dawson, and Florence Price, all of them today being belatedly and deservedly rediscovered.

But the same lineage leads to George Gershwin and Porgy and Bess: a further source of discomfort. I have even been advised, at an American university, to omit Gershwin’s name from a two-day Coleridge-Taylor celebration. But Coleridge-Taylor’s failure to fulfill Dvorak’s prophecy – he was too decorous, too Victorian – cannot be contextualized without exploring the ways and reasons that Gershwin did it better. As for Gershwin’s opera: even though Porgy is a hero, a moral paragon, it today seems virtually impossible to deflect accusations of derogatory “stereotyping.” The mere fact that he is a physical cripple, ambulating on a goat-cart, frightens producers and directors into minimizing Porgy’s physical debility. But a Porgy who can stand is paradoxically diminished: the trajectory of his triumphant odyssey – of a “cripple made whole” — is truncated. (On Porgy and Bess at the Met, click here.)

Gershwin discomfort is mild compared to the consternation Arthur Farwell (1872-1952)invites. He, too, embraced Dvorak’s prophecy. As the leading composer in an “Indianists” movement lasting into the 1930s, Farwell believed it was a democratic obligation of Americans of European descent to try to understand the indigenous Americans they displaced and oppressed – to preserve something of their civilization; to find a path toward reconciliation. His Indianist compositions attempt to mediate between Native American ritual and the Western concert tradition. Like Bela Bartok in Transylvania, like Igor Stravinsky in rural Russia, he endeavored to fashion a concert idiom that would paradoxically project the integrity of unvarnished vernacular dance and song. He aspired to capture specific musical characteristics – but also something additional, something ineffable and elemental, “religious and legendary.” He called it – a phrase anachronistic today – “race spirit.”

As a young man, Farwell visited with Indians on Lake Superior. He hunted with Indian guides. He had out-of-body experiences. Later, in the Southwest, he collaborated with the charismatic Charles Lummis, a pioneer ethnographer. For Lummis, Farwell transcribed hundreds of Indian and Hispanic melodies, using either a phonograph or local singers. If he was subject to criticism during his lifetime, it was for being naïve and irrelevant, not disrespectful or false. The music historian Beth Levy – a rare contemporary student of the Indianists movement in music – pithily summarizes that Farwell embodies a state of tension intermingling “a scientific emphasis on anthropological fact” with “a subjective identification bordering on rapture.” Considered purely as music, his best Indianist are memorably original – and so, to my ears, is their ecstasy.

These days, one of the challenges of presenting Farwell in concert is enlisting Native American participants. For a recent festival in Washington, D.C. – “Native American Inspirations,” surveying 125 years of music inspired by Native America — I unsuccessfully attempted to engage Native American scholars and musicians from as far away as Texas, New Mexico, and California. My greatest disappointment was the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian, which declined to partner. A staff member explained that Farwell lacked “authenticity.” But Farwell’s most ambitious Indianist composition — the Hako String Quartet (1922), a centerpiece of our festival– claims no authenticity. Though its inspiration is a Great Plains ritual celebrating a symbolic union of Father and Son, though it incorporates passages evoking a processional, or an owl, or a lighting storm, it does not chart a programmatic narrative. Rather, it is a 20-minute sonata-form that documents the composer’s enthralled subjective response to a gripping Native American ceremony.

A hostile newspaper review of “Native American Inspirations” ignited a torrent of tweets condemning Farwell for cultural appropriation. This crusade, mounted by culture-arbiters who have never heard a note of Farwell’s music, was moral, not aesthetic. It mounted a chilling war cry. If Farwell is today off limits, it is partly because of fear – of castigation by a neighbor. I know because I have seen it. (To listen to the music of Arthur Farwell, click here.)

Arthur Farwell is an essential component of the American musical odyssey. So is Harry Burleigh. So are the blackface minstrel shows Burleigh abhorred – they were a seedbed for ragtime and what came after. Even alongside the fullest possible acknowledgement of odious minstrel caricatures, a more nuanced reading of this most popular American entertainment genre is generally unwelcome. It is, for instance, not widely known that pre-bellum minstrelsy was an instrument of political dissent from below. Blackface minstrelsy was not invariably racist.

Charles Ives’s Second Symphony is one of the supreme American achievements in symphonic music. Its Civil War finale quotes Stephen Foster’s “Old Black Joe” by way of expressing sympathy for the slave. When there are students in the classroom who cannot get past that, the outcome is Bloomsian: closed minds.

January 5, 2020

JFK’s Cold War Cultural Dogma — and Where It Came From

During the cultural Cold War, President John F. Kennedy delivered eloquent speeches claiming that only “free societies” fostered great creative art. But no one scanning centuries of Western literature and music could possibly believe that. Among countless counter-examples was the Soviet Union at that very moment. Its film-makers included Tarkovsky, its poets Akhmatova, its novelists Solzhenitsyn, its composers Shostakovich — all of whom were acclaimed in the West as of 1963, the year of Kennedy’s most ambitious cultural pronouncements.

A crucial intellectual source of this curious Cold War dogma was a minor Russian-born composer exiled in the US: Nicolas Nabokov, General Secretary of the CIA-funded Congress for Cultural Freedom. His link to the Kennedy White house was Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., whose once influential book The Vital Center (1949) supported an equation between a citizen’s freedom of speech and an artist’s freedom of expression. But artists can suffer from “too much freedom” – a condition of rootlessness such as afflicted Igor Stravinsky in Los Angeles, or Aaron Copland when he complained that American composers were “working in a vacuum.”

All this is the subject matter of my book-in-progress Cold War Quartet: JFK, Stravinsky, Shostakovich and the Culture Warrior – the first outcome of which is a long article published this weekend in the Los Angeles Review of Books. You can read it here. For an excerpt, read on:

“It was Nabokov’s longtime association with Arthur

Schlesinger that brought him into contact with the Kennedys. Doubtless, as General

Secretary of the CCF, his activities would not in any event have gone wholly

unnoticed in the Oval Office. But it was Schlesinger, as special advisor to the

President, who facilitated a direct relationship. Nabokov was first received at

the White House in 1961 during a visit to fund-raise for CCF programs; the

First Lady gave him a tour. At Schlesinger’s suggestion, Nabokov compiled for

Mrs. Kennedy a list of cultural personalities worthy of White House notice. A

year later, thanks to Schlesinger, Nabokov helped to plan a White House dinner

honoring Stravinsky’s 80th birthday. In the Green Room, Nabokov

observed Kennedy asking Stravinsky what he thought of the leading Soviet

composers. Stravinsky, Nabokov later recalled, ‘turned to the president, in his

most courtly manner, and replied: “Mr. President, I have left Russia since 1914

and have so far not been in the Soviet Union. I have not studied or heard many

of the works of these composers. I have therefore no valid opinion.” And the

president looked at me over Stravinsky’s shoulder and smiled approvingly.’

“Stravinsky, to his chagrin, had been conspicuously preceded

at the White House by Pablo Casals. Nothing like this had occurred under Dwight

Eisenhower. A declared outsider to high culture, Eisenhower had called ‘freedom

of the arts’ a ‘basic freedom,’ versus using artists as ‘tools of the state’ –

but without JFK’s patina of erudition and experience. At the Kennedys’ Camelot,

Jackie’s high-cultural aspirations were tangible, and her husband made the arts

a pronounced American cause. No less than the Russia hands Bohlen and Kennan,

the White House doubtless deferred to Nabokov’s expert understanding of Soviet

musical life. In fact, Kennedy’s core arts manifestos were drafted by

Schlesinger. This connects the dots. In The

Vital Center (1949), Schlesinger

had reframed liberal democratic politics in terms of a fierce individualism,

rejecting the collectivism of the Soviet-based cultural front. High culture,

concomitantly, was an elite exercise in art for art’s sake. Nabokov, the

authority on Soviet culture, furnished empirical proof that, absent unfettered

individualism, the creative act was nullified. Surely Nabokov was, in effect,

the source of the President’s elaborated views on ‘free societies’ as a necessary

precondition for high creative achievement, and of his blunt dismissal of

political art.

“Nabokov found the Kennedys a little gauche and likened the

First Lady’s idea of hostessing to a mixture of Dior, Chanel, Saint-Lauren, and

Broadway. In settings more intellectual than the White House, however, he was

the proverbial life of the party. His conversational aplomb is on full display

in Tony Palmer’s superb 2008 Stravinsky documentary, as he elegantly frames the

composer’s ‘inherent quality of irony’: ‘Stravinsky on one side was a hedonist,

enjoying all the pleasure of life — loving to eat, good wine, and for a very

long time pretty girls. On the other side, he was a rigorously ritualistic and

religious person — like ancient people are.’ He is also observed sipping Scotch

with Stravinsky while conversing in four languages.

“Nicolas Nabokov seemed the very embodiment of cosmopolitan

charm. But his worldliness can be read as a destabilizing rootlessness.”

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers